User login

Association of Nausea and Length of Stay with Carbohydrate Loading Prior to Total Joint Arthroplasty

From Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY (Dr. Blum), and NYU Winthrop Medical Center,

Abstract

- Background: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal, standardized approach to the surgical patient that incorporates evidenced-based interventions designed to achieve rapid recovery after surgery by minimizing the patient’s stress response. One aspect of ERAS, carbohydrate loading, has been shown in multiple randomized controlled trials to result in postoperative benefits in patients undergoing colorectal surgery, but there appears to be insufficient data to make definitive recommendations for or against carbohydrate loading in joint replacement patients.

- Objective: To evaluate postoperative nausea and length of stay (LOS) after a preoperative carbohydrate loading protocol was initiated for patients undergoing total joint replacement.

- Design: Retrospective chart review.

- Setting and participants: 100 patients who underwent either total knee or hip arthroplasty at Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY, in the past 4 years and either had (n = 50) or had not received preoperative carbohydrate supplements (n = 50).

- Methods: Using the total joint database, the medical record was reviewed for the patient’s demographics, LOS, documentation of postoperative nausea, and number of doses of antiemetic medication given to the patient.

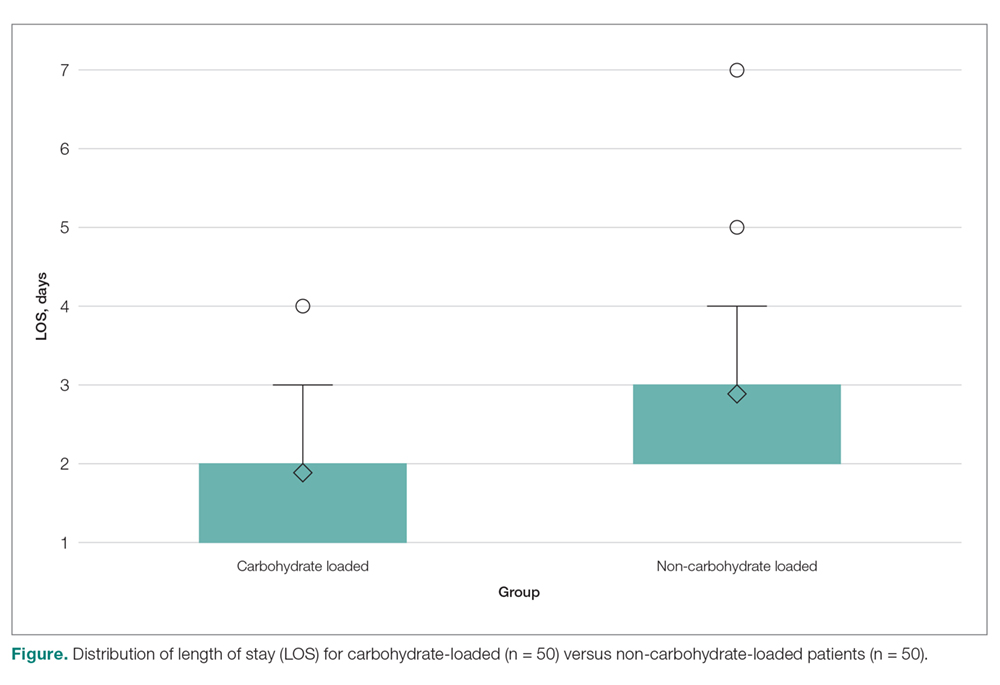

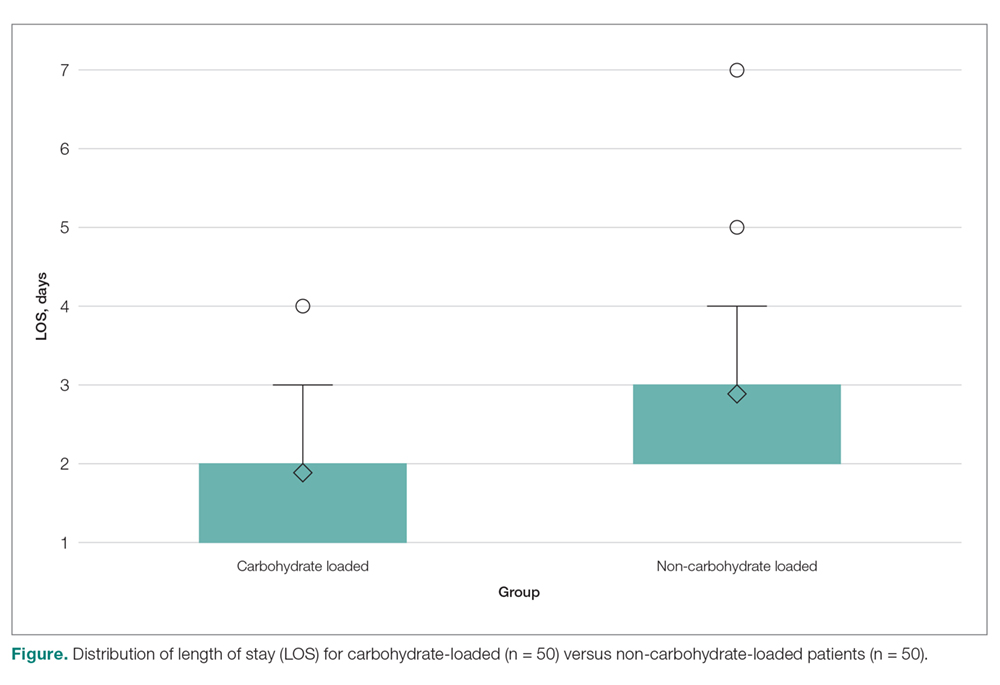

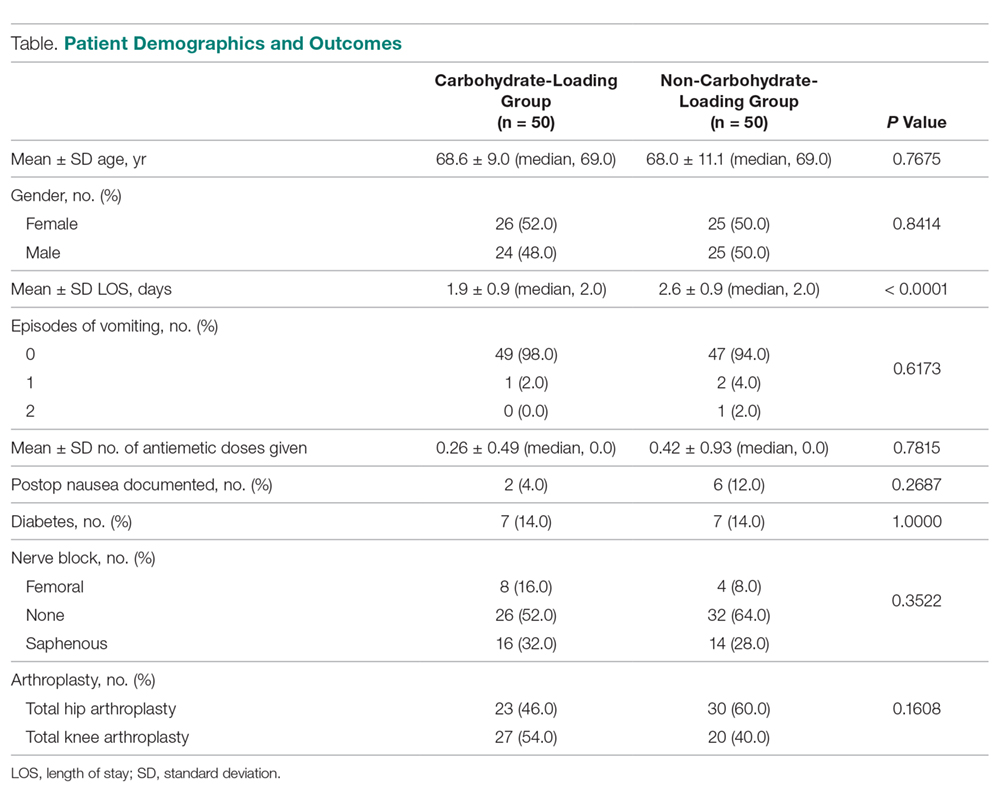

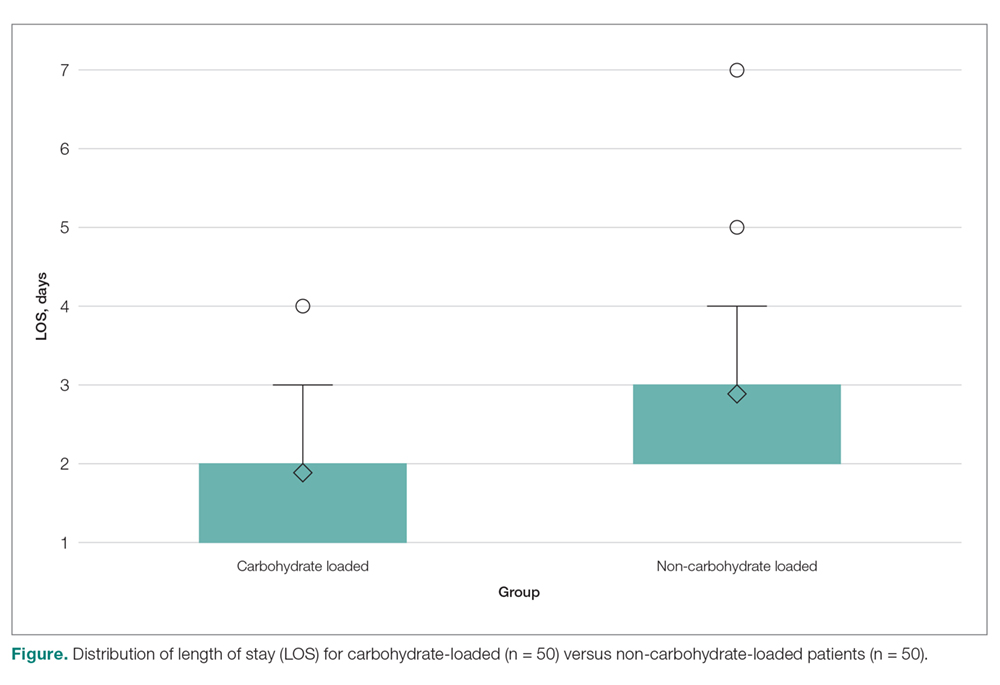

- Results: The mean LOS for the carbohydrate-loading group and non-carbohydrate group was 1.9 days and 2.6 days. respectively, a difference of 0.70 days (P < 0.0001). The carbohydrate-loaded group received a total of 13 doses of antiemetic medications and the non-carbohydrate group received 21 doses. The average number of antiemetic doses given to a patient postoperatively was 0.26 for the carbohydrate-loaded group and 0.42 for the non-carbohydrate-loaded group. The difference was 0.16 doses (P < 0.7815).

- Conclusion: The implementation of carbohydrate loading decreased LOS for joint replacement patients by approximately 1 day. Additionally, there was a trend towards decreased antiemetic use and fewer documented cases of postoperative nausea after carbohydrate loading.

Keywords: carbohydrate loading, ERAS, joint arthroplasty, length of stay, nausea.

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal, standardized approach to the surgical patient that incorporates evidenced-based interventions designed to achieve rapid recovery after surgery by minimizing the patient’s stress response.1-4 The ERAS protocols have been shown to reduce complications, decrease length of stay (LOS), and improve patient outcomes.3-7 The program was originally designed to facilitate recovery after colorectal operative procedures by maintaining preoperative organ function and reducing the postoperative stress response. This was done through a coordinated program of preoperative counseling, optimizing nutritional status, standardizing analgesic regimens, and early mobilization.3

The principles of an ERAS program with standardized pre- and postoperative protocols appear ideally suited for the total joint arthroplasty patient.1,3-5 Prior studies have demonstrated ERAS to be effective in facilitating decreased LOS, with no apparent increase in readmission rates or complications for both colorectal and joint arthroplasty patients.1-7 The protocols have also been shown to be cost-effective, with decreased incidence of postoperative complications, including thromboembolic disease and infections.3,4,6

An important tenet of ERAS protocols is optimizing the nutritional status of the patient prior to surgery.6 This includes avoidance of preoperative fasting in conjunction with carbohydrate loading. ERAS protocols instruct the patient to ingest a carbohydrate-rich beverage 2 hours prior to surgery. The concept of allowing a patient to eat prior to surgery is based on the preference for the patient to present for surgery in an anabolic rather than a catabolic state.2,3,11 Patients in an anabolic state undergo less postoperative protein and nitrogen losses, which appears to facilitate wound healing.2,6,11

There have been multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrating the postoperative benefits of carbohydrate loading prior to colorectal surgery.2,6

Another potential benefit of preoperative carbohydrate loading is a decrease in postoperative nausea.1,5,12-14 A decrease in nausea in theory would allow for earlier mobilization with physical therapy and potentially a shorter LOS. Hence, the goal of this study was to examine the impact of preoperative carbohydrate loading on postoperative nausea directly, as well as on LOS, at a single institution in the setting of an ERAS protocol.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 100 patients who underwent total hip or total knee replacement between 2014 and 2018 at NYU Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY. Fifty patients had received preoperative carbohydrate supplements and 50 patients had not. The remainder of the total joint protocol was identical for the 2 groups.

Protocol

All patients attended preoperative educational classes. For patients receiving carbohydrate loading, written and oral instructions were given for the patient to drink Ensure Clear followed by 8 ounces of water before going to bed the night before surgery. They were also instructed to drink the Ensure Pre-Surgery Drink 2 hours prior to their operative procedure. Patients with diabetes were instructed to drink the Ensure Glucerna Clear drink the night before surgery. No carbohydrate drink was given on the day of surgery until a finger-stick glucose level was performed upon arrival at the hospital. Spinal anesthesia was utilized in all patients, with adductor canal block supplementation for patients undergoing total knee replacement. Orders were written to have physical therapy evaluate the patients in the PACU to facilitate ambulation. Pre- and postoperative pain protocols were identical for the 2 groups.

Data Collection

A chart review was performed using the patients’ medical record numbers from the joint replacement database at our institution. Exemption was obtained for the project from our institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and median for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were calculated separately by group. The 2 groups were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as deemed appropriate, for categorical variables, the 2-sample t-test for age, and the Mann-Whitney test for LOS and number of antiemetic doses given. A result was considered statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level of significance. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

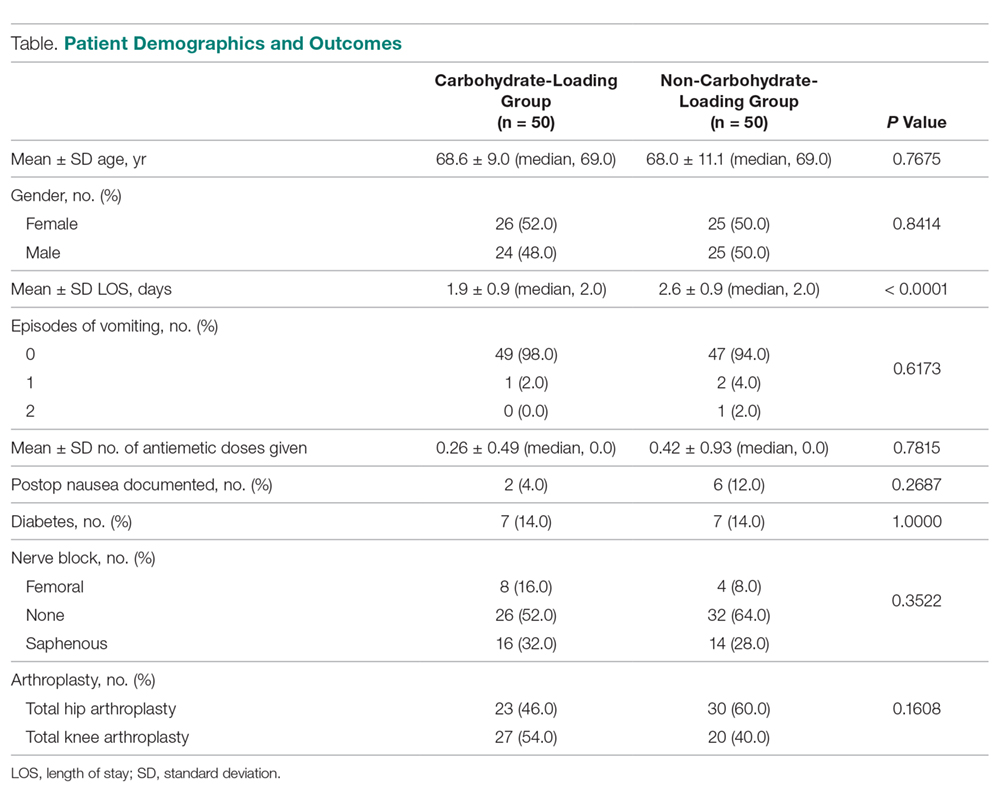

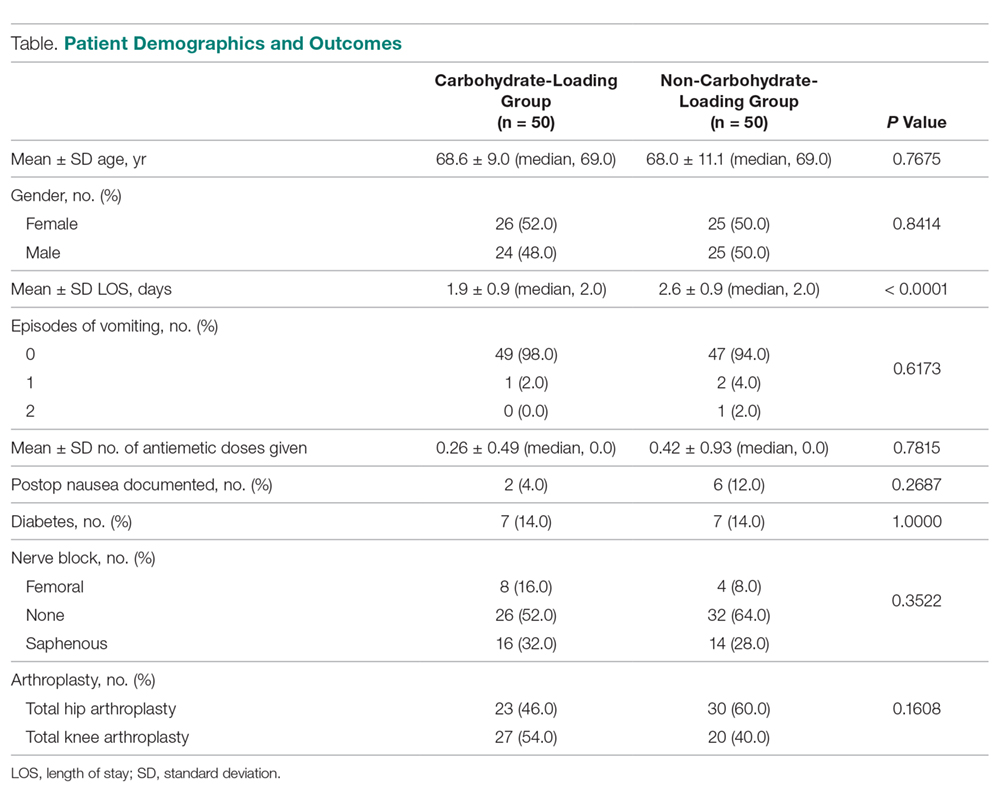

The carbohydrate-loading group (n = 50) and the non-carbohydrate-loading group (n = 50) were comparable for age, gender, type of arthroplasty, episodes of vomiting, diabetes, and nerve block (Table).

Discussion

In this study we explored whether carbohydrate loading prior to total joint replacement influenced postoperative nausea and LOS in a single institution. The 2 groups appeared similar in terms of demographics as well as the types of surgical procedures performed. After initiation of the carbohydrate-loading protocol, LOS decreased by approximately 1 day. There was also a trend toward decreased usage of antiemetics in the carbohydrate-loaded group, although the final values were not statistically significant. There were also fewer documented cases of postoperative nausea in the carbohydrate-loaded group.

The failure to find a statistical difference in postoperative antiemetic usage between carbohydrate-loaded and non-carbohydrate-loaded patients may be due to incomplete documentation (ie, not all patients who were nauseous having their symptoms documented in the chart). Due to the small number of antiemetic doses given to each patient, we may have lacked the necessary numbers to visualize the difference between the groups. We were unable to perform a post-hoc power calculation with our current data. Additionally, the decrease seen in LOS may not have been due solely to carbohydrate loading, since the data were collected over multiple years during implementation of the ERAS protocol. There is a possibility that the ERAS protocol, which is multimodal, was better implemented as time progressed, adding a confounding variable to our data. Despite these limitations, however, we were able to demonstrate a decreased LOS for patients who underwent total joint replacement with the initiation of a preoperative carbohydrate-loading ERAS protocol. Furthermore, there was a trend toward decreased documented postoperative nausea and decreased antiemetic use in the group that avoided fasting and received carbohydrate supplements.

This decrease in LOS by almost 1 day is consistent with multiple prior studies that demonstrated a similar decrease when implementing an ERAS protocol.3-5,7 The trend towards lower antiemetic use and less postoperative nausea in the carbohydrate-loading ERAS protocol gives merit to further research on this topic, with the goal of finding an optimal preoperative practice that allows patients to experience rapid mobilization, minimal postoperative nausea, and faster recovery overall.

Conclusion

Corresponding author: Christopher L. Blum, MD, Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY; blumc18@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Proudfoot S, Bennett B, Duff S, Palmer J. Implementation and effects of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for hip and knee replacements and fractured neck of femur in New Zealand orthopaedic services. N Z Med J. 2017;130:77-90.

2. Geltzeiler CB, Rotramel A, Wilson C, et al. Prospective study of colorectal enhanced recovery after surgery in a community hospital. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:955-961.

3. Soffin EM, YaDeau JT. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a review of the evidence. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(suppl 3):iii62-iii72.

4. Stowers MD, Manuopangai L, Hill AG, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in elective hip and knee arthroplasty reduces length of hospital stay. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86:475-479.

5. Gwynne-Jones DP, Martin G, Crane C. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for hip and knee replacements. Orthop Nurs. 2017;36:203-210.

6. Semerjian A, Milbar N, Kates M, et al. Hospital charges and length of stay following radical cystectomy in the enhanced recovery after surgery era. Urology. 2018;111:86-91.

7. Stambough JB, Nunley RM, Curry MC, et al. Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:521-526.

8. Ljungqvist O, Soreide E. Preoperative fasting. Br J Surg. 2003;90:400-406.

9. Riis J, Lomholt B, Haxholdt O, et al. Immediate and long-term mental recovery from general versus epidural anesthesia in elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1983;27:44-49.

10. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630-641.

11. Svanfeldt M, Thorell A, Hausel J, Soop M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment on postoperative whole-body protein and glucose kinetics. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1342-1350.

12. Halaszynski TM, Juda R, Silverman DG. Optimizing postoperative outcomes with efficient preoperative assessment and management. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4 suppl):S76-S86.

13. Aronsson A, Al-Ani NA, Brismar K, Hedstrom M. A carbohydrate-rich drink shortly before surgery affected IGF-I bioavailability after a total hip replacement. A double-blind placebo controlled study on 29 patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21:97-101.

14. Bilku DK, Dennison AR, Hall TC, Metcalfe MS, Garcea G. Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:15-22.

From Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY (Dr. Blum), and NYU Winthrop Medical Center,

Abstract

- Background: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal, standardized approach to the surgical patient that incorporates evidenced-based interventions designed to achieve rapid recovery after surgery by minimizing the patient’s stress response. One aspect of ERAS, carbohydrate loading, has been shown in multiple randomized controlled trials to result in postoperative benefits in patients undergoing colorectal surgery, but there appears to be insufficient data to make definitive recommendations for or against carbohydrate loading in joint replacement patients.

- Objective: To evaluate postoperative nausea and length of stay (LOS) after a preoperative carbohydrate loading protocol was initiated for patients undergoing total joint replacement.

- Design: Retrospective chart review.

- Setting and participants: 100 patients who underwent either total knee or hip arthroplasty at Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY, in the past 4 years and either had (n = 50) or had not received preoperative carbohydrate supplements (n = 50).

- Methods: Using the total joint database, the medical record was reviewed for the patient’s demographics, LOS, documentation of postoperative nausea, and number of doses of antiemetic medication given to the patient.

- Results: The mean LOS for the carbohydrate-loading group and non-carbohydrate group was 1.9 days and 2.6 days. respectively, a difference of 0.70 days (P < 0.0001). The carbohydrate-loaded group received a total of 13 doses of antiemetic medications and the non-carbohydrate group received 21 doses. The average number of antiemetic doses given to a patient postoperatively was 0.26 for the carbohydrate-loaded group and 0.42 for the non-carbohydrate-loaded group. The difference was 0.16 doses (P < 0.7815).

- Conclusion: The implementation of carbohydrate loading decreased LOS for joint replacement patients by approximately 1 day. Additionally, there was a trend towards decreased antiemetic use and fewer documented cases of postoperative nausea after carbohydrate loading.

Keywords: carbohydrate loading, ERAS, joint arthroplasty, length of stay, nausea.

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal, standardized approach to the surgical patient that incorporates evidenced-based interventions designed to achieve rapid recovery after surgery by minimizing the patient’s stress response.1-4 The ERAS protocols have been shown to reduce complications, decrease length of stay (LOS), and improve patient outcomes.3-7 The program was originally designed to facilitate recovery after colorectal operative procedures by maintaining preoperative organ function and reducing the postoperative stress response. This was done through a coordinated program of preoperative counseling, optimizing nutritional status, standardizing analgesic regimens, and early mobilization.3

The principles of an ERAS program with standardized pre- and postoperative protocols appear ideally suited for the total joint arthroplasty patient.1,3-5 Prior studies have demonstrated ERAS to be effective in facilitating decreased LOS, with no apparent increase in readmission rates or complications for both colorectal and joint arthroplasty patients.1-7 The protocols have also been shown to be cost-effective, with decreased incidence of postoperative complications, including thromboembolic disease and infections.3,4,6

An important tenet of ERAS protocols is optimizing the nutritional status of the patient prior to surgery.6 This includes avoidance of preoperative fasting in conjunction with carbohydrate loading. ERAS protocols instruct the patient to ingest a carbohydrate-rich beverage 2 hours prior to surgery. The concept of allowing a patient to eat prior to surgery is based on the preference for the patient to present for surgery in an anabolic rather than a catabolic state.2,3,11 Patients in an anabolic state undergo less postoperative protein and nitrogen losses, which appears to facilitate wound healing.2,6,11

There have been multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrating the postoperative benefits of carbohydrate loading prior to colorectal surgery.2,6

Another potential benefit of preoperative carbohydrate loading is a decrease in postoperative nausea.1,5,12-14 A decrease in nausea in theory would allow for earlier mobilization with physical therapy and potentially a shorter LOS. Hence, the goal of this study was to examine the impact of preoperative carbohydrate loading on postoperative nausea directly, as well as on LOS, at a single institution in the setting of an ERAS protocol.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 100 patients who underwent total hip or total knee replacement between 2014 and 2018 at NYU Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY. Fifty patients had received preoperative carbohydrate supplements and 50 patients had not. The remainder of the total joint protocol was identical for the 2 groups.

Protocol

All patients attended preoperative educational classes. For patients receiving carbohydrate loading, written and oral instructions were given for the patient to drink Ensure Clear followed by 8 ounces of water before going to bed the night before surgery. They were also instructed to drink the Ensure Pre-Surgery Drink 2 hours prior to their operative procedure. Patients with diabetes were instructed to drink the Ensure Glucerna Clear drink the night before surgery. No carbohydrate drink was given on the day of surgery until a finger-stick glucose level was performed upon arrival at the hospital. Spinal anesthesia was utilized in all patients, with adductor canal block supplementation for patients undergoing total knee replacement. Orders were written to have physical therapy evaluate the patients in the PACU to facilitate ambulation. Pre- and postoperative pain protocols were identical for the 2 groups.

Data Collection

A chart review was performed using the patients’ medical record numbers from the joint replacement database at our institution. Exemption was obtained for the project from our institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and median for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were calculated separately by group. The 2 groups were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as deemed appropriate, for categorical variables, the 2-sample t-test for age, and the Mann-Whitney test for LOS and number of antiemetic doses given. A result was considered statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level of significance. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The carbohydrate-loading group (n = 50) and the non-carbohydrate-loading group (n = 50) were comparable for age, gender, type of arthroplasty, episodes of vomiting, diabetes, and nerve block (Table).

Discussion

In this study we explored whether carbohydrate loading prior to total joint replacement influenced postoperative nausea and LOS in a single institution. The 2 groups appeared similar in terms of demographics as well as the types of surgical procedures performed. After initiation of the carbohydrate-loading protocol, LOS decreased by approximately 1 day. There was also a trend toward decreased usage of antiemetics in the carbohydrate-loaded group, although the final values were not statistically significant. There were also fewer documented cases of postoperative nausea in the carbohydrate-loaded group.

The failure to find a statistical difference in postoperative antiemetic usage between carbohydrate-loaded and non-carbohydrate-loaded patients may be due to incomplete documentation (ie, not all patients who were nauseous having their symptoms documented in the chart). Due to the small number of antiemetic doses given to each patient, we may have lacked the necessary numbers to visualize the difference between the groups. We were unable to perform a post-hoc power calculation with our current data. Additionally, the decrease seen in LOS may not have been due solely to carbohydrate loading, since the data were collected over multiple years during implementation of the ERAS protocol. There is a possibility that the ERAS protocol, which is multimodal, was better implemented as time progressed, adding a confounding variable to our data. Despite these limitations, however, we were able to demonstrate a decreased LOS for patients who underwent total joint replacement with the initiation of a preoperative carbohydrate-loading ERAS protocol. Furthermore, there was a trend toward decreased documented postoperative nausea and decreased antiemetic use in the group that avoided fasting and received carbohydrate supplements.

This decrease in LOS by almost 1 day is consistent with multiple prior studies that demonstrated a similar decrease when implementing an ERAS protocol.3-5,7 The trend towards lower antiemetic use and less postoperative nausea in the carbohydrate-loading ERAS protocol gives merit to further research on this topic, with the goal of finding an optimal preoperative practice that allows patients to experience rapid mobilization, minimal postoperative nausea, and faster recovery overall.

Conclusion

Corresponding author: Christopher L. Blum, MD, Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY; blumc18@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY (Dr. Blum), and NYU Winthrop Medical Center,

Abstract

- Background: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal, standardized approach to the surgical patient that incorporates evidenced-based interventions designed to achieve rapid recovery after surgery by minimizing the patient’s stress response. One aspect of ERAS, carbohydrate loading, has been shown in multiple randomized controlled trials to result in postoperative benefits in patients undergoing colorectal surgery, but there appears to be insufficient data to make definitive recommendations for or against carbohydrate loading in joint replacement patients.

- Objective: To evaluate postoperative nausea and length of stay (LOS) after a preoperative carbohydrate loading protocol was initiated for patients undergoing total joint replacement.

- Design: Retrospective chart review.

- Setting and participants: 100 patients who underwent either total knee or hip arthroplasty at Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY, in the past 4 years and either had (n = 50) or had not received preoperative carbohydrate supplements (n = 50).

- Methods: Using the total joint database, the medical record was reviewed for the patient’s demographics, LOS, documentation of postoperative nausea, and number of doses of antiemetic medication given to the patient.

- Results: The mean LOS for the carbohydrate-loading group and non-carbohydrate group was 1.9 days and 2.6 days. respectively, a difference of 0.70 days (P < 0.0001). The carbohydrate-loaded group received a total of 13 doses of antiemetic medications and the non-carbohydrate group received 21 doses. The average number of antiemetic doses given to a patient postoperatively was 0.26 for the carbohydrate-loaded group and 0.42 for the non-carbohydrate-loaded group. The difference was 0.16 doses (P < 0.7815).

- Conclusion: The implementation of carbohydrate loading decreased LOS for joint replacement patients by approximately 1 day. Additionally, there was a trend towards decreased antiemetic use and fewer documented cases of postoperative nausea after carbohydrate loading.

Keywords: carbohydrate loading, ERAS, joint arthroplasty, length of stay, nausea.

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) is a multimodal, standardized approach to the surgical patient that incorporates evidenced-based interventions designed to achieve rapid recovery after surgery by minimizing the patient’s stress response.1-4 The ERAS protocols have been shown to reduce complications, decrease length of stay (LOS), and improve patient outcomes.3-7 The program was originally designed to facilitate recovery after colorectal operative procedures by maintaining preoperative organ function and reducing the postoperative stress response. This was done through a coordinated program of preoperative counseling, optimizing nutritional status, standardizing analgesic regimens, and early mobilization.3

The principles of an ERAS program with standardized pre- and postoperative protocols appear ideally suited for the total joint arthroplasty patient.1,3-5 Prior studies have demonstrated ERAS to be effective in facilitating decreased LOS, with no apparent increase in readmission rates or complications for both colorectal and joint arthroplasty patients.1-7 The protocols have also been shown to be cost-effective, with decreased incidence of postoperative complications, including thromboembolic disease and infections.3,4,6

An important tenet of ERAS protocols is optimizing the nutritional status of the patient prior to surgery.6 This includes avoidance of preoperative fasting in conjunction with carbohydrate loading. ERAS protocols instruct the patient to ingest a carbohydrate-rich beverage 2 hours prior to surgery. The concept of allowing a patient to eat prior to surgery is based on the preference for the patient to present for surgery in an anabolic rather than a catabolic state.2,3,11 Patients in an anabolic state undergo less postoperative protein and nitrogen losses, which appears to facilitate wound healing.2,6,11

There have been multiple randomized controlled trials demonstrating the postoperative benefits of carbohydrate loading prior to colorectal surgery.2,6

Another potential benefit of preoperative carbohydrate loading is a decrease in postoperative nausea.1,5,12-14 A decrease in nausea in theory would allow for earlier mobilization with physical therapy and potentially a shorter LOS. Hence, the goal of this study was to examine the impact of preoperative carbohydrate loading on postoperative nausea directly, as well as on LOS, at a single institution in the setting of an ERAS protocol.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 100 patients who underwent total hip or total knee replacement between 2014 and 2018 at NYU Winthrop University Hospital, Mineola, NY. Fifty patients had received preoperative carbohydrate supplements and 50 patients had not. The remainder of the total joint protocol was identical for the 2 groups.

Protocol

All patients attended preoperative educational classes. For patients receiving carbohydrate loading, written and oral instructions were given for the patient to drink Ensure Clear followed by 8 ounces of water before going to bed the night before surgery. They were also instructed to drink the Ensure Pre-Surgery Drink 2 hours prior to their operative procedure. Patients with diabetes were instructed to drink the Ensure Glucerna Clear drink the night before surgery. No carbohydrate drink was given on the day of surgery until a finger-stick glucose level was performed upon arrival at the hospital. Spinal anesthesia was utilized in all patients, with adductor canal block supplementation for patients undergoing total knee replacement. Orders were written to have physical therapy evaluate the patients in the PACU to facilitate ambulation. Pre- and postoperative pain protocols were identical for the 2 groups.

Data Collection

A chart review was performed using the patients’ medical record numbers from the joint replacement database at our institution. Exemption was obtained for the project from our institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and median for continuous variables; frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were calculated separately by group. The 2 groups were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, as deemed appropriate, for categorical variables, the 2-sample t-test for age, and the Mann-Whitney test for LOS and number of antiemetic doses given. A result was considered statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level of significance. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The carbohydrate-loading group (n = 50) and the non-carbohydrate-loading group (n = 50) were comparable for age, gender, type of arthroplasty, episodes of vomiting, diabetes, and nerve block (Table).

Discussion

In this study we explored whether carbohydrate loading prior to total joint replacement influenced postoperative nausea and LOS in a single institution. The 2 groups appeared similar in terms of demographics as well as the types of surgical procedures performed. After initiation of the carbohydrate-loading protocol, LOS decreased by approximately 1 day. There was also a trend toward decreased usage of antiemetics in the carbohydrate-loaded group, although the final values were not statistically significant. There were also fewer documented cases of postoperative nausea in the carbohydrate-loaded group.

The failure to find a statistical difference in postoperative antiemetic usage between carbohydrate-loaded and non-carbohydrate-loaded patients may be due to incomplete documentation (ie, not all patients who were nauseous having their symptoms documented in the chart). Due to the small number of antiemetic doses given to each patient, we may have lacked the necessary numbers to visualize the difference between the groups. We were unable to perform a post-hoc power calculation with our current data. Additionally, the decrease seen in LOS may not have been due solely to carbohydrate loading, since the data were collected over multiple years during implementation of the ERAS protocol. There is a possibility that the ERAS protocol, which is multimodal, was better implemented as time progressed, adding a confounding variable to our data. Despite these limitations, however, we were able to demonstrate a decreased LOS for patients who underwent total joint replacement with the initiation of a preoperative carbohydrate-loading ERAS protocol. Furthermore, there was a trend toward decreased documented postoperative nausea and decreased antiemetic use in the group that avoided fasting and received carbohydrate supplements.

This decrease in LOS by almost 1 day is consistent with multiple prior studies that demonstrated a similar decrease when implementing an ERAS protocol.3-5,7 The trend towards lower antiemetic use and less postoperative nausea in the carbohydrate-loading ERAS protocol gives merit to further research on this topic, with the goal of finding an optimal preoperative practice that allows patients to experience rapid mobilization, minimal postoperative nausea, and faster recovery overall.

Conclusion

Corresponding author: Christopher L. Blum, MD, Stony Brook Medical Center, Stony Brook, NY; blumc18@gmail.com.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Proudfoot S, Bennett B, Duff S, Palmer J. Implementation and effects of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for hip and knee replacements and fractured neck of femur in New Zealand orthopaedic services. N Z Med J. 2017;130:77-90.

2. Geltzeiler CB, Rotramel A, Wilson C, et al. Prospective study of colorectal enhanced recovery after surgery in a community hospital. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:955-961.

3. Soffin EM, YaDeau JT. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a review of the evidence. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(suppl 3):iii62-iii72.

4. Stowers MD, Manuopangai L, Hill AG, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in elective hip and knee arthroplasty reduces length of hospital stay. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86:475-479.

5. Gwynne-Jones DP, Martin G, Crane C. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for hip and knee replacements. Orthop Nurs. 2017;36:203-210.

6. Semerjian A, Milbar N, Kates M, et al. Hospital charges and length of stay following radical cystectomy in the enhanced recovery after surgery era. Urology. 2018;111:86-91.

7. Stambough JB, Nunley RM, Curry MC, et al. Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:521-526.

8. Ljungqvist O, Soreide E. Preoperative fasting. Br J Surg. 2003;90:400-406.

9. Riis J, Lomholt B, Haxholdt O, et al. Immediate and long-term mental recovery from general versus epidural anesthesia in elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1983;27:44-49.

10. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630-641.

11. Svanfeldt M, Thorell A, Hausel J, Soop M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment on postoperative whole-body protein and glucose kinetics. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1342-1350.

12. Halaszynski TM, Juda R, Silverman DG. Optimizing postoperative outcomes with efficient preoperative assessment and management. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4 suppl):S76-S86.

13. Aronsson A, Al-Ani NA, Brismar K, Hedstrom M. A carbohydrate-rich drink shortly before surgery affected IGF-I bioavailability after a total hip replacement. A double-blind placebo controlled study on 29 patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21:97-101.

14. Bilku DK, Dennison AR, Hall TC, Metcalfe MS, Garcea G. Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:15-22.

1. Proudfoot S, Bennett B, Duff S, Palmer J. Implementation and effects of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for hip and knee replacements and fractured neck of femur in New Zealand orthopaedic services. N Z Med J. 2017;130:77-90.

2. Geltzeiler CB, Rotramel A, Wilson C, et al. Prospective study of colorectal enhanced recovery after surgery in a community hospital. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:955-961.

3. Soffin EM, YaDeau JT. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a review of the evidence. Br J Anaesth. 2016;117(suppl 3):iii62-iii72.

4. Stowers MD, Manuopangai L, Hill AG, et al. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery in elective hip and knee arthroplasty reduces length of hospital stay. ANZ J Surg. 2016;86:475-479.

5. Gwynne-Jones DP, Martin G, Crane C. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery for hip and knee replacements. Orthop Nurs. 2017;36:203-210.

6. Semerjian A, Milbar N, Kates M, et al. Hospital charges and length of stay following radical cystectomy in the enhanced recovery after surgery era. Urology. 2018;111:86-91.

7. Stambough JB, Nunley RM, Curry MC, et al. Rapid recovery protocols for primary total hip arthroplasty can safely reduce length of stay without increasing readmissions. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:521-526.

8. Ljungqvist O, Soreide E. Preoperative fasting. Br J Surg. 2003;90:400-406.

9. Riis J, Lomholt B, Haxholdt O, et al. Immediate and long-term mental recovery from general versus epidural anesthesia in elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1983;27:44-49.

10. Kehlet H, Wilmore DW. Multimodal strategies to improve surgical outcome. Am J Surg. 2002;183:630-641.

11. Svanfeldt M, Thorell A, Hausel J, Soop M, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effect of preoperative oral carbohydrate treatment on postoperative whole-body protein and glucose kinetics. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1342-1350.

12. Halaszynski TM, Juda R, Silverman DG. Optimizing postoperative outcomes with efficient preoperative assessment and management. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(4 suppl):S76-S86.

13. Aronsson A, Al-Ani NA, Brismar K, Hedstrom M. A carbohydrate-rich drink shortly before surgery affected IGF-I bioavailability after a total hip replacement. A double-blind placebo controlled study on 29 patients. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2009;21:97-101.

14. Bilku DK, Dennison AR, Hall TC, Metcalfe MS, Garcea G. Role of preoperative carbohydrate loading: a systematic review. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:15-22.

Implementing ACOVE quality indicators as an intervention checklist to improve care for hospitalized older adults

In 2014, the United States spent $3 trillion on healthcare; hospitalization consumed 32% of these expenditures.1 Today, Medicare patients account for over 50% of hospital days and over 30% of all hospital discharges in the United States.2 Despite this staggering financial burden, hospitalization of older adults often results in poor patient outcomes.3-6 The exponential growth of the hospitalist movement, from 350 hospitalists nationwide in 1995 to over 44,000 in 2014, has become the key strategy for providing care to hospitalized geriatric patients.7-10 Most of these hospitalists have not received geriatric training.11-15

There is growing evidence that a geriatric approach, emphasizing multidisciplinary management of the complex needs of older patients, leads to improved outcomes. Geriatric Evaluation and Management Units (GEMUs), such as Acute Care for Elderly (ACE) models, have demonstrated significant decreases in functional decline, institutionalization, and death in randomized controlled trials.16,17 Multidisciplinary, nonunit based efforts, such as the mobile acute care of elderly (MACE), proactive consultation models (Sennour/Counsell), and the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), have demonstrated success in preventing adverse events and decreasing length of stay (LOS).17-20

However, these models have not been systematically implemented due to challenges in generalizability and replicability in diverse settings. To address this concern, an alternative approach must be developed to widely “generalize” geriatric expertise throughout hospitals, regardless of their location, size, and resources. This initiative will require systematic integration of evidence-based decision support tools for the standardization of clinical management in hospitalized older adults.21

The 1998 Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) project developed a standardized tool to measure and evaluate the quality of care by using a comprehensive set of quality indicators (QIs) to improve the care of “vulnerable elders” (VEs) at a high risk for functional and cognitive decline and death.22-24 The latest systematic review concludes that, although many studies have used ACOVE as an assessment tool of quality, there has been a dearth of studies investigating the ACOVE QIs as an intervention to improve patient care.25

Our study investigated the role of ACOVE as an intervention by using the QIs as a standardized checklist in the acute care setting. We selected the 4 most commonly encountered QIs in the hospital setting, namely venous thrombosis prophylaxis (VTE), indwelling bladder catheter, mobilization, and delirium evaluation, in order to test the feasibility and impact of systematically implementing these ACOVE QIs as a therapeutic intervention for all hospitalized older adults.

METHODS

This study (IRB #13-644B) was conducted using a prospective intervention with a nonequivalent control group design comprised of retrospective chart data from May 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015. Process and outcome variables were extracted from electronic medical records ([EMR], Sunrise Clinical Manager [SCM]) of 2,396 patients, with 530 patients in the intervention unit and 1,866 on the control units, at a large academic tertiary center operating in the greater New York metropolitan area. Our study investigated the role of ACOVE as an intervention to improve patient care by using selected QIs as a standardized checklist tool in the acute care setting. Of the original 30 hospital-specific QIs, our study focused on the care of older adults admitted to the medicine service.26 We selected commonly encountered QIs, with the objective of testing the feasibility and impact of implementing the ACOVE QIs as an intervention to improve care of hospitalized older adults. This intervention consisted of applying the checklist tool, constructed with 4 selected ACOVE QIs and administered daily during interdisciplinary rounds, namely: 2 general “medical” indicators, VTE prophylaxis and indwelling bladder catheters, and 2 “geriatric”-focused indicators, mobilization and delirium evaluation.

Subject matter experts (hospitalists, geriatricians, researchers, administrators, and nurses) reviewed the ACOVE QIs and agreed upon the adaptation of the QIs from a quality measure assessment into a feasible and acceptable intervention checklist tool (Table 1). The checklist was reviewed during daily interdisciplinary rounds for all patients 75 years and older. While ACOVE defined vulnerable elders by using the Vulnerable Elder Screen (VES), we wanted to apply this intervention more broadly to all hospitalized older adults who are most at risk for poor outcomes.27 Patients admitted to the intensive care unit, inpatient psychiatry, inpatient leukemia/lymphoma, and surgical services were excluded.

Daily interdisciplinary rounds are held on every one of the five 40-bed medical units; they last approximately 1 hour, and consist of a lead hospitalist, nurse manager, nurse practitioners, case managers, and the nursing staff. During interdisciplinary rounds, nurses present the case to the team members who then discuss the care plan. These 5 medical units did not differ in terms of patient characteristics or staffing patterns; the intervention unit was chosen simply for logistical reasons, in that the principal investigator (PI) had been assigned to this unit prior to study start-up.

Prior to the intervention, LS held an education session for staff on the intervention unit staff (who participated on interdisciplinary rounds) to explain the concept of the ACOVE QI initiative and describe the four QIs selected for the study. Three subsequent educational sessions were held during the first week of the intervention, with new incoming staff receiving a brief individual educational session. The staff demonstrated significant knowledge improvement after session completion (pre/post mean score 70.6% vs 90.0%; P < .0001).

The Clinical Information System for the Health System EMR, The Eclipsys SCM, has alerts with different levels of severity from “soft” (user must acknowledge a recommendation) to “hard” (requires an action in order to proceed).

To measure compliance of the quality indicators, we collected the following variables:

QI 1: VTE prophylaxis

Through SCM, we collected type of VTE prophylaxis ordered (pharmacologic and/or mechanical) as well as start and stop dates for all agents. International normalized ratio levels were checked for patients receiving warfarin. Days of compliance were calculated.

QI 2: Indwelling Bladder Catheters

SCM data were collected on catheter entry and discontinuation dates, the presence of an indication, and order renewal for bladder catheter at least every 3 days.

QI 3: Mobilization

Ambulation status prior to admission was extracted from nursing documentation completed on admission to the medical ward. Patients documented as bedfast were categorized as nonambulatory prior to admission. Nursing documentation of activity level and amount of feet ambulated per nursing shift were collected. In addition, hospital day of physical therapy (PT) order and hospital days with PT performed were charted. Compliance with QI 3 in patients documented as ambulatory prior to hospital admission was recorded as present if there was a PT order within 48 hours of admission.

QI 4: Delirium Evaluation

During daily rounds, the hospitalist (PI) questioned nurses about delirium evaluation, using the first feature of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) as well as the “single question in delirium,” namely, “Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline?” and “Do you think [name of patient] has been more confused lately?”28,29 Because EMR does not contain a specified field for delirium screening and documentation, and patients are not routinely included in rounds, documentation with QI 4 was recorded using the “key words” method as described in the work by Puelle et al.30 To extract SCM key words, nursing documentation of the “cognitive/perceptual/neurological exam” section of the EMR on admission and on all subsequent documentation (once per shift) was retrieved to identify acute changes in mental status (eg, “altered mental status, delirium/delirious, alert and oriented X 3, confused/confusion, disoriented, lethargy/lethargic”).30 In addition, nurses were asked to activate an SCM parameter, “Acute Confusion” SCM parameter, in the nursing documentation section, which includes potential risk factors for confusion.

In addition to QI compliance, we collected LOS, discharge disposition, and 30-day readmission data.

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) for binary clustered (ie, hierarchical) data were used to estimate compliance rates (ie, nurse adherence) for each group (intervention group or control group) in the postintervention period, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. GLMM was used to account for the hierarchical structure of the data: nursing units within a hospital. In order to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index, we extracted past medical history from the EMR.31

Subjects (N = 2,396) were included in the comparison of the intervention group vs control group for each of the following 4 ACOVE QI compliance measures: DVT, mobilization, bladder catheter, and delirium.

RESULTS

Of the 2,396 patient admissions, 530 were in the intervention unit and 1,866 were in the control unit. In the intervention group, the average age was 84.65 years, 75.58% were white and 47.21% were married. There was no difference in patient demographics between groups (Table 2).

QI 1: VTE Prophylaxis

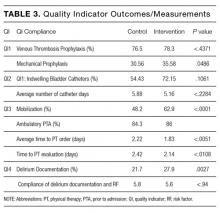

Compliance with VTE prophylaxis was met in 78.3% of the intervention subjects and 76.5% of the controls (P < .4371) (Table 3). Of note, the rate of VTE prophylaxis was 57% in the intervention vs 39% in the control group (P < .0056), in the 554 patients for whom compliance was not met. Mechanical prophylaxis was used in 35.6% of intervention subjects vs 30.6 in the control (P = .048). Patients who received no form of prophylaxis were 0.5% in the intervention and 3% in the control (P = .027).

QI 2: Indwelling Bladder Catheters

Out of 2,396 subjects, 406 had an indwelling bladder catheter (16.9%). Compliance with the catheter was met in 72.2% of the intervention group vs 54.4% in the control group (P = .1061). An indication for indwelling bladder catheters was documented in 100% of the subjects. The average number of catheter days was 5.16 in the intervention vs 5.88 in the control (P < .2284). There was statistical significance in catheter compliance in the longer stay (>15 days) subjects, decreasing to 23.32% in the control group while staying constant in the intervention group 71.5% (P = .0006).

QI 3: Mobilization

Of the 2,396 patients, 1,991 (83.1%) were reported as ambulatory prior to admission. In the intervention vs control group, 74 (14%) vs 297 (15.7%), respectively, were nonambulatory. Overall compliance with Q3 was 62.9% in the intervention vs 48.2% in the control (P < .0001). More specifically, the average time to PT order in the intervention group was 1.83 days vs 2.22 days in the control group (P <

QI 4: Delirium Evaluation

In terms of nursing documentation indicating the presence of an acute confusional state, the intervention group had 148 out of 530 nursing notes (27.9%) vs 405 out of 1,866 in the control group (21.7%; P = .0027). However, utilization of the “acute confusion” parameter with documentation of a risk factor did not differ between the groups (5.8% in the intervention group vs 5.6% in the control group, P < .94).

LOS, Discharge Disposition, and 30-Day Readmissions

LOS did not differ between intervention and control groups (6.37 days vs 6.27 days, respectively), with a median of 5 days (P = .877). Discharge disposition in the 2 groups included the following: home/home with services (71.32% vs 68.7%), skilled nursing facility/assisted living/long-term care (24.34 versus 25.83), inpatient hospice/home hospice (2.64 vs 2.25), and expired (1.13 vs 1.77; P < .3282). In addition, 30-day readmissions did not differ (21% vs 20%, respectively, P = .41).

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to explore an evidence-based, standardized approach to improve the care of hospitalized older adults. This approach leverages existing automated EMR alert functions with an additional level of decision support for VEs, integrated into daily multidisciplinary rounds. The use of a daily checklist-based tool offers a cost-effective and practical pathway to distribute the burden of compliance responsibility amongst team members.

As we anticipated and similar to study findings in hospitalized medicine, geriatric trauma, and primary care, compliance with general care QIs was better than geriatric-focused QIs.27,32 Wenger et al33 demonstrated significant improvements with screening for falls and incontinence; however, screening for cognitive impairment did not improve in the outpatient setting by imbedding ACOVE QIs into routine physician practice.

Increased compliance with VTE prophylaxis and indwelling bladder catheters may be explained by national financial incentives for widespread implementation of EMR alert systems. Conversely, mobilization, delirium assessment, and management in hospitalized older adults don’t benefit from similar incentives.

VTE Prophylaxis

The American College of Chest Physicians (ACCP) supports the use of VTE prophylaxis, especially in hospitalized older adults with decreased mobility.34 While greater adoption of EMR has already increased adherence, our intervention resulted in an even higher rate of compliance with the use of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis.35 In the future, validated scores for risk of thrombosis and bleeding may be integrated into our QI-based checklist.

Indwelling Bladder Catheters

The potential harms of catheters have been described for over 50 years, yet remain frequently used.36,37 Previous studies have shown success in decreasing catheter days with computer-based and multidisciplinary protocols.36-39

Our health system’s EMR has built-in “soft” and “hard” alerts for indwelling bladder catheters, so we did not expect intervention-associated changes in compliance.

Mobilization

Hospitalization in older adults frequently results in functional decline.4,5,40 In response, the mobilization QI recommends an ambulation plan within 48 hours for those patients who were ambulatory prior to admission; it does not specifically define the components of the plan.26 There are several multicomponent interventions that have demonstrated improvement in functional decline, yet they require skilled providers.41,42 Our intervention implemented specific ambulation plan components: daily ambulation and documentation reminders and early PT evaluation.

While functional status measures have existed for decades, most are primarily geared to assess community-residing individuals and not designed to measure changes in function during hospitalization.43,44 Furthermore, performance-based hospital measures are difficult to integrate into the daily nursing workflow as they are time consuming.45,46 In practice, nurses routinely use free text to document functional status in the hospital setting, rendering comparative analysis problematic. Yet, we demonstrated that nurses were more engaged in reporting mobilization (increased documentation of ambulation distance and a decrease in time to PT). Future research should focus on the development of a standardized tool, integrated into the EMR, to accurately measure function in the acute care setting.

Delirium Evaluation

Delirium evaluation remains one of the most difficult clinical challenges for healthcare providers in hospitalized individuals, and our study reiterated these concerns. Previous research has consistently demonstrated that the diagnosis of delirium is missed by up to 75% of clinicians.47,48 Indeed, our study, which exclusively examined nursing documentation of the delirium evaluation QI, found that both groups showed strikingly low compliance rates. This may have been due to the fact that we only evaluated nursing documentation of suspected or definite diagnosis of delirium and a documented attempt to attribute the altered mental state to a potential etiology.31 By utilizing the concept of “key words,” as developed by Puelle et al.30, we were able to demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in nursing delirium documentation in the intervention group. This result should be interpreted with caution, as this approach is not validated. Furthermore, our operational definition of delirium compliance (ie, nurse documentation of delirium, requiring the launching of a separate parameter) may have been simply too cumbersome to readily integrate into the daily workflow. Future research should study the efficacy of a sensitive EMR-integrated screening tool that facilitates recognition, by all team members, of acute changes in cognition.

Although a number of QI improved for the intervention group, acute care utilization measures such as LOS, discharge disposition, and 30-day readmissions did not differ between groups. It may well be that improving quality for this very frail, vulnerable population may simply not result in decreased utilization. Our ability to further decrease LOS and readmission rates may be limited due to restriction of range in this complex patient population (eg, median LOS value of 5 days).

Limitations

Although our study had a large sample size, data were only collected from a single-center and thus require further exploration in different settings to ensure generalizability. In addition, QI observance was based on the medical record, which was problematic for some indicators, notably delirium identification. While prior literature highlights the difficulty in identifying delirium, especially during clinical practice without specialized training, our compliance was strikingly low.47 While validated measures such as CAM may have been included as part of the assessment, there is currently no EMR documentation of such measures and therefore, these data could not be obtained.

CONCLUSION

In summary, our study demonstrates the successful integration of the established ACOVE QIs as an intervention, rather than as an assessment method, for improving care of hospitalized older patients. By utilizing a checklist-based tool at the bedside allows the multidisciplinary team to implement evidence-based practices with the ultimate goal of standardizing care, not only for VEs, but potentially for other high-risk populations with multimorbidity.49 This innovative approach provides a much-needed direction to healthcare providers in the ever increasing stressful conditions of today’s acute care environment and for the ultimate benefit and safety of our older patients.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. This study was supported by New York State Empire Clinical Research Investigators Program (ECRIP). The sponsor had no role in the conception, study design, data collection, data analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation, or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

1. National Center for Health Statistics (US). Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics (US); 2016. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK367640/. Accessed November 2, 2016.

2. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Hospital Stays in the United States, 2012: Statistical Brief #180. In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2006. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK259100/. Accessed November 2, 2016.

3. Jencks SF, Cuerdon T, Burwen DR, et al. Quality of medical care delivered to medicare beneficiaries: A profile at state and national levels. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1670-1676. PubMed

4. Covinsky KE, Pierluissi E, Johnston C. Hospitalization-associated disability: “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure.” JAMA. 2011;306(16):1782-1793. PubMed

5. Creditor MC. Hazards of Hospitalization of the Elderly. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(3):219-223. PubMed

6. Graf C. Functional decline in hospitalized older adults. Am J Nurs. 2006;106(1):58-67, NaN-68. PubMed

7. Wachter RM, Goldman L. The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(7):514-517. PubMed

8. Lindenauer PK, Pantilat SZ, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Hospitalists and the practice of inpatient medicine: results of a survey of the National Association of Inpatient Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(4 Pt 2):343-349. PubMed

9. Wachter RM. The hospitalist movement 5 years later. JAMA. 2002;287(4):487. PubMed

10. Shank B. 2016: Celebrating 20 years of hospital medicine and looking toward a bright future. Hosp Natl Assoc Inpatient Physicians. 2016. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/hospitalist/article/121925/2016-celebrating-20-years-hospital-medicine-and-looking-toward-bright. Accessed June 2, 2017.

11. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Washington, DC.: National Academies Press; 2008. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12089. Accessed November 2, 2016.

12. Boult C, Counsell SR, Leipzig RM, Berenson RA. The urgency of preparing primary care physicians to care for older people with chronic illnesses. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2010;29(5):811-818. PubMed

13. Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Thomas DC, Ho ML, Brewer DE, Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs. Are internal medicine residency programs adequately preparing physicians to care for the baby boomers? A national survey from the Association of Directors of Geriatric Academic Programs Status of Geriatrics Workforce Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(10):1603-1609. PubMed

14. Tanner CE, Eckstrom E, Desai SS, Joseph CL, Ririe MR, Bowen JL. Uncovering frustrations: A qualitative needs assessment of academic general internists as geriatric care providers and teachers. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):51-55. PubMed

15. Warshaw GA, Bragg EJ, Brewer DE, Meganathan K, Ho M. The development of academic geriatric medicine: progress toward preparing the nation’s physicians to care for an aging population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(12):2075-2082. PubMed

16. Fox MT, Sidani S, Persaud M, et al. Acute care for elders components of acute geriatric unit care: Systematic descriptive review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):939-946. PubMed

17. Palmer RM, Landefeld CS, Kresevic D, Kowal J. A medical unit for the acute care of the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42(5):545-552.

18. Hung WW, Ross JS, Farber J, Siu AL. Evaluation of the Mobile Acute Care of the Elderly (MACE) service. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(11):990-996. PubMed

19. Sennour Y, Counsell SR, Jones J, Weiner M. Development and implementation of a proactive geriatrics consultation model in collaboration with hospitalists. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(11):2139-2145. PubMed

20. Ellis G, Whitehead MA, O’Neill D, Langhorne P, Robinson D. Comprehensive geriatric assessment for older adults admitted to hospital. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD006211. PubMed

21. Mattison MLP, Catic A, Davis RB, et al. A standardized, bundled approach to providing geriatric-focused acute care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(5):936-942. doi:10.1111/jgs.12780. PubMed

22. Wenger NS, Shekelle PG. Assessing care of vulnerable elders: ACOVE project overview. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(8 Pt 2):642-646. PubMed

23. Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle P, ACOVE Investigators. Introduction to the assessing care of vulnerable elders-3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55 Suppl 2:S247-S252. PubMed

24. Reuben DB, Roth C, Kamberg C, Wenger NS. Restructuring primary care practices to manage geriatric syndromes: the ACOVE-2 intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(12):1787-1793. PubMed

25. Askari M, Wierenga PC, Eslami S, Medlock S, De Rooij SE, Abu-Hanna A. Studies pertaining to the ACOVE quality criteria: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(1):80-87. PubMed

26. Arora VM, McGory ML, Fung CH. Quality indicators for hospitalization and surgery in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55 Suppl 2:S347-S358. PubMed

27. Arora VM, Johnson M, Olson J, et al. Using assessing care of vulnerable elders quality indicators to measure quality of hospital care for vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(11):1705-1711. PubMed

28. Sands M, Dantoc B, Hartshorn A, Ryan C, Lujic S. Single Question in Delirium (SQiD): testing its efficacy against psychiatrist interview, the Confusion Assessment Method and the Memorial Delirium Assessment Scale. Palliat Med. 2010;24(6):561-565. PubMed

29. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948. PubMed

30. Puelle MR, Kosar CM, Xu G, et al. The language of delirium: Keywords for identifying delirium from medical records. J Gerontol Nurs. 2015;41(8):34-42. PubMed

31. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. PubMed

32. Boult C, Boult L, Morishita L, Smith SL, Kane RL. Outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(3):296-302.33. Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle PG, et al. A practice-based intervention to improve primary care for falls, urinary incontinence, and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(3):547-555. PubMed

34. Geerts WH. Prevention of Venous Thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest J. 2008;133(6_suppl):381S.

35. Rosenman M, Liu X, Phatak H, et al. Pharmacological prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism among hospitalized patients with acute medical illness: An electronic medical records study. Am J Ther. 2016;23(2):e328-e335. PubMed

36. Ghanem A, Artime C, Moser M, Caceres L, Basconcillo A. Holy moley! Take out that foley! Measuring compliance with a nurse driven protocol for foley catheter removal to decrease utilization. Am J Infect Control. 2015;43(6):S51.

37. Cornia PB, Amory JK, Fraser S, Saint S, Lipsky BA. Computer-based order entry decreases duration of indwelling urinary catheterization in hospitalized patients. Am J Med. 2003;114(5):404-407. PubMed

38. Huang W-C, Wann S-R, Lin S-L, et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections in intensive care units can be reduced by prompting physicians to remove unnecessary catheters. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(11):974-978. PubMed

39. Topal J, Conklin S, Camp K, Morris V, Balcezak T, Herbert P. Prevention of nosocomial catheter-associated urinary tract infections through computerized feedback to physicians and a nurse-directed protocol. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(3):121-126. PubMed

40. Zisberg A, Shadmi E, Gur-Yaish N, Tonkikh O, Sinoff G. Hospital-associated functional decline: the role of hospitalization processes beyond individual risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(1):55-62. PubMed

41. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Baker DI, Leo-Summers L, Cooney LM. The Hospital Elder Life Program: a model of care to prevent cognitive and functional decline in older hospitalized patients. Hospital Elder Life Program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(12):1697-1706. PubMed

42. Hoyer EH, Friedman M, Lavezza A, et al. Promoting mobility and reducing length of stay in hospitalized general medicine patients: A quality-improvement project. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(5):341-347. PubMed

43. Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the barthel index. Md State Med J. 1965;14:61-65. PubMed

44. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. the index of adl: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185:914-919. PubMed

45. Tinetti ME. Performance-oriented assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(2):119-126. PubMed

46. Smith R. Validation and Reliability of the Elderly Mobility Scale. Physiotherapy. 1994;80(11):744-747.

47. Inouye SK, Foreman MD, Mion LC, Katz KH, Cooney LM. Nurses’ recognition of delirium and its symptoms: comparison of nurse and researcher ratings. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(20):2467-2473. PubMed

48. Gustafson Y, Brännström B, Norberg A, Bucht G, Winblad B. Underdiagnosis and poor documentation of acute confusional states in elderly hip fracture patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(8):760-765. PubMed

49. Brenner SK, Kaushal R, Grinspan Z, et al. Effects of health information technology on patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(5):1016-1036. PubMed

In 2014, the United States spent $3 trillion on healthcare; hospitalization consumed 32% of these expenditures.1 Today, Medicare patients account for over 50% of hospital days and over 30% of all hospital discharges in the United States.2 Despite this staggering financial burden, hospitalization of older adults often results in poor patient outcomes.3-6 The exponential growth of the hospitalist movement, from 350 hospitalists nationwide in 1995 to over 44,000 in 2014, has become the key strategy for providing care to hospitalized geriatric patients.7-10 Most of these hospitalists have not received geriatric training.11-15

There is growing evidence that a geriatric approach, emphasizing multidisciplinary management of the complex needs of older patients, leads to improved outcomes. Geriatric Evaluation and Management Units (GEMUs), such as Acute Care for Elderly (ACE) models, have demonstrated significant decreases in functional decline, institutionalization, and death in randomized controlled trials.16,17 Multidisciplinary, nonunit based efforts, such as the mobile acute care of elderly (MACE), proactive consultation models (Sennour/Counsell), and the Hospital Elder Life Program (HELP), have demonstrated success in preventing adverse events and decreasing length of stay (LOS).17-20

However, these models have not been systematically implemented due to challenges in generalizability and replicability in diverse settings. To address this concern, an alternative approach must be developed to widely “generalize” geriatric expertise throughout hospitals, regardless of their location, size, and resources. This initiative will require systematic integration of evidence-based decision support tools for the standardization of clinical management in hospitalized older adults.21

The 1998 Assessing Care of Vulnerable Elders (ACOVE) project developed a standardized tool to measure and evaluate the quality of care by using a comprehensive set of quality indicators (QIs) to improve the care of “vulnerable elders” (VEs) at a high risk for functional and cognitive decline and death.22-24 The latest systematic review concludes that, although many studies have used ACOVE as an assessment tool of quality, there has been a dearth of studies investigating the ACOVE QIs as an intervention to improve patient care.25

Our study investigated the role of ACOVE as an intervention by using the QIs as a standardized checklist in the acute care setting. We selected the 4 most commonly encountered QIs in the hospital setting, namely venous thrombosis prophylaxis (VTE), indwelling bladder catheter, mobilization, and delirium evaluation, in order to test the feasibility and impact of systematically implementing these ACOVE QIs as a therapeutic intervention for all hospitalized older adults.

METHODS

This study (IRB #13-644B) was conducted using a prospective intervention with a nonequivalent control group design comprised of retrospective chart data from May 1, 2014, to June 30, 2015. Process and outcome variables were extracted from electronic medical records ([EMR], Sunrise Clinical Manager [SCM]) of 2,396 patients, with 530 patients in the intervention unit and 1,866 on the control units, at a large academic tertiary center operating in the greater New York metropolitan area. Our study investigated the role of ACOVE as an intervention to improve patient care by using selected QIs as a standardized checklist tool in the acute care setting. Of the original 30 hospital-specific QIs, our study focused on the care of older adults admitted to the medicine service.26 We selected commonly encountered QIs, with the objective of testing the feasibility and impact of implementing the ACOVE QIs as an intervention to improve care of hospitalized older adults. This intervention consisted of applying the checklist tool, constructed with 4 selected ACOVE QIs and administered daily during interdisciplinary rounds, namely: 2 general “medical” indicators, VTE prophylaxis and indwelling bladder catheters, and 2 “geriatric”-focused indicators, mobilization and delirium evaluation.

Subject matter experts (hospitalists, geriatricians, researchers, administrators, and nurses) reviewed the ACOVE QIs and agreed upon the adaptation of the QIs from a quality measure assessment into a feasible and acceptable intervention checklist tool (Table 1). The checklist was reviewed during daily interdisciplinary rounds for all patients 75 years and older. While ACOVE defined vulnerable elders by using the Vulnerable Elder Screen (VES), we wanted to apply this intervention more broadly to all hospitalized older adults who are most at risk for poor outcomes.27 Patients admitted to the intensive care unit, inpatient psychiatry, inpatient leukemia/lymphoma, and surgical services were excluded.

Daily interdisciplinary rounds are held on every one of the five 40-bed medical units; they last approximately 1 hour, and consist of a lead hospitalist, nurse manager, nurse practitioners, case managers, and the nursing staff. During interdisciplinary rounds, nurses present the case to the team members who then discuss the care plan. These 5 medical units did not differ in terms of patient characteristics or staffing patterns; the intervention unit was chosen simply for logistical reasons, in that the principal investigator (PI) had been assigned to this unit prior to study start-up.

Prior to the intervention, LS held an education session for staff on the intervention unit staff (who participated on interdisciplinary rounds) to explain the concept of the ACOVE QI initiative and describe the four QIs selected for the study. Three subsequent educational sessions were held during the first week of the intervention, with new incoming staff receiving a brief individual educational session. The staff demonstrated significant knowledge improvement after session completion (pre/post mean score 70.6% vs 90.0%; P < .0001).

The Clinical Information System for the Health System EMR, The Eclipsys SCM, has alerts with different levels of severity from “soft” (user must acknowledge a recommendation) to “hard” (requires an action in order to proceed).

To measure compliance of the quality indicators, we collected the following variables:

QI 1: VTE prophylaxis

Through SCM, we collected type of VTE prophylaxis ordered (pharmacologic and/or mechanical) as well as start and stop dates for all agents. International normalized ratio levels were checked for patients receiving warfarin. Days of compliance were calculated.

QI 2: Indwelling Bladder Catheters

SCM data were collected on catheter entry and discontinuation dates, the presence of an indication, and order renewal for bladder catheter at least every 3 days.

QI 3: Mobilization

Ambulation status prior to admission was extracted from nursing documentation completed on admission to the medical ward. Patients documented as bedfast were categorized as nonambulatory prior to admission. Nursing documentation of activity level and amount of feet ambulated per nursing shift were collected. In addition, hospital day of physical therapy (PT) order and hospital days with PT performed were charted. Compliance with QI 3 in patients documented as ambulatory prior to hospital admission was recorded as present if there was a PT order within 48 hours of admission.

QI 4: Delirium Evaluation

During daily rounds, the hospitalist (PI) questioned nurses about delirium evaluation, using the first feature of the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) as well as the “single question in delirium,” namely, “Is there evidence of an acute change in mental status from the patient’s baseline?” and “Do you think [name of patient] has been more confused lately?”28,29 Because EMR does not contain a specified field for delirium screening and documentation, and patients are not routinely included in rounds, documentation with QI 4 was recorded using the “key words” method as described in the work by Puelle et al.30 To extract SCM key words, nursing documentation of the “cognitive/perceptual/neurological exam” section of the EMR on admission and on all subsequent documentation (once per shift) was retrieved to identify acute changes in mental status (eg, “altered mental status, delirium/delirious, alert and oriented X 3, confused/confusion, disoriented, lethargy/lethargic”).30 In addition, nurses were asked to activate an SCM parameter, “Acute Confusion” SCM parameter, in the nursing documentation section, which includes potential risk factors for confusion.

In addition to QI compliance, we collected LOS, discharge disposition, and 30-day readmission data.

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) for binary clustered (ie, hierarchical) data were used to estimate compliance rates (ie, nurse adherence) for each group (intervention group or control group) in the postintervention period, along with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. GLMM was used to account for the hierarchical structure of the data: nursing units within a hospital. In order to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index, we extracted past medical history from the EMR.31

Subjects (N = 2,396) were included in the comparison of the intervention group vs control group for each of the following 4 ACOVE QI compliance measures: DVT, mobilization, bladder catheter, and delirium.

RESULTS

Of the 2,396 patient admissions, 530 were in the intervention unit and 1,866 were in the control unit. In the intervention group, the average age was 84.65 years, 75.58% were white and 47.21% were married. There was no difference in patient demographics between groups (Table 2).

QI 1: VTE Prophylaxis

Compliance with VTE prophylaxis was met in 78.3% of the intervention subjects and 76.5% of the controls (P < .4371) (Table 3). Of note, the rate of VTE prophylaxis was 57% in the intervention vs 39% in the control group (P < .0056), in the 554 patients for whom compliance was not met. Mechanical prophylaxis was used in 35.6% of intervention subjects vs 30.6 in the control (P = .048). Patients who received no form of prophylaxis were 0.5% in the intervention and 3% in the control (P = .027).

QI 2: Indwelling Bladder Catheters

Out of 2,396 subjects, 406 had an indwelling bladder catheter (16.9%). Compliance with the catheter was met in 72.2% of the intervention group vs 54.4% in the control group (P = .1061). An indication for indwelling bladder catheters was documented in 100% of the subjects. The average number of catheter days was 5.16 in the intervention vs 5.88 in the control (P < .2284). There was statistical significance in catheter compliance in the longer stay (>15 days) subjects, decreasing to 23.32% in the control group while staying constant in the intervention group 71.5% (P = .0006).

QI 3: Mobilization

Of the 2,396 patients, 1,991 (83.1%) were reported as ambulatory prior to admission. In the intervention vs control group, 74 (14%) vs 297 (15.7%), respectively, were nonambulatory. Overall compliance with Q3 was 62.9% in the intervention vs 48.2% in the control (P < .0001). More specifically, the average time to PT order in the intervention group was 1.83 days vs 2.22 days in the control group (P <

QI 4: Delirium Evaluation

In terms of nursing documentation indicating the presence of an acute confusional state, the intervention group had 148 out of 530 nursing notes (27.9%) vs 405 out of 1,866 in the control group (21.7%; P = .0027). However, utilization of the “acute confusion” parameter with documentation of a risk factor did not differ between the groups (5.8% in the intervention group vs 5.6% in the control group, P < .94).

LOS, Discharge Disposition, and 30-Day Readmissions

LOS did not differ between intervention and control groups (6.37 days vs 6.27 days, respectively), with a median of 5 days (P = .877). Discharge disposition in the 2 groups included the following: home/home with services (71.32% vs 68.7%), skilled nursing facility/assisted living/long-term care (24.34 versus 25.83), inpatient hospice/home hospice (2.64 vs 2.25), and expired (1.13 vs 1.77; P < .3282). In addition, 30-day readmissions did not differ (21% vs 20%, respectively, P = .41).

DISCUSSION

Our goal was to explore an evidence-based, standardized approach to improve the care of hospitalized older adults. This approach leverages existing automated EMR alert functions with an additional level of decision support for VEs, integrated into daily multidisciplinary rounds. The use of a daily checklist-based tool offers a cost-effective and practical pathway to distribute the burden of compliance responsibility amongst team members.

As we anticipated and similar to study findings in hospitalized medicine, geriatric trauma, and primary care, compliance with general care QIs was better than geriatric-focused QIs.27,32 Wenger et al33 demonstrated significant improvements with screening for falls and incontinence; however, screening for cognitive impairment did not improve in the outpatient setting by imbedding ACOVE QIs into routine physician practice.

Increased compliance with VTE prophylaxis and indwelling bladder catheters may be explained by national financial incentives for widespread implementation of EMR alert systems. Conversely, mobilization, delirium assessment, and management in hospitalized older adults don’t benefit from similar incentives.

VTE Prophylaxis