User login

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere (October 2011)

Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lucia DiVenere (July 2010)

Is the patient-centered medical home a win-all or lose-all proposition for ObGyns?

Janelle Yates (October 2010)

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Tough economic times have pushed 2.8 million more people onto Medicaid rolls, now crowded with more than 60 million low-income individuals and families—nearly 20% of the US population.

Because Medicaid is a means-tested entitlement program, states and the federal government must fund as much health care as beneficiaries use, an expense that increases substantially each year.

Through the Medicaid program, more than 30 million adult women have access to an annual gynecologic exam, family planning services, and prenatal care. Without such coverage, many of them would go without care, potentially driving our nation’s health-care costs even higher. Two thirds of ObGyns treat Medicaid patients, and Medicaid accounts for 18%, on average, of an ObGyn practice’s revenue.1

In this article, I describe how the burgeoning ranks of Medicaid beneficiaries are straining state budgets and prompting legislators to cut provider payments to make up the shortfall. The federal government also plays a role in shrinking reimbursements for physicians and other providers.

Medicaid costs are outpacing economic growth

In fiscal 2011, Medicaid enrollment grew an average of 5.5%, and states are anticipating a growth rate of 4.1% in 2012.2 Total Medicaid spending is also increasing rapidly. In fiscal 2010, it was $361.8 billion (excluding administrative costs)—a 6% increase over fiscal 2009. By the end of fiscal 2011, it was expected to hit $398.6 billion—a 10.1% increase over 2010.3

Medicaid costs are also absorbing a greater share of state budgets. In fiscal 2009, they accounted for 21.9% of total state expenditures, 22.3% in fiscal 2010, and 23.6% in fiscal 2011.3 Many states have had to reduce spending in other important areas as a result (TABLE 1).

Medicaid costs are shared by federal and state governments. The federal government pays, on average, 57% of state program costs. In fiscal 2010, the federal government covered 64.6% of all Medicaid costs.

State general funds at the end of 2011 were well below their pre-recession levels, due to lower revenues and increased expenditures, including continued obligations for state workers’ pensions and retiree health care. At the same time, 49 state governments are required to balance their budgets. As a result, states are likely to face austere budgets for at least the next several years, and will continue to make difficult spending decisions.

As state and federal budgets face pressure to reduce overall spending, Medicaid lies in nearly all budget crosshairs.

TABLE 1

Medicaid absorbs an ever-greater percentage of state expenditures

| State | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal 2009 | Fiscal 2010 | Fiscal 2011 | |

| New England | |||

| Connecticut | 27.9 | 25.4 | 27.2 |

| Maine | 29.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Massachusetts | 17.8 | 18.8 | 20.2 |

| New Hampshire | 26.5 | 24.9 | 25.2 |

| Rhode Island | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| Vermont | 25.5 | 25.9 | 26.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | |||

| Delaware | 12.3 | 14.4 | 16.2 |

| Maryland | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.6 |

| New Jersey | 19.8 | 21.3 | 21.9 |

| New york | 26.7 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 30.2 | 29.6 | 31.1 |

| Great Lakes | |||

| Illinois | 24.8 | 23.6 | 28.9 |

| Indiana | 21.8 | 23.1 | 24.4 |

| Michigan | 23.0 | 24.2 | 24.0 |

| Ohio | 20.6 | 21.3 | 23.2 |

| Wisconsin | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.0 |

| Plains | |||

| Iowa | 17.9 | 18.6 | 19.3 |

| Kansas | 17.4 | 18.8 | 18.6 |

| Minnesota | 24.0 | 25.1 | 25.1 |

| Missouri | 35.6 | 34.4 | 36.3 |

| Nebraska | 17.6 | 17.2 | 16.5 |

| North Dakota | 14.1 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| South Dakota | 21.6 | 21.7 | 23.2 |

| Southeast | |||

| Alabama | 25.6 | 25.8 | 25.3 |

| Arkansas | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 |

| Florida | 26.7 | 30.0 | 28.0 |

| Georgia | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.5 |

| Kentucky | 22.5 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| Louisiana | 22.0 | 23.7 | 23.5 |

| Mississippi | 24.8 | 22.9 | 22.6 |

| North Carolina | 25.0 | 24.2 | 22.1 |

| South Carolina | 22.0 | 22.6 | 19.9 |

| Tennessee | 25.4 | 28.8 | 28.1 |

| Virginia | 16.4 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| West Virginia | 11.9 | 12.6 | 13.0 |

| Southwest | |||

| Arizona | 29.3 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| New Mexico | 20.7 | 22.1 | 20.2 |

| Oklahoma | 17.7 | 17.1 | 18.5 |

| Texas | 22.8 | 24.6 | 26.3 |

| Rocky Mountain | |||

| Colorado | 14.1 | 15.3 | 19.4 |

| Idaho | 22.8 | 23.0 | 25.6 |

| Montana | 15.2 | 15.4 | 15.7 |

| Utah | 14.9 | 11.9 | 14.3 |

| Wyoming | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Far West | |||

| Alaska | 8.1 | 12.0 | 9.0 |

| California | 20.6 | 18.9 | 24.2 |

| Hawaii | 11.3 | 13.3 | 15.9 |

| Nevada | 16.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 |

| Oregon | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.6 |

| Washington | 21.4 | 23.0 | 24.4 |

| Average | 21.9 | 22.3 | 23.6 |

The fiscal health of Medicaid matters—here’s why

Twelve percent of women 18 to 64 years old rely on Medicaid for health-care coverage, and three quarters of all adult Medicaid beneficiaries are women. Sixty-nine percent of women in the 18- to 64-year-old age group are in their reproductive years. Medicaid pays for 42% of all births in the United States—as many as 64% of all births in Arkansas and Oklahoma.4

Medicaid covers essential well-woman care, including maternity care, breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment, care for disabled women, and family planning.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for contraception and sterilization services, covering 71% of these costs. States clearly find it in their best interest and the best interest of public health to encourage use of family planning, which can improve women’s health and reduce the number of unintended pregnancies and abortions. In 2010, 27 states extended family planning coverage to women whose incomes, while still low, were higher than the standard Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Many states cover nutrition and substance abuse counseling, health education, psychosocial counseling, breastfeeding, and case management. TABLE 2 on page 16a lists mandatory and optional Medicaid services.

TABLE 2

Benefits of the Medicaid program

| Mandatory | Optional |

|---|---|

| Physician services Laboratory and radiographic services Hospitalization Outpatient services Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services for people younger than 21 years Family planning Rural and federally qualified health center services Nurse midwife services Nursing facility services for people older than 21 years Home health care for people entitled to nursing facility care Smoking cessation for pregnant women* Free-standing birth center services* | Prescription drugs Clinic services Dental services, dentures Physical therapy and rehabilitation Prosthetic devices, eyeglasses Primary-care case management Intermediate-care facilities for the mentally retarded Inpatient psychiatric care for people younger than 21 years Home health care and other services provided under home- and community-based waivers Personal care services Hospice care Health home services for people with chronic conditions* Home- and community-based attendant services and supports* |

| * Benefits added under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | |

Coming: Another 4.5 million women on Medicaid rolls

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Medicaid will expand to cover another 4.5 million women in 2014. Beginning January 1, 2014, state Medicaid programs are required to cover nonpregnant, non-elderly individuals who have incomes as high as 133% of the federal poverty level ($10,890 for an individual in 2011). The federal government will cover the full expense of insuring these newly eligible individuals for calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016. Federal financing will phase down to 90% by 2020, and will likely decrease further after that.

States that participate in Medicaid must cover pregnant women who have an income at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. States are required to disregard 5% of an individual’s income when determining Medicaid eligibility, a rule that effectively brings the maximum eligibility level to 138% of the federal poverty level, opening the Medicaid doors to additional low-income individuals.

Today, coverage lasts throughout pregnancy and 2 months beyond. States may choose to extend eligibility to pregnant women who have incomes that exceed 133% of the poverty level; at present, 45 states do so, with the District of Columbia topping the list by covering pregnant women who have incomes at or below 300% of the poverty level.

Many measures show that Medicaid has improved access to health care for low- income women, saving lives and dollars. Your experience—wherever you practice— undoubtedly echoes that observation.

Prenatal care. You also know that prenatal care helps ensure healthy babies. Obstetric services often go beyond traditional medical needs to include a full spectrum of care that helps ensure a healthy pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period.

Of course, inadequate use of prenatal care is associated with increased risks of low birth weight, preterm birth, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and maternal mortality. Preterm births alone increase US health-care costs by $26 billion each year.5 Pregnancy-related maternal mortality is three to four times higher, and infant mortality is more than six times higher, among women who receive no prenatal care, compared with those who receive prenatal care.

Gynecologic services covered through Medicaid also help preserve health and reduce health-care costs. Eighty-four percent of women on Medicaid have had a Pap test in the past 2 years, compared with 80% of women who have private insurance and 59% of women who lack insurance.6 Routine gynecologic care is vital to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases. Women without a regular doctor don’t get regular Pap tests and mammography; nor do they get screened for other serious health risks, including high cholesterol and diabetes.

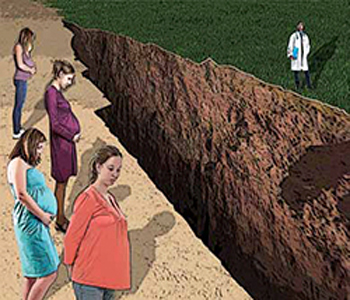

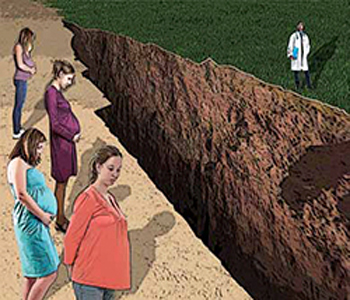

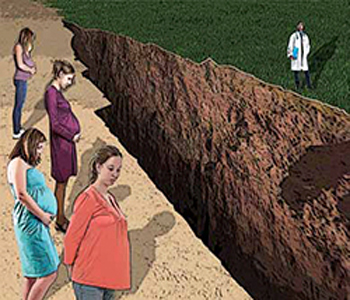

Despite the proven benefits of access to regular care, 23% of women on Medicaid report problems finding a new doctor who will accept their insurance, compared with 7% of Medicare beneficiaries and 13% of women who have private insurance.

Why the difficulty in finding a doctor? A leading reason is the inadequacy of Medicaid payment rates.

Cutting payments to physicians

Medicaid provider payments are often the first item cut in a state budget crisis. States are required to cover many health services and are restricted from charging patients significant co-pays, so they often trim budgets at the expense of physicians. Thirty-nine states reduced physician and provider payments in 2011, and 46 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012. In addition, in fiscal 2011, 47 states put in place at least one new policy to control Medicaid costs; most states implemented several of these policies. All 50 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012.

Under federal rules, states must ensure that payment rates are consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. They also must ensure that payment is sufficient to enlist enough providers to render care and services to the same extent that care and services are available to the general population in the same geographic area. States must request and receive permission from the federal government before reducing provider payment rates. However, even with this safeguard in place, physician payments—and patient access to care—are in jeopardy.

For example, in 2008, the California legislature issued several rounds of cuts, including a 10% cut in physician and provider payments, to make up for budget shortfalls. Physicians, hospitals, pharmacists, and other health professionals sued in response, and the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the payment cut.

In 2011, California Governor Jerry Brown again put the 10% cut in place, this time with approval from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In response, California physicians, led by the state medical association, sued California again. They argued that payment cuts reduce access to care among Medicaid beneficiaries by prompting physicians to stop accepting these patients. The California Department of Health Care Services countered that the cuts are necessary to offset a critical budget shortfall and will not affect access to care. The situation in California highlights the conflicts between physicians and many states over Medicaid payment rates.

The US Supreme Court agreed to review the case on only one question—whether individuals and private parties, including doctors and Medicaid recipients, can sue the state for failing to pay rates that meet the federal adequacy requirement. On October 3, 2011, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this group of cases, known as Douglas v. Independent Living Center of Southern California. ACOG joined the case in support of physicians.

Medicaid versus Medicare

It’s easy to see how important Medicaid is to women’s health, and how important physician payment rates are to women’s access to care. You might expect, then, that states would recognize the value of adequate physician payment—but they don’t, always.

At present, Medicaid pays for obstetric care at 93% of the Medicare rate. Still, obstetric care fares slightly better than many physician services. In many states, it costs physicians much more than Medicaid pays to provide non-obstetric care to Mediaid patients. Although 23 states pay for obstetric care at a rate lower than that offered by Medicare, 27 states offer greater support, and 16 states offer reimbursement well above the Medicare rate.

A federal target, too

The states aren’t the only entities with an eye on Medicaid cuts. The US Congress, too, is considering proposals to dramatically change the program. The options include issuing block grants for Medicaid; reducing the federal match; and including Medicaid in global or health spending caps. ACOG has an extensive campaign under way to ensure that any changes to Medicaid do not come at the expense of women’s health.

The Congressional Joint Special Committee on Deficit Reduction—more commonly known as the Supercommittee— represents the latest effort at deficit reduction. When its work imploded in December 2011, federal programs came online for a 2% across-the-board cut (“sequester”) that will take effect on January 1, 2013. The Medicaid program is exempt from this cut, no doubt in recognition of the already-precarious nature of this program, which has become a safety net for millions of American families struggling through the recession.

Because so many American women rely on Medicaid for obstetric and gynecologic care, it is critical that we protect funding levels and maintain eligibility for this program.

ACOG plays a prominent role in advocating for preservation of women’s access to care and adequate physician reimbursement levels. you can help by contacting your state legislators and representatives in the uS Congress to emphasize the importance of these efforts.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2008 Socioeconomic Survey of ACOG Fellows. Washington DC: ACOG; 2008.

2. Holahan J, Headen I. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State-by-State Results for Adults at or Below 133% FPL. Washington DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010.

3. National Association of State Budget Officers. State Expenditure Report 2010. Washington DC: NASBO; December 2011.

4. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. 2010 Maternal and Child Health Update. Issue Brief. Washington DC: National Governors Association; 2011. http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF. Accessed January 12, 2011.

5. Behrman RE, Butler AS. eds Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Women’s Health Survey 2004. Washington DC: KFF; 2005.

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere (October 2011)

Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lucia DiVenere (July 2010)

Is the patient-centered medical home a win-all or lose-all proposition for ObGyns?

Janelle Yates (October 2010)

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Tough economic times have pushed 2.8 million more people onto Medicaid rolls, now crowded with more than 60 million low-income individuals and families—nearly 20% of the US population.

Because Medicaid is a means-tested entitlement program, states and the federal government must fund as much health care as beneficiaries use, an expense that increases substantially each year.

Through the Medicaid program, more than 30 million adult women have access to an annual gynecologic exam, family planning services, and prenatal care. Without such coverage, many of them would go without care, potentially driving our nation’s health-care costs even higher. Two thirds of ObGyns treat Medicaid patients, and Medicaid accounts for 18%, on average, of an ObGyn practice’s revenue.1

In this article, I describe how the burgeoning ranks of Medicaid beneficiaries are straining state budgets and prompting legislators to cut provider payments to make up the shortfall. The federal government also plays a role in shrinking reimbursements for physicians and other providers.

Medicaid costs are outpacing economic growth

In fiscal 2011, Medicaid enrollment grew an average of 5.5%, and states are anticipating a growth rate of 4.1% in 2012.2 Total Medicaid spending is also increasing rapidly. In fiscal 2010, it was $361.8 billion (excluding administrative costs)—a 6% increase over fiscal 2009. By the end of fiscal 2011, it was expected to hit $398.6 billion—a 10.1% increase over 2010.3

Medicaid costs are also absorbing a greater share of state budgets. In fiscal 2009, they accounted for 21.9% of total state expenditures, 22.3% in fiscal 2010, and 23.6% in fiscal 2011.3 Many states have had to reduce spending in other important areas as a result (TABLE 1).

Medicaid costs are shared by federal and state governments. The federal government pays, on average, 57% of state program costs. In fiscal 2010, the federal government covered 64.6% of all Medicaid costs.

State general funds at the end of 2011 were well below their pre-recession levels, due to lower revenues and increased expenditures, including continued obligations for state workers’ pensions and retiree health care. At the same time, 49 state governments are required to balance their budgets. As a result, states are likely to face austere budgets for at least the next several years, and will continue to make difficult spending decisions.

As state and federal budgets face pressure to reduce overall spending, Medicaid lies in nearly all budget crosshairs.

TABLE 1

Medicaid absorbs an ever-greater percentage of state expenditures

| State | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal 2009 | Fiscal 2010 | Fiscal 2011 | |

| New England | |||

| Connecticut | 27.9 | 25.4 | 27.2 |

| Maine | 29.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Massachusetts | 17.8 | 18.8 | 20.2 |

| New Hampshire | 26.5 | 24.9 | 25.2 |

| Rhode Island | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| Vermont | 25.5 | 25.9 | 26.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | |||

| Delaware | 12.3 | 14.4 | 16.2 |

| Maryland | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.6 |

| New Jersey | 19.8 | 21.3 | 21.9 |

| New york | 26.7 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 30.2 | 29.6 | 31.1 |

| Great Lakes | |||

| Illinois | 24.8 | 23.6 | 28.9 |

| Indiana | 21.8 | 23.1 | 24.4 |

| Michigan | 23.0 | 24.2 | 24.0 |

| Ohio | 20.6 | 21.3 | 23.2 |

| Wisconsin | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.0 |

| Plains | |||

| Iowa | 17.9 | 18.6 | 19.3 |

| Kansas | 17.4 | 18.8 | 18.6 |

| Minnesota | 24.0 | 25.1 | 25.1 |

| Missouri | 35.6 | 34.4 | 36.3 |

| Nebraska | 17.6 | 17.2 | 16.5 |

| North Dakota | 14.1 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| South Dakota | 21.6 | 21.7 | 23.2 |

| Southeast | |||

| Alabama | 25.6 | 25.8 | 25.3 |

| Arkansas | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 |

| Florida | 26.7 | 30.0 | 28.0 |

| Georgia | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.5 |

| Kentucky | 22.5 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| Louisiana | 22.0 | 23.7 | 23.5 |

| Mississippi | 24.8 | 22.9 | 22.6 |

| North Carolina | 25.0 | 24.2 | 22.1 |

| South Carolina | 22.0 | 22.6 | 19.9 |

| Tennessee | 25.4 | 28.8 | 28.1 |

| Virginia | 16.4 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| West Virginia | 11.9 | 12.6 | 13.0 |

| Southwest | |||

| Arizona | 29.3 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| New Mexico | 20.7 | 22.1 | 20.2 |

| Oklahoma | 17.7 | 17.1 | 18.5 |

| Texas | 22.8 | 24.6 | 26.3 |

| Rocky Mountain | |||

| Colorado | 14.1 | 15.3 | 19.4 |

| Idaho | 22.8 | 23.0 | 25.6 |

| Montana | 15.2 | 15.4 | 15.7 |

| Utah | 14.9 | 11.9 | 14.3 |

| Wyoming | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Far West | |||

| Alaska | 8.1 | 12.0 | 9.0 |

| California | 20.6 | 18.9 | 24.2 |

| Hawaii | 11.3 | 13.3 | 15.9 |

| Nevada | 16.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 |

| Oregon | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.6 |

| Washington | 21.4 | 23.0 | 24.4 |

| Average | 21.9 | 22.3 | 23.6 |

The fiscal health of Medicaid matters—here’s why

Twelve percent of women 18 to 64 years old rely on Medicaid for health-care coverage, and three quarters of all adult Medicaid beneficiaries are women. Sixty-nine percent of women in the 18- to 64-year-old age group are in their reproductive years. Medicaid pays for 42% of all births in the United States—as many as 64% of all births in Arkansas and Oklahoma.4

Medicaid covers essential well-woman care, including maternity care, breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment, care for disabled women, and family planning.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for contraception and sterilization services, covering 71% of these costs. States clearly find it in their best interest and the best interest of public health to encourage use of family planning, which can improve women’s health and reduce the number of unintended pregnancies and abortions. In 2010, 27 states extended family planning coverage to women whose incomes, while still low, were higher than the standard Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Many states cover nutrition and substance abuse counseling, health education, psychosocial counseling, breastfeeding, and case management. TABLE 2 on page 16a lists mandatory and optional Medicaid services.

TABLE 2

Benefits of the Medicaid program

| Mandatory | Optional |

|---|---|

| Physician services Laboratory and radiographic services Hospitalization Outpatient services Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services for people younger than 21 years Family planning Rural and federally qualified health center services Nurse midwife services Nursing facility services for people older than 21 years Home health care for people entitled to nursing facility care Smoking cessation for pregnant women* Free-standing birth center services* | Prescription drugs Clinic services Dental services, dentures Physical therapy and rehabilitation Prosthetic devices, eyeglasses Primary-care case management Intermediate-care facilities for the mentally retarded Inpatient psychiatric care for people younger than 21 years Home health care and other services provided under home- and community-based waivers Personal care services Hospice care Health home services for people with chronic conditions* Home- and community-based attendant services and supports* |

| * Benefits added under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | |

Coming: Another 4.5 million women on Medicaid rolls

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Medicaid will expand to cover another 4.5 million women in 2014. Beginning January 1, 2014, state Medicaid programs are required to cover nonpregnant, non-elderly individuals who have incomes as high as 133% of the federal poverty level ($10,890 for an individual in 2011). The federal government will cover the full expense of insuring these newly eligible individuals for calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016. Federal financing will phase down to 90% by 2020, and will likely decrease further after that.

States that participate in Medicaid must cover pregnant women who have an income at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. States are required to disregard 5% of an individual’s income when determining Medicaid eligibility, a rule that effectively brings the maximum eligibility level to 138% of the federal poverty level, opening the Medicaid doors to additional low-income individuals.

Today, coverage lasts throughout pregnancy and 2 months beyond. States may choose to extend eligibility to pregnant women who have incomes that exceed 133% of the poverty level; at present, 45 states do so, with the District of Columbia topping the list by covering pregnant women who have incomes at or below 300% of the poverty level.

Many measures show that Medicaid has improved access to health care for low- income women, saving lives and dollars. Your experience—wherever you practice— undoubtedly echoes that observation.

Prenatal care. You also know that prenatal care helps ensure healthy babies. Obstetric services often go beyond traditional medical needs to include a full spectrum of care that helps ensure a healthy pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period.

Of course, inadequate use of prenatal care is associated with increased risks of low birth weight, preterm birth, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and maternal mortality. Preterm births alone increase US health-care costs by $26 billion each year.5 Pregnancy-related maternal mortality is three to four times higher, and infant mortality is more than six times higher, among women who receive no prenatal care, compared with those who receive prenatal care.

Gynecologic services covered through Medicaid also help preserve health and reduce health-care costs. Eighty-four percent of women on Medicaid have had a Pap test in the past 2 years, compared with 80% of women who have private insurance and 59% of women who lack insurance.6 Routine gynecologic care is vital to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases. Women without a regular doctor don’t get regular Pap tests and mammography; nor do they get screened for other serious health risks, including high cholesterol and diabetes.

Despite the proven benefits of access to regular care, 23% of women on Medicaid report problems finding a new doctor who will accept their insurance, compared with 7% of Medicare beneficiaries and 13% of women who have private insurance.

Why the difficulty in finding a doctor? A leading reason is the inadequacy of Medicaid payment rates.

Cutting payments to physicians

Medicaid provider payments are often the first item cut in a state budget crisis. States are required to cover many health services and are restricted from charging patients significant co-pays, so they often trim budgets at the expense of physicians. Thirty-nine states reduced physician and provider payments in 2011, and 46 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012. In addition, in fiscal 2011, 47 states put in place at least one new policy to control Medicaid costs; most states implemented several of these policies. All 50 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012.

Under federal rules, states must ensure that payment rates are consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. They also must ensure that payment is sufficient to enlist enough providers to render care and services to the same extent that care and services are available to the general population in the same geographic area. States must request and receive permission from the federal government before reducing provider payment rates. However, even with this safeguard in place, physician payments—and patient access to care—are in jeopardy.

For example, in 2008, the California legislature issued several rounds of cuts, including a 10% cut in physician and provider payments, to make up for budget shortfalls. Physicians, hospitals, pharmacists, and other health professionals sued in response, and the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the payment cut.

In 2011, California Governor Jerry Brown again put the 10% cut in place, this time with approval from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In response, California physicians, led by the state medical association, sued California again. They argued that payment cuts reduce access to care among Medicaid beneficiaries by prompting physicians to stop accepting these patients. The California Department of Health Care Services countered that the cuts are necessary to offset a critical budget shortfall and will not affect access to care. The situation in California highlights the conflicts between physicians and many states over Medicaid payment rates.

The US Supreme Court agreed to review the case on only one question—whether individuals and private parties, including doctors and Medicaid recipients, can sue the state for failing to pay rates that meet the federal adequacy requirement. On October 3, 2011, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this group of cases, known as Douglas v. Independent Living Center of Southern California. ACOG joined the case in support of physicians.

Medicaid versus Medicare

It’s easy to see how important Medicaid is to women’s health, and how important physician payment rates are to women’s access to care. You might expect, then, that states would recognize the value of adequate physician payment—but they don’t, always.

At present, Medicaid pays for obstetric care at 93% of the Medicare rate. Still, obstetric care fares slightly better than many physician services. In many states, it costs physicians much more than Medicaid pays to provide non-obstetric care to Mediaid patients. Although 23 states pay for obstetric care at a rate lower than that offered by Medicare, 27 states offer greater support, and 16 states offer reimbursement well above the Medicare rate.

A federal target, too

The states aren’t the only entities with an eye on Medicaid cuts. The US Congress, too, is considering proposals to dramatically change the program. The options include issuing block grants for Medicaid; reducing the federal match; and including Medicaid in global or health spending caps. ACOG has an extensive campaign under way to ensure that any changes to Medicaid do not come at the expense of women’s health.

The Congressional Joint Special Committee on Deficit Reduction—more commonly known as the Supercommittee— represents the latest effort at deficit reduction. When its work imploded in December 2011, federal programs came online for a 2% across-the-board cut (“sequester”) that will take effect on January 1, 2013. The Medicaid program is exempt from this cut, no doubt in recognition of the already-precarious nature of this program, which has become a safety net for millions of American families struggling through the recession.

Because so many American women rely on Medicaid for obstetric and gynecologic care, it is critical that we protect funding levels and maintain eligibility for this program.

ACOG plays a prominent role in advocating for preservation of women’s access to care and adequate physician reimbursement levels. you can help by contacting your state legislators and representatives in the uS Congress to emphasize the importance of these efforts.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Is private ObGyn practice on its way out?

Lucia DiVenere (October 2011)

Medicare and Medicaid are on the brink of insolvency, and you’re not just a bystander

Robert L. Barbieri, MD (Editorial, October 2011)

14 questions (and answers) about health reform and you

Janelle Yates, Senior Editor, with Lucia DiVenere (July 2010)

Is the patient-centered medical home a win-all or lose-all proposition for ObGyns?

Janelle Yates (October 2010)

Ms. DiVenere reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

Tough economic times have pushed 2.8 million more people onto Medicaid rolls, now crowded with more than 60 million low-income individuals and families—nearly 20% of the US population.

Because Medicaid is a means-tested entitlement program, states and the federal government must fund as much health care as beneficiaries use, an expense that increases substantially each year.

Through the Medicaid program, more than 30 million adult women have access to an annual gynecologic exam, family planning services, and prenatal care. Without such coverage, many of them would go without care, potentially driving our nation’s health-care costs even higher. Two thirds of ObGyns treat Medicaid patients, and Medicaid accounts for 18%, on average, of an ObGyn practice’s revenue.1

In this article, I describe how the burgeoning ranks of Medicaid beneficiaries are straining state budgets and prompting legislators to cut provider payments to make up the shortfall. The federal government also plays a role in shrinking reimbursements for physicians and other providers.

Medicaid costs are outpacing economic growth

In fiscal 2011, Medicaid enrollment grew an average of 5.5%, and states are anticipating a growth rate of 4.1% in 2012.2 Total Medicaid spending is also increasing rapidly. In fiscal 2010, it was $361.8 billion (excluding administrative costs)—a 6% increase over fiscal 2009. By the end of fiscal 2011, it was expected to hit $398.6 billion—a 10.1% increase over 2010.3

Medicaid costs are also absorbing a greater share of state budgets. In fiscal 2009, they accounted for 21.9% of total state expenditures, 22.3% in fiscal 2010, and 23.6% in fiscal 2011.3 Many states have had to reduce spending in other important areas as a result (TABLE 1).

Medicaid costs are shared by federal and state governments. The federal government pays, on average, 57% of state program costs. In fiscal 2010, the federal government covered 64.6% of all Medicaid costs.

State general funds at the end of 2011 were well below their pre-recession levels, due to lower revenues and increased expenditures, including continued obligations for state workers’ pensions and retiree health care. At the same time, 49 state governments are required to balance their budgets. As a result, states are likely to face austere budgets for at least the next several years, and will continue to make difficult spending decisions.

As state and federal budgets face pressure to reduce overall spending, Medicaid lies in nearly all budget crosshairs.

TABLE 1

Medicaid absorbs an ever-greater percentage of state expenditures

| State | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Fiscal 2009 | Fiscal 2010 | Fiscal 2011 | |

| New England | |||

| Connecticut | 27.9 | 25.4 | 27.2 |

| Maine | 29.9 | 28.6 | 28.6 |

| Massachusetts | 17.8 | 18.8 | 20.2 |

| New Hampshire | 26.5 | 24.9 | 25.2 |

| Rhode Island | 24.9 | 25.0 | 24.7 |

| Vermont | 25.5 | 25.9 | 26.6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | |||

| Delaware | 12.3 | 14.4 | 16.2 |

| Maryland | 19.3 | 20.4 | 21.6 |

| New Jersey | 19.8 | 21.3 | 21.9 |

| New york | 26.7 | 28.7 | 29.1 |

| Pennsylvania | 30.2 | 29.6 | 31.1 |

| Great Lakes | |||

| Illinois | 24.8 | 23.6 | 28.9 |

| Indiana | 21.8 | 23.1 | 24.4 |

| Michigan | 23.0 | 24.2 | 24.0 |

| Ohio | 20.6 | 21.3 | 23.2 |

| Wisconsin | 15.7 | 17.1 | 17.0 |

| Plains | |||

| Iowa | 17.9 | 18.6 | 19.3 |

| Kansas | 17.4 | 18.8 | 18.6 |

| Minnesota | 24.0 | 25.1 | 25.1 |

| Missouri | 35.6 | 34.4 | 36.3 |

| Nebraska | 17.6 | 17.2 | 16.5 |

| North Dakota | 14.1 | 13.7 | 14.6 |

| South Dakota | 21.6 | 21.7 | 23.2 |

| Southeast | |||

| Alabama | 25.6 | 25.8 | 25.3 |

| Arkansas | 19.7 | 20.0 | 20.5 |

| Florida | 26.7 | 30.0 | 28.0 |

| Georgia | 19.0 | 19.5 | 20.5 |

| Kentucky | 22.5 | 21.9 | 22.8 |

| Louisiana | 22.0 | 23.7 | 23.5 |

| Mississippi | 24.8 | 22.9 | 22.6 |

| North Carolina | 25.0 | 24.2 | 22.1 |

| South Carolina | 22.0 | 22.6 | 19.9 |

| Tennessee | 25.4 | 28.8 | 28.1 |

| Virginia | 16.4 | 16.1 | 16.9 |

| West Virginia | 11.9 | 12.6 | 13.0 |

| Southwest | |||

| Arizona | 29.3 | 27.7 | 28.0 |

| New Mexico | 20.7 | 22.1 | 20.2 |

| Oklahoma | 17.7 | 17.1 | 18.5 |

| Texas | 22.8 | 24.6 | 26.3 |

| Rocky Mountain | |||

| Colorado | 14.1 | 15.3 | 19.4 |

| Idaho | 22.8 | 23.0 | 25.6 |

| Montana | 15.2 | 15.4 | 15.7 |

| Utah | 14.9 | 11.9 | 14.3 |

| Wyoming | 8.1 | 7.3 | 7.0 |

| Far West | |||

| Alaska | 8.1 | 12.0 | 9.0 |

| California | 20.6 | 18.9 | 24.2 |

| Hawaii | 11.3 | 13.3 | 15.9 |

| Nevada | 16.0 | 18.3 | 18.7 |

| Oregon | 14.3 | 13.1 | 14.6 |

| Washington | 21.4 | 23.0 | 24.4 |

| Average | 21.9 | 22.3 | 23.6 |

The fiscal health of Medicaid matters—here’s why

Twelve percent of women 18 to 64 years old rely on Medicaid for health-care coverage, and three quarters of all adult Medicaid beneficiaries are women. Sixty-nine percent of women in the 18- to 64-year-old age group are in their reproductive years. Medicaid pays for 42% of all births in the United States—as many as 64% of all births in Arkansas and Oklahoma.4

Medicaid covers essential well-woman care, including maternity care, breast and cervical cancer screening and treatment, care for disabled women, and family planning.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding for contraception and sterilization services, covering 71% of these costs. States clearly find it in their best interest and the best interest of public health to encourage use of family planning, which can improve women’s health and reduce the number of unintended pregnancies and abortions. In 2010, 27 states extended family planning coverage to women whose incomes, while still low, were higher than the standard Medicaid eligibility requirements.

Many states cover nutrition and substance abuse counseling, health education, psychosocial counseling, breastfeeding, and case management. TABLE 2 on page 16a lists mandatory and optional Medicaid services.

TABLE 2

Benefits of the Medicaid program

| Mandatory | Optional |

|---|---|

| Physician services Laboratory and radiographic services Hospitalization Outpatient services Early and periodic screening, diagnostic, and treatment services for people younger than 21 years Family planning Rural and federally qualified health center services Nurse midwife services Nursing facility services for people older than 21 years Home health care for people entitled to nursing facility care Smoking cessation for pregnant women* Free-standing birth center services* | Prescription drugs Clinic services Dental services, dentures Physical therapy and rehabilitation Prosthetic devices, eyeglasses Primary-care case management Intermediate-care facilities for the mentally retarded Inpatient psychiatric care for people younger than 21 years Home health care and other services provided under home- and community-based waivers Personal care services Hospice care Health home services for people with chronic conditions* Home- and community-based attendant services and supports* |

| * Benefits added under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act | |

Coming: Another 4.5 million women on Medicaid rolls

Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, Medicaid will expand to cover another 4.5 million women in 2014. Beginning January 1, 2014, state Medicaid programs are required to cover nonpregnant, non-elderly individuals who have incomes as high as 133% of the federal poverty level ($10,890 for an individual in 2011). The federal government will cover the full expense of insuring these newly eligible individuals for calendar years 2014, 2015, and 2016. Federal financing will phase down to 90% by 2020, and will likely decrease further after that.

States that participate in Medicaid must cover pregnant women who have an income at or below 133% of the federal poverty level. States are required to disregard 5% of an individual’s income when determining Medicaid eligibility, a rule that effectively brings the maximum eligibility level to 138% of the federal poverty level, opening the Medicaid doors to additional low-income individuals.

Today, coverage lasts throughout pregnancy and 2 months beyond. States may choose to extend eligibility to pregnant women who have incomes that exceed 133% of the poverty level; at present, 45 states do so, with the District of Columbia topping the list by covering pregnant women who have incomes at or below 300% of the poverty level.

Many measures show that Medicaid has improved access to health care for low- income women, saving lives and dollars. Your experience—wherever you practice— undoubtedly echoes that observation.

Prenatal care. You also know that prenatal care helps ensure healthy babies. Obstetric services often go beyond traditional medical needs to include a full spectrum of care that helps ensure a healthy pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum period.

Of course, inadequate use of prenatal care is associated with increased risks of low birth weight, preterm birth, neonatal mortality, infant mortality, and maternal mortality. Preterm births alone increase US health-care costs by $26 billion each year.5 Pregnancy-related maternal mortality is three to four times higher, and infant mortality is more than six times higher, among women who receive no prenatal care, compared with those who receive prenatal care.

Gynecologic services covered through Medicaid also help preserve health and reduce health-care costs. Eighty-four percent of women on Medicaid have had a Pap test in the past 2 years, compared with 80% of women who have private insurance and 59% of women who lack insurance.6 Routine gynecologic care is vital to prevent cervical cancer and other diseases. Women without a regular doctor don’t get regular Pap tests and mammography; nor do they get screened for other serious health risks, including high cholesterol and diabetes.

Despite the proven benefits of access to regular care, 23% of women on Medicaid report problems finding a new doctor who will accept their insurance, compared with 7% of Medicare beneficiaries and 13% of women who have private insurance.

Why the difficulty in finding a doctor? A leading reason is the inadequacy of Medicaid payment rates.

Cutting payments to physicians

Medicaid provider payments are often the first item cut in a state budget crisis. States are required to cover many health services and are restricted from charging patients significant co-pays, so they often trim budgets at the expense of physicians. Thirty-nine states reduced physician and provider payments in 2011, and 46 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012. In addition, in fiscal 2011, 47 states put in place at least one new policy to control Medicaid costs; most states implemented several of these policies. All 50 states plan to do so in fiscal 2012.

Under federal rules, states must ensure that payment rates are consistent with efficiency, economy, and quality of care. They also must ensure that payment is sufficient to enlist enough providers to render care and services to the same extent that care and services are available to the general population in the same geographic area. States must request and receive permission from the federal government before reducing provider payment rates. However, even with this safeguard in place, physician payments—and patient access to care—are in jeopardy.

For example, in 2008, the California legislature issued several rounds of cuts, including a 10% cut in physician and provider payments, to make up for budget shortfalls. Physicians, hospitals, pharmacists, and other health professionals sued in response, and the 9th US Circuit Court of Appeals blocked the payment cut.

In 2011, California Governor Jerry Brown again put the 10% cut in place, this time with approval from the federal Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).

In response, California physicians, led by the state medical association, sued California again. They argued that payment cuts reduce access to care among Medicaid beneficiaries by prompting physicians to stop accepting these patients. The California Department of Health Care Services countered that the cuts are necessary to offset a critical budget shortfall and will not affect access to care. The situation in California highlights the conflicts between physicians and many states over Medicaid payment rates.

The US Supreme Court agreed to review the case on only one question—whether individuals and private parties, including doctors and Medicaid recipients, can sue the state for failing to pay rates that meet the federal adequacy requirement. On October 3, 2011, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in this group of cases, known as Douglas v. Independent Living Center of Southern California. ACOG joined the case in support of physicians.

Medicaid versus Medicare

It’s easy to see how important Medicaid is to women’s health, and how important physician payment rates are to women’s access to care. You might expect, then, that states would recognize the value of adequate physician payment—but they don’t, always.

At present, Medicaid pays for obstetric care at 93% of the Medicare rate. Still, obstetric care fares slightly better than many physician services. In many states, it costs physicians much more than Medicaid pays to provide non-obstetric care to Mediaid patients. Although 23 states pay for obstetric care at a rate lower than that offered by Medicare, 27 states offer greater support, and 16 states offer reimbursement well above the Medicare rate.

A federal target, too

The states aren’t the only entities with an eye on Medicaid cuts. The US Congress, too, is considering proposals to dramatically change the program. The options include issuing block grants for Medicaid; reducing the federal match; and including Medicaid in global or health spending caps. ACOG has an extensive campaign under way to ensure that any changes to Medicaid do not come at the expense of women’s health.

The Congressional Joint Special Committee on Deficit Reduction—more commonly known as the Supercommittee— represents the latest effort at deficit reduction. When its work imploded in December 2011, federal programs came online for a 2% across-the-board cut (“sequester”) that will take effect on January 1, 2013. The Medicaid program is exempt from this cut, no doubt in recognition of the already-precarious nature of this program, which has become a safety net for millions of American families struggling through the recession.

Because so many American women rely on Medicaid for obstetric and gynecologic care, it is critical that we protect funding levels and maintain eligibility for this program.

ACOG plays a prominent role in advocating for preservation of women’s access to care and adequate physician reimbursement levels. you can help by contacting your state legislators and representatives in the uS Congress to emphasize the importance of these efforts.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2008 Socioeconomic Survey of ACOG Fellows. Washington DC: ACOG; 2008.

2. Holahan J, Headen I. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State-by-State Results for Adults at or Below 133% FPL. Washington DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010.

3. National Association of State Budget Officers. State Expenditure Report 2010. Washington DC: NASBO; December 2011.

4. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. 2010 Maternal and Child Health Update. Issue Brief. Washington DC: National Governors Association; 2011. http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF. Accessed January 12, 2011.

5. Behrman RE, Butler AS. eds Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Women’s Health Survey 2004. Washington DC: KFF; 2005.

1. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2008 Socioeconomic Survey of ACOG Fellows. Washington DC: ACOG; 2008.

2. Holahan J, Headen I. Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. Medicaid Coverage and Spending in Health Reform: National and State-by-State Results for Adults at or Below 133% FPL. Washington DC: Kaiser Family Foundation; 2010.

3. National Association of State Budget Officers. State Expenditure Report 2010. Washington DC: NASBO; December 2011.

4. National Governors Association Center for Best Practices. 2010 Maternal and Child Health Update. Issue Brief. Washington DC: National Governors Association; 2011. http://www.nga.org/files/live/sites/NGA/files/pdf/MCHUPDATE2010.PDF. Accessed January 12, 2011.

5. Behrman RE, Butler AS. eds Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. Preterm Birth: Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2007.

6. Kaiser Family Foundation. Kaiser Women’s Health Survey 2004. Washington DC: KFF; 2005.