User login

Videodermoscopy as a Novel Tool for Dermatologic Education

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

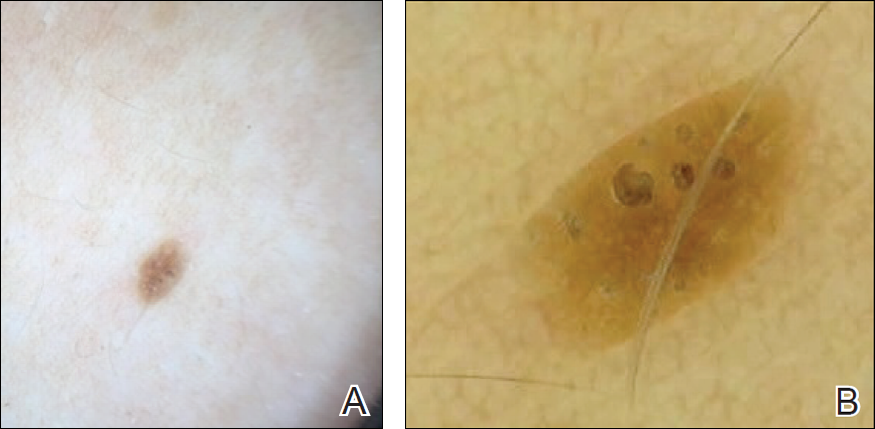

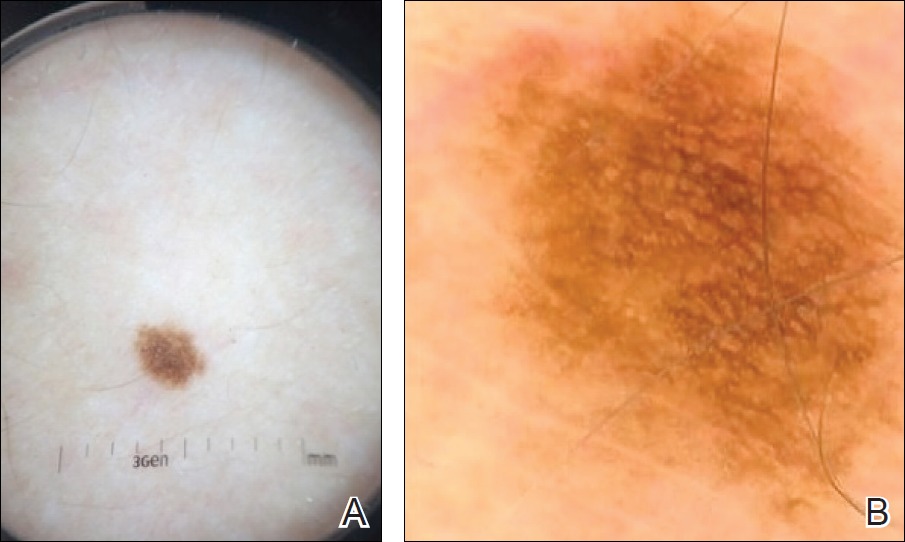

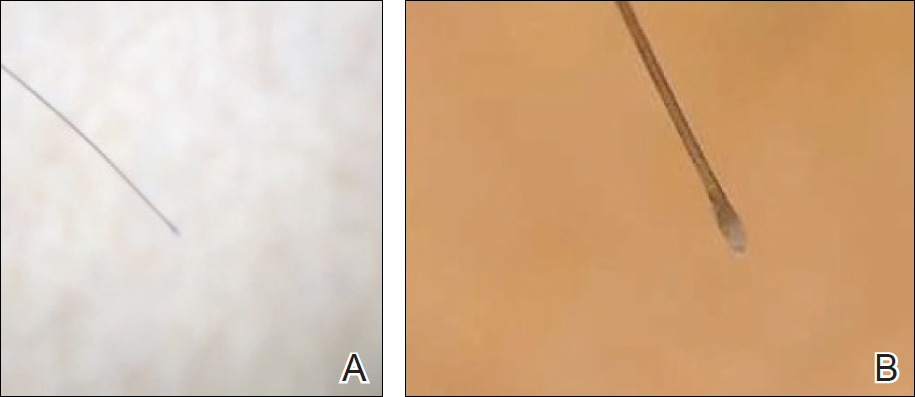

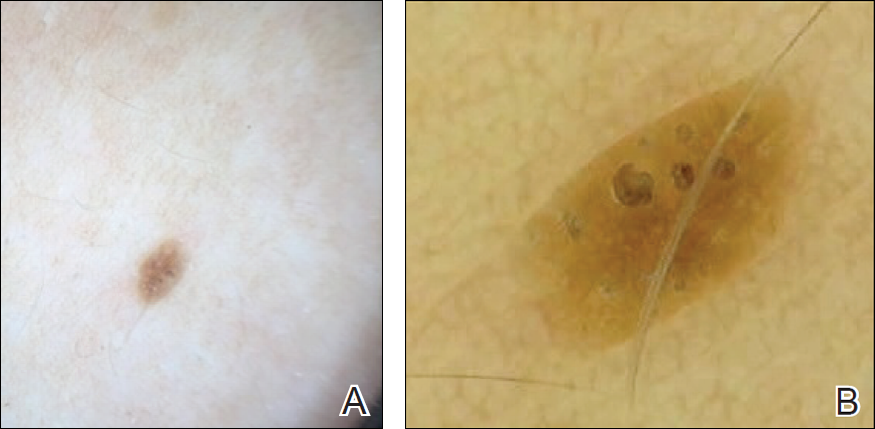

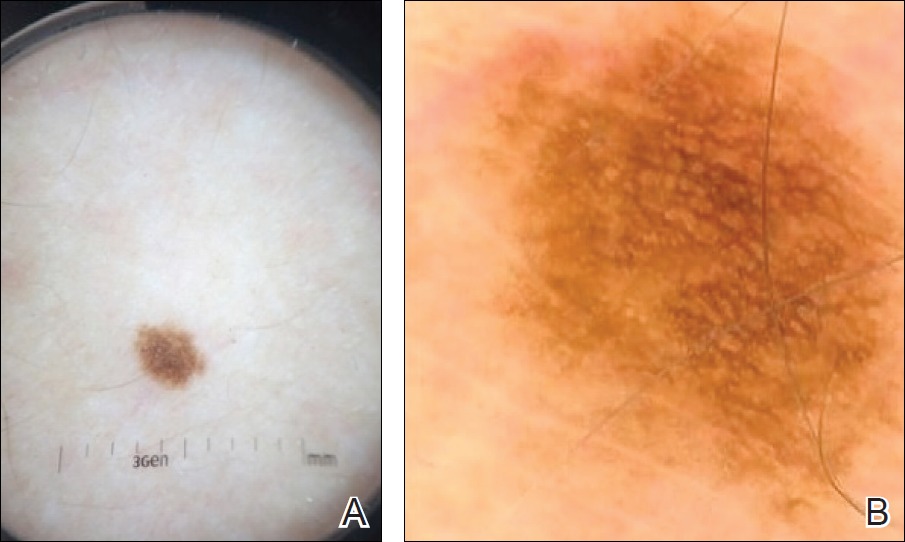

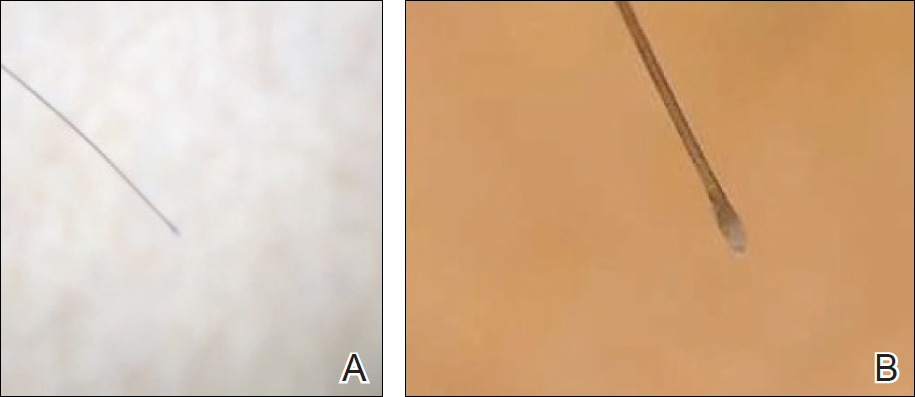

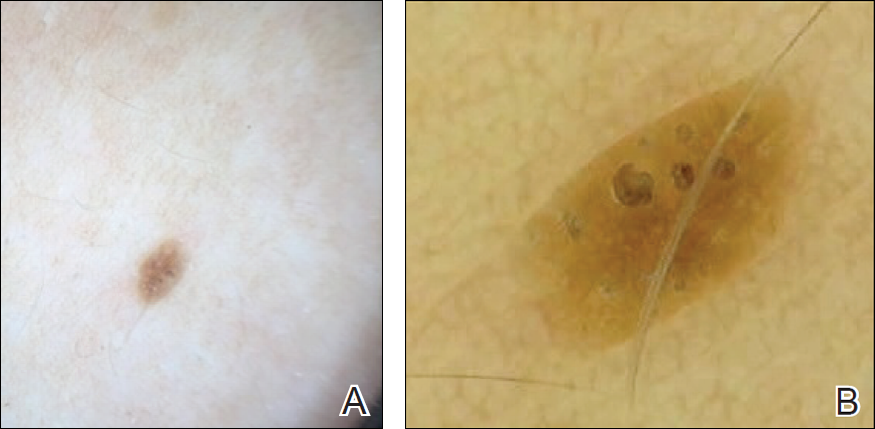

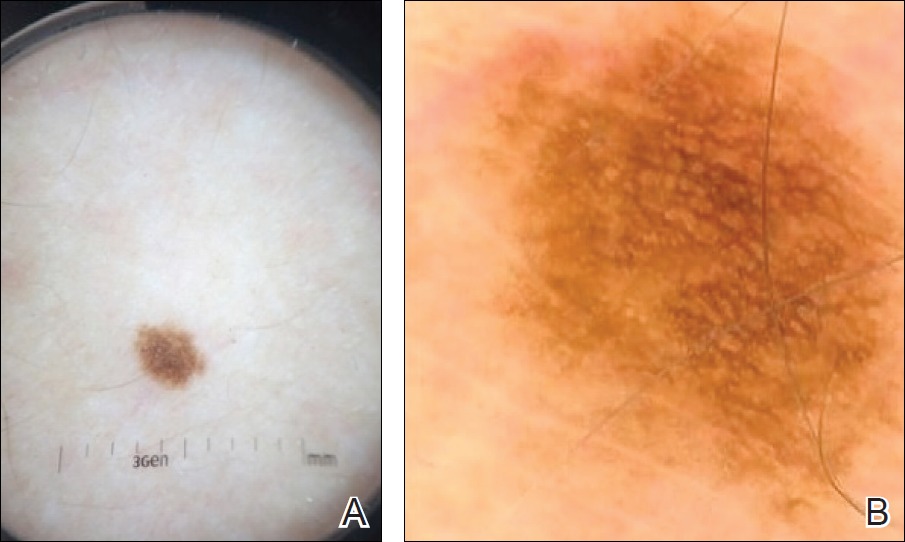

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

Dermoscopy, or the noninvasive in vivo examination of the epidermis and superficial dermis using magnification, facilitates the diagnosis of pigmented and nonpigmented skin lesions.1 Despite the benefit of dermoscopy in making early and accurate diagnoses of potentially life-limiting skin cancers, only 48% of dermatologists in the United States use dermoscopy in their practices.2 The most commonly cited reason for not using dermoscopy is lack of training.

Although the use of dermoscopy is associated with younger age and more recent graduation from residency compared to nonusers, dermatology resident physicians continue to receive limited training in dermoscopy.2 In a survey of 139 dermatology chief residents, 48% were not satisfied with the dermoscopy training that they had received during residency. Residents who received bedside instruction in dermoscopy reported greater satisfaction with their dermoscopy training compared to those who did not receive bedside instruction.3 This article provides a brief comparison of standard dermoscopy versus videodermoscopy for the instruction of trainees on common dermatologic diagnoses.

Bedside Dermoscopy

Standard optical dermatoscopes used for patient care and educational purposes typically incorporate 10-fold magnification and permit examination by a single viewer through a lens. With standard dermatoscopes, bedside dermoscopy instruction consists of the independent sequential viewing of skin lesions by instructors and trainees. Trainees must independently search for dermoscopic features noted by the instructor, which may be difficult for novice users. Simultaneous viewing of lesions would allow instructors to clearly indicate in real time pertinent dermoscopic features to their trainees.

Videodermatoscopes facilitate the simultaneous examination of cutaneous lesions by projecting the dermoscopic image onto a digital screen. Furthermore, these devices can incorporate magnifications of up to 200-fold or greater. In recent years, research pertaining to videodermoscopy has focused on the high magnification capabilities of these devices, specifically dermoscopic features that are visualized at magnifications greater than 10-fold, including the light brown nests of basal cell carcinomas that are seen at 50- to 70-fold magnification, twisted red capillary loops seen in active scalp psoriasis at 50-fold magnification, and longitudinal white indentations seen on nail plates affected by onychomycosis at 20-fold magnification.4-6 The potential value of videodermoscopy in medical education lies not only in the high magnification potential, which may make subtle dermoscopic findings more apparent to novice dermoscopists, but also in the ability to facilitate simultaneous dermoscopic examinations by instructors and trainees.

Educational Applications for Videodermoscopy

To illustrate the educational potential of videodermoscopy, images taken with a standard dermatoscope at 10-fold magnification are presented with videodermoscopic images taken at magnifications ranging from 60- to 185-fold (Figures 1–3). These examples demonstrate the potential for videodermoscopy to facilitate the visualization of subtle dermoscopic features by novice dermoscopists, relating to both the enhanced magnification potential and the potential for simultaneous rather than sequential examination.

Final Thoughts

High-magnification videodermoscopy may be a useful tool to further dermoscopic education. Videodermatoscopes vary in functionality and cost but are available at price points comparable to those of standard optical dermatoscopes. Owners of standard dermatoscopes can approximate some of the benefits of a digital videodermatoscope by using the standard dermatoscope in conjunction with a camera, including those integrated into mobile phones and tablets. By attaching the standard dermatoscope to a camera with a digital display, the digital zoom of the camera can be used to magnify the standard dermoscopic image, enhancing the ability of novice dermoscopists to visualize subtle findings. By presenting this magnified image on a digital display, dermoscopy instructors and trainees would be able to simultaneously view dermoscopic images of lesions, sometimes with magnifications comparable to videodermatoscopes.

In the setting of a dermatology residency program, videodermoscopy can be incorporated into bedside teaching with experienced dermoscopists and for the live presentation of dermoscopic features at departmental grand rounds. By facilitating the simultaneous, high-magnification and live viewing of skin lesions by dermoscopy instructors and trainees, digital videodermoscopy has the potential to address an area of weakness in dermatologic training.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

- Vestergaard ME, Macaskill P, Holt PE, et al. Dermoscopy compared with naked eye examination for the diagnosis of primary melanoma: a meta-analysis of studies performed in a clinical setting. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:669-676.

- Engasser HC, Warshaw EM. Dermatoscopy use by US dermatologists: a cross-sectional survey [published online July 8, 2010]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:412-419, 419.e1-419.e2.

- Wu TP, Newlove T, Smith L, et al. The importance of dedicated dermoscopy training during residency: a survey of US dermatology chief residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:1000-1005.

- Seidenari S, Bellucci C, Bassoli S, et al. High magnification digital dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma: a single-centre study on 400 cases. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:677-682.

- Ross EK, Vincenzi C, Tosti A. Videodermoscopy in the evaluation of hair and scalp disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55:799-806.

- Piraccini BM, Balestri R, Starace M, et al. Nail digital dermoscopy (onychoscopy) in the diagnosis of onychomycosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:509-513.

Resident Pearl

- Bedside dermoscopy training can be enhanced through the use of videodermoscopy, which permits simultaneous, high-magnification viewing.

Pedunculated Scrotal Nodule in an Elderly Male: A Rare Presentation of Trichoblastoma

To the Editor:

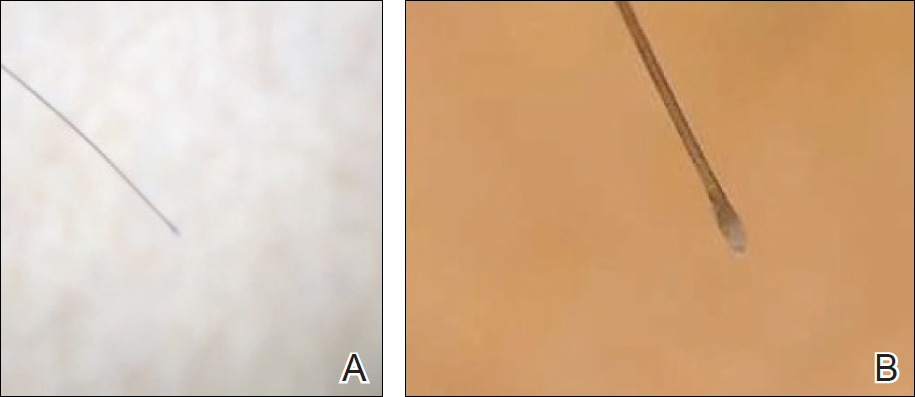

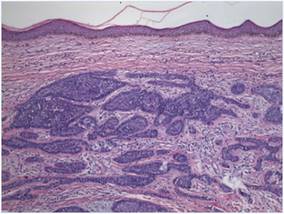

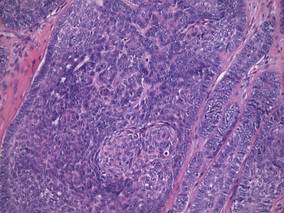

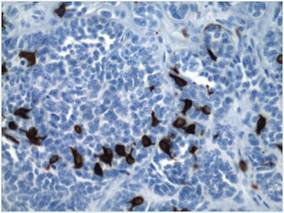

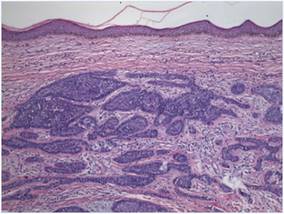

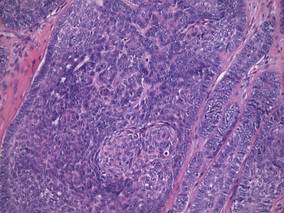

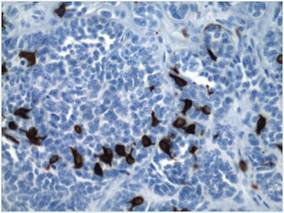

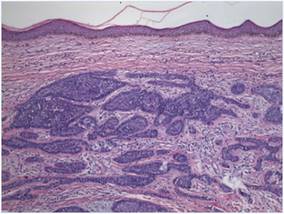

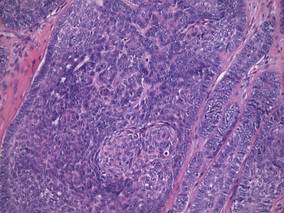

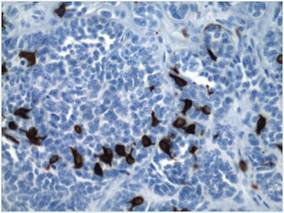

A 78-year-old man with no relevant dermatologic history presented for a routine skin examination. He had a large pedunculated nodule on the right scrotum that had been stable in size for more than 40 years. He reported the lesion had been diagnosed as a skin tag by his urologist 20 years prior and had remained asymptomatic in nature. On examination, a 2.5×1-cm, pedunculated, firm, rubbery nodule protruded from the anterior aspect of the right scrotal skin (Figure 1). Prominent telangiectases were noted on the surface of the lesion along with an irregular pigmented macule on the tip. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Given the pigmentation at the tip of the lesion, he was advised to have it completely excised to rule out melanocytic atypia. The lesion subsequently was excised under local anesthesia and the resulting defect was primarily closed. A group of basaloid lobules within the dermis with scant stroma was noted (Figure 2). There was no epidermal connection and retraction artifact was absent. The epidermis appeared normal, except for basilar pigmentation corresponding to the pigmented macule at the tip of the lesion. Higher magnification of one of the basaloid islands demonstrated a papillary mesenchymal body (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20 showed positive staining of Merkel cells colonizing the basaloid islands (Figure 4). A diagnosis of trichoblastoma was rendered. Two nodular basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) were seen on initial presentation, but he remained free of recurrence of the scrotal tumor at 2-year follow-up.

|

Figure 1. Firm, pedunculated, flesh-colored nodule on the scrotum. |

|

Figure 2. Basaloid tumor islands within the dermis with no epidermal connection (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 3. Papillary mesenchymal body adjacent to several dermal basaloid islands (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

Figure 4. Cytokeratin 20 immunohistochemical staining indicated Merkel cells within the basaloid islands (original magnification ×40). |

Trichoblastoma is a rare benign tumor with differentiation toward the primitive hair follicle. The lesion typically presents as a slow-growing, solitary, well-circumscribed nodule that typically measures up to 3 cm and is predominantly located on the head and neck with a predilection for the scalp. Rarely the lesion will appear on the trunk, proximal extremities, or perianal and genital regions.1 Trichoblastomas show no gender predilection and predominantly affect adults between the fifth and seventh decades of life. In children it is the most common neoplasm arising in preexisting nevus sebaceous (Jadassohn nevus).2 Several clinical variants of trichoblastoma have been described, including giant trichoblastoma, pigmented trichoblastoma, and subcutaneous trichoblastoma, among others.3

Histologically, these tumors are characterized by well-circumscribed basaloid islands in the dermis with peripheral palisading closely resembling BCCs and trichoepitheliomas. Unlike BCCs, retraction artifact in trichoblastoma is a rare finding, while papillary mesenchymal bodies and an increased number of Merkel cells characterize both trichoblastomas and trichoepitheliomas, as in our patient.4 Other histologic features include lack of epidermal connection and location in the deeper dermis and/or subcutis. There also are reported cases with sebaceous, pigmented, rippled patterns and clear cell differentiation on histology.3,5

The genetic basis for trichoblastoma remains unclear. Although these primitive hair follicle tumors share histologic features with BCC and trichoepithelioma, which have both demonstrated PTCH (patched) mutations, no classic mutations in the PTCH gene were seen in 11 cases of trichoblastoma.6 In contrast, there have been reports of trichoblastoma occurring in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and a case of a somatic CYLD (cylindromatosis) frameshift mutation in a trichoblastoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome7; however, the significance of CYLD mutation in thepathogenesis of trichoblastoma has not been fully elucidated.8

Trichoblastomas generally behave in an indolent asymptomatic manner, with malignant transformation being a rare occurrence.9 However, complete excision of these tumors is recommended given the potential for continued slow growth if incompletely removed. In the case of our patient, the lesion was completely excised at the outset. We plan to clinically monitor for evidence of disease recurrence as part of an annual full-body examination and have noted no evidence of recurrence in more than 2 years.

1. Brenn T, McKee PH. Tumors of the hair follicle. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1552-1557.

2. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:108-118.

3. Kim DW, Lee JH, Kim I. Giant melanotrichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:e37-e40.

4. Schulz T, Hartschuh W. Merkel cells are absent in basal cell carcinomas but frequently found in trichoblastomas. an immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:14-24.

5. Swick BL, Baum CL, Walling HW. Rippled-patterntrichoblastoma with apocrine differentiation arising in a nevus sebaceus: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:1200-1205.

6. Hafner C, Schmiemann V, Ruetten A, et al. PTCH mutations are not mainly involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic trichoblastomas [published online ahead of print June 26, 2007]. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1496-1500.

7. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

8. Kazakov DV, Schaller J, Vanecek T, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with a novel mutation in the CYLD gene and different types of somatic mutations in benign and malignant tumors [published online ahead of print February 4, 2010]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:886-890.

9. Schulz T, Proske S, Hartschuh W, et al. High-grade trichoblastic carcinoma arising in trichoblastoma: a rare adnexal neoplasm often showing metastatic spread. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:9-16

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man with no relevant dermatologic history presented for a routine skin examination. He had a large pedunculated nodule on the right scrotum that had been stable in size for more than 40 years. He reported the lesion had been diagnosed as a skin tag by his urologist 20 years prior and had remained asymptomatic in nature. On examination, a 2.5×1-cm, pedunculated, firm, rubbery nodule protruded from the anterior aspect of the right scrotal skin (Figure 1). Prominent telangiectases were noted on the surface of the lesion along with an irregular pigmented macule on the tip. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Given the pigmentation at the tip of the lesion, he was advised to have it completely excised to rule out melanocytic atypia. The lesion subsequently was excised under local anesthesia and the resulting defect was primarily closed. A group of basaloid lobules within the dermis with scant stroma was noted (Figure 2). There was no epidermal connection and retraction artifact was absent. The epidermis appeared normal, except for basilar pigmentation corresponding to the pigmented macule at the tip of the lesion. Higher magnification of one of the basaloid islands demonstrated a papillary mesenchymal body (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20 showed positive staining of Merkel cells colonizing the basaloid islands (Figure 4). A diagnosis of trichoblastoma was rendered. Two nodular basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) were seen on initial presentation, but he remained free of recurrence of the scrotal tumor at 2-year follow-up.

|

Figure 1. Firm, pedunculated, flesh-colored nodule on the scrotum. |

|

Figure 2. Basaloid tumor islands within the dermis with no epidermal connection (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 3. Papillary mesenchymal body adjacent to several dermal basaloid islands (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

Figure 4. Cytokeratin 20 immunohistochemical staining indicated Merkel cells within the basaloid islands (original magnification ×40). |

Trichoblastoma is a rare benign tumor with differentiation toward the primitive hair follicle. The lesion typically presents as a slow-growing, solitary, well-circumscribed nodule that typically measures up to 3 cm and is predominantly located on the head and neck with a predilection for the scalp. Rarely the lesion will appear on the trunk, proximal extremities, or perianal and genital regions.1 Trichoblastomas show no gender predilection and predominantly affect adults between the fifth and seventh decades of life. In children it is the most common neoplasm arising in preexisting nevus sebaceous (Jadassohn nevus).2 Several clinical variants of trichoblastoma have been described, including giant trichoblastoma, pigmented trichoblastoma, and subcutaneous trichoblastoma, among others.3

Histologically, these tumors are characterized by well-circumscribed basaloid islands in the dermis with peripheral palisading closely resembling BCCs and trichoepitheliomas. Unlike BCCs, retraction artifact in trichoblastoma is a rare finding, while papillary mesenchymal bodies and an increased number of Merkel cells characterize both trichoblastomas and trichoepitheliomas, as in our patient.4 Other histologic features include lack of epidermal connection and location in the deeper dermis and/or subcutis. There also are reported cases with sebaceous, pigmented, rippled patterns and clear cell differentiation on histology.3,5

The genetic basis for trichoblastoma remains unclear. Although these primitive hair follicle tumors share histologic features with BCC and trichoepithelioma, which have both demonstrated PTCH (patched) mutations, no classic mutations in the PTCH gene were seen in 11 cases of trichoblastoma.6 In contrast, there have been reports of trichoblastoma occurring in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and a case of a somatic CYLD (cylindromatosis) frameshift mutation in a trichoblastoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome7; however, the significance of CYLD mutation in thepathogenesis of trichoblastoma has not been fully elucidated.8

Trichoblastomas generally behave in an indolent asymptomatic manner, with malignant transformation being a rare occurrence.9 However, complete excision of these tumors is recommended given the potential for continued slow growth if incompletely removed. In the case of our patient, the lesion was completely excised at the outset. We plan to clinically monitor for evidence of disease recurrence as part of an annual full-body examination and have noted no evidence of recurrence in more than 2 years.

To the Editor:

A 78-year-old man with no relevant dermatologic history presented for a routine skin examination. He had a large pedunculated nodule on the right scrotum that had been stable in size for more than 40 years. He reported the lesion had been diagnosed as a skin tag by his urologist 20 years prior and had remained asymptomatic in nature. On examination, a 2.5×1-cm, pedunculated, firm, rubbery nodule protruded from the anterior aspect of the right scrotal skin (Figure 1). Prominent telangiectases were noted on the surface of the lesion along with an irregular pigmented macule on the tip. There was no inguinal lymphadenopathy. Given the pigmentation at the tip of the lesion, he was advised to have it completely excised to rule out melanocytic atypia. The lesion subsequently was excised under local anesthesia and the resulting defect was primarily closed. A group of basaloid lobules within the dermis with scant stroma was noted (Figure 2). There was no epidermal connection and retraction artifact was absent. The epidermis appeared normal, except for basilar pigmentation corresponding to the pigmented macule at the tip of the lesion. Higher magnification of one of the basaloid islands demonstrated a papillary mesenchymal body (Figure 3). Immunohistochemistry with cytokeratin 20 showed positive staining of Merkel cells colonizing the basaloid islands (Figure 4). A diagnosis of trichoblastoma was rendered. Two nodular basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) were seen on initial presentation, but he remained free of recurrence of the scrotal tumor at 2-year follow-up.

|

Figure 1. Firm, pedunculated, flesh-colored nodule on the scrotum. |

|

Figure 2. Basaloid tumor islands within the dermis with no epidermal connection (H&E, original magnification ×20). |

|

Figure 3. Papillary mesenchymal body adjacent to several dermal basaloid islands (H&E, original magnification ×40). |

|

Figure 4. Cytokeratin 20 immunohistochemical staining indicated Merkel cells within the basaloid islands (original magnification ×40). |

Trichoblastoma is a rare benign tumor with differentiation toward the primitive hair follicle. The lesion typically presents as a slow-growing, solitary, well-circumscribed nodule that typically measures up to 3 cm and is predominantly located on the head and neck with a predilection for the scalp. Rarely the lesion will appear on the trunk, proximal extremities, or perianal and genital regions.1 Trichoblastomas show no gender predilection and predominantly affect adults between the fifth and seventh decades of life. In children it is the most common neoplasm arising in preexisting nevus sebaceous (Jadassohn nevus).2 Several clinical variants of trichoblastoma have been described, including giant trichoblastoma, pigmented trichoblastoma, and subcutaneous trichoblastoma, among others.3

Histologically, these tumors are characterized by well-circumscribed basaloid islands in the dermis with peripheral palisading closely resembling BCCs and trichoepitheliomas. Unlike BCCs, retraction artifact in trichoblastoma is a rare finding, while papillary mesenchymal bodies and an increased number of Merkel cells characterize both trichoblastomas and trichoepitheliomas, as in our patient.4 Other histologic features include lack of epidermal connection and location in the deeper dermis and/or subcutis. There also are reported cases with sebaceous, pigmented, rippled patterns and clear cell differentiation on histology.3,5

The genetic basis for trichoblastoma remains unclear. Although these primitive hair follicle tumors share histologic features with BCC and trichoepithelioma, which have both demonstrated PTCH (patched) mutations, no classic mutations in the PTCH gene were seen in 11 cases of trichoblastoma.6 In contrast, there have been reports of trichoblastoma occurring in Brooke-Spiegler syndrome and a case of a somatic CYLD (cylindromatosis) frameshift mutation in a trichoblastoma in a patient with Brooke-Spiegler syndrome7; however, the significance of CYLD mutation in thepathogenesis of trichoblastoma has not been fully elucidated.8

Trichoblastomas generally behave in an indolent asymptomatic manner, with malignant transformation being a rare occurrence.9 However, complete excision of these tumors is recommended given the potential for continued slow growth if incompletely removed. In the case of our patient, the lesion was completely excised at the outset. We plan to clinically monitor for evidence of disease recurrence as part of an annual full-body examination and have noted no evidence of recurrence in more than 2 years.

1. Brenn T, McKee PH. Tumors of the hair follicle. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1552-1557.

2. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:108-118.

3. Kim DW, Lee JH, Kim I. Giant melanotrichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:e37-e40.

4. Schulz T, Hartschuh W. Merkel cells are absent in basal cell carcinomas but frequently found in trichoblastomas. an immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:14-24.

5. Swick BL, Baum CL, Walling HW. Rippled-patterntrichoblastoma with apocrine differentiation arising in a nevus sebaceus: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:1200-1205.

6. Hafner C, Schmiemann V, Ruetten A, et al. PTCH mutations are not mainly involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic trichoblastomas [published online ahead of print June 26, 2007]. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1496-1500.

7. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

8. Kazakov DV, Schaller J, Vanecek T, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with a novel mutation in the CYLD gene and different types of somatic mutations in benign and malignant tumors [published online ahead of print February 4, 2010]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:886-890.

9. Schulz T, Proske S, Hartschuh W, et al. High-grade trichoblastic carcinoma arising in trichoblastoma: a rare adnexal neoplasm often showing metastatic spread. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:9-16

1. Brenn T, McKee PH. Tumors of the hair follicle. In: McKee PH, Calonje E, Granter SR, eds. Pathology of the Skin With Clinical Correlations. 3rd ed. London, England: Elsevier Mosby; 2005:1552-1557.

2. Jaqueti G, Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Trichoblastoma is the most common neoplasm developed in nevus sebaceous of Jadassohn: a clinicopathologic study of series of 155 cases. Am J Dermatopathol. 2000;22:108-118.

3. Kim DW, Lee JH, Kim I. Giant melanotrichoblastoma. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:e37-e40.

4. Schulz T, Hartschuh W. Merkel cells are absent in basal cell carcinomas but frequently found in trichoblastomas. an immunohistochemical study. J Cutan Pathol. 1997;24:14-24.

5. Swick BL, Baum CL, Walling HW. Rippled-patterntrichoblastoma with apocrine differentiation arising in a nevus sebaceus: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2009;36:1200-1205.

6. Hafner C, Schmiemann V, Ruetten A, et al. PTCH mutations are not mainly involved in the pathogenesis of sporadic trichoblastomas [published online ahead of print June 26, 2007]. Hum Pathol. 2007;38:1496-1500.

7. Kazakov DV, Soukup R, Mukensnabl P, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with combined lesions containing cylindromatous, spiradenomatous, trichoblastomatous, and sebaceous differentiation. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:27-33.

8. Kazakov DV, Schaller J, Vanecek T, et al. Brooke-Spiegler syndrome: report of a case with a novel mutation in the CYLD gene and different types of somatic mutations in benign and malignant tumors [published online ahead of print February 4, 2010]. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:886-890.

9. Schulz T, Proske S, Hartschuh W, et al. High-grade trichoblastic carcinoma arising in trichoblastoma: a rare adnexal neoplasm often showing metastatic spread. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:9-16