User login

Two cases of genital pruritus: What is the one diagnosis?

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory skin disease that primarily affects the genital and perianal skin of postmenopausal women. The mean age of onset is the mid- to late 50s; fewer than 15% of lichen sclerosus cases present in children.1,2 Case 1 represents presentation of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a premenopausal woman, which is uncommon.

The classic presentation of lichen sclerosus is a well-defined white, atrophic plaque with a wrinkled surface appearance located on the vulva, perineum, and perianal skin. Less commonly, examination may reveal white papules and macules, pallor with overlying edema, or hyperpigmentation. Loss of labia minora tissue and phimosis of the clitoral hood also are often present in patients with untreated lichen sclerosus.

Additionally, secondary changes, such as erosions, fissuring, and blisters, can be seen on examination. The most frequent symptom associated with lichen sclerosus is intense itching of the affected area. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, dysuria, sexual dysfunction, and bleeding. Occasionally, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic.1 Like other autoimmune conditions, lichen sclerosus may persist indefinitely, highlighting the importance of effective treatment.

How should we evaluate and treat patients with these symptoms?

Perform a skin biopsy and start treatment with very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment daily for at least 6 weeks.

Skin biopsy. Definitive diagnosis of lichen sclerosus is made based on a skin biopsy. Because treatment can impact the interpretation of a skin biopsy, a biopsy is optimally performed prior to treatment initiation.

The patient in Case 1 underwent biopsy of the left labia majora. Results were consistent with early lichen sclerosus. The patient in Case 2 was reluctant to proceed with vulvar biopsy.

A biopsy specimen should be taken from the affected area that is most white in appearance.1

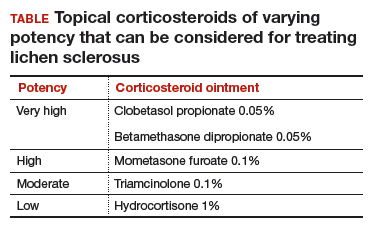

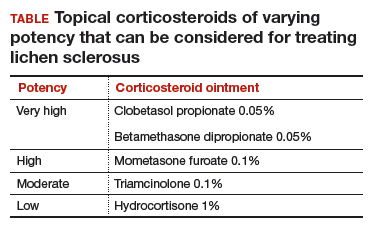

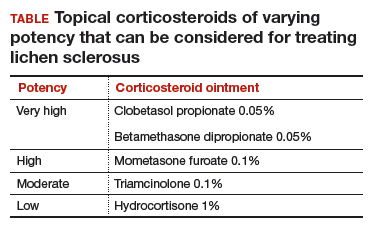

Topical treatment. To induce remission, twice-daily application of very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment to the affected area for at least 6 weeks is recommended. Once the skin color and texture have normalized, the topical corticosteroid strength (and frequency of application) can slowly be reduced to the lowest potency/frequency at which the patient remains in remission. Examples of very high–, high-, moderate-, and low-potency corticosteroid ointments are listed in the TABLE.

Follow-up. Evaluate the patient every 3 months until the topical steroid potency remains stable and the skin appearance is normal.

Treat early, and aggressively, to prevent complications

Early diagnosis and aggressive intervention are important in managing this disease process. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, significant scarring and deformation of the vulva can occur.1

Neoplastic transformation of lichen sclerosus into vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma can occur (mean incidence, 2.8%). However, the literature reports significant variability in the incidence, ranging between 0% and 31%.3 Published reports support decreased scarring and future development of malignancies in patients who adhere to treatment recommendations.4

Symptoms resolved

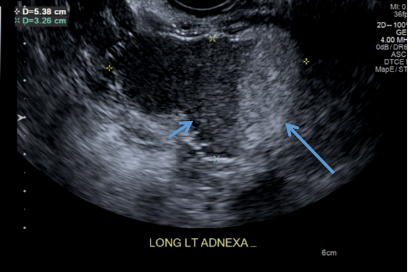

In both cases described here, the patients were treated with clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Both women reported complete resolution of pruritus after treatment. As can be seen in the posttreatment photo of the patient described in Case 1, her vulvar inflammation resolved (FIGURE 4).

These cases represent the varied exam findings in patients experiencing vulvar pruritus with early (Case 1) versus more advanced (Case 2) lichen sclerosus. In addition, they underscore that appropriate evaluation and management of lichen sclerosus can produce excellent treatment results.

- Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:695.

- Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

- Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and neoplastic transformation: a retrospective study of 976 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:180-183.

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061-1067.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory skin disease that primarily affects the genital and perianal skin of postmenopausal women. The mean age of onset is the mid- to late 50s; fewer than 15% of lichen sclerosus cases present in children.1,2 Case 1 represents presentation of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a premenopausal woman, which is uncommon.

The classic presentation of lichen sclerosus is a well-defined white, atrophic plaque with a wrinkled surface appearance located on the vulva, perineum, and perianal skin. Less commonly, examination may reveal white papules and macules, pallor with overlying edema, or hyperpigmentation. Loss of labia minora tissue and phimosis of the clitoral hood also are often present in patients with untreated lichen sclerosus.

Additionally, secondary changes, such as erosions, fissuring, and blisters, can be seen on examination. The most frequent symptom associated with lichen sclerosus is intense itching of the affected area. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, dysuria, sexual dysfunction, and bleeding. Occasionally, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic.1 Like other autoimmune conditions, lichen sclerosus may persist indefinitely, highlighting the importance of effective treatment.

How should we evaluate and treat patients with these symptoms?

Perform a skin biopsy and start treatment with very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment daily for at least 6 weeks.

Skin biopsy. Definitive diagnosis of lichen sclerosus is made based on a skin biopsy. Because treatment can impact the interpretation of a skin biopsy, a biopsy is optimally performed prior to treatment initiation.

The patient in Case 1 underwent biopsy of the left labia majora. Results were consistent with early lichen sclerosus. The patient in Case 2 was reluctant to proceed with vulvar biopsy.

A biopsy specimen should be taken from the affected area that is most white in appearance.1

Topical treatment. To induce remission, twice-daily application of very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment to the affected area for at least 6 weeks is recommended. Once the skin color and texture have normalized, the topical corticosteroid strength (and frequency of application) can slowly be reduced to the lowest potency/frequency at which the patient remains in remission. Examples of very high–, high-, moderate-, and low-potency corticosteroid ointments are listed in the TABLE.

Follow-up. Evaluate the patient every 3 months until the topical steroid potency remains stable and the skin appearance is normal.

Treat early, and aggressively, to prevent complications

Early diagnosis and aggressive intervention are important in managing this disease process. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, significant scarring and deformation of the vulva can occur.1

Neoplastic transformation of lichen sclerosus into vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma can occur (mean incidence, 2.8%). However, the literature reports significant variability in the incidence, ranging between 0% and 31%.3 Published reports support decreased scarring and future development of malignancies in patients who adhere to treatment recommendations.4

Symptoms resolved

In both cases described here, the patients were treated with clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Both women reported complete resolution of pruritus after treatment. As can be seen in the posttreatment photo of the patient described in Case 1, her vulvar inflammation resolved (FIGURE 4).

These cases represent the varied exam findings in patients experiencing vulvar pruritus with early (Case 1) versus more advanced (Case 2) lichen sclerosus. In addition, they underscore that appropriate evaluation and management of lichen sclerosus can produce excellent treatment results.

Lichen sclerosus

Lichen sclerosus is an inflammatory skin disease that primarily affects the genital and perianal skin of postmenopausal women. The mean age of onset is the mid- to late 50s; fewer than 15% of lichen sclerosus cases present in children.1,2 Case 1 represents presentation of vulvar lichen sclerosus in a premenopausal woman, which is uncommon.

The classic presentation of lichen sclerosus is a well-defined white, atrophic plaque with a wrinkled surface appearance located on the vulva, perineum, and perianal skin. Less commonly, examination may reveal white papules and macules, pallor with overlying edema, or hyperpigmentation. Loss of labia minora tissue and phimosis of the clitoral hood also are often present in patients with untreated lichen sclerosus.

Additionally, secondary changes, such as erosions, fissuring, and blisters, can be seen on examination. The most frequent symptom associated with lichen sclerosus is intense itching of the affected area. Other symptoms include dyspareunia, dysuria, sexual dysfunction, and bleeding. Occasionally, lichen sclerosus is asymptomatic.1 Like other autoimmune conditions, lichen sclerosus may persist indefinitely, highlighting the importance of effective treatment.

How should we evaluate and treat patients with these symptoms?

Perform a skin biopsy and start treatment with very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment daily for at least 6 weeks.

Skin biopsy. Definitive diagnosis of lichen sclerosus is made based on a skin biopsy. Because treatment can impact the interpretation of a skin biopsy, a biopsy is optimally performed prior to treatment initiation.

The patient in Case 1 underwent biopsy of the left labia majora. Results were consistent with early lichen sclerosus. The patient in Case 2 was reluctant to proceed with vulvar biopsy.

A biopsy specimen should be taken from the affected area that is most white in appearance.1

Topical treatment. To induce remission, twice-daily application of very high–potency topical corticosteroid ointment to the affected area for at least 6 weeks is recommended. Once the skin color and texture have normalized, the topical corticosteroid strength (and frequency of application) can slowly be reduced to the lowest potency/frequency at which the patient remains in remission. Examples of very high–, high-, moderate-, and low-potency corticosteroid ointments are listed in the TABLE.

Follow-up. Evaluate the patient every 3 months until the topical steroid potency remains stable and the skin appearance is normal.

Treat early, and aggressively, to prevent complications

Early diagnosis and aggressive intervention are important in managing this disease process. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, significant scarring and deformation of the vulva can occur.1

Neoplastic transformation of lichen sclerosus into vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and squamous cell carcinoma can occur (mean incidence, 2.8%). However, the literature reports significant variability in the incidence, ranging between 0% and 31%.3 Published reports support decreased scarring and future development of malignancies in patients who adhere to treatment recommendations.4

Symptoms resolved

In both cases described here, the patients were treated with clobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily for 6 weeks. Both women reported complete resolution of pruritus after treatment. As can be seen in the posttreatment photo of the patient described in Case 1, her vulvar inflammation resolved (FIGURE 4).

These cases represent the varied exam findings in patients experiencing vulvar pruritus with early (Case 1) versus more advanced (Case 2) lichen sclerosus. In addition, they underscore that appropriate evaluation and management of lichen sclerosus can produce excellent treatment results.

- Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:695.

- Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

- Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and neoplastic transformation: a retrospective study of 976 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:180-183.

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061-1067.

- Lee A, Fischer G. Diagnosis and treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus: an update for dermatologists. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:695.

- Tong LX, Sun GS, Teng JM. Pediatric lichen sclerosus: a review of the epidemiology and treatment options. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:593-599.

- Micheletti L, Preti M, Radici G, et al. Vulvar lichen sclerosus and neoplastic transformation: a retrospective study of 976 cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2016;20:180-183.

- Lee A, Bradford J, Fischer G. Long-term management of adult vulvar lichen sclerosus: a prospective cohort study of 507 women. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1061-1067.

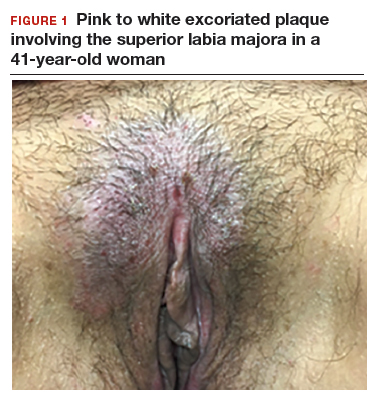

CASE 1: Vulvar pruritus affecting a woman’s quality of life

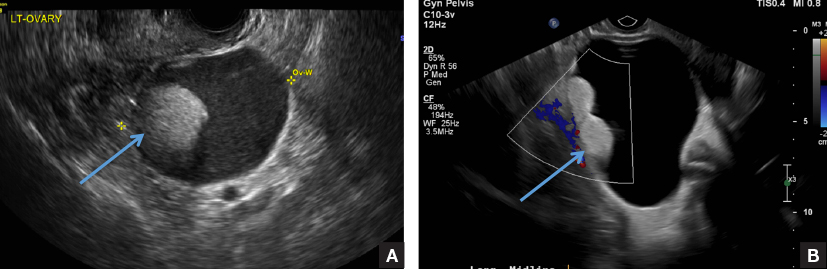

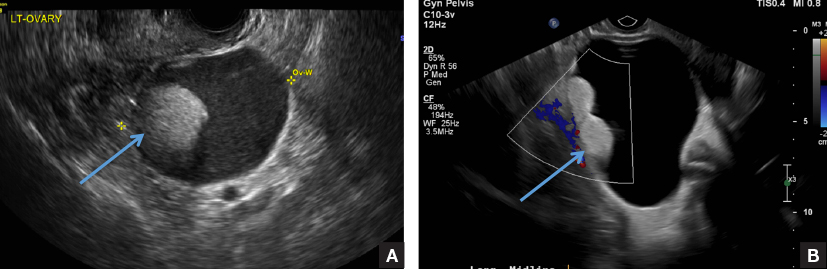

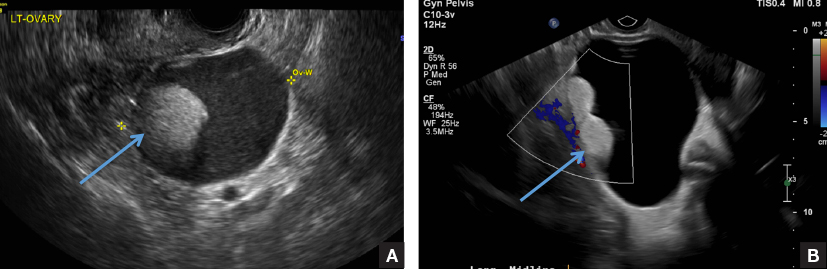

A 41-year-old premenopausal white woman presented to her gynecologist with intense vulvar pruritus for a 6-month duration, with a recent increase in severity (FIGURE 1). She tried treating it with topical antifungal cream, hydrocortisone ointment, and coconut oil, with no improvement. She noted that the intense itching was interfering with her sleep and marriage. The patient denied having an increase in urinary frequency or urgency, dysuria, hematochezia, or bowel changes.

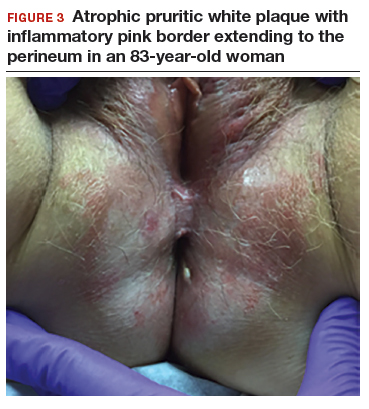

CASE 2: Older woman with long-term persistent genital pruritus

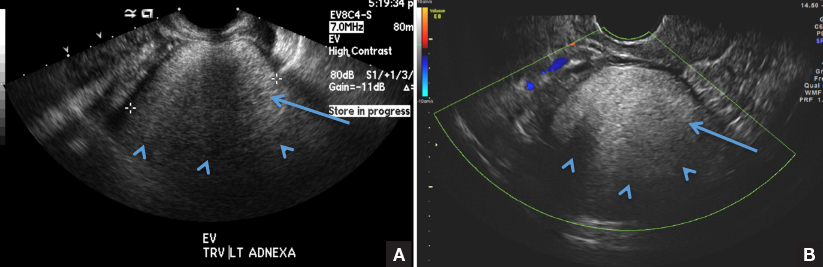

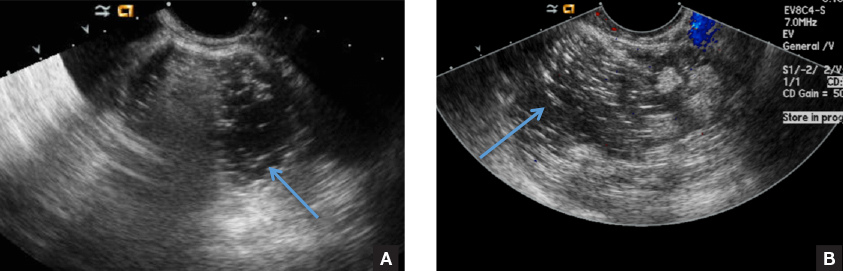

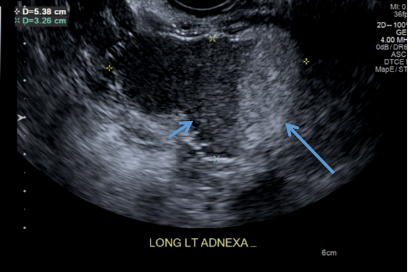

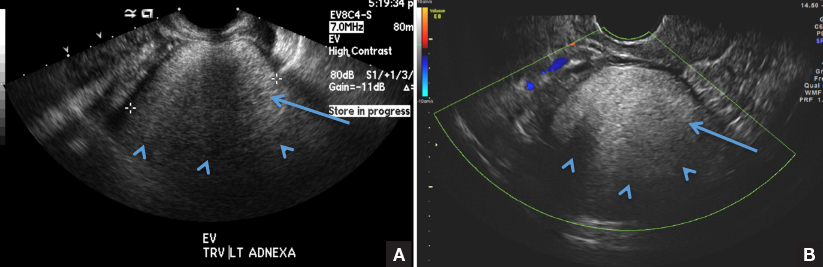

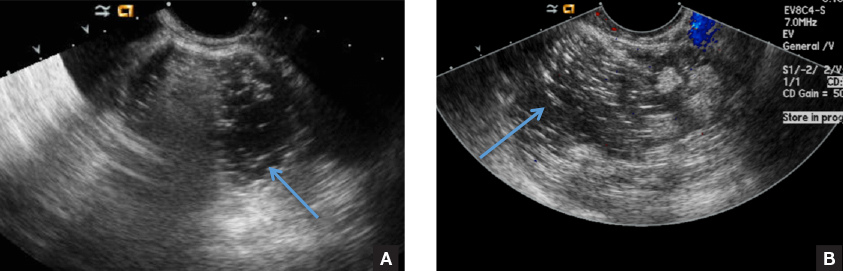

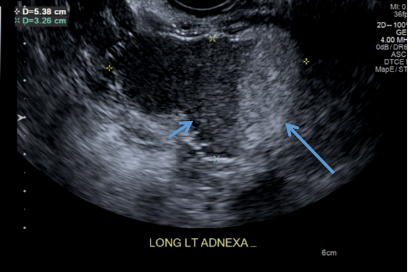

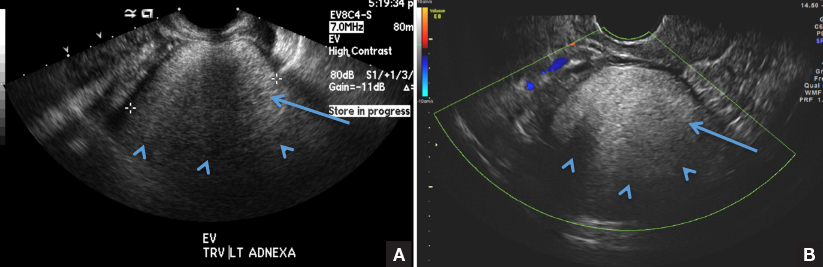

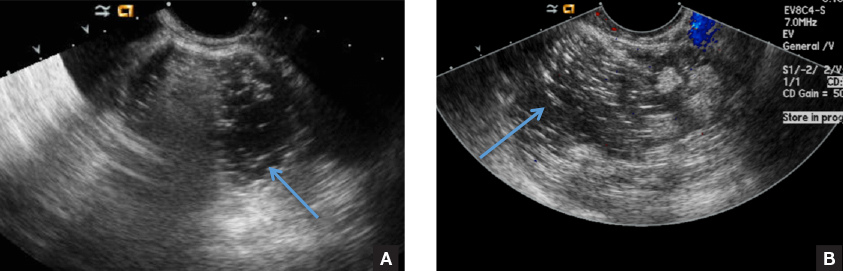

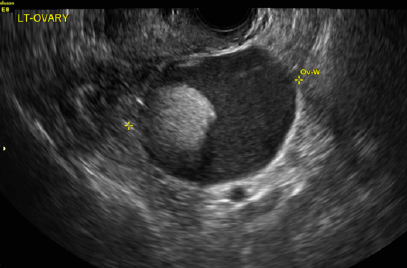

An 83-year-old postmenopausal white woman presented to the dermatology clinic for a regular skin examination. The patient endorsed symptoms of vulvar and perianal pruritus that had persisted for more than 6 months (FIGURES 2 and 3). The genital itching occurred throughout most of the day. The patient previously treated her symptoms with an over-the-counter antifungal cream, which minimally improved the itching.

What is the association of menopausal HT use and risk of Alzheimer disease?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:1665.

Alzheimer disease represents the most common cause of dementia. Although sex hormones may play a role in the etiology of AD in women, studies addressing the impact of menopausal HT on risk of AD have conflicting findings.

Finnish researchers Savolainen-Peltonen and colleagues aimed to compare postmenopausal HT use in women with and without AD. They used national drug and population registries to identify patients with AD, control women without a diagnosis of AD, and data on postmenopausal HT use.

Details of the study

In Finland, reimbursement for treatment related to AD requires cognitive testing, brain imaging, and a statement from a specialist physician. Using national records, the study investigators identified 84,739 women with a diagnosis of AD during the years 1999–2013 and the same number of control women (without AD) during the same period. A national drug reimbursement registry was used to identify HT use from the year 1994.

Findings. Women diagnosed with AD were more likely to have been current or former users of systemic HT than controls (18.6% vs 17.0%, P<.001). The odds ratios (ORs) for AD were 1.09 for the estradiol-only group and 1.17 for the estrogen-progestin group (P<.05 for both comparisons).

Initiation of HT prior to age 60 was less common among AD cases than controls (P = .006). As a continuous variable, age was not a determinant for disease risk in estradiol-only users (OR, 1.0), estrogen-progestin users (OR, 1.0), or any HT use (OR, 1.0).

The exclusive use of vaginal estrogen therapy was not associated with an elevated risk of AD (OR, 0.99).

Study strengths and limitations

This study on the association between HT and AD included a very large number of participants from a national population registry, and the use of HT was objectively determined from a controlled registry (not self-reported). In addition, AD was accurately diagnosed and differentiated from other forms of dementia.

Limitations of the study include the lack of baseline demographic data for AD risk factors for both HT users and controls. Further, an increased risk of AD may have been a cause for HT use and not a consequence, given that initial cognitive impairments may occur 7 to 8 years prior to AD diagnosis and the possibility exists that such women may have sought help for cognitive symptoms from HT. In addition, the lack of brain imaging or neurologic examination to exclude AD might also account for undiagnosed disease in controls. The authors noted that they were unable to compare the use of oral and transdermal HT preparations or the use of cyclic and continuous estrogen-progestin therapy.

Alzheimer disease is more prevalent in women, and women are more likely to be caregivers for individuals with AD than men, making AD an issue of particular concern to midlife and older women. Current guidance from The North American Menopause Society and other organizations does not recommend use of systemic HT to prevent AD.1 As Savolainen-Peltonen and colleagues note in their observational study, the small risk increases for AD with use of HT are subject to bias. Editorialists agree with this concern and point out that a conclusive large randomized trial assessing HT's impact on AD is unlikely to be performed.2 I agree with the editorialists that the findings of this Finnish study should not change current practice. For recently menopausal women who have bothersome vasomotor symptoms and no contraindications, I will continue to counsel that initiating systemic HT is appropriate.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- Maki PM, Girard LM, Manson JE. Menopausal hormone therapy and cognition. BMJ. 2019;364:1877.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:1665.

Alzheimer disease represents the most common cause of dementia. Although sex hormones may play a role in the etiology of AD in women, studies addressing the impact of menopausal HT on risk of AD have conflicting findings.

Finnish researchers Savolainen-Peltonen and colleagues aimed to compare postmenopausal HT use in women with and without AD. They used national drug and population registries to identify patients with AD, control women without a diagnosis of AD, and data on postmenopausal HT use.

Details of the study

In Finland, reimbursement for treatment related to AD requires cognitive testing, brain imaging, and a statement from a specialist physician. Using national records, the study investigators identified 84,739 women with a diagnosis of AD during the years 1999–2013 and the same number of control women (without AD) during the same period. A national drug reimbursement registry was used to identify HT use from the year 1994.

Findings. Women diagnosed with AD were more likely to have been current or former users of systemic HT than controls (18.6% vs 17.0%, P<.001). The odds ratios (ORs) for AD were 1.09 for the estradiol-only group and 1.17 for the estrogen-progestin group (P<.05 for both comparisons).

Initiation of HT prior to age 60 was less common among AD cases than controls (P = .006). As a continuous variable, age was not a determinant for disease risk in estradiol-only users (OR, 1.0), estrogen-progestin users (OR, 1.0), or any HT use (OR, 1.0).

The exclusive use of vaginal estrogen therapy was not associated with an elevated risk of AD (OR, 0.99).

Study strengths and limitations

This study on the association between HT and AD included a very large number of participants from a national population registry, and the use of HT was objectively determined from a controlled registry (not self-reported). In addition, AD was accurately diagnosed and differentiated from other forms of dementia.

Limitations of the study include the lack of baseline demographic data for AD risk factors for both HT users and controls. Further, an increased risk of AD may have been a cause for HT use and not a consequence, given that initial cognitive impairments may occur 7 to 8 years prior to AD diagnosis and the possibility exists that such women may have sought help for cognitive symptoms from HT. In addition, the lack of brain imaging or neurologic examination to exclude AD might also account for undiagnosed disease in controls. The authors noted that they were unable to compare the use of oral and transdermal HT preparations or the use of cyclic and continuous estrogen-progestin therapy.

Alzheimer disease is more prevalent in women, and women are more likely to be caregivers for individuals with AD than men, making AD an issue of particular concern to midlife and older women. Current guidance from The North American Menopause Society and other organizations does not recommend use of systemic HT to prevent AD.1 As Savolainen-Peltonen and colleagues note in their observational study, the small risk increases for AD with use of HT are subject to bias. Editorialists agree with this concern and point out that a conclusive large randomized trial assessing HT's impact on AD is unlikely to be performed.2 I agree with the editorialists that the findings of this Finnish study should not change current practice. For recently menopausal women who have bothersome vasomotor symptoms and no contraindications, I will continue to counsel that initiating systemic HT is appropriate.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Savolainen-Peltonen H, Rahkola-Soisalo P, Hoti F, et al. Use of postmenopausal hormone therapy and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in Finland: nationwide case-control study. BMJ. 2019;364:1665.

Alzheimer disease represents the most common cause of dementia. Although sex hormones may play a role in the etiology of AD in women, studies addressing the impact of menopausal HT on risk of AD have conflicting findings.

Finnish researchers Savolainen-Peltonen and colleagues aimed to compare postmenopausal HT use in women with and without AD. They used national drug and population registries to identify patients with AD, control women without a diagnosis of AD, and data on postmenopausal HT use.

Details of the study

In Finland, reimbursement for treatment related to AD requires cognitive testing, brain imaging, and a statement from a specialist physician. Using national records, the study investigators identified 84,739 women with a diagnosis of AD during the years 1999–2013 and the same number of control women (without AD) during the same period. A national drug reimbursement registry was used to identify HT use from the year 1994.

Findings. Women diagnosed with AD were more likely to have been current or former users of systemic HT than controls (18.6% vs 17.0%, P<.001). The odds ratios (ORs) for AD were 1.09 for the estradiol-only group and 1.17 for the estrogen-progestin group (P<.05 for both comparisons).

Initiation of HT prior to age 60 was less common among AD cases than controls (P = .006). As a continuous variable, age was not a determinant for disease risk in estradiol-only users (OR, 1.0), estrogen-progestin users (OR, 1.0), or any HT use (OR, 1.0).

The exclusive use of vaginal estrogen therapy was not associated with an elevated risk of AD (OR, 0.99).

Study strengths and limitations

This study on the association between HT and AD included a very large number of participants from a national population registry, and the use of HT was objectively determined from a controlled registry (not self-reported). In addition, AD was accurately diagnosed and differentiated from other forms of dementia.

Limitations of the study include the lack of baseline demographic data for AD risk factors for both HT users and controls. Further, an increased risk of AD may have been a cause for HT use and not a consequence, given that initial cognitive impairments may occur 7 to 8 years prior to AD diagnosis and the possibility exists that such women may have sought help for cognitive symptoms from HT. In addition, the lack of brain imaging or neurologic examination to exclude AD might also account for undiagnosed disease in controls. The authors noted that they were unable to compare the use of oral and transdermal HT preparations or the use of cyclic and continuous estrogen-progestin therapy.

Alzheimer disease is more prevalent in women, and women are more likely to be caregivers for individuals with AD than men, making AD an issue of particular concern to midlife and older women. Current guidance from The North American Menopause Society and other organizations does not recommend use of systemic HT to prevent AD.1 As Savolainen-Peltonen and colleagues note in their observational study, the small risk increases for AD with use of HT are subject to bias. Editorialists agree with this concern and point out that a conclusive large randomized trial assessing HT's impact on AD is unlikely to be performed.2 I agree with the editorialists that the findings of this Finnish study should not change current practice. For recently menopausal women who have bothersome vasomotor symptoms and no contraindications, I will continue to counsel that initiating systemic HT is appropriate.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- Maki PM, Girard LM, Manson JE. Menopausal hormone therapy and cognition. BMJ. 2019;364:1877.

- The NAMS 2017 Hormone Therapy Position Statement Advisory Panel. The 2017 hormone therapy position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2017;24:728-753.

- Maki PM, Girard LM, Manson JE. Menopausal hormone therapy and cognition. BMJ. 2019;364:1877.

Does the type of menopausal HT used increase the risk of venous thromboembolism?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810.

The Women’s Health Initiative trials, in which menopausal women were randomly assigned to treatment with oral CEE or placebo, found that statistically the largest risk associated with menopausal hormone therapy (HT) was increased VTE.1 Recently, investigators in the United Kingdom (UK) published results of their research aimed at determining the association between the risk of VTE and the use of different types of HT.2

Details of the study

Vinogradova and colleagues used 2 UK primary care research databases, QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink, to identify cases of incident VTE in general practice records, hospital admissions, and mortality records. They identified 80,396 women (aged 40 to 79 years) diagnosed with VTE between 1998 and 2017 and 391,494 control women matched by age and general practice. The mean age of the case and control women was approximately 64 years; the great majority of women were white. Analyses were adjusted for smoking, body mass index (BMI), family history of VTE, and comorbidities associated with VTE.

Types of HT used. The investigators found that 5,795 (7.2%) women with VTE and 21,670 (5.5%) controls were exposed to HT in the 90 days before the index date (the first date of VTE diagnosis for cases became the index date for matched controls). In those exposed to HT:

- 4,915 (85%) cases and 16,938 (78%) controls used oral preparations (including 102 [1.8%] cases and 312 [1.4%] controls who also had transdermal preparations)

- 880 (14%) cases and 4,731 (19%) controls used transdermal HT only.

Association of VTE with HT. Risk of VTE was increased with all oral HT formulations, including combined (estrogen plus progestogen) and estrogen-only preparations. Use of oral CEE (odds ratio [OR], 1.49) and estradiol (OR, 1.27) were both associated with an elevated risk of VTE (P<.05 for both comparisons). In contrast, use of transdermal estradiol (the great majority of which was administered by patch) was not associated with an elevated risk of VTE (OR, 0.96).

Direct comparison of oral estradiol and CEE found that the lower VTE risk with oral estradiol achieved statistical significance (P = .005). Direct comparison of oral and transdermal estrogen revealed an OR of 1.7 for the oral route of administration (P<.001)

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study used data from the 2 largest primary care databases in the United Kingdom. Analyses were adjusted for numerous confounding factors, including acute and chronic conditions, lifestyle factors, and social deprivation. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted and yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

Several limitations could have resulted in some residual confounding bias. For example, drug exposure information was based on HT prescriptions and not actual use; data on some factors were not available, such as indications for HT, age at menopause, and education level; and for a small proportion of women, some data (smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI) were missing and had to be imputed for analysis.

Although randomized trials have not compared VTE risk with oral versus transdermal estrogen, prior observational studies have consistently suggested that transdermal estrogen does not elevate VTE risk; this is consistent with the results from this large UK study. In my practice, congruent with the authors’ suggestions, I recommend transdermal rather than oral estrogen for patients (notably, those who are obese) who at baseline have risk factors for VTE. For menopausal women for whom use of oral estrogen is indicated, I recommend estradiol rather than CEE, since estradiol is less expensive and, based on this study’s results, may be safer than CEE.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368.

- Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810.

The Women’s Health Initiative trials, in which menopausal women were randomly assigned to treatment with oral CEE or placebo, found that statistically the largest risk associated with menopausal hormone therapy (HT) was increased VTE.1 Recently, investigators in the United Kingdom (UK) published results of their research aimed at determining the association between the risk of VTE and the use of different types of HT.2

Details of the study

Vinogradova and colleagues used 2 UK primary care research databases, QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink, to identify cases of incident VTE in general practice records, hospital admissions, and mortality records. They identified 80,396 women (aged 40 to 79 years) diagnosed with VTE between 1998 and 2017 and 391,494 control women matched by age and general practice. The mean age of the case and control women was approximately 64 years; the great majority of women were white. Analyses were adjusted for smoking, body mass index (BMI), family history of VTE, and comorbidities associated with VTE.

Types of HT used. The investigators found that 5,795 (7.2%) women with VTE and 21,670 (5.5%) controls were exposed to HT in the 90 days before the index date (the first date of VTE diagnosis for cases became the index date for matched controls). In those exposed to HT:

- 4,915 (85%) cases and 16,938 (78%) controls used oral preparations (including 102 [1.8%] cases and 312 [1.4%] controls who also had transdermal preparations)

- 880 (14%) cases and 4,731 (19%) controls used transdermal HT only.

Association of VTE with HT. Risk of VTE was increased with all oral HT formulations, including combined (estrogen plus progestogen) and estrogen-only preparations. Use of oral CEE (odds ratio [OR], 1.49) and estradiol (OR, 1.27) were both associated with an elevated risk of VTE (P<.05 for both comparisons). In contrast, use of transdermal estradiol (the great majority of which was administered by patch) was not associated with an elevated risk of VTE (OR, 0.96).

Direct comparison of oral estradiol and CEE found that the lower VTE risk with oral estradiol achieved statistical significance (P = .005). Direct comparison of oral and transdermal estrogen revealed an OR of 1.7 for the oral route of administration (P<.001)

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study used data from the 2 largest primary care databases in the United Kingdom. Analyses were adjusted for numerous confounding factors, including acute and chronic conditions, lifestyle factors, and social deprivation. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted and yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

Several limitations could have resulted in some residual confounding bias. For example, drug exposure information was based on HT prescriptions and not actual use; data on some factors were not available, such as indications for HT, age at menopause, and education level; and for a small proportion of women, some data (smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI) were missing and had to be imputed for analysis.

Although randomized trials have not compared VTE risk with oral versus transdermal estrogen, prior observational studies have consistently suggested that transdermal estrogen does not elevate VTE risk; this is consistent with the results from this large UK study. In my practice, congruent with the authors’ suggestions, I recommend transdermal rather than oral estrogen for patients (notably, those who are obese) who at baseline have risk factors for VTE. For menopausal women for whom use of oral estrogen is indicated, I recommend estradiol rather than CEE, since estradiol is less expensive and, based on this study’s results, may be safer than CEE.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810.

The Women’s Health Initiative trials, in which menopausal women were randomly assigned to treatment with oral CEE or placebo, found that statistically the largest risk associated with menopausal hormone therapy (HT) was increased VTE.1 Recently, investigators in the United Kingdom (UK) published results of their research aimed at determining the association between the risk of VTE and the use of different types of HT.2

Details of the study

Vinogradova and colleagues used 2 UK primary care research databases, QResearch and Clinical Practice Research Datalink, to identify cases of incident VTE in general practice records, hospital admissions, and mortality records. They identified 80,396 women (aged 40 to 79 years) diagnosed with VTE between 1998 and 2017 and 391,494 control women matched by age and general practice. The mean age of the case and control women was approximately 64 years; the great majority of women were white. Analyses were adjusted for smoking, body mass index (BMI), family history of VTE, and comorbidities associated with VTE.

Types of HT used. The investigators found that 5,795 (7.2%) women with VTE and 21,670 (5.5%) controls were exposed to HT in the 90 days before the index date (the first date of VTE diagnosis for cases became the index date for matched controls). In those exposed to HT:

- 4,915 (85%) cases and 16,938 (78%) controls used oral preparations (including 102 [1.8%] cases and 312 [1.4%] controls who also had transdermal preparations)

- 880 (14%) cases and 4,731 (19%) controls used transdermal HT only.

Association of VTE with HT. Risk of VTE was increased with all oral HT formulations, including combined (estrogen plus progestogen) and estrogen-only preparations. Use of oral CEE (odds ratio [OR], 1.49) and estradiol (OR, 1.27) were both associated with an elevated risk of VTE (P<.05 for both comparisons). In contrast, use of transdermal estradiol (the great majority of which was administered by patch) was not associated with an elevated risk of VTE (OR, 0.96).

Direct comparison of oral estradiol and CEE found that the lower VTE risk with oral estradiol achieved statistical significance (P = .005). Direct comparison of oral and transdermal estrogen revealed an OR of 1.7 for the oral route of administration (P<.001)

Continue to: Study strengths and weaknesses

Study strengths and weaknesses

This study used data from the 2 largest primary care databases in the United Kingdom. Analyses were adjusted for numerous confounding factors, including acute and chronic conditions, lifestyle factors, and social deprivation. Additional sensitivity analyses were conducted and yielded results similar to those of the main analysis.

Several limitations could have resulted in some residual confounding bias. For example, drug exposure information was based on HT prescriptions and not actual use; data on some factors were not available, such as indications for HT, age at menopause, and education level; and for a small proportion of women, some data (smoking status, alcohol consumption, BMI) were missing and had to be imputed for analysis.

Although randomized trials have not compared VTE risk with oral versus transdermal estrogen, prior observational studies have consistently suggested that transdermal estrogen does not elevate VTE risk; this is consistent with the results from this large UK study. In my practice, congruent with the authors’ suggestions, I recommend transdermal rather than oral estrogen for patients (notably, those who are obese) who at baseline have risk factors for VTE. For menopausal women for whom use of oral estrogen is indicated, I recommend estradiol rather than CEE, since estradiol is less expensive and, based on this study’s results, may be safer than CEE.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368.

- Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810.

- Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women's Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368.

- Vinogradova Y, Coupland C, Hippisley-Cox J. Use of hormone replacement therapy and risk of venous thromboembolism: nested case-control studies using the QResearch and CPRD databases. BMJ. 2019;364:k4810.

How does HT in recent and 10+ years past menopause affect atherosclerosis progression?

Expert Commentary

Sriprasert I, Hodis HN, Karim R, et al. Differential effect of plasma estradiol on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in early versus late postmenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:293-300. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01600.

In 2016, the primary findings of the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) demonstrated that oral E2 administered to women who were less than 6 years postmenopause slowed progression of subclinical atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT), while it had no effect in women who were at least 10 years postmenopause.1

That trial included 643 healthy women without cardiovascular disease who at enrollment had a median age of 55.4 years in the early postmenopause group (median 3.5 years since menopause) and 63.6 years in the late postmenopause group (median 14.3 years since menopause). The study medications were oral estradiol 1 mg daily plus progesterone vaginal gel for women with a uterus or placebo and placebo gel for a median of 5 years.

The investigators found also that, in contrast with CIMT, cardiac computed tomography (CT) measures of atherosclerosis did not differ significantly between the estradiol and placebo groups, regardless of age.1

Posttrial data analysis revealed a new finding

In a secondary analysis of data from the ELITE trial, Sriprasert and colleagues dug deeper to assess the impact of plasma E2 levels on progression of subclinical atherosclerosis.2

Among 596 women (69.6% white non-Hispanic, 8.7% black, 13.3% Hispanic, and 8.4% Asian/Pacific Islander), E2 levels were available in 248 women in early postmenopause (mean age, 54.7 years) and 348 women in late postmenopause (median age, 63.6 years).

For women in the estradiol-treated group, mean E2 levels during the trial as well as change of E2 levels from baseline were significantly higher in the early postmenopause group than in the late postmenopause group, even though both groups had similar adherence based on pill count. For those in the placebo group, mean E2 levels and change of E2 levels from baseline were equivalent in early and late menopause.

In the E2-treated group and the placebo group combined, the mixed effects analysis of the CIMT progression rate (based on the mean E2 level during the trial) demonstrated that a higher level of E2 was inversely associated with the CIMT progression rate in early postmenopausal women (beta coefficient = -0.04 [95% confidence interval (CI), -0.09 to -0.001] μm CIMT per year per 1 pg/mL estradiol; P = .04). However, a higher level of E2 was positively associated (beta coefficient = 0.063 [95% CI, 0.018 to 0.107] μm CIMT per year per 1 pg/mL estradiol; P = .006) with CIMT progression rate in the late postmenopausal women.

Continue to: Bottom line...

Bottom line. E2 levels resulting from administration of oral estradiol were inversely associated with atherosclerosis progression in women in early menopause, but they were positively associated with progression in late postmenopause participants.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

These new findings from a posttrial analysis of ELITE data provide yet further support for the hormone therapy (HT) “timing hypothesis,” which postulates that HT slows atherosclerosis progression in recently menopausal women but has neutral or adverse effects in women who are at least a decade past menopause onset. As the authors suggest, the favorable vascular effects of E2 appear limited to those women (most often in early menopause) who have not yet developed atherosclerosis. Whether or not HT should be considered for cardioprotection remains unresolved (and controversial). By contrast, these data, along with findings from the Women’s Health Initiative,3 provide reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT when prescribed for recently menopausal women with bothersome vasomotor symptoms.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

References

1. Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; for the ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374;1221-1231.

2. Sriprasert I, Hodis HN, Karim R, et al. Differential effect of plasma estradiol on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in early versus late postmenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:293-300. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01600.

3. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368.

Expert Commentary

Sriprasert I, Hodis HN, Karim R, et al. Differential effect of plasma estradiol on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in early versus late postmenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:293-300. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01600.

In 2016, the primary findings of the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) demonstrated that oral E2 administered to women who were less than 6 years postmenopause slowed progression of subclinical atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT), while it had no effect in women who were at least 10 years postmenopause.1

That trial included 643 healthy women without cardiovascular disease who at enrollment had a median age of 55.4 years in the early postmenopause group (median 3.5 years since menopause) and 63.6 years in the late postmenopause group (median 14.3 years since menopause). The study medications were oral estradiol 1 mg daily plus progesterone vaginal gel for women with a uterus or placebo and placebo gel for a median of 5 years.

The investigators found also that, in contrast with CIMT, cardiac computed tomography (CT) measures of atherosclerosis did not differ significantly between the estradiol and placebo groups, regardless of age.1

Posttrial data analysis revealed a new finding

In a secondary analysis of data from the ELITE trial, Sriprasert and colleagues dug deeper to assess the impact of plasma E2 levels on progression of subclinical atherosclerosis.2

Among 596 women (69.6% white non-Hispanic, 8.7% black, 13.3% Hispanic, and 8.4% Asian/Pacific Islander), E2 levels were available in 248 women in early postmenopause (mean age, 54.7 years) and 348 women in late postmenopause (median age, 63.6 years).

For women in the estradiol-treated group, mean E2 levels during the trial as well as change of E2 levels from baseline were significantly higher in the early postmenopause group than in the late postmenopause group, even though both groups had similar adherence based on pill count. For those in the placebo group, mean E2 levels and change of E2 levels from baseline were equivalent in early and late menopause.

In the E2-treated group and the placebo group combined, the mixed effects analysis of the CIMT progression rate (based on the mean E2 level during the trial) demonstrated that a higher level of E2 was inversely associated with the CIMT progression rate in early postmenopausal women (beta coefficient = -0.04 [95% confidence interval (CI), -0.09 to -0.001] μm CIMT per year per 1 pg/mL estradiol; P = .04). However, a higher level of E2 was positively associated (beta coefficient = 0.063 [95% CI, 0.018 to 0.107] μm CIMT per year per 1 pg/mL estradiol; P = .006) with CIMT progression rate in the late postmenopausal women.

Continue to: Bottom line...

Bottom line. E2 levels resulting from administration of oral estradiol were inversely associated with atherosclerosis progression in women in early menopause, but they were positively associated with progression in late postmenopause participants.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

These new findings from a posttrial analysis of ELITE data provide yet further support for the hormone therapy (HT) “timing hypothesis,” which postulates that HT slows atherosclerosis progression in recently menopausal women but has neutral or adverse effects in women who are at least a decade past menopause onset. As the authors suggest, the favorable vascular effects of E2 appear limited to those women (most often in early menopause) who have not yet developed atherosclerosis. Whether or not HT should be considered for cardioprotection remains unresolved (and controversial). By contrast, these data, along with findings from the Women’s Health Initiative,3 provide reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT when prescribed for recently menopausal women with bothersome vasomotor symptoms.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

References

1. Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; for the ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374;1221-1231.

2. Sriprasert I, Hodis HN, Karim R, et al. Differential effect of plasma estradiol on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in early versus late postmenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:293-300. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01600.

3. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368.

Expert Commentary

Sriprasert I, Hodis HN, Karim R, et al. Differential effect of plasma estradiol on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in early versus late postmenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:293-300. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01600.

In 2016, the primary findings of the Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol (ELITE) demonstrated that oral E2 administered to women who were less than 6 years postmenopause slowed progression of subclinical atherosclerosis as assessed by carotid artery intima-media thickness (CIMT), while it had no effect in women who were at least 10 years postmenopause.1

That trial included 643 healthy women without cardiovascular disease who at enrollment had a median age of 55.4 years in the early postmenopause group (median 3.5 years since menopause) and 63.6 years in the late postmenopause group (median 14.3 years since menopause). The study medications were oral estradiol 1 mg daily plus progesterone vaginal gel for women with a uterus or placebo and placebo gel for a median of 5 years.

The investigators found also that, in contrast with CIMT, cardiac computed tomography (CT) measures of atherosclerosis did not differ significantly between the estradiol and placebo groups, regardless of age.1

Posttrial data analysis revealed a new finding

In a secondary analysis of data from the ELITE trial, Sriprasert and colleagues dug deeper to assess the impact of plasma E2 levels on progression of subclinical atherosclerosis.2

Among 596 women (69.6% white non-Hispanic, 8.7% black, 13.3% Hispanic, and 8.4% Asian/Pacific Islander), E2 levels were available in 248 women in early postmenopause (mean age, 54.7 years) and 348 women in late postmenopause (median age, 63.6 years).

For women in the estradiol-treated group, mean E2 levels during the trial as well as change of E2 levels from baseline were significantly higher in the early postmenopause group than in the late postmenopause group, even though both groups had similar adherence based on pill count. For those in the placebo group, mean E2 levels and change of E2 levels from baseline were equivalent in early and late menopause.

In the E2-treated group and the placebo group combined, the mixed effects analysis of the CIMT progression rate (based on the mean E2 level during the trial) demonstrated that a higher level of E2 was inversely associated with the CIMT progression rate in early postmenopausal women (beta coefficient = -0.04 [95% confidence interval (CI), -0.09 to -0.001] μm CIMT per year per 1 pg/mL estradiol; P = .04). However, a higher level of E2 was positively associated (beta coefficient = 0.063 [95% CI, 0.018 to 0.107] μm CIMT per year per 1 pg/mL estradiol; P = .006) with CIMT progression rate in the late postmenopausal women.

Continue to: Bottom line...

Bottom line. E2 levels resulting from administration of oral estradiol were inversely associated with atherosclerosis progression in women in early menopause, but they were positively associated with progression in late postmenopause participants.

WHAT THIS EVIDENCE MEANS FOR PRACTICE

These new findings from a posttrial analysis of ELITE data provide yet further support for the hormone therapy (HT) “timing hypothesis,” which postulates that HT slows atherosclerosis progression in recently menopausal women but has neutral or adverse effects in women who are at least a decade past menopause onset. As the authors suggest, the favorable vascular effects of E2 appear limited to those women (most often in early menopause) who have not yet developed atherosclerosis. Whether or not HT should be considered for cardioprotection remains unresolved (and controversial). By contrast, these data, along with findings from the Women’s Health Initiative,3 provide reassurance regarding the cardiovascular safety of HT when prescribed for recently menopausal women with bothersome vasomotor symptoms.

ANDREW M. KAUNITZ, MD

References

1. Hodis HN, Mack WJ, Henderson VW, et al; for the ELITE Research Group. Vascular effects of early versus late postmenopausal treatment with estradiol. N Engl J Med. 2016;374;1221-1231.

2. Sriprasert I, Hodis HN, Karim R, et al. Differential effect of plasma estradiol on subclinical atherosclerosis progression in early versus late postmenopause. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:293-300. doi:10.1210/jc.2018-01600.

3. Manson JE, Chlebowski RT, Stefanick ML, et al. Menopausal hormone therapy and health outcomes during the intervention and extended poststopping phases of the Women’s Health Initiative randomized trials. JAMA. 2013;310:1353-1368.

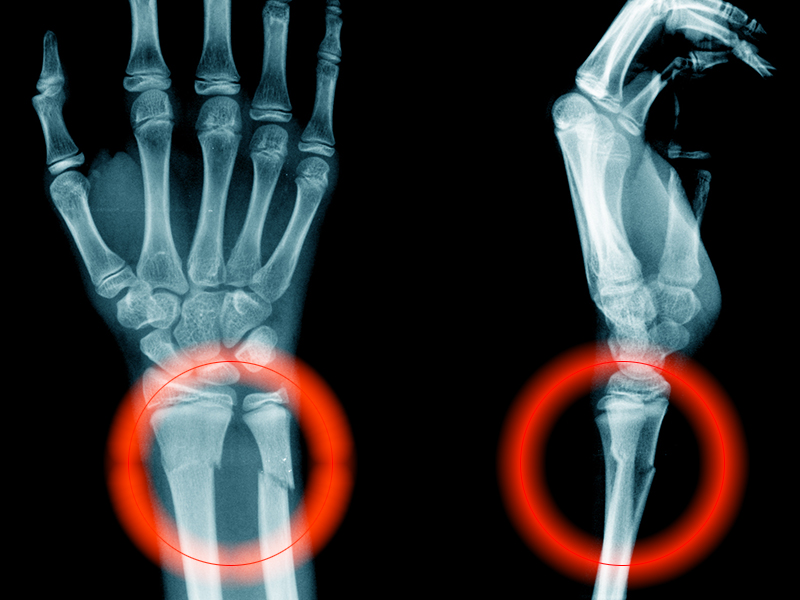

To prevent fractures, treating only women with osteoporosis is not enough

The conventional bone mineral density threshold for initiating treatment to prevent fragility fractures is a T-score of less than -2.5 (the World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis).1 However, most fractures experienced by postmenopausal women occur not in osteoporotic women but in those with low bone mass (osteopenia).2

Investigators in New Zealand recently published the results of a randomized controlled trial they conducted to determine the efficacy of zoledronate (zoledronic acid) in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women.3 They enrolled women age 65 years or older with osteopenia of the hip and randomly assigned the participants to 4 intravenous infusions of 5 mg zoledronic acid or placebo at 18-month intervals for 6 years.

Zoledronic acid reduced fracture risk

The trial included 2,000 postmenopausal women (mean age at baseline, 71 years; 94% European ethnicity) with a T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 at either the total hip or the femoral neck on either side. Both hips were assessed. The women received either zoledronic acid treatment or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Candidates were excluded if they regularly used bone-active drugs in the previous year.

Fragility fractures were noted in 190 women in the placebo group and in 122 women treated with zoledronic acid (hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.79, P<.001). The number of women that would need to be treated to prevent the occurrence of a fracture in 1 woman was 15.

Compared with placebo, zoledronic acid also lowered the risk of nonvertebral, symptomatic, and vertebral fractures as well as height loss (P≤.003 for these 4 comparisons). Relatively few adverse events occurred with zoledronic acid treatment. No atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in either group.

Trial closes the knowledge gap regarding treatment thresholds

This trial’s findings underscore the importance of age as a risk factor for fragility fracture and clarify that pharmacologic treatment is appropriate not only for women with osteoporosis but also for older postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

As the authors point out, administration of zoledronic acid less often than annually can be highly effective in preventing fractures; they recommend future trials of administration of this intravenous bisphosphonate at intervals less frequent than 18 months. Although the absence of atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw is reassuring, the authors note that their trial was underpowered to assess these uncommon events.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- World Health Organization. WHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Summary meeting report, Brussels, Belgium, 5-7 May 2004. https://www. who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108-1112.

- Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, et al. Fracture prevention with zoledronate in older women with osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2018. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808082.

The conventional bone mineral density threshold for initiating treatment to prevent fragility fractures is a T-score of less than -2.5 (the World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis).1 However, most fractures experienced by postmenopausal women occur not in osteoporotic women but in those with low bone mass (osteopenia).2

Investigators in New Zealand recently published the results of a randomized controlled trial they conducted to determine the efficacy of zoledronate (zoledronic acid) in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women.3 They enrolled women age 65 years or older with osteopenia of the hip and randomly assigned the participants to 4 intravenous infusions of 5 mg zoledronic acid or placebo at 18-month intervals for 6 years.

Zoledronic acid reduced fracture risk

The trial included 2,000 postmenopausal women (mean age at baseline, 71 years; 94% European ethnicity) with a T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 at either the total hip or the femoral neck on either side. Both hips were assessed. The women received either zoledronic acid treatment or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Candidates were excluded if they regularly used bone-active drugs in the previous year.

Fragility fractures were noted in 190 women in the placebo group and in 122 women treated with zoledronic acid (hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.79, P<.001). The number of women that would need to be treated to prevent the occurrence of a fracture in 1 woman was 15.

Compared with placebo, zoledronic acid also lowered the risk of nonvertebral, symptomatic, and vertebral fractures as well as height loss (P≤.003 for these 4 comparisons). Relatively few adverse events occurred with zoledronic acid treatment. No atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in either group.

Trial closes the knowledge gap regarding treatment thresholds

This trial’s findings underscore the importance of age as a risk factor for fragility fracture and clarify that pharmacologic treatment is appropriate not only for women with osteoporosis but also for older postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

As the authors point out, administration of zoledronic acid less often than annually can be highly effective in preventing fractures; they recommend future trials of administration of this intravenous bisphosphonate at intervals less frequent than 18 months. Although the absence of atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw is reassuring, the authors note that their trial was underpowered to assess these uncommon events.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The conventional bone mineral density threshold for initiating treatment to prevent fragility fractures is a T-score of less than -2.5 (the World Health Organization criteria for osteoporosis).1 However, most fractures experienced by postmenopausal women occur not in osteoporotic women but in those with low bone mass (osteopenia).2

Investigators in New Zealand recently published the results of a randomized controlled trial they conducted to determine the efficacy of zoledronate (zoledronic acid) in preventing fractures in postmenopausal women.3 They enrolled women age 65 years or older with osteopenia of the hip and randomly assigned the participants to 4 intravenous infusions of 5 mg zoledronic acid or placebo at 18-month intervals for 6 years.

Zoledronic acid reduced fracture risk

The trial included 2,000 postmenopausal women (mean age at baseline, 71 years; 94% European ethnicity) with a T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 at either the total hip or the femoral neck on either side. Both hips were assessed. The women received either zoledronic acid treatment or placebo in a 1:1 ratio. Candidates were excluded if they regularly used bone-active drugs in the previous year.

Fragility fractures were noted in 190 women in the placebo group and in 122 women treated with zoledronic acid (hazard ratio [HR], 0.63; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.50–0.79, P<.001). The number of women that would need to be treated to prevent the occurrence of a fracture in 1 woman was 15.

Compared with placebo, zoledronic acid also lowered the risk of nonvertebral, symptomatic, and vertebral fractures as well as height loss (P≤.003 for these 4 comparisons). Relatively few adverse events occurred with zoledronic acid treatment. No atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw occurred in either group.

Trial closes the knowledge gap regarding treatment thresholds

This trial’s findings underscore the importance of age as a risk factor for fragility fracture and clarify that pharmacologic treatment is appropriate not only for women with osteoporosis but also for older postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

As the authors point out, administration of zoledronic acid less often than annually can be highly effective in preventing fractures; they recommend future trials of administration of this intravenous bisphosphonate at intervals less frequent than 18 months. Although the absence of atypical femoral fractures or cases of osteonecrosis of the jaw is reassuring, the authors note that their trial was underpowered to assess these uncommon events.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- World Health Organization. WHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Summary meeting report, Brussels, Belgium, 5-7 May 2004. https://www. who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108-1112.

- Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, et al. Fracture prevention with zoledronate in older women with osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2018. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808082.

- World Health Organization. WHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level. Summary meeting report, Brussels, Belgium, 5-7 May 2004. https://www. who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108-1112.

- Reid IR, Horne AM, Mihov B, et al. Fracture prevention with zoledronate in older women with osteopenia. N Engl J Med. 2018. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1808082.

Is the most effective emergency contraception easily obtained at US pharmacies?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

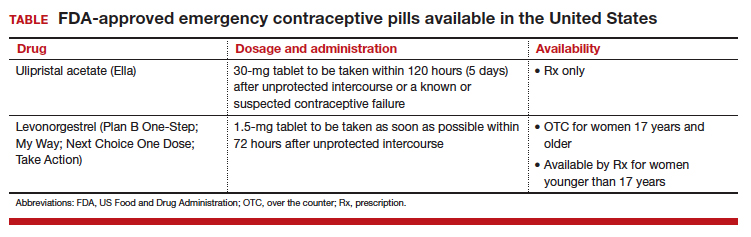

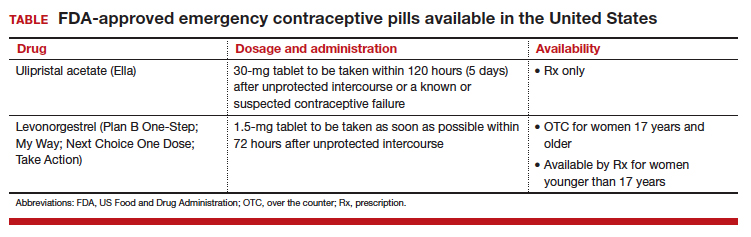

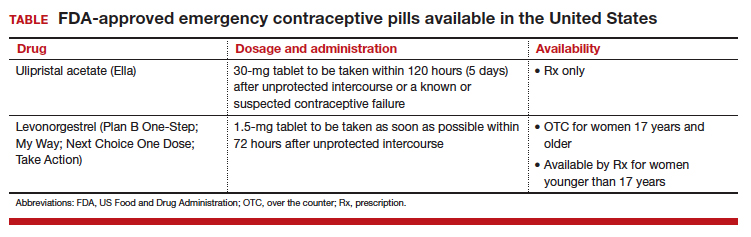

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Although it is available only by prescription, ulipristal acetate provides emergency contraception that is more effective than the emergency contraception provided by levonorgestrel (LNG), which is available without a prescription (TABLE). In addition, ulipristal acetate appears more effective than LNG in obese and overweight women.1,2 Package labeling for ulipristal acetate indicates that a single 30-mg tablet should be taken orally within 5 days of unprotected sex.

According to a survey of pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate in Hawaii, 2.6% of retail pharmacies had the drug immediately available, compared with 82.4% for LNG, and 22.8% reported the ability to order it.3 To assess pharmacy availability of ulipristal acetate on a nationwide scale, Shigesato and colleagues conducted a national “secret shopper” telephone survey in 10 cities (each with a population of at least 500,000) in all major regions of the United States.

Details of the study

Independent pharmacies (defined as having fewer than 5 locations within the city) and chain pharmacies were included in the survey. The survey callers, representing themselves as uninsured 18-year-old women attempting to fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate, followed a semistructured questionnaire and recorded the responses. They asked about the immediate availability of ulipristal acetate and LNG, the pharmacy’s ability to order ulipristal acetate if not immediately available, out-of-pocket costs, instructions for use, and the differences between ulipristal acetate and LNG. Questions were directed to whichever pharmacy staff member answered the phone; callers did not specifically ask to speak to a pharmacist.

Of the 344 pharmacies included in this analysis, 10% (33) indicated that they could fill a prescription for ulipristal acetate immediately. While availability did not vary by region, there was a difference in immediate availability by city.

Almost three-quarters of pharmacies without immediate drug availability indicated that they could order ulipristal acetate, with a median predicted time for availability of 24 hours. Of the chain pharmacies, 81% (167 of 205) reported the ability to order ulipristal acetate, compared with 55% (57 of 106) of independent pharmacies.

When asked if ulipristal acetate was different from LNG, more than one-third of pharmacy personnel contacted stated either that there was no difference between ulipristal acetate and LNG or that they were not sure of a difference.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The authors noted that the secret shopper methodology, along with having callers speak to the pharmacy staff person who answered the call (rather than asking for the pharmacist), provided data that closely approximates real-world patient experiences.

Since more pharmacies than anticipated met exclusion criteria for the study, the estimate of ulipristal acetate immediate availability was less precise than the power analysis predicted. Further, results from the 10 large, geographically diverse cities may not be representative of all similarly sized cities nationally or all areas of the United States.

As the authors point out, a low prevalence of pharmacies stock ulipristal acetate, and more than 25% are not able to order this emergency contraception. This underscores the fact that access to the most effective oral emergency contraception is limited for US women. I agree with the authors’ speculation that access to ulipristal acetate may be even lower in rural areas. In many European countries, ulipristal acetate is available without a prescription. Clinicians caring for women who may benefit from emergency contraception, particularly those using short-acting or less effective contraceptives, may wish to prescribe ulipristal acetate in advance of need.

—Andrew M. Kaunitz, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

- Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104.

- Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–367.

- Bullock H, Steele S, Kurata N, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in Hawaii: is a prescription enough? Contraception. 2016;93(5):452–454.

Does hormone therapy increase breast cancer risk in BRCA1 mutation carriers?

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Prophylactic bilateral oophorectomy (BO) reduces the risk of future ovarian cancer in women who have BRCA1 gene mutations. Women in this high-risk population may be reluctant, however, to use menopausal hormone therapy (HT) to mitigate the symptoms of surgical menopause because of concerns that it might elevate their risk of breast cancer.

To determine the relationship between HT use and BRCA1-associated breast cancer, Kotsopoulos and colleagues conducted a multicenter international cohort study. They prospectively followed women with BRCA1 mutations who had undergone BO and had intact breasts and no history of breast cancer.

Details of the study