User login

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of describing what adenomyosis will look like on transvaginal ultrasound

In my first book, entitled Endovaginal Ultrasound,1 I coined the phrase “sonomicoscopy.” I maintain that we are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasound that you could not see with your naked eye if you could hold the structure at arms length and squint at it.

Adenomyosis is defined as endometrial glands and stroma embedded within the myometrium. Literature has shown that if you do three sections on a routine hysterectomy specimen the incidence of adenomyosis is 31%; with six sections the incidence is 61%! In other words, it is a very prevalent occurrence.

There is no question that adenomyosis CAN be a source of uterine enlargement, pain, and bleeding. But it is such a prevalent finding that the real question is: What percent of women, especially parous women, will have sonographic evidence of adenomyosis but be totally asymptomatic? Such women represent the denominator while the symptomatic ones represent the numerator. I worry about labeling asymptomatic patients with this entity—when they become perimenopausal and oligo-ovulatory, and may have irregular bleeding—their symptoms can be judged to be FROM adenomyosis and surgical correction is offered.

An important part of successful ultrasound use is being sure that we redefine what is “normal” as we examine patients with this “low power microscope.” So, while transvaginal ultrasound CAN identify glands and stroma within the myometrium, we must be careful not to automatically label this finding as a “disease.”

Reference

1. Goldstein SR. Endovaginal Ultrasound. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ; January 1991.

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

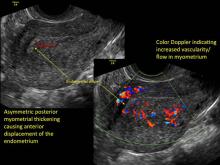

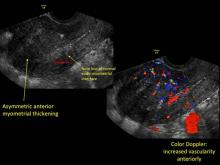

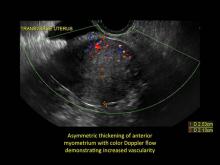

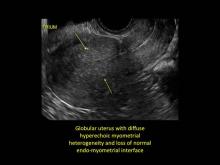

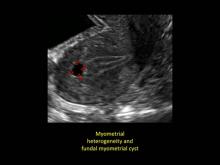

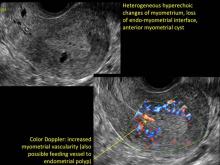

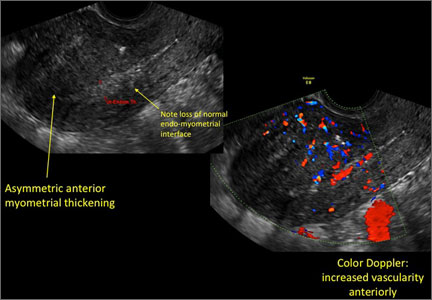

Uterine adenomyosis is a pathologic condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present in the uterine myometrium. Uterine adenomyosis is common, and may coexist with leiomyomata or endometriosis. When present, it may cause dysmenorrhea and heavy menses.

Until recently, the best way to establish a diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis was through histologic examination of a hysterectomy specimen. However, transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be accurate for noninvasive diagnosis.

Signs on imaging include:

- Globular/bulky uterus

- Asymmetric thickening of myometrium

- Loss of clarity of endo-myometrial interface

- Diffuse heterogenous myometrial echogenicity

- Myometrial cysts

| Click to enlarge image |

1. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2010;89(11):1374-1384.

2. Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):107.e1-e6.

3. Munro MG. Update: abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2014;26(3):27-32.

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of describing what adenomyosis will look like on transvaginal ultrasound

In my first book, entitled Endovaginal Ultrasound,1 I coined the phrase “sonomicoscopy.” I maintain that we are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasound that you could not see with your naked eye if you could hold the structure at arms length and squint at it.

Adenomyosis is defined as endometrial glands and stroma embedded within the myometrium. Literature has shown that if you do three sections on a routine hysterectomy specimen the incidence of adenomyosis is 31%; with six sections the incidence is 61%! In other words, it is a very prevalent occurrence.

There is no question that adenomyosis CAN be a source of uterine enlargement, pain, and bleeding. But it is such a prevalent finding that the real question is: What percent of women, especially parous women, will have sonographic evidence of adenomyosis but be totally asymptomatic? Such women represent the denominator while the symptomatic ones represent the numerator. I worry about labeling asymptomatic patients with this entity—when they become perimenopausal and oligo-ovulatory, and may have irregular bleeding—their symptoms can be judged to be FROM adenomyosis and surgical correction is offered.

An important part of successful ultrasound use is being sure that we redefine what is “normal” as we examine patients with this “low power microscope.” So, while transvaginal ultrasound CAN identify glands and stroma within the myometrium, we must be careful not to automatically label this finding as a “disease.”

Reference

1. Goldstein SR. Endovaginal Ultrasound. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ; January 1991.

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine adenomyosis is a pathologic condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present in the uterine myometrium. Uterine adenomyosis is common, and may coexist with leiomyomata or endometriosis. When present, it may cause dysmenorrhea and heavy menses.

Until recently, the best way to establish a diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis was through histologic examination of a hysterectomy specimen. However, transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be accurate for noninvasive diagnosis.

Signs on imaging include:

- Globular/bulky uterus

- Asymmetric thickening of myometrium

- Loss of clarity of endo-myometrial interface

- Diffuse heterogenous myometrial echogenicity

- Myometrial cysts

| Click to enlarge image |

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of describing what adenomyosis will look like on transvaginal ultrasound

In my first book, entitled Endovaginal Ultrasound,1 I coined the phrase “sonomicoscopy.” I maintain that we are seeing things with transvaginal ultrasound that you could not see with your naked eye if you could hold the structure at arms length and squint at it.

Adenomyosis is defined as endometrial glands and stroma embedded within the myometrium. Literature has shown that if you do three sections on a routine hysterectomy specimen the incidence of adenomyosis is 31%; with six sections the incidence is 61%! In other words, it is a very prevalent occurrence.

There is no question that adenomyosis CAN be a source of uterine enlargement, pain, and bleeding. But it is such a prevalent finding that the real question is: What percent of women, especially parous women, will have sonographic evidence of adenomyosis but be totally asymptomatic? Such women represent the denominator while the symptomatic ones represent the numerator. I worry about labeling asymptomatic patients with this entity—when they become perimenopausal and oligo-ovulatory, and may have irregular bleeding—their symptoms can be judged to be FROM adenomyosis and surgical correction is offered.

An important part of successful ultrasound use is being sure that we redefine what is “normal” as we examine patients with this “low power microscope.” So, while transvaginal ultrasound CAN identify glands and stroma within the myometrium, we must be careful not to automatically label this finding as a “disease.”

Reference

1. Goldstein SR. Endovaginal Ultrasound. 2nd ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ; January 1991.

Uterine adenomyosis: Noninvasive diagnosis

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine adenomyosis is a pathologic condition in which endometrial glands and stroma are present in the uterine myometrium. Uterine adenomyosis is common, and may coexist with leiomyomata or endometriosis. When present, it may cause dysmenorrhea and heavy menses.

Until recently, the best way to establish a diagnosis of uterine adenomyosis was through histologic examination of a hysterectomy specimen. However, transvaginal ultrasound and pelvic magnetic resonance imaging have been shown to be accurate for noninvasive diagnosis.

Signs on imaging include:

- Globular/bulky uterus

- Asymmetric thickening of myometrium

- Loss of clarity of endo-myometrial interface

- Diffuse heterogenous myometrial echogenicity

- Myometrial cysts

| Click to enlarge image |

1. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2010;89(11):1374-1384.

2. Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):107.e1-e6.

3. Munro MG. Update: abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2014;26(3):27-32.

1. Champaneria R, Abedin P, Daniels J, Balogun M, Khan KS. Ultrasound scan and magnetic resonance imaging for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review comparing test accuracy. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2010;89(11):1374-1384.

2. Meredith SM, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal sonography for the diagnosis of adenomyosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;201(1):107.e1-e6.

3. Munro MG. Update: abnormal uterine bleeding. OBG Manag. 2014;26(3):27-32.

What is the clinical and economic return on taxpayers’ $260M investment in the WHI?

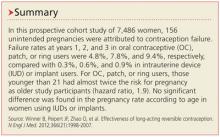

The WHI estrogen plus progestin (EPT) clinical trial, a $260 million venture, is among the most expensive projects ever undertaken by the National Institutes of Health. Following 2002 publication of its initial findings, use of EPT and estrogen alone (ET) hormone therapy (HT) among US women plummeted. Investigators, including WHI leadership, estimated the clinical and economic impact of this trial from a payer perspective.

Details of the study

For the years 2003 to 2012, the authors used a disease-simulation model to evaluate the effect of the WHI EPT trial on women aged 50 to 79 with an intact uterus (women who were combined-HT [cHT], or EPT, eligible). They compared outcomes between a “WHI scenario,” in which the prevalence of cHT use was based on actual WHI findings, with a “no-WHI” scenario, in which pre-WHI trends in cHT use (from 1998 to 2002) were linearly extrapolated.

The simulation model predicted that 9.5 million women used cHT in the no-WHI scenario, 4.3 million more than actually used cHT in the WHI scenario. The authors estimated that, compared with the no-WHI scenario, 126,000, 76,000, and 80,000 fewer respective cases of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and venous thromboembolism occurred and that 263,000 and 15,000 more respective cases of fractures and colorectal cancer occurred among women as a result of the WHI.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Regarding economic outcomes, the authors estimated that the WHI resulted in $35.2 billion in direct medical expenditure savings—principally from fewer prescriptions for EPT and associated office visits ($26.2 billion), but also from decreased breast cancer incidence ($4.5 billion) and decreased CVD incidence ($2.2 billion), among other savings, which offset increases in expenditures for greater fracture incidence ($4.8 billion) and colorectal cancer ($1.0 billion).

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

In addition, the investigators reported a tremendous gain in quality of life years (145,000) in the WHI versus the no-WHI scenario, attributing the difference to the greater health-related quality-of-life effect associated with decreased breast cancer and CVD incidence in the WHI scenario.

What this evidence means for practice

At first glance, the clinical and economic benefits of the WHI EPT trial appear enormous. However, the authors surprisingly failed to take into consideration relevant issues well known to women’s health clinicians: lower use of systemic HT (both in women with an intact uterus and those posthysterectomy) has resulted in many more women suffering from bothersome vasomotor and sleep-related menopausal symptoms, with resultant impairment of quality of life.

In addition, the authors did not account for the major reduction in use of ET after the 2002 WHI findings in women who have had a hysterectomy; given that ET reduces the incidence of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease, declines in ET use have resulted in increased morbidity and mortality from these conditions.1

Finally, as the profound declines in use of systemic HT have not been accompanied by a substantive increase in the use of vaginal estrogen, we have an epidemic of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy, with attendant sexual dysfunction and impaired quality of life.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

Reference

- Sarrel PM, Njike VY, Vinante V, Katz DL. The mortality toll of estrogen avoidance: an analysis of excess deaths among hysterectomized women aged 50 to 59 years. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1583–1588.

The WHI estrogen plus progestin (EPT) clinical trial, a $260 million venture, is among the most expensive projects ever undertaken by the National Institutes of Health. Following 2002 publication of its initial findings, use of EPT and estrogen alone (ET) hormone therapy (HT) among US women plummeted. Investigators, including WHI leadership, estimated the clinical and economic impact of this trial from a payer perspective.

Details of the study

For the years 2003 to 2012, the authors used a disease-simulation model to evaluate the effect of the WHI EPT trial on women aged 50 to 79 with an intact uterus (women who were combined-HT [cHT], or EPT, eligible). They compared outcomes between a “WHI scenario,” in which the prevalence of cHT use was based on actual WHI findings, with a “no-WHI” scenario, in which pre-WHI trends in cHT use (from 1998 to 2002) were linearly extrapolated.

The simulation model predicted that 9.5 million women used cHT in the no-WHI scenario, 4.3 million more than actually used cHT in the WHI scenario. The authors estimated that, compared with the no-WHI scenario, 126,000, 76,000, and 80,000 fewer respective cases of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and venous thromboembolism occurred and that 263,000 and 15,000 more respective cases of fractures and colorectal cancer occurred among women as a result of the WHI.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Regarding economic outcomes, the authors estimated that the WHI resulted in $35.2 billion in direct medical expenditure savings—principally from fewer prescriptions for EPT and associated office visits ($26.2 billion), but also from decreased breast cancer incidence ($4.5 billion) and decreased CVD incidence ($2.2 billion), among other savings, which offset increases in expenditures for greater fracture incidence ($4.8 billion) and colorectal cancer ($1.0 billion).

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

In addition, the investigators reported a tremendous gain in quality of life years (145,000) in the WHI versus the no-WHI scenario, attributing the difference to the greater health-related quality-of-life effect associated with decreased breast cancer and CVD incidence in the WHI scenario.

What this evidence means for practice

At first glance, the clinical and economic benefits of the WHI EPT trial appear enormous. However, the authors surprisingly failed to take into consideration relevant issues well known to women’s health clinicians: lower use of systemic HT (both in women with an intact uterus and those posthysterectomy) has resulted in many more women suffering from bothersome vasomotor and sleep-related menopausal symptoms, with resultant impairment of quality of life.

In addition, the authors did not account for the major reduction in use of ET after the 2002 WHI findings in women who have had a hysterectomy; given that ET reduces the incidence of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease, declines in ET use have resulted in increased morbidity and mortality from these conditions.1

Finally, as the profound declines in use of systemic HT have not been accompanied by a substantive increase in the use of vaginal estrogen, we have an epidemic of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy, with attendant sexual dysfunction and impaired quality of life.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

The WHI estrogen plus progestin (EPT) clinical trial, a $260 million venture, is among the most expensive projects ever undertaken by the National Institutes of Health. Following 2002 publication of its initial findings, use of EPT and estrogen alone (ET) hormone therapy (HT) among US women plummeted. Investigators, including WHI leadership, estimated the clinical and economic impact of this trial from a payer perspective.

Details of the study

For the years 2003 to 2012, the authors used a disease-simulation model to evaluate the effect of the WHI EPT trial on women aged 50 to 79 with an intact uterus (women who were combined-HT [cHT], or EPT, eligible). They compared outcomes between a “WHI scenario,” in which the prevalence of cHT use was based on actual WHI findings, with a “no-WHI” scenario, in which pre-WHI trends in cHT use (from 1998 to 2002) were linearly extrapolated.

The simulation model predicted that 9.5 million women used cHT in the no-WHI scenario, 4.3 million more than actually used cHT in the WHI scenario. The authors estimated that, compared with the no-WHI scenario, 126,000, 76,000, and 80,000 fewer respective cases of breast cancer, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and venous thromboembolism occurred and that 263,000 and 15,000 more respective cases of fractures and colorectal cancer occurred among women as a result of the WHI.

Related article: When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Cases in Menopause; February 2014)

Regarding economic outcomes, the authors estimated that the WHI resulted in $35.2 billion in direct medical expenditure savings—principally from fewer prescriptions for EPT and associated office visits ($26.2 billion), but also from decreased breast cancer incidence ($4.5 billion) and decreased CVD incidence ($2.2 billion), among other savings, which offset increases in expenditures for greater fracture incidence ($4.8 billion) and colorectal cancer ($1.0 billion).

Related article: In the latest report from the WHI, the data contradict the conclusions. Holly Thacker, MD (Commentary; March 2014)

In addition, the investigators reported a tremendous gain in quality of life years (145,000) in the WHI versus the no-WHI scenario, attributing the difference to the greater health-related quality-of-life effect associated with decreased breast cancer and CVD incidence in the WHI scenario.

What this evidence means for practice

At first glance, the clinical and economic benefits of the WHI EPT trial appear enormous. However, the authors surprisingly failed to take into consideration relevant issues well known to women’s health clinicians: lower use of systemic HT (both in women with an intact uterus and those posthysterectomy) has resulted in many more women suffering from bothersome vasomotor and sleep-related menopausal symptoms, with resultant impairment of quality of life.

In addition, the authors did not account for the major reduction in use of ET after the 2002 WHI findings in women who have had a hysterectomy; given that ET reduces the incidence of breast cancer and cardiovascular disease, declines in ET use have resulted in increased morbidity and mortality from these conditions.1

Finally, as the profound declines in use of systemic HT have not been accompanied by a substantive increase in the use of vaginal estrogen, we have an epidemic of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy, with attendant sexual dysfunction and impaired quality of life.

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

TELL US WHAT YOU THINK!

Share your thoughts on this article. Send your Letter to the Editor: rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com

Reference

- Sarrel PM, Njike VY, Vinante V, Katz DL. The mortality toll of estrogen avoidance: an analysis of excess deaths among hysterectomized women aged 50 to 59 years. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1583–1588.

Reference

- Sarrel PM, Njike VY, Vinante V, Katz DL. The mortality toll of estrogen avoidance: an analysis of excess deaths among hysterectomized women aged 50 to 59 years. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(9):1583–1588.

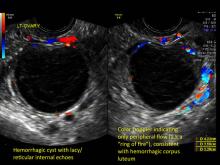

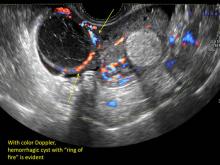

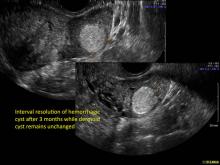

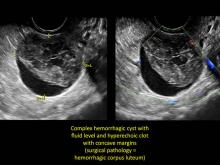

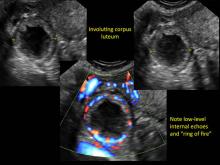

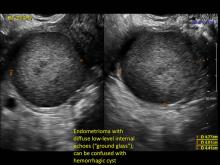

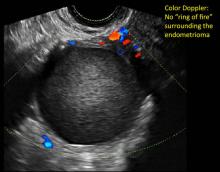

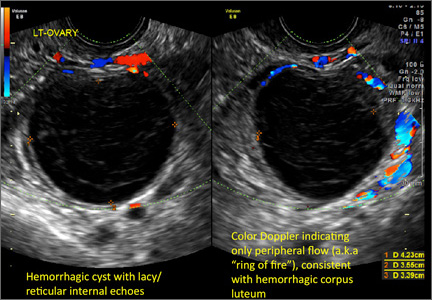

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

FOREWARD

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

This is the inaugural offering in a new series, titled Images in Gyn Ultrasound. It is interesting and important that Dr. Michelle Stalnaker and Dr. Andrew Kaunitz have chosen hemorrhagic ovarian cysts as their debut topic.

Realize that since the vaginal probe was introduced in the 1980s, our entire specialty has had to undergo a learning curve--just as individuals will have a learning curve. In the early days of transvaginal ultrasound, an imager often provided a differential for such masses, along the lines of “compatible with hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, dermoid…cannot rule out neoplasia.” Today, however, with better understanding, and especially with the addition of color flow Doppler, very often a definitive diagnosis can be made.

These “hemorrhagic cysts” are nothing more than bleeding into a corpus luteum at the time of ovulation−the more blood that collects before tamponade or clot stops its accumulation, the larger the “cyst” can become. As the cyst goes through a “maturation” process and undergoes clot retraction and clot lysis, the variable internal echo patterns presented in the following images are possible, but there will ALWAYS only be peripheral blood flow as evidenced by the morphologic appearance of the vascular distribution. See video.

Study these images carefully as they are very representative of the many faces of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Hemorrhagic cysts are normal in ovulatory women, usually resolving within 8 weeks. They can be quite variable in appearance, however, and can be confused with ovarian endometriomae. Presenting characteristics can include:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, fishnet) internal echoes due to fibrin strands

- a solid-appearing area with concave margins

- on Color Doppler: circumferential peripheral vascular flow (“ring of fire”), with no internal flow

Management. With respect to hemorrhagic cysts, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement indicates:

- For premenopausal women:

- No follow-up imaging needed unless there’s an uncertain diagnosis or if the cyst is larger than 5 cm

- Cyst size > 5 cm; short-interval follow-up ultrasound is indicated (6-12 weeks)

- For recently menopausal women:

- Follow-up ultrasound in 6 to 12 weeks to ensure resolution of the initial findings

- For later postmenopausal women:

- Cyst possibly neoplastic; consider surgical removal

FOREWARD

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

This is the inaugural offering in a new series, titled Images in Gyn Ultrasound. It is interesting and important that Dr. Michelle Stalnaker and Dr. Andrew Kaunitz have chosen hemorrhagic ovarian cysts as their debut topic.

Realize that since the vaginal probe was introduced in the 1980s, our entire specialty has had to undergo a learning curve--just as individuals will have a learning curve. In the early days of transvaginal ultrasound, an imager often provided a differential for such masses, along the lines of “compatible with hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, dermoid…cannot rule out neoplasia.” Today, however, with better understanding, and especially with the addition of color flow Doppler, very often a definitive diagnosis can be made.

These “hemorrhagic cysts” are nothing more than bleeding into a corpus luteum at the time of ovulation−the more blood that collects before tamponade or clot stops its accumulation, the larger the “cyst” can become. As the cyst goes through a “maturation” process and undergoes clot retraction and clot lysis, the variable internal echo patterns presented in the following images are possible, but there will ALWAYS only be peripheral blood flow as evidenced by the morphologic appearance of the vascular distribution. See video.

Study these images carefully as they are very representative of the many faces of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Hemorrhagic cysts are normal in ovulatory women, usually resolving within 8 weeks. They can be quite variable in appearance, however, and can be confused with ovarian endometriomae. Presenting characteristics can include:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, fishnet) internal echoes due to fibrin strands

- a solid-appearing area with concave margins

- on Color Doppler: circumferential peripheral vascular flow (“ring of fire”), with no internal flow

Management. With respect to hemorrhagic cysts, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement indicates:

- For premenopausal women:

- No follow-up imaging needed unless there’s an uncertain diagnosis or if the cyst is larger than 5 cm

- Cyst size > 5 cm; short-interval follow-up ultrasound is indicated (6-12 weeks)

- For recently menopausal women:

- Follow-up ultrasound in 6 to 12 weeks to ensure resolution of the initial findings

- For later postmenopausal women:

- Cyst possibly neoplastic; consider surgical removal

FOREWARD

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

This is the inaugural offering in a new series, titled Images in Gyn Ultrasound. It is interesting and important that Dr. Michelle Stalnaker and Dr. Andrew Kaunitz have chosen hemorrhagic ovarian cysts as their debut topic.

Realize that since the vaginal probe was introduced in the 1980s, our entire specialty has had to undergo a learning curve--just as individuals will have a learning curve. In the early days of transvaginal ultrasound, an imager often provided a differential for such masses, along the lines of “compatible with hemorrhagic cyst, endometrioma, dermoid…cannot rule out neoplasia.” Today, however, with better understanding, and especially with the addition of color flow Doppler, very often a definitive diagnosis can be made.

These “hemorrhagic cysts” are nothing more than bleeding into a corpus luteum at the time of ovulation−the more blood that collects before tamponade or clot stops its accumulation, the larger the “cyst” can become. As the cyst goes through a “maturation” process and undergoes clot retraction and clot lysis, the variable internal echo patterns presented in the following images are possible, but there will ALWAYS only be peripheral blood flow as evidenced by the morphologic appearance of the vascular distribution. See video.

Study these images carefully as they are very representative of the many faces of the hemorrhagic corpus luteum.

Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: One entity with many appearances

Michelle L. Stalnaker, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Hemorrhagic cysts are normal in ovulatory women, usually resolving within 8 weeks. They can be quite variable in appearance, however, and can be confused with ovarian endometriomae. Presenting characteristics can include:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, fishnet) internal echoes due to fibrin strands

- a solid-appearing area with concave margins

- on Color Doppler: circumferential peripheral vascular flow (“ring of fire”), with no internal flow

Management. With respect to hemorrhagic cysts, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement indicates:

- For premenopausal women:

- No follow-up imaging needed unless there’s an uncertain diagnosis or if the cyst is larger than 5 cm

- Cyst size > 5 cm; short-interval follow-up ultrasound is indicated (6-12 weeks)

- For recently menopausal women:

- Follow-up ultrasound in 6 to 12 weeks to ensure resolution of the initial findings

- For later postmenopausal women:

- Cyst possibly neoplastic; consider surgical removal

When should a menopausal woman discontinue hormone therapy?

CASE: AFTER 3 YEARS OF HT, A PATIENT ASKS WHETHER IT’S TIME TO QUIT

My menopausal patient is a 57-year-old woman with a body mass index (BMI) of 21 kg/m2. Her mother, who also was slender, suffered a hip fracture at age 74.

When this patient was 53, approximately 8 months after her last menstrual period, she scheduled a problem visit to discuss bothersome hot flushes, which occurred primarily at night. These symptoms were associated with sleep disruption and irritability. At that problem visit, the patient and I discussed the benefits and risks of menopausal hormone therapy (HT), and she elected to initiate it, choosing transdermal estradiol using an 0.05-mg patch, combined with oral micronized progesterone 100-mg (one capsule) at bedtime. Two months later, she telephoned my office to report that she was experiencing only moderate relief of her symptoms. I increased the dose of estradiol to 0.075 mg. On her next well-woman visit, the patient remarked that her symptoms were largely resolved and said that she wished to continue the regimen.

Now, as she presents for her well-woman visit 3 years later, she asks how long she should continue the HT.

How would you counsel such a patient?

Although the duration of HT is still marked by controversy, clinicians often encounter the issue in practice. As the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) notes in a recent Practice Pearl and in its 2012 Position Statement on hormone therapy, the determination of the optimal duration of HT can be a challenge for clinicians and patients.1,2

In this article, I discuss indications for HT and consider variables that may influence its duration. I also offer practical guidance on therapeutic options for women who elect to use HT for an extended duration.

HOT FLUSHES CAN BE A LONG-TERM CONCERN

Moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS) are the most common indication for systemic combination estrogen-progestin or estrogen-only HT—and HT is the most effective treatment for VMS.2

Some experts have cautioned that “it remains prudent to keep the…duration of treatment short” or that HT “may serve a useful role in short-term symptom management.”3,4 However, for many menopausal women, VMS are a long-term concern. The Penn Ovarian Aging Study was conducted to estimate the duration of moderate-to-severe VMS and found a median duration of such symptoms of more than 10 years. In this landmark cohort study, the median duration of VMS, which began near the time of the menopausal transition, was almost 12 years.5

In a study of older menopausal women (mean age, 67 years; mean time since menopause, 19 years), 11.8% reported “clinically significant” hot flushes and “more than half of these women who complained of significant hot flushes at baseline continued to report bothersome symptoms after 3 years.”6

These observations underscore the fact that, in many women, short-term use (3–5 years) of HT will not be sufficient to control bothersome VMS.

SYSTEMIC HT ALSO BENEFITS BONE

The standard daily dose of HT (eg, conjugated equine estrogens [CEE], 0.625 mg; micronized estradiol, 1.0 mg; or transdermal estradiol, 0.05 mg) for relief of VMS also prevents osteoporosis,2 with many HT formulations approved for prevention of this condition. Randomized trial data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) also have confirmed that a standard dose of HT prevents fractures in menopausal women.2

However, in menopausal women, doses of estrogen therapy substantially lower than those commonly used to treat VMS can still maintain or improve bone mineral density (BMD). For example, serum estradiol levels remain in the menopausal range during use of the weekly estradiol ultra-low-dose patch (0.014 mg).7 In a clinical trial of women (mean age, 66 years) with an intact uterus, use of this ultra-low-dose estradiol patch for 2 years without progestin did not increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia7—although this patch does appear to increase the incidence of endometrial proliferation.8 For this reason, periodic endometrial monitoring may be appropriate in women using the 0.014-mg estradiol patch over the long term, including vaginal ultrasound assessment of endometrial thickness. Package labeling for this patch recommends that women with an intact uterus be given a progestogen for 14 days every 6 to 12 months.9

Related Article: Update on Osteoporosis Steven R. Goldstein, MD (December 2013)

Although the ultra-low-dose estradiol patch is approved for the prevention of osteoporosis, its efficacy in treating VMS is uncertain. For instance, in a study of this patch in women aged 60 to 80 years, with skeletal health and safety as the primary outcomes, 16% of participants reported VMS at baseline. The 0.014-mg estradiol patch did not reduce VMS more than placebo.10 However, in a trial of the 0.014-mg estradiol patch in which impact on VMS was the primary outcome, the ultra-low-dose patch did relieve VMS.11 (The ultra-low-dose patch currently is not approved to treat VMS.) Low-dose CEE (0.3 mg, 0.45 mg) and low-dose oral estradiol (0.5 mg) have been found to be effective in the treatment of VMS.12,13

Data on the risk of osteoporotic fractures among women using the ultra-low-dose estradiol patch are not available.

Use of HT to prevent osteoporosis is appropriate for women who have other indications for HT, such as VMS. For women using HT who no longer experience VMS, long-term use of HT for osteoporosis is controversial. However, it may be considered for women at elevated risk for osteoporosis when skeleton-specific treatments (eg, bisphosphonates) are not tolerated or when such women prefer not to use skeleton-specific therapy.

FDA package labeling for systemic HT indicates that, “When prescribing solely for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis, therapy only should be considered for women at significant risk of osteoporosis, and non-estrogen medications should be carefully considered.”14

The NAMS 2012 Position Statement on HT states: “Provided that the woman is well aware of the potential benefits and risks and has clinical supervision, extending [estrogen-progestin therapy] use with the lowest effective dose is acceptable under some circumstances, including 1) for the woman who has determined that the benefits of menopause symptom relief outweigh risks, notably after failing an attempt to stop [estrogen-progestin therapy], and 2) for the woman at high risk of fracture for whom alternate therapies are not appropriate or cause unacceptable adverse effects.”2

A 2014 Practice Bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on the management of menopausal symptoms states: “The decision to continue HT should be individualized and be based on a woman’s symptoms and the risk–benefit ratio, regardless of age. Because some women aged 65 years and older may continue to need systemic HT for the management of vasomotor symptoms, ACOG recommends against routine discontinuation of systemic estrogen at age 65. As with younger women, use of HT and estrogen therapy should be individualized based on each woman’s risk–benefit ratio and clinical presentation.”15

As I have detailed, doses of HT that are lower than those used to treat VMS can prevent loss of BMD. Accordingly, clinicians prescribing HT for the sole indication of osteoporosis prevention should use doses lower than those for standard HT. Moreover, clinicians prescribing HT specifically to prevent osteoporosis should recognize the elevated risk of breast cancer with estrogen-progestin therapy. Extended use of estrogen-only therapy is more appropriate for this indication.

Related Article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause, May 2013)

While estrogen-only therapy is common in women following hysterectomy, ultra-low-dose estrogen therapy with regular endometrial monitoring also can be considered in women with an intact uterus.

Also be aware that BMD declines rapidly after discontinuation of HT (in contrast with bisphosphonates), so alternative agents to maintain BMD should be considered when HT is stopped.16

HOW SAFE IS EXTENDED USE OF SYSTEMIC HT?

The incidence of breast cancer and mortality from breast cancer increase after 3 to 5 years of estrogen-progestin therapy, and the risk of stroke remains elevated throughout use of combination as well as estrogen-only HT.2 Women with an intact uterus who choose to extend the duration of combination therapy beyond 5 years for control of VMS or protection against osteoporosis, or both, need to be candidly counseled about these concerns. No increase in the risk of breast cancer was observed in the estrogen-only arm of the WHI randomized, clinical trial (mean duration of CEE therapy of 7.1 years).17

Related Article: Stop enforcing a 5-year rule for menopausal hormone therapy Robert L. Reid, MD (Stop/Start, December 2013)

Long-term risks of oral estrogen

Among women who initiate HT at the time of menopause, long-term use does not appear to increase the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), although follow-up in clinical trials has not extended beyond 7 years for estrogen-progestin therapy, and midlife may bring increases in a woman’s baseline cardiovascular risk.2 However, in the WHI, women who initiated oral estrogen-only or estrogen-progestin therapy later in menopause experienced an increased risk of CHD,18 underscoring the need for caution and individualization in this patient population.

Oral HT increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke.2 In addition, age is an independent risk factor for these two outcomes. Observational studies suggest that, in contrast with oral estrogen, transdermal HT does not increase the risk of VTE.19–24 Randomized trial data are lacking.

Similarly, one observational study suggests that low-dose (≤0.05 mg) transdermal estradiol does not appear to increase the risk of stroke,25 but, again, clinical trial data are unavailable.

Given these apparent safety advantages, transdermal estrogen therapy would appear to be preferable to oral estrogen in older, long-term users, a perspective supported by ACOG.26

Related Article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence, January 2014)

In regard to VTE, oral estradiol appears to be safer than CEE.27 Accordingly, oral estradiol may be preferable for older long-term users who don’t tolerate transdermal estradiol due to local skin reactions or costs. Oral estradiol also is less expensive than CEE.

What to expect when your patient discontinues systemic HT

VMS may recur is as many as 50% of women after they discontinue HT. The likelihood of recurring VMS does not appear to vary between abrupt and tapered discontinuation.2

Some HT users may be reluctant to reduce their dose or discontinue HT, particularly those who experienced severe VMS originally. In my clinical experience, many of these women are receptive to a trial of lower-dose HT, especially when I advise them that they can resume their original (higher) dose should bothersome VMS recur.

Individualized assessment of HT benefits and risks and shared decision-making play important roles in the management of these patients. As the dose of HT declines, or systemic HT is discontinued, symptoms of genital atrophy may become more prominent and, in the absence of indications for systemic HT (bothersome VMS or prevention of osteoporosis), may best be addressed with vaginal estrogen therapy or ospemifene.

Extended use of vaginal estrogen

Unlike VMS, untreated genital atrophy may continue to progress as women age, sometimes necessitating use of vaginal estrogen. Because the clinical trials that served as the basis for FDA approval of vaginal estrogen formulations did not find an elevated risk of endometrial hyperplasia, routine use of a progestin to prevent endometrial proliferation in women with an intact uterus is not recommended.28 However, these trials were too limited in duration to assure long-term endometrial safety. All postmenopausal women using vaginal ET should be advised to report any vaginal bleeding, and that bleeding should be evaluated appropriately.

Although low-dose local or vaginal estrogen therapy has not been studied in clinical trials beyond 1 year, it is thought to carry significantly fewer risks than systemic HT.28 Several studies have confirmed that serum estrogen levels remain in the postmenopausal range in women using low-dose vaginal estrogen, specifically the 3-month estradiol ring (2 mg) or twice-weekly estradiol tablets (10 µg).28

Besides relieving vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, low-dose vaginal estrogen also may improve overactive bladder and reduce the incidence of recurrent urinary tract infection.29,30

CASE: RESOLVED

The 57-year-old patient has been essentially symptom-free for the past 3 years using an estradiol patch (0.075 mg) with progesterone (100 mg nightly). Now she asks how long she should continue HT, and I explain that the duration of bothersome VMS is different in each woman. I also counsel her that hot flushes do resolve over time in almost all women. When she asks how likely it is that bothersome VMS will recur if she simply stops HT, I explain that bothersome symptoms often last 10 years or longer, and I remind her that her VMS began some 4 years earlier.

I also briefly review HT benefits (treatment of VMS as well as prevention of vulvovaginal atrophy and osteoporosis) and risks (small increased risk of breast cancer and stroke). I suggest a reduction in her HT dose as a reasonable method to determine her ongoing need for HT, telling her that she should know within about 1 month how she feels on the lower dose (0.05-mg patch). I also advise her to call my office if bothersome VMS recur on the lower dose so that I can increase the dose back to its original level.

After her estradiol dose is reduced, the patient reports only minimal VMS, and she opts to continue the estradiol patch (0.05 mg) with nightly progesterone (100 mg) for another 2 years.

At age 59, during her well-woman visit, she decides to lower the estradiol further, transitioning to a 0.0375-mg patch but maintaining the nightly progesterone (100 mg). She reports no VMS on this new regimen.

At age 61, because of her maternal history of osteoporosis and her own low BMI, the patient undergoes BMD assessment with dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). In average-risk women, NAMS recommends that BMD assessment be performed at age 65.31 The results of BMD assessment are normal.

After further discussion, the patient agrees to an even lower dose of estradiol, switching to an 0.025-mg patch, with progesterone (100 mg nightly) administered for 2 weeks in every 3-month interval. She reports no VMS or vaginal bleeding on this lower-dose HT regimen.

After 12 months on this new regimen, the patient undergoes vaginal sonography, revealing an endometrial thickness of 3 mm. She continues this regimen, including annual vaginal ultrasound assessment of the endometrium, without problems until her well-woman visit at age 65.

At that visit, I explain that discontinuation of HT is unlikely to trigger recurred VMS but may cause her to lose BMD rapidly for several years, and may also result in unpleasant symptoms from vulvovaginal atrophy including sexual discomfort. She decides to switch to an 0.014-mg estradiol patch without progesterone, and to undergo ultrasound assessment of her endometrium every 1 to 2 years.

Do you have a troubling case in menopause?

Suggest it to our expert panel. They may address your management dilemma in a future issue!

Email us at obg@frontlinemedcom.com

BOTTOM LINE: INDIVIDUALIZE THE DURATION OF HT

Although published data on extended use of HT are few, many clinicians caring for menopausal women are asked to make a recommendation. Because extended use of estrogen-progestin HT increases the risk of breast cancer, estrogen-only HT has a more favorable benefit-risk ratio. If a patient uses estrogen-progestin HT for an extended duration, periodic discussions about the elevated risk of breast cancer are appropriate.

We lack randomized trial data on CHD and other risks in women who begin HT at the time of menopause and continue it for decades. In older women who use HT for an extended duration, transdermal estrogen may be safer in regard to the risk of VTE and stroke.

As the systemic estrogen dose is lowered, it is possible to reduce the dose of the progestin (the sole function of which is to protect the endometrium from estrogen stimulation). Intermittent dosing can be used, although we lack long-term safety data, and periodic endometrial evaluation should be considered.

Remember also that, with intermittent or daily dosing of a progestin, you are relying on the patient to take this medication to protect the endometrium.

Extended use of low-dose vaginal estrogen HT may be necessary to treat symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, which tend to worsen over time. Administration of a progestin is not currently recommended with use of vaginal estrogen, but long-term use may increase the risk of endometrial stimulation.

Read other CASES IN MENOPAUSE

Your postmenopausal patient reports a history of migraine James A. Simon, MD (October 2013)

Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (May 2013)

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com

- Kaunitz AM. NAMS Practice Pearl: Extended duration use of menopausal hormone therapy [published online ahead of print January 6, 2014]. Menopause.

- North American Menopause Society. Position Statement: The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2012;19(3):257–271.

- Nelson HD. Postmenopausal estrogen for treatment of hot flashes: clinical applications. JAMA. 2004;291(13):1621–1625.

- Hulley SB, Grady D. The WHI estrogen-alone trial—do things look any better? JAMA. 2004;291(14):1769–1771.

- Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Liu Z, Gracia CR. Duration of menopausal hot flushes and associated risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(5):1095–1104.

- Huang AJ, Grady D, Jacoby VL, Blackwell TL, Bauer DC, Sawaya GF. Persistent hot flushes in older postmenopausal women. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(8):840–846.

- Ettinger B, Ensrud KE, Wallace R, Johnson KC, Cummings SR, Yankov V, Vittinghoff E, Grady D. Effects of ultralow-dose transdermal estradiol on bone mineral density: A randomized clinical trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104(3):443–451.

- Johnson SR, Ettinger B, Macer JL, Ensrud KE, Quan J, Grady D. Uterine and vaginal effects of unopposed ultralow-dose transdermal estradiol. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(4):779–787.

- Menostar [package insert]. Wayne, NJ: Bayer; 2007.

- Diem S, Grady D, Quan J, Vittinghoff E, Wallace R, Hanes V, Ensrud K. Effects of ultralow-dose transdermal estradiol on postmenopausal symptoms in women aged 60 to 80 years. Menopause. 2006;13(1):130–138.

- Bachmann GA, Schaefers M, Uddin A, Utian WH. Lowest effective transdermal 17beta-estradiol dose for relief of hot flushes in postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(4):771–779.

- Honjo H, Taketani Y. Low-dose estradiol for climacteric symptoms in Japanese women: A randomized, controlled trial. Climacteric. 2009;12(4):319–328.

- Utian WH, Shoupe D, Bachmann G, Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH. Relief of vasomotor symptoms and vaginal atrophy with lower doses of conjugated equine estrogens and medroxyprogesterone acetate. Fertil Steril. 2001;75(6):1065–1079.

- Premarin [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Pfizer; 2012.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 141: Management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(1):202–216.

- National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2013.

- Anderson GL, Chlebowski RT, Aragaki AK, et al. Conjugated equine oestrogen and breast cancer incidence and mortality in postmenopausal women with hysterectomy: Extended follow-up of the Women’s Health Initiative randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(5):476–486.

- Rossouw JE, Prentice RL, Manson JE, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of cardiovascular disease by age and years since menopause. JAMA. 2007;4:297(13):1465–1477.

- Canonico M, Fournier A, Carcaillon L, et al. Postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of idiopathic venous thromboembolism: results from the E3N cohort study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(2):340–345.

- Sweetland S, Beral V, Balkwill A, et al; The Million Women Study Collaborators. Venous thromboembolism risk in relation to use of different types of postmenopausal hormone therapy in a large prospective study [published online ahead of print September 10, 2012]. J Thromb Haemost. 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2012.04919.x.

- Roach RE, Lijfering WM, Helmerhorst FM, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, van Hylckama Vlieg A. The risk of venous thrombosis in women over 50 years old using oral contraception or postmenopausal hormone therapy. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(1):124–131.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Suissa S. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of venous thromboembolism: A population-based study. J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8(5):979–986.

- Laliberté F, Dea K, Duh MS, Kahler KH, Rolli M, Lefebvre P. Does the route of administration for estrogen hormone therapy impact the risk of venous thromboembolism? Estradiol transdermal system versus oral estrogen-only hormone therapy. Menopause. 2011;18(10):1052–1059.

- Scarabin PY, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G; EStrogen and THromboEmbolism Risk Study Group. Differential association of oral and transdermal oestrogen-replacement therapy with venous thromboembolism risk. Lancet. 2003;362(9382):428–432.

- Renoux C, Dell’Aniello S, Garbe E, Suissa S. Transdermal and oral hormone replacement therapy and the risk of stroke: A nested case-control study. BMJ. 2010;340:c2519. doi:10.1136/bmj.c2519.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 556: Postmenopausal estrogen therapy: Route of administration and risk of venous thromboembolism. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;121(4):887–890.

- Smith NL, Blondon M, Wiggins KL, Harrington LB, van Hylckama Vlieg A, Floyd JS. Lower risk of cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women taking oral estradiol compared with oral conjugated equine estrogens. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;14(1):25–31.

- North American Menopause Society. 2013 Position Statement: Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy. Menopause. 2013;20(9):888–902.

- Nelken RS, Ozel BZ, Leegant AR, Felix JC, Mishell DR. Randomized trial of estradiol vaginal ring versus oral oxybutynin for the treatment of overactive bladder. Menopause. 2011;18(9):962–966.

- Eriksen BC. A randomized, open, parallel-group study on the preventive effect of an estradiol-releasing vaginal ring (Estring) on recurrent urinary tract infections in postmenopausal women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(5):1072–1079.

- North American Menopause Society. 2010 Position Statement: Management of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2010;17(1):25–54.

CASE: AFTER 3 YEARS OF HT, A PATIENT ASKS WHETHER IT’S TIME TO QUIT

My menopausal patient is a 57-year-old woman with a body mass index (BMI) of 21 kg/m2. Her mother, who also was slender, suffered a hip fracture at age 74.

When this patient was 53, approximately 8 months after her last menstrual period, she scheduled a problem visit to discuss bothersome hot flushes, which occurred primarily at night. These symptoms were associated with sleep disruption and irritability. At that problem visit, the patient and I discussed the benefits and risks of menopausal hormone therapy (HT), and she elected to initiate it, choosing transdermal estradiol using an 0.05-mg patch, combined with oral micronized progesterone 100-mg (one capsule) at bedtime. Two months later, she telephoned my office to report that she was experiencing only moderate relief of her symptoms. I increased the dose of estradiol to 0.075 mg. On her next well-woman visit, the patient remarked that her symptoms were largely resolved and said that she wished to continue the regimen.

Now, as she presents for her well-woman visit 3 years later, she asks how long she should continue the HT.

How would you counsel such a patient?

Although the duration of HT is still marked by controversy, clinicians often encounter the issue in practice. As the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) notes in a recent Practice Pearl and in its 2012 Position Statement on hormone therapy, the determination of the optimal duration of HT can be a challenge for clinicians and patients.1,2

In this article, I discuss indications for HT and consider variables that may influence its duration. I also offer practical guidance on therapeutic options for women who elect to use HT for an extended duration.

HOT FLUSHES CAN BE A LONG-TERM CONCERN

Moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS) are the most common indication for systemic combination estrogen-progestin or estrogen-only HT—and HT is the most effective treatment for VMS.2

Some experts have cautioned that “it remains prudent to keep the…duration of treatment short” or that HT “may serve a useful role in short-term symptom management.”3,4 However, for many menopausal women, VMS are a long-term concern. The Penn Ovarian Aging Study was conducted to estimate the duration of moderate-to-severe VMS and found a median duration of such symptoms of more than 10 years. In this landmark cohort study, the median duration of VMS, which began near the time of the menopausal transition, was almost 12 years.5

In a study of older menopausal women (mean age, 67 years; mean time since menopause, 19 years), 11.8% reported “clinically significant” hot flushes and “more than half of these women who complained of significant hot flushes at baseline continued to report bothersome symptoms after 3 years.”6

These observations underscore the fact that, in many women, short-term use (3–5 years) of HT will not be sufficient to control bothersome VMS.

SYSTEMIC HT ALSO BENEFITS BONE

The standard daily dose of HT (eg, conjugated equine estrogens [CEE], 0.625 mg; micronized estradiol, 1.0 mg; or transdermal estradiol, 0.05 mg) for relief of VMS also prevents osteoporosis,2 with many HT formulations approved for prevention of this condition. Randomized trial data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) also have confirmed that a standard dose of HT prevents fractures in menopausal women.2

However, in menopausal women, doses of estrogen therapy substantially lower than those commonly used to treat VMS can still maintain or improve bone mineral density (BMD). For example, serum estradiol levels remain in the menopausal range during use of the weekly estradiol ultra-low-dose patch (0.014 mg).7 In a clinical trial of women (mean age, 66 years) with an intact uterus, use of this ultra-low-dose estradiol patch for 2 years without progestin did not increase the risk of endometrial hyperplasia7—although this patch does appear to increase the incidence of endometrial proliferation.8 For this reason, periodic endometrial monitoring may be appropriate in women using the 0.014-mg estradiol patch over the long term, including vaginal ultrasound assessment of endometrial thickness. Package labeling for this patch recommends that women with an intact uterus be given a progestogen for 14 days every 6 to 12 months.9

Related Article: Update on Osteoporosis Steven R. Goldstein, MD (December 2013)

Although the ultra-low-dose estradiol patch is approved for the prevention of osteoporosis, its efficacy in treating VMS is uncertain. For instance, in a study of this patch in women aged 60 to 80 years, with skeletal health and safety as the primary outcomes, 16% of participants reported VMS at baseline. The 0.014-mg estradiol patch did not reduce VMS more than placebo.10 However, in a trial of the 0.014-mg estradiol patch in which impact on VMS was the primary outcome, the ultra-low-dose patch did relieve VMS.11 (The ultra-low-dose patch currently is not approved to treat VMS.) Low-dose CEE (0.3 mg, 0.45 mg) and low-dose oral estradiol (0.5 mg) have been found to be effective in the treatment of VMS.12,13

Data on the risk of osteoporotic fractures among women using the ultra-low-dose estradiol patch are not available.

Use of HT to prevent osteoporosis is appropriate for women who have other indications for HT, such as VMS. For women using HT who no longer experience VMS, long-term use of HT for osteoporosis is controversial. However, it may be considered for women at elevated risk for osteoporosis when skeleton-specific treatments (eg, bisphosphonates) are not tolerated or when such women prefer not to use skeleton-specific therapy.

FDA package labeling for systemic HT indicates that, “When prescribing solely for the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis, therapy only should be considered for women at significant risk of osteoporosis, and non-estrogen medications should be carefully considered.”14

The NAMS 2012 Position Statement on HT states: “Provided that the woman is well aware of the potential benefits and risks and has clinical supervision, extending [estrogen-progestin therapy] use with the lowest effective dose is acceptable under some circumstances, including 1) for the woman who has determined that the benefits of menopause symptom relief outweigh risks, notably after failing an attempt to stop [estrogen-progestin therapy], and 2) for the woman at high risk of fracture for whom alternate therapies are not appropriate or cause unacceptable adverse effects.”2

A 2014 Practice Bulletin from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) on the management of menopausal symptoms states: “The decision to continue HT should be individualized and be based on a woman’s symptoms and the risk–benefit ratio, regardless of age. Because some women aged 65 years and older may continue to need systemic HT for the management of vasomotor symptoms, ACOG recommends against routine discontinuation of systemic estrogen at age 65. As with younger women, use of HT and estrogen therapy should be individualized based on each woman’s risk–benefit ratio and clinical presentation.”15

As I have detailed, doses of HT that are lower than those used to treat VMS can prevent loss of BMD. Accordingly, clinicians prescribing HT for the sole indication of osteoporosis prevention should use doses lower than those for standard HT. Moreover, clinicians prescribing HT specifically to prevent osteoporosis should recognize the elevated risk of breast cancer with estrogen-progestin therapy. Extended use of estrogen-only therapy is more appropriate for this indication.

Related Article: Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (Cases in Menopause, May 2013)

While estrogen-only therapy is common in women following hysterectomy, ultra-low-dose estrogen therapy with regular endometrial monitoring also can be considered in women with an intact uterus.

Also be aware that BMD declines rapidly after discontinuation of HT (in contrast with bisphosphonates), so alternative agents to maintain BMD should be considered when HT is stopped.16

HOW SAFE IS EXTENDED USE OF SYSTEMIC HT?

The incidence of breast cancer and mortality from breast cancer increase after 3 to 5 years of estrogen-progestin therapy, and the risk of stroke remains elevated throughout use of combination as well as estrogen-only HT.2 Women with an intact uterus who choose to extend the duration of combination therapy beyond 5 years for control of VMS or protection against osteoporosis, or both, need to be candidly counseled about these concerns. No increase in the risk of breast cancer was observed in the estrogen-only arm of the WHI randomized, clinical trial (mean duration of CEE therapy of 7.1 years).17

Related Article: Stop enforcing a 5-year rule for menopausal hormone therapy Robert L. Reid, MD (Stop/Start, December 2013)

Long-term risks of oral estrogen

Among women who initiate HT at the time of menopause, long-term use does not appear to increase the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), although follow-up in clinical trials has not extended beyond 7 years for estrogen-progestin therapy, and midlife may bring increases in a woman’s baseline cardiovascular risk.2 However, in the WHI, women who initiated oral estrogen-only or estrogen-progestin therapy later in menopause experienced an increased risk of CHD,18 underscoring the need for caution and individualization in this patient population.

Oral HT increases the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE) and stroke.2 In addition, age is an independent risk factor for these two outcomes. Observational studies suggest that, in contrast with oral estrogen, transdermal HT does not increase the risk of VTE.19–24 Randomized trial data are lacking.

Similarly, one observational study suggests that low-dose (≤0.05 mg) transdermal estradiol does not appear to increase the risk of stroke,25 but, again, clinical trial data are unavailable.

Given these apparent safety advantages, transdermal estrogen therapy would appear to be preferable to oral estrogen in older, long-term users, a perspective supported by ACOG.26

Related Article: Is one oral estrogen formulation safer than another for menopausal women? Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD (Examining the Evidence, January 2014)

In regard to VTE, oral estradiol appears to be safer than CEE.27 Accordingly, oral estradiol may be preferable for older long-term users who don’t tolerate transdermal estradiol due to local skin reactions or costs. Oral estradiol also is less expensive than CEE.

What to expect when your patient discontinues systemic HT

VMS may recur is as many as 50% of women after they discontinue HT. The likelihood of recurring VMS does not appear to vary between abrupt and tapered discontinuation.2

Some HT users may be reluctant to reduce their dose or discontinue HT, particularly those who experienced severe VMS originally. In my clinical experience, many of these women are receptive to a trial of lower-dose HT, especially when I advise them that they can resume their original (higher) dose should bothersome VMS recur.

Individualized assessment of HT benefits and risks and shared decision-making play important roles in the management of these patients. As the dose of HT declines, or systemic HT is discontinued, symptoms of genital atrophy may become more prominent and, in the absence of indications for systemic HT (bothersome VMS or prevention of osteoporosis), may best be addressed with vaginal estrogen therapy or ospemifene.

Extended use of vaginal estrogen

Unlike VMS, untreated genital atrophy may continue to progress as women age, sometimes necessitating use of vaginal estrogen. Because the clinical trials that served as the basis for FDA approval of vaginal estrogen formulations did not find an elevated risk of endometrial hyperplasia, routine use of a progestin to prevent endometrial proliferation in women with an intact uterus is not recommended.28 However, these trials were too limited in duration to assure long-term endometrial safety. All postmenopausal women using vaginal ET should be advised to report any vaginal bleeding, and that bleeding should be evaluated appropriately.

Although low-dose local or vaginal estrogen therapy has not been studied in clinical trials beyond 1 year, it is thought to carry significantly fewer risks than systemic HT.28 Several studies have confirmed that serum estrogen levels remain in the postmenopausal range in women using low-dose vaginal estrogen, specifically the 3-month estradiol ring (2 mg) or twice-weekly estradiol tablets (10 µg).28

Besides relieving vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, low-dose vaginal estrogen also may improve overactive bladder and reduce the incidence of recurrent urinary tract infection.29,30

CASE: RESOLVED

The 57-year-old patient has been essentially symptom-free for the past 3 years using an estradiol patch (0.075 mg) with progesterone (100 mg nightly). Now she asks how long she should continue HT, and I explain that the duration of bothersome VMS is different in each woman. I also counsel her that hot flushes do resolve over time in almost all women. When she asks how likely it is that bothersome VMS will recur if she simply stops HT, I explain that bothersome symptoms often last 10 years or longer, and I remind her that her VMS began some 4 years earlier.

I also briefly review HT benefits (treatment of VMS as well as prevention of vulvovaginal atrophy and osteoporosis) and risks (small increased risk of breast cancer and stroke). I suggest a reduction in her HT dose as a reasonable method to determine her ongoing need for HT, telling her that she should know within about 1 month how she feels on the lower dose (0.05-mg patch). I also advise her to call my office if bothersome VMS recur on the lower dose so that I can increase the dose back to its original level.

After her estradiol dose is reduced, the patient reports only minimal VMS, and she opts to continue the estradiol patch (0.05 mg) with nightly progesterone (100 mg) for another 2 years.

At age 59, during her well-woman visit, she decides to lower the estradiol further, transitioning to a 0.0375-mg patch but maintaining the nightly progesterone (100 mg). She reports no VMS on this new regimen.

At age 61, because of her maternal history of osteoporosis and her own low BMI, the patient undergoes BMD assessment with dual x-ray absorptiometry (DXA). In average-risk women, NAMS recommends that BMD assessment be performed at age 65.31 The results of BMD assessment are normal.

After further discussion, the patient agrees to an even lower dose of estradiol, switching to an 0.025-mg patch, with progesterone (100 mg nightly) administered for 2 weeks in every 3-month interval. She reports no VMS or vaginal bleeding on this lower-dose HT regimen.

After 12 months on this new regimen, the patient undergoes vaginal sonography, revealing an endometrial thickness of 3 mm. She continues this regimen, including annual vaginal ultrasound assessment of the endometrium, without problems until her well-woman visit at age 65.

At that visit, I explain that discontinuation of HT is unlikely to trigger recurred VMS but may cause her to lose BMD rapidly for several years, and may also result in unpleasant symptoms from vulvovaginal atrophy including sexual discomfort. She decides to switch to an 0.014-mg estradiol patch without progesterone, and to undergo ultrasound assessment of her endometrium every 1 to 2 years.

Do you have a troubling case in menopause?

Suggest it to our expert panel. They may address your management dilemma in a future issue!

Email us at obg@frontlinemedcom.com

BOTTOM LINE: INDIVIDUALIZE THE DURATION OF HT

Although published data on extended use of HT are few, many clinicians caring for menopausal women are asked to make a recommendation. Because extended use of estrogen-progestin HT increases the risk of breast cancer, estrogen-only HT has a more favorable benefit-risk ratio. If a patient uses estrogen-progestin HT for an extended duration, periodic discussions about the elevated risk of breast cancer are appropriate.

We lack randomized trial data on CHD and other risks in women who begin HT at the time of menopause and continue it for decades. In older women who use HT for an extended duration, transdermal estrogen may be safer in regard to the risk of VTE and stroke.

As the systemic estrogen dose is lowered, it is possible to reduce the dose of the progestin (the sole function of which is to protect the endometrium from estrogen stimulation). Intermittent dosing can be used, although we lack long-term safety data, and periodic endometrial evaluation should be considered.

Remember also that, with intermittent or daily dosing of a progestin, you are relying on the patient to take this medication to protect the endometrium.

Extended use of low-dose vaginal estrogen HT may be necessary to treat symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, which tend to worsen over time. Administration of a progestin is not currently recommended with use of vaginal estrogen, but long-term use may increase the risk of endometrial stimulation.

Read other CASES IN MENOPAUSE

Your postmenopausal patient reports a history of migraine James A. Simon, MD (October 2013)

Your menopausal patient's breast biopsy reveals atypical hyperplasia JoAnn V. Pinkerton, MD (May 2013)

WE WANT TO HEAR FROM YOU!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Tell us what you think by emailing us at: obg@frontlinemedcom.com

CASE: AFTER 3 YEARS OF HT, A PATIENT ASKS WHETHER IT’S TIME TO QUIT

My menopausal patient is a 57-year-old woman with a body mass index (BMI) of 21 kg/m2. Her mother, who also was slender, suffered a hip fracture at age 74.

When this patient was 53, approximately 8 months after her last menstrual period, she scheduled a problem visit to discuss bothersome hot flushes, which occurred primarily at night. These symptoms were associated with sleep disruption and irritability. At that problem visit, the patient and I discussed the benefits and risks of menopausal hormone therapy (HT), and she elected to initiate it, choosing transdermal estradiol using an 0.05-mg patch, combined with oral micronized progesterone 100-mg (one capsule) at bedtime. Two months later, she telephoned my office to report that she was experiencing only moderate relief of her symptoms. I increased the dose of estradiol to 0.075 mg. On her next well-woman visit, the patient remarked that her symptoms were largely resolved and said that she wished to continue the regimen.

Now, as she presents for her well-woman visit 3 years later, she asks how long she should continue the HT.

How would you counsel such a patient?

Although the duration of HT is still marked by controversy, clinicians often encounter the issue in practice. As the North American Menopause Society (NAMS) notes in a recent Practice Pearl and in its 2012 Position Statement on hormone therapy, the determination of the optimal duration of HT can be a challenge for clinicians and patients.1,2

In this article, I discuss indications for HT and consider variables that may influence its duration. I also offer practical guidance on therapeutic options for women who elect to use HT for an extended duration.

HOT FLUSHES CAN BE A LONG-TERM CONCERN

Moderate to severe vasomotor symptoms (VMS) are the most common indication for systemic combination estrogen-progestin or estrogen-only HT—and HT is the most effective treatment for VMS.2

Some experts have cautioned that “it remains prudent to keep the…duration of treatment short” or that HT “may serve a useful role in short-term symptom management.”3,4 However, for many menopausal women, VMS are a long-term concern. The Penn Ovarian Aging Study was conducted to estimate the duration of moderate-to-severe VMS and found a median duration of such symptoms of more than 10 years. In this landmark cohort study, the median duration of VMS, which began near the time of the menopausal transition, was almost 12 years.5

In a study of older menopausal women (mean age, 67 years; mean time since menopause, 19 years), 11.8% reported “clinically significant” hot flushes and “more than half of these women who complained of significant hot flushes at baseline continued to report bothersome symptoms after 3 years.”6

These observations underscore the fact that, in many women, short-term use (3–5 years) of HT will not be sufficient to control bothersome VMS.

SYSTEMIC HT ALSO BENEFITS BONE

The standard daily dose of HT (eg, conjugated equine estrogens [CEE], 0.625 mg; micronized estradiol, 1.0 mg; or transdermal estradiol, 0.05 mg) for relief of VMS also prevents osteoporosis,2 with many HT formulations approved for prevention of this condition. Randomized trial data from the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) also have confirmed that a standard dose of HT prevents fractures in menopausal women.2