User login

“Thank You for Not Letting Me Crash and Burn”: The Imperative of Quality Physician Onboarding to Foster Job Satisfaction, Strengthen Workplace Culture, and Advance the Quadruple Aim

From The Ohio State University College of Medicine Department of Family and Community Medicine, Columbus, OH (Candy Magaña, Jná Báez, Christine Junk, Drs. Ahmad, Conroy, and Olayiwola); The Ohio State University College of Medicine Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation (Candy Magaña, Jná Báez, and Dr. Olayiwola); and The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center (Christine Harsh, Erica Esposito).

Much has been discussed about the growing crisis of professional dissatisfaction among physicians, with increasing efforts being made to incorporate physician wellness into health system strategies that move from the Triple to the Quadruple Aim.1 For many years, our health care system has been focused on improving the health of populations, optimizing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care (Triple Aim). The inclusion of the fourth aim, improving the experience of the teams that deliver care, has become paramount in achieving the other aims.

An area often overlooked in this focus on wellness, however, is the importance of the earliest days of employment to shape and predict long-term career contentment. This is a missed opportunity, as data suggest that organizations with standardized onboarding programs boast a 62% increased productivity rate and a 50% greater retention rate among new hires.2,3 Moreover, a study by the International Institute for Management Development found that businesses lose an estimated $37 billion annually because employees do not fully understand their jobs.4 The report ties losses to “actions taken by employees who have misunderstood or misinterpreted company policies, business processes, job function, or a combination of the three.” Additionally, onboarding programs that focus strictly on technical or functional orientation tasks miss important opportunities for culture integration during the onboarding process.5 It is therefore imperative to look to effective models of employee onboarding to develop systems that position physicians and practices for success.

Challenges With Traditional Physician Onboarding

In recent years, the Department of Family and Community Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine has experienced rapid organizational change. Like many primary care systems nationwide responding to disruption in health care and changing demands on the clinical workforce, the department has hired new leadership, revised strategic priorities, and witnessed an influx of faculty and staff. It has also planned an expansion of ambulatory services that will more than double the clinical workforce over the next 3 years. While an exciting time, there has been a growing need to align strategy, culture, and human capital during these changes.

As we entered this phase of transformation, we recognized that our highly individualized, ad hoc orientation system presented shortcomings. During the act of revamping our physician recruitment process, stakeholder workgroup members specifically noted that improvement efforts were needed regarding new physician orientation, as no consistent structures were previously in place. New physician orientation had been a major gap for years, resulting in dissatisfaction in the first few months of physician practice, early physician turnover, and staff frustration. For physicians, we continued to learn about their frustration and unanswered questions regarding expectations, norms, structures, and processes.

Many new hires were left with a kind of “trial by fire” entry into their roles. On the first day of clinic, a new physician would most likely need to simultaneously see patients, learn the nuances of the electronic health record (EHR), figure out where the break room was located, and quickly learn population health issues for the patients they were serving. Opportunities to meet key clinic site leadership would be at random, and new physicians might not have the opportunity to meet leadership or staff until months into their tenure; this did not allow for a sense of belonging or understanding of the many resources available to them. We learned that the quality of these ad hoc orientations also varied based on the experience and priorities of each practice’s clinic and administrative leaders, who themselves felt ill-equipped to provide a consistent, robust, and confidence-building experience. In addition, practice site management was rarely given advance time to prepare for the arrival of new physicians, which resulted in physicians perceiving practices to be unwelcoming and disorganized. Their first days were often spent with patients in clinic with no structured orientation and without understanding workflows or having systems practice knowledge.

Institutionally, the interview process satisfied some transfer of knowledge, but we were unclear of what was being consistently shared and understood in the multiple ambulatory locations where our physicians enter practice. More importantly, we knew we were missing a critical opportunity to use orientation to imbue other values of diversity and inclusion, health equity, and operational excellence into the workforce. Based on anecdotal insights from employees and our own review of successful onboarding approaches from other industries, we also knew a more structured welcoming process would predict greater long-term career satisfaction for physicians and create a foundation for providing optimal care for patients when clinical encounters began.

Reengineering Physician Onboarding

In 2019, our department developed a multipronged approach to physician onboarding, which is already paying dividends in easing acculturation and fostering team cohesion. The department tapped its Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation (PCIT) to direct this effort, based on its expertise in practice transformation, clinical transformation and adaptations, and workflow efficiency through process and quality improvement. The PCIT team provides support to the department and the entire health system focused on technology and innovation, health equity, and health care efficiency.6 They applied many of the tools used in the Clinical Transformation in Technology approach to lead this initiative.7

The PCIT team began identifying key stakeholders (department, clinical and ambulatory leadership, clinicians and clinical staff, community partners, human resources, and resident physicians), and then engaging those individuals in dialogue surrounding orientation needs. During scheduled in-person and virtual work sessions, stakeholders were asked to provide input on pain points for new physicians and clinic leadership and were then empowered to create an onboarding program. Applying health care quality improvement techniques, we leveraged workflow mapping, current and future state planning, and goal setting, led by the skilled process improvement and clinical transformation specialists. We coordinated a multidisciplinary process improvement team that included clinic administrators, medical directors, human resources, administrative staff, ambulatory and resident leadership, clinical leadership, and recruitment liaisons. This diverse group of leadership and staff was brought together to address these critical identified gaps and weaknesses in new physician onboarding.

Through a series of learning sessions, the workgroup provided input that was used to form an itemized physician onboarding schedule, which was then leveraged to develop Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, collecting feedback in real time. Some issues that seem small can cause major distress for new physicians. For example, in our inaugural orientation implementation, a physician provided feedback that they wanted to obtain information on setting up their work email on their personal devices and was having considerable trouble figuring out how to do so. This particular topic was not initially included in the first iteration of the Department’s orientation program. We rapidly sought out different ways to embed that into the onboarding experience. The first PDSA involved integrating the university information technology team (IT) into the process but was not successful because it required extra work for the new physician and reliance on the IT schedule. The next attempt was to have IT train a department staff member, but again, this still required that the physician find time to connect with that staff member. Finally, we decided to obtain a useful tip sheet that clearly outlined the process and could be included in orientation materials. This gave the new physicians control over how and when they would work on this issue. Based on these learnings, this was incorporated as a standing agenda item and resource for incoming physicians.

Essential Elements of Effective Onboarding

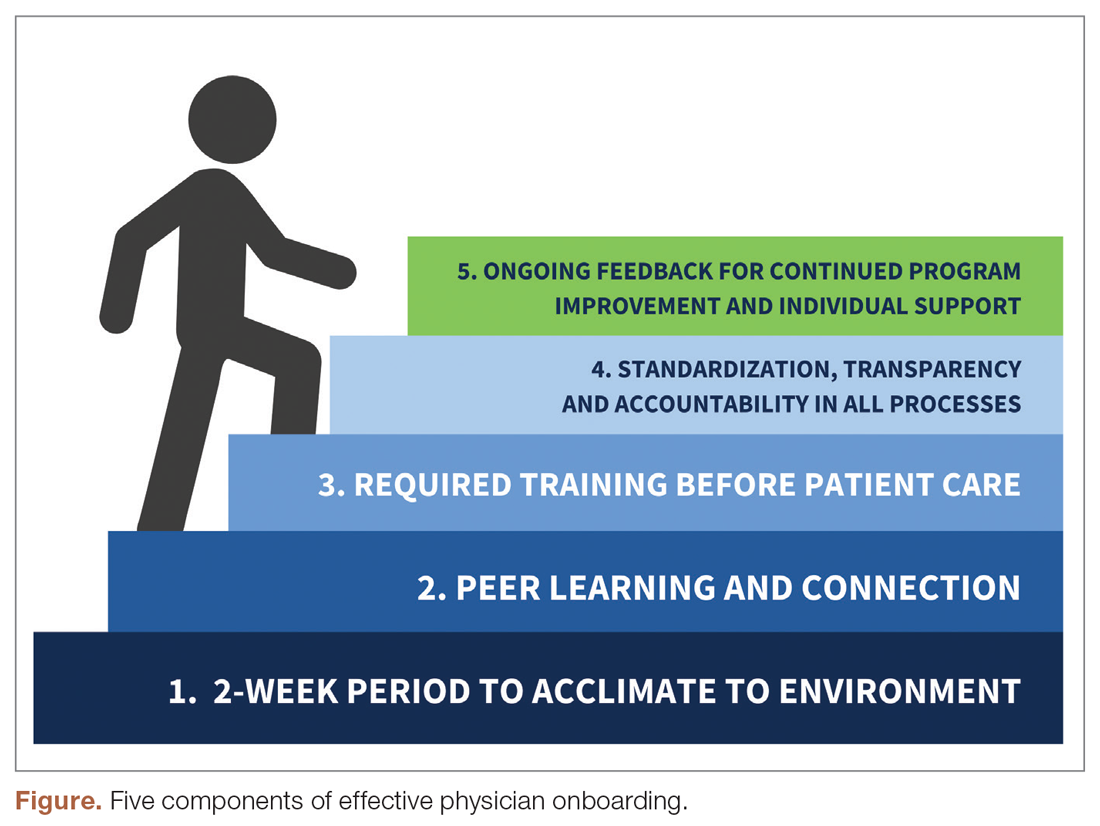

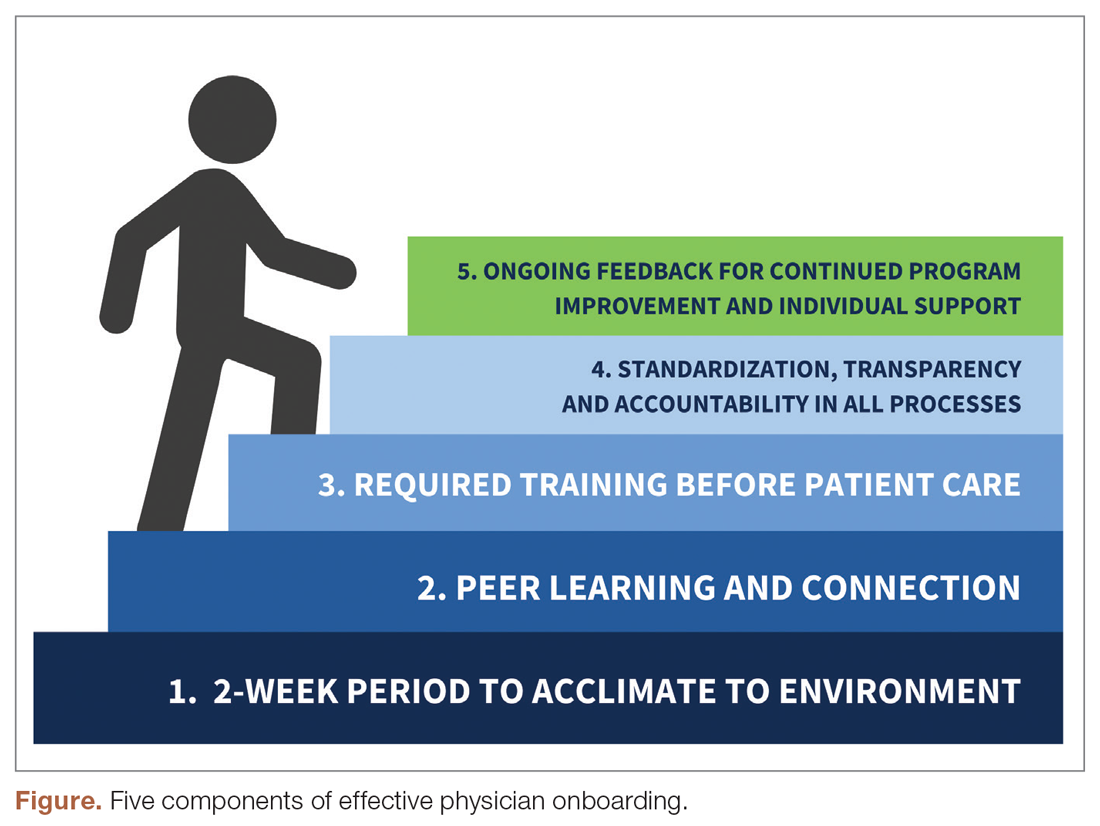

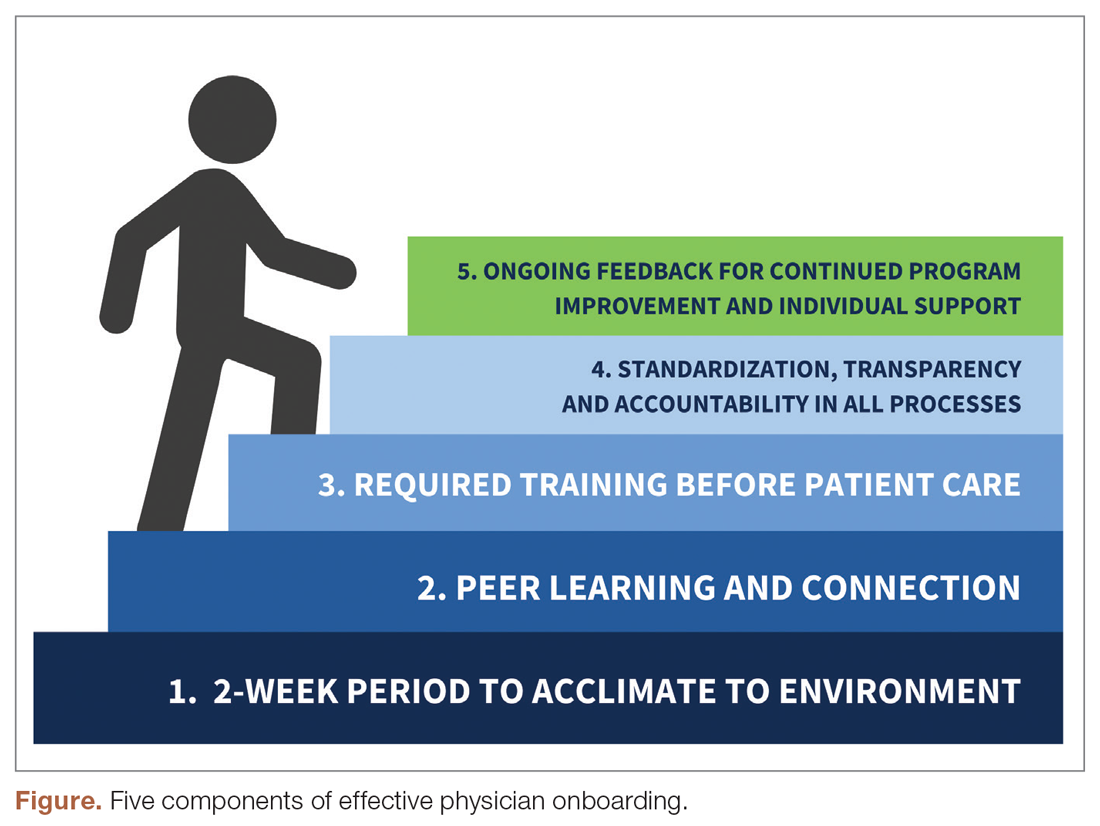

The new physician onboarding program consists of 5 key elements: (1) 2-week acclimation period; (2) peer learning and connection; (3) training before beginning patient care; (4) standardization, transparency, and accountability in all processes; (5) ongoing feedback for continued program improvement with individual support (Figure).

The program begins with a 2-week period of intentional investment in individual success, during which time no patients are scheduled. In week 1, we work with new hires to set expectations for performance, understand departmental norms, and introduce culture. Physicians meet formally and informally with department and institutional leadership, as well as attend team meetings and trainings that include a range of administrative and compliance requirements, such as quality standards and expectations, compliance, billing and coding specific to family medicine, EHR management, and institutionally mandated orientations. We are also adding implicit bias and antiracism training during this period, which are essential to creating a culture of unity and belonging.

During week 2, we focus on clinic-level orientation, assigning new hires an orientation buddy and a department sponsor, such as a physician lead or medical director. Physicians spend time with leadership at their clinic as they nurture relationships important for mentorship, sponsorship, and peer support. They also meet care team members, including front desk associates, medical assistants, behavioral health clinicians, nutritionists, social workers, pharmacists, and other key colleagues and care team members. This introduces the physician to the clinical environment and physical space as well as acclimates the physician to workflows and feedback loops for regular interaction.

When physicians ultimately begin patient care, they begin with an expected productivity rate of 50%, followed by an expected productivity rate of 75%, and then an expected productivity rate of 100%. This steady increase occurs over 3 to 4 weeks depending on the physician’s comfort level. They are also provided monthly reports on work relative value unit performance so that they can track and adapt practice patterns as necessary.More details on the program can be found in Appendix 1.

Takeaways From the Implementation of the New Program

Give time for new physicians to focus on acclimating to the role and environment.

The initial 2-week period of transition—without direct patient care—ensures that physicians feel comfortable in their new ecosystem. This also supports personal transitions, as many new hires are managing relocation and acclimating themselves and their families to new settings. Even residents from our training program who returned as attending physicians found this flexibility and slow reentry essential. This also gives the clinic time to orient to an additional provider, nurture them into the team culture, and develop relationships with the care team.

Cultivate spaces for shared learning, problem-solving, and peer connection.

Orientation is delivered primarily through group learning sessions with cohorts of new physicians, thus developing spaces for networking, fostering psychological safety, encouraging personal and professional rapport, emphasizing interactive learning, and reinforcing scheduling blocks at the departmental level. New hires also participate in peer shadowing to develop clinical competencies and are assigned a workplace buddy to foster a sense of belonging and create opportunities for additional knowledge sharing and cross-training.

Strengthen physician knowledge base, confidence, and comfort in the workplace before beginning direct patient care.

Without fluency in the workflows, culture, and operations of a practice, the urgency to have physicians begin clinical care can result in frustration for the physician, patients, and clinical and administrative staff. Therefore, we complete essential training prior to seeing any patients. This includes clinical workflows, referral processes, use of alternate modalities of care (eg, telehealth, eConsults), billing protocols, population health training, patient resources, office resources, and other essential daily processes and tools. This creates efficiency in administrative management, increased productivity, and better understanding of resources available for patients’ medical, social, and behavioral needs when patient care begins.

Embrace standardization, transparency, and accountability in as many processes as possible.

Standardized knowledge-sharing and checklists are mandated at every step of the orientation process, requiring sign off from the physician lead, practice manager, and new physicians upon completion. This offers all parties the opportunity to play a role in the delivery of and accountability for skills transfer and empowers new hires to press pause if they feel unsure about any domain in the training. It is also essential in guaranteeing that all physicians—regardless of which ambulatory location they practice in—receive consistent information and expectations. A sample checklist can be found in Appendix 2.

Commit to collecting and acting on feedback for continued program improvement and individual support.

As physicians complete the program, it is necessary to create structures to measure and enhance its impact, as well as evaluate how physicians are faring following the program. Each physician completes surveys at the end of the orientation program, attends a 90-day post-program check-in with the department chair, and receives follow-up trainings on advanced topics as they become more deeply embedded in the organization.

Lessons Learned

Feedback from surveys and 90-day check-ins with leadership and physicians reflect a high degree of clarity on job roles and duties, a sense of team camaraderie, easier system navigation, and a strong sense of support. We do recognize that sustaining change takes time and our study is limited by data demonstrating the impact of these efforts. We look forward to sharing more robust data from surveys and qualitative interviews with physicians, clinical leadership, and staff in the future. Our team will conduct interviews at 90-day and 180-day checkpoints with new physicians who have gone through this program, followed by a check-in after 1 year. Additionally, new physicians as well as key stakeholders, such as physician leads, practice managers, and members of the recruitment team, have started to participate in short surveys. These are designed to better understand their experiences, what worked well, what can be improved, and the overall satisfaction of the physician and other members of the extended care team.

What follows are some comments made by the initial group of physicians that went through this program and participated in follow-up interviews:

“I really feel like part of a bigger team.”

“I knew exactly what do to when I walked into the exam room on clinic Day 1.”

“It was great to make deep connections during the early process of joining.”

“Having a buddy to direct questions and ideas to is amazing and empowering.”

“Even though the orientation was long, I felt that I learned so much that I would not have otherwise.”

“Thank you for not letting me crash and burn!”

“Great culture! I love understanding our values of health equity, diversity, and inclusion.”

In the months since our endeavor began, we have learned just how essential it is to fully and effectively integrate new hires into the organization for their own satisfaction and success—and ours. Indeed, we cannot expect to achieve the Quadruple Aim without investing in the kind of transparent and intentional orientation process that defines expectations, aligns cultural values, mitigates costly and stressful operational misunderstandings, and communicates to physicians that, not only do they belong, but their sense of belonging is our priority. While we have yet to understand the impact of this program on the fourth aim of the Quadruple Aim, we are hopeful that the benefits will be far-reaching.

It is our ultimate hope that programs like this: (1) give physicians the confidence needed to create impactful patient-centered experiences; (2) enable physicians to become more cost-effective and efficient in care delivery; (3) allow physicians to understand the populations they are serving and access tools available to mitigate health disparities and other barriers; and (4) improve the collective experience of every member of the care team, practice leadership, and clinician-patient partnership.

Corresponding author: J. Nwando Olayiwola, MD, MPH, FAAFP, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 2231 N High St, Ste 250, Columbus, OH 43210; nwando.olayiwola@osumc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Keywords: physician onboarding; Quadruple Aim; leadership; clinician satisfaction; care team satisfaction.

1. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6): 573-576.

2. Maurer R. Onboarding key to retaining, engaging talent. Society for Human Resource Management. April 16, 2015. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/onboarding-key-retaining-engaging-talent.aspx

3. Boston AG. New hire onboarding standardization and automation powers productivity gains. GlobeNewswire. March 8, 2011. Accessed January 8, 2021. http://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2011/03/08/994239/0/en/New-Hire-Onboarding-Standardization-and-Automation-Powers-Productivity-Gains.html

4. $37 billion – US and UK business count the cost of employee misunderstanding. HR.com – Maximizing Human Potential. June 18, 2008. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.hr.com/en/communities/staffing_and_recruitment/37-billion---us-and-uk-businesses-count-the-cost-o_fhnduq4d.html

5. Employers risk driving new hires away with poor onboarding. Society for Human Resource Management. February 23, 2018. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/employers-new-hires-poor-onboarding.aspx

6. Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation. The Ohio State University College of Medicine. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/departments/family-medicine/pcit

7. Olayiwola, J.N. and Magaña, C. Clinical transformation in technology: a fresh change management approach for primary care. Harvard Health Policy Review. February 2, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2021. http://www.hhpronline.org/articles/2019/2/2/clinical-transformation-in-technology-a-fresh-change-management-approach-for-primary-care

From The Ohio State University College of Medicine Department of Family and Community Medicine, Columbus, OH (Candy Magaña, Jná Báez, Christine Junk, Drs. Ahmad, Conroy, and Olayiwola); The Ohio State University College of Medicine Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation (Candy Magaña, Jná Báez, and Dr. Olayiwola); and The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center (Christine Harsh, Erica Esposito).

Much has been discussed about the growing crisis of professional dissatisfaction among physicians, with increasing efforts being made to incorporate physician wellness into health system strategies that move from the Triple to the Quadruple Aim.1 For many years, our health care system has been focused on improving the health of populations, optimizing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care (Triple Aim). The inclusion of the fourth aim, improving the experience of the teams that deliver care, has become paramount in achieving the other aims.

An area often overlooked in this focus on wellness, however, is the importance of the earliest days of employment to shape and predict long-term career contentment. This is a missed opportunity, as data suggest that organizations with standardized onboarding programs boast a 62% increased productivity rate and a 50% greater retention rate among new hires.2,3 Moreover, a study by the International Institute for Management Development found that businesses lose an estimated $37 billion annually because employees do not fully understand their jobs.4 The report ties losses to “actions taken by employees who have misunderstood or misinterpreted company policies, business processes, job function, or a combination of the three.” Additionally, onboarding programs that focus strictly on technical or functional orientation tasks miss important opportunities for culture integration during the onboarding process.5 It is therefore imperative to look to effective models of employee onboarding to develop systems that position physicians and practices for success.

Challenges With Traditional Physician Onboarding

In recent years, the Department of Family and Community Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine has experienced rapid organizational change. Like many primary care systems nationwide responding to disruption in health care and changing demands on the clinical workforce, the department has hired new leadership, revised strategic priorities, and witnessed an influx of faculty and staff. It has also planned an expansion of ambulatory services that will more than double the clinical workforce over the next 3 years. While an exciting time, there has been a growing need to align strategy, culture, and human capital during these changes.

As we entered this phase of transformation, we recognized that our highly individualized, ad hoc orientation system presented shortcomings. During the act of revamping our physician recruitment process, stakeholder workgroup members specifically noted that improvement efforts were needed regarding new physician orientation, as no consistent structures were previously in place. New physician orientation had been a major gap for years, resulting in dissatisfaction in the first few months of physician practice, early physician turnover, and staff frustration. For physicians, we continued to learn about their frustration and unanswered questions regarding expectations, norms, structures, and processes.

Many new hires were left with a kind of “trial by fire” entry into their roles. On the first day of clinic, a new physician would most likely need to simultaneously see patients, learn the nuances of the electronic health record (EHR), figure out where the break room was located, and quickly learn population health issues for the patients they were serving. Opportunities to meet key clinic site leadership would be at random, and new physicians might not have the opportunity to meet leadership or staff until months into their tenure; this did not allow for a sense of belonging or understanding of the many resources available to them. We learned that the quality of these ad hoc orientations also varied based on the experience and priorities of each practice’s clinic and administrative leaders, who themselves felt ill-equipped to provide a consistent, robust, and confidence-building experience. In addition, practice site management was rarely given advance time to prepare for the arrival of new physicians, which resulted in physicians perceiving practices to be unwelcoming and disorganized. Their first days were often spent with patients in clinic with no structured orientation and without understanding workflows or having systems practice knowledge.

Institutionally, the interview process satisfied some transfer of knowledge, but we were unclear of what was being consistently shared and understood in the multiple ambulatory locations where our physicians enter practice. More importantly, we knew we were missing a critical opportunity to use orientation to imbue other values of diversity and inclusion, health equity, and operational excellence into the workforce. Based on anecdotal insights from employees and our own review of successful onboarding approaches from other industries, we also knew a more structured welcoming process would predict greater long-term career satisfaction for physicians and create a foundation for providing optimal care for patients when clinical encounters began.

Reengineering Physician Onboarding

In 2019, our department developed a multipronged approach to physician onboarding, which is already paying dividends in easing acculturation and fostering team cohesion. The department tapped its Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation (PCIT) to direct this effort, based on its expertise in practice transformation, clinical transformation and adaptations, and workflow efficiency through process and quality improvement. The PCIT team provides support to the department and the entire health system focused on technology and innovation, health equity, and health care efficiency.6 They applied many of the tools used in the Clinical Transformation in Technology approach to lead this initiative.7

The PCIT team began identifying key stakeholders (department, clinical and ambulatory leadership, clinicians and clinical staff, community partners, human resources, and resident physicians), and then engaging those individuals in dialogue surrounding orientation needs. During scheduled in-person and virtual work sessions, stakeholders were asked to provide input on pain points for new physicians and clinic leadership and were then empowered to create an onboarding program. Applying health care quality improvement techniques, we leveraged workflow mapping, current and future state planning, and goal setting, led by the skilled process improvement and clinical transformation specialists. We coordinated a multidisciplinary process improvement team that included clinic administrators, medical directors, human resources, administrative staff, ambulatory and resident leadership, clinical leadership, and recruitment liaisons. This diverse group of leadership and staff was brought together to address these critical identified gaps and weaknesses in new physician onboarding.

Through a series of learning sessions, the workgroup provided input that was used to form an itemized physician onboarding schedule, which was then leveraged to develop Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, collecting feedback in real time. Some issues that seem small can cause major distress for new physicians. For example, in our inaugural orientation implementation, a physician provided feedback that they wanted to obtain information on setting up their work email on their personal devices and was having considerable trouble figuring out how to do so. This particular topic was not initially included in the first iteration of the Department’s orientation program. We rapidly sought out different ways to embed that into the onboarding experience. The first PDSA involved integrating the university information technology team (IT) into the process but was not successful because it required extra work for the new physician and reliance on the IT schedule. The next attempt was to have IT train a department staff member, but again, this still required that the physician find time to connect with that staff member. Finally, we decided to obtain a useful tip sheet that clearly outlined the process and could be included in orientation materials. This gave the new physicians control over how and when they would work on this issue. Based on these learnings, this was incorporated as a standing agenda item and resource for incoming physicians.

Essential Elements of Effective Onboarding

The new physician onboarding program consists of 5 key elements: (1) 2-week acclimation period; (2) peer learning and connection; (3) training before beginning patient care; (4) standardization, transparency, and accountability in all processes; (5) ongoing feedback for continued program improvement with individual support (Figure).

The program begins with a 2-week period of intentional investment in individual success, during which time no patients are scheduled. In week 1, we work with new hires to set expectations for performance, understand departmental norms, and introduce culture. Physicians meet formally and informally with department and institutional leadership, as well as attend team meetings and trainings that include a range of administrative and compliance requirements, such as quality standards and expectations, compliance, billing and coding specific to family medicine, EHR management, and institutionally mandated orientations. We are also adding implicit bias and antiracism training during this period, which are essential to creating a culture of unity and belonging.

During week 2, we focus on clinic-level orientation, assigning new hires an orientation buddy and a department sponsor, such as a physician lead or medical director. Physicians spend time with leadership at their clinic as they nurture relationships important for mentorship, sponsorship, and peer support. They also meet care team members, including front desk associates, medical assistants, behavioral health clinicians, nutritionists, social workers, pharmacists, and other key colleagues and care team members. This introduces the physician to the clinical environment and physical space as well as acclimates the physician to workflows and feedback loops for regular interaction.

When physicians ultimately begin patient care, they begin with an expected productivity rate of 50%, followed by an expected productivity rate of 75%, and then an expected productivity rate of 100%. This steady increase occurs over 3 to 4 weeks depending on the physician’s comfort level. They are also provided monthly reports on work relative value unit performance so that they can track and adapt practice patterns as necessary.More details on the program can be found in Appendix 1.

Takeaways From the Implementation of the New Program

Give time for new physicians to focus on acclimating to the role and environment.

The initial 2-week period of transition—without direct patient care—ensures that physicians feel comfortable in their new ecosystem. This also supports personal transitions, as many new hires are managing relocation and acclimating themselves and their families to new settings. Even residents from our training program who returned as attending physicians found this flexibility and slow reentry essential. This also gives the clinic time to orient to an additional provider, nurture them into the team culture, and develop relationships with the care team.

Cultivate spaces for shared learning, problem-solving, and peer connection.

Orientation is delivered primarily through group learning sessions with cohorts of new physicians, thus developing spaces for networking, fostering psychological safety, encouraging personal and professional rapport, emphasizing interactive learning, and reinforcing scheduling blocks at the departmental level. New hires also participate in peer shadowing to develop clinical competencies and are assigned a workplace buddy to foster a sense of belonging and create opportunities for additional knowledge sharing and cross-training.

Strengthen physician knowledge base, confidence, and comfort in the workplace before beginning direct patient care.

Without fluency in the workflows, culture, and operations of a practice, the urgency to have physicians begin clinical care can result in frustration for the physician, patients, and clinical and administrative staff. Therefore, we complete essential training prior to seeing any patients. This includes clinical workflows, referral processes, use of alternate modalities of care (eg, telehealth, eConsults), billing protocols, population health training, patient resources, office resources, and other essential daily processes and tools. This creates efficiency in administrative management, increased productivity, and better understanding of resources available for patients’ medical, social, and behavioral needs when patient care begins.

Embrace standardization, transparency, and accountability in as many processes as possible.

Standardized knowledge-sharing and checklists are mandated at every step of the orientation process, requiring sign off from the physician lead, practice manager, and new physicians upon completion. This offers all parties the opportunity to play a role in the delivery of and accountability for skills transfer and empowers new hires to press pause if they feel unsure about any domain in the training. It is also essential in guaranteeing that all physicians—regardless of which ambulatory location they practice in—receive consistent information and expectations. A sample checklist can be found in Appendix 2.

Commit to collecting and acting on feedback for continued program improvement and individual support.

As physicians complete the program, it is necessary to create structures to measure and enhance its impact, as well as evaluate how physicians are faring following the program. Each physician completes surveys at the end of the orientation program, attends a 90-day post-program check-in with the department chair, and receives follow-up trainings on advanced topics as they become more deeply embedded in the organization.

Lessons Learned

Feedback from surveys and 90-day check-ins with leadership and physicians reflect a high degree of clarity on job roles and duties, a sense of team camaraderie, easier system navigation, and a strong sense of support. We do recognize that sustaining change takes time and our study is limited by data demonstrating the impact of these efforts. We look forward to sharing more robust data from surveys and qualitative interviews with physicians, clinical leadership, and staff in the future. Our team will conduct interviews at 90-day and 180-day checkpoints with new physicians who have gone through this program, followed by a check-in after 1 year. Additionally, new physicians as well as key stakeholders, such as physician leads, practice managers, and members of the recruitment team, have started to participate in short surveys. These are designed to better understand their experiences, what worked well, what can be improved, and the overall satisfaction of the physician and other members of the extended care team.

What follows are some comments made by the initial group of physicians that went through this program and participated in follow-up interviews:

“I really feel like part of a bigger team.”

“I knew exactly what do to when I walked into the exam room on clinic Day 1.”

“It was great to make deep connections during the early process of joining.”

“Having a buddy to direct questions and ideas to is amazing and empowering.”

“Even though the orientation was long, I felt that I learned so much that I would not have otherwise.”

“Thank you for not letting me crash and burn!”

“Great culture! I love understanding our values of health equity, diversity, and inclusion.”

In the months since our endeavor began, we have learned just how essential it is to fully and effectively integrate new hires into the organization for their own satisfaction and success—and ours. Indeed, we cannot expect to achieve the Quadruple Aim without investing in the kind of transparent and intentional orientation process that defines expectations, aligns cultural values, mitigates costly and stressful operational misunderstandings, and communicates to physicians that, not only do they belong, but their sense of belonging is our priority. While we have yet to understand the impact of this program on the fourth aim of the Quadruple Aim, we are hopeful that the benefits will be far-reaching.

It is our ultimate hope that programs like this: (1) give physicians the confidence needed to create impactful patient-centered experiences; (2) enable physicians to become more cost-effective and efficient in care delivery; (3) allow physicians to understand the populations they are serving and access tools available to mitigate health disparities and other barriers; and (4) improve the collective experience of every member of the care team, practice leadership, and clinician-patient partnership.

Corresponding author: J. Nwando Olayiwola, MD, MPH, FAAFP, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 2231 N High St, Ste 250, Columbus, OH 43210; nwando.olayiwola@osumc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Keywords: physician onboarding; Quadruple Aim; leadership; clinician satisfaction; care team satisfaction.

From The Ohio State University College of Medicine Department of Family and Community Medicine, Columbus, OH (Candy Magaña, Jná Báez, Christine Junk, Drs. Ahmad, Conroy, and Olayiwola); The Ohio State University College of Medicine Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation (Candy Magaña, Jná Báez, and Dr. Olayiwola); and The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center (Christine Harsh, Erica Esposito).

Much has been discussed about the growing crisis of professional dissatisfaction among physicians, with increasing efforts being made to incorporate physician wellness into health system strategies that move from the Triple to the Quadruple Aim.1 For many years, our health care system has been focused on improving the health of populations, optimizing the patient experience, and reducing the cost of care (Triple Aim). The inclusion of the fourth aim, improving the experience of the teams that deliver care, has become paramount in achieving the other aims.

An area often overlooked in this focus on wellness, however, is the importance of the earliest days of employment to shape and predict long-term career contentment. This is a missed opportunity, as data suggest that organizations with standardized onboarding programs boast a 62% increased productivity rate and a 50% greater retention rate among new hires.2,3 Moreover, a study by the International Institute for Management Development found that businesses lose an estimated $37 billion annually because employees do not fully understand their jobs.4 The report ties losses to “actions taken by employees who have misunderstood or misinterpreted company policies, business processes, job function, or a combination of the three.” Additionally, onboarding programs that focus strictly on technical or functional orientation tasks miss important opportunities for culture integration during the onboarding process.5 It is therefore imperative to look to effective models of employee onboarding to develop systems that position physicians and practices for success.

Challenges With Traditional Physician Onboarding

In recent years, the Department of Family and Community Medicine at The Ohio State University College of Medicine has experienced rapid organizational change. Like many primary care systems nationwide responding to disruption in health care and changing demands on the clinical workforce, the department has hired new leadership, revised strategic priorities, and witnessed an influx of faculty and staff. It has also planned an expansion of ambulatory services that will more than double the clinical workforce over the next 3 years. While an exciting time, there has been a growing need to align strategy, culture, and human capital during these changes.

As we entered this phase of transformation, we recognized that our highly individualized, ad hoc orientation system presented shortcomings. During the act of revamping our physician recruitment process, stakeholder workgroup members specifically noted that improvement efforts were needed regarding new physician orientation, as no consistent structures were previously in place. New physician orientation had been a major gap for years, resulting in dissatisfaction in the first few months of physician practice, early physician turnover, and staff frustration. For physicians, we continued to learn about their frustration and unanswered questions regarding expectations, norms, structures, and processes.

Many new hires were left with a kind of “trial by fire” entry into their roles. On the first day of clinic, a new physician would most likely need to simultaneously see patients, learn the nuances of the electronic health record (EHR), figure out where the break room was located, and quickly learn population health issues for the patients they were serving. Opportunities to meet key clinic site leadership would be at random, and new physicians might not have the opportunity to meet leadership or staff until months into their tenure; this did not allow for a sense of belonging or understanding of the many resources available to them. We learned that the quality of these ad hoc orientations also varied based on the experience and priorities of each practice’s clinic and administrative leaders, who themselves felt ill-equipped to provide a consistent, robust, and confidence-building experience. In addition, practice site management was rarely given advance time to prepare for the arrival of new physicians, which resulted in physicians perceiving practices to be unwelcoming and disorganized. Their first days were often spent with patients in clinic with no structured orientation and without understanding workflows or having systems practice knowledge.

Institutionally, the interview process satisfied some transfer of knowledge, but we were unclear of what was being consistently shared and understood in the multiple ambulatory locations where our physicians enter practice. More importantly, we knew we were missing a critical opportunity to use orientation to imbue other values of diversity and inclusion, health equity, and operational excellence into the workforce. Based on anecdotal insights from employees and our own review of successful onboarding approaches from other industries, we also knew a more structured welcoming process would predict greater long-term career satisfaction for physicians and create a foundation for providing optimal care for patients when clinical encounters began.

Reengineering Physician Onboarding

In 2019, our department developed a multipronged approach to physician onboarding, which is already paying dividends in easing acculturation and fostering team cohesion. The department tapped its Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation (PCIT) to direct this effort, based on its expertise in practice transformation, clinical transformation and adaptations, and workflow efficiency through process and quality improvement. The PCIT team provides support to the department and the entire health system focused on technology and innovation, health equity, and health care efficiency.6 They applied many of the tools used in the Clinical Transformation in Technology approach to lead this initiative.7

The PCIT team began identifying key stakeholders (department, clinical and ambulatory leadership, clinicians and clinical staff, community partners, human resources, and resident physicians), and then engaging those individuals in dialogue surrounding orientation needs. During scheduled in-person and virtual work sessions, stakeholders were asked to provide input on pain points for new physicians and clinic leadership and were then empowered to create an onboarding program. Applying health care quality improvement techniques, we leveraged workflow mapping, current and future state planning, and goal setting, led by the skilled process improvement and clinical transformation specialists. We coordinated a multidisciplinary process improvement team that included clinic administrators, medical directors, human resources, administrative staff, ambulatory and resident leadership, clinical leadership, and recruitment liaisons. This diverse group of leadership and staff was brought together to address these critical identified gaps and weaknesses in new physician onboarding.

Through a series of learning sessions, the workgroup provided input that was used to form an itemized physician onboarding schedule, which was then leveraged to develop Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles, collecting feedback in real time. Some issues that seem small can cause major distress for new physicians. For example, in our inaugural orientation implementation, a physician provided feedback that they wanted to obtain information on setting up their work email on their personal devices and was having considerable trouble figuring out how to do so. This particular topic was not initially included in the first iteration of the Department’s orientation program. We rapidly sought out different ways to embed that into the onboarding experience. The first PDSA involved integrating the university information technology team (IT) into the process but was not successful because it required extra work for the new physician and reliance on the IT schedule. The next attempt was to have IT train a department staff member, but again, this still required that the physician find time to connect with that staff member. Finally, we decided to obtain a useful tip sheet that clearly outlined the process and could be included in orientation materials. This gave the new physicians control over how and when they would work on this issue. Based on these learnings, this was incorporated as a standing agenda item and resource for incoming physicians.

Essential Elements of Effective Onboarding

The new physician onboarding program consists of 5 key elements: (1) 2-week acclimation period; (2) peer learning and connection; (3) training before beginning patient care; (4) standardization, transparency, and accountability in all processes; (5) ongoing feedback for continued program improvement with individual support (Figure).

The program begins with a 2-week period of intentional investment in individual success, during which time no patients are scheduled. In week 1, we work with new hires to set expectations for performance, understand departmental norms, and introduce culture. Physicians meet formally and informally with department and institutional leadership, as well as attend team meetings and trainings that include a range of administrative and compliance requirements, such as quality standards and expectations, compliance, billing and coding specific to family medicine, EHR management, and institutionally mandated orientations. We are also adding implicit bias and antiracism training during this period, which are essential to creating a culture of unity and belonging.

During week 2, we focus on clinic-level orientation, assigning new hires an orientation buddy and a department sponsor, such as a physician lead or medical director. Physicians spend time with leadership at their clinic as they nurture relationships important for mentorship, sponsorship, and peer support. They also meet care team members, including front desk associates, medical assistants, behavioral health clinicians, nutritionists, social workers, pharmacists, and other key colleagues and care team members. This introduces the physician to the clinical environment and physical space as well as acclimates the physician to workflows and feedback loops for regular interaction.

When physicians ultimately begin patient care, they begin with an expected productivity rate of 50%, followed by an expected productivity rate of 75%, and then an expected productivity rate of 100%. This steady increase occurs over 3 to 4 weeks depending on the physician’s comfort level. They are also provided monthly reports on work relative value unit performance so that they can track and adapt practice patterns as necessary.More details on the program can be found in Appendix 1.

Takeaways From the Implementation of the New Program

Give time for new physicians to focus on acclimating to the role and environment.

The initial 2-week period of transition—without direct patient care—ensures that physicians feel comfortable in their new ecosystem. This also supports personal transitions, as many new hires are managing relocation and acclimating themselves and their families to new settings. Even residents from our training program who returned as attending physicians found this flexibility and slow reentry essential. This also gives the clinic time to orient to an additional provider, nurture them into the team culture, and develop relationships with the care team.

Cultivate spaces for shared learning, problem-solving, and peer connection.

Orientation is delivered primarily through group learning sessions with cohorts of new physicians, thus developing spaces for networking, fostering psychological safety, encouraging personal and professional rapport, emphasizing interactive learning, and reinforcing scheduling blocks at the departmental level. New hires also participate in peer shadowing to develop clinical competencies and are assigned a workplace buddy to foster a sense of belonging and create opportunities for additional knowledge sharing and cross-training.

Strengthen physician knowledge base, confidence, and comfort in the workplace before beginning direct patient care.

Without fluency in the workflows, culture, and operations of a practice, the urgency to have physicians begin clinical care can result in frustration for the physician, patients, and clinical and administrative staff. Therefore, we complete essential training prior to seeing any patients. This includes clinical workflows, referral processes, use of alternate modalities of care (eg, telehealth, eConsults), billing protocols, population health training, patient resources, office resources, and other essential daily processes and tools. This creates efficiency in administrative management, increased productivity, and better understanding of resources available for patients’ medical, social, and behavioral needs when patient care begins.

Embrace standardization, transparency, and accountability in as many processes as possible.

Standardized knowledge-sharing and checklists are mandated at every step of the orientation process, requiring sign off from the physician lead, practice manager, and new physicians upon completion. This offers all parties the opportunity to play a role in the delivery of and accountability for skills transfer and empowers new hires to press pause if they feel unsure about any domain in the training. It is also essential in guaranteeing that all physicians—regardless of which ambulatory location they practice in—receive consistent information and expectations. A sample checklist can be found in Appendix 2.

Commit to collecting and acting on feedback for continued program improvement and individual support.

As physicians complete the program, it is necessary to create structures to measure and enhance its impact, as well as evaluate how physicians are faring following the program. Each physician completes surveys at the end of the orientation program, attends a 90-day post-program check-in with the department chair, and receives follow-up trainings on advanced topics as they become more deeply embedded in the organization.

Lessons Learned

Feedback from surveys and 90-day check-ins with leadership and physicians reflect a high degree of clarity on job roles and duties, a sense of team camaraderie, easier system navigation, and a strong sense of support. We do recognize that sustaining change takes time and our study is limited by data demonstrating the impact of these efforts. We look forward to sharing more robust data from surveys and qualitative interviews with physicians, clinical leadership, and staff in the future. Our team will conduct interviews at 90-day and 180-day checkpoints with new physicians who have gone through this program, followed by a check-in after 1 year. Additionally, new physicians as well as key stakeholders, such as physician leads, practice managers, and members of the recruitment team, have started to participate in short surveys. These are designed to better understand their experiences, what worked well, what can be improved, and the overall satisfaction of the physician and other members of the extended care team.

What follows are some comments made by the initial group of physicians that went through this program and participated in follow-up interviews:

“I really feel like part of a bigger team.”

“I knew exactly what do to when I walked into the exam room on clinic Day 1.”

“It was great to make deep connections during the early process of joining.”

“Having a buddy to direct questions and ideas to is amazing and empowering.”

“Even though the orientation was long, I felt that I learned so much that I would not have otherwise.”

“Thank you for not letting me crash and burn!”

“Great culture! I love understanding our values of health equity, diversity, and inclusion.”

In the months since our endeavor began, we have learned just how essential it is to fully and effectively integrate new hires into the organization for their own satisfaction and success—and ours. Indeed, we cannot expect to achieve the Quadruple Aim without investing in the kind of transparent and intentional orientation process that defines expectations, aligns cultural values, mitigates costly and stressful operational misunderstandings, and communicates to physicians that, not only do they belong, but their sense of belonging is our priority. While we have yet to understand the impact of this program on the fourth aim of the Quadruple Aim, we are hopeful that the benefits will be far-reaching.

It is our ultimate hope that programs like this: (1) give physicians the confidence needed to create impactful patient-centered experiences; (2) enable physicians to become more cost-effective and efficient in care delivery; (3) allow physicians to understand the populations they are serving and access tools available to mitigate health disparities and other barriers; and (4) improve the collective experience of every member of the care team, practice leadership, and clinician-patient partnership.

Corresponding author: J. Nwando Olayiwola, MD, MPH, FAAFP, The Ohio State University College of Medicine, Department of Family and Community Medicine, 2231 N High St, Ste 250, Columbus, OH 43210; nwando.olayiwola@osumc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

Keywords: physician onboarding; Quadruple Aim; leadership; clinician satisfaction; care team satisfaction.

1. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6): 573-576.

2. Maurer R. Onboarding key to retaining, engaging talent. Society for Human Resource Management. April 16, 2015. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/onboarding-key-retaining-engaging-talent.aspx

3. Boston AG. New hire onboarding standardization and automation powers productivity gains. GlobeNewswire. March 8, 2011. Accessed January 8, 2021. http://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2011/03/08/994239/0/en/New-Hire-Onboarding-Standardization-and-Automation-Powers-Productivity-Gains.html

4. $37 billion – US and UK business count the cost of employee misunderstanding. HR.com – Maximizing Human Potential. June 18, 2008. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.hr.com/en/communities/staffing_and_recruitment/37-billion---us-and-uk-businesses-count-the-cost-o_fhnduq4d.html

5. Employers risk driving new hires away with poor onboarding. Society for Human Resource Management. February 23, 2018. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/employers-new-hires-poor-onboarding.aspx

6. Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation. The Ohio State University College of Medicine. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/departments/family-medicine/pcit

7. Olayiwola, J.N. and Magaña, C. Clinical transformation in technology: a fresh change management approach for primary care. Harvard Health Policy Review. February 2, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2021. http://www.hhpronline.org/articles/2019/2/2/clinical-transformation-in-technology-a-fresh-change-management-approach-for-primary-care

1. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6): 573-576.

2. Maurer R. Onboarding key to retaining, engaging talent. Society for Human Resource Management. April 16, 2015. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/onboarding-key-retaining-engaging-talent.aspx

3. Boston AG. New hire onboarding standardization and automation powers productivity gains. GlobeNewswire. March 8, 2011. Accessed January 8, 2021. http://www.globenewswire.com/news-release/2011/03/08/994239/0/en/New-Hire-Onboarding-Standardization-and-Automation-Powers-Productivity-Gains.html

4. $37 billion – US and UK business count the cost of employee misunderstanding. HR.com – Maximizing Human Potential. June 18, 2008. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.hr.com/en/communities/staffing_and_recruitment/37-billion---us-and-uk-businesses-count-the-cost-o_fhnduq4d.html

5. Employers risk driving new hires away with poor onboarding. Society for Human Resource Management. February 23, 2018. Accessed March 10, 2021. https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/hr-topics/talent-acquisition/pages/employers-new-hires-poor-onboarding.aspx

6. Center for Primary Care Innovation and Transformation. The Ohio State University College of Medicine. Accessed January 8, 2021. https://wexnermedical.osu.edu/departments/family-medicine/pcit

7. Olayiwola, J.N. and Magaña, C. Clinical transformation in technology: a fresh change management approach for primary care. Harvard Health Policy Review. February 2, 2019. Accessed March 10, 2021. http://www.hhpronline.org/articles/2019/2/2/clinical-transformation-in-technology-a-fresh-change-management-approach-for-primary-care