User login

Here on Earth

We live inundated with promises that technology will solve our most challenging problems, yet we are regularly disappointed when it does not. New technological solutions seem to appear daily, and we feel like we are falling behind if we do not jump to join the people who are implementing, selling, or imposing new solutions. Often these solutions are offered before the problem is even fully understood, and no assessment has been made to determine if the solution actually helps to solve the challenge identified. With 80% of us now having transitioned to EHRs, we know full well their benefits as well as their pitfalls. While we have mostly accommodated to electronic documentation, we are now at the point where we are beginning to explore some of the most exciting potential benefits of our EHRs – population health, enhanced data on medication adherence, and improved patient communication. As we look at this next stage of growth, we are reminded of a lesson from an old joke:

A rabbi dies and goes to heaven. When he gets there he is given an old robe and a wooden walking stick and is told to get in line to the entrance to heaven. While the rabbi waits in the long line, a taxi driver walks up and is greeted by a group of angels blowing their horns announcing his arrival. One of the angels walks over to the driver and gives him a flowing white satin robe and a golden walking stick. Another angel then escorts him to the front of the line.

The angel turned toward him, smiled, and shook his head. “Yes, yes,” the angel replied, “We know all that. But, here in heaven we care about results, not intent. While you gave your sermons, people slept. When the cab driver drove, people prayed.”

As we look ahead to the next generation of electronic health records, there are going to be many creative ideas of how to use them to help patients improve their health and take care of their diseases. One of the more notable new technologies over the last 5 years is the development of wearable health devices. Innovations like the Apple Watch, Fitbit, and other wearables allow us to track our activity and diet, and encourage us to behave better. They do this by providing constant feedback on how we are doing, and they offer the ability to use social groups to encourage sustained behavioral change. Some devices tell us regularly how far we have walked while others let us know when we have been sitting too long. As we input information about diet, the devices and their associated apps give us feedback on how we are adhering to our dietary goals. Some even allow data to be funneled into the EHR so that physicians can review the behavioral changes and track patient progress. The challenge that arises is that the technology itself is so fascinating and so filled with promise that it is easy to forget what is most important: ensuring it works not just to keep us engaged and busy but also to help us accomplish the real goals we have defined for its use.

Wearable technology is now the most recent and dramatic example of how the excitement over technology may be outpacing its utility. Most of us have tried (or have patients, friends and family who have tried) wearable technology solutions to track and encourage behavioral change. A recent article published in JAMA looked at more than 400 individuals randomized to a standard behavioral weight-loss intervention vs. a technology-enhanced weight loss intervention using a wearable device over 24 months. It was fairly obvious that the group with the wearable device would do better, and have improved fitness and more weight loss. It was obvious … except that is not what happened. Both groups improved equally in fitness, and the standard intervention group lost significantly more weight over 24 months than did the wearable technology group.

There are many reasons that this might have happened. It may be that the idea of this quick feedback loop is in itself flawed, or it may be that the devices and/or the dietary input is simply imprecise, causing people to think that they are doing better than they really are (and then modifying their behavior in the wrong direction). Whatever the explanation, seeing those results, I think again of the moral handed down though generations by that old joke – that here on earth we need to care less about intent and more about results.

Reference

Jakicic JM, et al. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316[11]:1161-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12858

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

We live inundated with promises that technology will solve our most challenging problems, yet we are regularly disappointed when it does not. New technological solutions seem to appear daily, and we feel like we are falling behind if we do not jump to join the people who are implementing, selling, or imposing new solutions. Often these solutions are offered before the problem is even fully understood, and no assessment has been made to determine if the solution actually helps to solve the challenge identified. With 80% of us now having transitioned to EHRs, we know full well their benefits as well as their pitfalls. While we have mostly accommodated to electronic documentation, we are now at the point where we are beginning to explore some of the most exciting potential benefits of our EHRs – population health, enhanced data on medication adherence, and improved patient communication. As we look at this next stage of growth, we are reminded of a lesson from an old joke:

A rabbi dies and goes to heaven. When he gets there he is given an old robe and a wooden walking stick and is told to get in line to the entrance to heaven. While the rabbi waits in the long line, a taxi driver walks up and is greeted by a group of angels blowing their horns announcing his arrival. One of the angels walks over to the driver and gives him a flowing white satin robe and a golden walking stick. Another angel then escorts him to the front of the line.

The angel turned toward him, smiled, and shook his head. “Yes, yes,” the angel replied, “We know all that. But, here in heaven we care about results, not intent. While you gave your sermons, people slept. When the cab driver drove, people prayed.”

As we look ahead to the next generation of electronic health records, there are going to be many creative ideas of how to use them to help patients improve their health and take care of their diseases. One of the more notable new technologies over the last 5 years is the development of wearable health devices. Innovations like the Apple Watch, Fitbit, and other wearables allow us to track our activity and diet, and encourage us to behave better. They do this by providing constant feedback on how we are doing, and they offer the ability to use social groups to encourage sustained behavioral change. Some devices tell us regularly how far we have walked while others let us know when we have been sitting too long. As we input information about diet, the devices and their associated apps give us feedback on how we are adhering to our dietary goals. Some even allow data to be funneled into the EHR so that physicians can review the behavioral changes and track patient progress. The challenge that arises is that the technology itself is so fascinating and so filled with promise that it is easy to forget what is most important: ensuring it works not just to keep us engaged and busy but also to help us accomplish the real goals we have defined for its use.

Wearable technology is now the most recent and dramatic example of how the excitement over technology may be outpacing its utility. Most of us have tried (or have patients, friends and family who have tried) wearable technology solutions to track and encourage behavioral change. A recent article published in JAMA looked at more than 400 individuals randomized to a standard behavioral weight-loss intervention vs. a technology-enhanced weight loss intervention using a wearable device over 24 months. It was fairly obvious that the group with the wearable device would do better, and have improved fitness and more weight loss. It was obvious … except that is not what happened. Both groups improved equally in fitness, and the standard intervention group lost significantly more weight over 24 months than did the wearable technology group.

There are many reasons that this might have happened. It may be that the idea of this quick feedback loop is in itself flawed, or it may be that the devices and/or the dietary input is simply imprecise, causing people to think that they are doing better than they really are (and then modifying their behavior in the wrong direction). Whatever the explanation, seeing those results, I think again of the moral handed down though generations by that old joke – that here on earth we need to care less about intent and more about results.

Reference

Jakicic JM, et al. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316[11]:1161-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12858

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

We live inundated with promises that technology will solve our most challenging problems, yet we are regularly disappointed when it does not. New technological solutions seem to appear daily, and we feel like we are falling behind if we do not jump to join the people who are implementing, selling, or imposing new solutions. Often these solutions are offered before the problem is even fully understood, and no assessment has been made to determine if the solution actually helps to solve the challenge identified. With 80% of us now having transitioned to EHRs, we know full well their benefits as well as their pitfalls. While we have mostly accommodated to electronic documentation, we are now at the point where we are beginning to explore some of the most exciting potential benefits of our EHRs – population health, enhanced data on medication adherence, and improved patient communication. As we look at this next stage of growth, we are reminded of a lesson from an old joke:

A rabbi dies and goes to heaven. When he gets there he is given an old robe and a wooden walking stick and is told to get in line to the entrance to heaven. While the rabbi waits in the long line, a taxi driver walks up and is greeted by a group of angels blowing their horns announcing his arrival. One of the angels walks over to the driver and gives him a flowing white satin robe and a golden walking stick. Another angel then escorts him to the front of the line.

The angel turned toward him, smiled, and shook his head. “Yes, yes,” the angel replied, “We know all that. But, here in heaven we care about results, not intent. While you gave your sermons, people slept. When the cab driver drove, people prayed.”

As we look ahead to the next generation of electronic health records, there are going to be many creative ideas of how to use them to help patients improve their health and take care of their diseases. One of the more notable new technologies over the last 5 years is the development of wearable health devices. Innovations like the Apple Watch, Fitbit, and other wearables allow us to track our activity and diet, and encourage us to behave better. They do this by providing constant feedback on how we are doing, and they offer the ability to use social groups to encourage sustained behavioral change. Some devices tell us regularly how far we have walked while others let us know when we have been sitting too long. As we input information about diet, the devices and their associated apps give us feedback on how we are adhering to our dietary goals. Some even allow data to be funneled into the EHR so that physicians can review the behavioral changes and track patient progress. The challenge that arises is that the technology itself is so fascinating and so filled with promise that it is easy to forget what is most important: ensuring it works not just to keep us engaged and busy but also to help us accomplish the real goals we have defined for its use.

Wearable technology is now the most recent and dramatic example of how the excitement over technology may be outpacing its utility. Most of us have tried (or have patients, friends and family who have tried) wearable technology solutions to track and encourage behavioral change. A recent article published in JAMA looked at more than 400 individuals randomized to a standard behavioral weight-loss intervention vs. a technology-enhanced weight loss intervention using a wearable device over 24 months. It was fairly obvious that the group with the wearable device would do better, and have improved fitness and more weight loss. It was obvious … except that is not what happened. Both groups improved equally in fitness, and the standard intervention group lost significantly more weight over 24 months than did the wearable technology group.

There are many reasons that this might have happened. It may be that the idea of this quick feedback loop is in itself flawed, or it may be that the devices and/or the dietary input is simply imprecise, causing people to think that they are doing better than they really are (and then modifying their behavior in the wrong direction). Whatever the explanation, seeing those results, I think again of the moral handed down though generations by that old joke – that here on earth we need to care less about intent and more about results.

Reference

Jakicic JM, et al. Effect of Wearable Technology Combined With a Lifestyle Intervention on Long-term Weight Loss The IDEA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2016;316[11]:1161-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.12858

Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia. Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records.

EHR Report: Take your medicine!

“Drugs don’t work in patients who don’t take them.”

–C. Everett Koop, M.D.

While it would be hard to imagine accountable care organizations being able to get the data they need to manage care without electronic health records, and EHRs are critical as payment has evolved to emphasize the outcomes of treatment, one area remains the holy grail of disease management: how to get patients to take the medications that are prescribed.

Poor adherence to medications is a critical issue in the management of chronic disease. The causes for suboptimal adherence are numerous, including the cost of medications, patient-physician communication, patient education, motivation, and simple forgetfulness.

Approximately 1.5 billion prescriptions, at a cost of more than $250 billion, are dispensed each year in the United States. A large body of evidence supports the use of these medications. For patients with diabetes, for instance, correct medication use can lower blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and by so doing, decrease morbidity and mortality from both microvascular and macrovascular disease.

The act of taking medications is influenced by many factors, and all of these factors come together at a point in time when patients are not directly engaged with the health care system. It is at that moment that patients remember and decide whether to take their medications.

Numerous studies show that individuals often do not take their medicines as prescribed. Adherence rates for medications for chronic disease show that patients on average take only about 50% of prescribed doses. For patients with diabetes, the average adherence rate is about 70%, with rates ranging in different studies from 31% to 87%.

When patients do not take their medications correctly, there can be severe consequences. Poor medication adherence can lead to poorer clinical outcomes, including increased hospitalizations. One large dataset of more than 56,000 individuals with type 2 diabetes covered by employer-sponsored health insurance showed that increased adherence to medications significantly reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits. When adherence rates increased, the hospitalization rate fell 23%, and the rate of emergency department visits decreased 46%, resulting in significant cost savings for the health system.1

In response to this issue, many strategies have emerged. We now regularly get correspondence from insurance companies alerting us to nonadherence of individual patients. This information tends to be of little benefit, because the information is received long after the decision to take or not take the medication is made. Our response in the office to our patients is generally to remind them to take their medications, which is not much different from the discussion we have with them without that information.

Recently, a new set of apps for smartphones and tablets has emerged to help patients organize their approach to taking medications. Examples of some of these apps include Care4Today, Dosecast, Medisafe, MedSimple, MyMedREc, MyMeds, and OnTimeRx. Most of these apps allow a patient to put in their medication schedule and are organized to provide reminders when it is time to take medications.

The problem with reminders, of course, is that they don’t always happen at a time when it is convenient for a person to take their medications. For example, if your app reminds you to take your medicines at 9 p.m. each night, and you are at the movies on a Saturday night, you may extinguish the reminder and not remember to take the medications when you get home.

Many of the apps also track adherence rates so that patients can see how well they are doing in taking their medications. The results are often startling to patients, and it is hoped that such information would encourage more effort in taking medications.

One problem with many of the apps currently available is that they essentially function as sophisticated alarm clocks. They do not get at some of the fundamental reasons that people do not take their medications, which would require more behavioral input.

In fact, a recent article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine looked at 166 medication adherence apps and concluded that current apps contained little in the way of evidence-based behavioral change techniques that have been shown to help change behavior. In fact, only about one-third of apps contained any feedback on behavior at all.2

While adherence apps still have a way to go, they can be helpful, and many contain interesting, novel features. Some allow the patient to input the name of a medication by scanning the name from the medication’s pill bottle. Some have the ability not only to remind a patient to take a medication, but also to text that patient’s caregiver (or parent, in the case of a teenager) if the medication is not taken.

While not perfect, these adherence apps are worth learning more about. They may be helpful additions to our efforts to achieve the best outcomes for our patients by helping them to actually take the medications that we so carefully prescribe.

References

1. Encinosa, W.E.; Bernard, D.; Dor, A. Does prescription drug adherence reduce hospitalizations and costs? The case of diabetes. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research 22, pp. 151-73, 2010 (AHRQ Publication No. 11-R008).

2. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Nov 17. pii: S0749-3797(15)00637-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.034.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

“Drugs don’t work in patients who don’t take them.”

–C. Everett Koop, M.D.

While it would be hard to imagine accountable care organizations being able to get the data they need to manage care without electronic health records, and EHRs are critical as payment has evolved to emphasize the outcomes of treatment, one area remains the holy grail of disease management: how to get patients to take the medications that are prescribed.

Poor adherence to medications is a critical issue in the management of chronic disease. The causes for suboptimal adherence are numerous, including the cost of medications, patient-physician communication, patient education, motivation, and simple forgetfulness.

Approximately 1.5 billion prescriptions, at a cost of more than $250 billion, are dispensed each year in the United States. A large body of evidence supports the use of these medications. For patients with diabetes, for instance, correct medication use can lower blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and by so doing, decrease morbidity and mortality from both microvascular and macrovascular disease.

The act of taking medications is influenced by many factors, and all of these factors come together at a point in time when patients are not directly engaged with the health care system. It is at that moment that patients remember and decide whether to take their medications.

Numerous studies show that individuals often do not take their medicines as prescribed. Adherence rates for medications for chronic disease show that patients on average take only about 50% of prescribed doses. For patients with diabetes, the average adherence rate is about 70%, with rates ranging in different studies from 31% to 87%.

When patients do not take their medications correctly, there can be severe consequences. Poor medication adherence can lead to poorer clinical outcomes, including increased hospitalizations. One large dataset of more than 56,000 individuals with type 2 diabetes covered by employer-sponsored health insurance showed that increased adherence to medications significantly reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits. When adherence rates increased, the hospitalization rate fell 23%, and the rate of emergency department visits decreased 46%, resulting in significant cost savings for the health system.1

In response to this issue, many strategies have emerged. We now regularly get correspondence from insurance companies alerting us to nonadherence of individual patients. This information tends to be of little benefit, because the information is received long after the decision to take or not take the medication is made. Our response in the office to our patients is generally to remind them to take their medications, which is not much different from the discussion we have with them without that information.

Recently, a new set of apps for smartphones and tablets has emerged to help patients organize their approach to taking medications. Examples of some of these apps include Care4Today, Dosecast, Medisafe, MedSimple, MyMedREc, MyMeds, and OnTimeRx. Most of these apps allow a patient to put in their medication schedule and are organized to provide reminders when it is time to take medications.

The problem with reminders, of course, is that they don’t always happen at a time when it is convenient for a person to take their medications. For example, if your app reminds you to take your medicines at 9 p.m. each night, and you are at the movies on a Saturday night, you may extinguish the reminder and not remember to take the medications when you get home.

Many of the apps also track adherence rates so that patients can see how well they are doing in taking their medications. The results are often startling to patients, and it is hoped that such information would encourage more effort in taking medications.

One problem with many of the apps currently available is that they essentially function as sophisticated alarm clocks. They do not get at some of the fundamental reasons that people do not take their medications, which would require more behavioral input.

In fact, a recent article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine looked at 166 medication adherence apps and concluded that current apps contained little in the way of evidence-based behavioral change techniques that have been shown to help change behavior. In fact, only about one-third of apps contained any feedback on behavior at all.2

While adherence apps still have a way to go, they can be helpful, and many contain interesting, novel features. Some allow the patient to input the name of a medication by scanning the name from the medication’s pill bottle. Some have the ability not only to remind a patient to take a medication, but also to text that patient’s caregiver (or parent, in the case of a teenager) if the medication is not taken.

While not perfect, these adherence apps are worth learning more about. They may be helpful additions to our efforts to achieve the best outcomes for our patients by helping them to actually take the medications that we so carefully prescribe.

References

1. Encinosa, W.E.; Bernard, D.; Dor, A. Does prescription drug adherence reduce hospitalizations and costs? The case of diabetes. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research 22, pp. 151-73, 2010 (AHRQ Publication No. 11-R008).

2. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Nov 17. pii: S0749-3797(15)00637-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.034.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

“Drugs don’t work in patients who don’t take them.”

–C. Everett Koop, M.D.

While it would be hard to imagine accountable care organizations being able to get the data they need to manage care without electronic health records, and EHRs are critical as payment has evolved to emphasize the outcomes of treatment, one area remains the holy grail of disease management: how to get patients to take the medications that are prescribed.

Poor adherence to medications is a critical issue in the management of chronic disease. The causes for suboptimal adherence are numerous, including the cost of medications, patient-physician communication, patient education, motivation, and simple forgetfulness.

Approximately 1.5 billion prescriptions, at a cost of more than $250 billion, are dispensed each year in the United States. A large body of evidence supports the use of these medications. For patients with diabetes, for instance, correct medication use can lower blood sugar, blood pressure, and cholesterol, and by so doing, decrease morbidity and mortality from both microvascular and macrovascular disease.

The act of taking medications is influenced by many factors, and all of these factors come together at a point in time when patients are not directly engaged with the health care system. It is at that moment that patients remember and decide whether to take their medications.

Numerous studies show that individuals often do not take their medicines as prescribed. Adherence rates for medications for chronic disease show that patients on average take only about 50% of prescribed doses. For patients with diabetes, the average adherence rate is about 70%, with rates ranging in different studies from 31% to 87%.

When patients do not take their medications correctly, there can be severe consequences. Poor medication adherence can lead to poorer clinical outcomes, including increased hospitalizations. One large dataset of more than 56,000 individuals with type 2 diabetes covered by employer-sponsored health insurance showed that increased adherence to medications significantly reduced hospitalizations and emergency department visits. When adherence rates increased, the hospitalization rate fell 23%, and the rate of emergency department visits decreased 46%, resulting in significant cost savings for the health system.1

In response to this issue, many strategies have emerged. We now regularly get correspondence from insurance companies alerting us to nonadherence of individual patients. This information tends to be of little benefit, because the information is received long after the decision to take or not take the medication is made. Our response in the office to our patients is generally to remind them to take their medications, which is not much different from the discussion we have with them without that information.

Recently, a new set of apps for smartphones and tablets has emerged to help patients organize their approach to taking medications. Examples of some of these apps include Care4Today, Dosecast, Medisafe, MedSimple, MyMedREc, MyMeds, and OnTimeRx. Most of these apps allow a patient to put in their medication schedule and are organized to provide reminders when it is time to take medications.

The problem with reminders, of course, is that they don’t always happen at a time when it is convenient for a person to take their medications. For example, if your app reminds you to take your medicines at 9 p.m. each night, and you are at the movies on a Saturday night, you may extinguish the reminder and not remember to take the medications when you get home.

Many of the apps also track adherence rates so that patients can see how well they are doing in taking their medications. The results are often startling to patients, and it is hoped that such information would encourage more effort in taking medications.

One problem with many of the apps currently available is that they essentially function as sophisticated alarm clocks. They do not get at some of the fundamental reasons that people do not take their medications, which would require more behavioral input.

In fact, a recent article in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine looked at 166 medication adherence apps and concluded that current apps contained little in the way of evidence-based behavioral change techniques that have been shown to help change behavior. In fact, only about one-third of apps contained any feedback on behavior at all.2

While adherence apps still have a way to go, they can be helpful, and many contain interesting, novel features. Some allow the patient to input the name of a medication by scanning the name from the medication’s pill bottle. Some have the ability not only to remind a patient to take a medication, but also to text that patient’s caregiver (or parent, in the case of a teenager) if the medication is not taken.

While not perfect, these adherence apps are worth learning more about. They may be helpful additions to our efforts to achieve the best outcomes for our patients by helping them to actually take the medications that we so carefully prescribe.

References

1. Encinosa, W.E.; Bernard, D.; Dor, A. Does prescription drug adherence reduce hospitalizations and costs? The case of diabetes. Advances in Health Economics and Health Services Research 22, pp. 151-73, 2010 (AHRQ Publication No. 11-R008).

2. Am J Prev Med. 2015 Nov 17. pii: S0749-3797(15)00637-6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.034.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Baby, back back back it up

As many young physicians might recognize, the title of today’s column is from a song by Prince Royce featuring Jennifer Lopez and Pitbull. This article, though, is about what we believe is likely an urgent matter for many of our readers – the issue of appropriately backing up information that resides on their personal computers. We were prompted to write about this after a colleague came to one of us in a panic after losing all of the information on her meticulously performed, but poorly conceived backup. For years she has been developing and storing her lectures on a flash drive, and every month she has been backing up her flash drive to her personal computer. She even set a reminder in her calendar to make sure that she perform those backups each and every month. Unfortunately, she lost her flash drive, and even more unfortunately discovered that what she thought were copies of files on her computer were actually only shortcuts to the files on her now-missing flash drive. All her files were gone.

We are going to organize our discussion in three parts: First, we want to convince you of the importance of making backups, essentially informational life insurance. Unlike life insurance, however, you have a pretty good chance of using your backups at some point over the next 10 years. Second, we are going to discuss locally based backups, and then lastly, we’ll cover cloud-based backups. This may seem like an incredibly dull topic to some, but we anticipate receiving emails of thanks over many years for the knowledge and actions that come out of today’s column.

Hard drive failure rates, derived from data published by companies that professionally manage large numbers of hard drives, is about 3%-5% in the first year. This remains at about 3% per year for the next 2-3 years, and then can go up to 10% or more per year as hard drives continue to age. That means that over a 4-year period, 15%-20% of hard drives are likely to fail.1,2 This fact underscores the importance of backing up your data, because there is a good chance that over time, loss of data will happen to you.

One strategy is to back up to an external drive. The drive can be either a flash drive if you have less than 128 GB to store, or a traditional external hard drive – a very affordable option for memory up to 4 TB (4,000 GB). There are many excellent external hard drives and flash drives from which to choose, but you also need to have backup software that will take the information from your personal computer and place it in an organized manner on your external drive. Many drives now come bundled with backup software. An example of such a drive is the Western Digital My Passport Elite. If the hard drive you have does not already have backup software, there are lots of good choices out there. Backup software solutions include Time Machine (built into all Mac Computers), and many software choices for PCs.3

While the speed of backup and recovery is fast – often just a few hours – there are two main issues that make external drives suboptimal as your main backup strategy. The first is that most people simply don’t remember to plug their external drive into their computer regularly; months and sometimes years can go by without backing up your files. The second issue, which is usually not considered, is that the hard drive usually sits on your desk next to your computer. Therefore, if there is a fire, a flood, an electrical surge, or even a simple spill on your desk, you may lose both your main files and your backup in one fell swoop. For this reason, if you choose to use an external drive as your backup method, you should back up to two different external drives and keep one drive in your office and one at home.

The best method of backup, and the one we recommend to everyone, eliminates the major disadvantages of local backups. This method is cloud-based backup. For cloud-based backup, you purchase a subscription with an annual fee, then you download software from the backup vendor to your computer. It usually takes about 15 minutes to set up the software by selecting the file folders that you would like to back up, then the software does the rest. The first backup can take a long time, typically a few days, as the speed of the backup is limited by the speed of your Internet connection. After that first time, though, backups don’t take long because they back up only the files that have changed since the previous backup.

The main advantages to cloud-based solutions is that once it has been set up, the software ensures that incremental backups occur automatically every time your computer is connected to the Internet. In addition, since the cloud backups are off-site, you are protected from an adverse occurrence taking out your backup drive and your computer when they are sitting next to each other on your desk. In addition, most cloud backup services also allow you to access your file from any computer or smartphone for access where and when you need the files.

So, let us end where we began, with lyrics from the music video, with which we agree, “Word of advice: Want a happy life … Back it up one more time.”

References

1. http://www.extremetech.com/computing/170748-how-long-do-hard-drives-actually-live-for

2. http://www.pcworld.com/article/131168/article.html

3. The Best Backup Software at http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2278661,00.asp

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

As many young physicians might recognize, the title of today’s column is from a song by Prince Royce featuring Jennifer Lopez and Pitbull. This article, though, is about what we believe is likely an urgent matter for many of our readers – the issue of appropriately backing up information that resides on their personal computers. We were prompted to write about this after a colleague came to one of us in a panic after losing all of the information on her meticulously performed, but poorly conceived backup. For years she has been developing and storing her lectures on a flash drive, and every month she has been backing up her flash drive to her personal computer. She even set a reminder in her calendar to make sure that she perform those backups each and every month. Unfortunately, she lost her flash drive, and even more unfortunately discovered that what she thought were copies of files on her computer were actually only shortcuts to the files on her now-missing flash drive. All her files were gone.

We are going to organize our discussion in three parts: First, we want to convince you of the importance of making backups, essentially informational life insurance. Unlike life insurance, however, you have a pretty good chance of using your backups at some point over the next 10 years. Second, we are going to discuss locally based backups, and then lastly, we’ll cover cloud-based backups. This may seem like an incredibly dull topic to some, but we anticipate receiving emails of thanks over many years for the knowledge and actions that come out of today’s column.

Hard drive failure rates, derived from data published by companies that professionally manage large numbers of hard drives, is about 3%-5% in the first year. This remains at about 3% per year for the next 2-3 years, and then can go up to 10% or more per year as hard drives continue to age. That means that over a 4-year period, 15%-20% of hard drives are likely to fail.1,2 This fact underscores the importance of backing up your data, because there is a good chance that over time, loss of data will happen to you.

One strategy is to back up to an external drive. The drive can be either a flash drive if you have less than 128 GB to store, or a traditional external hard drive – a very affordable option for memory up to 4 TB (4,000 GB). There are many excellent external hard drives and flash drives from which to choose, but you also need to have backup software that will take the information from your personal computer and place it in an organized manner on your external drive. Many drives now come bundled with backup software. An example of such a drive is the Western Digital My Passport Elite. If the hard drive you have does not already have backup software, there are lots of good choices out there. Backup software solutions include Time Machine (built into all Mac Computers), and many software choices for PCs.3

While the speed of backup and recovery is fast – often just a few hours – there are two main issues that make external drives suboptimal as your main backup strategy. The first is that most people simply don’t remember to plug their external drive into their computer regularly; months and sometimes years can go by without backing up your files. The second issue, which is usually not considered, is that the hard drive usually sits on your desk next to your computer. Therefore, if there is a fire, a flood, an electrical surge, or even a simple spill on your desk, you may lose both your main files and your backup in one fell swoop. For this reason, if you choose to use an external drive as your backup method, you should back up to two different external drives and keep one drive in your office and one at home.

The best method of backup, and the one we recommend to everyone, eliminates the major disadvantages of local backups. This method is cloud-based backup. For cloud-based backup, you purchase a subscription with an annual fee, then you download software from the backup vendor to your computer. It usually takes about 15 minutes to set up the software by selecting the file folders that you would like to back up, then the software does the rest. The first backup can take a long time, typically a few days, as the speed of the backup is limited by the speed of your Internet connection. After that first time, though, backups don’t take long because they back up only the files that have changed since the previous backup.

The main advantages to cloud-based solutions is that once it has been set up, the software ensures that incremental backups occur automatically every time your computer is connected to the Internet. In addition, since the cloud backups are off-site, you are protected from an adverse occurrence taking out your backup drive and your computer when they are sitting next to each other on your desk. In addition, most cloud backup services also allow you to access your file from any computer or smartphone for access where and when you need the files.

So, let us end where we began, with lyrics from the music video, with which we agree, “Word of advice: Want a happy life … Back it up one more time.”

References

1. http://www.extremetech.com/computing/170748-how-long-do-hard-drives-actually-live-for

2. http://www.pcworld.com/article/131168/article.html

3. The Best Backup Software at http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2278661,00.asp

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

As many young physicians might recognize, the title of today’s column is from a song by Prince Royce featuring Jennifer Lopez and Pitbull. This article, though, is about what we believe is likely an urgent matter for many of our readers – the issue of appropriately backing up information that resides on their personal computers. We were prompted to write about this after a colleague came to one of us in a panic after losing all of the information on her meticulously performed, but poorly conceived backup. For years she has been developing and storing her lectures on a flash drive, and every month she has been backing up her flash drive to her personal computer. She even set a reminder in her calendar to make sure that she perform those backups each and every month. Unfortunately, she lost her flash drive, and even more unfortunately discovered that what she thought were copies of files on her computer were actually only shortcuts to the files on her now-missing flash drive. All her files were gone.

We are going to organize our discussion in three parts: First, we want to convince you of the importance of making backups, essentially informational life insurance. Unlike life insurance, however, you have a pretty good chance of using your backups at some point over the next 10 years. Second, we are going to discuss locally based backups, and then lastly, we’ll cover cloud-based backups. This may seem like an incredibly dull topic to some, but we anticipate receiving emails of thanks over many years for the knowledge and actions that come out of today’s column.

Hard drive failure rates, derived from data published by companies that professionally manage large numbers of hard drives, is about 3%-5% in the first year. This remains at about 3% per year for the next 2-3 years, and then can go up to 10% or more per year as hard drives continue to age. That means that over a 4-year period, 15%-20% of hard drives are likely to fail.1,2 This fact underscores the importance of backing up your data, because there is a good chance that over time, loss of data will happen to you.

One strategy is to back up to an external drive. The drive can be either a flash drive if you have less than 128 GB to store, or a traditional external hard drive – a very affordable option for memory up to 4 TB (4,000 GB). There are many excellent external hard drives and flash drives from which to choose, but you also need to have backup software that will take the information from your personal computer and place it in an organized manner on your external drive. Many drives now come bundled with backup software. An example of such a drive is the Western Digital My Passport Elite. If the hard drive you have does not already have backup software, there are lots of good choices out there. Backup software solutions include Time Machine (built into all Mac Computers), and many software choices for PCs.3

While the speed of backup and recovery is fast – often just a few hours – there are two main issues that make external drives suboptimal as your main backup strategy. The first is that most people simply don’t remember to plug their external drive into their computer regularly; months and sometimes years can go by without backing up your files. The second issue, which is usually not considered, is that the hard drive usually sits on your desk next to your computer. Therefore, if there is a fire, a flood, an electrical surge, or even a simple spill on your desk, you may lose both your main files and your backup in one fell swoop. For this reason, if you choose to use an external drive as your backup method, you should back up to two different external drives and keep one drive in your office and one at home.

The best method of backup, and the one we recommend to everyone, eliminates the major disadvantages of local backups. This method is cloud-based backup. For cloud-based backup, you purchase a subscription with an annual fee, then you download software from the backup vendor to your computer. It usually takes about 15 minutes to set up the software by selecting the file folders that you would like to back up, then the software does the rest. The first backup can take a long time, typically a few days, as the speed of the backup is limited by the speed of your Internet connection. After that first time, though, backups don’t take long because they back up only the files that have changed since the previous backup.

The main advantages to cloud-based solutions is that once it has been set up, the software ensures that incremental backups occur automatically every time your computer is connected to the Internet. In addition, since the cloud backups are off-site, you are protected from an adverse occurrence taking out your backup drive and your computer when they are sitting next to each other on your desk. In addition, most cloud backup services also allow you to access your file from any computer or smartphone for access where and when you need the files.

So, let us end where we began, with lyrics from the music video, with which we agree, “Word of advice: Want a happy life … Back it up one more time.”

References

1. http://www.extremetech.com/computing/170748-how-long-do-hard-drives-actually-live-for

2. http://www.pcworld.com/article/131168/article.html

3. The Best Backup Software at http://www.pcmag.com/article2/0,2817,2278661,00.asp

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Aunt Tillie and electronic health records

I’m lost, but I’m making record time.

– A pilot, somewhere over the Pacific Ocean

The other day I was reading the printout of an electronic medical record of a patient transferred to our practice. The record reminded me a lot of my Aunt Tillie. Aunt Tillie was the aunt whom everyone would avoid at family gatherings when I was young because the minute she started talking you could be sure of two things: first, that it would be a long time till she stopped talking, and second, that most of what she had to say simply was not relevant to what anyone was interested in hearing. She was interested in what she was interested in and seemed to care little about the needs of anyone else in the room.

The patient in question was 32 years old and had gone to an emergency room for headache and chest pain. Headache and chest pain can be challenging problems, but there are still certain things in both the history and on physical exam that are relevant and informative. It was hard to find those things in this medical record. After a relatively short history of present illness (HPI) that said my patient had presented with 1 day of headache and chest pain. The HPI on this record took up less than three lines. The assessment scales went on for over two pages. When we see records like this, driven by a system that desires to document every question or scale that every possible insurer might be looking for on every possible patient, we fear that common sense has died.

Among the extraneous information in the EHR was a Morse Fall Scale score. The Morse scale and point system were carefully laid out with the actions to be taken at various levels of risk, from bed in the lowest position to when to use skid-proof slipper socks. Then the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk was recorded, followed by the Domestic Violence Score, complete with indication of whether the patient was under immediate threat and whether police, social services, and mental health professionals were notified. There also was a pain assessment that was filled out with an area indicating that the patient and her family were instructed to tell someone if her level of pain changed. Seriously. The pain assessment scale was located right after the suicide risk assessment and the depression scale, presumably because if the depression assessment occurred any later in the visit the patient might have scored higher out of desperation.

The death of common sense is neither pretty nor fast. As we fill out scales that answer neither evidence-based preventive health interventions nor meet the current needs of the patient, we have become concerned that we, as physicians, have chosen a path that seems to be the clearest – including all possible questions on all possible patients – but is actually fraught with peril.

We have become so concerned about not missing any potential source of reimbursement and protecting ourselves from any source of liability that our visits take longer and our focus has become distracted from the real problems that patients bring to us. By so doing we end up not accomplishing our goal of maximizing reimbursement because we move slower through our visits, filling out information that is not meaningful to either patient or physician. We also do not protect ourselves from liability when we are distracted by the need to fill out irrelevant information and are subsequently left with less time to get through the important parts of our visit, leaving us to take a less detailed history than we might otherwise have performed.

In 1995, Phillip K. Howard wrote a book about the legal system, The Death of Common Sense (Random House). In it, he argues that the desire to have clear rules that allow uniformity in the operation of law has resulted in a system that is inefficient and “precludes the exercise of judgment.” Mr. Howard argues that, no matter how detailed, laws cannot anticipate all of society’s needs. He goes on to state that “law can’t think, and so law must be entrusted to humans and they must take responsibility for their interpretation of it.”

We find a similar case to what Mr. Howard described to be occurring in medicine today. Patients present as individuals, with complex problems that require well-trained clinicians who can prioritize among the many concerns and determine which algorithms of diagnosis and treatment are appropriate to a given visit on a given day. When each visit follows a rote format, no visit follows the format that best serves the patient.

The argument that each visit is unique is not an argument for chaos in the organization of our visits and record – the visits need to be organized and recorded in a standard fashion. It is, rather, recognition that patients typically present with atypical symptoms and that all patients and visits are different from one another. To provide excellent medical care requires that well-trained clinicians make choices about what should be addressed at any given visit and that our charts and electronic record systems must be driven by patient needs and outcomes, not checkboxes derived from potential needs that are divorced from common sense for the visit at hand.

As we reflect further on this issue, we have come to the conclusion that the difference between our EHR systems and Aunt Tillie is that, when Thanksgiving came, we could avoid Aunt Tillie.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

I’m lost, but I’m making record time.

– A pilot, somewhere over the Pacific Ocean

The other day I was reading the printout of an electronic medical record of a patient transferred to our practice. The record reminded me a lot of my Aunt Tillie. Aunt Tillie was the aunt whom everyone would avoid at family gatherings when I was young because the minute she started talking you could be sure of two things: first, that it would be a long time till she stopped talking, and second, that most of what she had to say simply was not relevant to what anyone was interested in hearing. She was interested in what she was interested in and seemed to care little about the needs of anyone else in the room.

The patient in question was 32 years old and had gone to an emergency room for headache and chest pain. Headache and chest pain can be challenging problems, but there are still certain things in both the history and on physical exam that are relevant and informative. It was hard to find those things in this medical record. After a relatively short history of present illness (HPI) that said my patient had presented with 1 day of headache and chest pain. The HPI on this record took up less than three lines. The assessment scales went on for over two pages. When we see records like this, driven by a system that desires to document every question or scale that every possible insurer might be looking for on every possible patient, we fear that common sense has died.

Among the extraneous information in the EHR was a Morse Fall Scale score. The Morse scale and point system were carefully laid out with the actions to be taken at various levels of risk, from bed in the lowest position to when to use skid-proof slipper socks. Then the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk was recorded, followed by the Domestic Violence Score, complete with indication of whether the patient was under immediate threat and whether police, social services, and mental health professionals were notified. There also was a pain assessment that was filled out with an area indicating that the patient and her family were instructed to tell someone if her level of pain changed. Seriously. The pain assessment scale was located right after the suicide risk assessment and the depression scale, presumably because if the depression assessment occurred any later in the visit the patient might have scored higher out of desperation.

The death of common sense is neither pretty nor fast. As we fill out scales that answer neither evidence-based preventive health interventions nor meet the current needs of the patient, we have become concerned that we, as physicians, have chosen a path that seems to be the clearest – including all possible questions on all possible patients – but is actually fraught with peril.

We have become so concerned about not missing any potential source of reimbursement and protecting ourselves from any source of liability that our visits take longer and our focus has become distracted from the real problems that patients bring to us. By so doing we end up not accomplishing our goal of maximizing reimbursement because we move slower through our visits, filling out information that is not meaningful to either patient or physician. We also do not protect ourselves from liability when we are distracted by the need to fill out irrelevant information and are subsequently left with less time to get through the important parts of our visit, leaving us to take a less detailed history than we might otherwise have performed.

In 1995, Phillip K. Howard wrote a book about the legal system, The Death of Common Sense (Random House). In it, he argues that the desire to have clear rules that allow uniformity in the operation of law has resulted in a system that is inefficient and “precludes the exercise of judgment.” Mr. Howard argues that, no matter how detailed, laws cannot anticipate all of society’s needs. He goes on to state that “law can’t think, and so law must be entrusted to humans and they must take responsibility for their interpretation of it.”

We find a similar case to what Mr. Howard described to be occurring in medicine today. Patients present as individuals, with complex problems that require well-trained clinicians who can prioritize among the many concerns and determine which algorithms of diagnosis and treatment are appropriate to a given visit on a given day. When each visit follows a rote format, no visit follows the format that best serves the patient.

The argument that each visit is unique is not an argument for chaos in the organization of our visits and record – the visits need to be organized and recorded in a standard fashion. It is, rather, recognition that patients typically present with atypical symptoms and that all patients and visits are different from one another. To provide excellent medical care requires that well-trained clinicians make choices about what should be addressed at any given visit and that our charts and electronic record systems must be driven by patient needs and outcomes, not checkboxes derived from potential needs that are divorced from common sense for the visit at hand.

As we reflect further on this issue, we have come to the conclusion that the difference between our EHR systems and Aunt Tillie is that, when Thanksgiving came, we could avoid Aunt Tillie.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

I’m lost, but I’m making record time.

– A pilot, somewhere over the Pacific Ocean

The other day I was reading the printout of an electronic medical record of a patient transferred to our practice. The record reminded me a lot of my Aunt Tillie. Aunt Tillie was the aunt whom everyone would avoid at family gatherings when I was young because the minute she started talking you could be sure of two things: first, that it would be a long time till she stopped talking, and second, that most of what she had to say simply was not relevant to what anyone was interested in hearing. She was interested in what she was interested in and seemed to care little about the needs of anyone else in the room.

The patient in question was 32 years old and had gone to an emergency room for headache and chest pain. Headache and chest pain can be challenging problems, but there are still certain things in both the history and on physical exam that are relevant and informative. It was hard to find those things in this medical record. After a relatively short history of present illness (HPI) that said my patient had presented with 1 day of headache and chest pain. The HPI on this record took up less than three lines. The assessment scales went on for over two pages. When we see records like this, driven by a system that desires to document every question or scale that every possible insurer might be looking for on every possible patient, we fear that common sense has died.

Among the extraneous information in the EHR was a Morse Fall Scale score. The Morse scale and point system were carefully laid out with the actions to be taken at various levels of risk, from bed in the lowest position to when to use skid-proof slipper socks. Then the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk was recorded, followed by the Domestic Violence Score, complete with indication of whether the patient was under immediate threat and whether police, social services, and mental health professionals were notified. There also was a pain assessment that was filled out with an area indicating that the patient and her family were instructed to tell someone if her level of pain changed. Seriously. The pain assessment scale was located right after the suicide risk assessment and the depression scale, presumably because if the depression assessment occurred any later in the visit the patient might have scored higher out of desperation.

The death of common sense is neither pretty nor fast. As we fill out scales that answer neither evidence-based preventive health interventions nor meet the current needs of the patient, we have become concerned that we, as physicians, have chosen a path that seems to be the clearest – including all possible questions on all possible patients – but is actually fraught with peril.

We have become so concerned about not missing any potential source of reimbursement and protecting ourselves from any source of liability that our visits take longer and our focus has become distracted from the real problems that patients bring to us. By so doing we end up not accomplishing our goal of maximizing reimbursement because we move slower through our visits, filling out information that is not meaningful to either patient or physician. We also do not protect ourselves from liability when we are distracted by the need to fill out irrelevant information and are subsequently left with less time to get through the important parts of our visit, leaving us to take a less detailed history than we might otherwise have performed.

In 1995, Phillip K. Howard wrote a book about the legal system, The Death of Common Sense (Random House). In it, he argues that the desire to have clear rules that allow uniformity in the operation of law has resulted in a system that is inefficient and “precludes the exercise of judgment.” Mr. Howard argues that, no matter how detailed, laws cannot anticipate all of society’s needs. He goes on to state that “law can’t think, and so law must be entrusted to humans and they must take responsibility for their interpretation of it.”

We find a similar case to what Mr. Howard described to be occurring in medicine today. Patients present as individuals, with complex problems that require well-trained clinicians who can prioritize among the many concerns and determine which algorithms of diagnosis and treatment are appropriate to a given visit on a given day. When each visit follows a rote format, no visit follows the format that best serves the patient.

The argument that each visit is unique is not an argument for chaos in the organization of our visits and record – the visits need to be organized and recorded in a standard fashion. It is, rather, recognition that patients typically present with atypical symptoms and that all patients and visits are different from one another. To provide excellent medical care requires that well-trained clinicians make choices about what should be addressed at any given visit and that our charts and electronic record systems must be driven by patient needs and outcomes, not checkboxes derived from potential needs that are divorced from common sense for the visit at hand.

As we reflect further on this issue, we have come to the conclusion that the difference between our EHR systems and Aunt Tillie is that, when Thanksgiving came, we could avoid Aunt Tillie.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

Meaningful use – Stage 2 (Part 1 of 2)

The words "meaningful use" have been making providers cringe for more than 2 years now. Those clinicians who worked hard to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 1 requirements now must go on to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 2 requirements. We recently heard one of our colleagues describe stage 2 of meaningful use as reminiscent of the 1978 movie "Jaws 2," the ads for which ran with the tagline: "Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water..."

As you may be aware, on August 29th the Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. This only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time due to vendor delays. Unfortunately, this flexibility does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new workflows (we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility). Regardless of stage or year, everyone is on a 90-day reporting period for 2014, but remember that 2015 will require a full year of reporting (January through December). So even if you qualify for the flexibility and opt to stick with the Stage 1 measures, you’ll need to be ready to hit the ground running with Stage 2 as soon as the ball drops on January 1st, 2015.

The government’s intent with the EHR incentive program is to ensure that practitioners use an EHR to do more than what could otherwise be done on a paper note. As we review the criteria that must be met for stage 2 of meaningful use, we will see the inclusion of menu items and quality measures that are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care, population management (even for patients who might not come in to the office), and physician-patient communication. By articulating these goals we can see that they are very different from what most practitioners perceive to be the main outcome of the meaningful use rules: the creation of a lot of unnecessary busywork in the office that yields very little benefit for practitioners or patients.

The EHR incentive program consists of three stages.

• Stage 1, which many practitioners have already accomplished and received incentive dollars for completing, focused on basic data capture.

• Stage 2, which focuses on more advanced processes including additional requirements for e-prescribing, incorporating lab results into the record, electronic transmission of patient summaries across systems, and increased patient engagement.

• Stage 3, which will utilize the processes put in place in the first two stages and focus on improved patient outcomes.

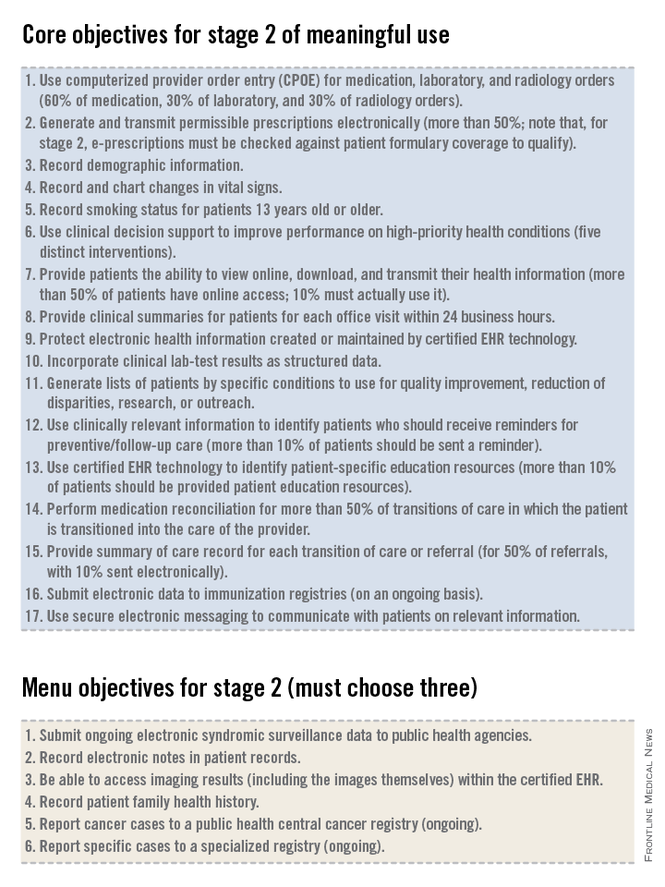

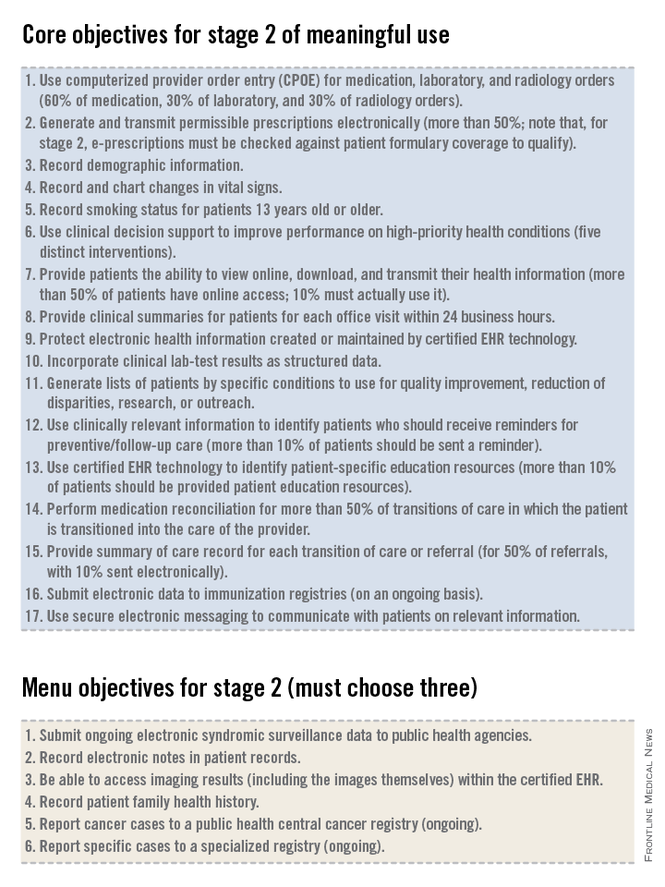

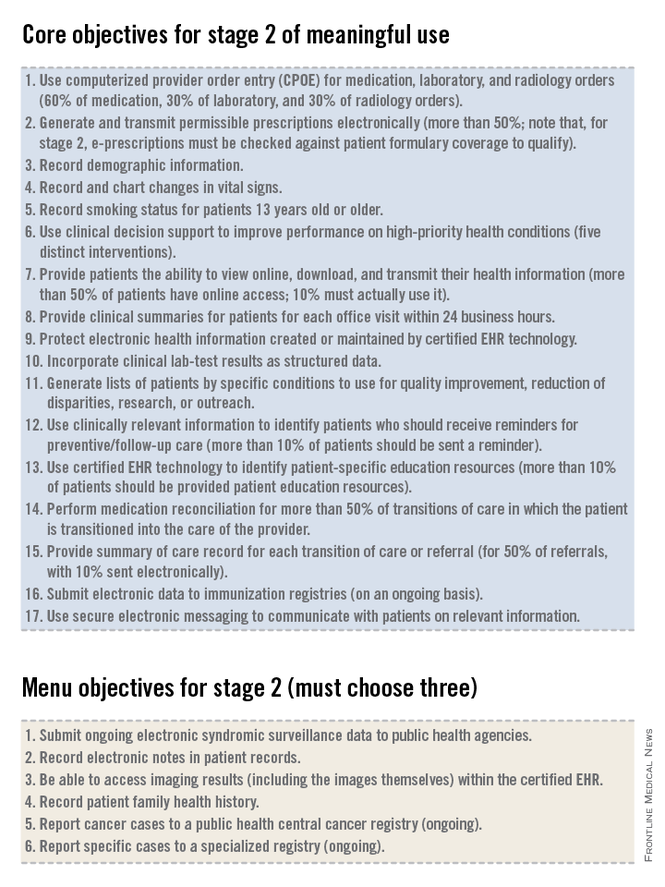

For stage 2 of meaningful use, clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and 3 menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs). Many of the objectives in stage 2 are the same as those from stage 1. Some objectives that were in the set of choices in stage 1 are now part of the mandatory core set for stage 2, required for all providers. Some objectives that were in the core set in stage 1 now have higher thresholds or percentages of patients that must meet the criteria in order to qualify for meaningful use in stage 2. The data reported to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for CQMs must originate from an EHR that has been certified for 2014 standards. This rule requires that clinicians upgrade their EHR to current technology standards, a rule that is good for EHR vendors, makes sense when we look at the system as a whole, but may be very expensive for many practitioners.

In addition to the 17 core objectives, and 3 out of 6 menu objectives, clinicians will need to report on nine CQMs. We will review the details of reporting on CQMs in next month in part 2 of our overview of Meaningful Use Stage 2.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The words "meaningful use" have been making providers cringe for more than 2 years now. Those clinicians who worked hard to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 1 requirements now must go on to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 2 requirements. We recently heard one of our colleagues describe stage 2 of meaningful use as reminiscent of the 1978 movie "Jaws 2," the ads for which ran with the tagline: "Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water..."

As you may be aware, on August 29th the Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. This only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time due to vendor delays. Unfortunately, this flexibility does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new workflows (we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility). Regardless of stage or year, everyone is on a 90-day reporting period for 2014, but remember that 2015 will require a full year of reporting (January through December). So even if you qualify for the flexibility and opt to stick with the Stage 1 measures, you’ll need to be ready to hit the ground running with Stage 2 as soon as the ball drops on January 1st, 2015.

The government’s intent with the EHR incentive program is to ensure that practitioners use an EHR to do more than what could otherwise be done on a paper note. As we review the criteria that must be met for stage 2 of meaningful use, we will see the inclusion of menu items and quality measures that are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care, population management (even for patients who might not come in to the office), and physician-patient communication. By articulating these goals we can see that they are very different from what most practitioners perceive to be the main outcome of the meaningful use rules: the creation of a lot of unnecessary busywork in the office that yields very little benefit for practitioners or patients.

The EHR incentive program consists of three stages.

• Stage 1, which many practitioners have already accomplished and received incentive dollars for completing, focused on basic data capture.

• Stage 2, which focuses on more advanced processes including additional requirements for e-prescribing, incorporating lab results into the record, electronic transmission of patient summaries across systems, and increased patient engagement.

• Stage 3, which will utilize the processes put in place in the first two stages and focus on improved patient outcomes.

For stage 2 of meaningful use, clinicians must meet or exceed the thresholds for the 17 core objectives and 3 menu objectives, as well as report on defined Clinical Quality Measures (CQMs). Many of the objectives in stage 2 are the same as those from stage 1. Some objectives that were in the set of choices in stage 1 are now part of the mandatory core set for stage 2, required for all providers. Some objectives that were in the core set in stage 1 now have higher thresholds or percentages of patients that must meet the criteria in order to qualify for meaningful use in stage 2. The data reported to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for CQMs must originate from an EHR that has been certified for 2014 standards. This rule requires that clinicians upgrade their EHR to current technology standards, a rule that is good for EHR vendors, makes sense when we look at the system as a whole, but may be very expensive for many practitioners.

In addition to the 17 core objectives, and 3 out of 6 menu objectives, clinicians will need to report on nine CQMs. We will review the details of reporting on CQMs in next month in part 2 of our overview of Meaningful Use Stage 2.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Memorial Hospital and professor of family and community medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia.

The words "meaningful use" have been making providers cringe for more than 2 years now. Those clinicians who worked hard to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 1 requirements now must go on to demonstrate meaningful use under the stage 2 requirements. We recently heard one of our colleagues describe stage 2 of meaningful use as reminiscent of the 1978 movie "Jaws 2," the ads for which ran with the tagline: "Just when you thought it was safe to go back in the water..."

As you may be aware, on August 29th the Department of Health and Human Services published a final rule allowing certain eligible providers the flexibility to continue using the Stage 1 criteria for the 2014 attestation year, even if they were due to start Stage 2. This only applies to those who have been unable to obtain the 2014-certified software in time due to vendor delays. Unfortunately, this flexibility does not extend to those who can’t meet Stage 2 due to measure difficulty or procrastination in purchasing software or adopting new workflows (we recommend speaking with a meaningful use expert or consultant before attempting to take advantage of this flexibility). Regardless of stage or year, everyone is on a 90-day reporting period for 2014, but remember that 2015 will require a full year of reporting (January through December). So even if you qualify for the flexibility and opt to stick with the Stage 1 measures, you’ll need to be ready to hit the ground running with Stage 2 as soon as the ball drops on January 1st, 2015.

The government’s intent with the EHR incentive program is to ensure that practitioners use an EHR to do more than what could otherwise be done on a paper note. As we review the criteria that must be met for stage 2 of meaningful use, we will see the inclusion of menu items and quality measures that are aimed at enhancing actionable decision support to improve the quality of medical care, population management (even for patients who might not come in to the office), and physician-patient communication. By articulating these goals we can see that they are very different from what most practitioners perceive to be the main outcome of the meaningful use rules: the creation of a lot of unnecessary busywork in the office that yields very little benefit for practitioners or patients.

The EHR incentive program consists of three stages.

• Stage 1, which many practitioners have already accomplished and received incentive dollars for completing, focused on basic data capture.