User login

VA Lessons From Partnering in COVID-19 Clinical Trials

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), through its Office of Research and Development (ORD), supports an extensive and experienced clinical research enterprise, including the first multisite trials in the US.1 These resources contribute to the ORD support for the largest US integrated health care system, with a primary focus on the care and well-being of veterans. While the history of VA research has facilitated the creation of an experienced and organized research enterprise, the COVID-19 pandemic challenged VA to contribute even more significantly. These challenges became pronounced given the urgency associated with standing up VA sites for both therapeutic and vaccine trials.

VA Clinical Research Enterprise

The VA recognized an early need for an organized research response not only to address operational challenges resulting from COVID-19 but also ensure that the agency would be ready to support new scientific efforts focused specifically on the virus and related outcomes.2 As a result, the ORD took decisive action first by establishing itself as a central headquarters for VA COVID-19 research activities, and second, by leveraging existing resources, initiatives, and infrastructure to develop new mechanisms that would ensure that the VA was well positioned to develop or participate in research endeavors being driven by the VA as well federal, industry, and non-VA partners.

Prior to the pandemic, the ORD, through its Cooperative Studies Program (CSP), had strategies to address challenges associated with clinical trial startup and improved efficient conduct.3 For example, the VA Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES) is a consortium of 23 VA medical centers (VAMCs) dedicated to rapid startup and recruitment into VA-sponsored clinical trials. NODES provides site-level expertise on clinical trial management, including troubleshooting challenges that may occur during clinical research execution.4 Another initiative, Access to Clinical Trials (ACT) for Veterans, engaged industry, academic, patient advocacy, and other partners to identify potential regulatory and operational hurdles to efficient startup activities specific to externally sponsored multisite clinical trials. Under ACT for Veterans, stakeholders emphasized the importance of developing a single VA point of contact for external partners to work with to more efficiently understand and navigate the VA system. In turn, such a resource could be designed to facilitate substantive research and long-term relationships with compatible external partners. Targeted to launch in April 2020, the Partnered Research Program (PRP) was expedited to respond to the pandemic.

During the pandemic, new VA efforts included the creation of the VA CoronavirUs Research and Efficacy Studies (VA CURES) network, initially established as a clinical trial master protocol framework to support and maximize VA-funded COVID-19 trial efficiency.5 VA CURES joined the consortium of trials networks funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. It began treatment trials under Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccination (ACTIV), specifically ACTIV-4. The VA also partnered with the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) by organizing the VA International Coordinating Center (VA ICC) for other ACTIV trials (ACTIV-2 and -3). When approached to startup studies that included veterans and the VA health care system, these capabilities comprised the VA research response.

A Need for a New Approach

As the impact of the pandemic expanded and the need for effective treatments and vaccines grew, national calls were made to assess the capabilities and readiness of available clinical trials networks. Additionally, the US Department of Health and Human Services Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, ACTIV, NIAID Division of Clinical Research and Division of AIDS, and many pharmaceutical companies were starting to roll out trials of new therapeutics and vaccines. These groups approached the VA to help evaluate the safety and efficacy of several therapeutics and vaccines because they recognized several advantages of the VA enterprise, including its position as the nation’s largest integrated health care system, its diverse patient population, and its expertise in conducting clinical trials.

Although the VA was well positioned as an important player in a collaborative investigational approach to COVID-19 research, these trials required startup approaches that were significantly different from those it had employed in traditional, prepandemic, clinical research. Despite the VA being a single federal agency, each VAMC conducting research establishes its own practices to address both operational and regulatory requirements. This structure results in individual units that operate under different standard operating procedures. Efforts must be taken centrally to organize them into a singular network for the entire health care system. During a national crisis, when there was a need for rapid trial startup to answer safety and efficacy questions and participate under a common approach to protocol execution, this variability was neither manageable nor acceptable. Additionally, the intense resource demands associated with such research, coupled with frequent reporting requirements by VA leaders, Congress, and the White House, required that VAMCs function more like a single unit. Therefore, the ORD needed to develop VAMCs’ abilities to work collectively toward a common goal, share knowledge and experience, and capitalize on potential efficiencies concerning legal, regulatory, and operational processes.

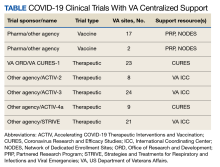

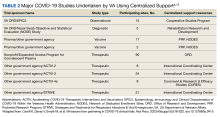

Beginning August 2020, 39 VAMCs joined 7 large-scale collaborative COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine trials. Through its COVID-19 Research Response Team, the ORD identified, engaged, and directed appropriate resources to support the VAMC under a centralized framework for study management (Table). Centralized management not only afforded VAMCs the opportunity to work more collectively and efficiently but also provided an important advantage by enabling the VA to collect and organize its experiences (and on occasion data) to provide a base for continual learning and improvement efforts. While others have described efforts undertaken across networks to advance learning health systems, the VA’s national scope and integration of research and clinical care allow greater opportunities to learn in a practical setting.6

Challenges and Best Practices

Using surveys, webinars, interviews, and observation from site and VA Central Office personnel, the ORD identified specific variables that prevented the VAMCs from quickly starting up as a clinical trial site. We also documented strategies, solutions, and recommendations for improving startup time lines. These were organized into 8 categories: (1) site infrastructure needs and capabilities; (2) study management roles and responsibilities; (3) educational resources and training; (4) local review requirements and procedures; (5) study design demands; (6) contracting and budgeting; (7) central-level systems and processes; and (8) communication between external partners and within the VA.

Site Infrastructure Needs and Capabilities

A primary impediment to rapid study startup was a lack of basic infrastructure, including staff, space, and the agility necessary for the changing demands of high-priority, high-enrolling trials. This observation is not unique to the VA.7 Initially, certain facilities located in hot spots where COVID-19 was more prevalent became high-interest targets for study placement, despite varying degrees of available research infrastructure. Furthermore, pandemic shutdowns and quarantines permitted fewer employees onsite. This resulted in inadequate staffing in personnel needed to support required startup activities and those needed to handle the high volume of study participants who were being recruited, screened, enrolled, and followed. Additionally, as clinical care needs and infection control practices were prioritized, clinical research space was often appropriated for these needs, making it difficult to find the space to conduct trials. Lastly, supply chain issues also posed unique challenges, sometimes making it difficult for participating VAMCs to obtain needed materials, such as IV solution bags of specific sizes and contents, safety injection needles, and IV line filters.

The VA was able to use central purchasing/contracting at coordinating centers or the VA Central Office to support investigators and assist with finding supplies and clinical research space. VAMCs with research operating budgets to cover startup costs were better positioned to handle funding delays. During the pandemic, the ORD further contracted to supply administrative support to research offices to address regulatory and other requirements needed for startup activities. The ability to expand such central contracts to procure clinical research staff and outpatient clinical research space may also prove useful in meeting key needs at a site.

Management Roles and Responsibilities

Ambiguous and variable roles and responsibilities among the various partners and stakeholders represented a challenge given the large-scale, national, or international operations involved in the trials. VA attempts to operate uniformly were further limited given that each sponsor or group had preferred methods for operating and/or organizing work under urgent time lines. For example, one trial involved a coordinating center, a contract research organization, and federal partners that each worked with individual sites. Consequently, VA study teams would receive messages that were conflicting or unclear.

The VA learned that studies need a single “source of truth” and/or central command structure in times of urgency. To mitigate conflicting messages, vaccine trials relied on a clearinghouse through the PRP to interpret requirements or work on behalf of all sites before key actions were taken. For studies with the NIAID, the VA relied on experienced staff at the CSP coordinating center at the Perry Point, Maryland, VAMC before beginning. This approach especially helped with the challenges of understaffing and sites’ lack of familiarity with complex platform trial designs and already-established network practices within the ACTIV-2 and ACTIV-3 studies.

Educational Resources and Training

Since VA participation in externally sponsored, multisite clinical trials traditionally relies on an individual VAMC study team and its local resources, transitioning to centralized approaches for COVID-19 multisite studies created barriers. Many VAMCs were unfamiliar with newer capabilities for more rapid regulatory reviews and approvals involving commercial institutional review boards (IRBs) and central VA information security and privacy reviews. While tools and resources were available to facilitate these processes, real-time use had not been fully tested. As a result, everyone had to learn as they went along.

The simultaneous establishment of workflows required the ORD to centralize operations and provide training and guidance to field personnel. Although many principal investigators and clinical research coordinators had trial experience, training required unlearning previous understandings of requirements to meet urgent time lines. ORD enterprise road maps, central tools, and training materials also were made available on a study-by-study basis. Open communication was vital to train on central study materials while opportunities to discuss, question, and share experiences and ideas were promoted. The ORD also sent regular emails to prepare for upcoming work and/or raise awareness of identified challenges.

Local Review Requirements/Procedures

The clinical trials were impacted by varying VAMC review requirements and approval processes. Although VA policy defines standard requirements, the timing and procedures are left to the individual facility to determine any local factors to accommodate and/or resource availability. While such an approach is well understood within the VA, external sponsors were not as familiar and assumed a more uniform approach across all sites. In response, some VAMCs established ad hoc research and development committee review procedures, allowing study teams to obtain the necessary reviews in a timely fashion. However, not all VAMCs had the infrastructure (especially when clinical personnel had been redeployed to other priorities) to respond with such agility. One critical role of the VA Central Office coordinating entities was to communicate and manage external sponsor and group expectations surrounding individual site review time lines. However, establishing policies and procedures that focus on streamlining local review processes helped to broadly mitigate the COVID-19 trial challenges.

Study Design Demands

The design of COVID-19 studies combined with the uncertainty of the pandemic required rapid protocol changes and adaptations that were often difficult to deliver. The multinetwork trials that the VA collaborated on were platform or master protocol designs. These designs emphasized overall goals (eg, treating patients requiring intensive care unit care). However, because this trial strategy also introduces complexities that may impact review and execution among those unfamiliar with it, there is a need for increased discussion and understanding of this methodology.8 For example, there can be shared control groups, reliance on specific criteria for halting because of safety or futility concerns, or continuation and expansion applied through an external review board. Delays may arise when changes to study protocols occur rapidly or frequently and necessitate new regulatory reviews, negotiation of new agreements, modifications to contracts, changes to entry criteria, etc.

While the VA has adopted a quality by design framework, VA investigators noted many missed opportunities related to looking at outcomes with new diagnostics, studies of serology, outcomes related to vaccinations, and understanding the natural history of disease in these trials.9 The limited opportunities for investigator input suggested that the advantages offered by platform designs were not maximized during pandemic-focused urgencies. It was unclear whether this barrier was created by a general lack of awareness by sponsors or a lack of opportunities. At the very least, quality by design approaches may help avoid redundancies in documentation or study processes at the central and site levels.

Contracting and Budgeting

Given external sponsorship of COVID-19 trials, efficient contracting and budgeting were critical for a rapid start up. The variability of processes associated with these trials created several challenges that were compounded by issues, such as site sub-agreements and budget documents that did not always go to the correct groups and individuals. Furthermore, the VA’s ability to use contracted resources (eg, tents, trailers, personnel) that external sponsors had built into their contracts was more difficult for VA as a federal agency governed by other statues and policies. This also put VAMCs at a disadvantage from a timing perspective, as the VA often required additional time to find equivalent solutions that met federal regulations.

Although the VA was able to establish contract solutions to some issues, time was still lost while working to secure initial funding. Additionally, for needs such as home phlebotomy—commended for convenience to veterans and research staff—and engaging a specialized research team in the Office of General Counsel, early awareness of protocol needs and sponsor solutions could allow VA to pursue alternatives sooner.

Central-Level Systems and Processes

Not all challenges were at the VAMC level. As the ORD explored solutions, it learned that various tools and study platforms were available but not considered. Applications, such as eConsent, and file-sharing platforms that met existing information security and privacy requirements were needed but had to comply with the Privacy Act of 1974, Federal Information Security Modernization Act, and other requirements. Using sponsor-provided devices, such as drug temperature monitoring equipment, required additional review to ensure that they met system requirements for a national health care system. In addition, the VA uses a clinical trials management review system; however, its implementation was new at the time these trials began. Furthermore, the system engaged with some commercial IRBs but not all. This resulted in additional delays as VAMCs and central resources worked to familiarize themselves with the system and procedures.

The ability to work collaboratively across the VA includes having a framework in which key startup processes are standardized. This allows for efficiency and minimizes variability. Also, all stakeholders should understand the importance of holding discussions to identify appropriate solutions, guidance, and instruction. Finally, the VA must strive to be more nimble when adapting technological, regulatory, and financial processes.

Internal and External Communication

The value of communication—both internal and external—cannot be understated. Minimizing confusion, managing expectations, and ensuring consistent messaging were essential for rapid trial execution. Despite being the second largest federal agency, the VA did not have a seat at the study leadership table for several protocols. When it joined later, several study aspects were set and/or difficult to revise. Challenges affecting time and securing resources have been noted. The ability to plan and then share expectations and responsibilities across and within the respective participating organizations early in the process was perhaps the single factor that was most addressable. The VA enterprise organization and integration with other units could accentuate key communications that would be essential in time-sensitive activities.

VA as a Partner for Future Research

Before the pandemic, the VA had already undertaken a path to enhance its ability to partner as part of the national biomedical research enterprise. The need for COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine trials accelerated opportunities to plan and develop processes and capabilities to advance this path. As a key strength for VA scientific activities, clinical trials represent a primary medium by which to develop its partnerships. Learning and development have become part of a culture that expedites opportunities for veterans who actively seek ways to contribute to medical knowledge and treatments for their peers and the nation.

CONCLUSIONS

Challenges associated with rapid startup and completion of clinical trials have been discussed for some time. During the pandemic, needs and barriers were magnified because of the heightened urgency for evidence-based therapeutics and vaccines. While the VA faced similar problems as well as those specific to it as a health care system, it had the opportunity to learn and more systematically implement solutions to help in its partnered efforts.10 As an enterprise, the VA hopes to apply lessons learned, strategies, and best practices to further its goals to enhance veteran access to clinical trials and respond to any future need to quickly establish evidence bases in pandemics and other health emergencies that warrant the rapid implementation of research.

Acknowledgments

The activities reported here were supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

1. Hays MT; US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development. A historical look at the establishment of the Department of Veterans Affairs Research & Development Program. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/ORD-85yrHistory.pdf

2. Garcia AP, Huang GD, Arnheim L, Ramoni R, Clancy C. The VA research enterprise: a platform for national partnerships toward evidence building and scientific innovation. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 5):S12-S17. doi:10.12788/fp.0425

3. Johnston SC, Lewis-Hall F, Bajpai A, et al. It’s time to harmonize clinical trial site standards. NAM Perspectives. October 9, 2017. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Its-Time-to-Harmonize-Clinical-Trial-Site-1.pdf

4. Condon DL, Beck D, Kenworthy-Heinige T, et al. A cross-cutting approach to enhancing clinical trial site success: the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES) model. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;6:78-84. Published 2017 Mar 29. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2017.03.006

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Master protocols: efficient clinical trial design strategies to expedite development of oncology drugs and biologics guidance for industry. March 2022. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/master-protocols-efficient-clinical-trial-design-strategies-expedite-development-oncology-drugs-and

6. IOM Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Care; Institute of Medicine. Continuous learning and improvement in health care. In: Integrating Research and Practice: Health System Leaders Working Toward High-Value Care: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press (US); 2015:chap 2. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK284654 7. Institute of Medicine (US). Building an infrastructure to support clinical trials. In: Envisioning a Transformed Clinical Trials Enterprise in the United States. National Academies Press (US); 2012:chap 5. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114656

8. Park JJH, Harari O, Dron L, Lester RT, Thorlund K, Mills EJ. An overview of platform trials with a checklist for clinical readers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;125:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.04.025

9. Meeker-O’Connell A, Glessner C, Behm M, et al. Enhancing clinical evidence by proactively building quality into clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2016;13(4):439-444. doi:10.1177/1740774516643491

10. McClure J, Asghar A, Krajec A, et al. Clinical trial facilitators: a novel approach to support the execution of clinical research at the study site level. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023;33:101106. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101106

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), through its Office of Research and Development (ORD), supports an extensive and experienced clinical research enterprise, including the first multisite trials in the US.1 These resources contribute to the ORD support for the largest US integrated health care system, with a primary focus on the care and well-being of veterans. While the history of VA research has facilitated the creation of an experienced and organized research enterprise, the COVID-19 pandemic challenged VA to contribute even more significantly. These challenges became pronounced given the urgency associated with standing up VA sites for both therapeutic and vaccine trials.

VA Clinical Research Enterprise

The VA recognized an early need for an organized research response not only to address operational challenges resulting from COVID-19 but also ensure that the agency would be ready to support new scientific efforts focused specifically on the virus and related outcomes.2 As a result, the ORD took decisive action first by establishing itself as a central headquarters for VA COVID-19 research activities, and second, by leveraging existing resources, initiatives, and infrastructure to develop new mechanisms that would ensure that the VA was well positioned to develop or participate in research endeavors being driven by the VA as well federal, industry, and non-VA partners.

Prior to the pandemic, the ORD, through its Cooperative Studies Program (CSP), had strategies to address challenges associated with clinical trial startup and improved efficient conduct.3 For example, the VA Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES) is a consortium of 23 VA medical centers (VAMCs) dedicated to rapid startup and recruitment into VA-sponsored clinical trials. NODES provides site-level expertise on clinical trial management, including troubleshooting challenges that may occur during clinical research execution.4 Another initiative, Access to Clinical Trials (ACT) for Veterans, engaged industry, academic, patient advocacy, and other partners to identify potential regulatory and operational hurdles to efficient startup activities specific to externally sponsored multisite clinical trials. Under ACT for Veterans, stakeholders emphasized the importance of developing a single VA point of contact for external partners to work with to more efficiently understand and navigate the VA system. In turn, such a resource could be designed to facilitate substantive research and long-term relationships with compatible external partners. Targeted to launch in April 2020, the Partnered Research Program (PRP) was expedited to respond to the pandemic.

During the pandemic, new VA efforts included the creation of the VA CoronavirUs Research and Efficacy Studies (VA CURES) network, initially established as a clinical trial master protocol framework to support and maximize VA-funded COVID-19 trial efficiency.5 VA CURES joined the consortium of trials networks funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. It began treatment trials under Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccination (ACTIV), specifically ACTIV-4. The VA also partnered with the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) by organizing the VA International Coordinating Center (VA ICC) for other ACTIV trials (ACTIV-2 and -3). When approached to startup studies that included veterans and the VA health care system, these capabilities comprised the VA research response.

A Need for a New Approach

As the impact of the pandemic expanded and the need for effective treatments and vaccines grew, national calls were made to assess the capabilities and readiness of available clinical trials networks. Additionally, the US Department of Health and Human Services Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, ACTIV, NIAID Division of Clinical Research and Division of AIDS, and many pharmaceutical companies were starting to roll out trials of new therapeutics and vaccines. These groups approached the VA to help evaluate the safety and efficacy of several therapeutics and vaccines because they recognized several advantages of the VA enterprise, including its position as the nation’s largest integrated health care system, its diverse patient population, and its expertise in conducting clinical trials.

Although the VA was well positioned as an important player in a collaborative investigational approach to COVID-19 research, these trials required startup approaches that were significantly different from those it had employed in traditional, prepandemic, clinical research. Despite the VA being a single federal agency, each VAMC conducting research establishes its own practices to address both operational and regulatory requirements. This structure results in individual units that operate under different standard operating procedures. Efforts must be taken centrally to organize them into a singular network for the entire health care system. During a national crisis, when there was a need for rapid trial startup to answer safety and efficacy questions and participate under a common approach to protocol execution, this variability was neither manageable nor acceptable. Additionally, the intense resource demands associated with such research, coupled with frequent reporting requirements by VA leaders, Congress, and the White House, required that VAMCs function more like a single unit. Therefore, the ORD needed to develop VAMCs’ abilities to work collectively toward a common goal, share knowledge and experience, and capitalize on potential efficiencies concerning legal, regulatory, and operational processes.

Beginning August 2020, 39 VAMCs joined 7 large-scale collaborative COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine trials. Through its COVID-19 Research Response Team, the ORD identified, engaged, and directed appropriate resources to support the VAMC under a centralized framework for study management (Table). Centralized management not only afforded VAMCs the opportunity to work more collectively and efficiently but also provided an important advantage by enabling the VA to collect and organize its experiences (and on occasion data) to provide a base for continual learning and improvement efforts. While others have described efforts undertaken across networks to advance learning health systems, the VA’s national scope and integration of research and clinical care allow greater opportunities to learn in a practical setting.6

Challenges and Best Practices

Using surveys, webinars, interviews, and observation from site and VA Central Office personnel, the ORD identified specific variables that prevented the VAMCs from quickly starting up as a clinical trial site. We also documented strategies, solutions, and recommendations for improving startup time lines. These were organized into 8 categories: (1) site infrastructure needs and capabilities; (2) study management roles and responsibilities; (3) educational resources and training; (4) local review requirements and procedures; (5) study design demands; (6) contracting and budgeting; (7) central-level systems and processes; and (8) communication between external partners and within the VA.

Site Infrastructure Needs and Capabilities

A primary impediment to rapid study startup was a lack of basic infrastructure, including staff, space, and the agility necessary for the changing demands of high-priority, high-enrolling trials. This observation is not unique to the VA.7 Initially, certain facilities located in hot spots where COVID-19 was more prevalent became high-interest targets for study placement, despite varying degrees of available research infrastructure. Furthermore, pandemic shutdowns and quarantines permitted fewer employees onsite. This resulted in inadequate staffing in personnel needed to support required startup activities and those needed to handle the high volume of study participants who were being recruited, screened, enrolled, and followed. Additionally, as clinical care needs and infection control practices were prioritized, clinical research space was often appropriated for these needs, making it difficult to find the space to conduct trials. Lastly, supply chain issues also posed unique challenges, sometimes making it difficult for participating VAMCs to obtain needed materials, such as IV solution bags of specific sizes and contents, safety injection needles, and IV line filters.

The VA was able to use central purchasing/contracting at coordinating centers or the VA Central Office to support investigators and assist with finding supplies and clinical research space. VAMCs with research operating budgets to cover startup costs were better positioned to handle funding delays. During the pandemic, the ORD further contracted to supply administrative support to research offices to address regulatory and other requirements needed for startup activities. The ability to expand such central contracts to procure clinical research staff and outpatient clinical research space may also prove useful in meeting key needs at a site.

Management Roles and Responsibilities

Ambiguous and variable roles and responsibilities among the various partners and stakeholders represented a challenge given the large-scale, national, or international operations involved in the trials. VA attempts to operate uniformly were further limited given that each sponsor or group had preferred methods for operating and/or organizing work under urgent time lines. For example, one trial involved a coordinating center, a contract research organization, and federal partners that each worked with individual sites. Consequently, VA study teams would receive messages that were conflicting or unclear.

The VA learned that studies need a single “source of truth” and/or central command structure in times of urgency. To mitigate conflicting messages, vaccine trials relied on a clearinghouse through the PRP to interpret requirements or work on behalf of all sites before key actions were taken. For studies with the NIAID, the VA relied on experienced staff at the CSP coordinating center at the Perry Point, Maryland, VAMC before beginning. This approach especially helped with the challenges of understaffing and sites’ lack of familiarity with complex platform trial designs and already-established network practices within the ACTIV-2 and ACTIV-3 studies.

Educational Resources and Training

Since VA participation in externally sponsored, multisite clinical trials traditionally relies on an individual VAMC study team and its local resources, transitioning to centralized approaches for COVID-19 multisite studies created barriers. Many VAMCs were unfamiliar with newer capabilities for more rapid regulatory reviews and approvals involving commercial institutional review boards (IRBs) and central VA information security and privacy reviews. While tools and resources were available to facilitate these processes, real-time use had not been fully tested. As a result, everyone had to learn as they went along.

The simultaneous establishment of workflows required the ORD to centralize operations and provide training and guidance to field personnel. Although many principal investigators and clinical research coordinators had trial experience, training required unlearning previous understandings of requirements to meet urgent time lines. ORD enterprise road maps, central tools, and training materials also were made available on a study-by-study basis. Open communication was vital to train on central study materials while opportunities to discuss, question, and share experiences and ideas were promoted. The ORD also sent regular emails to prepare for upcoming work and/or raise awareness of identified challenges.

Local Review Requirements/Procedures

The clinical trials were impacted by varying VAMC review requirements and approval processes. Although VA policy defines standard requirements, the timing and procedures are left to the individual facility to determine any local factors to accommodate and/or resource availability. While such an approach is well understood within the VA, external sponsors were not as familiar and assumed a more uniform approach across all sites. In response, some VAMCs established ad hoc research and development committee review procedures, allowing study teams to obtain the necessary reviews in a timely fashion. However, not all VAMCs had the infrastructure (especially when clinical personnel had been redeployed to other priorities) to respond with such agility. One critical role of the VA Central Office coordinating entities was to communicate and manage external sponsor and group expectations surrounding individual site review time lines. However, establishing policies and procedures that focus on streamlining local review processes helped to broadly mitigate the COVID-19 trial challenges.

Study Design Demands

The design of COVID-19 studies combined with the uncertainty of the pandemic required rapid protocol changes and adaptations that were often difficult to deliver. The multinetwork trials that the VA collaborated on were platform or master protocol designs. These designs emphasized overall goals (eg, treating patients requiring intensive care unit care). However, because this trial strategy also introduces complexities that may impact review and execution among those unfamiliar with it, there is a need for increased discussion and understanding of this methodology.8 For example, there can be shared control groups, reliance on specific criteria for halting because of safety or futility concerns, or continuation and expansion applied through an external review board. Delays may arise when changes to study protocols occur rapidly or frequently and necessitate new regulatory reviews, negotiation of new agreements, modifications to contracts, changes to entry criteria, etc.

While the VA has adopted a quality by design framework, VA investigators noted many missed opportunities related to looking at outcomes with new diagnostics, studies of serology, outcomes related to vaccinations, and understanding the natural history of disease in these trials.9 The limited opportunities for investigator input suggested that the advantages offered by platform designs were not maximized during pandemic-focused urgencies. It was unclear whether this barrier was created by a general lack of awareness by sponsors or a lack of opportunities. At the very least, quality by design approaches may help avoid redundancies in documentation or study processes at the central and site levels.

Contracting and Budgeting

Given external sponsorship of COVID-19 trials, efficient contracting and budgeting were critical for a rapid start up. The variability of processes associated with these trials created several challenges that were compounded by issues, such as site sub-agreements and budget documents that did not always go to the correct groups and individuals. Furthermore, the VA’s ability to use contracted resources (eg, tents, trailers, personnel) that external sponsors had built into their contracts was more difficult for VA as a federal agency governed by other statues and policies. This also put VAMCs at a disadvantage from a timing perspective, as the VA often required additional time to find equivalent solutions that met federal regulations.

Although the VA was able to establish contract solutions to some issues, time was still lost while working to secure initial funding. Additionally, for needs such as home phlebotomy—commended for convenience to veterans and research staff—and engaging a specialized research team in the Office of General Counsel, early awareness of protocol needs and sponsor solutions could allow VA to pursue alternatives sooner.

Central-Level Systems and Processes

Not all challenges were at the VAMC level. As the ORD explored solutions, it learned that various tools and study platforms were available but not considered. Applications, such as eConsent, and file-sharing platforms that met existing information security and privacy requirements were needed but had to comply with the Privacy Act of 1974, Federal Information Security Modernization Act, and other requirements. Using sponsor-provided devices, such as drug temperature monitoring equipment, required additional review to ensure that they met system requirements for a national health care system. In addition, the VA uses a clinical trials management review system; however, its implementation was new at the time these trials began. Furthermore, the system engaged with some commercial IRBs but not all. This resulted in additional delays as VAMCs and central resources worked to familiarize themselves with the system and procedures.

The ability to work collaboratively across the VA includes having a framework in which key startup processes are standardized. This allows for efficiency and minimizes variability. Also, all stakeholders should understand the importance of holding discussions to identify appropriate solutions, guidance, and instruction. Finally, the VA must strive to be more nimble when adapting technological, regulatory, and financial processes.

Internal and External Communication

The value of communication—both internal and external—cannot be understated. Minimizing confusion, managing expectations, and ensuring consistent messaging were essential for rapid trial execution. Despite being the second largest federal agency, the VA did not have a seat at the study leadership table for several protocols. When it joined later, several study aspects were set and/or difficult to revise. Challenges affecting time and securing resources have been noted. The ability to plan and then share expectations and responsibilities across and within the respective participating organizations early in the process was perhaps the single factor that was most addressable. The VA enterprise organization and integration with other units could accentuate key communications that would be essential in time-sensitive activities.

VA as a Partner for Future Research

Before the pandemic, the VA had already undertaken a path to enhance its ability to partner as part of the national biomedical research enterprise. The need for COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine trials accelerated opportunities to plan and develop processes and capabilities to advance this path. As a key strength for VA scientific activities, clinical trials represent a primary medium by which to develop its partnerships. Learning and development have become part of a culture that expedites opportunities for veterans who actively seek ways to contribute to medical knowledge and treatments for their peers and the nation.

CONCLUSIONS

Challenges associated with rapid startup and completion of clinical trials have been discussed for some time. During the pandemic, needs and barriers were magnified because of the heightened urgency for evidence-based therapeutics and vaccines. While the VA faced similar problems as well as those specific to it as a health care system, it had the opportunity to learn and more systematically implement solutions to help in its partnered efforts.10 As an enterprise, the VA hopes to apply lessons learned, strategies, and best practices to further its goals to enhance veteran access to clinical trials and respond to any future need to quickly establish evidence bases in pandemics and other health emergencies that warrant the rapid implementation of research.

Acknowledgments

The activities reported here were supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), through its Office of Research and Development (ORD), supports an extensive and experienced clinical research enterprise, including the first multisite trials in the US.1 These resources contribute to the ORD support for the largest US integrated health care system, with a primary focus on the care and well-being of veterans. While the history of VA research has facilitated the creation of an experienced and organized research enterprise, the COVID-19 pandemic challenged VA to contribute even more significantly. These challenges became pronounced given the urgency associated with standing up VA sites for both therapeutic and vaccine trials.

VA Clinical Research Enterprise

The VA recognized an early need for an organized research response not only to address operational challenges resulting from COVID-19 but also ensure that the agency would be ready to support new scientific efforts focused specifically on the virus and related outcomes.2 As a result, the ORD took decisive action first by establishing itself as a central headquarters for VA COVID-19 research activities, and second, by leveraging existing resources, initiatives, and infrastructure to develop new mechanisms that would ensure that the VA was well positioned to develop or participate in research endeavors being driven by the VA as well federal, industry, and non-VA partners.

Prior to the pandemic, the ORD, through its Cooperative Studies Program (CSP), had strategies to address challenges associated with clinical trial startup and improved efficient conduct.3 For example, the VA Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES) is a consortium of 23 VA medical centers (VAMCs) dedicated to rapid startup and recruitment into VA-sponsored clinical trials. NODES provides site-level expertise on clinical trial management, including troubleshooting challenges that may occur during clinical research execution.4 Another initiative, Access to Clinical Trials (ACT) for Veterans, engaged industry, academic, patient advocacy, and other partners to identify potential regulatory and operational hurdles to efficient startup activities specific to externally sponsored multisite clinical trials. Under ACT for Veterans, stakeholders emphasized the importance of developing a single VA point of contact for external partners to work with to more efficiently understand and navigate the VA system. In turn, such a resource could be designed to facilitate substantive research and long-term relationships with compatible external partners. Targeted to launch in April 2020, the Partnered Research Program (PRP) was expedited to respond to the pandemic.

During the pandemic, new VA efforts included the creation of the VA CoronavirUs Research and Efficacy Studies (VA CURES) network, initially established as a clinical trial master protocol framework to support and maximize VA-funded COVID-19 trial efficiency.5 VA CURES joined the consortium of trials networks funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. It began treatment trials under Accelerating COVID-19 Therapeutic Interventions and Vaccination (ACTIV), specifically ACTIV-4. The VA also partnered with the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) by organizing the VA International Coordinating Center (VA ICC) for other ACTIV trials (ACTIV-2 and -3). When approached to startup studies that included veterans and the VA health care system, these capabilities comprised the VA research response.

A Need for a New Approach

As the impact of the pandemic expanded and the need for effective treatments and vaccines grew, national calls were made to assess the capabilities and readiness of available clinical trials networks. Additionally, the US Department of Health and Human Services Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, ACTIV, NIAID Division of Clinical Research and Division of AIDS, and many pharmaceutical companies were starting to roll out trials of new therapeutics and vaccines. These groups approached the VA to help evaluate the safety and efficacy of several therapeutics and vaccines because they recognized several advantages of the VA enterprise, including its position as the nation’s largest integrated health care system, its diverse patient population, and its expertise in conducting clinical trials.

Although the VA was well positioned as an important player in a collaborative investigational approach to COVID-19 research, these trials required startup approaches that were significantly different from those it had employed in traditional, prepandemic, clinical research. Despite the VA being a single federal agency, each VAMC conducting research establishes its own practices to address both operational and regulatory requirements. This structure results in individual units that operate under different standard operating procedures. Efforts must be taken centrally to organize them into a singular network for the entire health care system. During a national crisis, when there was a need for rapid trial startup to answer safety and efficacy questions and participate under a common approach to protocol execution, this variability was neither manageable nor acceptable. Additionally, the intense resource demands associated with such research, coupled with frequent reporting requirements by VA leaders, Congress, and the White House, required that VAMCs function more like a single unit. Therefore, the ORD needed to develop VAMCs’ abilities to work collectively toward a common goal, share knowledge and experience, and capitalize on potential efficiencies concerning legal, regulatory, and operational processes.

Beginning August 2020, 39 VAMCs joined 7 large-scale collaborative COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine trials. Through its COVID-19 Research Response Team, the ORD identified, engaged, and directed appropriate resources to support the VAMC under a centralized framework for study management (Table). Centralized management not only afforded VAMCs the opportunity to work more collectively and efficiently but also provided an important advantage by enabling the VA to collect and organize its experiences (and on occasion data) to provide a base for continual learning and improvement efforts. While others have described efforts undertaken across networks to advance learning health systems, the VA’s national scope and integration of research and clinical care allow greater opportunities to learn in a practical setting.6

Challenges and Best Practices

Using surveys, webinars, interviews, and observation from site and VA Central Office personnel, the ORD identified specific variables that prevented the VAMCs from quickly starting up as a clinical trial site. We also documented strategies, solutions, and recommendations for improving startup time lines. These were organized into 8 categories: (1) site infrastructure needs and capabilities; (2) study management roles and responsibilities; (3) educational resources and training; (4) local review requirements and procedures; (5) study design demands; (6) contracting and budgeting; (7) central-level systems and processes; and (8) communication between external partners and within the VA.

Site Infrastructure Needs and Capabilities

A primary impediment to rapid study startup was a lack of basic infrastructure, including staff, space, and the agility necessary for the changing demands of high-priority, high-enrolling trials. This observation is not unique to the VA.7 Initially, certain facilities located in hot spots where COVID-19 was more prevalent became high-interest targets for study placement, despite varying degrees of available research infrastructure. Furthermore, pandemic shutdowns and quarantines permitted fewer employees onsite. This resulted in inadequate staffing in personnel needed to support required startup activities and those needed to handle the high volume of study participants who were being recruited, screened, enrolled, and followed. Additionally, as clinical care needs and infection control practices were prioritized, clinical research space was often appropriated for these needs, making it difficult to find the space to conduct trials. Lastly, supply chain issues also posed unique challenges, sometimes making it difficult for participating VAMCs to obtain needed materials, such as IV solution bags of specific sizes and contents, safety injection needles, and IV line filters.

The VA was able to use central purchasing/contracting at coordinating centers or the VA Central Office to support investigators and assist with finding supplies and clinical research space. VAMCs with research operating budgets to cover startup costs were better positioned to handle funding delays. During the pandemic, the ORD further contracted to supply administrative support to research offices to address regulatory and other requirements needed for startup activities. The ability to expand such central contracts to procure clinical research staff and outpatient clinical research space may also prove useful in meeting key needs at a site.

Management Roles and Responsibilities

Ambiguous and variable roles and responsibilities among the various partners and stakeholders represented a challenge given the large-scale, national, or international operations involved in the trials. VA attempts to operate uniformly were further limited given that each sponsor or group had preferred methods for operating and/or organizing work under urgent time lines. For example, one trial involved a coordinating center, a contract research organization, and federal partners that each worked with individual sites. Consequently, VA study teams would receive messages that were conflicting or unclear.

The VA learned that studies need a single “source of truth” and/or central command structure in times of urgency. To mitigate conflicting messages, vaccine trials relied on a clearinghouse through the PRP to interpret requirements or work on behalf of all sites before key actions were taken. For studies with the NIAID, the VA relied on experienced staff at the CSP coordinating center at the Perry Point, Maryland, VAMC before beginning. This approach especially helped with the challenges of understaffing and sites’ lack of familiarity with complex platform trial designs and already-established network practices within the ACTIV-2 and ACTIV-3 studies.

Educational Resources and Training

Since VA participation in externally sponsored, multisite clinical trials traditionally relies on an individual VAMC study team and its local resources, transitioning to centralized approaches for COVID-19 multisite studies created barriers. Many VAMCs were unfamiliar with newer capabilities for more rapid regulatory reviews and approvals involving commercial institutional review boards (IRBs) and central VA information security and privacy reviews. While tools and resources were available to facilitate these processes, real-time use had not been fully tested. As a result, everyone had to learn as they went along.

The simultaneous establishment of workflows required the ORD to centralize operations and provide training and guidance to field personnel. Although many principal investigators and clinical research coordinators had trial experience, training required unlearning previous understandings of requirements to meet urgent time lines. ORD enterprise road maps, central tools, and training materials also were made available on a study-by-study basis. Open communication was vital to train on central study materials while opportunities to discuss, question, and share experiences and ideas were promoted. The ORD also sent regular emails to prepare for upcoming work and/or raise awareness of identified challenges.

Local Review Requirements/Procedures

The clinical trials were impacted by varying VAMC review requirements and approval processes. Although VA policy defines standard requirements, the timing and procedures are left to the individual facility to determine any local factors to accommodate and/or resource availability. While such an approach is well understood within the VA, external sponsors were not as familiar and assumed a more uniform approach across all sites. In response, some VAMCs established ad hoc research and development committee review procedures, allowing study teams to obtain the necessary reviews in a timely fashion. However, not all VAMCs had the infrastructure (especially when clinical personnel had been redeployed to other priorities) to respond with such agility. One critical role of the VA Central Office coordinating entities was to communicate and manage external sponsor and group expectations surrounding individual site review time lines. However, establishing policies and procedures that focus on streamlining local review processes helped to broadly mitigate the COVID-19 trial challenges.

Study Design Demands

The design of COVID-19 studies combined with the uncertainty of the pandemic required rapid protocol changes and adaptations that were often difficult to deliver. The multinetwork trials that the VA collaborated on were platform or master protocol designs. These designs emphasized overall goals (eg, treating patients requiring intensive care unit care). However, because this trial strategy also introduces complexities that may impact review and execution among those unfamiliar with it, there is a need for increased discussion and understanding of this methodology.8 For example, there can be shared control groups, reliance on specific criteria for halting because of safety or futility concerns, or continuation and expansion applied through an external review board. Delays may arise when changes to study protocols occur rapidly or frequently and necessitate new regulatory reviews, negotiation of new agreements, modifications to contracts, changes to entry criteria, etc.

While the VA has adopted a quality by design framework, VA investigators noted many missed opportunities related to looking at outcomes with new diagnostics, studies of serology, outcomes related to vaccinations, and understanding the natural history of disease in these trials.9 The limited opportunities for investigator input suggested that the advantages offered by platform designs were not maximized during pandemic-focused urgencies. It was unclear whether this barrier was created by a general lack of awareness by sponsors or a lack of opportunities. At the very least, quality by design approaches may help avoid redundancies in documentation or study processes at the central and site levels.

Contracting and Budgeting

Given external sponsorship of COVID-19 trials, efficient contracting and budgeting were critical for a rapid start up. The variability of processes associated with these trials created several challenges that were compounded by issues, such as site sub-agreements and budget documents that did not always go to the correct groups and individuals. Furthermore, the VA’s ability to use contracted resources (eg, tents, trailers, personnel) that external sponsors had built into their contracts was more difficult for VA as a federal agency governed by other statues and policies. This also put VAMCs at a disadvantage from a timing perspective, as the VA often required additional time to find equivalent solutions that met federal regulations.

Although the VA was able to establish contract solutions to some issues, time was still lost while working to secure initial funding. Additionally, for needs such as home phlebotomy—commended for convenience to veterans and research staff—and engaging a specialized research team in the Office of General Counsel, early awareness of protocol needs and sponsor solutions could allow VA to pursue alternatives sooner.

Central-Level Systems and Processes

Not all challenges were at the VAMC level. As the ORD explored solutions, it learned that various tools and study platforms were available but not considered. Applications, such as eConsent, and file-sharing platforms that met existing information security and privacy requirements were needed but had to comply with the Privacy Act of 1974, Federal Information Security Modernization Act, and other requirements. Using sponsor-provided devices, such as drug temperature monitoring equipment, required additional review to ensure that they met system requirements for a national health care system. In addition, the VA uses a clinical trials management review system; however, its implementation was new at the time these trials began. Furthermore, the system engaged with some commercial IRBs but not all. This resulted in additional delays as VAMCs and central resources worked to familiarize themselves with the system and procedures.

The ability to work collaboratively across the VA includes having a framework in which key startup processes are standardized. This allows for efficiency and minimizes variability. Also, all stakeholders should understand the importance of holding discussions to identify appropriate solutions, guidance, and instruction. Finally, the VA must strive to be more nimble when adapting technological, regulatory, and financial processes.

Internal and External Communication

The value of communication—both internal and external—cannot be understated. Minimizing confusion, managing expectations, and ensuring consistent messaging were essential for rapid trial execution. Despite being the second largest federal agency, the VA did not have a seat at the study leadership table for several protocols. When it joined later, several study aspects were set and/or difficult to revise. Challenges affecting time and securing resources have been noted. The ability to plan and then share expectations and responsibilities across and within the respective participating organizations early in the process was perhaps the single factor that was most addressable. The VA enterprise organization and integration with other units could accentuate key communications that would be essential in time-sensitive activities.

VA as a Partner for Future Research

Before the pandemic, the VA had already undertaken a path to enhance its ability to partner as part of the national biomedical research enterprise. The need for COVID-19 therapeutic and vaccine trials accelerated opportunities to plan and develop processes and capabilities to advance this path. As a key strength for VA scientific activities, clinical trials represent a primary medium by which to develop its partnerships. Learning and development have become part of a culture that expedites opportunities for veterans who actively seek ways to contribute to medical knowledge and treatments for their peers and the nation.

CONCLUSIONS

Challenges associated with rapid startup and completion of clinical trials have been discussed for some time. During the pandemic, needs and barriers were magnified because of the heightened urgency for evidence-based therapeutics and vaccines. While the VA faced similar problems as well as those specific to it as a health care system, it had the opportunity to learn and more systematically implement solutions to help in its partnered efforts.10 As an enterprise, the VA hopes to apply lessons learned, strategies, and best practices to further its goals to enhance veteran access to clinical trials and respond to any future need to quickly establish evidence bases in pandemics and other health emergencies that warrant the rapid implementation of research.

Acknowledgments

The activities reported here were supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Research and Development.

1. Hays MT; US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development. A historical look at the establishment of the Department of Veterans Affairs Research & Development Program. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/ORD-85yrHistory.pdf

2. Garcia AP, Huang GD, Arnheim L, Ramoni R, Clancy C. The VA research enterprise: a platform for national partnerships toward evidence building and scientific innovation. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 5):S12-S17. doi:10.12788/fp.0425

3. Johnston SC, Lewis-Hall F, Bajpai A, et al. It’s time to harmonize clinical trial site standards. NAM Perspectives. October 9, 2017. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Its-Time-to-Harmonize-Clinical-Trial-Site-1.pdf

4. Condon DL, Beck D, Kenworthy-Heinige T, et al. A cross-cutting approach to enhancing clinical trial site success: the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES) model. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;6:78-84. Published 2017 Mar 29. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2017.03.006

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Master protocols: efficient clinical trial design strategies to expedite development of oncology drugs and biologics guidance for industry. March 2022. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/master-protocols-efficient-clinical-trial-design-strategies-expedite-development-oncology-drugs-and

6. IOM Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Care; Institute of Medicine. Continuous learning and improvement in health care. In: Integrating Research and Practice: Health System Leaders Working Toward High-Value Care: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press (US); 2015:chap 2. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK284654 7. Institute of Medicine (US). Building an infrastructure to support clinical trials. In: Envisioning a Transformed Clinical Trials Enterprise in the United States. National Academies Press (US); 2012:chap 5. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114656

8. Park JJH, Harari O, Dron L, Lester RT, Thorlund K, Mills EJ. An overview of platform trials with a checklist for clinical readers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;125:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.04.025

9. Meeker-O’Connell A, Glessner C, Behm M, et al. Enhancing clinical evidence by proactively building quality into clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2016;13(4):439-444. doi:10.1177/1740774516643491

10. McClure J, Asghar A, Krajec A, et al. Clinical trial facilitators: a novel approach to support the execution of clinical research at the study site level. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023;33:101106. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101106

1. Hays MT; US Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development. A historical look at the establishment of the Department of Veterans Affairs Research & Development Program. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.research.va.gov/pubs/docs/ORD-85yrHistory.pdf

2. Garcia AP, Huang GD, Arnheim L, Ramoni R, Clancy C. The VA research enterprise: a platform for national partnerships toward evidence building and scientific innovation. Fed Pract. 2023;40(suppl 5):S12-S17. doi:10.12788/fp.0425

3. Johnston SC, Lewis-Hall F, Bajpai A, et al. It’s time to harmonize clinical trial site standards. NAM Perspectives. October 9, 2017. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Its-Time-to-Harmonize-Clinical-Trial-Site-1.pdf

4. Condon DL, Beck D, Kenworthy-Heinige T, et al. A cross-cutting approach to enhancing clinical trial site success: the Department of Veterans Affairs’ Network of Dedicated Enrollment Sites (NODES) model. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2017;6:78-84. Published 2017 Mar 29. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2017.03.006

5. US Food and Drug Administration. Master protocols: efficient clinical trial design strategies to expedite development of oncology drugs and biologics guidance for industry. March 2022. Accessed August 23, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/master-protocols-efficient-clinical-trial-design-strategies-expedite-development-oncology-drugs-and

6. IOM Roundtable on Value & Science-Driven Care; Institute of Medicine. Continuous learning and improvement in health care. In: Integrating Research and Practice: Health System Leaders Working Toward High-Value Care: Workshop Summary. National Academies Press (US); 2015:chap 2. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK284654 7. Institute of Medicine (US). Building an infrastructure to support clinical trials. In: Envisioning a Transformed Clinical Trials Enterprise in the United States. National Academies Press (US); 2012:chap 5. Accessed August 28, 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK114656

8. Park JJH, Harari O, Dron L, Lester RT, Thorlund K, Mills EJ. An overview of platform trials with a checklist for clinical readers. J Clin Epidemiol. 2020;125:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.04.025

9. Meeker-O’Connell A, Glessner C, Behm M, et al. Enhancing clinical evidence by proactively building quality into clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2016;13(4):439-444. doi:10.1177/1740774516643491

10. McClure J, Asghar A, Krajec A, et al. Clinical trial facilitators: a novel approach to support the execution of clinical research at the study site level. Contemp Clin Trials Commun. 2023;33:101106. doi:10.1016/j.conctc.2023.101106

The VA Research Enterprise: A Platform for National Partnerships Toward Evidence Building and Scientific Innovation

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) plays a substantial role in the nation’s public health through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Its statutory missions of teaching, clinical care, and research enable it to serve a foundational role in the US biomedical enterprise.1 Throughout its extensive network of VA medical centers (VAMCs) and partnering academic affiliates, thousands of clinicians and researchers have been trained to improve the lives of veterans and benefit the lives of all Americans. In supporting the largest US integrated health care system, the VA also has numerous capabilities and resources that distinctively position it to produce scientific and clinical results specifically within the context of providing care. The VA has formed partnerships with other federal agencies, industry, and nonprofit entities. Its ability to be a nexus of health care and practice, scientific discovery, and innovative ways to integrate shared interests in these areas have led to many transformative endeavors that save lives and improve the quality of care for veterans and the public.

The COVID-19 pandemic triggered another mission: service in times of national emergency. Known as the Fourth Mission, the VA rapidly shifted to highlight how its health care and research enterprises could apply strengths in a unique, coordinated manner. While the Fourth Mission is typically considered in the context of clinical care, the VA’s movement toward greater integration facilitated the role of research as a key component in efforts under a learning health care model.2

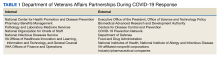

VA Office of Research and Development

Within the VHA, the Office of Research and Development (ORD) develops research policy and oversees interdisciplinary efforts focused on generating evidence to improve veteran health.3 These activities span at least 100 of 171 VAMCs and include thousands of investigators and staff across all major health research disciplines. Many of these investigators are also clinicians who provide patient care and are experts in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of diseases and disorders affecting veterans.

The ORD has invested in a range of scientific, operational, regulatory, and technological assets and infrastructure as part of its enterprise. These strengths come from a nearly 100-year history originating as part of a set of hospital-based medical studies. This established the model for a culture of cooperative research within the VA and with external groups who benefit from the VA’s foundational role in multisite clinical trials.2,4,5 Today, the VA prioritizes bench-to-bedside research covering a broad spectrum of investigations, which are integrated with clinical operations and systems that deliver care.3 The VA supports an extensive range of work that covers core areas in preclinical and clinical studies to health services research, rehabilitation and implementation science, establishing expertise in genomic and data sciences, and more recent activities in artificial intelligence.

In 2017, the ORD began a focused strategy to transform into a national enterprise that capitalized on its place within the VA and its particular ability to translate and implement scientific findings into real impact for veteran health and care through 5 initiatives: (1) enhancing veteran access to high-quality clinical trials; (2) increasing the substantial real-world impact of VA Research; (3) putting VA data to work for veteran health; (4) promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion within our sphere of influence; and (5) building community through research. These activities are interrelated and, where possible, the ORD works with other VA clinical and operational offices to accomplish multiple goals and coordinate within the health care system. As such, the VA continually seeks to increase efficiencies and improve abilities that provide veterans with best-in-class health care. While still in its early stages, this strategy and its initiatives established a path for the ORD response to the pandemic.

Within 2 weeks of the World Health Organization and the US declaring a COVID-19 pandemic, the ORD began to address the developing needs and challenges of the yet unknown emerging public health threat. This included outreach to and contact from federal, academic, and industry partners. At the same time, the ORD maintained its focus and energy to support its ongoing veteran-centric research portfolio and VHA health care system needs across its broad scope of activities.

This article discusses how the pandemic accelerated the VA’s research enterprise strategy and enacted a response, highlighting the advantages and strengths of this direction. We demonstrate how this evolving strategy enabled the VA to quickly leverage partnerships during a health emergency. While the ORD and VA Research have been used interchangeably, we will attempt to distinguish between the office that serves as headquarters for the national enterprise—the ORD—and the components of that enterprise composed of scientific personnel, equipment, operational units, and partners—VA Research. Finally, we present lessons from this experience toward a broader, post–COVID-19, enterprise-wide approach that the VA has for providing evidence-based care. These experiences may enrich our understanding of postpandemic future research opportunities with the VA as a leader and partner who leverages its commitment to veterans to improve the nation’s health.

ORGANIZING THE VA COVID-19 RESEARCH RESPONSE

VA Research seeks to internally standardize and integrate collaborations with clinical and operational partners throughout the agency. When possible, it seeks to streamline partnership efforts involving external groups less familiar with how the VA operates or its policies, as well as its capabilities. This need was more obvious during the pandemic, and the ORD assembled its COVID-19 response quickly.6

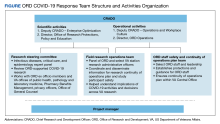

In early January 2020, VA offices, including the ORD, were carefully observing COVID-19. On March 4, 2020, a week before the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a pandemic, the ORD and its National Research Advisory Council arranged a briefing from VA public health leaders to deal with reported cases of COVID-19 and VA plans. Immediately afterward, the ORD Chief Research and Development Officer gathered a team of experts in clinical research, infectious disease, and public health to strategize a broader research enterprise approach to the pandemic. This group quickly framed 3 key targets: (1) identify critical research questions to prioritize; (2) provide operational guidance to the research community; and (3) uphold VA research staff safety. This discussion led to the creation of a larger ORD COVID-19 Research Response Team that managed activities within this scope. This team included other ORD leaders and staff with operational, scientific, and regulatory expertise charged with enterprise-level planning and execution for all research activities addressing or affected by the pandemic (Figure).

Effective and timely communication was chief among key ORD responsibilities. On March 19, 2020, the Response Team informed the VA Research community about ORD plans for organizing the VA COVID-19 research response.7 It also mobilized VA research programs and investigators to support an enterprise approach that would be coordinated centrally. We achieved communication goals by developing a dedicated website, which provided a means to distribute up-to-date notices and guidance, answer frequently asked questions, and alert investigators about research opportunities. The site enabled the field to report on its efforts, which enhanced leadership and community awareness. A working group of ORD and field personnel managed communications. Given the volume of existing non–COVID-19 research, we established a research continuity of operations plan to provide guidelines for study participant and research staff safety. The ORD issued an unprecedented full-stop administrative hold on in-person research activities after the global announcement of the pandemic. This policy provided formal protections for research programs to safeguard staff and research participants and to determine appropriate alternatives to conduct research activities within necessary social distancing, safety, and other clinical care parameters. It also aligned with guidance and requirements that local VAMCs issued for their operations and care priorities.

The Response Team also established a scientific steering committee of VA infectious disease, critical care, informatics, and epidemiology experts to prioritize research questions, identify research opportunities, and evaluate proposals using a modified expeditious scientific review process. This group also minimized duplicate scientific efforts that might be expected from a large pool of investigators simultaneously pursuing similar research questions. Committee recommendations set up a portfolio that included basic science efforts in diagnostics, clinical trials, population studies, and research infrastructure.

Leveraging Existing Infrastructure

Besides quickly organizing a central touchpoint for the VA COVID-19 research response, the ORD capitalized on its extensive nationwide infrastructure. One key component was the Cooperative Studies Program (CSP); the longstanding VA clinical research enterprise that supports the planning and conduct of large multicenter clinical trials and epidemiological studies. The CSP includes experts at 5 data and statistical coordinating centers, a clinical research pharmacy coordinating center, and 4 epidemiological resource centers.8 CSP studies provide definitive evidence for clinical practice and care of veterans and the nation. CSP’s CONFIRM trial (CSP 577) is the largest VA interventional study with > 50,000 veterans.9 CONFIRM followed the Trial of Varicella Zoster Vaccine for the Prevention of Herpes Zoster and Its Complications (CSP 403), which involved > 38,000 participants to evaluate a vaccine to reduce the burden of illness-associated herpes zoster (shingles). In the study, the vaccine markedly reduced the shingles burden of illness among older adults.10 These studies highlight the CSP cohort development ability as evidenced by the Million Veteran Program.11

VA Research, particularly through the CSP, contributed to multiple federal actions for COVID-19. The CSP had already established partnerships with federal and industry groups in multisite clinical trials and observational studies. During COVID-19, the ORD established a COVID-19 clinical trial master protocol framework: the VA CoronavirUs Research & Efficacy Studies network.9 The CSP also supported studies by the Coronavirus Prevention Network, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID), and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). As such, the VA could translate requirements in working with an industry sponsor on the rapid execution of studies within a federal health care system. Much of the success arose when there was either earlier engagement in planning and/or existing familiarity among parties with operational and regulatory requirements.