User login

Hospital employment or physician-led ACO?

Primary care physicians around the country are facing the largest decision of their lives: Do I stay independent and maybe form an accountable care organization with other independent physicians, or do I become an employee of a hospital or health system?

As accountable care is taking hold, new data may alter historic thinking on this "bet-the-practice" question.

Tired of being overworked, undersatisfied, and overwhelmed with growing regulatory requirements, many primary care physicians have sought the security and strength of hospital employment. They say the pressures to invest in technology, billing, coding, and continued reimbursement pressures are just too great.

Yet, the majority of these physicians miss their days of self-employed autonomy, are on average less productive, and worry that the clocks on their compensation guarantees are ticking down.

Most of the moves by your colleagues, and perhaps you, to hospital employment have been defensive. It was just no longer feasible to stay afloat in the current fee-for-service system. You cannot work any harder, faster, or cheaper. You can no longer spend satisfactory time with your patients.

On the other hand, some of you may have joined a hospital or health system to be proactive and gain a solid platform to prepare for the new value-based payment era.

You may have envisioned being integrated with a critical mass of like-minded physicians and facilities, aided by advanced population management tools and a strong balance sheet, and all linked together on the hospital’s health information technology platform. You read that primary care should be in a leadership position and financially incentivized in any accountable care organization – including a hospital’s. Independent physicians could theoretically form ACOs, too, but lack the up-front capital, know-how, and any spare intellectual bandwidth to do so.

So, from a strategic perspective, becoming employed with other physicians by a health system seemed the way to go.

The pace has quickened of health care’s movement away from fee for service or "pay for volume" to payment for better outcomes at lower overall costs, or "pay for value." The factors that applied to the decision to become employed in the fee-for-service era may be yielding to those in the accountable care era sooner than anticipated.

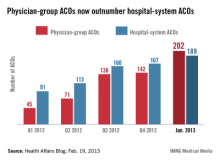

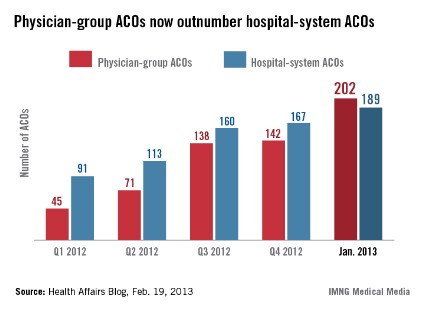

Independent physician-led ACOs appear to be adapting better than hospitals to this change. Although much better prepared fiscally, hospitals are conflicted, or at least hesitant, to make this switch, because much of the savings comes from avoidable admissions and readmissions. On the other hand, emerging data and experience are showing that physician-led ACOs can be very successful.

There are some very integrated and successful hospital-led ACOs or other value-delivery hospital/physician models. In fact, I believe that if the hospital is willing to right-size and truly commit to value, it can be the most successful model.

However, many physicians signed volume-only physician work relative value unit (wRVU) compensation formulas in their hospital employment agreements, with no incentive payments for value. They have not been involved as partners, much less leaders, in any ACO planning. Even though the fee-for-service days are waning and strains are showing for many hospitals that are not adapting, for many employed physicians, the pace of preparedness for the accountable care era has been disappointing.

New data show that while most of the early ACOs in the Medicare Shared Savings Program were hospital led, there are now more physician-led ACOs than any other. At the same time, early results of some modest primary care–only ACOs have been exciting. The rural primary care physician ACO previously reported on in this column, Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance in McAllen, Tex., is preliminarily looking at 90th-percentile quality results and more than $500,000 in (unofficial) savings per physician in their first year under the Medicare Shared Savings Program.

In fact, in a May 14, 2014, article in JAMA, its authors stated: "Even though most adult primary care physicians may not realize it, they each can be seen as a chief executive officer (CEO) in charge of approximately $10 million in annual revenue" (JAMA 2014;311:1855-6). They noted that primary care receives only 5% of that spending, but can control much of the average of $5,000 in annual spending of their 2,000 or so patients. The independent physician-led Palm Beach ACO is cited as an example, with $22 million in savings their first year. The authors recommend physician-led ACOs as the best way to leverage that "CEO" power.

These new success lessons are being learned and need to be shared. Primary care physicians need to understand that the risk of change is now much less than the risk of maintaining the status quo. You need transparency regarding the realities of all your choices, including hospital employment and physician ACOs.

As readers of this column know, I heartily endorse the trend recognized in the JAMA article: "[A]n increasing number of primary care physicians see physician-led ACOs as a powerful opportunity to retain their autonomy and make a positive difference for their patient – as well as their practices’ bottom lines."

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

Primary care physicians around the country are facing the largest decision of their lives: Do I stay independent and maybe form an accountable care organization with other independent physicians, or do I become an employee of a hospital or health system?

As accountable care is taking hold, new data may alter historic thinking on this "bet-the-practice" question.

Tired of being overworked, undersatisfied, and overwhelmed with growing regulatory requirements, many primary care physicians have sought the security and strength of hospital employment. They say the pressures to invest in technology, billing, coding, and continued reimbursement pressures are just too great.

Yet, the majority of these physicians miss their days of self-employed autonomy, are on average less productive, and worry that the clocks on their compensation guarantees are ticking down.

Most of the moves by your colleagues, and perhaps you, to hospital employment have been defensive. It was just no longer feasible to stay afloat in the current fee-for-service system. You cannot work any harder, faster, or cheaper. You can no longer spend satisfactory time with your patients.

On the other hand, some of you may have joined a hospital or health system to be proactive and gain a solid platform to prepare for the new value-based payment era.

You may have envisioned being integrated with a critical mass of like-minded physicians and facilities, aided by advanced population management tools and a strong balance sheet, and all linked together on the hospital’s health information technology platform. You read that primary care should be in a leadership position and financially incentivized in any accountable care organization – including a hospital’s. Independent physicians could theoretically form ACOs, too, but lack the up-front capital, know-how, and any spare intellectual bandwidth to do so.

So, from a strategic perspective, becoming employed with other physicians by a health system seemed the way to go.

The pace has quickened of health care’s movement away from fee for service or "pay for volume" to payment for better outcomes at lower overall costs, or "pay for value." The factors that applied to the decision to become employed in the fee-for-service era may be yielding to those in the accountable care era sooner than anticipated.

Independent physician-led ACOs appear to be adapting better than hospitals to this change. Although much better prepared fiscally, hospitals are conflicted, or at least hesitant, to make this switch, because much of the savings comes from avoidable admissions and readmissions. On the other hand, emerging data and experience are showing that physician-led ACOs can be very successful.

There are some very integrated and successful hospital-led ACOs or other value-delivery hospital/physician models. In fact, I believe that if the hospital is willing to right-size and truly commit to value, it can be the most successful model.

However, many physicians signed volume-only physician work relative value unit (wRVU) compensation formulas in their hospital employment agreements, with no incentive payments for value. They have not been involved as partners, much less leaders, in any ACO planning. Even though the fee-for-service days are waning and strains are showing for many hospitals that are not adapting, for many employed physicians, the pace of preparedness for the accountable care era has been disappointing.

New data show that while most of the early ACOs in the Medicare Shared Savings Program were hospital led, there are now more physician-led ACOs than any other. At the same time, early results of some modest primary care–only ACOs have been exciting. The rural primary care physician ACO previously reported on in this column, Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance in McAllen, Tex., is preliminarily looking at 90th-percentile quality results and more than $500,000 in (unofficial) savings per physician in their first year under the Medicare Shared Savings Program.

In fact, in a May 14, 2014, article in JAMA, its authors stated: "Even though most adult primary care physicians may not realize it, they each can be seen as a chief executive officer (CEO) in charge of approximately $10 million in annual revenue" (JAMA 2014;311:1855-6). They noted that primary care receives only 5% of that spending, but can control much of the average of $5,000 in annual spending of their 2,000 or so patients. The independent physician-led Palm Beach ACO is cited as an example, with $22 million in savings their first year. The authors recommend physician-led ACOs as the best way to leverage that "CEO" power.

These new success lessons are being learned and need to be shared. Primary care physicians need to understand that the risk of change is now much less than the risk of maintaining the status quo. You need transparency regarding the realities of all your choices, including hospital employment and physician ACOs.

As readers of this column know, I heartily endorse the trend recognized in the JAMA article: "[A]n increasing number of primary care physicians see physician-led ACOs as a powerful opportunity to retain their autonomy and make a positive difference for their patient – as well as their practices’ bottom lines."

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

Primary care physicians around the country are facing the largest decision of their lives: Do I stay independent and maybe form an accountable care organization with other independent physicians, or do I become an employee of a hospital or health system?

As accountable care is taking hold, new data may alter historic thinking on this "bet-the-practice" question.

Tired of being overworked, undersatisfied, and overwhelmed with growing regulatory requirements, many primary care physicians have sought the security and strength of hospital employment. They say the pressures to invest in technology, billing, coding, and continued reimbursement pressures are just too great.

Yet, the majority of these physicians miss their days of self-employed autonomy, are on average less productive, and worry that the clocks on their compensation guarantees are ticking down.

Most of the moves by your colleagues, and perhaps you, to hospital employment have been defensive. It was just no longer feasible to stay afloat in the current fee-for-service system. You cannot work any harder, faster, or cheaper. You can no longer spend satisfactory time with your patients.

On the other hand, some of you may have joined a hospital or health system to be proactive and gain a solid platform to prepare for the new value-based payment era.

You may have envisioned being integrated with a critical mass of like-minded physicians and facilities, aided by advanced population management tools and a strong balance sheet, and all linked together on the hospital’s health information technology platform. You read that primary care should be in a leadership position and financially incentivized in any accountable care organization – including a hospital’s. Independent physicians could theoretically form ACOs, too, but lack the up-front capital, know-how, and any spare intellectual bandwidth to do so.

So, from a strategic perspective, becoming employed with other physicians by a health system seemed the way to go.

The pace has quickened of health care’s movement away from fee for service or "pay for volume" to payment for better outcomes at lower overall costs, or "pay for value." The factors that applied to the decision to become employed in the fee-for-service era may be yielding to those in the accountable care era sooner than anticipated.

Independent physician-led ACOs appear to be adapting better than hospitals to this change. Although much better prepared fiscally, hospitals are conflicted, or at least hesitant, to make this switch, because much of the savings comes from avoidable admissions and readmissions. On the other hand, emerging data and experience are showing that physician-led ACOs can be very successful.

There are some very integrated and successful hospital-led ACOs or other value-delivery hospital/physician models. In fact, I believe that if the hospital is willing to right-size and truly commit to value, it can be the most successful model.

However, many physicians signed volume-only physician work relative value unit (wRVU) compensation formulas in their hospital employment agreements, with no incentive payments for value. They have not been involved as partners, much less leaders, in any ACO planning. Even though the fee-for-service days are waning and strains are showing for many hospitals that are not adapting, for many employed physicians, the pace of preparedness for the accountable care era has been disappointing.

New data show that while most of the early ACOs in the Medicare Shared Savings Program were hospital led, there are now more physician-led ACOs than any other. At the same time, early results of some modest primary care–only ACOs have been exciting. The rural primary care physician ACO previously reported on in this column, Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance in McAllen, Tex., is preliminarily looking at 90th-percentile quality results and more than $500,000 in (unofficial) savings per physician in their first year under the Medicare Shared Savings Program.

In fact, in a May 14, 2014, article in JAMA, its authors stated: "Even though most adult primary care physicians may not realize it, they each can be seen as a chief executive officer (CEO) in charge of approximately $10 million in annual revenue" (JAMA 2014;311:1855-6). They noted that primary care receives only 5% of that spending, but can control much of the average of $5,000 in annual spending of their 2,000 or so patients. The independent physician-led Palm Beach ACO is cited as an example, with $22 million in savings their first year. The authors recommend physician-led ACOs as the best way to leverage that "CEO" power.

These new success lessons are being learned and need to be shared. Primary care physicians need to understand that the risk of change is now much less than the risk of maintaining the status quo. You need transparency regarding the realities of all your choices, including hospital employment and physician ACOs.

As readers of this column know, I heartily endorse the trend recognized in the JAMA article: "[A]n increasing number of primary care physicians see physician-led ACOs as a powerful opportunity to retain their autonomy and make a positive difference for their patient – as well as their practices’ bottom lines."

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612.

Anatomy of an independent primary care ACO, part 2

In our last column, we highlighted the Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance, an accountable care organization in McAllen, Tex., composed of 14 independent primary care physicians in 11 practices. As primary care physicians, the RGVHA providers realized the potential for a primary care ACO to generate savings from value-based care.

Because RGVHA is a network model ACO – the physicians stay in their separate independent practices but participate in the ACO through contracts – RGVHA needed a way to manage the ACO data collection, sorting, and reporting requirements in an efficient and effective manner.

Fortunately, Dr. Gretchen Hoyle of MD Online Solutions was able to tailor a data management solution for RGVHA. In addition, Dr. Hoyle helps interpret the data and leads a weekly data-driven staff conference call with the ACO’s nurse care coordinators.

Through Dr. Hoyle’s data collection and interpretation work with RGVHA, the ACO now has concrete data showing utilization trends and patterns. The most positive result has been the demonstrated benefit of nurse care coordinators, who work with patients in the post–acute care settings between their office visits.

In fact, care coordinators have proved to be RGVHA’s secret weapon, because their work has been invaluable in managing patients with chronic conditions between provider appointments.

Conversely, the data have revealed a pattern of overuse of home health care services, which helps contribute to higher care costs overall, making home health the biggest disappointment.

The secret weapon

As Dr. Hoyle so aptly said, "To become a fully functioning ACO, an organization must be able to address both sides of the ACO ‘coin’: quality improvement and cost control." Care coordinators have the capacity to address both concerns.

Within RGVHA, care coordinators have performed chart reviews that identify the ACO’s current performance according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ quality standards. This is the first secret weapon for a small primary care ACO.

This data collection helps RGVHA fill in knowledge gaps as it works toward having a fully integrated electronic health records system. In turn, it helps the care coordinators identify the strengths and weaknesses of each of the participating ACO providers. This ensures that weaknesses can be addressed in a timely fashion. In addition, the chart reviews help identify documentation issues. Documentation is critical to meeting CMS benchmarks, which ultimately helps determine the amount of shared savings for an ACO.

In addition, the data have proved crucial to being able to rank patients by cost. That has allowed RGVHA to identify the top 10% of patients whose care accounts for 50% of the total care costs in the ACO. This information allows providers to understand which patients and types of patients are more expensive, and who can benefit most from intense care coordination and/or longer visits with RGVHA’s primary care doctors.

Claims data show that even a small amount of additional time and care coordination outside of the clinic setting curbs utilization for the most complex patients and saves money. Most important, care coordinators help providers focus their time and energy where it can have the most impact.

The biggest disappointment

Shortly after RGVHA began reviewing patient claims data, home health care costs per patient emerged as one of the greatest cost outliers. The data revealed that providers outside of the ACO were prescribing home health at much higher rates than providers within the ACO. A subsequent gap analysis showed that home health was a prime opportunity target for RGVHA.

As RGVHA developed a strategy to address the overutilization and extremely high home health costs for their patient population, the providers faced their biggest disappointment to date: The Medicare Shared Savings Program regulations only permit ACOs to "ask" that providers outside the ACO coordinate patient care with doctors inside the ACO, not "tell" the providers that they must collaborate in delivering evidence-based, high-value care.

So, RGVHA decided to use those data as the starting point to reach out to those providers.

Dr. Hoyle helped RGVHA identify the amount of home health care generated by each specific agency and ordering physician. That information was used to craft a targeted letter to each provider outside the ACO requesting and encouraging their collaboration and cooperation in the development of a care plan for each home health patient.

Now, several months later, home health care overutilization and costs are beginning to decline, as patient care is monitored by RGVHA and appropriately coordinated among each ACO patient’s team of care providers.

RGVHA’s biggest concern has now become one of its biggest assets. The ACO doctors finally feel empowered in their ability to impact the quality and costs of patient care. Furthermore, they are excited they are getting paid for doing what they are trained to do: provide high-value care to their patients.

The good news is that, when properly informed and invited to help shape high-value patient care, providers want to and will do the right thing.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. Mr. Bobbitt is grateful for the excellent lead research and drafting of this article by Ms. Poe. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or at 919-821-6612.

In our last column, we highlighted the Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance, an accountable care organization in McAllen, Tex., composed of 14 independent primary care physicians in 11 practices. As primary care physicians, the RGVHA providers realized the potential for a primary care ACO to generate savings from value-based care.

Because RGVHA is a network model ACO – the physicians stay in their separate independent practices but participate in the ACO through contracts – RGVHA needed a way to manage the ACO data collection, sorting, and reporting requirements in an efficient and effective manner.

Fortunately, Dr. Gretchen Hoyle of MD Online Solutions was able to tailor a data management solution for RGVHA. In addition, Dr. Hoyle helps interpret the data and leads a weekly data-driven staff conference call with the ACO’s nurse care coordinators.

Through Dr. Hoyle’s data collection and interpretation work with RGVHA, the ACO now has concrete data showing utilization trends and patterns. The most positive result has been the demonstrated benefit of nurse care coordinators, who work with patients in the post–acute care settings between their office visits.

In fact, care coordinators have proved to be RGVHA’s secret weapon, because their work has been invaluable in managing patients with chronic conditions between provider appointments.

Conversely, the data have revealed a pattern of overuse of home health care services, which helps contribute to higher care costs overall, making home health the biggest disappointment.

The secret weapon

As Dr. Hoyle so aptly said, "To become a fully functioning ACO, an organization must be able to address both sides of the ACO ‘coin’: quality improvement and cost control." Care coordinators have the capacity to address both concerns.

Within RGVHA, care coordinators have performed chart reviews that identify the ACO’s current performance according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ quality standards. This is the first secret weapon for a small primary care ACO.

This data collection helps RGVHA fill in knowledge gaps as it works toward having a fully integrated electronic health records system. In turn, it helps the care coordinators identify the strengths and weaknesses of each of the participating ACO providers. This ensures that weaknesses can be addressed in a timely fashion. In addition, the chart reviews help identify documentation issues. Documentation is critical to meeting CMS benchmarks, which ultimately helps determine the amount of shared savings for an ACO.

In addition, the data have proved crucial to being able to rank patients by cost. That has allowed RGVHA to identify the top 10% of patients whose care accounts for 50% of the total care costs in the ACO. This information allows providers to understand which patients and types of patients are more expensive, and who can benefit most from intense care coordination and/or longer visits with RGVHA’s primary care doctors.

Claims data show that even a small amount of additional time and care coordination outside of the clinic setting curbs utilization for the most complex patients and saves money. Most important, care coordinators help providers focus their time and energy where it can have the most impact.

The biggest disappointment

Shortly after RGVHA began reviewing patient claims data, home health care costs per patient emerged as one of the greatest cost outliers. The data revealed that providers outside of the ACO were prescribing home health at much higher rates than providers within the ACO. A subsequent gap analysis showed that home health was a prime opportunity target for RGVHA.

As RGVHA developed a strategy to address the overutilization and extremely high home health costs for their patient population, the providers faced their biggest disappointment to date: The Medicare Shared Savings Program regulations only permit ACOs to "ask" that providers outside the ACO coordinate patient care with doctors inside the ACO, not "tell" the providers that they must collaborate in delivering evidence-based, high-value care.

So, RGVHA decided to use those data as the starting point to reach out to those providers.

Dr. Hoyle helped RGVHA identify the amount of home health care generated by each specific agency and ordering physician. That information was used to craft a targeted letter to each provider outside the ACO requesting and encouraging their collaboration and cooperation in the development of a care plan for each home health patient.

Now, several months later, home health care overutilization and costs are beginning to decline, as patient care is monitored by RGVHA and appropriately coordinated among each ACO patient’s team of care providers.

RGVHA’s biggest concern has now become one of its biggest assets. The ACO doctors finally feel empowered in their ability to impact the quality and costs of patient care. Furthermore, they are excited they are getting paid for doing what they are trained to do: provide high-value care to their patients.

The good news is that, when properly informed and invited to help shape high-value patient care, providers want to and will do the right thing.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. Mr. Bobbitt is grateful for the excellent lead research and drafting of this article by Ms. Poe. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or at 919-821-6612.

In our last column, we highlighted the Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance, an accountable care organization in McAllen, Tex., composed of 14 independent primary care physicians in 11 practices. As primary care physicians, the RGVHA providers realized the potential for a primary care ACO to generate savings from value-based care.

Because RGVHA is a network model ACO – the physicians stay in their separate independent practices but participate in the ACO through contracts – RGVHA needed a way to manage the ACO data collection, sorting, and reporting requirements in an efficient and effective manner.

Fortunately, Dr. Gretchen Hoyle of MD Online Solutions was able to tailor a data management solution for RGVHA. In addition, Dr. Hoyle helps interpret the data and leads a weekly data-driven staff conference call with the ACO’s nurse care coordinators.

Through Dr. Hoyle’s data collection and interpretation work with RGVHA, the ACO now has concrete data showing utilization trends and patterns. The most positive result has been the demonstrated benefit of nurse care coordinators, who work with patients in the post–acute care settings between their office visits.

In fact, care coordinators have proved to be RGVHA’s secret weapon, because their work has been invaluable in managing patients with chronic conditions between provider appointments.

Conversely, the data have revealed a pattern of overuse of home health care services, which helps contribute to higher care costs overall, making home health the biggest disappointment.

The secret weapon

As Dr. Hoyle so aptly said, "To become a fully functioning ACO, an organization must be able to address both sides of the ACO ‘coin’: quality improvement and cost control." Care coordinators have the capacity to address both concerns.

Within RGVHA, care coordinators have performed chart reviews that identify the ACO’s current performance according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ quality standards. This is the first secret weapon for a small primary care ACO.

This data collection helps RGVHA fill in knowledge gaps as it works toward having a fully integrated electronic health records system. In turn, it helps the care coordinators identify the strengths and weaknesses of each of the participating ACO providers. This ensures that weaknesses can be addressed in a timely fashion. In addition, the chart reviews help identify documentation issues. Documentation is critical to meeting CMS benchmarks, which ultimately helps determine the amount of shared savings for an ACO.

In addition, the data have proved crucial to being able to rank patients by cost. That has allowed RGVHA to identify the top 10% of patients whose care accounts for 50% of the total care costs in the ACO. This information allows providers to understand which patients and types of patients are more expensive, and who can benefit most from intense care coordination and/or longer visits with RGVHA’s primary care doctors.

Claims data show that even a small amount of additional time and care coordination outside of the clinic setting curbs utilization for the most complex patients and saves money. Most important, care coordinators help providers focus their time and energy where it can have the most impact.

The biggest disappointment

Shortly after RGVHA began reviewing patient claims data, home health care costs per patient emerged as one of the greatest cost outliers. The data revealed that providers outside of the ACO were prescribing home health at much higher rates than providers within the ACO. A subsequent gap analysis showed that home health was a prime opportunity target for RGVHA.

As RGVHA developed a strategy to address the overutilization and extremely high home health costs for their patient population, the providers faced their biggest disappointment to date: The Medicare Shared Savings Program regulations only permit ACOs to "ask" that providers outside the ACO coordinate patient care with doctors inside the ACO, not "tell" the providers that they must collaborate in delivering evidence-based, high-value care.

So, RGVHA decided to use those data as the starting point to reach out to those providers.

Dr. Hoyle helped RGVHA identify the amount of home health care generated by each specific agency and ordering physician. That information was used to craft a targeted letter to each provider outside the ACO requesting and encouraging their collaboration and cooperation in the development of a care plan for each home health patient.

Now, several months later, home health care overutilization and costs are beginning to decline, as patient care is monitored by RGVHA and appropriately coordinated among each ACO patient’s team of care providers.

RGVHA’s biggest concern has now become one of its biggest assets. The ACO doctors finally feel empowered in their ability to impact the quality and costs of patient care. Furthermore, they are excited they are getting paid for doing what they are trained to do: provide high-value care to their patients.

The good news is that, when properly informed and invited to help shape high-value patient care, providers want to and will do the right thing.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the health law group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. Mr. Bobbitt is grateful for the excellent lead research and drafting of this article by Ms. Poe. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or at 919-821-6612.

ACO Insider: Anatomy of an independent primary care ACO, part 1

While concepts and theories can go a long way, sometimes the best way to understand something is through a concrete example.

So, from time to time, ACO Insider will check in on a new accountable care organization composed of 14 independent physicians in 11 practices in McAllen, Tex.

We chose them because they share many of the same questions and concerns as quite a few of you readers: Will this work? Where do I begin? How can we do this, since we have no free time or money? How much will this cost? Will there be any shared savings? Do we have to affiliate with a hospital or a large practice? Are we too small? How do we apply for the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP)? What will change in my practice?

The name of the ACO is Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance (RGVHA). It was formed in January 2012 as a "network-model" ACO, meaning that the physicians stay in their separate independent practices but participate in the ACO through contract. Its first – and as of this writing, only – ACO payer contract is with Medicare, the MSSP.

So far, there have been a number of unexpected highs and a number of unexpected lows. The primary care physicians of RGVHA hope that by sharing their story, they can help you better navigate your own ACO course.

Opportunity for primary care

Dr. Luis Delgado became intrigued by the possibility under accountable care of rewarding primary care physicians for the savings they generate while maintaining or improving quality. Instead of resisting change, he saw opportunity.

He also saw a chance to do something about McAllen’s reputation, gained through Dr. Atul Gawande’s 2009 article in the New Yorker entitled, "The Cost Conundrum." That article focused on McAllen’s Medicare health costs, which were almost twice those of its Rio Grande River neighbor, El Paso.

However, beyond having a vision, he had no know-how and no budget.

Fortunately, as readers of this column know, there is so much documented "low-hanging fruit" for primary care to generate savings through value-based care that the strategic time and expertise expenditures proved not to be significant. The legal structure and backroom business logistics for a small network-model primary care physician ACO are also relatively straightforward. RGVHA has two full-time administrative staffers, one part-time president (Dr. Delgado), and one part-time medical director (Dr. Roger Heredia).

However, the new ACO data collection, sorting, and reporting requirements were somewhat daunting – that is, until they met Dr. Gretchen Hoyle of MD Online Solutions (MDOS). Dr. Hoyle is a practicing pediatrician who spearheaded the design of a physician-friendly care management data system for her practice and found it ideal for the accountable care era. Her company targets small- to medium-sized physician-led ACOs.

MDOS was able to tailor a nimble ACO solution scaled to RGVHA’s needs, thus allowing RGVHA to supply its last missing piece in a cost-effective manner. Because she is a practicing physician, Dr. Hoyle helps interpret the data and leads a weekly data-driven staff conference call with the ACO’s nurse care coordinators.

Approved for the Medicare ACO

Despite initial fears, RGVHA found that the MSSP application process was not intimidating at all. It turned out to be a reflection of its business structure and primary care physician ACO strategy.

"If you get your game plan together ahead of time, independent primary care physicians should be successful in applying for the Medicare Shared Savings Program," stated Dr. Delgado. "We found that Medicare is supportive of this type of ACO, I guess because it sees their potential to improve health care," he said.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services does indeed support these types of ACOs, as RGVHA qualified for one of the last Advanced Payment Program grants. The CMS is so confident that these physician-led, nonmetropolitan ACOs will work, that the agency actually fronted the infrastructure and operational money to them. RGVHA was one of the last grantees of this one-time appropriation.

They began the MSSP program Jan. 1, 2013, opting not to take risk and to receive 50% of the savings they generated for the 5,000 patients attributed to them, if quality and patient satisfaction metrics are met.

‘I haven’t had this much fun practicing medicine in 10 years!’

To decide what type of initiatives to undertake, the physicians read the Physician’s Accountable Care Toolkit (profiled in an earlier column) and convened a weekend workshop. They were pleasantly surprised when they realized that so many savings and quality improvement opportunities are available to primary care physicians under accountable care – and control over the physician-patient relationship was being returned to them.

They targeted diabetes management, patient engagement, best practices for enhanced prevention and wellness, and home health management.

One physician summed up the mood when she exclaimed, "I haven’t had this much fun practicing medicine in 10 years."

As they celebrate their first year under the MSSP, how are they doing? Check in next month for part 2: Our secret weapon, and our biggest disappointment.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians in forming integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or at 919-821-6612.

While concepts and theories can go a long way, sometimes the best way to understand something is through a concrete example.

So, from time to time, ACO Insider will check in on a new accountable care organization composed of 14 independent physicians in 11 practices in McAllen, Tex.

We chose them because they share many of the same questions and concerns as quite a few of you readers: Will this work? Where do I begin? How can we do this, since we have no free time or money? How much will this cost? Will there be any shared savings? Do we have to affiliate with a hospital or a large practice? Are we too small? How do we apply for the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP)? What will change in my practice?

The name of the ACO is Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance (RGVHA). It was formed in January 2012 as a "network-model" ACO, meaning that the physicians stay in their separate independent practices but participate in the ACO through contract. Its first – and as of this writing, only – ACO payer contract is with Medicare, the MSSP.

So far, there have been a number of unexpected highs and a number of unexpected lows. The primary care physicians of RGVHA hope that by sharing their story, they can help you better navigate your own ACO course.

Opportunity for primary care

Dr. Luis Delgado became intrigued by the possibility under accountable care of rewarding primary care physicians for the savings they generate while maintaining or improving quality. Instead of resisting change, he saw opportunity.

He also saw a chance to do something about McAllen’s reputation, gained through Dr. Atul Gawande’s 2009 article in the New Yorker entitled, "The Cost Conundrum." That article focused on McAllen’s Medicare health costs, which were almost twice those of its Rio Grande River neighbor, El Paso.

However, beyond having a vision, he had no know-how and no budget.

Fortunately, as readers of this column know, there is so much documented "low-hanging fruit" for primary care to generate savings through value-based care that the strategic time and expertise expenditures proved not to be significant. The legal structure and backroom business logistics for a small network-model primary care physician ACO are also relatively straightforward. RGVHA has two full-time administrative staffers, one part-time president (Dr. Delgado), and one part-time medical director (Dr. Roger Heredia).

However, the new ACO data collection, sorting, and reporting requirements were somewhat daunting – that is, until they met Dr. Gretchen Hoyle of MD Online Solutions (MDOS). Dr. Hoyle is a practicing pediatrician who spearheaded the design of a physician-friendly care management data system for her practice and found it ideal for the accountable care era. Her company targets small- to medium-sized physician-led ACOs.

MDOS was able to tailor a nimble ACO solution scaled to RGVHA’s needs, thus allowing RGVHA to supply its last missing piece in a cost-effective manner. Because she is a practicing physician, Dr. Hoyle helps interpret the data and leads a weekly data-driven staff conference call with the ACO’s nurse care coordinators.

Approved for the Medicare ACO

Despite initial fears, RGVHA found that the MSSP application process was not intimidating at all. It turned out to be a reflection of its business structure and primary care physician ACO strategy.

"If you get your game plan together ahead of time, independent primary care physicians should be successful in applying for the Medicare Shared Savings Program," stated Dr. Delgado. "We found that Medicare is supportive of this type of ACO, I guess because it sees their potential to improve health care," he said.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services does indeed support these types of ACOs, as RGVHA qualified for one of the last Advanced Payment Program grants. The CMS is so confident that these physician-led, nonmetropolitan ACOs will work, that the agency actually fronted the infrastructure and operational money to them. RGVHA was one of the last grantees of this one-time appropriation.

They began the MSSP program Jan. 1, 2013, opting not to take risk and to receive 50% of the savings they generated for the 5,000 patients attributed to them, if quality and patient satisfaction metrics are met.

‘I haven’t had this much fun practicing medicine in 10 years!’

To decide what type of initiatives to undertake, the physicians read the Physician’s Accountable Care Toolkit (profiled in an earlier column) and convened a weekend workshop. They were pleasantly surprised when they realized that so many savings and quality improvement opportunities are available to primary care physicians under accountable care – and control over the physician-patient relationship was being returned to them.

They targeted diabetes management, patient engagement, best practices for enhanced prevention and wellness, and home health management.

One physician summed up the mood when she exclaimed, "I haven’t had this much fun practicing medicine in 10 years."

As they celebrate their first year under the MSSP, how are they doing? Check in next month for part 2: Our secret weapon, and our biggest disappointment.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians in forming integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or at 919-821-6612.

While concepts and theories can go a long way, sometimes the best way to understand something is through a concrete example.

So, from time to time, ACO Insider will check in on a new accountable care organization composed of 14 independent physicians in 11 practices in McAllen, Tex.

We chose them because they share many of the same questions and concerns as quite a few of you readers: Will this work? Where do I begin? How can we do this, since we have no free time or money? How much will this cost? Will there be any shared savings? Do we have to affiliate with a hospital or a large practice? Are we too small? How do we apply for the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP)? What will change in my practice?

The name of the ACO is Rio Grande Valley Health Alliance (RGVHA). It was formed in January 2012 as a "network-model" ACO, meaning that the physicians stay in their separate independent practices but participate in the ACO through contract. Its first – and as of this writing, only – ACO payer contract is with Medicare, the MSSP.

So far, there have been a number of unexpected highs and a number of unexpected lows. The primary care physicians of RGVHA hope that by sharing their story, they can help you better navigate your own ACO course.

Opportunity for primary care

Dr. Luis Delgado became intrigued by the possibility under accountable care of rewarding primary care physicians for the savings they generate while maintaining or improving quality. Instead of resisting change, he saw opportunity.

He also saw a chance to do something about McAllen’s reputation, gained through Dr. Atul Gawande’s 2009 article in the New Yorker entitled, "The Cost Conundrum." That article focused on McAllen’s Medicare health costs, which were almost twice those of its Rio Grande River neighbor, El Paso.

However, beyond having a vision, he had no know-how and no budget.

Fortunately, as readers of this column know, there is so much documented "low-hanging fruit" for primary care to generate savings through value-based care that the strategic time and expertise expenditures proved not to be significant. The legal structure and backroom business logistics for a small network-model primary care physician ACO are also relatively straightforward. RGVHA has two full-time administrative staffers, one part-time president (Dr. Delgado), and one part-time medical director (Dr. Roger Heredia).

However, the new ACO data collection, sorting, and reporting requirements were somewhat daunting – that is, until they met Dr. Gretchen Hoyle of MD Online Solutions (MDOS). Dr. Hoyle is a practicing pediatrician who spearheaded the design of a physician-friendly care management data system for her practice and found it ideal for the accountable care era. Her company targets small- to medium-sized physician-led ACOs.

MDOS was able to tailor a nimble ACO solution scaled to RGVHA’s needs, thus allowing RGVHA to supply its last missing piece in a cost-effective manner. Because she is a practicing physician, Dr. Hoyle helps interpret the data and leads a weekly data-driven staff conference call with the ACO’s nurse care coordinators.

Approved for the Medicare ACO

Despite initial fears, RGVHA found that the MSSP application process was not intimidating at all. It turned out to be a reflection of its business structure and primary care physician ACO strategy.

"If you get your game plan together ahead of time, independent primary care physicians should be successful in applying for the Medicare Shared Savings Program," stated Dr. Delgado. "We found that Medicare is supportive of this type of ACO, I guess because it sees their potential to improve health care," he said.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services does indeed support these types of ACOs, as RGVHA qualified for one of the last Advanced Payment Program grants. The CMS is so confident that these physician-led, nonmetropolitan ACOs will work, that the agency actually fronted the infrastructure and operational money to them. RGVHA was one of the last grantees of this one-time appropriation.

They began the MSSP program Jan. 1, 2013, opting not to take risk and to receive 50% of the savings they generated for the 5,000 patients attributed to them, if quality and patient satisfaction metrics are met.

‘I haven’t had this much fun practicing medicine in 10 years!’

To decide what type of initiatives to undertake, the physicians read the Physician’s Accountable Care Toolkit (profiled in an earlier column) and convened a weekend workshop. They were pleasantly surprised when they realized that so many savings and quality improvement opportunities are available to primary care physicians under accountable care – and control over the physician-patient relationship was being returned to them.

They targeted diabetes management, patient engagement, best practices for enhanced prevention and wellness, and home health management.

One physician summed up the mood when she exclaimed, "I haven’t had this much fun practicing medicine in 10 years."

As they celebrate their first year under the MSSP, how are they doing? Check in next month for part 2: Our secret weapon, and our biggest disappointment.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians in forming integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author at bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or at 919-821-6612.

Distribution based on contribution: The merit-based ACO shared savings distribution model

Our nation is in the midst of an inexorable shift in health care delivery from "pay for volume" to "pay for value." It is well documented that our current largely fee-for-service system is unsustainable and a dramatic incentive shift must occur. Every provider needs to be committed to providing the highest quality at the lowest cost. This is the fundamental goal of the pay-for-value system.

If quality and patient satisfaction criteria are met and providers working together in an accountable care organization or similar entity create savings for a defined patient population, then the ACO usually gets a portion of the savings, commonly 50%. Unlike capitated arrangements, shared savings arrangements can avoid or limit downside financial risk and therefore can serve as stepping-stones toward fuller accountability and incentives. They are quite appropriate for start-up and smaller ACOs.

The ACO gets the savings, if there are any. But what the ACO does with them is crucial to the success and sustainability of the organization. "ACOs must offer a realistic and achievable opportunity for providers to share in the savings created from delivering higher-value care. The incentive system must reward providers for delivering efficient care as opposed to the current volume-driven system" (The ACO Toolkit; the Dartmouth Institute, p. 9, Jan. 2011).

If providers or hospital stakeholders feel that their efforts to drive value are not being fairly recognized, they will no longer participate meaningfully, the goals of value-based medicine will be thwarted, and savings will not occur in the long-run. Before signing a participation contract, physicians should scrutinize how each ACO plans to distribute the savings it receives.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services administers the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP). The fact that CMS’s regulations concerning MSSP are not prescriptive about a given savings distribution formula gives ACOs flexibility in this area. But the regulations are specific about the ultimate purpose of distributions: "As part of its application, an ACO must describe the following: (1) how it plans to use shared savings payments, including the criteria it plans to employ for distributing shared savings among its ACO participants and ACO providers/suppliers, ... and (3) how the proposed plan will achieve the general aims of better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower growth in expenditures" (42 CFR 425.204(d), 76 Fed. Reg. 6798 [Nov. 2, 2011]).

Fatal flaw?

Some ACOs, however, have lost sight of the fact that failure to have a fair shared savings distribution formula (linking relative distributions to relative contributions) will be fatal to its sustainability. Some view them as "profits" to go to the owners or shareholders. Some simply lock in a fixed allocation similar to fee-for-service payment ratios, without regard to who generated the savings. Some employers of physicians have contracted to compensate only on a work production basis with zero performance incentive payments at all. Other ACOs are putting off the issue because it is sensitive culturally. As health care moves more and more to value-based compensation, the distribution of savings must be viewed primarily as the providers’ professional remuneration and not corporate "profit." Payments for administrative services and debt service must, of course, come out of the savings distribution to "keep the pump primed," but they should be carefully managed. The bulk must be distributed in proportion to contribution toward quality and cost-effective care.

One physician stated, "No physician is going to join an ACO when someone else is telling them what they are worth unless they know that the savings distribution formula is impeccably fair." To those putting off design of a fair merit-based compensation system until there is more physician buy-in, we respectfully submit that you cannot get buy-in without one.

A need for honed metrics

Yes, this concept is pretty basic when you think about it. But though it may be easy to understand, it can be complex to implement, especially when multiple specialists and facilities are involved in an ACO’s care coordination. One not only needs to determine the relative potential and actual value contribution for each provider, but also the clinically valid metrics by which to measure them. Under fee for service, metrics for success were usually transactional and objective (in other words, volume of procedure times rate). An ACO’s success metrics may be neither. Success may come from things not happening (that is, fewer ED visits, avoidable admissions, and reduced readmissions). At the same time, the distribution model needs to be clear, practical, and capable of being understood by all.

But there can be a replicable framework for any ACO to use to create a fair and sustainable shared savings distribution model. There are necessary subjective judgments – at this time, many metrics are imprecise or nonexistent – and the sophistication of the distribution process must parallel the sophistication of the ACO’s infrastructure. But, if the right people are involved and apply the ACO’s guiding principles on savings allocation, participants will be appropriately incentivized. The precision of distribution application will grow over time. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

The six guiding principles for shared savings distribution

Though application will vary widely because of differing circumstances and types of initiatives, chances for success will increase if every activity can be judged by whether it is consistent with a set of guiding principles viewed as fair by the ACO members. You may want to consider a savings distribution formula with the following principles:

• Eyes on the prize: Triple Aim. It offers incentives for the delivery of high-quality and cost-effective care to achieve the Triple Aim – better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower per capita costs.

• Broad provider input. It is the result of input from a diverse spectrum of knowledgeable providers who understand what drives patient population value.

• Fairness. It is fair to all in that it links relative distribution to relative contribution to the organization’s total savings and quality performance, and adheres to measurable clinically valid metrics.

• Transparency. It is clear, transparent, practical to implement and replicable.

• Constant evolution. It adapts and improves as the capabilities and experience as the ACO grows.

• Maximized incentive to drive value by all participants. After prudently meeting overhead costs, it allows gradual transition as well as commercially reasonable return on capital investment or debt service. It makes the most of ongoing incentive programs for all to deliver value by distributing as much of the savings surplus as possible to those who generate them.

Weighting: How to assign relative percentage among providers

As mentioned, it is important that design of a fair distribution formula be the product of collaboration among informed and committed clinicians who understand patient population management. Like virtually all organization compensation formulas, the determination of relative contributions of the different providers in a given ACO, or care initiative within the ACO, will involve a certain amount of inherent subjectivity but will be guided by weighted criteria applied in good faith.

• Step 1: Break down each initiative into its value-adding elements and assign provider responsibility for each. The ACO will have a number of different care management initiatives. Some, like outpatient diabetes management, may be completely the responsibility of one provider specialty, (that is, primary care). Others may involve coordination across multiple settings for patients with multiple conditions involving multiple specialties. Each initiative was chosen for a reason – to drive value. In setting relative potential distribution percentages, envision the perfect implementation of each initiative. Next, look at what tasks or best practices are needed to drive success, and then who is assigned responsibility for each.

• Step 2: Assign relative percentages to each specialty relative to its potential to realize savings. For a pure primary care prevention initiative, they would get 100% in all categories. For multispecialty initiatives, the percentage is tied to the proportion of those savings predicted to flow from that provider class.

N.B.: Historically, cost centers are not necessarily the cost savers. A mature ACO will be able to allocate savings to each initiative and the relative savings distribution within each. But for a start-up ACO, because it is so apparently logical and fits the traditional fee-for-service mindset, it is tempting to look at claims differences in the various service categories, such as inpatient, outpatient, primary care, specialists, drugs, and ancillaries, and attribute savings to the provider historically billing for same (that is, hospitals get "credit" for reduced hospital costs). However, a successful wellness, prevention, or lifestyle counseling program in a medical home may be the reason those patients never go to the hospital. The radiologist embedded in the medical home diagnostic team may have helped make an informed image analysis confirming a negative result and avoided those admissions. But, do use those service categories to set cost targets.

• Step 3: Individual attribution. We now know every provider group’s potential savings, but how do we determine the actual distribution based on actual results? Select metrics that are accurately associated with the desired individual and collective conduct of that provider class. They should cover both quality and efficiency. In the value-based reimbursement world, even if the performance is superb, if it is not measured appropriately, it will not be rewarded.

Once the proper metrics are selected, each provider’s performance is measured.

Keep it simple and open

Pick a few of the very best quality and efficiency metrics and have them and the data collection process thoroughly vetted by the providers. Following the guiding principles, the distribution model will be a success if: (1) everyone understands that this is the best practical approach, (2) the process has been open, and (3) everyone is acting in good faith to have as fair a shared savings distribution process as the current sophistication level of the ACO’s infrastructure allows. It cannot be viewed as coming from a "black box." For a young ACO, it will be crude, at best, in the beginning.

Conclusion

Even at this dawning of the movement to value-based reimbursement in health care, a framework for a fair merit-based shared savings distribution is available to all ACOs. As ACOs gain actual performance data, their health information technology capabilities improve, and refined quality and efficiency metrics emerge, the process will evolve from an open and good-faith application of the guiding principles with limited tools, to more and more refined determinations of the sources of the ACO’s quality and savings results. The path will get easier over time, but the destination is always clear – distribution in proportion to contribution.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author (bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612).

Our nation is in the midst of an inexorable shift in health care delivery from "pay for volume" to "pay for value." It is well documented that our current largely fee-for-service system is unsustainable and a dramatic incentive shift must occur. Every provider needs to be committed to providing the highest quality at the lowest cost. This is the fundamental goal of the pay-for-value system.

If quality and patient satisfaction criteria are met and providers working together in an accountable care organization or similar entity create savings for a defined patient population, then the ACO usually gets a portion of the savings, commonly 50%. Unlike capitated arrangements, shared savings arrangements can avoid or limit downside financial risk and therefore can serve as stepping-stones toward fuller accountability and incentives. They are quite appropriate for start-up and smaller ACOs.

The ACO gets the savings, if there are any. But what the ACO does with them is crucial to the success and sustainability of the organization. "ACOs must offer a realistic and achievable opportunity for providers to share in the savings created from delivering higher-value care. The incentive system must reward providers for delivering efficient care as opposed to the current volume-driven system" (The ACO Toolkit; the Dartmouth Institute, p. 9, Jan. 2011).

If providers or hospital stakeholders feel that their efforts to drive value are not being fairly recognized, they will no longer participate meaningfully, the goals of value-based medicine will be thwarted, and savings will not occur in the long-run. Before signing a participation contract, physicians should scrutinize how each ACO plans to distribute the savings it receives.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services administers the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP). The fact that CMS’s regulations concerning MSSP are not prescriptive about a given savings distribution formula gives ACOs flexibility in this area. But the regulations are specific about the ultimate purpose of distributions: "As part of its application, an ACO must describe the following: (1) how it plans to use shared savings payments, including the criteria it plans to employ for distributing shared savings among its ACO participants and ACO providers/suppliers, ... and (3) how the proposed plan will achieve the general aims of better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower growth in expenditures" (42 CFR 425.204(d), 76 Fed. Reg. 6798 [Nov. 2, 2011]).

Fatal flaw?

Some ACOs, however, have lost sight of the fact that failure to have a fair shared savings distribution formula (linking relative distributions to relative contributions) will be fatal to its sustainability. Some view them as "profits" to go to the owners or shareholders. Some simply lock in a fixed allocation similar to fee-for-service payment ratios, without regard to who generated the savings. Some employers of physicians have contracted to compensate only on a work production basis with zero performance incentive payments at all. Other ACOs are putting off the issue because it is sensitive culturally. As health care moves more and more to value-based compensation, the distribution of savings must be viewed primarily as the providers’ professional remuneration and not corporate "profit." Payments for administrative services and debt service must, of course, come out of the savings distribution to "keep the pump primed," but they should be carefully managed. The bulk must be distributed in proportion to contribution toward quality and cost-effective care.

One physician stated, "No physician is going to join an ACO when someone else is telling them what they are worth unless they know that the savings distribution formula is impeccably fair." To those putting off design of a fair merit-based compensation system until there is more physician buy-in, we respectfully submit that you cannot get buy-in without one.

A need for honed metrics

Yes, this concept is pretty basic when you think about it. But though it may be easy to understand, it can be complex to implement, especially when multiple specialists and facilities are involved in an ACO’s care coordination. One not only needs to determine the relative potential and actual value contribution for each provider, but also the clinically valid metrics by which to measure them. Under fee for service, metrics for success were usually transactional and objective (in other words, volume of procedure times rate). An ACO’s success metrics may be neither. Success may come from things not happening (that is, fewer ED visits, avoidable admissions, and reduced readmissions). At the same time, the distribution model needs to be clear, practical, and capable of being understood by all.

But there can be a replicable framework for any ACO to use to create a fair and sustainable shared savings distribution model. There are necessary subjective judgments – at this time, many metrics are imprecise or nonexistent – and the sophistication of the distribution process must parallel the sophistication of the ACO’s infrastructure. But, if the right people are involved and apply the ACO’s guiding principles on savings allocation, participants will be appropriately incentivized. The precision of distribution application will grow over time. Don’t let the perfect be the enemy of the good.

The six guiding principles for shared savings distribution

Though application will vary widely because of differing circumstances and types of initiatives, chances for success will increase if every activity can be judged by whether it is consistent with a set of guiding principles viewed as fair by the ACO members. You may want to consider a savings distribution formula with the following principles:

• Eyes on the prize: Triple Aim. It offers incentives for the delivery of high-quality and cost-effective care to achieve the Triple Aim – better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower per capita costs.

• Broad provider input. It is the result of input from a diverse spectrum of knowledgeable providers who understand what drives patient population value.

• Fairness. It is fair to all in that it links relative distribution to relative contribution to the organization’s total savings and quality performance, and adheres to measurable clinically valid metrics.

• Transparency. It is clear, transparent, practical to implement and replicable.

• Constant evolution. It adapts and improves as the capabilities and experience as the ACO grows.

• Maximized incentive to drive value by all participants. After prudently meeting overhead costs, it allows gradual transition as well as commercially reasonable return on capital investment or debt service. It makes the most of ongoing incentive programs for all to deliver value by distributing as much of the savings surplus as possible to those who generate them.

Weighting: How to assign relative percentage among providers

As mentioned, it is important that design of a fair distribution formula be the product of collaboration among informed and committed clinicians who understand patient population management. Like virtually all organization compensation formulas, the determination of relative contributions of the different providers in a given ACO, or care initiative within the ACO, will involve a certain amount of inherent subjectivity but will be guided by weighted criteria applied in good faith.

• Step 1: Break down each initiative into its value-adding elements and assign provider responsibility for each. The ACO will have a number of different care management initiatives. Some, like outpatient diabetes management, may be completely the responsibility of one provider specialty, (that is, primary care). Others may involve coordination across multiple settings for patients with multiple conditions involving multiple specialties. Each initiative was chosen for a reason – to drive value. In setting relative potential distribution percentages, envision the perfect implementation of each initiative. Next, look at what tasks or best practices are needed to drive success, and then who is assigned responsibility for each.

• Step 2: Assign relative percentages to each specialty relative to its potential to realize savings. For a pure primary care prevention initiative, they would get 100% in all categories. For multispecialty initiatives, the percentage is tied to the proportion of those savings predicted to flow from that provider class.

N.B.: Historically, cost centers are not necessarily the cost savers. A mature ACO will be able to allocate savings to each initiative and the relative savings distribution within each. But for a start-up ACO, because it is so apparently logical and fits the traditional fee-for-service mindset, it is tempting to look at claims differences in the various service categories, such as inpatient, outpatient, primary care, specialists, drugs, and ancillaries, and attribute savings to the provider historically billing for same (that is, hospitals get "credit" for reduced hospital costs). However, a successful wellness, prevention, or lifestyle counseling program in a medical home may be the reason those patients never go to the hospital. The radiologist embedded in the medical home diagnostic team may have helped make an informed image analysis confirming a negative result and avoided those admissions. But, do use those service categories to set cost targets.

• Step 3: Individual attribution. We now know every provider group’s potential savings, but how do we determine the actual distribution based on actual results? Select metrics that are accurately associated with the desired individual and collective conduct of that provider class. They should cover both quality and efficiency. In the value-based reimbursement world, even if the performance is superb, if it is not measured appropriately, it will not be rewarded.

Once the proper metrics are selected, each provider’s performance is measured.

Keep it simple and open

Pick a few of the very best quality and efficiency metrics and have them and the data collection process thoroughly vetted by the providers. Following the guiding principles, the distribution model will be a success if: (1) everyone understands that this is the best practical approach, (2) the process has been open, and (3) everyone is acting in good faith to have as fair a shared savings distribution process as the current sophistication level of the ACO’s infrastructure allows. It cannot be viewed as coming from a "black box." For a young ACO, it will be crude, at best, in the beginning.

Conclusion

Even at this dawning of the movement to value-based reimbursement in health care, a framework for a fair merit-based shared savings distribution is available to all ACOs. As ACOs gain actual performance data, their health information technology capabilities improve, and refined quality and efficiency metrics emerge, the process will evolve from an open and good-faith application of the guiding principles with limited tools, to more and more refined determinations of the sources of the ACO’s quality and savings results. The path will get easier over time, but the destination is always clear – distribution in proportion to contribution.

Mr. Bobbitt is a senior partner and head of the Health Law Group at the Smith Anderson law firm in Raleigh, N.C. He has many years’ experience assisting physicians form integrated delivery systems. He has spoken and written nationally to primary care physicians on the strategies and practicalities of forming or joining ACOs. This article is meant to be educational and does not constitute legal advice. For additional information, readers may contact the author (bbobbitt@smithlaw.com or 919-821-6612).

Our nation is in the midst of an inexorable shift in health care delivery from "pay for volume" to "pay for value." It is well documented that our current largely fee-for-service system is unsustainable and a dramatic incentive shift must occur. Every provider needs to be committed to providing the highest quality at the lowest cost. This is the fundamental goal of the pay-for-value system.

If quality and patient satisfaction criteria are met and providers working together in an accountable care organization or similar entity create savings for a defined patient population, then the ACO usually gets a portion of the savings, commonly 50%. Unlike capitated arrangements, shared savings arrangements can avoid or limit downside financial risk and therefore can serve as stepping-stones toward fuller accountability and incentives. They are quite appropriate for start-up and smaller ACOs.

The ACO gets the savings, if there are any. But what the ACO does with them is crucial to the success and sustainability of the organization. "ACOs must offer a realistic and achievable opportunity for providers to share in the savings created from delivering higher-value care. The incentive system must reward providers for delivering efficient care as opposed to the current volume-driven system" (The ACO Toolkit; the Dartmouth Institute, p. 9, Jan. 2011).

If providers or hospital stakeholders feel that their efforts to drive value are not being fairly recognized, they will no longer participate meaningfully, the goals of value-based medicine will be thwarted, and savings will not occur in the long-run. Before signing a participation contract, physicians should scrutinize how each ACO plans to distribute the savings it receives.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services administers the Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP). The fact that CMS’s regulations concerning MSSP are not prescriptive about a given savings distribution formula gives ACOs flexibility in this area. But the regulations are specific about the ultimate purpose of distributions: "As part of its application, an ACO must describe the following: (1) how it plans to use shared savings payments, including the criteria it plans to employ for distributing shared savings among its ACO participants and ACO providers/suppliers, ... and (3) how the proposed plan will achieve the general aims of better care for individuals, better health for populations, and lower growth in expenditures" (42 CFR 425.204(d), 76 Fed. Reg. 6798 [Nov. 2, 2011]).

Fatal flaw?