User login

The VHA is the nation’s largest integrated health care delivery system, providing comprehensive medical care to about 6 million patients annually. In addition to revolutionizing its primary care delivery through widespread implementation of patient-centered medical homes (Patient Aligned Care Teams), the VHA is also transforming its specialty care delivery through use of its specialist workforce and innovative technologies, such as telemedicine and electronic consultations (e-consults).1

VHA specialty care is currently distributed using a hub and spoke model within larger regional networks spanning the U.S. This approach helps overcome geographic variation in specialist workforce (eg, predilection for metropolitan areas) but limits specialty care access for patients and primary care providers (PCPs) due to distance barriers.2-4 With the VHA electronic medical record (EMR) system, it is now feasible to send expertise electronically across the system (eg, e-consult). Whether this should occur at the regional VISN or national level to smooth out variation in specialist workforce depends in part on current specialist distribution within and across regions.

Related: Recurrent Multidrug Resistant Urinary Tract Infections in Geriatric Patients

Hand in hand with an aging veteran population is a growing clinical demand for urologic specialty care to treat urinary incontinence, prostate enlargement, and prostate cancer. Unfortunately, over 60% of U.S. counties lack a urologist, creating troublesome workforce issues.3 For these reasons, this study analyzed existing administrative data to understand regional variations in the distribution of and demands for the VHA urologist workforce. This study tested whether workforce distribution is balanced or imbalanced across regional networks, in part to inform whether the VHA should offer electronic or other national access to its urologic specialty care.

Methods

Fiscal year (FY) 2011 Specialty Physician Workforce Annual Report data from the VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing was used to characterize the distribution and concentration of urologists at 130 VHA facilities.5 The annual report provided a longitudinal management tool for reporting clinical productivity, efficiency, and staffing, and included benchmark data for each facility (eg, physician workforce, annual patient visits).

Demand for Urologic Specialty Care

The number of unique urology patients from the report was used as one approach to the demand for VHA urologic specialty care. This measure represented the number of unique patients evaluated in a urology clinic at least once over the FY. The number of newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer in calendar year 2010 within each VISN was also used as a more discrete measure of regional urologic care demand. Whereas care for other common urologic conditions, such as incontinence or prostate enlargement, may or may not be referred (ie, latent demand), prostate cancer care consistently involves urologists and is more specific for caseload.

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Because each VISN covered a relatively large geographic area, most with roughly equivalent numbers of facilities, there was no a priori reason to expect a difference in urologic workload and consequently urologic workforce between networks. On the other hand, within networks one might expect that urologists would be concentrated in hospitals that have more complicated patient cases, because the hospitals serve a tertiary or referral role. Yet even within a network, significant imbalances in specialist supply might require creative solutions to maintain adequate access of patients and PCPs to specialists.

Urologist Workforce

The full-time equivalent employee (FTEE) variable for urologic specialty care from the 2011 annual report was used as the primary outcome measure for urology workforce.5 This facility-level measure represented the clinical time urologists spent in direct patient care at each facility. It included the clinical effort of full-time as well as contract physicians and was also reported as an aggregate measure at the regional VISN level. Urologist workforce at the VISN level was the sum of all urologist FTEEs within its facilities. Adjusted rates also were provided (eg, FTEE/10,000 urology patients).

Other Workforce Factors

Also examined as covariates in the analysis were other measures related to urologist workforce. As the nation’s largest provider of graduate medical education, urology residents rotate through many VHA facilities, contributing to the workforce totals. For this reason, resident FTEE was examined as an independent variable in this study.

Understanding facility complexity (ie, case mix) was also essential for rational allocation of specialty care resources, as demand generally increases with increasing case mix. Therefore, a medical center group (MCG) case mix measure of complexity and its relationship with urologist workforce was examined. It was expected that increasing specialty care volume, resident staff, and facility complexity would be associated with increasing urologist workforce.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize VHA urology patients and urologist workforce within each regional VISN and its facilities. To better understand the relationship between case mix and urologist workforce, facilities were sorted according to MCG and characterized the unique urology patients, urologists, and residents at each level. Analysis of variance was used to test whether increasing MCG was associated with a higher number of urology patient caseloads. Multivariable linear regression models were then used to determine whether complexity was associated with urologist workforce after adjusting for resident and patient volume.

Related: Antibiotic Therapy and Bacterial Resistance in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury

Multilevel regression modeling, an extension of linear regression modeling suitable for partitioning the variation in an outcome variable attributable to different levels (ie, facility and VISN), was used to examine whether variation in the urologist workforce was primarily based at the facility or regional VISN level.6 This approach accounted for the potentially correlated nature of the data (ie, multiple facilities within each VISN) by incorporating a VISN-level random effect in the model. A random intercept model with no explanatory variables, known as an empty model, was used as the primary model.6 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) corresponding to the estimated variance components from the empty model was calculated to determine the portion of the total variation in unadjusted urologist workforce that occurs between VISNs.7 Prostate cancer caseload was then included to test whether allocation seemed to be driven by clinical need or other regional factors.

All analyses were performed using STATA, Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and all testing was 2-sided. The probability of a type I error was set at .05. This study protocol was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Results

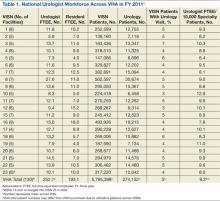

Nearly 1 in 20 VHA patients (n = 274,152) were evaluated in a urology clinic at least once in FY 2011. It was found that 252.7 FTEE and 193.1 residents comprised the VHA urologist workforce (Table 1). Marked regional variation was found in unadjusted urologist staffing at both the facility and VISN levels. The urologist workforce ranged from 0.17 to 5.91 FTEEs across the 130 VHA facilities. At the VISN level, staffing varied over 5-fold (5.8 FTEEs in VISN 2 to 27.6 FTEEs in VISN 8).

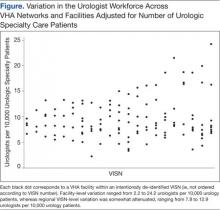

Variation in the VHA urologist workforce distribution persisted even after standardizing by patient volume. The urologist workforce continued to vary from 0.94 to 9.95 FTEEs per 100,000 facility patients. This was even more dramatic when adjusted for volume of unique urology patients, ranging from 2.2 to 24.2 FTEE urologists per 10,000 urology patients (Figure).5 From the specialist perspective, each might serve 18 to 64 newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer annually, depending on the VISN.

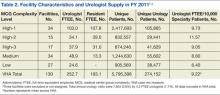

Forty percent of urologists were located in 34 of the most complex facilities (Table 2). Urology patient caseload was associated with facility complexity in univariate analysis (P < .001). In the adjusted multivariable model, increasing facility complexity was associated with increasing urologist workforce (P < .001) as well as resident staffing (P < .001), but not with urology patient caseload (P = .27). The empty multilevel model indicated that 27.3% of variation in unadjusted urologist workforce (ICC = 0.273, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.098-0.448) was attributable to differences at the regional network level. After adjustment for VISN prostate cancer caseload, this decreased to 24.8% (ICC = 0.248; 95% CI, 0.076-0.419).

Discussion

The VHA urologist workforce served over 250,000 patients in FY 2011, and a substantial variation in workforce distribution at the facility and VISN levels was identified in this study. After adjusting for prostate cancer caseload as a proxy for clinical demand, there was some imbalance of urology specialists across regional networks, though most workforce variation occurred within networks in this integrated delivery system. Based on these findings, VHA specialty care initiatives should likely focus within regional networks rather than pursue electronic efforts nationally to improve specialty care access for patients and PCPs.

Regional variation in the VHA urologist workforce was expected, given a limited national supply of urologists and specialist preferences toward metropolitan areas.2-4 Overcoming this maldistribution has important implications for outcomes in many urologic disease processes.8-10 For example, counties with ≥ 1 urologist have up to a 20% reduction in bladder and prostate cancer-related mortality compared with those without a urologist.4 Moreover, the number of veterans with known urologic needs or currently receiving urologic specialty care likely significantly undercounts the total number who could benefit from this care. This is particularly true for facilities with fewer urology resources where patients may be less likely to get a referral, or if they are referred, it is likely outside VHA, creating fragmented care and potentially higher cost.

Understanding the urology workforce distribution, coupled with its sophisticated nationwide EMR, VHA has a unique opportunity to transform how urologic specialty care is delivered without moving around the current workforce. Based on these findings, the system could redistribute resources within each region to meet growing specialty care needs through telemedicine.

At least 2 innovative approaches are underway that might serve the system’s urology care needs: e-consults and the Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) video teleconsulting and education project.11,12 The first allows PCPs to request specialist review of the EMR, interpretation of the specific problem, and recommendation for a plan of care, which may or may not include a specialist visit.1,13 The second involves video conferences, which allow multiple PCPs from less complex facilities or rural areas to present cases to specialists from tertiary medical centers for real-time consultation and case-based learning. These initiatives could take advantage of the facility-based variation in urologist workforce by linking facilities with relatively generous urology resources with those with fewer resources to meet the needs of each region’s population and their PCPs while minimizing travel and wait times.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, FY 2011 data were used; notably, the VHA urologist workforce remained relatively stable from 2008 through 2011. Second, characteristics of individual VHA urologists, clinical productivity, and skill level were not examined. However, a 2008 study found that nearly all VHA urologists are board certified, mitigating skill level concerns.14 Third, it is possible that demand is partially driven by existence of resources, and there may be patients who might benefit from urologic care but who are not yet diagnosed. The analysis is conservative in this regard, in that demand may be greater than what was detected using the selected study methods. Last, this study examined specialist workforce within a single system. However, ensuring specialist resources are well distributed is a concern for most health systems, particularly in light of recent policy efforts, including accountable care organizations.15

Conclusion

Much of the variation in the VHA urologist workforce exists at the facility rather than the regional level. Optimizing the distribution of these specialty care resources could be achieved through novel care delivery models within each regional network that are well-aligned with current VHA initiatives. Successfully utilizing this workforce distribution has the potential to improve urologic care for veterans across the country and could be applied to improve access to all types of specialists in underserved and understaffed areas.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Skolarus is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 12-171).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Graham GD; Office of Specialty Care Transformation, Department of Veterans Affairs Patient Care Services. Specialty care transformation initiatives. http://www.pva.org/atf/cf/%7BCA2A0FFB-6859 -4BC1-BC96-6B57F57F0391%7D/Friday_Graham_Specialty%20Care%20Transformation%20Initiatives.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed February 3, 2015.

2. Neuwahl S, Thompson K, Fraher E, Ricketts T. HPRI data tracks. Urology workforce trends. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2012;97(1):46-49.

3. Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol. 2009;181(2):760-765; discussion 765-766.

4. Odisho AY, Cooperberg MR, Fradet V, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Urologist density and county-level urologic cancer mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2499-2504.

5. Fiscal Year 2011 VHA Physician Workforce & Support Staff Data. VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, & Staffing Website. https://opes.vscc.med.va.gov. Published December 2011.

6. Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc;1999.

7. Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1159-1180.

8. Weiner DM, McDaniel R, Lowe FC. Urologic manpower issues for the 21st century: Assessing the impact of changing population demographics. Urology. 1997;49(3):335-342.

9. Gee WF, Holtgrewe HL, Albertsen PC, et al. Subspecialization, recruitment and retirement trends of American urologists. J Urol. 1998;159(2): 509-511.

10. McCullough DL. Manpower needs in urology in the twenty-first century. Urol Clin North Am. 1998;25(1):15-22.

11. Saifu HN, Asch SM, Goetz MB, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):207-212.

12. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

13. Hysong SJ, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: A qualitative analysis. Implement Sci. 2011;6:84.

14. Tyson MD, Lerner LB. Profile of the veterans affairs urologist: Results from a national survey. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1460-1462.

15. Landon BE, Roberts DH. Reenvisioning specialty care and payment under global payment systems. JAMA. 2013;310(4):371-372.

The VHA is the nation’s largest integrated health care delivery system, providing comprehensive medical care to about 6 million patients annually. In addition to revolutionizing its primary care delivery through widespread implementation of patient-centered medical homes (Patient Aligned Care Teams), the VHA is also transforming its specialty care delivery through use of its specialist workforce and innovative technologies, such as telemedicine and electronic consultations (e-consults).1

VHA specialty care is currently distributed using a hub and spoke model within larger regional networks spanning the U.S. This approach helps overcome geographic variation in specialist workforce (eg, predilection for metropolitan areas) but limits specialty care access for patients and primary care providers (PCPs) due to distance barriers.2-4 With the VHA electronic medical record (EMR) system, it is now feasible to send expertise electronically across the system (eg, e-consult). Whether this should occur at the regional VISN or national level to smooth out variation in specialist workforce depends in part on current specialist distribution within and across regions.

Related: Recurrent Multidrug Resistant Urinary Tract Infections in Geriatric Patients

Hand in hand with an aging veteran population is a growing clinical demand for urologic specialty care to treat urinary incontinence, prostate enlargement, and prostate cancer. Unfortunately, over 60% of U.S. counties lack a urologist, creating troublesome workforce issues.3 For these reasons, this study analyzed existing administrative data to understand regional variations in the distribution of and demands for the VHA urologist workforce. This study tested whether workforce distribution is balanced or imbalanced across regional networks, in part to inform whether the VHA should offer electronic or other national access to its urologic specialty care.

Methods

Fiscal year (FY) 2011 Specialty Physician Workforce Annual Report data from the VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing was used to characterize the distribution and concentration of urologists at 130 VHA facilities.5 The annual report provided a longitudinal management tool for reporting clinical productivity, efficiency, and staffing, and included benchmark data for each facility (eg, physician workforce, annual patient visits).

Demand for Urologic Specialty Care

The number of unique urology patients from the report was used as one approach to the demand for VHA urologic specialty care. This measure represented the number of unique patients evaluated in a urology clinic at least once over the FY. The number of newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer in calendar year 2010 within each VISN was also used as a more discrete measure of regional urologic care demand. Whereas care for other common urologic conditions, such as incontinence or prostate enlargement, may or may not be referred (ie, latent demand), prostate cancer care consistently involves urologists and is more specific for caseload.

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Because each VISN covered a relatively large geographic area, most with roughly equivalent numbers of facilities, there was no a priori reason to expect a difference in urologic workload and consequently urologic workforce between networks. On the other hand, within networks one might expect that urologists would be concentrated in hospitals that have more complicated patient cases, because the hospitals serve a tertiary or referral role. Yet even within a network, significant imbalances in specialist supply might require creative solutions to maintain adequate access of patients and PCPs to specialists.

Urologist Workforce

The full-time equivalent employee (FTEE) variable for urologic specialty care from the 2011 annual report was used as the primary outcome measure for urology workforce.5 This facility-level measure represented the clinical time urologists spent in direct patient care at each facility. It included the clinical effort of full-time as well as contract physicians and was also reported as an aggregate measure at the regional VISN level. Urologist workforce at the VISN level was the sum of all urologist FTEEs within its facilities. Adjusted rates also were provided (eg, FTEE/10,000 urology patients).

Other Workforce Factors

Also examined as covariates in the analysis were other measures related to urologist workforce. As the nation’s largest provider of graduate medical education, urology residents rotate through many VHA facilities, contributing to the workforce totals. For this reason, resident FTEE was examined as an independent variable in this study.

Understanding facility complexity (ie, case mix) was also essential for rational allocation of specialty care resources, as demand generally increases with increasing case mix. Therefore, a medical center group (MCG) case mix measure of complexity and its relationship with urologist workforce was examined. It was expected that increasing specialty care volume, resident staff, and facility complexity would be associated with increasing urologist workforce.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize VHA urology patients and urologist workforce within each regional VISN and its facilities. To better understand the relationship between case mix and urologist workforce, facilities were sorted according to MCG and characterized the unique urology patients, urologists, and residents at each level. Analysis of variance was used to test whether increasing MCG was associated with a higher number of urology patient caseloads. Multivariable linear regression models were then used to determine whether complexity was associated with urologist workforce after adjusting for resident and patient volume.

Related: Antibiotic Therapy and Bacterial Resistance in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury

Multilevel regression modeling, an extension of linear regression modeling suitable for partitioning the variation in an outcome variable attributable to different levels (ie, facility and VISN), was used to examine whether variation in the urologist workforce was primarily based at the facility or regional VISN level.6 This approach accounted for the potentially correlated nature of the data (ie, multiple facilities within each VISN) by incorporating a VISN-level random effect in the model. A random intercept model with no explanatory variables, known as an empty model, was used as the primary model.6 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) corresponding to the estimated variance components from the empty model was calculated to determine the portion of the total variation in unadjusted urologist workforce that occurs between VISNs.7 Prostate cancer caseload was then included to test whether allocation seemed to be driven by clinical need or other regional factors.

All analyses were performed using STATA, Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and all testing was 2-sided. The probability of a type I error was set at .05. This study protocol was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Results

Nearly 1 in 20 VHA patients (n = 274,152) were evaluated in a urology clinic at least once in FY 2011. It was found that 252.7 FTEE and 193.1 residents comprised the VHA urologist workforce (Table 1). Marked regional variation was found in unadjusted urologist staffing at both the facility and VISN levels. The urologist workforce ranged from 0.17 to 5.91 FTEEs across the 130 VHA facilities. At the VISN level, staffing varied over 5-fold (5.8 FTEEs in VISN 2 to 27.6 FTEEs in VISN 8).

Variation in the VHA urologist workforce distribution persisted even after standardizing by patient volume. The urologist workforce continued to vary from 0.94 to 9.95 FTEEs per 100,000 facility patients. This was even more dramatic when adjusted for volume of unique urology patients, ranging from 2.2 to 24.2 FTEE urologists per 10,000 urology patients (Figure).5 From the specialist perspective, each might serve 18 to 64 newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer annually, depending on the VISN.

Forty percent of urologists were located in 34 of the most complex facilities (Table 2). Urology patient caseload was associated with facility complexity in univariate analysis (P < .001). In the adjusted multivariable model, increasing facility complexity was associated with increasing urologist workforce (P < .001) as well as resident staffing (P < .001), but not with urology patient caseload (P = .27). The empty multilevel model indicated that 27.3% of variation in unadjusted urologist workforce (ICC = 0.273, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.098-0.448) was attributable to differences at the regional network level. After adjustment for VISN prostate cancer caseload, this decreased to 24.8% (ICC = 0.248; 95% CI, 0.076-0.419).

Discussion

The VHA urologist workforce served over 250,000 patients in FY 2011, and a substantial variation in workforce distribution at the facility and VISN levels was identified in this study. After adjusting for prostate cancer caseload as a proxy for clinical demand, there was some imbalance of urology specialists across regional networks, though most workforce variation occurred within networks in this integrated delivery system. Based on these findings, VHA specialty care initiatives should likely focus within regional networks rather than pursue electronic efforts nationally to improve specialty care access for patients and PCPs.

Regional variation in the VHA urologist workforce was expected, given a limited national supply of urologists and specialist preferences toward metropolitan areas.2-4 Overcoming this maldistribution has important implications for outcomes in many urologic disease processes.8-10 For example, counties with ≥ 1 urologist have up to a 20% reduction in bladder and prostate cancer-related mortality compared with those without a urologist.4 Moreover, the number of veterans with known urologic needs or currently receiving urologic specialty care likely significantly undercounts the total number who could benefit from this care. This is particularly true for facilities with fewer urology resources where patients may be less likely to get a referral, or if they are referred, it is likely outside VHA, creating fragmented care and potentially higher cost.

Understanding the urology workforce distribution, coupled with its sophisticated nationwide EMR, VHA has a unique opportunity to transform how urologic specialty care is delivered without moving around the current workforce. Based on these findings, the system could redistribute resources within each region to meet growing specialty care needs through telemedicine.

At least 2 innovative approaches are underway that might serve the system’s urology care needs: e-consults and the Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) video teleconsulting and education project.11,12 The first allows PCPs to request specialist review of the EMR, interpretation of the specific problem, and recommendation for a plan of care, which may or may not include a specialist visit.1,13 The second involves video conferences, which allow multiple PCPs from less complex facilities or rural areas to present cases to specialists from tertiary medical centers for real-time consultation and case-based learning. These initiatives could take advantage of the facility-based variation in urologist workforce by linking facilities with relatively generous urology resources with those with fewer resources to meet the needs of each region’s population and their PCPs while minimizing travel and wait times.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, FY 2011 data were used; notably, the VHA urologist workforce remained relatively stable from 2008 through 2011. Second, characteristics of individual VHA urologists, clinical productivity, and skill level were not examined. However, a 2008 study found that nearly all VHA urologists are board certified, mitigating skill level concerns.14 Third, it is possible that demand is partially driven by existence of resources, and there may be patients who might benefit from urologic care but who are not yet diagnosed. The analysis is conservative in this regard, in that demand may be greater than what was detected using the selected study methods. Last, this study examined specialist workforce within a single system. However, ensuring specialist resources are well distributed is a concern for most health systems, particularly in light of recent policy efforts, including accountable care organizations.15

Conclusion

Much of the variation in the VHA urologist workforce exists at the facility rather than the regional level. Optimizing the distribution of these specialty care resources could be achieved through novel care delivery models within each regional network that are well-aligned with current VHA initiatives. Successfully utilizing this workforce distribution has the potential to improve urologic care for veterans across the country and could be applied to improve access to all types of specialists in underserved and understaffed areas.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Skolarus is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 12-171).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

The VHA is the nation’s largest integrated health care delivery system, providing comprehensive medical care to about 6 million patients annually. In addition to revolutionizing its primary care delivery through widespread implementation of patient-centered medical homes (Patient Aligned Care Teams), the VHA is also transforming its specialty care delivery through use of its specialist workforce and innovative technologies, such as telemedicine and electronic consultations (e-consults).1

VHA specialty care is currently distributed using a hub and spoke model within larger regional networks spanning the U.S. This approach helps overcome geographic variation in specialist workforce (eg, predilection for metropolitan areas) but limits specialty care access for patients and primary care providers (PCPs) due to distance barriers.2-4 With the VHA electronic medical record (EMR) system, it is now feasible to send expertise electronically across the system (eg, e-consult). Whether this should occur at the regional VISN or national level to smooth out variation in specialist workforce depends in part on current specialist distribution within and across regions.

Related: Recurrent Multidrug Resistant Urinary Tract Infections in Geriatric Patients

Hand in hand with an aging veteran population is a growing clinical demand for urologic specialty care to treat urinary incontinence, prostate enlargement, and prostate cancer. Unfortunately, over 60% of U.S. counties lack a urologist, creating troublesome workforce issues.3 For these reasons, this study analyzed existing administrative data to understand regional variations in the distribution of and demands for the VHA urologist workforce. This study tested whether workforce distribution is balanced or imbalanced across regional networks, in part to inform whether the VHA should offer electronic or other national access to its urologic specialty care.

Methods

Fiscal year (FY) 2011 Specialty Physician Workforce Annual Report data from the VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing was used to characterize the distribution and concentration of urologists at 130 VHA facilities.5 The annual report provided a longitudinal management tool for reporting clinical productivity, efficiency, and staffing, and included benchmark data for each facility (eg, physician workforce, annual patient visits).

Demand for Urologic Specialty Care

The number of unique urology patients from the report was used as one approach to the demand for VHA urologic specialty care. This measure represented the number of unique patients evaluated in a urology clinic at least once over the FY. The number of newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer in calendar year 2010 within each VISN was also used as a more discrete measure of regional urologic care demand. Whereas care for other common urologic conditions, such as incontinence or prostate enlargement, may or may not be referred (ie, latent demand), prostate cancer care consistently involves urologists and is more specific for caseload.

Related: Prostate Cancer Survivorship Care

Because each VISN covered a relatively large geographic area, most with roughly equivalent numbers of facilities, there was no a priori reason to expect a difference in urologic workload and consequently urologic workforce between networks. On the other hand, within networks one might expect that urologists would be concentrated in hospitals that have more complicated patient cases, because the hospitals serve a tertiary or referral role. Yet even within a network, significant imbalances in specialist supply might require creative solutions to maintain adequate access of patients and PCPs to specialists.

Urologist Workforce

The full-time equivalent employee (FTEE) variable for urologic specialty care from the 2011 annual report was used as the primary outcome measure for urology workforce.5 This facility-level measure represented the clinical time urologists spent in direct patient care at each facility. It included the clinical effort of full-time as well as contract physicians and was also reported as an aggregate measure at the regional VISN level. Urologist workforce at the VISN level was the sum of all urologist FTEEs within its facilities. Adjusted rates also were provided (eg, FTEE/10,000 urology patients).

Other Workforce Factors

Also examined as covariates in the analysis were other measures related to urologist workforce. As the nation’s largest provider of graduate medical education, urology residents rotate through many VHA facilities, contributing to the workforce totals. For this reason, resident FTEE was examined as an independent variable in this study.

Understanding facility complexity (ie, case mix) was also essential for rational allocation of specialty care resources, as demand generally increases with increasing case mix. Therefore, a medical center group (MCG) case mix measure of complexity and its relationship with urologist workforce was examined. It was expected that increasing specialty care volume, resident staff, and facility complexity would be associated with increasing urologist workforce.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize VHA urology patients and urologist workforce within each regional VISN and its facilities. To better understand the relationship between case mix and urologist workforce, facilities were sorted according to MCG and characterized the unique urology patients, urologists, and residents at each level. Analysis of variance was used to test whether increasing MCG was associated with a higher number of urology patient caseloads. Multivariable linear regression models were then used to determine whether complexity was associated with urologist workforce after adjusting for resident and patient volume.

Related: Antibiotic Therapy and Bacterial Resistance in Patients With Spinal Cord Injury

Multilevel regression modeling, an extension of linear regression modeling suitable for partitioning the variation in an outcome variable attributable to different levels (ie, facility and VISN), was used to examine whether variation in the urologist workforce was primarily based at the facility or regional VISN level.6 This approach accounted for the potentially correlated nature of the data (ie, multiple facilities within each VISN) by incorporating a VISN-level random effect in the model. A random intercept model with no explanatory variables, known as an empty model, was used as the primary model.6 The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) corresponding to the estimated variance components from the empty model was calculated to determine the portion of the total variation in unadjusted urologist workforce that occurs between VISNs.7 Prostate cancer caseload was then included to test whether allocation seemed to be driven by clinical need or other regional factors.

All analyses were performed using STATA, Version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX), and all testing was 2-sided. The probability of a type I error was set at .05. This study protocol was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Research and Development Committee and Institutional Review Board.

Results

Nearly 1 in 20 VHA patients (n = 274,152) were evaluated in a urology clinic at least once in FY 2011. It was found that 252.7 FTEE and 193.1 residents comprised the VHA urologist workforce (Table 1). Marked regional variation was found in unadjusted urologist staffing at both the facility and VISN levels. The urologist workforce ranged from 0.17 to 5.91 FTEEs across the 130 VHA facilities. At the VISN level, staffing varied over 5-fold (5.8 FTEEs in VISN 2 to 27.6 FTEEs in VISN 8).

Variation in the VHA urologist workforce distribution persisted even after standardizing by patient volume. The urologist workforce continued to vary from 0.94 to 9.95 FTEEs per 100,000 facility patients. This was even more dramatic when adjusted for volume of unique urology patients, ranging from 2.2 to 24.2 FTEE urologists per 10,000 urology patients (Figure).5 From the specialist perspective, each might serve 18 to 64 newly diagnosed patients with prostate cancer annually, depending on the VISN.

Forty percent of urologists were located in 34 of the most complex facilities (Table 2). Urology patient caseload was associated with facility complexity in univariate analysis (P < .001). In the adjusted multivariable model, increasing facility complexity was associated with increasing urologist workforce (P < .001) as well as resident staffing (P < .001), but not with urology patient caseload (P = .27). The empty multilevel model indicated that 27.3% of variation in unadjusted urologist workforce (ICC = 0.273, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.098-0.448) was attributable to differences at the regional network level. After adjustment for VISN prostate cancer caseload, this decreased to 24.8% (ICC = 0.248; 95% CI, 0.076-0.419).

Discussion

The VHA urologist workforce served over 250,000 patients in FY 2011, and a substantial variation in workforce distribution at the facility and VISN levels was identified in this study. After adjusting for prostate cancer caseload as a proxy for clinical demand, there was some imbalance of urology specialists across regional networks, though most workforce variation occurred within networks in this integrated delivery system. Based on these findings, VHA specialty care initiatives should likely focus within regional networks rather than pursue electronic efforts nationally to improve specialty care access for patients and PCPs.

Regional variation in the VHA urologist workforce was expected, given a limited national supply of urologists and specialist preferences toward metropolitan areas.2-4 Overcoming this maldistribution has important implications for outcomes in many urologic disease processes.8-10 For example, counties with ≥ 1 urologist have up to a 20% reduction in bladder and prostate cancer-related mortality compared with those without a urologist.4 Moreover, the number of veterans with known urologic needs or currently receiving urologic specialty care likely significantly undercounts the total number who could benefit from this care. This is particularly true for facilities with fewer urology resources where patients may be less likely to get a referral, or if they are referred, it is likely outside VHA, creating fragmented care and potentially higher cost.

Understanding the urology workforce distribution, coupled with its sophisticated nationwide EMR, VHA has a unique opportunity to transform how urologic specialty care is delivered without moving around the current workforce. Based on these findings, the system could redistribute resources within each region to meet growing specialty care needs through telemedicine.

At least 2 innovative approaches are underway that might serve the system’s urology care needs: e-consults and the Specialty Care Access Network-Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) video teleconsulting and education project.11,12 The first allows PCPs to request specialist review of the EMR, interpretation of the specific problem, and recommendation for a plan of care, which may or may not include a specialist visit.1,13 The second involves video conferences, which allow multiple PCPs from less complex facilities or rural areas to present cases to specialists from tertiary medical centers for real-time consultation and case-based learning. These initiatives could take advantage of the facility-based variation in urologist workforce by linking facilities with relatively generous urology resources with those with fewer resources to meet the needs of each region’s population and their PCPs while minimizing travel and wait times.

Limitations

This study should be interpreted in the context of several limitations. First, FY 2011 data were used; notably, the VHA urologist workforce remained relatively stable from 2008 through 2011. Second, characteristics of individual VHA urologists, clinical productivity, and skill level were not examined. However, a 2008 study found that nearly all VHA urologists are board certified, mitigating skill level concerns.14 Third, it is possible that demand is partially driven by existence of resources, and there may be patients who might benefit from urologic care but who are not yet diagnosed. The analysis is conservative in this regard, in that demand may be greater than what was detected using the selected study methods. Last, this study examined specialist workforce within a single system. However, ensuring specialist resources are well distributed is a concern for most health systems, particularly in light of recent policy efforts, including accountable care organizations.15

Conclusion

Much of the variation in the VHA urologist workforce exists at the facility rather than the regional level. Optimizing the distribution of these specialty care resources could be achieved through novel care delivery models within each regional network that are well-aligned with current VHA initiatives. Successfully utilizing this workforce distribution has the potential to improve urologic care for veterans across the country and could be applied to improve access to all types of specialists in underserved and understaffed areas.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Skolarus is supported by a VA HSR&D Career Development Award (CDA 12-171).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Graham GD; Office of Specialty Care Transformation, Department of Veterans Affairs Patient Care Services. Specialty care transformation initiatives. http://www.pva.org/atf/cf/%7BCA2A0FFB-6859 -4BC1-BC96-6B57F57F0391%7D/Friday_Graham_Specialty%20Care%20Transformation%20Initiatives.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed February 3, 2015.

2. Neuwahl S, Thompson K, Fraher E, Ricketts T. HPRI data tracks. Urology workforce trends. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2012;97(1):46-49.

3. Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol. 2009;181(2):760-765; discussion 765-766.

4. Odisho AY, Cooperberg MR, Fradet V, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Urologist density and county-level urologic cancer mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2499-2504.

5. Fiscal Year 2011 VHA Physician Workforce & Support Staff Data. VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, & Staffing Website. https://opes.vscc.med.va.gov. Published December 2011.

6. Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc;1999.

7. Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1159-1180.

8. Weiner DM, McDaniel R, Lowe FC. Urologic manpower issues for the 21st century: Assessing the impact of changing population demographics. Urology. 1997;49(3):335-342.

9. Gee WF, Holtgrewe HL, Albertsen PC, et al. Subspecialization, recruitment and retirement trends of American urologists. J Urol. 1998;159(2): 509-511.

10. McCullough DL. Manpower needs in urology in the twenty-first century. Urol Clin North Am. 1998;25(1):15-22.

11. Saifu HN, Asch SM, Goetz MB, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):207-212.

12. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

13. Hysong SJ, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: A qualitative analysis. Implement Sci. 2011;6:84.

14. Tyson MD, Lerner LB. Profile of the veterans affairs urologist: Results from a national survey. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1460-1462.

15. Landon BE, Roberts DH. Reenvisioning specialty care and payment under global payment systems. JAMA. 2013;310(4):371-372.

1. Graham GD; Office of Specialty Care Transformation, Department of Veterans Affairs Patient Care Services. Specialty care transformation initiatives. http://www.pva.org/atf/cf/%7BCA2A0FFB-6859 -4BC1-BC96-6B57F57F0391%7D/Friday_Graham_Specialty%20Care%20Transformation%20Initiatives.pdf. Published December 2011. Accessed February 3, 2015.

2. Neuwahl S, Thompson K, Fraher E, Ricketts T. HPRI data tracks. Urology workforce trends. Bull Am Coll Surg. 2012;97(1):46-49.

3. Odisho AY, Fradet V, Cooperberg MR, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Geographic distribution of urologists throughout the United States using a county level approach. J Urol. 2009;181(2):760-765; discussion 765-766.

4. Odisho AY, Cooperberg MR, Fradet V, Ahmad AE, Carroll PR. Urologist density and county-level urologic cancer mortality. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(15):2499-2504.

5. Fiscal Year 2011 VHA Physician Workforce & Support Staff Data. VHA Office of Productivity, Efficiency, & Staffing Website. https://opes.vscc.med.va.gov. Published December 2011.

6. Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc;1999.

7. Krein SL, Hofer TP, Kerr EA, Hayward RA. Whom should we profile? Examining diabetes care practice variation among primary care providers, provider groups, and health care facilities. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1159-1180.

8. Weiner DM, McDaniel R, Lowe FC. Urologic manpower issues for the 21st century: Assessing the impact of changing population demographics. Urology. 1997;49(3):335-342.

9. Gee WF, Holtgrewe HL, Albertsen PC, et al. Subspecialization, recruitment and retirement trends of American urologists. J Urol. 1998;159(2): 509-511.

10. McCullough DL. Manpower needs in urology in the twenty-first century. Urol Clin North Am. 1998;25(1):15-22.

11. Saifu HN, Asch SM, Goetz MB, et al. Evaluation of human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C telemedicine clinics. Am J Manag Care. 2012;18(4):207-212.

12. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

13. Hysong SJ, Esquivel A, Sittig DF, et al. Towards successful coordination of electronic health record based-referrals: A qualitative analysis. Implement Sci. 2011;6:84.

14. Tyson MD, Lerner LB. Profile of the veterans affairs urologist: Results from a national survey. J Urol. 2008;180(4):1460-1462.

15. Landon BE, Roberts DH. Reenvisioning specialty care and payment under global payment systems. JAMA. 2013;310(4):371-372.