User login

2023 Update on cervical disease

Cervical cancer was the most common cancer killer of persons with a cervix in the early 1900s in the United States. Widespread adoption of the Pap test in the mid-20th century followed by large-scale outreach through programs such as the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program have dramatically reduced deaths from cervical cancer. The development of a highly effective vaccine that targets human papillomavirus (HPV), the virus implicated in all cervical cancers, has made prevention even more accessible and attainable. Primary prevention with HPV vaccination in conjunction with regular screening as recommended by current guidelines is the most effective way we can prevent cervical cancer.

Despite these advances, the incidence and death rates from cervical cancer have plateaued over the last decade.1 Additionally, many fear that due to the poor attendance at screening visits since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence might further rise in the United States.2 Among those in the United States diagnosed with cervical cancer, more than 50% have not been screened in over 5 years or had their abnormal results not managed as recommended by current guidelines, suggesting that operational and access issues are contributors to incident cervical cancer. In addition, HPV vaccination rates have increased only slightly from year to year. According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), coverage with 1 or more doses of HPV vaccine in 2021 increased only by 1.8% and has stagnated, with administration to about 75% of those for whom it is recommended.3 The plateauing will limit our ability to eradicate cervical cancer in the United States, permitting death from a largely preventable disease.

Establishing the framework for the eradication of cervical cancer

The World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a global strategy called the Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative in August 2020. This initiative is a multipronged effort that focuses on vaccination (90% of girls fully vaccinated by age 15), screening (70% of women screened by age 35 with an effective test and again at age 45), and treatment (90% treatment of precancer and 90% management of women with invasive cancer).4

These are the numbers we need to achieve if all countries are to reach a cervical cancer incidence of less than 4 per 100,000 persons with a cervix. The WHO further suggests that each country should meet the “90-70-90” targets by 2030 if we are to achieve the low incidence by the turn of the century.4 To date, few regions of the world have achieved these goals, and sadly the United States is not among them.

In response to this call to action, many medical and policymaking organizations are taking inventory and implementing strategies to achieve the WHO 2030 targets for cervical cancer eradication. In the United States, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO; www.sgo.org), the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP; www.ASCCP.org), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG; www.acog.org), the American Cancer Society (ACS; www.cancer.org), and many others have initiated programs in a collaborative esprit de corps with the aim of eradicating this deadly disease.

In this Update, we review several studies with evidence of screening and management strategies that show promise of accelerating the eradication of cervical cancer.

Continue to: Transitioning to primary HPV screening in the United States...

Transitioning to primary HPV screening in the United States

Downs LS Jr, Nayar R, Gerndt J, et al; American Cancer Society Primary HPV Screening Initiative Steering Committee. Implementation in action: collaborating on the transition to primary HPV screening for cervical cancer in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:458-460.

The American Cancer Society released an updated cervical cancer screening guideline in July 2020 that recommended testing for HPV as the preferred strategy. Reasons behind the change, moving away from a Pap test as part of the initial screen, are:

- increased sensitivity of primary HPV testing when compared with conventional cervical cytology (Pap test)

- improved risk stratification to identify who is at risk for cervical cancer now and in the future

- improved efficiency in identifying those who need colposcopy, thus limiting unnecessary procedures without increasing the risk of false-negative tests, thereby missing cervical precancer or invasive cancer.

Some countries with organized screening programs have already made the switch. Self-sampling for HPV is currently being considered for an approved use in the United States, further improving access to screening for cervical cancer when the initial step can be completed by the patient at home or simplified in nontraditional health care settings.2

ACS initiative created to address barriers to primary HPV testing

Challenges to primary HPV testing remain, including laboratory implementation, payment, and operationalizing clinical workflow (for example, HPV testing with reflex cytology instead of cytology with reflex HPV testing).5 There are undoubtedly other unforeseen barriers in the current US health care environment.

In a recent commentary, Downs and colleagues described how the ACS has convened the Primary HPV Screening Initiative (PHSI), nested under the ACS National Roundtable on Cervical Cancer, which is charged with identifying critical barriers to, and opportunities for, transitioning to primary HPV screening.5 The deliverable will be a roadmap with tools and recommendations to support health systems, laboratories, providers, patients, and payers as they make this evolution.

Work groups will develop resources

Patients, particularly those who have had routine cervical cancer screening over their lifetime, also will be curious about the changes in recommendations. The Provider Needs Workgroup within the PHSI structure will develop tools and patient education materials regarding the data, workflow, benefits, and safety of this new paradigm for cervical cancer screening.

Laboratories that process and interpret tests likely will bear the heaviest load of changes. For example, not all commercially available HPV tests in the United States are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary HPV testing. Some sites will need to adapt their equipment to ensure adherence to FDA-approved tests. Laboratory workflows will need to be altered for aliquots to be tested for HPV first, and the remainder for cytology. Quality assurance and accreditation requirements for testing will need modifications, and further efforts will be needed to ensure sufficient numbers of trained cytopathologists, whose workforce is rapidly declining, for processing and reading cervical cytology.

In addition, payment for HPV testing alone, without the need for a Pap test, might not be supported by payers that support safety-net providers and sites, who arguably serve the most vulnerable patients and those most at risk for cervical cancer. Collaboration across medical professionals, societies, payers, and policymakers will provide a critical infrastructure to make the change in the most seamless fashion and limit the harm from missed opportunities for screening.

HPV testing as the primary screen for cervical cancer is now recommended in guidelines due to improved sensitivity and improved efficiency when compared with other methods of screening. Implementation of this new workflow for clinicians and labs will require collaboration across multiple stakeholders.

Continue to: The quest for a “molecular Pap”: Dual-stain testing as a predictor of high-grade CIN...

The quest for a “molecular Pap”: Dual-stain testing as a predictor of high-grade CIN

Magkana M, Mentzelopoulou P, Magkana E, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual staining is a reliable biomarker for risk stratification for patients with borderline/mild cytology in cervical cancer screening. Anticancer Res. 2022;42:2599-2606.

Stanczuk G, Currie H, Forson W, et al. Clinical performance of triage strategies for Hr-HPV-positive women; a longitudinal evaluation of cytology, p16/K-67 dual stain cytology, and HPV16/18 genotyping. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1492-1498.

One new technology that was recently FDA approved and recommended for management of abnormal cervical cancer screening testing is dual-stain (DS) testing. Dual-stain testing is a cytology-based test that evaluates the concurrent expression of p16, a tumor suppressor protein upregulated in HPV oncogenesis, and Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker.6,7 Two recent studies have showcased the outstanding clinical performance of DS testing and triage strategies that incorporate DS testing.

Higher specificity, fewer colposcopies needed with DS testing

Magkana and colleagues prospectively evaluated patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), or negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) cytology referred for colposcopy, and they compared p16/Ki-67 DS testing with high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN 2+); comparable sensitivities for CIN 2+ detection were seen (97.3% and 98.7%, respectively).8

Dual-stain testing exhibited higher specificity at 99.3% compared with HR-HPV testing at 52.2%. Incorporating DS testing into triage strategies also led to fewer colposcopies needed to detect CIN 2+ compared with current ASCCP guidelines that use traditional cervical cancer screening algorithms.

DS cytology strategy had the highest sensitivity for CIN 2+ detection

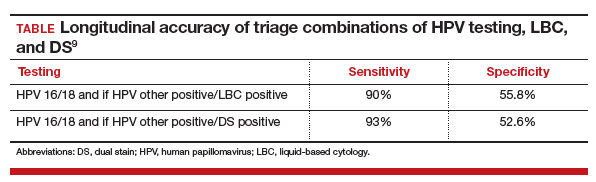

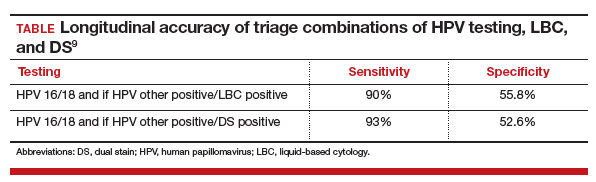

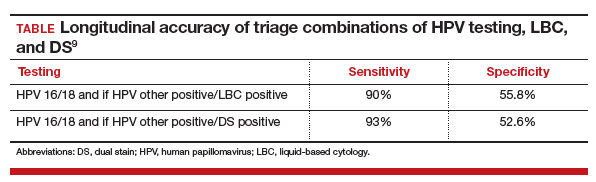

An additional study by Stanczuk and colleagues evaluated triage strategies in a cohort of HR-HPV positive patients who participated in the Scottish Papillomavirus Dumfries and Galloway study with HPV 16/18 genotyping (HPV 16/18), liquid-based cytology (LBC), and p16/Ki-67 DS cytology.9 Of these 3 triage strategies, DS cytology had the highest sensitivity for the detection of CIN 2+, at 77.7% (with a specificity of 74.2%), performance that is arguably better than cytology.

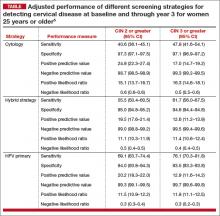

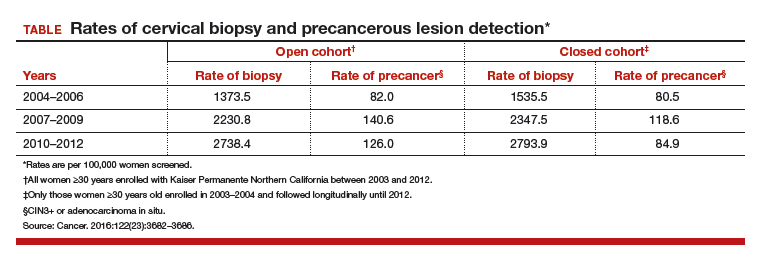

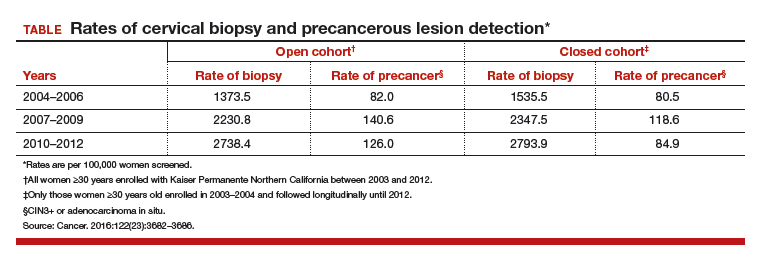

When evaluated in sequence as part of a triage strategy after HPV primary screening, HPV 16/18–positive patients reflexed to DS testing showed a similar sensitivity as those who would be triaged with LBC (TABLE).9

DS testing’s potential

These studies add to the growing body of literature that supports the use of DS testing in cervical cancer screening management guidelines and that are being incorporated into currently existing workflows. Furthermore, with advancements in digital imaging and machine learning, DS testing holds the potential for a high throughput, reproducible, and accurate risk stratification that can replace the current reliance on cytology, furthering the potential for a fully molecular Pap test.10,11

The introduction of p16/Ki-67 dual-stain testing has the potential to allow us to safely move away from a traditional Pap test for cervical cancer screening by allowing for more accurate and reliable identification of high-risk lesions with a molecular test that can be automated and have a high throughput.

Continue to: Cervical cancer screening in women older than age 65: Is there benefit?...

Cervical cancer screening in women older than age 65: Is there benefit?

Firtina Tuncer S, Tuncer HA. Cervical cancer screening in women aged older than 65 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:207-211.

Booth BB, Tranberg M, Gustafson LW, et al. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in women aged ≥ 69 referred to colposcopy due to an HPV-positive screening test. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:405.

Current guidelines in the United States recommend that cervical cancer screening for all persons with a cervix end at age 65. These age restrictions were a change in guidelines updated in 2012 and endorsed by the US Preventive Services Task Force.12,13 Evidence suggests that because of high likelihood of regression and slow progression of disease, risks of screening prior to age 21 outweigh its benefits. With primary HPV testing, the age at screening debut is 25 for the same reasons.14 In people with a history of CIN 2+, active surveillance should continue for at least 25 years with HPV-based screening regardless of age. In the absence of a history of CIN 2+, however, the data to support discontinuation of screening after age 65 are less clear.

HPV positivity found to be most substantial risk for CIN 2+

In a study published this year in the Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, Firtina Tuncer and colleagues described their experience extending “routine screening” in patients older than 65 years.15 Data including cervical cytology, HPV test results, biopsy findings, and endocervical curettage results were collected, and abnormal findings were managed according to the 2012 and 2019 ASCCP guidelines.

When compared with negative HPV testing and normal cytology, the authors found that HPV positivity and abnormal cytology increased the risk of CIN 2+(odds ratio [OR], 136.1 and 13.1, respectively). Patients whose screening prior to age 65 had been insufficient or demonstrated CIN 2+ in the preceding 10 years were similarly more likely to have findings of CIN 2+ (OR, 9.7 when compared with HPV-negative controls).

The authors concluded that, among persons with a cervix older than age 65, previous screening and abnormal cytology were important in risk stratifications for CIN 2+; however, HPV positivity conferred the most substantial risk.

Study finds cervical dysplasia is prevalent in older populations

It has been suggested that screening for cervical cancer should continue beyond age 65 as cytology-based screening may have decreased sensitivity in older patients, which may contribute to the higher rates of advanced-stage diagnoses and cancer-related death in this population.16,17

Authors of an observational study conducted in Denmark invited persons with a cervix aged 69 and older to have one additional HPV-based screening test, and they referred them for colposcopy if HPV positive or in the presence of ASCUS or greater cytology.18 Among the 191 patients with HPV-positive results, 20% were found to have a diagnosis of CIN 2+, and 24.4% had CIN 2+ detected at another point in the study period. Notably, most patients diagnosed with CIN 2+ had no abnormalities visualized on colposcopy, and the majority of biopsies taken (65.8%) did not contain the transitional zone.

Biopsies underestimated CIN 2+ in 17.9% of cases compared with loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). These findings suggest both that high-grade cervical dysplasia is prevalent in an older population and that older populations may be susceptible to false-negative results. They also further support the use of HPV-based screening.

There are risk factors overscreening and underscreening that impact decision making regarding restricting screening to persons with a cervix younger than age 65. As more data become available, and as the population ages, it will be essential to closely examine the incidence of and trends in cervical cancer to determine appropriate patterns of screening.

Harnessing the immune system to improve survival rates in recurrent cervical cancer

Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

Unfortunately, most clinical trials for recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer are negative trials or have results that show limited impact on disease outcomes. Currently, cervical cancer is treated with multiple agents, including platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab, a medication that targets vascular growth. Despite these usually very effective drugs given in combination to cervical cancer patients, long-term survival remains low. Over the past few decades, many trials have been designed to help patients with this terrible disease, but few have shown significant promise.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, have revolutionized care for many cancers. Checkpoint inhibitors block the proteins that cause a tumor to remain undetected by the immune system’s army of T cells. By blocking these proteins, the cancer cells can then be recognized by the immune system as foreign. Several studies have concluded that including immune checkpoint inhibitors in the comprehensive regimen for recurrent cervical cancer improves survival.

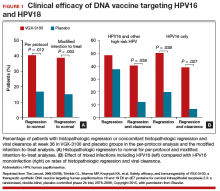

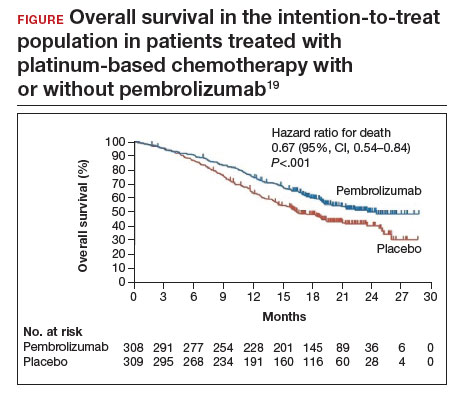

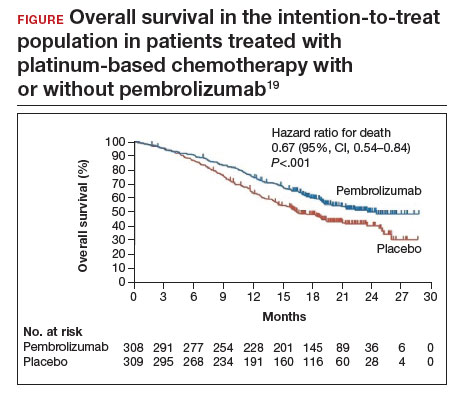

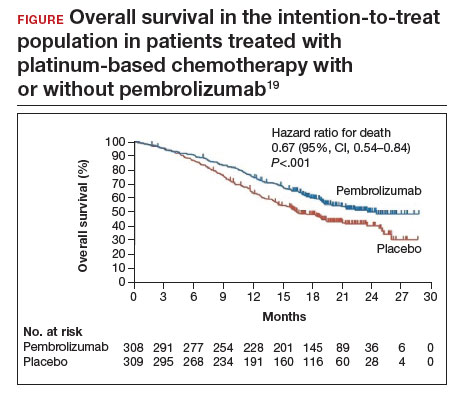

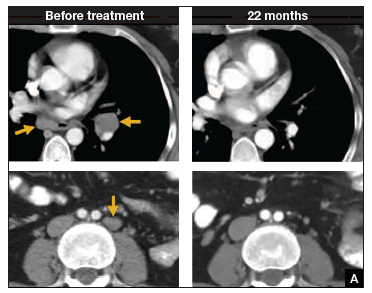

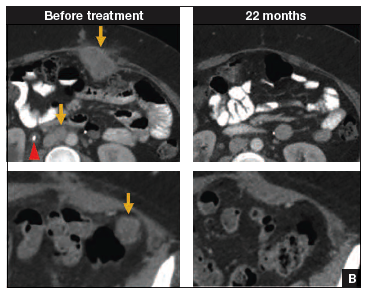

Addition of pembrolizumab increased survival

Investigators in the phase 3 double-blinded KEYNOTE-826 trial evaluated whether or not the addition of pembrolizumab to standard of care improved progression-free and overall survival in advanced, recurrent, or persistent cervical cancer.19 As part of the evaluation, the investigators measured the protein that turns off the immune system’s ability to recognize tumors, anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1).

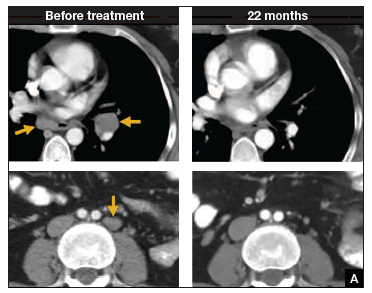

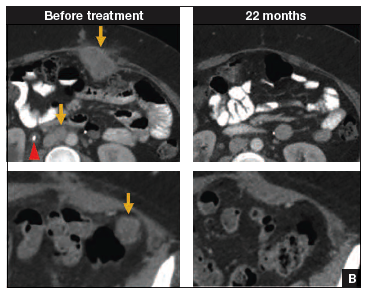

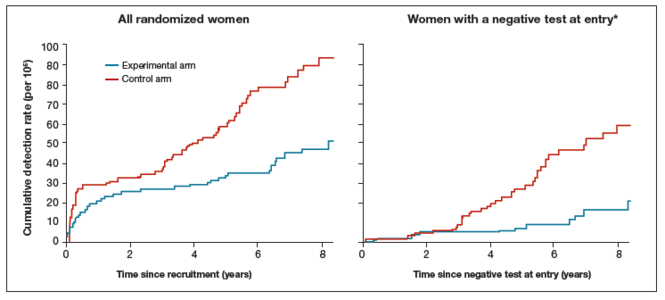

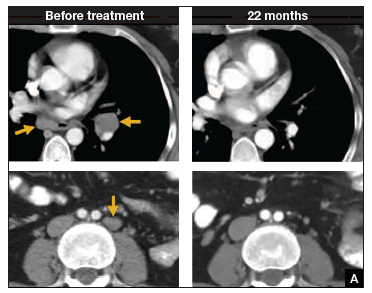

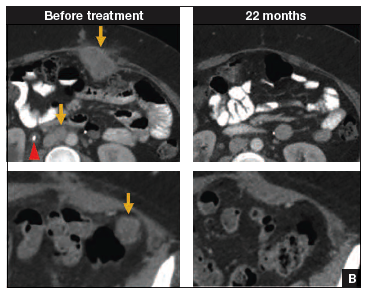

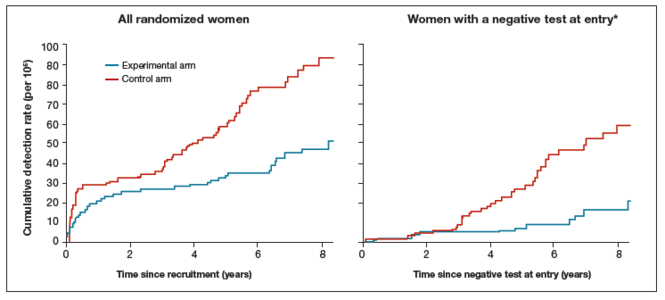

Compared with placebo, the investigators found that, regardless of PD-1 status, the addition of pembrolizumab immunotherapy to the standard regimen increased progression-free survival and overall survival without any significantly increased adverse effects or safety concerns (FIGURE).19 At 1 year after treatment, more patients who received pembrolizumab were still alive regardless of PD-1 status, and their responses lasted longer. The most profound improvements were seen in patients whose tumors exhibited high expression of PD-L1, the target of pembrolizumab and many other immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Despite these promising results, more studies are needed to find additional therapeutic targets and treatments. Using the immune system to fight cancer represents a promising step toward the ultimate goal of cervical cancer eradication. ●

Metastatic cervical cancer can be a devastating disease that cannot be treated surgically and therefore has limited treatment options that have curative intent. Immune checkpoint inhibition via pembrolizumab opens new avenues for treatment and is a huge step forward toward the goal of cervical cancer eradication.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute. June 2023. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/#/Trends/

- Einstein MH, Zhou N, Gabor L, et al. Primary human papillomavirus testing and other new technologies for cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. September 14, 2023. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005393

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2021;70:1183-1190.

- Cervical cancer elimination initiative. World Health Organization. 2023. Accessed October 10, 2023. https ://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-eliminationinitiative#cms

- Downs LS Jr, Nayar R, Gerndt J, et al; American Cancer Society Primary HPV Screening Initiative Steering Committee. Implementation in action: collaborating on the transition to primary HPV screening for cervical cancer in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:458-460.

- Wentzensen N, Fetterman B, Castle PE, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual stain cytology for detection of cervical precancer in HPV-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv257.

- Ikenberg H, Bergeron C, Schmidt D, et al; PALMS Study Group. Screening for cervical cancer precursors with p16 /Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results of the PALMS study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1550-1557.

- Magkana M, Mentzelopoulou P, Magkana E, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual staining is a reliable biomarker for risk stratification for patients with borderline/mild cytology in cervical cancer screening. Anticancer Res. 2022;42:2599-2606.

- Stanczuk G, Currie H, Forson W, et al. Clinical performance of triage strategies for Hr-HPV-positive women; a longitudinal evaluation of cytology, p16/K-67 dual stain cytology, and HPV16/18 genotyping. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1492-1498.

- Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Interlaboratory variation in the performance of liquid-based cytology: insights from the ATHENA trial. Int J Cancer. 2014;134: 1835-1843.

- Wentzensen N, Lahrmann B, Clarke MA, et al. Accuracy and efficiency of deep-learning-based automation of dual stain cytology in cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:72-79.

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:829-846.

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156: 880-891, W312.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

- Firtina Tuncer S, Tuncer HA. Cervical cancer screening in women aged older than 65 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:207-211.

- Hammer A, Hee L, Blaakaer J, et al. Temporal patterns of cervical cancer screening among Danish women 55 years and older diagnosed with cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22:1-7.

- Hammer A, Soegaard V, Maimburg RD, et al. Cervical cancer screening history prior to a diagnosis of cervical cancer in Danish women aged 60 years and older—A national cohort study. Cancer Med. 2019;8:418-427.

- Booth BB, Tranberg M, Gustafson LW, et al. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in women aged ≥ 69 referred to colposcopy due to an HPV-positive screening test. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:405.

- Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

Cervical cancer was the most common cancer killer of persons with a cervix in the early 1900s in the United States. Widespread adoption of the Pap test in the mid-20th century followed by large-scale outreach through programs such as the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program have dramatically reduced deaths from cervical cancer. The development of a highly effective vaccine that targets human papillomavirus (HPV), the virus implicated in all cervical cancers, has made prevention even more accessible and attainable. Primary prevention with HPV vaccination in conjunction with regular screening as recommended by current guidelines is the most effective way we can prevent cervical cancer.

Despite these advances, the incidence and death rates from cervical cancer have plateaued over the last decade.1 Additionally, many fear that due to the poor attendance at screening visits since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence might further rise in the United States.2 Among those in the United States diagnosed with cervical cancer, more than 50% have not been screened in over 5 years or had their abnormal results not managed as recommended by current guidelines, suggesting that operational and access issues are contributors to incident cervical cancer. In addition, HPV vaccination rates have increased only slightly from year to year. According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), coverage with 1 or more doses of HPV vaccine in 2021 increased only by 1.8% and has stagnated, with administration to about 75% of those for whom it is recommended.3 The plateauing will limit our ability to eradicate cervical cancer in the United States, permitting death from a largely preventable disease.

Establishing the framework for the eradication of cervical cancer

The World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a global strategy called the Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative in August 2020. This initiative is a multipronged effort that focuses on vaccination (90% of girls fully vaccinated by age 15), screening (70% of women screened by age 35 with an effective test and again at age 45), and treatment (90% treatment of precancer and 90% management of women with invasive cancer).4

These are the numbers we need to achieve if all countries are to reach a cervical cancer incidence of less than 4 per 100,000 persons with a cervix. The WHO further suggests that each country should meet the “90-70-90” targets by 2030 if we are to achieve the low incidence by the turn of the century.4 To date, few regions of the world have achieved these goals, and sadly the United States is not among them.

In response to this call to action, many medical and policymaking organizations are taking inventory and implementing strategies to achieve the WHO 2030 targets for cervical cancer eradication. In the United States, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO; www.sgo.org), the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP; www.ASCCP.org), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG; www.acog.org), the American Cancer Society (ACS; www.cancer.org), and many others have initiated programs in a collaborative esprit de corps with the aim of eradicating this deadly disease.

In this Update, we review several studies with evidence of screening and management strategies that show promise of accelerating the eradication of cervical cancer.

Continue to: Transitioning to primary HPV screening in the United States...

Transitioning to primary HPV screening in the United States

Downs LS Jr, Nayar R, Gerndt J, et al; American Cancer Society Primary HPV Screening Initiative Steering Committee. Implementation in action: collaborating on the transition to primary HPV screening for cervical cancer in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:458-460.

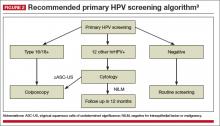

The American Cancer Society released an updated cervical cancer screening guideline in July 2020 that recommended testing for HPV as the preferred strategy. Reasons behind the change, moving away from a Pap test as part of the initial screen, are:

- increased sensitivity of primary HPV testing when compared with conventional cervical cytology (Pap test)

- improved risk stratification to identify who is at risk for cervical cancer now and in the future

- improved efficiency in identifying those who need colposcopy, thus limiting unnecessary procedures without increasing the risk of false-negative tests, thereby missing cervical precancer or invasive cancer.

Some countries with organized screening programs have already made the switch. Self-sampling for HPV is currently being considered for an approved use in the United States, further improving access to screening for cervical cancer when the initial step can be completed by the patient at home or simplified in nontraditional health care settings.2

ACS initiative created to address barriers to primary HPV testing

Challenges to primary HPV testing remain, including laboratory implementation, payment, and operationalizing clinical workflow (for example, HPV testing with reflex cytology instead of cytology with reflex HPV testing).5 There are undoubtedly other unforeseen barriers in the current US health care environment.

In a recent commentary, Downs and colleagues described how the ACS has convened the Primary HPV Screening Initiative (PHSI), nested under the ACS National Roundtable on Cervical Cancer, which is charged with identifying critical barriers to, and opportunities for, transitioning to primary HPV screening.5 The deliverable will be a roadmap with tools and recommendations to support health systems, laboratories, providers, patients, and payers as they make this evolution.

Work groups will develop resources

Patients, particularly those who have had routine cervical cancer screening over their lifetime, also will be curious about the changes in recommendations. The Provider Needs Workgroup within the PHSI structure will develop tools and patient education materials regarding the data, workflow, benefits, and safety of this new paradigm for cervical cancer screening.

Laboratories that process and interpret tests likely will bear the heaviest load of changes. For example, not all commercially available HPV tests in the United States are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary HPV testing. Some sites will need to adapt their equipment to ensure adherence to FDA-approved tests. Laboratory workflows will need to be altered for aliquots to be tested for HPV first, and the remainder for cytology. Quality assurance and accreditation requirements for testing will need modifications, and further efforts will be needed to ensure sufficient numbers of trained cytopathologists, whose workforce is rapidly declining, for processing and reading cervical cytology.

In addition, payment for HPV testing alone, without the need for a Pap test, might not be supported by payers that support safety-net providers and sites, who arguably serve the most vulnerable patients and those most at risk for cervical cancer. Collaboration across medical professionals, societies, payers, and policymakers will provide a critical infrastructure to make the change in the most seamless fashion and limit the harm from missed opportunities for screening.

HPV testing as the primary screen for cervical cancer is now recommended in guidelines due to improved sensitivity and improved efficiency when compared with other methods of screening. Implementation of this new workflow for clinicians and labs will require collaboration across multiple stakeholders.

Continue to: The quest for a “molecular Pap”: Dual-stain testing as a predictor of high-grade CIN...

The quest for a “molecular Pap”: Dual-stain testing as a predictor of high-grade CIN

Magkana M, Mentzelopoulou P, Magkana E, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual staining is a reliable biomarker for risk stratification for patients with borderline/mild cytology in cervical cancer screening. Anticancer Res. 2022;42:2599-2606.

Stanczuk G, Currie H, Forson W, et al. Clinical performance of triage strategies for Hr-HPV-positive women; a longitudinal evaluation of cytology, p16/K-67 dual stain cytology, and HPV16/18 genotyping. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1492-1498.

One new technology that was recently FDA approved and recommended for management of abnormal cervical cancer screening testing is dual-stain (DS) testing. Dual-stain testing is a cytology-based test that evaluates the concurrent expression of p16, a tumor suppressor protein upregulated in HPV oncogenesis, and Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker.6,7 Two recent studies have showcased the outstanding clinical performance of DS testing and triage strategies that incorporate DS testing.

Higher specificity, fewer colposcopies needed with DS testing

Magkana and colleagues prospectively evaluated patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), or negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) cytology referred for colposcopy, and they compared p16/Ki-67 DS testing with high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN 2+); comparable sensitivities for CIN 2+ detection were seen (97.3% and 98.7%, respectively).8

Dual-stain testing exhibited higher specificity at 99.3% compared with HR-HPV testing at 52.2%. Incorporating DS testing into triage strategies also led to fewer colposcopies needed to detect CIN 2+ compared with current ASCCP guidelines that use traditional cervical cancer screening algorithms.

DS cytology strategy had the highest sensitivity for CIN 2+ detection

An additional study by Stanczuk and colleagues evaluated triage strategies in a cohort of HR-HPV positive patients who participated in the Scottish Papillomavirus Dumfries and Galloway study with HPV 16/18 genotyping (HPV 16/18), liquid-based cytology (LBC), and p16/Ki-67 DS cytology.9 Of these 3 triage strategies, DS cytology had the highest sensitivity for the detection of CIN 2+, at 77.7% (with a specificity of 74.2%), performance that is arguably better than cytology.

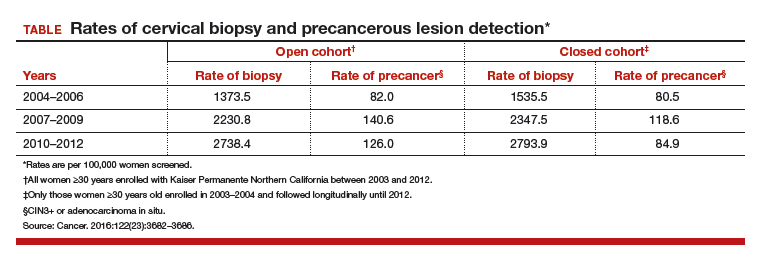

When evaluated in sequence as part of a triage strategy after HPV primary screening, HPV 16/18–positive patients reflexed to DS testing showed a similar sensitivity as those who would be triaged with LBC (TABLE).9

DS testing’s potential

These studies add to the growing body of literature that supports the use of DS testing in cervical cancer screening management guidelines and that are being incorporated into currently existing workflows. Furthermore, with advancements in digital imaging and machine learning, DS testing holds the potential for a high throughput, reproducible, and accurate risk stratification that can replace the current reliance on cytology, furthering the potential for a fully molecular Pap test.10,11

The introduction of p16/Ki-67 dual-stain testing has the potential to allow us to safely move away from a traditional Pap test for cervical cancer screening by allowing for more accurate and reliable identification of high-risk lesions with a molecular test that can be automated and have a high throughput.

Continue to: Cervical cancer screening in women older than age 65: Is there benefit?...

Cervical cancer screening in women older than age 65: Is there benefit?

Firtina Tuncer S, Tuncer HA. Cervical cancer screening in women aged older than 65 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:207-211.

Booth BB, Tranberg M, Gustafson LW, et al. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in women aged ≥ 69 referred to colposcopy due to an HPV-positive screening test. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:405.

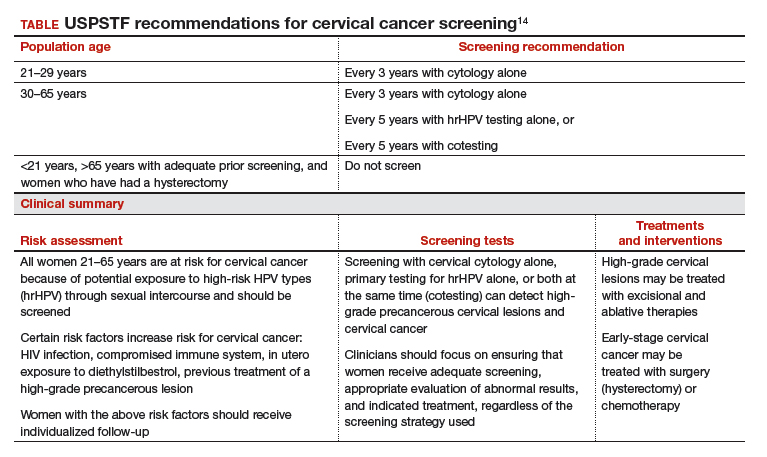

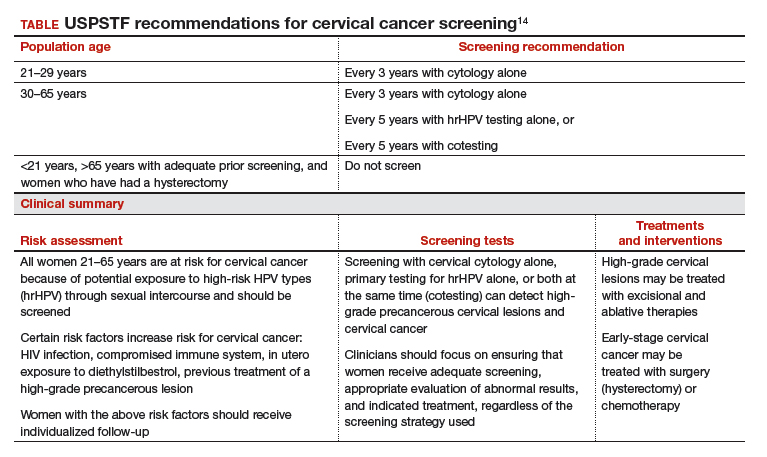

Current guidelines in the United States recommend that cervical cancer screening for all persons with a cervix end at age 65. These age restrictions were a change in guidelines updated in 2012 and endorsed by the US Preventive Services Task Force.12,13 Evidence suggests that because of high likelihood of regression and slow progression of disease, risks of screening prior to age 21 outweigh its benefits. With primary HPV testing, the age at screening debut is 25 for the same reasons.14 In people with a history of CIN 2+, active surveillance should continue for at least 25 years with HPV-based screening regardless of age. In the absence of a history of CIN 2+, however, the data to support discontinuation of screening after age 65 are less clear.

HPV positivity found to be most substantial risk for CIN 2+

In a study published this year in the Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, Firtina Tuncer and colleagues described their experience extending “routine screening” in patients older than 65 years.15 Data including cervical cytology, HPV test results, biopsy findings, and endocervical curettage results were collected, and abnormal findings were managed according to the 2012 and 2019 ASCCP guidelines.

When compared with negative HPV testing and normal cytology, the authors found that HPV positivity and abnormal cytology increased the risk of CIN 2+(odds ratio [OR], 136.1 and 13.1, respectively). Patients whose screening prior to age 65 had been insufficient or demonstrated CIN 2+ in the preceding 10 years were similarly more likely to have findings of CIN 2+ (OR, 9.7 when compared with HPV-negative controls).

The authors concluded that, among persons with a cervix older than age 65, previous screening and abnormal cytology were important in risk stratifications for CIN 2+; however, HPV positivity conferred the most substantial risk.

Study finds cervical dysplasia is prevalent in older populations

It has been suggested that screening for cervical cancer should continue beyond age 65 as cytology-based screening may have decreased sensitivity in older patients, which may contribute to the higher rates of advanced-stage diagnoses and cancer-related death in this population.16,17

Authors of an observational study conducted in Denmark invited persons with a cervix aged 69 and older to have one additional HPV-based screening test, and they referred them for colposcopy if HPV positive or in the presence of ASCUS or greater cytology.18 Among the 191 patients with HPV-positive results, 20% were found to have a diagnosis of CIN 2+, and 24.4% had CIN 2+ detected at another point in the study period. Notably, most patients diagnosed with CIN 2+ had no abnormalities visualized on colposcopy, and the majority of biopsies taken (65.8%) did not contain the transitional zone.

Biopsies underestimated CIN 2+ in 17.9% of cases compared with loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). These findings suggest both that high-grade cervical dysplasia is prevalent in an older population and that older populations may be susceptible to false-negative results. They also further support the use of HPV-based screening.

There are risk factors overscreening and underscreening that impact decision making regarding restricting screening to persons with a cervix younger than age 65. As more data become available, and as the population ages, it will be essential to closely examine the incidence of and trends in cervical cancer to determine appropriate patterns of screening.

Harnessing the immune system to improve survival rates in recurrent cervical cancer

Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

Unfortunately, most clinical trials for recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer are negative trials or have results that show limited impact on disease outcomes. Currently, cervical cancer is treated with multiple agents, including platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab, a medication that targets vascular growth. Despite these usually very effective drugs given in combination to cervical cancer patients, long-term survival remains low. Over the past few decades, many trials have been designed to help patients with this terrible disease, but few have shown significant promise.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, have revolutionized care for many cancers. Checkpoint inhibitors block the proteins that cause a tumor to remain undetected by the immune system’s army of T cells. By blocking these proteins, the cancer cells can then be recognized by the immune system as foreign. Several studies have concluded that including immune checkpoint inhibitors in the comprehensive regimen for recurrent cervical cancer improves survival.

Addition of pembrolizumab increased survival

Investigators in the phase 3 double-blinded KEYNOTE-826 trial evaluated whether or not the addition of pembrolizumab to standard of care improved progression-free and overall survival in advanced, recurrent, or persistent cervical cancer.19 As part of the evaluation, the investigators measured the protein that turns off the immune system’s ability to recognize tumors, anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1).

Compared with placebo, the investigators found that, regardless of PD-1 status, the addition of pembrolizumab immunotherapy to the standard regimen increased progression-free survival and overall survival without any significantly increased adverse effects or safety concerns (FIGURE).19 At 1 year after treatment, more patients who received pembrolizumab were still alive regardless of PD-1 status, and their responses lasted longer. The most profound improvements were seen in patients whose tumors exhibited high expression of PD-L1, the target of pembrolizumab and many other immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Despite these promising results, more studies are needed to find additional therapeutic targets and treatments. Using the immune system to fight cancer represents a promising step toward the ultimate goal of cervical cancer eradication. ●

Metastatic cervical cancer can be a devastating disease that cannot be treated surgically and therefore has limited treatment options that have curative intent. Immune checkpoint inhibition via pembrolizumab opens new avenues for treatment and is a huge step forward toward the goal of cervical cancer eradication.

Cervical cancer was the most common cancer killer of persons with a cervix in the early 1900s in the United States. Widespread adoption of the Pap test in the mid-20th century followed by large-scale outreach through programs such as the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program have dramatically reduced deaths from cervical cancer. The development of a highly effective vaccine that targets human papillomavirus (HPV), the virus implicated in all cervical cancers, has made prevention even more accessible and attainable. Primary prevention with HPV vaccination in conjunction with regular screening as recommended by current guidelines is the most effective way we can prevent cervical cancer.

Despite these advances, the incidence and death rates from cervical cancer have plateaued over the last decade.1 Additionally, many fear that due to the poor attendance at screening visits since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the incidence might further rise in the United States.2 Among those in the United States diagnosed with cervical cancer, more than 50% have not been screened in over 5 years or had their abnormal results not managed as recommended by current guidelines, suggesting that operational and access issues are contributors to incident cervical cancer. In addition, HPV vaccination rates have increased only slightly from year to year. According to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), coverage with 1 or more doses of HPV vaccine in 2021 increased only by 1.8% and has stagnated, with administration to about 75% of those for whom it is recommended.3 The plateauing will limit our ability to eradicate cervical cancer in the United States, permitting death from a largely preventable disease.

Establishing the framework for the eradication of cervical cancer

The World Health Organization (WHO) adopted a global strategy called the Cervical Cancer Elimination Initiative in August 2020. This initiative is a multipronged effort that focuses on vaccination (90% of girls fully vaccinated by age 15), screening (70% of women screened by age 35 with an effective test and again at age 45), and treatment (90% treatment of precancer and 90% management of women with invasive cancer).4

These are the numbers we need to achieve if all countries are to reach a cervical cancer incidence of less than 4 per 100,000 persons with a cervix. The WHO further suggests that each country should meet the “90-70-90” targets by 2030 if we are to achieve the low incidence by the turn of the century.4 To date, few regions of the world have achieved these goals, and sadly the United States is not among them.

In response to this call to action, many medical and policymaking organizations are taking inventory and implementing strategies to achieve the WHO 2030 targets for cervical cancer eradication. In the United States, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO; www.sgo.org), the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP; www.ASCCP.org), the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG; www.acog.org), the American Cancer Society (ACS; www.cancer.org), and many others have initiated programs in a collaborative esprit de corps with the aim of eradicating this deadly disease.

In this Update, we review several studies with evidence of screening and management strategies that show promise of accelerating the eradication of cervical cancer.

Continue to: Transitioning to primary HPV screening in the United States...

Transitioning to primary HPV screening in the United States

Downs LS Jr, Nayar R, Gerndt J, et al; American Cancer Society Primary HPV Screening Initiative Steering Committee. Implementation in action: collaborating on the transition to primary HPV screening for cervical cancer in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:458-460.

The American Cancer Society released an updated cervical cancer screening guideline in July 2020 that recommended testing for HPV as the preferred strategy. Reasons behind the change, moving away from a Pap test as part of the initial screen, are:

- increased sensitivity of primary HPV testing when compared with conventional cervical cytology (Pap test)

- improved risk stratification to identify who is at risk for cervical cancer now and in the future

- improved efficiency in identifying those who need colposcopy, thus limiting unnecessary procedures without increasing the risk of false-negative tests, thereby missing cervical precancer or invasive cancer.

Some countries with organized screening programs have already made the switch. Self-sampling for HPV is currently being considered for an approved use in the United States, further improving access to screening for cervical cancer when the initial step can be completed by the patient at home or simplified in nontraditional health care settings.2

ACS initiative created to address barriers to primary HPV testing

Challenges to primary HPV testing remain, including laboratory implementation, payment, and operationalizing clinical workflow (for example, HPV testing with reflex cytology instead of cytology with reflex HPV testing).5 There are undoubtedly other unforeseen barriers in the current US health care environment.

In a recent commentary, Downs and colleagues described how the ACS has convened the Primary HPV Screening Initiative (PHSI), nested under the ACS National Roundtable on Cervical Cancer, which is charged with identifying critical barriers to, and opportunities for, transitioning to primary HPV screening.5 The deliverable will be a roadmap with tools and recommendations to support health systems, laboratories, providers, patients, and payers as they make this evolution.

Work groups will develop resources

Patients, particularly those who have had routine cervical cancer screening over their lifetime, also will be curious about the changes in recommendations. The Provider Needs Workgroup within the PHSI structure will develop tools and patient education materials regarding the data, workflow, benefits, and safety of this new paradigm for cervical cancer screening.

Laboratories that process and interpret tests likely will bear the heaviest load of changes. For example, not all commercially available HPV tests in the United States are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for primary HPV testing. Some sites will need to adapt their equipment to ensure adherence to FDA-approved tests. Laboratory workflows will need to be altered for aliquots to be tested for HPV first, and the remainder for cytology. Quality assurance and accreditation requirements for testing will need modifications, and further efforts will be needed to ensure sufficient numbers of trained cytopathologists, whose workforce is rapidly declining, for processing and reading cervical cytology.

In addition, payment for HPV testing alone, without the need for a Pap test, might not be supported by payers that support safety-net providers and sites, who arguably serve the most vulnerable patients and those most at risk for cervical cancer. Collaboration across medical professionals, societies, payers, and policymakers will provide a critical infrastructure to make the change in the most seamless fashion and limit the harm from missed opportunities for screening.

HPV testing as the primary screen for cervical cancer is now recommended in guidelines due to improved sensitivity and improved efficiency when compared with other methods of screening. Implementation of this new workflow for clinicians and labs will require collaboration across multiple stakeholders.

Continue to: The quest for a “molecular Pap”: Dual-stain testing as a predictor of high-grade CIN...

The quest for a “molecular Pap”: Dual-stain testing as a predictor of high-grade CIN

Magkana M, Mentzelopoulou P, Magkana E, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual staining is a reliable biomarker for risk stratification for patients with borderline/mild cytology in cervical cancer screening. Anticancer Res. 2022;42:2599-2606.

Stanczuk G, Currie H, Forson W, et al. Clinical performance of triage strategies for Hr-HPV-positive women; a longitudinal evaluation of cytology, p16/K-67 dual stain cytology, and HPV16/18 genotyping. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1492-1498.

One new technology that was recently FDA approved and recommended for management of abnormal cervical cancer screening testing is dual-stain (DS) testing. Dual-stain testing is a cytology-based test that evaluates the concurrent expression of p16, a tumor suppressor protein upregulated in HPV oncogenesis, and Ki-67, a cell proliferation marker.6,7 Two recent studies have showcased the outstanding clinical performance of DS testing and triage strategies that incorporate DS testing.

Higher specificity, fewer colposcopies needed with DS testing

Magkana and colleagues prospectively evaluated patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), or negative for intraepithelial lesion or malignancy (NILM) cytology referred for colposcopy, and they compared p16/Ki-67 DS testing with high-risk HPV (HR-HPV) testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN 2+); comparable sensitivities for CIN 2+ detection were seen (97.3% and 98.7%, respectively).8

Dual-stain testing exhibited higher specificity at 99.3% compared with HR-HPV testing at 52.2%. Incorporating DS testing into triage strategies also led to fewer colposcopies needed to detect CIN 2+ compared with current ASCCP guidelines that use traditional cervical cancer screening algorithms.

DS cytology strategy had the highest sensitivity for CIN 2+ detection

An additional study by Stanczuk and colleagues evaluated triage strategies in a cohort of HR-HPV positive patients who participated in the Scottish Papillomavirus Dumfries and Galloway study with HPV 16/18 genotyping (HPV 16/18), liquid-based cytology (LBC), and p16/Ki-67 DS cytology.9 Of these 3 triage strategies, DS cytology had the highest sensitivity for the detection of CIN 2+, at 77.7% (with a specificity of 74.2%), performance that is arguably better than cytology.

When evaluated in sequence as part of a triage strategy after HPV primary screening, HPV 16/18–positive patients reflexed to DS testing showed a similar sensitivity as those who would be triaged with LBC (TABLE).9

DS testing’s potential

These studies add to the growing body of literature that supports the use of DS testing in cervical cancer screening management guidelines and that are being incorporated into currently existing workflows. Furthermore, with advancements in digital imaging and machine learning, DS testing holds the potential for a high throughput, reproducible, and accurate risk stratification that can replace the current reliance on cytology, furthering the potential for a fully molecular Pap test.10,11

The introduction of p16/Ki-67 dual-stain testing has the potential to allow us to safely move away from a traditional Pap test for cervical cancer screening by allowing for more accurate and reliable identification of high-risk lesions with a molecular test that can be automated and have a high throughput.

Continue to: Cervical cancer screening in women older than age 65: Is there benefit?...

Cervical cancer screening in women older than age 65: Is there benefit?

Firtina Tuncer S, Tuncer HA. Cervical cancer screening in women aged older than 65 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:207-211.

Booth BB, Tranberg M, Gustafson LW, et al. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in women aged ≥ 69 referred to colposcopy due to an HPV-positive screening test. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:405.

Current guidelines in the United States recommend that cervical cancer screening for all persons with a cervix end at age 65. These age restrictions were a change in guidelines updated in 2012 and endorsed by the US Preventive Services Task Force.12,13 Evidence suggests that because of high likelihood of regression and slow progression of disease, risks of screening prior to age 21 outweigh its benefits. With primary HPV testing, the age at screening debut is 25 for the same reasons.14 In people with a history of CIN 2+, active surveillance should continue for at least 25 years with HPV-based screening regardless of age. In the absence of a history of CIN 2+, however, the data to support discontinuation of screening after age 65 are less clear.

HPV positivity found to be most substantial risk for CIN 2+

In a study published this year in the Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease, Firtina Tuncer and colleagues described their experience extending “routine screening” in patients older than 65 years.15 Data including cervical cytology, HPV test results, biopsy findings, and endocervical curettage results were collected, and abnormal findings were managed according to the 2012 and 2019 ASCCP guidelines.

When compared with negative HPV testing and normal cytology, the authors found that HPV positivity and abnormal cytology increased the risk of CIN 2+(odds ratio [OR], 136.1 and 13.1, respectively). Patients whose screening prior to age 65 had been insufficient or demonstrated CIN 2+ in the preceding 10 years were similarly more likely to have findings of CIN 2+ (OR, 9.7 when compared with HPV-negative controls).

The authors concluded that, among persons with a cervix older than age 65, previous screening and abnormal cytology were important in risk stratifications for CIN 2+; however, HPV positivity conferred the most substantial risk.

Study finds cervical dysplasia is prevalent in older populations

It has been suggested that screening for cervical cancer should continue beyond age 65 as cytology-based screening may have decreased sensitivity in older patients, which may contribute to the higher rates of advanced-stage diagnoses and cancer-related death in this population.16,17

Authors of an observational study conducted in Denmark invited persons with a cervix aged 69 and older to have one additional HPV-based screening test, and they referred them for colposcopy if HPV positive or in the presence of ASCUS or greater cytology.18 Among the 191 patients with HPV-positive results, 20% were found to have a diagnosis of CIN 2+, and 24.4% had CIN 2+ detected at another point in the study period. Notably, most patients diagnosed with CIN 2+ had no abnormalities visualized on colposcopy, and the majority of biopsies taken (65.8%) did not contain the transitional zone.

Biopsies underestimated CIN 2+ in 17.9% of cases compared with loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). These findings suggest both that high-grade cervical dysplasia is prevalent in an older population and that older populations may be susceptible to false-negative results. They also further support the use of HPV-based screening.

There are risk factors overscreening and underscreening that impact decision making regarding restricting screening to persons with a cervix younger than age 65. As more data become available, and as the population ages, it will be essential to closely examine the incidence of and trends in cervical cancer to determine appropriate patterns of screening.

Harnessing the immune system to improve survival rates in recurrent cervical cancer

Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

Unfortunately, most clinical trials for recurrent or metastatic cervical cancer are negative trials or have results that show limited impact on disease outcomes. Currently, cervical cancer is treated with multiple agents, including platinum-based chemotherapy and bevacizumab, a medication that targets vascular growth. Despite these usually very effective drugs given in combination to cervical cancer patients, long-term survival remains low. Over the past few decades, many trials have been designed to help patients with this terrible disease, but few have shown significant promise.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as pembrolizumab, have revolutionized care for many cancers. Checkpoint inhibitors block the proteins that cause a tumor to remain undetected by the immune system’s army of T cells. By blocking these proteins, the cancer cells can then be recognized by the immune system as foreign. Several studies have concluded that including immune checkpoint inhibitors in the comprehensive regimen for recurrent cervical cancer improves survival.

Addition of pembrolizumab increased survival

Investigators in the phase 3 double-blinded KEYNOTE-826 trial evaluated whether or not the addition of pembrolizumab to standard of care improved progression-free and overall survival in advanced, recurrent, or persistent cervical cancer.19 As part of the evaluation, the investigators measured the protein that turns off the immune system’s ability to recognize tumors, anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (PD-1).

Compared with placebo, the investigators found that, regardless of PD-1 status, the addition of pembrolizumab immunotherapy to the standard regimen increased progression-free survival and overall survival without any significantly increased adverse effects or safety concerns (FIGURE).19 At 1 year after treatment, more patients who received pembrolizumab were still alive regardless of PD-1 status, and their responses lasted longer. The most profound improvements were seen in patients whose tumors exhibited high expression of PD-L1, the target of pembrolizumab and many other immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Despite these promising results, more studies are needed to find additional therapeutic targets and treatments. Using the immune system to fight cancer represents a promising step toward the ultimate goal of cervical cancer eradication. ●

Metastatic cervical cancer can be a devastating disease that cannot be treated surgically and therefore has limited treatment options that have curative intent. Immune checkpoint inhibition via pembrolizumab opens new avenues for treatment and is a huge step forward toward the goal of cervical cancer eradication.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute. June 2023. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/#/Trends/

- Einstein MH, Zhou N, Gabor L, et al. Primary human papillomavirus testing and other new technologies for cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. September 14, 2023. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005393

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2021;70:1183-1190.

- Cervical cancer elimination initiative. World Health Organization. 2023. Accessed October 10, 2023. https ://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-eliminationinitiative#cms

- Downs LS Jr, Nayar R, Gerndt J, et al; American Cancer Society Primary HPV Screening Initiative Steering Committee. Implementation in action: collaborating on the transition to primary HPV screening for cervical cancer in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:458-460.

- Wentzensen N, Fetterman B, Castle PE, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual stain cytology for detection of cervical precancer in HPV-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv257.

- Ikenberg H, Bergeron C, Schmidt D, et al; PALMS Study Group. Screening for cervical cancer precursors with p16 /Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results of the PALMS study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1550-1557.

- Magkana M, Mentzelopoulou P, Magkana E, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual staining is a reliable biomarker for risk stratification for patients with borderline/mild cytology in cervical cancer screening. Anticancer Res. 2022;42:2599-2606.

- Stanczuk G, Currie H, Forson W, et al. Clinical performance of triage strategies for Hr-HPV-positive women; a longitudinal evaluation of cytology, p16/K-67 dual stain cytology, and HPV16/18 genotyping. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1492-1498.

- Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Interlaboratory variation in the performance of liquid-based cytology: insights from the ATHENA trial. Int J Cancer. 2014;134: 1835-1843.

- Wentzensen N, Lahrmann B, Clarke MA, et al. Accuracy and efficiency of deep-learning-based automation of dual stain cytology in cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:72-79.

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:829-846.

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156: 880-891, W312.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

- Firtina Tuncer S, Tuncer HA. Cervical cancer screening in women aged older than 65 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:207-211.

- Hammer A, Hee L, Blaakaer J, et al. Temporal patterns of cervical cancer screening among Danish women 55 years and older diagnosed with cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22:1-7.

- Hammer A, Soegaard V, Maimburg RD, et al. Cervical cancer screening history prior to a diagnosis of cervical cancer in Danish women aged 60 years and older—A national cohort study. Cancer Med. 2019;8:418-427.

- Booth BB, Tranberg M, Gustafson LW, et al. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in women aged ≥ 69 referred to colposcopy due to an HPV-positive screening test. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:405.

- Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US Cancer Statistics Data Visualizations Tool, based on 2022 submission data (1999-2020). US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Cancer Institute. June 2023. Accessed October 9, 2023. https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/#/Trends/

- Einstein MH, Zhou N, Gabor L, et al. Primary human papillomavirus testing and other new technologies for cervical cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. September 14, 2023. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000005393

- Pingali C, Yankey D, Elam-Evans LD, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2020. MMWR Morbid Mortal Weekly Rep. 2021;70:1183-1190.

- Cervical cancer elimination initiative. World Health Organization. 2023. Accessed October 10, 2023. https ://www.who.int/initiatives/cervical-cancer-eliminationinitiative#cms

- Downs LS Jr, Nayar R, Gerndt J, et al; American Cancer Society Primary HPV Screening Initiative Steering Committee. Implementation in action: collaborating on the transition to primary HPV screening for cervical cancer in the United States. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73:458-460.

- Wentzensen N, Fetterman B, Castle PE, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual stain cytology for detection of cervical precancer in HPV-positive women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:djv257.

- Ikenberg H, Bergeron C, Schmidt D, et al; PALMS Study Group. Screening for cervical cancer precursors with p16 /Ki-67 dual-stained cytology: results of the PALMS study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:1550-1557.

- Magkana M, Mentzelopoulou P, Magkana E, et al. p16/Ki-67 Dual staining is a reliable biomarker for risk stratification for patients with borderline/mild cytology in cervical cancer screening. Anticancer Res. 2022;42:2599-2606.

- Stanczuk G, Currie H, Forson W, et al. Clinical performance of triage strategies for Hr-HPV-positive women; a longitudinal evaluation of cytology, p16/K-67 dual stain cytology, and HPV16/18 genotyping. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022;31:1492-1498.

- Wright TC Jr, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, et al. Interlaboratory variation in the performance of liquid-based cytology: insights from the ATHENA trial. Int J Cancer. 2014;134: 1835-1843.

- Wentzensen N, Lahrmann B, Clarke MA, et al. Accuracy and efficiency of deep-learning-based automation of dual stain cytology in cervical cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2021;113:72-79.

- Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121:829-846.

- Moyer VA; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156: 880-891, W312.

- Fontham ETH, Wolf AMD, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

- Firtina Tuncer S, Tuncer HA. Cervical cancer screening in women aged older than 65 years. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2023;27:207-211.

- Hammer A, Hee L, Blaakaer J, et al. Temporal patterns of cervical cancer screening among Danish women 55 years and older diagnosed with cervical cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2018;22:1-7.

- Hammer A, Soegaard V, Maimburg RD, et al. Cervical cancer screening history prior to a diagnosis of cervical cancer in Danish women aged 60 years and older—A national cohort study. Cancer Med. 2019;8:418-427.

- Booth BB, Tranberg M, Gustafson LW, et al. Risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse in women aged ≥ 69 referred to colposcopy due to an HPV-positive screening test. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:405.

- Colombo N, Dubot C, Lorusso D, et al; KEYNOTE-826 Investigators. Pembrolizumab for persistent, recurrent, or metastatic cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1856-1867.

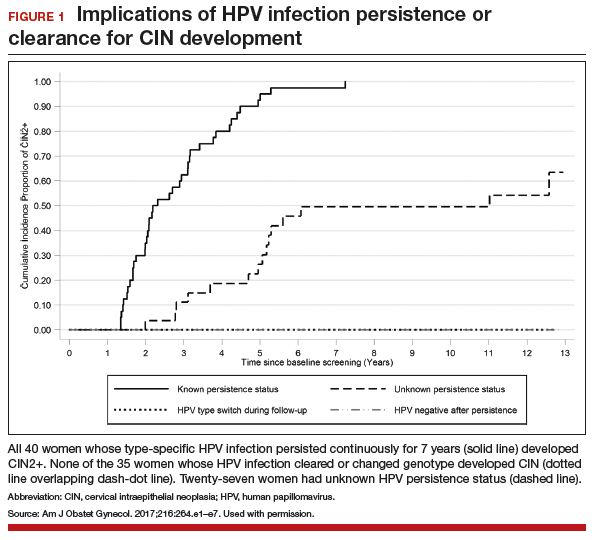

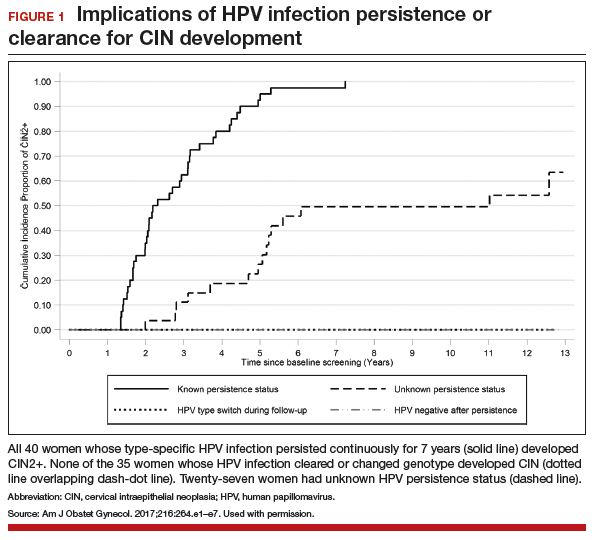

2019 Update on cervical disease

Cervical cancer rates remain low in the United States, with the incidence having plateaued for decades. And yet, in 2019, more than 13,000 US women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer.1 Globally, in 2018 almost 600,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer2; it is the fourth most frequent cancer in women. This is despite the fact that we have adequate primary and secondary prevention tools available to minimize—and almost eliminate—cervical cancer. We must continue to raise the bar for preventing, screening for, and managing this disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines provide a highly effective primary prevention strategy, but we need to improve our ability to identify and diagnose dysplastic lesions prior to the development of cervical cancer. Highly sensitive HPV testing and cytology is a powerful secondary prevention approach that enables us to assess a woman’s risk of having precancerous cells both now and in the near future. These modalities have been very successful in decreasing the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States and other areas with organized screening programs. In low- and middle-income countries, however, access to, availability of, and performance with these modalities is not optimal. Innovative strategies and new technologies are being evaluated to overcome these limitations.

Advances in radiation and surgical technology have enabled us to vastly improve cervical cancer treatment. Women with early-stage cervical cancer are candidates for surgical management, which frequently includes a radical hysterectomy and lymph node dissection. While these surgeries traditionally have been performed via an exploratory laparotomy, minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical techniques) have decreased the morbidity with these surgeries. Notable new studies have shed light on the comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive technologies and have shown us that new is not always better.

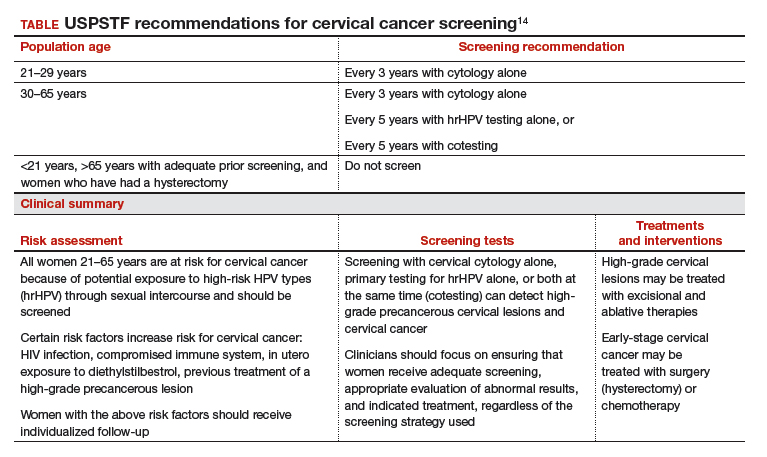

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released its updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. The suggested approach to screening differs from previous recommendations. HPV testing as a primary test (that is, HPV testing alone or followed by cytology) takes the spotlight now, according to the analysis by the Task Force.

In this Update, we highlight important studies published in the past year that address these issues.

Continue to: New tech's potential to identify high-grade...

New tech's potential to identify high-grade cervical dysplasia may be a boon to low-resource settings

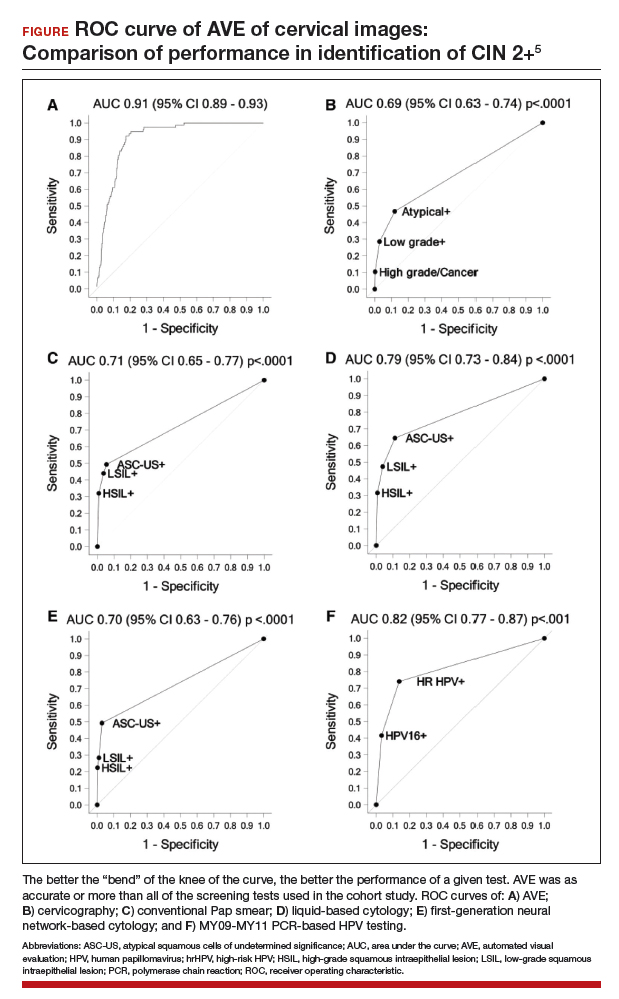

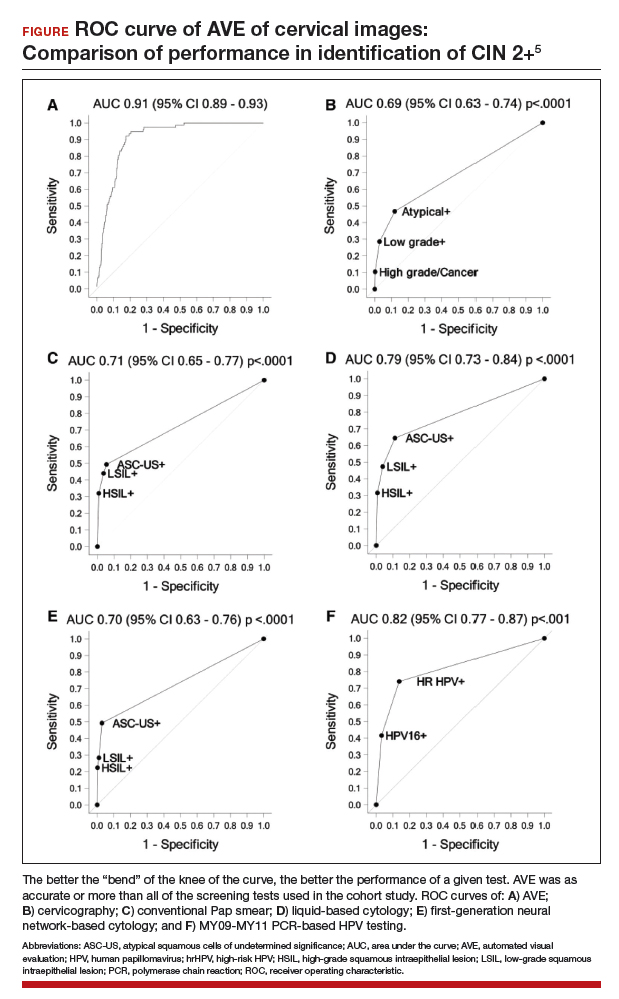

Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

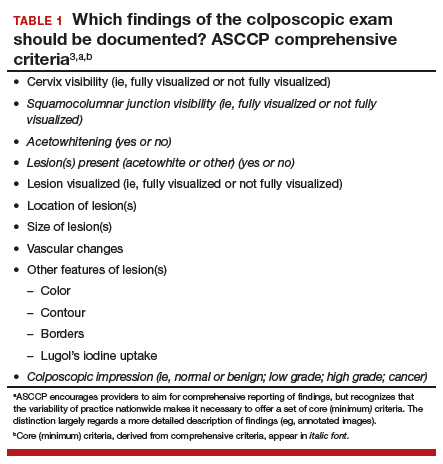

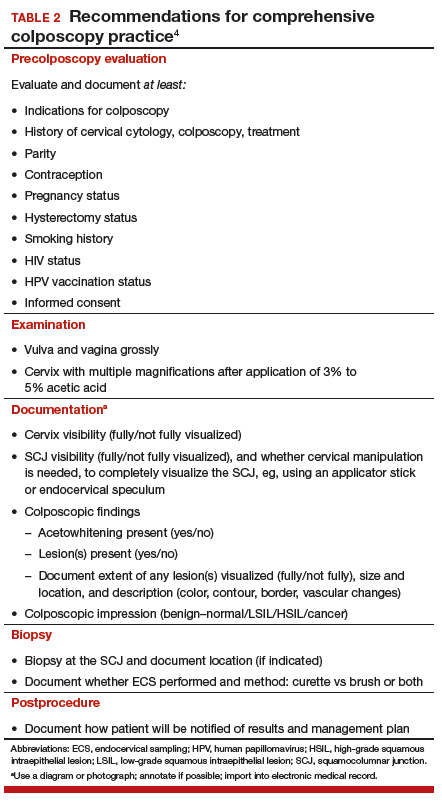

When cervical screening tests like cytology and HPV testing show abnormal results, colposcopy often is recommended. The goal of colposcopy is to identify the areas that might harbor a high-grade precancerous lesion or worse. The gold standard in this case, however, is histology, not colposcopic impression, as many studies have shown that colposcopy without biopsies is limited and that performance is improved with more biopsies.3,4

Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is an approach used often in low-resource settings where visual impression is the gold standard. However, as with colposcopy, a visual evaluation without histology does not perform well, and often women are overtreated. Many attempts have been made with new technologies to overcome the limitations of time, cost, and workforce required for cytology and histology services. New disruptive technologies may be able to surmount human limitations and improve on not only VIA but also the need for histology.

Novel technology uses images to develop algorithm with predictive ability

In a recent observational study, Hu and colleagues used images that were collected during a large population study in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.5 More than 9,000 women were followed for up to 7 years, and cervical photographs (cervigrams) were obtained. Well-annotated histopathology results were obtained for women with abnormal screening, and 279 women had a high-grade dysplastic lesion or cancer.

Cervigrams from women with high-grade lesions and matched controls were collected, and a deep learning-based algorithm using artificial intelligence technology was developed using 70% of the images. The remaining 30% of images were used as a validation set to test the algorithm's ability to "predict" high-grade dysplasia without knowing the final result.

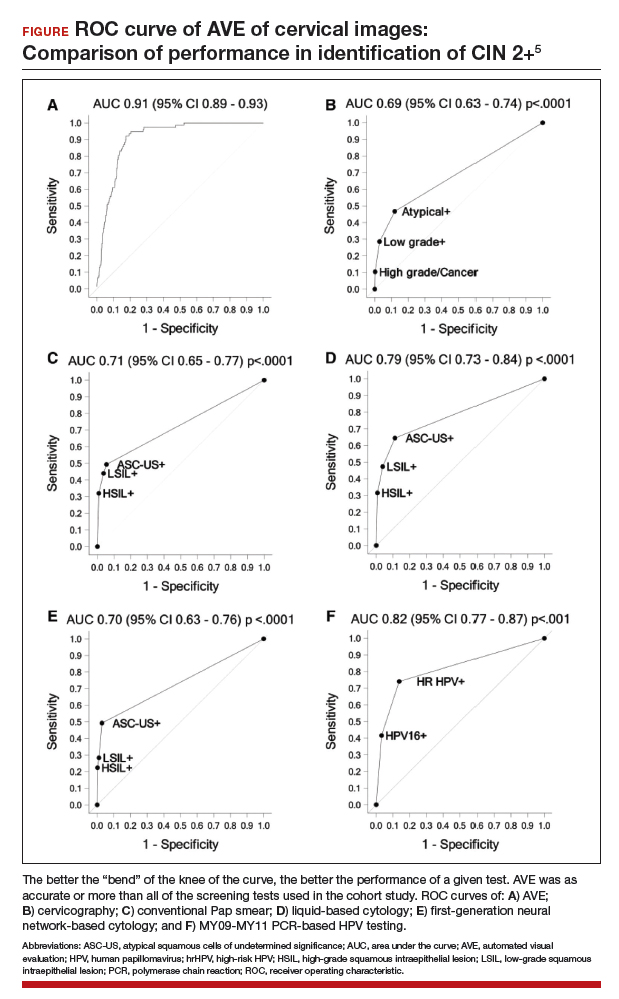

Findings. Termed automated visual evaluation (AVE), this new technology demonstrated a very accurate ability to identify high-grade dysplasia or worse, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 from merely a cervicogram (FIGURE). This outperformed conventional Pap smears (AUC, 0.71), liquid-based cytology (AUC, 0.79) and, surprisingly, highly sensitive HPV testing (AUC, 0.82) in women in the prime of their screening ages (>25 years of age).

Colposcopy remains the gold standard for evaluating abnormal cervical cancer screening tests in the United States. But can we do better for our patients using new technologies like AVE? If validated in large-scale trials, AVE has the potential to revolutionize cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings where follow-up and adequate histology services are limited or nonexistent. Future large studies are necessary to evaluate the role of AVE alone versus in combination with other diagnostic testing (such as HPV testing) to detect cervical lesions globally.

Continue to: Data offer persuasive evidence...

Data offer persuasive evidence to abandon minimally invasive surgery in management of early-stage cervical cancer

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Over the past decade, gynecologic cancer surgery has shifted from what routinely were open procedures to the adoption of minimally invasive techniques. Recently, a large, well-designed prospective study and a large retrospective study both demonstrated worse outcomes with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH) as compared with traditional open radical abdominal hysterectomy (RAH). These 2 landmark studies, initially presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology's 2018 annual meeting and later published in the New England Journal of Medicine, have really affected the gynecologic oncology community.

Shorter overall survival in women who had MIRH

Melamed and colleagues conducted a large, retrospective US-based study to evaluate all-cause mortality in women with cervical cancer who underwent MIRH compared with those who had RAH.6 The authors also sought to evaluate national trends in 4-year relative survival rates after minimally invasive surgery was adopted.

The study included 2,461 women who met the inclusion criteria; 49.8% (1,225) underwent MIRH procedures and, of those, 79.8% (978) had robot-assisted laparoscopy. Most women had stage IB1 tumors (88%), and most carcinomas were squamous cell (61%); 40.6% of tumors were less than 2 cm in size. There were no differences between the 2 groups with respect to rates of positive parametria, surgical margins, and lymph node involvement. Administration of adjuvant therapy, in those who qualified, was also similar between groups.

Results. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 94 deaths occurred in the minimally invasive group and 70 in the open surgery group. The risk of death at 4 years was 9.1% in the minimally invasive group versus 5.3% in the open surgery group, with a 65% higher risk of death from any cause, which was highly statistically significant.

Prospective trial showed MIRH was associated with lower survival rates

From 2008 to 2017, Ramirez and colleagues conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to prospectively establish the noninferiority of MIRH compared with RAH.7 The study included 631 women from 33 centers. The prespecified expected disease-free survival rate was 90% at 4.5 years.

To be included as a site, centers were required to submit details from 10 minimally invasive cases as well as 2 unedited videos for review by the trial management committee. In contrast to Melamed and colleagues' retrospective study, of the 319 procedures that were classified as minimally invasive, only 15.6% were robotically assisted. Similarly, most women had stage IB1 tumors (91.9%), and most were squamous cell carcinomas (67%). There were also no differences in the postoperative pathology findings or the need for adjuvant therapy administered between groups. The median follow-up was 2.5 years.

Results. At that time there were 27 recurrences in the MIRH group and 7 in the RAH group; there were also 19 deaths after MIRH and 3 after RAH. Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with MIRH versus 96.5% with RAH. Reported 3-year disease-free survival and overall survival were also significantily lower in the minimally invasive subgroup (91.2% vs 97.1%, 93.8% vs 99.0%, respectively).

Study limitations. Criticisms of this trial are that noninferiority could not be declared; in addition, the investigators were unable to complete enrollment secondary to early enrollment termination after the data and safety monitoring board raised survival concerns.

Many argue that subgroup analyses suggest a lower risk of poor outcomes in patients with smaller tumors (<2 cm); however, it is critical to note that this study was not powered to detect these differences.

The evidence is compelling and demonstrates potentially worse disease-related outcomes using MIRH when compared to traditional RAH with respect to cervical cancer recurrence, rates of death, and disease-free and overall survival. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and future research is needed to elucidate the differences in variables responsible for the outcomes demonstrated in these studies. Although there has been no ban on robot-assisted surgical devices or traditional minimally invasive techniques, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated its recommendations to include careful counseling of patients who require a surgical approach for the management of early-stage cervical cancer.

Continue to: USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening...

USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening

Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

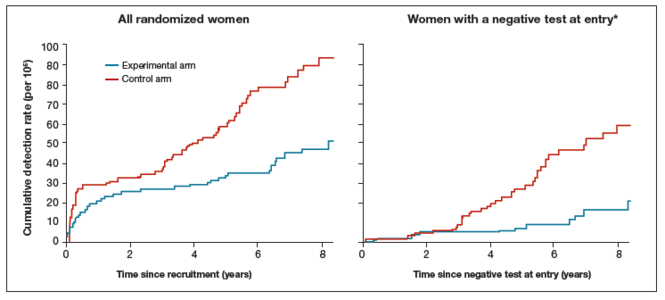

Past guidelines for cervical cancer screening have included testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) as a cotest with cytology or for triage of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) in women aged 30 to 65 years.8 The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, with other stakeholder organizations, issued interim guidance for primary HPV testing--that is, HPV test first and, in the case of non-16/18 hrHPV types, cytology as a triage. The most recent evidence report and systematic review by Melnikow and colleagues for the USPSTF offers an in-depth analysis of risks, benefits, harms, and value of cotesting and other management strategies.9

Focus on screening effectiveness