User login

How state budget crises are putting the squeeze on Medicaid (and you)

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere (October 2011)

Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lucia DiVenere (July 2010)

Is the patient-centered medical home a win-all or lose-all proposition for ObGyns?

Janelle Yates (October 2010)

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Tough economic times have pushed 2.8 million more people onto Medicaid rolls, now crowded with more than 60 million low-income individuals and families—nearly 20% of the US population.

Because Medicaid is a means-tested entitlement program, states and the federal government must fund as much health care as beneficiaries use, an expense that increases substantially each year.

Through the Medicaid program, more than 30 million adult women have access to an annual gynecologic exam, family planning services, and prenatal care. Without such coverage, many of them would go without care, potentially driving our nation’s health-care costs even higher. Two thirds of ObGyns treat Medicaid patients, and Medicaid accounts for 18%, on average, of an ObGyn practice’s revenue.1

In this article, I describe how the burgeoning ranks of Medicaid beneficiaries are straining state budgets and prompting legislators to cut provider payments to make up the shortfall. The federal government also plays a role in shrinking reimbursements for physicians and other providers.

Medicaid costs are outpacing economic growth

In fiscal 2011, Medicaid enrollment grew an average of 5.5%, and states are anticipating a growth rate of 4.1% in 2012.2 Total Medicaid spending is also increasing rapidly. In fiscal 2010, it was $361.8 billion (excluding administrative costs)—a 6% increase over fiscal 2009. By the end of fiscal 2011, it was expected to hit $398.6 billion—a 10.1% increase over 2010.3

Medicaid costs are also absorbing a greater share of state budgets. In fiscal 2009, they accounted for 21.9% of total state expenditures, 22.3% in fiscal 2010, and 23.6% in fiscal 2011.3 Many states have had to reduce spending in other important areas as a result (TABLE 1).

Medicaid costs are shared by federal and state governments. The federal government pays, on average, 57% of state program costs. In fiscal 2010, the federal government covered 64.6% of all Medicaid costs.

State general funds at the end of 2011 were well below their pre-recession levels, due to lower revenues and increased expenditures, including continued obligations for state workers’ pensions and retiree health care. At the same time, 49 state governments are required to balance their budgets. As a result, states are likely to face austere budgets for at least the next several years, and will continue to make difficult spending decisions.

As state and federal budgets face pressure to reduce overall spending, Medicaid lies in nearly all budget crosshairs.

TABLE 1

Medicaid absorbs an ever-greater percentage of state expenditures

| State | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal 2009 | Fiscal 2010 | Fiscal 2011 | |

| New England | |||

| Connecticut | 27.9 | 25.4 | 27.2 |

| Maine | 29.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Massachusetts | 17.8 | 18.8 | 20.2 |

| New Hampshire | 26.5 | 24.9 | 25.2 |

| Rhode Island | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| Vermont | 25.5 | 25.9 | 26.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | |||

| Delaware | 12.3 | 14.4 | 16.2 |

| Maryland | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.6 |

| New Jersey | 19.8 | 21.3 | 21.9 |

| New york | 26.7 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 30.2 | 29.6 | 31.1 |

| Great Lakes | |||

| Illinois | 24.8 | 23.6 | 28.9 |

| Indiana | 21.8 | 23.1 | 24.4 |

| Michigan | 23.0 | 24.2 | 24.0 |

| Ohio | 20.6 | 21.3 | 23.2 |

| Wisconsin | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.0 |

| Plains | |||

| Iowa | 17.9 | 18.6 | 19.3 |

| Kansas | 17.4 | 18.8 | 18.6 |

| Minnesota | 24.0 | 25.1 | 25.1 |

| Missouri | 35.6 | 34.4 | 36.3 |

| Nebraska | 17.6 | 17.2 | 16.5 |

| North Dakota | 14.1 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| South Dakota | 21.6 | 21.7 | 23.2 |

| Southeast | |||

| Alabama | 25.6 | 25.8 | 25.3 |

| Arkansas | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 |

| Florida | 26.7 | 30.0 | 28.0 |

| Georgia | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.5 |

| Kentucky | 22.5 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| Louisiana | 22.0 | 23.7 | 23.5 |

| Mississippi | 24.8 | 22.9 | 22.6 |

| North Carolina | 25.0 | 24.2 | 22.1 |

| South Carolina | 22.0 | 22.6 | 19.9 |

| Tennessee | 25.4 | 28.8 | 28.1 |

| Virginia | 16.4 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| West Virginia | 11.9 | 12.6 | 13.0 |

| Southwest | |||

| Arizona | 29.3 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| New Mexico | 20.7 | 22.1 | 20.2 |

| Oklahoma | 17.7 | 17.1 | 18.5 |

| Texas | 22.8 | 24.6 | 26.3 |

| Rocky Mountain | |||

| Colorado | 14.1 | 15.3 | 19.4 |

| Idaho | 22.8 | 23.0 | 25.6 |

| Montana | 15.2 | 15.4 | 15.7 |

| Utah | 14.9 | 11.9 | 14.3 |

| Wyoming | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Far West | |||

| Alaska | 8.1 | 12.0 | 9.0 |

| California | 20.6 | 18.9 | 24.2 |

| Hawaii | 11.3 | 13.3 | 15.9 |

| Nevada | 16.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 |

| Oregon | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.6 |

| Washington | 21.4 | 23.0 | 24.4 |

| Average | 21.9 | 22.3 | 23.6 |

The fiscal health of Medicaid matters—here’s why

Twelve percent of women 18 to 64 years old rely on Medicaid for health-care coverage, and three quarters of all adult Medicaid beneficiaries are women. Sixty-nine percent of women in the 18- to 64-year-old age group are in their reproductive years. Medicaid pays for 42% of all births in the United States—as many as 64% of all births in Arkansas and Oklahoma.4

Medicaid covers essential well-woman care, including maternity care, breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment, care for disabled women, and family planning.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for contraception and sterilization services, covering 71% of these costs. States clearly find it in their best interest and the best interest of public health to encourage use of family planning, which can improve women’s health and reduce the number of unintended pregnancies and abortions. In 2010, 27 states extended family planning coverage to women whose incomes, while still low, were higher than the standard Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Many states cover nutrition and substance abuse counseling, health education, psychosocial counseling, breastfeeding, and case management. TABLE 2 on page 16a lists mandatory and optional Medicaid services.

TABLE 2

Benefits of the Medicaid program

| Mandatory | Optional |

|---|---|

| Physician services Laboratory and radiographic services Hospitalization Outpatient services Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services for people younger than 21 years Family planning Rural and federally qualified health center services Nurse midwife services Nursing facility services for people older than 21 years Home health care for people entitled to nursing facility care Smoking cessation for pregnant women* Free-standing birth center services* | Prescription drugs Clinic services Dental services, dentures Physical therapy and rehabilitation Prosthetic devices, eyeglasses Primary-care case management Intermediate-care facilities for the mentally retarded Inpatient psychiatric care for people younger than 21 years Home health care and other services provided under home- and community-based waivers Personal care services Hospice care Health home services for people with chronic conditions* Home- and community-based attendant services and supports* |

| * Benefits added under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | |

Coming: Another 4.5 million women on Medicaid rolls

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Medicaid will expand to cover another 4.5 million women in 2014. Beginning January 1, 2014, state Medicaid programs are required to cover nonpregnant, non-elderly individuals who have incomes as high as 133% of the federal poverty level ($10,890 for an individual in 2011). The federal government will cover the full expense of insuring these newly eligible individuals for calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016. Federal financing will phase down to 90% by 2020, and will likely decrease further after that.

States that participate in Medicaid must cover pregnant women who have an income at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. States are required to disregard 5% of an individual’s income when determining Medicaid eligibility, a rule that effectively brings the maximum eligibility level to 138% of the federal poverty level, opening the Medicaid doors to additional low-income individuals.

Today, coverage lasts throughout pregnancy and 2 months beyond. States may choose to extend eligibility to pregnant women who have incomes that exceed 133% of the poverty level; at present, 45 states do so, with the District of Columbia topping the list by covering pregnant women who have incomes at or below 300% of the poverty level.

Many measures show that Medicaid has improved access to health care for low- income women, saving lives and dollars. Your experience—wherever you practice— undoubtedly echoes that observation.

Prenatal care. You also know that prenatal care helps ensure healthy babies. Obstetric services often go beyond traditional medical needs to include a full spectrum of care that helps ensure a healthy pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period.

Of course, inadequate use of prenatal care is associated with increased risks of low birth weight, preterm birth, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and maternal mortality. Preterm births alone increase US health-care costs by $26 billion each year.5 Pregnancy-related maternal mortality is three to four times higher, and infant mortality is more than six times higher, among women who receive no prenatal care, compared with those who receive prenatal care.

Gynecologic services covered through Medicaid also help preserve health and reduce health-care costs. Eighty-four percent of women on Medicaid have had a Pap test in the past 2 years, compared with 80% of women who have private insurance and 59% of women who lack insurance.6 Routine gynecologic care is vital to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases. Women without a regular doctor don’t get regular Pap tests and mammography; nor do they get screened for other serious health risks, including high cholesterol and diabetes.

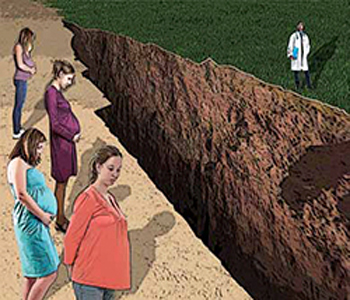

Despite the proven benefits of access to regular care, 23% of women on Medicaid report problems finding a new doctor who will accept their insurance, compared with 7% of Medicare beneficiaries and 13% of women who have private insurance.

Why the difficulty in finding a doctor? A leading reason is the inadequacy of Medicaid payment rates.

Cutting payments to physicians

Medicaid provider payments are often the first item cut in a state budget crisis. States are required to cover many health services and are restricted from charging patients significant co-pays, so they often trim budgets at the expense of physicians. Thirty-nine states reduced physician and provider payments in 2011, and 46 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012. In addition, in fiscal 2011, 47 states put in place at least one new policy to control Medicaid costs; most states implemented several of these policies. All 50 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012.

Under federal rules, states must ensure that payment rates are consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. They also must ensure that payment is sufficient to enlist enough providers to render care and services to the same extent that care and services are available to the general population in the same geographic area. States must request and receive permission from the federal government before reducing provider payment rates. However, even with this safeguard in place, physician payments—and patient access to care—are in jeopardy.

For example, in 2008, the California legislature issued several rounds of cuts, including a 10% cut in physician and provider payments, to make up for budget shortfalls. Physicians, hospitals, pharmacists, and other health professionals sued in response, and the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the payment cut.

In 2011, California Governor Jerry Brown again put the 10% cut in place, this time with approval from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In response, California physicians, led by the state medical association, sued California again. They argued that payment cuts reduce access to care among Medicaid beneficiaries by prompting physicians to stop accepting these patients. The California Department of Health Care Services countered that the cuts are necessary to offset a critical budget shortfall and will not affect access to care. The situation in California highlights the conflicts between physicians and many states over Medicaid payment rates.

The US Supreme Court agreed to review the case on only one question—whether individuals and private parties, including doctors and Medicaid recipients, can sue the state for failing to pay rates that meet the federal adequacy requirement. On October 3, 2011, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this group of cases, known as Douglas v. Independent Living Center of Southern California. ACOG joined the case in support of physicians.

Medicaid versus Medicare

It’s easy to see how important Medicaid is to women’s health, and how important physician payment rates are to women’s access to care. You might expect, then, that states would recognize the value of adequate physician payment—but they don’t, always.

At present, Medicaid pays for obstetric care at 93% of the Medicare rate. Still, obstetric care fares slightly better than many physician services. In many states, it costs physicians much more than Medicaid pays to provide non-obstetric care to Mediaid patients. Although 23 states pay for obstetric care at a rate lower than that offered by Medicare, 27 states offer greater support, and 16 states offer reimbursement well above the Medicare rate.

A federal target, too

The states aren’t the only entities with an eye on Medicaid cuts. The US Congress, too, is considering proposals to dramatically change the program. The options include issuing block grants for Medicaid; reducing the federal match; and including Medicaid in global or health spending caps. ACOG has an extensive campaign under way to ensure that any changes to Medicaid do not come at the expense of women’s health.

The Congressional Joint Special Committee on Deficit Reduction—more commonly known as the Supercommittee— represents the latest effort at deficit reduction. When its work imploded in December 2011, federal programs came online for a 2% across-the-board cut (“sequester”) that will take effect on January 1, 2013. The Medicaid program is exempt from this cut, no doubt in recognition of the already-precarious nature of this program, which has become a safety net for millions of American families struggling through the recession.

Because so many American women rely on Medicaid for obstetric and gynecologic care, it is critical that we protect funding levels and maintain eligibility for this program.

ACOG plays a prominent role in advocating for preservation of women’s access to care and adequate physician reimbursement levels. you can help by contacting your state legislators and representatives in the uS Congress to emphasize the importance of these efforts.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2008 Socioeconomic Survey of ACOG Fellows. Washington DC: ACOG; 2008.

2. Holahan J, Headen I. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State-by-State Results for Adults at or Below 133% FPL. Washington DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010.

3. National Association of State Budget Officers. State Expenditure Report 2010. Washington DC: NASBO; December 2011.

4. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. 2010 Maternal and Child Health Update. Issue Brief. Washington DC: National Governors Association; 2011. http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF. Accessed January 12, 2011.

5. Behrman RE, Butler AS. eds Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Women’s Health Survey 2004. Washington DC: KFF; 2005.

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere (October 2011)

Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lucia DiVenere (July 2010)

Is the patient-centered medical home a win-all or lose-all proposition for ObGyns?

Janelle Yates (October 2010)

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Tough economic times have pushed 2.8 million more people onto Medicaid rolls, now crowded with more than 60 million low-income individuals and families—nearly 20% of the US population.

Because Medicaid is a means-tested entitlement program, states and the federal government must fund as much health care as beneficiaries use, an expense that increases substantially each year.

Through the Medicaid program, more than 30 million adult women have access to an annual gynecologic exam, family planning services, and prenatal care. Without such coverage, many of them would go without care, potentially driving our nation’s health-care costs even higher. Two thirds of ObGyns treat Medicaid patients, and Medicaid accounts for 18%, on average, of an ObGyn practice’s revenue.1

In this article, I describe how the burgeoning ranks of Medicaid beneficiaries are straining state budgets and prompting legislators to cut provider payments to make up the shortfall. The federal government also plays a role in shrinking reimbursements for physicians and other providers.

Medicaid costs are outpacing economic growth

In fiscal 2011, Medicaid enrollment grew an average of 5.5%, and states are anticipating a growth rate of 4.1% in 2012.2 Total Medicaid spending is also increasing rapidly. In fiscal 2010, it was $361.8 billion (excluding administrative costs)—a 6% increase over fiscal 2009. By the end of fiscal 2011, it was expected to hit $398.6 billion—a 10.1% increase over 2010.3

Medicaid costs are also absorbing a greater share of state budgets. In fiscal 2009, they accounted for 21.9% of total state expenditures, 22.3% in fiscal 2010, and 23.6% in fiscal 2011.3 Many states have had to reduce spending in other important areas as a result (TABLE 1).

Medicaid costs are shared by federal and state governments. The federal government pays, on average, 57% of state program costs. In fiscal 2010, the federal government covered 64.6% of all Medicaid costs.

State general funds at the end of 2011 were well below their pre-recession levels, due to lower revenues and increased expenditures, including continued obligations for state workers’ pensions and retiree health care. At the same time, 49 state governments are required to balance their budgets. As a result, states are likely to face austere budgets for at least the next several years, and will continue to make difficult spending decisions.

As state and federal budgets face pressure to reduce overall spending, Medicaid lies in nearly all budget crosshairs.

TABLE 1

Medicaid absorbs an ever-greater percentage of state expenditures

| State | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal 2009 | Fiscal 2010 | Fiscal 2011 | |

| New England | |||

| Connecticut | 27.9 | 25.4 | 27.2 |

| Maine | 29.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Massachusetts | 17.8 | 18.8 | 20.2 |

| New Hampshire | 26.5 | 24.9 | 25.2 |

| Rhode Island | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| Vermont | 25.5 | 25.9 | 26.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | |||

| Delaware | 12.3 | 14.4 | 16.2 |

| Maryland | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.6 |

| New Jersey | 19.8 | 21.3 | 21.9 |

| New york | 26.7 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 30.2 | 29.6 | 31.1 |

| Great Lakes | |||

| Illinois | 24.8 | 23.6 | 28.9 |

| Indiana | 21.8 | 23.1 | 24.4 |

| Michigan | 23.0 | 24.2 | 24.0 |

| Ohio | 20.6 | 21.3 | 23.2 |

| Wisconsin | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.0 |

| Plains | |||

| Iowa | 17.9 | 18.6 | 19.3 |

| Kansas | 17.4 | 18.8 | 18.6 |

| Minnesota | 24.0 | 25.1 | 25.1 |

| Missouri | 35.6 | 34.4 | 36.3 |

| Nebraska | 17.6 | 17.2 | 16.5 |

| North Dakota | 14.1 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| South Dakota | 21.6 | 21.7 | 23.2 |

| Southeast | |||

| Alabama | 25.6 | 25.8 | 25.3 |

| Arkansas | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 |

| Florida | 26.7 | 30.0 | 28.0 |

| Georgia | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.5 |

| Kentucky | 22.5 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| Louisiana | 22.0 | 23.7 | 23.5 |

| Mississippi | 24.8 | 22.9 | 22.6 |

| North Carolina | 25.0 | 24.2 | 22.1 |

| South Carolina | 22.0 | 22.6 | 19.9 |

| Tennessee | 25.4 | 28.8 | 28.1 |

| Virginia | 16.4 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| West Virginia | 11.9 | 12.6 | 13.0 |

| Southwest | |||

| Arizona | 29.3 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| New Mexico | 20.7 | 22.1 | 20.2 |

| Oklahoma | 17.7 | 17.1 | 18.5 |

| Texas | 22.8 | 24.6 | 26.3 |

| Rocky Mountain | |||

| Colorado | 14.1 | 15.3 | 19.4 |

| Idaho | 22.8 | 23.0 | 25.6 |

| Montana | 15.2 | 15.4 | 15.7 |

| Utah | 14.9 | 11.9 | 14.3 |

| Wyoming | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Far West | |||

| Alaska | 8.1 | 12.0 | 9.0 |

| California | 20.6 | 18.9 | 24.2 |

| Hawaii | 11.3 | 13.3 | 15.9 |

| Nevada | 16.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 |

| Oregon | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.6 |

| Washington | 21.4 | 23.0 | 24.4 |

| Average | 21.9 | 22.3 | 23.6 |

The fiscal health of Medicaid matters—here’s why

Twelve percent of women 18 to 64 years old rely on Medicaid for health-care coverage, and three quarters of all adult Medicaid beneficiaries are women. Sixty-nine percent of women in the 18- to 64-year-old age group are in their reproductive years. Medicaid pays for 42% of all births in the United States—as many as 64% of all births in Arkansas and Oklahoma.4

Medicaid covers essential well-woman care, including maternity care, breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment, care for disabled women, and family planning.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for contraception and sterilization services, covering 71% of these costs. States clearly find it in their best interest and the best interest of public health to encourage use of family planning, which can improve women’s health and reduce the number of unintended pregnancies and abortions. In 2010, 27 states extended family planning coverage to women whose incomes, while still low, were higher than the standard Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Many states cover nutrition and substance abuse counseling, health education, psychosocial counseling, breastfeeding, and case management. TABLE 2 on page 16a lists mandatory and optional Medicaid services.

TABLE 2

Benefits of the Medicaid program

| Mandatory | Optional |

|---|---|

| Physician services Laboratory and radiographic services Hospitalization Outpatient services Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services for people younger than 21 years Family planning Rural and federally qualified health center services Nurse midwife services Nursing facility services for people older than 21 years Home health care for people entitled to nursing facility care Smoking cessation for pregnant women* Free-standing birth center services* | Prescription drugs Clinic services Dental services, dentures Physical therapy and rehabilitation Prosthetic devices, eyeglasses Primary-care case management Intermediate-care facilities for the mentally retarded Inpatient psychiatric care for people younger than 21 years Home health care and other services provided under home- and community-based waivers Personal care services Hospice care Health home services for people with chronic conditions* Home- and community-based attendant services and supports* |

| * Benefits added under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | |

Coming: Another 4.5 million women on Medicaid rolls

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Medicaid will expand to cover another 4.5 million women in 2014. Beginning January 1, 2014, state Medicaid programs are required to cover nonpregnant, non-elderly individuals who have incomes as high as 133% of the federal poverty level ($10,890 for an individual in 2011). The federal government will cover the full expense of insuring these newly eligible individuals for calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016. Federal financing will phase down to 90% by 2020, and will likely decrease further after that.

States that participate in Medicaid must cover pregnant women who have an income at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. States are required to disregard 5% of an individual’s income when determining Medicaid eligibility, a rule that effectively brings the maximum eligibility level to 138% of the federal poverty level, opening the Medicaid doors to additional low-income individuals.

Today, coverage lasts throughout pregnancy and 2 months beyond. States may choose to extend eligibility to pregnant women who have incomes that exceed 133% of the poverty level; at present, 45 states do so, with the District of Columbia topping the list by covering pregnant women who have incomes at or below 300% of the poverty level.

Many measures show that Medicaid has improved access to health care for low- income women, saving lives and dollars. Your experience—wherever you practice— undoubtedly echoes that observation.

Prenatal care. You also know that prenatal care helps ensure healthy babies. Obstetric services often go beyond traditional medical needs to include a full spectrum of care that helps ensure a healthy pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period.

Of course, inadequate use of prenatal care is associated with increased risks of low birth weight, preterm birth, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and maternal mortality. Preterm births alone increase US health-care costs by $26 billion each year.5 Pregnancy-related maternal mortality is three to four times higher, and infant mortality is more than six times higher, among women who receive no prenatal care, compared with those who receive prenatal care.

Gynecologic services covered through Medicaid also help preserve health and reduce health-care costs. Eighty-four percent of women on Medicaid have had a Pap test in the past 2 years, compared with 80% of women who have private insurance and 59% of women who lack insurance.6 Routine gynecologic care is vital to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases. Women without a regular doctor don’t get regular Pap tests and mammography; nor do they get screened for other serious health risks, including high cholesterol and diabetes.

Despite the proven benefits of access to regular care, 23% of women on Medicaid report problems finding a new doctor who will accept their insurance, compared with 7% of Medicare beneficiaries and 13% of women who have private insurance.

Why the difficulty in finding a doctor? A leading reason is the inadequacy of Medicaid payment rates.

Cutting payments to physicians

Medicaid provider payments are often the first item cut in a state budget crisis. States are required to cover many health services and are restricted from charging patients significant co-pays, so they often trim budgets at the expense of physicians. Thirty-nine states reduced physician and provider payments in 2011, and 46 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012. In addition, in fiscal 2011, 47 states put in place at least one new policy to control Medicaid costs; most states implemented several of these policies. All 50 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012.

Under federal rules, states must ensure that payment rates are consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. They also must ensure that payment is sufficient to enlist enough providers to render care and services to the same extent that care and services are available to the general population in the same geographic area. States must request and receive permission from the federal government before reducing provider payment rates. However, even with this safeguard in place, physician payments—and patient access to care—are in jeopardy.

For example, in 2008, the California legislature issued several rounds of cuts, including a 10% cut in physician and provider payments, to make up for budget shortfalls. Physicians, hospitals, pharmacists, and other health professionals sued in response, and the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the payment cut.

In 2011, California Governor Jerry Brown again put the 10% cut in place, this time with approval from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In response, California physicians, led by the state medical association, sued California again. They argued that payment cuts reduce access to care among Medicaid beneficiaries by prompting physicians to stop accepting these patients. The California Department of Health Care Services countered that the cuts are necessary to offset a critical budget shortfall and will not affect access to care. The situation in California highlights the conflicts between physicians and many states over Medicaid payment rates.

The US Supreme Court agreed to review the case on only one question—whether individuals and private parties, including doctors and Medicaid recipients, can sue the state for failing to pay rates that meet the federal adequacy requirement. On October 3, 2011, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this group of cases, known as Douglas v. Independent Living Center of Southern California. ACOG joined the case in support of physicians.

Medicaid versus Medicare

It’s easy to see how important Medicaid is to women’s health, and how important physician payment rates are to women’s access to care. You might expect, then, that states would recognize the value of adequate physician payment—but they don’t, always.

At present, Medicaid pays for obstetric care at 93% of the Medicare rate. Still, obstetric care fares slightly better than many physician services. In many states, it costs physicians much more than Medicaid pays to provide non-obstetric care to Mediaid patients. Although 23 states pay for obstetric care at a rate lower than that offered by Medicare, 27 states offer greater support, and 16 states offer reimbursement well above the Medicare rate.

A federal target, too

The states aren’t the only entities with an eye on Medicaid cuts. The US Congress, too, is considering proposals to dramatically change the program. The options include issuing block grants for Medicaid; reducing the federal match; and including Medicaid in global or health spending caps. ACOG has an extensive campaign under way to ensure that any changes to Medicaid do not come at the expense of women’s health.

The Congressional Joint Special Committee on Deficit Reduction—more commonly known as the Supercommittee— represents the latest effort at deficit reduction. When its work imploded in December 2011, federal programs came online for a 2% across-the-board cut (“sequester”) that will take effect on January 1, 2013. The Medicaid program is exempt from this cut, no doubt in recognition of the already-precarious nature of this program, which has become a safety net for millions of American families struggling through the recession.

Because so many American women rely on Medicaid for obstetric and gynecologic care, it is critical that we protect funding levels and maintain eligibility for this program.

ACOG plays a prominent role in advocating for preservation of women’s access to care and adequate physician reimbursement levels. you can help by contacting your state legislators and representatives in the uS Congress to emphasize the importance of these efforts.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere (October 2011)

Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lucia DiVenere (July 2010)

Is the patient-centered medical home a win-all or lose-all proposition for ObGyns?

Janelle Yates (October 2010)

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Tough economic times have pushed 2.8 million more people onto Medicaid rolls, now crowded with more than 60 million low-income individuals and families—nearly 20% of the US population.

Because Medicaid is a means-tested entitlement program, states and the federal government must fund as much health care as beneficiaries use, an expense that increases substantially each year.

Through the Medicaid program, more than 30 million adult women have access to an annual gynecologic exam, family planning services, and prenatal care. Without such coverage, many of them would go without care, potentially driving our nation’s health-care costs even higher. Two thirds of ObGyns treat Medicaid patients, and Medicaid accounts for 18%, on average, of an ObGyn practice’s revenue.1

In this article, I describe how the burgeoning ranks of Medicaid beneficiaries are straining state budgets and prompting legislators to cut provider payments to make up the shortfall. The federal government also plays a role in shrinking reimbursements for physicians and other providers.

Medicaid costs are outpacing economic growth

In fiscal 2011, Medicaid enrollment grew an average of 5.5%, and states are anticipating a growth rate of 4.1% in 2012.2 Total Medicaid spending is also increasing rapidly. In fiscal 2010, it was $361.8 billion (excluding administrative costs)—a 6% increase over fiscal 2009. By the end of fiscal 2011, it was expected to hit $398.6 billion—a 10.1% increase over 2010.3

Medicaid costs are also absorbing a greater share of state budgets. In fiscal 2009, they accounted for 21.9% of total state expenditures, 22.3% in fiscal 2010, and 23.6% in fiscal 2011.3 Many states have had to reduce spending in other important areas as a result (TABLE 1).

Medicaid costs are shared by federal and state governments. The federal government pays, on average, 57% of state program costs. In fiscal 2010, the federal government covered 64.6% of all Medicaid costs.

State general funds at the end of 2011 were well below their pre-recession levels, due to lower revenues and increased expenditures, including continued obligations for state workers’ pensions and retiree health care. At the same time, 49 state governments are required to balance their budgets. As a result, states are likely to face austere budgets for at least the next several years, and will continue to make difficult spending decisions.

As state and federal budgets face pressure to reduce overall spending, Medicaid lies in nearly all budget crosshairs.

TABLE 1

Medicaid absorbs an ever-greater percentage of state expenditures

| State | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal 2009 | Fiscal 2010 | Fiscal 2011 | |

| New England | |||

| Connecticut | 27.9 | 25.4 | 27.2 |

| Maine | 29.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Massachusetts | 17.8 | 18.8 | 20.2 |

| New Hampshire | 26.5 | 24.9 | 25.2 |

| Rhode Island | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| Vermont | 25.5 | 25.9 | 26.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | |||

| Delaware | 12.3 | 14.4 | 16.2 |

| Maryland | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.6 |

| New Jersey | 19.8 | 21.3 | 21.9 |

| New york | 26.7 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 30.2 | 29.6 | 31.1 |

| Great Lakes | |||

| Illinois | 24.8 | 23.6 | 28.9 |

| Indiana | 21.8 | 23.1 | 24.4 |

| Michigan | 23.0 | 24.2 | 24.0 |

| Ohio | 20.6 | 21.3 | 23.2 |

| Wisconsin | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.0 |

| Plains | |||

| Iowa | 17.9 | 18.6 | 19.3 |

| Kansas | 17.4 | 18.8 | 18.6 |

| Minnesota | 24.0 | 25.1 | 25.1 |

| Missouri | 35.6 | 34.4 | 36.3 |

| Nebraska | 17.6 | 17.2 | 16.5 |

| North Dakota | 14.1 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| South Dakota | 21.6 | 21.7 | 23.2 |

| Southeast | |||

| Alabama | 25.6 | 25.8 | 25.3 |

| Arkansas | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 |

| Florida | 26.7 | 30.0 | 28.0 |

| Georgia | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.5 |

| Kentucky | 22.5 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| Louisiana | 22.0 | 23.7 | 23.5 |

| Mississippi | 24.8 | 22.9 | 22.6 |

| North Carolina | 25.0 | 24.2 | 22.1 |

| South Carolina | 22.0 | 22.6 | 19.9 |

| Tennessee | 25.4 | 28.8 | 28.1 |

| Virginia | 16.4 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| West Virginia | 11.9 | 12.6 | 13.0 |

| Southwest | |||

| Arizona | 29.3 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| New Mexico | 20.7 | 22.1 | 20.2 |

| Oklahoma | 17.7 | 17.1 | 18.5 |

| Texas | 22.8 | 24.6 | 26.3 |

| Rocky Mountain | |||

| Colorado | 14.1 | 15.3 | 19.4 |

| Idaho | 22.8 | 23.0 | 25.6 |

| Montana | 15.2 | 15.4 | 15.7 |

| Utah | 14.9 | 11.9 | 14.3 |

| Wyoming | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Far West | |||

| Alaska | 8.1 | 12.0 | 9.0 |

| California | 20.6 | 18.9 | 24.2 |

| Hawaii | 11.3 | 13.3 | 15.9 |

| Nevada | 16.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 |

| Oregon | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.6 |

| Washington | 21.4 | 23.0 | 24.4 |

| Average | 21.9 | 22.3 | 23.6 |

The fiscal health of Medicaid matters—here’s why

Twelve percent of women 18 to 64 years old rely on Medicaid for health-care coverage, and three quarters of all adult Medicaid beneficiaries are women. Sixty-nine percent of women in the 18- to 64-year-old age group are in their reproductive years. Medicaid pays for 42% of all births in the United States—as many as 64% of all births in Arkansas and Oklahoma.4

Medicaid covers essential well-woman care, including maternity care, breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment, care for disabled women, and family planning.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for contraception and sterilization services, covering 71% of these costs. States clearly find it in their best interest and the best interest of public health to encourage use of family planning, which can improve women’s health and reduce the number of unintended pregnancies and abortions. In 2010, 27 states extended family planning coverage to women whose incomes, while still low, were higher than the standard Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Many states cover nutrition and substance abuse counseling, health education, psychosocial counseling, breastfeeding, and case management. TABLE 2 on page 16a lists mandatory and optional Medicaid services.

TABLE 2

Benefits of the Medicaid program

| Mandatory | Optional |

|---|---|

| Physician services Laboratory and radiographic services Hospitalization Outpatient services Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services for people younger than 21 years Family planning Rural and federally qualified health center services Nurse midwife services Nursing facility services for people older than 21 years Home health care for people entitled to nursing facility care Smoking cessation for pregnant women* Free-standing birth center services* | Prescription drugs Clinic services Dental services, dentures Physical therapy and rehabilitation Prosthetic devices, eyeglasses Primary-care case management Intermediate-care facilities for the mentally retarded Inpatient psychiatric care for people younger than 21 years Home health care and other services provided under home- and community-based waivers Personal care services Hospice care Health home services for people with chronic conditions* Home- and community-based attendant services and supports* |

| * Benefits added under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | |

Coming: Another 4.5 million women on Medicaid rolls

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Medicaid will expand to cover another 4.5 million women in 2014. Beginning January 1, 2014, state Medicaid programs are required to cover nonpregnant, non-elderly individuals who have incomes as high as 133% of the federal poverty level ($10,890 for an individual in 2011). The federal government will cover the full expense of insuring these newly eligible individuals for calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016. Federal financing will phase down to 90% by 2020, and will likely decrease further after that.

States that participate in Medicaid must cover pregnant women who have an income at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. States are required to disregard 5% of an individual’s income when determining Medicaid eligibility, a rule that effectively brings the maximum eligibility level to 138% of the federal poverty level, opening the Medicaid doors to additional low-income individuals.

Today, coverage lasts throughout pregnancy and 2 months beyond. States may choose to extend eligibility to pregnant women who have incomes that exceed 133% of the poverty level; at present, 45 states do so, with the District of Columbia topping the list by covering pregnant women who have incomes at or below 300% of the poverty level.

Many measures show that Medicaid has improved access to health care for low- income women, saving lives and dollars. Your experience—wherever you practice— undoubtedly echoes that observation.

Prenatal care. You also know that prenatal care helps ensure healthy babies. Obstetric services often go beyond traditional medical needs to include a full spectrum of care that helps ensure a healthy pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period.

Of course, inadequate use of prenatal care is associated with increased risks of low birth weight, preterm birth, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and maternal mortality. Preterm births alone increase US health-care costs by $26 billion each year.5 Pregnancy-related maternal mortality is three to four times higher, and infant mortality is more than six times higher, among women who receive no prenatal care, compared with those who receive prenatal care.

Gynecologic services covered through Medicaid also help preserve health and reduce health-care costs. Eighty-four percent of women on Medicaid have had a Pap test in the past 2 years, compared with 80% of women who have private insurance and 59% of women who lack insurance.6 Routine gynecologic care is vital to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases. Women without a regular doctor don’t get regular Pap tests and mammography; nor do they get screened for other serious health risks, including high cholesterol and diabetes.

Despite the proven benefits of access to regular care, 23% of women on Medicaid report problems finding a new doctor who will accept their insurance, compared with 7% of Medicare beneficiaries and 13% of women who have private insurance.

Why the difficulty in finding a doctor? A leading reason is the inadequacy of Medicaid payment rates.

Cutting payments to physicians

Medicaid provider payments are often the first item cut in a state budget crisis. States are required to cover many health services and are restricted from charging patients significant co-pays, so they often trim budgets at the expense of physicians. Thirty-nine states reduced physician and provider payments in 2011, and 46 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012. In addition, in fiscal 2011, 47 states put in place at least one new policy to control Medicaid costs; most states implemented several of these policies. All 50 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012.

Under federal rules, states must ensure that payment rates are consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. They also must ensure that payment is sufficient to enlist enough providers to render care and services to the same extent that care and services are available to the general population in the same geographic area. States must request and receive permission from the federal government before reducing provider payment rates. However, even with this safeguard in place, physician payments—and patient access to care—are in jeopardy.

For example, in 2008, the California legislature issued several rounds of cuts, including a 10% cut in physician and provider payments, to make up for budget shortfalls. Physicians, hospitals, pharmacists, and other health professionals sued in response, and the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the payment cut.

In 2011, California Governor Jerry Brown again put the 10% cut in place, this time with approval from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In response, California physicians, led by the state medical association, sued California again. They argued that payment cuts reduce access to care among Medicaid beneficiaries by prompting physicians to stop accepting these patients. The California Department of Health Care Services countered that the cuts are necessary to offset a critical budget shortfall and will not affect access to care. The situation in California highlights the conflicts between physicians and many states over Medicaid payment rates.

The US Supreme Court agreed to review the case on only one question—whether individuals and private parties, including doctors and Medicaid recipients, can sue the state for failing to pay rates that meet the federal adequacy requirement. On October 3, 2011, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this group of cases, known as Douglas v. Independent Living Center of Southern California. ACOG joined the case in support of physicians.

Medicaid versus Medicare

It’s easy to see how important Medicaid is to women’s health, and how important physician payment rates are to women’s access to care. You might expect, then, that states would recognize the value of adequate physician payment—but they don’t, always.

At present, Medicaid pays for obstetric care at 93% of the Medicare rate. Still, obstetric care fares slightly better than many physician services. In many states, it costs physicians much more than Medicaid pays to provide non-obstetric care to Mediaid patients. Although 23 states pay for obstetric care at a rate lower than that offered by Medicare, 27 states offer greater support, and 16 states offer reimbursement well above the Medicare rate.

A federal target, too

The states aren’t the only entities with an eye on Medicaid cuts. The US Congress, too, is considering proposals to dramatically change the program. The options include issuing block grants for Medicaid; reducing the federal match; and including Medicaid in global or health spending caps. ACOG has an extensive campaign under way to ensure that any changes to Medicaid do not come at the expense of women’s health.

The Congressional Joint Special Committee on Deficit Reduction—more commonly known as the Supercommittee— represents the latest effort at deficit reduction. When its work imploded in December 2011, federal programs came online for a 2% across-the-board cut (“sequester”) that will take effect on January 1, 2013. The Medicaid program is exempt from this cut, no doubt in recognition of the already-precarious nature of this program, which has become a safety net for millions of American families struggling through the recession.

Because so many American women rely on Medicaid for obstetric and gynecologic care, it is critical that we protect funding levels and maintain eligibility for this program.

ACOG plays a prominent role in advocating for preservation of women’s access to care and adequate physician reimbursement levels. you can help by contacting your state legislators and representatives in the uS Congress to emphasize the importance of these efforts.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2008 Socioeconomic Survey of ACOG Fellows. Washington DC: ACOG; 2008.

2. Holahan J, Headen I. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State-by-State Results for Adults at or Below 133% FPL. Washington DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010.

3. National Association of State Budget Officers. State Expenditure Report 2010. Washington DC: NASBO; December 2011.

4. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. 2010 Maternal and Child Health Update. Issue Brief. Washington DC: National Governors Association; 2011. http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF. Accessed January 12, 2011.

5. Behrman RE, Butler AS. eds Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Women’s Health Survey 2004. Washington DC: KFF; 2005.

1. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2008 Socioeconomic Survey of ACOG Fellows. Washington DC: ACOG; 2008.

2. Holahan J, Headen I. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State-by-State Results for Adults at or Below 133% FPL. Washington DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010.

3. National Association of State Budget Officers. State Expenditure Report 2010. Washington DC: NASBO; December 2011.

4. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. 2010 Maternal and Child Health Update. Issue Brief. Washington DC: National Governors Association; 2011. http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF. Accessed January 12, 2011.

5. Behrman RE, Butler AS. eds Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Women’s Health Survey 2004. Washington DC: KFF; 2005.

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

- Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2011) - 14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

Lucia DiVenere, ACOG Director of Government Affairs, with OBG MANAGEMENT Senior Editor Janelle Yates (June 2010)

In the 18 months since the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act—otherwise known as ACA, or health-care reform—was signed into law by President Barack Obama, the outlook for private practice, in any specialty, has dimmed. As a recent report on the ramifications of the ACA put it:

The imperative to care for more patients, to provide higher perceived quality, at less cost, with increased reporting and tracking demands, in an environment of high potential liability and problematic reimbursement, will put additional stress on physicians, particularly those in private practice.1

To explore the impact of these stresses on ObGyns specifically, the editors of OBG Management invited Lucia DiVenere, Senior Director of Government Affairs for the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), to talk about the outlook for private practice in the coming years. In the exchange, Ms. DiVenere discusses the short- and long-term effects of the ACA, the ways in which ObGyn practice is (or is not) evolving, the challenge of making the switch to electronic health records (EHRs), the reasons ACOG opposed the ACA, and other issues related to the current practice environment. In addition, two ObGyns in private practice describe the many challenges they face (see “The view from private practice,” pages 44 and 52).

What nonlegislative forces have affected private practice?

OBG Management: A recent report on the ramifications of the ACA argues that formal reform was inevitable. It also asserts that private practice was subject to many negative pressures long before health-care reform was passed.1 Do you agree?

Ms. DiVenere: Our nation’s health-care system is always evolving, and over the past decade, we’ve seen a clear trend toward system integration—that is, larger, physician-led group practices and hospital employment of physicians.

Looking at physicians as a whole, the percentage who practice solo or in two-physician practices fell from 40.7% in 1996–97 to 32.5% by 2004–05, according to a 2007 survey.2 And the American Medical Association (AMA) reported that the percentage of physicians “with an ownership stake in their practice declined from 61.6% to 54.4% as more physicians opted for employment. Both the trends away from solo and two-physician practices and toward employment were more pronounced for specialists and older physicians.”2

OBG Management: What has the trend been for ObGyns, specifically?

Ms. DiVenere: The ObGyn specialty employs the group practice model—health care delivered by three or more physicians—more frequently than other specialties do, largely because of the support it provides for 24–7 OB call schedules.

As for private practice, ObGyns have been moving away from it for 10 years or longer. Data from a 1991 ACOG survey shows that 77% of respondents were in private practice; by 2003, that percentage had fallen to 70%.3 In 2003, ObGyns in private practice tended to be older (median age: 47 years) than their salaried colleagues (median: 42 years) and were more likely to be male (87% vs 77%).3 The demographic change toward women ObGyns may add to this trend line.

OBG Management: What economic forces have shaped practice paradigms in ObGyn?

Ms. DiVenere: Median expenses for private practices have been steadily rising in relation to revenues—from 52% in 1990 to 71% in 2002—making it difficult for practices to remain solvent.4 In addition, a 2011 survey from Medscape reveals that ObGyns in solo practice earn $15,000 to $25,000 less annually than their employed colleagues.5

ObGyns who have made the switch from private to hospital practice, or who have become ObGyn hospitalists, often point to the difficulties of maintaining a solvent private practice, especially given the push toward electronic health records (EHRs) and increasing regulatory and administrative burdens. These and other issues contribute to rising practice costs and increasing demands on an ObGyn’s time and attention.

“I still love what I do”

I’ve been in solo ObGyn practice for 10 years. Before that, I worked 10 years for two medical groups—that makes 20 years of medical practice. I entered medicine late after teaching school for 10 years.

Most of my patients used to have union jobs and were employed by the steel mills in south Chicago and Northwest Indiana or in construction or manufacturing. One of the benefits of a union job was good insurance. As the economy began to sour, those mills changed hands and are now owned largely by foreign companies. Wages were cut dramatically, and insurance benefits are now “bare bones.” I continue to see my patients regardless of their circumstances.

Most maternity benefits require a hefty out-of-pocket expense. Around here, the doctor gets stuck with the deductible and, consequently, ends up doing lots of free deliveries. I haven’t figured it out yet, but I’m willing to bet that I lose money on OB.

Most patients realize that it’s tough to run a business on a declining revenue stream and are grateful that I take care of them. I’ve treated many of their family members, delivered their babies, provided primary care, done prolapse repairs on mom and grandmom. I know everybody by name—that’s the school teacher in me. I still feel honored to do what I do, but it isn’t easy. The other docs who cover for me on my rare days off, for CME, tell me I have “a nice practice.” That’s why I do it, for the good, salt-of-the-earth folks who would like to pay their bills if times were better.

Medicine is changing quickly. It has taken time to learn the electronic health record (EHR) at the local hospital. Every documentation takes longer. I now spend more time at the computer desk than with patients on hospital rounds. I have read about accountable care organizations and being “enabled,” but the next round of payment cuts will likely kill private practice.

I have Indiana University medical students come and rotate with me, and I try to be as upbeat as I can. The students tell me that my office is the one everyone wants to rotate through. I used to hope that someone might come back and join me here—but maybe the young people have it right. They won’t live with a pager all the time. They won’t do call. To them, medicine will be a job. They will be “providers.”

I may not have practiced in the golden age of medicine, but at least I feel that I had an impact on the lives of the families I have been honored to serve. I still love what I do—it’s just getting harder to justify doing it.

—Mary Vanko, MD

Munster, Ind.

What are the short-term effects of formal reform?

OBG Management: What effect has health-care reform had so far?

Ms. DiVenere: In 2010, twice as many physician practices were bought by hospitals and health systems as in 2009. We can’t conclude that the 2010 law is responsible for these changes, but we know that the architects of health reform were aware of this trend, believed it was beneficial, and looked for ways to encourage it, including through development of accountable care organizations (ACOs), which give hospitals a new and potentially lucrative reason to purchase private practices.

OBG Management: What exactly is an ACO?

Ms. DiVenere: An ACO consists of aligned providers—most likely, large multispecialty groups, often affiliated with the same hospital—who agree to manage patients for a set fee, sharing the risk and potential profit. ACOs are required to have shared governance, which gives them the authority to impose standards for practice, reporting, and compensation—including rewards and penalties—across a group of physicians.

Each ACO must sign a 3-year contract with the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and include a sufficient number of primary care professionals to care for at least 5,000 beneficiaries. ACOs will be evaluated by quality-performance measures to be determined by the Secretary of HHS.

What aspects of ACA will have the biggest impact?

OBG Management: What provision of the new law will have the most direct impact on ObGyns in private practice?

Ms. DiVenere: All ObGyns may benefit from the guarantee of insurance coverage for our patients for maternity and preventive care. And all ObGyns should join ACOG’s fight to repeal the Independent Payment Advisory Board, which may hold enormous power to cut physician reimbursement.

Here’s the quote all ObGyns—especially those in private practice—should read, from an article written by President Obama’s health-reform deputies:

To realize the full benefits of the Affordable Care Act, physicians will need to embrace rather than resist change. The economic forces put in motion by the Act are likely to lead to vertical organization of providers and accelerate physician employment by hospitals and aggregation into larger physician groups. The most successful physicians will be those who most effectively collaborate with other providers to improve outcomes, care productivity, and patient experience.6

OBG Management: Do these health-reform deputies offer any concrete vision of how this change will be achieved?

Ms. DiVenere: They detail what physicians need to do, and how they should change the way they practice, under the Act. For example, to meet the increasing demand for health care, they recommend that practices:

- “Redesign care to include a team of nonphysician providers, such as nurse practitioners, physician assistants, care coordinators, and dieticians”

- “Develop approaches to engage and monitor patients outside of the office.”6

And to meet the requirements for payment reform, information transparency, and quality, they suggest that practices:

- “Focus care around exceptional patient experience and shared clinical outcome goals”

- “Engage in shared decision-making discussions regarding treatment goals and approaches”

- “Proactively manage preventive care”

- “Establish teams to take part in bundled payments and incentive programs”

- “Expand use of electronic health records”

- “Collaborate with hospitals to dramatically reduce readmissions and hospital-acquired infections”

- “Incorporate patient-centered outcomes research to tailor care.”6

To capture value, the authors recommend that practices “redesign medical office processes to capture savings from administrative simplification.”6

OBG Management: Do they propose any method for implementing these changes?

Ms. DiVenere: The White House is hoping that ACOs can lead. Medicare ACOs will attempt to accomplish these changes by managing hospital and physician services, prompting physicians and hospitals to change how they are both clinically organized and paid for services—this change, in particular, is considered by some to be essential to improving the quality and efficiency of health care.

The new Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) Innovation Center, created by the ACA, is given broad authority to test, evaluate, and adopt systems that foster patient-centered care, improve quality, and contain the costs of Medicare, Medicaid, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). The law specifically guides the Innovation Center to look for ways to encourage physicians to transition from fee-for-service to salary-based payment.

We can safely assume that the experts behind these provisions believe that large, hospital-centered systems or large, physician-led groups can better serve the needs of patients and our health-care system in general than can small private practices. Today, 24% of ObGyns run solo practices, and 27% are in single-specialty practices. Health-care reform can mean big changes for them.

Is the EHR a realistic goal for private practices?

OBG Management: How does the push for EHRs affect physicians in private practice?

Ms. DiVenere: Very profoundly. From the point of view of an ObGyn in private practice, EHRs offer a number of benefits. They can:

- help make sense of our increasingly fragmented health-care system

- improve patient safety

- increase efficiency

- reduce paperwork.

In addition, insurers may save by reducing unnecessary tests, and patients can certainly benefit from better coordination and documentation of care. These advantages don’t necessarily translate into savings or revenue for physician practices, however. Many ObGyns—especially those in solo or small practices—don’t feel confident making such a large capital investment. In fact, only about one third of ObGyn practices have an EHR.

OBG Management: Is it primarily cost that deters ObGyns from adopting EHRs?

Ms. DiVenere: That, and the fact that EHR systems are not yet fully interoperable across small practices, insurers, and government agencies. The initial cost of purchasing an EHR system for a small practice is about $50,000 per physician, and there are ongoing costs in staff training and hardware and software updates. A steep learning curve means fewer patients can be seen in an hour. It can take a practice months—even years—for physicians to return to their previous level of productivity. That’s a lot to ask a busy practicing physician to take on.

OBG Management: Is there any way around the push for EHRs?

Ms. DiVenere: Congress wants to move us to full adoption of health information technology (HIT). Under health-care reform, beginning in 2013, all health insurance plans must comply with a uniform standard for electronic transactions, including eligibility verification and health claim status.

In 2014, uniform standards must:

- allow automatic reconciliation of electronic funds transfers and HIPAA payment and remittance

- use standardized and consistent methods of health plan enrollment and editing of claims

- use unique health plan identifiers to simplify and improve routing of health-care transactions

- use standardized claims attachments

- improve practice data collection and evaluation.

Uniformity and standardization can help address one of the major roadblocks to physician adoption of HIT. Still, it’s little wonder that median expenses for private practices have been steadily rising in relation to revenues.

So far, the cons of an EHR outweigh the pros

My private practice made the transition to electronic health records (EHRs) about 4 months ago. We have discovered that EHRs do have a number of positive characteristics:

- Prescriptions are completely legible and can be sent directly to the pharmacy

- The staff no longer needs to search for charts

- If test results have been downloaded, they can be quickly accessed.

However, EHRs also require a lot of time to learn how to use them properly. And the problems don’t end there. For example, instead of looking at a patient’s face when taking a history, we now look at the monitor.

In addition, the templates have many data fields that auto-populate as “normal.” There is an illusion that a thorough history and physical were performed—so it requires a lot of time meticulously reviewing each chart to make sure that it is accurate. One must always be aware of the potential for insurance fraud and the medicolegal risk of documenting something as normal when it isn’t.

Ordering labs is cumbersome because each test must be handled separately, and the terminology does not always match the options at our contracted laboratories. We spend a lot of time searching for each lab that is ordered.

To achieve “meaningful use” of the EHR, certain parameters must be met at every single visit. The medication list must be reviewed (even if the patient takes no medications), and there must be a notation that cervical and breast cancer screening have been ordered, even though recent Pap smear and mammogram results are included in the chart. Regardless of the patient’s age or situation, the issues of contraception, sexually transmitted disease, tobacco use, and domestic violence must be addressed.

So when a 65-year-old woman presents with postmenopausal bleeding, I have to comment on these issues or delete them from the report. I have to provide the same documentation when she returns the next week for a biopsy and the week after that when she returns for the results.

It has become impossible to see patients in the time frame I have used for the past 24 years, and my patients and staff remain frustrated. I am always behind schedule, and I fear that the computer gets more attention than my patients do during the office visit.

—Mark A. Firestone, MD

Aventura, Fla

Is there a physician shortage in ObGyn?

OBG Management: There has been a lot of attention focused on the shortage of physicians in this country. How severe is the shortage likely to be in the specialty of ObGyn?

Ms. DiVenere: William F. Rayburn, MD, MBA, from the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center and School of Medicine in Albuquerque, has provided ACOG with important work on this topic. Dr. Rayburn is Randolph V. Seligman Professor and Chair in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at that institution. His report7 shows that the gap between the supply of ObGyns and the demand for women’s health care is widening.

Data from this report point to a shortage of 9,000 to 14,000 ObGyns in 20 years. After 2030, the ObGyn shortage may be even more pronounced, as the population of women is projected to increase 36% by 2050, while the number of ObGyns remains constant.

OBG Management: Would the incorporation of more midlevel providers—that is, nurse midwives, physician assistants, and others—ease some of the strains on the ObGyn workforce in general and on private practice specifically?

Ms. DiVenere: That’s very possible and is one of the reasons ACOG encourages greater use of collaborative care. It’s certainly true that the ObGyn specialty is historically comfortable with collaboration.

In 2008, the average ObGyn practice employed 2.6 nonphysician clinicians, certified nurse midwives (CNMs), physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. ACOG strongly supports collaborative practice between ObGyns and qualified midwives (CNMs, certified midwives) and other nonphysician clinicians.

In a recent issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology, ACOG’s Immediate Past President Richard N. Waldman, MD, and Holly Powell Kennedy, CNM, PhD, president of the American College of Nurse Midwives, wrote about the importance of collaborative practice, which can “increase efficiency, improve clinical outcomes, and enhance provider satisfaction.”8 The September 2011 issue of Obstetrics & Gynecology highlights four real-life stories of successful collaborative practice.

Because of our commitment to the benefits of collaborative practice, ACOG supported a provision in the ACA that increases payment for CNMs. Beginning this year, the Medicare program will reimburse CNMs at 100% of the physician payment rate for the same services. Before this law, CNMs were paid at 65% of a physician’s rate for the same services. ACOG’s leadership believes that better reimbursement for CNMs will help ObGyn practices and improve care.

Although ACOG supported that provision in the law, we did not support passage of the ACA. ACOG’s Executive Board carefully considered all elements of the bill and decided that, although it included many provisions that are helpful to our patients, it also included many harmful provisions for our members. We felt that the promise of the women’s health provisions could be realized only if the legislation worked for practicing physicians, too.

Why wasn’t the SGR formula abolished?

OBG Management: What is the effect, for physicians in general and ObGyns in private practice specifically, of the failure to fix the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula and implement liability reform in the ACA?

Ms. DiVenere: The fact that we have no fix for SGR and no medical liability reform is a disgrace. And the absence of solutions to these two issues is one of the main reasons ACOG decided not to support passage of the ACA. Our Executive Board was very clear in telling Congress that we can’t build a reformed health-care system on broken payment and liability systems—it just won’t work.

ObGyns themselves are the first to point out this fact. ObGyns listed medical liability (65.3%) and financial viability of their practice (44.3%) as their top two professional concerns in a 2008 ACOG survey.9

For all ObGyns, these two continuing problems make practice more difficult every day—problems felt most acutely by ObGyns in private practice. Employed physicians often come under a hospital’s or health system’s liability policy and often don’t pay their own premiums. Employed physicians usually are on salary, sheltering them from the vagaries of Congressional action, or inaction, on looming double-digit Medicare physician payment cuts under the SGR.

Some legislators, and some ObGyns, think Medicare doesn’t apply to us. But today, 92% of ObGyns participate in the Medicare program and 63% accept all Medicare patients. This fact reflects ObGyn training and commitment to serve as lifelong principal-care physicians for women, including women who have disabilities. Fifty-six percent of all Medicare beneficiaries are women. With the Baby Boomer generation transitioning to Medicare, and with shortages in primary care physicians, it is likely that ObGyns will become more involved in delivering health care for this population.

Medicare physician payments matter to ObGyns beyond the Medicare program, too, as Tricare and private payers often follow Medicare payment and coverage policies. As a specialty, we have much at stake in ensuring a stable Medicare system for years to come, starting with an improved physician payment system. [Editor’s note: See Dr. Robert L. Barbieri’s editorial on the subject.]

OBG Management: What is ACOG doing to improve this system?

Ms. DiVenere: ACOG is urging the US Congress to ensure that a better system adheres to the following priniciples:

- Medicare payments should fairly and accurately reflect the cost of care. In the final 2011 Medicare physician fee schedule, CMS is proposing to reduce the physician work value for ObGyn care to women by 11% below what is paid to other physicians for similar men’s services—exactly the opposite of what should be done to encourage good care coordination, and in direct contradiction to recommendations by the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale Update Committee (RUC). Medicare payments to obstetricians are already well below the cost of maternity care; no further cuts should be allowed for this care.

- A new payment system should be as simple, coordinated, and transparent as possible and recognize that there is no one-size-fits-all model. A new Medicare system should coordinate closely with other governmental and nongovernmental programs to ensure that information technology is interoperable, that quality measurement relies on high-quality, risk-adjusted data, and to guard against new and special systems that apply to only one program or may only be workable for one type of specialty or only certain types of diseases and conditions. ObGyns often see relatively few Medicare patients, and unique Medicare requirements can pose significant administrative challenges and inefficiencies to ObGyn participation.

- Congress should encourage, and remove barriers to, ObGyn and physician development of ACOs, medical homes for women, and other innovative models. Proposed rules on the Medicare Shared Savings Program allowing for expedited antitrust review should be extended to ACOs and other physician-led models of care that do not participate in the Medicare Shared Savings Program. These models should also recognize the dual role ObGyns may play, as both primary and specialty care providers.

- Congress should repeal the Independent Medicare Payment Advisory Board. Leaving Medicare payment decisions in the hands of an unelected, unaccountable body with minimal congressional oversight is bad for all physicians and for our patients.

The outlook for private practice, in any specialty, has dimmed. Says ACOG’s Lucia DiVenere: “Median expenses for private practices have been steadily rising in relationship to revenues—from 52% in 1990 to 71% in 2002—making it difficult for practices to remain solvent.”

Is private practice doomed?

OBG Management: In your opinion, over the long term, is health reform a positive or a negative for ObGyns in private practice?

Ms. DiVenere: On balance, I believe that the health reform law is a positive for our patients, and that fact may lead to an eventual positive for its Fellows, ACOG hopes. What it may mean for ObGyns in private practice, though, is more troubling.

The law has many intended purposes: 1) cover the uninsured, 2) tilt our health-care system toward primary care and use of nonphysician providers, and 3) push practices toward integration with hospitals and health systems and other paths to physician employment. Support for continuation or growth in any type of physician private practice is hard to find in the ACA.

OBG Management: What changes are in the pipeline?

Ms. DiVenere: Under the ACA, by 2013, the Secretary of HHS, with input from stakeholders, will set up a Physician Compare Web site, modeled after the program that exists for hospitals, using data from the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI). Data on this site would be made public on January 1, 2013, comparing physicians in terms of quality of care and patient experience.

By law, these data are intended to be statistically valid and risk-adjusted; each physician must have time to review his or her information before it becomes publicly available; data must ensure appropriate attribution of care when multiple providers are involved; and the Secretary of HHS must give physicians timely performance feedback.

Data elements—to the extent that scientifically sound measures exist—will include:

- quality, patient satisfaction, and health outcomes information on Medicare physicians

- physician care coordination and risk-adjusted resource use

- safety, effectiveness, and timeliness of care.

Physicians who successfully interact with this program will likely be those who have a robust EHR system.

If this and other elements of the Affordable Care Act become real, however, we’ll likely see a fundamental shift in the kinds of settings in which ObGyns and other physicians opt to practice.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Physicians Foundation. Health Reform and the Decline of Physician Private Practice. Boston Mass: Physicians Foundation; 2010.

2. American Medical Association. Health Care Trends 2008. http://www.ama-assn.org/resources/doc/clrpd/2008-trends.pdf. Accessed September 1 2011.

3. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Profile of ObGyn Practice. Washington DC: ACOG; 2003.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Financial Trends in ObGyn Practice 1990–2002. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2004:6.

5. Medscape Physician Compensation Report: 2011 Results. . Accessed September 1 2011.

6. Kocher R, Emanuel EJ, DeParle NA. The Affordable Care Act and the future of clinical medicine: the opportunities and challenges. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153(8):536-539.

7. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The Obstetrician-Gynecologist Workforce in the United States: Facts Figures, and Implications 2011. Washington, DC: ACOG; 2011.