User login

MS & Pregnancy: What's Safe?

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

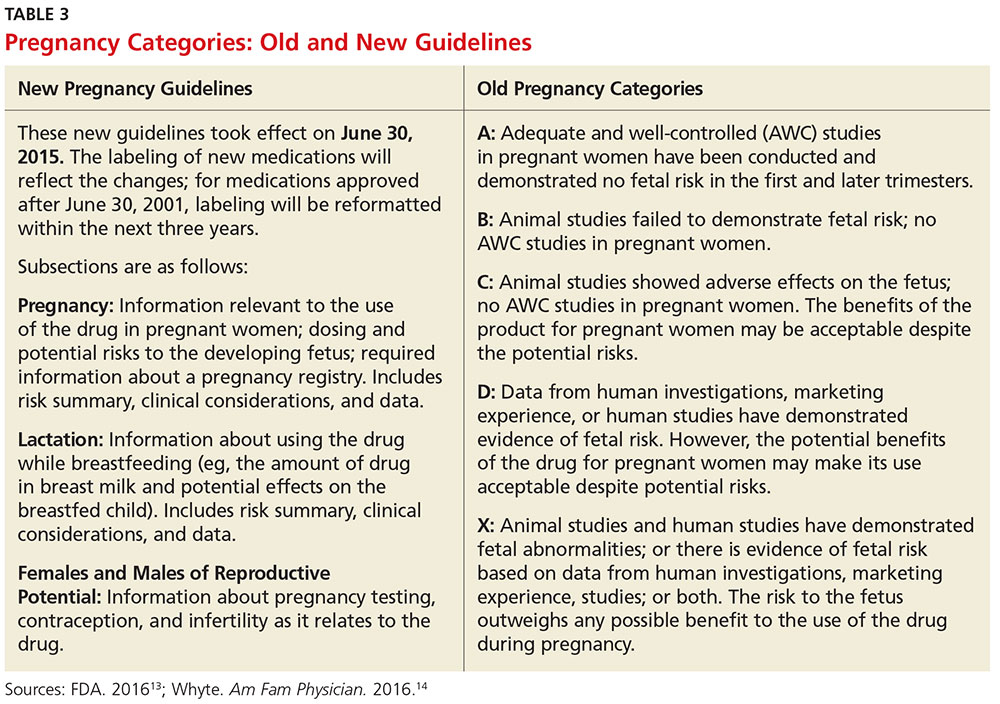

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.

14. Whyte J. FDA implements new labeling for medications used during pregnancy and lactation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(1):12-13.

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

Q)What are the considerations and recommendations for pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with multiple sclerosis? When should women discontinue their disease-modifying therapies?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an inflammatory, demyelinating, degenerative disease. Three times more common in women than men, it may affect pregnancy planning and childbearing experiences.6 Evidence demonstrates a reduction in annualized relapse rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period with exclusive breastfeeding. Therefore, pregnancy and exclusive breastfeeding provide a favorable immunomodulatory effect in women with MS, which combats the increased relapse risk associated with the postpartum period.7,8

Reproductive education—including conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding—is critical for patients with MS and their partners during a woman’s childbearing years. However, women with MS do not require special considerations during pregnancy unless they have remarkable disability. As soon as these women and their partners decide upon pregnancy, a plan should be established that includes a discussion about potential risks to the fetus due to drug exposure, as well as risks to the mother. The goal should be to minimize risk for disease activity and optimize the health of the baby.

Use of DMTs during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. All disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are usually discontinued during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Common practice among MS experts is to discontinue DMTs prior to conception, with a few exceptions. There is no consensus about timing of discontinuation and washout period for each DMT. The decision is based on the half-life of each DMT, the opinions of the woman and her partner, and risk tolerance. Note: For the purposes of this discussion, the old pregnancy category designations are used, since they are familiar to clinicians. New guidelines took effect in June 2015; Table 3 outlines the change in format.

Injectables. Glatiramer acetate (GA) is the safest drug in relation to pregnancy and breastfeeding (category B). There is no evidence of congenital malformation or spontaneous abortion. The common recommendation is to discontinue the drug one to two months before conception, although some clinicians allow continuation of the injections throughout pregnancy and into breastfeeding.

Interferon-ßs are category C and therefore pose minimal risk for the fetus. The washout period before conception is two to three months, varying among clinicians. Although there is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in humans, animal data show increased risk for abortion.9

Both GA and interferon-ßs are large molecules; there is a very minimal chance that the medication will transmit to the baby via breast milk. Thus, both DMTs are considered safe during lactation.7

Oral MS medications. The three approved MS oral medications are fingolimod, dimethyl fumarate (DMF), and teriflunomide. Fingolimod and DMF are both category C. Women on DMF must discontinue use of the medication one month prior to conception due to its short half-life. There are no reports of birth defects or spontaneous abortion in women taking DMF. Fingolimod needs to be discontinued two months prior to conception. Animal data show evidence for teratogenicity and embryolethality at lower doses of fingolimod than those used in humans.7

Teriflunomide is category X, posing high risk for the health of the fetus. It stays in the blood for approximately eight months after discontinuation of use. Animal data show teratogenicity and embryotoxicity; therefore, teriflunomide is contraindicated in pregnancy. Women on teriflunomide who plan to become pregnant need to undergo an elimination procedure with cholestyramine or charcoal.

Infusions and injections (monoclonal antibodies). The approved monoclonal antibodies include natalizumab, alemtuzumab, and daclizumab. (Currently, use of rituximab in MS is off label, and the FDA is reviewing the efficacy and safety data for ocrelizumab.) The monoclonal antibodies are category C. The recommendation is to discontinue natalizumab one to two months prior to conception and discontinue alemtuzumab four months preconception.10 There is no evidence of spontaneous abortion or birth defects in women on alemtuzumab, but there is potentially increased risk for spontaneous abortion in those on natalizumab.

The spontaneous abortion rate in daclizumab-exposed women is consistent with early pregnancy loss in the general population (12% to 26%). Data on a small number of pregnancies exposed to daclizumab did not suggest an increased risk for adverse fetal or maternal outcomes.11 However, the recommendation is to discontinue daclizumab four months prior to conception. Rituximab should be discontinued 12 months prior to conception, based on the manufacturer recommendation, although it is potentially safe to conceive when the B cell counts return to normal.

Chemotherapy agents. Mitoxantrone is the only FDA-approved chemotherapeutic drug used in MS. However, a few chemotherapy drugs—among them, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide—are used off label. Chemotherapeutic agents are category D, except methotrexate (category X). Women on category D medications must use a method of birth control for three months after stopping the DMT. Often, clinicians will recommend women initiate GA or interferon during this period, in the hope of minimizing disease activity. Women on mitoxantrone and methotrexate need to use birth control for six months after stopping these immunosuppressive medications, before conceiving.12 These women likely need to switch to a safer pregnancy DMT during the long washout period.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding among women with MS require planning and decision making. The recommendations differ among clinicians and MS experts since there is no definitive evidence about the risks of the DMTs on the mother and/or the fetus. Clinicians should discuss the potential risks with women based on their knowledge and experience, and the data available based on animal research and the pregnancy registries. —ABB-Z

Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP

President-Elect of IOMSN

Neurology Faculty, Icahn School of Medicine, Mount Sinai Hospital System, New York, New York

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.

14. Whyte J. FDA implements new labeling for medications used during pregnancy and lactation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(1):12-13.

6. Tullman MJ. Overview of the epidemiology, diagnosis, and disease progression associated with multiple sclerosis. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(2):S15-S20.

7. Fabian M. Pregnancy in the setting of multiple sclerosis. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2016; 22(3):837-850.

8. Vukusic S, Hutchinson M, Hours M, et al. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis (the PRIMS study): clinical predictors of post-partum relapse. Brain. 2004;127(6):1353-1360.

9. Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, Kornmann G. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011; 17(4):423-430.

10. Coyle PK. Multiple sclerosis in pregnancy. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2014;20(1):42-59.

11. Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Pregnancy and multiple sclerosis: from molecular mechanisms to clinical application. Semin Immunopathol. 2016;38:709.

12. Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11(5):280-289.

13. FDA. Pregnancy and lactation labeling (drugs) final rule. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/DevelopmentResources/Labeling/ucm093307.htm. Accessed November 2, 2016.

14. Whyte J. FDA implements new labeling for medications used during pregnancy and lactation. Am Fam Physician. 2016;94(1):12-13.

Quality of Life in Aging Multiple Sclerosis Patients

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the association between clinical and demographic factors and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among older people with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Design. Cross-sectional survey-based study.

Setting and participants. Patients with MS aged 60 years or older were recruited from 4 MS centers in Long Island, NY. Patients with severe cognitive impairment as determined by the health care practitioner were excluded. Participants were asked to complete 3 surveys at 3 different time-points. In the first survey, participants completed the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale and the Patient Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (P-MSNQ). The second survey was the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQOL-54), and the third survey included the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and a disability status self-assessment scale. Cognitive function was measured at the time of recruitment using the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT).

Analysis. The Andersen Healthcare Utilization model was used to structure the multivariate regression analysis. This model identifies multiple domains affecting quality of life, and the variables from the surveys were categorized according to domain: predisposing characteristics (demographic variables), enabling resources (caregiver support and living situation), needs (eg, health-related measures), and health behaviors (medication use, adherence).

Main results. A total of 211 completed the first survey, 188 the second, and 179 the third. 80% were female and 95% were white. Average age was 65.5 (SD 5.6) years. 56% of respondents’ self-reported scores on the SDMT classified them as cognitively impaired. Risk of neuropsychological impairment, depression, and disability status were significantly associated with a decreased mental and physical HRQOL. Significantly, there was a strong association between predisposing characteristics and QOL. Being widowed and remaining employed were the strongest predictors of better physical QOL and having an education level of high school or less was a predictor of lower mental HRQOL.

Conclusion. Clinicians should measure HRQOL in older MS patients regularly and assess for depression and cognitive impairment.

Commentary

Quality of life is an important marker of MS patients’ well-being as they cope with this chronic illness [1]. The progression of the disease and its symptomatology often negatively affect HRQOL. However, multiple psychosocial factors, such as coping, mood, self-efficacy, and perceived support, affect QOL of patients with MS more than biological variables such as weakness or burden of radiologic disease [2]. For example, many self-report HRQOL indices are strongly predicted by measures of depression [3]. In addition, many studies have found a positive association between physical disability and reduced QOL [4,5]. Further, while perceived HRQOL may be a meaningful outcome in itself, it may also be a predictor for outcomes such as disability-related changes [6].

MS leads to disability and loss of function in all age-groups, but only a few studies have focused on HRQOL among elderly patients with MS. As patients with MS age, they may develop comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes that may affect HRQOL. However, in a previous study comparing QOL between older and younger patients with MS, elderly and younger patients with MS had similar QOL even though the elderly patients had more physical limitations [7].

The strength of the current study was using the Andersen Healthcare Utilization regression model in the analysis, since it factors in multiple influences on health status. The striking evidence that employment and being widowed were linked to better physical QOL suggest that older MS patients may have better adaptation and adjustment to their illness. Researchers have shown that the widowed elderly often take on more responsibilities and tasks when they lose their partner, which leads to increased self-esteem and QOL [8]. Another advantage of the study was the fact that the investigators evaluated the different exposure variables and their associations with mental and physical QOL while identifying multiple confounding variables. Additionally, the use of 2 cognitive assessment tools provided a stronger assessment of patients’ cognitive function.

The main weakness of the study was using a cross-sectional study design with convenience sampling. The convenience sample was based on voluntary participation, which may result in self-selection bias. In addition, the self-report design is subject to the usual limitations of self-reporting for data collection: participants may exaggerate symptoms in order to make their situation seem worse or may under-report the severity or frequency of symptoms in order to minimize their problems. While the overall sample size was 211, not all respondents completed all the surveys, and response rates varied by questions. Thus, missing data may have affected results, but which data are missing is not discernable from the paper. That patients were from a single geographic area and had relatively high education levels (44% with college or above) are among the factors that limit the generalizability of the study. Another limitation is the use of the Beck Depression Inventory, which was not specifically designed for use in the elderly. In addition, the results of this study might have been affected by unmeasured confounding variables, for example daily physical activity, which can be a factor that modifies between depression, cognition, and QOL.

Applications for Clinical Practice

This study reinforces the importance of monitoring older MS patients for factors that may influence their HRQOL. The presence of depression, disability, and cognitive impairment should be assessed for regularly. Clinicians should encourage and empower elderly patients to continue with activities, including employment, that promote their mental and physical well-being and help maintain their independence. Assessing patients with geriatric-specific tools may provide more reliable and accurate assessment data that better accounts for aging dynamics. In addition, comobidities must be managed appropriately.

—Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP, and Allison Squires, PhD, RN, New York University College of Nursing

1. Opara JA, Jaracz K, Brola W. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Med Life 2010;3:352–8.

2. Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:556–66.

3. Benedict RH, Wahlig E, Bakshi R, et al. Predicting quality of life in multiple sclerosis: accounting for physical disability, fatigue, cognition, mood disorder, personality, and behavior change. J Neurol Sci 2005;231:29–34.

4. Göksel Karatepe A, Kaya T, Günaydn R, et al. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue, and disability. Int J Rehabil Res 2011;34:290–8.

5. Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Myhr KM, Nyland HI. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: measuring the disease effects more broadly. Neurology 1999;53:1098–103.

6. Visschedijk MA, Uitdehaag BM, Klein M, et al. Value of health-related quality of life to predict disability course in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2004;63:2046–50.

7. Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, et al. Factors influencing healthy aging with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:26–33.

8. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden LS, et al. Disability in elderly people with multiple sclerosis: An analysis of baseline data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19:55–67.

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the association between clinical and demographic factors and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among older people with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Design. Cross-sectional survey-based study.

Setting and participants. Patients with MS aged 60 years or older were recruited from 4 MS centers in Long Island, NY. Patients with severe cognitive impairment as determined by the health care practitioner were excluded. Participants were asked to complete 3 surveys at 3 different time-points. In the first survey, participants completed the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale and the Patient Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (P-MSNQ). The second survey was the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQOL-54), and the third survey included the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and a disability status self-assessment scale. Cognitive function was measured at the time of recruitment using the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT).

Analysis. The Andersen Healthcare Utilization model was used to structure the multivariate regression analysis. This model identifies multiple domains affecting quality of life, and the variables from the surveys were categorized according to domain: predisposing characteristics (demographic variables), enabling resources (caregiver support and living situation), needs (eg, health-related measures), and health behaviors (medication use, adherence).

Main results. A total of 211 completed the first survey, 188 the second, and 179 the third. 80% were female and 95% were white. Average age was 65.5 (SD 5.6) years. 56% of respondents’ self-reported scores on the SDMT classified them as cognitively impaired. Risk of neuropsychological impairment, depression, and disability status were significantly associated with a decreased mental and physical HRQOL. Significantly, there was a strong association between predisposing characteristics and QOL. Being widowed and remaining employed were the strongest predictors of better physical QOL and having an education level of high school or less was a predictor of lower mental HRQOL.

Conclusion. Clinicians should measure HRQOL in older MS patients regularly and assess for depression and cognitive impairment.

Commentary

Quality of life is an important marker of MS patients’ well-being as they cope with this chronic illness [1]. The progression of the disease and its symptomatology often negatively affect HRQOL. However, multiple psychosocial factors, such as coping, mood, self-efficacy, and perceived support, affect QOL of patients with MS more than biological variables such as weakness or burden of radiologic disease [2]. For example, many self-report HRQOL indices are strongly predicted by measures of depression [3]. In addition, many studies have found a positive association between physical disability and reduced QOL [4,5]. Further, while perceived HRQOL may be a meaningful outcome in itself, it may also be a predictor for outcomes such as disability-related changes [6].

MS leads to disability and loss of function in all age-groups, but only a few studies have focused on HRQOL among elderly patients with MS. As patients with MS age, they may develop comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes that may affect HRQOL. However, in a previous study comparing QOL between older and younger patients with MS, elderly and younger patients with MS had similar QOL even though the elderly patients had more physical limitations [7].

The strength of the current study was using the Andersen Healthcare Utilization regression model in the analysis, since it factors in multiple influences on health status. The striking evidence that employment and being widowed were linked to better physical QOL suggest that older MS patients may have better adaptation and adjustment to their illness. Researchers have shown that the widowed elderly often take on more responsibilities and tasks when they lose their partner, which leads to increased self-esteem and QOL [8]. Another advantage of the study was the fact that the investigators evaluated the different exposure variables and their associations with mental and physical QOL while identifying multiple confounding variables. Additionally, the use of 2 cognitive assessment tools provided a stronger assessment of patients’ cognitive function.

The main weakness of the study was using a cross-sectional study design with convenience sampling. The convenience sample was based on voluntary participation, which may result in self-selection bias. In addition, the self-report design is subject to the usual limitations of self-reporting for data collection: participants may exaggerate symptoms in order to make their situation seem worse or may under-report the severity or frequency of symptoms in order to minimize their problems. While the overall sample size was 211, not all respondents completed all the surveys, and response rates varied by questions. Thus, missing data may have affected results, but which data are missing is not discernable from the paper. That patients were from a single geographic area and had relatively high education levels (44% with college or above) are among the factors that limit the generalizability of the study. Another limitation is the use of the Beck Depression Inventory, which was not specifically designed for use in the elderly. In addition, the results of this study might have been affected by unmeasured confounding variables, for example daily physical activity, which can be a factor that modifies between depression, cognition, and QOL.

Applications for Clinical Practice

This study reinforces the importance of monitoring older MS patients for factors that may influence their HRQOL. The presence of depression, disability, and cognitive impairment should be assessed for regularly. Clinicians should encourage and empower elderly patients to continue with activities, including employment, that promote their mental and physical well-being and help maintain their independence. Assessing patients with geriatric-specific tools may provide more reliable and accurate assessment data that better accounts for aging dynamics. In addition, comobidities must be managed appropriately.

—Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP, and Allison Squires, PhD, RN, New York University College of Nursing

Study Overview

Objective. To evaluate the association between clinical and demographic factors and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among older people with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Design. Cross-sectional survey-based study.

Setting and participants. Patients with MS aged 60 years or older were recruited from 4 MS centers in Long Island, NY. Patients with severe cognitive impairment as determined by the health care practitioner were excluded. Participants were asked to complete 3 surveys at 3 different time-points. In the first survey, participants completed the Morisky Medication Adherence Scale and the Patient Multiple Sclerosis Neuropsychological Screening Questionnaire (P-MSNQ). The second survey was the Multiple Sclerosis Quality of Life-54 (MSQOL-54), and the third survey included the Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) and a disability status self-assessment scale. Cognitive function was measured at the time of recruitment using the Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT).

Analysis. The Andersen Healthcare Utilization model was used to structure the multivariate regression analysis. This model identifies multiple domains affecting quality of life, and the variables from the surveys were categorized according to domain: predisposing characteristics (demographic variables), enabling resources (caregiver support and living situation), needs (eg, health-related measures), and health behaviors (medication use, adherence).

Main results. A total of 211 completed the first survey, 188 the second, and 179 the third. 80% were female and 95% were white. Average age was 65.5 (SD 5.6) years. 56% of respondents’ self-reported scores on the SDMT classified them as cognitively impaired. Risk of neuropsychological impairment, depression, and disability status were significantly associated with a decreased mental and physical HRQOL. Significantly, there was a strong association between predisposing characteristics and QOL. Being widowed and remaining employed were the strongest predictors of better physical QOL and having an education level of high school or less was a predictor of lower mental HRQOL.

Conclusion. Clinicians should measure HRQOL in older MS patients regularly and assess for depression and cognitive impairment.

Commentary

Quality of life is an important marker of MS patients’ well-being as they cope with this chronic illness [1]. The progression of the disease and its symptomatology often negatively affect HRQOL. However, multiple psychosocial factors, such as coping, mood, self-efficacy, and perceived support, affect QOL of patients with MS more than biological variables such as weakness or burden of radiologic disease [2]. For example, many self-report HRQOL indices are strongly predicted by measures of depression [3]. In addition, many studies have found a positive association between physical disability and reduced QOL [4,5]. Further, while perceived HRQOL may be a meaningful outcome in itself, it may also be a predictor for outcomes such as disability-related changes [6].

MS leads to disability and loss of function in all age-groups, but only a few studies have focused on HRQOL among elderly patients with MS. As patients with MS age, they may develop comorbidities such as hypertension and diabetes that may affect HRQOL. However, in a previous study comparing QOL between older and younger patients with MS, elderly and younger patients with MS had similar QOL even though the elderly patients had more physical limitations [7].

The strength of the current study was using the Andersen Healthcare Utilization regression model in the analysis, since it factors in multiple influences on health status. The striking evidence that employment and being widowed were linked to better physical QOL suggest that older MS patients may have better adaptation and adjustment to their illness. Researchers have shown that the widowed elderly often take on more responsibilities and tasks when they lose their partner, which leads to increased self-esteem and QOL [8]. Another advantage of the study was the fact that the investigators evaluated the different exposure variables and their associations with mental and physical QOL while identifying multiple confounding variables. Additionally, the use of 2 cognitive assessment tools provided a stronger assessment of patients’ cognitive function.

The main weakness of the study was using a cross-sectional study design with convenience sampling. The convenience sample was based on voluntary participation, which may result in self-selection bias. In addition, the self-report design is subject to the usual limitations of self-reporting for data collection: participants may exaggerate symptoms in order to make their situation seem worse or may under-report the severity or frequency of symptoms in order to minimize their problems. While the overall sample size was 211, not all respondents completed all the surveys, and response rates varied by questions. Thus, missing data may have affected results, but which data are missing is not discernable from the paper. That patients were from a single geographic area and had relatively high education levels (44% with college or above) are among the factors that limit the generalizability of the study. Another limitation is the use of the Beck Depression Inventory, which was not specifically designed for use in the elderly. In addition, the results of this study might have been affected by unmeasured confounding variables, for example daily physical activity, which can be a factor that modifies between depression, cognition, and QOL.

Applications for Clinical Practice

This study reinforces the importance of monitoring older MS patients for factors that may influence their HRQOL. The presence of depression, disability, and cognitive impairment should be assessed for regularly. Clinicians should encourage and empower elderly patients to continue with activities, including employment, that promote their mental and physical well-being and help maintain their independence. Assessing patients with geriatric-specific tools may provide more reliable and accurate assessment data that better accounts for aging dynamics. In addition, comobidities must be managed appropriately.

—Aliza Bitton Ben-Zacharia, DNP, ANP, and Allison Squires, PhD, RN, New York University College of Nursing

1. Opara JA, Jaracz K, Brola W. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Med Life 2010;3:352–8.

2. Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:556–66.

3. Benedict RH, Wahlig E, Bakshi R, et al. Predicting quality of life in multiple sclerosis: accounting for physical disability, fatigue, cognition, mood disorder, personality, and behavior change. J Neurol Sci 2005;231:29–34.

4. Göksel Karatepe A, Kaya T, Günaydn R, et al. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue, and disability. Int J Rehabil Res 2011;34:290–8.

5. Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Myhr KM, Nyland HI. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: measuring the disease effects more broadly. Neurology 1999;53:1098–103.

6. Visschedijk MA, Uitdehaag BM, Klein M, et al. Value of health-related quality of life to predict disability course in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2004;63:2046–50.

7. Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, et al. Factors influencing healthy aging with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:26–33.

8. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden LS, et al. Disability in elderly people with multiple sclerosis: An analysis of baseline data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19:55–67.

1. Opara JA, Jaracz K, Brola W. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. J Med Life 2010;3:352–8.

2. Mitchell AJ, Benito-León J, González JM, Rivera-Navarro J. Quality of life and its assessment in multiple sclerosis: integrating physical and psychological components of wellbeing. Lancet Neurol 2005;4:556–66.

3. Benedict RH, Wahlig E, Bakshi R, et al. Predicting quality of life in multiple sclerosis: accounting for physical disability, fatigue, cognition, mood disorder, personality, and behavior change. J Neurol Sci 2005;231:29–34.

4. Göksel Karatepe A, Kaya T, Günaydn R, et al. Quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis: the impact of depression, fatigue, and disability. Int J Rehabil Res 2011;34:290–8.

5. Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Myhr KM, Nyland HI. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis: measuring the disease effects more broadly. Neurology 1999;53:1098–103.

6. Visschedijk MA, Uitdehaag BM, Klein M, et al. Value of health-related quality of life to predict disability course in multiple sclerosis. Neurology 2004;63:2046–50.

7. Ploughman M, Austin MW, Murdoch M, et al. Factors influencing healthy aging with multiple sclerosis: a qualitative study. Disabil Rehabil 2012;34:26–33.

8. Minden SL, Frankel D, Hadden LS, et al. Disability in elderly people with multiple sclerosis: An analysis of baseline data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. NeuroRehabilitation. 2004;19:55–67.