User login

Opportunities to partner with clinical pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

In this article, we highlight key steps that were needed to integrate clinical pharmacy specialists at an academic ambulatory psychiatric and addiction treatment center that serves pediatric and adult populations. Academic stakeholders identified addition of pharmacy services as a strategic goal in an effort to maximize services offered by the center and increase patient access to care while aligning with the standards set out by the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model.

We outline the role of clinical pharmacists in the care of adult patients in ambulatory psychiatry, illustrate opportunities to enhance patient care, point out possible challenges with implementation, and propose future initiatives to optimize the practitioner-pharmacist partnership.

Background: Role of ambulatory pharmacists in psychiatry

Clinical pharmacists’ role in the psychiatric ambulatory care setting generally is associated with positive outcomes. One study looking at a collaborative care model that utilized clinical pharmacist follow-up in managing major depressive disorder found that patients who received pharmacist intervention in the collaborative care model had, on average, a significantly higher adherence rate and patient satisfaction score than the “usual care” group.1 Within this study, patients in both groups experienced global clinical improvement with no significant difference; however, pharmacist interventions had a positive impact on several aspects of the care model, suggesting that pharmacists can be used effectively in ambulatory psychiatry.

Furthermore, a systematic study evaluating pharmacists’ impact on clinical and functional mental health outcomes identified 8 relevant studies conducted in the outpatient setting.2 Although interventions varied widely, most studies focused on pharmacists’ providing a combination of drug monitoring, treatment recommendations, and patient education. Outcomes were largely positive, including an overall reduction in number and dosage of psychiatric drugs, inferred cost savings, and significant improvements in the safe and efficacious use of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

These preliminary positive results require replication in larger, randomized cohorts. Additionally, the role of the pharmacist as medication manager in the collaborative care model requires further study. Results so far, however, indicate that pharmacists can have a positive impact on the care of ambulatory psychiatry patients. Nevertheless, there is still considerable need for ongoing exploration in this field.

Pre-implementation

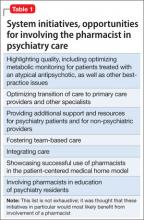

The need for pharmacy services. Various initiatives and existing practices within our health care system have underscored the need for a psychiatric pharmacist in the outpatient setting (Table 1).

A board-certified psychiatric pharmacist (BCPP) possesses specialized knowledge about treating patients affected by psychiatric illnesses. BCPPs work with prescribers and members of other disciplines, such as nurses and social workers, to optimize drug treatment by making pharmacotherapeutic recommendations and providing appropriate monitoring to enhance patient satisfaction and quality of life.3,4

Existing relationship with pharmacy. Along with evidence to support the positive impact clinical pharmacists can have in caring for patients with mental illness in the outpatient setting, a strong existing relationship between the Department of Psychiatry and our adult inpatient psychiatric pharmacist helped make it possible to develop an ambulatory psychiatric pharmacist position.

Each day, the inpatient psychiatric pharmacist works closely with the attending psychiatrists and psychiatry residents to provide treatment recommendations and counseling services for patients on the unit. The psychiatry residents highly valued their experiences with the pharmacist in the inpatient setting and expressed disappointment that this collaborative relationship was no longer available after they transitioned into the ambulatory setting.

Further, by being involved in initiatives that were relevant to both inpatient and outpatient psychiatry, such as metabolic monitoring for patients taking atypical antipsychotics, the clinical pharmacist in inpatient psychiatry had the opportunity to interact with key stakeholders in both settings. As a result of these pre-existing collaborative relationships, many clinicians were eager to have pharmacists available as a resource for patient care in the outpatient setting.

Pharmacist perspective: Outreach to psychiatry leadershipRecognizing the incentives and opportunities inherent in our emerging health care system, pharmacists became integral members of the patient care team in the PCMH model. Thanks to this effort, we now have PCMH pharmacists at every primary care health center in our health system (14 sites), providing disease management programs and polypharmacy services.

PCMH pharmacists’ role in the primary care setting fueled interest from specialty services and created opportunities to extend our existing partnership in inpatient psychiatry. One such opportunity to demonstrate the expertise of a psychiatric pharmacist was fueled by the FDA’s citalopram dosing alert5 at a system-wide level. This warning emerged as a chance to showcase the skill set of psychiatric pharmacists and the pharmacists’ successes in our PCMH model. The partnership was extended to include the buy-in of ambulatory pharmacy leadership and key stakeholders in ambulatory psychiatry.

Initial meetings included ambulatory care site leadership in psychiatry to increase awareness and understanding of pharmacists’ potential role in direct patient care. Achieving site leadership support was critical to successful implementation of pharmacist services in psychiatry. We also obtained approval from the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry to elicit support from faculty group practice.

Psychiatry leadership perspective

As fiscal pressures intensify at academic health centers, it becomes increasingly important for resources to be used as efficiently and effectively as possible. As a greater percentage of mental health patients with more “straightforward,” less complex conditions are being managed by their primary care providers or nonprescribing psychotherapists, or both, the acuity and complexity of cases in patients who present to psychiatric clinics have intensified. This intensification of patient needs and clinical acuity is in heightened conflict with the ongoing demand for clinician productivity and efficiency.

Additionally, the need to provide care to a seemingly ever-growing number of moderately or severely ill patients during shorter, less frequent visits presents a daunting task for clinicians and clinical leaders. Collaborative care models appear to offer the best hope for managing the seemingly overwhelming demand for services.

In this model, the patient, who is the critical member of the team, is expected to become an “expert” on his or her illness and to partner with members of the multidisciplinary team; with this support, patients are encouraged to develop a broad range of self-management skills and strategies to manage their illness. We believe that clinical pharmacists can and should play a critical role, not only in delivering direct clinical services to patients but also in developing and devising the care models that will most effectively apply each team member’s unique set of knowledge, skills, and experience. Given the large percentage of our patients who have multiple medical comorbidities and who require complex medical and psychiatric medication regimens, the role of the pharmacist in reviewing, educating, and advising patients and other team members on these crucial pharmacy concerns will be paramount.

In light of these complex medication issues, pharmacists are uniquely positioned to serve as a liaison among the patient, the primary care provider, and other members of their treatment team. We anticipate that our ambulatory psychiatry pharmacists will greatly enhance the comfort and confidence of patients and their primary care providers during periods of care transition.

Potential roles for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

One potential role for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry is to perform polypharmacy assessments of patients receiving complex medication regimens, prompted by physician referral. The poly pharmacy intake interview, performed to obtain an accurate medication list and to identify patients’ concerns about their medications, can be conducted in person or by telephone. Patients’ knowledge about medications and medication adherence are discussed, as are their perceptions of effectiveness and adverse effects.

After initial data gathering, pharmacists complete a review of the medications, identifying any problems associated with medication indication, efficacy, tolerance, or adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, drug-nutrient interactions, and nonadherence. Pharmacists work to reduce medication costs if that is a concern of the patient, because nonadherence can result. A medication care plan is then developed in consultation with the primary care provider; here, the medication list is reconciled, the electronic medical record is updated, and actions to address any medication-related problems are prioritized.

Other services that might be offered include:• group education classes, based on patient motivational interviewing strategies, to address therapeutic nonadherence and to improve understanding of their disease and treatment regimens• medication safety and monitoring• treatment intensification, as needed, following established protocols.

These are a few of the ways in which pharmacists can be relied on to expand and improve access to patient care services within ambulatory psychiatry. Key stakeholders anticipate development of newer ideas as the pharmacist’s role in ambulatory psychiatry is increasingly clarified.

Reimbursement model

In creating a role for pharmacy in ambulatory psychiatry, it was essential that the model be financially viable and appealing. Alongside its clinical model, our institution has developed a financial model to support the pharmacist’s role. The lump-sum payment to the health centers from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan afforded the ambulatory care clinics an opportunity to invest in PCMH pharmacists. This funding, and the reimbursement based on T-code billing (face-to-face visits and phone consultation) for depression and other conditions requiring chronic care, provides ongoing support. From our experience, understanding physician reimbursement models and identifying relevant changes in health care reform are necessary to integrate new providers, including pharmacists, into a team-based care model.

Implementation

Promoting pharmacy services. To foster anticipated collaboration with clinical pharmacists, the medical director of outpatient psychiatry disseminated an announcement to all providers regarding the investiture of clinical pharmacists to support patient care activities, education, and research. Clinicians were educated about the pharmacists’ potential roles and about guidelines and methods for referral. Use of our electronic health record system enabled us to establish a relatively simple referral process involving sharing electronic messages with our pharmacists.

Further, as part of the planned integration of clinical pharmacists in the ambulatory psychiatry setting, pharmacists met strategically with members of various disciplines, clinical programs, specialty clinic programs, and teams throughout the center. In addition to answering questions about the referral process, they emphasized the role of pharmacy and opportunities for collaboration.

Collaborating with others. Because the involvement of clinical pharmacists is unfamiliar to some practitioners in outpatient psychiatry, it is important to develop services without infringing on the roles other disciplines play. Indeed, a survey by Wheeler et al6 identified many concerns and potential boundaries among pharmacists, other providers, and patients. Concerns included confusion of practitioner roles and boundaries, a too-traditional perception of the pharmacist, and demonstration of competence.6

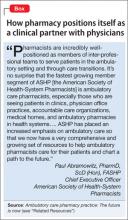

Early on, we developed a structured forum to discuss ongoing challenges and address issues related to the rapidly changing clinical landscape. During these discussions we conveyed that adding pharmacists to psychiatric services would be collaborative in nature and intended to augment existing services. This communication was pivotal to maintain the psychiatrist’s role as the ultimate prescriber and authority in the care of their patients; however, the pharmacist’s expertise, when sought, would help spur clinical and academic discussion that will benefit the patient. These discussions are paramount to achieving a productive, team-based approach, to overcome challenges, and to identify opportunities of value to our providers and patients (Box).

Work in progress

Implementing change in any clinical setting invariably creates challenges, and our endeavors to integrate clinical pharmacists into ambulatory psychiatry are no exception. We have identified several factors that we believe will optimize successful collaboration between pharmacy and ambulatory psychiatry (Table 2). Our primary challenge has been changing clinician behavior. Clinical practitioners can become too comfortable, wedded to their routines, and often are understandably resistant to change. Additionally, clinical systems often are inadvertently designed to obstruct change in ways that are not readily apparent. Efforts must be focused on behaviors and practices the clinical culture should encourage.

Regarding specific initiatives, clinical pharmacists have successfully identified patients on higher than recommended dosages of citalopram; they are working alongside prescribers to recommend ways to minimize the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities in these patients. Numerous prescribers have sought clinical pharmacists’ input to manage pharmacotherapy in their patients and to respond to patients’ questions on drug information.

The prospect of access to clinical pharmacist expertise in the outpatient setting was heralded with excitement, but the flow of referrals and consultations has been uneven. However simple the path for referral is, clinicians’ use of the system has been inconsistent—perhaps because of referrals’ passive, clinician-dependent nature. Educational outreach efforts often prompt a brief spike in referrals, only to be followed over time by a slow, steady drop-off. More active strategies will be needed, such as embedding the pharmacists as regular, active, visible members of the various clinical teams, and implementing a system in which patient record reviews are assigned to the pharmacists according to agreed-upon clusters of clinical criteria.

One of these tactics has, in the short term, showed success. Embedded in one of our newer clinics, which were designed to bridge primary and psychiatric care, clinical pharmacists are helping manage medically complicated patients. They assist with medication selection in light of drug interactions and medical comorbidities, conduct detailed medication histories, schedule follow-up visits to assess medication adherence and tolerability, and counsel patients experiencing insurance changes that make their medications less affordable. Integrating pharmacists in the new clinics has resulted in a steady flow of patient referrals and collaborative care work.

Clinical pharmacists are brainstorming with outpatient psychiatry leadership to build on these early successes. Ongoing communication and enhanced collaboration are essential, and can only improve the lives of our psychiatric patients.

For the future

Our partnership in ambulatory psychiatry was timed to occur during implementation of our health system’s new electronic health record initiative. Clinical pharmacists can play a key role in demonstrating use of the system to provide consistently accurate drug information to patients and to monitor patients receiving specific medications.

Development of ambulatory patient medication education groups, which has proved useful on the inpatient side, is another endeavor in the works. Integrating the clinical pharmacist with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and trainees on specific teams devoted to depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, perinatal mental health, and personality disorders also might prove to be a wide-ranging and promising strategy.

Enhancing the education and training experiences of residents, fellows, medical students, pharmacy students, and allied health professional learners present in our clinics is another exciting prospect. This cross-disciplinary training will yield a new generation of providers who will be more comfortable collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, all intent on providing high-quality, efficient care. We hope that, as these initiatives take root, we will recognize many opportunities to disseminate our collaborative efforts in scholarly venues, documenting and sharing the positive impact of our partnership.

Bottom Line

Because psychiatric outpatients present with challenging medical comorbidities and increasingly complex medication regimens, specialized clinical pharmacists can enrich the management team by offering essential monitoring and polypharmacy services, patient education and counseling, and cross-discipline training. At one academic treatment center, psychiatric and non-psychiatric practitioners are gradually buying in to these promising collaborative efforts.

Related Resources

• Board of Pharmacy Specialties. www.bpsweb.org/specialties/psychiatric.cfm.

• Abramowitz P. Ambulatory care pharmacy practice: The future is now. www.connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2014/05/14/ambulatory-care-pharmacy-practice-the-future-is-now.

Drug Brand Name

Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175-1185.

2. Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(12):1634-1644.

3. Board of Pharmacy Specialties. http://www.bpsweb. org. Accessed June 4, 2014.

4. Cohen LJ. The role of neuropsychiatric pharmacists. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 19):54-57.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391. htm. Accessed June 4, 2014.

6. Wheeler A, Crump K, Lee M, et al. Collaborative prescribing: a qualitative exploration of a role for pharmacists in mental health. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(3):179-192.

In this article, we highlight key steps that were needed to integrate clinical pharmacy specialists at an academic ambulatory psychiatric and addiction treatment center that serves pediatric and adult populations. Academic stakeholders identified addition of pharmacy services as a strategic goal in an effort to maximize services offered by the center and increase patient access to care while aligning with the standards set out by the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model.

We outline the role of clinical pharmacists in the care of adult patients in ambulatory psychiatry, illustrate opportunities to enhance patient care, point out possible challenges with implementation, and propose future initiatives to optimize the practitioner-pharmacist partnership.

Background: Role of ambulatory pharmacists in psychiatry

Clinical pharmacists’ role in the psychiatric ambulatory care setting generally is associated with positive outcomes. One study looking at a collaborative care model that utilized clinical pharmacist follow-up in managing major depressive disorder found that patients who received pharmacist intervention in the collaborative care model had, on average, a significantly higher adherence rate and patient satisfaction score than the “usual care” group.1 Within this study, patients in both groups experienced global clinical improvement with no significant difference; however, pharmacist interventions had a positive impact on several aspects of the care model, suggesting that pharmacists can be used effectively in ambulatory psychiatry.

Furthermore, a systematic study evaluating pharmacists’ impact on clinical and functional mental health outcomes identified 8 relevant studies conducted in the outpatient setting.2 Although interventions varied widely, most studies focused on pharmacists’ providing a combination of drug monitoring, treatment recommendations, and patient education. Outcomes were largely positive, including an overall reduction in number and dosage of psychiatric drugs, inferred cost savings, and significant improvements in the safe and efficacious use of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

These preliminary positive results require replication in larger, randomized cohorts. Additionally, the role of the pharmacist as medication manager in the collaborative care model requires further study. Results so far, however, indicate that pharmacists can have a positive impact on the care of ambulatory psychiatry patients. Nevertheless, there is still considerable need for ongoing exploration in this field.

Pre-implementation

The need for pharmacy services. Various initiatives and existing practices within our health care system have underscored the need for a psychiatric pharmacist in the outpatient setting (Table 1).

A board-certified psychiatric pharmacist (BCPP) possesses specialized knowledge about treating patients affected by psychiatric illnesses. BCPPs work with prescribers and members of other disciplines, such as nurses and social workers, to optimize drug treatment by making pharmacotherapeutic recommendations and providing appropriate monitoring to enhance patient satisfaction and quality of life.3,4

Existing relationship with pharmacy. Along with evidence to support the positive impact clinical pharmacists can have in caring for patients with mental illness in the outpatient setting, a strong existing relationship between the Department of Psychiatry and our adult inpatient psychiatric pharmacist helped make it possible to develop an ambulatory psychiatric pharmacist position.

Each day, the inpatient psychiatric pharmacist works closely with the attending psychiatrists and psychiatry residents to provide treatment recommendations and counseling services for patients on the unit. The psychiatry residents highly valued their experiences with the pharmacist in the inpatient setting and expressed disappointment that this collaborative relationship was no longer available after they transitioned into the ambulatory setting.

Further, by being involved in initiatives that were relevant to both inpatient and outpatient psychiatry, such as metabolic monitoring for patients taking atypical antipsychotics, the clinical pharmacist in inpatient psychiatry had the opportunity to interact with key stakeholders in both settings. As a result of these pre-existing collaborative relationships, many clinicians were eager to have pharmacists available as a resource for patient care in the outpatient setting.

Pharmacist perspective: Outreach to psychiatry leadershipRecognizing the incentives and opportunities inherent in our emerging health care system, pharmacists became integral members of the patient care team in the PCMH model. Thanks to this effort, we now have PCMH pharmacists at every primary care health center in our health system (14 sites), providing disease management programs and polypharmacy services.

PCMH pharmacists’ role in the primary care setting fueled interest from specialty services and created opportunities to extend our existing partnership in inpatient psychiatry. One such opportunity to demonstrate the expertise of a psychiatric pharmacist was fueled by the FDA’s citalopram dosing alert5 at a system-wide level. This warning emerged as a chance to showcase the skill set of psychiatric pharmacists and the pharmacists’ successes in our PCMH model. The partnership was extended to include the buy-in of ambulatory pharmacy leadership and key stakeholders in ambulatory psychiatry.

Initial meetings included ambulatory care site leadership in psychiatry to increase awareness and understanding of pharmacists’ potential role in direct patient care. Achieving site leadership support was critical to successful implementation of pharmacist services in psychiatry. We also obtained approval from the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry to elicit support from faculty group practice.

Psychiatry leadership perspective

As fiscal pressures intensify at academic health centers, it becomes increasingly important for resources to be used as efficiently and effectively as possible. As a greater percentage of mental health patients with more “straightforward,” less complex conditions are being managed by their primary care providers or nonprescribing psychotherapists, or both, the acuity and complexity of cases in patients who present to psychiatric clinics have intensified. This intensification of patient needs and clinical acuity is in heightened conflict with the ongoing demand for clinician productivity and efficiency.

Additionally, the need to provide care to a seemingly ever-growing number of moderately or severely ill patients during shorter, less frequent visits presents a daunting task for clinicians and clinical leaders. Collaborative care models appear to offer the best hope for managing the seemingly overwhelming demand for services.

In this model, the patient, who is the critical member of the team, is expected to become an “expert” on his or her illness and to partner with members of the multidisciplinary team; with this support, patients are encouraged to develop a broad range of self-management skills and strategies to manage their illness. We believe that clinical pharmacists can and should play a critical role, not only in delivering direct clinical services to patients but also in developing and devising the care models that will most effectively apply each team member’s unique set of knowledge, skills, and experience. Given the large percentage of our patients who have multiple medical comorbidities and who require complex medical and psychiatric medication regimens, the role of the pharmacist in reviewing, educating, and advising patients and other team members on these crucial pharmacy concerns will be paramount.

In light of these complex medication issues, pharmacists are uniquely positioned to serve as a liaison among the patient, the primary care provider, and other members of their treatment team. We anticipate that our ambulatory psychiatry pharmacists will greatly enhance the comfort and confidence of patients and their primary care providers during periods of care transition.

Potential roles for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

One potential role for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry is to perform polypharmacy assessments of patients receiving complex medication regimens, prompted by physician referral. The poly pharmacy intake interview, performed to obtain an accurate medication list and to identify patients’ concerns about their medications, can be conducted in person or by telephone. Patients’ knowledge about medications and medication adherence are discussed, as are their perceptions of effectiveness and adverse effects.

After initial data gathering, pharmacists complete a review of the medications, identifying any problems associated with medication indication, efficacy, tolerance, or adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, drug-nutrient interactions, and nonadherence. Pharmacists work to reduce medication costs if that is a concern of the patient, because nonadherence can result. A medication care plan is then developed in consultation with the primary care provider; here, the medication list is reconciled, the electronic medical record is updated, and actions to address any medication-related problems are prioritized.

Other services that might be offered include:• group education classes, based on patient motivational interviewing strategies, to address therapeutic nonadherence and to improve understanding of their disease and treatment regimens• medication safety and monitoring• treatment intensification, as needed, following established protocols.

These are a few of the ways in which pharmacists can be relied on to expand and improve access to patient care services within ambulatory psychiatry. Key stakeholders anticipate development of newer ideas as the pharmacist’s role in ambulatory psychiatry is increasingly clarified.

Reimbursement model

In creating a role for pharmacy in ambulatory psychiatry, it was essential that the model be financially viable and appealing. Alongside its clinical model, our institution has developed a financial model to support the pharmacist’s role. The lump-sum payment to the health centers from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan afforded the ambulatory care clinics an opportunity to invest in PCMH pharmacists. This funding, and the reimbursement based on T-code billing (face-to-face visits and phone consultation) for depression and other conditions requiring chronic care, provides ongoing support. From our experience, understanding physician reimbursement models and identifying relevant changes in health care reform are necessary to integrate new providers, including pharmacists, into a team-based care model.

Implementation

Promoting pharmacy services. To foster anticipated collaboration with clinical pharmacists, the medical director of outpatient psychiatry disseminated an announcement to all providers regarding the investiture of clinical pharmacists to support patient care activities, education, and research. Clinicians were educated about the pharmacists’ potential roles and about guidelines and methods for referral. Use of our electronic health record system enabled us to establish a relatively simple referral process involving sharing electronic messages with our pharmacists.

Further, as part of the planned integration of clinical pharmacists in the ambulatory psychiatry setting, pharmacists met strategically with members of various disciplines, clinical programs, specialty clinic programs, and teams throughout the center. In addition to answering questions about the referral process, they emphasized the role of pharmacy and opportunities for collaboration.

Collaborating with others. Because the involvement of clinical pharmacists is unfamiliar to some practitioners in outpatient psychiatry, it is important to develop services without infringing on the roles other disciplines play. Indeed, a survey by Wheeler et al6 identified many concerns and potential boundaries among pharmacists, other providers, and patients. Concerns included confusion of practitioner roles and boundaries, a too-traditional perception of the pharmacist, and demonstration of competence.6

Early on, we developed a structured forum to discuss ongoing challenges and address issues related to the rapidly changing clinical landscape. During these discussions we conveyed that adding pharmacists to psychiatric services would be collaborative in nature and intended to augment existing services. This communication was pivotal to maintain the psychiatrist’s role as the ultimate prescriber and authority in the care of their patients; however, the pharmacist’s expertise, when sought, would help spur clinical and academic discussion that will benefit the patient. These discussions are paramount to achieving a productive, team-based approach, to overcome challenges, and to identify opportunities of value to our providers and patients (Box).

Work in progress

Implementing change in any clinical setting invariably creates challenges, and our endeavors to integrate clinical pharmacists into ambulatory psychiatry are no exception. We have identified several factors that we believe will optimize successful collaboration between pharmacy and ambulatory psychiatry (Table 2). Our primary challenge has been changing clinician behavior. Clinical practitioners can become too comfortable, wedded to their routines, and often are understandably resistant to change. Additionally, clinical systems often are inadvertently designed to obstruct change in ways that are not readily apparent. Efforts must be focused on behaviors and practices the clinical culture should encourage.

Regarding specific initiatives, clinical pharmacists have successfully identified patients on higher than recommended dosages of citalopram; they are working alongside prescribers to recommend ways to minimize the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities in these patients. Numerous prescribers have sought clinical pharmacists’ input to manage pharmacotherapy in their patients and to respond to patients’ questions on drug information.

The prospect of access to clinical pharmacist expertise in the outpatient setting was heralded with excitement, but the flow of referrals and consultations has been uneven. However simple the path for referral is, clinicians’ use of the system has been inconsistent—perhaps because of referrals’ passive, clinician-dependent nature. Educational outreach efforts often prompt a brief spike in referrals, only to be followed over time by a slow, steady drop-off. More active strategies will be needed, such as embedding the pharmacists as regular, active, visible members of the various clinical teams, and implementing a system in which patient record reviews are assigned to the pharmacists according to agreed-upon clusters of clinical criteria.

One of these tactics has, in the short term, showed success. Embedded in one of our newer clinics, which were designed to bridge primary and psychiatric care, clinical pharmacists are helping manage medically complicated patients. They assist with medication selection in light of drug interactions and medical comorbidities, conduct detailed medication histories, schedule follow-up visits to assess medication adherence and tolerability, and counsel patients experiencing insurance changes that make their medications less affordable. Integrating pharmacists in the new clinics has resulted in a steady flow of patient referrals and collaborative care work.

Clinical pharmacists are brainstorming with outpatient psychiatry leadership to build on these early successes. Ongoing communication and enhanced collaboration are essential, and can only improve the lives of our psychiatric patients.

For the future

Our partnership in ambulatory psychiatry was timed to occur during implementation of our health system’s new electronic health record initiative. Clinical pharmacists can play a key role in demonstrating use of the system to provide consistently accurate drug information to patients and to monitor patients receiving specific medications.

Development of ambulatory patient medication education groups, which has proved useful on the inpatient side, is another endeavor in the works. Integrating the clinical pharmacist with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and trainees on specific teams devoted to depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, perinatal mental health, and personality disorders also might prove to be a wide-ranging and promising strategy.

Enhancing the education and training experiences of residents, fellows, medical students, pharmacy students, and allied health professional learners present in our clinics is another exciting prospect. This cross-disciplinary training will yield a new generation of providers who will be more comfortable collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, all intent on providing high-quality, efficient care. We hope that, as these initiatives take root, we will recognize many opportunities to disseminate our collaborative efforts in scholarly venues, documenting and sharing the positive impact of our partnership.

Bottom Line

Because psychiatric outpatients present with challenging medical comorbidities and increasingly complex medication regimens, specialized clinical pharmacists can enrich the management team by offering essential monitoring and polypharmacy services, patient education and counseling, and cross-discipline training. At one academic treatment center, psychiatric and non-psychiatric practitioners are gradually buying in to these promising collaborative efforts.

Related Resources

• Board of Pharmacy Specialties. www.bpsweb.org/specialties/psychiatric.cfm.

• Abramowitz P. Ambulatory care pharmacy practice: The future is now. www.connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2014/05/14/ambulatory-care-pharmacy-practice-the-future-is-now.

Drug Brand Name

Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

In this article, we highlight key steps that were needed to integrate clinical pharmacy specialists at an academic ambulatory psychiatric and addiction treatment center that serves pediatric and adult populations. Academic stakeholders identified addition of pharmacy services as a strategic goal in an effort to maximize services offered by the center and increase patient access to care while aligning with the standards set out by the patient-centered medical home (PCMH) model.

We outline the role of clinical pharmacists in the care of adult patients in ambulatory psychiatry, illustrate opportunities to enhance patient care, point out possible challenges with implementation, and propose future initiatives to optimize the practitioner-pharmacist partnership.

Background: Role of ambulatory pharmacists in psychiatry

Clinical pharmacists’ role in the psychiatric ambulatory care setting generally is associated with positive outcomes. One study looking at a collaborative care model that utilized clinical pharmacist follow-up in managing major depressive disorder found that patients who received pharmacist intervention in the collaborative care model had, on average, a significantly higher adherence rate and patient satisfaction score than the “usual care” group.1 Within this study, patients in both groups experienced global clinical improvement with no significant difference; however, pharmacist interventions had a positive impact on several aspects of the care model, suggesting that pharmacists can be used effectively in ambulatory psychiatry.

Furthermore, a systematic study evaluating pharmacists’ impact on clinical and functional mental health outcomes identified 8 relevant studies conducted in the outpatient setting.2 Although interventions varied widely, most studies focused on pharmacists’ providing a combination of drug monitoring, treatment recommendations, and patient education. Outcomes were largely positive, including an overall reduction in number and dosage of psychiatric drugs, inferred cost savings, and significant improvements in the safe and efficacious use of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications.

These preliminary positive results require replication in larger, randomized cohorts. Additionally, the role of the pharmacist as medication manager in the collaborative care model requires further study. Results so far, however, indicate that pharmacists can have a positive impact on the care of ambulatory psychiatry patients. Nevertheless, there is still considerable need for ongoing exploration in this field.

Pre-implementation

The need for pharmacy services. Various initiatives and existing practices within our health care system have underscored the need for a psychiatric pharmacist in the outpatient setting (Table 1).

A board-certified psychiatric pharmacist (BCPP) possesses specialized knowledge about treating patients affected by psychiatric illnesses. BCPPs work with prescribers and members of other disciplines, such as nurses and social workers, to optimize drug treatment by making pharmacotherapeutic recommendations and providing appropriate monitoring to enhance patient satisfaction and quality of life.3,4

Existing relationship with pharmacy. Along with evidence to support the positive impact clinical pharmacists can have in caring for patients with mental illness in the outpatient setting, a strong existing relationship between the Department of Psychiatry and our adult inpatient psychiatric pharmacist helped make it possible to develop an ambulatory psychiatric pharmacist position.

Each day, the inpatient psychiatric pharmacist works closely with the attending psychiatrists and psychiatry residents to provide treatment recommendations and counseling services for patients on the unit. The psychiatry residents highly valued their experiences with the pharmacist in the inpatient setting and expressed disappointment that this collaborative relationship was no longer available after they transitioned into the ambulatory setting.

Further, by being involved in initiatives that were relevant to both inpatient and outpatient psychiatry, such as metabolic monitoring for patients taking atypical antipsychotics, the clinical pharmacist in inpatient psychiatry had the opportunity to interact with key stakeholders in both settings. As a result of these pre-existing collaborative relationships, many clinicians were eager to have pharmacists available as a resource for patient care in the outpatient setting.

Pharmacist perspective: Outreach to psychiatry leadershipRecognizing the incentives and opportunities inherent in our emerging health care system, pharmacists became integral members of the patient care team in the PCMH model. Thanks to this effort, we now have PCMH pharmacists at every primary care health center in our health system (14 sites), providing disease management programs and polypharmacy services.

PCMH pharmacists’ role in the primary care setting fueled interest from specialty services and created opportunities to extend our existing partnership in inpatient psychiatry. One such opportunity to demonstrate the expertise of a psychiatric pharmacist was fueled by the FDA’s citalopram dosing alert5 at a system-wide level. This warning emerged as a chance to showcase the skill set of psychiatric pharmacists and the pharmacists’ successes in our PCMH model. The partnership was extended to include the buy-in of ambulatory pharmacy leadership and key stakeholders in ambulatory psychiatry.

Initial meetings included ambulatory care site leadership in psychiatry to increase awareness and understanding of pharmacists’ potential role in direct patient care. Achieving site leadership support was critical to successful implementation of pharmacist services in psychiatry. We also obtained approval from the Chair of the Department of Psychiatry to elicit support from faculty group practice.

Psychiatry leadership perspective

As fiscal pressures intensify at academic health centers, it becomes increasingly important for resources to be used as efficiently and effectively as possible. As a greater percentage of mental health patients with more “straightforward,” less complex conditions are being managed by their primary care providers or nonprescribing psychotherapists, or both, the acuity and complexity of cases in patients who present to psychiatric clinics have intensified. This intensification of patient needs and clinical acuity is in heightened conflict with the ongoing demand for clinician productivity and efficiency.

Additionally, the need to provide care to a seemingly ever-growing number of moderately or severely ill patients during shorter, less frequent visits presents a daunting task for clinicians and clinical leaders. Collaborative care models appear to offer the best hope for managing the seemingly overwhelming demand for services.

In this model, the patient, who is the critical member of the team, is expected to become an “expert” on his or her illness and to partner with members of the multidisciplinary team; with this support, patients are encouraged to develop a broad range of self-management skills and strategies to manage their illness. We believe that clinical pharmacists can and should play a critical role, not only in delivering direct clinical services to patients but also in developing and devising the care models that will most effectively apply each team member’s unique set of knowledge, skills, and experience. Given the large percentage of our patients who have multiple medical comorbidities and who require complex medical and psychiatric medication regimens, the role of the pharmacist in reviewing, educating, and advising patients and other team members on these crucial pharmacy concerns will be paramount.

In light of these complex medication issues, pharmacists are uniquely positioned to serve as a liaison among the patient, the primary care provider, and other members of their treatment team. We anticipate that our ambulatory psychiatry pharmacists will greatly enhance the comfort and confidence of patients and their primary care providers during periods of care transition.

Potential roles for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry

One potential role for pharmacists in ambulatory psychiatry is to perform polypharmacy assessments of patients receiving complex medication regimens, prompted by physician referral. The poly pharmacy intake interview, performed to obtain an accurate medication list and to identify patients’ concerns about their medications, can be conducted in person or by telephone. Patients’ knowledge about medications and medication adherence are discussed, as are their perceptions of effectiveness and adverse effects.

After initial data gathering, pharmacists complete a review of the medications, identifying any problems associated with medication indication, efficacy, tolerance, or adverse effects, drug-drug interactions, drug-nutrient interactions, and nonadherence. Pharmacists work to reduce medication costs if that is a concern of the patient, because nonadherence can result. A medication care plan is then developed in consultation with the primary care provider; here, the medication list is reconciled, the electronic medical record is updated, and actions to address any medication-related problems are prioritized.

Other services that might be offered include:• group education classes, based on patient motivational interviewing strategies, to address therapeutic nonadherence and to improve understanding of their disease and treatment regimens• medication safety and monitoring• treatment intensification, as needed, following established protocols.

These are a few of the ways in which pharmacists can be relied on to expand and improve access to patient care services within ambulatory psychiatry. Key stakeholders anticipate development of newer ideas as the pharmacist’s role in ambulatory psychiatry is increasingly clarified.

Reimbursement model

In creating a role for pharmacy in ambulatory psychiatry, it was essential that the model be financially viable and appealing. Alongside its clinical model, our institution has developed a financial model to support the pharmacist’s role. The lump-sum payment to the health centers from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan afforded the ambulatory care clinics an opportunity to invest in PCMH pharmacists. This funding, and the reimbursement based on T-code billing (face-to-face visits and phone consultation) for depression and other conditions requiring chronic care, provides ongoing support. From our experience, understanding physician reimbursement models and identifying relevant changes in health care reform are necessary to integrate new providers, including pharmacists, into a team-based care model.

Implementation

Promoting pharmacy services. To foster anticipated collaboration with clinical pharmacists, the medical director of outpatient psychiatry disseminated an announcement to all providers regarding the investiture of clinical pharmacists to support patient care activities, education, and research. Clinicians were educated about the pharmacists’ potential roles and about guidelines and methods for referral. Use of our electronic health record system enabled us to establish a relatively simple referral process involving sharing electronic messages with our pharmacists.

Further, as part of the planned integration of clinical pharmacists in the ambulatory psychiatry setting, pharmacists met strategically with members of various disciplines, clinical programs, specialty clinic programs, and teams throughout the center. In addition to answering questions about the referral process, they emphasized the role of pharmacy and opportunities for collaboration.

Collaborating with others. Because the involvement of clinical pharmacists is unfamiliar to some practitioners in outpatient psychiatry, it is important to develop services without infringing on the roles other disciplines play. Indeed, a survey by Wheeler et al6 identified many concerns and potential boundaries among pharmacists, other providers, and patients. Concerns included confusion of practitioner roles and boundaries, a too-traditional perception of the pharmacist, and demonstration of competence.6

Early on, we developed a structured forum to discuss ongoing challenges and address issues related to the rapidly changing clinical landscape. During these discussions we conveyed that adding pharmacists to psychiatric services would be collaborative in nature and intended to augment existing services. This communication was pivotal to maintain the psychiatrist’s role as the ultimate prescriber and authority in the care of their patients; however, the pharmacist’s expertise, when sought, would help spur clinical and academic discussion that will benefit the patient. These discussions are paramount to achieving a productive, team-based approach, to overcome challenges, and to identify opportunities of value to our providers and patients (Box).

Work in progress

Implementing change in any clinical setting invariably creates challenges, and our endeavors to integrate clinical pharmacists into ambulatory psychiatry are no exception. We have identified several factors that we believe will optimize successful collaboration between pharmacy and ambulatory psychiatry (Table 2). Our primary challenge has been changing clinician behavior. Clinical practitioners can become too comfortable, wedded to their routines, and often are understandably resistant to change. Additionally, clinical systems often are inadvertently designed to obstruct change in ways that are not readily apparent. Efforts must be focused on behaviors and practices the clinical culture should encourage.

Regarding specific initiatives, clinical pharmacists have successfully identified patients on higher than recommended dosages of citalopram; they are working alongside prescribers to recommend ways to minimize the risk of heart rhythm abnormalities in these patients. Numerous prescribers have sought clinical pharmacists’ input to manage pharmacotherapy in their patients and to respond to patients’ questions on drug information.

The prospect of access to clinical pharmacist expertise in the outpatient setting was heralded with excitement, but the flow of referrals and consultations has been uneven. However simple the path for referral is, clinicians’ use of the system has been inconsistent—perhaps because of referrals’ passive, clinician-dependent nature. Educational outreach efforts often prompt a brief spike in referrals, only to be followed over time by a slow, steady drop-off. More active strategies will be needed, such as embedding the pharmacists as regular, active, visible members of the various clinical teams, and implementing a system in which patient record reviews are assigned to the pharmacists according to agreed-upon clusters of clinical criteria.

One of these tactics has, in the short term, showed success. Embedded in one of our newer clinics, which were designed to bridge primary and psychiatric care, clinical pharmacists are helping manage medically complicated patients. They assist with medication selection in light of drug interactions and medical comorbidities, conduct detailed medication histories, schedule follow-up visits to assess medication adherence and tolerability, and counsel patients experiencing insurance changes that make their medications less affordable. Integrating pharmacists in the new clinics has resulted in a steady flow of patient referrals and collaborative care work.

Clinical pharmacists are brainstorming with outpatient psychiatry leadership to build on these early successes. Ongoing communication and enhanced collaboration are essential, and can only improve the lives of our psychiatric patients.

For the future

Our partnership in ambulatory psychiatry was timed to occur during implementation of our health system’s new electronic health record initiative. Clinical pharmacists can play a key role in demonstrating use of the system to provide consistently accurate drug information to patients and to monitor patients receiving specific medications.

Development of ambulatory patient medication education groups, which has proved useful on the inpatient side, is another endeavor in the works. Integrating the clinical pharmacist with psychiatrists, psychologists, nurse practitioners, social workers, and trainees on specific teams devoted to depression, bipolar disorder, anxiety, perinatal mental health, and personality disorders also might prove to be a wide-ranging and promising strategy.

Enhancing the education and training experiences of residents, fellows, medical students, pharmacy students, and allied health professional learners present in our clinics is another exciting prospect. This cross-disciplinary training will yield a new generation of providers who will be more comfortable collaborating with colleagues from other disciplines, all intent on providing high-quality, efficient care. We hope that, as these initiatives take root, we will recognize many opportunities to disseminate our collaborative efforts in scholarly venues, documenting and sharing the positive impact of our partnership.

Bottom Line

Because psychiatric outpatients present with challenging medical comorbidities and increasingly complex medication regimens, specialized clinical pharmacists can enrich the management team by offering essential monitoring and polypharmacy services, patient education and counseling, and cross-discipline training. At one academic treatment center, psychiatric and non-psychiatric practitioners are gradually buying in to these promising collaborative efforts.

Related Resources

• Board of Pharmacy Specialties. www.bpsweb.org/specialties/psychiatric.cfm.

• Abramowitz P. Ambulatory care pharmacy practice: The future is now. www.connect.ashp.org/blogs/paul-abramowitz/2014/05/14/ambulatory-care-pharmacy-practice-the-future-is-now.

Drug Brand Name

Citalopram • Celexa

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175-1185.

2. Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(12):1634-1644.

3. Board of Pharmacy Specialties. http://www.bpsweb. org. Accessed June 4, 2014.

4. Cohen LJ. The role of neuropsychiatric pharmacists. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 19):54-57.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391. htm. Accessed June 4, 2014.

6. Wheeler A, Crump K, Lee M, et al. Collaborative prescribing: a qualitative exploration of a role for pharmacists in mental health. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(3):179-192.

1. Finley PR, Rens HR, Pont JT, et al. Impact of a collaborative care model on depression in a primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(9):1175-1185.

2. Finley PR, Crismon ML, Rush AJ. Evaluating the impact of pharmacists in mental health: a systematic review. Pharmacotherapy. 2003;23(12):1634-1644.

3. Board of Pharmacy Specialties. http://www.bpsweb. org. Accessed June 4, 2014.

4. Cohen LJ. The role of neuropsychiatric pharmacists. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(suppl 19):54-57.

5. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Abnormal heart rhythms associated with high doses of Celexa (citalopram hydrobromide). http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm297391. htm. Accessed June 4, 2014.

6. Wheeler A, Crump K, Lee M, et al. Collaborative prescribing: a qualitative exploration of a role for pharmacists in mental health. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2012;8(3):179-192.

Once-weekly exenatide can be especially useful to treat diabetes in schizophrenia

The incidence of diabetes in people with schizophrenia is 2- to 3-fold that of the general population—which has been attributed to several variables, including adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs, susceptibility related to mental illness, lifestyle, and social health determinants.1 Controlling diabetes is important because cardiovascular consequences of the disease contribute to the shortened life expectancy seen in patients with schizophrenia.2

The dosing frequency of a newer formulation of exenatide, a glucose-lowering drug that has been available for almost a decade, can help manage type 2 diabetes mellitus in your patient with schizophrenia.

What is the new formulation and why is it appealing?

Exenatide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist indicated as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2

diabetes mellitus. GLP-1 agonists lower the blood glucose level by enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and enhancing satiety. Exenatide was approved by the FDA

in 2005 as a twice-daily subcutaneous injection (brand name, Byetta); the once-weekly formulation, also for subcutaneous injection (brand name, Bydureon), was approved in 2012.

Practical use for psychiatric patients

Because psychiatric patients face medication adherence challenges, the once-

weekly formulation of exenatide is appealing. The patient or a member of his (her) care team can administer the once-weekly injection.

Practitioners might be concerned that patients with comorbid psychiatric illness and diabetes will overreact to an elevated blood glucose reading by overusing medications such as oral hypoglycemics and insulin. The fixed-dosage of weekly exenatide minimizes the risk that a patient will react to a single elevated blood glucose reading.

Exenatide can produce weight loss, which might benefit patients who suffer from the metabolic adverse effects of an atypical antipsychotic, including an elevated blood glucose level and weight gain.

Real-world application

We have used once-weekly exenatide successfully in a female patient with schizophrenia who was taking quetiapine and haloperidol, and had uncontrolled diabetes resulting from medication nonadherence and lack of insight into diabetes.

The patient’s hemoglobin A1c level remained at 8.8% (target A1c, <7%, as set by the American Diabetes Association), despite taking 3 oral diabetes medications at maximum dosage.

The care team determined that daily insulin injections were too risky, given the patient’s compulsive behavior; she had a history of medication overuse in response to significantly elevated blood glucose.

Once-weekly exenatide, however, was a feasible alternative. Three months after she was started on once-weekly exenatide, and with additional lifestyle modifications, her hemoglobin A1c level had fallen to 6.4%, without any hypoglycemic episodes.

Select patients carefully

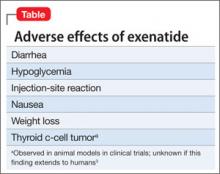

Exenatide is not a first-line therapy because of its potential side effects (Table), route of administration, and cost. Consider the once-weekly formulation of the drug on a patient-by-patient basis for patients with schizophrenia whose diabetes otherwise cannot be controlled.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. De Hert M, van Winkel R, Van Eyck D, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia over the course of the illness: a cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:14.

2. Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):83-88.

3. Bydureon [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

The incidence of diabetes in people with schizophrenia is 2- to 3-fold that of the general population—which has been attributed to several variables, including adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs, susceptibility related to mental illness, lifestyle, and social health determinants.1 Controlling diabetes is important because cardiovascular consequences of the disease contribute to the shortened life expectancy seen in patients with schizophrenia.2

The dosing frequency of a newer formulation of exenatide, a glucose-lowering drug that has been available for almost a decade, can help manage type 2 diabetes mellitus in your patient with schizophrenia.

What is the new formulation and why is it appealing?

Exenatide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist indicated as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2

diabetes mellitus. GLP-1 agonists lower the blood glucose level by enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and enhancing satiety. Exenatide was approved by the FDA

in 2005 as a twice-daily subcutaneous injection (brand name, Byetta); the once-weekly formulation, also for subcutaneous injection (brand name, Bydureon), was approved in 2012.

Practical use for psychiatric patients

Because psychiatric patients face medication adherence challenges, the once-

weekly formulation of exenatide is appealing. The patient or a member of his (her) care team can administer the once-weekly injection.

Practitioners might be concerned that patients with comorbid psychiatric illness and diabetes will overreact to an elevated blood glucose reading by overusing medications such as oral hypoglycemics and insulin. The fixed-dosage of weekly exenatide minimizes the risk that a patient will react to a single elevated blood glucose reading.

Exenatide can produce weight loss, which might benefit patients who suffer from the metabolic adverse effects of an atypical antipsychotic, including an elevated blood glucose level and weight gain.

Real-world application

We have used once-weekly exenatide successfully in a female patient with schizophrenia who was taking quetiapine and haloperidol, and had uncontrolled diabetes resulting from medication nonadherence and lack of insight into diabetes.

The patient’s hemoglobin A1c level remained at 8.8% (target A1c, <7%, as set by the American Diabetes Association), despite taking 3 oral diabetes medications at maximum dosage.

The care team determined that daily insulin injections were too risky, given the patient’s compulsive behavior; she had a history of medication overuse in response to significantly elevated blood glucose.

Once-weekly exenatide, however, was a feasible alternative. Three months after she was started on once-weekly exenatide, and with additional lifestyle modifications, her hemoglobin A1c level had fallen to 6.4%, without any hypoglycemic episodes.

Select patients carefully

Exenatide is not a first-line therapy because of its potential side effects (Table), route of administration, and cost. Consider the once-weekly formulation of the drug on a patient-by-patient basis for patients with schizophrenia whose diabetes otherwise cannot be controlled.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The incidence of diabetes in people with schizophrenia is 2- to 3-fold that of the general population—which has been attributed to several variables, including adverse effects of antipsychotic drugs, susceptibility related to mental illness, lifestyle, and social health determinants.1 Controlling diabetes is important because cardiovascular consequences of the disease contribute to the shortened life expectancy seen in patients with schizophrenia.2

The dosing frequency of a newer formulation of exenatide, a glucose-lowering drug that has been available for almost a decade, can help manage type 2 diabetes mellitus in your patient with schizophrenia.

What is the new formulation and why is it appealing?

Exenatide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist indicated as an adjunct to diet and exercise to improve glycemic control in adults with type 2

diabetes mellitus. GLP-1 agonists lower the blood glucose level by enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion, suppressing glucagon secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and enhancing satiety. Exenatide was approved by the FDA

in 2005 as a twice-daily subcutaneous injection (brand name, Byetta); the once-weekly formulation, also for subcutaneous injection (brand name, Bydureon), was approved in 2012.

Practical use for psychiatric patients

Because psychiatric patients face medication adherence challenges, the once-

weekly formulation of exenatide is appealing. The patient or a member of his (her) care team can administer the once-weekly injection.

Practitioners might be concerned that patients with comorbid psychiatric illness and diabetes will overreact to an elevated blood glucose reading by overusing medications such as oral hypoglycemics and insulin. The fixed-dosage of weekly exenatide minimizes the risk that a patient will react to a single elevated blood glucose reading.

Exenatide can produce weight loss, which might benefit patients who suffer from the metabolic adverse effects of an atypical antipsychotic, including an elevated blood glucose level and weight gain.

Real-world application

We have used once-weekly exenatide successfully in a female patient with schizophrenia who was taking quetiapine and haloperidol, and had uncontrolled diabetes resulting from medication nonadherence and lack of insight into diabetes.

The patient’s hemoglobin A1c level remained at 8.8% (target A1c, <7%, as set by the American Diabetes Association), despite taking 3 oral diabetes medications at maximum dosage.

The care team determined that daily insulin injections were too risky, given the patient’s compulsive behavior; she had a history of medication overuse in response to significantly elevated blood glucose.

Once-weekly exenatide, however, was a feasible alternative. Three months after she was started on once-weekly exenatide, and with additional lifestyle modifications, her hemoglobin A1c level had fallen to 6.4%, without any hypoglycemic episodes.

Select patients carefully

Exenatide is not a first-line therapy because of its potential side effects (Table), route of administration, and cost. Consider the once-weekly formulation of the drug on a patient-by-patient basis for patients with schizophrenia whose diabetes otherwise cannot be controlled.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. De Hert M, van Winkel R, Van Eyck D, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia over the course of the illness: a cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:14.

2. Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):83-88.

3. Bydureon [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

1. De Hert M, van Winkel R, Van Eyck D, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome and metabolic abnormalities in schizophrenia over the course of the illness: a cross-sectional study. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2006;2:14.

2. Laursen TM, Munk-Olsen T, Vestergaard M. Life expectancy and cardiovascular mortality in persons with schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2012;25(2):83-88.

3. Bydureon [package insert]. San Diego, CA: Amylin Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2012.

Smoking cessation: What to tell patients about over-the-counter treatments

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

• Over-the-counter smoking cessation products likely will be the most appropriate first-line choice for many individuals before trying prescription products.

• Instruct patients to avoid smoking while using nicotine replacement therapy and educate them about the immediate and long-term benefits of quitting.

• Encourage patients to seek psychosocial counseling along with pharmacotherapy.

• Urge patients to engage in other quitting strategies by referring them to online and telephone resources (Related Resources). Also, encourage them to attend follow-up appointments to assess cessation therapy.

Mr. T, age 56, has major depressive disorder that is well controlled with fluoxetine, 40 mg/d. He has smoked ≥1 packs of cigarettes per day for the last 25 years. On a recent visit, he indicates that he has begun using a 21-mg nicotine patch as advised by his pharmacist and that things are going OK, although he has had some “slip ups.” He is on week 7 of his quitting regimen and now is stepping down the patch dosage.

Upon further questioning he says that he has been cutting the 21-mg patches in half to save money. Mr. T also explains that occasionally he has given in to a strong urge to smoke because it was “too much to handle.” He states that he does not think this is a big deal because he uses electronic cigarettes and has heard that these products don’t contain “the bad cancer stuff.” At the end of Mr. T’s visit, he asks for something to help him sleep because has been unable to sleep consistently and has been having vivid dreams since starting the patch. He also wants to know how to reduce itching from the patch.

Approximately 46 million Americans smoke and cigarette smoking accounts for 1 of every 5 deaths in the United States each year.1 Since the advent of “Stop Smoking” campaigns, bans on smoking in public buildings, over-the-counter (OTC) nicotine replacement products, and Surgeon General recommendations, discussing smoking cessation with patients has become standard practice.

Research suggests that treatment to quit smoking should include a combination of pharmacotherapy and counseling, such as cognitive-behavioral strategies, support groups, and quitting hotlines.2 Pharmacotherapy consists of OTC nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) products and prescription medications. This article briefly highlights how to counsel patients about using OTC NRT products (Table 1).2-5 See Table 2 for a summary of prescription smoking cessation agents

Table 1

Over-the-counter nicotine replacement therapy products

| Product | Dosage | Side effects | Amount of nicotine | Costa | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nicotine transdermal patches | For patients who smoked >.5 PPD: 21 mg/d for 6 weeks; 14 mg/d for 2 weeks; 7 mg/d for 2 weeks | Local skin irritation, sleep disturbances, and vivid dreams | 7, 14, or 21 mg /d | 21 mg: $32 for 14 patches 14 mg: $32 for 14 patches 7 mg: $19 for 7 patches | Alternate sites. Do not cut. Do not leave on skin for longer than life of patch (24 hours). Washing, bathing, swimming are OK. Remove patch if undergoing MRI because of reports of burns |

| For patients who smoked <.5 PPD: 14 mg/d for 6 weeks; 7 mg/d for 2 weeks | |||||

| Nicotine polacrilex gum | For patients who smoked ≥1.25 PPD: 4 mg | Unpleasant taste, jaw soreness, hiccups, dyspepsia, hypersalivation, and nausea (from chewing gum too quickly) | 2 or 4 mg per piece | 4 mg: $50 for 170 pieces 2 mg: $50 for 170 pieces | Use “chew and park” method. As part of combination therapy, use only as needed. No more than 24 pieces per day; use caution with patients with jaw or mouth conditions |

| For patients who smoked <1.25 PPD: 2 mg Weeks 1 to 6: 1 piece every 1 to 2 hours Weeks 7 to 9: 1 piece every 2 to 4 hours Weeks 10 to 12: 1 piece every 4 to 8 hours | |||||

| Nicotine polacrilex lozenge | For patients who smoked 1st cigarette within 30 minutes of waking: 4 mg | Mouth irritation, hiccups, nausea, cough, and insomnia | 2 or 4 mg per lozenge | 4 mg: $43 for 72 lozenges 2 mg: $43 for 72 lozenges | Dissolve lozenge in mouth for 20 to 30 minutes. Rotate lozenge to different parts of mouth occasionally. Do not chew. No more than 5 lozenges in 6 hours or 20 per day. Same taper schedule as nicotine gum |

| For patients who smoked 1st cigarette >30 minutes after waking: 2 mg | |||||

| aAll prices taken from drugstore.com on September 26, 2011 PPD: packs per day Source: References 2-5 | |||||

Patches

Nicotine replacement patches are best used for maintenance treatment of nicotine cravings. They deliver a fixed amount of nicotine over 24 hours.3 Patches have a specially formulated transdermal matrix system and should not be cut. Doing so damages the drug delivery system and could lead to drug evaporation from the cut edges.4 Mr. T’s psychiatrist advises him not to cut patches but instead purchase the 14-mg patch because he is at this step of the smoking cessation regimen.

Skin irritation caused by adhesive is a common adverse event from nicotine patches. Rotating the location of each patch to a different hairless body area is the best way to prevent or combat skin irritation. If rotating the location of the patch does not relieve irritation, patients can apply a thin layer of an OTC hydrocortisone 1% cream to the affected site 2 to 4 times a day after gently washing the area.5 Instruct patients to avoid using occlusive dressings over the topical application.

Nicotine replacement patches also have been reported to cause vivid dreams and insomnia.3 These side effects may be caused by nighttime nicotine absorption, which might be avoided by switching to a different NRT product or removing the 24-hour patch when going to bed.4

Combining treatments

Many patients experience nicotine cravings while using the nicotine replacement patch. Stressful situations and events can trigger a patient’s desire for nicotine and withdrawal symptoms that a patch that delivers a continuous amount of nicotine over 24 hours cannot alleviate. Combining different forms of treatment could combat these symptoms.2,3,5

Combination therapy might consist of using sustained-release bupropion or a nicotine patch with rapid-acting NRT products such as a lozenge, gum, nasal spray, or inhaler. In Mr. T’s case, clinicians recommend that he use nicotine polacrilex gum in addition to the patch to quell his cravings. Also, he is instructed to stop using electronic cigarettes because they are considered tobacco products, are not regulated by the FDA, and may contain toxic substances.6

Instruct patients who use nicotine gum to employ the “chew and park” method.4 First, they should chew the gum very slowly until they notice a minty taste or tingling feeling, then “park” the gum between the cheek and gums for 1 to 2 minutes to allow nicotine to be absorbed across the gum lining. After 2 minutes or when tingling ceases, patients should slowly resume chewing until a tingling or minty taste returns and then “park” the gum again in a different area of the gums. Tell patients to repeat the “chew and park” method until there is no more taste or tingling (approximately 30 minutes). Explain that chewing the gum too fast may result in nausea or lightheadedness and patients should refrain from eating or drinking 15 minutes before or while using the gum. Mr. T is instructed to use the gum only when the urge to smoke is overbearing, and not regularly.

The nicotine polacrilex gum is more viscous than ordinary chewing gum and may stick to or possibly damage dental work such as fillings, dentures, crowns, and braces. An acceptable alternative is the nicotine polacrilex lozenge. Advise patients who want to try lozenges to:

- place the lozenge in the mouth and allow it to dissolve slowly over 20 to 30 minutes (during this time patients may experience a tingling sensation as nicotine is released)

- rotate the lozenge to different areas of the mouth every few minutes to lessen irritation

- avoid chewing or swallowing the lozenge because doing so will lead to improper release of nicotine and side effects, including nausea, hiccups, and heartburn

- refrain from eating or drinking 15 minutes before or while using the lozenge.

For many patients, the breadth of pharmacologic agents available for smoking cessation has made quitting a more attainable goal. OTC smoking cessation products are available in most drug stores, which gives smokers easy access to taking this important step. Counseling patients on the proper use of OTC products may help them successfully stop smoking.7

Although a patient’s medical history, including cardiac status, must be considered before starting specific agents, in many instances patient preference is the prevailing factor when choosing therapy. Often, the risks of continued smoking outweigh the risks of using smoking cessation products. OTC smoking cessation products may be an appropriate first-line treatment for many individuals before trying prescription medications, such as bupropion or varenicline.

For patients