User login

Treatment of Seborrheic Dermatitis in Black Patients

Treatment of Seborrheic Dermatitis in Black Patients

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that predominantly affects areas with high concentrations of sebaceous glands such as the scalp and face. Up to 5% of the worldwide population is affected by SD each year, causing a major burden of disease for patients and the health care system.1 In 2023, the cost of medical treatment for SD in the United States was $300 million, with outpatient office visits alone costing $58 million and prescription drugs costing $109 million. Indirect costs of disease (eg, lost workdays) account for another $51 million.1 Since SD frequently manifests on the face, it tends to have negative effects on the patient’s quality of life, resulting in psychological distress and low self-esteem.2

Patients with SD may describe symptoms of excessive dandruff and itching along with hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin; Black patients tend to present with the classic manifestations: a combination of scaling, flaking, and erythematous patches on the scalp, ears, and face, particularly around the eyebrows, eyelids, and nose. With SD being the second most common diagnosis in Black patients who seek care from a dermatologist, it is important to have effective treatment approaches for SD in this patient population.3

In this study, we aimed to evaluate medical and nonmedical treatment options for SD in Black patients by identifying common practices and products mentioned on consumer websites and in the medical literature.

Methods

A Google search was conducted during 2 time periods (September 2022—October 2022 and March 2023—April 2023) using the terms products for itchy scalp in Black patients, products for dandruff in Black patients, itchy scalp in Black women, itchy scalp in Black men, treatment for scalp itch in Black patients, and dry scalp in Black hair. Products that were recommended by at least 1 website on the first page of search results were included in our list of products, and the ingredients were reviewed by the authors. We excluded individual retailer websites as well as those that did not provide specific recommendations on products or ingredients to use when treating SD. To ensure reliability and standardization, we did not review products that were suggested by ads in the shopping section on the first page of search results.

We also evaluated medical treatments used for SD in dermatology literature. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms seborrheic dermatitis treatment for Black patients, treatment for dandruff for Black patients, and seborrheic dermatitis and skin of color was conducted. We excluded articles that did not address treatment options for SD, were specific to treating SD in patient populations with specific comorbidities being studied, discussed SD in animals, or were published prior to 1990.

Results

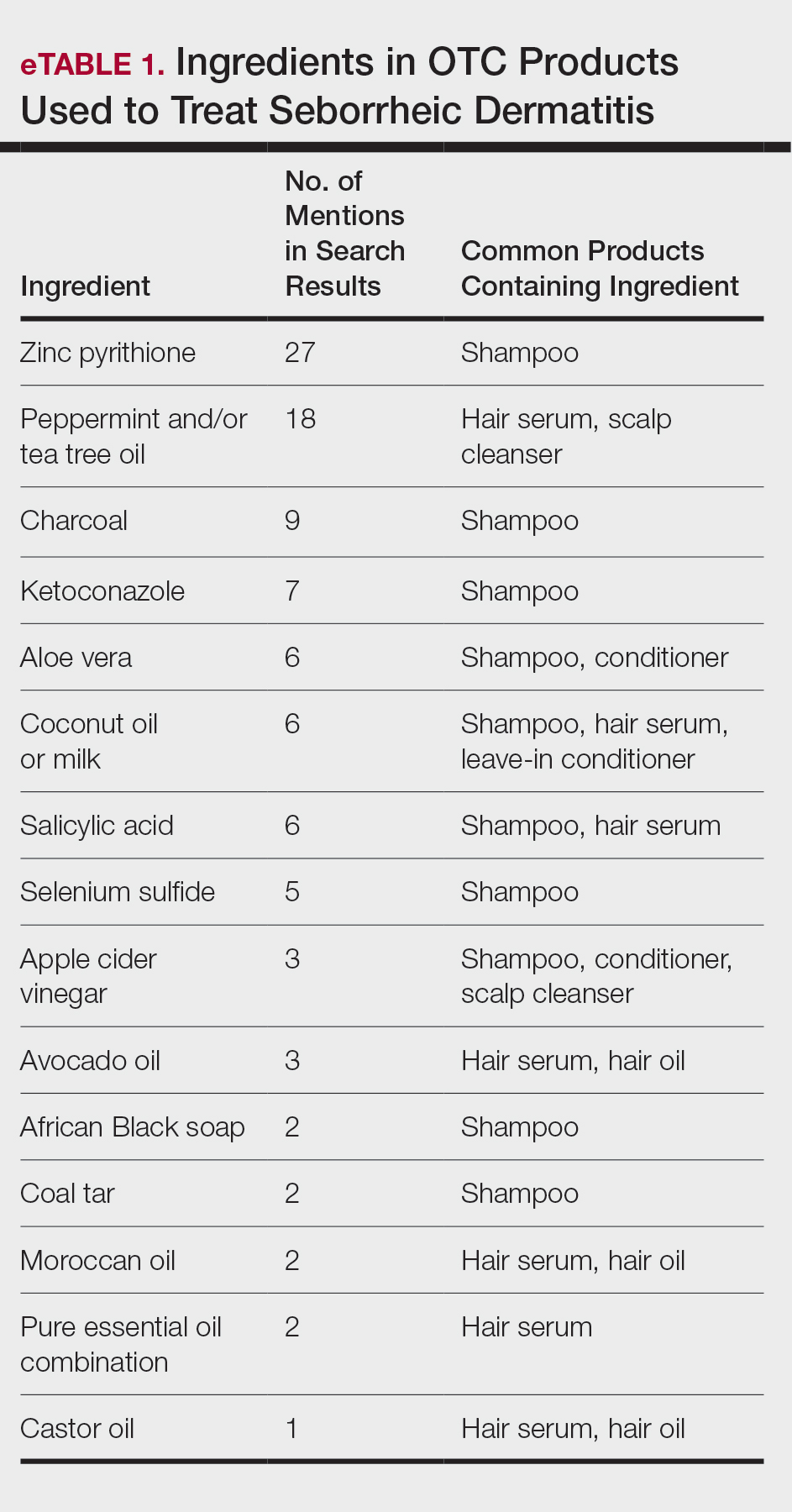

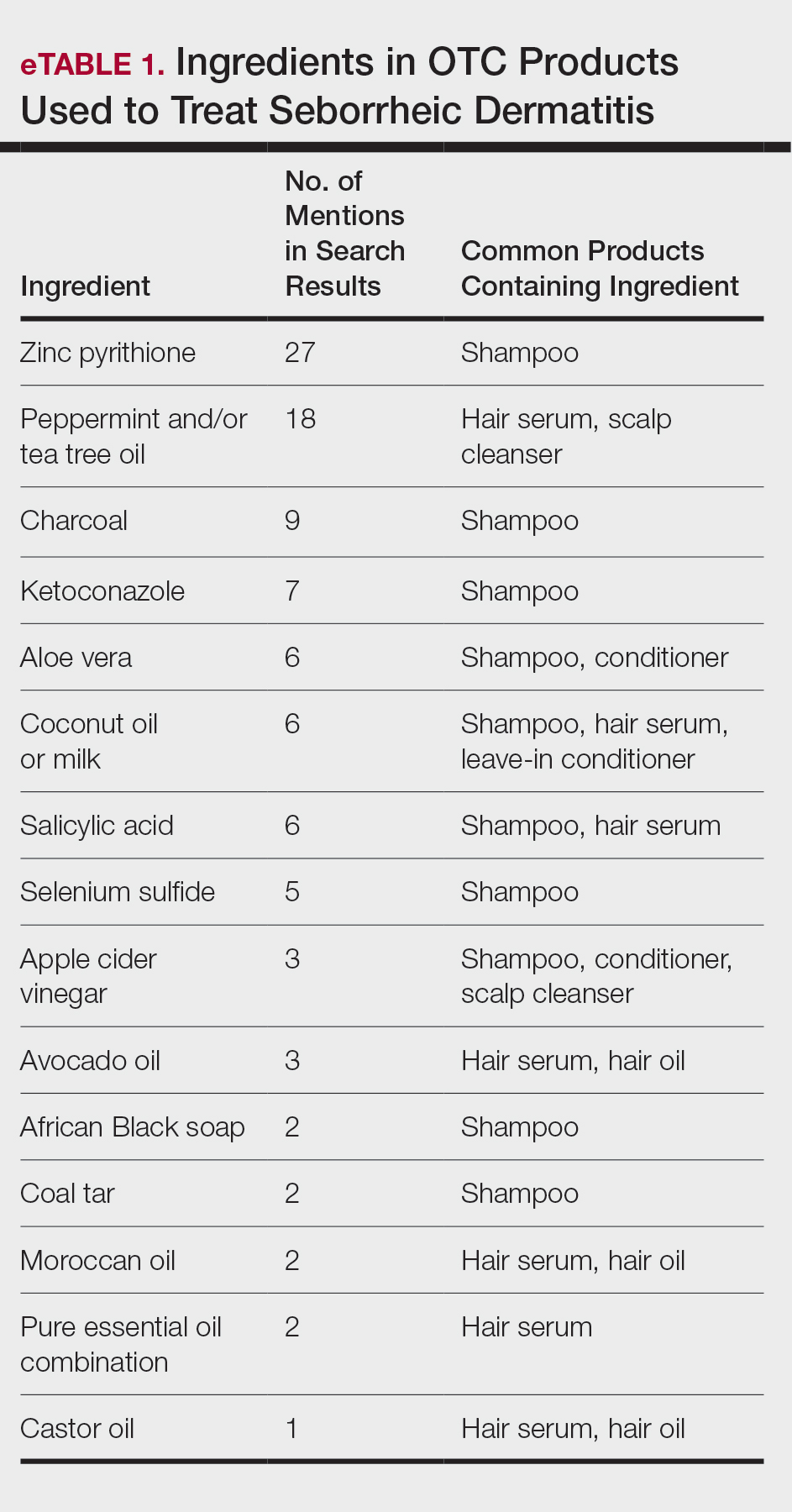

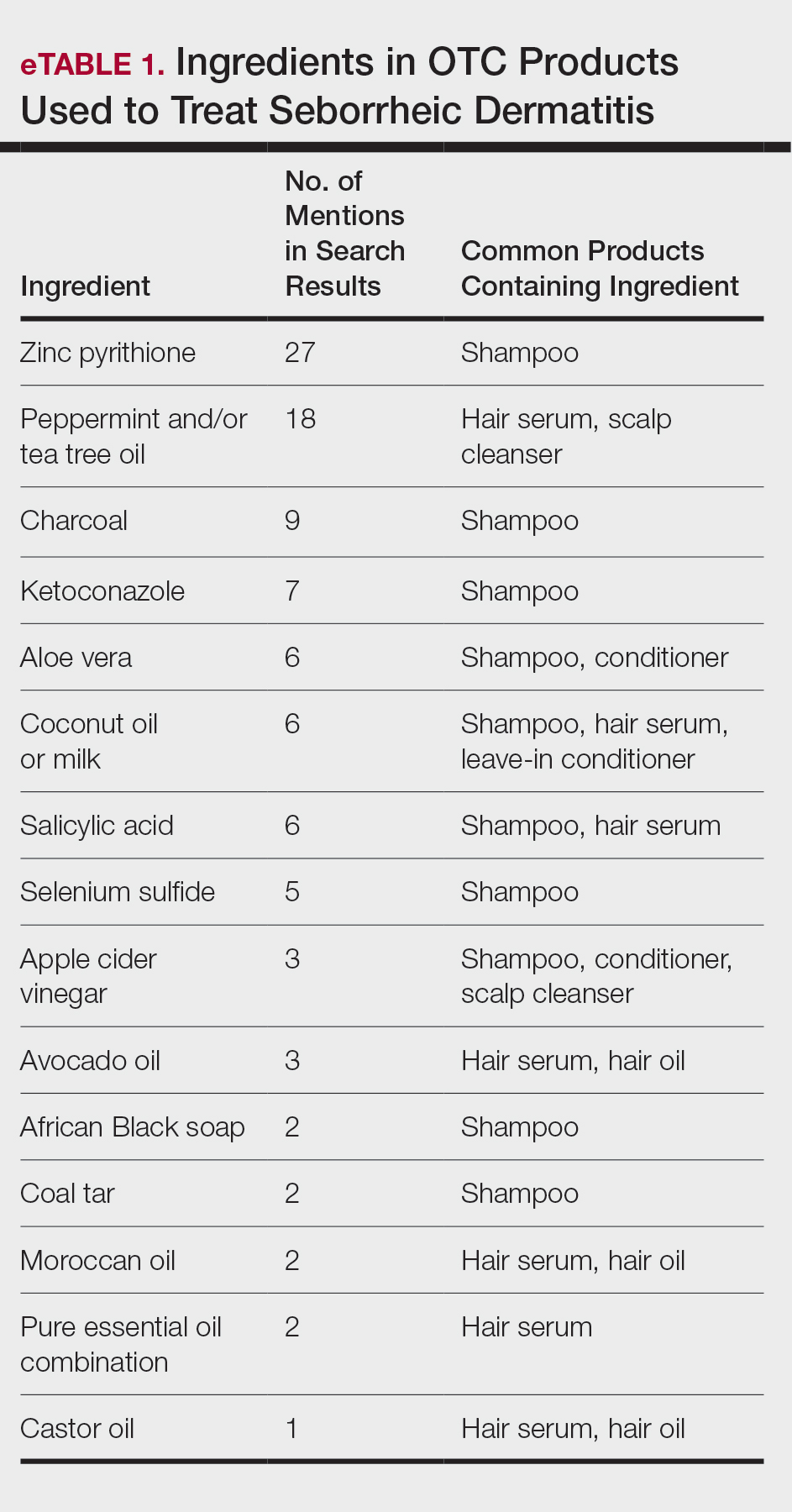

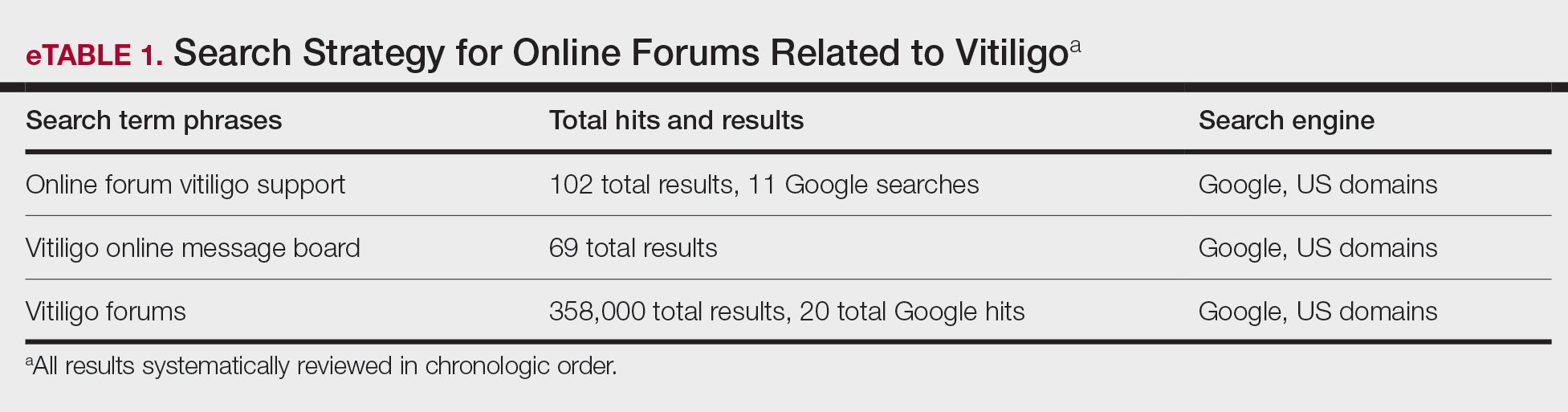

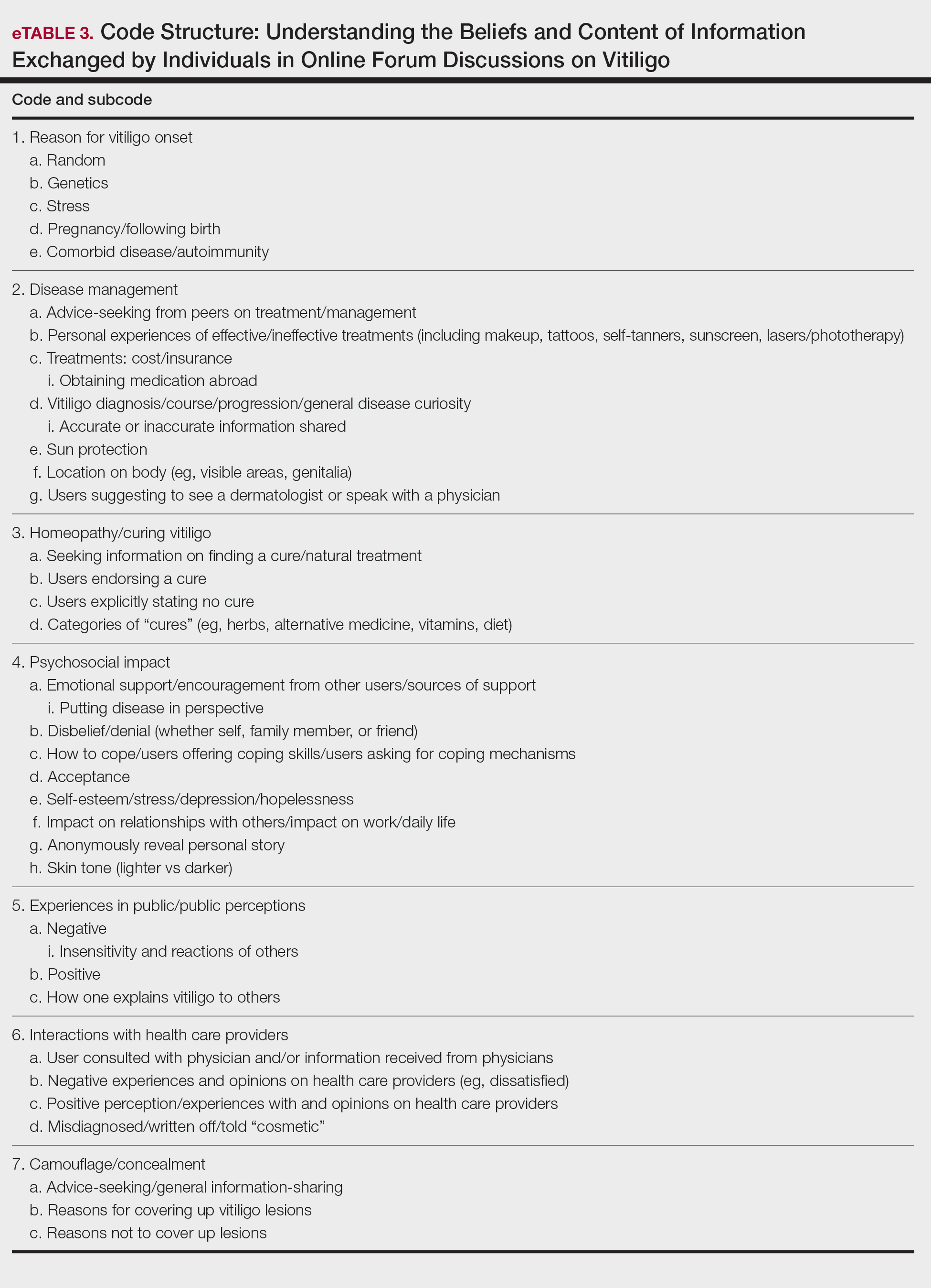

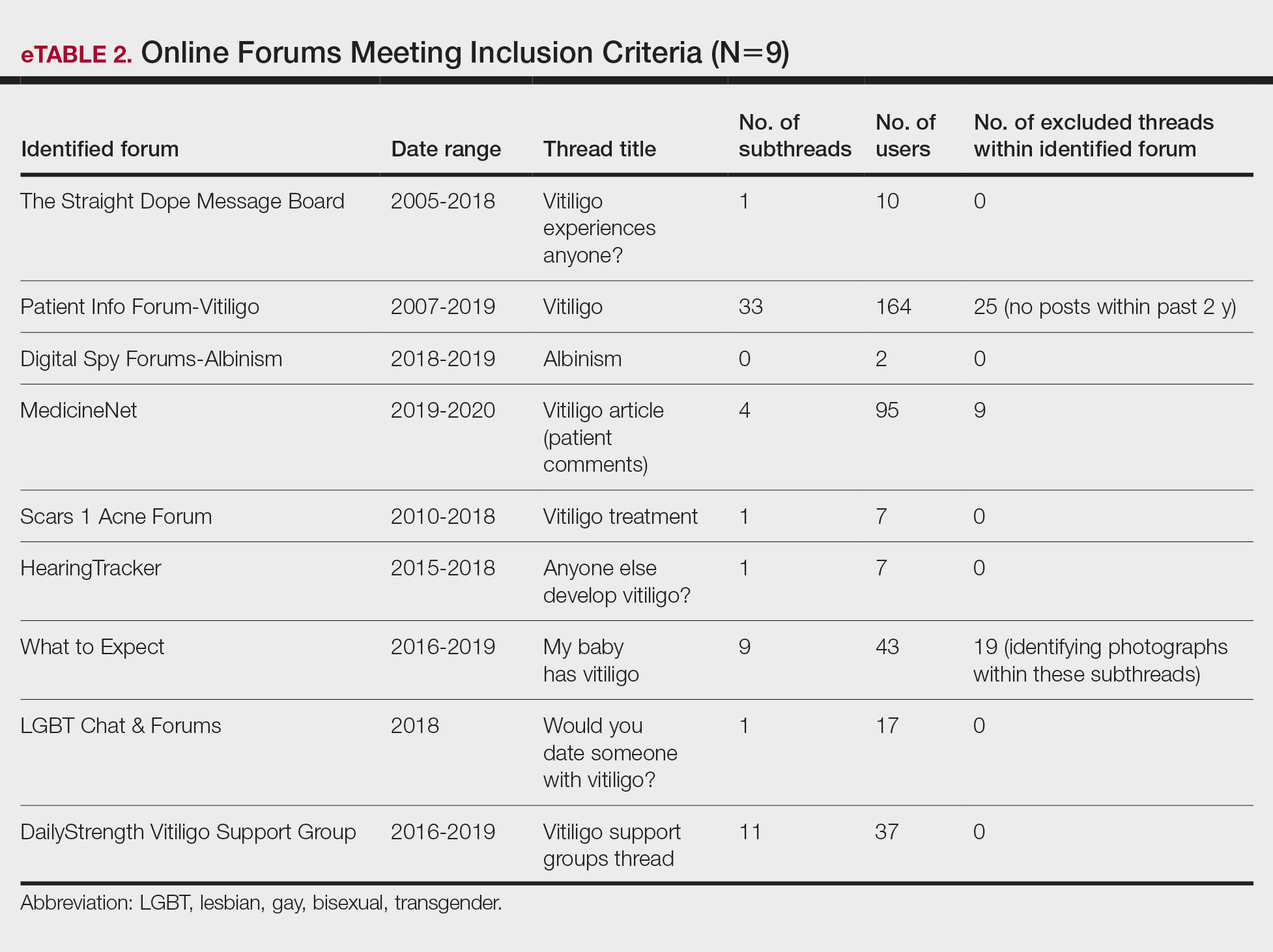

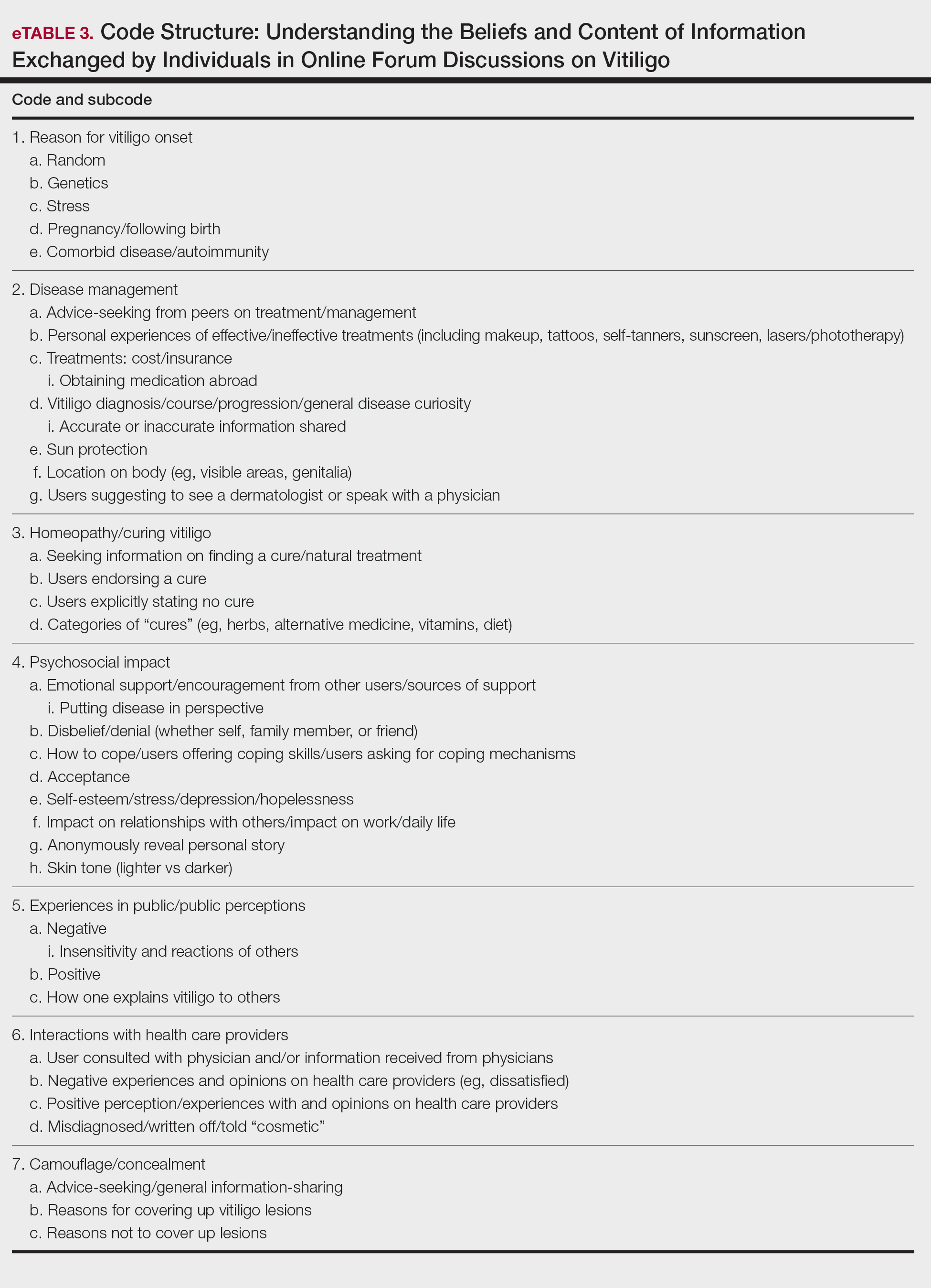

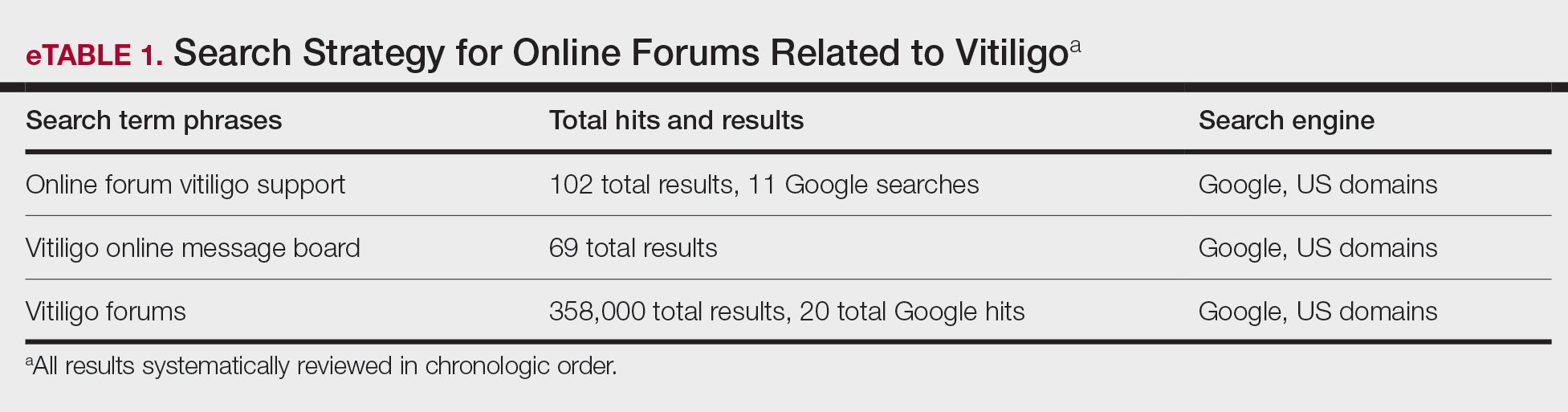

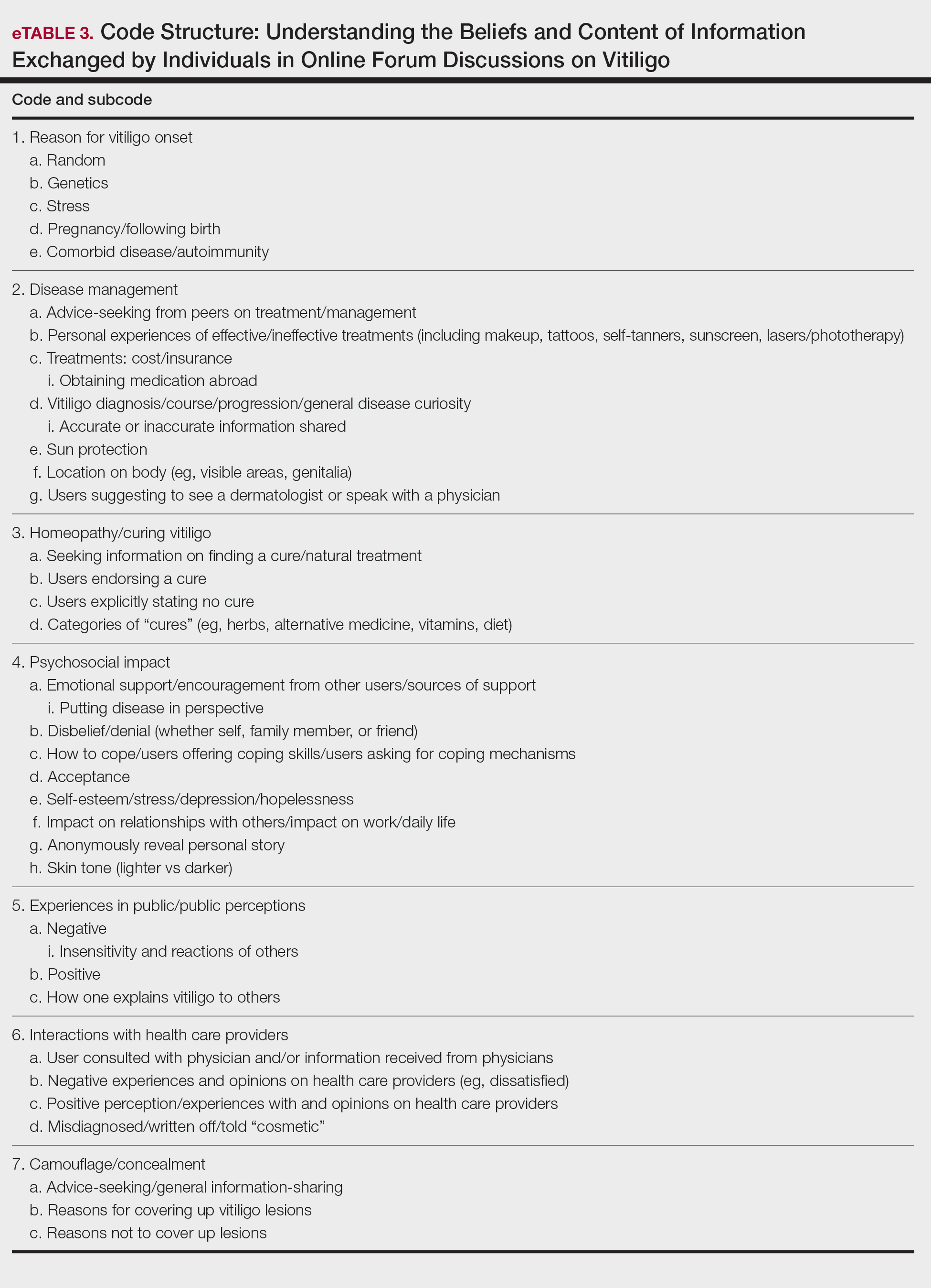

We identified 16 unique consumer websites with product or ingredient recommendations for SD in Black patients, none of which were provided by authors with a medical or scientific background; however, 4 (25%) websites included insights from board-certified dermatologists. A total of 16 ingredients were recommended, 15 (94%) of which were mentioned at least twice in our search results (eTable 1).

Overall, we noticed that ingredients labeled as natural or organic were common in over-the-counter (OTC) products, and ingredients such as sulfates and parabens were avoided. Common OTC ingredients for antidandruff and anti-itch shampoos and conditioners include zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, coal tar, salicylic acid, and citric acid. Additionally, coconut oil, tea tree oil, apple cider vinegar, and charcoal are common natural alternatives used to address SD symptoms.

Our review of the literature yielded limited recommendations tailored specifically to Black patients with SD. Of 108 abstracts, articles, or textbook chapters providing treatment recommendations for SD, 6 (6%) specifically discussed treatments for Black patients. All articles were written by authors with medical or scientific backgrounds. Of the treatment options discussed, topical antifungals generally were considered first-line for SD in all patients, with ketoconazole shampoo being a common first choice.4,5

Comment

Our study indicated that many consumer websites recommend unstudied nonmedical treatments for SD. Zinc pyrithione was one of the most commonly mentioned ingredients in OTC products to treat SD targeted toward Black patients, as its properties have contributed to ease of hair combing and less frizz.6 Zinc pyrithione has antifungal properties that reduce the proliferation of Malassezia furfur as well as anti-inflammatory properties that reduce irritation, pruritus, and erythema in areas affected by SD.7 Tea tree and peppermint oils also were commonly mentioned; the theory is that these oils mitigate SD by reducing yeast growth and soothing inflammation through antioxidant activity.8,9 Coal tar also is used due to its keratoplastic properties, which slow the growth of skin cells and ultimately reduce scaling and dryness.10 Yeast thrives in basic pH conditions; apple cider vinegar is used as an ingredient in OTC products for SD because its acidic pH creates a less favorable environment for yeast to grow.11 Although many of the ingredients found in OTC products we identified have not yet been studied, they have properties that theoretically would be helpful in treating SD.

Our review of the medical literature revealed that while there are treatments that are effective for SD, the recommended use may not consider the cultural differences that exist for Black patients. For instance, reports in the literature regarding ketoconazole shampoo revealed that ketoconazole increases the risk for hair shaft dryness, damage, and subsequent breakage, especially in Black women who also may be using heat styling or chemical relaxers.5 As a result, ketoconazole should be used with caution in Black women, with an emphasis on direct application to the scalp rather than the hair shafts.12 Additional options reported for Black patients include ciclopirox olamine and zinc pyrithione, which may have fewer risks.13

When prescribing medicated shampoos, traditional instructions regarding frequency of use to control symptoms of SD range from 2 to 3 times weekly to daily for a specified period of time determined by the dermatologist.14 However, frequency of hair washing varies greatly among Black patients, sometimes occurring only once monthly. The frequency also may change based on styling techniques (eg, braids, weaves, and wigs).15 Based on previous research underscoring the tendency for Black patients to use medicated shampoos less frequently than White patients, it is important for clinicians to understand that these cultural practices can undermine the effectiveness when medicated shampoos are prescribed for SD.16

Additionally, topical corticosteroids often are used in conjunction with antifungals to help decrease inflammation of the scalp.17 An option reported for Black patients is topical fluocinolone 0.01%; however, package instructions state to apply topically to the scalp nightly and wash the hair thoroughly each morning, which may not be feasible for Black patients based on previously mentioned differences in hair-washing techniques. An alternative option may be to apply the medication 3 to 4 times per week, washing the hair weekly rather than daily.18 Fluocinolone can be used as an ointment, solution, oil, or cream.19,20 When comparing treatment vehicles for SD, a study conducted by Chappell et al21 found that Black patients preferred using ointment or oil vehicles; White patients preferred foams and sprays, which may not be suitable for Afro hair patterns. As such, using less-drying modalities may increase compliance and treatment success in Black patients. For patients who may have involvement on the hairline, face, or ears along with hypopigmentation (which is a common skin concern associated with SD), calcineurin inhibitors can be used until resolution occurs.5,22 High et al15 found that twice-daily use of pimecrolimus rapidly normalized skin pigmentation during the first 2 weeks of use. Overall, personalization of treatment may not only avoid adverse effects but also ensure patient compliance, with the overall goal of treating to reduce yeast activity, pruritus, and dyschromia.22

Interestingly, after the website searches were completed for this study, the US Food and Drug Administration approved topical roflumilast foam for SD. In a phase III trial of 457 total patients, 36 Black patients were included.23 It was determined that 79.5% of patients overall throughout the trial achieved Investigator Global Assessment success (score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]) plus ≥2-point improvement from baseline (on a scale of 0 [clear] to 4 [severe]) at weeks 2, 4, and 8. Although there currently are no long-term studies, roflumilast may be a promising option for Black patients with SD.23

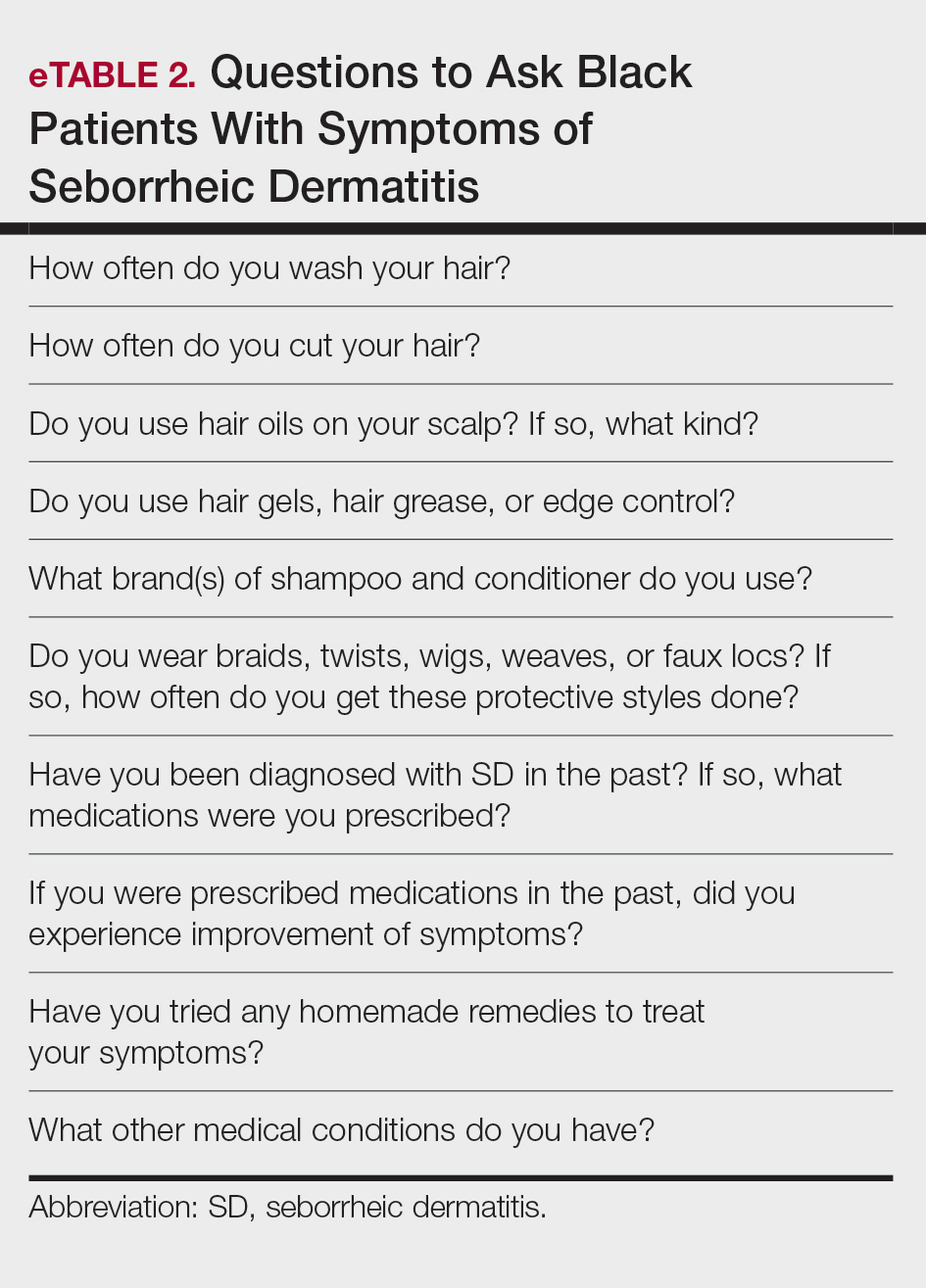

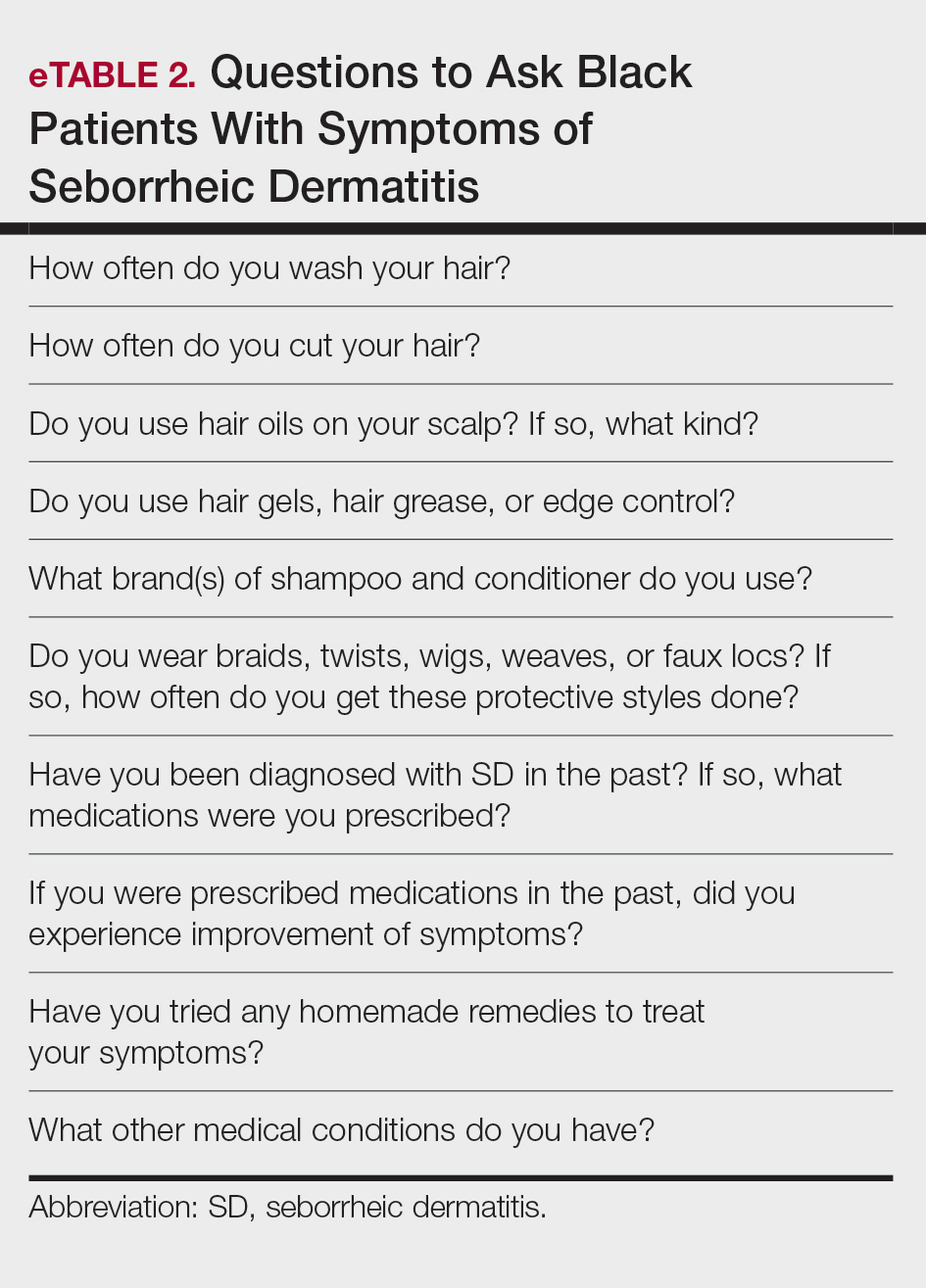

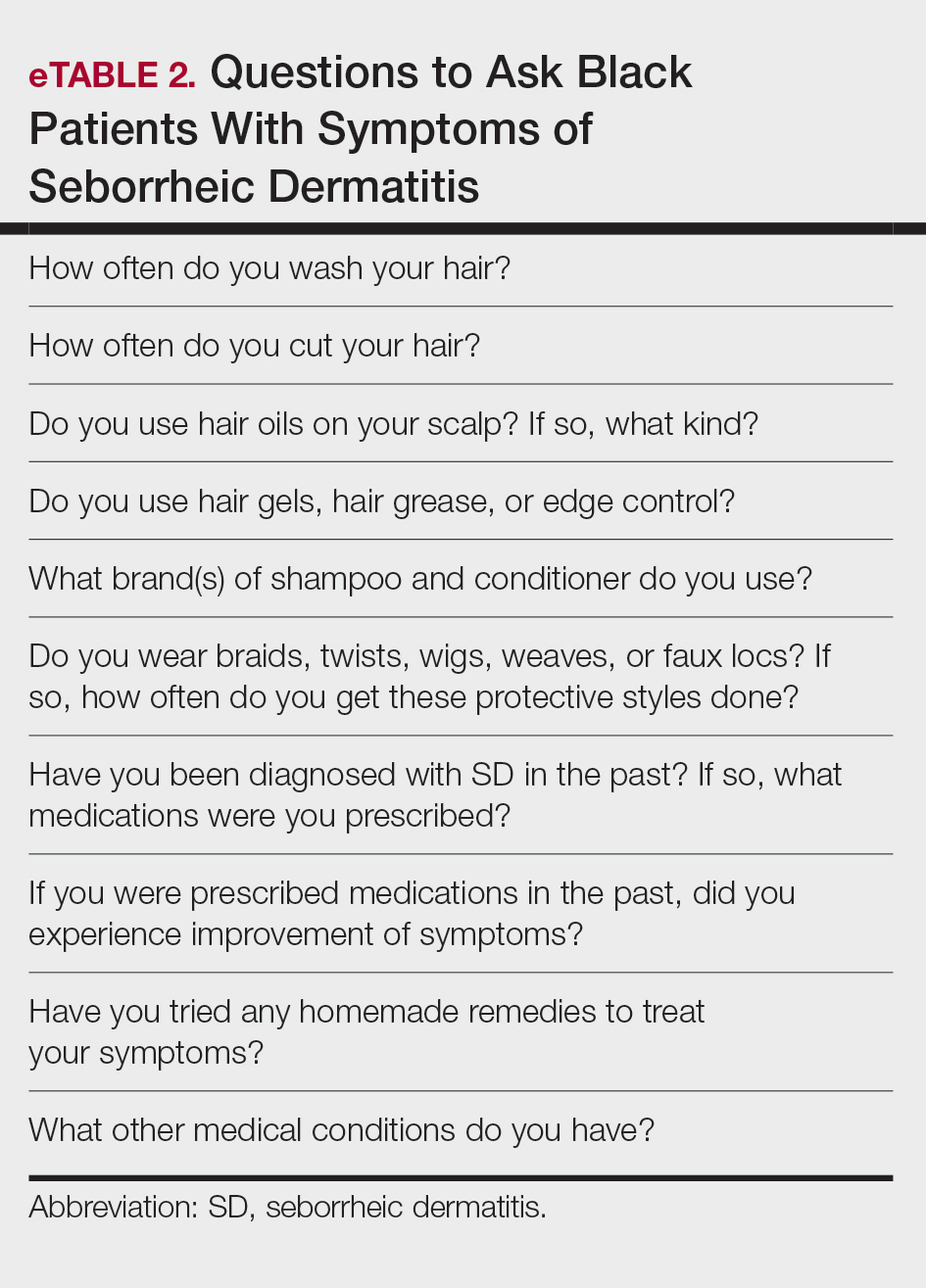

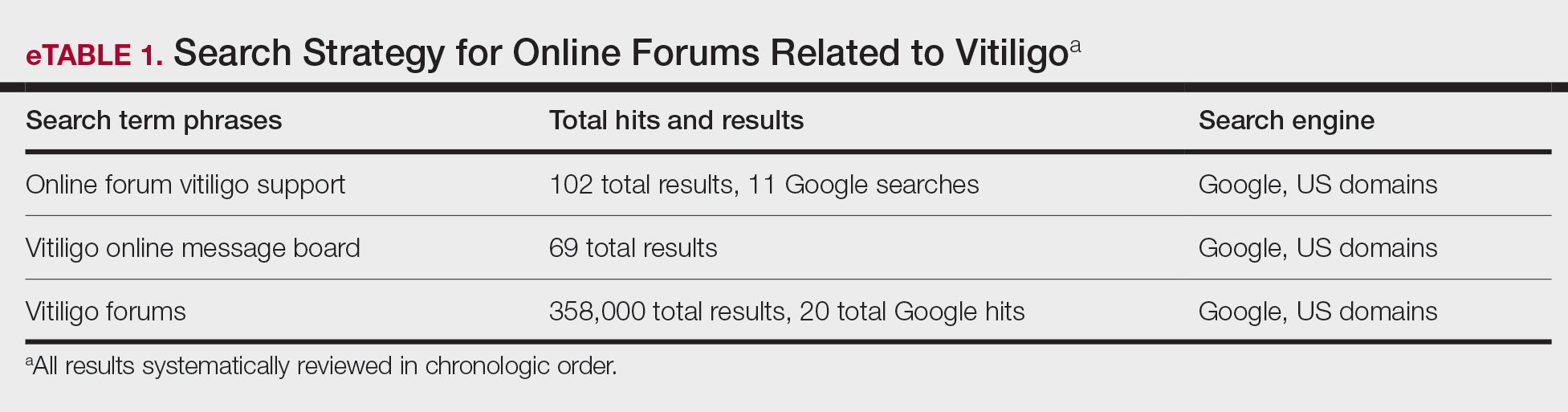

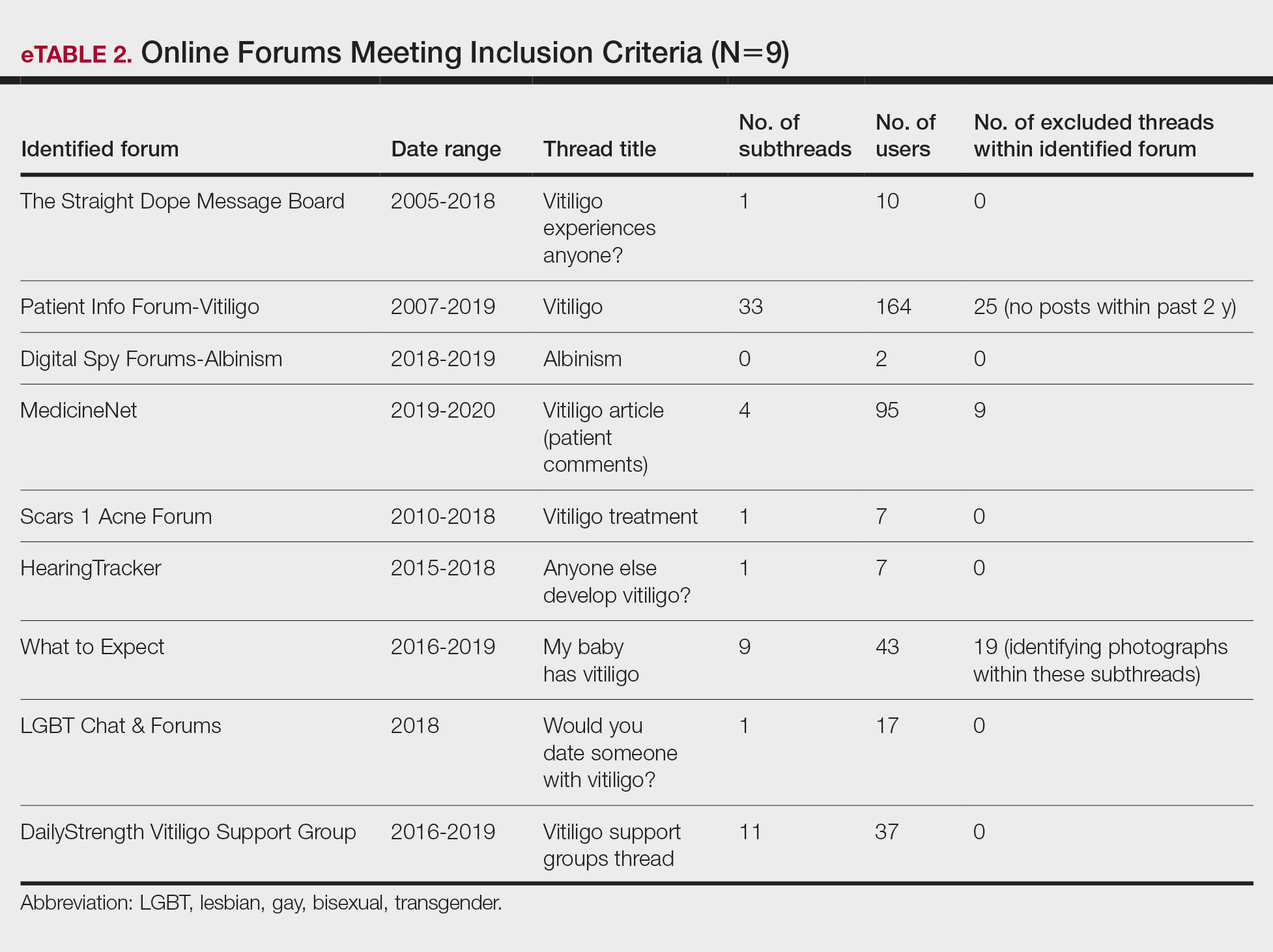

Aside from developing an individualized treatment approach for Black patients with SD, it is important to ask targeted questions during the clinical encounter to identify factors that may be exacerbating symptoms, especially due to the wide range of hair care practices used by the Black community (eTable 2). Asking targeted questions is especially important, as prior studies have shown that extensions, hair relaxers, and particular hair products can irritate the scalp and increase the likelihood of developing SD.21,24 Rucker Wright et al25 evaluated different hair care practices among young Black females and their association with the development of SD. The authors found that using hair extensions (either braided, cornrowed, or ponytails), chemical relaxers, and hair oils every 2 weeks was associated with SD. The study also found that SD rates were roughly 20% higher among Black girls with extensions compared to Black girls without extensions, regardless of how frequently hair was washed.25

Many Black patients grease the scalp with oils that are beneficial for lubrication and reduction of abrasive damage caused by grooming; however, they also may increase incidence of SD.26 Tight curls worn by Black patients also can impede sebum from traveling down the hair shaft, leading to oil buildup on the scalp. This is the ideal environment for increased Malassezia density and higher risk for SD development.27 To balance the beneficial effects of hair oils with the increased susceptibility for SD, providers should emphasize applying these oils only to distal hair shafts, which are more likely to be damaged, and avoiding application to the scalp.19

Conclusion

Given its long-term relapsing and remitting nature, SD can be distressing for Black patients, many of whom may seek additional treatment options aside from those recommended by health care professionals. In order to better educate patients, it is important for dermatologists to know not only the common ingredients that may be present in OTC products but also the thought process behind why patients use them. Additionally, prescription treatments for Black patients with SD may require nuanced alterations to the product instructions that may prevent health disparities and provide culturally sensitive care. Overall, the literature regarding treatment for Black patients with SD is limited, and more high-quality studies are needed.

- Tucker D, Masood S. Seborrheic dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551707/

- Borda LJ, Wikramanayake TC. Seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff: a comprehensive review. J Clin Investig Dermatol. 2015;3:10.13188 /2373-1044.1000019.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Seborrheic dermatitis by the numbers. American Academy of Dermatology Skin Disease Briefs. Updated May 5, 2018. Accessed November 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/asset/49w949DPcF8RSJYIRHfDon

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:158-169.

- Draelos ZD, Kenneally DC, Hodges LT, et al. A comparison of hair quality and cosmetic acceptance following the use of two anti-dandruff shampoos. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:201-214.

- Barak-Shinar D, Green LJ. Scalp seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff therapy using a herbal and zinc pyrithione-based therapy of shampoo and scalp lotion. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:26-31.

- Satchell AC, Saurajen A, Bell C, et al. Treatment of dandruff with 5% tea tree oil shampoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:852-855.

- Herro E, Jacob SE. Mentha piperita (peppermint). Dermatitis. 2010;21:327-329.

- Sanfilippo A, English JC. An overview of medicated shampoos used in dandruff treatment. Pharm Ther. 2006;31:396-400.

- Arun PVPS, Vineetha Y, Waheed M, et al. Quantification of the minimum amount of lemon juice and apple cider vinegar required for the growth inhibition of dandruff causing fungi Malassezia furfur. Int J Sci Res in Biological Sciences. 2019;6:144-147.

- Gao HY, Li Wan Po A. Topical formulations of fluocinolone acetonide. Are creams, gels and ointments bioequivalent and does dilution affect activity? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46:71-75.

- Pauporte M, Maibach H, Lowe N, et al. Fluocinolone acetonide topical oil for scalp psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:360-364.

- Elgash M, Dlova N, Ogunleye T, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis in skin of color: clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:24-27.

- High WA, Pandya AG. Pilot trial of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in African American adults with associated hypopigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1083-1088.

- Hollins LC, Butt M, Hong J, et al. Research in brief: survey of hair care practices in various ethnic and racial pediatric populations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:494-496.

- Halder RM, Roberts CI, Nootheti PK. Cutaneous diseases in the black races. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:679-687, ix.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Friedmann DP, Mishra V, Batty T. Progressive facial papules in an African- American patient: an atypical presentation of seborrheic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:44-45.

- Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:185-190.

- Chappell J, Mattox A, Simonetta C, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp in populations practicing less frequent hair washing: ketoconazole 2% foam versus ketoconazole 2% shampoo. three-year data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB54.

- Dadzie OE, Salam A. The hair grooming practices of women of African descent in London, United Kingdom: findings of a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1021-1024.

- Blauvelt A, Draelos ZD, Stein Gold L, et al. Roflumilast foam 0.3% for adolescent and adult patients with seborrheic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, vehicle-controlled, phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:986-993.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Rucker Wright D, Gathers R, Kapke A, et al. Hair care practices and their association with scalp and hair disorders in African American girls. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:253-262.

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319.

- Mayo T, Dinkins J, Elewski B. Hair oils may worsen seborrheic dermatitis in Black patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:151-152.

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that predominantly affects areas with high concentrations of sebaceous glands such as the scalp and face. Up to 5% of the worldwide population is affected by SD each year, causing a major burden of disease for patients and the health care system.1 In 2023, the cost of medical treatment for SD in the United States was $300 million, with outpatient office visits alone costing $58 million and prescription drugs costing $109 million. Indirect costs of disease (eg, lost workdays) account for another $51 million.1 Since SD frequently manifests on the face, it tends to have negative effects on the patient’s quality of life, resulting in psychological distress and low self-esteem.2

Patients with SD may describe symptoms of excessive dandruff and itching along with hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin; Black patients tend to present with the classic manifestations: a combination of scaling, flaking, and erythematous patches on the scalp, ears, and face, particularly around the eyebrows, eyelids, and nose. With SD being the second most common diagnosis in Black patients who seek care from a dermatologist, it is important to have effective treatment approaches for SD in this patient population.3

In this study, we aimed to evaluate medical and nonmedical treatment options for SD in Black patients by identifying common practices and products mentioned on consumer websites and in the medical literature.

Methods

A Google search was conducted during 2 time periods (September 2022—October 2022 and March 2023—April 2023) using the terms products for itchy scalp in Black patients, products for dandruff in Black patients, itchy scalp in Black women, itchy scalp in Black men, treatment for scalp itch in Black patients, and dry scalp in Black hair. Products that were recommended by at least 1 website on the first page of search results were included in our list of products, and the ingredients were reviewed by the authors. We excluded individual retailer websites as well as those that did not provide specific recommendations on products or ingredients to use when treating SD. To ensure reliability and standardization, we did not review products that were suggested by ads in the shopping section on the first page of search results.

We also evaluated medical treatments used for SD in dermatology literature. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms seborrheic dermatitis treatment for Black patients, treatment for dandruff for Black patients, and seborrheic dermatitis and skin of color was conducted. We excluded articles that did not address treatment options for SD, were specific to treating SD in patient populations with specific comorbidities being studied, discussed SD in animals, or were published prior to 1990.

Results

We identified 16 unique consumer websites with product or ingredient recommendations for SD in Black patients, none of which were provided by authors with a medical or scientific background; however, 4 (25%) websites included insights from board-certified dermatologists. A total of 16 ingredients were recommended, 15 (94%) of which were mentioned at least twice in our search results (eTable 1).

Overall, we noticed that ingredients labeled as natural or organic were common in over-the-counter (OTC) products, and ingredients such as sulfates and parabens were avoided. Common OTC ingredients for antidandruff and anti-itch shampoos and conditioners include zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, coal tar, salicylic acid, and citric acid. Additionally, coconut oil, tea tree oil, apple cider vinegar, and charcoal are common natural alternatives used to address SD symptoms.

Our review of the literature yielded limited recommendations tailored specifically to Black patients with SD. Of 108 abstracts, articles, or textbook chapters providing treatment recommendations for SD, 6 (6%) specifically discussed treatments for Black patients. All articles were written by authors with medical or scientific backgrounds. Of the treatment options discussed, topical antifungals generally were considered first-line for SD in all patients, with ketoconazole shampoo being a common first choice.4,5

Comment

Our study indicated that many consumer websites recommend unstudied nonmedical treatments for SD. Zinc pyrithione was one of the most commonly mentioned ingredients in OTC products to treat SD targeted toward Black patients, as its properties have contributed to ease of hair combing and less frizz.6 Zinc pyrithione has antifungal properties that reduce the proliferation of Malassezia furfur as well as anti-inflammatory properties that reduce irritation, pruritus, and erythema in areas affected by SD.7 Tea tree and peppermint oils also were commonly mentioned; the theory is that these oils mitigate SD by reducing yeast growth and soothing inflammation through antioxidant activity.8,9 Coal tar also is used due to its keratoplastic properties, which slow the growth of skin cells and ultimately reduce scaling and dryness.10 Yeast thrives in basic pH conditions; apple cider vinegar is used as an ingredient in OTC products for SD because its acidic pH creates a less favorable environment for yeast to grow.11 Although many of the ingredients found in OTC products we identified have not yet been studied, they have properties that theoretically would be helpful in treating SD.

Our review of the medical literature revealed that while there are treatments that are effective for SD, the recommended use may not consider the cultural differences that exist for Black patients. For instance, reports in the literature regarding ketoconazole shampoo revealed that ketoconazole increases the risk for hair shaft dryness, damage, and subsequent breakage, especially in Black women who also may be using heat styling or chemical relaxers.5 As a result, ketoconazole should be used with caution in Black women, with an emphasis on direct application to the scalp rather than the hair shafts.12 Additional options reported for Black patients include ciclopirox olamine and zinc pyrithione, which may have fewer risks.13

When prescribing medicated shampoos, traditional instructions regarding frequency of use to control symptoms of SD range from 2 to 3 times weekly to daily for a specified period of time determined by the dermatologist.14 However, frequency of hair washing varies greatly among Black patients, sometimes occurring only once monthly. The frequency also may change based on styling techniques (eg, braids, weaves, and wigs).15 Based on previous research underscoring the tendency for Black patients to use medicated shampoos less frequently than White patients, it is important for clinicians to understand that these cultural practices can undermine the effectiveness when medicated shampoos are prescribed for SD.16

Additionally, topical corticosteroids often are used in conjunction with antifungals to help decrease inflammation of the scalp.17 An option reported for Black patients is topical fluocinolone 0.01%; however, package instructions state to apply topically to the scalp nightly and wash the hair thoroughly each morning, which may not be feasible for Black patients based on previously mentioned differences in hair-washing techniques. An alternative option may be to apply the medication 3 to 4 times per week, washing the hair weekly rather than daily.18 Fluocinolone can be used as an ointment, solution, oil, or cream.19,20 When comparing treatment vehicles for SD, a study conducted by Chappell et al21 found that Black patients preferred using ointment or oil vehicles; White patients preferred foams and sprays, which may not be suitable for Afro hair patterns. As such, using less-drying modalities may increase compliance and treatment success in Black patients. For patients who may have involvement on the hairline, face, or ears along with hypopigmentation (which is a common skin concern associated with SD), calcineurin inhibitors can be used until resolution occurs.5,22 High et al15 found that twice-daily use of pimecrolimus rapidly normalized skin pigmentation during the first 2 weeks of use. Overall, personalization of treatment may not only avoid adverse effects but also ensure patient compliance, with the overall goal of treating to reduce yeast activity, pruritus, and dyschromia.22

Interestingly, after the website searches were completed for this study, the US Food and Drug Administration approved topical roflumilast foam for SD. In a phase III trial of 457 total patients, 36 Black patients were included.23 It was determined that 79.5% of patients overall throughout the trial achieved Investigator Global Assessment success (score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]) plus ≥2-point improvement from baseline (on a scale of 0 [clear] to 4 [severe]) at weeks 2, 4, and 8. Although there currently are no long-term studies, roflumilast may be a promising option for Black patients with SD.23

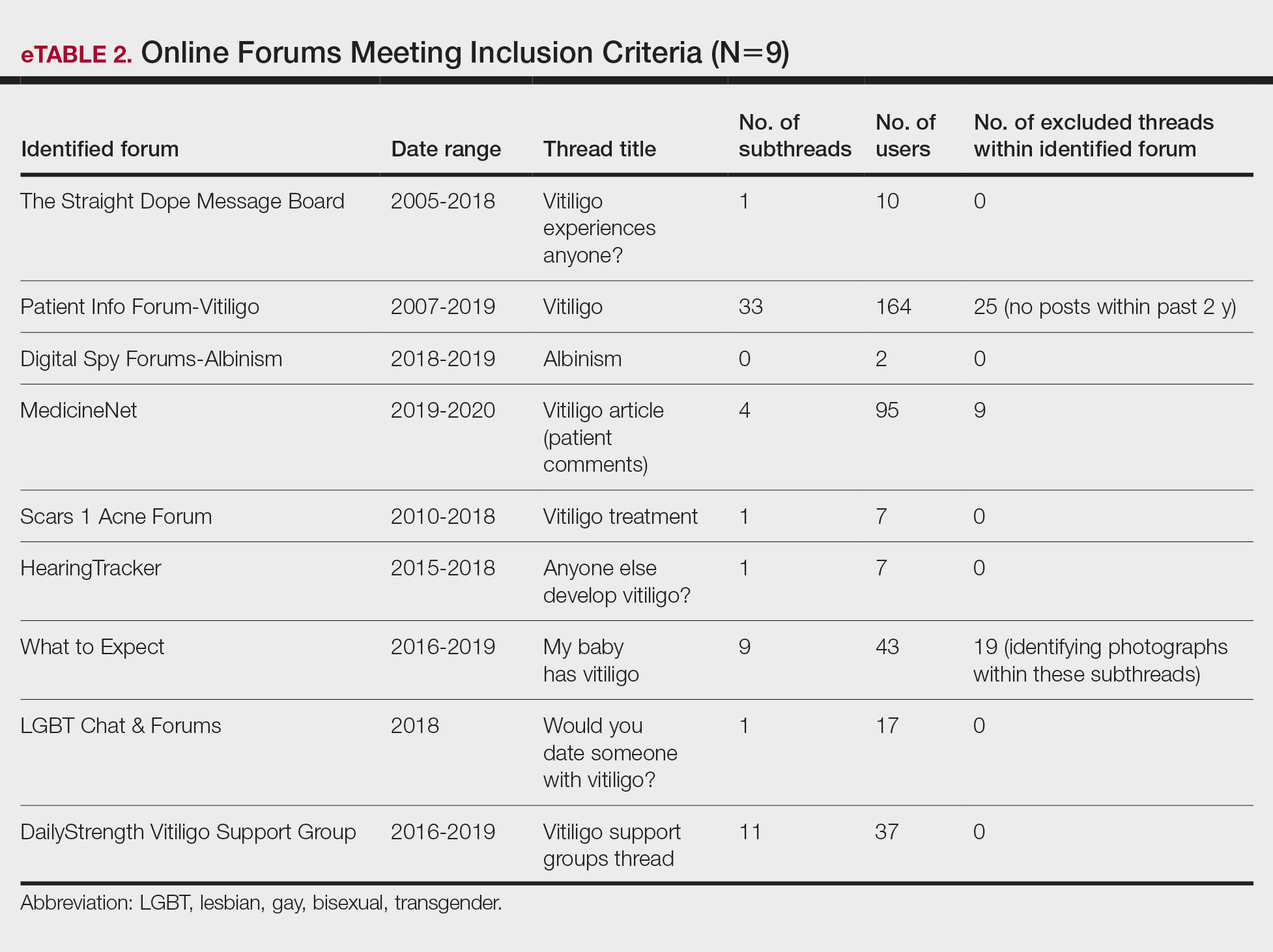

Aside from developing an individualized treatment approach for Black patients with SD, it is important to ask targeted questions during the clinical encounter to identify factors that may be exacerbating symptoms, especially due to the wide range of hair care practices used by the Black community (eTable 2). Asking targeted questions is especially important, as prior studies have shown that extensions, hair relaxers, and particular hair products can irritate the scalp and increase the likelihood of developing SD.21,24 Rucker Wright et al25 evaluated different hair care practices among young Black females and their association with the development of SD. The authors found that using hair extensions (either braided, cornrowed, or ponytails), chemical relaxers, and hair oils every 2 weeks was associated with SD. The study also found that SD rates were roughly 20% higher among Black girls with extensions compared to Black girls without extensions, regardless of how frequently hair was washed.25

Many Black patients grease the scalp with oils that are beneficial for lubrication and reduction of abrasive damage caused by grooming; however, they also may increase incidence of SD.26 Tight curls worn by Black patients also can impede sebum from traveling down the hair shaft, leading to oil buildup on the scalp. This is the ideal environment for increased Malassezia density and higher risk for SD development.27 To balance the beneficial effects of hair oils with the increased susceptibility for SD, providers should emphasize applying these oils only to distal hair shafts, which are more likely to be damaged, and avoiding application to the scalp.19

Conclusion

Given its long-term relapsing and remitting nature, SD can be distressing for Black patients, many of whom may seek additional treatment options aside from those recommended by health care professionals. In order to better educate patients, it is important for dermatologists to know not only the common ingredients that may be present in OTC products but also the thought process behind why patients use them. Additionally, prescription treatments for Black patients with SD may require nuanced alterations to the product instructions that may prevent health disparities and provide culturally sensitive care. Overall, the literature regarding treatment for Black patients with SD is limited, and more high-quality studies are needed.

Seborrheic dermatitis (SD) is a common chronic inflammatory skin condition that predominantly affects areas with high concentrations of sebaceous glands such as the scalp and face. Up to 5% of the worldwide population is affected by SD each year, causing a major burden of disease for patients and the health care system.1 In 2023, the cost of medical treatment for SD in the United States was $300 million, with outpatient office visits alone costing $58 million and prescription drugs costing $109 million. Indirect costs of disease (eg, lost workdays) account for another $51 million.1 Since SD frequently manifests on the face, it tends to have negative effects on the patient’s quality of life, resulting in psychological distress and low self-esteem.2

Patients with SD may describe symptoms of excessive dandruff and itching along with hyperpigmentation or hypopigmentation of the skin; Black patients tend to present with the classic manifestations: a combination of scaling, flaking, and erythematous patches on the scalp, ears, and face, particularly around the eyebrows, eyelids, and nose. With SD being the second most common diagnosis in Black patients who seek care from a dermatologist, it is important to have effective treatment approaches for SD in this patient population.3

In this study, we aimed to evaluate medical and nonmedical treatment options for SD in Black patients by identifying common practices and products mentioned on consumer websites and in the medical literature.

Methods

A Google search was conducted during 2 time periods (September 2022—October 2022 and March 2023—April 2023) using the terms products for itchy scalp in Black patients, products for dandruff in Black patients, itchy scalp in Black women, itchy scalp in Black men, treatment for scalp itch in Black patients, and dry scalp in Black hair. Products that were recommended by at least 1 website on the first page of search results were included in our list of products, and the ingredients were reviewed by the authors. We excluded individual retailer websites as well as those that did not provide specific recommendations on products or ingredients to use when treating SD. To ensure reliability and standardization, we did not review products that were suggested by ads in the shopping section on the first page of search results.

We also evaluated medical treatments used for SD in dermatology literature. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms seborrheic dermatitis treatment for Black patients, treatment for dandruff for Black patients, and seborrheic dermatitis and skin of color was conducted. We excluded articles that did not address treatment options for SD, were specific to treating SD in patient populations with specific comorbidities being studied, discussed SD in animals, or were published prior to 1990.

Results

We identified 16 unique consumer websites with product or ingredient recommendations for SD in Black patients, none of which were provided by authors with a medical or scientific background; however, 4 (25%) websites included insights from board-certified dermatologists. A total of 16 ingredients were recommended, 15 (94%) of which were mentioned at least twice in our search results (eTable 1).

Overall, we noticed that ingredients labeled as natural or organic were common in over-the-counter (OTC) products, and ingredients such as sulfates and parabens were avoided. Common OTC ingredients for antidandruff and anti-itch shampoos and conditioners include zinc pyrithione, selenium sulfide, coal tar, salicylic acid, and citric acid. Additionally, coconut oil, tea tree oil, apple cider vinegar, and charcoal are common natural alternatives used to address SD symptoms.

Our review of the literature yielded limited recommendations tailored specifically to Black patients with SD. Of 108 abstracts, articles, or textbook chapters providing treatment recommendations for SD, 6 (6%) specifically discussed treatments for Black patients. All articles were written by authors with medical or scientific backgrounds. Of the treatment options discussed, topical antifungals generally were considered first-line for SD in all patients, with ketoconazole shampoo being a common first choice.4,5

Comment

Our study indicated that many consumer websites recommend unstudied nonmedical treatments for SD. Zinc pyrithione was one of the most commonly mentioned ingredients in OTC products to treat SD targeted toward Black patients, as its properties have contributed to ease of hair combing and less frizz.6 Zinc pyrithione has antifungal properties that reduce the proliferation of Malassezia furfur as well as anti-inflammatory properties that reduce irritation, pruritus, and erythema in areas affected by SD.7 Tea tree and peppermint oils also were commonly mentioned; the theory is that these oils mitigate SD by reducing yeast growth and soothing inflammation through antioxidant activity.8,9 Coal tar also is used due to its keratoplastic properties, which slow the growth of skin cells and ultimately reduce scaling and dryness.10 Yeast thrives in basic pH conditions; apple cider vinegar is used as an ingredient in OTC products for SD because its acidic pH creates a less favorable environment for yeast to grow.11 Although many of the ingredients found in OTC products we identified have not yet been studied, they have properties that theoretically would be helpful in treating SD.

Our review of the medical literature revealed that while there are treatments that are effective for SD, the recommended use may not consider the cultural differences that exist for Black patients. For instance, reports in the literature regarding ketoconazole shampoo revealed that ketoconazole increases the risk for hair shaft dryness, damage, and subsequent breakage, especially in Black women who also may be using heat styling or chemical relaxers.5 As a result, ketoconazole should be used with caution in Black women, with an emphasis on direct application to the scalp rather than the hair shafts.12 Additional options reported for Black patients include ciclopirox olamine and zinc pyrithione, which may have fewer risks.13

When prescribing medicated shampoos, traditional instructions regarding frequency of use to control symptoms of SD range from 2 to 3 times weekly to daily for a specified period of time determined by the dermatologist.14 However, frequency of hair washing varies greatly among Black patients, sometimes occurring only once monthly. The frequency also may change based on styling techniques (eg, braids, weaves, and wigs).15 Based on previous research underscoring the tendency for Black patients to use medicated shampoos less frequently than White patients, it is important for clinicians to understand that these cultural practices can undermine the effectiveness when medicated shampoos are prescribed for SD.16

Additionally, topical corticosteroids often are used in conjunction with antifungals to help decrease inflammation of the scalp.17 An option reported for Black patients is topical fluocinolone 0.01%; however, package instructions state to apply topically to the scalp nightly and wash the hair thoroughly each morning, which may not be feasible for Black patients based on previously mentioned differences in hair-washing techniques. An alternative option may be to apply the medication 3 to 4 times per week, washing the hair weekly rather than daily.18 Fluocinolone can be used as an ointment, solution, oil, or cream.19,20 When comparing treatment vehicles for SD, a study conducted by Chappell et al21 found that Black patients preferred using ointment or oil vehicles; White patients preferred foams and sprays, which may not be suitable for Afro hair patterns. As such, using less-drying modalities may increase compliance and treatment success in Black patients. For patients who may have involvement on the hairline, face, or ears along with hypopigmentation (which is a common skin concern associated with SD), calcineurin inhibitors can be used until resolution occurs.5,22 High et al15 found that twice-daily use of pimecrolimus rapidly normalized skin pigmentation during the first 2 weeks of use. Overall, personalization of treatment may not only avoid adverse effects but also ensure patient compliance, with the overall goal of treating to reduce yeast activity, pruritus, and dyschromia.22

Interestingly, after the website searches were completed for this study, the US Food and Drug Administration approved topical roflumilast foam for SD. In a phase III trial of 457 total patients, 36 Black patients were included.23 It was determined that 79.5% of patients overall throughout the trial achieved Investigator Global Assessment success (score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear]) plus ≥2-point improvement from baseline (on a scale of 0 [clear] to 4 [severe]) at weeks 2, 4, and 8. Although there currently are no long-term studies, roflumilast may be a promising option for Black patients with SD.23

Aside from developing an individualized treatment approach for Black patients with SD, it is important to ask targeted questions during the clinical encounter to identify factors that may be exacerbating symptoms, especially due to the wide range of hair care practices used by the Black community (eTable 2). Asking targeted questions is especially important, as prior studies have shown that extensions, hair relaxers, and particular hair products can irritate the scalp and increase the likelihood of developing SD.21,24 Rucker Wright et al25 evaluated different hair care practices among young Black females and their association with the development of SD. The authors found that using hair extensions (either braided, cornrowed, or ponytails), chemical relaxers, and hair oils every 2 weeks was associated with SD. The study also found that SD rates were roughly 20% higher among Black girls with extensions compared to Black girls without extensions, regardless of how frequently hair was washed.25

Many Black patients grease the scalp with oils that are beneficial for lubrication and reduction of abrasive damage caused by grooming; however, they also may increase incidence of SD.26 Tight curls worn by Black patients also can impede sebum from traveling down the hair shaft, leading to oil buildup on the scalp. This is the ideal environment for increased Malassezia density and higher risk for SD development.27 To balance the beneficial effects of hair oils with the increased susceptibility for SD, providers should emphasize applying these oils only to distal hair shafts, which are more likely to be damaged, and avoiding application to the scalp.19

Conclusion

Given its long-term relapsing and remitting nature, SD can be distressing for Black patients, many of whom may seek additional treatment options aside from those recommended by health care professionals. In order to better educate patients, it is important for dermatologists to know not only the common ingredients that may be present in OTC products but also the thought process behind why patients use them. Additionally, prescription treatments for Black patients with SD may require nuanced alterations to the product instructions that may prevent health disparities and provide culturally sensitive care. Overall, the literature regarding treatment for Black patients with SD is limited, and more high-quality studies are needed.

- Tucker D, Masood S. Seborrheic dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551707/

- Borda LJ, Wikramanayake TC. Seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff: a comprehensive review. J Clin Investig Dermatol. 2015;3:10.13188 /2373-1044.1000019.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Seborrheic dermatitis by the numbers. American Academy of Dermatology Skin Disease Briefs. Updated May 5, 2018. Accessed November 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/asset/49w949DPcF8RSJYIRHfDon

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:158-169.

- Draelos ZD, Kenneally DC, Hodges LT, et al. A comparison of hair quality and cosmetic acceptance following the use of two anti-dandruff shampoos. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:201-214.

- Barak-Shinar D, Green LJ. Scalp seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff therapy using a herbal and zinc pyrithione-based therapy of shampoo and scalp lotion. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:26-31.

- Satchell AC, Saurajen A, Bell C, et al. Treatment of dandruff with 5% tea tree oil shampoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:852-855.

- Herro E, Jacob SE. Mentha piperita (peppermint). Dermatitis. 2010;21:327-329.

- Sanfilippo A, English JC. An overview of medicated shampoos used in dandruff treatment. Pharm Ther. 2006;31:396-400.

- Arun PVPS, Vineetha Y, Waheed M, et al. Quantification of the minimum amount of lemon juice and apple cider vinegar required for the growth inhibition of dandruff causing fungi Malassezia furfur. Int J Sci Res in Biological Sciences. 2019;6:144-147.

- Gao HY, Li Wan Po A. Topical formulations of fluocinolone acetonide. Are creams, gels and ointments bioequivalent and does dilution affect activity? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46:71-75.

- Pauporte M, Maibach H, Lowe N, et al. Fluocinolone acetonide topical oil for scalp psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:360-364.

- Elgash M, Dlova N, Ogunleye T, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis in skin of color: clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:24-27.

- High WA, Pandya AG. Pilot trial of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in African American adults with associated hypopigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1083-1088.

- Hollins LC, Butt M, Hong J, et al. Research in brief: survey of hair care practices in various ethnic and racial pediatric populations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:494-496.

- Halder RM, Roberts CI, Nootheti PK. Cutaneous diseases in the black races. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:679-687, ix.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Friedmann DP, Mishra V, Batty T. Progressive facial papules in an African- American patient: an atypical presentation of seborrheic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:44-45.

- Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:185-190.

- Chappell J, Mattox A, Simonetta C, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp in populations practicing less frequent hair washing: ketoconazole 2% foam versus ketoconazole 2% shampoo. three-year data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB54.

- Dadzie OE, Salam A. The hair grooming practices of women of African descent in London, United Kingdom: findings of a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1021-1024.

- Blauvelt A, Draelos ZD, Stein Gold L, et al. Roflumilast foam 0.3% for adolescent and adult patients with seborrheic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, vehicle-controlled, phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:986-993.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Rucker Wright D, Gathers R, Kapke A, et al. Hair care practices and their association with scalp and hair disorders in African American girls. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:253-262.

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319.

- Mayo T, Dinkins J, Elewski B. Hair oils may worsen seborrheic dermatitis in Black patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:151-152.

- Tucker D, Masood S. Seborrheic dermatitis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated March 1, 2024. Accessed December 19, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK551707/

- Borda LJ, Wikramanayake TC. Seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff: a comprehensive review. J Clin Investig Dermatol. 2015;3:10.13188 /2373-1044.1000019.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Seborrheic dermatitis by the numbers. American Academy of Dermatology Skin Disease Briefs. Updated May 5, 2018. Accessed November 22, 2024. https://www.aad.org/asset/49w949DPcF8RSJYIRHfDon

- Davis SA, Naarahari S, Feldman SR, et al. Top dermatologic conditions in patients of color: an analysis of nationally representative data. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:466-473.

- Borda LJ, Perper M, Keri JE. Treatment of seborrheic dermatitis: a comprehensive review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2019;30:158-169.

- Draelos ZD, Kenneally DC, Hodges LT, et al. A comparison of hair quality and cosmetic acceptance following the use of two anti-dandruff shampoos. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2005;10:201-214.

- Barak-Shinar D, Green LJ. Scalp seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff therapy using a herbal and zinc pyrithione-based therapy of shampoo and scalp lotion. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:26-31.

- Satchell AC, Saurajen A, Bell C, et al. Treatment of dandruff with 5% tea tree oil shampoo. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:852-855.

- Herro E, Jacob SE. Mentha piperita (peppermint). Dermatitis. 2010;21:327-329.

- Sanfilippo A, English JC. An overview of medicated shampoos used in dandruff treatment. Pharm Ther. 2006;31:396-400.

- Arun PVPS, Vineetha Y, Waheed M, et al. Quantification of the minimum amount of lemon juice and apple cider vinegar required for the growth inhibition of dandruff causing fungi Malassezia furfur. Int J Sci Res in Biological Sciences. 2019;6:144-147.

- Gao HY, Li Wan Po A. Topical formulations of fluocinolone acetonide. Are creams, gels and ointments bioequivalent and does dilution affect activity? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1994;46:71-75.

- Pauporte M, Maibach H, Lowe N, et al. Fluocinolone acetonide topical oil for scalp psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:360-364.

- Elgash M, Dlova N, Ogunleye T, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis in skin of color: clinical considerations. J Drugs Dermatol. 2019;18:24-27.

- High WA, Pandya AG. Pilot trial of 1% pimecrolimus cream in the treatment of seborrheic dermatitis in African American adults with associated hypopigmentation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:1083-1088.

- Hollins LC, Butt M, Hong J, et al. Research in brief: survey of hair care practices in various ethnic and racial pediatric populations. Pediatr Dermatol. 2022;39:494-496.

- Halder RM, Roberts CI, Nootheti PK. Cutaneous diseases in the black races. Dermatol Clin. 2003;21:679-687, ix.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Friedmann DP, Mishra V, Batty T. Progressive facial papules in an African- American patient: an atypical presentation of seborrheic dermatitis. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2018;11:44-45.

- Clark GW, Pope SM, Jaboori KA. Diagnosis and treatment of seborrheic dermatitis. Am Fam Physician. 2015;91:185-190.

- Chappell J, Mattox A, Simonetta C, et al. Seborrheic dermatitis of the scalp in populations practicing less frequent hair washing: ketoconazole 2% foam versus ketoconazole 2% shampoo. three-year data. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:AB54.

- Dadzie OE, Salam A. The hair grooming practices of women of African descent in London, United Kingdom: findings of a cross-sectional study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1021-1024.

- Blauvelt A, Draelos ZD, Stein Gold L, et al. Roflumilast foam 0.3% for adolescent and adult patients with seborrheic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, vehicle-controlled, phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:986-993.

- Taylor SC, Barbosa V, Burgess C, et al. Hair and scalp disorders in adult and pediatric patients with skin of color. Cutis. 2017;100:31-35.

- Rucker Wright D, Gathers R, Kapke A, et al. Hair care practices and their association with scalp and hair disorders in African American girls. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:253-262.

- Raffi J, Suresh R, Agbai O. Clinical recognition and management of alopecia in women of color. Int J Womens Dermatol. 2019;5:314-319.

- Mayo T, Dinkins J, Elewski B. Hair oils may worsen seborrheic dermatitis in Black patients. Skin Appendage Disord. 2023;9:151-152.

Treatment of Seborrheic Dermatitis in Black Patients

Treatment of Seborrheic Dermatitis in Black Patients

PRACTICE POINTS

- Cultural awareness when treating Black patients with seborrheic dermatitis is vital to providing appropriate care, as hair care practices may impact treatment options and regimen.

- Knowledge about over-the-counter products that are targeted toward Black patients and the ingredients they contain can assist in providing better counseling to patients and improve shared decision-making.

Debunking Dermatology Myths to Enhance Patient Care

Debunking Dermatology Myths to Enhance Patient Care

The advent of social media has revolutionized the way patients access and consume health information. While this increased access has its merits, it also has given rise to the proliferation of medical myths, which have considerable effects on patient-physician interactions.1 Myths are prevalent across all fields of health care, ranging from misconceptions about disease etiology and prevention to the efficacy and safety of treatments. This influx of misinformation can derail the clinical encounter, shifting the focus from evidence-based medicine to myth-busting.2 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this issue, as widespread lockdowns and social distancing measures limited access to in-person medical consultations, prompting patients to increasingly turn to online sources for health information that often were unreliable, thereby bypassing professional medical advice.3 Herein, we highlight the challenges and implications of common dermatology myths and provide strategies for effectively debunking these myths to enhance patient care.

Common Dermatology Myths

In dermatology, where visible and often distressing conditions such as acne and hair loss are common, the impact of myths on patient perceptions and treatment outcomes can be particularly profound. Patients often arrive for consultations with preconceived notions that are not grounded in scientific evidence. Common dermatologic myths include eczema and the efficacy of topical corticosteroids, the causes and treatment of hair loss, and risk factors associated with skin cancer.

Eczema and Topical Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids for eczema are safe and effective, but nonadherence due to phobias stemming from misinformation online can impede treatment.4 Myths such as red skin syndrome and topical corticosteroid addiction are prevalent. Red skin syndrome refers to claims that prolonged use of topical corticosteroids causes severe redness and burning of the skin and worsening eczema symptoms upon withdrawal. Topical corticosteroid addiction suggests that patients become dependent on corticosteroids, requiring higher doses over time to maintain efficacy. These misconceptions contribute to fear and avoidance of prescribed treatments.

Eczema myths often divert focus from its true etiology as a genetic inflammatory skin disease, suggesting instead that it is caused by leaky gut or food intolerances.4 Risks such as skin thinning and stunted growth often are exaggerated on social media and other nonmedical platforms, though these adverse effects rarely are seen when topical corticosteroids are used appropriately under medical supervision. Misinformation often is linked to companies promoting unregulated consultations, tests, or supposedly natural treatments, including herbal remedies that may surreptitiously contain corticosteroids without clear labeling. This fosters distrust of US Food and Drug Administration– approved and dermatologist-prescribed treatments, as patients may cite concerns based on experiences with or claims about unapproved products.4

Sunscreen and Skin Cancer—In 2018, the American Academy of Dermatology prioritized skin cancer prevention due to suboptimal public adoption of photoprotection measures.5 However, the proliferation of misinformation regarding sunscreen and its potential to cause skin cancer is a more pressing issue. Myths range from claims that sunscreen is ineffective to warnings that it is dangerous, with some social media influencers even suggesting that sunscreen causes skin cancer due to toxic ingredients.6 Oxybenzone, typically found in chemical sunscreens, has been criticized by some advocacy groups and social media influencers as a potential hormone disruptor (ie, a chemical that could interfere with hormone production).7 However, no conclusive evidence has shown that oxybenzone is harmful to humans. Consumer concerns often are based on animal studies in which rats are fed oxybenzone, but mathematical modeling has indicated it would take 277 years of sunscreen use by humans to match the doses used in these studies.8 The false association between sunscreen use and skin cancer is based on flawed studies that found higher rates of skin cancer—including melanoma—in sunscreen users compared to those who did not use sunscreen. However, those using sunscreen also were more likely to travel to sunnier climates and engage in sunbathing, and it may have been this increased sun exposure that elevated their risk for skin cancer.7 It is imperative that the dermatology community counteract this type of misinformation with evidence-based advice.

Hair Loss—Some patients believe that hair loss is caused by wearing hats, frequent shampooing, or even stress in a way that oversimplifies complex physiological processes. Biotin, which commonly is added to supplements for hair, skin, and nails, has been linked to potential risks, such as interference with laboratory testing and false-positive or false-negative results in critical medical tests, which can lead to misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment.9 Biotin interference can result in falsely low troponin readings, which are critical in diagnosing acute myocardial infarction. Tests for other hormones such as cortisol and parathyroid hormone also are affected, potentially impacting the evaluation and management of endocrine disorders. The US Food and Drug Administration has issued warnings for patients on this topic, emphasizing the importance of informing health care providers about any biotin supplementation prior to laboratory testing. Despite its popularity, there is no substantial scientific evidence to suggest that biotin supplementation promotes hair growth in anyone other than those with deficiency, which is quite rare.9

Myths and the Patient-Physician Relationship

The proliferation of medical myths and misinformation affects the dynamic between patients and dermatologists in several ways. Research across various medical fields has demonstrated that misinformation can substantially impact patient behavior and treatment adherence. Like many other specialists, dermatologists often spend considerable time during consultations with patients debunking myths and correcting misconceptions, which can detract from discussing more critical aspects of the patient’s condition and treatment plan and lead to frustration and anxiety among patients. It also can be challenging for physicians to have these conversations without alienating patients, who may distrust medical recommendations and believe that natural or alternative treatments are superior. This can lead to noncompliance with prescribed treatments, and patients may instead opt to try unproven remedies they encounter online, ultimately resulting in poorer health outcomes.

Strategies to Debunk Myths

By implementing the following strategies, dermatologists can combat the spread of myths, foster trust among patients, and promote adherence to evidence-based treatments:

- Provide educational outreach. Preemptively address myths by giving patients accurate and accessible resources. Including a dedicated section on your clinic’s website with articles, frequently asked questions, videos, and links to reputable sources can be effective. Sharing patient testimonials and before-and-after photographs to demonstrate the success of evidence-based treatments also is recommended, as real-life stories can be powerful tools in dispelling myths.

- Practice effective communication. Involve patients in the decision-making process by discussing their treatment goals, preferences, and concerns. It is important to present all options clearly, including the potential benefits and adverse effects. Discuss the expected outcomes and timelines, and be transparent about the limitations of certain treatment—honesty helps build trust and sets realistic expectations.

- Conduct structured consultations. Ensure that consultations with patients follow a structured format—history, physical examination, and discussion—to help keep the focus on evidence-based practice.

- Leverage technology. Guide patients toward reliable digital patient education tools to empower them with accurate information. Hosting live sessions on social media platforms during which patients can ask questions and receive evidence-based answers also can be beneficial.

Final Thoughts

In summary, the rise of medical myths poses a considerable challenge to dermatologic practice. By understanding the sources and impacts of these myths and employing strategies to dispel them, dermatologists can better navigate the complexities of modern patient interactions and ensure that care remains grounded in scientific evidence.

- Kessler SH, Bachmann E. Debunking health myths on the internet: the persuasive effect of (visual) online communication. Z Gesundheitswissenschaften J Public Health. 2022;30:1823-1835.

- Fridman I, Johnson S, Elston Lafata J. Health information and misinformation: a framework to guide research and practice. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:E38687.

- Di Novi C, Kovacic M, Orso CE. Online health information seeking behavior, healthcare access, and health status during exceptional times. J Econ Behav Organ. 2024;220:675-690.

- Finnegan P, Murphy M, O’Connor C. #corticophobia: a review on online misinformation related to topical steroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;48:112-115.

- Yang EJ, Beck KM, Maarouf M, et al. Truths and myths in sunscreen labeling. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:1288-1292.

- Hopkins C. What Gen Z gets wrong about sunscreen. New York Times. Published May 27, 2024. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/27/well/live/sunscreen-skin-cancer-gen-z.html

- Harvard Health Publishing. The science of sunscreen. Published February 15, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/the-science-of-sunscreen

- Lim HW, Arellano-Mendoza MI, Stengel F. Current challenges in photoprotection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:S91-S99.

- Li D, Ferguson A, Cervinski MA, et al. AACC guidance document on biotin interference in laboratory tests. J Appl Lab Med. 2020; 5:575-587.

The advent of social media has revolutionized the way patients access and consume health information. While this increased access has its merits, it also has given rise to the proliferation of medical myths, which have considerable effects on patient-physician interactions.1 Myths are prevalent across all fields of health care, ranging from misconceptions about disease etiology and prevention to the efficacy and safety of treatments. This influx of misinformation can derail the clinical encounter, shifting the focus from evidence-based medicine to myth-busting.2 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this issue, as widespread lockdowns and social distancing measures limited access to in-person medical consultations, prompting patients to increasingly turn to online sources for health information that often were unreliable, thereby bypassing professional medical advice.3 Herein, we highlight the challenges and implications of common dermatology myths and provide strategies for effectively debunking these myths to enhance patient care.

Common Dermatology Myths

In dermatology, where visible and often distressing conditions such as acne and hair loss are common, the impact of myths on patient perceptions and treatment outcomes can be particularly profound. Patients often arrive for consultations with preconceived notions that are not grounded in scientific evidence. Common dermatologic myths include eczema and the efficacy of topical corticosteroids, the causes and treatment of hair loss, and risk factors associated with skin cancer.

Eczema and Topical Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids for eczema are safe and effective, but nonadherence due to phobias stemming from misinformation online can impede treatment.4 Myths such as red skin syndrome and topical corticosteroid addiction are prevalent. Red skin syndrome refers to claims that prolonged use of topical corticosteroids causes severe redness and burning of the skin and worsening eczema symptoms upon withdrawal. Topical corticosteroid addiction suggests that patients become dependent on corticosteroids, requiring higher doses over time to maintain efficacy. These misconceptions contribute to fear and avoidance of prescribed treatments.

Eczema myths often divert focus from its true etiology as a genetic inflammatory skin disease, suggesting instead that it is caused by leaky gut or food intolerances.4 Risks such as skin thinning and stunted growth often are exaggerated on social media and other nonmedical platforms, though these adverse effects rarely are seen when topical corticosteroids are used appropriately under medical supervision. Misinformation often is linked to companies promoting unregulated consultations, tests, or supposedly natural treatments, including herbal remedies that may surreptitiously contain corticosteroids without clear labeling. This fosters distrust of US Food and Drug Administration– approved and dermatologist-prescribed treatments, as patients may cite concerns based on experiences with or claims about unapproved products.4

Sunscreen and Skin Cancer—In 2018, the American Academy of Dermatology prioritized skin cancer prevention due to suboptimal public adoption of photoprotection measures.5 However, the proliferation of misinformation regarding sunscreen and its potential to cause skin cancer is a more pressing issue. Myths range from claims that sunscreen is ineffective to warnings that it is dangerous, with some social media influencers even suggesting that sunscreen causes skin cancer due to toxic ingredients.6 Oxybenzone, typically found in chemical sunscreens, has been criticized by some advocacy groups and social media influencers as a potential hormone disruptor (ie, a chemical that could interfere with hormone production).7 However, no conclusive evidence has shown that oxybenzone is harmful to humans. Consumer concerns often are based on animal studies in which rats are fed oxybenzone, but mathematical modeling has indicated it would take 277 years of sunscreen use by humans to match the doses used in these studies.8 The false association between sunscreen use and skin cancer is based on flawed studies that found higher rates of skin cancer—including melanoma—in sunscreen users compared to those who did not use sunscreen. However, those using sunscreen also were more likely to travel to sunnier climates and engage in sunbathing, and it may have been this increased sun exposure that elevated their risk for skin cancer.7 It is imperative that the dermatology community counteract this type of misinformation with evidence-based advice.

Hair Loss—Some patients believe that hair loss is caused by wearing hats, frequent shampooing, or even stress in a way that oversimplifies complex physiological processes. Biotin, which commonly is added to supplements for hair, skin, and nails, has been linked to potential risks, such as interference with laboratory testing and false-positive or false-negative results in critical medical tests, which can lead to misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment.9 Biotin interference can result in falsely low troponin readings, which are critical in diagnosing acute myocardial infarction. Tests for other hormones such as cortisol and parathyroid hormone also are affected, potentially impacting the evaluation and management of endocrine disorders. The US Food and Drug Administration has issued warnings for patients on this topic, emphasizing the importance of informing health care providers about any biotin supplementation prior to laboratory testing. Despite its popularity, there is no substantial scientific evidence to suggest that biotin supplementation promotes hair growth in anyone other than those with deficiency, which is quite rare.9

Myths and the Patient-Physician Relationship

The proliferation of medical myths and misinformation affects the dynamic between patients and dermatologists in several ways. Research across various medical fields has demonstrated that misinformation can substantially impact patient behavior and treatment adherence. Like many other specialists, dermatologists often spend considerable time during consultations with patients debunking myths and correcting misconceptions, which can detract from discussing more critical aspects of the patient’s condition and treatment plan and lead to frustration and anxiety among patients. It also can be challenging for physicians to have these conversations without alienating patients, who may distrust medical recommendations and believe that natural or alternative treatments are superior. This can lead to noncompliance with prescribed treatments, and patients may instead opt to try unproven remedies they encounter online, ultimately resulting in poorer health outcomes.

Strategies to Debunk Myths

By implementing the following strategies, dermatologists can combat the spread of myths, foster trust among patients, and promote adherence to evidence-based treatments:

- Provide educational outreach. Preemptively address myths by giving patients accurate and accessible resources. Including a dedicated section on your clinic’s website with articles, frequently asked questions, videos, and links to reputable sources can be effective. Sharing patient testimonials and before-and-after photographs to demonstrate the success of evidence-based treatments also is recommended, as real-life stories can be powerful tools in dispelling myths.

- Practice effective communication. Involve patients in the decision-making process by discussing their treatment goals, preferences, and concerns. It is important to present all options clearly, including the potential benefits and adverse effects. Discuss the expected outcomes and timelines, and be transparent about the limitations of certain treatment—honesty helps build trust and sets realistic expectations.

- Conduct structured consultations. Ensure that consultations with patients follow a structured format—history, physical examination, and discussion—to help keep the focus on evidence-based practice.

- Leverage technology. Guide patients toward reliable digital patient education tools to empower them with accurate information. Hosting live sessions on social media platforms during which patients can ask questions and receive evidence-based answers also can be beneficial.

Final Thoughts

In summary, the rise of medical myths poses a considerable challenge to dermatologic practice. By understanding the sources and impacts of these myths and employing strategies to dispel them, dermatologists can better navigate the complexities of modern patient interactions and ensure that care remains grounded in scientific evidence.

The advent of social media has revolutionized the way patients access and consume health information. While this increased access has its merits, it also has given rise to the proliferation of medical myths, which have considerable effects on patient-physician interactions.1 Myths are prevalent across all fields of health care, ranging from misconceptions about disease etiology and prevention to the efficacy and safety of treatments. This influx of misinformation can derail the clinical encounter, shifting the focus from evidence-based medicine to myth-busting.2 The COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated this issue, as widespread lockdowns and social distancing measures limited access to in-person medical consultations, prompting patients to increasingly turn to online sources for health information that often were unreliable, thereby bypassing professional medical advice.3 Herein, we highlight the challenges and implications of common dermatology myths and provide strategies for effectively debunking these myths to enhance patient care.

Common Dermatology Myths

In dermatology, where visible and often distressing conditions such as acne and hair loss are common, the impact of myths on patient perceptions and treatment outcomes can be particularly profound. Patients often arrive for consultations with preconceived notions that are not grounded in scientific evidence. Common dermatologic myths include eczema and the efficacy of topical corticosteroids, the causes and treatment of hair loss, and risk factors associated with skin cancer.

Eczema and Topical Corticosteroids—Topical corticosteroids for eczema are safe and effective, but nonadherence due to phobias stemming from misinformation online can impede treatment.4 Myths such as red skin syndrome and topical corticosteroid addiction are prevalent. Red skin syndrome refers to claims that prolonged use of topical corticosteroids causes severe redness and burning of the skin and worsening eczema symptoms upon withdrawal. Topical corticosteroid addiction suggests that patients become dependent on corticosteroids, requiring higher doses over time to maintain efficacy. These misconceptions contribute to fear and avoidance of prescribed treatments.

Eczema myths often divert focus from its true etiology as a genetic inflammatory skin disease, suggesting instead that it is caused by leaky gut or food intolerances.4 Risks such as skin thinning and stunted growth often are exaggerated on social media and other nonmedical platforms, though these adverse effects rarely are seen when topical corticosteroids are used appropriately under medical supervision. Misinformation often is linked to companies promoting unregulated consultations, tests, or supposedly natural treatments, including herbal remedies that may surreptitiously contain corticosteroids without clear labeling. This fosters distrust of US Food and Drug Administration– approved and dermatologist-prescribed treatments, as patients may cite concerns based on experiences with or claims about unapproved products.4

Sunscreen and Skin Cancer—In 2018, the American Academy of Dermatology prioritized skin cancer prevention due to suboptimal public adoption of photoprotection measures.5 However, the proliferation of misinformation regarding sunscreen and its potential to cause skin cancer is a more pressing issue. Myths range from claims that sunscreen is ineffective to warnings that it is dangerous, with some social media influencers even suggesting that sunscreen causes skin cancer due to toxic ingredients.6 Oxybenzone, typically found in chemical sunscreens, has been criticized by some advocacy groups and social media influencers as a potential hormone disruptor (ie, a chemical that could interfere with hormone production).7 However, no conclusive evidence has shown that oxybenzone is harmful to humans. Consumer concerns often are based on animal studies in which rats are fed oxybenzone, but mathematical modeling has indicated it would take 277 years of sunscreen use by humans to match the doses used in these studies.8 The false association between sunscreen use and skin cancer is based on flawed studies that found higher rates of skin cancer—including melanoma—in sunscreen users compared to those who did not use sunscreen. However, those using sunscreen also were more likely to travel to sunnier climates and engage in sunbathing, and it may have been this increased sun exposure that elevated their risk for skin cancer.7 It is imperative that the dermatology community counteract this type of misinformation with evidence-based advice.

Hair Loss—Some patients believe that hair loss is caused by wearing hats, frequent shampooing, or even stress in a way that oversimplifies complex physiological processes. Biotin, which commonly is added to supplements for hair, skin, and nails, has been linked to potential risks, such as interference with laboratory testing and false-positive or false-negative results in critical medical tests, which can lead to misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment.9 Biotin interference can result in falsely low troponin readings, which are critical in diagnosing acute myocardial infarction. Tests for other hormones such as cortisol and parathyroid hormone also are affected, potentially impacting the evaluation and management of endocrine disorders. The US Food and Drug Administration has issued warnings for patients on this topic, emphasizing the importance of informing health care providers about any biotin supplementation prior to laboratory testing. Despite its popularity, there is no substantial scientific evidence to suggest that biotin supplementation promotes hair growth in anyone other than those with deficiency, which is quite rare.9

Myths and the Patient-Physician Relationship

The proliferation of medical myths and misinformation affects the dynamic between patients and dermatologists in several ways. Research across various medical fields has demonstrated that misinformation can substantially impact patient behavior and treatment adherence. Like many other specialists, dermatologists often spend considerable time during consultations with patients debunking myths and correcting misconceptions, which can detract from discussing more critical aspects of the patient’s condition and treatment plan and lead to frustration and anxiety among patients. It also can be challenging for physicians to have these conversations without alienating patients, who may distrust medical recommendations and believe that natural or alternative treatments are superior. This can lead to noncompliance with prescribed treatments, and patients may instead opt to try unproven remedies they encounter online, ultimately resulting in poorer health outcomes.

Strategies to Debunk Myths

By implementing the following strategies, dermatologists can combat the spread of myths, foster trust among patients, and promote adherence to evidence-based treatments:

- Provide educational outreach. Preemptively address myths by giving patients accurate and accessible resources. Including a dedicated section on your clinic’s website with articles, frequently asked questions, videos, and links to reputable sources can be effective. Sharing patient testimonials and before-and-after photographs to demonstrate the success of evidence-based treatments also is recommended, as real-life stories can be powerful tools in dispelling myths.

- Practice effective communication. Involve patients in the decision-making process by discussing their treatment goals, preferences, and concerns. It is important to present all options clearly, including the potential benefits and adverse effects. Discuss the expected outcomes and timelines, and be transparent about the limitations of certain treatment—honesty helps build trust and sets realistic expectations.

- Conduct structured consultations. Ensure that consultations with patients follow a structured format—history, physical examination, and discussion—to help keep the focus on evidence-based practice.

- Leverage technology. Guide patients toward reliable digital patient education tools to empower them with accurate information. Hosting live sessions on social media platforms during which patients can ask questions and receive evidence-based answers also can be beneficial.

Final Thoughts

In summary, the rise of medical myths poses a considerable challenge to dermatologic practice. By understanding the sources and impacts of these myths and employing strategies to dispel them, dermatologists can better navigate the complexities of modern patient interactions and ensure that care remains grounded in scientific evidence.

- Kessler SH, Bachmann E. Debunking health myths on the internet: the persuasive effect of (visual) online communication. Z Gesundheitswissenschaften J Public Health. 2022;30:1823-1835.

- Fridman I, Johnson S, Elston Lafata J. Health information and misinformation: a framework to guide research and practice. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:E38687.

- Di Novi C, Kovacic M, Orso CE. Online health information seeking behavior, healthcare access, and health status during exceptional times. J Econ Behav Organ. 2024;220:675-690.

- Finnegan P, Murphy M, O’Connor C. #corticophobia: a review on online misinformation related to topical steroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;48:112-115.

- Yang EJ, Beck KM, Maarouf M, et al. Truths and myths in sunscreen labeling. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:1288-1292.

- Hopkins C. What Gen Z gets wrong about sunscreen. New York Times. Published May 27, 2024. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/27/well/live/sunscreen-skin-cancer-gen-z.html

- Harvard Health Publishing. The science of sunscreen. Published February 15, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/the-science-of-sunscreen

- Lim HW, Arellano-Mendoza MI, Stengel F. Current challenges in photoprotection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:S91-S99.

- Li D, Ferguson A, Cervinski MA, et al. AACC guidance document on biotin interference in laboratory tests. J Appl Lab Med. 2020; 5:575-587.

- Kessler SH, Bachmann E. Debunking health myths on the internet: the persuasive effect of (visual) online communication. Z Gesundheitswissenschaften J Public Health. 2022;30:1823-1835.

- Fridman I, Johnson S, Elston Lafata J. Health information and misinformation: a framework to guide research and practice. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:E38687.

- Di Novi C, Kovacic M, Orso CE. Online health information seeking behavior, healthcare access, and health status during exceptional times. J Econ Behav Organ. 2024;220:675-690.

- Finnegan P, Murphy M, O’Connor C. #corticophobia: a review on online misinformation related to topical steroids. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;48:112-115.

- Yang EJ, Beck KM, Maarouf M, et al. Truths and myths in sunscreen labeling. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2018;17:1288-1292.

- Hopkins C. What Gen Z gets wrong about sunscreen. New York Times. Published May 27, 2024. Accessed December 16, 2024. https://www.nytimes.com/2024/05/27/well/live/sunscreen-skin-cancer-gen-z.html

- Harvard Health Publishing. The science of sunscreen. Published February 15, 2021. Accessed December 9, 2024. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/the-science-of-sunscreen

- Lim HW, Arellano-Mendoza MI, Stengel F. Current challenges in photoprotection. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:S91-S99.

- Li D, Ferguson A, Cervinski MA, et al. AACC guidance document on biotin interference in laboratory tests. J Appl Lab Med. 2020; 5:575-587.