User login

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) intended that women have access to critical preventive health services without a copay or deductible. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was asked to help identify those critical preventive women’s health services. In 2011, the IOM Committee on Preventive Services for Women recommended that all women have access to 9 preventive services, among them1:

- screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

- human papilloma virus testing

- contraceptive methods and counseling

- well-woman visits.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services agreed to update the recommended preventive services every 5 years.

In March 2016, HRSA entered into a 5-year cooperative agreement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update the guidelines and to develop additional recommendations to enhance women’s health.2 ACOG launched the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) to develop the 2016 update.

The 5-year grant with HRSA will address many more preventive health services for women across their lifespan as well as implementation strategies so that women receive consistent and appropriate care, regardless of the health care provider’s specialty. The WPSI recognizes that the selection of a provider for well-woman care will be determined as much by a woman’s needs and preferences as by her access to health care services and health plan availability.

The WPSI draft recommendations were released for public comment in September 2016,2 and HRSA approved the recommendations in December 2016.3 In this editorial, I provide a look at which organizations comprise the WPSI and a summary of the 9 recommended preventive health services.

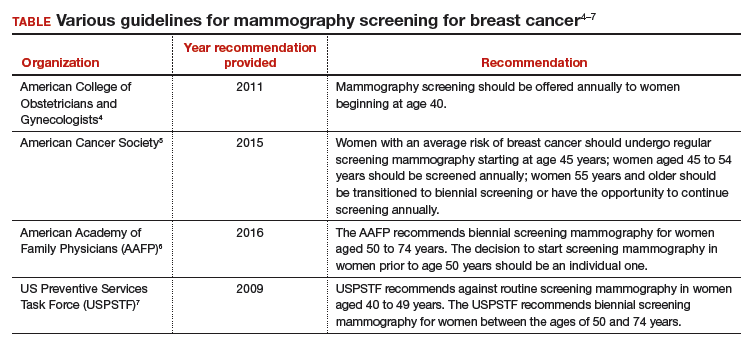

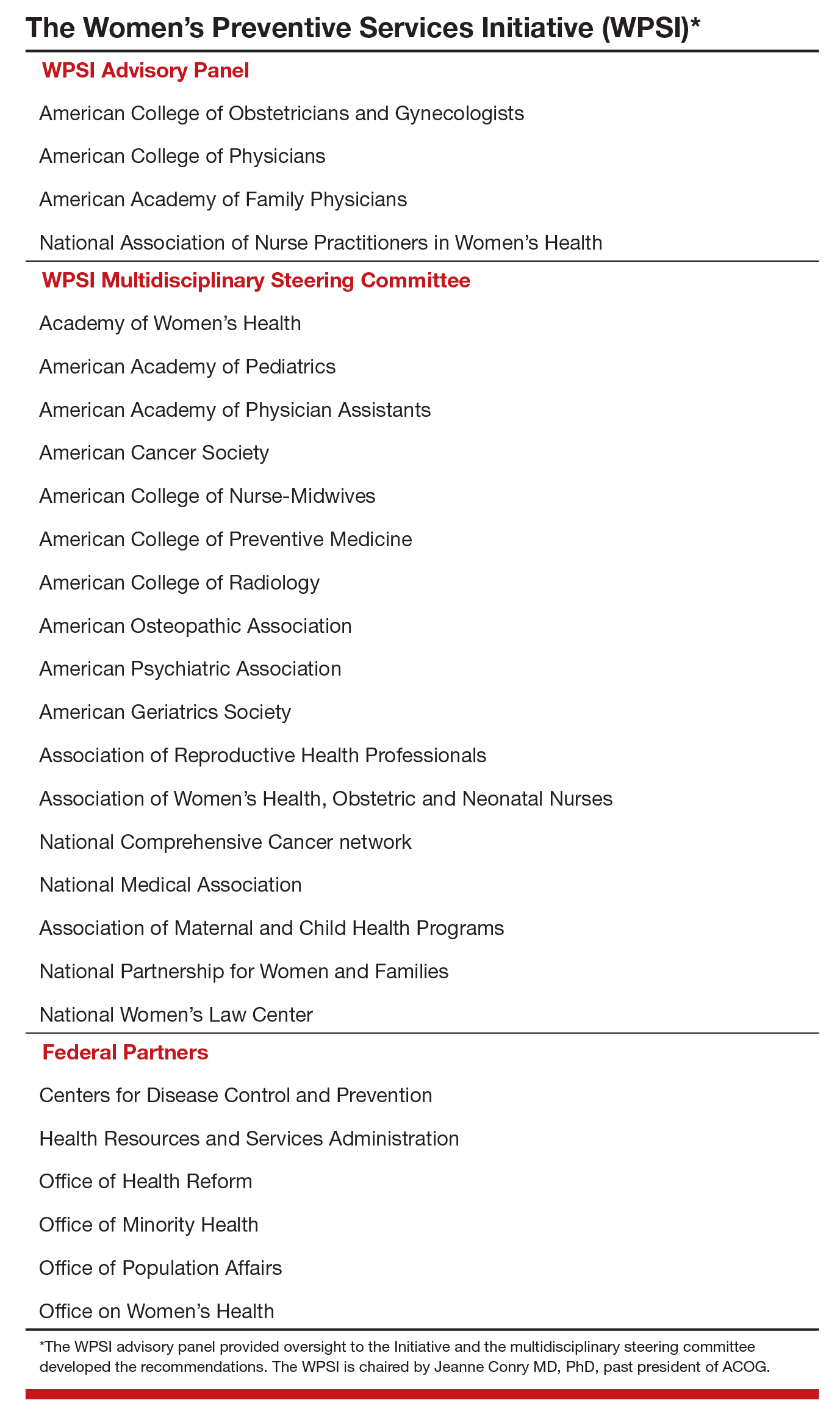

Who makes up the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative?

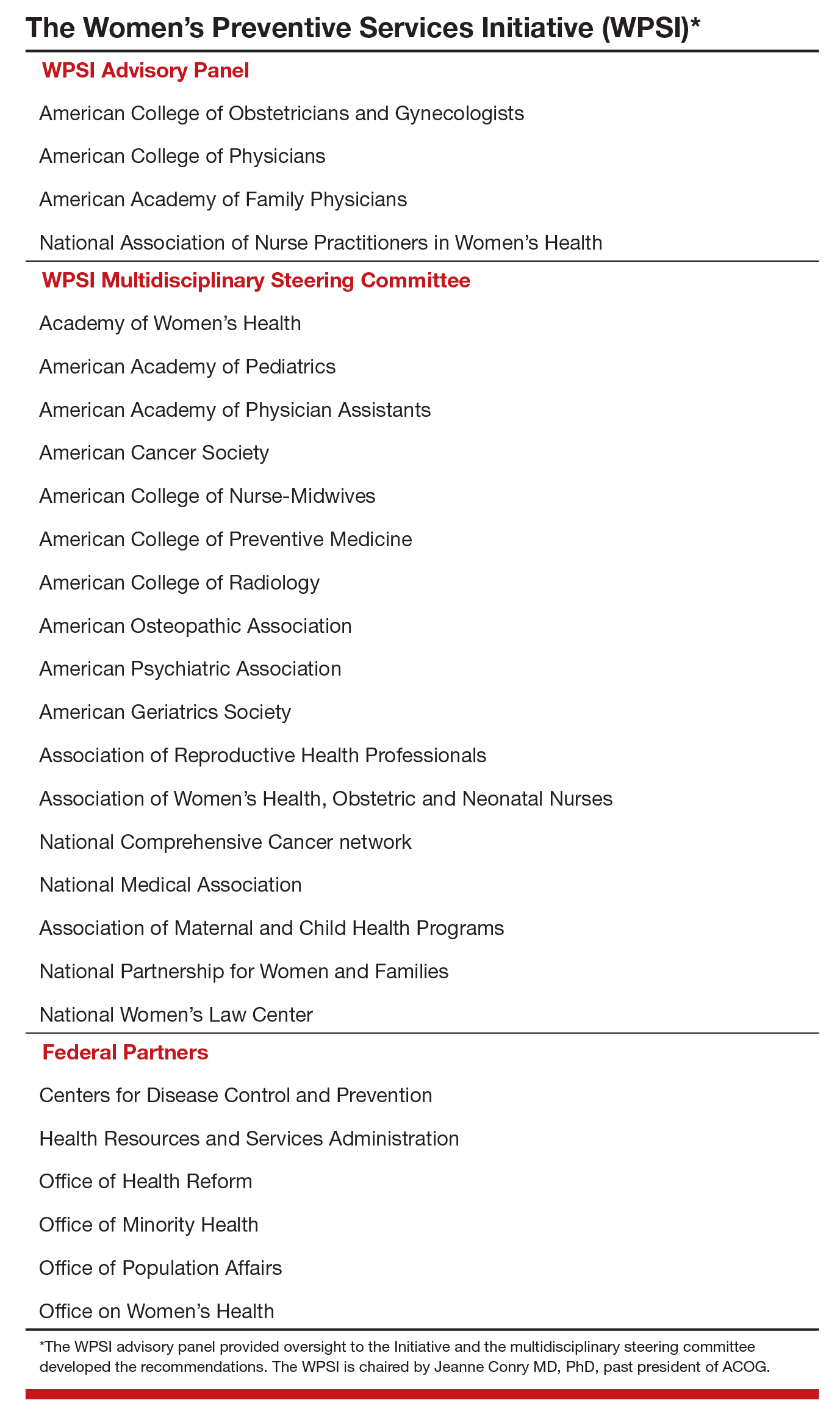

The WPSI is a collaboration between professional societies and consumer organizations. The goal of the WPSI is “to promote health over the course of a woman’s lifetime through disease prevention and preventive healthcare.” The WPSI advisory panel provides oversight to the effort and the multidisciplinary steering committee develops the recommendations. The WPSI advisory panel includes leaders and experts from 4 major professional organizations, whose members provide the majority of women’s health care in the United States:

- ACOG

- American College of Physicians (ACP)

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

- National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH).

The multidisciplinary steering committee includes the members of the advisory panel, representatives from 17 professional and consumer organizations, a patient representative, and representatives from 6 federal agencies. The WPSI is currently chaired by Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, past president of ACOG. The steering committee used evidence-based best practices to develop the guidelines and relied heavily on the foundation provided by the 2011 IOM report.1

The 9 WPSI recommendations

Much of the text below is directly quoted from the final recommendations. When a recommendation is paraphrased it is not placed in quotations.

Recommendation 1: Breast cancer screening for average-risk women

“Average-risk women should initiate mammography screening for breast cancer no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50 years. Screeningmammography should occur at least biennially and as frequently as annually. Screening should continue through at least age 74 years and age alone should not be the basis to stop screening.”

Decisions about when to initiate screening for women between 40 and 50 years of age, how often to screen, and when to stop screening should be based on shared decision making involving the woman and her clinician.

Recommendation 2: Breastfeeding services and supplies

Women should be provided “comprehensive lactation support services including counseling, education and breast feeding equipment and supplies during the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods.” These services will support the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding. Women should have access to double electric breast pumps.

Recommendation 3: Screening for cervical cancer

Average-risk women should initiate cervical cancer screening with cervical cytology at age 21 years and have cervical cytology testing every 3 years from 21 to 29 years of age. “Cotesting with cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is not recommended for women younger than 30 years. Women aged 30 to 65 years should be screened with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years.” Women who have received the HPV vaccine should be screened using these guidelines. Cervical cancer screening is not recommended for women younger than 21 years or older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. Cervical cancer screening is also not recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no personal history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 within the past 20 years.

Recommendation 4: Contraception

Adolescent and adult women should have access to the full range of US Food and Drug Administration–approved female-controlled contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancy and improve birth outcomes. Multiple visits with a clinician may be needed to select an optimal contraceptive.

Recommendation 5: Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

Pregnant women should be screened for GDM between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation to prevent adverse birth outcomes. Screening should be performed with a “50 gm oral glucose challenge test followed by a 3-hour 100 gm oral glucose tolerance test” if the results on the initial oral glucose tolerance test are abnormal. This testing sequence has high sensitivity and specificity. Women with risk factors for diabetes mellitus should be screened for diabetes at the first prenatal visit using current best clinical practice.

Recommendation 6: Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Adolescents and women should receive education and risk assessment for HIV annually and should be tested for HIV at least once during their lifetime. Based on assessed risk, screening annually may be appropriate. “Screening for HIV is recommended for all pregnant women upon initiation of prenatal care with retesting during pregnancy based on risk factors. Rapid HIV testing is recommended for pregnant women who present in active labor with an undocumented HIV status.” Risk-based screening does not identify approximately 20% of HIV-infected people. Hence screening annually may be reasonable.

Recommendation 7: Screening for interpersonal and domestic violence

All adolescents and women should be screened annually for both interpersonal violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV). Intervention services should be available to all adolescents and women. IPV and DV are prevalent problems, and they are often undetected by clinicians. Hence annual screening is recommended.

Recommendation 8: Counseling for sexually transmitted infections

Adolescents and women should be assessed for sexually transmittedinfection (STI) risk. Risk factors include:

- “age younger than 25 years,

- a recent STI,

- a new sex partner,

- multiple partners,

- a partner with concurrent partners,

- a partner with an STI, and

- a lack of or inconsistent condom use.”

Women at increased risk for an STI should receive behavioral counseling.

Recommendation 9: Well-woman preventive visits

Women should “receive at least one preventive care visit per year beginning in adolescence and continuing across the lifespan to ensure that the recommended preventive services including preconception and many services necessary for prenatal and interconception care are obtained. The primary purpose of these visits is the delivery and coordination of recommended preventive services as determined by age and risk factors.”

- Abridged guidelines for the Women's Preventive Services Initiative can be found here: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WPSI_2016AbridgedReport.pdf.

- Evidence-based summaries and appendices are available at this link: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Evidence-Summaries-and-Appendices.pdf.

I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice

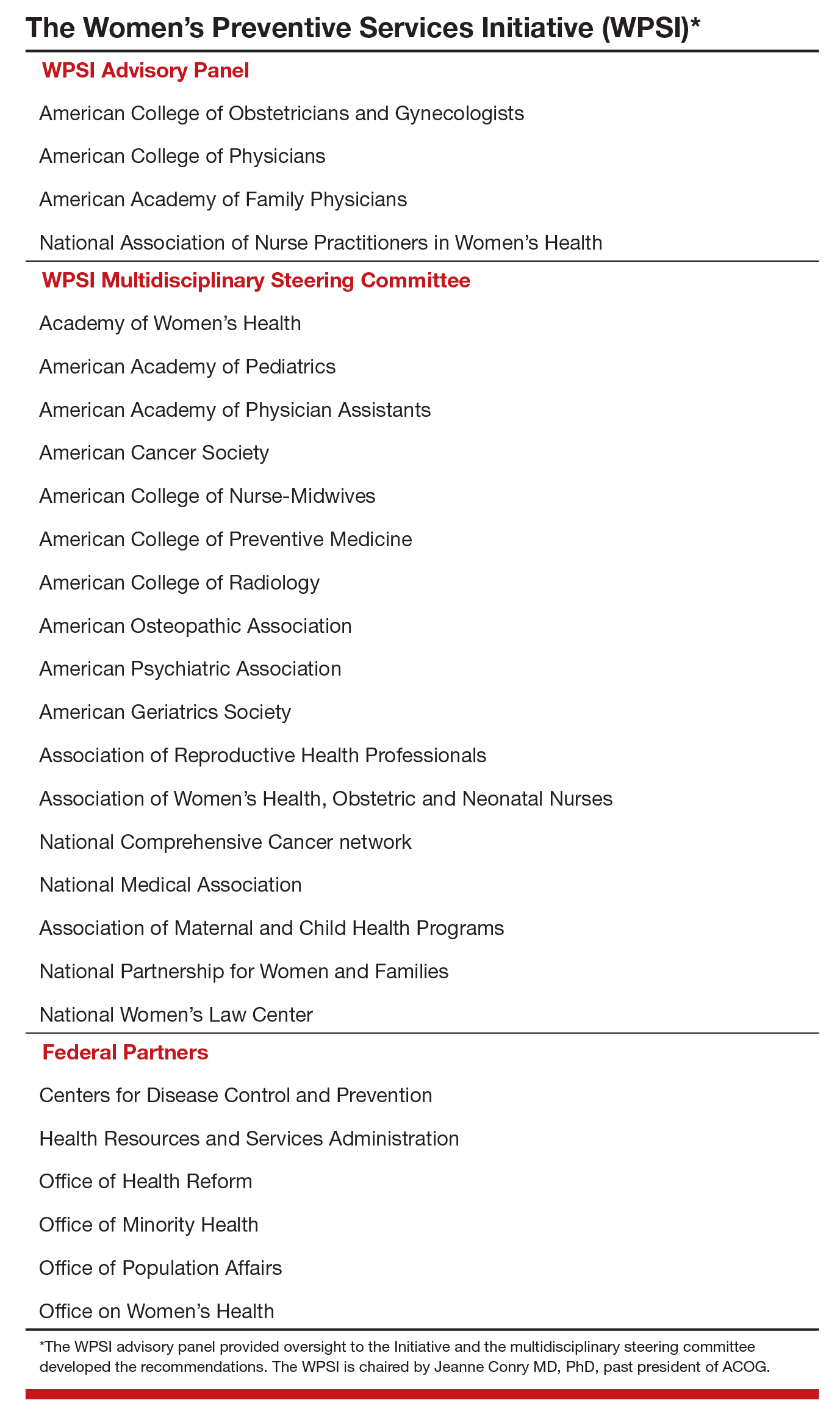

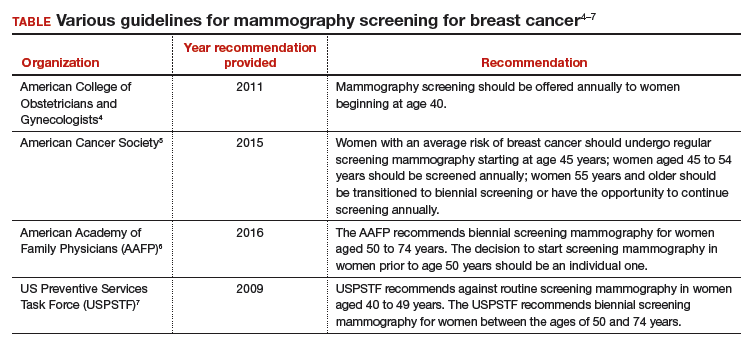

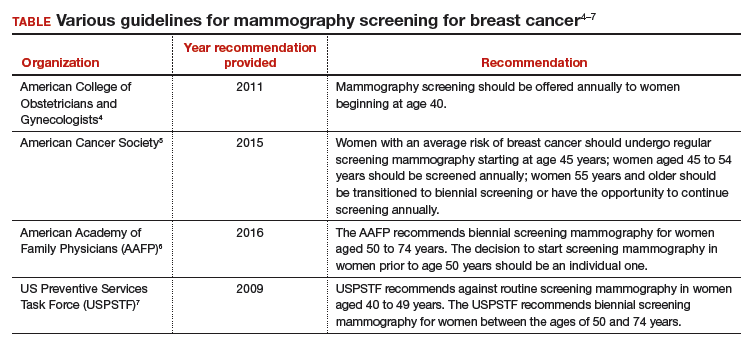

Historically, many high-profile expert professional groups have developed their own women’s health services guidelines. The proliferation of conflicting guidelines confused both patients and clinicians. Dueling guidelines likely undermine public health because they result in confusion among patients and inconsistent care across the many disciplines that provide medical services to women.

The proliferation of conflicting guidelines for mammography screening for breast cancer is a good example of how dueling guidelines can undermine public health (TABLE).4−7 The WPSI has done a great service to women and clinicians by creating a shared framework for consistently providing critical services across a woman’s entire life. I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice. Patients and clinicians will greatly benefit from the exceptionally thoughtful women’s preventive services guidelines provided by the WPSI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://nap.edu/13181. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Women's Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Womens-Preventive-Services-Initiative. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- Health Resources and Services Administration website. Women's preventive services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-382.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614.

- American Academy of Family Physicians website. Clinical preventive service recommendation: breast cancer. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716-726.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) intended that women have access to critical preventive health services without a copay or deductible. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was asked to help identify those critical preventive women’s health services. In 2011, the IOM Committee on Preventive Services for Women recommended that all women have access to 9 preventive services, among them1:

- screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

- human papilloma virus testing

- contraceptive methods and counseling

- well-woman visits.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services agreed to update the recommended preventive services every 5 years.

In March 2016, HRSA entered into a 5-year cooperative agreement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update the guidelines and to develop additional recommendations to enhance women’s health.2 ACOG launched the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) to develop the 2016 update.

The 5-year grant with HRSA will address many more preventive health services for women across their lifespan as well as implementation strategies so that women receive consistent and appropriate care, regardless of the health care provider’s specialty. The WPSI recognizes that the selection of a provider for well-woman care will be determined as much by a woman’s needs and preferences as by her access to health care services and health plan availability.

The WPSI draft recommendations were released for public comment in September 2016,2 and HRSA approved the recommendations in December 2016.3 In this editorial, I provide a look at which organizations comprise the WPSI and a summary of the 9 recommended preventive health services.

Who makes up the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative?

The WPSI is a collaboration between professional societies and consumer organizations. The goal of the WPSI is “to promote health over the course of a woman’s lifetime through disease prevention and preventive healthcare.” The WPSI advisory panel provides oversight to the effort and the multidisciplinary steering committee develops the recommendations. The WPSI advisory panel includes leaders and experts from 4 major professional organizations, whose members provide the majority of women’s health care in the United States:

- ACOG

- American College of Physicians (ACP)

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

- National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH).

The multidisciplinary steering committee includes the members of the advisory panel, representatives from 17 professional and consumer organizations, a patient representative, and representatives from 6 federal agencies. The WPSI is currently chaired by Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, past president of ACOG. The steering committee used evidence-based best practices to develop the guidelines and relied heavily on the foundation provided by the 2011 IOM report.1

The 9 WPSI recommendations

Much of the text below is directly quoted from the final recommendations. When a recommendation is paraphrased it is not placed in quotations.

Recommendation 1: Breast cancer screening for average-risk women

“Average-risk women should initiate mammography screening for breast cancer no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50 years. Screeningmammography should occur at least biennially and as frequently as annually. Screening should continue through at least age 74 years and age alone should not be the basis to stop screening.”

Decisions about when to initiate screening for women between 40 and 50 years of age, how often to screen, and when to stop screening should be based on shared decision making involving the woman and her clinician.

Recommendation 2: Breastfeeding services and supplies

Women should be provided “comprehensive lactation support services including counseling, education and breast feeding equipment and supplies during the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods.” These services will support the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding. Women should have access to double electric breast pumps.

Recommendation 3: Screening for cervical cancer

Average-risk women should initiate cervical cancer screening with cervical cytology at age 21 years and have cervical cytology testing every 3 years from 21 to 29 years of age. “Cotesting with cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is not recommended for women younger than 30 years. Women aged 30 to 65 years should be screened with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years.” Women who have received the HPV vaccine should be screened using these guidelines. Cervical cancer screening is not recommended for women younger than 21 years or older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. Cervical cancer screening is also not recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no personal history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 within the past 20 years.

Recommendation 4: Contraception

Adolescent and adult women should have access to the full range of US Food and Drug Administration–approved female-controlled contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancy and improve birth outcomes. Multiple visits with a clinician may be needed to select an optimal contraceptive.

Recommendation 5: Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

Pregnant women should be screened for GDM between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation to prevent adverse birth outcomes. Screening should be performed with a “50 gm oral glucose challenge test followed by a 3-hour 100 gm oral glucose tolerance test” if the results on the initial oral glucose tolerance test are abnormal. This testing sequence has high sensitivity and specificity. Women with risk factors for diabetes mellitus should be screened for diabetes at the first prenatal visit using current best clinical practice.

Recommendation 6: Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Adolescents and women should receive education and risk assessment for HIV annually and should be tested for HIV at least once during their lifetime. Based on assessed risk, screening annually may be appropriate. “Screening for HIV is recommended for all pregnant women upon initiation of prenatal care with retesting during pregnancy based on risk factors. Rapid HIV testing is recommended for pregnant women who present in active labor with an undocumented HIV status.” Risk-based screening does not identify approximately 20% of HIV-infected people. Hence screening annually may be reasonable.

Recommendation 7: Screening for interpersonal and domestic violence

All adolescents and women should be screened annually for both interpersonal violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV). Intervention services should be available to all adolescents and women. IPV and DV are prevalent problems, and they are often undetected by clinicians. Hence annual screening is recommended.

Recommendation 8: Counseling for sexually transmitted infections

Adolescents and women should be assessed for sexually transmittedinfection (STI) risk. Risk factors include:

- “age younger than 25 years,

- a recent STI,

- a new sex partner,

- multiple partners,

- a partner with concurrent partners,

- a partner with an STI, and

- a lack of or inconsistent condom use.”

Women at increased risk for an STI should receive behavioral counseling.

Recommendation 9: Well-woman preventive visits

Women should “receive at least one preventive care visit per year beginning in adolescence and continuing across the lifespan to ensure that the recommended preventive services including preconception and many services necessary for prenatal and interconception care are obtained. The primary purpose of these visits is the delivery and coordination of recommended preventive services as determined by age and risk factors.”

- Abridged guidelines for the Women's Preventive Services Initiative can be found here: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WPSI_2016AbridgedReport.pdf.

- Evidence-based summaries and appendices are available at this link: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Evidence-Summaries-and-Appendices.pdf.

I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice

Historically, many high-profile expert professional groups have developed their own women’s health services guidelines. The proliferation of conflicting guidelines confused both patients and clinicians. Dueling guidelines likely undermine public health because they result in confusion among patients and inconsistent care across the many disciplines that provide medical services to women.

The proliferation of conflicting guidelines for mammography screening for breast cancer is a good example of how dueling guidelines can undermine public health (TABLE).4−7 The WPSI has done a great service to women and clinicians by creating a shared framework for consistently providing critical services across a woman’s entire life. I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice. Patients and clinicians will greatly benefit from the exceptionally thoughtful women’s preventive services guidelines provided by the WPSI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010 (ACA) intended that women have access to critical preventive health services without a copay or deductible. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) was asked to help identify those critical preventive women’s health services. In 2011, the IOM Committee on Preventive Services for Women recommended that all women have access to 9 preventive services, among them1:

- screening for gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM)

- human papilloma virus testing

- contraceptive methods and counseling

- well-woman visits.

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services agreed to update the recommended preventive services every 5 years.

In March 2016, HRSA entered into a 5-year cooperative agreement with the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) to update the guidelines and to develop additional recommendations to enhance women’s health.2 ACOG launched the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI) to develop the 2016 update.

The 5-year grant with HRSA will address many more preventive health services for women across their lifespan as well as implementation strategies so that women receive consistent and appropriate care, regardless of the health care provider’s specialty. The WPSI recognizes that the selection of a provider for well-woman care will be determined as much by a woman’s needs and preferences as by her access to health care services and health plan availability.

The WPSI draft recommendations were released for public comment in September 2016,2 and HRSA approved the recommendations in December 2016.3 In this editorial, I provide a look at which organizations comprise the WPSI and a summary of the 9 recommended preventive health services.

Who makes up the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative?

The WPSI is a collaboration between professional societies and consumer organizations. The goal of the WPSI is “to promote health over the course of a woman’s lifetime through disease prevention and preventive healthcare.” The WPSI advisory panel provides oversight to the effort and the multidisciplinary steering committee develops the recommendations. The WPSI advisory panel includes leaders and experts from 4 major professional organizations, whose members provide the majority of women’s health care in the United States:

- ACOG

- American College of Physicians (ACP)

- American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP)

- National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health (NPWH).

The multidisciplinary steering committee includes the members of the advisory panel, representatives from 17 professional and consumer organizations, a patient representative, and representatives from 6 federal agencies. The WPSI is currently chaired by Jeanne Conry, MD, PhD, past president of ACOG. The steering committee used evidence-based best practices to develop the guidelines and relied heavily on the foundation provided by the 2011 IOM report.1

The 9 WPSI recommendations

Much of the text below is directly quoted from the final recommendations. When a recommendation is paraphrased it is not placed in quotations.

Recommendation 1: Breast cancer screening for average-risk women

“Average-risk women should initiate mammography screening for breast cancer no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50 years. Screeningmammography should occur at least biennially and as frequently as annually. Screening should continue through at least age 74 years and age alone should not be the basis to stop screening.”

Decisions about when to initiate screening for women between 40 and 50 years of age, how often to screen, and when to stop screening should be based on shared decision making involving the woman and her clinician.

Recommendation 2: Breastfeeding services and supplies

Women should be provided “comprehensive lactation support services including counseling, education and breast feeding equipment and supplies during the antenatal, perinatal, and postpartum periods.” These services will support the successful initiation and maintenance of breastfeeding. Women should have access to double electric breast pumps.

Recommendation 3: Screening for cervical cancer

Average-risk women should initiate cervical cancer screening with cervical cytology at age 21 years and have cervical cytology testing every 3 years from 21 to 29 years of age. “Cotesting with cytology and human papillomavirus (HPV) testing is not recommended for women younger than 30 years. Women aged 30 to 65 years should be screened with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years or cytology alone every 3 years.” Women who have received the HPV vaccine should be screened using these guidelines. Cervical cancer screening is not recommended for women younger than 21 years or older than 65 years who have had adequate prior screening and are not at high risk for cervical cancer. Cervical cancer screening is also not recommended for women who have had a hysterectomy with removal of the cervix and no personal history of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or 3 within the past 20 years.

Recommendation 4: Contraception

Adolescent and adult women should have access to the full range of US Food and Drug Administration–approved female-controlled contraceptives to prevent unintended pregnancy and improve birth outcomes. Multiple visits with a clinician may be needed to select an optimal contraceptive.

Recommendation 5: Screening for gestational diabetes mellitus

Pregnant women should be screened for GDM between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation to prevent adverse birth outcomes. Screening should be performed with a “50 gm oral glucose challenge test followed by a 3-hour 100 gm oral glucose tolerance test” if the results on the initial oral glucose tolerance test are abnormal. This testing sequence has high sensitivity and specificity. Women with risk factors for diabetes mellitus should be screened for diabetes at the first prenatal visit using current best clinical practice.

Recommendation 6: Screening for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection

Adolescents and women should receive education and risk assessment for HIV annually and should be tested for HIV at least once during their lifetime. Based on assessed risk, screening annually may be appropriate. “Screening for HIV is recommended for all pregnant women upon initiation of prenatal care with retesting during pregnancy based on risk factors. Rapid HIV testing is recommended for pregnant women who present in active labor with an undocumented HIV status.” Risk-based screening does not identify approximately 20% of HIV-infected people. Hence screening annually may be reasonable.

Recommendation 7: Screening for interpersonal and domestic violence

All adolescents and women should be screened annually for both interpersonal violence (IPV) and domestic violence (DV). Intervention services should be available to all adolescents and women. IPV and DV are prevalent problems, and they are often undetected by clinicians. Hence annual screening is recommended.

Recommendation 8: Counseling for sexually transmitted infections

Adolescents and women should be assessed for sexually transmittedinfection (STI) risk. Risk factors include:

- “age younger than 25 years,

- a recent STI,

- a new sex partner,

- multiple partners,

- a partner with concurrent partners,

- a partner with an STI, and

- a lack of or inconsistent condom use.”

Women at increased risk for an STI should receive behavioral counseling.

Recommendation 9: Well-woman preventive visits

Women should “receive at least one preventive care visit per year beginning in adolescence and continuing across the lifespan to ensure that the recommended preventive services including preconception and many services necessary for prenatal and interconception care are obtained. The primary purpose of these visits is the delivery and coordination of recommended preventive services as determined by age and risk factors.”

- Abridged guidelines for the Women's Preventive Services Initiative can be found here: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WPSI_2016AbridgedReport.pdf.

- Evidence-based summaries and appendices are available at this link: http://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Evidence-Summaries-and-Appendices.pdf.

I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice

Historically, many high-profile expert professional groups have developed their own women’s health services guidelines. The proliferation of conflicting guidelines confused both patients and clinicians. Dueling guidelines likely undermine public health because they result in confusion among patients and inconsistent care across the many disciplines that provide medical services to women.

The proliferation of conflicting guidelines for mammography screening for breast cancer is a good example of how dueling guidelines can undermine public health (TABLE).4−7 The WPSI has done a great service to women and clinicians by creating a shared framework for consistently providing critical services across a woman’s entire life. I plan on using these recommendations to guide my practice. Patients and clinicians will greatly benefit from the exceptionally thoughtful women’s preventive services guidelines provided by the WPSI.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://nap.edu/13181. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Women's Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Womens-Preventive-Services-Initiative. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- Health Resources and Services Administration website. Women's preventive services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-382.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614.

- American Academy of Family Physicians website. Clinical preventive service recommendation: breast cancer. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716-726.

- Institute of Medicine. Clinical preventive services for women: closing the gaps. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. http://nap.edu/13181. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Women's Preventive Services Initiative (WPSI). http://www.acog.org/About-ACOG/ACOG-Departments/Annual-Womens-Health-Care/Womens-Preventive-Services-Initiative. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- Health Resources and Services Administration website. Women's preventive services guidelines. https://www.hrsa.gov/womensguidelines/. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(2 pt 1):372-382.

- Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599-1614.

- American Academy of Family Physicians website. Clinical preventive service recommendation: breast cancer. http://www.aafp.org/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all/breast-cancer.html. Accessed January 16, 2017.

- US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716-726.