User login

Imaging the endometrioma and mature cystic teratoma

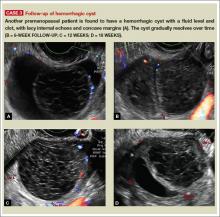

The preferred imaging method to evaluate the majority of adnexal cysts is ultrasonography, which can help characterize the cyst type. Common benign adnexal cyst types include simple, hemorrhagic, endometrioma, and mature teratoma (dermoid cyst). In this part 2 of a 4-part series on cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on imaging signs for, and follow-up of, endometriomas and mature teratomas.

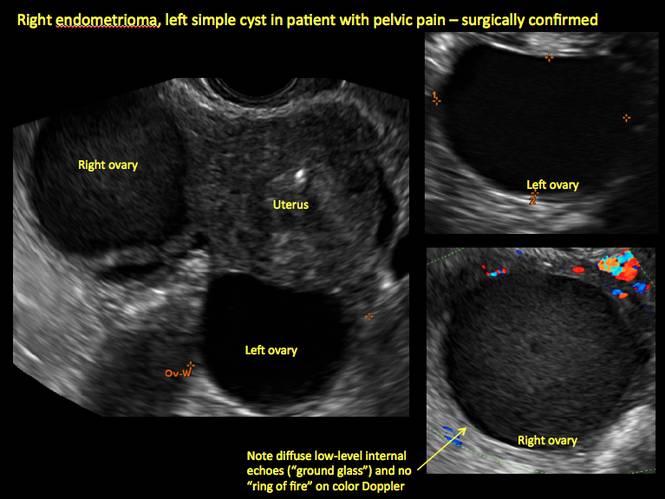

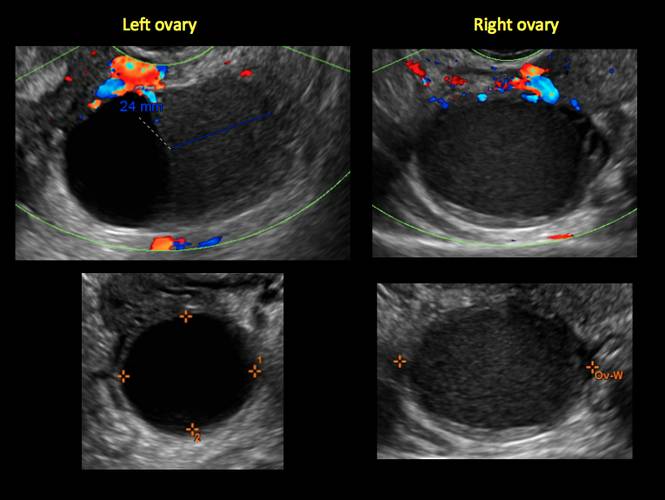

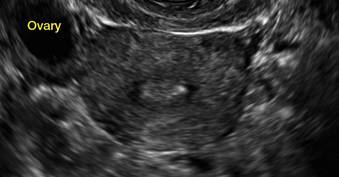

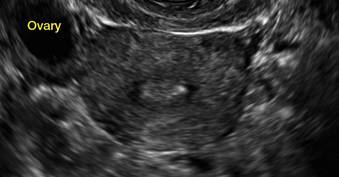

Endometriomas

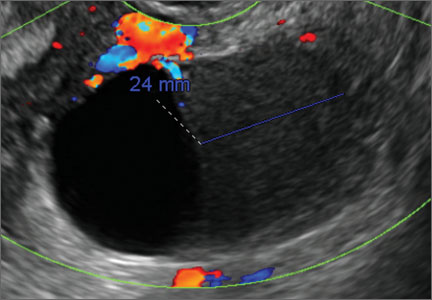

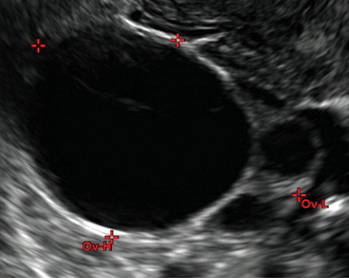

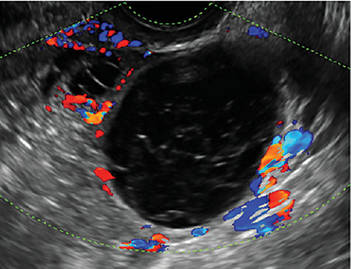

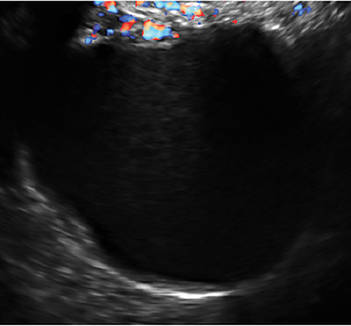

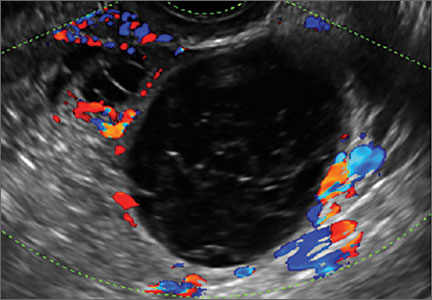

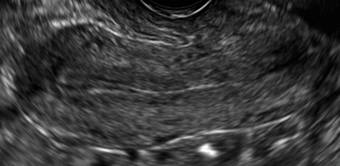

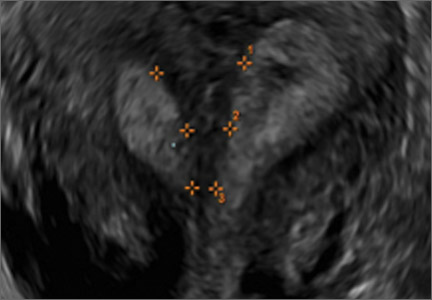

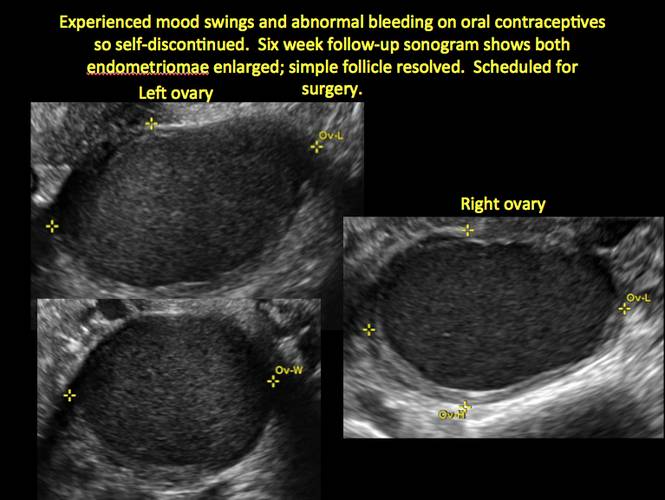

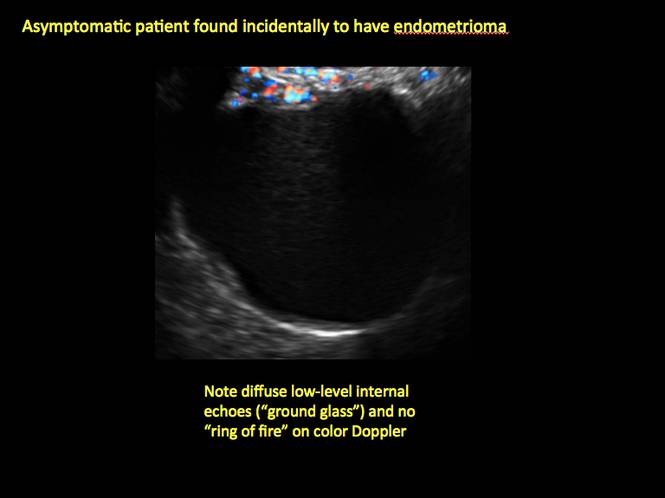

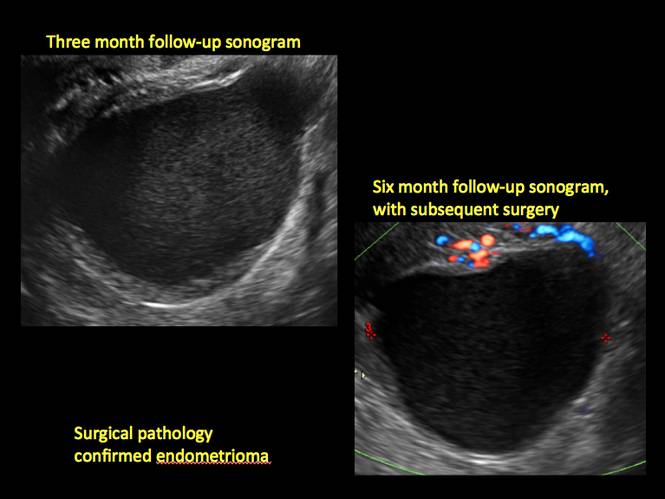

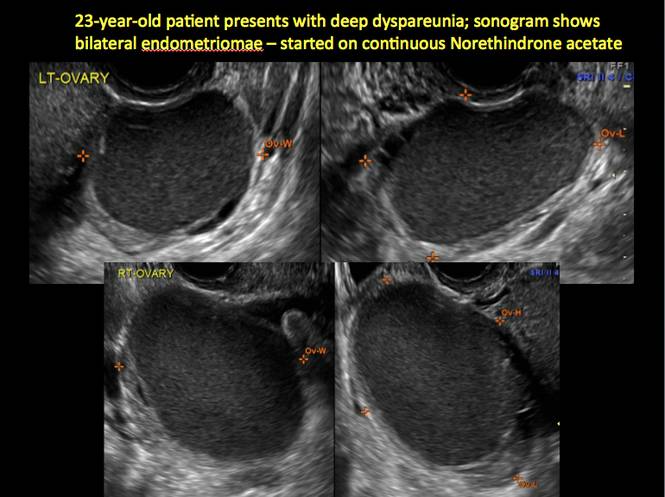

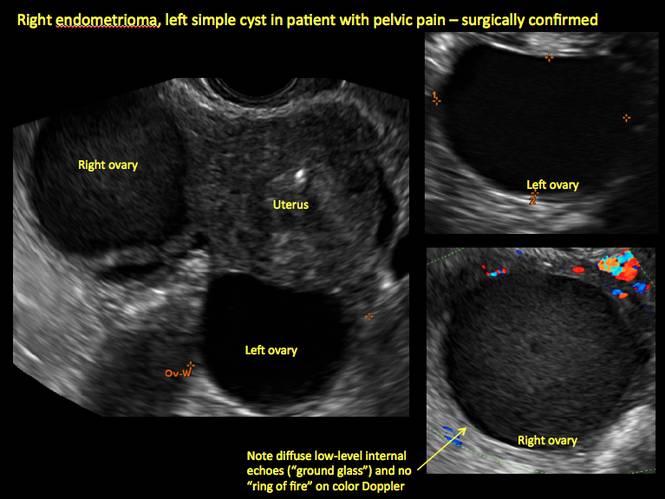

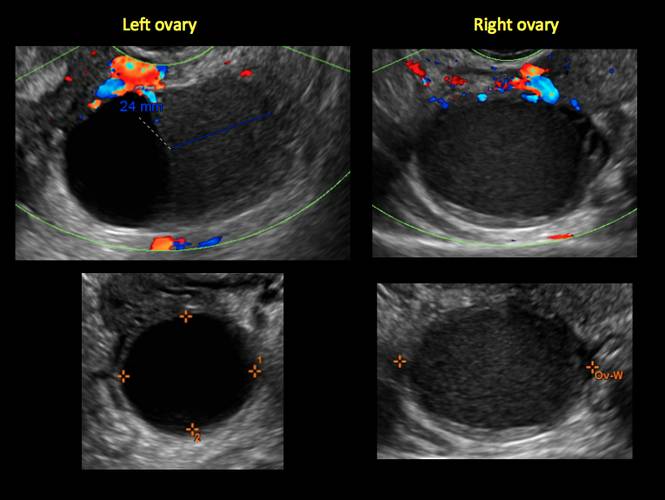

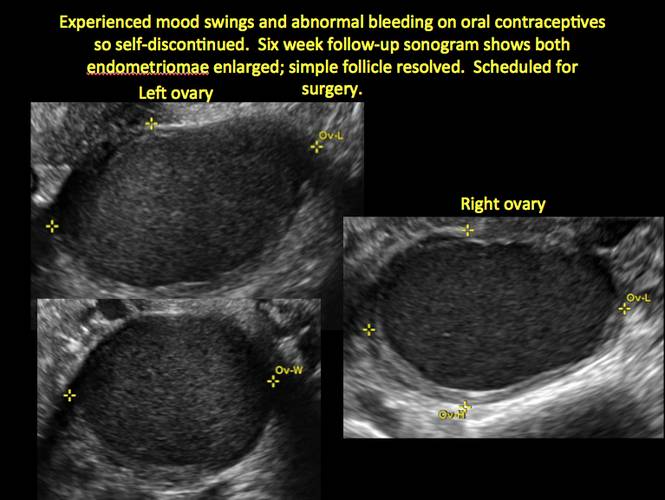

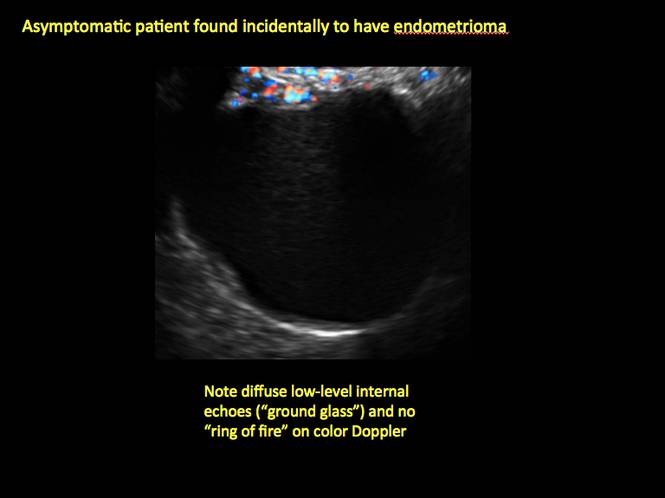

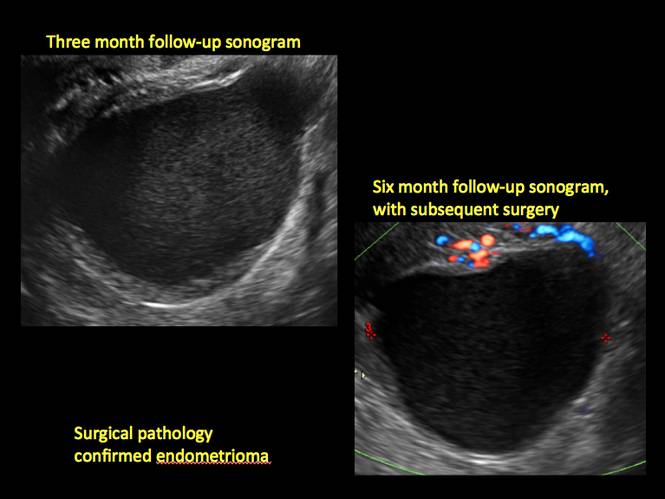

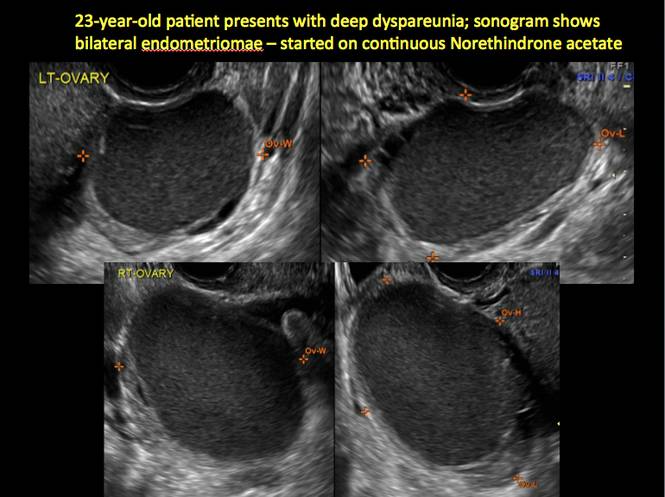

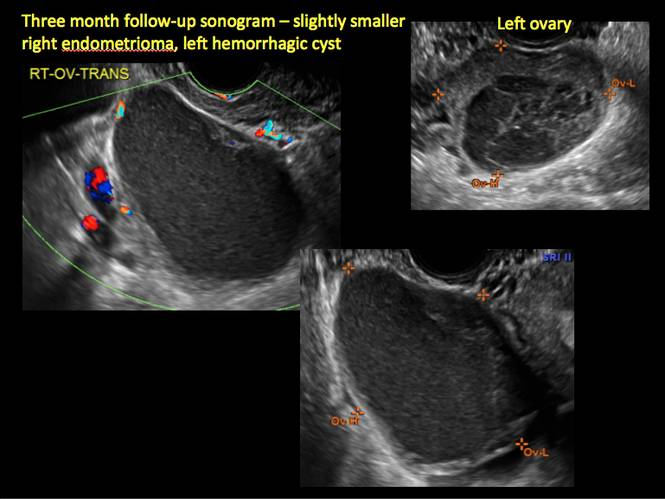

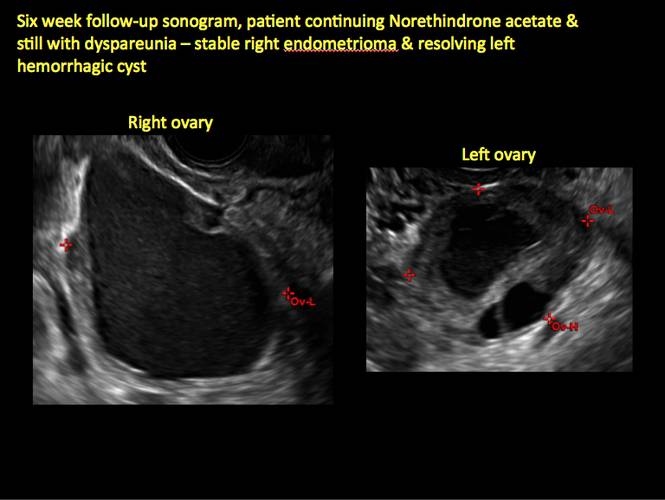

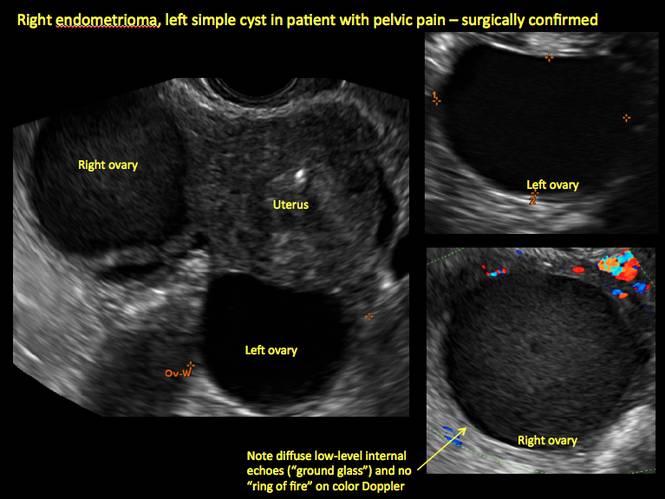

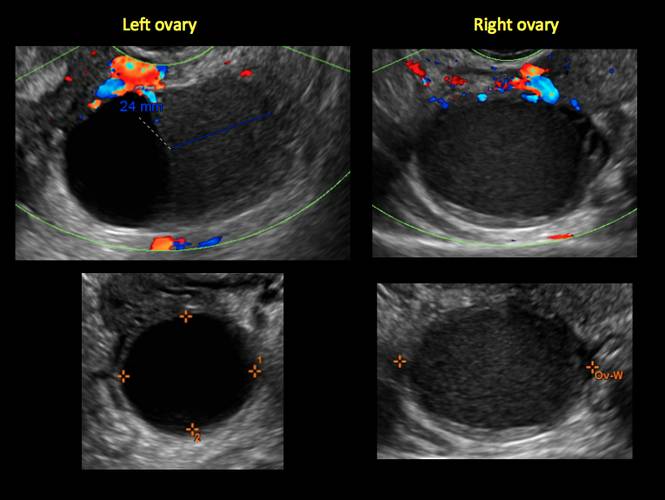

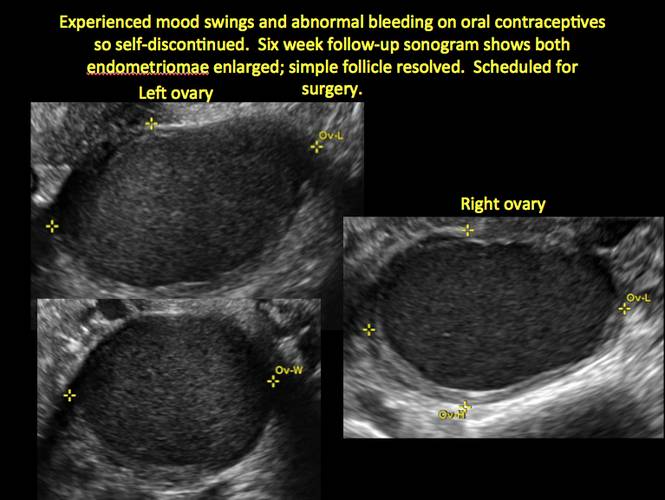

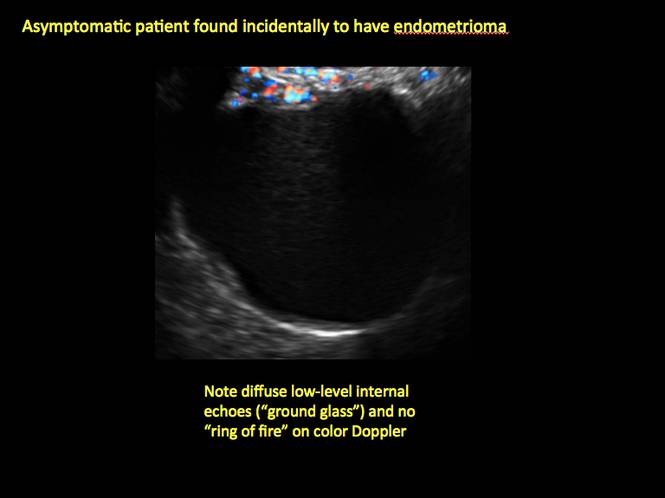

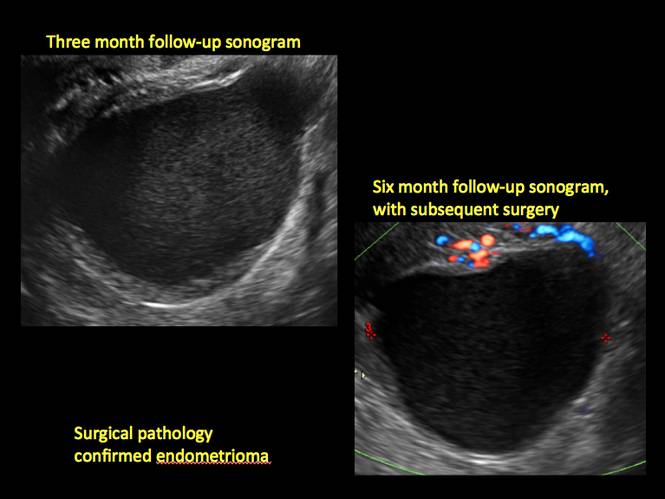

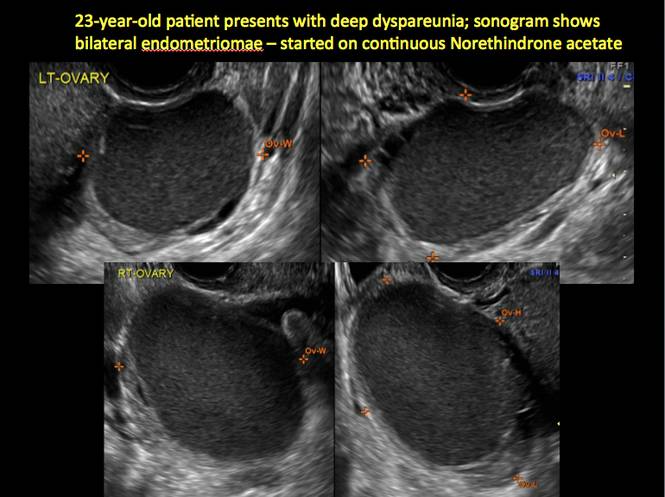

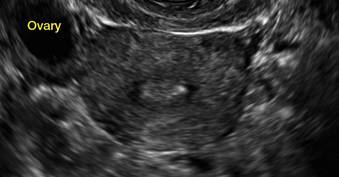

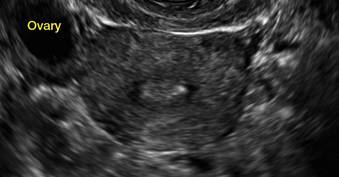

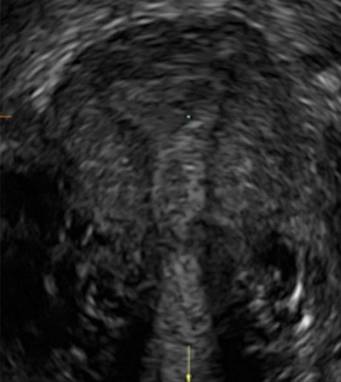

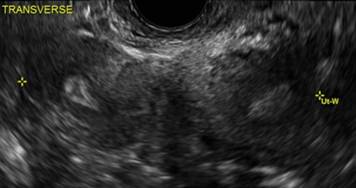

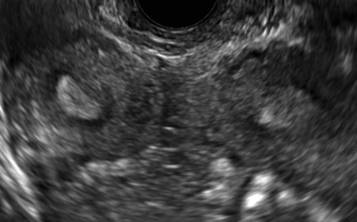

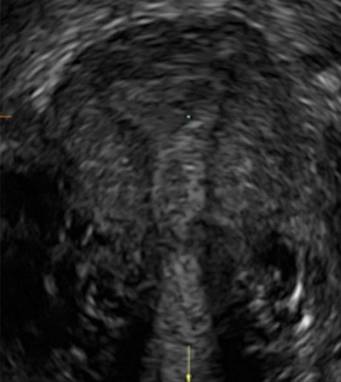

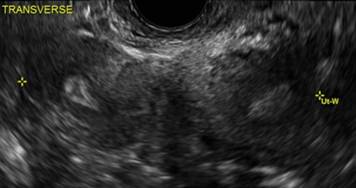

Endometriomas are common, typically benign, cysts that produce homogenous, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance on ultrasonography. No internal flow is apparent on color Doppler. The presence of tiny echogenic wall foci can distinguish an endometrioma from a hemorrhagic cyst.

Rarely, endometriomas may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs with cysts greater than 9 cm and in patients aged 45 years or older. A malignancy often exhibits rapid growth or the development of a solid nodule with flow on color Doppler.

Management

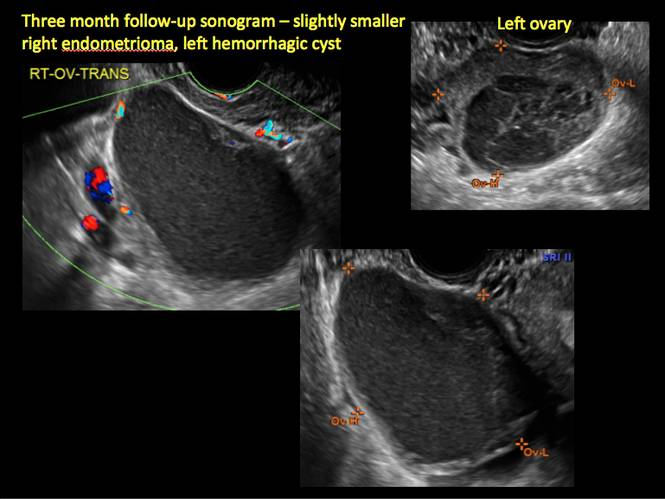

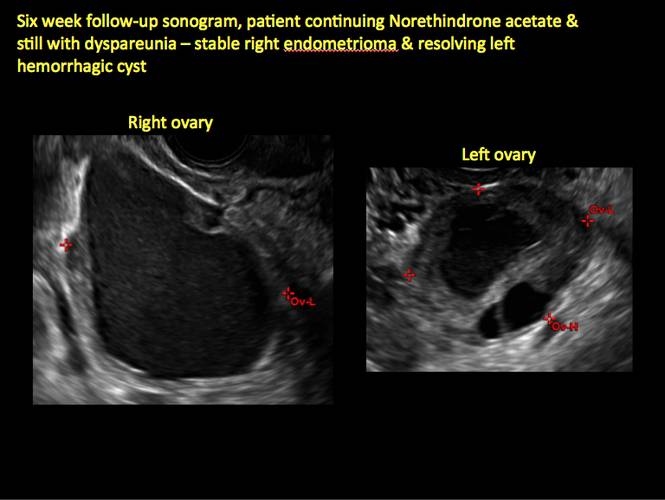

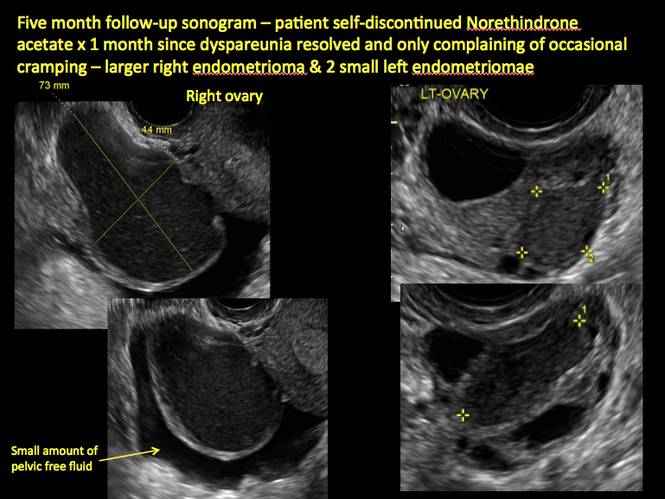

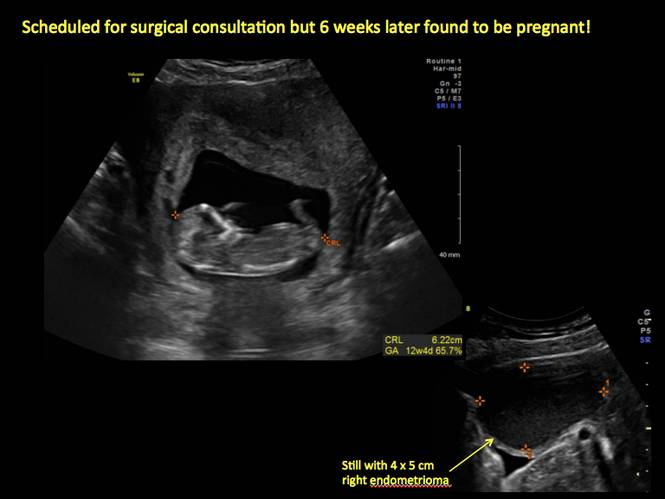

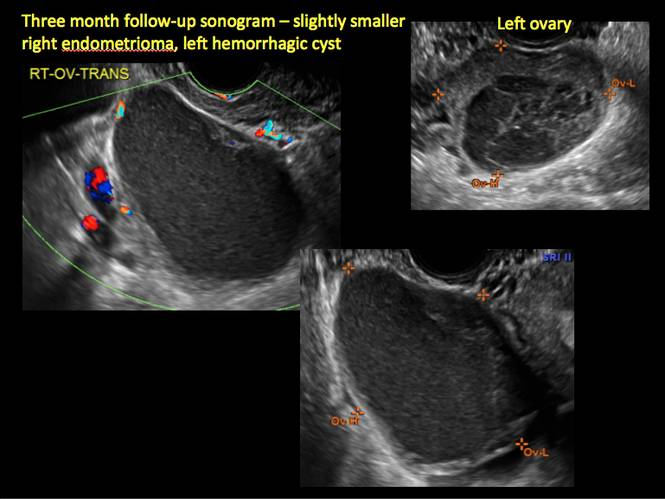

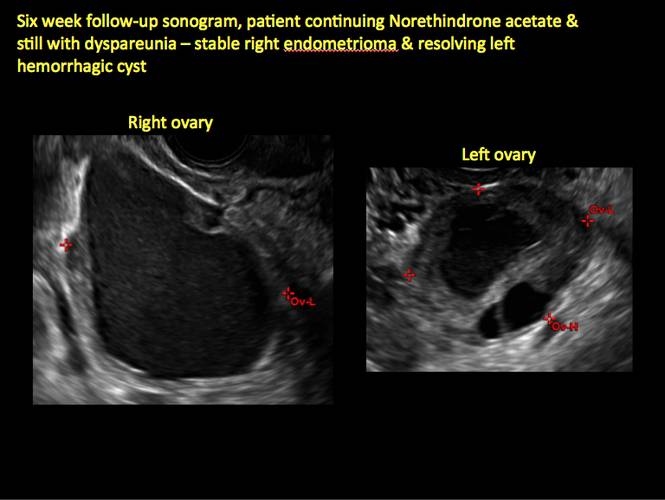

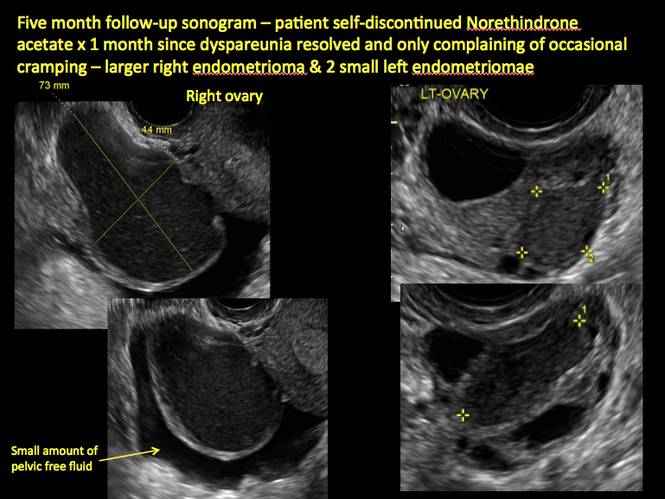

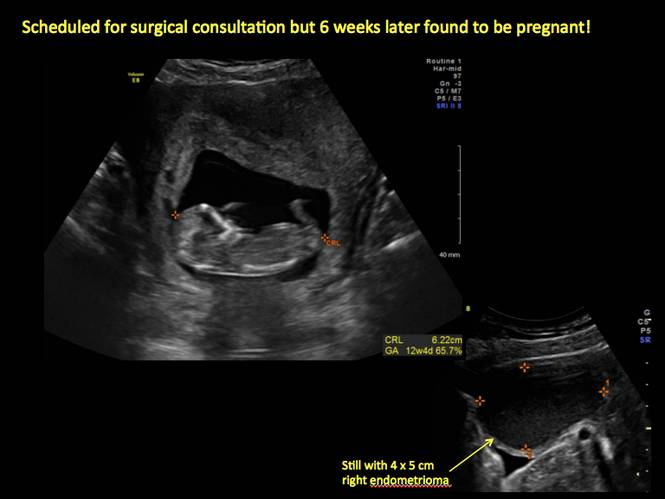

Although surgery remains the first-line management for women with symptomatic or enlarging endometriomas, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation, with continuous progestational treatment, in women with small (< 5 cm) asymptomatic endometriomas.

The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended1:

- Short-interval follow-up (6 to 12 weeks) in reproductive-aged women to ensure acute hemorrhagic cysts are not mistaken for endometriomas

- If not removed surgically, sonographic follow-up is recommended, with frequency of follow up based on patient age and symptoms and cyst size and characteristics.

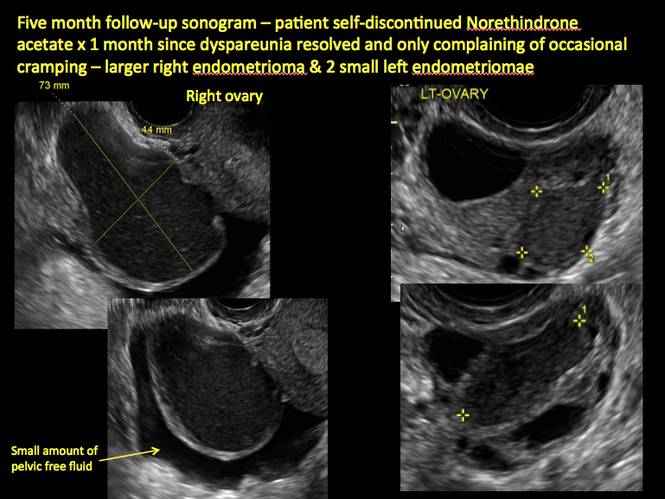

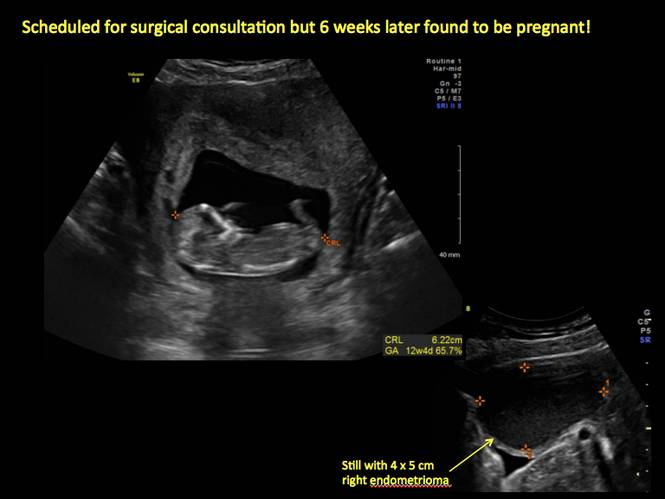

In FIGURES 1 through 11 (slides of image collections), we present several cases, including one of a 25-year-old patient presenting with pelvic pain and dyspareunia who was later found to have bilateral endometriomas.

Mature teratomas

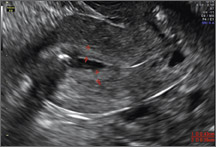

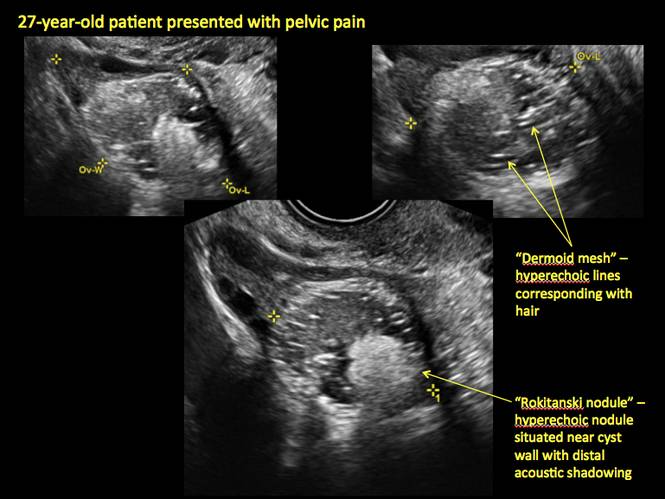

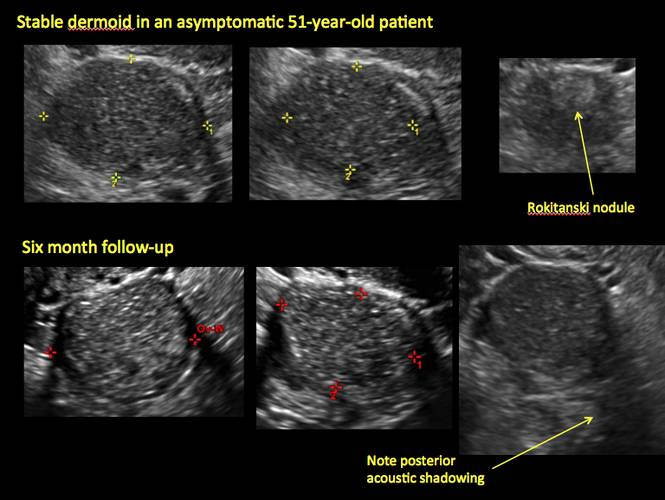

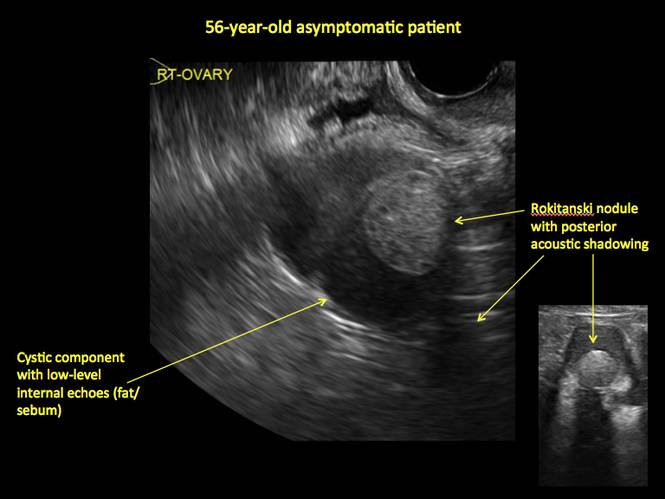

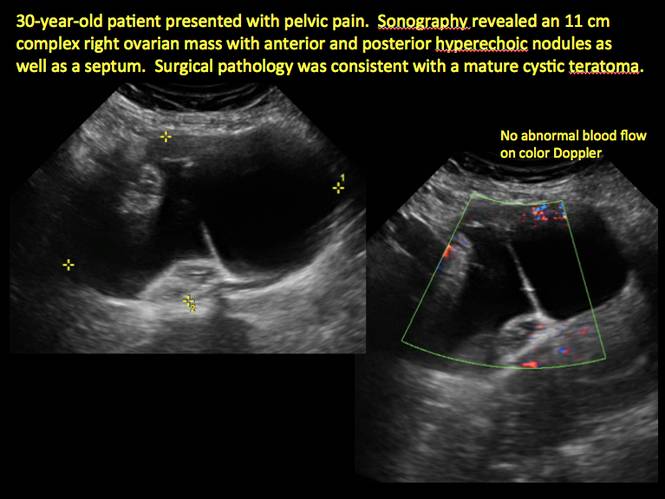

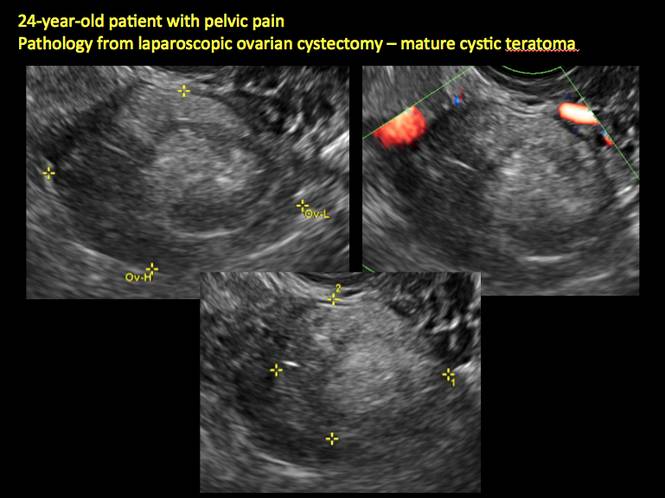

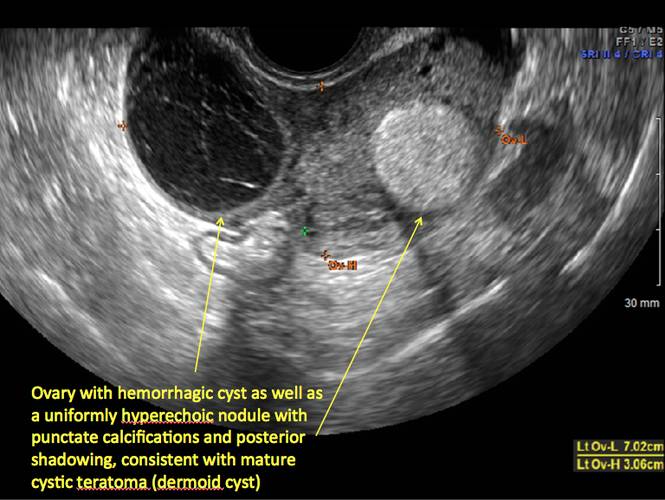

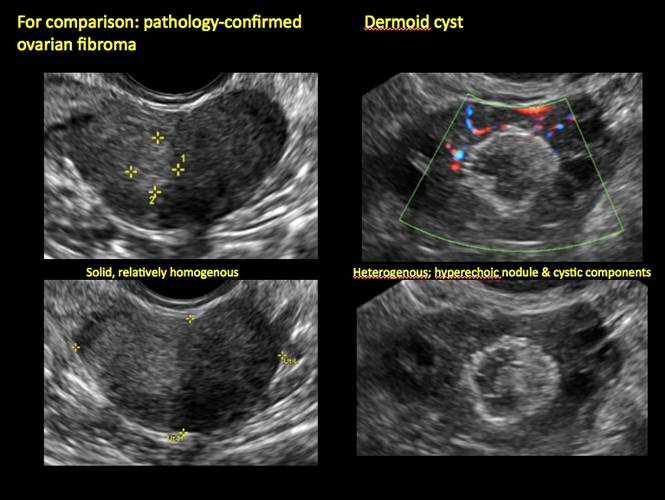

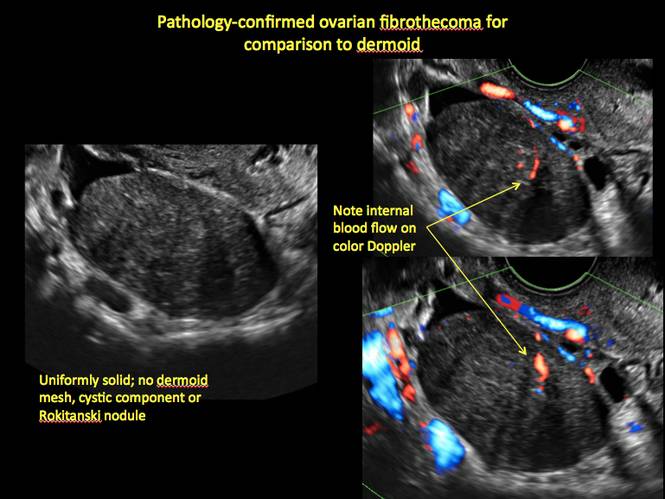

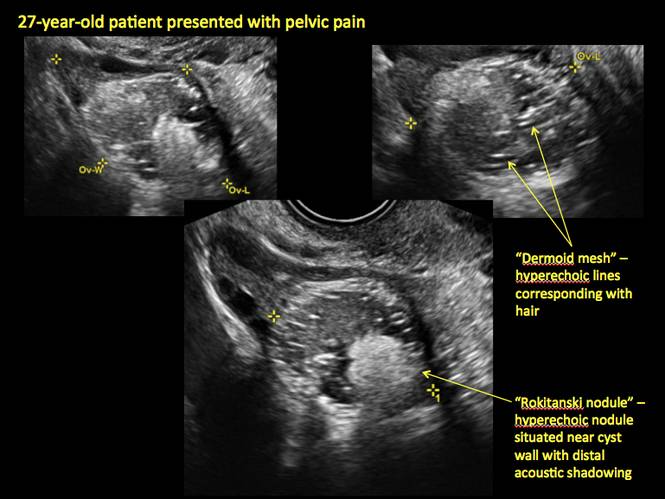

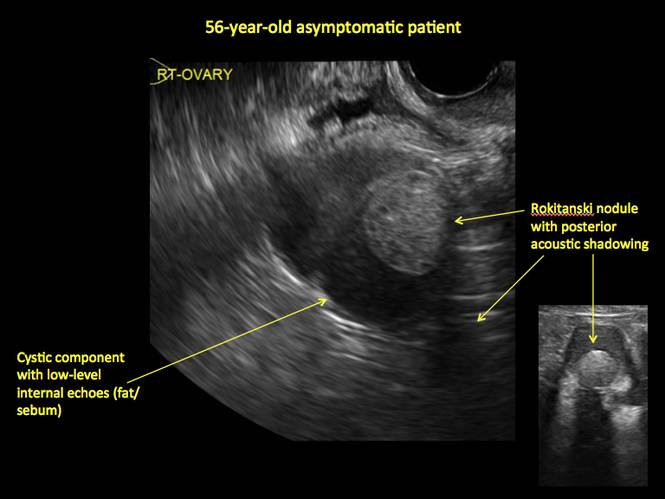

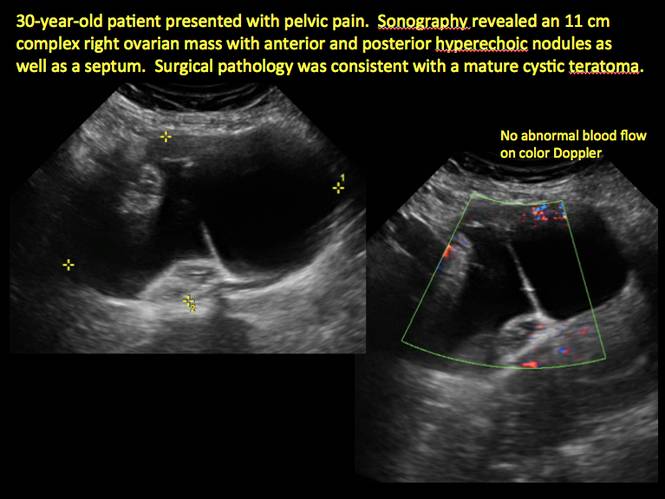

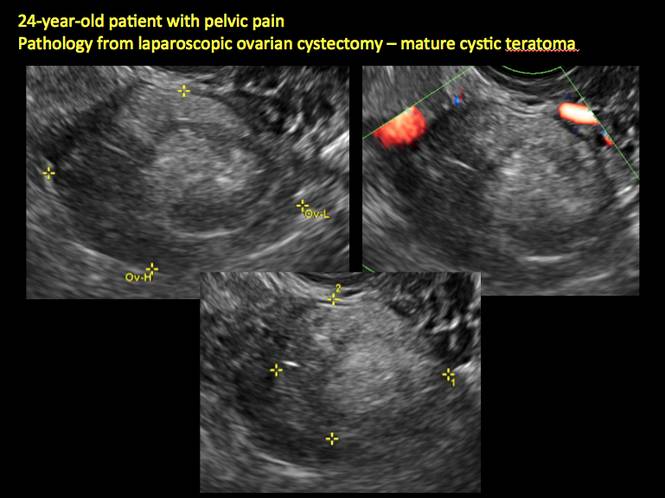

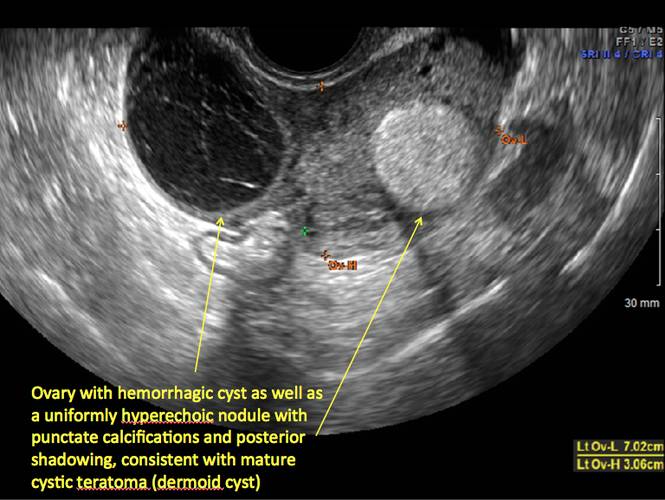

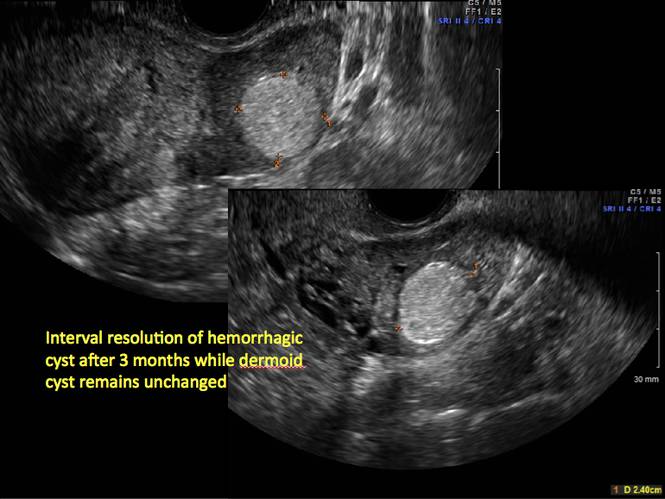

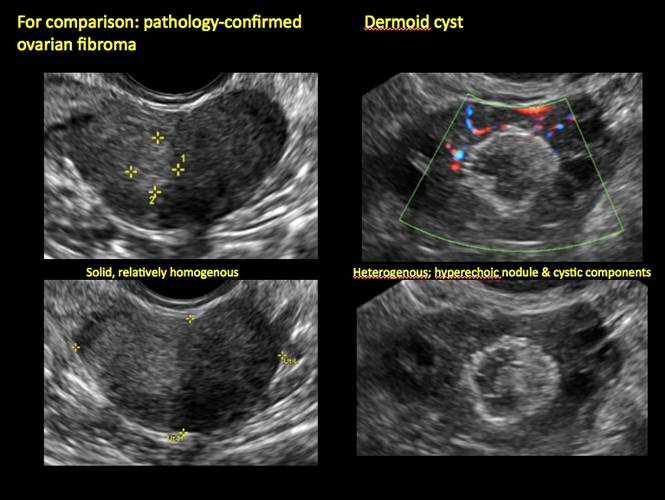

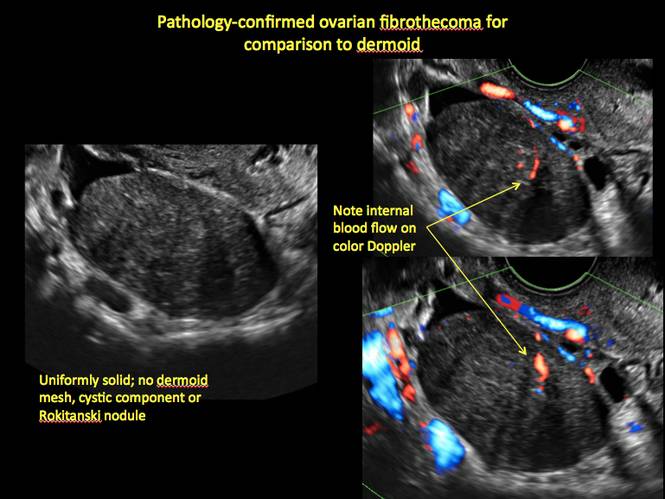

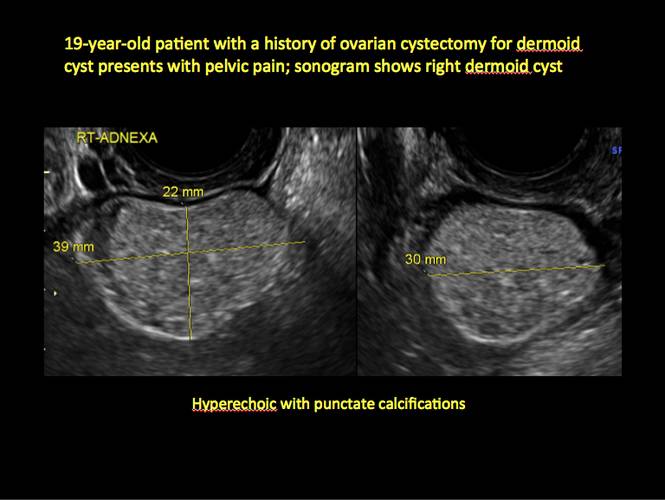

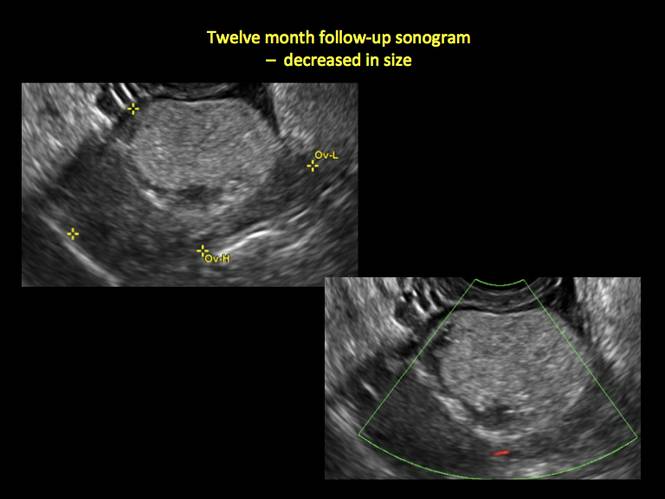

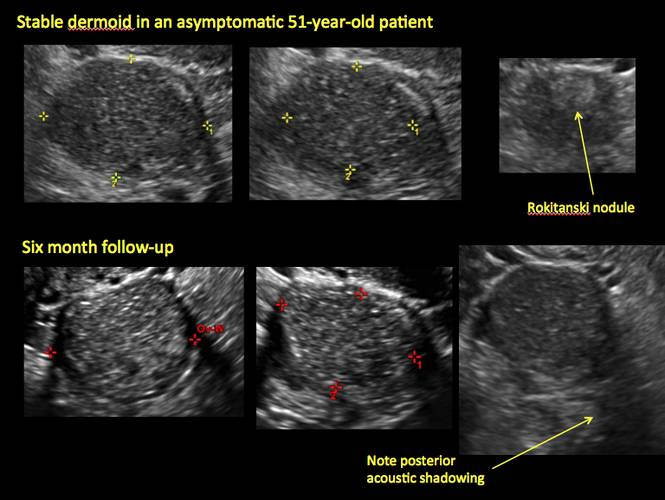

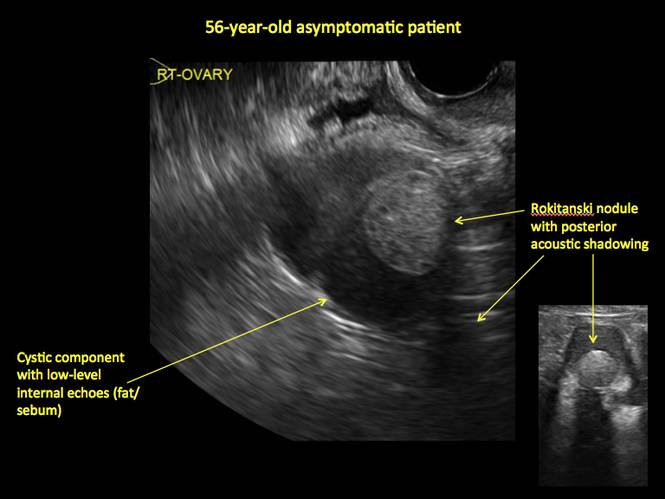

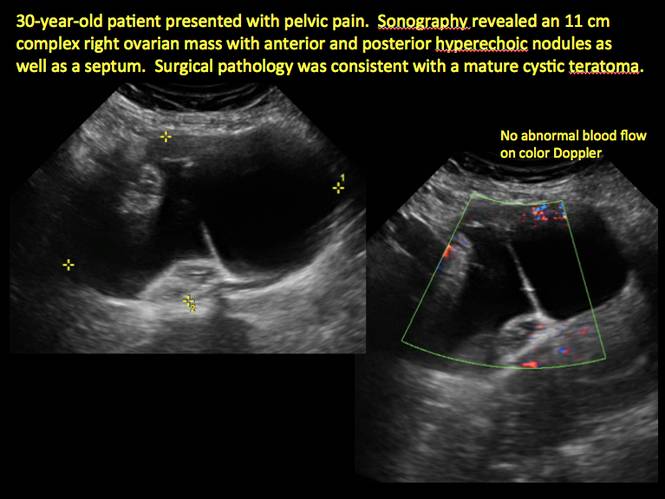

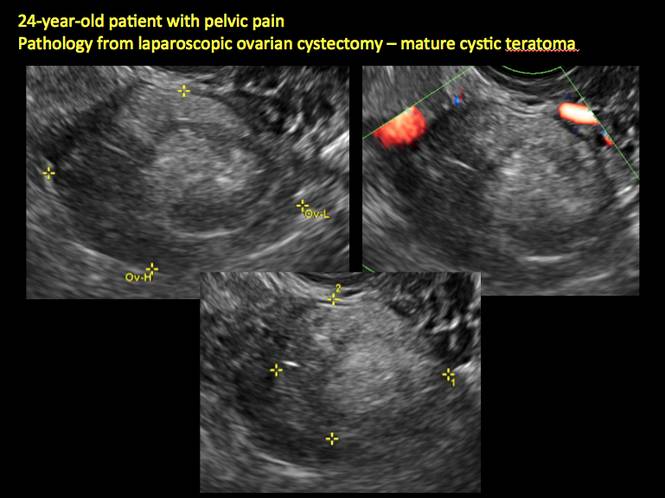

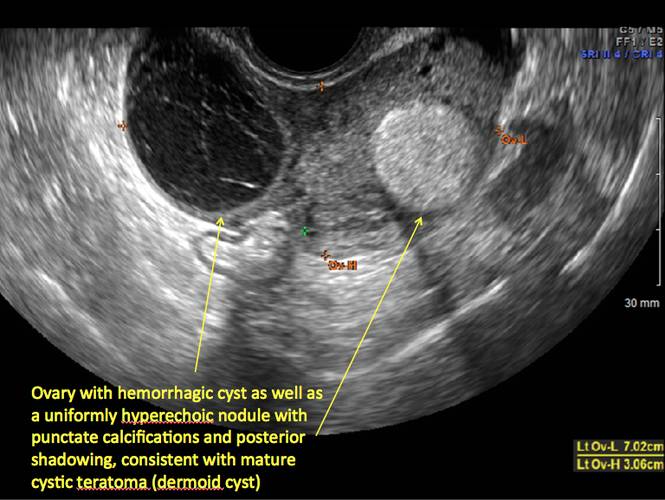

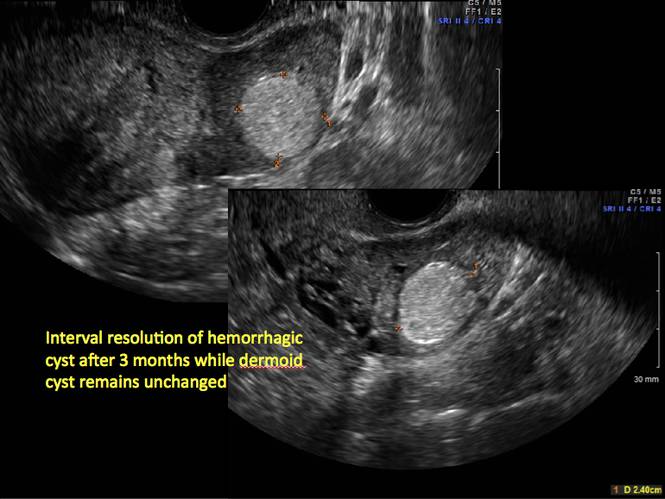

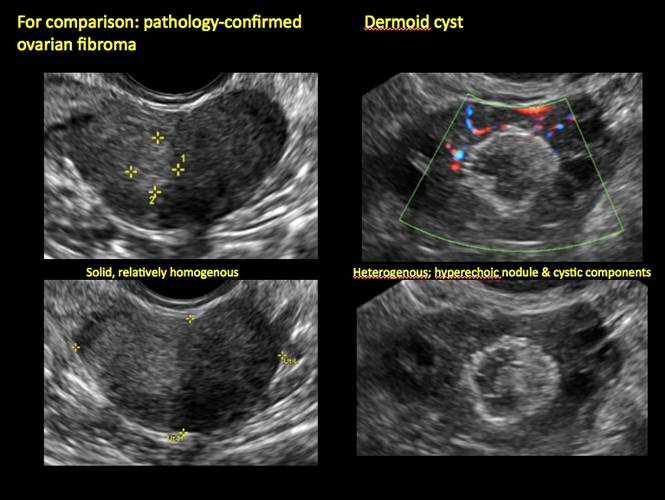

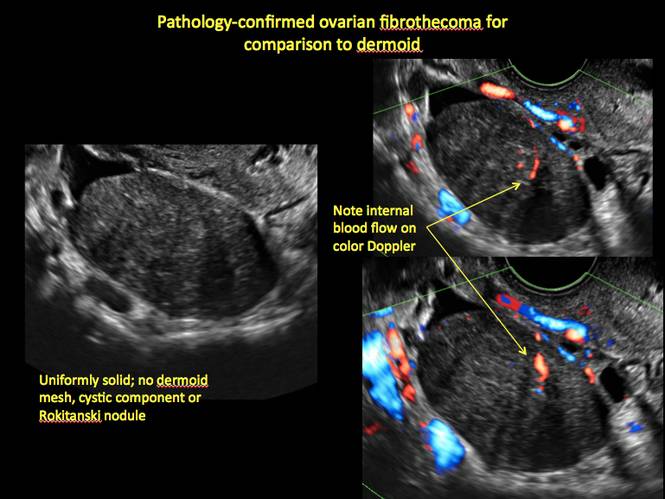

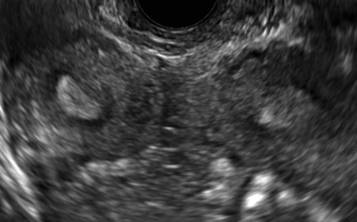

Mature cystic teratomas display several telltale signs on imaging, including:

- hyperechoic lines/dots (“dermoid mesh”) corresponding to hair/skeletal components

- “Rokitanski nodule” – a peripherally placed mass of sebum, bones, and hair

- posterior acoustic shadowing

- cystic or floating spherical structures

- no internal flow on color Doppler

Rarely, dermoid cysts may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs in cysts greater than 10 cm and in patients aged 50 years or older. Internal flow on color Doppler, branching, or invasion into adjacent structures can indicate malignancy.

Management

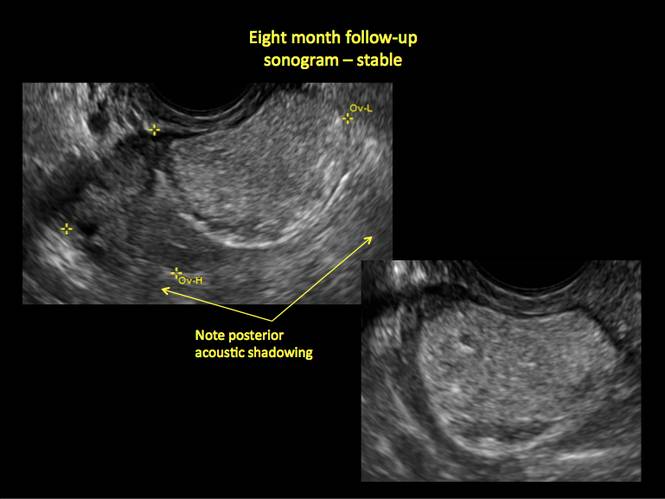

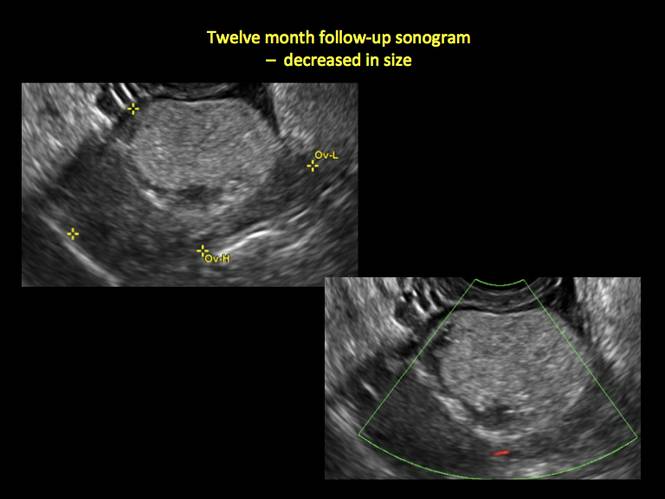

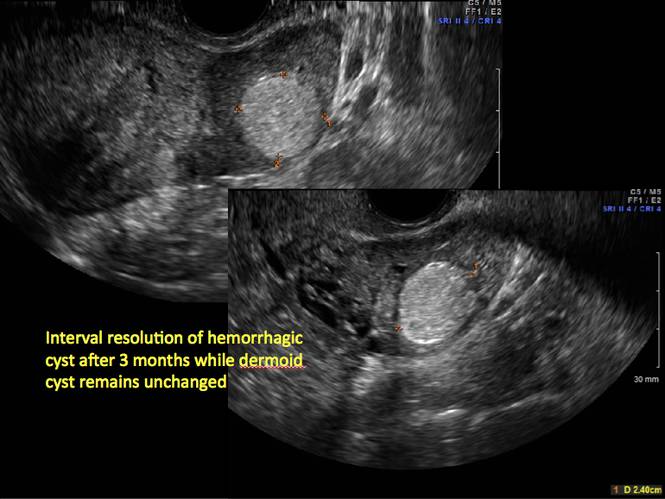

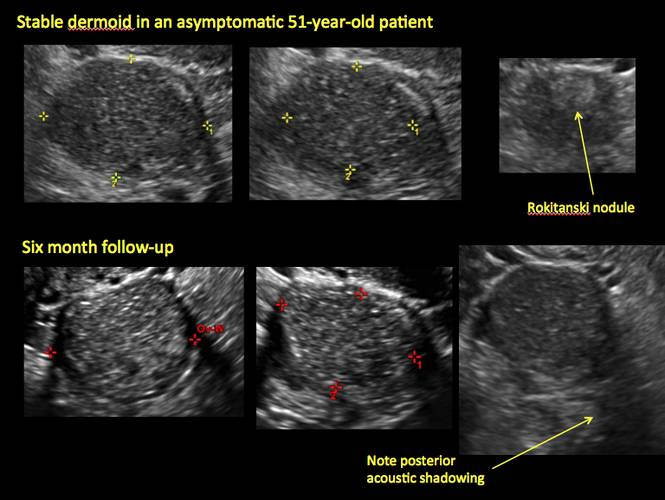

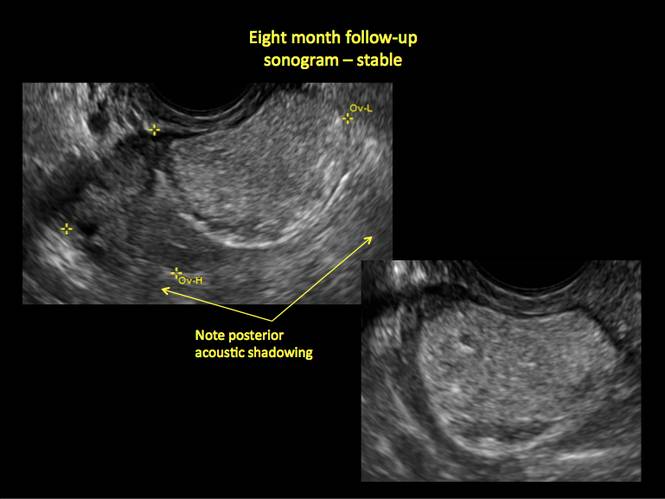

The traditional treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical. However, given the ability for accurate diagnosis with vaginal ultrasonography, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation in asymptomatic women with small dermoids.2

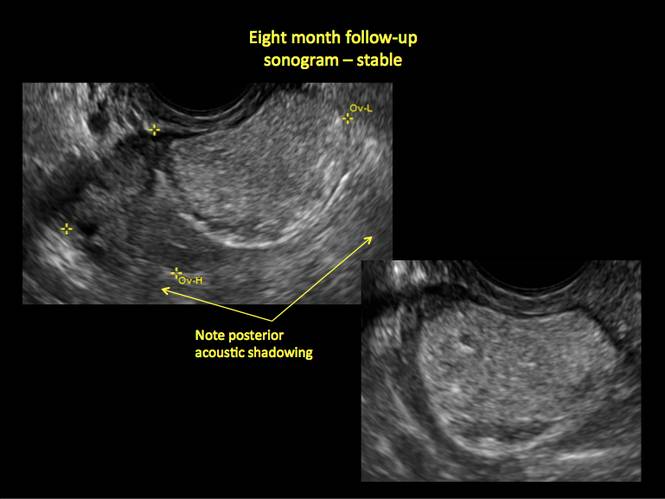

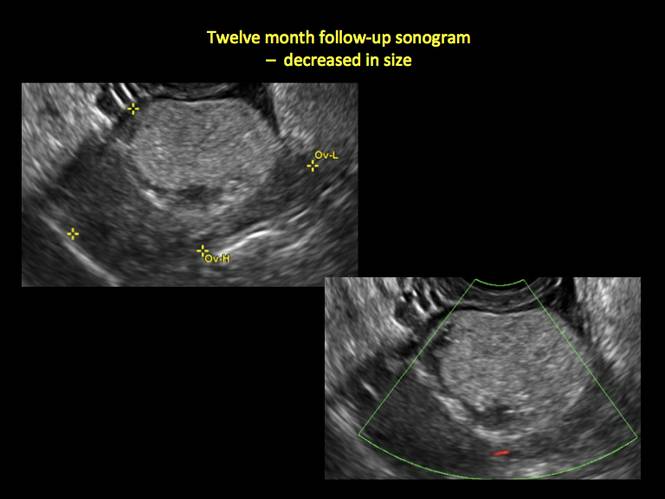

If the cyst is not surgically removed, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended initial sonographic follow up at no more than 6 months to 1 year to ensure no change in size or internal architecture.1

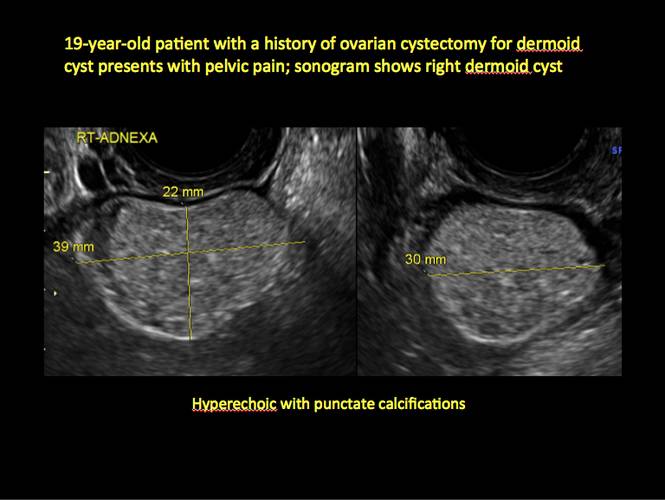

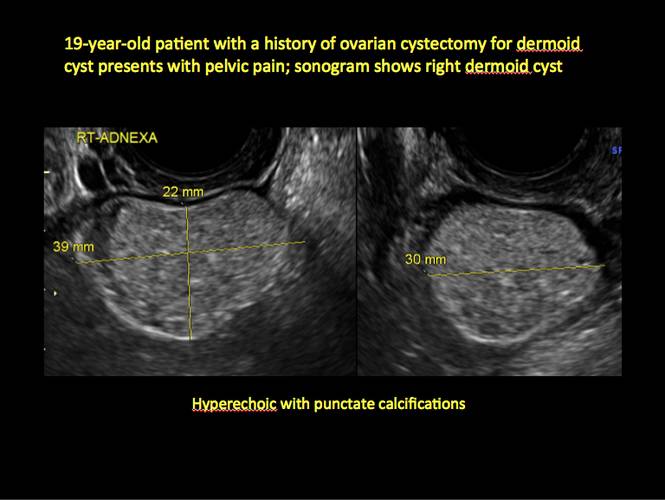

In FIGURES 12 through 24 below (slides of image collections), we offer imaging from the case presentation and follow-up of a 19-year-old patient with pelvic pain who has a history of ovarian cystectomy for dermoid cyst, as well as 6 additional case illustrations.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

2. Hoo WL, Yazbek WL, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(2): 235–240.

The preferred imaging method to evaluate the majority of adnexal cysts is ultrasonography, which can help characterize the cyst type. Common benign adnexal cyst types include simple, hemorrhagic, endometrioma, and mature teratoma (dermoid cyst). In this part 2 of a 4-part series on cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on imaging signs for, and follow-up of, endometriomas and mature teratomas.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas are common, typically benign, cysts that produce homogenous, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance on ultrasonography. No internal flow is apparent on color Doppler. The presence of tiny echogenic wall foci can distinguish an endometrioma from a hemorrhagic cyst.

Rarely, endometriomas may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs with cysts greater than 9 cm and in patients aged 45 years or older. A malignancy often exhibits rapid growth or the development of a solid nodule with flow on color Doppler.

Management

Although surgery remains the first-line management for women with symptomatic or enlarging endometriomas, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation, with continuous progestational treatment, in women with small (< 5 cm) asymptomatic endometriomas.

The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended1:

- Short-interval follow-up (6 to 12 weeks) in reproductive-aged women to ensure acute hemorrhagic cysts are not mistaken for endometriomas

- If not removed surgically, sonographic follow-up is recommended, with frequency of follow up based on patient age and symptoms and cyst size and characteristics.

In FIGURES 1 through 11 (slides of image collections), we present several cases, including one of a 25-year-old patient presenting with pelvic pain and dyspareunia who was later found to have bilateral endometriomas.

Mature teratomas

Mature cystic teratomas display several telltale signs on imaging, including:

- hyperechoic lines/dots (“dermoid mesh”) corresponding to hair/skeletal components

- “Rokitanski nodule” – a peripherally placed mass of sebum, bones, and hair

- posterior acoustic shadowing

- cystic or floating spherical structures

- no internal flow on color Doppler

Rarely, dermoid cysts may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs in cysts greater than 10 cm and in patients aged 50 years or older. Internal flow on color Doppler, branching, or invasion into adjacent structures can indicate malignancy.

Management

The traditional treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical. However, given the ability for accurate diagnosis with vaginal ultrasonography, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation in asymptomatic women with small dermoids.2

If the cyst is not surgically removed, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended initial sonographic follow up at no more than 6 months to 1 year to ensure no change in size or internal architecture.1

In FIGURES 12 through 24 below (slides of image collections), we offer imaging from the case presentation and follow-up of a 19-year-old patient with pelvic pain who has a history of ovarian cystectomy for dermoid cyst, as well as 6 additional case illustrations.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The preferred imaging method to evaluate the majority of adnexal cysts is ultrasonography, which can help characterize the cyst type. Common benign adnexal cyst types include simple, hemorrhagic, endometrioma, and mature teratoma (dermoid cyst). In this part 2 of a 4-part series on cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on imaging signs for, and follow-up of, endometriomas and mature teratomas.

Endometriomas

Endometriomas are common, typically benign, cysts that produce homogenous, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance on ultrasonography. No internal flow is apparent on color Doppler. The presence of tiny echogenic wall foci can distinguish an endometrioma from a hemorrhagic cyst.

Rarely, endometriomas may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs with cysts greater than 9 cm and in patients aged 45 years or older. A malignancy often exhibits rapid growth or the development of a solid nodule with flow on color Doppler.

Management

Although surgery remains the first-line management for women with symptomatic or enlarging endometriomas, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation, with continuous progestational treatment, in women with small (< 5 cm) asymptomatic endometriomas.

The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended1:

- Short-interval follow-up (6 to 12 weeks) in reproductive-aged women to ensure acute hemorrhagic cysts are not mistaken for endometriomas

- If not removed surgically, sonographic follow-up is recommended, with frequency of follow up based on patient age and symptoms and cyst size and characteristics.

In FIGURES 1 through 11 (slides of image collections), we present several cases, including one of a 25-year-old patient presenting with pelvic pain and dyspareunia who was later found to have bilateral endometriomas.

Mature teratomas

Mature cystic teratomas display several telltale signs on imaging, including:

- hyperechoic lines/dots (“dermoid mesh”) corresponding to hair/skeletal components

- “Rokitanski nodule” – a peripherally placed mass of sebum, bones, and hair

- posterior acoustic shadowing

- cystic or floating spherical structures

- no internal flow on color Doppler

Rarely, dermoid cysts may undergo malignant transformation. Usually this occurs in cysts greater than 10 cm and in patients aged 50 years or older. Internal flow on color Doppler, branching, or invasion into adjacent structures can indicate malignancy.

Management

The traditional treatment for dermoid cysts is surgical. However, given the ability for accurate diagnosis with vaginal ultrasonography, there appears to be a role for sonographic observation in asymptomatic women with small dermoids.2

If the cyst is not surgically removed, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound 2010 Consensus Conference Statement recommended initial sonographic follow up at no more than 6 months to 1 year to ensure no change in size or internal architecture.1

In FIGURES 12 through 24 below (slides of image collections), we offer imaging from the case presentation and follow-up of a 19-year-old patient with pelvic pain who has a history of ovarian cystectomy for dermoid cyst, as well as 6 additional case illustrations.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Figure 9

Figure 10

Figure 11

Figure 12

Figure 13

Figure 14

Figure 15

Figure 16

Figure 17

Figure 18

Figure 19

Figure 20

Figure 21

Figure 22

Figure 23

Figure 24

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

2. Hoo WL, Yazbek WL, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(2): 235–240.

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

2. Hoo WL, Yazbek WL, Holland T, Mavrelos D, Tong EN, Jurkovic D. Expectant management of ultrasonically diagnosed ovarian dermoid cysts: is it possible to predict outcome? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;36(2): 235–240.

Does a family history of both breast and prostate cancer (vs breast only) put a woman at greater risk for future breast cancer?

The most common invasive cancers diagnosed in US women and men are breast and prostate cancers, respectively. This analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study involved 78,171 women aged 50 to 79 years at enrollment. Invasive breast cancer was diagnosed in 3,506 women (4.5%) during a median of 132 months of follow-up. Having a first-degree relative with breast or prostate cancer was associated with an elevated adjusted hazard ratio of breast cancer of 1.42 and 1.14, respectively. Women who had a history of both cancers among first-degree relatives had an adjusted HR of 1.78. Although the difference did not achieve statistical significance, there was a suggestion that the elevated risk for breast cancer associated with relatives with prostate and breast cancer was higher in African-American women compared with white women. The risk for breast cancer was not elevated in women who had first-degree relatives with cancers other than breast or prostate.

The authors point out that another study also reported that a family history that includes both cancers is associated with a greater elevation in the risk for breast cancer than family history of prostate cancer alone. Although BRCA 1 and 2 mutations are associated with an elevated risk of not only breast but also prostate cancer, the authors indicate that such mutations account for only a small proportion of the observed aggregation of breast and prostate cancer in first-degree relatives of women with breast cancer in their analysis.

What this evidence means for practice

The associations observed by these authors underscore that, when taking family histories, women’s health clinicians should pay attention not only to breast but also to prostate cancer, and counsel patients regarding risk and screening practices accordingly.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The most common invasive cancers diagnosed in US women and men are breast and prostate cancers, respectively. This analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study involved 78,171 women aged 50 to 79 years at enrollment. Invasive breast cancer was diagnosed in 3,506 women (4.5%) during a median of 132 months of follow-up. Having a first-degree relative with breast or prostate cancer was associated with an elevated adjusted hazard ratio of breast cancer of 1.42 and 1.14, respectively. Women who had a history of both cancers among first-degree relatives had an adjusted HR of 1.78. Although the difference did not achieve statistical significance, there was a suggestion that the elevated risk for breast cancer associated with relatives with prostate and breast cancer was higher in African-American women compared with white women. The risk for breast cancer was not elevated in women who had first-degree relatives with cancers other than breast or prostate.

The authors point out that another study also reported that a family history that includes both cancers is associated with a greater elevation in the risk for breast cancer than family history of prostate cancer alone. Although BRCA 1 and 2 mutations are associated with an elevated risk of not only breast but also prostate cancer, the authors indicate that such mutations account for only a small proportion of the observed aggregation of breast and prostate cancer in first-degree relatives of women with breast cancer in their analysis.

What this evidence means for practice

The associations observed by these authors underscore that, when taking family histories, women’s health clinicians should pay attention not only to breast but also to prostate cancer, and counsel patients regarding risk and screening practices accordingly.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The most common invasive cancers diagnosed in US women and men are breast and prostate cancers, respectively. This analysis from the Women’s Health Initiative observational study involved 78,171 women aged 50 to 79 years at enrollment. Invasive breast cancer was diagnosed in 3,506 women (4.5%) during a median of 132 months of follow-up. Having a first-degree relative with breast or prostate cancer was associated with an elevated adjusted hazard ratio of breast cancer of 1.42 and 1.14, respectively. Women who had a history of both cancers among first-degree relatives had an adjusted HR of 1.78. Although the difference did not achieve statistical significance, there was a suggestion that the elevated risk for breast cancer associated with relatives with prostate and breast cancer was higher in African-American women compared with white women. The risk for breast cancer was not elevated in women who had first-degree relatives with cancers other than breast or prostate.

The authors point out that another study also reported that a family history that includes both cancers is associated with a greater elevation in the risk for breast cancer than family history of prostate cancer alone. Although BRCA 1 and 2 mutations are associated with an elevated risk of not only breast but also prostate cancer, the authors indicate that such mutations account for only a small proportion of the observed aggregation of breast and prostate cancer in first-degree relatives of women with breast cancer in their analysis.

What this evidence means for practice

The associations observed by these authors underscore that, when taking family histories, women’s health clinicians should pay attention not only to breast but also to prostate cancer, and counsel patients regarding risk and screening practices accordingly.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Association between breast cancer and depression may last as long as 8 years

Although it is generally accepted that women given a diagnosis of breast cancer are vulnerable to depression, studies investigating this association have been hampered by cross-sectional design, a short duration of follow-up, or a lack of clinical detail. In a new study from Denmark, Suppli and colleagues used the national health database to identify almost 2 million women with no history of cancer or inpatient care for depression whom they followed from 1988 to 2011. They identified incident cases of breast cancer in this population, as well as prescriptions for antidepressants and inpatient care for depression during the follow-up period.1

What they found may surprise you: Not only were women given a diagnosis of breast cancer three times more likely to fill a prescription for an antidepressant in the first year after diagnosis (rate ratio, 3.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.95–3.22), but the rate ratio remained significantly elevated as far out as 8 years after diagnosis.

Suppli and colleagues also found that the rate ratio for hospitalization for depression was 1.70 in the first year (95% CI, 1.41–2.05). It, too, remained significantly elevated as far out as 5 years after diagnosis.

Women who were age 70 or older at the time of diagnosis were more likely to be treated for depression and to be hospitalized. Other risk factors for depression included comorbidity, node-positive disease, basic and vocational educational levels, and living alone.

The type of cancer treatment the women underwent appeared to have no bearing on the risk of depression.

What we can do about the risk of depression in cancer patients

The finding that breast cancer is associated with depression is not new, but the magnitude of the association documented in this large study from a Danish national registry clarifies the role of women’s health providers: We need to be mindful of the long-term impact this disease can have on our patients’ mental health so that we are better able to recognize and proactively address mood disorders in this vulnerable population.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Suppli NP, Johansen C, Christensen J, Kessing LV, Kroman N, Dalton SO. Increased risk of depression after breast cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of associated factors in Denmark. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3831–3839.

Although it is generally accepted that women given a diagnosis of breast cancer are vulnerable to depression, studies investigating this association have been hampered by cross-sectional design, a short duration of follow-up, or a lack of clinical detail. In a new study from Denmark, Suppli and colleagues used the national health database to identify almost 2 million women with no history of cancer or inpatient care for depression whom they followed from 1988 to 2011. They identified incident cases of breast cancer in this population, as well as prescriptions for antidepressants and inpatient care for depression during the follow-up period.1

What they found may surprise you: Not only were women given a diagnosis of breast cancer three times more likely to fill a prescription for an antidepressant in the first year after diagnosis (rate ratio, 3.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.95–3.22), but the rate ratio remained significantly elevated as far out as 8 years after diagnosis.

Suppli and colleagues also found that the rate ratio for hospitalization for depression was 1.70 in the first year (95% CI, 1.41–2.05). It, too, remained significantly elevated as far out as 5 years after diagnosis.

Women who were age 70 or older at the time of diagnosis were more likely to be treated for depression and to be hospitalized. Other risk factors for depression included comorbidity, node-positive disease, basic and vocational educational levels, and living alone.

The type of cancer treatment the women underwent appeared to have no bearing on the risk of depression.

What we can do about the risk of depression in cancer patients

The finding that breast cancer is associated with depression is not new, but the magnitude of the association documented in this large study from a Danish national registry clarifies the role of women’s health providers: We need to be mindful of the long-term impact this disease can have on our patients’ mental health so that we are better able to recognize and proactively address mood disorders in this vulnerable population.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Although it is generally accepted that women given a diagnosis of breast cancer are vulnerable to depression, studies investigating this association have been hampered by cross-sectional design, a short duration of follow-up, or a lack of clinical detail. In a new study from Denmark, Suppli and colleagues used the national health database to identify almost 2 million women with no history of cancer or inpatient care for depression whom they followed from 1988 to 2011. They identified incident cases of breast cancer in this population, as well as prescriptions for antidepressants and inpatient care for depression during the follow-up period.1

What they found may surprise you: Not only were women given a diagnosis of breast cancer three times more likely to fill a prescription for an antidepressant in the first year after diagnosis (rate ratio, 3.09; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.95–3.22), but the rate ratio remained significantly elevated as far out as 8 years after diagnosis.

Suppli and colleagues also found that the rate ratio for hospitalization for depression was 1.70 in the first year (95% CI, 1.41–2.05). It, too, remained significantly elevated as far out as 5 years after diagnosis.

Women who were age 70 or older at the time of diagnosis were more likely to be treated for depression and to be hospitalized. Other risk factors for depression included comorbidity, node-positive disease, basic and vocational educational levels, and living alone.

The type of cancer treatment the women underwent appeared to have no bearing on the risk of depression.

What we can do about the risk of depression in cancer patients

The finding that breast cancer is associated with depression is not new, but the magnitude of the association documented in this large study from a Danish national registry clarifies the role of women’s health providers: We need to be mindful of the long-term impact this disease can have on our patients’ mental health so that we are better able to recognize and proactively address mood disorders in this vulnerable population.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

- Suppli NP, Johansen C, Christensen J, Kessing LV, Kroman N, Dalton SO. Increased risk of depression after breast cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of associated factors in Denmark. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3831–3839.

Reference

- Suppli NP, Johansen C, Christensen J, Kessing LV, Kroman N, Dalton SO. Increased risk of depression after breast cancer: a nationwide population-based cohort study of associated factors in Denmark. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(34):3831–3839.

Telltale sonographic features of simple and hemorrhagic cysts

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts, given its ability to accurately characterize their various aspects:

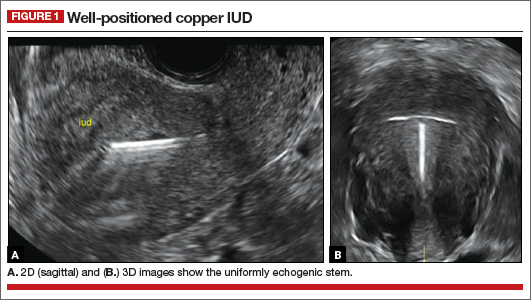

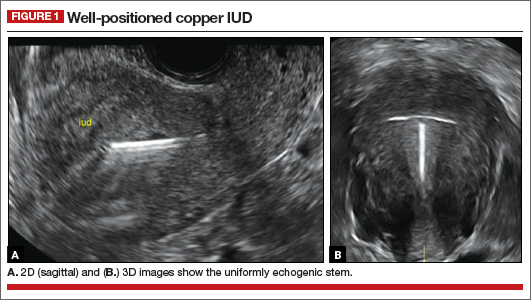

- Simple cysts are uniformly hypoechoic, with thin walls and no blood flow on color Doppler (FIGURE 1).

- Hemorrhagic cysts produce lacy/reticular echoes and clot with concave margins

(FIGURE 2). - Mature cystic teratomas produce hyperechoic lines and dots, sometimes known as “dermoid mesh,” acoustic shadowing, and a hyperechoic nodule (FIGURE 3).

- Endometriomas produce diffuse, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance (FIGURE 4).

In the first of this 4-part series on the sonographic features of cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on simple and hemorrhagic cysts. In the following parts we will highlight:

- mature cystic teratomas and endometriomas (Part 2)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3)

- cystadenoma and ovarian neoplasia (Part 4).

An earlier installment of this series entitled “Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: one entity with many appearances” (May 2014) also focused on cystic pathology.

Figure 1: Simple cyst

A simple cyst in a 32-year-old patient. Figure 2: Hemorrhagic cyst

Note the lacy/reticular internal echoes and lack of internal blood flow on color Doppler. Figure 3: Cystic teratoma

This cyst exhibits the “dermoid mesh” and hyperechoic lines that correspond with hair. Figure 4: Endometrioma

Note diffuse low-level internal echoes (“ground glass”) and no “ring of fire” on color Doppler. |

Characteristics of simple cysts

A simple cyst typically is round or oval, anechoic, and has smooth, thin walls. It contains no solid component or septation (with rare exceptions), and no internal flow is visible on color Doppler imaging.

Levine and colleagues observed that simple adnexal cysts as large as 10 cm carry a risk of malignancy of less than 1%, regardless of the age of the patient. In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement,1 the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies for women with simple cysts:

Reproductive-aged women

- Cyst <3 cm: No action necessary; the cyst is a normal physiologic finding and should be referred to as a follicle.

- 3–5 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 5–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is highly likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Postmenopausal women

- <1 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 1–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Characteristics of hemorrhagic cysts

These cysts can be quite variable in appearance. Among their sonographic features:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, or fishnet) internal echoes, due to fibrin strands

- solid-appearing areas with concave margins

- on color Doppler, there may be circumferential peripheral flow (“ring of fire”) and no internal flow.

In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies1:

Premenopausal women

- ≤5 cm: No follow-up imaging unless the diagnosis is uncertain.

- >5 cm: Short-interval follow-up ultrasound (6–12 weeks).

Recently menopausal women

- Any size: Follow-up ultrasound in 6–12 weeks to ensure resolution.

Later postmenopausal women

- Any size: Consider surgical removal, as the cyst may be neoplastic.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts, given its ability to accurately characterize their various aspects:

- Simple cysts are uniformly hypoechoic, with thin walls and no blood flow on color Doppler (FIGURE 1).

- Hemorrhagic cysts produce lacy/reticular echoes and clot with concave margins

(FIGURE 2). - Mature cystic teratomas produce hyperechoic lines and dots, sometimes known as “dermoid mesh,” acoustic shadowing, and a hyperechoic nodule (FIGURE 3).

- Endometriomas produce diffuse, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance (FIGURE 4).

In the first of this 4-part series on the sonographic features of cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on simple and hemorrhagic cysts. In the following parts we will highlight:

- mature cystic teratomas and endometriomas (Part 2)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3)

- cystadenoma and ovarian neoplasia (Part 4).

An earlier installment of this series entitled “Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: one entity with many appearances” (May 2014) also focused on cystic pathology.

Figure 1: Simple cyst

A simple cyst in a 32-year-old patient. Figure 2: Hemorrhagic cyst

Note the lacy/reticular internal echoes and lack of internal blood flow on color Doppler. Figure 3: Cystic teratoma

This cyst exhibits the “dermoid mesh” and hyperechoic lines that correspond with hair. Figure 4: Endometrioma

Note diffuse low-level internal echoes (“ground glass”) and no “ring of fire” on color Doppler. |

Characteristics of simple cysts

A simple cyst typically is round or oval, anechoic, and has smooth, thin walls. It contains no solid component or septation (with rare exceptions), and no internal flow is visible on color Doppler imaging.

Levine and colleagues observed that simple adnexal cysts as large as 10 cm carry a risk of malignancy of less than 1%, regardless of the age of the patient. In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement,1 the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies for women with simple cysts:

Reproductive-aged women

- Cyst <3 cm: No action necessary; the cyst is a normal physiologic finding and should be referred to as a follicle.

- 3–5 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 5–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is highly likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Postmenopausal women

- <1 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 1–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Characteristics of hemorrhagic cysts

These cysts can be quite variable in appearance. Among their sonographic features:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, or fishnet) internal echoes, due to fibrin strands

- solid-appearing areas with concave margins

- on color Doppler, there may be circumferential peripheral flow (“ring of fire”) and no internal flow.

In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies1:

Premenopausal women

- ≤5 cm: No follow-up imaging unless the diagnosis is uncertain.

- >5 cm: Short-interval follow-up ultrasound (6–12 weeks).

Recently menopausal women

- Any size: Follow-up ultrasound in 6–12 weeks to ensure resolution.

Later postmenopausal women

- Any size: Consider surgical removal, as the cyst may be neoplastic.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Pelvic ultrasonography remains the preferred imaging method to evaluate most adnexal cysts, given its ability to accurately characterize their various aspects:

- Simple cysts are uniformly hypoechoic, with thin walls and no blood flow on color Doppler (FIGURE 1).

- Hemorrhagic cysts produce lacy/reticular echoes and clot with concave margins

(FIGURE 2). - Mature cystic teratomas produce hyperechoic lines and dots, sometimes known as “dermoid mesh,” acoustic shadowing, and a hyperechoic nodule (FIGURE 3).

- Endometriomas produce diffuse, low-level internal echoes and a “ground glass” appearance (FIGURE 4).

In the first of this 4-part series on the sonographic features of cystic adnexal pathology, we focus on simple and hemorrhagic cysts. In the following parts we will highlight:

- mature cystic teratomas and endometriomas (Part 2)

- hydrosalpinx and pelvic inclusion cysts (Part 3)

- cystadenoma and ovarian neoplasia (Part 4).

An earlier installment of this series entitled “Hemorrhagic ovarian cysts: one entity with many appearances” (May 2014) also focused on cystic pathology.

Figure 1: Simple cyst

A simple cyst in a 32-year-old patient. Figure 2: Hemorrhagic cyst

Note the lacy/reticular internal echoes and lack of internal blood flow on color Doppler. Figure 3: Cystic teratoma

This cyst exhibits the “dermoid mesh” and hyperechoic lines that correspond with hair. Figure 4: Endometrioma

Note diffuse low-level internal echoes (“ground glass”) and no “ring of fire” on color Doppler. |

Characteristics of simple cysts

A simple cyst typically is round or oval, anechoic, and has smooth, thin walls. It contains no solid component or septation (with rare exceptions), and no internal flow is visible on color Doppler imaging.

Levine and colleagues observed that simple adnexal cysts as large as 10 cm carry a risk of malignancy of less than 1%, regardless of the age of the patient. In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement,1 the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies for women with simple cysts:

Reproductive-aged women

- Cyst <3 cm: No action necessary; the cyst is a normal physiologic finding and should be referred to as a follicle.

- 3–5 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 5–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is highly likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Postmenopausal women

- <1 cm: No follow-up necessary; the cyst is almost certainly benign.

- 1–7 cm: Yearly imaging; the cyst is likely to be benign.

- >7 cm: Additional imaging is recommended.

Characteristics of hemorrhagic cysts

These cysts can be quite variable in appearance. Among their sonographic features:

- reticular (lacy, cobweb, or fishnet) internal echoes, due to fibrin strands

- solid-appearing areas with concave margins

- on color Doppler, there may be circumferential peripheral flow (“ring of fire”) and no internal flow.

In its 2010 Consensus Conference Statement, the Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound recommended the following management strategies1:

Premenopausal women

- ≤5 cm: No follow-up imaging unless the diagnosis is uncertain.

- >5 cm: Short-interval follow-up ultrasound (6–12 weeks).

Recently menopausal women

- Any size: Follow-up ultrasound in 6–12 weeks to ensure resolution.

Later postmenopausal women

- Any size: Consider surgical removal, as the cyst may be neoplastic.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

Reference

1. Levine D, Brown DL, Andreotti RF, et al. Management of asymptomatic ovarian and other adnexal cysts imaged at US: Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound Consensus Conference Statement. Radiology. 2010;256(3):943–954.

Dr. Andrew M. Kaunitz on prescribing systemic HT to older women

Recorded at the 2014 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Recorded at the 2014 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Recorded at the 2014 meeting of the North American Menopause Society

Focus on cervical biopsy

Are multiple lesion-directed biopsies better than one at detecting cervical cancer precursors?

Yes. In this observational study of 690 women referred to colposcopy for abnormal cervical screening results, the sensitivity of biopsy in the detection of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) increased from 60.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 54.8–66.6) for a single biopsy to 95.6% (95% CI, 91.3–99.2) for three biopsies.

Wentsensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy [published online ahead of print November 24, 2014]. J Clin Oncol. pii:JCO.2014.55.9948.

Recent updates of cervical cancer screening protocols have altered the way we screen women but have not changed colposcopic practices, which vary widely in the United States. Investigators funded by the National Cancer Institute studied 690 women (median age, 26 years; range, 18–67 years) who underwent as many as four directed biopsies of distinct acetowhite lesions. HSIL (which included cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] 2 and 3 and invasive cancer) represented the gold standard for the sensitivity of the cervical biopsies.

Colposcopists performed a median of one, three, and four biopsies in women with no observed lesions, acetowhite lesions only, and low- or high-grade colposcopic impressions, respectively. More than 95% of HSIL was found in women noted to have a colposcopic impression of at least low-grade disease.

Although multiple biopsies increased the diagnostic yield in all groups, the greatest increase in yield was observed in women with HSIL cytology, positivity for HPV 16, and a colposcopic impression suggesting HSIL. Similar trends were observed for each of the six colposcopists (all well trained and highly experienced), each of whom performed at least 60 colposcopies in the study population.

What this evidence means for practice

When HSIL is missed at colposcopy, the patient is subjected to delayed treatment and repeat assessment. Although multiple biopsies can increase patient discomfort and costs, these findings add to other published data underscoring their value. Instead of biopsying only the worst-appearing lesion, obtain at least two or three biopsies when distinct lesions, including acetowhite areas, are noted.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

How useful is random biopsy when no lesions are seen?

Useful. It identifies approximately 20% of otherwise undetected cases of CIN 2, CIN 3, or worse. The absolute risks of disease associated with the random biopsy were higher for women positive for HPV 16 or 18, according to this large post hoc analysis.

Huh WK, Sideri M, Stoler M, Zhang G, Feldman R, Behrens CM. Relevance of random biopsy at the transformation zone when colposcopy is negative. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):670–678.

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk HPV, clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation prompts the question: Is a random biopsy warranted?

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women—conducted to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009—nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus underwent colposcopy after a finding of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or higher-grade cytology results or high-risk HPV. Patients and colposcopists were blinded to the results. In women who had satisfactory colposcopy results but no visible lesions, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was obtained.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) who underwent random biopsy, the findings were normal, CIN 1, CIN 2, and CIN 3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN 2 or worse and CIN 3 or worse cases, respectively.

Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN 2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for practice

This post hoc analysis underscores the limitations of colposcopy, as have other reports. Just as the findings of Wentsensen and colleagues demonstrate that two or more lesion-directed biopsies increase the diagnostic yield over a single sample, this large study points out the substantial benefit of random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Are multiple lesion-directed biopsies better than one at detecting cervical cancer precursors?

Yes. In this observational study of 690 women referred to colposcopy for abnormal cervical screening results, the sensitivity of biopsy in the detection of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) increased from 60.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 54.8–66.6) for a single biopsy to 95.6% (95% CI, 91.3–99.2) for three biopsies.

Wentsensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy [published online ahead of print November 24, 2014]. J Clin Oncol. pii:JCO.2014.55.9948.

Recent updates of cervical cancer screening protocols have altered the way we screen women but have not changed colposcopic practices, which vary widely in the United States. Investigators funded by the National Cancer Institute studied 690 women (median age, 26 years; range, 18–67 years) who underwent as many as four directed biopsies of distinct acetowhite lesions. HSIL (which included cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] 2 and 3 and invasive cancer) represented the gold standard for the sensitivity of the cervical biopsies.

Colposcopists performed a median of one, three, and four biopsies in women with no observed lesions, acetowhite lesions only, and low- or high-grade colposcopic impressions, respectively. More than 95% of HSIL was found in women noted to have a colposcopic impression of at least low-grade disease.

Although multiple biopsies increased the diagnostic yield in all groups, the greatest increase in yield was observed in women with HSIL cytology, positivity for HPV 16, and a colposcopic impression suggesting HSIL. Similar trends were observed for each of the six colposcopists (all well trained and highly experienced), each of whom performed at least 60 colposcopies in the study population.

What this evidence means for practice

When HSIL is missed at colposcopy, the patient is subjected to delayed treatment and repeat assessment. Although multiple biopsies can increase patient discomfort and costs, these findings add to other published data underscoring their value. Instead of biopsying only the worst-appearing lesion, obtain at least two or three biopsies when distinct lesions, including acetowhite areas, are noted.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

How useful is random biopsy when no lesions are seen?

Useful. It identifies approximately 20% of otherwise undetected cases of CIN 2, CIN 3, or worse. The absolute risks of disease associated with the random biopsy were higher for women positive for HPV 16 or 18, according to this large post hoc analysis.

Huh WK, Sideri M, Stoler M, Zhang G, Feldman R, Behrens CM. Relevance of random biopsy at the transformation zone when colposcopy is negative. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):670–678.

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk HPV, clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation prompts the question: Is a random biopsy warranted?

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women—conducted to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009—nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus underwent colposcopy after a finding of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or higher-grade cytology results or high-risk HPV. Patients and colposcopists were blinded to the results. In women who had satisfactory colposcopy results but no visible lesions, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was obtained.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) who underwent random biopsy, the findings were normal, CIN 1, CIN 2, and CIN 3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN 2 or worse and CIN 3 or worse cases, respectively.

Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN 2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for practice

This post hoc analysis underscores the limitations of colposcopy, as have other reports. Just as the findings of Wentsensen and colleagues demonstrate that two or more lesion-directed biopsies increase the diagnostic yield over a single sample, this large study points out the substantial benefit of random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Are multiple lesion-directed biopsies better than one at detecting cervical cancer precursors?

Yes. In this observational study of 690 women referred to colposcopy for abnormal cervical screening results, the sensitivity of biopsy in the detection of high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) increased from 60.6% (95% confidence interval [CI], 54.8–66.6) for a single biopsy to 95.6% (95% CI, 91.3–99.2) for three biopsies.

Wentsensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy [published online ahead of print November 24, 2014]. J Clin Oncol. pii:JCO.2014.55.9948.

Recent updates of cervical cancer screening protocols have altered the way we screen women but have not changed colposcopic practices, which vary widely in the United States. Investigators funded by the National Cancer Institute studied 690 women (median age, 26 years; range, 18–67 years) who underwent as many as four directed biopsies of distinct acetowhite lesions. HSIL (which included cervical intraepithelial neoplasia [CIN] 2 and 3 and invasive cancer) represented the gold standard for the sensitivity of the cervical biopsies.

Colposcopists performed a median of one, three, and four biopsies in women with no observed lesions, acetowhite lesions only, and low- or high-grade colposcopic impressions, respectively. More than 95% of HSIL was found in women noted to have a colposcopic impression of at least low-grade disease.

Although multiple biopsies increased the diagnostic yield in all groups, the greatest increase in yield was observed in women with HSIL cytology, positivity for HPV 16, and a colposcopic impression suggesting HSIL. Similar trends were observed for each of the six colposcopists (all well trained and highly experienced), each of whom performed at least 60 colposcopies in the study population.

What this evidence means for practice

When HSIL is missed at colposcopy, the patient is subjected to delayed treatment and repeat assessment. Although multiple biopsies can increase patient discomfort and costs, these findings add to other published data underscoring their value. Instead of biopsying only the worst-appearing lesion, obtain at least two or three biopsies when distinct lesions, including acetowhite areas, are noted.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

How useful is random biopsy when no lesions are seen?

Useful. It identifies approximately 20% of otherwise undetected cases of CIN 2, CIN 3, or worse. The absolute risks of disease associated with the random biopsy were higher for women positive for HPV 16 or 18, according to this large post hoc analysis.

Huh WK, Sideri M, Stoler M, Zhang G, Feldman R, Behrens CM. Relevance of random biopsy at the transformation zone when colposcopy is negative. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):670–678.

When performing colposcopy for abnormal cytology results or high-risk HPV, clinicians often are faced with an absence of visible lesions. This situation prompts the question: Is a random biopsy warranted?

Details of the study

In a multicenter US study of more than 47,000 women—conducted to assess HPV diagnostics between May 2008 and August 2009—nonpregnant women aged 25 or older with an intact uterus underwent colposcopy after a finding of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance or higher-grade cytology results or high-risk HPV. Patients and colposcopists were blinded to the results. In women who had satisfactory colposcopy results but no visible lesions, one random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction was obtained.

Among 2,796 women (mean age, 39.5 years) who underwent random biopsy, the findings were normal, CIN 1, CIN 2, and CIN 3 in 90.0%, 5.7%, 1.3%, and 1.4%, respectively. Among all participants aged 25 and older, random biopsies accounted for 20.9% and 18.9% of the CIN 2 or worse and CIN 3 or worse cases, respectively.

Among women positive for HPV 16 or 18, the likelihood of the random biopsy detecting CIN 2 or worse was 24.7% and 8.6% for those with abnormal cytology or normal cytology, respectively.

What this evidence means for practice

This post hoc analysis underscores the limitations of colposcopy, as have other reports. Just as the findings of Wentsensen and colleagues demonstrate that two or more lesion-directed biopsies increase the diagnostic yield over a single sample, this large study points out the substantial benefit of random biopsy of the squamocolumnar junction when no colposcopic lesions are identified.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

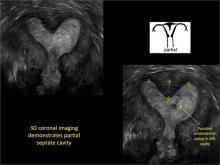

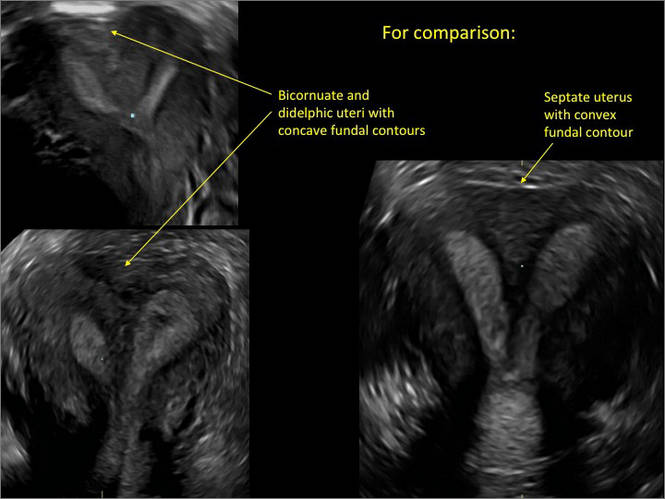

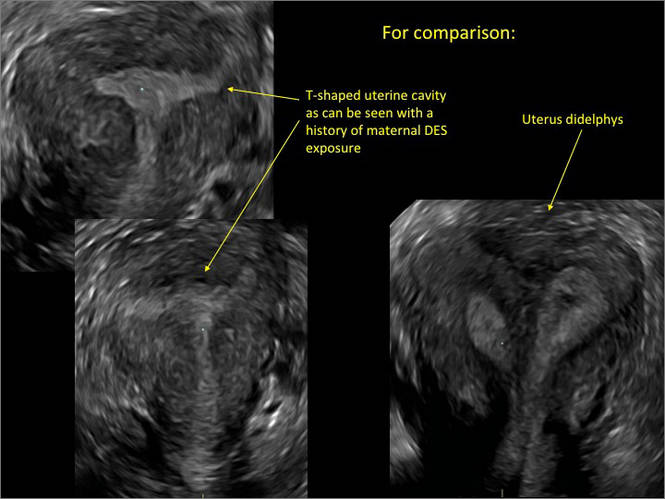

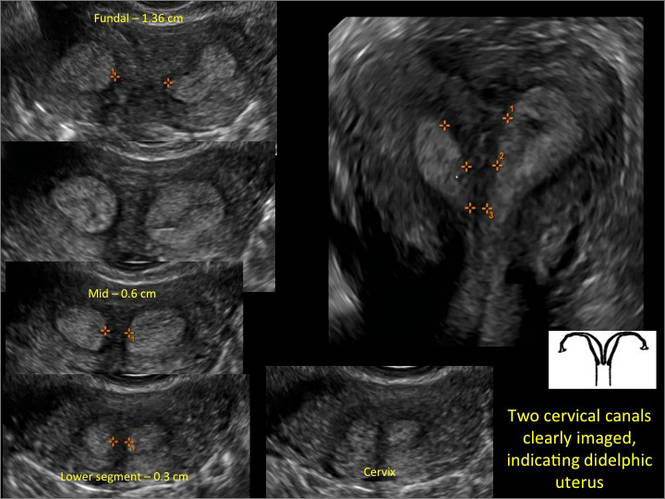

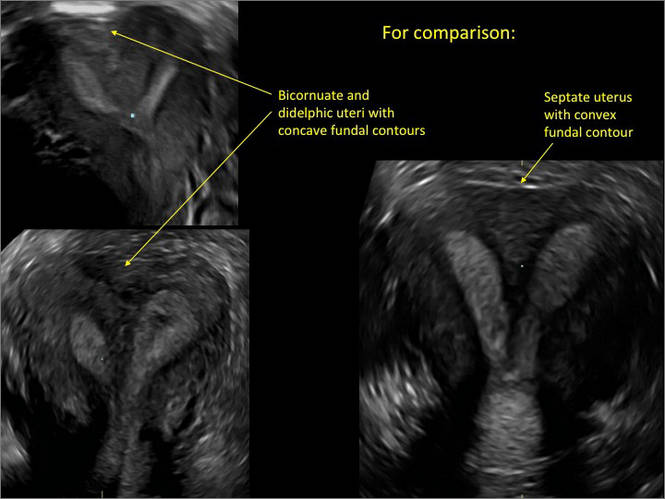

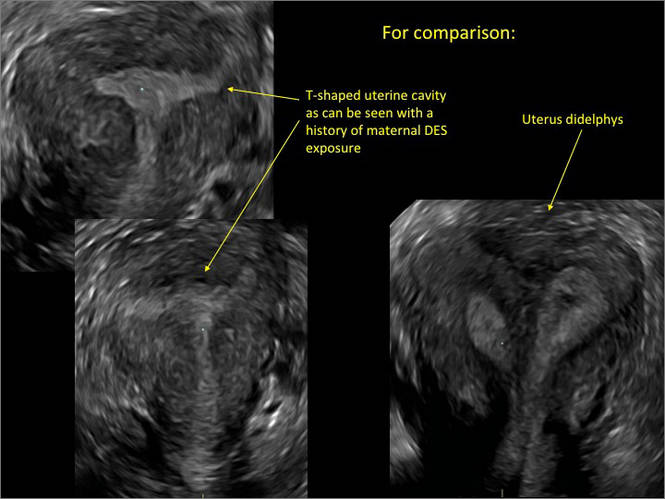

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 2

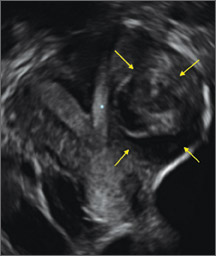

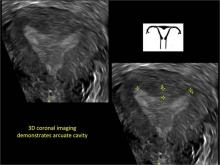

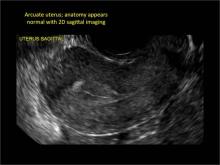

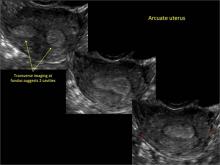

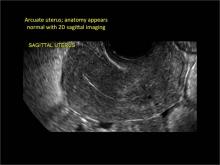

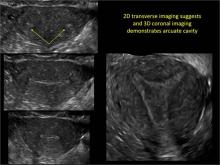

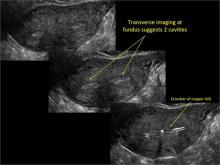

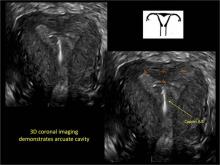

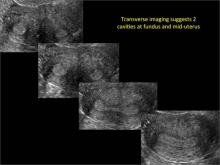

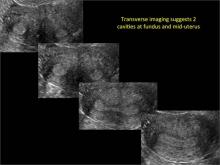

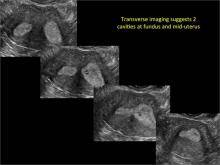

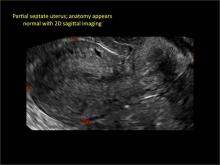

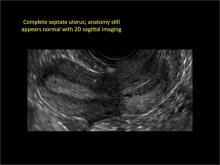

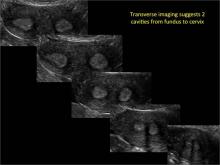

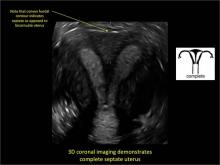

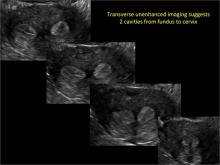

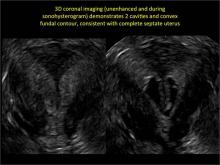

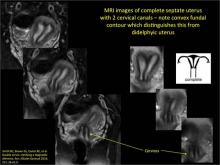

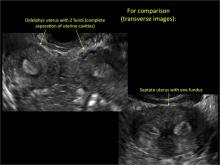

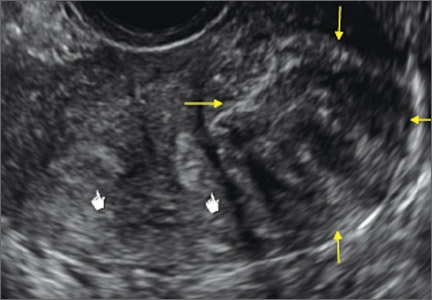

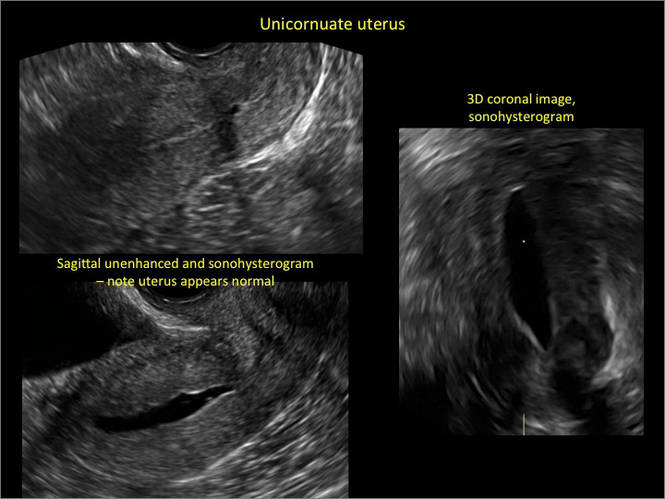

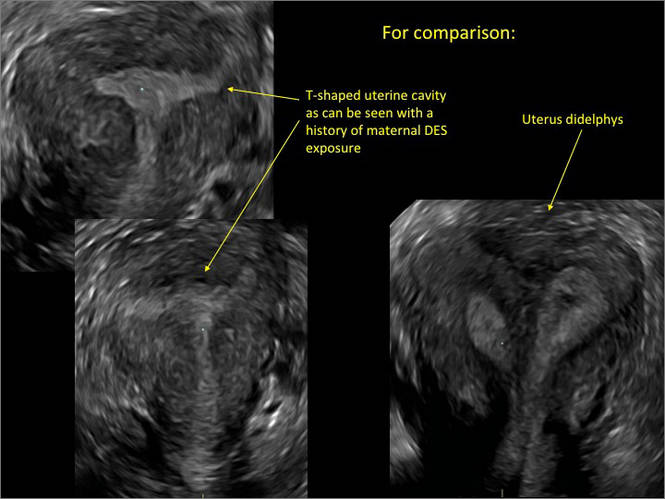

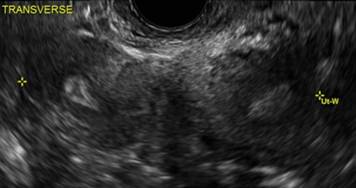

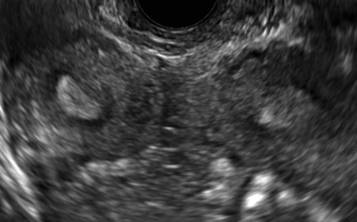

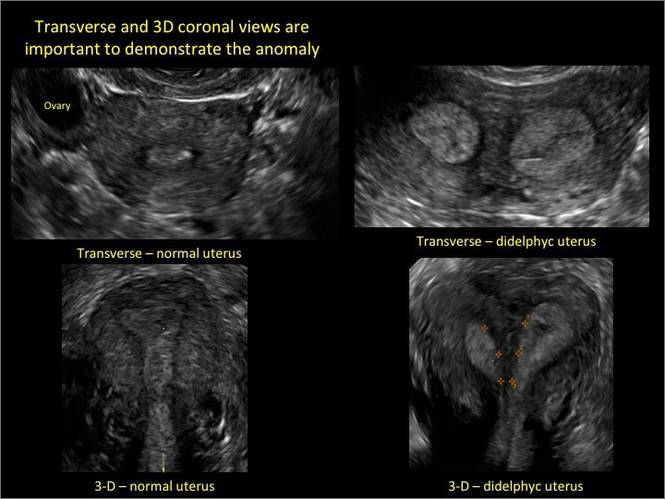

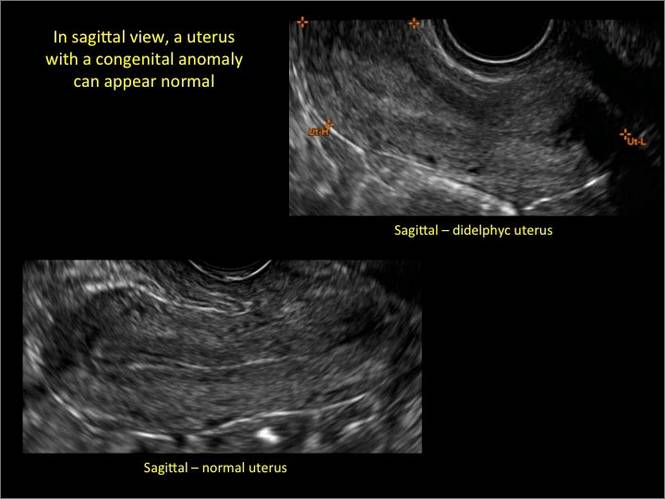

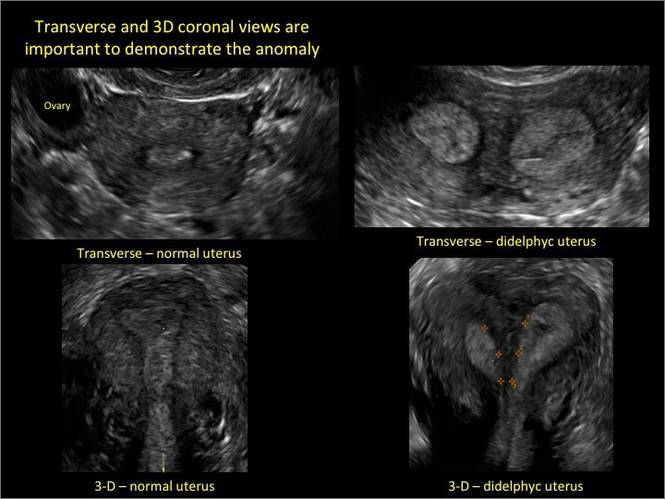

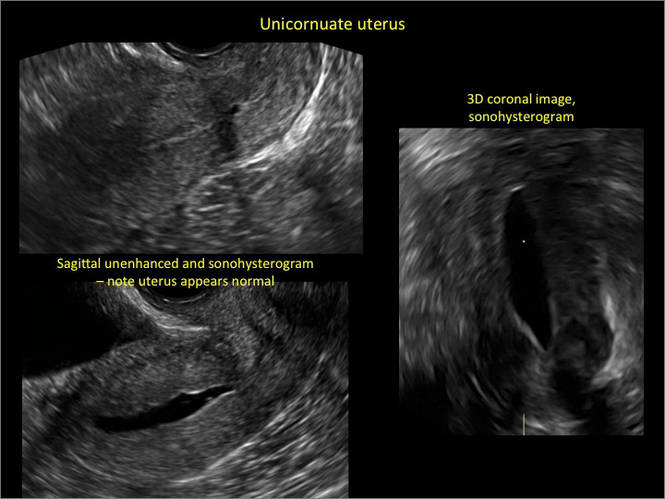

As detailed in Part 1 of this installment on uterine anomalies, a uterus that has developed abnormally can appear to be normal on 2D sonography and on unenhanced sonohysterography (Figure). Without the application of 3D coronal ultrasonography, accurate identification of the fundal contour, and ultimately the type and classification of the uterine anomaly, is not possible.1-3 Fortunately, the lowered cost (compared with magnetic resonance imaging) and the noninvasive nature of this more detailed imaging modality makes its use convenient to both the physician and the patient.

In part 1 of this 2-part installment of our imaging series, we discussed the frequency with which uterine anomalies occur and their types and classifications, as well as offered an imaging library showing the normal endometrial cavity, arcuate uterus, incomplete (partial) uterine septum, and complete uterine septum. Here, we provide two cases demonstrating 3D sonography of the unicornuate, bicornuate, didelphic, and DES-exposed uterus.

A. | B.  |

C.  | D.  |

E.  | F.  |

G.

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. Sagittal views of a normal uterus (A) and didelphic uterus (B) and sonohysterogram of a unicornuate uterus (C). Transverse views of a normal (D) and didelphic uterus (E). 3D coronal views of a normal (F) and didelphic uterus (G).

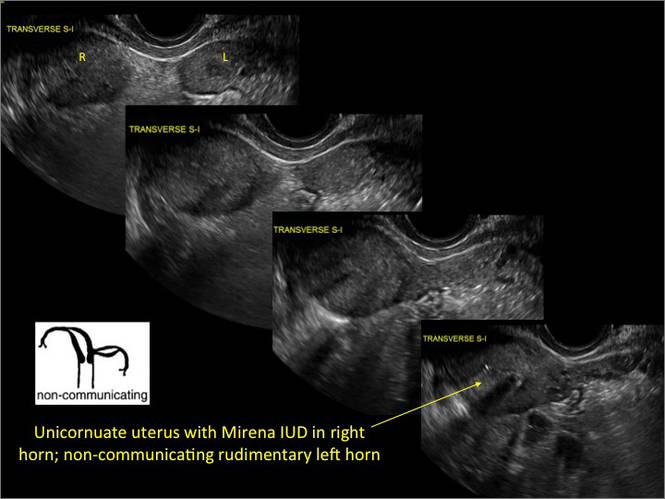

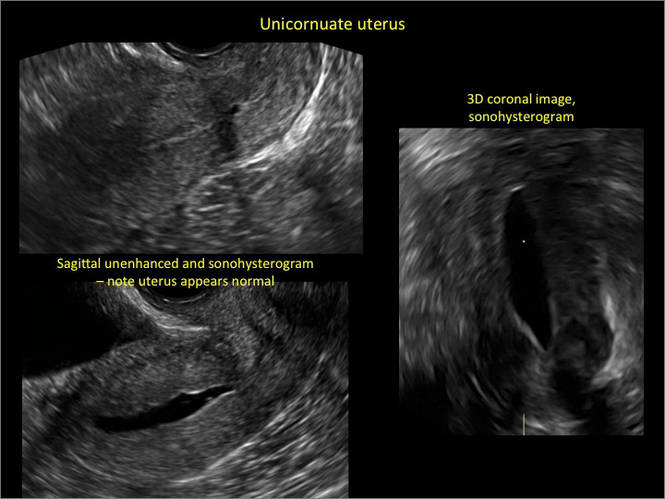

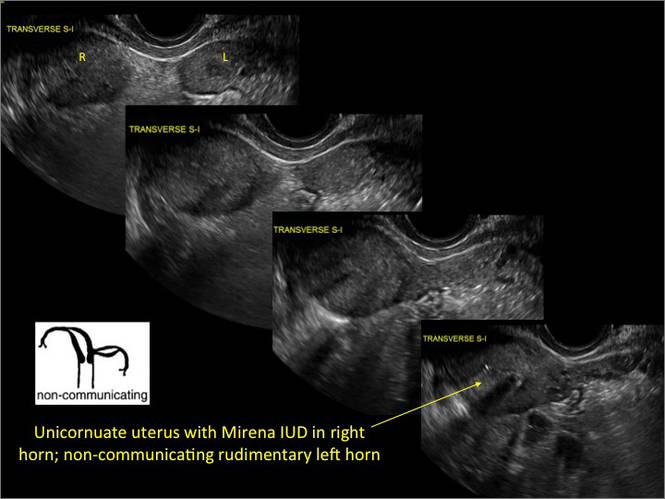

Case 1: Unicornuate uterus

Transverse view of Mirena IUD in right horn and noncommunicating rudimentary left horn.

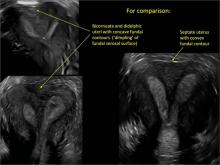

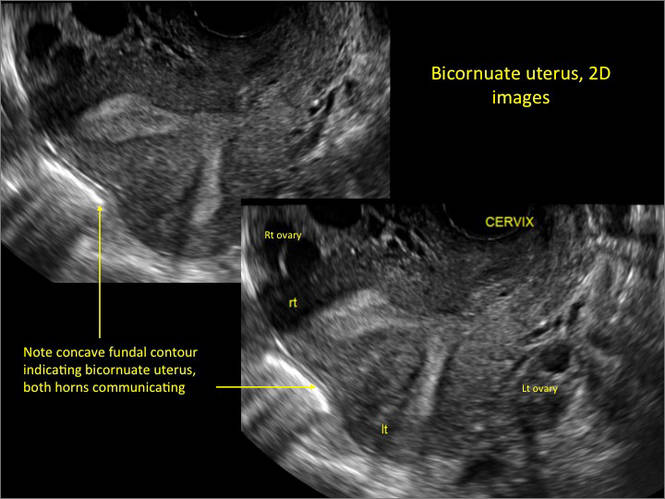

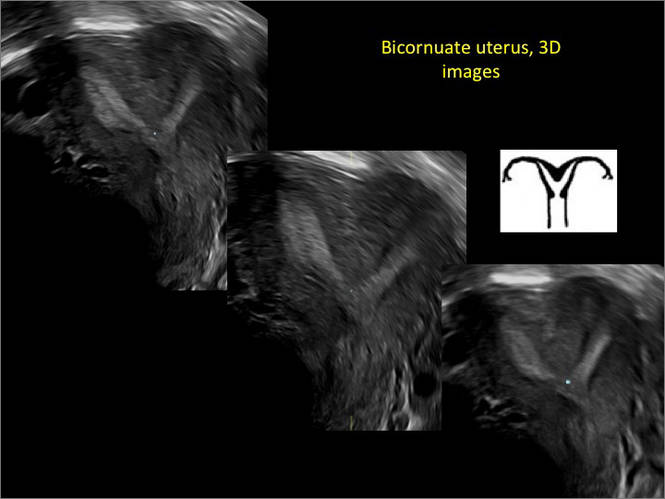

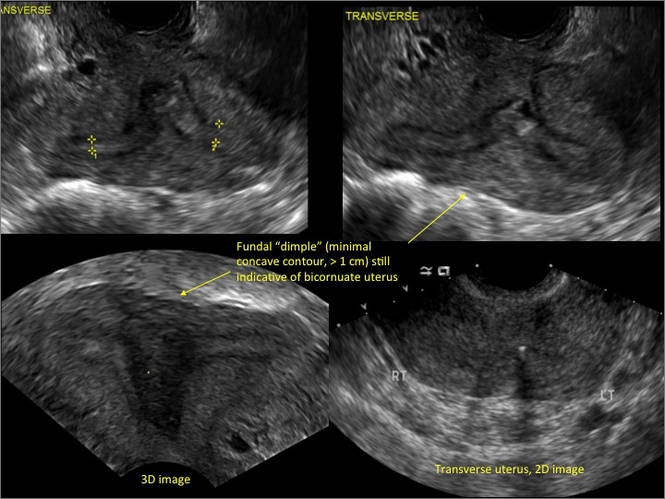

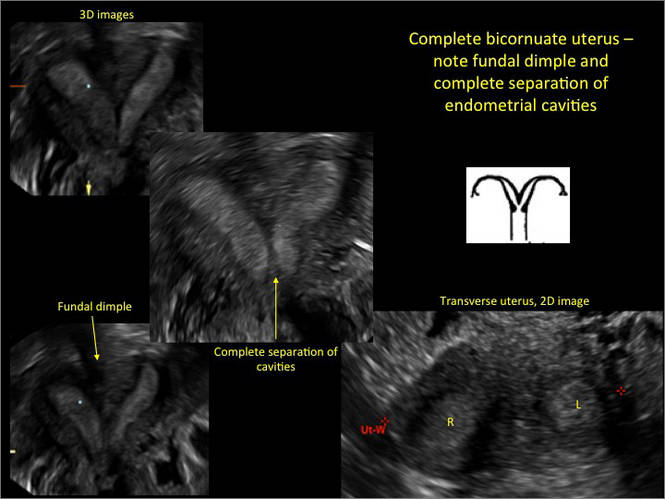

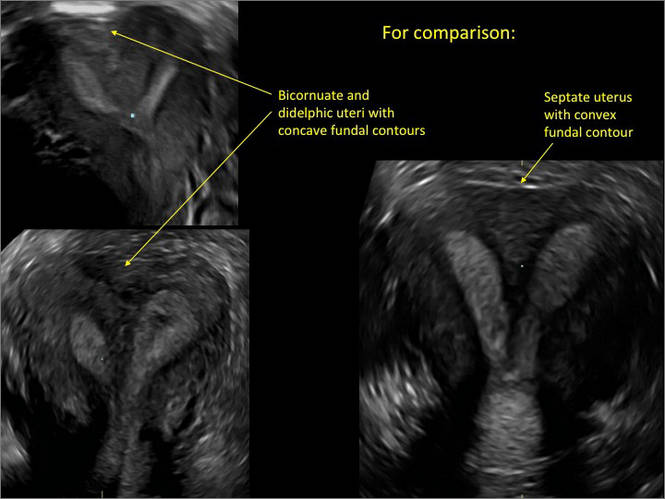

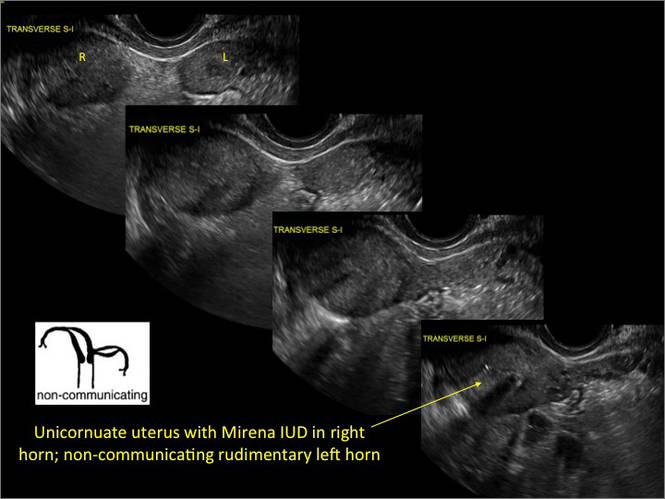

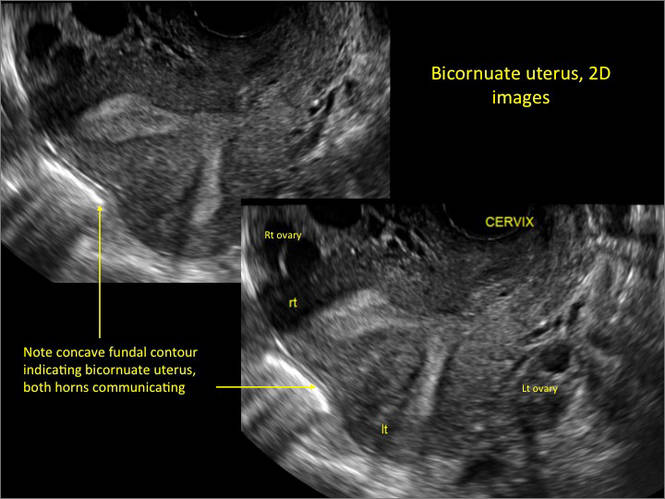

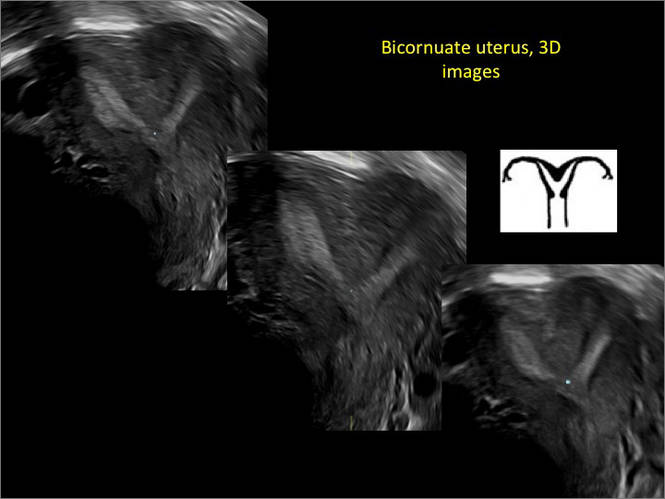

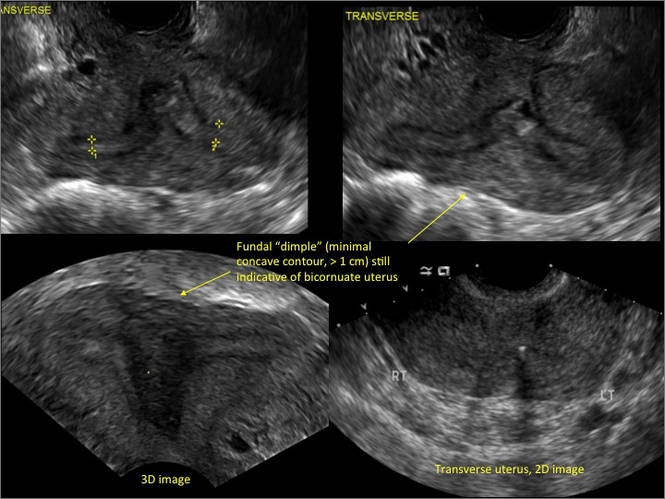

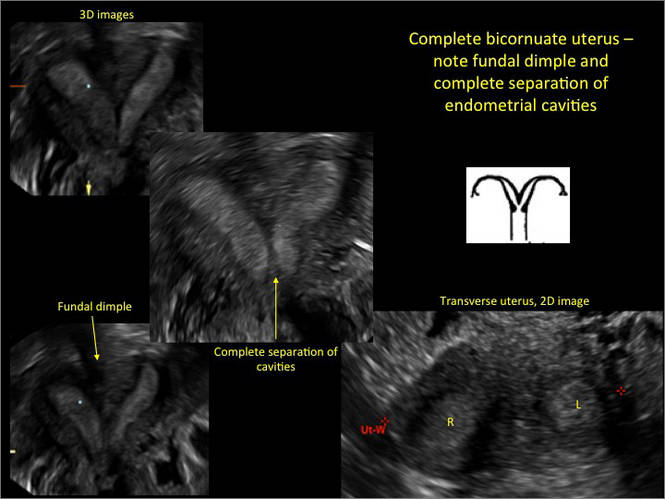

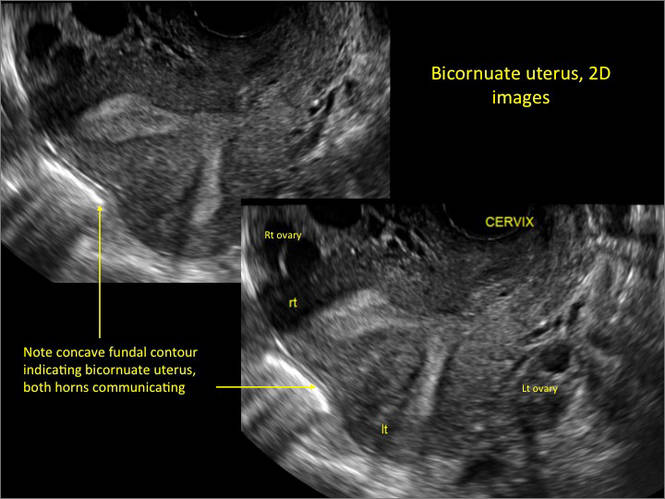

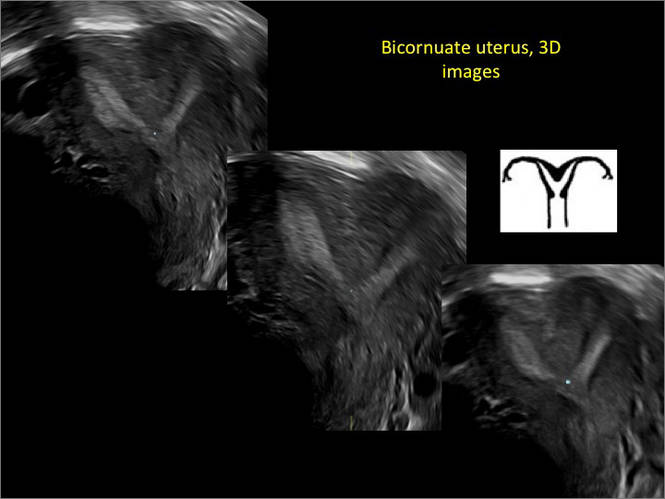

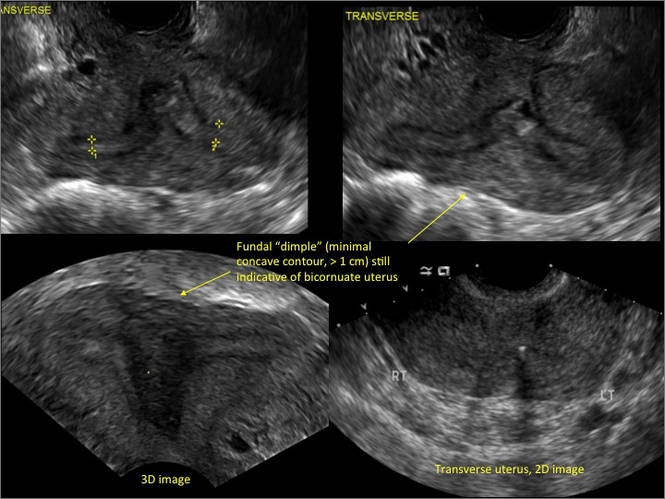

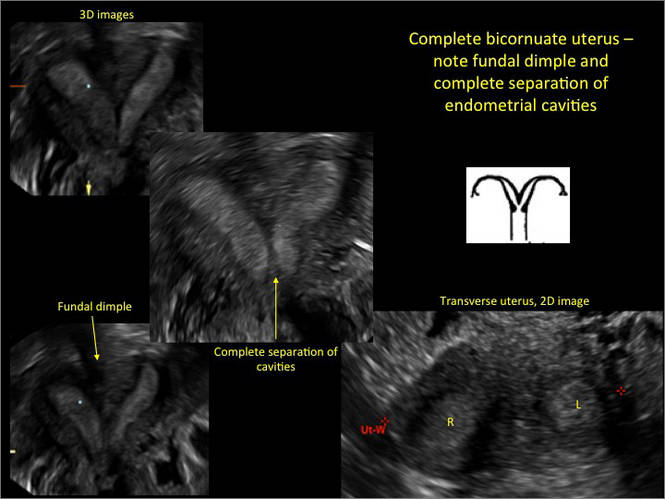

Case 2: Bicornuate uterus, with concave contour

A patient reporting pelvic pain is examined by 2D sonography, which reveals a bicornuate uterus (A). Note the concave fundal contour (arrow), indicating bicornuate uterus, both horns communicating. 3D imaging (B) revealing fundal “dimple” (concave contour, >1 cm), which is indicative of bicornuate uterus. Complete separation of cavities (C).

A.

B.

C.

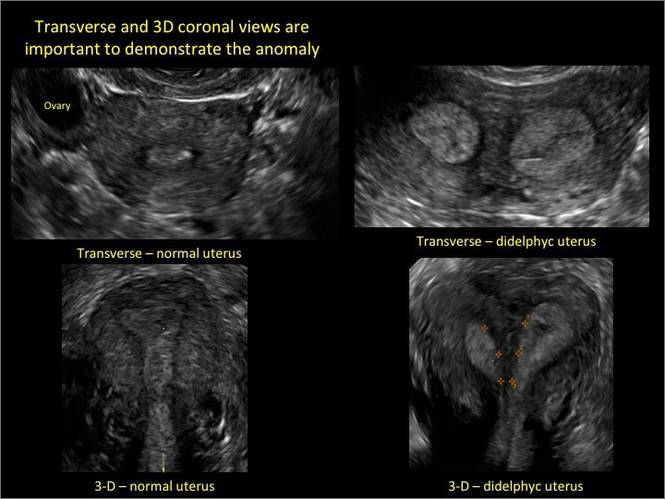

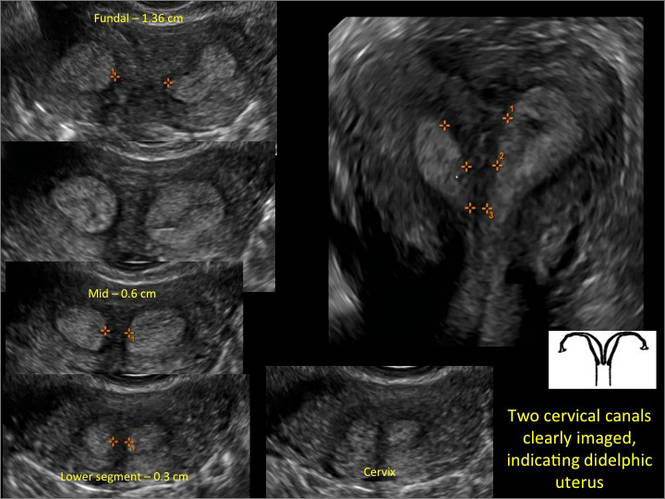

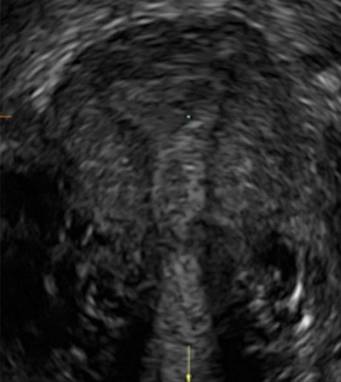

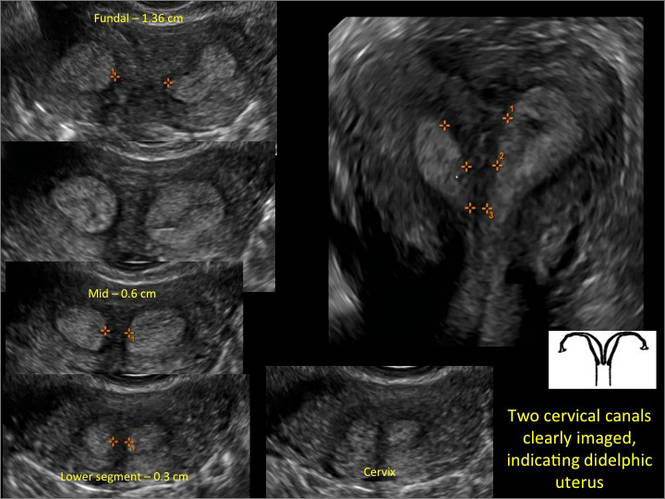

Case 3: Didelphic uterus

A patient presenting with primary infertility is found to have a didelphic uterus on 2D and 3D imaging. Note complete separation of uterine cavities on transverse, 2D views (A and B). The left horn sagittal, 2D view shows a normal appearing uterus (C). 3D imaging (D).

A.

B.

C.

D.

Additional images

- Deutch T, Bocca S, Oehninger S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies [abstract]. Fertil Steril 2006; 86(suppl):S308.15.

- Wu MH, Hsu CC, Huang KE. Detection of congenital müllerian duct anomalies using three-dimensional ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound 1997; 25:487–492.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of müllerian duct anomalies: a review of the literature. J Ultrasound Med 2008; 27:413–423.

As detailed in Part 1 of this installment on uterine anomalies, a uterus that has developed abnormally can appear to be normal on 2D sonography and on unenhanced sonohysterography (Figure). Without the application of 3D coronal ultrasonography, accurate identification of the fundal contour, and ultimately the type and classification of the uterine anomaly, is not possible.1-3 Fortunately, the lowered cost (compared with magnetic resonance imaging) and the noninvasive nature of this more detailed imaging modality makes its use convenient to both the physician and the patient.

In part 1 of this 2-part installment of our imaging series, we discussed the frequency with which uterine anomalies occur and their types and classifications, as well as offered an imaging library showing the normal endometrial cavity, arcuate uterus, incomplete (partial) uterine septum, and complete uterine septum. Here, we provide two cases demonstrating 3D sonography of the unicornuate, bicornuate, didelphic, and DES-exposed uterus.

A. | B.  |

C.  | D.  |

E.  | F.  |

G.

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. Sagittal views of a normal uterus (A) and didelphic uterus (B) and sonohysterogram of a unicornuate uterus (C). Transverse views of a normal (D) and didelphic uterus (E). 3D coronal views of a normal (F) and didelphic uterus (G).

Case 1: Unicornuate uterus

Transverse view of Mirena IUD in right horn and noncommunicating rudimentary left horn.

Case 2: Bicornuate uterus, with concave contour

A patient reporting pelvic pain is examined by 2D sonography, which reveals a bicornuate uterus (A). Note the concave fundal contour (arrow), indicating bicornuate uterus, both horns communicating. 3D imaging (B) revealing fundal “dimple” (concave contour, >1 cm), which is indicative of bicornuate uterus. Complete separation of cavities (C).

A.

B.

C.

Case 3: Didelphic uterus

A patient presenting with primary infertility is found to have a didelphic uterus on 2D and 3D imaging. Note complete separation of uterine cavities on transverse, 2D views (A and B). The left horn sagittal, 2D view shows a normal appearing uterus (C). 3D imaging (D).

A.

B.

C.

D.

Additional images

As detailed in Part 1 of this installment on uterine anomalies, a uterus that has developed abnormally can appear to be normal on 2D sonography and on unenhanced sonohysterography (Figure). Without the application of 3D coronal ultrasonography, accurate identification of the fundal contour, and ultimately the type and classification of the uterine anomaly, is not possible.1-3 Fortunately, the lowered cost (compared with magnetic resonance imaging) and the noninvasive nature of this more detailed imaging modality makes its use convenient to both the physician and the patient.

In part 1 of this 2-part installment of our imaging series, we discussed the frequency with which uterine anomalies occur and their types and classifications, as well as offered an imaging library showing the normal endometrial cavity, arcuate uterus, incomplete (partial) uterine septum, and complete uterine septum. Here, we provide two cases demonstrating 3D sonography of the unicornuate, bicornuate, didelphic, and DES-exposed uterus.

A. | B.  |

C.  | D.  |

E.  | F.  |

G.

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. Sagittal views of a normal uterus (A) and didelphic uterus (B) and sonohysterogram of a unicornuate uterus (C). Transverse views of a normal (D) and didelphic uterus (E). 3D coronal views of a normal (F) and didelphic uterus (G).

Case 1: Unicornuate uterus

Transverse view of Mirena IUD in right horn and noncommunicating rudimentary left horn.

Case 2: Bicornuate uterus, with concave contour

A patient reporting pelvic pain is examined by 2D sonography, which reveals a bicornuate uterus (A). Note the concave fundal contour (arrow), indicating bicornuate uterus, both horns communicating. 3D imaging (B) revealing fundal “dimple” (concave contour, >1 cm), which is indicative of bicornuate uterus. Complete separation of cavities (C).

A.

B.

C.

Case 3: Didelphic uterus

A patient presenting with primary infertility is found to have a didelphic uterus on 2D and 3D imaging. Note complete separation of uterine cavities on transverse, 2D views (A and B). The left horn sagittal, 2D view shows a normal appearing uterus (C). 3D imaging (D).

A.

B.

C.

D.

Additional images

- Deutch T, Bocca S, Oehninger S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies [abstract]. Fertil Steril 2006; 86(suppl):S308.15.

- Wu MH, Hsu CC, Huang KE. Detection of congenital müllerian duct anomalies using three-dimensional ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound 1997; 25:487–492.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of müllerian duct anomalies: a review of the literature. J Ultrasound Med 2008; 27:413–423.

- Deutch T, Bocca S, Oehninger S, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging versus three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies [abstract]. Fertil Steril 2006; 86(suppl):S308.15.

- Wu MH, Hsu CC, Huang KE. Detection of congenital müllerian duct anomalies using three-dimensional ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound 1997; 25:487–492.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of müllerian duct anomalies: a review of the literature. J Ultrasound Med 2008; 27:413–423.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of discussing the various uterine malformations as well as characterizing their appearance on 3D transvaginal ultrasound.

Unfortunately, many women are still subjected to the cost, inconvenience, and time involvement of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in cases of suspected uterine malformations. The exquisite visualization of 3D transvaginal ultrasound, so nicely depicted in this installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, allow the observer to see the endometrial contours in the same plane as the serosal surface. This view is not available in traditional 2D ultrasound images. Thus, it is akin to doing laparoscopy and hysteroscopy simultaneously in order to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Although not mandatory, when such 3D ultrasound is performed late in the cycle, the thickened endometrium acts as a nice sonic backdrop to better delineate these structures. Alternatively, 3D saline infusion sonohysterography can be performed.

As more and more ultrasound equipment becomes available with 3D capability as a standard feature, clinicians who do perform ultrasonography will find that obtaining this “z-plane” is relatively simple and extremely informative, and can and should be done in cases of suspected uterine malformations in lieu of ordering MRI.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

Michelle L. Stalnaker Ozcan, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine malformations make up a diverse group of congenital anomalies that can result from various alterations in the normal development of the Müllerian ducts, including underdevelopment of one or both Müllerian ducts, disorders in Müllerian duct fusion, and alterations in septum reabsorption. How common are such anomalies, how are they classified, and what is the best approach for optimal visualization? Here, we explore these questions and offer an atlas of diagnostic images as an ongoing reference for your practice. Many of the images we offer will be found only online at obgmanagement.com.

How common are congenital uterine anomalies?

The reported prevalence of uterine malformations varies among publications due to heterogeneous population samples, differences in diagnostic techniques, and variations in nomenclature. In general, they are estimated to occur in 0.4% (0.1% to 3.0%) of the population at large, 4% of infertile women, and between 3% and 38% of women with repetitive spontaneous miscarriage.1

Classical classification

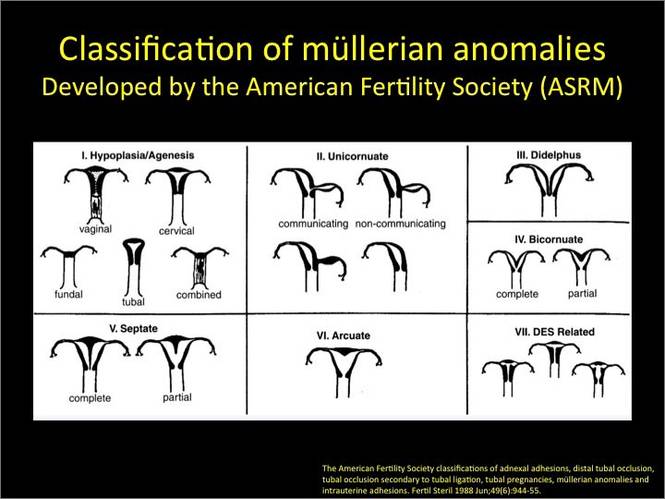

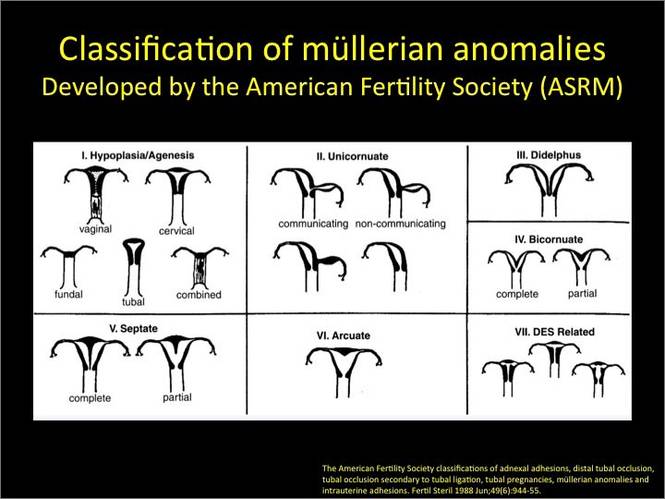

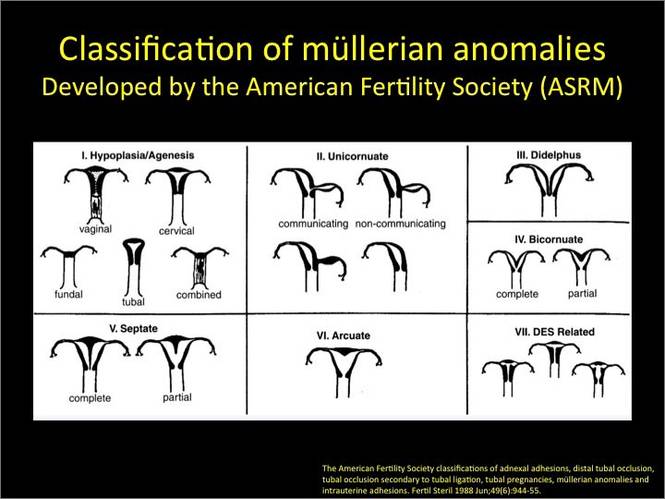

A classification of the Müllerian anomalies was introduced in 1980 and, with few modifications, was adopted by the American Fertility Society (currently, ASRM). The Society identified seven basic groups according to Müllerian development and their relationship to fertility: agenesis and hypoplasias, unicornuate uteri (unilateral hypoplasia), didelphys uteri (complete nonfusion), bicornuate uteri (incomplete fusion), septate uteri (nonreabsorption of septum), arcuate uteri (almost complete reabsorption of septum), and anomalies related to fetal DES exposure.2

Anomalies also can be categorized in terms of progression along the developmental continuum, taking into account that many cases result from partial failure of fusion and reabsorption: agenesis (Types I and II), lack of fusion (Types III and IV), lack of reabsorption(Types V and VI), and lack of posterior development (Type VII) (FIGURE 1).3

| FIGURE 1. Classification of müllerian anomalies |

|---|

|

| Source: The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988. 49(6):944-955. |

3D ultrasonography offers accurate, cost-efficient diagnosis

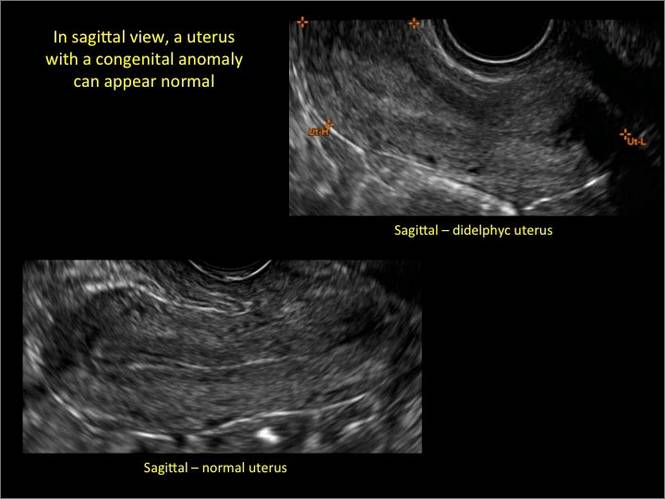

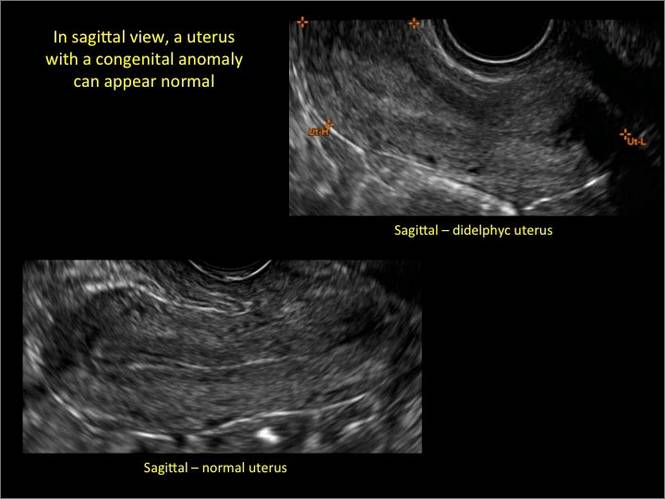

Using only 2D imaging, neither an unenhanced sonogram nor a sonohysterogram can provide definitive information regarding the possibility of a uterine anomaly. The fundal contour cannot be evaluated with 2D imaging; likewise, details regarding the configuration of the uterine cavity (or cavities) may not be appreciated with the use of 2D imaging (FIGURE 2).

Figure 2: Normal appearance, but abnormal uteri

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. 2D sagittal views of a normal uterus (top), a didelphic uterus (middle), and a sonohysterogram of a septate uterus (bottom). |

To fully evaluate the uterine fundal contour and determine the type of uterine anomaly, it previously was necessary to obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or perform laparoscopy. Today, however, 3D coronal ultrasonography (US) can allow for accurate evaluation of fundal contour and diagnosis of uterine anomalies with lower cost and greater patient convenience. Several studies have confirmed the high accuracy of 3D US compared with MRI and surgical findings in the diagnosis of uterine anomalies (with 3D US showing 98% to 100% sensitivity and specificity).4-6

Case: Partial septate uterus

|

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Bermejo C, Martinez Ten P, Cantarero R, et al. Three-dimensional ultrasound in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies and concordance with magnetic resonance imaging. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2010;35(5):593–601.

- The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(6):944–955.

- Acien P, Acien M. Updated classification of malformations. Hum Reprod. 2010;25(suppl 1):i81–i82.

- Deutch T, Bocca S, Oehninger S, Stadtmauer L, Abuhamad AZ. Magnetic resonance imaging versus three-dimensional transvaginal ultrasound for the diagnosis of Müllerian anomalies [abstract P-465]. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(suppl):S308.

- Wu MH, Hsu CC, Huang KE. Detection of congenital Müllerian duct anomalies using three-dimensional ultrasound. J Clin Ultrasound. 1997;25(9):487–492.

- Deutch TD, Abuhamad AZ. The role of 3-dimensional ultrasonography and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of Müllerian duct anomalies. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27(3):413–423.

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of discussing the various uterine malformations as well as characterizing their appearance on 3D transvaginal ultrasound.

Unfortunately, many women are still subjected to the cost, inconvenience, and time involvement of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in cases of suspected uterine malformations. The exquisite visualization of 3D transvaginal ultrasound, so nicely depicted in this installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, allow the observer to see the endometrial contours in the same plane as the serosal surface. This view is not available in traditional 2D ultrasound images. Thus, it is akin to doing laparoscopy and hysteroscopy simultaneously in order to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Although not mandatory, when such 3D ultrasound is performed late in the cycle, the thickened endometrium acts as a nice sonic backdrop to better delineate these structures. Alternatively, 3D saline infusion sonohysterography can be performed.

As more and more ultrasound equipment becomes available with 3D capability as a standard feature, clinicians who do perform ultrasonography will find that obtaining this “z-plane” is relatively simple and extremely informative, and can and should be done in cases of suspected uterine malformations in lieu of ordering MRI.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

Michelle L. Stalnaker Ozcan, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine malformations make up a diverse group of congenital anomalies that can result from various alterations in the normal development of the Müllerian ducts, including underdevelopment of one or both Müllerian ducts, disorders in Müllerian duct fusion, and alterations in septum reabsorption. How common are such anomalies, how are they classified, and what is the best approach for optimal visualization? Here, we explore these questions and offer an atlas of diagnostic images as an ongoing reference for your practice. Many of the images we offer will be found only online at obgmanagement.com.

How common are congenital uterine anomalies?

The reported prevalence of uterine malformations varies among publications due to heterogeneous population samples, differences in diagnostic techniques, and variations in nomenclature. In general, they are estimated to occur in 0.4% (0.1% to 3.0%) of the population at large, 4% of infertile women, and between 3% and 38% of women with repetitive spontaneous miscarriage.1

Classical classification

A classification of the Müllerian anomalies was introduced in 1980 and, with few modifications, was adopted by the American Fertility Society (currently, ASRM). The Society identified seven basic groups according to Müllerian development and their relationship to fertility: agenesis and hypoplasias, unicornuate uteri (unilateral hypoplasia), didelphys uteri (complete nonfusion), bicornuate uteri (incomplete fusion), septate uteri (nonreabsorption of septum), arcuate uteri (almost complete reabsorption of septum), and anomalies related to fetal DES exposure.2

Anomalies also can be categorized in terms of progression along the developmental continuum, taking into account that many cases result from partial failure of fusion and reabsorption: agenesis (Types I and II), lack of fusion (Types III and IV), lack of reabsorption(Types V and VI), and lack of posterior development (Type VII) (FIGURE 1).3

| FIGURE 1. Classification of müllerian anomalies |

|---|

|

| Source: The American Fertility Society classifications of adnexal adhesions, distal tubal occlusion, tubal occlusion secondary to tubal ligation, tubal pregnancies, müllerian anomalies and intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 1988. 49(6):944-955. |

3D ultrasonography offers accurate, cost-efficient diagnosis

Using only 2D imaging, neither an unenhanced sonogram nor a sonohysterogram can provide definitive information regarding the possibility of a uterine anomaly. The fundal contour cannot be evaluated with 2D imaging; likewise, details regarding the configuration of the uterine cavity (or cavities) may not be appreciated with the use of 2D imaging (FIGURE 2).

Figure 2: Normal appearance, but abnormal uteri

In sagittal view, a uterus with a congenital anomaly can appear normal. 2D sagittal views of a normal uterus (top), a didelphic uterus (middle), and a sonohysterogram of a septate uterus (bottom). |

To fully evaluate the uterine fundal contour and determine the type of uterine anomaly, it previously was necessary to obtain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or perform laparoscopy. Today, however, 3D coronal ultrasonography (US) can allow for accurate evaluation of fundal contour and diagnosis of uterine anomalies with lower cost and greater patient convenience. Several studies have confirmed the high accuracy of 3D US compared with MRI and surgical findings in the diagnosis of uterine anomalies (with 3D US showing 98% to 100% sensitivity and specificity).4-6

Case: Partial septate uterus

|

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

INTRODUCTION

Steven R. Goldstein, MD, CCD, NCMP

Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, New York University School of Medicine; Director, Gynecologic Ultrasound; and Co-Director, Bone Densitometry, New York University Medical Center, New York

In this month’s Images in GYN Ultrasound, Drs. Stalnaker and Kaunitz have done an excellent job of discussing the various uterine malformations as well as characterizing their appearance on 3D transvaginal ultrasound.

Unfortunately, many women are still subjected to the cost, inconvenience, and time involvement of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in cases of suspected uterine malformations. The exquisite visualization of 3D transvaginal ultrasound, so nicely depicted in this installment of Images in GYN Ultrasound, allow the observer to see the endometrial contours in the same plane as the serosal surface. This view is not available in traditional 2D ultrasound images. Thus, it is akin to doing laparoscopy and hysteroscopy simultaneously in order to arrive at the proper diagnosis. Although not mandatory, when such 3D ultrasound is performed late in the cycle, the thickened endometrium acts as a nice sonic backdrop to better delineate these structures. Alternatively, 3D saline infusion sonohysterography can be performed.

As more and more ultrasound equipment becomes available with 3D capability as a standard feature, clinicians who do perform ultrasonography will find that obtaining this “z-plane” is relatively simple and extremely informative, and can and should be done in cases of suspected uterine malformations in lieu of ordering MRI.

Congenital uterine anomalies: A resource of diagnostic images, Part 1

Michelle L. Stalnaker Ozcan, MD

Assistant Professor and Associate Program Director, Obstetrics and Gynecology Residency, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville

Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

University of Florida Research Foundation Professor and Associate Chairman, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University of Florida College of Medicine–Jacksonville. Dr. Kaunitz is a member of the OBG Management Board of Editors.

Uterine malformations make up a diverse group of congenital anomalies that can result from various alterations in the normal development of the Müllerian ducts, including underdevelopment of one or both Müllerian ducts, disorders in Müllerian duct fusion, and alterations in septum reabsorption. How common are such anomalies, how are they classified, and what is the best approach for optimal visualization? Here, we explore these questions and offer an atlas of diagnostic images as an ongoing reference for your practice. Many of the images we offer will be found only online at obgmanagement.com.

How common are congenital uterine anomalies?

The reported prevalence of uterine malformations varies among publications due to heterogeneous population samples, differences in diagnostic techniques, and variations in nomenclature. In general, they are estimated to occur in 0.4% (0.1% to 3.0%) of the population at large, 4% of infertile women, and between 3% and 38% of women with repetitive spontaneous miscarriage.1

Classical classification