User login

Two very recent significant advances in cervical disease prevention and screening make this an exciting time for women’s health clinicians. One development, the 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, offers the potential to increase overall prevention of cervical cancer to over 90%. The other advance offers clinicians a cervical cancer screening alternative, HPV DNA testing, for primary cervical cancer screening. In this article, I underscore the data behind, as well as expert guidance on, these two important developments.

The 9-valent HPV vaccine expands HPV-type coverage and vaccine options for routine use

Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen O, et al. A 9-valent vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711–723.

Two HPV types, 16 and 18, cause the majority—about 70%—of cervical cancers. Vaccination against these types, as well as against types 6 and 11 that cause most condyloma, has been available in the United States since 2006, when the quadrivalent vaccine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Now, based on the results of Joura and colleagues’ randomized, double-blind phase 2b−3 study involving more than 14,000 women, the 9-valent vaccine (Gardasil 9, Merck, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) has been recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) as 1 of 3 HPV vaccines that can be used for routine vaccination.1 (The other 2 vaccines include the bivalent [Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina] and quadrivalent [Gardasil, Merck]).

Compared with quadrivalent, does the 9-valent vaccine offer compelling additional protection?

The incidence rate of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN; ≥CIN 2 or adenocarcinoma in situ) related to the additional HPV types covered with the 9-valent vaccine (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) was 0.1 per 1,000 person-years in the 9-valent group and 1.6 per 1,000 person-years in the quadrivalent group. This is equivalent to 1 case versus 30 cases of disease and translates to 96.7% efficacy (95% confidence interval [CI], 80.9−99.8) against these 5 additional high-risk HPV types. At 36 months, there was 1 case of high-grade cervical disease in the 9-valent group related to the 5 additional HPV types, compared with 20 cumulative cases in the quadrivalent group. At 48 months, there was 1 case in the 9-valent group and 27 cases in the quadrivalent group (FIGURE 1).

This expanded disease coverage means the vaccine has the potential to prevent an additional 15% to 20% of cervical cancers in addition to the potential to prevent 5% to 20% of other HPV-related cancers.3

The added HPV-type protection resulted in more frequent injection site reactions (90.7% in the 9-valent group vs 84.9% in the quadrivalent group). Pain, erythema, and pruritis were the most common reactions. While rare, events of severe intensity were more common in the 9-valent group. However, less than 0.1% of participants discontinued study vaccination because of a vaccine-related adverse event.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This was a well-designed prospective, randomized controlled trial. Follow-up was limited; however, this is typical for a clinical trial, and extended follow-up analyses have held up in other HPV vaccine trials; I don’t anticipate it will be any different in this case. The control arm in the case of this trial was the quadrivalent vaccine, as that is the routinely recommended vaccine, so it is not ethical to give placebo in this age-range population. The placebo study already was published,4 so Joura and colleagues’ results build on prior findings.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In a widely vaccinated population, the 9-valent HPV vaccine has the potential to protect against an additional 20% of cervical cancers, compared with the quadrivalent vaccine. This is an important improvement in HPV infection and cervical disease prevention. Unfortunately, in the United States we still have very low coverage for the first dose of the HPV vaccine, and even lower coverage for the recommended 3-dose series. This is a big problem in the United States. Stakeholders and advocates need to figure out innovative ways to overcome the challenges of full vaccination for the patients in whom it’s routinely recommended—11- and 12-year-old girls and boys. HPV vaccination lags behind coverage for other vaccines recommended in this same age group—by 20% to 25%.3 US HPV vaccination rates are woefully low in comparison with such other countries as Australia, much of western Europe, and the UK. “If teenagers were offered and accepted HPV vaccination every time they received another vaccine, first-dose coverage for HPV would exceed 90%.”3

The ACIP recommends routine vaccination for HPV—with the bivalent, quadrivalent, or 9-valent vaccine—at age 11 or 12 years. They also recommend vaccination for females aged 13 through 26 years and males aged 13 through 21 years who have not been vaccinated previously. Vaccination is also recommended through age 26 years for men who have sex with men and for immunocompromised persons (including those with HIV infection) if not vaccinated previously.1

By the time I retire, I hope that the impact of protection against additional HPV infection types will be felt, with HPV vaccination rates improved and fewer women affected by the morbidity and mortality related to cervical cancer. As ObGyns, we want to do right by our patients; we need to embrace and continue to discuss the message of primary protection with vaccines that protect against HPV in order to overcome the mixed rhetoric patients and parents receive from other groups, including sensational media or political figureheads who might have an alternative agenda that is clearly not in the best interest of our patients.

HPV test alone is as effective as Pap plus HPV test for cervical disease screening

Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

The cobas (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, California) HPV DNA test received FDA approval as a primary screening test for cervical cancer in women aged 25 and older in April 2015. This is a big paradigm shift from what has long been the way we screen women, starting with cytology. Simplistically, the thinking is that we start with the more sensitive test to enrich the population of women that might need additional testing, which might include cytology.

The FDA considered these end-of-study data by Wright and colleagues, which had not been publically published at the time, in its decision. With the Addressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) 3-year prospective study, these investigators sought to address major unresolved issues related to HPV primary screening, such as determining which HPV-positive women should be referred to colposcopy and how HPV primary screening performs in the United States. Such a strategy long has been shown to be effective in large prospective European trials.

Details of the study

Three screening strategies were tested:

- Cytology: HPV testing performed only for atypical cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US).

- Hybrid: Cytology strategy for women aged 25 to 29 and cotesting with both cytology and HPV (pooled 14 genotypes) for women 30 years or older. This strategy mimics current preferred US screening recommendations. With cotesting, HPV-positive women with negative cytology are retested with both tests in 1 year and undergo colposcopy if either test is abnormal.

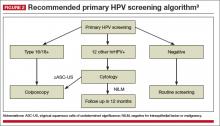

- HPV primary: HPV-negative women rescreened in 3 years, HPV16/18-positive women receive immediate colposcopy, women positive for the other 12 HPV types receive reflex cytology with colposcopy if the cytology is ASC-US or worse. If cytology results are negative, women are rescreened with HPV and cytology in 1 year.

In all strategies, women who were referred to colposcopy and found not to have CIN 2 or greater were rescreened with both tests in 1 year and referred to colposcopy if the finding was ASC-US or higher-grade or persistently HPV-positive.

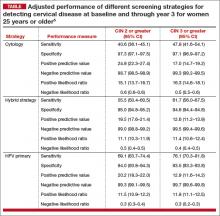

Of the 3 screening strategies, HPV primary in women 25 years and older had the highest adjusted sensitivity over 3 years (76.1%; 95% CI, 70.3–81.8) for the detection of CIN 3 or greater, with similar specificity as the cytology and hybrid strategies. In addition, the negative predictive value for not having clinically relevant disease for HPV primary was comparable to or better than the other 2 strategies (TABLE).5

Another important finding was that the number of colposcopies required to detect 1 case of cervical disease, although found to be significantly higher, was comparable for the HPV primary and cytology strategies (7.1 [95% CI, 6.4–8.0] for cytology vs 8.0 for HPV primary for CIN 2 or greater in women 25 years and older). For CIN 3 or greater, the number of colposcopies required to detect 1 case was 12.8 (95% CI, 11.7–14.5) for HPV primary versus 12.9 (95% CI, 11.5–14.8) for hybrid and 10.8 (95% CI, 9.4–12.6) for cytology.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

These data indicate that HPV primary screening in women aged 25 and older is as effective as a hybrid screening strategy that uses cytology and cotesting in a patient older than 30 years. And HPV primary screening requires fewer overall screening tests to identify women who have clinically significant cervical disease.

Importantly, compared with a cytology-based strategy, the negative predictive value is quite high for HPV primary screening. Therefore, if someone has a negative HPV test result, the likelihood of that person actually having some sort of clinically relevant disease that day or in the next 3 years is incredibly low. And this is really what’s important for our patients who are getting screened for cervical cancer.

Interim guidelines support use of HPV testing alone or with the Pap smear

Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

The most recent set of consensus guidelines for managing abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors is the American Cancer Society/American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)/American Society for Clinical Pathology 2012 guidelines,6 which recommend cotesting as the preferred strategy in women aged 30 to 65 years. However, to address increasing evidence that HPV testing alone is an effective primary screening approach and how clinicians should adopt these findings in their practice, an expert panel convened to offer interim guidance. The panel was cosponsored and funded by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) and ASCCP and included 13 experts representing 7 societies, including SGO, ASCCP, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. This guidance can be adopted as an alternative to the updated 2012 recommendations until the next consensus guidelines panel convenes.

The panel considered a number of questions related to primary HPV testing and overall advantages and disadvantages of this strategy for screening.

Is HPV testing (for high-risk HPV [hrHPV] types) for primary screening as safe and effective as cytology-based screening?

The panel’s answer: Yes. A negative hrHPV test provides greater reassurance of low CIN 3 or greater risk than a negative cytology result. Because of its equivalent, or even superior, effectiveness—which has been demonstrated in the ATHENA study and several European randomized controlled screening trials7,8—primary hrHPV screening can be considered as an alternative to current US cervical cancer screening methods.

A reasonable approach to managing a positive hrHPV result, advises the panel, is to triage hrHPV-positive women using a combination of genotyping for HPV 16 and 18 and reflex cytology for women positive for the 12 other hrHPV genotypes

(FIGURE 2).9

What is the optimal age to begin primary hrHPV screening?

The panel’s clinical guidance is not before age 25. This is a gray area right now, however, as there are concerns regarding the potential harm of screening at age 25 despite the increased detection of disease, particularly with regard to the number of colposcopies that could be performed in this age group due to the high incidence of HPV infection in young women. So the ideal age at which to begin hrHPV screening will need further discussion in future consensus guideline panels.

What is the optimal interval for primary hrHPV screening?

Prospective follow-up in the ATHENA study was restricted to 3 years. The panel advises that rescreening after a negative primary hrHPV screen should occur no sooner than every 3 years.

Outstanding considerations

The changeover from primary cytology to primary HPV testing represents a very different workflow for clinicians and laboratories. It also represents a different mode of screening for our patients, so patient education is essential. Many questions and concerns still need to be considered, for instance:

- There are no real comparative effectiveness data for the number of screening tests that are needed for an HPV primary screening program, including the number of colposcopies.

- There needs to be further discussion about the optimal age to begin primary HPV screening and the appropriate interval for rescreening patients who are HPV-negative.

- There are questions about the sampling from patients, such as specimen adequacy, internal controls, and the impact of other interfering substances in a large screening program.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

A move to the HPV test for primary screening represents a paradigm shift for clinicians and patients. Such a shift likely will be slow to occur, due to changes in clinical and laboratory workflow, provider and patient education, and systems issues. Also, there are a number of questions that still need to be answered. Primary hrHPV screening at age 25 to 29 years may lead to increased CIN 3 detection, but the impact of the increased number of colposcopies, integration for those women who already have been screened prior to age 25, and actual impact on cancer prevention need further investigation, the panel points out.

However, primary HPV screening can be considered as an alternative to current US cytology-based cervical cancer screening approaches. Over time, use of primary HPV screening appears to make screening more precise and efficient as it will minimize the number of abnormal cytology results that we would consider cytomorphologic manifestations of an active HPV infection that are not clinically relevant.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2015;62(11):300−304.

2. Joura EA, Giuliano O, Iversen C, et al, for the Broad Spectrum HPV Vaccine Study. A 9-valent vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711−723.

3. Schuchat A. HPV “coverage.” N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8): 775−776.

4. Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al; Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) I Investigators. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1928−1943.

5. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

6. Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 suppl 1):S1–S27.

7. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, Tunesi S, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M, et al. Efficacy of HPV based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):524–532.

8. Dillner J, ReboljM, Birembaut P, et al. Long-term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study [published online ahead of print October 13, 2008]. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1754.

9. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

Two very recent significant advances in cervical disease prevention and screening make this an exciting time for women’s health clinicians. One development, the 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, offers the potential to increase overall prevention of cervical cancer to over 90%. The other advance offers clinicians a cervical cancer screening alternative, HPV DNA testing, for primary cervical cancer screening. In this article, I underscore the data behind, as well as expert guidance on, these two important developments.

The 9-valent HPV vaccine expands HPV-type coverage and vaccine options for routine use

Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen O, et al. A 9-valent vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711–723.

Two HPV types, 16 and 18, cause the majority—about 70%—of cervical cancers. Vaccination against these types, as well as against types 6 and 11 that cause most condyloma, has been available in the United States since 2006, when the quadrivalent vaccine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Now, based on the results of Joura and colleagues’ randomized, double-blind phase 2b−3 study involving more than 14,000 women, the 9-valent vaccine (Gardasil 9, Merck, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) has been recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) as 1 of 3 HPV vaccines that can be used for routine vaccination.1 (The other 2 vaccines include the bivalent [Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina] and quadrivalent [Gardasil, Merck]).

Compared with quadrivalent, does the 9-valent vaccine offer compelling additional protection?

The incidence rate of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN; ≥CIN 2 or adenocarcinoma in situ) related to the additional HPV types covered with the 9-valent vaccine (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) was 0.1 per 1,000 person-years in the 9-valent group and 1.6 per 1,000 person-years in the quadrivalent group. This is equivalent to 1 case versus 30 cases of disease and translates to 96.7% efficacy (95% confidence interval [CI], 80.9−99.8) against these 5 additional high-risk HPV types. At 36 months, there was 1 case of high-grade cervical disease in the 9-valent group related to the 5 additional HPV types, compared with 20 cumulative cases in the quadrivalent group. At 48 months, there was 1 case in the 9-valent group and 27 cases in the quadrivalent group (FIGURE 1).

This expanded disease coverage means the vaccine has the potential to prevent an additional 15% to 20% of cervical cancers in addition to the potential to prevent 5% to 20% of other HPV-related cancers.3

The added HPV-type protection resulted in more frequent injection site reactions (90.7% in the 9-valent group vs 84.9% in the quadrivalent group). Pain, erythema, and pruritis were the most common reactions. While rare, events of severe intensity were more common in the 9-valent group. However, less than 0.1% of participants discontinued study vaccination because of a vaccine-related adverse event.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This was a well-designed prospective, randomized controlled trial. Follow-up was limited; however, this is typical for a clinical trial, and extended follow-up analyses have held up in other HPV vaccine trials; I don’t anticipate it will be any different in this case. The control arm in the case of this trial was the quadrivalent vaccine, as that is the routinely recommended vaccine, so it is not ethical to give placebo in this age-range population. The placebo study already was published,4 so Joura and colleagues’ results build on prior findings.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In a widely vaccinated population, the 9-valent HPV vaccine has the potential to protect against an additional 20% of cervical cancers, compared with the quadrivalent vaccine. This is an important improvement in HPV infection and cervical disease prevention. Unfortunately, in the United States we still have very low coverage for the first dose of the HPV vaccine, and even lower coverage for the recommended 3-dose series. This is a big problem in the United States. Stakeholders and advocates need to figure out innovative ways to overcome the challenges of full vaccination for the patients in whom it’s routinely recommended—11- and 12-year-old girls and boys. HPV vaccination lags behind coverage for other vaccines recommended in this same age group—by 20% to 25%.3 US HPV vaccination rates are woefully low in comparison with such other countries as Australia, much of western Europe, and the UK. “If teenagers were offered and accepted HPV vaccination every time they received another vaccine, first-dose coverage for HPV would exceed 90%.”3

The ACIP recommends routine vaccination for HPV—with the bivalent, quadrivalent, or 9-valent vaccine—at age 11 or 12 years. They also recommend vaccination for females aged 13 through 26 years and males aged 13 through 21 years who have not been vaccinated previously. Vaccination is also recommended through age 26 years for men who have sex with men and for immunocompromised persons (including those with HIV infection) if not vaccinated previously.1

By the time I retire, I hope that the impact of protection against additional HPV infection types will be felt, with HPV vaccination rates improved and fewer women affected by the morbidity and mortality related to cervical cancer. As ObGyns, we want to do right by our patients; we need to embrace and continue to discuss the message of primary protection with vaccines that protect against HPV in order to overcome the mixed rhetoric patients and parents receive from other groups, including sensational media or political figureheads who might have an alternative agenda that is clearly not in the best interest of our patients.

HPV test alone is as effective as Pap plus HPV test for cervical disease screening

Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

The cobas (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, California) HPV DNA test received FDA approval as a primary screening test for cervical cancer in women aged 25 and older in April 2015. This is a big paradigm shift from what has long been the way we screen women, starting with cytology. Simplistically, the thinking is that we start with the more sensitive test to enrich the population of women that might need additional testing, which might include cytology.

The FDA considered these end-of-study data by Wright and colleagues, which had not been publically published at the time, in its decision. With the Addressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) 3-year prospective study, these investigators sought to address major unresolved issues related to HPV primary screening, such as determining which HPV-positive women should be referred to colposcopy and how HPV primary screening performs in the United States. Such a strategy long has been shown to be effective in large prospective European trials.

Details of the study

Three screening strategies were tested:

- Cytology: HPV testing performed only for atypical cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US).

- Hybrid: Cytology strategy for women aged 25 to 29 and cotesting with both cytology and HPV (pooled 14 genotypes) for women 30 years or older. This strategy mimics current preferred US screening recommendations. With cotesting, HPV-positive women with negative cytology are retested with both tests in 1 year and undergo colposcopy if either test is abnormal.

- HPV primary: HPV-negative women rescreened in 3 years, HPV16/18-positive women receive immediate colposcopy, women positive for the other 12 HPV types receive reflex cytology with colposcopy if the cytology is ASC-US or worse. If cytology results are negative, women are rescreened with HPV and cytology in 1 year.

In all strategies, women who were referred to colposcopy and found not to have CIN 2 or greater were rescreened with both tests in 1 year and referred to colposcopy if the finding was ASC-US or higher-grade or persistently HPV-positive.

Of the 3 screening strategies, HPV primary in women 25 years and older had the highest adjusted sensitivity over 3 years (76.1%; 95% CI, 70.3–81.8) for the detection of CIN 3 or greater, with similar specificity as the cytology and hybrid strategies. In addition, the negative predictive value for not having clinically relevant disease for HPV primary was comparable to or better than the other 2 strategies (TABLE).5

Another important finding was that the number of colposcopies required to detect 1 case of cervical disease, although found to be significantly higher, was comparable for the HPV primary and cytology strategies (7.1 [95% CI, 6.4–8.0] for cytology vs 8.0 for HPV primary for CIN 2 or greater in women 25 years and older). For CIN 3 or greater, the number of colposcopies required to detect 1 case was 12.8 (95% CI, 11.7–14.5) for HPV primary versus 12.9 (95% CI, 11.5–14.8) for hybrid and 10.8 (95% CI, 9.4–12.6) for cytology.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

These data indicate that HPV primary screening in women aged 25 and older is as effective as a hybrid screening strategy that uses cytology and cotesting in a patient older than 30 years. And HPV primary screening requires fewer overall screening tests to identify women who have clinically significant cervical disease.

Importantly, compared with a cytology-based strategy, the negative predictive value is quite high for HPV primary screening. Therefore, if someone has a negative HPV test result, the likelihood of that person actually having some sort of clinically relevant disease that day or in the next 3 years is incredibly low. And this is really what’s important for our patients who are getting screened for cervical cancer.

Interim guidelines support use of HPV testing alone or with the Pap smear

Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

The most recent set of consensus guidelines for managing abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors is the American Cancer Society/American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)/American Society for Clinical Pathology 2012 guidelines,6 which recommend cotesting as the preferred strategy in women aged 30 to 65 years. However, to address increasing evidence that HPV testing alone is an effective primary screening approach and how clinicians should adopt these findings in their practice, an expert panel convened to offer interim guidance. The panel was cosponsored and funded by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) and ASCCP and included 13 experts representing 7 societies, including SGO, ASCCP, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. This guidance can be adopted as an alternative to the updated 2012 recommendations until the next consensus guidelines panel convenes.

The panel considered a number of questions related to primary HPV testing and overall advantages and disadvantages of this strategy for screening.

Is HPV testing (for high-risk HPV [hrHPV] types) for primary screening as safe and effective as cytology-based screening?

The panel’s answer: Yes. A negative hrHPV test provides greater reassurance of low CIN 3 or greater risk than a negative cytology result. Because of its equivalent, or even superior, effectiveness—which has been demonstrated in the ATHENA study and several European randomized controlled screening trials7,8—primary hrHPV screening can be considered as an alternative to current US cervical cancer screening methods.

A reasonable approach to managing a positive hrHPV result, advises the panel, is to triage hrHPV-positive women using a combination of genotyping for HPV 16 and 18 and reflex cytology for women positive for the 12 other hrHPV genotypes

(FIGURE 2).9

What is the optimal age to begin primary hrHPV screening?

The panel’s clinical guidance is not before age 25. This is a gray area right now, however, as there are concerns regarding the potential harm of screening at age 25 despite the increased detection of disease, particularly with regard to the number of colposcopies that could be performed in this age group due to the high incidence of HPV infection in young women. So the ideal age at which to begin hrHPV screening will need further discussion in future consensus guideline panels.

What is the optimal interval for primary hrHPV screening?

Prospective follow-up in the ATHENA study was restricted to 3 years. The panel advises that rescreening after a negative primary hrHPV screen should occur no sooner than every 3 years.

Outstanding considerations

The changeover from primary cytology to primary HPV testing represents a very different workflow for clinicians and laboratories. It also represents a different mode of screening for our patients, so patient education is essential. Many questions and concerns still need to be considered, for instance:

- There are no real comparative effectiveness data for the number of screening tests that are needed for an HPV primary screening program, including the number of colposcopies.

- There needs to be further discussion about the optimal age to begin primary HPV screening and the appropriate interval for rescreening patients who are HPV-negative.

- There are questions about the sampling from patients, such as specimen adequacy, internal controls, and the impact of other interfering substances in a large screening program.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

A move to the HPV test for primary screening represents a paradigm shift for clinicians and patients. Such a shift likely will be slow to occur, due to changes in clinical and laboratory workflow, provider and patient education, and systems issues. Also, there are a number of questions that still need to be answered. Primary hrHPV screening at age 25 to 29 years may lead to increased CIN 3 detection, but the impact of the increased number of colposcopies, integration for those women who already have been screened prior to age 25, and actual impact on cancer prevention need further investigation, the panel points out.

However, primary HPV screening can be considered as an alternative to current US cytology-based cervical cancer screening approaches. Over time, use of primary HPV screening appears to make screening more precise and efficient as it will minimize the number of abnormal cytology results that we would consider cytomorphologic manifestations of an active HPV infection that are not clinically relevant.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Two very recent significant advances in cervical disease prevention and screening make this an exciting time for women’s health clinicians. One development, the 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine, offers the potential to increase overall prevention of cervical cancer to over 90%. The other advance offers clinicians a cervical cancer screening alternative, HPV DNA testing, for primary cervical cancer screening. In this article, I underscore the data behind, as well as expert guidance on, these two important developments.

The 9-valent HPV vaccine expands HPV-type coverage and vaccine options for routine use

Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen O, et al. A 9-valent vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711–723.

Two HPV types, 16 and 18, cause the majority—about 70%—of cervical cancers. Vaccination against these types, as well as against types 6 and 11 that cause most condyloma, has been available in the United States since 2006, when the quadrivalent vaccine was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA).1 Now, based on the results of Joura and colleagues’ randomized, double-blind phase 2b−3 study involving more than 14,000 women, the 9-valent vaccine (Gardasil 9, Merck, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) has been recommended by the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) as 1 of 3 HPV vaccines that can be used for routine vaccination.1 (The other 2 vaccines include the bivalent [Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina] and quadrivalent [Gardasil, Merck]).

Compared with quadrivalent, does the 9-valent vaccine offer compelling additional protection?

The incidence rate of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN; ≥CIN 2 or adenocarcinoma in situ) related to the additional HPV types covered with the 9-valent vaccine (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58) was 0.1 per 1,000 person-years in the 9-valent group and 1.6 per 1,000 person-years in the quadrivalent group. This is equivalent to 1 case versus 30 cases of disease and translates to 96.7% efficacy (95% confidence interval [CI], 80.9−99.8) against these 5 additional high-risk HPV types. At 36 months, there was 1 case of high-grade cervical disease in the 9-valent group related to the 5 additional HPV types, compared with 20 cumulative cases in the quadrivalent group. At 48 months, there was 1 case in the 9-valent group and 27 cases in the quadrivalent group (FIGURE 1).

This expanded disease coverage means the vaccine has the potential to prevent an additional 15% to 20% of cervical cancers in addition to the potential to prevent 5% to 20% of other HPV-related cancers.3

The added HPV-type protection resulted in more frequent injection site reactions (90.7% in the 9-valent group vs 84.9% in the quadrivalent group). Pain, erythema, and pruritis were the most common reactions. While rare, events of severe intensity were more common in the 9-valent group. However, less than 0.1% of participants discontinued study vaccination because of a vaccine-related adverse event.

Study strengths and weaknesses

This was a well-designed prospective, randomized controlled trial. Follow-up was limited; however, this is typical for a clinical trial, and extended follow-up analyses have held up in other HPV vaccine trials; I don’t anticipate it will be any different in this case. The control arm in the case of this trial was the quadrivalent vaccine, as that is the routinely recommended vaccine, so it is not ethical to give placebo in this age-range population. The placebo study already was published,4 so Joura and colleagues’ results build on prior findings.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

In a widely vaccinated population, the 9-valent HPV vaccine has the potential to protect against an additional 20% of cervical cancers, compared with the quadrivalent vaccine. This is an important improvement in HPV infection and cervical disease prevention. Unfortunately, in the United States we still have very low coverage for the first dose of the HPV vaccine, and even lower coverage for the recommended 3-dose series. This is a big problem in the United States. Stakeholders and advocates need to figure out innovative ways to overcome the challenges of full vaccination for the patients in whom it’s routinely recommended—11- and 12-year-old girls and boys. HPV vaccination lags behind coverage for other vaccines recommended in this same age group—by 20% to 25%.3 US HPV vaccination rates are woefully low in comparison with such other countries as Australia, much of western Europe, and the UK. “If teenagers were offered and accepted HPV vaccination every time they received another vaccine, first-dose coverage for HPV would exceed 90%.”3

The ACIP recommends routine vaccination for HPV—with the bivalent, quadrivalent, or 9-valent vaccine—at age 11 or 12 years. They also recommend vaccination for females aged 13 through 26 years and males aged 13 through 21 years who have not been vaccinated previously. Vaccination is also recommended through age 26 years for men who have sex with men and for immunocompromised persons (including those with HIV infection) if not vaccinated previously.1

By the time I retire, I hope that the impact of protection against additional HPV infection types will be felt, with HPV vaccination rates improved and fewer women affected by the morbidity and mortality related to cervical cancer. As ObGyns, we want to do right by our patients; we need to embrace and continue to discuss the message of primary protection with vaccines that protect against HPV in order to overcome the mixed rhetoric patients and parents receive from other groups, including sensational media or political figureheads who might have an alternative agenda that is clearly not in the best interest of our patients.

HPV test alone is as effective as Pap plus HPV test for cervical disease screening

Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

The cobas (Roche Molecular Diagnostics, Pleasanton, California) HPV DNA test received FDA approval as a primary screening test for cervical cancer in women aged 25 and older in April 2015. This is a big paradigm shift from what has long been the way we screen women, starting with cytology. Simplistically, the thinking is that we start with the more sensitive test to enrich the population of women that might need additional testing, which might include cytology.

The FDA considered these end-of-study data by Wright and colleagues, which had not been publically published at the time, in its decision. With the Addressing the Need for Advanced HPV Diagnostics (ATHENA) 3-year prospective study, these investigators sought to address major unresolved issues related to HPV primary screening, such as determining which HPV-positive women should be referred to colposcopy and how HPV primary screening performs in the United States. Such a strategy long has been shown to be effective in large prospective European trials.

Details of the study

Three screening strategies were tested:

- Cytology: HPV testing performed only for atypical cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US).

- Hybrid: Cytology strategy for women aged 25 to 29 and cotesting with both cytology and HPV (pooled 14 genotypes) for women 30 years or older. This strategy mimics current preferred US screening recommendations. With cotesting, HPV-positive women with negative cytology are retested with both tests in 1 year and undergo colposcopy if either test is abnormal.

- HPV primary: HPV-negative women rescreened in 3 years, HPV16/18-positive women receive immediate colposcopy, women positive for the other 12 HPV types receive reflex cytology with colposcopy if the cytology is ASC-US or worse. If cytology results are negative, women are rescreened with HPV and cytology in 1 year.

In all strategies, women who were referred to colposcopy and found not to have CIN 2 or greater were rescreened with both tests in 1 year and referred to colposcopy if the finding was ASC-US or higher-grade or persistently HPV-positive.

Of the 3 screening strategies, HPV primary in women 25 years and older had the highest adjusted sensitivity over 3 years (76.1%; 95% CI, 70.3–81.8) for the detection of CIN 3 or greater, with similar specificity as the cytology and hybrid strategies. In addition, the negative predictive value for not having clinically relevant disease for HPV primary was comparable to or better than the other 2 strategies (TABLE).5

Another important finding was that the number of colposcopies required to detect 1 case of cervical disease, although found to be significantly higher, was comparable for the HPV primary and cytology strategies (7.1 [95% CI, 6.4–8.0] for cytology vs 8.0 for HPV primary for CIN 2 or greater in women 25 years and older). For CIN 3 or greater, the number of colposcopies required to detect 1 case was 12.8 (95% CI, 11.7–14.5) for HPV primary versus 12.9 (95% CI, 11.5–14.8) for hybrid and 10.8 (95% CI, 9.4–12.6) for cytology.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

These data indicate that HPV primary screening in women aged 25 and older is as effective as a hybrid screening strategy that uses cytology and cotesting in a patient older than 30 years. And HPV primary screening requires fewer overall screening tests to identify women who have clinically significant cervical disease.

Importantly, compared with a cytology-based strategy, the negative predictive value is quite high for HPV primary screening. Therefore, if someone has a negative HPV test result, the likelihood of that person actually having some sort of clinically relevant disease that day or in the next 3 years is incredibly low. And this is really what’s important for our patients who are getting screened for cervical cancer.

Interim guidelines support use of HPV testing alone or with the Pap smear

Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

The most recent set of consensus guidelines for managing abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors is the American Cancer Society/American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP)/American Society for Clinical Pathology 2012 guidelines,6 which recommend cotesting as the preferred strategy in women aged 30 to 65 years. However, to address increasing evidence that HPV testing alone is an effective primary screening approach and how clinicians should adopt these findings in their practice, an expert panel convened to offer interim guidance. The panel was cosponsored and funded by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) and ASCCP and included 13 experts representing 7 societies, including SGO, ASCCP, and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. This guidance can be adopted as an alternative to the updated 2012 recommendations until the next consensus guidelines panel convenes.

The panel considered a number of questions related to primary HPV testing and overall advantages and disadvantages of this strategy for screening.

Is HPV testing (for high-risk HPV [hrHPV] types) for primary screening as safe and effective as cytology-based screening?

The panel’s answer: Yes. A negative hrHPV test provides greater reassurance of low CIN 3 or greater risk than a negative cytology result. Because of its equivalent, or even superior, effectiveness—which has been demonstrated in the ATHENA study and several European randomized controlled screening trials7,8—primary hrHPV screening can be considered as an alternative to current US cervical cancer screening methods.

A reasonable approach to managing a positive hrHPV result, advises the panel, is to triage hrHPV-positive women using a combination of genotyping for HPV 16 and 18 and reflex cytology for women positive for the 12 other hrHPV genotypes

(FIGURE 2).9

What is the optimal age to begin primary hrHPV screening?

The panel’s clinical guidance is not before age 25. This is a gray area right now, however, as there are concerns regarding the potential harm of screening at age 25 despite the increased detection of disease, particularly with regard to the number of colposcopies that could be performed in this age group due to the high incidence of HPV infection in young women. So the ideal age at which to begin hrHPV screening will need further discussion in future consensus guideline panels.

What is the optimal interval for primary hrHPV screening?

Prospective follow-up in the ATHENA study was restricted to 3 years. The panel advises that rescreening after a negative primary hrHPV screen should occur no sooner than every 3 years.

Outstanding considerations

The changeover from primary cytology to primary HPV testing represents a very different workflow for clinicians and laboratories. It also represents a different mode of screening for our patients, so patient education is essential. Many questions and concerns still need to be considered, for instance:

- There are no real comparative effectiveness data for the number of screening tests that are needed for an HPV primary screening program, including the number of colposcopies.

- There needs to be further discussion about the optimal age to begin primary HPV screening and the appropriate interval for rescreening patients who are HPV-negative.

- There are questions about the sampling from patients, such as specimen adequacy, internal controls, and the impact of other interfering substances in a large screening program.

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

A move to the HPV test for primary screening represents a paradigm shift for clinicians and patients. Such a shift likely will be slow to occur, due to changes in clinical and laboratory workflow, provider and patient education, and systems issues. Also, there are a number of questions that still need to be answered. Primary hrHPV screening at age 25 to 29 years may lead to increased CIN 3 detection, but the impact of the increased number of colposcopies, integration for those women who already have been screened prior to age 25, and actual impact on cancer prevention need further investigation, the panel points out.

However, primary HPV screening can be considered as an alternative to current US cytology-based cervical cancer screening approaches. Over time, use of primary HPV screening appears to make screening more precise and efficient as it will minimize the number of abnormal cytology results that we would consider cytomorphologic manifestations of an active HPV infection that are not clinically relevant.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2015;62(11):300−304.

2. Joura EA, Giuliano O, Iversen C, et al, for the Broad Spectrum HPV Vaccine Study. A 9-valent vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711−723.

3. Schuchat A. HPV “coverage.” N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8): 775−776.

4. Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al; Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) I Investigators. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1928−1943.

5. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

6. Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 suppl 1):S1–S27.

7. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, Tunesi S, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M, et al. Efficacy of HPV based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):524–532.

8. Dillner J, ReboljM, Birembaut P, et al. Long-term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study [published online ahead of print October 13, 2008]. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1754.

9. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

1. Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-valent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. 2015;62(11):300−304.

2. Joura EA, Giuliano O, Iversen C, et al, for the Broad Spectrum HPV Vaccine Study. A 9-valent vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711−723.

3. Schuchat A. HPV “coverage.” N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8): 775−776.

4. Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al; Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) I Investigators. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1928−1943.

5. Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

6. Massad LS, Einstein MH, Huh WK, et al; 2012 ASCCP Consensus Guidelines Conference. 2012 updated consensus guidelines for the management of abnormal cervical cancer screening tests and cancer precursors. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17(5 suppl 1):S1–S27.

7. Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfström KM, Tunesi S, Snijders PJ, Arbyn M, et al. Efficacy of HPV based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):524–532.

8. Dillner J, ReboljM, Birembaut P, et al. Long-term predictive values of cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cervical cancer screening: joint European cohort study [published online ahead of print October 13, 2008]. BMJ. 2008;337:a1754. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1754.

9. Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

In this article

- Disease progression with 9-valent versus quadrivalent HPV vaccine

- How well do current screening strategies detect disease?

- Recommended primary HPV screening algorithm