User login

Advanced team-based care: How we made it work

Leaders in health care and practicing physicians recognize the need for changes in how health care is delivered.1-3 Despite this awareness, though, barriers to meaningful change persist and the current practice environment wherein physicians must routinely spend 2 hours on electronic health records (EHRs) and desk work for every hour of direct face time with patients4 is driving trainees away from ambulatory specialties and is contributing to physicians’ decisions to reduce their practices to part-time, retire early, or leave medicine altogether.5,6 Those who persevere in this environment with heavy administrative burdens run the increasing risk of burnout.7

Some physicians and practices are responding by taking creative measures to reform the way patient care is delivered. Bellin Health—a 160-provider, multispecialty health system in northeast Wisconsin where one of the authors (JJ) works—introduced an advanced team-based care (aTBC) model between November 2014 and November 2018, starting with our primary care providers. The development and introduction of this new model arose from an iterative, multidisciplinary process driven by the desire to transform the Triple Aim—enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and reducing costs—into a Quadruple Aim8 by additionally focusing on improving the work life of health care providers, which, in turn, will help achieve the first 3 goals. In introducing an aTBC model, Bellin Health focused on 3 elements: office visit redesign, in-basket management redesign, and the use of extended care team members and system and community resources to assist in the care of complex and high-risk patients.

Herein we describe the 3 components of our aTBC model,1,9 identify the barriers that existed in the minds of multiple stakeholders (from patients to clinicians and Bellin executives), and describe the strategies that enabled us to overcome these barriers.

The impetus behind our move to aTBC

Bellin Health considered a move to an aTBC model to be critical in light of factors in the health care environment, in general, and at Bellin, in particular. The factors included

- an industry-wide shift to value-based payments, which requires new models for long-term financial viability.

- recognition that physician and medical staff burnout leads to lower productivity and, in some cases, workforce losses.5,6 Replacing a physician in a practice can be difficult and expensive, with cost estimates of $500,000 to more than $1 million per physician.10,11

- a belief that aTBC could help the Bellin Health leadership team meet its organizational goals of improved patient satisfaction, achieve gains in quality measures, enhance engagement and loyalty among patients and employees, and lower recruitment costs.

A 3-part aTBC initiative

■ Part 1: Redesign the office visit

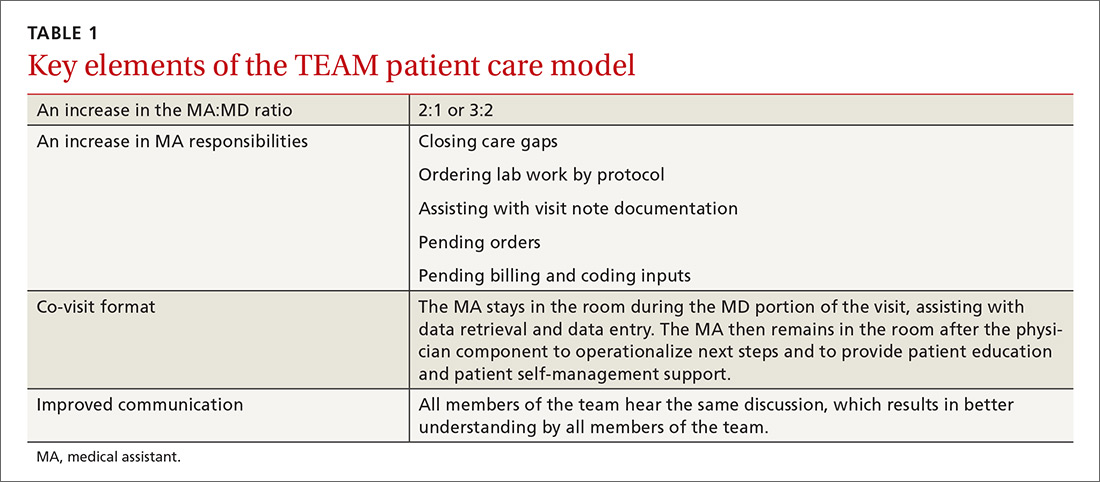

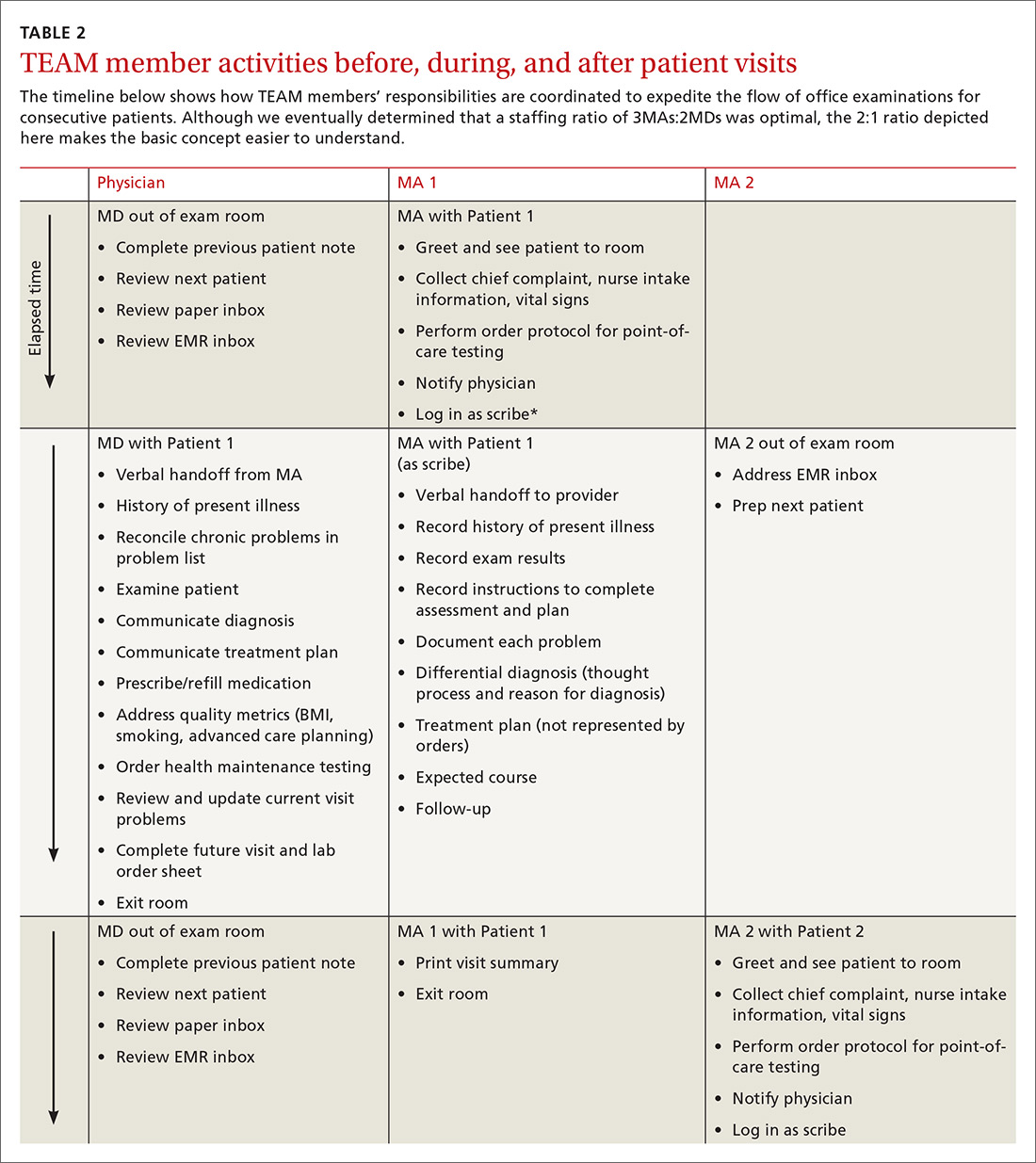

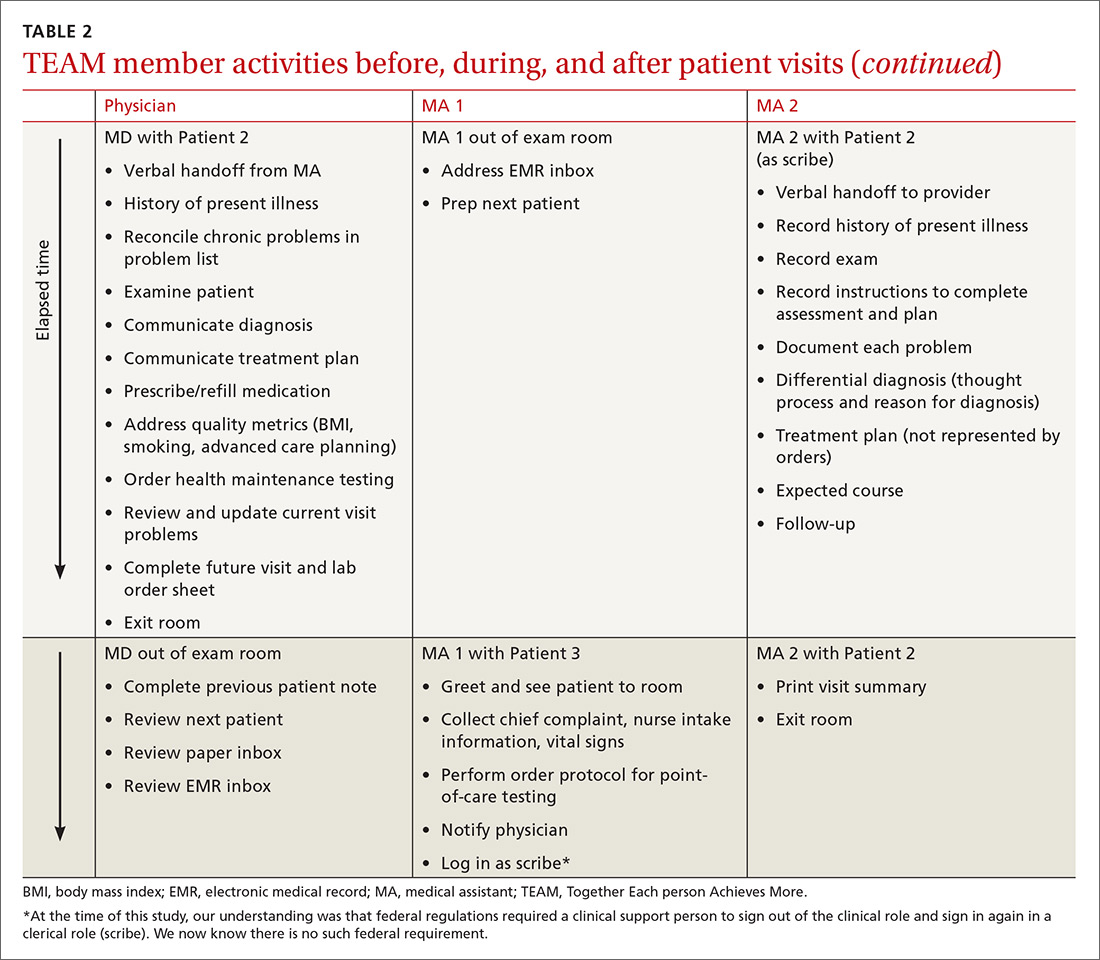

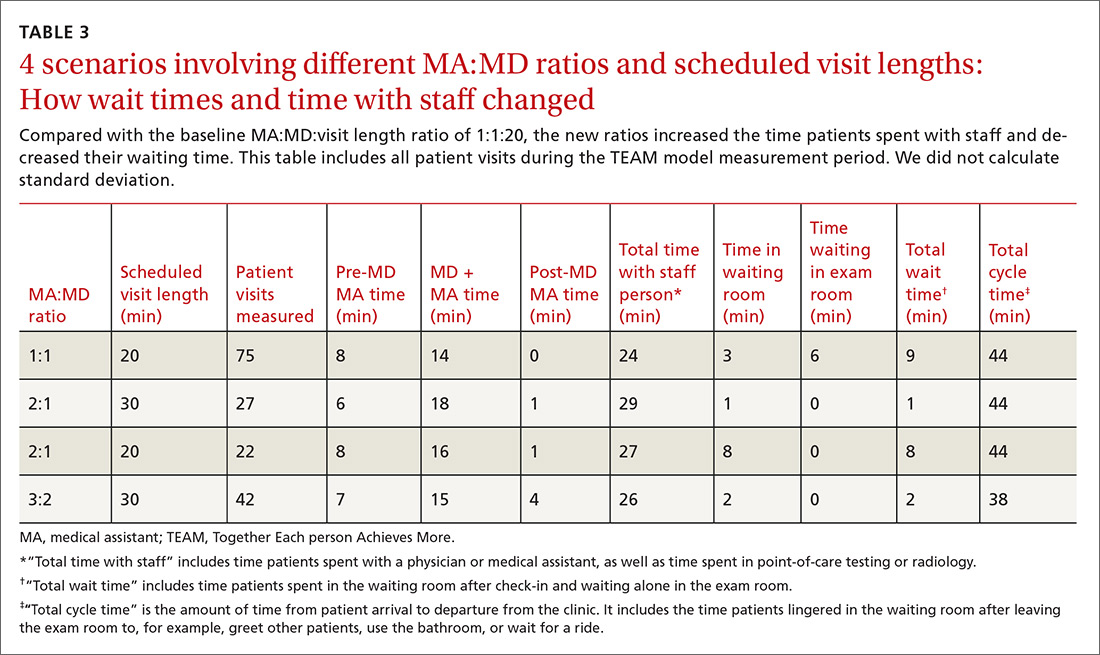

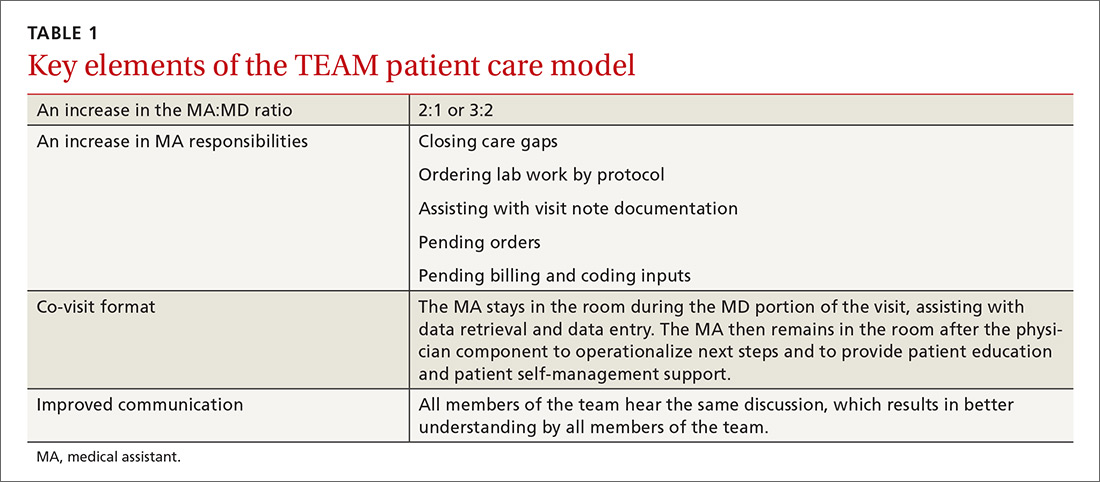

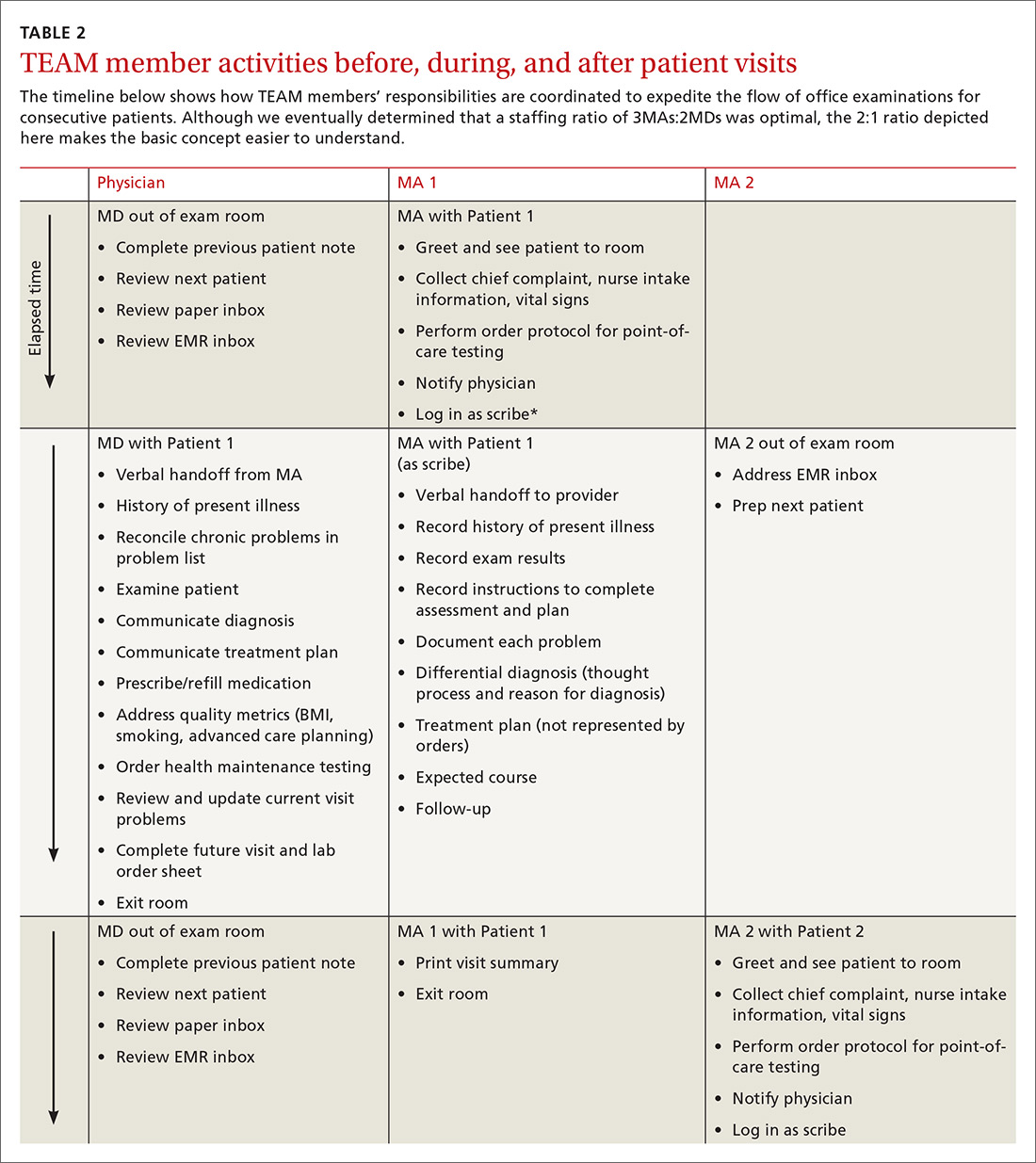

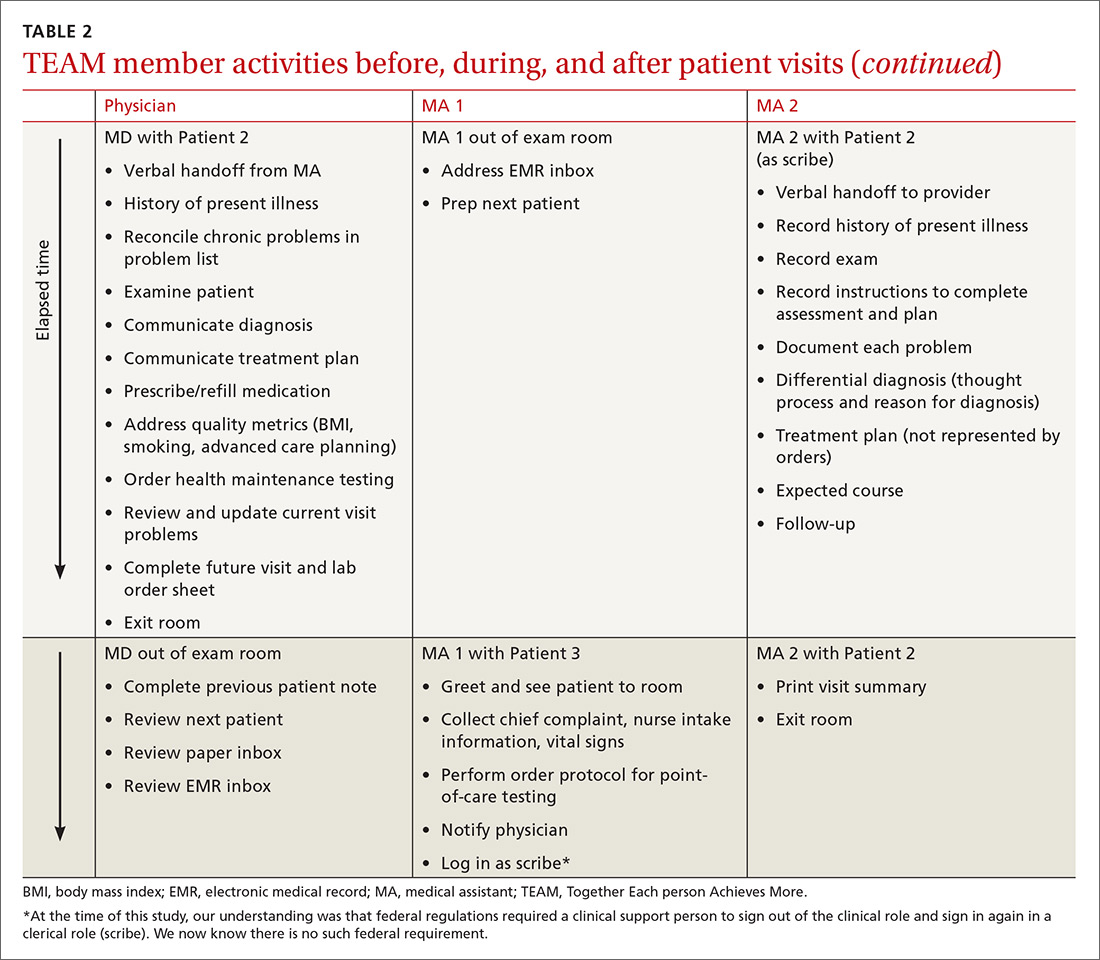

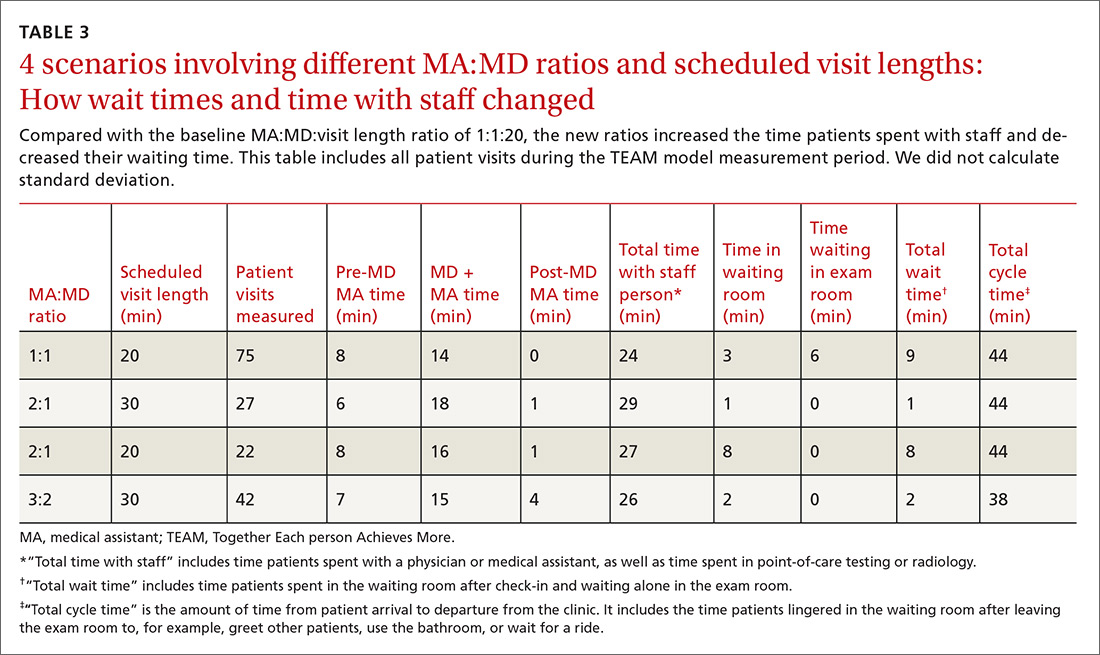

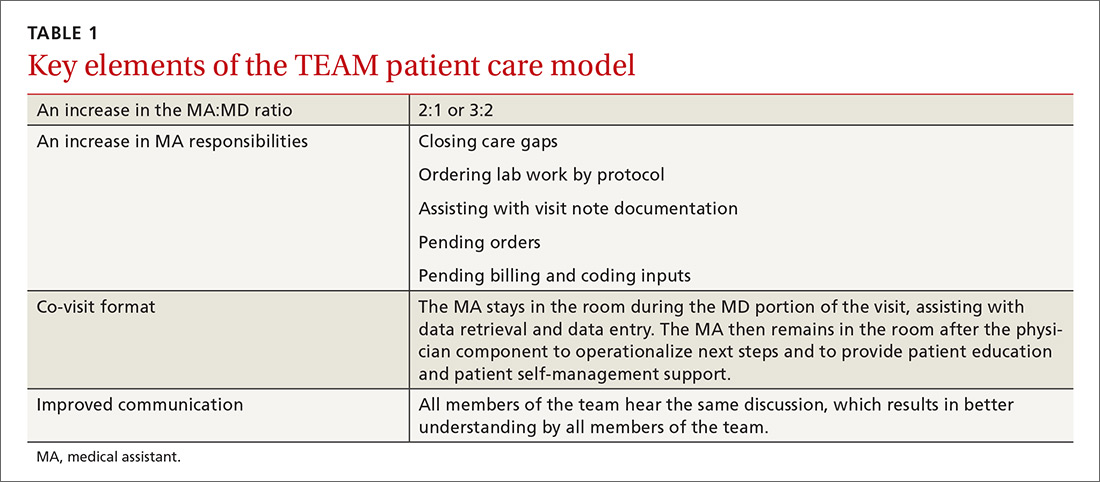

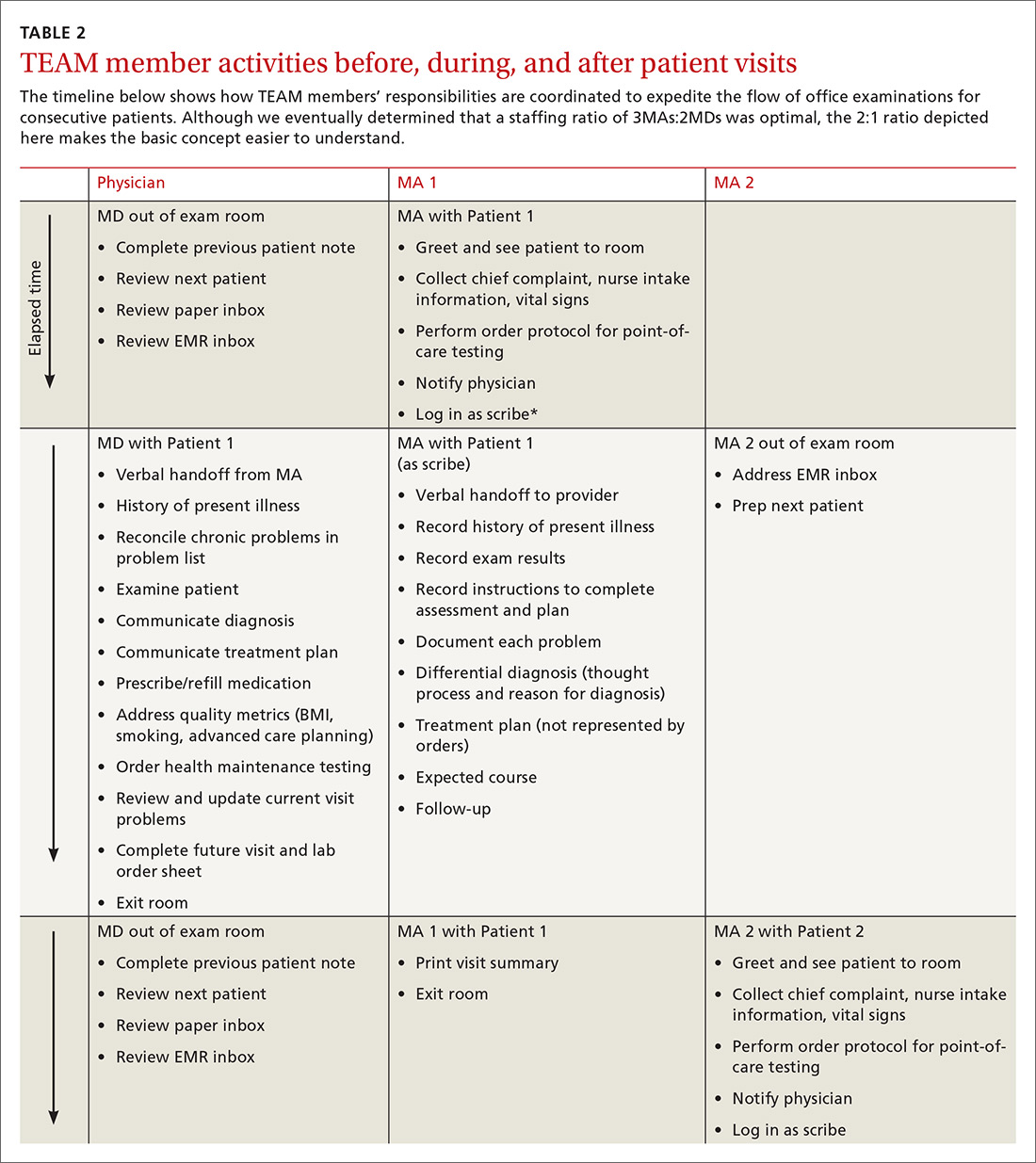

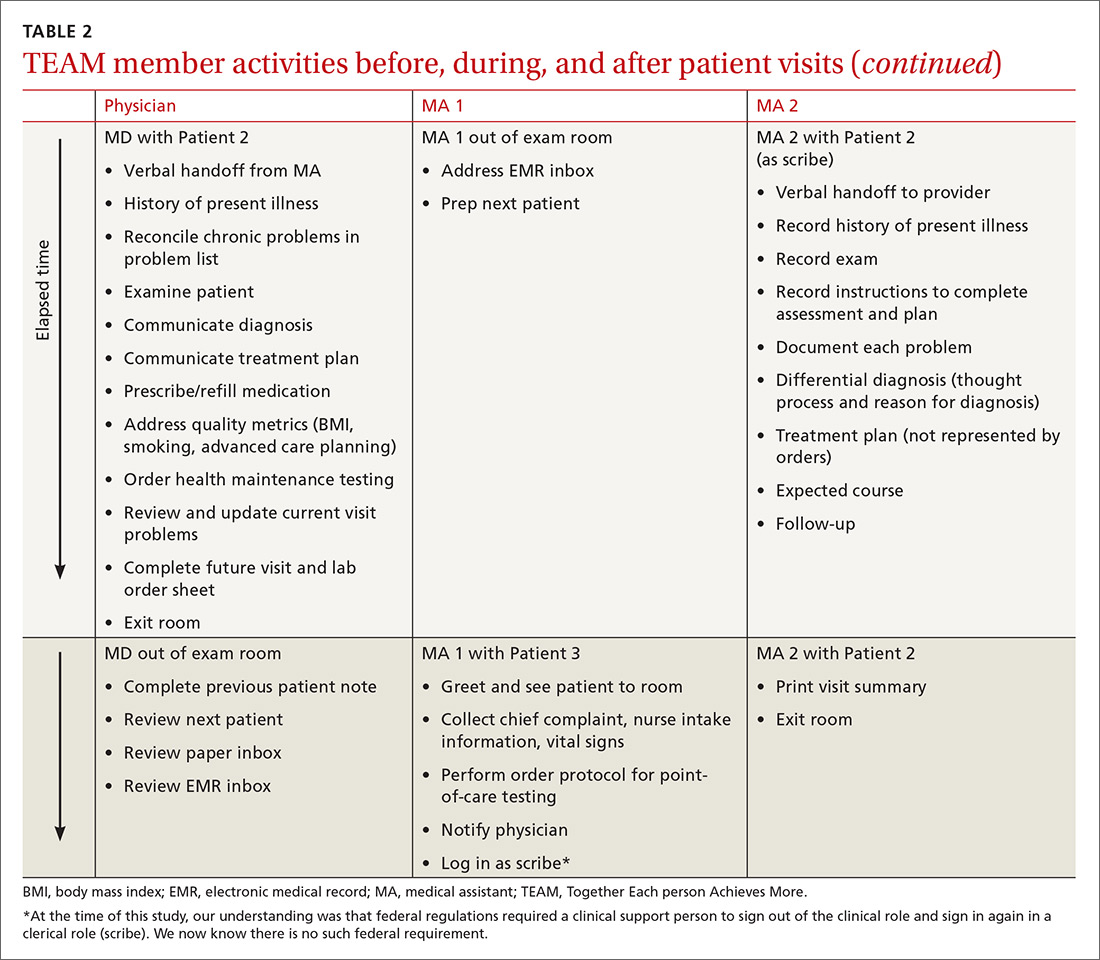

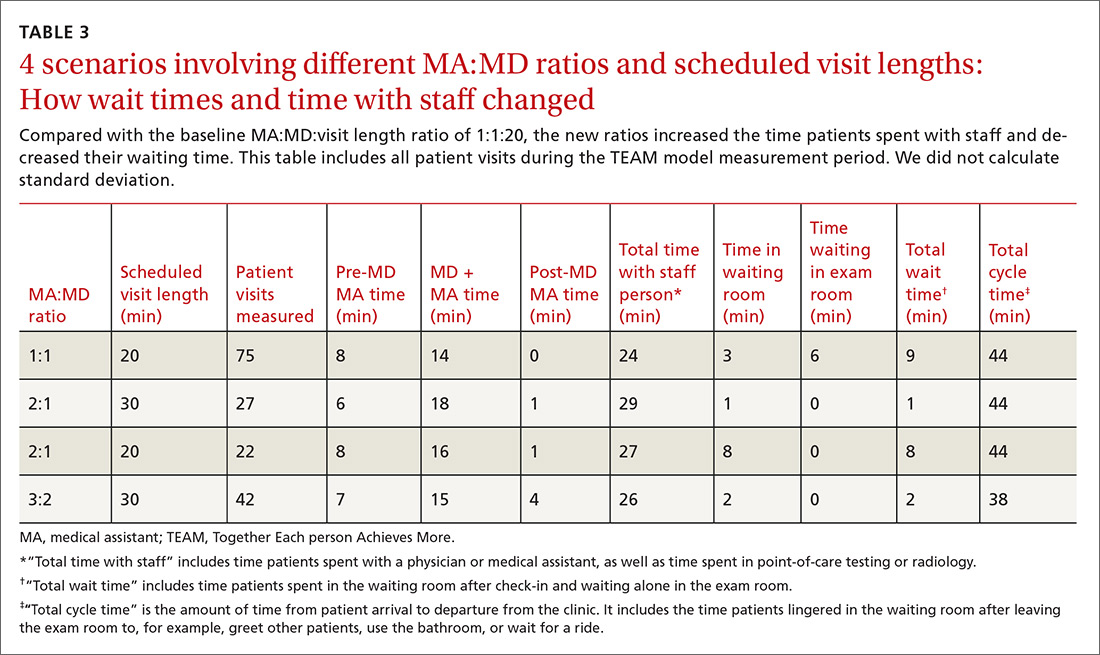

We redesigned staffing and workflow for office visits to maximize the core skills of physicians, which required distributing ancillary tasks among support staff. We up-trained certified medical assistants (CMAs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) to take on the new role of care team coordinator (CTC) and optimized the direct clinical support ratio for busier physicians. For physicians who were seeing 15 to 19 patients a day, a ratio of 3 CTCs to 2 physicians was implemented; for those seeing 20 or more patients a day, we used a support ratio of 2:1.

The role of CTC was designed so that he or she would accompany a patient throughout the entire appointment. Responsibilities were broken out as follows:

Pre-visit. Before the physician enters the room, the CTC would now perform expanded rooming functions including pending orders, refill management, care gap closure using standing orders, agenda setting, and preliminary documentation.12

Visit. The CTC would now hand off the patient to the physician and stay in the room to document details of the visit and record new orders for consults, x-ray films, referrals, or prescriptions.13 This intensive EHR support was established to ensure that the physician could focus directly on the patient without the distraction of the computer.

Continue to: Post-visit

Post-visit. After a physician leaves a room, the CTC was now charged with finishing the pending orders, setting up the patient’s next appointment and pre-visit labs, reviewing details of the after-visit summary, and doing any basic health coaching with the patient. During this time, the physician would use the co-location space to review and edit the documentation, cosign the orders and prescriptions submitted by the CTC, and close the chart before going into the next room with the second CTC. The need to revisit these details after clinic hours was eliminated.

Another change … The role of our phone triage registered nurses (RN) was expanded. Care team RNs began providing diabetes counseling, blood pressure checks, annual wellness visits (AWV), and follow-up through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)'s Chronic Care Management and Transitional Care Management programs.

■ Part 2: Redesign between-visit in-basket management

Responding to an increasing number of inbox messages had become overwhelming for our physicians. Bellin Health’s management was aware that strategic delegation of inbox messages could save an hour or more of a physician’s time each day.14 Bellin implemented a procedure whereby inbox test results would be handled by the same CTC who saw the patient, thereby extending continuity. If the results were normal, the CTC would contact the patient. If the results were abnormal, the physician and the CTC would discuss them and develop a plan. Co-location of the RN, the CTC, and the physician would leverage face-to-face communication and make in-basket management more efficient.

■ Part 3: Redesign population health management

We developed an Extended Care Team (ECT), including social workers, clinical pharmacists, RN care coordinators, and diabetes educators, to assist with the care of patients with high-risk disorders or otherwise complex issues. These team members would work closely with the CTC, care team RN, and physician to review patients, develop plans of care, optimize management, and improve outcomes. Patients would be identified as candidates for potential ECT involvement based on the physician’s judgment in consultation with an EHR-based risk score for hospitalization or emergency department visit.

As we developed new processes, such as screening for determinants of health, we engaged additional system and community resources to help meet the needs of our patients.

Continue to: A look at stakeholder concerns and overcoming the barriers

A look at stakeholder concerns and overcoming the barriers

Critical to our success was being attentive to the concerns of our stakeholders and addressing them. Along the way, we gained valuable implementation insights, which we share here along with some specifics about how, exactly, we did things at Bellin.

Patients

Some patients expressed hesitation at having a person other than their physician in the exam room. They worried that the intimacy and privacy with their physician would be lost. In light of this, we gave patients the option not to have the CTC remain in the room. However, patients quickly saw the value of this team-based care approach and seldom asked to be seen without the CTC.

Throughout the process, we surveyed patients for feedback on their experiences. Comments indicated that the presence of the CTC in our team-based model led to positive patient experiences:

My physician is fully attentive. Patients appreciated that physicians were not distracted by the computer in the exam room. “I feel like I’ve got my doctor back” has been a common refrain.

The office staff is more responsive. The CTC, having been present during the appointment, has a deeper understanding of the care plan and can respond to calls or emails between visits, thereby reducing the time patients must wait for answers. One patient commented that, “I love [the doctor’s] team; his nurses are willing to answer every question I have.”

Continue to: I increasingly feel that I'm understood

I increasingly feel that I’m understood. We have seen patients develop meaningful relationships with other team members, confiding in them in ways that they hadn’t always done with physicians and advanced practice clinicians (APCs). Team members, in turn, have added valuable insights that help optimize patients’ care. In particular, the care of patients with multiple needs has been enhanced with the addition of ECT members who work with the core team and use their expertise to optimize the care of these patients.

Certified medical assistants and licensed practical nurses

Bellin’s leadership knew that team documentation could cause stress for the CMA, who, acting as a CTC, wanted to avoid misrepresenting details of the clinical encounter.13 Adding to the stress were other duties that would need to be learned, including agenda setting, refill management, care gap closure, and health coaching. With thorough training and preparation, many—but not all—of our CMAs and LPNs were able to successfully make the transition and flourish.

Implementation strategies

Provide thorough training. Our training process started 8 weeks before it was time to “go live.” There were weekly hour-long training sessions in population health basics, team culture and change management, documentation basics, and new roles and responsibilities. In the final week, the entire aTBC team sat together for 3 days of EHR training. All new teams shadowed existing teams to get a clear picture of the new processes.

Create a community of support. As our CMAs adapted to their new CTC roles, it was critical that they had support from experienced CTCs. Encouragement and patience from physicians were—and are—essential for CTCs to develop confidence in their new roles.

Enable ongoing feedback. We introduced weekly team meetings to enhance team communication and dynamics. Forums for all roles are held periodically to facilitate discussion, share learning, and enable support between teams.

Continue to: Use EHR tools to facilitate this work

Use EHR tools to facilitate this work. Using standard templates and documentation tools helped CTCs develop the confidence needed to thrive in their new role. Knowing these tools were available helped CTCs become effective in helping the team manage the between-visit work.

Monitor workload. As we developed more workflows and processes, we took care to monitor the amount of additional work for those in this role. We offloaded work whenever possible. For example, coordinated refill management at time of service, coupled with a back-up centralized refill system, can significantly decrease the number of refill requests made to CTCs. We continue to adjust staffing, where appropriate, to provide adequate support for those in this valuable role.

Be prepared for turnover. As CTCs became empowered in their new roles, some decided to advance their training into other roles. We developed a plan for replacing and training new staff. Higher pay can also be used to help attract and retain these staff members. Bellin uses LPNs in this role to ensure adequate staffing. Other health systems have developed a tier system for CMAs to improve retention.

Registered nurses

Before our move to an aTBC model, our office RNs primarily managed phone triage. Now the nurses were enlisted to play a more active role in patient care and team leadership. Although it was a dramatic departure from prior responsibilities, the majority of Bellin’s RNs have found increased satisfaction in taking on direct patient care.

Implementation strategies

Define new roles and provide training. In addition to participating in acute patient visits, consider ways that care team RNs can expand responsibilities as they pertain to disease counseling, population health management, and team leadership.15 At Bellin, the expanded role of the RN is evident in diabetes education and Medicare AWVs. Specifically, RNs now provide diabetes education to appropriate patients following a warm handoff from the physician at the time of the visit. RNs now also complete Medicare AWVs, which frees up physicians for other tasks and helps ensure sustainability for the new RN roles. Rates of completed AWVs at Bellin are now more than 70%, compared with reported national rates of less than 30%.16

Continue to: Maximize co-location

Maximize co-location. It is helpful to have the team members whose work is closely related—such as the CTCs and the RN for the team—to be situated near each other, rather than down a hall or in separate offices. Since the RN is co-located with the core teams at Bellin, there is now greater opportunity for verbal interaction, rather than just electronic communications, for matters such as triage calls and results management. RNs also provide a valuable resource for CMAs and LPNs, as well as help oversee team management of the in-basket.

Evaluate sustainability. Additional roles for the RNs required additional RN staffing. We assessed the new workload duties and balanced that against potential revenue from RN visits. This analysis indicated that an optimal ratio was 1 RN to every 3000 patients. This would allow an adequate number of RNs to fulfill additional roles and was financially sustainable with the goal of 4 billable RN visits per day.

Physicians

Bellin’s leadership recognized that some physicians might perceive team-based care as eroding their primary responsibility for patients’ care. Physicians have historically been trained in a model based on the primacy of the individual physician and that can be a hurdle to embracing team culture as a new paradigm of care. Several strategies helped us and can help others, too.

Implementation strategies

Cultivate trust. Thorough training of CTCs and RNs is critical to helping physicians develop trust and reliance in the team. The physician retains final authority over the team for cosigning orders, editing and finalizing documentation, and overseeing results management. Physicians invested in training and educating their staff will reap the rewards of a highly functioning, more satisfied team.

Encourage leadership. This can be a cultural shift for physicians, yet it is critical that they take a leadership role in this transformation.17 Physicians and their team leaders attended training sessions in team culture and change management. Prior to the go-live date, team leaders also met with the physician individually to explore their concerns and discuss ways to effectively lead and support their teams.

Continue to: Urge acceptance of support

Urge acceptance of support. The complexity of patient care today makes it difficult for a physician to manage all of a patient’s needs single-handedly. Complexity arises from the variety of plan co-pays and deductibles, the number of patients with chronic diseases, and the increased emphasis on improving quality measures.18 Enhanced support during any office visit and the extra support of an ECT for complex patients improves the ability of the physician to more effectively meet the needs of the patient.

Emphasize the benefit of an empowered team. The demands of the EHR on physicians and the resultant frustrations are well chronicled.4,19-22 Strategically delegating much of this work to other team members allows the physician to focus on the patient and perform physician-level work. At Bellin, we observed that our most successful care teams were those in which the physician fully accepted team-based care principles and empowered the staff to work at the top of their skill set.

Advanced practice clinicians

APCs in our system had traditionally practiced in 1 of 3 ways: independently handling defined panels with physician supervision; handling overflow or acute visits; or working collaboratively with a supervising physician to share a larger “team panel.” The third approach has become our preferred model. aTBC provides opportunities for APCs to thrive and collaborate with the physician to provide excellent care for patients.

APCs underwent the same process changes as physicians, including appropriate CTC support. Implementation strategies for APCs were similar to those that were useful for physicians.

Risk management professionals

At Bellin, we found that risk-management professionals had concerns about the scope of practice assigned to various team members, particularly regarding documentation. CMS allows for elements of a patient visit to be documented by CMAs and other members of the care team in real time as authorized by the physician.23,24 CTCs at Bellin also have other clinical duties in patient and EHR management. aTBC practices generally prefer the term team documentation over scribing, since it more accurately reflects the scope of the CTC’s work.

Continue to: Implementation strategies

Implementation strategies

Clarify regulatory issues. Extensive use of standing orders and protocols allowed us to increase involvement of various team members. State laws vary in what functions CMAs and LPNs are allowed to perform, so it is important to check your state guidelines.25 There is a tendency for some risk managers to overinterpret regulations. Challenge them to provide exact documentation from regulatory agencies to support their decisions.

Give assurances of physician oversight and processes. The physician assumes responsibility for standing orders, protocols, and documentation. We made sure that we had clear and consistent processes in place and worked closely with our risk managers as we developed our model. aTBC provides checks and balances to ensure accurate records, since team members are able to contribute and check for accuracy. A recent study suggested that CMAs perform documentation that is of equal or higher quality than that performed by the physician.26

Financial leadership

Like any organization adopting aTBC, Bellin’s leadership was concerned about the expense of adopting this approach. However, the leadership also recognized that the transition to aTBC could increase revenue by more than the increased staffing costs. In addition, we expected that capacity, access, continuity, and financial margins would increase.2,3,27,28 We also anticipated a decrease in downstream services, such as unnecessary tests, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations—a benefit of accountable care payment models.

Our efforts have been successful from a financial point of view. We attribute the financial sustainability that we have experienced to 4 factors:

1. Increased productivity. We knew that the increased efficiency of team-based care enables physicians to see 1 to 2 more patients per half day, and sometimes more.3,28,29 An increase of at least 1 patient visit per half-day was expected of our physicians and APCs on aTBC. In addition, they were expected to support the care team RN in achieving at least 4 billable visits per day. Our current level of RN visits is at 3.5 per nurse per day. There is significant variability in the increase of patients seen by a physician per day, ranging from 1 to 4 additional patients. These increased visits have helped us achieve financial viability, even in a predominantly fee-for-service environment.

2. More thorough service. The ability to keep patients in primary care and to focus on the patient’s full range of needs has led to higher levels of service and, consequently, to appropriately higher levels of billing codes. For example, Bellin’s revenue from billing increased by $724 per patient, related (in part) to higher rates of immunizations, cancer screenings with mammography, and colonoscopies.

Continue to: 3. New billable services

3. New billable services. Billing for RN blood pressure checks, AWVs, and extended care team services have helped make aTBC at Bellin financially feasible. Revenue from RN visits, for example, was $630,000 in 2018.

4. Improved access for patients. Of the 130 primary care providers now on aTBC, 15 (11.5%) had closed their practices to new patients before aTBC. Now, all of their practices are open to new patients, which has improved access to care. In a 2018 patient access survey, 96.6% of patients obtained an appointment as soon as they thought it was needed, compared with 70.7% of patients before the transition to aTBC.

Greater opportunity for financial sustainability. The combination of improved quality measures and decreased cost of care in the Bellin aTBC bodes well for future success in a value-based world. We have realized a significant increase in value-based payments for improved quality, and in our Next Gen Accountable Care Organization (ACO) patients, we have seen a decrease of $29 in per-member-per-month costs, likely due to the use of nonphysicians in expanded roles. In addition, hospital admissions have decreased by 5% due to the ability of ambulatory teams to manage more complex patients in the office setting. This model has also allowed physicians and APCs to increase their panel size, another key value-based metric. From 2016 to 2018, panel size for primary care providers increased by an average of 8%.

Enhanced ability to retain and recruit. Several of Bellin’s primary care recruits indicated that they had interviewed only at practices incorporating team-based care. This trend may increase as residencies transition to team-based models of care.

So how did we do?

Metrics of Bellin’s aTBC success

By the end of 2018, all 130 primary care physicians and APCs at Bellin had made the transition to this model, representing family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. We have now begun the transition of our non-primary care specialties to team-based care.

Continue to: In the aTBC model...

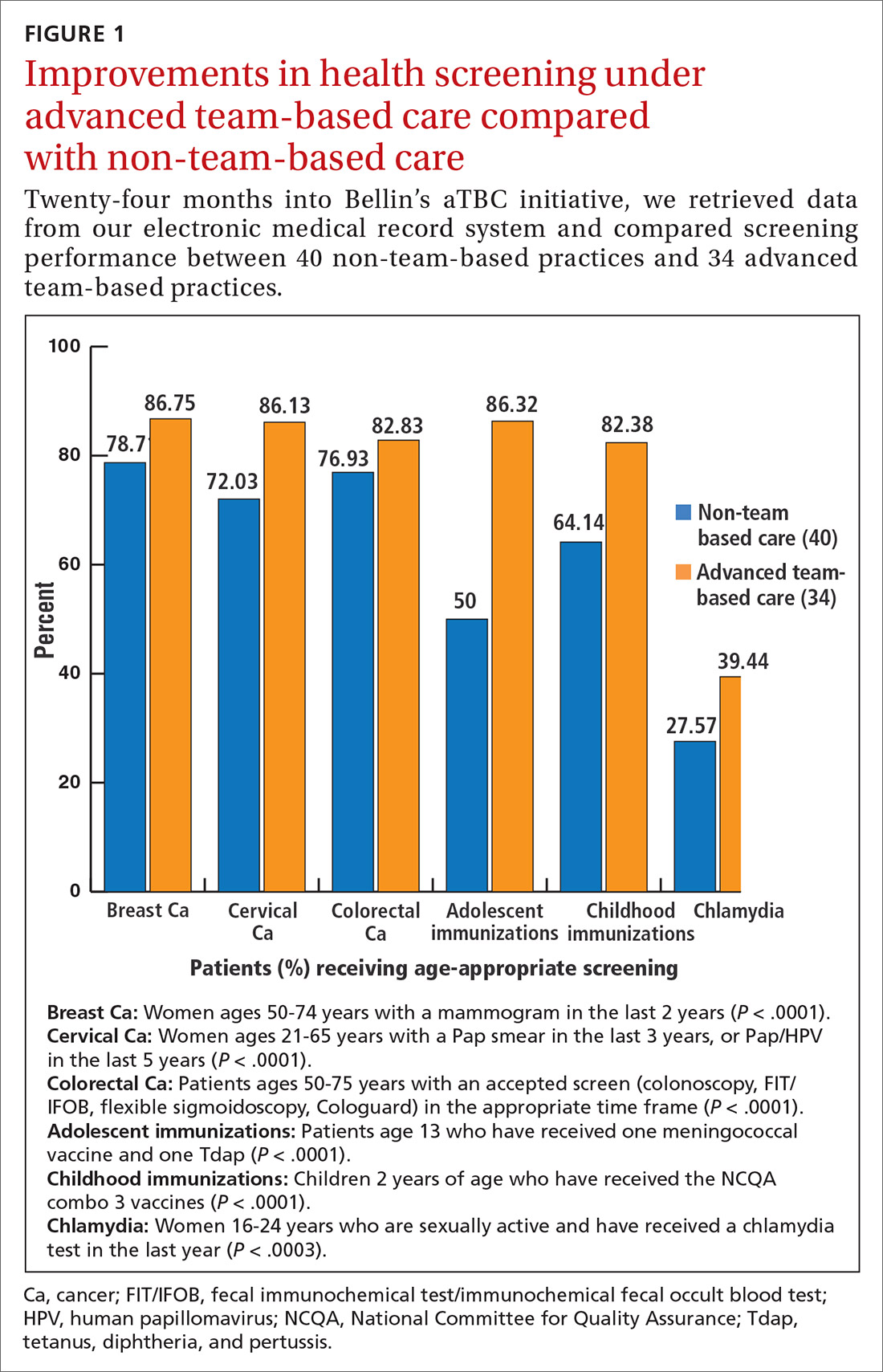

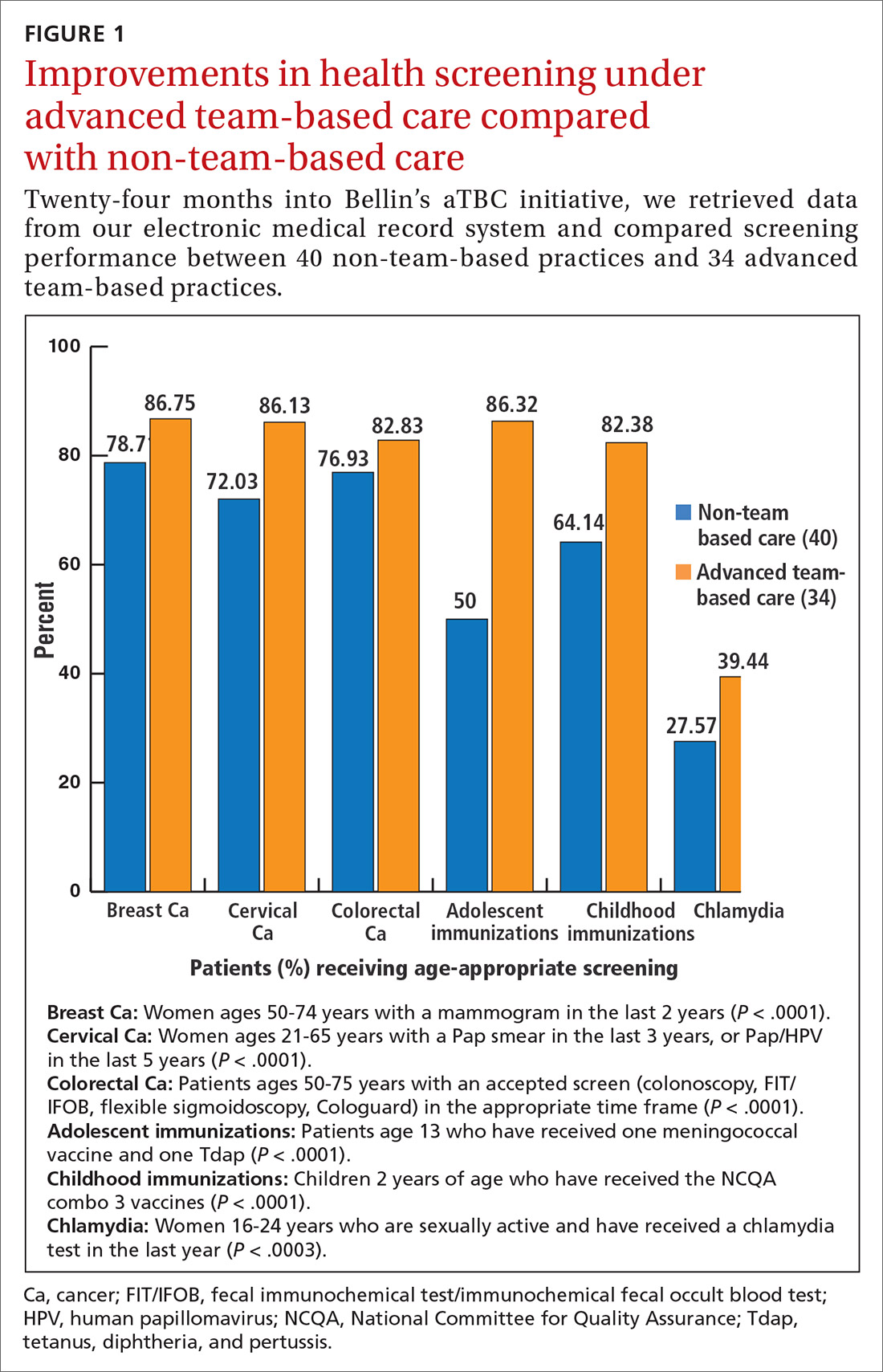

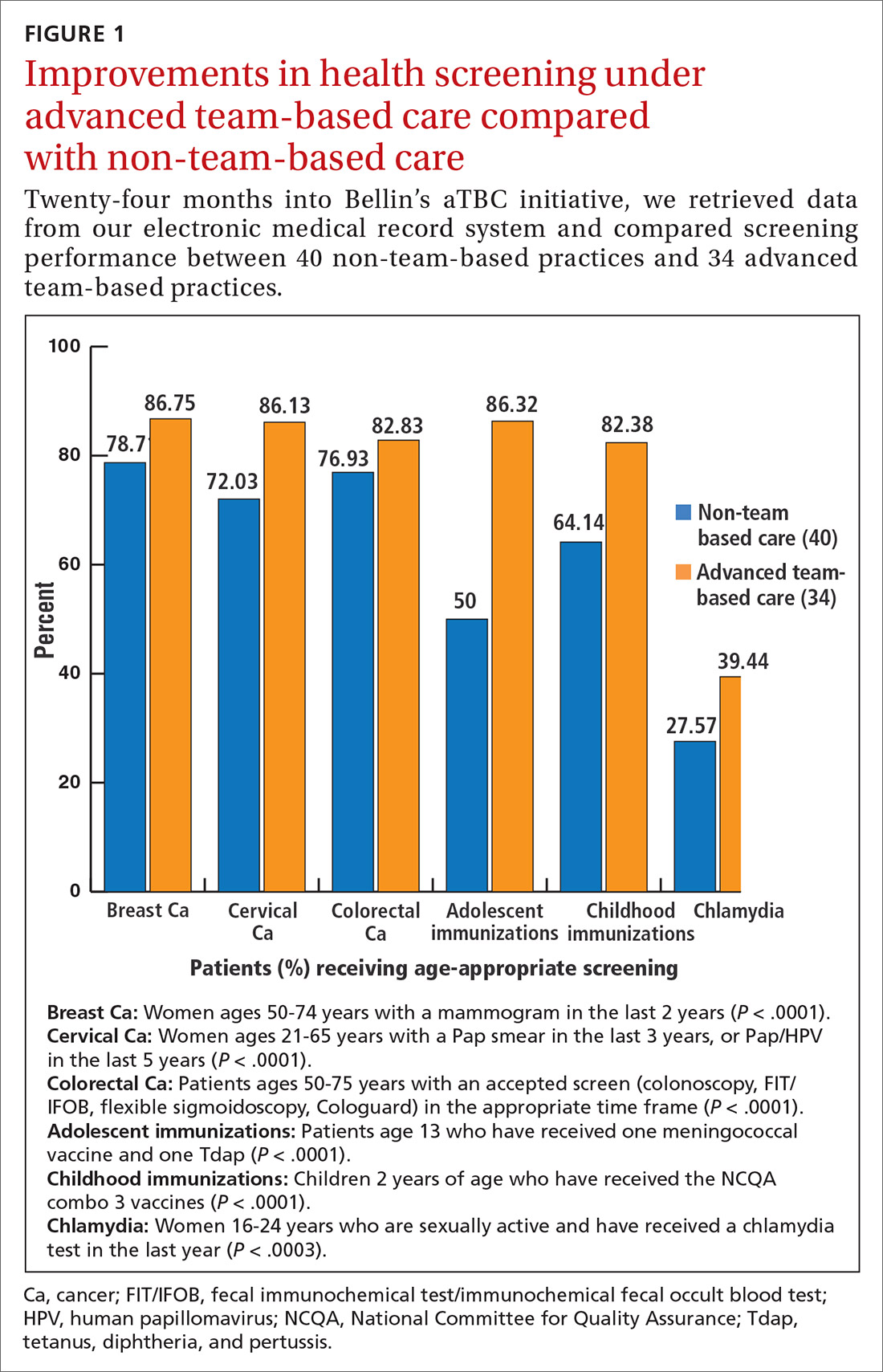

In the aTBC model, the percentage of patients receiving age-appropriate screening is higher than before in every domain we measure (FIGURE 1). There has also been improvement in major quality metrics (FIGURE 2).

In a survey done in Spring 2018 by St. Norbert College Strategic Research Center, provider satisfaction increased, with 83% of physicians having made the transition to an aTBC practice moderately or very satisfied with their Bellin Health experience, compared with 70% in the traditional model. More recent 2019 survey data show a satisfaction rate of 90% for team-based care providers. Finally, in our aTBC model—in CMS’s Next-Gen ACO initiative—the cost per patient per month is significantly less than for those in a non-team-based care model ($796 vs $940).

CORRESPONDENCE

James Jerzak, MD, 1630 Commanche Ave, Green Bay, WI 54313; james.jerzak@bellin.org.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Lindsey E. Carlasare, MBA, from the American Medical Association, and Brad Wozney, MD, Kathy Kerscher, and Christopher Elfner from Bellin Health, for their contributions to the content and review of this manuscript.

1. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

2. Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, et al. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1190-1193.

3. Hopkins K, Sinsky CA. Team-based care: saving time and improving efficiency. Fam Pract Manag. 2014;21:23-29.

4. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-760.

5. Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:422-431.

6. Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, et al. Professional satisfaction and the career plans of US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1625-1635.

7. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

8. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

9. Sinsky CA, Sinsky TA, Althaus D, et al. Practice profile. ‘Core teams’: nurse-physician partnerships provide patient-centered care at an Iowa practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:966-968.

10. Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1826-1832.

11. Association for Advancing Physician and Provider Recruitment. Schutte L. What you don’t know can cost you: building a business case for recruitment and retention best practices. 2012. https://member.aappr.org/general/custom.asp?page=696. Accessed June 20, 2019.

12. American Medical Association. AMA STEPS Forward. Expanded rooming and discharge protocols. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702600. Accessed June 20, 2019.

13. American Medical Association. AMA STEPS Forward. Team documentation. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702598?resultClick=3&bypassSolrId=J_2702598. Accessed June 20, 2019.

14. American Medical Association. AMA STEPS Forward. EHR in-basket restructuring for improved efficiency. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702694?resultClick=3&bypassSolrId=J_2702694. Accessed June 20, 2019.

15. California Health Care Foundation. Bodenheimer T, Bauer L, Olayiwola JN. RN role reimagined: how empowering registered nurses can improve primary care. https://www.chcf.org/publication/rn-role-reimagined-how-empowering-registered-nurses-can-improve-primary-care/. Accessed June 20, 2019.

16. Chung S, Lesser LI, Lauderdale DS, et al. Medicare annual preventive care visits: use increased among fee-for-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:11-20.

17. American Medical Association. AMA Policy H-160.912. The structure and function of interprofessional health care teams. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/The%20Structure%20and%20Function%20of%20Interprofessional%20Health%20Care%20Teams?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-727.xml. Accessed June 20, 2019.

18. Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Health care 2020: reengineering health care delivery to combat chronic disease. Am J Med. 2015;128:337-343.

19. Hill RG Jr, Sears LM, Melanson SW. 4000 clicks: a productivity analysis of electronic medical records in a community hospital ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1591-1594.

20. Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:e100-e106.

21. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:836-848.

22. RAND Corporation. Friedberg MW, Chen PG, Ban Busum KR, et al. Factors affecting physician professional satisfaction and their implications for patient care, health systems, and health policy. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR439.html. Accessed June 20, 2019.

23. Evaluation and Management (E/M) visit frequently asked questions (FAQs): physician fee schedule (PPS). https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/E-M-Visit-FAQs-PFS.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2019.

24. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Scribe services signature requirements. https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/2017-Transmittals-Items/R713PI.html. Accessed June 20, 2019.

25. American Association of Medical Assistants. State scope of practice laws. http://www.aama-ntl.org/employers/state-scope-of-practice-laws. Accessed June 20, 2019.

26. Misra-Hebert AD, Amah L, Rabovsky A, et al. Medical scribes: how do their notes stack up? J Fam Pract. 2016;65:155-159.

27. Arya R, Salovich DM, Ohman-Strickland P, et al. Impact of scribes on performance indicators in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17:490-494.

28. Bank AJ, Obetz C, Konrardy A, et al. Impact of scribes on patient interaction, productivity, and revenue in a cardiology clinic: a prospective study. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:399-406.

29. Anderson P, Halley MD. A new approach to making your doctor-nurse team more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2008;15:35-40.

Leaders in health care and practicing physicians recognize the need for changes in how health care is delivered.1-3 Despite this awareness, though, barriers to meaningful change persist and the current practice environment wherein physicians must routinely spend 2 hours on electronic health records (EHRs) and desk work for every hour of direct face time with patients4 is driving trainees away from ambulatory specialties and is contributing to physicians’ decisions to reduce their practices to part-time, retire early, or leave medicine altogether.5,6 Those who persevere in this environment with heavy administrative burdens run the increasing risk of burnout.7

Some physicians and practices are responding by taking creative measures to reform the way patient care is delivered. Bellin Health—a 160-provider, multispecialty health system in northeast Wisconsin where one of the authors (JJ) works—introduced an advanced team-based care (aTBC) model between November 2014 and November 2018, starting with our primary care providers. The development and introduction of this new model arose from an iterative, multidisciplinary process driven by the desire to transform the Triple Aim—enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and reducing costs—into a Quadruple Aim8 by additionally focusing on improving the work life of health care providers, which, in turn, will help achieve the first 3 goals. In introducing an aTBC model, Bellin Health focused on 3 elements: office visit redesign, in-basket management redesign, and the use of extended care team members and system and community resources to assist in the care of complex and high-risk patients.

Herein we describe the 3 components of our aTBC model,1,9 identify the barriers that existed in the minds of multiple stakeholders (from patients to clinicians and Bellin executives), and describe the strategies that enabled us to overcome these barriers.

The impetus behind our move to aTBC

Bellin Health considered a move to an aTBC model to be critical in light of factors in the health care environment, in general, and at Bellin, in particular. The factors included

- an industry-wide shift to value-based payments, which requires new models for long-term financial viability.

- recognition that physician and medical staff burnout leads to lower productivity and, in some cases, workforce losses.5,6 Replacing a physician in a practice can be difficult and expensive, with cost estimates of $500,000 to more than $1 million per physician.10,11

- a belief that aTBC could help the Bellin Health leadership team meet its organizational goals of improved patient satisfaction, achieve gains in quality measures, enhance engagement and loyalty among patients and employees, and lower recruitment costs.

A 3-part aTBC initiative

■ Part 1: Redesign the office visit

We redesigned staffing and workflow for office visits to maximize the core skills of physicians, which required distributing ancillary tasks among support staff. We up-trained certified medical assistants (CMAs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) to take on the new role of care team coordinator (CTC) and optimized the direct clinical support ratio for busier physicians. For physicians who were seeing 15 to 19 patients a day, a ratio of 3 CTCs to 2 physicians was implemented; for those seeing 20 or more patients a day, we used a support ratio of 2:1.

The role of CTC was designed so that he or she would accompany a patient throughout the entire appointment. Responsibilities were broken out as follows:

Pre-visit. Before the physician enters the room, the CTC would now perform expanded rooming functions including pending orders, refill management, care gap closure using standing orders, agenda setting, and preliminary documentation.12

Visit. The CTC would now hand off the patient to the physician and stay in the room to document details of the visit and record new orders for consults, x-ray films, referrals, or prescriptions.13 This intensive EHR support was established to ensure that the physician could focus directly on the patient without the distraction of the computer.

Continue to: Post-visit

Post-visit. After a physician leaves a room, the CTC was now charged with finishing the pending orders, setting up the patient’s next appointment and pre-visit labs, reviewing details of the after-visit summary, and doing any basic health coaching with the patient. During this time, the physician would use the co-location space to review and edit the documentation, cosign the orders and prescriptions submitted by the CTC, and close the chart before going into the next room with the second CTC. The need to revisit these details after clinic hours was eliminated.

Another change … The role of our phone triage registered nurses (RN) was expanded. Care team RNs began providing diabetes counseling, blood pressure checks, annual wellness visits (AWV), and follow-up through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)'s Chronic Care Management and Transitional Care Management programs.

■ Part 2: Redesign between-visit in-basket management

Responding to an increasing number of inbox messages had become overwhelming for our physicians. Bellin Health’s management was aware that strategic delegation of inbox messages could save an hour or more of a physician’s time each day.14 Bellin implemented a procedure whereby inbox test results would be handled by the same CTC who saw the patient, thereby extending continuity. If the results were normal, the CTC would contact the patient. If the results were abnormal, the physician and the CTC would discuss them and develop a plan. Co-location of the RN, the CTC, and the physician would leverage face-to-face communication and make in-basket management more efficient.

■ Part 3: Redesign population health management

We developed an Extended Care Team (ECT), including social workers, clinical pharmacists, RN care coordinators, and diabetes educators, to assist with the care of patients with high-risk disorders or otherwise complex issues. These team members would work closely with the CTC, care team RN, and physician to review patients, develop plans of care, optimize management, and improve outcomes. Patients would be identified as candidates for potential ECT involvement based on the physician’s judgment in consultation with an EHR-based risk score for hospitalization or emergency department visit.

As we developed new processes, such as screening for determinants of health, we engaged additional system and community resources to help meet the needs of our patients.

Continue to: A look at stakeholder concerns and overcoming the barriers

A look at stakeholder concerns and overcoming the barriers

Critical to our success was being attentive to the concerns of our stakeholders and addressing them. Along the way, we gained valuable implementation insights, which we share here along with some specifics about how, exactly, we did things at Bellin.

Patients

Some patients expressed hesitation at having a person other than their physician in the exam room. They worried that the intimacy and privacy with their physician would be lost. In light of this, we gave patients the option not to have the CTC remain in the room. However, patients quickly saw the value of this team-based care approach and seldom asked to be seen without the CTC.

Throughout the process, we surveyed patients for feedback on their experiences. Comments indicated that the presence of the CTC in our team-based model led to positive patient experiences:

My physician is fully attentive. Patients appreciated that physicians were not distracted by the computer in the exam room. “I feel like I’ve got my doctor back” has been a common refrain.

The office staff is more responsive. The CTC, having been present during the appointment, has a deeper understanding of the care plan and can respond to calls or emails between visits, thereby reducing the time patients must wait for answers. One patient commented that, “I love [the doctor’s] team; his nurses are willing to answer every question I have.”

Continue to: I increasingly feel that I'm understood

I increasingly feel that I’m understood. We have seen patients develop meaningful relationships with other team members, confiding in them in ways that they hadn’t always done with physicians and advanced practice clinicians (APCs). Team members, in turn, have added valuable insights that help optimize patients’ care. In particular, the care of patients with multiple needs has been enhanced with the addition of ECT members who work with the core team and use their expertise to optimize the care of these patients.

Certified medical assistants and licensed practical nurses

Bellin’s leadership knew that team documentation could cause stress for the CMA, who, acting as a CTC, wanted to avoid misrepresenting details of the clinical encounter.13 Adding to the stress were other duties that would need to be learned, including agenda setting, refill management, care gap closure, and health coaching. With thorough training and preparation, many—but not all—of our CMAs and LPNs were able to successfully make the transition and flourish.

Implementation strategies

Provide thorough training. Our training process started 8 weeks before it was time to “go live.” There were weekly hour-long training sessions in population health basics, team culture and change management, documentation basics, and new roles and responsibilities. In the final week, the entire aTBC team sat together for 3 days of EHR training. All new teams shadowed existing teams to get a clear picture of the new processes.

Create a community of support. As our CMAs adapted to their new CTC roles, it was critical that they had support from experienced CTCs. Encouragement and patience from physicians were—and are—essential for CTCs to develop confidence in their new roles.

Enable ongoing feedback. We introduced weekly team meetings to enhance team communication and dynamics. Forums for all roles are held periodically to facilitate discussion, share learning, and enable support between teams.

Continue to: Use EHR tools to facilitate this work

Use EHR tools to facilitate this work. Using standard templates and documentation tools helped CTCs develop the confidence needed to thrive in their new role. Knowing these tools were available helped CTCs become effective in helping the team manage the between-visit work.

Monitor workload. As we developed more workflows and processes, we took care to monitor the amount of additional work for those in this role. We offloaded work whenever possible. For example, coordinated refill management at time of service, coupled with a back-up centralized refill system, can significantly decrease the number of refill requests made to CTCs. We continue to adjust staffing, where appropriate, to provide adequate support for those in this valuable role.

Be prepared for turnover. As CTCs became empowered in their new roles, some decided to advance their training into other roles. We developed a plan for replacing and training new staff. Higher pay can also be used to help attract and retain these staff members. Bellin uses LPNs in this role to ensure adequate staffing. Other health systems have developed a tier system for CMAs to improve retention.

Registered nurses

Before our move to an aTBC model, our office RNs primarily managed phone triage. Now the nurses were enlisted to play a more active role in patient care and team leadership. Although it was a dramatic departure from prior responsibilities, the majority of Bellin’s RNs have found increased satisfaction in taking on direct patient care.

Implementation strategies

Define new roles and provide training. In addition to participating in acute patient visits, consider ways that care team RNs can expand responsibilities as they pertain to disease counseling, population health management, and team leadership.15 At Bellin, the expanded role of the RN is evident in diabetes education and Medicare AWVs. Specifically, RNs now provide diabetes education to appropriate patients following a warm handoff from the physician at the time of the visit. RNs now also complete Medicare AWVs, which frees up physicians for other tasks and helps ensure sustainability for the new RN roles. Rates of completed AWVs at Bellin are now more than 70%, compared with reported national rates of less than 30%.16

Continue to: Maximize co-location

Maximize co-location. It is helpful to have the team members whose work is closely related—such as the CTCs and the RN for the team—to be situated near each other, rather than down a hall or in separate offices. Since the RN is co-located with the core teams at Bellin, there is now greater opportunity for verbal interaction, rather than just electronic communications, for matters such as triage calls and results management. RNs also provide a valuable resource for CMAs and LPNs, as well as help oversee team management of the in-basket.

Evaluate sustainability. Additional roles for the RNs required additional RN staffing. We assessed the new workload duties and balanced that against potential revenue from RN visits. This analysis indicated that an optimal ratio was 1 RN to every 3000 patients. This would allow an adequate number of RNs to fulfill additional roles and was financially sustainable with the goal of 4 billable RN visits per day.

Physicians

Bellin’s leadership recognized that some physicians might perceive team-based care as eroding their primary responsibility for patients’ care. Physicians have historically been trained in a model based on the primacy of the individual physician and that can be a hurdle to embracing team culture as a new paradigm of care. Several strategies helped us and can help others, too.

Implementation strategies

Cultivate trust. Thorough training of CTCs and RNs is critical to helping physicians develop trust and reliance in the team. The physician retains final authority over the team for cosigning orders, editing and finalizing documentation, and overseeing results management. Physicians invested in training and educating their staff will reap the rewards of a highly functioning, more satisfied team.

Encourage leadership. This can be a cultural shift for physicians, yet it is critical that they take a leadership role in this transformation.17 Physicians and their team leaders attended training sessions in team culture and change management. Prior to the go-live date, team leaders also met with the physician individually to explore their concerns and discuss ways to effectively lead and support their teams.

Continue to: Urge acceptance of support

Urge acceptance of support. The complexity of patient care today makes it difficult for a physician to manage all of a patient’s needs single-handedly. Complexity arises from the variety of plan co-pays and deductibles, the number of patients with chronic diseases, and the increased emphasis on improving quality measures.18 Enhanced support during any office visit and the extra support of an ECT for complex patients improves the ability of the physician to more effectively meet the needs of the patient.

Emphasize the benefit of an empowered team. The demands of the EHR on physicians and the resultant frustrations are well chronicled.4,19-22 Strategically delegating much of this work to other team members allows the physician to focus on the patient and perform physician-level work. At Bellin, we observed that our most successful care teams were those in which the physician fully accepted team-based care principles and empowered the staff to work at the top of their skill set.

Advanced practice clinicians

APCs in our system had traditionally practiced in 1 of 3 ways: independently handling defined panels with physician supervision; handling overflow or acute visits; or working collaboratively with a supervising physician to share a larger “team panel.” The third approach has become our preferred model. aTBC provides opportunities for APCs to thrive and collaborate with the physician to provide excellent care for patients.

APCs underwent the same process changes as physicians, including appropriate CTC support. Implementation strategies for APCs were similar to those that were useful for physicians.

Risk management professionals

At Bellin, we found that risk-management professionals had concerns about the scope of practice assigned to various team members, particularly regarding documentation. CMS allows for elements of a patient visit to be documented by CMAs and other members of the care team in real time as authorized by the physician.23,24 CTCs at Bellin also have other clinical duties in patient and EHR management. aTBC practices generally prefer the term team documentation over scribing, since it more accurately reflects the scope of the CTC’s work.

Continue to: Implementation strategies

Implementation strategies

Clarify regulatory issues. Extensive use of standing orders and protocols allowed us to increase involvement of various team members. State laws vary in what functions CMAs and LPNs are allowed to perform, so it is important to check your state guidelines.25 There is a tendency for some risk managers to overinterpret regulations. Challenge them to provide exact documentation from regulatory agencies to support their decisions.

Give assurances of physician oversight and processes. The physician assumes responsibility for standing orders, protocols, and documentation. We made sure that we had clear and consistent processes in place and worked closely with our risk managers as we developed our model. aTBC provides checks and balances to ensure accurate records, since team members are able to contribute and check for accuracy. A recent study suggested that CMAs perform documentation that is of equal or higher quality than that performed by the physician.26

Financial leadership

Like any organization adopting aTBC, Bellin’s leadership was concerned about the expense of adopting this approach. However, the leadership also recognized that the transition to aTBC could increase revenue by more than the increased staffing costs. In addition, we expected that capacity, access, continuity, and financial margins would increase.2,3,27,28 We also anticipated a decrease in downstream services, such as unnecessary tests, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations—a benefit of accountable care payment models.

Our efforts have been successful from a financial point of view. We attribute the financial sustainability that we have experienced to 4 factors:

1. Increased productivity. We knew that the increased efficiency of team-based care enables physicians to see 1 to 2 more patients per half day, and sometimes more.3,28,29 An increase of at least 1 patient visit per half-day was expected of our physicians and APCs on aTBC. In addition, they were expected to support the care team RN in achieving at least 4 billable visits per day. Our current level of RN visits is at 3.5 per nurse per day. There is significant variability in the increase of patients seen by a physician per day, ranging from 1 to 4 additional patients. These increased visits have helped us achieve financial viability, even in a predominantly fee-for-service environment.

2. More thorough service. The ability to keep patients in primary care and to focus on the patient’s full range of needs has led to higher levels of service and, consequently, to appropriately higher levels of billing codes. For example, Bellin’s revenue from billing increased by $724 per patient, related (in part) to higher rates of immunizations, cancer screenings with mammography, and colonoscopies.

Continue to: 3. New billable services

3. New billable services. Billing for RN blood pressure checks, AWVs, and extended care team services have helped make aTBC at Bellin financially feasible. Revenue from RN visits, for example, was $630,000 in 2018.

4. Improved access for patients. Of the 130 primary care providers now on aTBC, 15 (11.5%) had closed their practices to new patients before aTBC. Now, all of their practices are open to new patients, which has improved access to care. In a 2018 patient access survey, 96.6% of patients obtained an appointment as soon as they thought it was needed, compared with 70.7% of patients before the transition to aTBC.

Greater opportunity for financial sustainability. The combination of improved quality measures and decreased cost of care in the Bellin aTBC bodes well for future success in a value-based world. We have realized a significant increase in value-based payments for improved quality, and in our Next Gen Accountable Care Organization (ACO) patients, we have seen a decrease of $29 in per-member-per-month costs, likely due to the use of nonphysicians in expanded roles. In addition, hospital admissions have decreased by 5% due to the ability of ambulatory teams to manage more complex patients in the office setting. This model has also allowed physicians and APCs to increase their panel size, another key value-based metric. From 2016 to 2018, panel size for primary care providers increased by an average of 8%.

Enhanced ability to retain and recruit. Several of Bellin’s primary care recruits indicated that they had interviewed only at practices incorporating team-based care. This trend may increase as residencies transition to team-based models of care.

So how did we do?

Metrics of Bellin’s aTBC success

By the end of 2018, all 130 primary care physicians and APCs at Bellin had made the transition to this model, representing family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. We have now begun the transition of our non-primary care specialties to team-based care.

Continue to: In the aTBC model...

In the aTBC model, the percentage of patients receiving age-appropriate screening is higher than before in every domain we measure (FIGURE 1). There has also been improvement in major quality metrics (FIGURE 2).

In a survey done in Spring 2018 by St. Norbert College Strategic Research Center, provider satisfaction increased, with 83% of physicians having made the transition to an aTBC practice moderately or very satisfied with their Bellin Health experience, compared with 70% in the traditional model. More recent 2019 survey data show a satisfaction rate of 90% for team-based care providers. Finally, in our aTBC model—in CMS’s Next-Gen ACO initiative—the cost per patient per month is significantly less than for those in a non-team-based care model ($796 vs $940).

CORRESPONDENCE

James Jerzak, MD, 1630 Commanche Ave, Green Bay, WI 54313; james.jerzak@bellin.org.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Lindsey E. Carlasare, MBA, from the American Medical Association, and Brad Wozney, MD, Kathy Kerscher, and Christopher Elfner from Bellin Health, for their contributions to the content and review of this manuscript.

Leaders in health care and practicing physicians recognize the need for changes in how health care is delivered.1-3 Despite this awareness, though, barriers to meaningful change persist and the current practice environment wherein physicians must routinely spend 2 hours on electronic health records (EHRs) and desk work for every hour of direct face time with patients4 is driving trainees away from ambulatory specialties and is contributing to physicians’ decisions to reduce their practices to part-time, retire early, or leave medicine altogether.5,6 Those who persevere in this environment with heavy administrative burdens run the increasing risk of burnout.7

Some physicians and practices are responding by taking creative measures to reform the way patient care is delivered. Bellin Health—a 160-provider, multispecialty health system in northeast Wisconsin where one of the authors (JJ) works—introduced an advanced team-based care (aTBC) model between November 2014 and November 2018, starting with our primary care providers. The development and introduction of this new model arose from an iterative, multidisciplinary process driven by the desire to transform the Triple Aim—enhancing patient experience, improving population health, and reducing costs—into a Quadruple Aim8 by additionally focusing on improving the work life of health care providers, which, in turn, will help achieve the first 3 goals. In introducing an aTBC model, Bellin Health focused on 3 elements: office visit redesign, in-basket management redesign, and the use of extended care team members and system and community resources to assist in the care of complex and high-risk patients.

Herein we describe the 3 components of our aTBC model,1,9 identify the barriers that existed in the minds of multiple stakeholders (from patients to clinicians and Bellin executives), and describe the strategies that enabled us to overcome these barriers.

The impetus behind our move to aTBC

Bellin Health considered a move to an aTBC model to be critical in light of factors in the health care environment, in general, and at Bellin, in particular. The factors included

- an industry-wide shift to value-based payments, which requires new models for long-term financial viability.

- recognition that physician and medical staff burnout leads to lower productivity and, in some cases, workforce losses.5,6 Replacing a physician in a practice can be difficult and expensive, with cost estimates of $500,000 to more than $1 million per physician.10,11

- a belief that aTBC could help the Bellin Health leadership team meet its organizational goals of improved patient satisfaction, achieve gains in quality measures, enhance engagement and loyalty among patients and employees, and lower recruitment costs.

A 3-part aTBC initiative

■ Part 1: Redesign the office visit

We redesigned staffing and workflow for office visits to maximize the core skills of physicians, which required distributing ancillary tasks among support staff. We up-trained certified medical assistants (CMAs) and licensed practical nurses (LPNs) to take on the new role of care team coordinator (CTC) and optimized the direct clinical support ratio for busier physicians. For physicians who were seeing 15 to 19 patients a day, a ratio of 3 CTCs to 2 physicians was implemented; for those seeing 20 or more patients a day, we used a support ratio of 2:1.

The role of CTC was designed so that he or she would accompany a patient throughout the entire appointment. Responsibilities were broken out as follows:

Pre-visit. Before the physician enters the room, the CTC would now perform expanded rooming functions including pending orders, refill management, care gap closure using standing orders, agenda setting, and preliminary documentation.12

Visit. The CTC would now hand off the patient to the physician and stay in the room to document details of the visit and record new orders for consults, x-ray films, referrals, or prescriptions.13 This intensive EHR support was established to ensure that the physician could focus directly on the patient without the distraction of the computer.

Continue to: Post-visit

Post-visit. After a physician leaves a room, the CTC was now charged with finishing the pending orders, setting up the patient’s next appointment and pre-visit labs, reviewing details of the after-visit summary, and doing any basic health coaching with the patient. During this time, the physician would use the co-location space to review and edit the documentation, cosign the orders and prescriptions submitted by the CTC, and close the chart before going into the next room with the second CTC. The need to revisit these details after clinic hours was eliminated.

Another change … The role of our phone triage registered nurses (RN) was expanded. Care team RNs began providing diabetes counseling, blood pressure checks, annual wellness visits (AWV), and follow-up through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS)'s Chronic Care Management and Transitional Care Management programs.

■ Part 2: Redesign between-visit in-basket management

Responding to an increasing number of inbox messages had become overwhelming for our physicians. Bellin Health’s management was aware that strategic delegation of inbox messages could save an hour or more of a physician’s time each day.14 Bellin implemented a procedure whereby inbox test results would be handled by the same CTC who saw the patient, thereby extending continuity. If the results were normal, the CTC would contact the patient. If the results were abnormal, the physician and the CTC would discuss them and develop a plan. Co-location of the RN, the CTC, and the physician would leverage face-to-face communication and make in-basket management more efficient.

■ Part 3: Redesign population health management

We developed an Extended Care Team (ECT), including social workers, clinical pharmacists, RN care coordinators, and diabetes educators, to assist with the care of patients with high-risk disorders or otherwise complex issues. These team members would work closely with the CTC, care team RN, and physician to review patients, develop plans of care, optimize management, and improve outcomes. Patients would be identified as candidates for potential ECT involvement based on the physician’s judgment in consultation with an EHR-based risk score for hospitalization or emergency department visit.

As we developed new processes, such as screening for determinants of health, we engaged additional system and community resources to help meet the needs of our patients.

Continue to: A look at stakeholder concerns and overcoming the barriers

A look at stakeholder concerns and overcoming the barriers

Critical to our success was being attentive to the concerns of our stakeholders and addressing them. Along the way, we gained valuable implementation insights, which we share here along with some specifics about how, exactly, we did things at Bellin.

Patients

Some patients expressed hesitation at having a person other than their physician in the exam room. They worried that the intimacy and privacy with their physician would be lost. In light of this, we gave patients the option not to have the CTC remain in the room. However, patients quickly saw the value of this team-based care approach and seldom asked to be seen without the CTC.

Throughout the process, we surveyed patients for feedback on their experiences. Comments indicated that the presence of the CTC in our team-based model led to positive patient experiences:

My physician is fully attentive. Patients appreciated that physicians were not distracted by the computer in the exam room. “I feel like I’ve got my doctor back” has been a common refrain.

The office staff is more responsive. The CTC, having been present during the appointment, has a deeper understanding of the care plan and can respond to calls or emails between visits, thereby reducing the time patients must wait for answers. One patient commented that, “I love [the doctor’s] team; his nurses are willing to answer every question I have.”

Continue to: I increasingly feel that I'm understood

I increasingly feel that I’m understood. We have seen patients develop meaningful relationships with other team members, confiding in them in ways that they hadn’t always done with physicians and advanced practice clinicians (APCs). Team members, in turn, have added valuable insights that help optimize patients’ care. In particular, the care of patients with multiple needs has been enhanced with the addition of ECT members who work with the core team and use their expertise to optimize the care of these patients.

Certified medical assistants and licensed practical nurses

Bellin’s leadership knew that team documentation could cause stress for the CMA, who, acting as a CTC, wanted to avoid misrepresenting details of the clinical encounter.13 Adding to the stress were other duties that would need to be learned, including agenda setting, refill management, care gap closure, and health coaching. With thorough training and preparation, many—but not all—of our CMAs and LPNs were able to successfully make the transition and flourish.

Implementation strategies

Provide thorough training. Our training process started 8 weeks before it was time to “go live.” There were weekly hour-long training sessions in population health basics, team culture and change management, documentation basics, and new roles and responsibilities. In the final week, the entire aTBC team sat together for 3 days of EHR training. All new teams shadowed existing teams to get a clear picture of the new processes.

Create a community of support. As our CMAs adapted to their new CTC roles, it was critical that they had support from experienced CTCs. Encouragement and patience from physicians were—and are—essential for CTCs to develop confidence in their new roles.

Enable ongoing feedback. We introduced weekly team meetings to enhance team communication and dynamics. Forums for all roles are held periodically to facilitate discussion, share learning, and enable support between teams.

Continue to: Use EHR tools to facilitate this work

Use EHR tools to facilitate this work. Using standard templates and documentation tools helped CTCs develop the confidence needed to thrive in their new role. Knowing these tools were available helped CTCs become effective in helping the team manage the between-visit work.

Monitor workload. As we developed more workflows and processes, we took care to monitor the amount of additional work for those in this role. We offloaded work whenever possible. For example, coordinated refill management at time of service, coupled with a back-up centralized refill system, can significantly decrease the number of refill requests made to CTCs. We continue to adjust staffing, where appropriate, to provide adequate support for those in this valuable role.

Be prepared for turnover. As CTCs became empowered in their new roles, some decided to advance their training into other roles. We developed a plan for replacing and training new staff. Higher pay can also be used to help attract and retain these staff members. Bellin uses LPNs in this role to ensure adequate staffing. Other health systems have developed a tier system for CMAs to improve retention.

Registered nurses

Before our move to an aTBC model, our office RNs primarily managed phone triage. Now the nurses were enlisted to play a more active role in patient care and team leadership. Although it was a dramatic departure from prior responsibilities, the majority of Bellin’s RNs have found increased satisfaction in taking on direct patient care.

Implementation strategies

Define new roles and provide training. In addition to participating in acute patient visits, consider ways that care team RNs can expand responsibilities as they pertain to disease counseling, population health management, and team leadership.15 At Bellin, the expanded role of the RN is evident in diabetes education and Medicare AWVs. Specifically, RNs now provide diabetes education to appropriate patients following a warm handoff from the physician at the time of the visit. RNs now also complete Medicare AWVs, which frees up physicians for other tasks and helps ensure sustainability for the new RN roles. Rates of completed AWVs at Bellin are now more than 70%, compared with reported national rates of less than 30%.16

Continue to: Maximize co-location

Maximize co-location. It is helpful to have the team members whose work is closely related—such as the CTCs and the RN for the team—to be situated near each other, rather than down a hall or in separate offices. Since the RN is co-located with the core teams at Bellin, there is now greater opportunity for verbal interaction, rather than just electronic communications, for matters such as triage calls and results management. RNs also provide a valuable resource for CMAs and LPNs, as well as help oversee team management of the in-basket.

Evaluate sustainability. Additional roles for the RNs required additional RN staffing. We assessed the new workload duties and balanced that against potential revenue from RN visits. This analysis indicated that an optimal ratio was 1 RN to every 3000 patients. This would allow an adequate number of RNs to fulfill additional roles and was financially sustainable with the goal of 4 billable RN visits per day.

Physicians

Bellin’s leadership recognized that some physicians might perceive team-based care as eroding their primary responsibility for patients’ care. Physicians have historically been trained in a model based on the primacy of the individual physician and that can be a hurdle to embracing team culture as a new paradigm of care. Several strategies helped us and can help others, too.

Implementation strategies

Cultivate trust. Thorough training of CTCs and RNs is critical to helping physicians develop trust and reliance in the team. The physician retains final authority over the team for cosigning orders, editing and finalizing documentation, and overseeing results management. Physicians invested in training and educating their staff will reap the rewards of a highly functioning, more satisfied team.

Encourage leadership. This can be a cultural shift for physicians, yet it is critical that they take a leadership role in this transformation.17 Physicians and their team leaders attended training sessions in team culture and change management. Prior to the go-live date, team leaders also met with the physician individually to explore their concerns and discuss ways to effectively lead and support their teams.

Continue to: Urge acceptance of support

Urge acceptance of support. The complexity of patient care today makes it difficult for a physician to manage all of a patient’s needs single-handedly. Complexity arises from the variety of plan co-pays and deductibles, the number of patients with chronic diseases, and the increased emphasis on improving quality measures.18 Enhanced support during any office visit and the extra support of an ECT for complex patients improves the ability of the physician to more effectively meet the needs of the patient.

Emphasize the benefit of an empowered team. The demands of the EHR on physicians and the resultant frustrations are well chronicled.4,19-22 Strategically delegating much of this work to other team members allows the physician to focus on the patient and perform physician-level work. At Bellin, we observed that our most successful care teams were those in which the physician fully accepted team-based care principles and empowered the staff to work at the top of their skill set.

Advanced practice clinicians

APCs in our system had traditionally practiced in 1 of 3 ways: independently handling defined panels with physician supervision; handling overflow or acute visits; or working collaboratively with a supervising physician to share a larger “team panel.” The third approach has become our preferred model. aTBC provides opportunities for APCs to thrive and collaborate with the physician to provide excellent care for patients.

APCs underwent the same process changes as physicians, including appropriate CTC support. Implementation strategies for APCs were similar to those that were useful for physicians.

Risk management professionals

At Bellin, we found that risk-management professionals had concerns about the scope of practice assigned to various team members, particularly regarding documentation. CMS allows for elements of a patient visit to be documented by CMAs and other members of the care team in real time as authorized by the physician.23,24 CTCs at Bellin also have other clinical duties in patient and EHR management. aTBC practices generally prefer the term team documentation over scribing, since it more accurately reflects the scope of the CTC’s work.

Continue to: Implementation strategies

Implementation strategies

Clarify regulatory issues. Extensive use of standing orders and protocols allowed us to increase involvement of various team members. State laws vary in what functions CMAs and LPNs are allowed to perform, so it is important to check your state guidelines.25 There is a tendency for some risk managers to overinterpret regulations. Challenge them to provide exact documentation from regulatory agencies to support their decisions.

Give assurances of physician oversight and processes. The physician assumes responsibility for standing orders, protocols, and documentation. We made sure that we had clear and consistent processes in place and worked closely with our risk managers as we developed our model. aTBC provides checks and balances to ensure accurate records, since team members are able to contribute and check for accuracy. A recent study suggested that CMAs perform documentation that is of equal or higher quality than that performed by the physician.26

Financial leadership

Like any organization adopting aTBC, Bellin’s leadership was concerned about the expense of adopting this approach. However, the leadership also recognized that the transition to aTBC could increase revenue by more than the increased staffing costs. In addition, we expected that capacity, access, continuity, and financial margins would increase.2,3,27,28 We also anticipated a decrease in downstream services, such as unnecessary tests, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations—a benefit of accountable care payment models.

Our efforts have been successful from a financial point of view. We attribute the financial sustainability that we have experienced to 4 factors:

1. Increased productivity. We knew that the increased efficiency of team-based care enables physicians to see 1 to 2 more patients per half day, and sometimes more.3,28,29 An increase of at least 1 patient visit per half-day was expected of our physicians and APCs on aTBC. In addition, they were expected to support the care team RN in achieving at least 4 billable visits per day. Our current level of RN visits is at 3.5 per nurse per day. There is significant variability in the increase of patients seen by a physician per day, ranging from 1 to 4 additional patients. These increased visits have helped us achieve financial viability, even in a predominantly fee-for-service environment.

2. More thorough service. The ability to keep patients in primary care and to focus on the patient’s full range of needs has led to higher levels of service and, consequently, to appropriately higher levels of billing codes. For example, Bellin’s revenue from billing increased by $724 per patient, related (in part) to higher rates of immunizations, cancer screenings with mammography, and colonoscopies.

Continue to: 3. New billable services

3. New billable services. Billing for RN blood pressure checks, AWVs, and extended care team services have helped make aTBC at Bellin financially feasible. Revenue from RN visits, for example, was $630,000 in 2018.

4. Improved access for patients. Of the 130 primary care providers now on aTBC, 15 (11.5%) had closed their practices to new patients before aTBC. Now, all of their practices are open to new patients, which has improved access to care. In a 2018 patient access survey, 96.6% of patients obtained an appointment as soon as they thought it was needed, compared with 70.7% of patients before the transition to aTBC.

Greater opportunity for financial sustainability. The combination of improved quality measures and decreased cost of care in the Bellin aTBC bodes well for future success in a value-based world. We have realized a significant increase in value-based payments for improved quality, and in our Next Gen Accountable Care Organization (ACO) patients, we have seen a decrease of $29 in per-member-per-month costs, likely due to the use of nonphysicians in expanded roles. In addition, hospital admissions have decreased by 5% due to the ability of ambulatory teams to manage more complex patients in the office setting. This model has also allowed physicians and APCs to increase their panel size, another key value-based metric. From 2016 to 2018, panel size for primary care providers increased by an average of 8%.

Enhanced ability to retain and recruit. Several of Bellin’s primary care recruits indicated that they had interviewed only at practices incorporating team-based care. This trend may increase as residencies transition to team-based models of care.

So how did we do?

Metrics of Bellin’s aTBC success

By the end of 2018, all 130 primary care physicians and APCs at Bellin had made the transition to this model, representing family medicine, internal medicine, and pediatrics. We have now begun the transition of our non-primary care specialties to team-based care.

Continue to: In the aTBC model...

In the aTBC model, the percentage of patients receiving age-appropriate screening is higher than before in every domain we measure (FIGURE 1). There has also been improvement in major quality metrics (FIGURE 2).

In a survey done in Spring 2018 by St. Norbert College Strategic Research Center, provider satisfaction increased, with 83% of physicians having made the transition to an aTBC practice moderately or very satisfied with their Bellin Health experience, compared with 70% in the traditional model. More recent 2019 survey data show a satisfaction rate of 90% for team-based care providers. Finally, in our aTBC model—in CMS’s Next-Gen ACO initiative—the cost per patient per month is significantly less than for those in a non-team-based care model ($796 vs $940).

CORRESPONDENCE

James Jerzak, MD, 1630 Commanche Ave, Green Bay, WI 54313; james.jerzak@bellin.org.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Lindsey E. Carlasare, MBA, from the American Medical Association, and Brad Wozney, MD, Kathy Kerscher, and Christopher Elfner from Bellin Health, for their contributions to the content and review of this manuscript.

1. Sinsky CA, Willard-Grace R, Schutzbank AM, et al. In search of joy in practice: a report of 23 high-functioning primary care practices. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:272-278.

2. Reuben DB, Knudsen J, Senelick W, et al. The effect of a physician partner program on physician efficiency and patient satisfaction. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1190-1193.

3. Hopkins K, Sinsky CA. Team-based care: saving time and improving efficiency. Fam Pract Manag. 2014;21:23-29.

4. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-760.

5. Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:422-431.

6. Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, West CP, et al. Professional satisfaction and the career plans of US physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1625-1635.

7. Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1600-1613.

8. Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573-576.

9. Sinsky CA, Sinsky TA, Althaus D, et al. Practice profile. ‘Core teams’: nurse-physician partnerships provide patient-centered care at an Iowa practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:966-968.

10. Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1826-1832.

11. Association for Advancing Physician and Provider Recruitment. Schutte L. What you don’t know can cost you: building a business case for recruitment and retention best practices. 2012. https://member.aappr.org/general/custom.asp?page=696. Accessed June 20, 2019.

12. American Medical Association. AMA STEPS Forward. Expanded rooming and discharge protocols. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702600. Accessed June 20, 2019.

13. American Medical Association. AMA STEPS Forward. Team documentation. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702598?resultClick=3&bypassSolrId=J_2702598. Accessed June 20, 2019.

14. American Medical Association. AMA STEPS Forward. EHR in-basket restructuring for improved efficiency. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/module/2702694?resultClick=3&bypassSolrId=J_2702694. Accessed June 20, 2019.

15. California Health Care Foundation. Bodenheimer T, Bauer L, Olayiwola JN. RN role reimagined: how empowering registered nurses can improve primary care. https://www.chcf.org/publication/rn-role-reimagined-how-empowering-registered-nurses-can-improve-primary-care/. Accessed June 20, 2019.

16. Chung S, Lesser LI, Lauderdale DS, et al. Medicare annual preventive care visits: use increased among fee-for-service patients, but many do not participate. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34:11-20.

17. American Medical Association. AMA Policy H-160.912. The structure and function of interprofessional health care teams. https://policysearch.ama-assn.org/policyfinder/detail/The%20Structure%20and%20Function%20of%20Interprofessional%20Health%20Care%20Teams?uri=%2FAMADoc%2FHOD.xml-0-727.xml. Accessed June 20, 2019.

18. Milani RV, Lavie CJ. Health care 2020: reengineering health care delivery to combat chronic disease. Am J Med. 2015;128:337-343.

19. Hill RG Jr, Sears LM, Melanson SW. 4000 clicks: a productivity analysis of electronic medical records in a community hospital ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1591-1594.

20. Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:e100-e106.