User login

Colorectal Cancer Characteristics and Mortality From Propensity Score-Matched Cohorts of Urban and Rural Veterans

Colorectal Cancer Characteristics and Mortality From Propensity Score-Matched Cohorts of Urban and Rural Veterans

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with an estimated 52,550 deaths in 2023.1 However, the disease burden varies among different segments of the population.2 While both CRC incidence and mortality have been decreasing due to screening and advances in treatment, there are disparities in incidence and mortality across the sociodemographic spectrum including race, ethnicity, education, and income.1-4 While CRC incidence is decreasing for older adults, it is increasing among those aged < 55 years.5 The incidence of CRC in adults aged 40 to 54 years has increased by 0.5% to 1.3% annually since the mid-1990s.6 The US Preventive Services Task Force now recommends starting CRC screening at age 45 years for asymptomatic adults with average risk.7

Disparities also exist across geographical boundaries and living environment. Rural Americans faces additional challenges in health and lifestyle that can affect CRC outcomes. Compared to their urban counterparts, rural residents are more likely to be older, have lower levels of education, higher levels of poverty, lack health insurance, and less access to health care practitioners (HCPs).8-10 Geographic proximity, defined as travel time or physical distance to a health facility, has been recognized as a predictor of inferior outcomes.11 These aspects of rural living may pose challenges for accessing care for CRC screening and treatment.11-13 National and local studies have shown disparities in CRC screening rates, incidence, and mortality between rural and urban populations.14-16

It is unclear whether rural/urban disparities persist under the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health care delivery model. This study examined differences in baseline characteristics and mortality between rural and urban veterans newly diagnosed with CRC. We also focused on a subpopulation aged ≤ 45 years.

Methods

This study extracted national data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) hosted in the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) environment. VINCI is an initiative to improve access to VA data and facilitate the analysis of these data while ensuring veterans’ privacy and data security.17 CDW is the VHA business intelligence information repository, which extracts data from clinical and nonclinical sources following prescribed and validated protocols. Data extracted included demographics, diagnosis, and procedure codes for both inpatient and outpatient encounters, vital signs, and vital status. This study used data previously extracted from a national cohort of veterans that encompassed all patients who received a group of commonly prescribed medications, such as statins, proton pump inhibitors, histamine-2 blockers, acetaminophen-containing products, and hydrocortisone-containing skin applications. This cohort encompassed 8,648,754 veterans, from whom 2,460,727 had encounters during fiscal years (FY) 2016 to 2021 (study period). The cohort was used to ensure that subjects were VHA patients, allowing them to adequately capture their clinical profiles.

Patients were identified as rural or urban based on their residence address at the date of their first diagnosis of CRC. The Geospatial Service Support Center (GSSC) aggregates and updates veterans’ residence address records for all enrolled veterans from the National Change of Address database. The data contain 1 record per enrollee. GSSC Geocoded Enrollee File contains enrollee addresses and their rurality indicators, categorized as urban, rural, or highly rural.18 Rurality is defined by the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) categories developed by the Department of Agriculture and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services.19 Urban areas had RUCA codes of 1.0 to 1.1, and highly rural areas had RUCA scores of 10.0. All other areas were classified as rural. Since the proportion of veterans from highly rural areas was small, we included residents from highly rural areas in the rural residents’ group.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All veterans newly diagnosed with CRC from FY 2016 to 2021 were included. We used the ninth and tenth clinical modification revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) to define CRC diagnosis (Supplemental materials).4,20 To ensure that patients were newly diagnosed with CRC, this study excluded patients with a previous ICD-9-CM code for CRC diagnosis since FY 2003.

Comorbidities were identified using diagnosis and procedure codes from inpatient and outpatient encounters, which were used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) at the time of CRC diagnosis using the weighted method described by Schneeweiss et al.21 We defined CRC high-risk conditions and CRC screening tests, including flexible sigmoidoscopy and stool tests, as described in previous studies (Supplemental materials).20

The main outcome was total mortality. The date of death was extracted from the VHA Death Ascertainment File, which contains mortality data from the Master Person Index file in CDW and the Social Security Administration Death Master File. We used the date of death from any cause, as cause of death was not available.

A propensity score (PS) was created to match rural (including highly rural) and urban residents at a ratio of 1:1. Using a standard procedure described in prior publications, multivariable logistic regression used all baseline characteristics to estimate the PS and perform nearest-number matching without replacement.22,23 A caliper of 0.01 maximized the matched cohort size and achieved balance (Supplemental materials). We then examined the balance of baseline characteristics between PS-matched groups.

Analyses

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis estimated the hazard ratio (HR) of death in rural residents compared to urban residents in the PS-matched cohort. The outcome event was the date of death during the study’s follow-up period (defined as period from first CRC diagnosis to death or study end), with censoring at the study’s end date (September 30, 2021). The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by inspecting the Kaplan-Meier curves. Multiple analyses examined the HR of total mortality in the PS-matched cohort, stratified by sex, race, and ethnicity. We also examined the HR of total mortality stratified by duration of follow-up.

Another PS-matching analysis among veterans aged ≤ 45 years was performed using the same techniques described earlier in this article. We performed a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to compare mortality in PS-matched urban and rural veterans aged ≤ 45 years. The HR of death in all veterans aged ≤ 45 years (before PS-matching) was estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, adjusting for PS.

Dichotomous variables were compared using X2 tests and continuous variables were compared using t tests. Baseline characteristics with missing values were converted into categorical variables and the proportion of subjects with missing values was equalized between treatment groups after PS-matching. For subgroup analysis, we examined the HR of total mortality in each subgroup using separate Cox proportional hazards regression models similar to the primary analysis but adjusted for PS. Due to multiple comparisons in the subgroup analysis, the findings should be considered exploratory. Statistical tests were 2-tailed, and significance was defined as P < .05. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted from June 2022 to January 2023 using STATA, Version 17. The VA Orlando Healthcare System Institutional Review Board approved the study and waived requirements for informed consent because only deidentified data were used.

Results

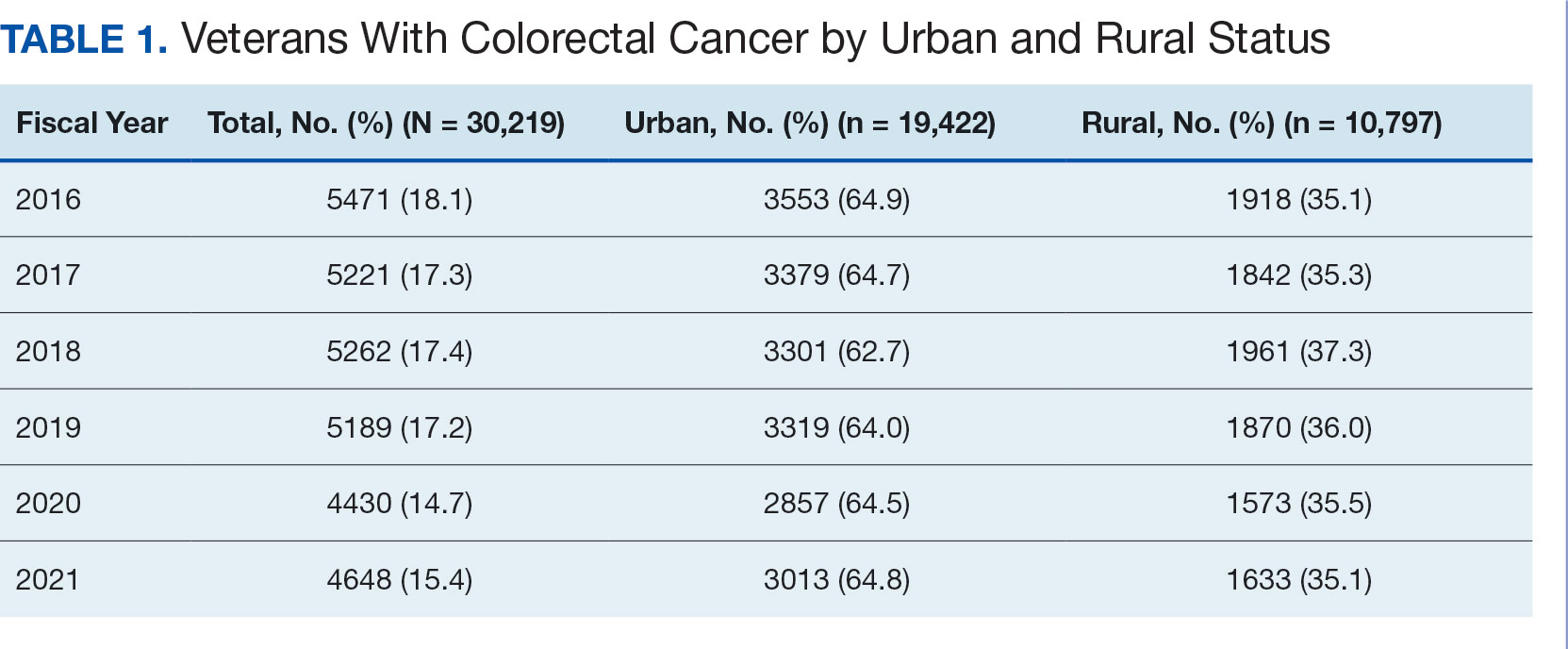

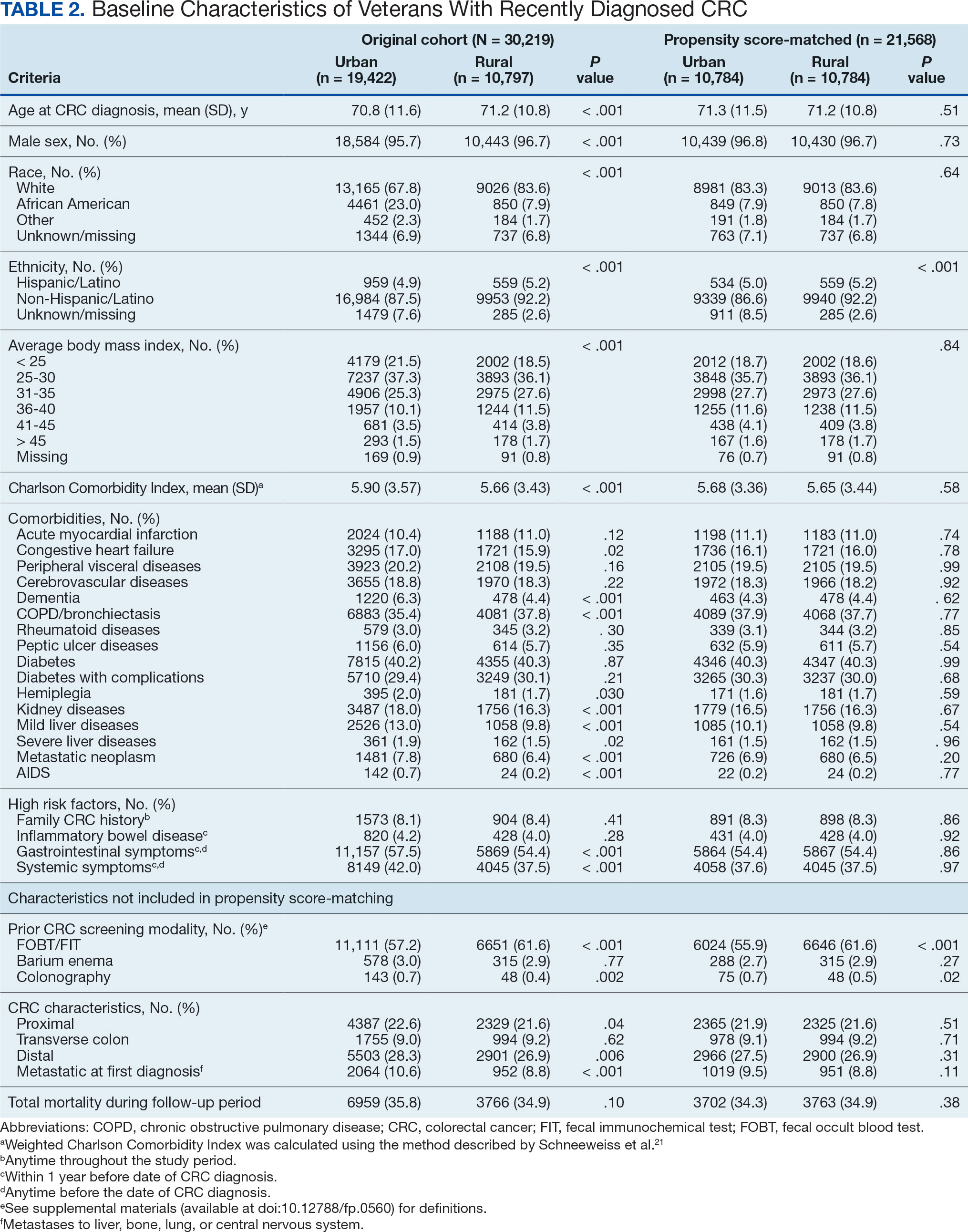

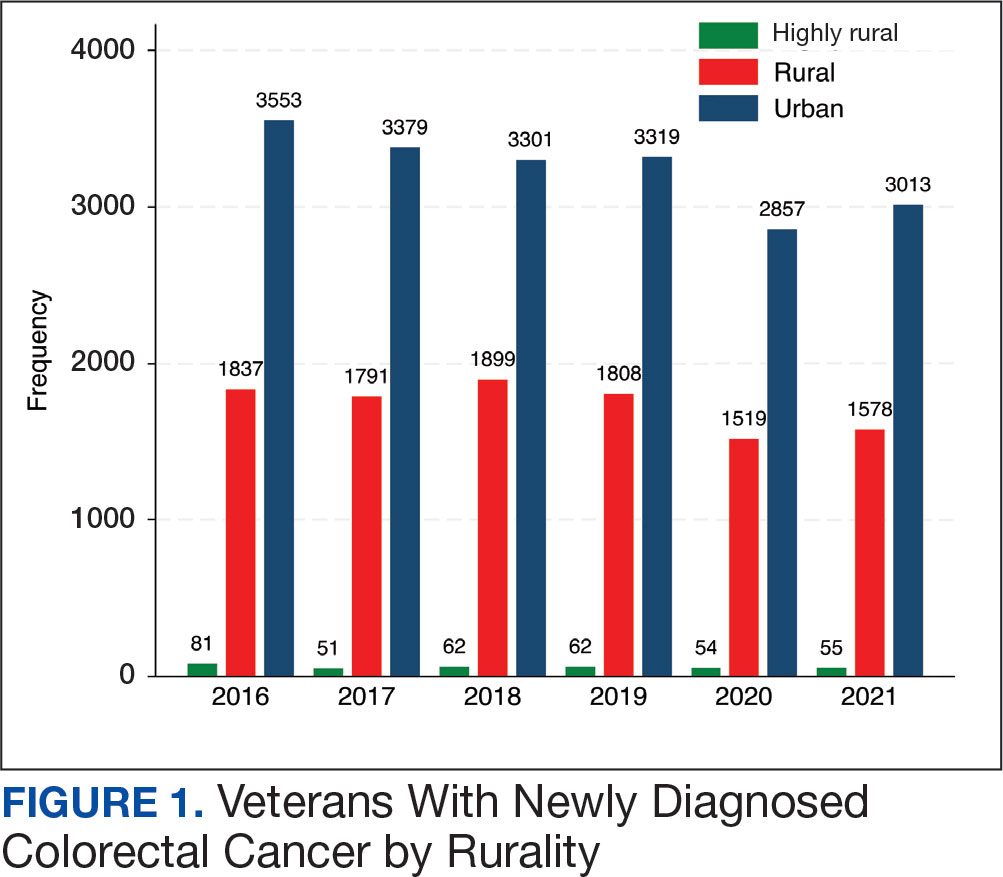

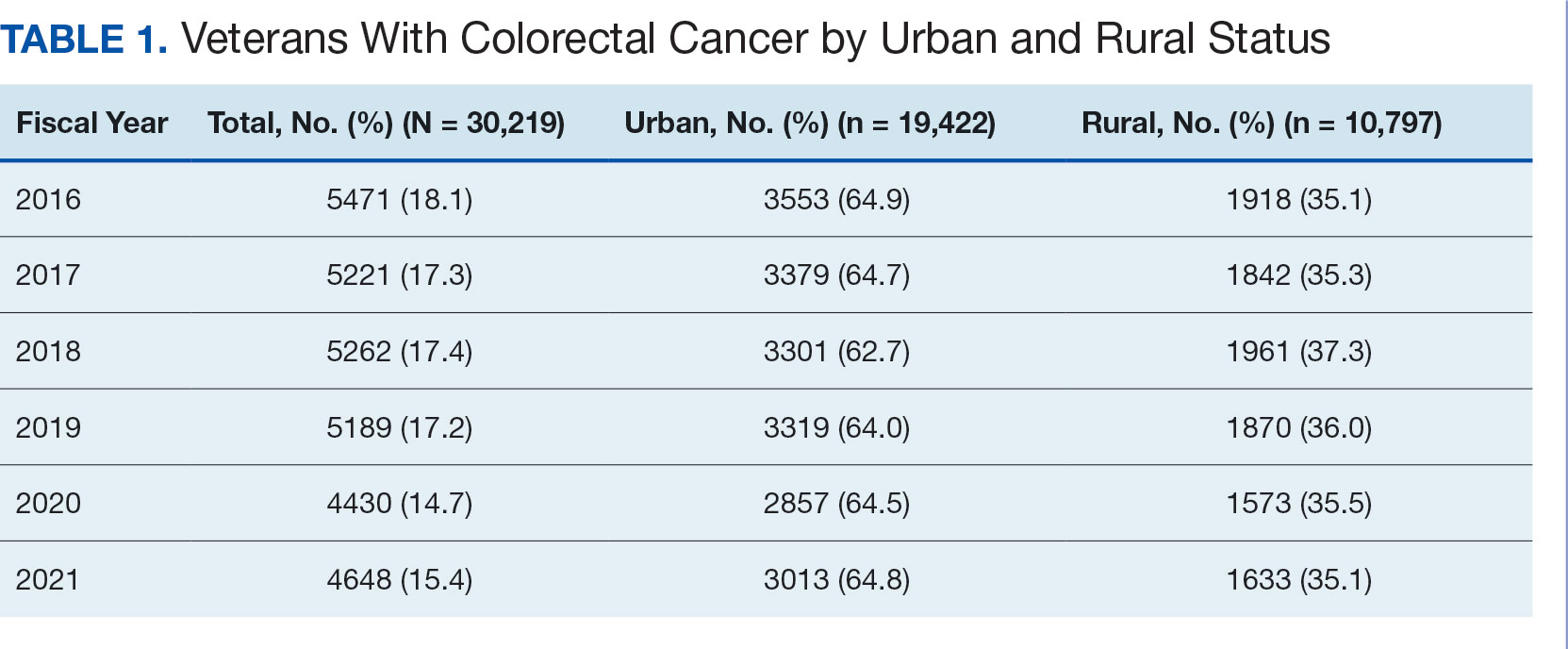

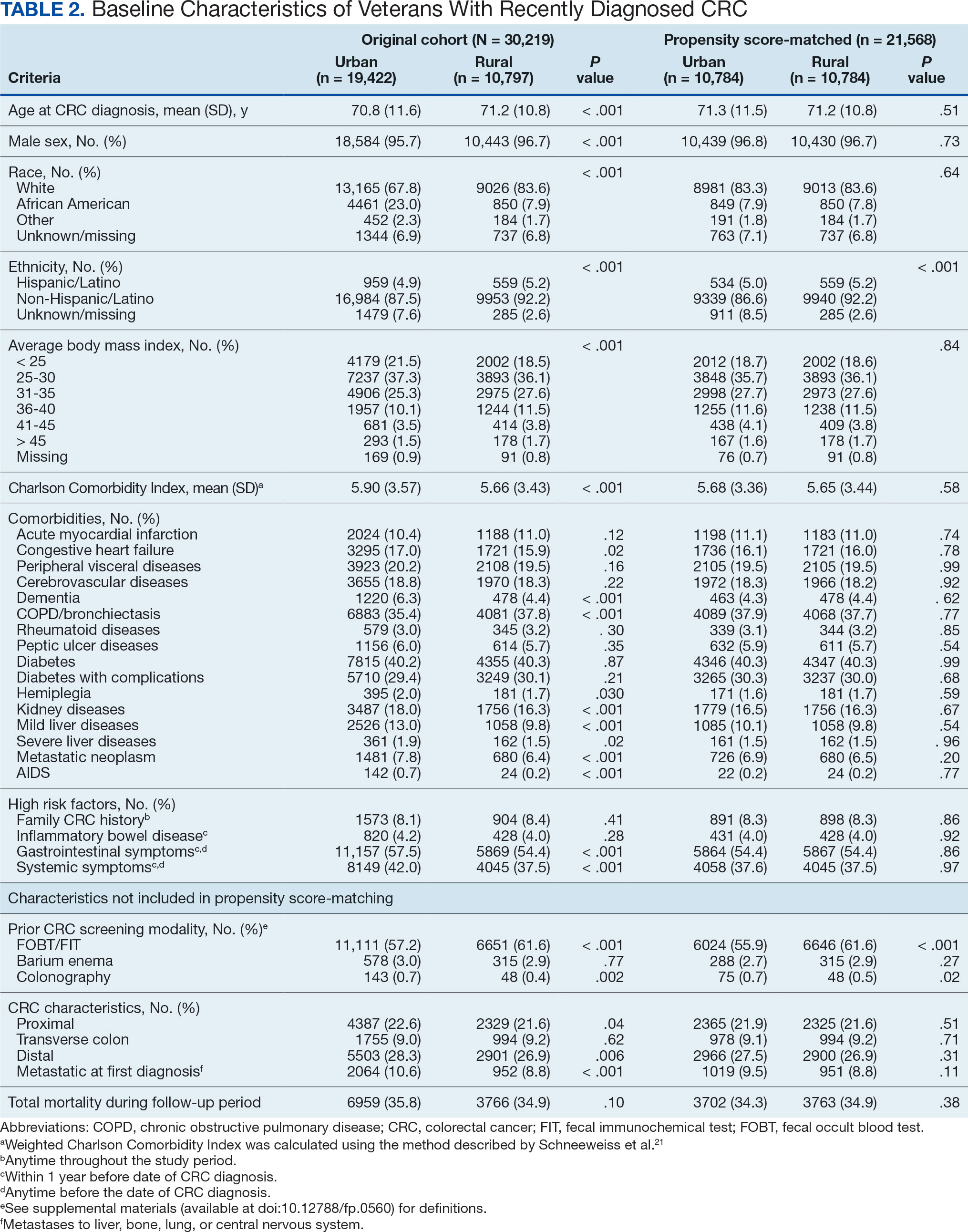

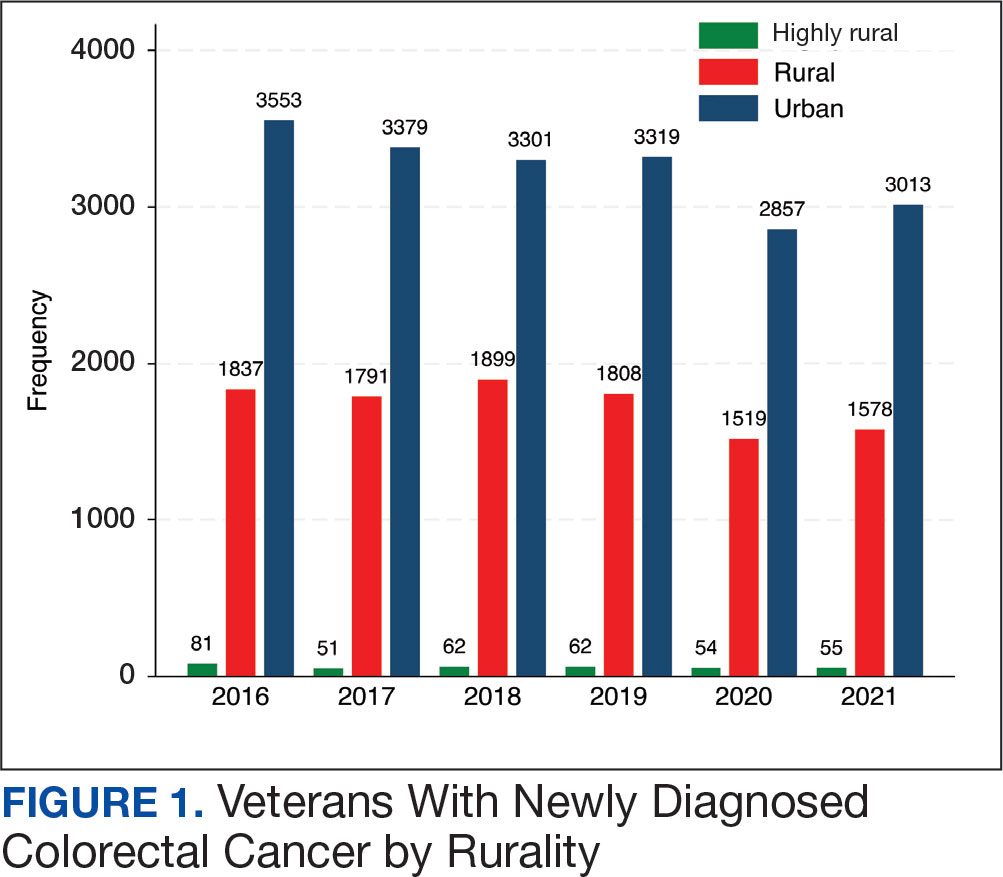

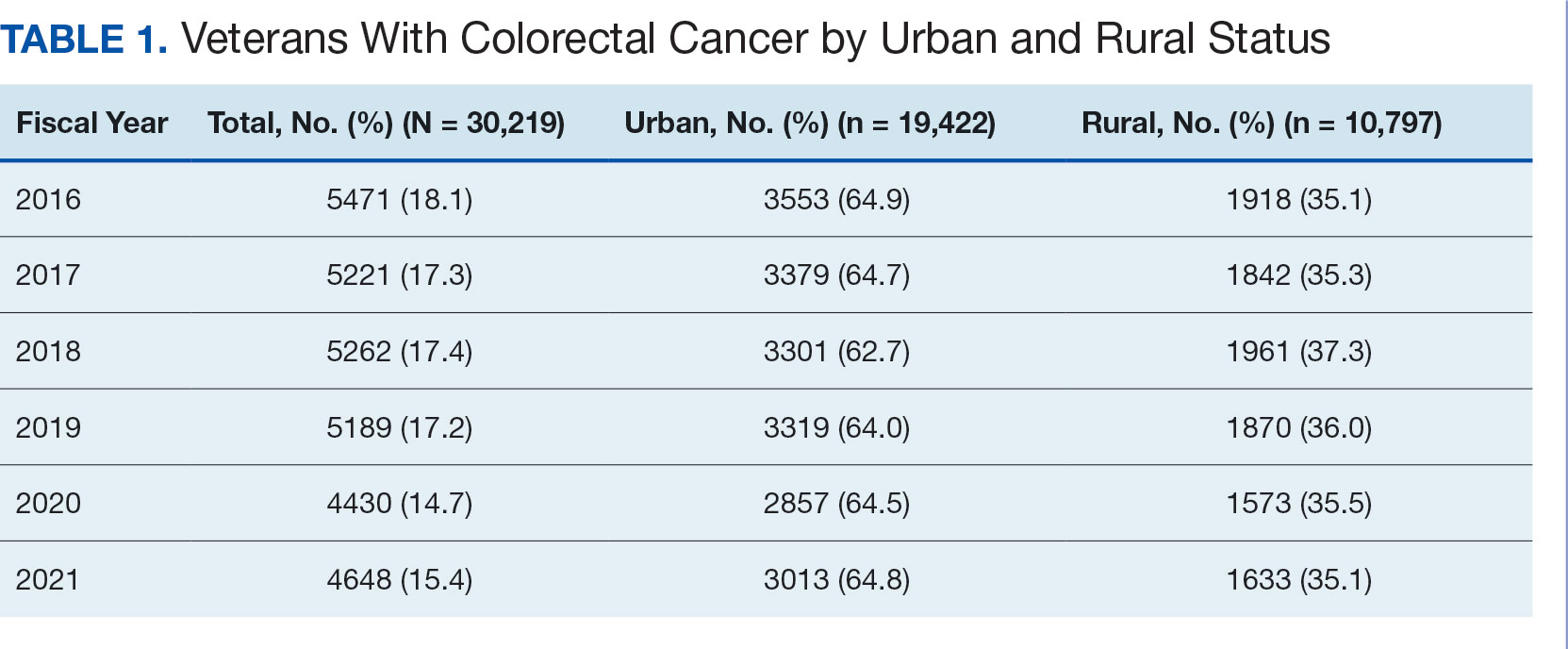

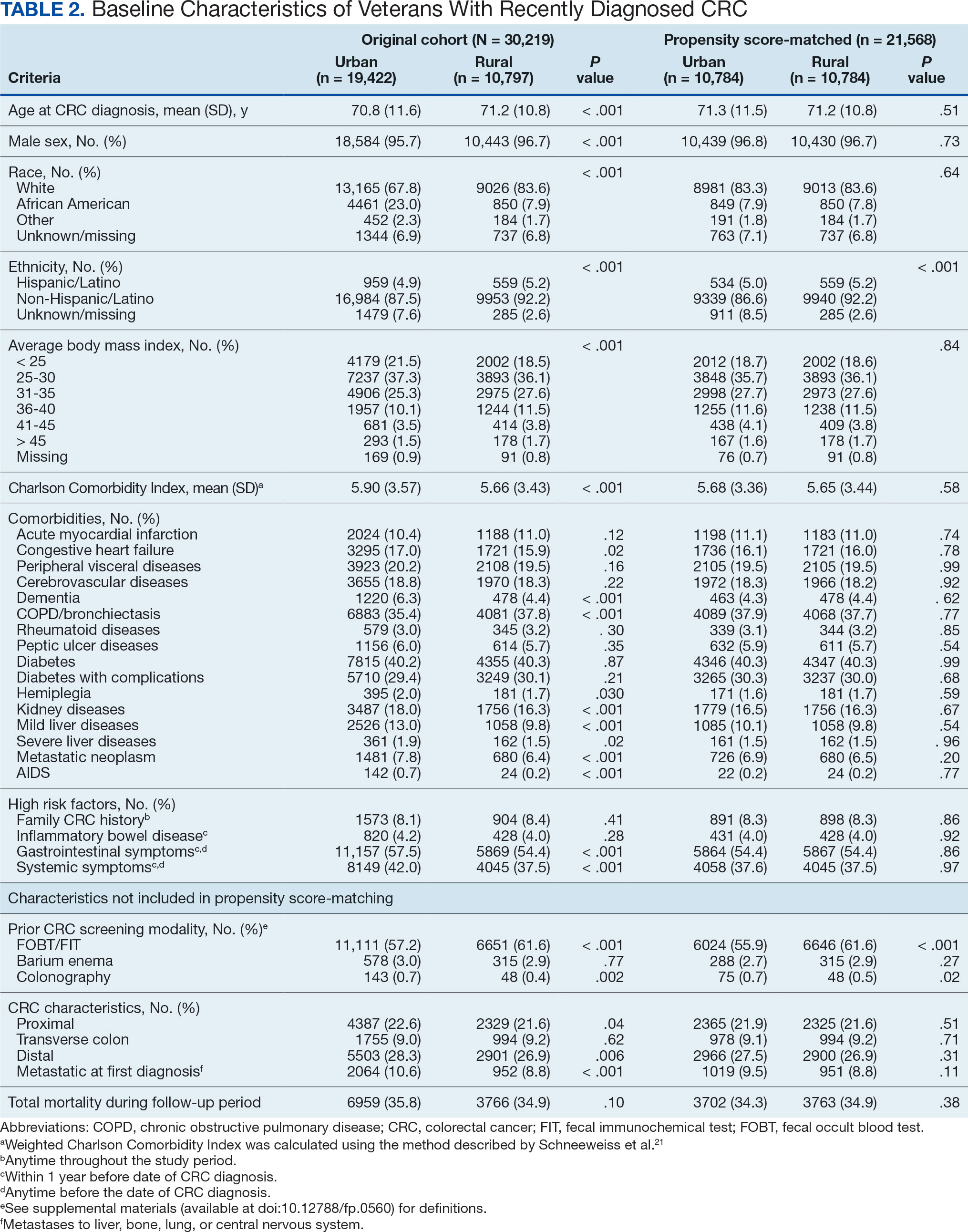

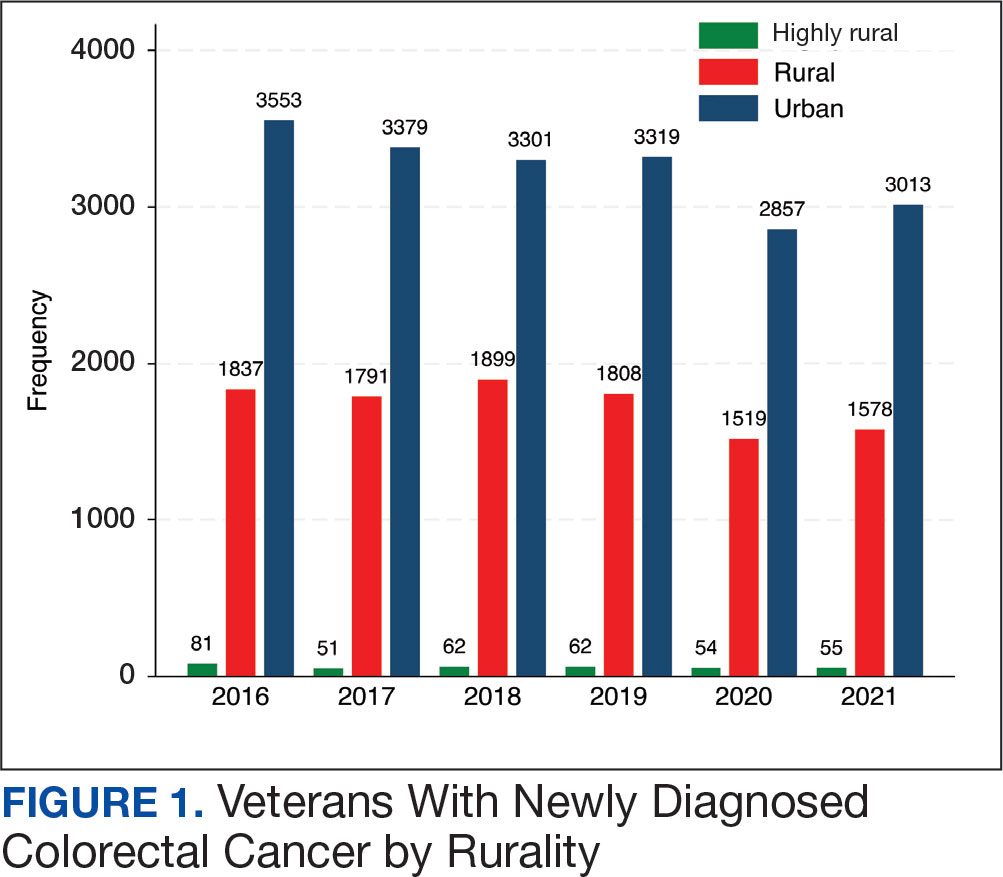

After excluding 49 patients (Supplemental materials, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0560), we identified 30,219 veterans with newly diagnosed CRC between FY 2016 to 2021 (Table 1). Of these, 19,422 (64.3%) resided in urban areas and 10,797 (35.7%) resided in rural areas (Table 2). The mean (SD) duration from the first CRC diagnosis to death or study end was 832 (640) days, and the median (IQR) was 723 (246–1330) days. Overall, incident CRC diagnoses were numerically highest in FY 2016 and lowest in FY 2020 (Figure 1). Patients with CRC in rural areas vs urban areas were significantly older (mean, 71.2 years vs 70.8 years, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be male (96.7% vs 95.7%, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be White (83.6% vs 67.8%, respectively; P < .001) and more likely to be non-Hispanic (92.2% vs 87.5%, respectively; P < .001). In terms of general health, rural veterans with CRC were more likely to be overweight or obese (81.5% rural vs 78.5% urban; P < .001) but had fewer mean comorbidities as measured by CCI (5.66 rural vs 5.90 urban; P < .001). A higher proportion of rural veterans with CRC had received stool-based (fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test) CRC screening tests (61.6% rural vs 57.2% urban; P < .001). Fewer rural patients presented with systemic symptoms or signs within 1 year of CRC diagnosis (54.4% rural vs 57.5% urban, P < .001). Among urban patients with CRC, 6959 (35.8%) deaths were observed, compared with 3766 (34.9%) among rural patients (P = .10).

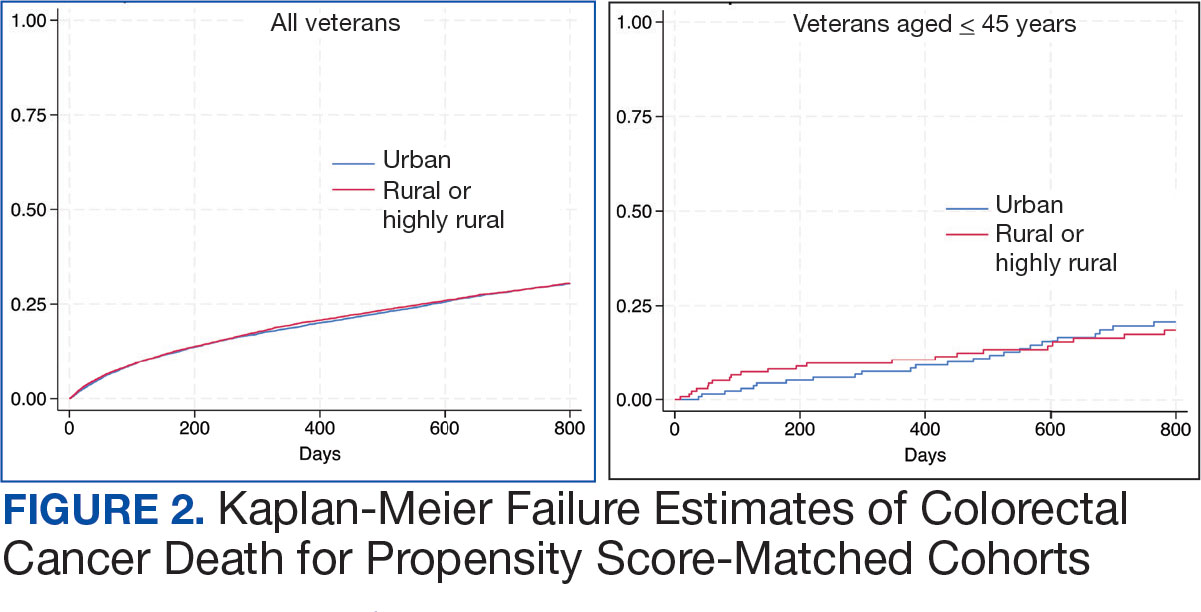

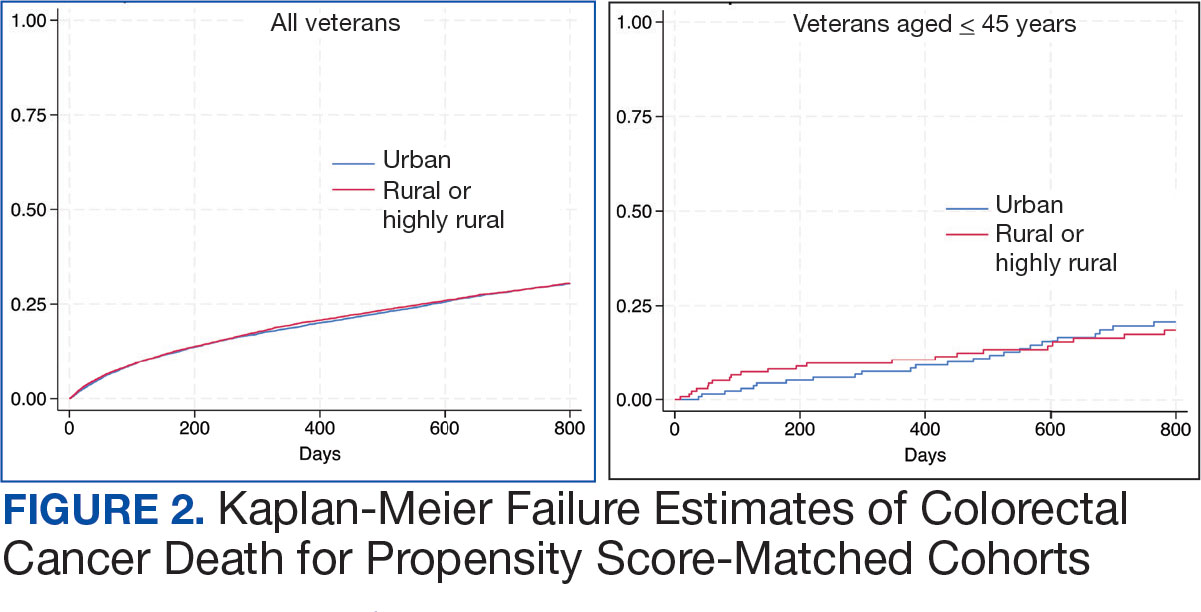

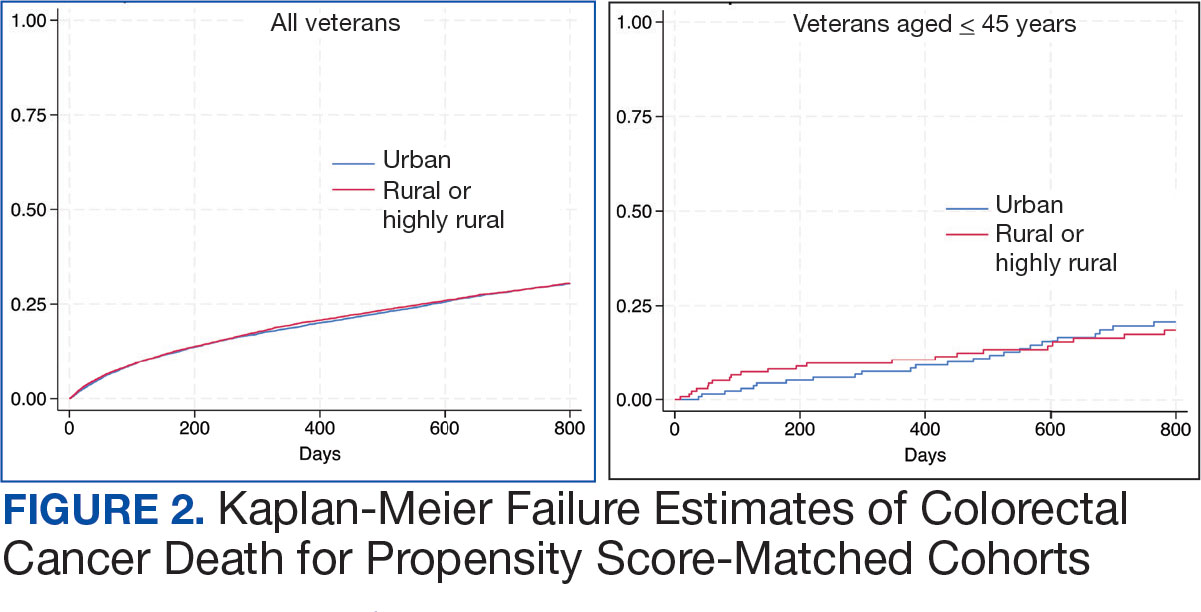

There were 21,568 PS-matched veterans: 10,784 in each group. In the PS-matched cohort, baseline characteristics were similar between veterans in urban and rural communities, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and comorbidities. Among rural patients with CRC, 3763 deaths (34.9%) were observed compared with 3702 (34.3%) among urban veterans. There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban CRC residents (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06; P = .53) (Figure 2).

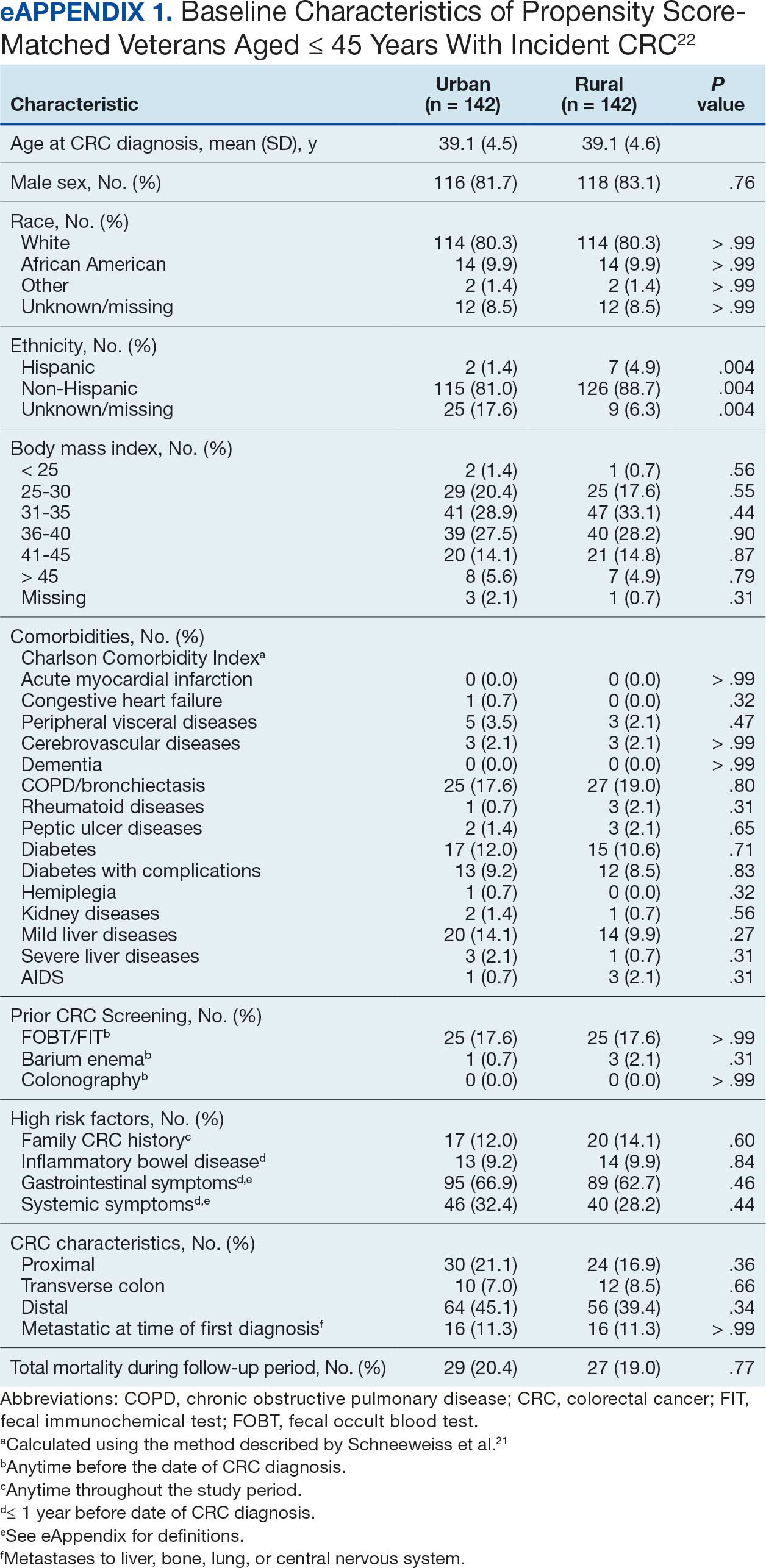

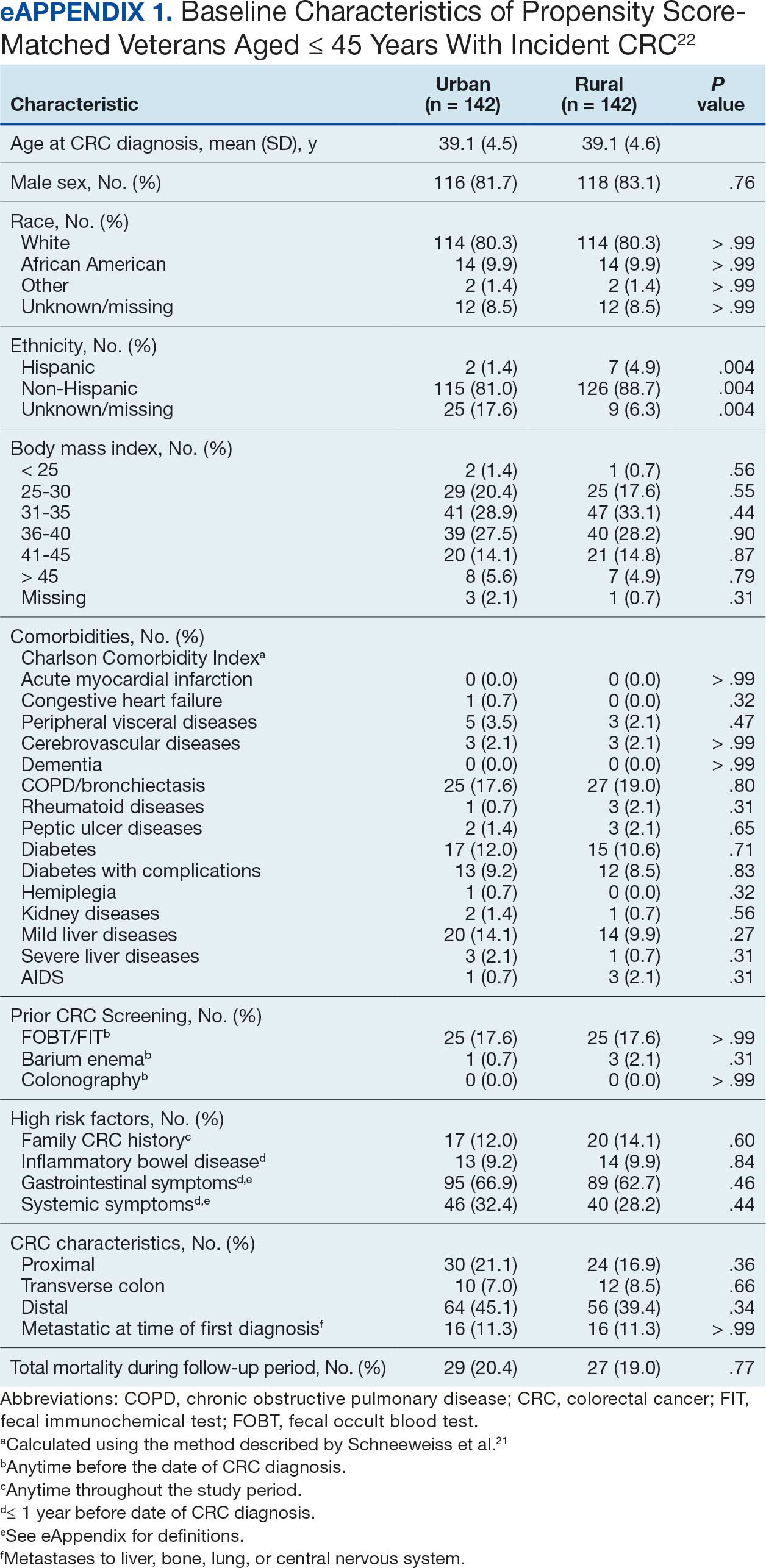

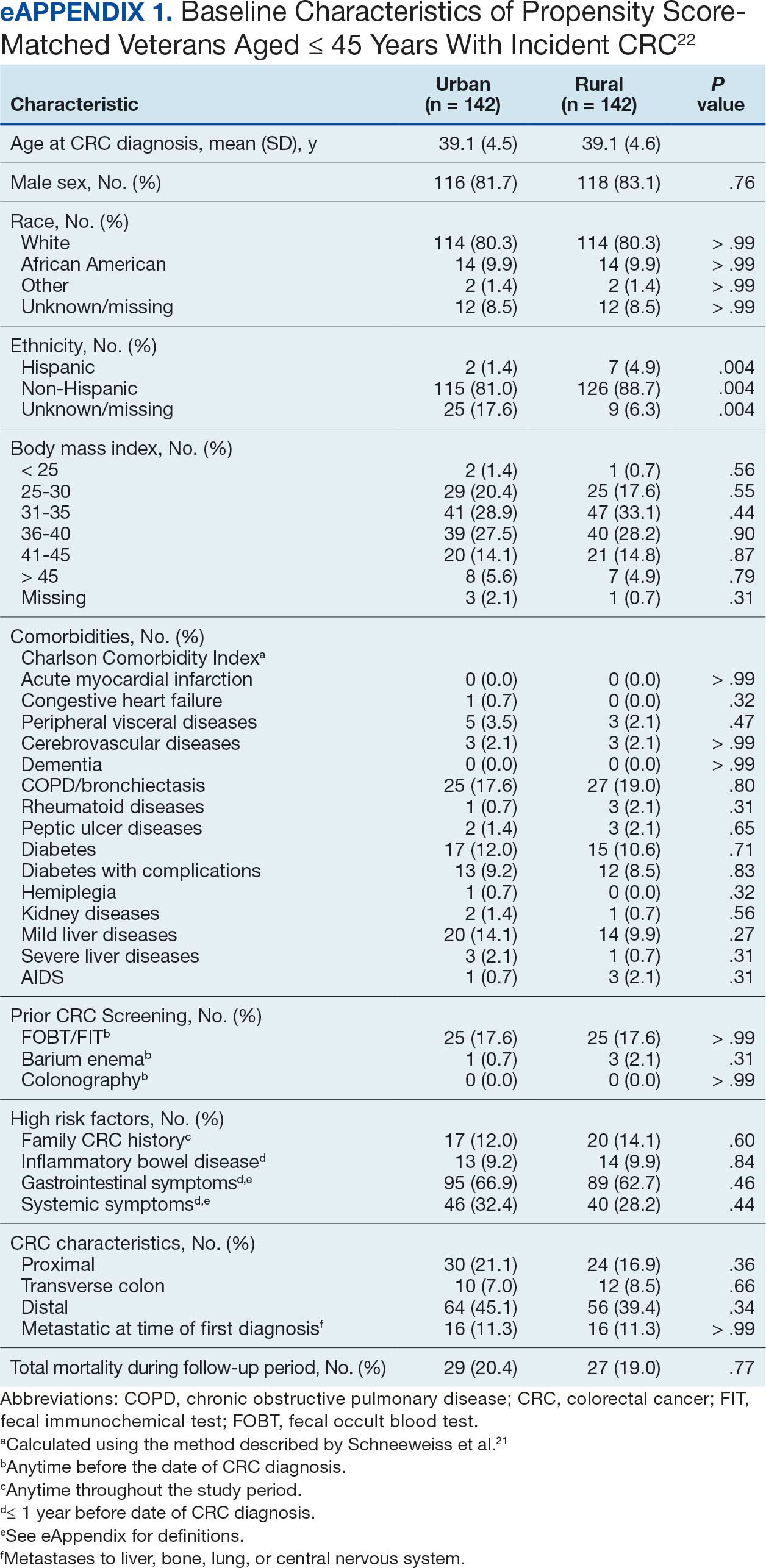

Among veterans aged ≤ 45 years, 551 were diagnosed with CRC (391 urban and 160 rural). We PS-matched 142 pairs of urban and rural veterans without residual differences in baseline characteristics (eAppendix 1). There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.57-1.63; P = .90) (Figure 2). Similarly, no difference in mortality was observed adjusting for PS between all rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.67-1.59; P = .88).

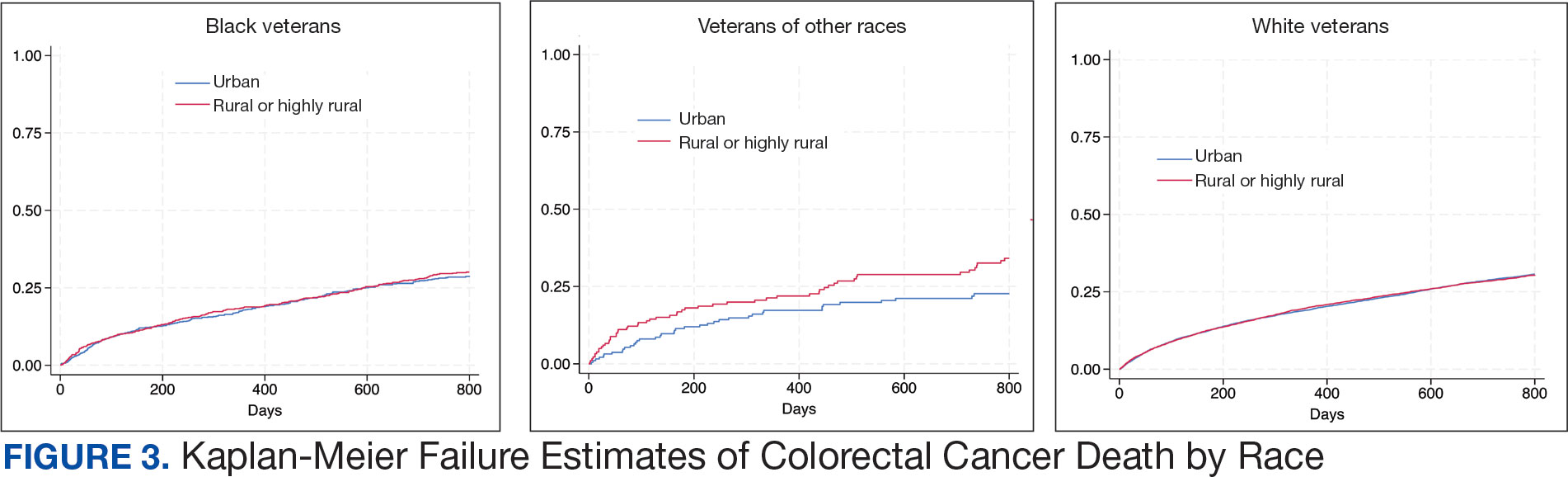

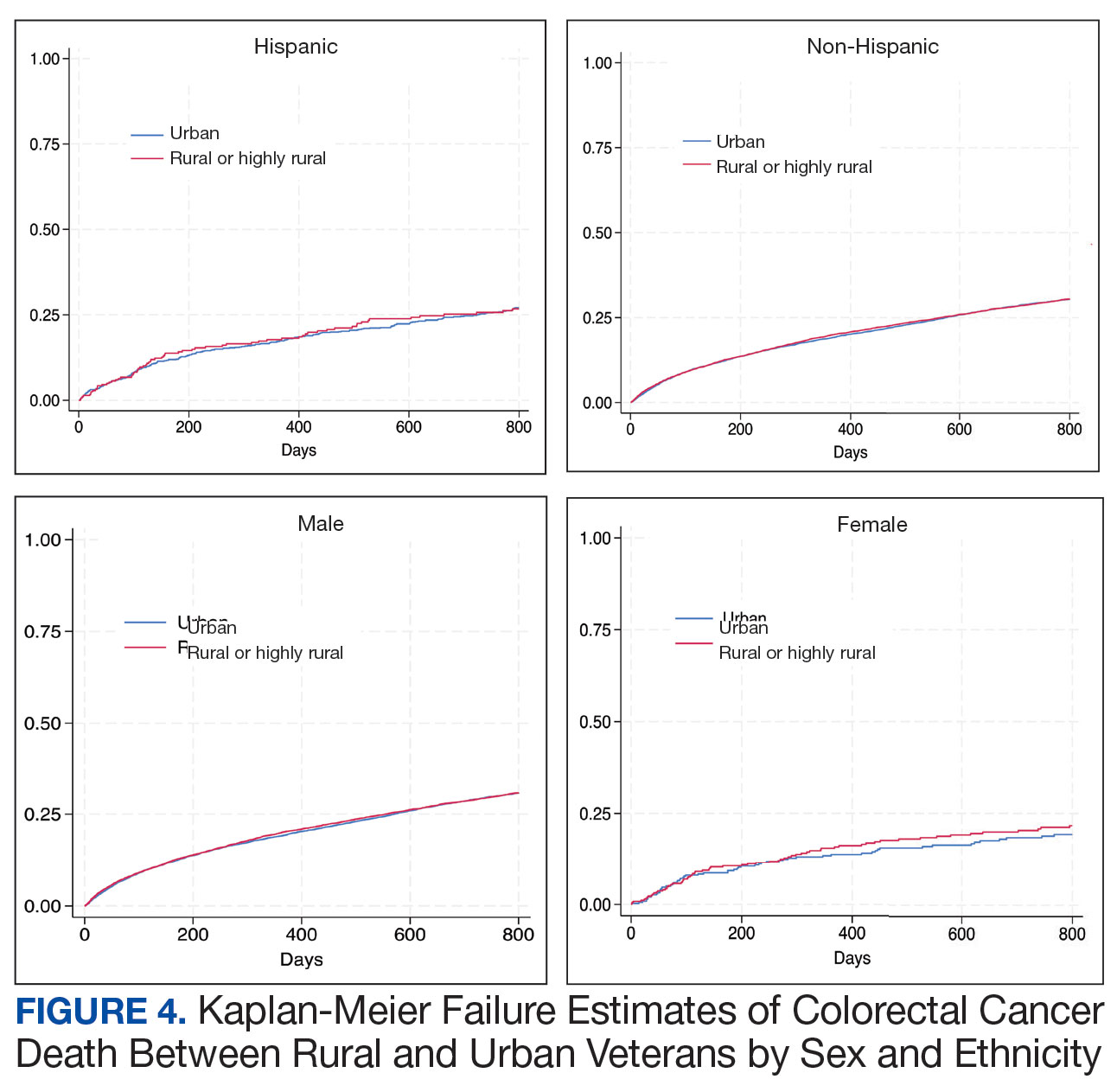

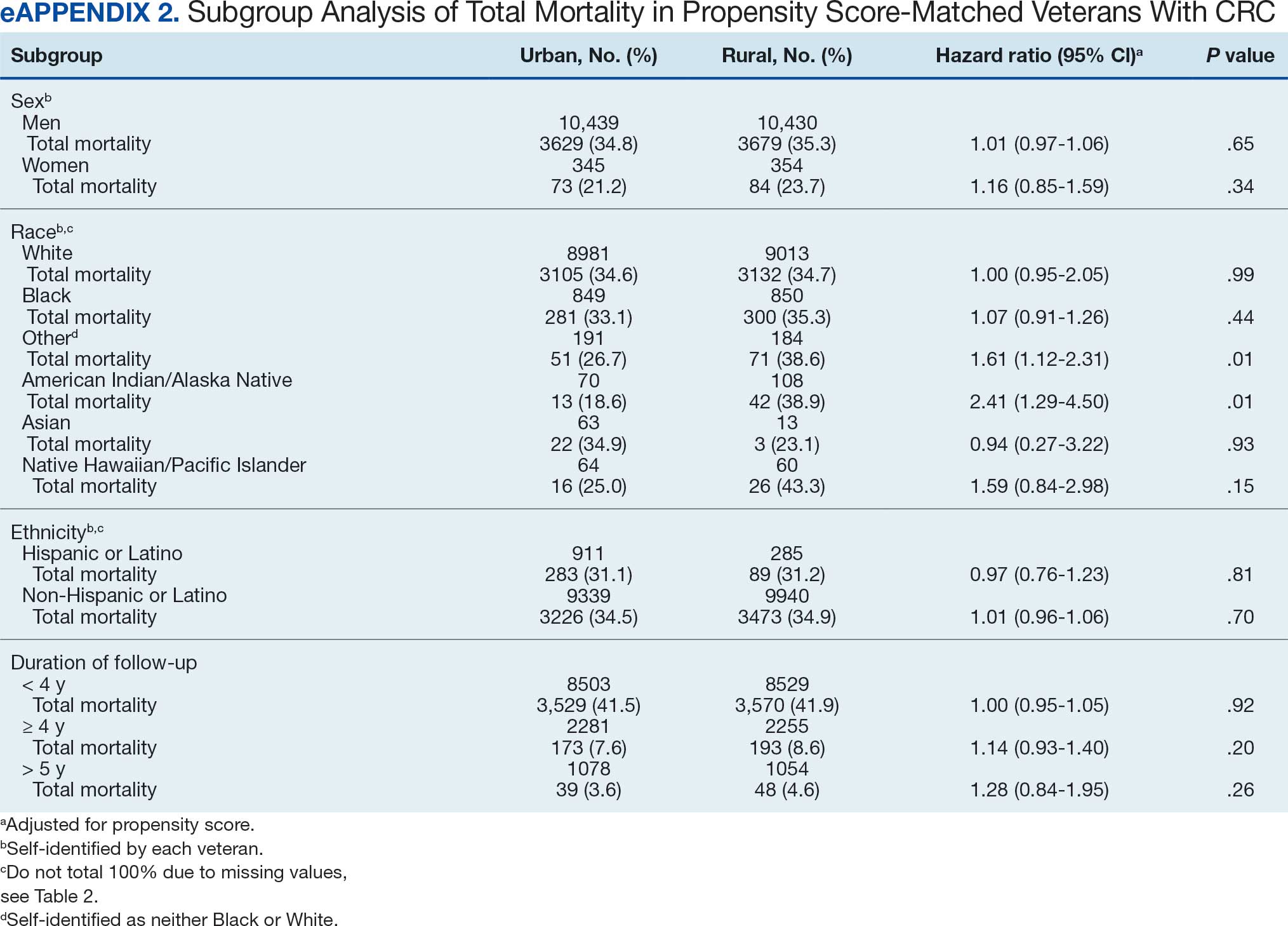

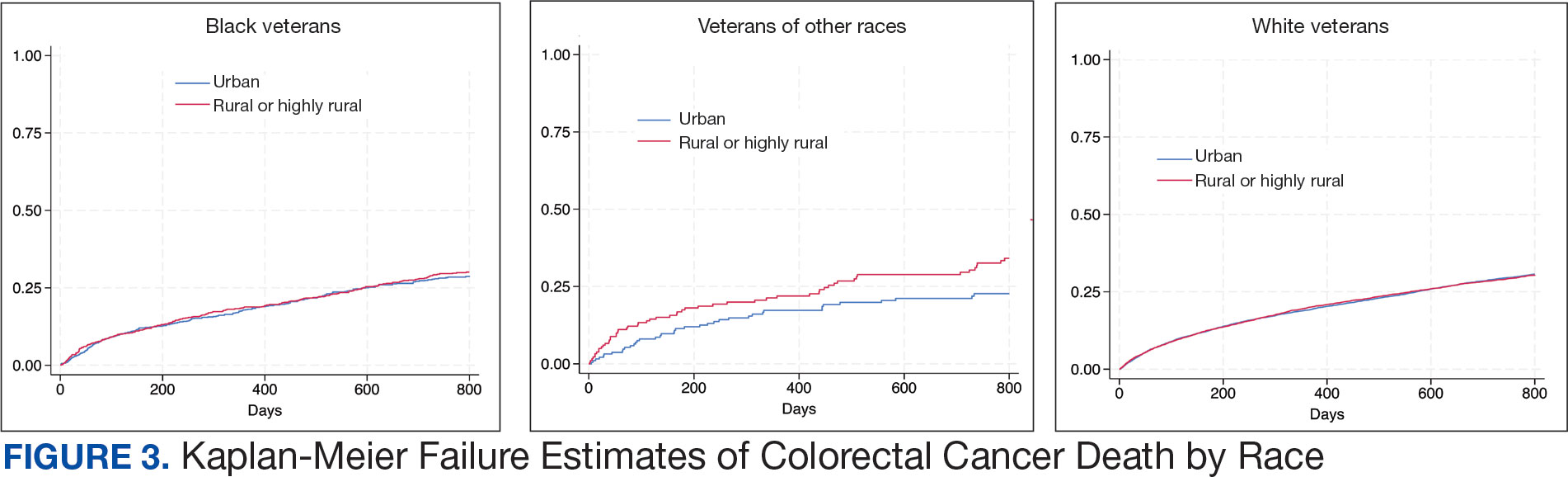

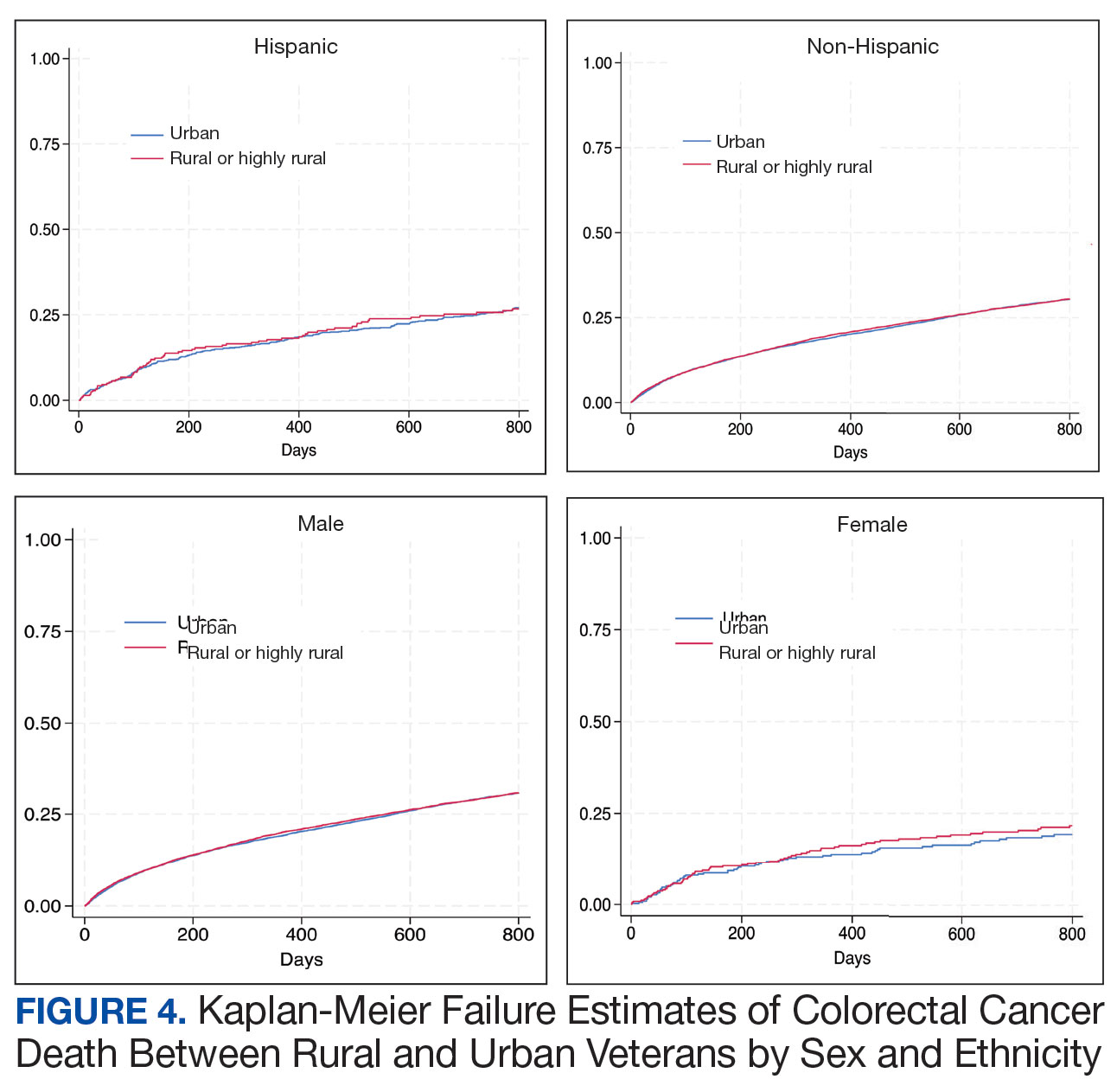

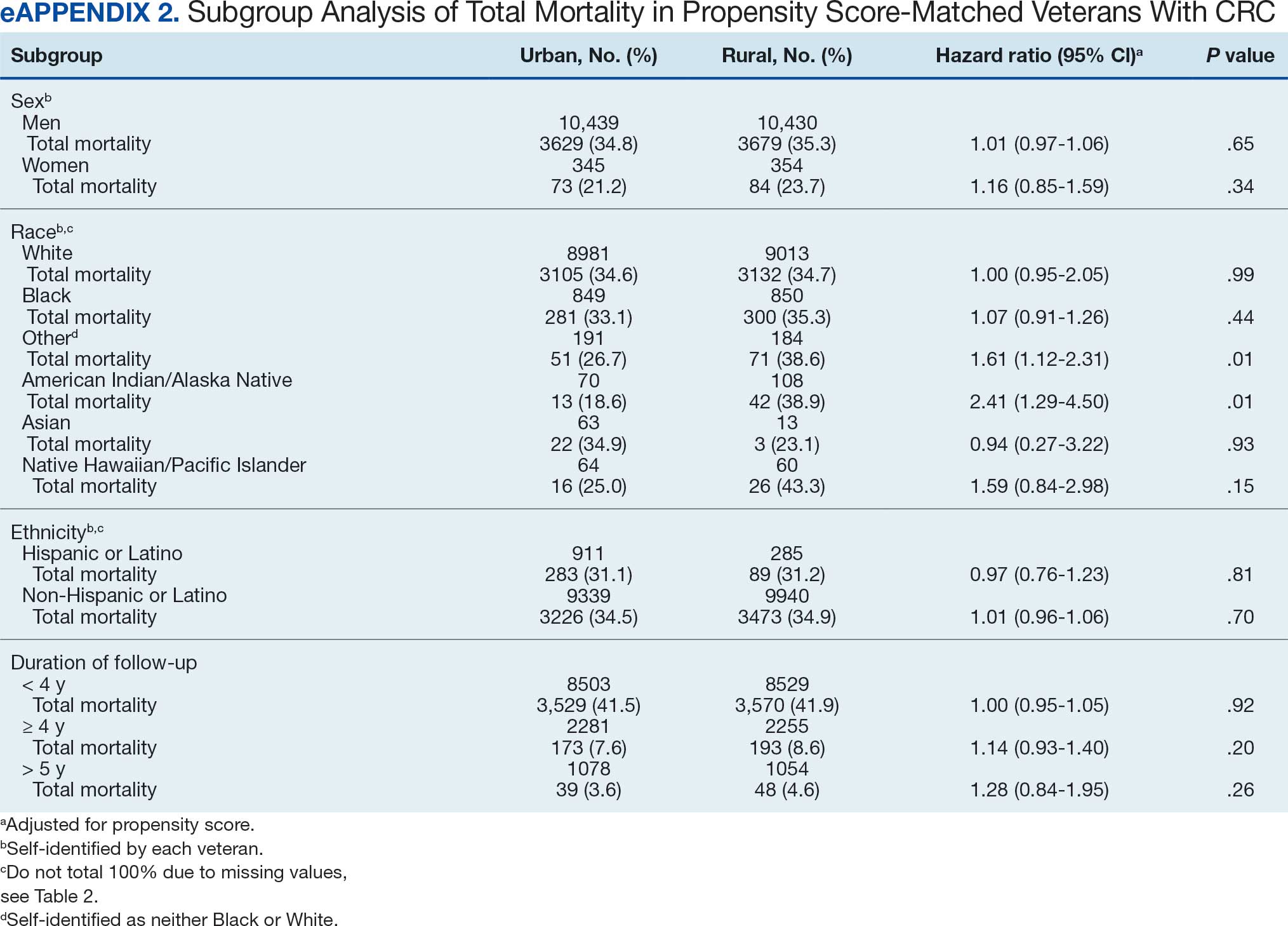

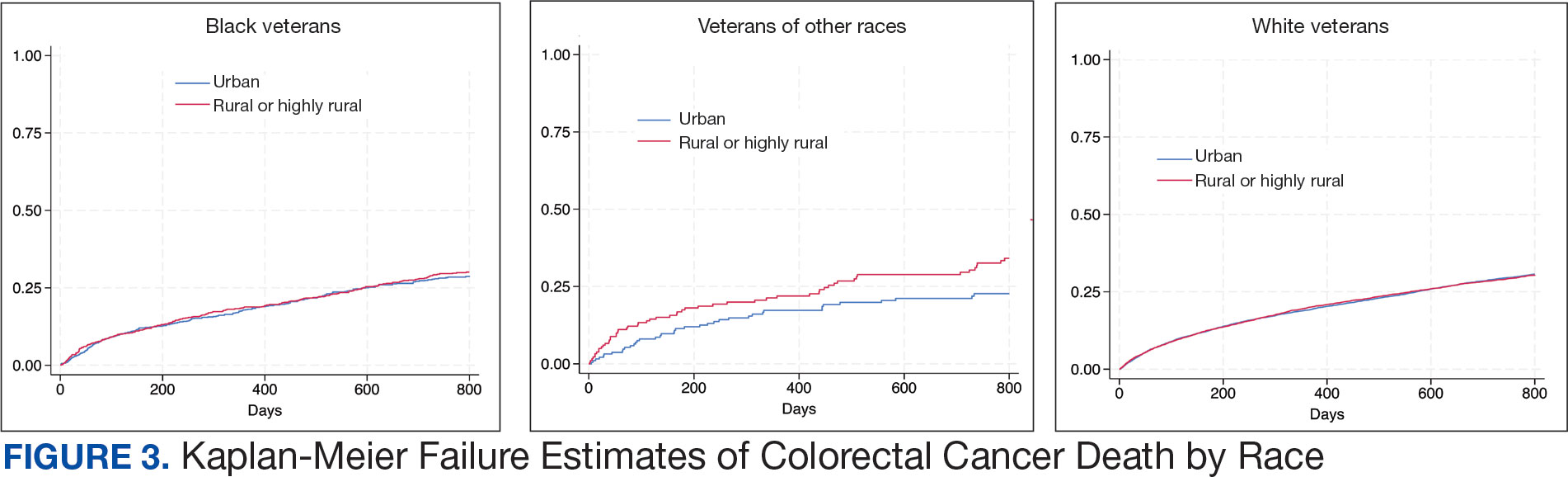

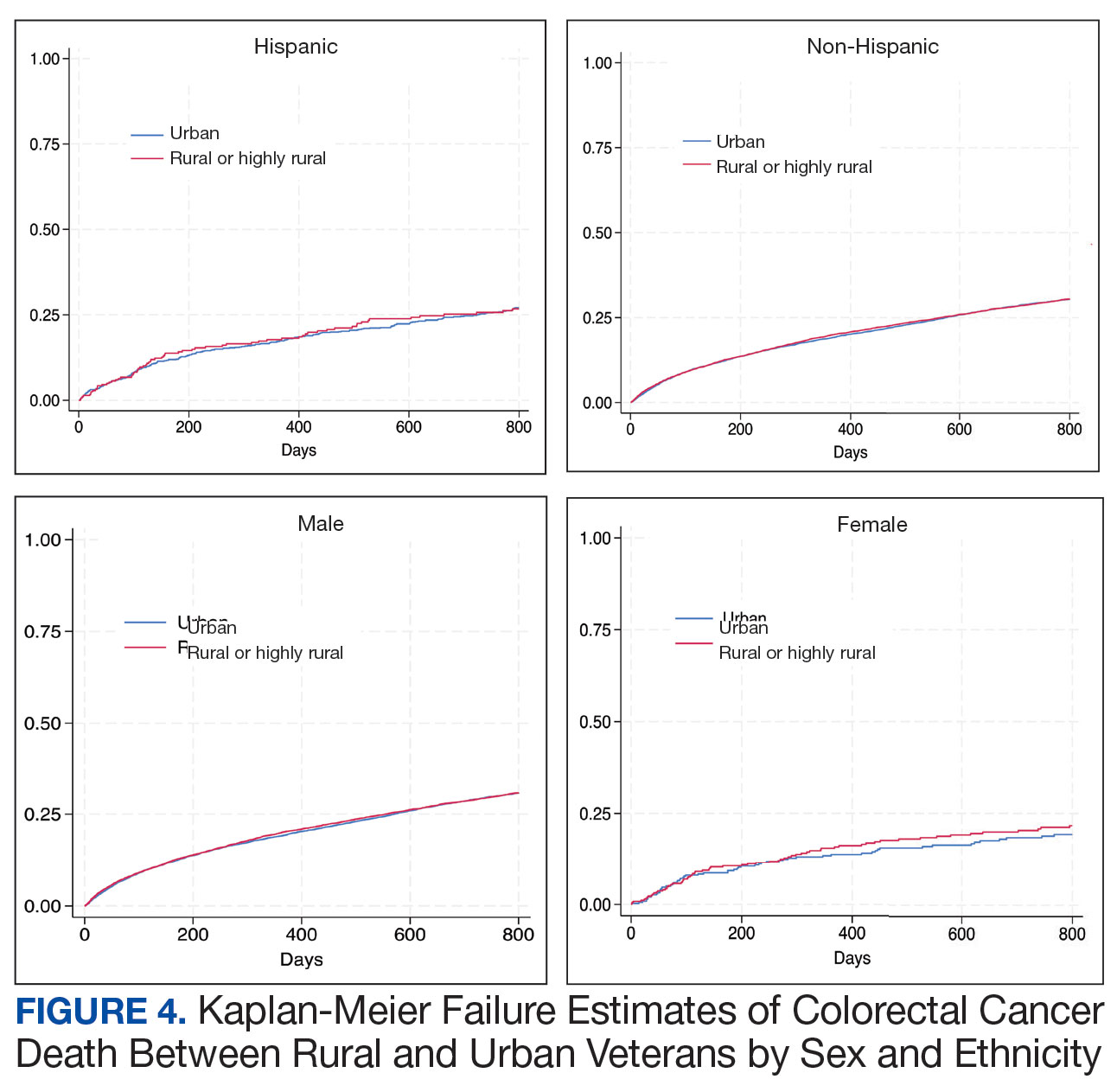

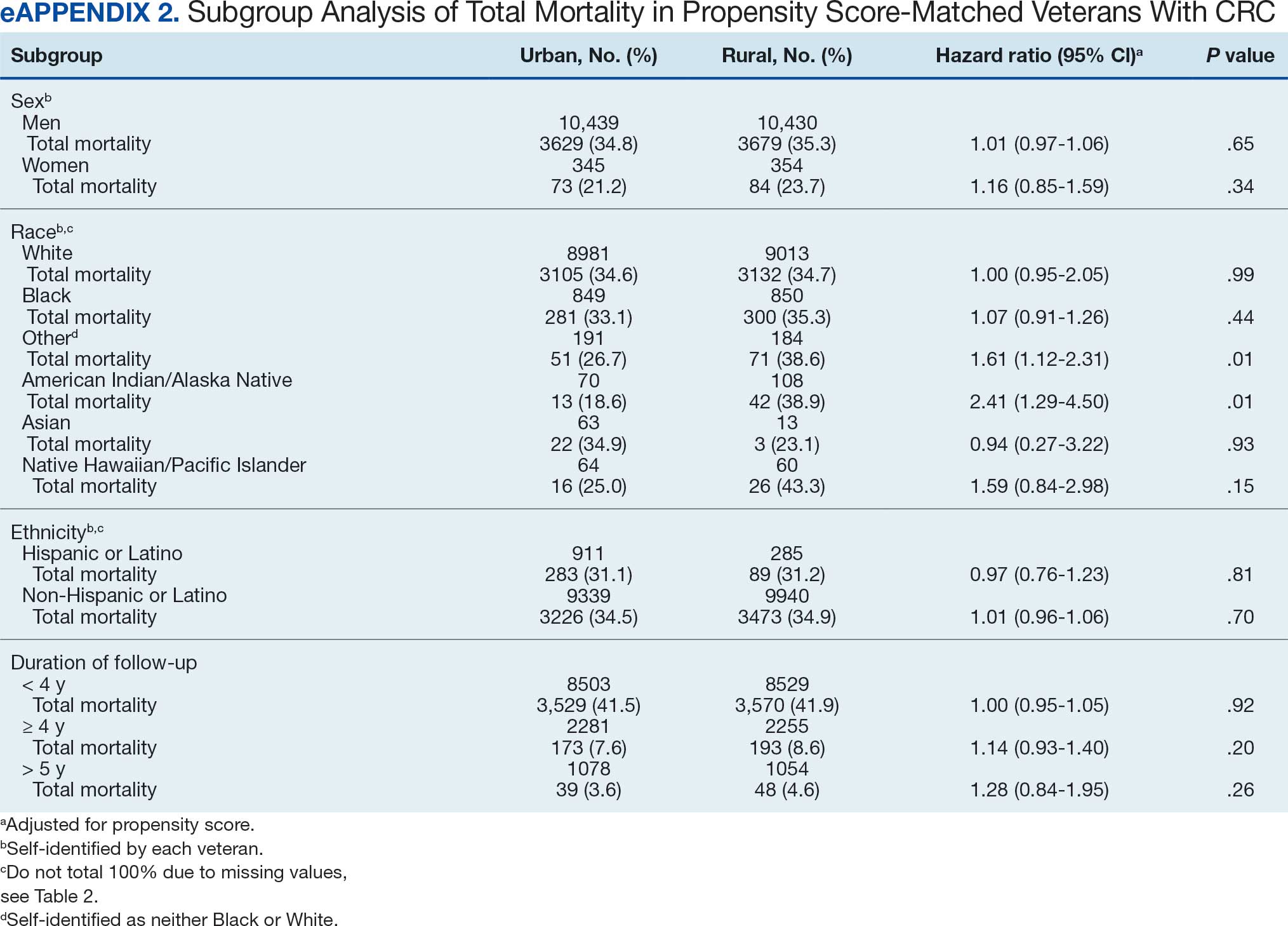

There was no difference in total mortality between rural and urban veterans in any subgroup except for American Indian or Alaska Native veterans (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006) (eAppendix 2).

Discussion

This study examined characteristics of patients with CRC between urban and rural areas among veterans who were VHA patients. Similar to other studies, rural veterans with CRC were older, more likely to be White, and were obese, but exhibited fewer comorbidities (lower CCI and lower incidence of congestive heart failure, dementia, hemiplegia, kidney diseases, liver diseases and AIDS, but higher incidence of chronic obstructive lung disease).8,16 The incidence of CRC in this study population was lowest in FY 2020, which was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is attributed to COVID-19 pandemic disruption of health services.24 The overall mortality in this study was similar to rates reported in other studies from the VA Central Cancer Registry.4 In the PS-matched cohort, where baseline characteristics were similar between urban and rural patients with CRC, we found no disparities in CRC-specific mortality between veterans in rural and urban areas. Additionally, when analysis was restricted to veterans aged ≤ 45 years, the results remained consistent.

Subgroup analyses showed no significant difference in mortality between rural and urban areas by sex, race or ethnicity, except rural American Indian or Alaska Native veterans who had double the mortality of their urban counterparts (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006). This finding is difficult to interpret due to the small number of events and the wide CI. While with a Bonferroni correction the adjusted P value was .08, which is not statistically significant, a previous study found that although CRC incidence was lower overall in American Indian or Alaska Native populations compared to non-Hispanic White populations, CRC incidence was higher among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals in some areas such as Alaska and the Northern Plains.25,26 Studies have noted that rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations experience greater poverty, less access to broadband internet, and limited access to care, contributing to poorer cancer outcomes and lower survival.27 Thus, the finding of disparity in mortality between rural and urban American Indian or Alaska Native veterans warrants further study.

Other studies have raised concerns that CRC disproportionately affects adults in rural areas with higher mortality rates.14-16 These disparities arise from sociodemographic factors and modifiable risk factors, including physical activity, dietary patterns, access to cancer screening, and gaps in quality treatment resources.16,28 These factors operate at multiple levels: from individual, local health system, to community and policy.2,27 For example, a South Carolina study (1996–2016) found that residents in rural areas were more likely to be diagnosed with advanced CRC, possibly indicating lower rates of CRC screening in rural areas. They also had higher likelihood of death from CRC.15 However, the study did not include any clinical parameters, such as comorbidities or obesity. A statewide, population-based study in Utah showed that rural men experienced a lower CRC survival in their unadjusted analysis.16 However, the study was small, with only 3948 urban and 712 rural residents. Additionally, there was no difference in total mortality in the whole cohort (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07) or in CRC-specific death (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.08). A nationwide study also showed that CRC mortality rates were 8% higher in nonmetropolitan or rural areas than in the most urbanized areas containing large metropolitan counties.29 However, this study did not include descriptions of clinical confounders, such as comorbidities, making it difficult to ascertain whether the difference in CRC mortality was due to rurality or differences in baseline risk characteristics.

In this study, the lack of CRC-specific mortality disparities may be attributed to the structures and practices of VHA health care. Recent studies have noted that mortality of several chronic medical conditions treated at the VHA was lower than at non-VHA hospitals.30,31 One study that measured the quality of nonmetastatic CRC care based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines showed that > 72% of VHA patients received guideline-concordant care for each diagnostic and therapeutic measure, except for follow-up colonoscopy timing, which appear to be similar or superior to that of the private sector.30,32,33 Some of the VA initiative for CRC screening may bypass the urban-rurality divide such as the mailed fecal immunochemical test program for CRC. This program was implemented at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to avoid disruptions of medical care.34 Rural patients are more likely to undergo fecal immunochemical testing when compared to urban patients in this data. Beyond clinical care, the VHA uses processes to tackle social determinants of health such as housing, food security, and transportation, promoting equal access to health care, and promoting cultural competency among HCPs.35-37

The results suggest that solutions to CRC disparities between rural and urban areas need to consider known barriers to rural health care, including transportation, diminished rural health care workforce, and other social determinants of health.9,10,27,38 VHA makes considerable efforts to provide equitable care to all enrolled veterans, including specific programs for rural veterans, including ongoing outreach.39 This study demonstrated lack of disparity in CRC-specific mortality in veterans receiving VHA care, highlighting the importance of these efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

This study used the VHA cohort to compare patient characteristics and mortality between patients with CRC residing in rural and urban areas. The study provides nationwide perspectives on CRC across the geographical spectrum and used a longitudinal cohort with prolonged follow-up to account for comorbidities.

However, the study compared a cohort of rural and urban veterans enrolled in the VHA; hence, the results may not reflect CRC outcomes in veterans without access to VHA care. Rurality has been independently associated with decreased likelihood of meeting CRC screening guidelines among veterans and military service members.38 This study lacked sufficient information to compare CRC staging or treatment modalities among veterans. Although the data cannot identify CRC stage, the proportions of patients with metastatic CRC at diagnosis and CRC location were similar between groups. The study did not have information on their care outside of VHA setting.

This study could not ascertain whether disparities existed in CRC treatment modality since rural residence may result in referral to community-based CRC care, which did not appear in the data. To address these limitations, we used death from any cause as the primary outcome, since death is a hard outcome and is not subject to ascertainment bias. The relatively short follow-up time is another limitation, though subgroup analysis by follow-up did not show significant differences. Despite PS matching, residual unmeasured confounding may exist between urban and rural groups. The predominantly White, male VHA population with high CCI may limit the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

Rural VHA enrollees had similar survival rates after CRC diagnosis compared to their urban counterparts in a PS-matched analysis. The VHA models of care—including mailed CRC screening tools, several socioeconomic determinants of health (housing, food security, and transportation), and promoting equal access to health care, as well as cultural competency among HCPs—HCPs—may help alleviate disparities across the rural-urban spectrum. The VHA should continue efforts to enroll veterans and provide comprehensive coordinated care in community partnerships.

- Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254. doi:10.3322/caac.21772

- Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer and intervention framework and strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):354-367. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.029

- Murphy G, Devesa SS, Cross AJ, Inskip PD, McGlynn KA, Cook MB. Sex disparities in colorectal cancer incidence by anatomic subsite, race and age. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(7):1668-75. doi:10.1002/ijc.25481

- Zullig LL, Smith VA, Jackson GL, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics from the Veterans Affairs central cancer registry. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15(4):e199-e204. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2016.04.005

- Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 2021. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews:Chapter 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570917/

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8). doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

- Hines R, Markossian T, Johnson A, Dong F, Bayakly R. Geographic residency status and census tract socioeconomic status as determinants of colorectal cancer outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e63-e71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301572

- Cauwels J. The many barriers to high-quality rural health care. 2022;(9):1-32. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/CAT.22.0254

- Gong G, Phillips SG, Hudson C, Curti D, Philips BU. Higher US rural mortality rates linked to socioeconomic status, physician shortages, and lack of health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood);38(12):2003-2010. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00722

- Aboagye JK, Kaiser HE, Hayanga AJ. Rural-urban differences in access to specialist providers of colorectal cancer care in the United States: a physician workforce issue. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):537-543. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5062

- Lyckholm LJ, Hackney MH, Smith TJ. Ethics of rural health care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40(2):131-138. doi:10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00139-1

- Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341-378. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341

- Singh GK, Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:2819372. doi:10.1155/2017/2819372

- Adams SA, Zahnd WE, Ranganathan R, et al. Rural and racial disparities in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in South Carolina, 1996 - 2016. J Rural Health. 2022;38(1):34-39. doi:10.1111/jrh.12580

- Rogers CR, Blackburn BE, Huntington M, et al. Rural- urban disparities in colorectal cancer survival and risk among men in Utah: a statewide population-based study. Cancer Causes Control. 2020;31(3):241-253. doi:10.1007/s10552-020-01268-2

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), VA HSR RES 13-457. https://vincicentral.vinci.med.va.gov [Source not verified]

- US Department of Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center. VIReC Research User Guide: PSSG Geocoded Enrollee Files, 2015 Edition. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Information Resource Center; May. 2016. [source not verified]

- Goldsmith HF, Puskin DS, Stiles DJ. Improving the operational definition of “rural areas” for federal programs. US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/pdf/improving-the-operational-definition-of-rural-areas.pdf

- Adams MA, Kerr EA, Dominitz JA, et al. Development and validation of a new ICD-10-based screening colonoscopy overuse measure in a large integrated healthcare system: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;32(7):414-424. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014236

- Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in Medicare populations. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(4):1103-1120. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00165

- Becker S, Ichino A. Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. The Stata Journal. 2002;2(4):358-377.

- Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Statistical software components. Revised February 1, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2024. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Cao J, Zhang S. Multiple Comparison Procedures. JAMA. 2014;312(5):543-544. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.9440

- Gopalani SV, Janitz AE, Martinez SA, et al. Trends in cancer incidence among American Indians and Alaska Natives and Non-Hispanic Whites in the United States, 1999-2015. Epidemiology. 2020;31(2):205-213. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000001140

- Zahnd WE, Murphy C, Knoll M, et al. The intersection of rural residence and minority race/ethnicity in cancer disparities in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4). doi:10.3390/ijerph18041384

- Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):992-997. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0092

- Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US cancer mortality: part i-all cancers and lung cancer and part iicolorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;2011:107497. doi:10.1155/2011/107497

- Jackson GL, Melton LD, Abbott DH, et al. Quality of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3176-3181. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7948

- Yoon J, Phibbs CS, Ong MK, et al. Outcomes of veterans treated in Veterans Affairs hospitals vs non-Veterans Affairs hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2345898. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.45898

- Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, Adams J, Emanuel EJ, Kahn KL. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: how can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(4):626-634. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365

- Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570-1595. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002

- Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among Veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4). doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

- Yehia BR, Greenstone CL, Hosenfeld CB, Matthews KL, Zephyrin LC. The role of VA community care in addressing health and health care disparities. Med Care. 2017;55(Suppl 9 suppl 2):S4-S5. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000768

- Wright BN, MacDermid Wadsworth S, Wellnitz A, Eicher- Miller HA. Reaching rural veterans: a new mechanism to connect rural, low-income US Veterans with resources and improve food security. J Public Health (Oxf). 2019;41(4):714-723. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdy203

- Nelson RE, Byrne TH, Suo Y, et al. Association of temporary financial assistance with housing stability among US veterans in the supportive services for veteran families program. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037047. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37047

- McDaniel JT, Albright D, Lee HY, et al. Rural–urban disparities in colorectal cancer screening among military service members and Veterans. J Mil Veteran Fam Health. 2019;5(1):40-48. doi:10.3138/jmvfh.2018-0013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. The rural veteran outreach toolkit. Updated February 12, 2025. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/partners/toolkit.asp

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with an estimated 52,550 deaths in 2023.1 However, the disease burden varies among different segments of the population.2 While both CRC incidence and mortality have been decreasing due to screening and advances in treatment, there are disparities in incidence and mortality across the sociodemographic spectrum including race, ethnicity, education, and income.1-4 While CRC incidence is decreasing for older adults, it is increasing among those aged < 55 years.5 The incidence of CRC in adults aged 40 to 54 years has increased by 0.5% to 1.3% annually since the mid-1990s.6 The US Preventive Services Task Force now recommends starting CRC screening at age 45 years for asymptomatic adults with average risk.7

Disparities also exist across geographical boundaries and living environment. Rural Americans faces additional challenges in health and lifestyle that can affect CRC outcomes. Compared to their urban counterparts, rural residents are more likely to be older, have lower levels of education, higher levels of poverty, lack health insurance, and less access to health care practitioners (HCPs).8-10 Geographic proximity, defined as travel time or physical distance to a health facility, has been recognized as a predictor of inferior outcomes.11 These aspects of rural living may pose challenges for accessing care for CRC screening and treatment.11-13 National and local studies have shown disparities in CRC screening rates, incidence, and mortality between rural and urban populations.14-16

It is unclear whether rural/urban disparities persist under the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health care delivery model. This study examined differences in baseline characteristics and mortality between rural and urban veterans newly diagnosed with CRC. We also focused on a subpopulation aged ≤ 45 years.

Methods

This study extracted national data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) hosted in the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) environment. VINCI is an initiative to improve access to VA data and facilitate the analysis of these data while ensuring veterans’ privacy and data security.17 CDW is the VHA business intelligence information repository, which extracts data from clinical and nonclinical sources following prescribed and validated protocols. Data extracted included demographics, diagnosis, and procedure codes for both inpatient and outpatient encounters, vital signs, and vital status. This study used data previously extracted from a national cohort of veterans that encompassed all patients who received a group of commonly prescribed medications, such as statins, proton pump inhibitors, histamine-2 blockers, acetaminophen-containing products, and hydrocortisone-containing skin applications. This cohort encompassed 8,648,754 veterans, from whom 2,460,727 had encounters during fiscal years (FY) 2016 to 2021 (study period). The cohort was used to ensure that subjects were VHA patients, allowing them to adequately capture their clinical profiles.

Patients were identified as rural or urban based on their residence address at the date of their first diagnosis of CRC. The Geospatial Service Support Center (GSSC) aggregates and updates veterans’ residence address records for all enrolled veterans from the National Change of Address database. The data contain 1 record per enrollee. GSSC Geocoded Enrollee File contains enrollee addresses and their rurality indicators, categorized as urban, rural, or highly rural.18 Rurality is defined by the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) categories developed by the Department of Agriculture and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services.19 Urban areas had RUCA codes of 1.0 to 1.1, and highly rural areas had RUCA scores of 10.0. All other areas were classified as rural. Since the proportion of veterans from highly rural areas was small, we included residents from highly rural areas in the rural residents’ group.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All veterans newly diagnosed with CRC from FY 2016 to 2021 were included. We used the ninth and tenth clinical modification revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) to define CRC diagnosis (Supplemental materials).4,20 To ensure that patients were newly diagnosed with CRC, this study excluded patients with a previous ICD-9-CM code for CRC diagnosis since FY 2003.

Comorbidities were identified using diagnosis and procedure codes from inpatient and outpatient encounters, which were used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) at the time of CRC diagnosis using the weighted method described by Schneeweiss et al.21 We defined CRC high-risk conditions and CRC screening tests, including flexible sigmoidoscopy and stool tests, as described in previous studies (Supplemental materials).20

The main outcome was total mortality. The date of death was extracted from the VHA Death Ascertainment File, which contains mortality data from the Master Person Index file in CDW and the Social Security Administration Death Master File. We used the date of death from any cause, as cause of death was not available.

A propensity score (PS) was created to match rural (including highly rural) and urban residents at a ratio of 1:1. Using a standard procedure described in prior publications, multivariable logistic regression used all baseline characteristics to estimate the PS and perform nearest-number matching without replacement.22,23 A caliper of 0.01 maximized the matched cohort size and achieved balance (Supplemental materials). We then examined the balance of baseline characteristics between PS-matched groups.

Analyses

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis estimated the hazard ratio (HR) of death in rural residents compared to urban residents in the PS-matched cohort. The outcome event was the date of death during the study’s follow-up period (defined as period from first CRC diagnosis to death or study end), with censoring at the study’s end date (September 30, 2021). The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by inspecting the Kaplan-Meier curves. Multiple analyses examined the HR of total mortality in the PS-matched cohort, stratified by sex, race, and ethnicity. We also examined the HR of total mortality stratified by duration of follow-up.

Another PS-matching analysis among veterans aged ≤ 45 years was performed using the same techniques described earlier in this article. We performed a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to compare mortality in PS-matched urban and rural veterans aged ≤ 45 years. The HR of death in all veterans aged ≤ 45 years (before PS-matching) was estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, adjusting for PS.

Dichotomous variables were compared using X2 tests and continuous variables were compared using t tests. Baseline characteristics with missing values were converted into categorical variables and the proportion of subjects with missing values was equalized between treatment groups after PS-matching. For subgroup analysis, we examined the HR of total mortality in each subgroup using separate Cox proportional hazards regression models similar to the primary analysis but adjusted for PS. Due to multiple comparisons in the subgroup analysis, the findings should be considered exploratory. Statistical tests were 2-tailed, and significance was defined as P < .05. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted from June 2022 to January 2023 using STATA, Version 17. The VA Orlando Healthcare System Institutional Review Board approved the study and waived requirements for informed consent because only deidentified data were used.

Results

After excluding 49 patients (Supplemental materials, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0560), we identified 30,219 veterans with newly diagnosed CRC between FY 2016 to 2021 (Table 1). Of these, 19,422 (64.3%) resided in urban areas and 10,797 (35.7%) resided in rural areas (Table 2). The mean (SD) duration from the first CRC diagnosis to death or study end was 832 (640) days, and the median (IQR) was 723 (246–1330) days. Overall, incident CRC diagnoses were numerically highest in FY 2016 and lowest in FY 2020 (Figure 1). Patients with CRC in rural areas vs urban areas were significantly older (mean, 71.2 years vs 70.8 years, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be male (96.7% vs 95.7%, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be White (83.6% vs 67.8%, respectively; P < .001) and more likely to be non-Hispanic (92.2% vs 87.5%, respectively; P < .001). In terms of general health, rural veterans with CRC were more likely to be overweight or obese (81.5% rural vs 78.5% urban; P < .001) but had fewer mean comorbidities as measured by CCI (5.66 rural vs 5.90 urban; P < .001). A higher proportion of rural veterans with CRC had received stool-based (fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test) CRC screening tests (61.6% rural vs 57.2% urban; P < .001). Fewer rural patients presented with systemic symptoms or signs within 1 year of CRC diagnosis (54.4% rural vs 57.5% urban, P < .001). Among urban patients with CRC, 6959 (35.8%) deaths were observed, compared with 3766 (34.9%) among rural patients (P = .10).

There were 21,568 PS-matched veterans: 10,784 in each group. In the PS-matched cohort, baseline characteristics were similar between veterans in urban and rural communities, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and comorbidities. Among rural patients with CRC, 3763 deaths (34.9%) were observed compared with 3702 (34.3%) among urban veterans. There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban CRC residents (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06; P = .53) (Figure 2).

Among veterans aged ≤ 45 years, 551 were diagnosed with CRC (391 urban and 160 rural). We PS-matched 142 pairs of urban and rural veterans without residual differences in baseline characteristics (eAppendix 1). There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.57-1.63; P = .90) (Figure 2). Similarly, no difference in mortality was observed adjusting for PS between all rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.67-1.59; P = .88).

There was no difference in total mortality between rural and urban veterans in any subgroup except for American Indian or Alaska Native veterans (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006) (eAppendix 2).

Discussion

This study examined characteristics of patients with CRC between urban and rural areas among veterans who were VHA patients. Similar to other studies, rural veterans with CRC were older, more likely to be White, and were obese, but exhibited fewer comorbidities (lower CCI and lower incidence of congestive heart failure, dementia, hemiplegia, kidney diseases, liver diseases and AIDS, but higher incidence of chronic obstructive lung disease).8,16 The incidence of CRC in this study population was lowest in FY 2020, which was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is attributed to COVID-19 pandemic disruption of health services.24 The overall mortality in this study was similar to rates reported in other studies from the VA Central Cancer Registry.4 In the PS-matched cohort, where baseline characteristics were similar between urban and rural patients with CRC, we found no disparities in CRC-specific mortality between veterans in rural and urban areas. Additionally, when analysis was restricted to veterans aged ≤ 45 years, the results remained consistent.

Subgroup analyses showed no significant difference in mortality between rural and urban areas by sex, race or ethnicity, except rural American Indian or Alaska Native veterans who had double the mortality of their urban counterparts (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006). This finding is difficult to interpret due to the small number of events and the wide CI. While with a Bonferroni correction the adjusted P value was .08, which is not statistically significant, a previous study found that although CRC incidence was lower overall in American Indian or Alaska Native populations compared to non-Hispanic White populations, CRC incidence was higher among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals in some areas such as Alaska and the Northern Plains.25,26 Studies have noted that rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations experience greater poverty, less access to broadband internet, and limited access to care, contributing to poorer cancer outcomes and lower survival.27 Thus, the finding of disparity in mortality between rural and urban American Indian or Alaska Native veterans warrants further study.

Other studies have raised concerns that CRC disproportionately affects adults in rural areas with higher mortality rates.14-16 These disparities arise from sociodemographic factors and modifiable risk factors, including physical activity, dietary patterns, access to cancer screening, and gaps in quality treatment resources.16,28 These factors operate at multiple levels: from individual, local health system, to community and policy.2,27 For example, a South Carolina study (1996–2016) found that residents in rural areas were more likely to be diagnosed with advanced CRC, possibly indicating lower rates of CRC screening in rural areas. They also had higher likelihood of death from CRC.15 However, the study did not include any clinical parameters, such as comorbidities or obesity. A statewide, population-based study in Utah showed that rural men experienced a lower CRC survival in their unadjusted analysis.16 However, the study was small, with only 3948 urban and 712 rural residents. Additionally, there was no difference in total mortality in the whole cohort (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07) or in CRC-specific death (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.08). A nationwide study also showed that CRC mortality rates were 8% higher in nonmetropolitan or rural areas than in the most urbanized areas containing large metropolitan counties.29 However, this study did not include descriptions of clinical confounders, such as comorbidities, making it difficult to ascertain whether the difference in CRC mortality was due to rurality or differences in baseline risk characteristics.

In this study, the lack of CRC-specific mortality disparities may be attributed to the structures and practices of VHA health care. Recent studies have noted that mortality of several chronic medical conditions treated at the VHA was lower than at non-VHA hospitals.30,31 One study that measured the quality of nonmetastatic CRC care based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines showed that > 72% of VHA patients received guideline-concordant care for each diagnostic and therapeutic measure, except for follow-up colonoscopy timing, which appear to be similar or superior to that of the private sector.30,32,33 Some of the VA initiative for CRC screening may bypass the urban-rurality divide such as the mailed fecal immunochemical test program for CRC. This program was implemented at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to avoid disruptions of medical care.34 Rural patients are more likely to undergo fecal immunochemical testing when compared to urban patients in this data. Beyond clinical care, the VHA uses processes to tackle social determinants of health such as housing, food security, and transportation, promoting equal access to health care, and promoting cultural competency among HCPs.35-37

The results suggest that solutions to CRC disparities between rural and urban areas need to consider known barriers to rural health care, including transportation, diminished rural health care workforce, and other social determinants of health.9,10,27,38 VHA makes considerable efforts to provide equitable care to all enrolled veterans, including specific programs for rural veterans, including ongoing outreach.39 This study demonstrated lack of disparity in CRC-specific mortality in veterans receiving VHA care, highlighting the importance of these efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

This study used the VHA cohort to compare patient characteristics and mortality between patients with CRC residing in rural and urban areas. The study provides nationwide perspectives on CRC across the geographical spectrum and used a longitudinal cohort with prolonged follow-up to account for comorbidities.

However, the study compared a cohort of rural and urban veterans enrolled in the VHA; hence, the results may not reflect CRC outcomes in veterans without access to VHA care. Rurality has been independently associated with decreased likelihood of meeting CRC screening guidelines among veterans and military service members.38 This study lacked sufficient information to compare CRC staging or treatment modalities among veterans. Although the data cannot identify CRC stage, the proportions of patients with metastatic CRC at diagnosis and CRC location were similar between groups. The study did not have information on their care outside of VHA setting.

This study could not ascertain whether disparities existed in CRC treatment modality since rural residence may result in referral to community-based CRC care, which did not appear in the data. To address these limitations, we used death from any cause as the primary outcome, since death is a hard outcome and is not subject to ascertainment bias. The relatively short follow-up time is another limitation, though subgroup analysis by follow-up did not show significant differences. Despite PS matching, residual unmeasured confounding may exist between urban and rural groups. The predominantly White, male VHA population with high CCI may limit the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

Rural VHA enrollees had similar survival rates after CRC diagnosis compared to their urban counterparts in a PS-matched analysis. The VHA models of care—including mailed CRC screening tools, several socioeconomic determinants of health (housing, food security, and transportation), and promoting equal access to health care, as well as cultural competency among HCPs—HCPs—may help alleviate disparities across the rural-urban spectrum. The VHA should continue efforts to enroll veterans and provide comprehensive coordinated care in community partnerships.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States, with an estimated 52,550 deaths in 2023.1 However, the disease burden varies among different segments of the population.2 While both CRC incidence and mortality have been decreasing due to screening and advances in treatment, there are disparities in incidence and mortality across the sociodemographic spectrum including race, ethnicity, education, and income.1-4 While CRC incidence is decreasing for older adults, it is increasing among those aged < 55 years.5 The incidence of CRC in adults aged 40 to 54 years has increased by 0.5% to 1.3% annually since the mid-1990s.6 The US Preventive Services Task Force now recommends starting CRC screening at age 45 years for asymptomatic adults with average risk.7

Disparities also exist across geographical boundaries and living environment. Rural Americans faces additional challenges in health and lifestyle that can affect CRC outcomes. Compared to their urban counterparts, rural residents are more likely to be older, have lower levels of education, higher levels of poverty, lack health insurance, and less access to health care practitioners (HCPs).8-10 Geographic proximity, defined as travel time or physical distance to a health facility, has been recognized as a predictor of inferior outcomes.11 These aspects of rural living may pose challenges for accessing care for CRC screening and treatment.11-13 National and local studies have shown disparities in CRC screening rates, incidence, and mortality between rural and urban populations.14-16

It is unclear whether rural/urban disparities persist under the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) health care delivery model. This study examined differences in baseline characteristics and mortality between rural and urban veterans newly diagnosed with CRC. We also focused on a subpopulation aged ≤ 45 years.

Methods

This study extracted national data from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) hosted in the VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) environment. VINCI is an initiative to improve access to VA data and facilitate the analysis of these data while ensuring veterans’ privacy and data security.17 CDW is the VHA business intelligence information repository, which extracts data from clinical and nonclinical sources following prescribed and validated protocols. Data extracted included demographics, diagnosis, and procedure codes for both inpatient and outpatient encounters, vital signs, and vital status. This study used data previously extracted from a national cohort of veterans that encompassed all patients who received a group of commonly prescribed medications, such as statins, proton pump inhibitors, histamine-2 blockers, acetaminophen-containing products, and hydrocortisone-containing skin applications. This cohort encompassed 8,648,754 veterans, from whom 2,460,727 had encounters during fiscal years (FY) 2016 to 2021 (study period). The cohort was used to ensure that subjects were VHA patients, allowing them to adequately capture their clinical profiles.

Patients were identified as rural or urban based on their residence address at the date of their first diagnosis of CRC. The Geospatial Service Support Center (GSSC) aggregates and updates veterans’ residence address records for all enrolled veterans from the National Change of Address database. The data contain 1 record per enrollee. GSSC Geocoded Enrollee File contains enrollee addresses and their rurality indicators, categorized as urban, rural, or highly rural.18 Rurality is defined by the Rural Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) categories developed by the Department of Agriculture and the Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services.19 Urban areas had RUCA codes of 1.0 to 1.1, and highly rural areas had RUCA scores of 10.0. All other areas were classified as rural. Since the proportion of veterans from highly rural areas was small, we included residents from highly rural areas in the rural residents’ group.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All veterans newly diagnosed with CRC from FY 2016 to 2021 were included. We used the ninth and tenth clinical modification revisions of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM) to define CRC diagnosis (Supplemental materials).4,20 To ensure that patients were newly diagnosed with CRC, this study excluded patients with a previous ICD-9-CM code for CRC diagnosis since FY 2003.

Comorbidities were identified using diagnosis and procedure codes from inpatient and outpatient encounters, which were used to calculate the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) at the time of CRC diagnosis using the weighted method described by Schneeweiss et al.21 We defined CRC high-risk conditions and CRC screening tests, including flexible sigmoidoscopy and stool tests, as described in previous studies (Supplemental materials).20

The main outcome was total mortality. The date of death was extracted from the VHA Death Ascertainment File, which contains mortality data from the Master Person Index file in CDW and the Social Security Administration Death Master File. We used the date of death from any cause, as cause of death was not available.

A propensity score (PS) was created to match rural (including highly rural) and urban residents at a ratio of 1:1. Using a standard procedure described in prior publications, multivariable logistic regression used all baseline characteristics to estimate the PS and perform nearest-number matching without replacement.22,23 A caliper of 0.01 maximized the matched cohort size and achieved balance (Supplemental materials). We then examined the balance of baseline characteristics between PS-matched groups.

Analyses

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis estimated the hazard ratio (HR) of death in rural residents compared to urban residents in the PS-matched cohort. The outcome event was the date of death during the study’s follow-up period (defined as period from first CRC diagnosis to death or study end), with censoring at the study’s end date (September 30, 2021). The proportional hazards assumption was assessed by inspecting the Kaplan-Meier curves. Multiple analyses examined the HR of total mortality in the PS-matched cohort, stratified by sex, race, and ethnicity. We also examined the HR of total mortality stratified by duration of follow-up.

Another PS-matching analysis among veterans aged ≤ 45 years was performed using the same techniques described earlier in this article. We performed a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to compare mortality in PS-matched urban and rural veterans aged ≤ 45 years. The HR of death in all veterans aged ≤ 45 years (before PS-matching) was estimated using Cox proportional hazard regression analysis, adjusting for PS.

Dichotomous variables were compared using X2 tests and continuous variables were compared using t tests. Baseline characteristics with missing values were converted into categorical variables and the proportion of subjects with missing values was equalized between treatment groups after PS-matching. For subgroup analysis, we examined the HR of total mortality in each subgroup using separate Cox proportional hazards regression models similar to the primary analysis but adjusted for PS. Due to multiple comparisons in the subgroup analysis, the findings should be considered exploratory. Statistical tests were 2-tailed, and significance was defined as P < .05. Data management and statistical analyses were conducted from June 2022 to January 2023 using STATA, Version 17. The VA Orlando Healthcare System Institutional Review Board approved the study and waived requirements for informed consent because only deidentified data were used.

Results

After excluding 49 patients (Supplemental materials, available at doi:10.12788/fp.0560), we identified 30,219 veterans with newly diagnosed CRC between FY 2016 to 2021 (Table 1). Of these, 19,422 (64.3%) resided in urban areas and 10,797 (35.7%) resided in rural areas (Table 2). The mean (SD) duration from the first CRC diagnosis to death or study end was 832 (640) days, and the median (IQR) was 723 (246–1330) days. Overall, incident CRC diagnoses were numerically highest in FY 2016 and lowest in FY 2020 (Figure 1). Patients with CRC in rural areas vs urban areas were significantly older (mean, 71.2 years vs 70.8 years, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be male (96.7% vs 95.7%, respectively; P < .001), more likely to be White (83.6% vs 67.8%, respectively; P < .001) and more likely to be non-Hispanic (92.2% vs 87.5%, respectively; P < .001). In terms of general health, rural veterans with CRC were more likely to be overweight or obese (81.5% rural vs 78.5% urban; P < .001) but had fewer mean comorbidities as measured by CCI (5.66 rural vs 5.90 urban; P < .001). A higher proportion of rural veterans with CRC had received stool-based (fecal occult blood test or fecal immunochemical test) CRC screening tests (61.6% rural vs 57.2% urban; P < .001). Fewer rural patients presented with systemic symptoms or signs within 1 year of CRC diagnosis (54.4% rural vs 57.5% urban, P < .001). Among urban patients with CRC, 6959 (35.8%) deaths were observed, compared with 3766 (34.9%) among rural patients (P = .10).

There were 21,568 PS-matched veterans: 10,784 in each group. In the PS-matched cohort, baseline characteristics were similar between veterans in urban and rural communities, including age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, and comorbidities. Among rural patients with CRC, 3763 deaths (34.9%) were observed compared with 3702 (34.3%) among urban veterans. There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban CRC residents (HR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.97-1.06; P = .53) (Figure 2).

Among veterans aged ≤ 45 years, 551 were diagnosed with CRC (391 urban and 160 rural). We PS-matched 142 pairs of urban and rural veterans without residual differences in baseline characteristics (eAppendix 1). There was no significant difference in the HR of mortality between rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 0.97; 95% CI, 0.57-1.63; P = .90) (Figure 2). Similarly, no difference in mortality was observed adjusting for PS between all rural and urban veterans aged ≤ 45 years (HR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.67-1.59; P = .88).

There was no difference in total mortality between rural and urban veterans in any subgroup except for American Indian or Alaska Native veterans (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006) (eAppendix 2).

Discussion

This study examined characteristics of patients with CRC between urban and rural areas among veterans who were VHA patients. Similar to other studies, rural veterans with CRC were older, more likely to be White, and were obese, but exhibited fewer comorbidities (lower CCI and lower incidence of congestive heart failure, dementia, hemiplegia, kidney diseases, liver diseases and AIDS, but higher incidence of chronic obstructive lung disease).8,16 The incidence of CRC in this study population was lowest in FY 2020, which was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is attributed to COVID-19 pandemic disruption of health services.24 The overall mortality in this study was similar to rates reported in other studies from the VA Central Cancer Registry.4 In the PS-matched cohort, where baseline characteristics were similar between urban and rural patients with CRC, we found no disparities in CRC-specific mortality between veterans in rural and urban areas. Additionally, when analysis was restricted to veterans aged ≤ 45 years, the results remained consistent.

Subgroup analyses showed no significant difference in mortality between rural and urban areas by sex, race or ethnicity, except rural American Indian or Alaska Native veterans who had double the mortality of their urban counterparts (HR, 2.41; 95% CI, 1.29-4.50; P = .006). This finding is difficult to interpret due to the small number of events and the wide CI. While with a Bonferroni correction the adjusted P value was .08, which is not statistically significant, a previous study found that although CRC incidence was lower overall in American Indian or Alaska Native populations compared to non-Hispanic White populations, CRC incidence was higher among American Indian or Alaska Native individuals in some areas such as Alaska and the Northern Plains.25,26 Studies have noted that rural American Indian/Alaska Native populations experience greater poverty, less access to broadband internet, and limited access to care, contributing to poorer cancer outcomes and lower survival.27 Thus, the finding of disparity in mortality between rural and urban American Indian or Alaska Native veterans warrants further study.

Other studies have raised concerns that CRC disproportionately affects adults in rural areas with higher mortality rates.14-16 These disparities arise from sociodemographic factors and modifiable risk factors, including physical activity, dietary patterns, access to cancer screening, and gaps in quality treatment resources.16,28 These factors operate at multiple levels: from individual, local health system, to community and policy.2,27 For example, a South Carolina study (1996–2016) found that residents in rural areas were more likely to be diagnosed with advanced CRC, possibly indicating lower rates of CRC screening in rural areas. They also had higher likelihood of death from CRC.15 However, the study did not include any clinical parameters, such as comorbidities or obesity. A statewide, population-based study in Utah showed that rural men experienced a lower CRC survival in their unadjusted analysis.16 However, the study was small, with only 3948 urban and 712 rural residents. Additionally, there was no difference in total mortality in the whole cohort (HR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.86-1.07) or in CRC-specific death (HR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.81-1.08). A nationwide study also showed that CRC mortality rates were 8% higher in nonmetropolitan or rural areas than in the most urbanized areas containing large metropolitan counties.29 However, this study did not include descriptions of clinical confounders, such as comorbidities, making it difficult to ascertain whether the difference in CRC mortality was due to rurality or differences in baseline risk characteristics.

In this study, the lack of CRC-specific mortality disparities may be attributed to the structures and practices of VHA health care. Recent studies have noted that mortality of several chronic medical conditions treated at the VHA was lower than at non-VHA hospitals.30,31 One study that measured the quality of nonmetastatic CRC care based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines showed that > 72% of VHA patients received guideline-concordant care for each diagnostic and therapeutic measure, except for follow-up colonoscopy timing, which appear to be similar or superior to that of the private sector.30,32,33 Some of the VA initiative for CRC screening may bypass the urban-rurality divide such as the mailed fecal immunochemical test program for CRC. This program was implemented at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to avoid disruptions of medical care.34 Rural patients are more likely to undergo fecal immunochemical testing when compared to urban patients in this data. Beyond clinical care, the VHA uses processes to tackle social determinants of health such as housing, food security, and transportation, promoting equal access to health care, and promoting cultural competency among HCPs.35-37

The results suggest that solutions to CRC disparities between rural and urban areas need to consider known barriers to rural health care, including transportation, diminished rural health care workforce, and other social determinants of health.9,10,27,38 VHA makes considerable efforts to provide equitable care to all enrolled veterans, including specific programs for rural veterans, including ongoing outreach.39 This study demonstrated lack of disparity in CRC-specific mortality in veterans receiving VHA care, highlighting the importance of these efforts.

Strengths and Limitations

This study used the VHA cohort to compare patient characteristics and mortality between patients with CRC residing in rural and urban areas. The study provides nationwide perspectives on CRC across the geographical spectrum and used a longitudinal cohort with prolonged follow-up to account for comorbidities.

However, the study compared a cohort of rural and urban veterans enrolled in the VHA; hence, the results may not reflect CRC outcomes in veterans without access to VHA care. Rurality has been independently associated with decreased likelihood of meeting CRC screening guidelines among veterans and military service members.38 This study lacked sufficient information to compare CRC staging or treatment modalities among veterans. Although the data cannot identify CRC stage, the proportions of patients with metastatic CRC at diagnosis and CRC location were similar between groups. The study did not have information on their care outside of VHA setting.

This study could not ascertain whether disparities existed in CRC treatment modality since rural residence may result in referral to community-based CRC care, which did not appear in the data. To address these limitations, we used death from any cause as the primary outcome, since death is a hard outcome and is not subject to ascertainment bias. The relatively short follow-up time is another limitation, though subgroup analysis by follow-up did not show significant differences. Despite PS matching, residual unmeasured confounding may exist between urban and rural groups. The predominantly White, male VHA population with high CCI may limit the generalizability of the results.

Conclusions

Rural VHA enrollees had similar survival rates after CRC diagnosis compared to their urban counterparts in a PS-matched analysis. The VHA models of care—including mailed CRC screening tools, several socioeconomic determinants of health (housing, food security, and transportation), and promoting equal access to health care, as well as cultural competency among HCPs—HCPs—may help alleviate disparities across the rural-urban spectrum. The VHA should continue efforts to enroll veterans and provide comprehensive coordinated care in community partnerships.

- Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254. doi:10.3322/caac.21772

- Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer and intervention framework and strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):354-367. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.029

- Murphy G, Devesa SS, Cross AJ, Inskip PD, McGlynn KA, Cook MB. Sex disparities in colorectal cancer incidence by anatomic subsite, race and age. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(7):1668-75. doi:10.1002/ijc.25481

- Zullig LL, Smith VA, Jackson GL, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics from the Veterans Affairs central cancer registry. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15(4):e199-e204. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2016.04.005

- Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 2021. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews:Chapter 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570917/

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8). doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

- Hines R, Markossian T, Johnson A, Dong F, Bayakly R. Geographic residency status and census tract socioeconomic status as determinants of colorectal cancer outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e63-e71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301572

- Cauwels J. The many barriers to high-quality rural health care. 2022;(9):1-32. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/CAT.22.0254

- Gong G, Phillips SG, Hudson C, Curti D, Philips BU. Higher US rural mortality rates linked to socioeconomic status, physician shortages, and lack of health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood);38(12):2003-2010. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00722

- Aboagye JK, Kaiser HE, Hayanga AJ. Rural-urban differences in access to specialist providers of colorectal cancer care in the United States: a physician workforce issue. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):537-543. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5062

- Lyckholm LJ, Hackney MH, Smith TJ. Ethics of rural health care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40(2):131-138. doi:10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00139-1

- Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341-378. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341

- Singh GK, Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:2819372. doi:10.1155/2017/2819372

- Adams SA, Zahnd WE, Ranganathan R, et al. Rural and racial disparities in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in South Carolina, 1996 - 2016. J Rural Health. 2022;38(1):34-39. doi:10.1111/jrh.12580

- Rogers CR, Blackburn BE, Huntington M, et al. Rural- urban disparities in colorectal cancer survival and risk among men in Utah: a statewide population-based study. Cancer Causes Control. 2020;31(3):241-253. doi:10.1007/s10552-020-01268-2

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), VA HSR RES 13-457. https://vincicentral.vinci.med.va.gov [Source not verified]

- US Department of Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center. VIReC Research User Guide: PSSG Geocoded Enrollee Files, 2015 Edition. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Information Resource Center; May. 2016. [source not verified]

- Goldsmith HF, Puskin DS, Stiles DJ. Improving the operational definition of “rural areas” for federal programs. US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/pdf/improving-the-operational-definition-of-rural-areas.pdf

- Adams MA, Kerr EA, Dominitz JA, et al. Development and validation of a new ICD-10-based screening colonoscopy overuse measure in a large integrated healthcare system: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;32(7):414-424. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014236

- Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in Medicare populations. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(4):1103-1120. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00165

- Becker S, Ichino A. Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. The Stata Journal. 2002;2(4):358-377.

- Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Statistical software components. Revised February 1, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2024. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Cao J, Zhang S. Multiple Comparison Procedures. JAMA. 2014;312(5):543-544. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.9440

- Gopalani SV, Janitz AE, Martinez SA, et al. Trends in cancer incidence among American Indians and Alaska Natives and Non-Hispanic Whites in the United States, 1999-2015. Epidemiology. 2020;31(2):205-213. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000001140

- Zahnd WE, Murphy C, Knoll M, et al. The intersection of rural residence and minority race/ethnicity in cancer disparities in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(4). doi:10.3390/ijerph18041384

- Blake KD, Moss JL, Gaysynsky A, Srinivasan S, Croyle RT. Making the case for investment in rural cancer control: an analysis of rural cancer incidence, mortality, and funding trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(7):992-997. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0092

- Singh GK, Williams SD, Siahpush M, Mulhollen A. Socioeconomic, rural-urban, and racial inequalities in US cancer mortality: part i-all cancers and lung cancer and part iicolorectal, prostate, breast, and cervical cancers. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2011;2011:107497. doi:10.1155/2011/107497

- Jackson GL, Melton LD, Abbott DH, et al. Quality of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer care in the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(19):3176-3181. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7948

- Yoon J, Phibbs CS, Ong MK, et al. Outcomes of veterans treated in Veterans Affairs hospitals vs non-Veterans Affairs hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(12):e2345898. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.45898

- Malin JL, Schneider EC, Epstein AM, Adams J, Emanuel EJ, Kahn KL. Results of the National Initiative for Cancer Care Quality: how can we improve the quality of cancer care in the United States? J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(4):626-634. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.3365

- Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(5):1570-1595. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2008.02.002

- Deeds SA, Moore CB, Gunnink EJ, et al. Implementation of a mailed faecal immunochemical test programme for colorectal cancer screening among Veterans. BMJ Open Qual. 2022;11(4). doi:10.1136/bmjoq-2022-001927

- Yehia BR, Greenstone CL, Hosenfeld CB, Matthews KL, Zephyrin LC. The role of VA community care in addressing health and health care disparities. Med Care. 2017;55(Suppl 9 suppl 2):S4-S5. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000768

- Wright BN, MacDermid Wadsworth S, Wellnitz A, Eicher- Miller HA. Reaching rural veterans: a new mechanism to connect rural, low-income US Veterans with resources and improve food security. J Public Health (Oxf). 2019;41(4):714-723. doi:10.1093/pubmed/fdy203

- Nelson RE, Byrne TH, Suo Y, et al. Association of temporary financial assistance with housing stability among US veterans in the supportive services for veteran families program. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037047. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37047

- McDaniel JT, Albright D, Lee HY, et al. Rural–urban disparities in colorectal cancer screening among military service members and Veterans. J Mil Veteran Fam Health. 2019;5(1):40-48. doi:10.3138/jmvfh.2018-0013

- US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Rural Health. The rural veteran outreach toolkit. Updated February 12, 2025. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ruralhealth.va.gov/partners/toolkit.asp

- Siegel RL, Wagle NS, Cercek A, Smith RA, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(3):233-254. doi:10.3322/caac.21772

- Carethers JM, Doubeni CA. Causes of socioeconomic disparities in colorectal cancer and intervention framework and strategies. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(2):354-367. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.029

- Murphy G, Devesa SS, Cross AJ, Inskip PD, McGlynn KA, Cook MB. Sex disparities in colorectal cancer incidence by anatomic subsite, race and age. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(7):1668-75. doi:10.1002/ijc.25481

- Zullig LL, Smith VA, Jackson GL, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics from the Veterans Affairs central cancer registry. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2016;15(4):e199-e204. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2016.04.005

- Lin JS, Perdue LA, Henrikson NB, Bean SI, Blasi PR. Screening for Colorectal Cancer: An Evidence Update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. 2021. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Evidence Syntheses, formerly Systematic Evidence Reviews:Chapter 1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2021. Accessed February 18, 2025. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK570917/

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8). doi:10.1093/jnci/djw322

- Davidson KW, Barry MJ, Mangione CM, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2021;325(19):1965-1977. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.6238

- Hines R, Markossian T, Johnson A, Dong F, Bayakly R. Geographic residency status and census tract socioeconomic status as determinants of colorectal cancer outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e63-e71. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301572

- Cauwels J. The many barriers to high-quality rural health care. 2022;(9):1-32. NEJM Catal Innov Care Deliv. Accessed April 24, 2025. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/pdf/10.1056/CAT.22.0254

- Gong G, Phillips SG, Hudson C, Curti D, Philips BU. Higher US rural mortality rates linked to socioeconomic status, physician shortages, and lack of health insurance. Health Aff (Millwood);38(12):2003-2010. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00722

- Aboagye JK, Kaiser HE, Hayanga AJ. Rural-urban differences in access to specialist providers of colorectal cancer care in the United States: a physician workforce issue. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(6):537-543. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2013.5062

- Lyckholm LJ, Hackney MH, Smith TJ. Ethics of rural health care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2001;40(2):131-138. doi:10.1016/s1040-8428(01)00139-1

- Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:341-378. doi:10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.341

- Singh GK, Jemal A. Socioeconomic and racial/ethnic disparities in cancer mortality, incidence, and survival in the United States, 1950-2014: over six decades of changing patterns and widening inequalities. J Environ Public Health. 2017;2017:2819372. doi:10.1155/2017/2819372

- Adams SA, Zahnd WE, Ranganathan R, et al. Rural and racial disparities in colorectal cancer incidence and mortality in South Carolina, 1996 - 2016. J Rural Health. 2022;38(1):34-39. doi:10.1111/jrh.12580

- Rogers CR, Blackburn BE, Huntington M, et al. Rural- urban disparities in colorectal cancer survival and risk among men in Utah: a statewide population-based study. Cancer Causes Control. 2020;31(3):241-253. doi:10.1007/s10552-020-01268-2

- US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI), VA HSR RES 13-457. https://vincicentral.vinci.med.va.gov [Source not verified]

- US Department of Veterans Affairs Information Resource Center. VIReC Research User Guide: PSSG Geocoded Enrollee Files, 2015 Edition. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Information Resource Center; May. 2016. [source not verified]

- Goldsmith HF, Puskin DS, Stiles DJ. Improving the operational definition of “rural areas” for federal programs. US Department of Health and Human Services; 1993. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/pdf/improving-the-operational-definition-of-rural-areas.pdf

- Adams MA, Kerr EA, Dominitz JA, et al. Development and validation of a new ICD-10-based screening colonoscopy overuse measure in a large integrated healthcare system: a retrospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;32(7):414-424. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014236

- Schneeweiss S, Wang PS, Avorn J, Glynn RJ. Improved comorbidity adjustment for predicting mortality in Medicare populations. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(4):1103-1120. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.00165

- Becker S, Ichino A. Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores. The Stata Journal. 2002;2(4):358-377.

- Leuven E, Sianesi B. PSMATCH2: Stata module to perform full Mahalanobis and propensity score matching, common support graphing, and covariate imbalance testing. Statistical software components. Revised February 1, 2018. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s432001.html.

- US Cancer Statistics Working Group. US cancer statistics data visualizations tool. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. June 2024. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dataviz

- Cao J, Zhang S. Multiple Comparison Procedures. JAMA. 2014;312(5):543-544. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.9440

- Gopalani SV, Janitz AE, Martinez SA, et al. Trends in cancer incidence among American Indians and Alaska Natives and Non-Hispanic Whites in the United States, 1999-2015. Epidemiology. 2020;31(2):205-213. doi:10.1097/EDE.0000000000001140