User login

The enemy of good

“But no perfection is so absolute,

That some impurity doth not pollute.”

– William Shakespeare

While lounging in the ivory tower of academia, we frequently find ourselves condemning the peasantry who fail to grasp limitations of clinical trials. We deride the ignorant masses who insist on flaunting the inclusion criteria of the latest study and extrapolate the results to the ineligible patient sitting in front of them. The disrespect heaped on the “referring doctor” for treating their patients in the absence of evidence from prospective, randomized, multi-institutional trials is routine in conference rooms across the National Cancer Institute’s designated cancer centers.

The introduction of third-party insurers decades ago warped the economics of health care to the point that modern patients generally expect to pay little or nothing for pretty much any medical intervention. As a result, physicians tend to prescribe treatments without regard to cost. Predictably, this results in a steady increase in costs, which have now become unsustainable for our nation. Those rising costs have resulted in many proposals for control, including the Affordable Care Act and the efforts to reverse it. Many see a single payer, government administered system as the only viable way forward.

No matter the final system our society settles on, it will have to account for the almost miraculous results from modern therapeutics, which seem to be announced more and more frequently.

As I write this column, the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology is being held in Atlanta. The presentations recount studies of new agents alone, or in combination, that report unprecedented response and survival rates. In particular, cellular immunotherapy with chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR T cells) has captured the attention of physicians, patients, and investors. Simultaneously – and recognizing this revolution in oncologic therapeutics – the New England Journal of Medicine prepublished two papers presenting the results of CAR T-cell therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The results are impressive, and earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved axicabtagene ciloleucel for the treatment of relapsed or refractory DLBCL based on these data. An approval for tisagenlecleucel exists for the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but approval for DLBCL is likely forthcoming, too.

These are wonderful developments. Patients with incurable lymphoma may now be offered potentially curative treatment. Hematology News has covered the development of these treatments closely.

Yet, there is a glaring problem that has also attracted attention: CAR T-cell therapy is incredibly expensive. The potentially mitigating effect of competing products on cost will be canceled by the demand, as well as by geographic scarcity, because only certain large centers will provide this treatment. Remember that the price of imatinib went up over time even though competitors entered the market.

Entering CAR T-cell treatments into the nation’s formulary for some patients will lead to rising premiums for all patients. Disturbingly, CAR T cells are just a treatment for hematology patients at present. What about the equally impressive new – and expensive – technologies in cardiology, neurology, surgery, and every other medical subspecialty? Our system is already struggling to accommodate rapidly rising costs as our population ages and demands more and more medical care.

Many believe that our society will ultimately require strict controls on access to these expensive treatments. While the idea of rationing care is abhorrent to clinicians, “evidence-based” restrictions to access appear not to be. For example, rituximab is effective for immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), but is not FDA approved for it. Despite the restriction, rituximab is frequently used for ITP and generally reimbursed. Venetoclax is a useful agent for patients in relapse of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but the FDA only approved it for those harboring a deletion of 17p. While insurers seem willing to reimburse the use of rituximab for ITP, they balk at covering venetoclax for off-label indications. More recently, and more ominously for the implications, the FDA approval for tisagenlecleucel in the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia only extends to those up to age 25. That could mean a 26-year-old in relapse after an allogeneic transplant would be denied coverage for potentially curative CAR T-cell therapy.

The federal government is not the only bureaucracy with a financial interest in limiting access to expensive treatments. Commercial insurers have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders, not to the patients who consume their services. They employ thousands, among them physicians, tasked with reviewing our treatment recommendations to determine whether treatments will be paid for, often citing FDA approvals. Preauthorization for coverage results in innumerable treatment delays and added administrative costs that frustrate us and anger our patients. The insurers defend this incessant obstructionism by claiming they are protecting patients from unnecessary or unhelpful care. Like the FDA, they invoke our own penchant for evidence-based medicine or declare that some care pathway is the ultimate arbiter of truth in coverage determination. Therein lies the danger.

Where do you suppose the evidence and care pathways the FDA and insurers rely on come from? They come from academics like many of this publication’s readers. We gladly provide them with the data needed to restrict care. Through published studies in “major” journals, consensus guidelines promulgated through national organizations, and care pathways generated by our own institutions, we provide the fodder that feeds the regulatory apparatus that decides whose care is approved and paid for. As Walt Kelly’s Pogo stated in 1970, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

In the interest of science and in the interest of safety – but mostly in the interest of ensuring regulatory approval – clinical trials of new agents often restrict eligibility. Our group recently found that randomized trials routinely exclude patients for rather arbitrary organ dysfunction (Leukemia. 2017 Aug;31[8]:1808-15).

Another recent study concluded, “Current oncology clinical trials stipulate many inclusion and exclusion criteria that specifically define the patient population under study. Although eligibility criteria are needed to define the study population and improve safety, overly restrictive eligibility criteria limit participation in clinical trials, cause the study population to be unrepresentative of the general population of patients with cancer, and limit patient access to new treatments.” (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Nov 20;35[33]:3745-52).

Federal and private agencies will necessarily become stricter in their interpretations of studies and policies in order to control costs. They will happily cite the data we produce in order to do so. For the vast majority of patients who do not meet stringent inclusion criteria, access to new treatments may well be denied. To ensure that patients are provided with the best and most economical care, I am an advocate for evidence-based medicine and care pathways to standardize practice. However, I am progressively more wary of their potential to restrict the availability of innovative remedies to our patients who are not fortunate enough to meet exacting inclusion criteria. Faced with complex patients for whom no study applies, our colleagues in the fields who feed us need flexibility to provide the best care for their patients. Those of us in the ivory tower who determine such inclusion criteria should not let perfect be the enemy of good and must do everything we can to help them and our patients.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

“But no perfection is so absolute,

That some impurity doth not pollute.”

– William Shakespeare

While lounging in the ivory tower of academia, we frequently find ourselves condemning the peasantry who fail to grasp limitations of clinical trials. We deride the ignorant masses who insist on flaunting the inclusion criteria of the latest study and extrapolate the results to the ineligible patient sitting in front of them. The disrespect heaped on the “referring doctor” for treating their patients in the absence of evidence from prospective, randomized, multi-institutional trials is routine in conference rooms across the National Cancer Institute’s designated cancer centers.

The introduction of third-party insurers decades ago warped the economics of health care to the point that modern patients generally expect to pay little or nothing for pretty much any medical intervention. As a result, physicians tend to prescribe treatments without regard to cost. Predictably, this results in a steady increase in costs, which have now become unsustainable for our nation. Those rising costs have resulted in many proposals for control, including the Affordable Care Act and the efforts to reverse it. Many see a single payer, government administered system as the only viable way forward.

No matter the final system our society settles on, it will have to account for the almost miraculous results from modern therapeutics, which seem to be announced more and more frequently.

As I write this column, the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology is being held in Atlanta. The presentations recount studies of new agents alone, or in combination, that report unprecedented response and survival rates. In particular, cellular immunotherapy with chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR T cells) has captured the attention of physicians, patients, and investors. Simultaneously – and recognizing this revolution in oncologic therapeutics – the New England Journal of Medicine prepublished two papers presenting the results of CAR T-cell therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The results are impressive, and earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved axicabtagene ciloleucel for the treatment of relapsed or refractory DLBCL based on these data. An approval for tisagenlecleucel exists for the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but approval for DLBCL is likely forthcoming, too.

These are wonderful developments. Patients with incurable lymphoma may now be offered potentially curative treatment. Hematology News has covered the development of these treatments closely.

Yet, there is a glaring problem that has also attracted attention: CAR T-cell therapy is incredibly expensive. The potentially mitigating effect of competing products on cost will be canceled by the demand, as well as by geographic scarcity, because only certain large centers will provide this treatment. Remember that the price of imatinib went up over time even though competitors entered the market.

Entering CAR T-cell treatments into the nation’s formulary for some patients will lead to rising premiums for all patients. Disturbingly, CAR T cells are just a treatment for hematology patients at present. What about the equally impressive new – and expensive – technologies in cardiology, neurology, surgery, and every other medical subspecialty? Our system is already struggling to accommodate rapidly rising costs as our population ages and demands more and more medical care.

Many believe that our society will ultimately require strict controls on access to these expensive treatments. While the idea of rationing care is abhorrent to clinicians, “evidence-based” restrictions to access appear not to be. For example, rituximab is effective for immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), but is not FDA approved for it. Despite the restriction, rituximab is frequently used for ITP and generally reimbursed. Venetoclax is a useful agent for patients in relapse of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but the FDA only approved it for those harboring a deletion of 17p. While insurers seem willing to reimburse the use of rituximab for ITP, they balk at covering venetoclax for off-label indications. More recently, and more ominously for the implications, the FDA approval for tisagenlecleucel in the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia only extends to those up to age 25. That could mean a 26-year-old in relapse after an allogeneic transplant would be denied coverage for potentially curative CAR T-cell therapy.

The federal government is not the only bureaucracy with a financial interest in limiting access to expensive treatments. Commercial insurers have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders, not to the patients who consume their services. They employ thousands, among them physicians, tasked with reviewing our treatment recommendations to determine whether treatments will be paid for, often citing FDA approvals. Preauthorization for coverage results in innumerable treatment delays and added administrative costs that frustrate us and anger our patients. The insurers defend this incessant obstructionism by claiming they are protecting patients from unnecessary or unhelpful care. Like the FDA, they invoke our own penchant for evidence-based medicine or declare that some care pathway is the ultimate arbiter of truth in coverage determination. Therein lies the danger.

Where do you suppose the evidence and care pathways the FDA and insurers rely on come from? They come from academics like many of this publication’s readers. We gladly provide them with the data needed to restrict care. Through published studies in “major” journals, consensus guidelines promulgated through national organizations, and care pathways generated by our own institutions, we provide the fodder that feeds the regulatory apparatus that decides whose care is approved and paid for. As Walt Kelly’s Pogo stated in 1970, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

In the interest of science and in the interest of safety – but mostly in the interest of ensuring regulatory approval – clinical trials of new agents often restrict eligibility. Our group recently found that randomized trials routinely exclude patients for rather arbitrary organ dysfunction (Leukemia. 2017 Aug;31[8]:1808-15).

Another recent study concluded, “Current oncology clinical trials stipulate many inclusion and exclusion criteria that specifically define the patient population under study. Although eligibility criteria are needed to define the study population and improve safety, overly restrictive eligibility criteria limit participation in clinical trials, cause the study population to be unrepresentative of the general population of patients with cancer, and limit patient access to new treatments.” (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Nov 20;35[33]:3745-52).

Federal and private agencies will necessarily become stricter in their interpretations of studies and policies in order to control costs. They will happily cite the data we produce in order to do so. For the vast majority of patients who do not meet stringent inclusion criteria, access to new treatments may well be denied. To ensure that patients are provided with the best and most economical care, I am an advocate for evidence-based medicine and care pathways to standardize practice. However, I am progressively more wary of their potential to restrict the availability of innovative remedies to our patients who are not fortunate enough to meet exacting inclusion criteria. Faced with complex patients for whom no study applies, our colleagues in the fields who feed us need flexibility to provide the best care for their patients. Those of us in the ivory tower who determine such inclusion criteria should not let perfect be the enemy of good and must do everything we can to help them and our patients.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

“But no perfection is so absolute,

That some impurity doth not pollute.”

– William Shakespeare

While lounging in the ivory tower of academia, we frequently find ourselves condemning the peasantry who fail to grasp limitations of clinical trials. We deride the ignorant masses who insist on flaunting the inclusion criteria of the latest study and extrapolate the results to the ineligible patient sitting in front of them. The disrespect heaped on the “referring doctor” for treating their patients in the absence of evidence from prospective, randomized, multi-institutional trials is routine in conference rooms across the National Cancer Institute’s designated cancer centers.

The introduction of third-party insurers decades ago warped the economics of health care to the point that modern patients generally expect to pay little or nothing for pretty much any medical intervention. As a result, physicians tend to prescribe treatments without regard to cost. Predictably, this results in a steady increase in costs, which have now become unsustainable for our nation. Those rising costs have resulted in many proposals for control, including the Affordable Care Act and the efforts to reverse it. Many see a single payer, government administered system as the only viable way forward.

No matter the final system our society settles on, it will have to account for the almost miraculous results from modern therapeutics, which seem to be announced more and more frequently.

As I write this column, the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology is being held in Atlanta. The presentations recount studies of new agents alone, or in combination, that report unprecedented response and survival rates. In particular, cellular immunotherapy with chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR T cells) has captured the attention of physicians, patients, and investors. Simultaneously – and recognizing this revolution in oncologic therapeutics – the New England Journal of Medicine prepublished two papers presenting the results of CAR T-cell therapy for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). The results are impressive, and earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved axicabtagene ciloleucel for the treatment of relapsed or refractory DLBCL based on these data. An approval for tisagenlecleucel exists for the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, but approval for DLBCL is likely forthcoming, too.

These are wonderful developments. Patients with incurable lymphoma may now be offered potentially curative treatment. Hematology News has covered the development of these treatments closely.

Yet, there is a glaring problem that has also attracted attention: CAR T-cell therapy is incredibly expensive. The potentially mitigating effect of competing products on cost will be canceled by the demand, as well as by geographic scarcity, because only certain large centers will provide this treatment. Remember that the price of imatinib went up over time even though competitors entered the market.

Entering CAR T-cell treatments into the nation’s formulary for some patients will lead to rising premiums for all patients. Disturbingly, CAR T cells are just a treatment for hematology patients at present. What about the equally impressive new – and expensive – technologies in cardiology, neurology, surgery, and every other medical subspecialty? Our system is already struggling to accommodate rapidly rising costs as our population ages and demands more and more medical care.

Many believe that our society will ultimately require strict controls on access to these expensive treatments. While the idea of rationing care is abhorrent to clinicians, “evidence-based” restrictions to access appear not to be. For example, rituximab is effective for immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP), but is not FDA approved for it. Despite the restriction, rituximab is frequently used for ITP and generally reimbursed. Venetoclax is a useful agent for patients in relapse of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, but the FDA only approved it for those harboring a deletion of 17p. While insurers seem willing to reimburse the use of rituximab for ITP, they balk at covering venetoclax for off-label indications. More recently, and more ominously for the implications, the FDA approval for tisagenlecleucel in the treatment of B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia only extends to those up to age 25. That could mean a 26-year-old in relapse after an allogeneic transplant would be denied coverage for potentially curative CAR T-cell therapy.

The federal government is not the only bureaucracy with a financial interest in limiting access to expensive treatments. Commercial insurers have a fiduciary duty to their shareholders, not to the patients who consume their services. They employ thousands, among them physicians, tasked with reviewing our treatment recommendations to determine whether treatments will be paid for, often citing FDA approvals. Preauthorization for coverage results in innumerable treatment delays and added administrative costs that frustrate us and anger our patients. The insurers defend this incessant obstructionism by claiming they are protecting patients from unnecessary or unhelpful care. Like the FDA, they invoke our own penchant for evidence-based medicine or declare that some care pathway is the ultimate arbiter of truth in coverage determination. Therein lies the danger.

Where do you suppose the evidence and care pathways the FDA and insurers rely on come from? They come from academics like many of this publication’s readers. We gladly provide them with the data needed to restrict care. Through published studies in “major” journals, consensus guidelines promulgated through national organizations, and care pathways generated by our own institutions, we provide the fodder that feeds the regulatory apparatus that decides whose care is approved and paid for. As Walt Kelly’s Pogo stated in 1970, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

In the interest of science and in the interest of safety – but mostly in the interest of ensuring regulatory approval – clinical trials of new agents often restrict eligibility. Our group recently found that randomized trials routinely exclude patients for rather arbitrary organ dysfunction (Leukemia. 2017 Aug;31[8]:1808-15).

Another recent study concluded, “Current oncology clinical trials stipulate many inclusion and exclusion criteria that specifically define the patient population under study. Although eligibility criteria are needed to define the study population and improve safety, overly restrictive eligibility criteria limit participation in clinical trials, cause the study population to be unrepresentative of the general population of patients with cancer, and limit patient access to new treatments.” (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Nov 20;35[33]:3745-52).

Federal and private agencies will necessarily become stricter in their interpretations of studies and policies in order to control costs. They will happily cite the data we produce in order to do so. For the vast majority of patients who do not meet stringent inclusion criteria, access to new treatments may well be denied. To ensure that patients are provided with the best and most economical care, I am an advocate for evidence-based medicine and care pathways to standardize practice. However, I am progressively more wary of their potential to restrict the availability of innovative remedies to our patients who are not fortunate enough to meet exacting inclusion criteria. Faced with complex patients for whom no study applies, our colleagues in the fields who feed us need flexibility to provide the best care for their patients. Those of us in the ivory tower who determine such inclusion criteria should not let perfect be the enemy of good and must do everything we can to help them and our patients.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

Leadership hacks: structural tension

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

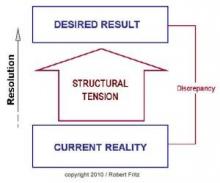

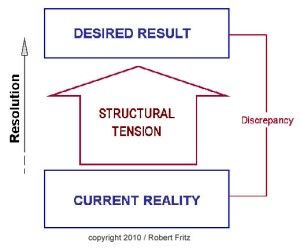

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

My leadership experience was limited when I became department chair 6 years ago. Recognizing the deficit immediately, I began reading self-help and leadership books, sought training in coaching techniques, and have attended innumerable leadership courses. I still have a lot to learn, but I am a lot more comfortable with my leadership skills than I was. Since I am often asked for advice with regard to advancing into administrative leadership positions, I want to share what I have learned with others.

In one of my previous columns, I reviewed the concept of drama triangles and introduced structural tension as a model for addressing and breaking them. The structural tension model is attributed to Robert Fritz and is presented in Figure 1. I have found this model very helpful for coaching toward desired change.

Kelly, the supervisor/manager/director/chairman, expects all physicians to carry a heavy clinical load while also conducting research, writing papers, and securing as many grants as possible. Of course, the expected clinical load encroaches on the time required for academic pursuits. Tension increases among the faculty as the clinical load prohibits academic work resulting in unmet expectations for Kelly and dissatisfaction and disengagement for everyone else. A staff meeting is called to address the worsening workplace environment.

Since Kelly is at a loss, the administrator, Pat, offers to run the meeting in an attempt to address the problem. Pat asks the assembled team to describe the ideal state, or desired result, for the department. Eagerly, the participants begin to list the components of their ideal state including error-free scheduling, adequate staffing, an efficient electronic medical record, uninterrupted administrative time, sufficient research support, and several other important requirements to successfully meet department expectations.

Next, Pat asks the staff to list the current state. Once again, the participants are more than happy to call out the current situation as they see it, including patients arriving without records, slow rooming times, add-on appointments outside clinic schedules, poor statistical support, and several other impediments to optimal efficiency.

Critically, Pat resists the temptation to recount and defend all the efforts being made to address each of these difficult issues. Instead, Pat asks the team what they can do to begin moving from the current state to the ideal state. In contrast to the other questions, the team hesitates to answer this one. The administration is supposed to fix the problems, not them. Pat persists, though, and is willing to wait in awkward silence for someone to offer a suggestion. Finally, a junior faculty member speaks up and recommends that the physician staff meet with the schedulers to reconfigure their clinic templates to more realistically reflect their available time. As murmurs flow across the room, another physician offers that perhaps they could cross cover for each other to allow uninterrupted administrative time. More and more physicians then join in suggesting more and more opportunities to streamline processes to create efficiencies.

Reflecting on the meeting afterward, Kelly was astounded not only at the process, but at the engagement of the faculty. Kelly was under the impression that the faculty was too frustrated to effectively participate. Pat was thrilled to have so many good ideas to work on. Importantly, these ideas came from the staff (bottom-up) rather than from administration (top-down), which increases staff involvement in the projects already set up in addition to creating new ones. The staff, in turn, felt that their concerns were heard and were inspired to take on the new challenges they created for themselves.

The structural tension model is more nuanced than my illustrative example suggests, but it does provide a useful framework to address problems and create solutions. Different problems, though, lend themselves to different solutions and structural tension cannot address every problem a leader faces. It is just one more tool in the leadership toolbox.

For more reading: Fritz R, “The Path of Least Resistance” (New York: Random House, 1984).

How would you treat ... recurrent pre-B ALL in a 24-year-old woman?

Welcome to our new online feature, "How would you treat?"

This new item seeks to stimulate a lively conversation around cases that address the "art of medicine," in which there are no right or wrong ways to treat a specific patient. Instead, we posit to you "if this was your patient, how would you treat her?" The goal is to offer each other our thoughts on how we view treatment options from the perspectives of potential for cure and quality of life for a specific patient given his or her unique treatment history.

Our first case for your consideration will examine perspectives on the treatment of recurrent acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a condition with increasing therapeutic options.

A 24-year-old female was diagnosed with pre-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. She achieved complete remission on a standard chemotherapy protocol that included L-asparaginase and completed maintenance therapy 1 year ago, but no tests for MRD were performed. Routine surveillance blood counts worsened and a bone marrow biopsy confirms relapse. She feels well. There is no detectable BCR/ABL, but the leukemic blasts express CD19, CD20, and CD22. She has an HLA-matched sibling donor. Her exam is normal with WBC 23,000 (76% Blasts), Hgb 10.3, Plt 32K.

Welcome to our new online feature, "How would you treat?"

This new item seeks to stimulate a lively conversation around cases that address the "art of medicine," in which there are no right or wrong ways to treat a specific patient. Instead, we posit to you "if this was your patient, how would you treat her?" The goal is to offer each other our thoughts on how we view treatment options from the perspectives of potential for cure and quality of life for a specific patient given his or her unique treatment history.

Our first case for your consideration will examine perspectives on the treatment of recurrent acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a condition with increasing therapeutic options.

A 24-year-old female was diagnosed with pre-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. She achieved complete remission on a standard chemotherapy protocol that included L-asparaginase and completed maintenance therapy 1 year ago, but no tests for MRD were performed. Routine surveillance blood counts worsened and a bone marrow biopsy confirms relapse. She feels well. There is no detectable BCR/ABL, but the leukemic blasts express CD19, CD20, and CD22. She has an HLA-matched sibling donor. Her exam is normal with WBC 23,000 (76% Blasts), Hgb 10.3, Plt 32K.

Welcome to our new online feature, "How would you treat?"

This new item seeks to stimulate a lively conversation around cases that address the "art of medicine," in which there are no right or wrong ways to treat a specific patient. Instead, we posit to you "if this was your patient, how would you treat her?" The goal is to offer each other our thoughts on how we view treatment options from the perspectives of potential for cure and quality of life for a specific patient given his or her unique treatment history.

Our first case for your consideration will examine perspectives on the treatment of recurrent acute lymphoblastic leukemia, a condition with increasing therapeutic options.

A 24-year-old female was diagnosed with pre-B Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. She achieved complete remission on a standard chemotherapy protocol that included L-asparaginase and completed maintenance therapy 1 year ago, but no tests for MRD were performed. Routine surveillance blood counts worsened and a bone marrow biopsy confirms relapse. She feels well. There is no detectable BCR/ABL, but the leukemic blasts express CD19, CD20, and CD22. She has an HLA-matched sibling donor. Her exam is normal with WBC 23,000 (76% Blasts), Hgb 10.3, Plt 32K.

Successful teams

As physicians, we know, and have been taught, that success comes from being smart and answering questions correctly. By doing so, we excelled in school, scored high on standardized tests, and confidently raised our hands in class. As a result, we were chosen for plum assignments like class officer, yearbook editor, and team captain. Success bred success and we were initiated into honor societies, accepted into prestigious internships, and allowed to work on important research projects.

These achievements guaranteed further success in medical school where the tradition of competition continued as we positioned for the attention of those who would someday write our letters of recommendation. This model of individual success served us very well until we joined a hematology group to begin our practice.

When we join a group of physicians, we join a team. The team might organize around diagnoses, laboratories, or geographic location, but it is a team nonetheless. The team, of course, includes more than just physicians. As a team member, we are expected to fulfill a role that advances the mission of the team and the larger organization. That mission may include some combination of academic, educational, and clinical productivity.

As physicians trained to compete with other individuals, teamwork does not come naturally. We might think that so long as the team consists of more and mor

As Margaret Heffernan brilliantly points out in “Margaret Heffernan: Why it’s time to forget the pecking order at work,” a TED talk video posted on YouTube, teams consisting of those skilled in interpersonal relationships are much more effective, efficient, and productive than are teams consisting of those skilled in problem-solving with superior IQs. The teams that function most successfully are those that create a culture of trust and helpfulness no matter the individual talents of those on the team.

As a department chair, I try to see past the thickness of the CV to ensure that I see into the person’s ability to relate with other people. If the CV is thick and the emotional intelligence high, then that is the person I want on my team, but I would rather have the latter than the former, and so would teammates and patients.

Research has shown repeatedly that no individuals can hope to achieve on their own what a good, functional team can achieve as a group. Yet, the academic hierarchy rewards individuals, not teams. Hopefully, the rewarded individual will recognize the support and effort of the team, but that is not always the case and not always done adequately.

How can academic departments develop social capital in their teams and reward them, in addition to individuals, for their successes? Social capital grows when the relationships between people become stronger. Those bonds develop though informal interaction outside the work environment. The more the team knows each other, the more they trust each other, the more they are willing to help each other, and the more they are likely to be civil to one another. Teams of friends are much more likely to solve problems quickly for less cost than teams of strangers.

Reward and recognition for a team is not as easy as it sounds. Everyone wants individual recognition for their work, not just as an integral member of a team. The world loves All-Stars and MVPs as much as they love their teams. We do not need to change the way we reward individuals, but we do need to also include teams for reward and recognition. How can a leader determine which teams are most deserving of the highest reward? Many institutions measure employee engagement through surveys. High-functioning teams are likely to be highly engaged and high scores on surveys should be recognized and rewarded. Teams with low employee turnover help reduce training costs and should be appreciated.

Successful implementation of continuous improvement projects are an often overlooked opportunity for an expression of gratitude. I am sure there are other ways to acknowledge a team’s efforts and I hope readers will write to us with their ideas for all to share. Perhaps by doing so, we can accelerate the cultural transformation of academic medicine from one of personal achievement to one of team success.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

As physicians, we know, and have been taught, that success comes from being smart and answering questions correctly. By doing so, we excelled in school, scored high on standardized tests, and confidently raised our hands in class. As a result, we were chosen for plum assignments like class officer, yearbook editor, and team captain. Success bred success and we were initiated into honor societies, accepted into prestigious internships, and allowed to work on important research projects.

These achievements guaranteed further success in medical school where the tradition of competition continued as we positioned for the attention of those who would someday write our letters of recommendation. This model of individual success served us very well until we joined a hematology group to begin our practice.

When we join a group of physicians, we join a team. The team might organize around diagnoses, laboratories, or geographic location, but it is a team nonetheless. The team, of course, includes more than just physicians. As a team member, we are expected to fulfill a role that advances the mission of the team and the larger organization. That mission may include some combination of academic, educational, and clinical productivity.

As physicians trained to compete with other individuals, teamwork does not come naturally. We might think that so long as the team consists of more and mor

As Margaret Heffernan brilliantly points out in “Margaret Heffernan: Why it’s time to forget the pecking order at work,” a TED talk video posted on YouTube, teams consisting of those skilled in interpersonal relationships are much more effective, efficient, and productive than are teams consisting of those skilled in problem-solving with superior IQs. The teams that function most successfully are those that create a culture of trust and helpfulness no matter the individual talents of those on the team.

As a department chair, I try to see past the thickness of the CV to ensure that I see into the person’s ability to relate with other people. If the CV is thick and the emotional intelligence high, then that is the person I want on my team, but I would rather have the latter than the former, and so would teammates and patients.

Research has shown repeatedly that no individuals can hope to achieve on their own what a good, functional team can achieve as a group. Yet, the academic hierarchy rewards individuals, not teams. Hopefully, the rewarded individual will recognize the support and effort of the team, but that is not always the case and not always done adequately.

How can academic departments develop social capital in their teams and reward them, in addition to individuals, for their successes? Social capital grows when the relationships between people become stronger. Those bonds develop though informal interaction outside the work environment. The more the team knows each other, the more they trust each other, the more they are willing to help each other, and the more they are likely to be civil to one another. Teams of friends are much more likely to solve problems quickly for less cost than teams of strangers.

Reward and recognition for a team is not as easy as it sounds. Everyone wants individual recognition for their work, not just as an integral member of a team. The world loves All-Stars and MVPs as much as they love their teams. We do not need to change the way we reward individuals, but we do need to also include teams for reward and recognition. How can a leader determine which teams are most deserving of the highest reward? Many institutions measure employee engagement through surveys. High-functioning teams are likely to be highly engaged and high scores on surveys should be recognized and rewarded. Teams with low employee turnover help reduce training costs and should be appreciated.

Successful implementation of continuous improvement projects are an often overlooked opportunity for an expression of gratitude. I am sure there are other ways to acknowledge a team’s efforts and I hope readers will write to us with their ideas for all to share. Perhaps by doing so, we can accelerate the cultural transformation of academic medicine from one of personal achievement to one of team success.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

As physicians, we know, and have been taught, that success comes from being smart and answering questions correctly. By doing so, we excelled in school, scored high on standardized tests, and confidently raised our hands in class. As a result, we were chosen for plum assignments like class officer, yearbook editor, and team captain. Success bred success and we were initiated into honor societies, accepted into prestigious internships, and allowed to work on important research projects.

These achievements guaranteed further success in medical school where the tradition of competition continued as we positioned for the attention of those who would someday write our letters of recommendation. This model of individual success served us very well until we joined a hematology group to begin our practice.

When we join a group of physicians, we join a team. The team might organize around diagnoses, laboratories, or geographic location, but it is a team nonetheless. The team, of course, includes more than just physicians. As a team member, we are expected to fulfill a role that advances the mission of the team and the larger organization. That mission may include some combination of academic, educational, and clinical productivity.

As physicians trained to compete with other individuals, teamwork does not come naturally. We might think that so long as the team consists of more and mor

As Margaret Heffernan brilliantly points out in “Margaret Heffernan: Why it’s time to forget the pecking order at work,” a TED talk video posted on YouTube, teams consisting of those skilled in interpersonal relationships are much more effective, efficient, and productive than are teams consisting of those skilled in problem-solving with superior IQs. The teams that function most successfully are those that create a culture of trust and helpfulness no matter the individual talents of those on the team.

As a department chair, I try to see past the thickness of the CV to ensure that I see into the person’s ability to relate with other people. If the CV is thick and the emotional intelligence high, then that is the person I want on my team, but I would rather have the latter than the former, and so would teammates and patients.

Research has shown repeatedly that no individuals can hope to achieve on their own what a good, functional team can achieve as a group. Yet, the academic hierarchy rewards individuals, not teams. Hopefully, the rewarded individual will recognize the support and effort of the team, but that is not always the case and not always done adequately.

How can academic departments develop social capital in their teams and reward them, in addition to individuals, for their successes? Social capital grows when the relationships between people become stronger. Those bonds develop though informal interaction outside the work environment. The more the team knows each other, the more they trust each other, the more they are willing to help each other, and the more they are likely to be civil to one another. Teams of friends are much more likely to solve problems quickly for less cost than teams of strangers.

Reward and recognition for a team is not as easy as it sounds. Everyone wants individual recognition for their work, not just as an integral member of a team. The world loves All-Stars and MVPs as much as they love their teams. We do not need to change the way we reward individuals, but we do need to also include teams for reward and recognition. How can a leader determine which teams are most deserving of the highest reward? Many institutions measure employee engagement through surveys. High-functioning teams are likely to be highly engaged and high scores on surveys should be recognized and rewarded. Teams with low employee turnover help reduce training costs and should be appreciated.

Successful implementation of continuous improvement projects are an often overlooked opportunity for an expression of gratitude. I am sure there are other ways to acknowledge a team’s efforts and I hope readers will write to us with their ideas for all to share. Perhaps by doing so, we can accelerate the cultural transformation of academic medicine from one of personal achievement to one of team success.

Dr. Kalaycio is editor in chief of Hematology News. He chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

Defining high reliability

When the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations came to our hospital for a survey last fall, our administration was confident that the review would be favorable. The Joint Commission was stressing the reliability of hospitals and so were we. We had chartered a “High-Reliability Organization Enterprise Steering Committee” that was “empowered to make recommendations to the (executive board) on what is needed to achieve the goals of high reliability across the enterprise.” High reliability was a priority for our administration and for the Joint Commission. Unfortunately, nearly no one else knew what high reliability meant.

In 2001, Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe published their book, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty,” (Hoboken, N.J.: Jossey-Bass, 2001), which defined high-reliability organizations as those that reliably prevent error. They included examples from the military and from aviation. They proffered five principles to guide those organizations wishing to become highly reliable:

1. Preoccupation with failure.

2. Reluctance to simplify interpretations.

3. Sensitivity to operations.

4. Commitment to resilience.

5. Deference to expertise.

In September 2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality created a document to adapt the concepts developed by Mr. Weick and Ms. Sutcliffe to the health care industry, where opportunities to avoid error and prevent catastrophe abound. The eventual result has been steady progress in measuring avoidable health care errors, such as avoiding central line–associated blood stream infections and holding health care organizations accountable for their reduction. However, organizational cultures are difficult to change, and there is still a long way to go.

In contrast to large systems, individual providers can change quickly, especially if there is incentive to do so. What principles would increase our own ability to become a high-reliability individuals (HRIs):

• Recognize failure as systemic, not personal. Health care providers are humans, and humans make mistakes. Unfortunately, we come from a tradition that rewards success and penalizes failure. Research shows that is better to recognize failure as something to be prevented next time rather than to be punished now. Admonitions to pay attention, focus more, and remember better rely on fallible humans and reliably fail. Systems solutions, such as checklists, timeouts, and hard stops reliably succeed. HRIs should blame error less often on people, and more often on system failures.

• Simple solutions are preferred to complex requirements. Chemotherapy was once calculated and written by hand. Every cancer center can recall tragic disasters that occurred as a result of errors either by the ordering physician or by interpretations made by pharmacists and nurses. The introduction of electronic chemotherapy ordering has nearly eliminated these mistakes. HRIs can initiate technology solutions to their work to help reduce the risk of errors.

• Sensitivity to patients. Patients often desire to be included as partners in their care. In addition to being present and attentive to patients, why not enlist them as colleagues in care? For example, the patient who has their own calendar of chemotherapy treatments – complete with agents, doses, and schedules – will be more likely to question perceived errors. HRIs are transparent.

• Resilience in character. Learning to accept the potential for error requires acceptance that others also are trying to prevent error and are not judging your competence. The physician who attacks those who are trying to help reduces the psychological safety required for colleagues to speak up when potential errors are identified. Physicians will become HRIs only when they lower their defenses and become more teammates rather than a soloists.

• Deference to evidence. The “way it has always been” must give way to the way things are. Anecdotes and personal conviction do not meet scientific standards and should be abandoned in the face of evidence. Yet, this seemingly obvious principle often is disregarded when clinicians are presented with standardized treatment pathways and limited formularies in the name of autonomy; autonomy is fine until patients are endangered by it. The HRI practices evidence-based medicine.

Marty Makary, MD, explores most of these principles in his book “Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care”(London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012). While written from a surgeon’s perspective, Dr. Makary exposes the dangerous state of modern medical care across all specialties. I recommend it as a sobering assessment of the way things are and as a prescription for health care systems and physicians to help them become more reliable.

How are you driving safety in your area? What are some best practices we can share with others? I invite you to reply to hematologynews@frontlinemedcom.com to initiate a broader discussion of patient safety and reliability. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

When the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations came to our hospital for a survey last fall, our administration was confident that the review would be favorable. The Joint Commission was stressing the reliability of hospitals and so were we. We had chartered a “High-Reliability Organization Enterprise Steering Committee” that was “empowered to make recommendations to the (executive board) on what is needed to achieve the goals of high reliability across the enterprise.” High reliability was a priority for our administration and for the Joint Commission. Unfortunately, nearly no one else knew what high reliability meant.

In 2001, Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe published their book, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty,” (Hoboken, N.J.: Jossey-Bass, 2001), which defined high-reliability organizations as those that reliably prevent error. They included examples from the military and from aviation. They proffered five principles to guide those organizations wishing to become highly reliable:

1. Preoccupation with failure.

2. Reluctance to simplify interpretations.

3. Sensitivity to operations.

4. Commitment to resilience.

5. Deference to expertise.

In September 2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality created a document to adapt the concepts developed by Mr. Weick and Ms. Sutcliffe to the health care industry, where opportunities to avoid error and prevent catastrophe abound. The eventual result has been steady progress in measuring avoidable health care errors, such as avoiding central line–associated blood stream infections and holding health care organizations accountable for their reduction. However, organizational cultures are difficult to change, and there is still a long way to go.

In contrast to large systems, individual providers can change quickly, especially if there is incentive to do so. What principles would increase our own ability to become a high-reliability individuals (HRIs):

• Recognize failure as systemic, not personal. Health care providers are humans, and humans make mistakes. Unfortunately, we come from a tradition that rewards success and penalizes failure. Research shows that is better to recognize failure as something to be prevented next time rather than to be punished now. Admonitions to pay attention, focus more, and remember better rely on fallible humans and reliably fail. Systems solutions, such as checklists, timeouts, and hard stops reliably succeed. HRIs should blame error less often on people, and more often on system failures.

• Simple solutions are preferred to complex requirements. Chemotherapy was once calculated and written by hand. Every cancer center can recall tragic disasters that occurred as a result of errors either by the ordering physician or by interpretations made by pharmacists and nurses. The introduction of electronic chemotherapy ordering has nearly eliminated these mistakes. HRIs can initiate technology solutions to their work to help reduce the risk of errors.

• Sensitivity to patients. Patients often desire to be included as partners in their care. In addition to being present and attentive to patients, why not enlist them as colleagues in care? For example, the patient who has their own calendar of chemotherapy treatments – complete with agents, doses, and schedules – will be more likely to question perceived errors. HRIs are transparent.

• Resilience in character. Learning to accept the potential for error requires acceptance that others also are trying to prevent error and are not judging your competence. The physician who attacks those who are trying to help reduces the psychological safety required for colleagues to speak up when potential errors are identified. Physicians will become HRIs only when they lower their defenses and become more teammates rather than a soloists.

• Deference to evidence. The “way it has always been” must give way to the way things are. Anecdotes and personal conviction do not meet scientific standards and should be abandoned in the face of evidence. Yet, this seemingly obvious principle often is disregarded when clinicians are presented with standardized treatment pathways and limited formularies in the name of autonomy; autonomy is fine until patients are endangered by it. The HRI practices evidence-based medicine.

Marty Makary, MD, explores most of these principles in his book “Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care”(London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012). While written from a surgeon’s perspective, Dr. Makary exposes the dangerous state of modern medical care across all specialties. I recommend it as a sobering assessment of the way things are and as a prescription for health care systems and physicians to help them become more reliable.

How are you driving safety in your area? What are some best practices we can share with others? I invite you to reply to hematologynews@frontlinemedcom.com to initiate a broader discussion of patient safety and reliability. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

When the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations came to our hospital for a survey last fall, our administration was confident that the review would be favorable. The Joint Commission was stressing the reliability of hospitals and so were we. We had chartered a “High-Reliability Organization Enterprise Steering Committee” that was “empowered to make recommendations to the (executive board) on what is needed to achieve the goals of high reliability across the enterprise.” High reliability was a priority for our administration and for the Joint Commission. Unfortunately, nearly no one else knew what high reliability meant.

In 2001, Karl E. Weick and Kathleen M. Sutcliffe published their book, “Managing the Unexpected: Resilient Performance in an Age of Uncertainty,” (Hoboken, N.J.: Jossey-Bass, 2001), which defined high-reliability organizations as those that reliably prevent error. They included examples from the military and from aviation. They proffered five principles to guide those organizations wishing to become highly reliable:

1. Preoccupation with failure.

2. Reluctance to simplify interpretations.

3. Sensitivity to operations.

4. Commitment to resilience.

5. Deference to expertise.

In September 2005, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality created a document to adapt the concepts developed by Mr. Weick and Ms. Sutcliffe to the health care industry, where opportunities to avoid error and prevent catastrophe abound. The eventual result has been steady progress in measuring avoidable health care errors, such as avoiding central line–associated blood stream infections and holding health care organizations accountable for their reduction. However, organizational cultures are difficult to change, and there is still a long way to go.

In contrast to large systems, individual providers can change quickly, especially if there is incentive to do so. What principles would increase our own ability to become a high-reliability individuals (HRIs):

• Recognize failure as systemic, not personal. Health care providers are humans, and humans make mistakes. Unfortunately, we come from a tradition that rewards success and penalizes failure. Research shows that is better to recognize failure as something to be prevented next time rather than to be punished now. Admonitions to pay attention, focus more, and remember better rely on fallible humans and reliably fail. Systems solutions, such as checklists, timeouts, and hard stops reliably succeed. HRIs should blame error less often on people, and more often on system failures.

• Simple solutions are preferred to complex requirements. Chemotherapy was once calculated and written by hand. Every cancer center can recall tragic disasters that occurred as a result of errors either by the ordering physician or by interpretations made by pharmacists and nurses. The introduction of electronic chemotherapy ordering has nearly eliminated these mistakes. HRIs can initiate technology solutions to their work to help reduce the risk of errors.

• Sensitivity to patients. Patients often desire to be included as partners in their care. In addition to being present and attentive to patients, why not enlist them as colleagues in care? For example, the patient who has their own calendar of chemotherapy treatments – complete with agents, doses, and schedules – will be more likely to question perceived errors. HRIs are transparent.

• Resilience in character. Learning to accept the potential for error requires acceptance that others also are trying to prevent error and are not judging your competence. The physician who attacks those who are trying to help reduces the psychological safety required for colleagues to speak up when potential errors are identified. Physicians will become HRIs only when they lower their defenses and become more teammates rather than a soloists.

• Deference to evidence. The “way it has always been” must give way to the way things are. Anecdotes and personal conviction do not meet scientific standards and should be abandoned in the face of evidence. Yet, this seemingly obvious principle often is disregarded when clinicians are presented with standardized treatment pathways and limited formularies in the name of autonomy; autonomy is fine until patients are endangered by it. The HRI practices evidence-based medicine.

Marty Makary, MD, explores most of these principles in his book “Unaccountable: What Hospitals Won’t Tell You and How Transparency Can Revolutionize Health Care”(London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012). While written from a surgeon’s perspective, Dr. Makary exposes the dangerous state of modern medical care across all specialties. I recommend it as a sobering assessment of the way things are and as a prescription for health care systems and physicians to help them become more reliable.

How are you driving safety in your area? What are some best practices we can share with others? I invite you to reply to hematologynews@frontlinemedcom.com to initiate a broader discussion of patient safety and reliability. Responses will be posted to hematologynews.com.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

Professional time

As I write this article, the snow is piling up outside. While Cleveland’s west side citizens are raking up the last of fallen leaves, its east siders will dig out of 2 feet of snow. The lake effect is affecting us. The snow plow trucks vainly clear a path only for it to disappear in minutes. There seems to be no end to the torrents of white flakes that are each unique and tiny, but in aggregate uniform and overwhelming.

A blizzard of patients awaits my return from the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego. Like snowflakes, they are each unique, but in aggregate can be overwhelming. Plowing through a clinic, we go from patient to patient knowing that we will eventually see them all, then return to our offices or home to finish the labor of charting.

For some physicians, this is a daily reality. Whether patients in the clinic, or cases in the queue, some hematologists revisit the storm every day. Most, however, are engaged in an academic practice where at least some respite from direct patient care is offered. Whether teaching medical students, analyzing data, participating in administrative meetings, or writing manuscripts, most of us do something more beyond the clinic. We do this during our “protected time.”

But what are we protected from? Patients and their concerns? Really, this is what we want to be protected from?

“Protected” is the wrong word. The time we spend pursuing academics is really “professional” time. Some centers call it administrative time, but this also falls short. Time allotted to nonclinical activities keeps us fresh, sharpens our intellect, and ultimately helps our patients. Professional time helps prevent burnout by making us more present when we are in clinic. Professional time allows for scientific inquiry to advance treatments, and encourages continuing education to remain at the cutting edge of technology. Professional time, though, competes with patient time and that tension can drive disengagement.

Patients, and their problems, do not operate according to half-day clinic schedules. When there exists any professional time, patient time is always interfering. The interference becomes more acute as academic success increases and the allotted professional time seems inadequate. Hematologists then start to blame patients for interfering with their careers. A pernicious disdain for patient care may develop because it interrupts the academic motivations that drive many physicians once they get a taste of success. Manifestations of this attitude include dread of inpatient service, negotiations to reduce clinic time for research, and refusal to see or sometimes even talk to patients when not assigned to clinic. The more successful the academic hematologist becomes, the less he or she wants to be troubled with patients without whom professional success could not have been achieved.

The professional and patient time balance is as important to recognize as work and life balance, as one tension directly impacts the other. When nature sends a snowstorm, a warm home allows survival, but if one never ventures from home, the beauty and grandeur of nature is lost. True satisfaction comes from a balance of the two and no one person knows how best to accomplish it. I believe we can learn to manage our professional and patient time better by exchanging ideas and best practices. Please email me at kalaycm@ccf.org with your ideas and we will post as many as we can on the Hematology News website for all to learn from.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

As I write this article, the snow is piling up outside. While Cleveland’s west side citizens are raking up the last of fallen leaves, its east siders will dig out of 2 feet of snow. The lake effect is affecting us. The snow plow trucks vainly clear a path only for it to disappear in minutes. There seems to be no end to the torrents of white flakes that are each unique and tiny, but in aggregate uniform and overwhelming.

A blizzard of patients awaits my return from the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego. Like snowflakes, they are each unique, but in aggregate can be overwhelming. Plowing through a clinic, we go from patient to patient knowing that we will eventually see them all, then return to our offices or home to finish the labor of charting.

For some physicians, this is a daily reality. Whether patients in the clinic, or cases in the queue, some hematologists revisit the storm every day. Most, however, are engaged in an academic practice where at least some respite from direct patient care is offered. Whether teaching medical students, analyzing data, participating in administrative meetings, or writing manuscripts, most of us do something more beyond the clinic. We do this during our “protected time.”

But what are we protected from? Patients and their concerns? Really, this is what we want to be protected from?

“Protected” is the wrong word. The time we spend pursuing academics is really “professional” time. Some centers call it administrative time, but this also falls short. Time allotted to nonclinical activities keeps us fresh, sharpens our intellect, and ultimately helps our patients. Professional time helps prevent burnout by making us more present when we are in clinic. Professional time allows for scientific inquiry to advance treatments, and encourages continuing education to remain at the cutting edge of technology. Professional time, though, competes with patient time and that tension can drive disengagement.

Patients, and their problems, do not operate according to half-day clinic schedules. When there exists any professional time, patient time is always interfering. The interference becomes more acute as academic success increases and the allotted professional time seems inadequate. Hematologists then start to blame patients for interfering with their careers. A pernicious disdain for patient care may develop because it interrupts the academic motivations that drive many physicians once they get a taste of success. Manifestations of this attitude include dread of inpatient service, negotiations to reduce clinic time for research, and refusal to see or sometimes even talk to patients when not assigned to clinic. The more successful the academic hematologist becomes, the less he or she wants to be troubled with patients without whom professional success could not have been achieved.

The professional and patient time balance is as important to recognize as work and life balance, as one tension directly impacts the other. When nature sends a snowstorm, a warm home allows survival, but if one never ventures from home, the beauty and grandeur of nature is lost. True satisfaction comes from a balance of the two and no one person knows how best to accomplish it. I believe we can learn to manage our professional and patient time better by exchanging ideas and best practices. Please email me at kalaycm@ccf.org with your ideas and we will post as many as we can on the Hematology News website for all to learn from.

Dr. Kalaycio is Editor in Chief of Hematology News. Dr. Kalaycio chairs the department of hematologic oncology and blood disorders at Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Institute. Contact him at kalaycm@ccf.org.

As I write this article, the snow is piling up outside. While Cleveland’s west side citizens are raking up the last of fallen leaves, its east siders will dig out of 2 feet of snow. The lake effect is affecting us. The snow plow trucks vainly clear a path only for it to disappear in minutes. There seems to be no end to the torrents of white flakes that are each unique and tiny, but in aggregate uniform and overwhelming.

A blizzard of patients awaits my return from the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in San Diego. Like snowflakes, they are each unique, but in aggregate can be overwhelming. Plowing through a clinic, we go from patient to patient knowing that we will eventually see them all, then return to our offices or home to finish the labor of charting.

For some physicians, this is a daily reality. Whether patients in the clinic, or cases in the queue, some hematologists revisit the storm every day. Most, however, are engaged in an academic practice where at least some respite from direct patient care is offered. Whether teaching medical students, analyzing data, participating in administrative meetings, or writing manuscripts, most of us do something more beyond the clinic. We do this during our “protected time.”