User login

Amputation Care Quality and Satisfaction With Prosthetic Limb Services: A Longitudinal Study of Veterans With Upper Limb Amputation

Veterans with upper limb amputation (ULA) are a small, but important population, who have received more attention in the past decade due to the increased growth of the population of veterans with conflict-related amputation from recent military engagements. Among the 808 veterans with ULA receiving any care in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from 2010 to 2015 who participated in our national study, an estimated 28 to 35% had a conflict-related amputation.1 The care of these individuals with ULA is highly specialized, and there is a recognized shortage of experienced professionals in this area.2,3 The provision of high-quality prosthetic care is increasingly complex with advances in technology, such as externally powered devices with multiple functions.

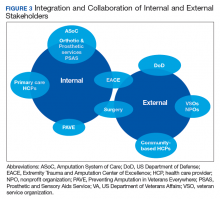

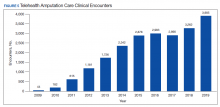

The VA is a comprehensive, integrated health care system that serves more than 8.9 million veterans each year. Interdisciplinary amputation care is provided within the VA through a traditional clinic setting or by using one of several currently available virtual care modalities.4,5 In consultation with the veteran, VA health care providers (HCPs) prescribe prostheses and services based on the clinical needs and furnish authorized items and services to eligible veterans. Prescribed items and/or services are furnished either by internal VA resources or through a community-based prosthetist who is an authorized vendor or contractor. Although several studies have reported that the majority of veterans with ULA utilize VA services for at least some aspects of their health care, little is known about: (1) prosthetic limb care satisfaction or the quality of care that veterans receive; or (2) how care within the VA or Department of Defense (DoD) compares with care provided in the civilian sector.6-8

Earlier studies that examined the amputation rehabilitation services received by veterans with ULA pointed to quality gaps in care and differences in satisfaction in the VA and DoD when compared with the civilian sector but were limited in their scope and methodology.7,8 A 2008 study of veterans of the Vietnam War, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) compared satisfaction by location of care receipt (DoD only, VA only, private only, and multiple sources). That study dichotomized response categories for items related to satisfaction with care (satisfied/not), but did not estimate degree of satisfaction, calculate summary scores of the items, or utilize validated care satisfaction metrics. That study found that a greater proportion of Vietnam War veterans (compared with OIF/OEF veterans receiving care in the private sector) agreed that they “had a role in choosing prosthesis” and disagreed that they wanted to change their current prosthesis to another type.7 The assumption made by the authors is that much of this private sector care was actually VA-sponsored care prescribed and procured by the VA but delivered in the community. However, no data were collected to confirm or refute this assumption, and it is possible that some care was both VA sponsored and delivered, some was VA sponsored but commercially delivered, and in some cases, care was sponsored by other sources and delivered in still other facilities.

A 2012 VA Office of the Inspector General study of OIF, OEF, and Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans reported lower prosthetic satisfaction for veterans with upper limb when compared with lower limb amputation and described respondents concerns about lack of VA prosthetic expertise, difficulty with accessing VA services, and dissatisfaction with the sometimes lengthy approval process for obtaining fee-basis or VA contract care.8 Although this report suggested that there were quality gaps and areas for improvement, it did not employ validated metrics of prosthesis or care satisfaction and instead relied on qualitative data collected through telephone interviews.

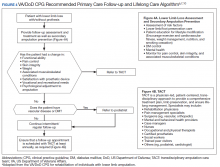

Given the VA effort to enhance the quality and consistency of its amputation care services through the formal establishment of the Amputation System of Care, which began in 2008, further evaluation of care satisfaction and quality of care is warranted. In 2014 the VA and DoD released the first evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the rehabilitation of persons with ULA.2 The CPG describes care paths to improve outcomes and basic tenets of amputation rehabilitation care and can be used to identify process activities that are essential aspects of quality care. However, the extent to which the CPG has impacted the quality and timeliness of care for veterans with ULA are presently unclear.

Thus, the purposes of this study were to: (1) measure veteran satisfaction with prosthetic limb care and identify factors associated with service satisfaction; (2) assess quality indicators that potentially reflect CPG) adoption; (3) compare care satisfaction and quality for those who received care in or outside of the VA or DoD; and (4) evaluate change in satisfaction over time.

Methods

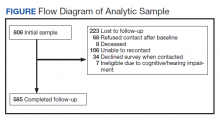

The study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Study #16-20) and Human Research Protection Office, U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command. The sampling frame consisted of veterans with major ULA who received care in the VA between 2010 and 2015 identified in VA Corporate Data Warehouse. We sent recruitment packages to nondeceased veterans who had current addresses and phone numbers. Those who did not opt out or inform us that they did not meet eligibility criteria were contacted by study interviewers. A waiver of documentation of written informed consent was obtained from the VA Central IRB. When reached by the study interviewer, Veterans provided oral informed consent. At baseline, 808 veterans were interviewed for a response rate of 47.7% as calculated by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) methodology.9 Follow-up interviews approximately 1 year later (mean [SD] 367 [16.8] days), were conducted with 585 respondents for a 72.4% response rate (Figure).

Survey Content

Development and pilot testing of the survey instrument previously was reported.1 The content of the survey drew from existing survey items and metrics, and included new items specifically designed to address patterns of amputation care, based on care goals within the CPG. All new and modified items were tested and refined through cognitive interviews with 10 participants, and tested with an additional 13 participants.

The survey collected data on demographics, amputation characteristics (year of amputation, level, laterality, and etiology), current prosthesis use, and type of prosthesis. This article focused on the sections of the survey pertaining to satisfaction with prosthetic care and indicators of quality of care. A description of the content of the full survey and a synopsis of overall findings are reported in a prior publication.1 The key independent, dependent, and other variables utilized in the analyses reported in this manuscript are described below.

Primary Independent Variables

In the follow-up survey, we asked respondents whether they had any amputation care in the prior 12 months, and if so to indicate where they had gone for care. We categorized respondents as having received VA/DoD care if they reported any care at the VA or DoD, and as having received non-VA/DoD care if they did not report care at the VA or DoD but indicated that they had received amputation care between baseline and follow-up.

Two primary outcomes were utilized; the Orthotics and Prosthetics User’s Survey (OPUS), client satisfaction with services scale (CSS), and a measure of care quality specifically developed for this study. The CSS is a measure developed specifically for orthotic and prosthesis users.10 This 11-item scale measures satisfaction with prosthetic limb services and contains items evaluating facets of care such as courtesy received from prosthetists and clinical staff, care coordination, appointment wait time, willingness of the prosthetist to listen to participant concerns, and satisfaction with prosthesis training. Items are rated on a 4-point scale (strongly agree [1] to strongly disagree [4]), thus higher CSS scores indicate worse satisfaction with services. The CSS was administered only to prosthesis users.

The Quality of Care assessment developed for this study contained items pertaining to amputation related care receipt and care quality. These items were generated by the study team in consultation with representatives from the VA/DoD Extremity Amputation Center of Excellence after review of the ULA rehabilitation CPG. Survey questions asked respondents about the clinicians visited for amputation related care in the past 12 months, whether they had an annual amputation-related checkup, whether any clinician had assessed their function, worked with them to identify goals, and/or to develop an amputation-related care plan. Respondents were also asked whether there had been family/caregiver involvement in their care and care coordination, whether a peer visitor was involved in their initial care, whether they had received information about amputation management in the prior year, and whether they had amputation-related pain. Those that indicated that they had amputation-related pain were subsequently asked whether their pain was well managed, whether they used medication for pain management, and whether they used any nonpharmaceutical strategies.

Quality of Care Index

We initially developed 15 indicator items of quality of care. We selected 7 of the items to create a summary index. We omitted 3 items about pain management, since these items were completed only by participants who indicated that they had experienced pain; however, we examined the 3 pain items individually given the importance of this topic. We omitted an additional 2 items from the summary index because they would not be sensitive to change because they pertained to the care in the year after initial amputation. One of these items asked whether caregivers were involved in initial amputation management and the other asked whether a peer visit occurred after amputation. Another 3 items were omitted because they only were completed by small subsamples due to intentional skip patterns in the survey. These items addressed whether clinical HCPs discussed amputation care goals in the prior year, worked to develop a care plan in the prior year, or helped to coordinate care after a move. Completion rates for all items considered for the index are shown in eAppendix 1 (Available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). After item selection, we generated an index score, which was the number of reported “yes” responses to the seven relevant items.

Other Variables

We created a single variable called level/laterality which categorized ULA as unilateral or bilateral. We further categorized respondents with unilateral amputation by their amputation level. We categorized respondents as transradial for wrist joint or below the elbow amputations; transhumeral for at or above the elbow amputations; and shoulder for shoulder joint or forequarter amputations. Participants indicated the amputation etiology using 7 yes/no variables: combat injury, accident, burn, cancer, diabetes mellitus, and infection. Participants could select ≥ 1 etiology.

Primary prosthesis type was categorized as body powered, myoelectric/hybrid, cosmetic, other/unknown, or nonuser. The service era was classified based on amputation date as Before Vietnam, Vietnam War, After Vietnam to Gulf War, After Gulf War to September 10, 2001, and September 11, 2001 to present. For race, individuals with > 1 race were classified as other. We classified participants by region, using the station identification of the most recent VA medical center that they had visited between January 1, 2010 and December 30, 2015.

The survey also employed 2 measures of satisfaction with the prosthesis, the Trinity Amputation and Prosthetic Experience Scale (TAPES) satisfaction scale and the OPUS Client Satisfaction with Devices (CSD). TAPES consists of 10 items addressing color, shape, noise, appearance, weight, usefulness, reliability, fit, comfort and overall satisfaction.11 Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (5). An 8-item version of the CSD scale was created for this study, after conducting a Rasch analysis (using Winsteps version 4.4.2) of the original 11-item CSD. The 8 items assess satisfaction with prosthesis fit, weight, comfort, donning ease, appearance, durability, skin contact, and pain. Items are rated on a 4-point scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4); higher CSD scores indicate less satisfaction with devices. Psychometric analysis of the revised CSD score was reported in a prior publication.12 We also reported on the CSS using the original 10-item measure.

Data Analyses

We described characteristics of respondents at baseline and follow-up. We used baseline data to calculate CSS scores and described scores for all participants, for subgroups of unilateral and bilateral amputees, and for unilateral amputees stratified by amputation level. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the CSS item and total scores of 461 prosthesis users with unilateral amputation and 29 with bilateral amputation. To identify factors that we hypothesized might be associated with CSS scores at baseline, we developed separate bivariate linear regression models. We added those factors that were associated with CSS scores at P ≤ .1 in bivariate analyses to a multivariable linear regression model of factors associated with CSS score. The P ≤ .1 threshold was used to ensure that relevant confounders were controlled for in regression models. We excluded 309 participants with no reported prosthesis use (who were not asked to complete the CSS), 20 participants with other/unknown prosthesis types, and 106 with missing data on amputation care in the prior year or on satisfaction metrics. We used baseline data for this analysis to maximize the sample size.

We compared CSS scores for those who reported receiving care within or outside of the VA or DoD in the prior year, using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney rank tests. We also compared scores of individual quality of care items for these groups using Fisher exact tests. We chose to examine individual items rather than the full Index because several items specified care receipt within the VA and thus would be inappropriate to utilize in comparisons by site location; however, we described responses to all items. In these analyses, we excluded 2 respondents who had conflicting information regarding location of care. We used follow-up data for this analysis because it allowed us to identify location of care received in the prior year.

We also described the CSS scores, the 7-item Quality of Care Index and responses to other items related to quality of care at baseline and follow-up. To examine whether satisfaction with prosthetic care or aspects of care quality had changed over time, we compared baseline and follow-up CSS and quality of care scores for respondents who had measures at both times using Wilcoxon signed ranks tests. Individual items were compared using McNemar tests.

Results

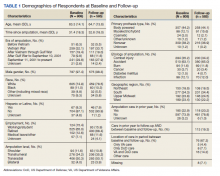

Respondents were 97.4% male and included 776 unilateral amputees and 32 bilateral amputees with a mean (SD) age of 63.3 (14.1) years (Table 1). Respondents had lost their limbs a mean (SD) 31.4 (14.1) years prior, and half were transradial, 34.2% transhumeral, and 11.6% shoulder amputation. At baseline 185 (22.9%) participants received amputation-related care in the prior year and 118 (20.2%) participants received amputation-related care within 1 year of follow-up. Of respondents, 113 (19.3%) stated that their care was between baseline and follow-up and 89 (78.8%) of these received care at either the VA, the DoD or both; just 16 (14.2%) received care elsewhere.

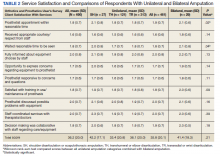

Mean (SD) CSS scores were highest (lower satisfaction) for those with amputation at the shoulder and lowest for those with transhumeral amputation: 42.2 (20.0) vs 33.4 (20.8). Persons with bilateral amputation were less satisfied in almost every category when compared with those with unilateral amputation, although the total CSS score was not substantially different. Wilcoxon rank sum analyses revealed statistically significant differences in wait time satisfaction: bilateral amputees were less satisfied than unilateral amputees. Factors associated with overall CSS score in bivariate analyses were CSD score, TAPES score, amputation care receipt, prosthesis type, race, and region of care (eAppendix 2, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096).

In the multivariate regression model of baseline CSS scores, only 2 variables were independently associated with CSS scores: CSD score and recent amputation care (Table 3). For each 1-point increase in CSD score there was a 0.7 point increase in CSS score. Those with amputation care in the prior year had higher satisfaction when compared with those who had not received care (P = .003).

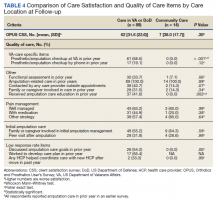

For participants who indicated that they received amputation care between baseline and follow-up, CSS mean (SD) scores were better, but not statistically different, for those who reported care in the VA or DoD vs private care, 31.6 (22.6) vs 38.0 (17.7) (Table 4). When compared with community-based care, more participants who received care in the VA or DoD in the prior year had a functional assessment in that time period (33.7% vs 7.1%, P = .06), were contacted by HCPs outside of appointments (42.7% vs 18.8%, P = .07), and received information about amputation care in the prior year (41.6% vs 0%, P =.002). There was no difference in the proportion whose family/caregivers were involved in care in the prior year.

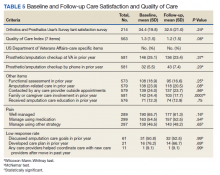

No statistically significant differences were observed in paired comparisons of the CSS and Quality of Care Index at baseline or follow-up for all participants with data at both time points (Table 5; eAppendix 3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). Individual pain measures did not differ significantly between timepoints. Quality Index mean (SD) scores were 1.3 (1.5) and 1.2 (1.5) at baseline and follow-up, respectively (P = .07). For the 214 prosthesis users with longitudinal data, baseline CSS mean (SD) scores were generally worse at baseline than at follow-up: 34.4 (19.8) vs 32.5 (21.0) (P = .23). Family/caregiver involvement in amputation care was significantly higher in the year before baseline when compared with the year prior to follow-up (24.4% vs 17.7%, P = .001). There were no other statistically significant differences in Quality of Care items between baseline and follow-up.

Discussion

Our longitudinal study provides insights into the experiences of veterans with major ULA related to satisfaction with prosthetic limb care services and receipt of amputation-related care. We reported on the development and use of a new summary measure of amputation care quality, which we designed to capture some of the key elements of care quality as provided in the VA/DoD CPG.2

We used baseline data to identify factors independently associated with prosthetic limb care satisfaction as measured by a previously validated measure, the OPUS CSS. The CSS addresses satisfaction with prosthetic limb services and does not reflect satisfaction with other amputation care services. We found that persons who received amputation care in the prior year had CSS scores that were a mean 5.1 points better than those who had not received recent care. Although causality cannot be determined with this investigation, this finding highlights an important relationship between frequency of care and satisfaction, which can be leveraged by the VA in future care initiatives. Care satisfaction was also better by 0.7 points for every 1-point decrease (indicating higher satisfaction) in the OPUS CSD prosthetic satisfaction scale. This finding isn’t surprising, given that a major purpose of prosthetic limb care services is to procure and fit a satisfactory device. To determine whether these same relationships were observed in the smaller, longitudinal cohort data at follow-up, we repeated these models and found similar relationships between recent care receipt and prosthesis satisfaction and satisfaction with services. We believe that these findings are meaningful and emphasize the importance of both service and device satisfaction to the veteran with an ULA. Lower service satisfaction scores among those with amputations at the shoulder and those with bilateral limb loss suggest that these individuals may benefit from different service delivery approaches.

We did observe a difference in satisfaction scores by geographic region in the follow-up (but not the baseline) data with satisfaction higher in the Western vs the Southern region (data not shown). This finding suggests a need for continued monitoring of care satisfaction over time to determine whether differences by region persist. We grouped respondents into geographic region based on the location where they had received their most recent VA care of any type. Many veterans receive care at multiple VA locations. Thus, it is possible that some veterans received their amputation care at a non-VA facility or a VA facility in a different region.

Our findings related to prosthetic limb care services satisfaction are generalizable to veteran prosthesis users. Findings may not be generalizable to nonusers, because in our study, the CSS only was administered to prosthesis users. Thus, we were unable to identify factors associated with care satisfaction for persons who were not current users of an upper limb prosthesis.

The study findings confirmed that most veterans with ULA receive amputation-related care in the VA or DoD. We compared CSS and Quality of Care item scores for those who reported receiving care at the VA or DoD vs elsewhere. Amputation care within the VA is complex. Some services are provided at VA facilities and some are ordered by VA clinicians but provided by community-based HCPs. However, we found that better (though not statistically significantly different) CSS scores and several Quality of Care items were endorsed by a significantly more of those reporting care in the VA or DoD as compared to elsewhere. Given the dissemination of a rehabilitation of upper limb amputees CPG, we hypothesized that VA and DoD HCPs would be more aware of care guidelines and would provide better care. Overall, our findings supported this hypothesis while also suggesting that areas such as caregiver involvement and peer visitation may benefit from additional attention and program improvement.

We used longitudinal data to describe and compare CSS and Quality of Care Index scores. Our analyses did not detect any statistically significant differences between baseline and follow-up. This finding may reflect that this was a relatively stable population with regard to amputation experiences given the mean time since amputation was 31.4 years. However, we also recognize that our measures may not have captured all aspects of care satisfaction or quality. It is possible that there were other changes that had occurred over the course of the year that were not captured by the CSS or by the Quality of Care Index. It is also possible that some implementation and adoption of the CPG had happened prior to our baseline survey. Finally, it is possible that some elements of the CPG have not yet been fully integrated into clinical care. We believe that the latter is likely, given that nearly 80% of respondents did not report receiving any amputation care within the past year at follow-up, though the CPGs recommend an annual visit.

Aside from recall bias, 2 explanations must be considered relative to the low rate of adherence to the CPG recommendation for an annual follow-up. The first is that the CPG simply may not be widely adopted. The second is that the majority of patients with ULA who use prostheses use a body-powered system. These tend to be low maintenance, long-lasting systems and may ultimately not need annual maintenance and repair. Further, if the veteran’s body-powered system is functioning properly and health status has not changed, they may simply be opting out of an annual visit despite the CPG recommendation. Nonetheless, this apparent low rate of annual follow-up emphasizes the need for additional process improvement measures for the VA.

Strengths and Limitations

The VA provides a unique setting for a nationally representative study of amputation rehabilitation because it has centralized data sources that can be used to identify veterans with ULA. Our study had a strong response rate, and its prosthetic limb care satisfaction findings are generalizable to all veterans with major ULA who received VA care from 2010 to 2015. However, there are limits to generalizability outside of this population to civilians or to veterans who do not receive VA care. To examine possible nonresponse bias, which could limit generalizability, we compared the baseline characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents to the follow-up study (eAppendix 4 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). There were no significant differences in satisfaction, quality of care, or receipt of amputation-related care between those lost to follow-up and those with follow-up data. Although, we did find small differences in gender, race, and service era (defined by amputation date). We do not believe that these differences threaten the interpretation of findings at follow-up, but there may be limits to generalizability of these findings to the full baseline sample. The data were from a telephone survey of veterans. It is possible that some veterans did not recall their care receipt or did not understand some of the questions and thus may not have accurately answered questions related to type of care received or the timing of that care.

Our interpretation of findings comparing care received within the VA and DoD or elsewhere is also limited because we cannot say with certainty whether those who indicated no care in the VA or DoD actually had care that was sponsored by the VA or DoD as contract or fee-basis care. Just 8 respondents indicated that they had received care only outside of the VA or DoD in the prior year. There were also some limitations in the collection of data about care location. We asked about receipt of amputation care in the prior year and about location of any amputation care received between baseline and follow-up, and there were differences in responses. Thus, we used a combination of these items to identify location of care received in the prior year.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our study provides novel, important findings about the satisfaction with prosthetic limb care services and quality of amputation rehabilitation care for veterans. Findings from this study can be used to address amputation and prosthetic limb care satisfaction and quality weaknesses highlighted and to benchmark care satisfaction and CPG compliance. Other studies evaluating care guideline compliance have used indicators obtained from clinical records or data repositories.13-15 Future work could combine self-reported satisfaction and care quality measures with indicators obtained from clinical or repository sources to provide a more complete snapshot of care delivery.

Conclusions

We reported on a national survey of veterans with major upper limb loss that assessed satisfaction with prosthetic limb care services and quality of amputation care. Satisfaction with prosthetic limb care was independently associated with satisfaction with the prosthesis, and receipt of care within the prior year. Most of the veterans surveyed received care within the VA or DoD and reported receiving higher quality of care, when compared with those who received care outside of the VA or DoD. Satisfaction with care and quality of care were stable over the year of this study. Data presented in this study can serve to direct VA amputation care process improvement initiatives as benchmarks for future work. Future studies are needed to track satisfaction with and quality of care for veterans with ULA.

1. Resnik L, Ekerholm S, Borgia M, Clark MA. A national study of veterans with major upper limb amputation: Survey methods, participants, and summary findings. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0213578. Published 2019 Mar 14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0213578

2. US Department of Defense, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Management of Upper Extremity Amputation Rehabilitation Working Group. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for the management of upper extremity amputation rehabilitation.Published 2014. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/Rehab/UEAR/VADoDCPGManagementofUEAR121614Corrected508.pdf

3. Jette AM. The Promise of Assistive Technology to Enhance Work Participation. Phys Ther. 2017;97(7):691-692. doi:10.1093/ptj/pzx054

4. Webster JB, Poorman CE, Cifu DX. Guest editorial: Department of Veterans Affairs amputations system of care: 5 years of accomplishments and outcomes. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2014;51(4):vii-xvi. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2014.01.0024

5. Scholten J, Poorman C, Culver L, Webster JB. Department of Veterans Affairs polytrauma telerehabilitation: twenty-first century care. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2019;30(1):207-215. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2018.08.003

6. Melcer T, Walker J, Bhatnagar V, Richard E. Clinic use at the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs following combat related amputations. Mil Med. 2020;185(1-2):e244-e253. doi:10.1093/milmed/usz149

7. Berke GM, Fergason J, Milani JR, et al. Comparison of satisfaction with current prosthetic care in veterans and servicemembers from Vietnam and OIF/OEF conflicts with major traumatic limb loss. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(4):361-371. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.12.0193

8. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Inspector General. Healthcare inspection prosthetic limb care in VA facilities. Published March 8, 2012. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-11-02138-116.pdf 9. American Association for Public Opinion Research. Response rates - an overview. Accessed February 18, 2021. https://www.aapor.org/Education-Resources/For-Researchers/Poll-Survey-FAQ/Response-Rates-An-Overview.aspx

10. Heinemann AW, Bode RK, O’Reilly C. Development and measurement properties of the Orthotics and Prosthetics Users’ Survey (OPUS): a comprehensive set of clinical outcome instruments. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2003;27(3):191-206. doi:10.1080/03093640308726682

11. Desmond DM, MacLachlan M. Factor structure of the Trinity Amputation and Prosthesis Experience Scales (TAPES) with individuals with acquired upper limb amputations. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;84(7):506-513. doi:10.1097/01.phm.0000166885.16180.63

12. Resnik L, Borgia M, Heinemann AW, Clark MA. Prosthesis satisfaction in a national sample of veterans with upper limb amputation. Prosthet Orthot Int. 2020;44(2):81-91. doi:10.1177/0309364619895201

13. Ho TH, Caughey GE, Shakib S. Guideline compliance in chronic heart failure patients with multiple comorbid diseases: evaluation of an individualised multidisciplinary model of care. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e93129. Published 2014 Apr 8. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0093129

14. Mitchell KB, Lin H, Shen Y, et al. DCIS and axillary nodal evaluation: compliance with national guidelines. BMC Surg. 2017;17(1):12. Published 2017 Feb 7. doi:10.1186/s12893-017-0210-5

15. Moesker MJ, de Groot JF, Damen NL, et al. Guideline compliance for bridging anticoagulation use in vitamin-K antagonist patients; practice variation and factors associated with non-compliance. Thromb J. 2019;17:15. Published 2019 Aug 5. doi:10.1186/s12959-019-0204-x

Veterans with upper limb amputation (ULA) are a small, but important population, who have received more attention in the past decade due to the increased growth of the population of veterans with conflict-related amputation from recent military engagements. Among the 808 veterans with ULA receiving any care in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from 2010 to 2015 who participated in our national study, an estimated 28 to 35% had a conflict-related amputation.1 The care of these individuals with ULA is highly specialized, and there is a recognized shortage of experienced professionals in this area.2,3 The provision of high-quality prosthetic care is increasingly complex with advances in technology, such as externally powered devices with multiple functions.

The VA is a comprehensive, integrated health care system that serves more than 8.9 million veterans each year. Interdisciplinary amputation care is provided within the VA through a traditional clinic setting or by using one of several currently available virtual care modalities.4,5 In consultation with the veteran, VA health care providers (HCPs) prescribe prostheses and services based on the clinical needs and furnish authorized items and services to eligible veterans. Prescribed items and/or services are furnished either by internal VA resources or through a community-based prosthetist who is an authorized vendor or contractor. Although several studies have reported that the majority of veterans with ULA utilize VA services for at least some aspects of their health care, little is known about: (1) prosthetic limb care satisfaction or the quality of care that veterans receive; or (2) how care within the VA or Department of Defense (DoD) compares with care provided in the civilian sector.6-8

Earlier studies that examined the amputation rehabilitation services received by veterans with ULA pointed to quality gaps in care and differences in satisfaction in the VA and DoD when compared with the civilian sector but were limited in their scope and methodology.7,8 A 2008 study of veterans of the Vietnam War, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) compared satisfaction by location of care receipt (DoD only, VA only, private only, and multiple sources). That study dichotomized response categories for items related to satisfaction with care (satisfied/not), but did not estimate degree of satisfaction, calculate summary scores of the items, or utilize validated care satisfaction metrics. That study found that a greater proportion of Vietnam War veterans (compared with OIF/OEF veterans receiving care in the private sector) agreed that they “had a role in choosing prosthesis” and disagreed that they wanted to change their current prosthesis to another type.7 The assumption made by the authors is that much of this private sector care was actually VA-sponsored care prescribed and procured by the VA but delivered in the community. However, no data were collected to confirm or refute this assumption, and it is possible that some care was both VA sponsored and delivered, some was VA sponsored but commercially delivered, and in some cases, care was sponsored by other sources and delivered in still other facilities.

A 2012 VA Office of the Inspector General study of OIF, OEF, and Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans reported lower prosthetic satisfaction for veterans with upper limb when compared with lower limb amputation and described respondents concerns about lack of VA prosthetic expertise, difficulty with accessing VA services, and dissatisfaction with the sometimes lengthy approval process for obtaining fee-basis or VA contract care.8 Although this report suggested that there were quality gaps and areas for improvement, it did not employ validated metrics of prosthesis or care satisfaction and instead relied on qualitative data collected through telephone interviews.

Given the VA effort to enhance the quality and consistency of its amputation care services through the formal establishment of the Amputation System of Care, which began in 2008, further evaluation of care satisfaction and quality of care is warranted. In 2014 the VA and DoD released the first evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the rehabilitation of persons with ULA.2 The CPG describes care paths to improve outcomes and basic tenets of amputation rehabilitation care and can be used to identify process activities that are essential aspects of quality care. However, the extent to which the CPG has impacted the quality and timeliness of care for veterans with ULA are presently unclear.

Thus, the purposes of this study were to: (1) measure veteran satisfaction with prosthetic limb care and identify factors associated with service satisfaction; (2) assess quality indicators that potentially reflect CPG) adoption; (3) compare care satisfaction and quality for those who received care in or outside of the VA or DoD; and (4) evaluate change in satisfaction over time.

Methods

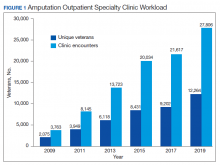

The study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Study #16-20) and Human Research Protection Office, U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command. The sampling frame consisted of veterans with major ULA who received care in the VA between 2010 and 2015 identified in VA Corporate Data Warehouse. We sent recruitment packages to nondeceased veterans who had current addresses and phone numbers. Those who did not opt out or inform us that they did not meet eligibility criteria were contacted by study interviewers. A waiver of documentation of written informed consent was obtained from the VA Central IRB. When reached by the study interviewer, Veterans provided oral informed consent. At baseline, 808 veterans were interviewed for a response rate of 47.7% as calculated by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) methodology.9 Follow-up interviews approximately 1 year later (mean [SD] 367 [16.8] days), were conducted with 585 respondents for a 72.4% response rate (Figure).

Survey Content

Development and pilot testing of the survey instrument previously was reported.1 The content of the survey drew from existing survey items and metrics, and included new items specifically designed to address patterns of amputation care, based on care goals within the CPG. All new and modified items were tested and refined through cognitive interviews with 10 participants, and tested with an additional 13 participants.

The survey collected data on demographics, amputation characteristics (year of amputation, level, laterality, and etiology), current prosthesis use, and type of prosthesis. This article focused on the sections of the survey pertaining to satisfaction with prosthetic care and indicators of quality of care. A description of the content of the full survey and a synopsis of overall findings are reported in a prior publication.1 The key independent, dependent, and other variables utilized in the analyses reported in this manuscript are described below.

Primary Independent Variables

In the follow-up survey, we asked respondents whether they had any amputation care in the prior 12 months, and if so to indicate where they had gone for care. We categorized respondents as having received VA/DoD care if they reported any care at the VA or DoD, and as having received non-VA/DoD care if they did not report care at the VA or DoD but indicated that they had received amputation care between baseline and follow-up.

Two primary outcomes were utilized; the Orthotics and Prosthetics User’s Survey (OPUS), client satisfaction with services scale (CSS), and a measure of care quality specifically developed for this study. The CSS is a measure developed specifically for orthotic and prosthesis users.10 This 11-item scale measures satisfaction with prosthetic limb services and contains items evaluating facets of care such as courtesy received from prosthetists and clinical staff, care coordination, appointment wait time, willingness of the prosthetist to listen to participant concerns, and satisfaction with prosthesis training. Items are rated on a 4-point scale (strongly agree [1] to strongly disagree [4]), thus higher CSS scores indicate worse satisfaction with services. The CSS was administered only to prosthesis users.

The Quality of Care assessment developed for this study contained items pertaining to amputation related care receipt and care quality. These items were generated by the study team in consultation with representatives from the VA/DoD Extremity Amputation Center of Excellence after review of the ULA rehabilitation CPG. Survey questions asked respondents about the clinicians visited for amputation related care in the past 12 months, whether they had an annual amputation-related checkup, whether any clinician had assessed their function, worked with them to identify goals, and/or to develop an amputation-related care plan. Respondents were also asked whether there had been family/caregiver involvement in their care and care coordination, whether a peer visitor was involved in their initial care, whether they had received information about amputation management in the prior year, and whether they had amputation-related pain. Those that indicated that they had amputation-related pain were subsequently asked whether their pain was well managed, whether they used medication for pain management, and whether they used any nonpharmaceutical strategies.

Quality of Care Index

We initially developed 15 indicator items of quality of care. We selected 7 of the items to create a summary index. We omitted 3 items about pain management, since these items were completed only by participants who indicated that they had experienced pain; however, we examined the 3 pain items individually given the importance of this topic. We omitted an additional 2 items from the summary index because they would not be sensitive to change because they pertained to the care in the year after initial amputation. One of these items asked whether caregivers were involved in initial amputation management and the other asked whether a peer visit occurred after amputation. Another 3 items were omitted because they only were completed by small subsamples due to intentional skip patterns in the survey. These items addressed whether clinical HCPs discussed amputation care goals in the prior year, worked to develop a care plan in the prior year, or helped to coordinate care after a move. Completion rates for all items considered for the index are shown in eAppendix 1 (Available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). After item selection, we generated an index score, which was the number of reported “yes” responses to the seven relevant items.

Other Variables

We created a single variable called level/laterality which categorized ULA as unilateral or bilateral. We further categorized respondents with unilateral amputation by their amputation level. We categorized respondents as transradial for wrist joint or below the elbow amputations; transhumeral for at or above the elbow amputations; and shoulder for shoulder joint or forequarter amputations. Participants indicated the amputation etiology using 7 yes/no variables: combat injury, accident, burn, cancer, diabetes mellitus, and infection. Participants could select ≥ 1 etiology.

Primary prosthesis type was categorized as body powered, myoelectric/hybrid, cosmetic, other/unknown, or nonuser. The service era was classified based on amputation date as Before Vietnam, Vietnam War, After Vietnam to Gulf War, After Gulf War to September 10, 2001, and September 11, 2001 to present. For race, individuals with > 1 race were classified as other. We classified participants by region, using the station identification of the most recent VA medical center that they had visited between January 1, 2010 and December 30, 2015.

The survey also employed 2 measures of satisfaction with the prosthesis, the Trinity Amputation and Prosthetic Experience Scale (TAPES) satisfaction scale and the OPUS Client Satisfaction with Devices (CSD). TAPES consists of 10 items addressing color, shape, noise, appearance, weight, usefulness, reliability, fit, comfort and overall satisfaction.11 Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (5). An 8-item version of the CSD scale was created for this study, after conducting a Rasch analysis (using Winsteps version 4.4.2) of the original 11-item CSD. The 8 items assess satisfaction with prosthesis fit, weight, comfort, donning ease, appearance, durability, skin contact, and pain. Items are rated on a 4-point scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4); higher CSD scores indicate less satisfaction with devices. Psychometric analysis of the revised CSD score was reported in a prior publication.12 We also reported on the CSS using the original 10-item measure.

Data Analyses

We described characteristics of respondents at baseline and follow-up. We used baseline data to calculate CSS scores and described scores for all participants, for subgroups of unilateral and bilateral amputees, and for unilateral amputees stratified by amputation level. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the CSS item and total scores of 461 prosthesis users with unilateral amputation and 29 with bilateral amputation. To identify factors that we hypothesized might be associated with CSS scores at baseline, we developed separate bivariate linear regression models. We added those factors that were associated with CSS scores at P ≤ .1 in bivariate analyses to a multivariable linear regression model of factors associated with CSS score. The P ≤ .1 threshold was used to ensure that relevant confounders were controlled for in regression models. We excluded 309 participants with no reported prosthesis use (who were not asked to complete the CSS), 20 participants with other/unknown prosthesis types, and 106 with missing data on amputation care in the prior year or on satisfaction metrics. We used baseline data for this analysis to maximize the sample size.

We compared CSS scores for those who reported receiving care within or outside of the VA or DoD in the prior year, using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney rank tests. We also compared scores of individual quality of care items for these groups using Fisher exact tests. We chose to examine individual items rather than the full Index because several items specified care receipt within the VA and thus would be inappropriate to utilize in comparisons by site location; however, we described responses to all items. In these analyses, we excluded 2 respondents who had conflicting information regarding location of care. We used follow-up data for this analysis because it allowed us to identify location of care received in the prior year.

We also described the CSS scores, the 7-item Quality of Care Index and responses to other items related to quality of care at baseline and follow-up. To examine whether satisfaction with prosthetic care or aspects of care quality had changed over time, we compared baseline and follow-up CSS and quality of care scores for respondents who had measures at both times using Wilcoxon signed ranks tests. Individual items were compared using McNemar tests.

Results

Respondents were 97.4% male and included 776 unilateral amputees and 32 bilateral amputees with a mean (SD) age of 63.3 (14.1) years (Table 1). Respondents had lost their limbs a mean (SD) 31.4 (14.1) years prior, and half were transradial, 34.2% transhumeral, and 11.6% shoulder amputation. At baseline 185 (22.9%) participants received amputation-related care in the prior year and 118 (20.2%) participants received amputation-related care within 1 year of follow-up. Of respondents, 113 (19.3%) stated that their care was between baseline and follow-up and 89 (78.8%) of these received care at either the VA, the DoD or both; just 16 (14.2%) received care elsewhere.

Mean (SD) CSS scores were highest (lower satisfaction) for those with amputation at the shoulder and lowest for those with transhumeral amputation: 42.2 (20.0) vs 33.4 (20.8). Persons with bilateral amputation were less satisfied in almost every category when compared with those with unilateral amputation, although the total CSS score was not substantially different. Wilcoxon rank sum analyses revealed statistically significant differences in wait time satisfaction: bilateral amputees were less satisfied than unilateral amputees. Factors associated with overall CSS score in bivariate analyses were CSD score, TAPES score, amputation care receipt, prosthesis type, race, and region of care (eAppendix 2, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096).

In the multivariate regression model of baseline CSS scores, only 2 variables were independently associated with CSS scores: CSD score and recent amputation care (Table 3). For each 1-point increase in CSD score there was a 0.7 point increase in CSS score. Those with amputation care in the prior year had higher satisfaction when compared with those who had not received care (P = .003).

For participants who indicated that they received amputation care between baseline and follow-up, CSS mean (SD) scores were better, but not statistically different, for those who reported care in the VA or DoD vs private care, 31.6 (22.6) vs 38.0 (17.7) (Table 4). When compared with community-based care, more participants who received care in the VA or DoD in the prior year had a functional assessment in that time period (33.7% vs 7.1%, P = .06), were contacted by HCPs outside of appointments (42.7% vs 18.8%, P = .07), and received information about amputation care in the prior year (41.6% vs 0%, P =.002). There was no difference in the proportion whose family/caregivers were involved in care in the prior year.

No statistically significant differences were observed in paired comparisons of the CSS and Quality of Care Index at baseline or follow-up for all participants with data at both time points (Table 5; eAppendix 3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). Individual pain measures did not differ significantly between timepoints. Quality Index mean (SD) scores were 1.3 (1.5) and 1.2 (1.5) at baseline and follow-up, respectively (P = .07). For the 214 prosthesis users with longitudinal data, baseline CSS mean (SD) scores were generally worse at baseline than at follow-up: 34.4 (19.8) vs 32.5 (21.0) (P = .23). Family/caregiver involvement in amputation care was significantly higher in the year before baseline when compared with the year prior to follow-up (24.4% vs 17.7%, P = .001). There were no other statistically significant differences in Quality of Care items between baseline and follow-up.

Discussion

Our longitudinal study provides insights into the experiences of veterans with major ULA related to satisfaction with prosthetic limb care services and receipt of amputation-related care. We reported on the development and use of a new summary measure of amputation care quality, which we designed to capture some of the key elements of care quality as provided in the VA/DoD CPG.2

We used baseline data to identify factors independently associated with prosthetic limb care satisfaction as measured by a previously validated measure, the OPUS CSS. The CSS addresses satisfaction with prosthetic limb services and does not reflect satisfaction with other amputation care services. We found that persons who received amputation care in the prior year had CSS scores that were a mean 5.1 points better than those who had not received recent care. Although causality cannot be determined with this investigation, this finding highlights an important relationship between frequency of care and satisfaction, which can be leveraged by the VA in future care initiatives. Care satisfaction was also better by 0.7 points for every 1-point decrease (indicating higher satisfaction) in the OPUS CSD prosthetic satisfaction scale. This finding isn’t surprising, given that a major purpose of prosthetic limb care services is to procure and fit a satisfactory device. To determine whether these same relationships were observed in the smaller, longitudinal cohort data at follow-up, we repeated these models and found similar relationships between recent care receipt and prosthesis satisfaction and satisfaction with services. We believe that these findings are meaningful and emphasize the importance of both service and device satisfaction to the veteran with an ULA. Lower service satisfaction scores among those with amputations at the shoulder and those with bilateral limb loss suggest that these individuals may benefit from different service delivery approaches.

We did observe a difference in satisfaction scores by geographic region in the follow-up (but not the baseline) data with satisfaction higher in the Western vs the Southern region (data not shown). This finding suggests a need for continued monitoring of care satisfaction over time to determine whether differences by region persist. We grouped respondents into geographic region based on the location where they had received their most recent VA care of any type. Many veterans receive care at multiple VA locations. Thus, it is possible that some veterans received their amputation care at a non-VA facility or a VA facility in a different region.

Our findings related to prosthetic limb care services satisfaction are generalizable to veteran prosthesis users. Findings may not be generalizable to nonusers, because in our study, the CSS only was administered to prosthesis users. Thus, we were unable to identify factors associated with care satisfaction for persons who were not current users of an upper limb prosthesis.

The study findings confirmed that most veterans with ULA receive amputation-related care in the VA or DoD. We compared CSS and Quality of Care item scores for those who reported receiving care at the VA or DoD vs elsewhere. Amputation care within the VA is complex. Some services are provided at VA facilities and some are ordered by VA clinicians but provided by community-based HCPs. However, we found that better (though not statistically significantly different) CSS scores and several Quality of Care items were endorsed by a significantly more of those reporting care in the VA or DoD as compared to elsewhere. Given the dissemination of a rehabilitation of upper limb amputees CPG, we hypothesized that VA and DoD HCPs would be more aware of care guidelines and would provide better care. Overall, our findings supported this hypothesis while also suggesting that areas such as caregiver involvement and peer visitation may benefit from additional attention and program improvement.

We used longitudinal data to describe and compare CSS and Quality of Care Index scores. Our analyses did not detect any statistically significant differences between baseline and follow-up. This finding may reflect that this was a relatively stable population with regard to amputation experiences given the mean time since amputation was 31.4 years. However, we also recognize that our measures may not have captured all aspects of care satisfaction or quality. It is possible that there were other changes that had occurred over the course of the year that were not captured by the CSS or by the Quality of Care Index. It is also possible that some implementation and adoption of the CPG had happened prior to our baseline survey. Finally, it is possible that some elements of the CPG have not yet been fully integrated into clinical care. We believe that the latter is likely, given that nearly 80% of respondents did not report receiving any amputation care within the past year at follow-up, though the CPGs recommend an annual visit.

Aside from recall bias, 2 explanations must be considered relative to the low rate of adherence to the CPG recommendation for an annual follow-up. The first is that the CPG simply may not be widely adopted. The second is that the majority of patients with ULA who use prostheses use a body-powered system. These tend to be low maintenance, long-lasting systems and may ultimately not need annual maintenance and repair. Further, if the veteran’s body-powered system is functioning properly and health status has not changed, they may simply be opting out of an annual visit despite the CPG recommendation. Nonetheless, this apparent low rate of annual follow-up emphasizes the need for additional process improvement measures for the VA.

Strengths and Limitations

The VA provides a unique setting for a nationally representative study of amputation rehabilitation because it has centralized data sources that can be used to identify veterans with ULA. Our study had a strong response rate, and its prosthetic limb care satisfaction findings are generalizable to all veterans with major ULA who received VA care from 2010 to 2015. However, there are limits to generalizability outside of this population to civilians or to veterans who do not receive VA care. To examine possible nonresponse bias, which could limit generalizability, we compared the baseline characteristics of respondents and nonrespondents to the follow-up study (eAppendix 4 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). There were no significant differences in satisfaction, quality of care, or receipt of amputation-related care between those lost to follow-up and those with follow-up data. Although, we did find small differences in gender, race, and service era (defined by amputation date). We do not believe that these differences threaten the interpretation of findings at follow-up, but there may be limits to generalizability of these findings to the full baseline sample. The data were from a telephone survey of veterans. It is possible that some veterans did not recall their care receipt or did not understand some of the questions and thus may not have accurately answered questions related to type of care received or the timing of that care.

Our interpretation of findings comparing care received within the VA and DoD or elsewhere is also limited because we cannot say with certainty whether those who indicated no care in the VA or DoD actually had care that was sponsored by the VA or DoD as contract or fee-basis care. Just 8 respondents indicated that they had received care only outside of the VA or DoD in the prior year. There were also some limitations in the collection of data about care location. We asked about receipt of amputation care in the prior year and about location of any amputation care received between baseline and follow-up, and there were differences in responses. Thus, we used a combination of these items to identify location of care received in the prior year.

Despite these limitations, we believe that our study provides novel, important findings about the satisfaction with prosthetic limb care services and quality of amputation rehabilitation care for veterans. Findings from this study can be used to address amputation and prosthetic limb care satisfaction and quality weaknesses highlighted and to benchmark care satisfaction and CPG compliance. Other studies evaluating care guideline compliance have used indicators obtained from clinical records or data repositories.13-15 Future work could combine self-reported satisfaction and care quality measures with indicators obtained from clinical or repository sources to provide a more complete snapshot of care delivery.

Conclusions

We reported on a national survey of veterans with major upper limb loss that assessed satisfaction with prosthetic limb care services and quality of amputation care. Satisfaction with prosthetic limb care was independently associated with satisfaction with the prosthesis, and receipt of care within the prior year. Most of the veterans surveyed received care within the VA or DoD and reported receiving higher quality of care, when compared with those who received care outside of the VA or DoD. Satisfaction with care and quality of care were stable over the year of this study. Data presented in this study can serve to direct VA amputation care process improvement initiatives as benchmarks for future work. Future studies are needed to track satisfaction with and quality of care for veterans with ULA.

Veterans with upper limb amputation (ULA) are a small, but important population, who have received more attention in the past decade due to the increased growth of the population of veterans with conflict-related amputation from recent military engagements. Among the 808 veterans with ULA receiving any care in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from 2010 to 2015 who participated in our national study, an estimated 28 to 35% had a conflict-related amputation.1 The care of these individuals with ULA is highly specialized, and there is a recognized shortage of experienced professionals in this area.2,3 The provision of high-quality prosthetic care is increasingly complex with advances in technology, such as externally powered devices with multiple functions.

The VA is a comprehensive, integrated health care system that serves more than 8.9 million veterans each year. Interdisciplinary amputation care is provided within the VA through a traditional clinic setting or by using one of several currently available virtual care modalities.4,5 In consultation with the veteran, VA health care providers (HCPs) prescribe prostheses and services based on the clinical needs and furnish authorized items and services to eligible veterans. Prescribed items and/or services are furnished either by internal VA resources or through a community-based prosthetist who is an authorized vendor or contractor. Although several studies have reported that the majority of veterans with ULA utilize VA services for at least some aspects of their health care, little is known about: (1) prosthetic limb care satisfaction or the quality of care that veterans receive; or (2) how care within the VA or Department of Defense (DoD) compares with care provided in the civilian sector.6-8

Earlier studies that examined the amputation rehabilitation services received by veterans with ULA pointed to quality gaps in care and differences in satisfaction in the VA and DoD when compared with the civilian sector but were limited in their scope and methodology.7,8 A 2008 study of veterans of the Vietnam War, Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), and Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF) compared satisfaction by location of care receipt (DoD only, VA only, private only, and multiple sources). That study dichotomized response categories for items related to satisfaction with care (satisfied/not), but did not estimate degree of satisfaction, calculate summary scores of the items, or utilize validated care satisfaction metrics. That study found that a greater proportion of Vietnam War veterans (compared with OIF/OEF veterans receiving care in the private sector) agreed that they “had a role in choosing prosthesis” and disagreed that they wanted to change their current prosthesis to another type.7 The assumption made by the authors is that much of this private sector care was actually VA-sponsored care prescribed and procured by the VA but delivered in the community. However, no data were collected to confirm or refute this assumption, and it is possible that some care was both VA sponsored and delivered, some was VA sponsored but commercially delivered, and in some cases, care was sponsored by other sources and delivered in still other facilities.

A 2012 VA Office of the Inspector General study of OIF, OEF, and Operation New Dawn (OND) veterans reported lower prosthetic satisfaction for veterans with upper limb when compared with lower limb amputation and described respondents concerns about lack of VA prosthetic expertise, difficulty with accessing VA services, and dissatisfaction with the sometimes lengthy approval process for obtaining fee-basis or VA contract care.8 Although this report suggested that there were quality gaps and areas for improvement, it did not employ validated metrics of prosthesis or care satisfaction and instead relied on qualitative data collected through telephone interviews.

Given the VA effort to enhance the quality and consistency of its amputation care services through the formal establishment of the Amputation System of Care, which began in 2008, further evaluation of care satisfaction and quality of care is warranted. In 2014 the VA and DoD released the first evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (CPGs) for the rehabilitation of persons with ULA.2 The CPG describes care paths to improve outcomes and basic tenets of amputation rehabilitation care and can be used to identify process activities that are essential aspects of quality care. However, the extent to which the CPG has impacted the quality and timeliness of care for veterans with ULA are presently unclear.

Thus, the purposes of this study were to: (1) measure veteran satisfaction with prosthetic limb care and identify factors associated with service satisfaction; (2) assess quality indicators that potentially reflect CPG) adoption; (3) compare care satisfaction and quality for those who received care in or outside of the VA or DoD; and (4) evaluate change in satisfaction over time.

Methods

The study was approved by the VA Central Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Study #16-20) and Human Research Protection Office, U.S. Army Medical Research and Development Command. The sampling frame consisted of veterans with major ULA who received care in the VA between 2010 and 2015 identified in VA Corporate Data Warehouse. We sent recruitment packages to nondeceased veterans who had current addresses and phone numbers. Those who did not opt out or inform us that they did not meet eligibility criteria were contacted by study interviewers. A waiver of documentation of written informed consent was obtained from the VA Central IRB. When reached by the study interviewer, Veterans provided oral informed consent. At baseline, 808 veterans were interviewed for a response rate of 47.7% as calculated by the American Association for Public Opinion Research (AAPOR) methodology.9 Follow-up interviews approximately 1 year later (mean [SD] 367 [16.8] days), were conducted with 585 respondents for a 72.4% response rate (Figure).

Survey Content

Development and pilot testing of the survey instrument previously was reported.1 The content of the survey drew from existing survey items and metrics, and included new items specifically designed to address patterns of amputation care, based on care goals within the CPG. All new and modified items were tested and refined through cognitive interviews with 10 participants, and tested with an additional 13 participants.

The survey collected data on demographics, amputation characteristics (year of amputation, level, laterality, and etiology), current prosthesis use, and type of prosthesis. This article focused on the sections of the survey pertaining to satisfaction with prosthetic care and indicators of quality of care. A description of the content of the full survey and a synopsis of overall findings are reported in a prior publication.1 The key independent, dependent, and other variables utilized in the analyses reported in this manuscript are described below.

Primary Independent Variables

In the follow-up survey, we asked respondents whether they had any amputation care in the prior 12 months, and if so to indicate where they had gone for care. We categorized respondents as having received VA/DoD care if they reported any care at the VA or DoD, and as having received non-VA/DoD care if they did not report care at the VA or DoD but indicated that they had received amputation care between baseline and follow-up.

Two primary outcomes were utilized; the Orthotics and Prosthetics User’s Survey (OPUS), client satisfaction with services scale (CSS), and a measure of care quality specifically developed for this study. The CSS is a measure developed specifically for orthotic and prosthesis users.10 This 11-item scale measures satisfaction with prosthetic limb services and contains items evaluating facets of care such as courtesy received from prosthetists and clinical staff, care coordination, appointment wait time, willingness of the prosthetist to listen to participant concerns, and satisfaction with prosthesis training. Items are rated on a 4-point scale (strongly agree [1] to strongly disagree [4]), thus higher CSS scores indicate worse satisfaction with services. The CSS was administered only to prosthesis users.

The Quality of Care assessment developed for this study contained items pertaining to amputation related care receipt and care quality. These items were generated by the study team in consultation with representatives from the VA/DoD Extremity Amputation Center of Excellence after review of the ULA rehabilitation CPG. Survey questions asked respondents about the clinicians visited for amputation related care in the past 12 months, whether they had an annual amputation-related checkup, whether any clinician had assessed their function, worked with them to identify goals, and/or to develop an amputation-related care plan. Respondents were also asked whether there had been family/caregiver involvement in their care and care coordination, whether a peer visitor was involved in their initial care, whether they had received information about amputation management in the prior year, and whether they had amputation-related pain. Those that indicated that they had amputation-related pain were subsequently asked whether their pain was well managed, whether they used medication for pain management, and whether they used any nonpharmaceutical strategies.

Quality of Care Index

We initially developed 15 indicator items of quality of care. We selected 7 of the items to create a summary index. We omitted 3 items about pain management, since these items were completed only by participants who indicated that they had experienced pain; however, we examined the 3 pain items individually given the importance of this topic. We omitted an additional 2 items from the summary index because they would not be sensitive to change because they pertained to the care in the year after initial amputation. One of these items asked whether caregivers were involved in initial amputation management and the other asked whether a peer visit occurred after amputation. Another 3 items were omitted because they only were completed by small subsamples due to intentional skip patterns in the survey. These items addressed whether clinical HCPs discussed amputation care goals in the prior year, worked to develop a care plan in the prior year, or helped to coordinate care after a move. Completion rates for all items considered for the index are shown in eAppendix 1 (Available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). After item selection, we generated an index score, which was the number of reported “yes” responses to the seven relevant items.

Other Variables

We created a single variable called level/laterality which categorized ULA as unilateral or bilateral. We further categorized respondents with unilateral amputation by their amputation level. We categorized respondents as transradial for wrist joint or below the elbow amputations; transhumeral for at or above the elbow amputations; and shoulder for shoulder joint or forequarter amputations. Participants indicated the amputation etiology using 7 yes/no variables: combat injury, accident, burn, cancer, diabetes mellitus, and infection. Participants could select ≥ 1 etiology.

Primary prosthesis type was categorized as body powered, myoelectric/hybrid, cosmetic, other/unknown, or nonuser. The service era was classified based on amputation date as Before Vietnam, Vietnam War, After Vietnam to Gulf War, After Gulf War to September 10, 2001, and September 11, 2001 to present. For race, individuals with > 1 race were classified as other. We classified participants by region, using the station identification of the most recent VA medical center that they had visited between January 1, 2010 and December 30, 2015.

The survey also employed 2 measures of satisfaction with the prosthesis, the Trinity Amputation and Prosthetic Experience Scale (TAPES) satisfaction scale and the OPUS Client Satisfaction with Devices (CSD). TAPES consists of 10 items addressing color, shape, noise, appearance, weight, usefulness, reliability, fit, comfort and overall satisfaction.11 Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale from very dissatisfied (1) to very satisfied (5). An 8-item version of the CSD scale was created for this study, after conducting a Rasch analysis (using Winsteps version 4.4.2) of the original 11-item CSD. The 8 items assess satisfaction with prosthesis fit, weight, comfort, donning ease, appearance, durability, skin contact, and pain. Items are rated on a 4-point scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4); higher CSD scores indicate less satisfaction with devices. Psychometric analysis of the revised CSD score was reported in a prior publication.12 We also reported on the CSS using the original 10-item measure.

Data Analyses

We described characteristics of respondents at baseline and follow-up. We used baseline data to calculate CSS scores and described scores for all participants, for subgroups of unilateral and bilateral amputees, and for unilateral amputees stratified by amputation level. Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the CSS item and total scores of 461 prosthesis users with unilateral amputation and 29 with bilateral amputation. To identify factors that we hypothesized might be associated with CSS scores at baseline, we developed separate bivariate linear regression models. We added those factors that were associated with CSS scores at P ≤ .1 in bivariate analyses to a multivariable linear regression model of factors associated with CSS score. The P ≤ .1 threshold was used to ensure that relevant confounders were controlled for in regression models. We excluded 309 participants with no reported prosthesis use (who were not asked to complete the CSS), 20 participants with other/unknown prosthesis types, and 106 with missing data on amputation care in the prior year or on satisfaction metrics. We used baseline data for this analysis to maximize the sample size.

We compared CSS scores for those who reported receiving care within or outside of the VA or DoD in the prior year, using Wilcoxon Mann-Whitney rank tests. We also compared scores of individual quality of care items for these groups using Fisher exact tests. We chose to examine individual items rather than the full Index because several items specified care receipt within the VA and thus would be inappropriate to utilize in comparisons by site location; however, we described responses to all items. In these analyses, we excluded 2 respondents who had conflicting information regarding location of care. We used follow-up data for this analysis because it allowed us to identify location of care received in the prior year.

We also described the CSS scores, the 7-item Quality of Care Index and responses to other items related to quality of care at baseline and follow-up. To examine whether satisfaction with prosthetic care or aspects of care quality had changed over time, we compared baseline and follow-up CSS and quality of care scores for respondents who had measures at both times using Wilcoxon signed ranks tests. Individual items were compared using McNemar tests.

Results

Respondents were 97.4% male and included 776 unilateral amputees and 32 bilateral amputees with a mean (SD) age of 63.3 (14.1) years (Table 1). Respondents had lost their limbs a mean (SD) 31.4 (14.1) years prior, and half were transradial, 34.2% transhumeral, and 11.6% shoulder amputation. At baseline 185 (22.9%) participants received amputation-related care in the prior year and 118 (20.2%) participants received amputation-related care within 1 year of follow-up. Of respondents, 113 (19.3%) stated that their care was between baseline and follow-up and 89 (78.8%) of these received care at either the VA, the DoD or both; just 16 (14.2%) received care elsewhere.

Mean (SD) CSS scores were highest (lower satisfaction) for those with amputation at the shoulder and lowest for those with transhumeral amputation: 42.2 (20.0) vs 33.4 (20.8). Persons with bilateral amputation were less satisfied in almost every category when compared with those with unilateral amputation, although the total CSS score was not substantially different. Wilcoxon rank sum analyses revealed statistically significant differences in wait time satisfaction: bilateral amputees were less satisfied than unilateral amputees. Factors associated with overall CSS score in bivariate analyses were CSD score, TAPES score, amputation care receipt, prosthesis type, race, and region of care (eAppendix 2, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096).

In the multivariate regression model of baseline CSS scores, only 2 variables were independently associated with CSS scores: CSD score and recent amputation care (Table 3). For each 1-point increase in CSD score there was a 0.7 point increase in CSS score. Those with amputation care in the prior year had higher satisfaction when compared with those who had not received care (P = .003).

For participants who indicated that they received amputation care between baseline and follow-up, CSS mean (SD) scores were better, but not statistically different, for those who reported care in the VA or DoD vs private care, 31.6 (22.6) vs 38.0 (17.7) (Table 4). When compared with community-based care, more participants who received care in the VA or DoD in the prior year had a functional assessment in that time period (33.7% vs 7.1%, P = .06), were contacted by HCPs outside of appointments (42.7% vs 18.8%, P = .07), and received information about amputation care in the prior year (41.6% vs 0%, P =.002). There was no difference in the proportion whose family/caregivers were involved in care in the prior year.

No statistically significant differences were observed in paired comparisons of the CSS and Quality of Care Index at baseline or follow-up for all participants with data at both time points (Table 5; eAppendix 3 available at doi:10.12788/fp.0096). Individual pain measures did not differ significantly between timepoints. Quality Index mean (SD) scores were 1.3 (1.5) and 1.2 (1.5) at baseline and follow-up, respectively (P = .07). For the 214 prosthesis users with longitudinal data, baseline CSS mean (SD) scores were generally worse at baseline than at follow-up: 34.4 (19.8) vs 32.5 (21.0) (P = .23). Family/caregiver involvement in amputation care was significantly higher in the year before baseline when compared with the year prior to follow-up (24.4% vs 17.7%, P = .001). There were no other statistically significant differences in Quality of Care items between baseline and follow-up.

Discussion