User login

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

The US health care system presents major administrative burdens—particularly in coding, billing, and reimbursement—that impact clinical efficiency and patient access. Dermatologists have experienced disproportionate reimbursement declines. A longitudinal review of 20 dermatologic service codes found a 10% average decline in Medicare reimbursement between 2000 and 2020.1 A recent cross-sectional study showed a 4.7% average decline in reimbursement rates from 2007 to 2021 for commonly performed dermatologic procedures, with variation across procedure categories.2 These reductions threaten practice sustainability and highlight the urgent need for comprehensive, long-term payment reform to preserve access to high-quality dermatologic care.

In dermatopathology, policy changes to reimbursement and laboratory oversight directly impact practice operations. Specialty-specific advocacy remains vital in driving policy changes. In this article, we highlight a recent advocacy win—the reversal of immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain denials—and provide updates on a new position statement on IHC guidance. We also outline regulatory changes to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988 and College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory director requirements and emphasize the importance of continued legislative advocacy.

Reversal of Reimbursement Denials for IHC Stains

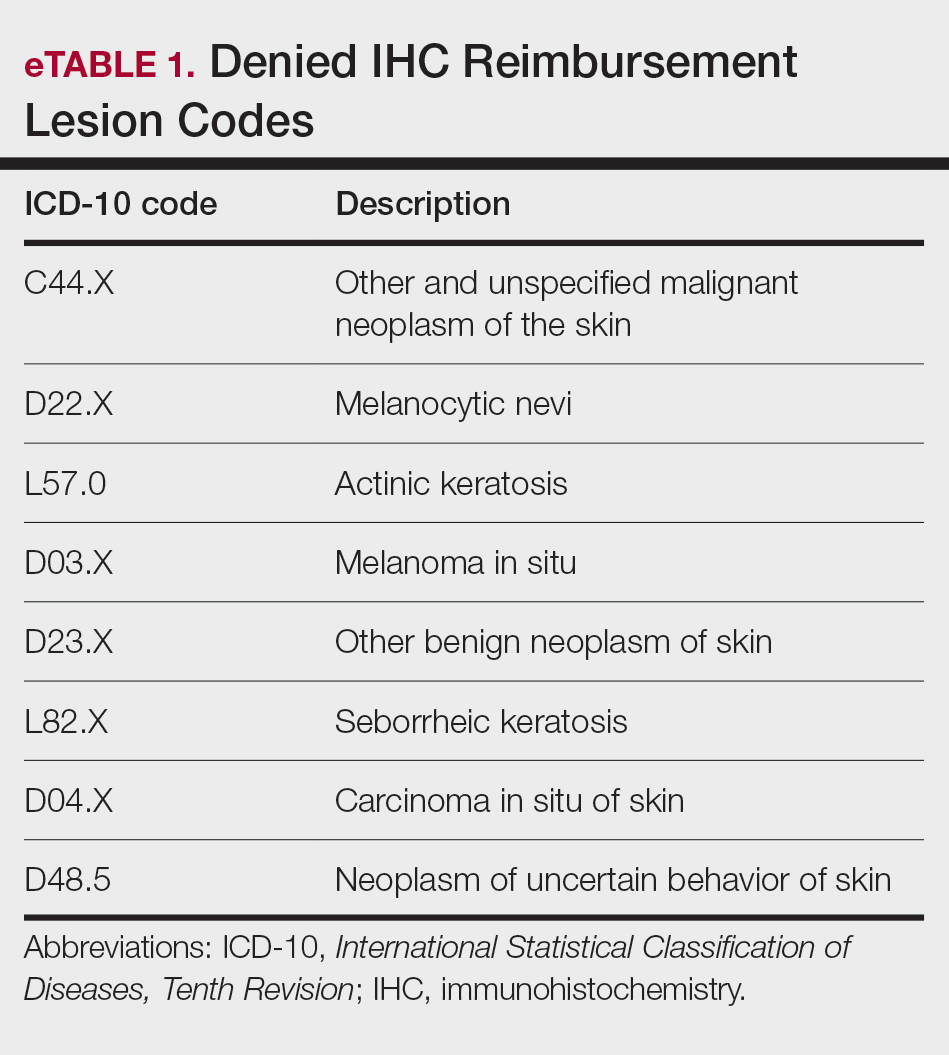

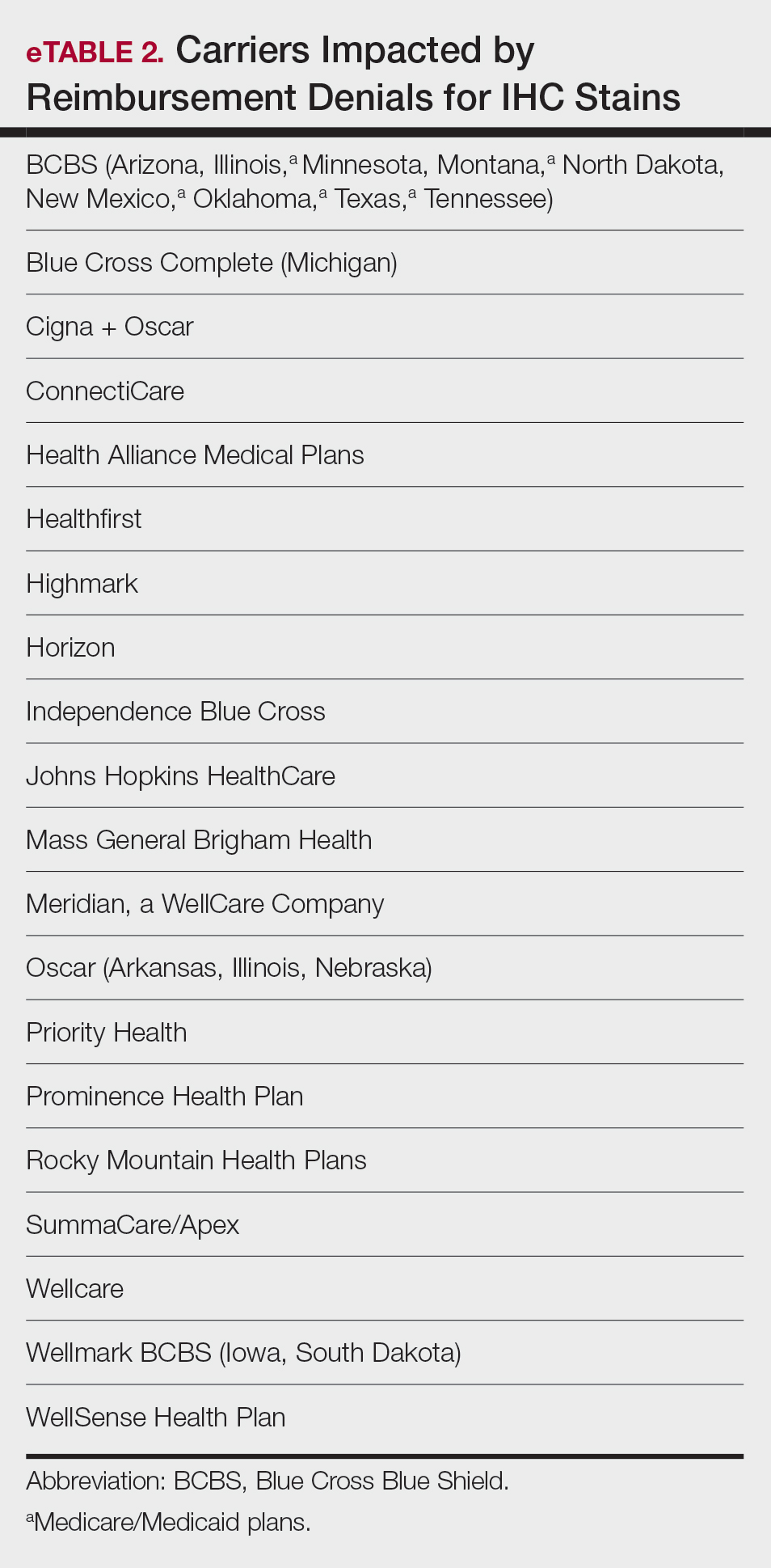

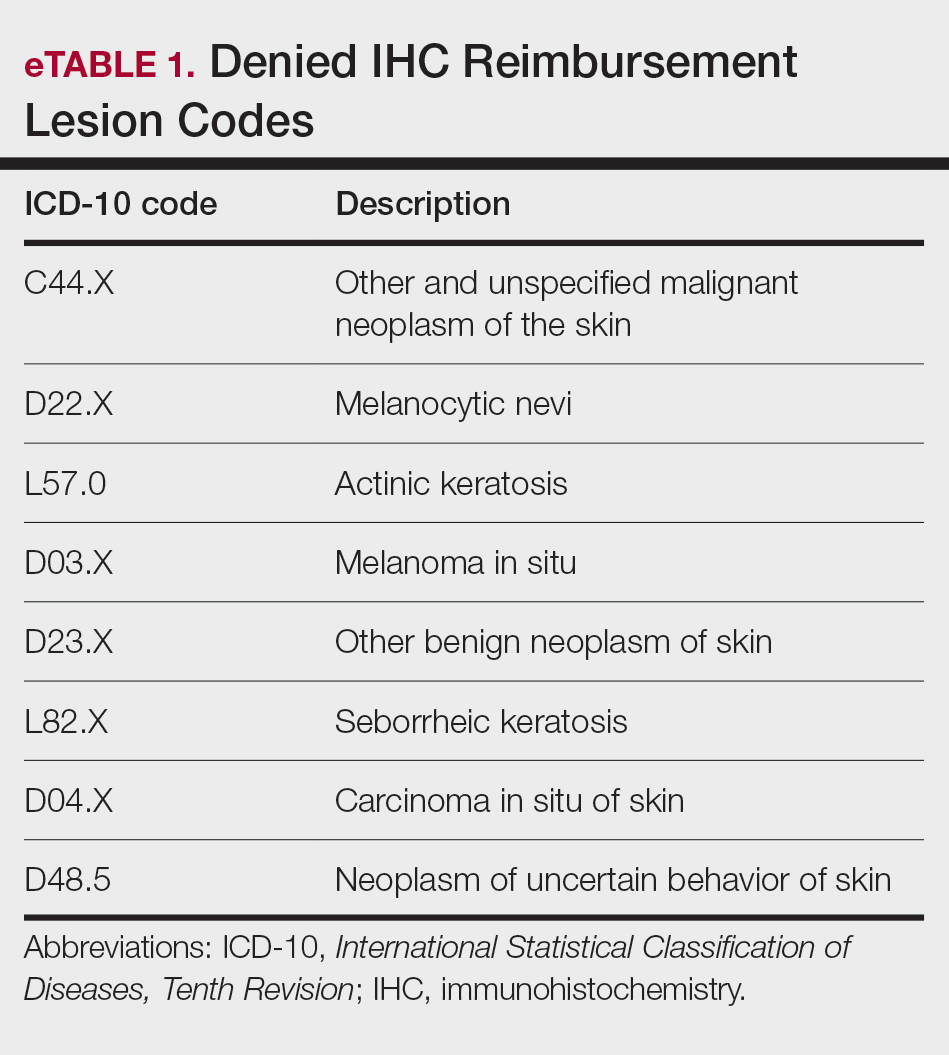

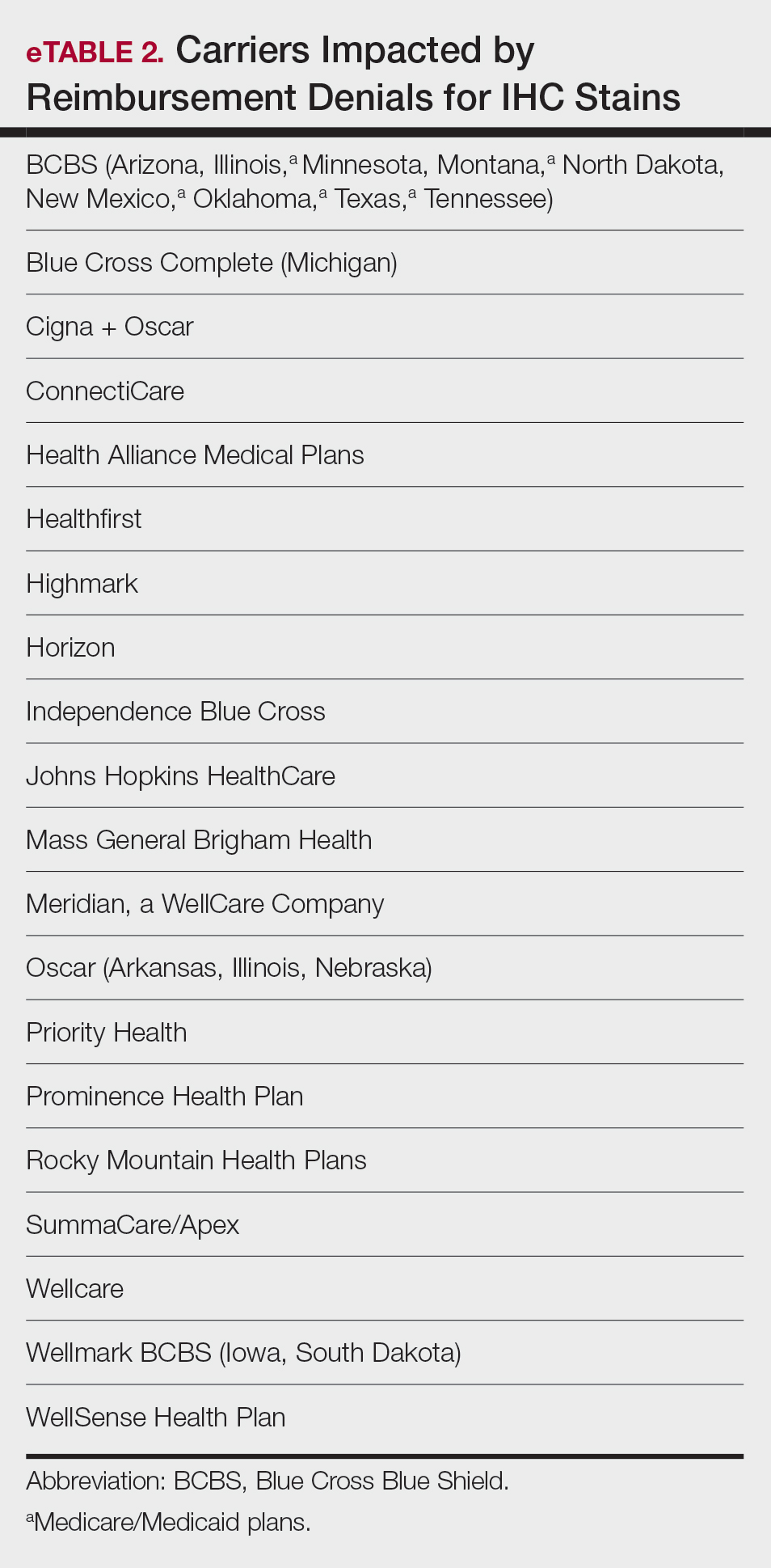

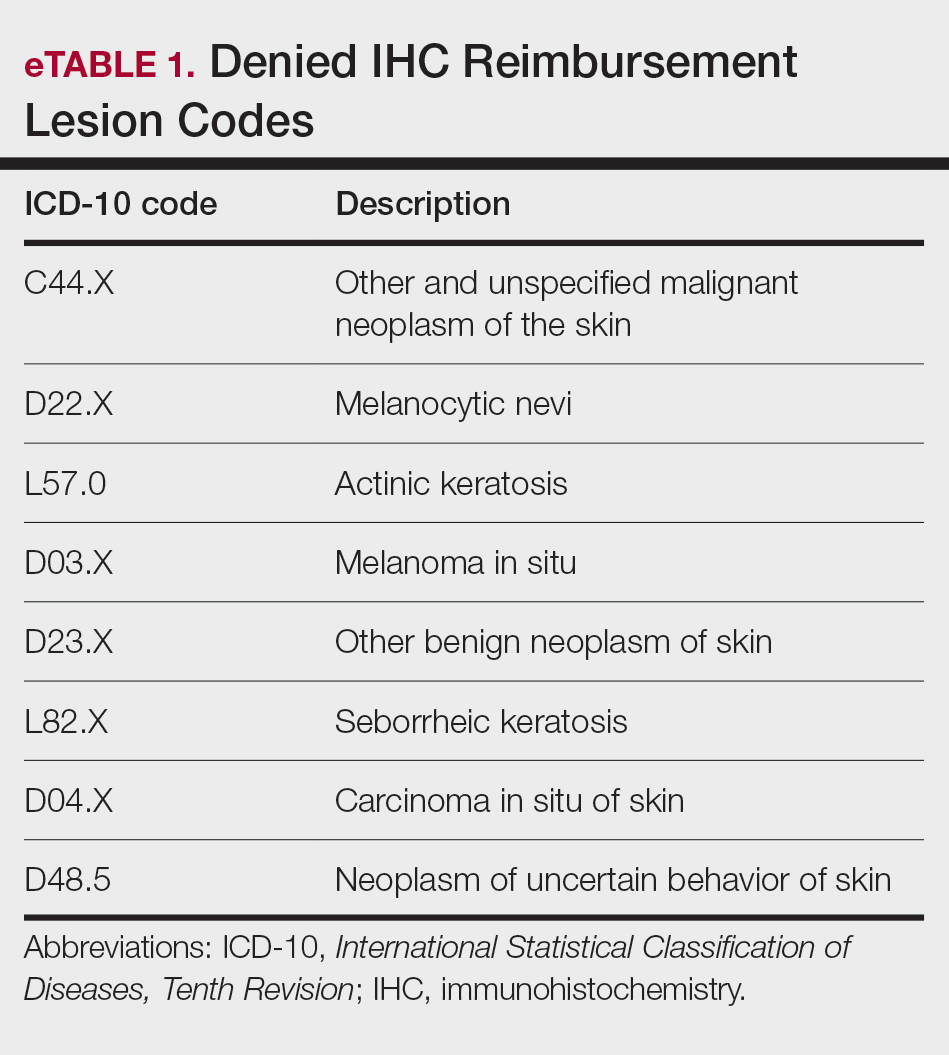

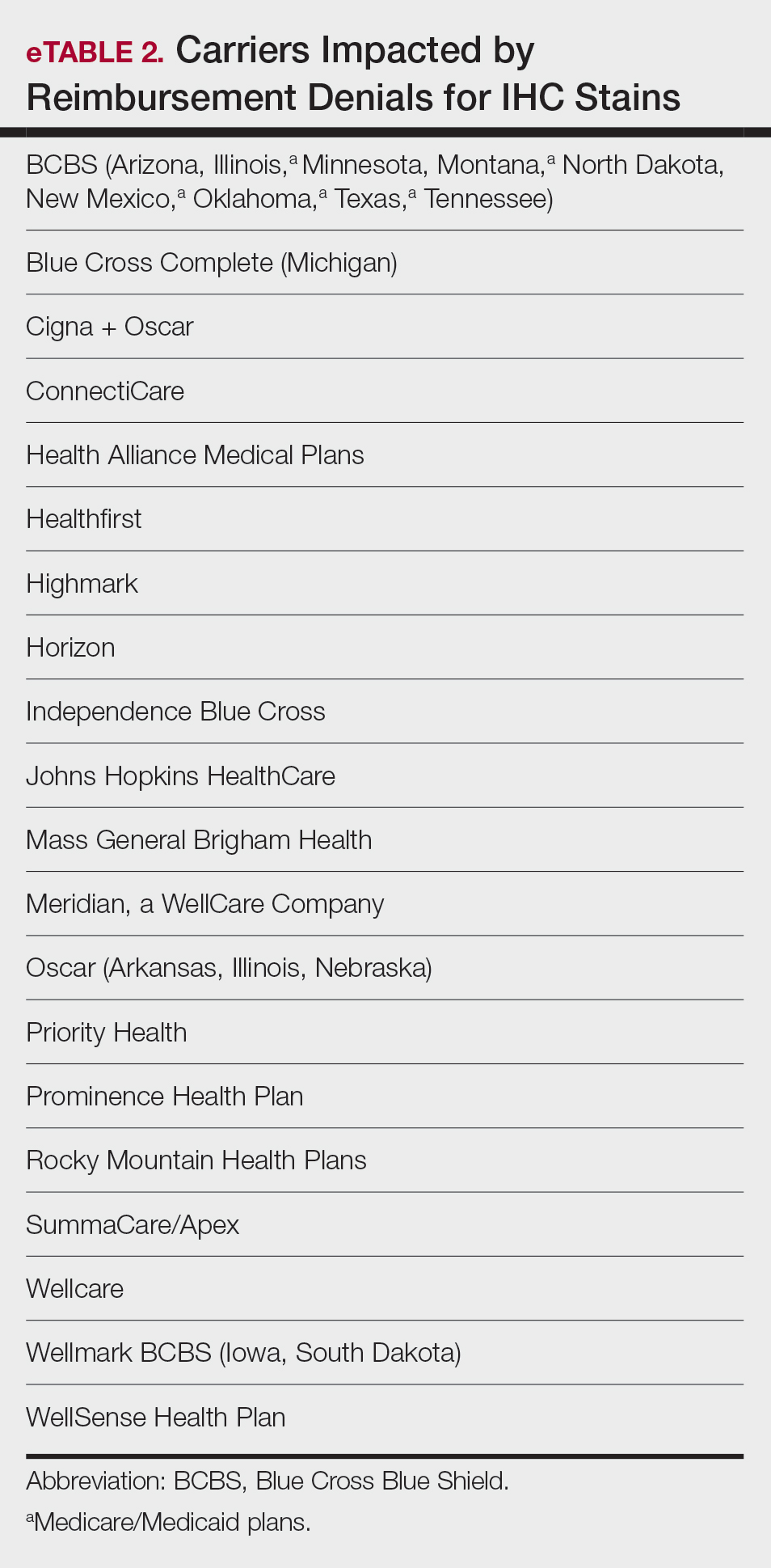

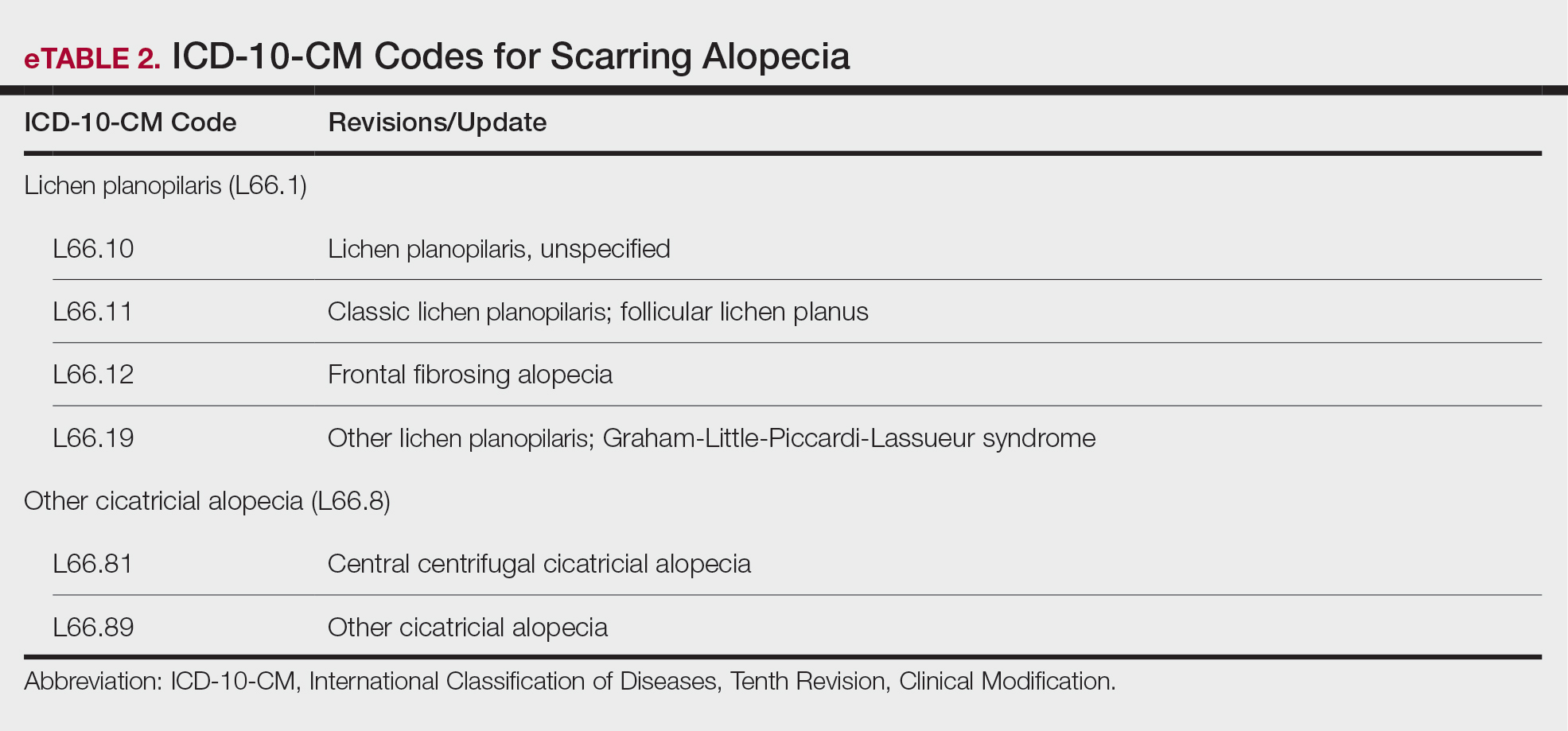

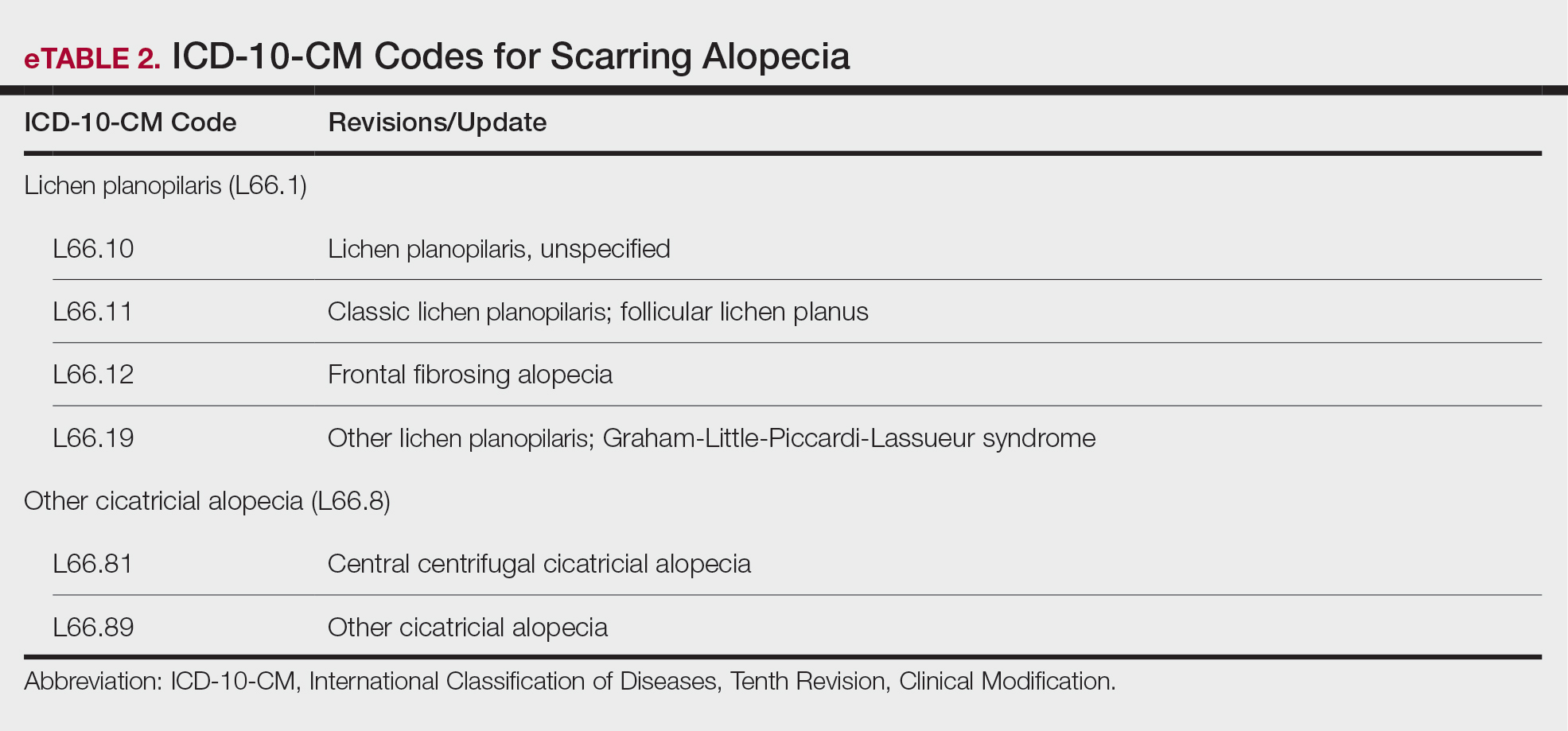

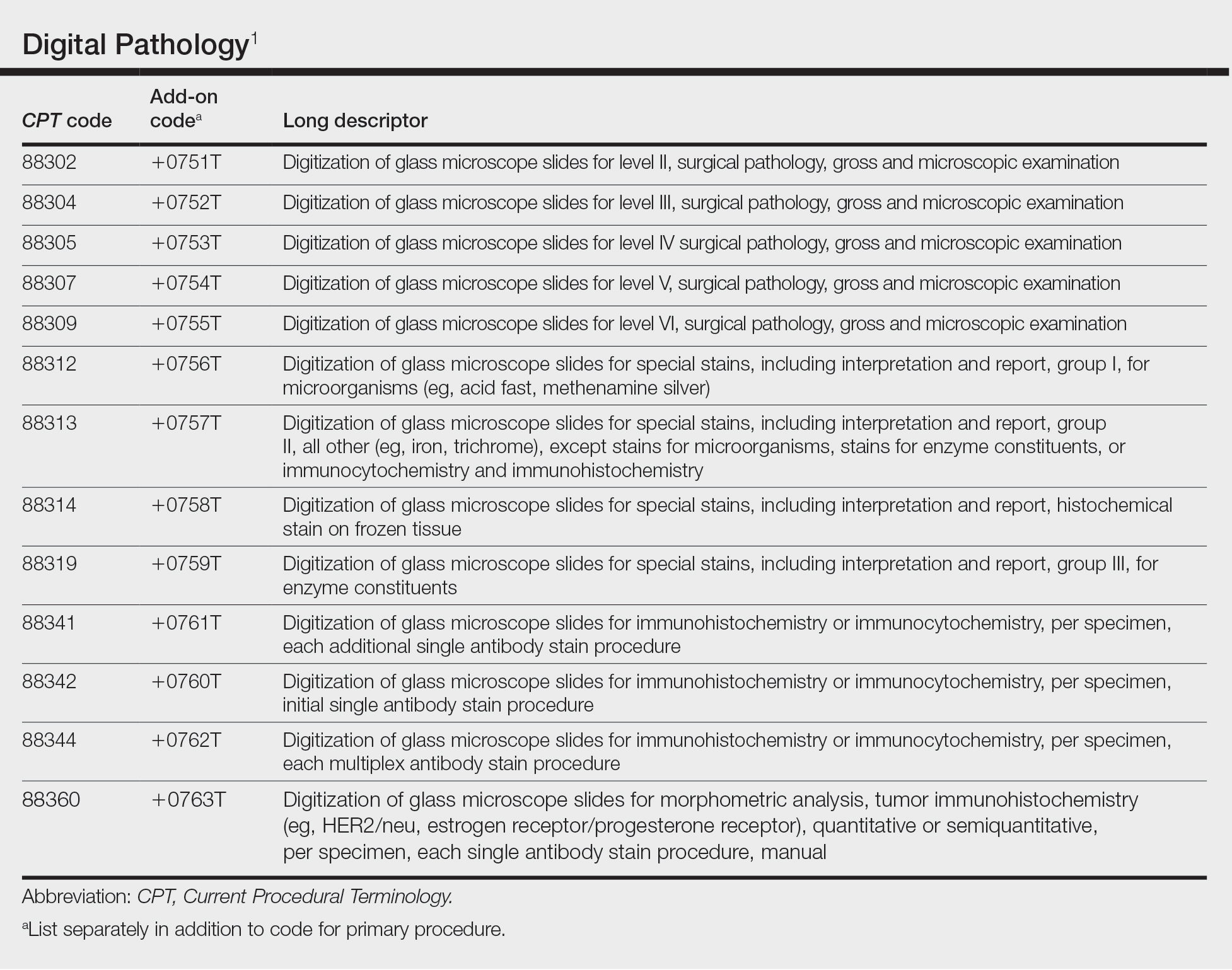

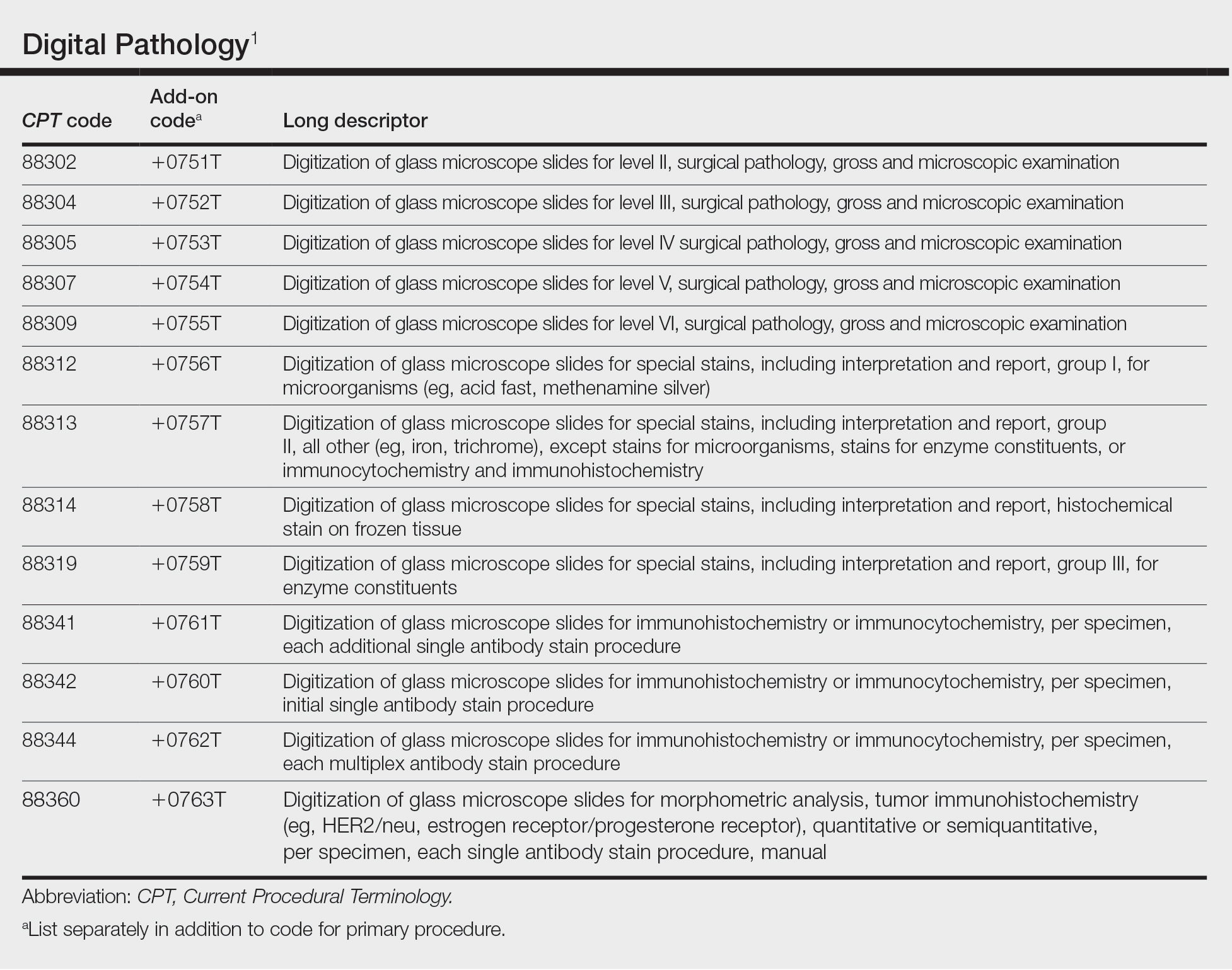

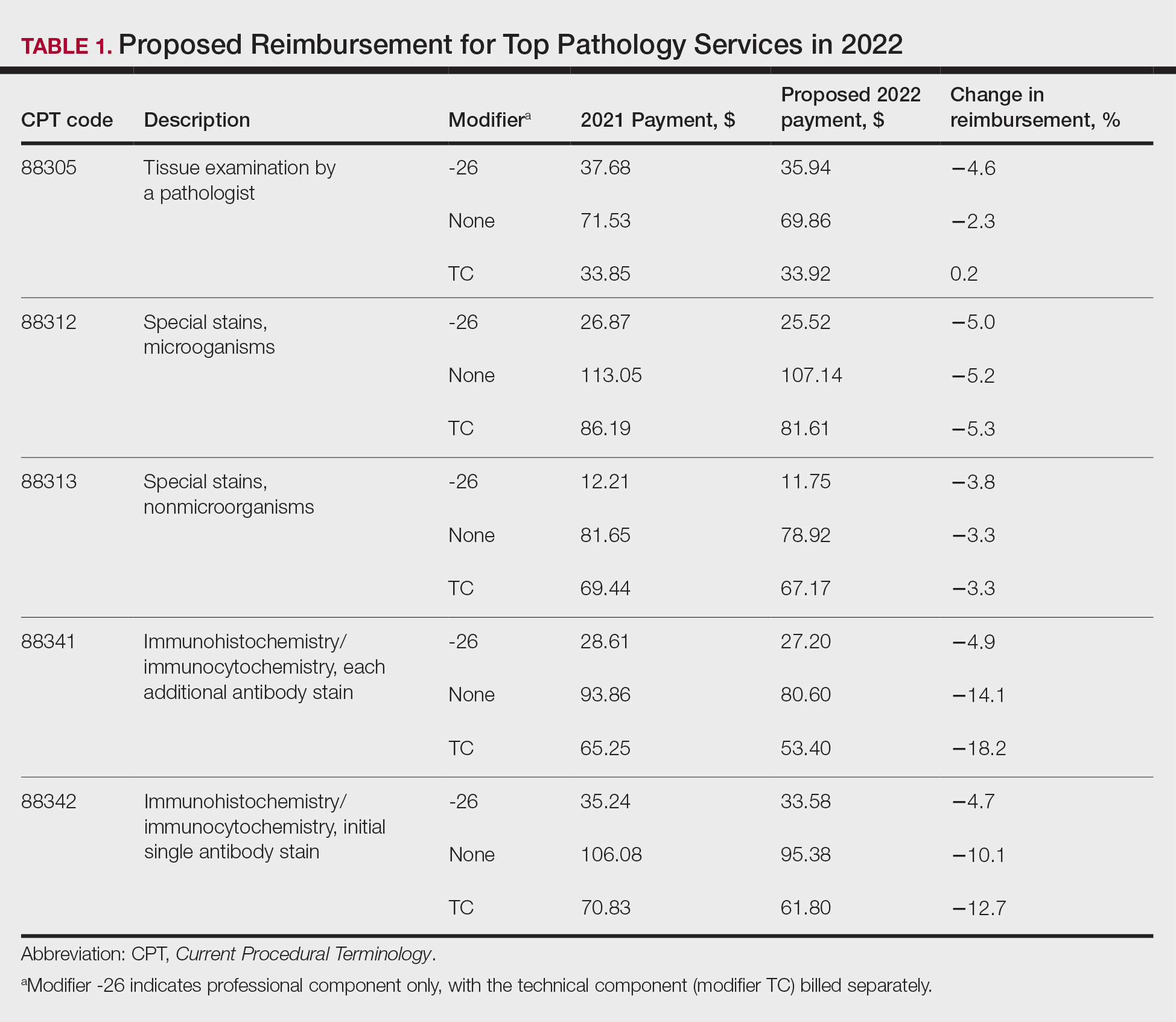

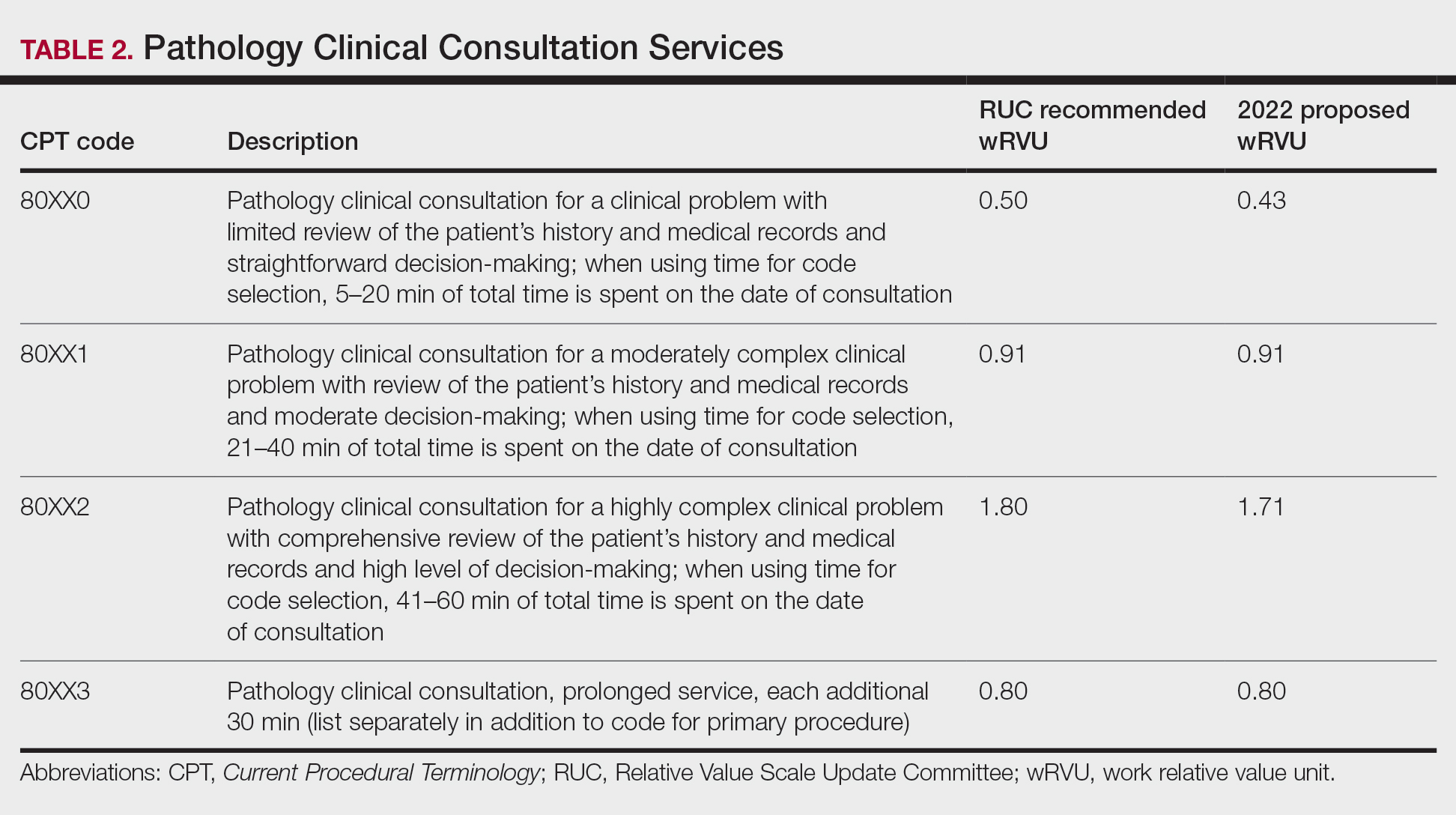

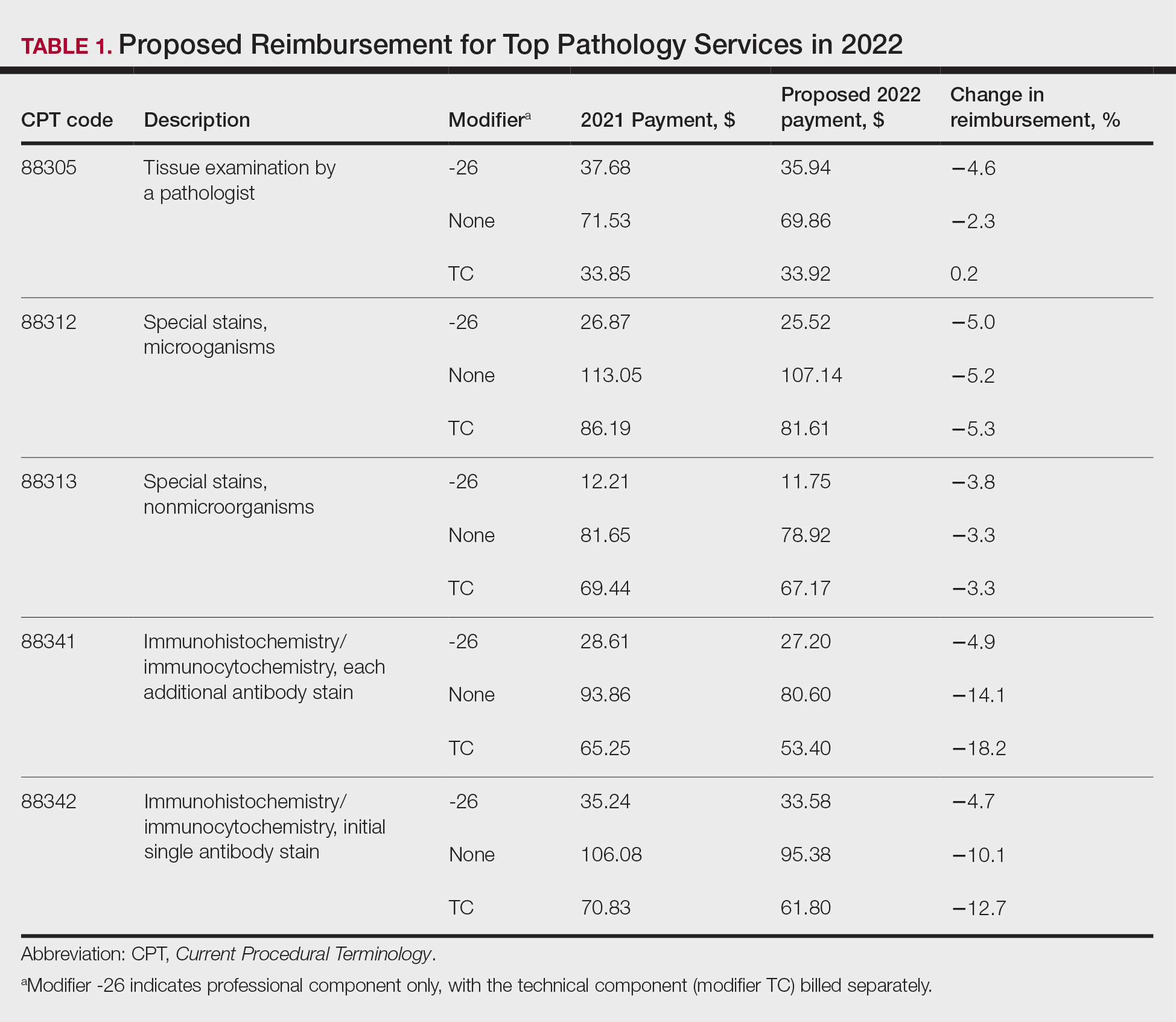

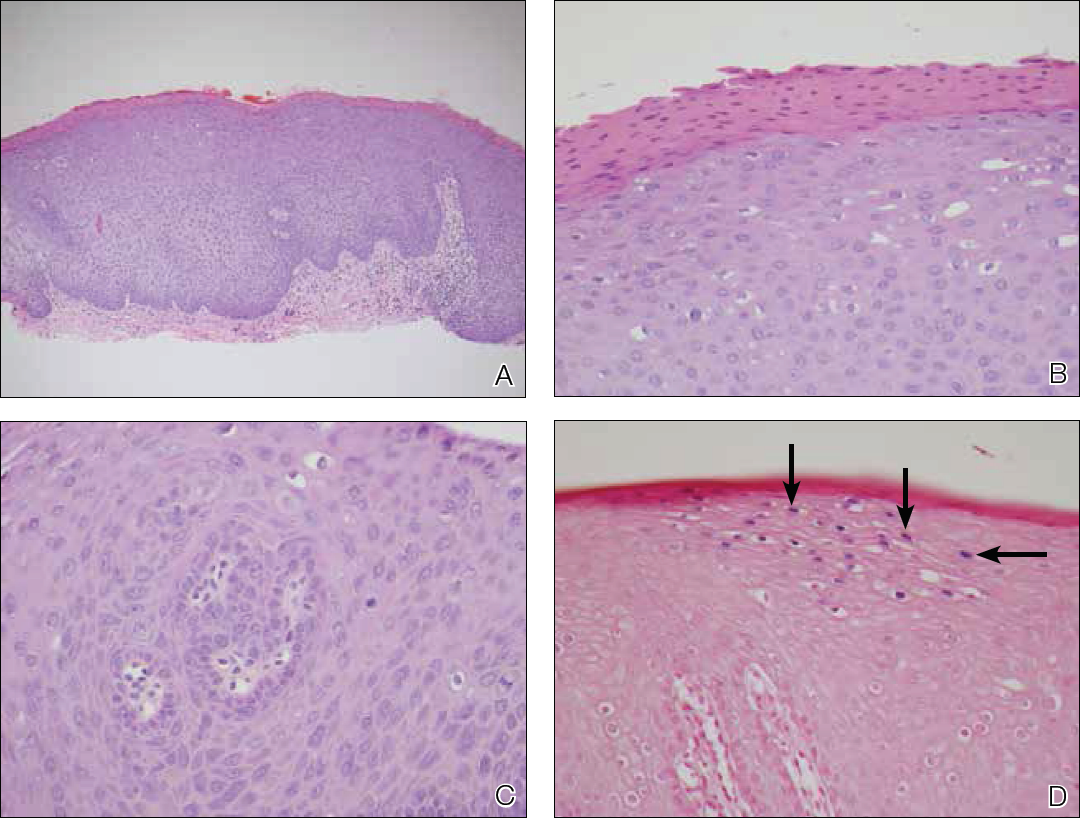

EviCore, a medical benefits management company serving over one-third of insured individuals in the United States, is hired by an extensive network of insurance companies to develop clinical and laboratory guidelines and utilization and payment integrity programs.3 EviCore’s laboratory management guidelines for 2024 denied IHC stains (Current Procedural Terminology codes 88341 and 88342) as not medically necessary when associated with specific International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, skin lesion codes (eTable 1).3-5 These policies caused major disruption to dermatopathology services nationwide, impacting both academic and private laboratories (eTable 2).5 The implementation of such blanket denials interferes with clinical decision-making, compromising diagnostic quality by restricting medically necessary and essential laboratory and pathology services. The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) and CAP leadership formally objected to the policy, citing how these reimbursement denials fail to account for the importance of clinical judgment and diagnostic nuance.6

Thanks to broad advocacy efforts, EviCore updated its guidelines effective January 1, 2025. The skin-related International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were removed from IHC coverage restrictions, with automatic payment reinstated retroactive to March 15, 2024. EviCore also rescinded language denying reimbursement if a diagnosis could be made without the use of IHC stains.7 While this reversal is a notable achievement, ongoing monitoring of emerging trends in claim denials remains crucial. Continued advocacy, proper documentation, and adherence to American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) Appropriate Use Criteria is essential to protecting clinical autonomy.

The AADA’s Dermatopathology Committee developed a new position statement on IHC utilization supporting the advocacy efforts with payers, who recently have tried to implement restrictive limitations.8 Immunohistochemistry is considered a valuable tool for dermatopathology diagnosis, and its utility aids in the confirmation, exclusion, or change in diagnosis.9 By clearly outlining the clinical value of IHC in dermatopathology, this statement reinforces the need to advocate against restrictive payer policies to preserve physician autonomy and promote appropriate, evidence-based use of IHC stains.8

In addition, the ASDP Standards of Practice Committee is working with the Johns Hopkins–Global Appropriateness Measures data-powered analytics platform to develop physician-led IHC benchmarks. The ASDP Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application is a valuable clinical tool for dermatopathologists, general pathologists, dermatologists, and other providers, offering case-based recommendations for test utilization grounded in current evidence.9

Legislative Advocacy: Support for H.R. 879

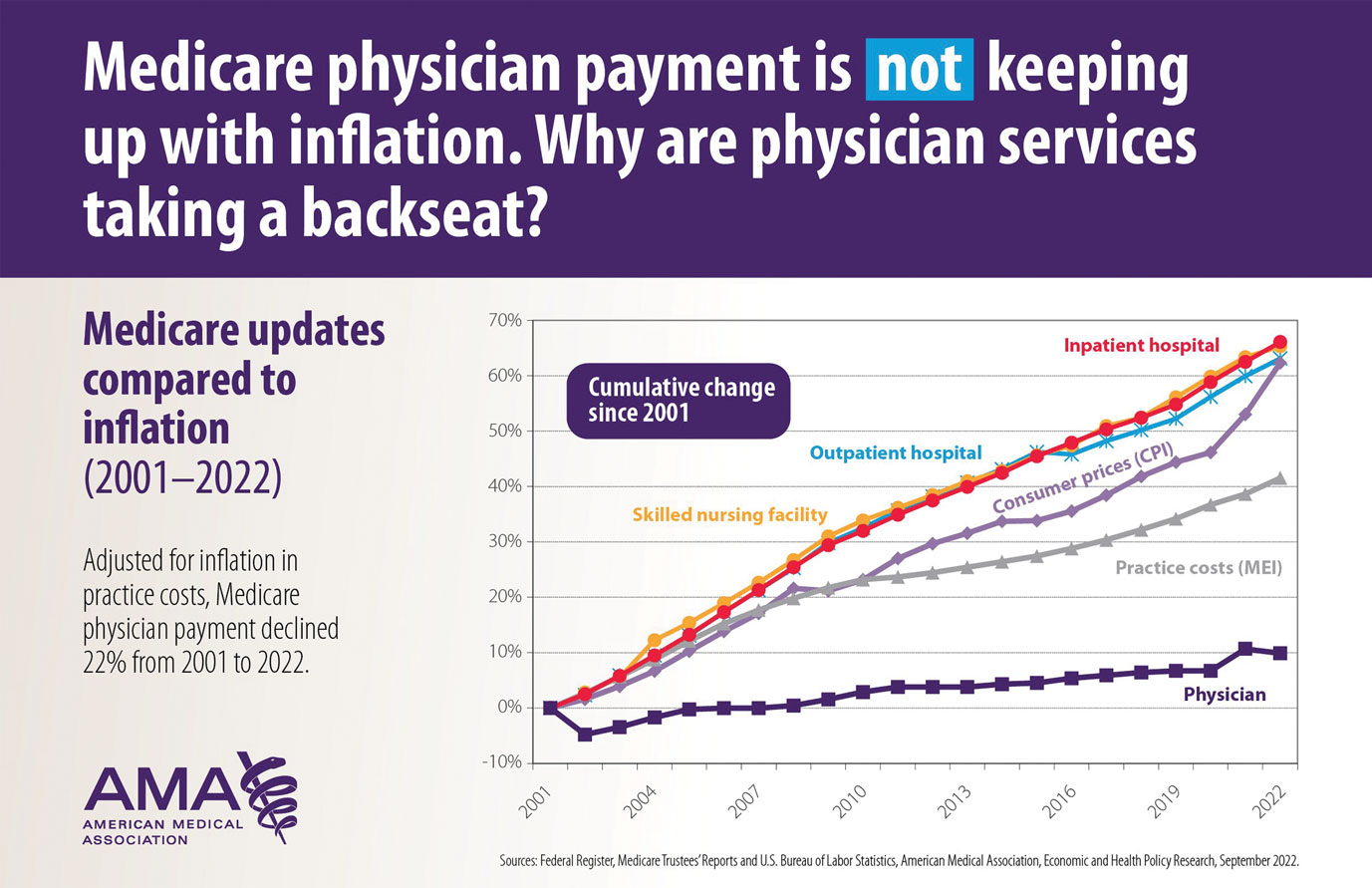

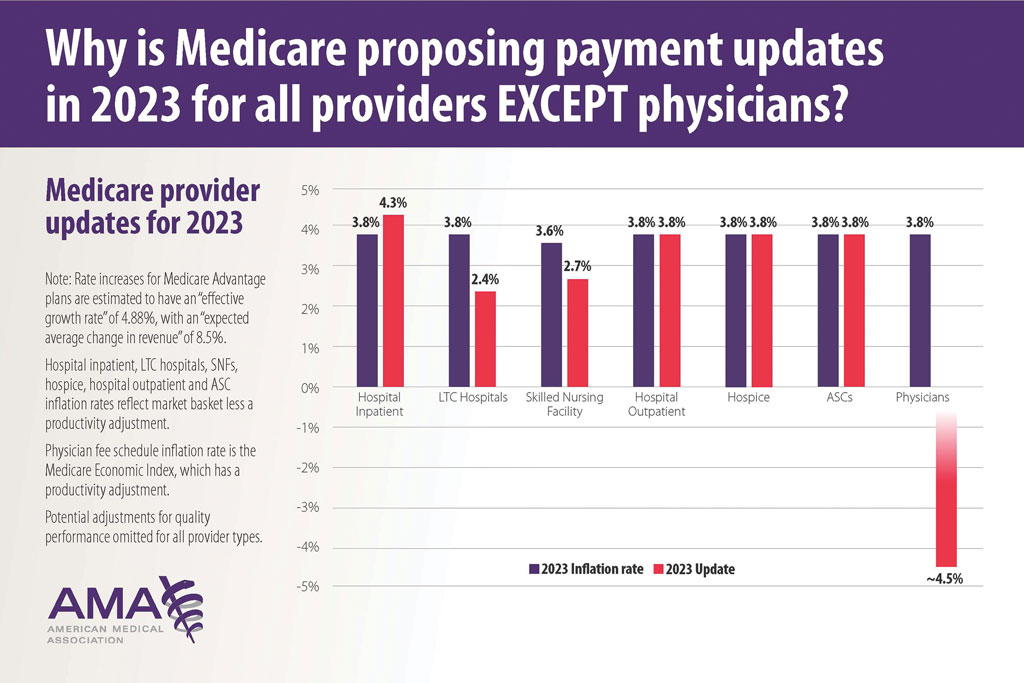

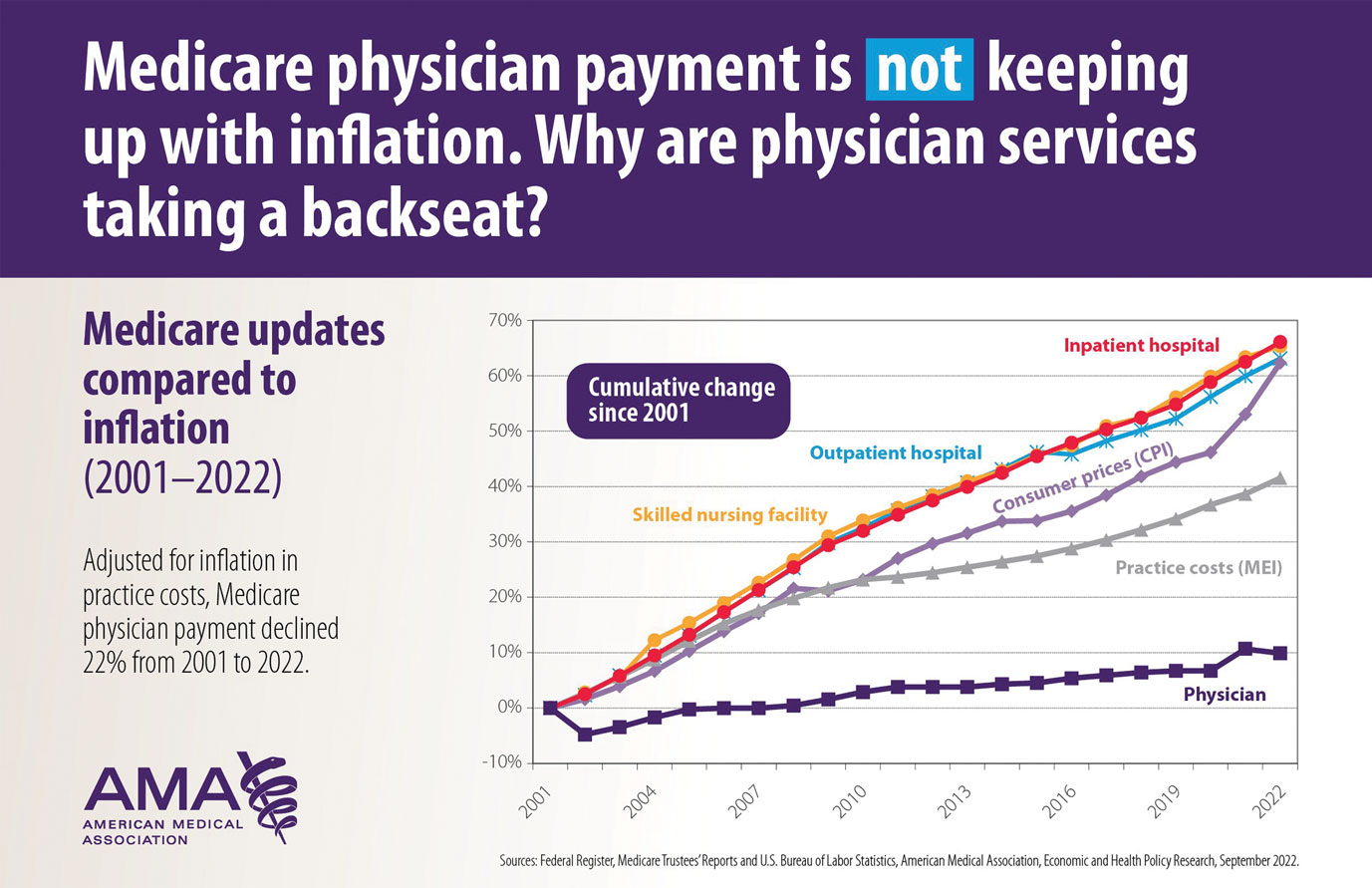

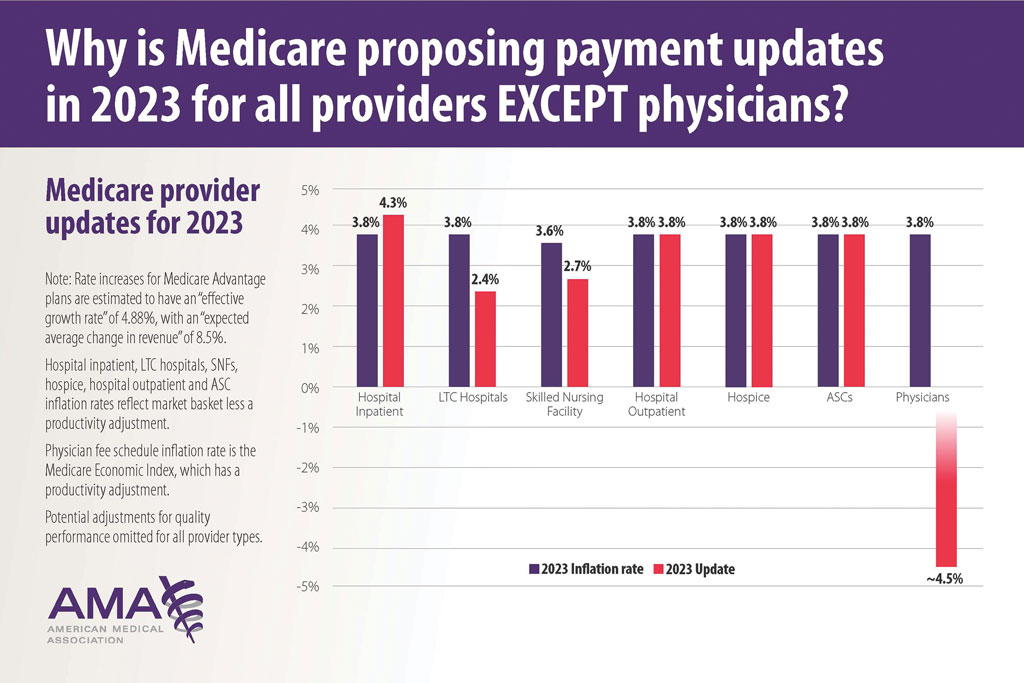

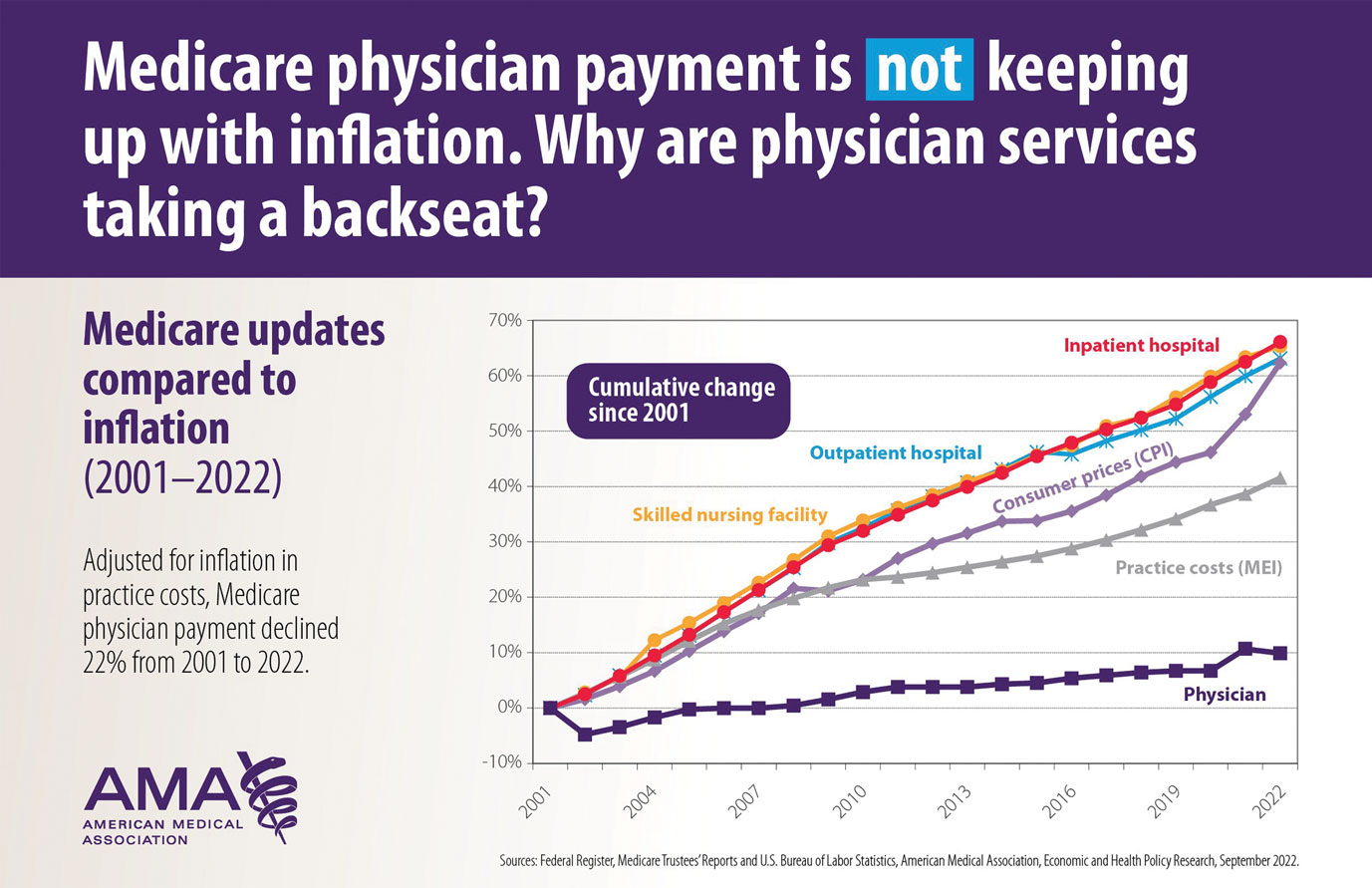

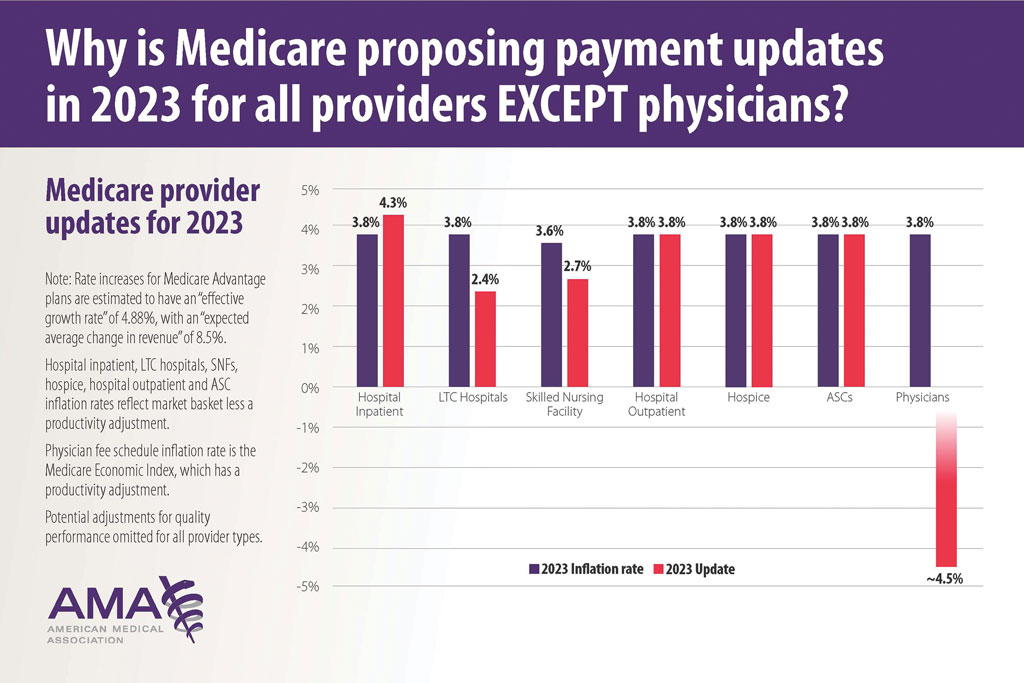

Physician payment cuts have reached a critical tipping point. Since 2001, physicians have experienced a 33% average reduction in Medicare reimbursement, unadjusted for inflation or rising overhead.10 In January 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposed a further 2.83% cut, despite projecting a 3.5% increase in the Medicare Economic Index.11,12 Dermatologists and other physician groups cannot continue to absorb these reductions, as they have several consequences, including the inability to maintain practices, forcing some physicians out of business, driving health care consolidation, and limiting patient access.

The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act (H.R. 879)13 is bipartisan legislation that seeks to stop the 2.8% Medicare physician payment cut that went into effect in January 2025, provide physicians with an additional 2% inflation-adjusted payment increase for 2025, and help stabilize Medicare reimbursement rates.13,14 As the impact of continued cuts threatens both patient access and practice viability, member engagement is essential to advancing federal physician payment reform. To support sustainable payment reform and protect access to care, visit the AADA Advocacy Action Center online.14

2025 CLIA and CAP Laboratory Director Requirements: What’s Changing?

As of December 28, 2024, updated CLIA regulations took effect for all laboratories performing moderate- or high-complexity testing. These revisions aim to modernize outdated requirements and update regulations to incorporate technological advancements such as automation and artificial intelligence.15 New CLIA standards require laboratory directors with Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathy degrees to be certified in anatomic and/or clinical pathology by the American Board of Pathology or the American Osteopathic Board of Pathology.15 For physicians who do not hold these board-certified qualifications, there are alternative pathways to becoming a laboratory director based on experience and education for physicians licensed to practice in the jurisdiction where the laboratory is located. For high-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 2 years of experience directing or supervising high-complexity testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities. For moderate-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 1 year of experience supervising nonwaived laboratory testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities.16

If the current laboratory director is not board certified in pathology, the new regulation will permit the grandfathering of current laboratory directors if existing laboratory directors have remained continuously employed in their current role since December 28, 2024.16 Therefore, individuals who were already employed in qualifying positions as of December 28, 2024, will be grandfathered in and will not need to meet the new educational requirements if they remain employed without interruption. All individuals qualifying after December 28, 2024, will be required to do so under the new provisions stated earlier.

The CMS updated laboratory personnel requirements, thereby impacting all CLIA-certified laboratories and those seeking CLIA certification. Likewise, laboratories seeking accreditation by the CAP must meet the new laboratory personnel requirements.17 In some cases, CAP requirements are more stringent than the CLIA regulations (CAP accreditation is more stringent in areas of quality control, personnel qualifications, proficiency testing, and in oversight of laboratory developed tests).15-17 If more stringent state or local regulations are in place for personnel qualifications, including requirements for state licensure, they must be followed.

The AADA formed an ad hoc workgroup to address the CLIA laboratory director requirements and is actively engaging CMS to amend these requirements immediately. Formal objections have been submitted, and direct dialogue with CMS leadership is under way in collaboration with the American Board of Dermatology and leading dermatology and pathology societies.

Final Thoughts

Advocacy remains essential to the future of dermatology. From payer policy reversals to laboratory compliance reforms and federal payment advocacy, physicians must remain engaged. Whether it is safeguarding diagnostic autonomy or securing financial sustainability, we must continue to put “skin in the game.”

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358.

- Miller TC, Rucker P, Armstrong D. “Not medically necessary”: inside the company helping America’s biggest health insurers deny coverage for care. ProPublica. October 23, 2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/evicore-health-insurance-denials-cigna-unitedhealthcare-aetna-prior-authorizations

- EviCore healthcare. Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/MOL.CS_.104.A_Immunohistochemistry%20%28IHC%29_V2.0.2024_eff11.01.2024_pub12.31.2024.pdf

- EviCore. Laboratory management. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/provider/clinical-guidelines-details?solution=laboratory%20management

- Saad AJ. College of American Pathologists. December 12, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents /Wellmark-Letter- https://documents.cap.org/documents/wellmarkcap-letter2023.pdf

- EviCore healthcare. Clinical Guidelines: Lab Management Program. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/Cigna_LabMgmt_V1.0.2025_eff01.01.2025_pub08.22.2024_0.pdf

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on immunohistochemistry utilization. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://server.aad.org/forms/policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Immunohistochemistry%20Utilization.pdf

- Naert KA, Trotter MJ. Utilization and utility of immunohistochemistry in dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:74-77.

- American Medical Association. Medicare physician payment continues to fall further behind practice cost inflation. Accessed April 23, 2025. https:// www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2025-medicare-updates-inflation-chart.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule

- American Medical Association. The Medicare Economic Index. Accessed April 23 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-basics-medicare-economic-index.pdf

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act, HR 879, 119th Cong (2025). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/879

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) fees; histocompatibility, personnel, and alternative sanctions for certificate of waiver laboratories. Fed Regist. 2023;88:89976-90044.

- College of American Pathologists. CAP accreditation checklists – 2024 edition. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents/2024-Checklist-Summary.pdf?_gl=1*1b4rei9*_ga*NDc0NjYwNjM5LjE3NDQ3NTI4NjA.*_ga_97ZFJSQQ0X*MTc0NDc2OTc3My40LjEuMTc0NDc2OTgyOC4wLjAuMA

- Bennett SA, Conn CM, Gill HE, et al. Regulatory requirements for laboratory developed tests in the United States. J Immunol Methods. 2025;537:113813.

The US health care system presents major administrative burdens—particularly in coding, billing, and reimbursement—that impact clinical efficiency and patient access. Dermatologists have experienced disproportionate reimbursement declines. A longitudinal review of 20 dermatologic service codes found a 10% average decline in Medicare reimbursement between 2000 and 2020.1 A recent cross-sectional study showed a 4.7% average decline in reimbursement rates from 2007 to 2021 for commonly performed dermatologic procedures, with variation across procedure categories.2 These reductions threaten practice sustainability and highlight the urgent need for comprehensive, long-term payment reform to preserve access to high-quality dermatologic care.

In dermatopathology, policy changes to reimbursement and laboratory oversight directly impact practice operations. Specialty-specific advocacy remains vital in driving policy changes. In this article, we highlight a recent advocacy win—the reversal of immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain denials—and provide updates on a new position statement on IHC guidance. We also outline regulatory changes to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988 and College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory director requirements and emphasize the importance of continued legislative advocacy.

Reversal of Reimbursement Denials for IHC Stains

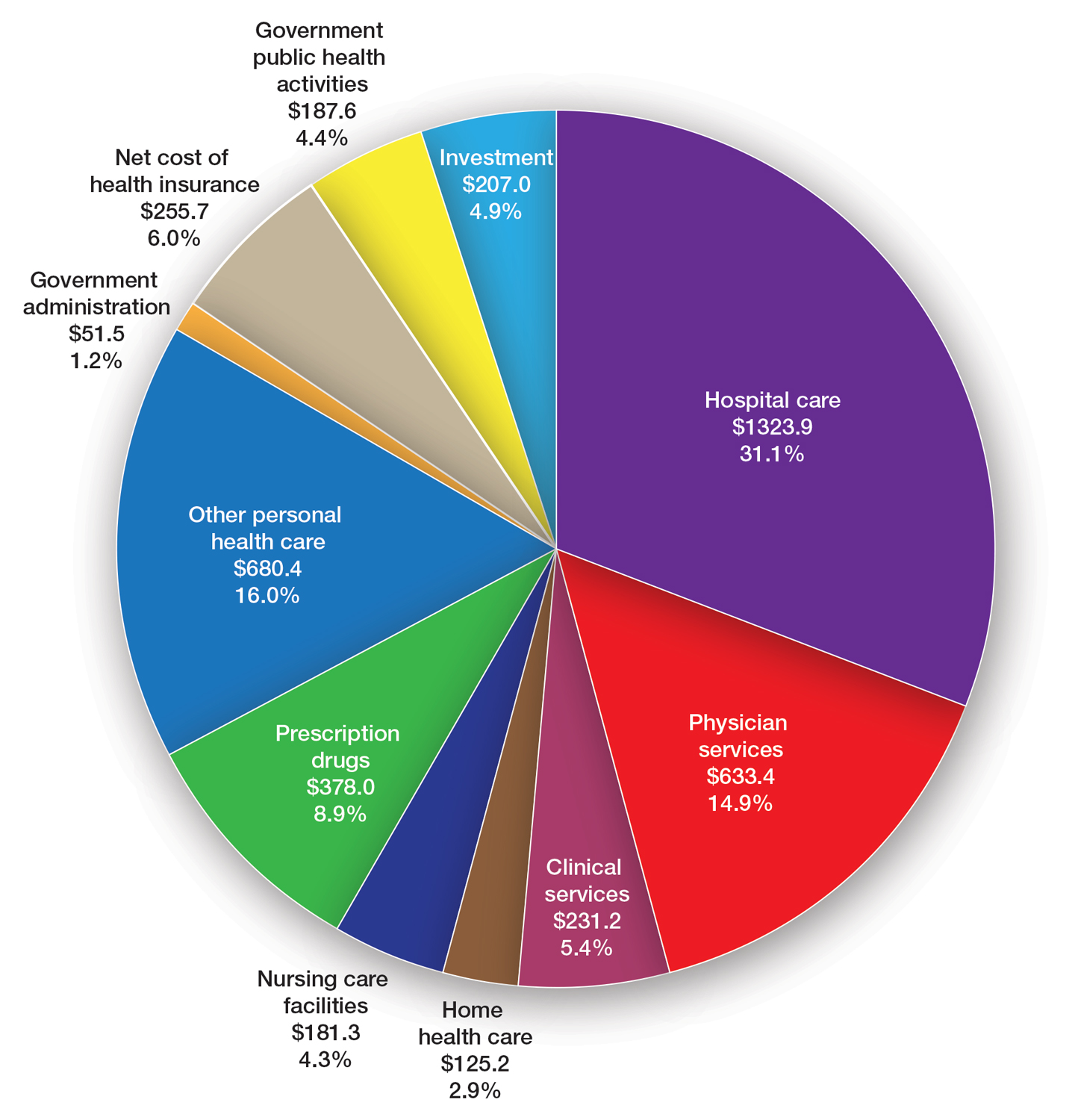

EviCore, a medical benefits management company serving over one-third of insured individuals in the United States, is hired by an extensive network of insurance companies to develop clinical and laboratory guidelines and utilization and payment integrity programs.3 EviCore’s laboratory management guidelines for 2024 denied IHC stains (Current Procedural Terminology codes 88341 and 88342) as not medically necessary when associated with specific International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, skin lesion codes (eTable 1).3-5 These policies caused major disruption to dermatopathology services nationwide, impacting both academic and private laboratories (eTable 2).5 The implementation of such blanket denials interferes with clinical decision-making, compromising diagnostic quality by restricting medically necessary and essential laboratory and pathology services. The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) and CAP leadership formally objected to the policy, citing how these reimbursement denials fail to account for the importance of clinical judgment and diagnostic nuance.6

Thanks to broad advocacy efforts, EviCore updated its guidelines effective January 1, 2025. The skin-related International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were removed from IHC coverage restrictions, with automatic payment reinstated retroactive to March 15, 2024. EviCore also rescinded language denying reimbursement if a diagnosis could be made without the use of IHC stains.7 While this reversal is a notable achievement, ongoing monitoring of emerging trends in claim denials remains crucial. Continued advocacy, proper documentation, and adherence to American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) Appropriate Use Criteria is essential to protecting clinical autonomy.

The AADA’s Dermatopathology Committee developed a new position statement on IHC utilization supporting the advocacy efforts with payers, who recently have tried to implement restrictive limitations.8 Immunohistochemistry is considered a valuable tool for dermatopathology diagnosis, and its utility aids in the confirmation, exclusion, or change in diagnosis.9 By clearly outlining the clinical value of IHC in dermatopathology, this statement reinforces the need to advocate against restrictive payer policies to preserve physician autonomy and promote appropriate, evidence-based use of IHC stains.8

In addition, the ASDP Standards of Practice Committee is working with the Johns Hopkins–Global Appropriateness Measures data-powered analytics platform to develop physician-led IHC benchmarks. The ASDP Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application is a valuable clinical tool for dermatopathologists, general pathologists, dermatologists, and other providers, offering case-based recommendations for test utilization grounded in current evidence.9

Legislative Advocacy: Support for H.R. 879

Physician payment cuts have reached a critical tipping point. Since 2001, physicians have experienced a 33% average reduction in Medicare reimbursement, unadjusted for inflation or rising overhead.10 In January 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposed a further 2.83% cut, despite projecting a 3.5% increase in the Medicare Economic Index.11,12 Dermatologists and other physician groups cannot continue to absorb these reductions, as they have several consequences, including the inability to maintain practices, forcing some physicians out of business, driving health care consolidation, and limiting patient access.

The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act (H.R. 879)13 is bipartisan legislation that seeks to stop the 2.8% Medicare physician payment cut that went into effect in January 2025, provide physicians with an additional 2% inflation-adjusted payment increase for 2025, and help stabilize Medicare reimbursement rates.13,14 As the impact of continued cuts threatens both patient access and practice viability, member engagement is essential to advancing federal physician payment reform. To support sustainable payment reform and protect access to care, visit the AADA Advocacy Action Center online.14

2025 CLIA and CAP Laboratory Director Requirements: What’s Changing?

As of December 28, 2024, updated CLIA regulations took effect for all laboratories performing moderate- or high-complexity testing. These revisions aim to modernize outdated requirements and update regulations to incorporate technological advancements such as automation and artificial intelligence.15 New CLIA standards require laboratory directors with Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathy degrees to be certified in anatomic and/or clinical pathology by the American Board of Pathology or the American Osteopathic Board of Pathology.15 For physicians who do not hold these board-certified qualifications, there are alternative pathways to becoming a laboratory director based on experience and education for physicians licensed to practice in the jurisdiction where the laboratory is located. For high-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 2 years of experience directing or supervising high-complexity testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities. For moderate-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 1 year of experience supervising nonwaived laboratory testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities.16

If the current laboratory director is not board certified in pathology, the new regulation will permit the grandfathering of current laboratory directors if existing laboratory directors have remained continuously employed in their current role since December 28, 2024.16 Therefore, individuals who were already employed in qualifying positions as of December 28, 2024, will be grandfathered in and will not need to meet the new educational requirements if they remain employed without interruption. All individuals qualifying after December 28, 2024, will be required to do so under the new provisions stated earlier.

The CMS updated laboratory personnel requirements, thereby impacting all CLIA-certified laboratories and those seeking CLIA certification. Likewise, laboratories seeking accreditation by the CAP must meet the new laboratory personnel requirements.17 In some cases, CAP requirements are more stringent than the CLIA regulations (CAP accreditation is more stringent in areas of quality control, personnel qualifications, proficiency testing, and in oversight of laboratory developed tests).15-17 If more stringent state or local regulations are in place for personnel qualifications, including requirements for state licensure, they must be followed.

The AADA formed an ad hoc workgroup to address the CLIA laboratory director requirements and is actively engaging CMS to amend these requirements immediately. Formal objections have been submitted, and direct dialogue with CMS leadership is under way in collaboration with the American Board of Dermatology and leading dermatology and pathology societies.

Final Thoughts

Advocacy remains essential to the future of dermatology. From payer policy reversals to laboratory compliance reforms and federal payment advocacy, physicians must remain engaged. Whether it is safeguarding diagnostic autonomy or securing financial sustainability, we must continue to put “skin in the game.”

The US health care system presents major administrative burdens—particularly in coding, billing, and reimbursement—that impact clinical efficiency and patient access. Dermatologists have experienced disproportionate reimbursement declines. A longitudinal review of 20 dermatologic service codes found a 10% average decline in Medicare reimbursement between 2000 and 2020.1 A recent cross-sectional study showed a 4.7% average decline in reimbursement rates from 2007 to 2021 for commonly performed dermatologic procedures, with variation across procedure categories.2 These reductions threaten practice sustainability and highlight the urgent need for comprehensive, long-term payment reform to preserve access to high-quality dermatologic care.

In dermatopathology, policy changes to reimbursement and laboratory oversight directly impact practice operations. Specialty-specific advocacy remains vital in driving policy changes. In this article, we highlight a recent advocacy win—the reversal of immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain denials—and provide updates on a new position statement on IHC guidance. We also outline regulatory changes to the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) of 1988 and College of American Pathologists (CAP) laboratory director requirements and emphasize the importance of continued legislative advocacy.

Reversal of Reimbursement Denials for IHC Stains

EviCore, a medical benefits management company serving over one-third of insured individuals in the United States, is hired by an extensive network of insurance companies to develop clinical and laboratory guidelines and utilization and payment integrity programs.3 EviCore’s laboratory management guidelines for 2024 denied IHC stains (Current Procedural Terminology codes 88341 and 88342) as not medically necessary when associated with specific International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, skin lesion codes (eTable 1).3-5 These policies caused major disruption to dermatopathology services nationwide, impacting both academic and private laboratories (eTable 2).5 The implementation of such blanket denials interferes with clinical decision-making, compromising diagnostic quality by restricting medically necessary and essential laboratory and pathology services. The American Academy of Dermatology Association (AADA) and CAP leadership formally objected to the policy, citing how these reimbursement denials fail to account for the importance of clinical judgment and diagnostic nuance.6

Thanks to broad advocacy efforts, EviCore updated its guidelines effective January 1, 2025. The skin-related International Statistical Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, codes were removed from IHC coverage restrictions, with automatic payment reinstated retroactive to March 15, 2024. EviCore also rescinded language denying reimbursement if a diagnosis could be made without the use of IHC stains.7 While this reversal is a notable achievement, ongoing monitoring of emerging trends in claim denials remains crucial. Continued advocacy, proper documentation, and adherence to American Society of Dermatopathology (ASDP) Appropriate Use Criteria is essential to protecting clinical autonomy.

The AADA’s Dermatopathology Committee developed a new position statement on IHC utilization supporting the advocacy efforts with payers, who recently have tried to implement restrictive limitations.8 Immunohistochemistry is considered a valuable tool for dermatopathology diagnosis, and its utility aids in the confirmation, exclusion, or change in diagnosis.9 By clearly outlining the clinical value of IHC in dermatopathology, this statement reinforces the need to advocate against restrictive payer policies to preserve physician autonomy and promote appropriate, evidence-based use of IHC stains.8

In addition, the ASDP Standards of Practice Committee is working with the Johns Hopkins–Global Appropriateness Measures data-powered analytics platform to develop physician-led IHC benchmarks. The ASDP Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application is a valuable clinical tool for dermatopathologists, general pathologists, dermatologists, and other providers, offering case-based recommendations for test utilization grounded in current evidence.9

Legislative Advocacy: Support for H.R. 879

Physician payment cuts have reached a critical tipping point. Since 2001, physicians have experienced a 33% average reduction in Medicare reimbursement, unadjusted for inflation or rising overhead.10 In January 2025, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) imposed a further 2.83% cut, despite projecting a 3.5% increase in the Medicare Economic Index.11,12 Dermatologists and other physician groups cannot continue to absorb these reductions, as they have several consequences, including the inability to maintain practices, forcing some physicians out of business, driving health care consolidation, and limiting patient access.

The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act (H.R. 879)13 is bipartisan legislation that seeks to stop the 2.8% Medicare physician payment cut that went into effect in January 2025, provide physicians with an additional 2% inflation-adjusted payment increase for 2025, and help stabilize Medicare reimbursement rates.13,14 As the impact of continued cuts threatens both patient access and practice viability, member engagement is essential to advancing federal physician payment reform. To support sustainable payment reform and protect access to care, visit the AADA Advocacy Action Center online.14

2025 CLIA and CAP Laboratory Director Requirements: What’s Changing?

As of December 28, 2024, updated CLIA regulations took effect for all laboratories performing moderate- or high-complexity testing. These revisions aim to modernize outdated requirements and update regulations to incorporate technological advancements such as automation and artificial intelligence.15 New CLIA standards require laboratory directors with Doctor of Medicine or Doctor of Osteopathy degrees to be certified in anatomic and/or clinical pathology by the American Board of Pathology or the American Osteopathic Board of Pathology.15 For physicians who do not hold these board-certified qualifications, there are alternative pathways to becoming a laboratory director based on experience and education for physicians licensed to practice in the jurisdiction where the laboratory is located. For high-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 2 years of experience directing or supervising high-complexity testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities. For moderate-complexity laboratories, individuals need at least 1 year of experience supervising nonwaived laboratory testing and at least 20 continuing education credit hours in laboratory practice that cover director responsibilities.16

If the current laboratory director is not board certified in pathology, the new regulation will permit the grandfathering of current laboratory directors if existing laboratory directors have remained continuously employed in their current role since December 28, 2024.16 Therefore, individuals who were already employed in qualifying positions as of December 28, 2024, will be grandfathered in and will not need to meet the new educational requirements if they remain employed without interruption. All individuals qualifying after December 28, 2024, will be required to do so under the new provisions stated earlier.

The CMS updated laboratory personnel requirements, thereby impacting all CLIA-certified laboratories and those seeking CLIA certification. Likewise, laboratories seeking accreditation by the CAP must meet the new laboratory personnel requirements.17 In some cases, CAP requirements are more stringent than the CLIA regulations (CAP accreditation is more stringent in areas of quality control, personnel qualifications, proficiency testing, and in oversight of laboratory developed tests).15-17 If more stringent state or local regulations are in place for personnel qualifications, including requirements for state licensure, they must be followed.

The AADA formed an ad hoc workgroup to address the CLIA laboratory director requirements and is actively engaging CMS to amend these requirements immediately. Formal objections have been submitted, and direct dialogue with CMS leadership is under way in collaboration with the American Board of Dermatology and leading dermatology and pathology societies.

Final Thoughts

Advocacy remains essential to the future of dermatology. From payer policy reversals to laboratory compliance reforms and federal payment advocacy, physicians must remain engaged. Whether it is safeguarding diagnostic autonomy or securing financial sustainability, we must continue to put “skin in the game.”

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358.

- Miller TC, Rucker P, Armstrong D. “Not medically necessary”: inside the company helping America’s biggest health insurers deny coverage for care. ProPublica. October 23, 2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/evicore-health-insurance-denials-cigna-unitedhealthcare-aetna-prior-authorizations

- EviCore healthcare. Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/MOL.CS_.104.A_Immunohistochemistry%20%28IHC%29_V2.0.2024_eff11.01.2024_pub12.31.2024.pdf

- EviCore. Laboratory management. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/provider/clinical-guidelines-details?solution=laboratory%20management

- Saad AJ. College of American Pathologists. December 12, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents /Wellmark-Letter- https://documents.cap.org/documents/wellmarkcap-letter2023.pdf

- EviCore healthcare. Clinical Guidelines: Lab Management Program. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/Cigna_LabMgmt_V1.0.2025_eff01.01.2025_pub08.22.2024_0.pdf

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on immunohistochemistry utilization. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://server.aad.org/forms/policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Immunohistochemistry%20Utilization.pdf

- Naert KA, Trotter MJ. Utilization and utility of immunohistochemistry in dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:74-77.

- American Medical Association. Medicare physician payment continues to fall further behind practice cost inflation. Accessed April 23, 2025. https:// www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2025-medicare-updates-inflation-chart.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule

- American Medical Association. The Medicare Economic Index. Accessed April 23 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-basics-medicare-economic-index.pdf

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act, HR 879, 119th Cong (2025). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/879

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) fees; histocompatibility, personnel, and alternative sanctions for certificate of waiver laboratories. Fed Regist. 2023;88:89976-90044.

- College of American Pathologists. CAP accreditation checklists – 2024 edition. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents/2024-Checklist-Summary.pdf?_gl=1*1b4rei9*_ga*NDc0NjYwNjM5LjE3NDQ3NTI4NjA.*_ga_97ZFJSQQ0X*MTc0NDc2OTc3My40LjEuMTc0NDc2OTgyOC4wLjAuMA

- Bennett SA, Conn CM, Gill HE, et al. Regulatory requirements for laboratory developed tests in the United States. J Immunol Methods. 2025;537:113813.

- Pollock JR, Chen JY, Dorius DA, et al. Decreasing physician Medicare reimbursement for dermatology services. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1154-1156.

- Mazmudar RS, Sheth A, Tripathi R, et al. Inflation-adjusted trends in Medicare reimbursement for common dermatologic procedures, 2007-2021. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:1355-1358.

- Miller TC, Rucker P, Armstrong D. “Not medically necessary”: inside the company helping America’s biggest health insurers deny coverage for care. ProPublica. October 23, 2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.propublica.org/article/evicore-health-insurance-denials-cigna-unitedhealthcare-aetna-prior-authorizations

- EviCore healthcare. Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2024. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/MOL.CS_.104.A_Immunohistochemistry%20%28IHC%29_V2.0.2024_eff11.01.2024_pub12.31.2024.pdf

- EviCore. Laboratory management. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/provider/clinical-guidelines-details?solution=laboratory%20management

- Saad AJ. College of American Pathologists. December 12, 2023. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents /Wellmark-Letter- https://documents.cap.org/documents/wellmarkcap-letter2023.pdf

- EviCore healthcare. Clinical Guidelines: Lab Management Program. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.evicore.com/sites/default/files/clinical-guidelines/2024-08/Cigna_LabMgmt_V1.0.2025_eff01.01.2025_pub08.22.2024_0.pdf

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. Position statement on immunohistochemistry utilization. Accessed May 9, 2024. https://server.aad.org/forms/policies/Uploads/PS/PS-Immunohistochemistry%20Utilization.pdf

- Naert KA, Trotter MJ. Utilization and utility of immunohistochemistry in dermatopathology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:74-77.

- American Medical Association. Medicare physician payment continues to fall further behind practice cost inflation. Accessed April 23, 2025. https:// www.ama-assn.org/system/files/2025-medicare-updates-inflation-chart.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule final rule. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rule

- American Medical Association. The Medicare Economic Index. Accessed April 23 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/medicare-basics-medicare-economic-index.pdf

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act, HR 879, 119th Cong (2025). Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.congress.gov/bill/119th-congress/house-bill/879

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Department of Health and Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) fees; histocompatibility, personnel, and alternative sanctions for certificate of waiver laboratories. Fed Regist. 2023;88:89976-90044.

- College of American Pathologists. CAP accreditation checklists – 2024 edition. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://documents.cap.org/documents/2024-Checklist-Summary.pdf?_gl=1*1b4rei9*_ga*NDc0NjYwNjM5LjE3NDQ3NTI4NjA.*_ga_97ZFJSQQ0X*MTc0NDc2OTc3My40LjEuMTc0NDc2OTgyOC4wLjAuMA

- Bennett SA, Conn CM, Gill HE, et al. Regulatory requirements for laboratory developed tests in the United States. J Immunol Methods. 2025;537:113813.

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

Advocacy and Compliance Issues Impacting Dermatology in 2025

PRACTICE POINTS

- Recent advocacy efforts have led to the reversal of widespread insurer denials for immunohistochemistry stains; however, continued vigilance is necessary, as restrictive coverage policies may re-emerge.

- Laboratory directors must comply with updated Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 and College of American Pathologists personnel requirements effective December 28, 2024, including stricter board certification and 2 years of laboratory training or experience and 20 hours of continuing education requirements.

- The American Society of Dermatopathology Appropriate Use Criteria mobile application provides physicians with evidence-based guidance for test selection in dermatopathology.

Legislative, Practice Management, and Coding Updates for 2025

Legislative, Practice Management, and Coding Updates for 2025

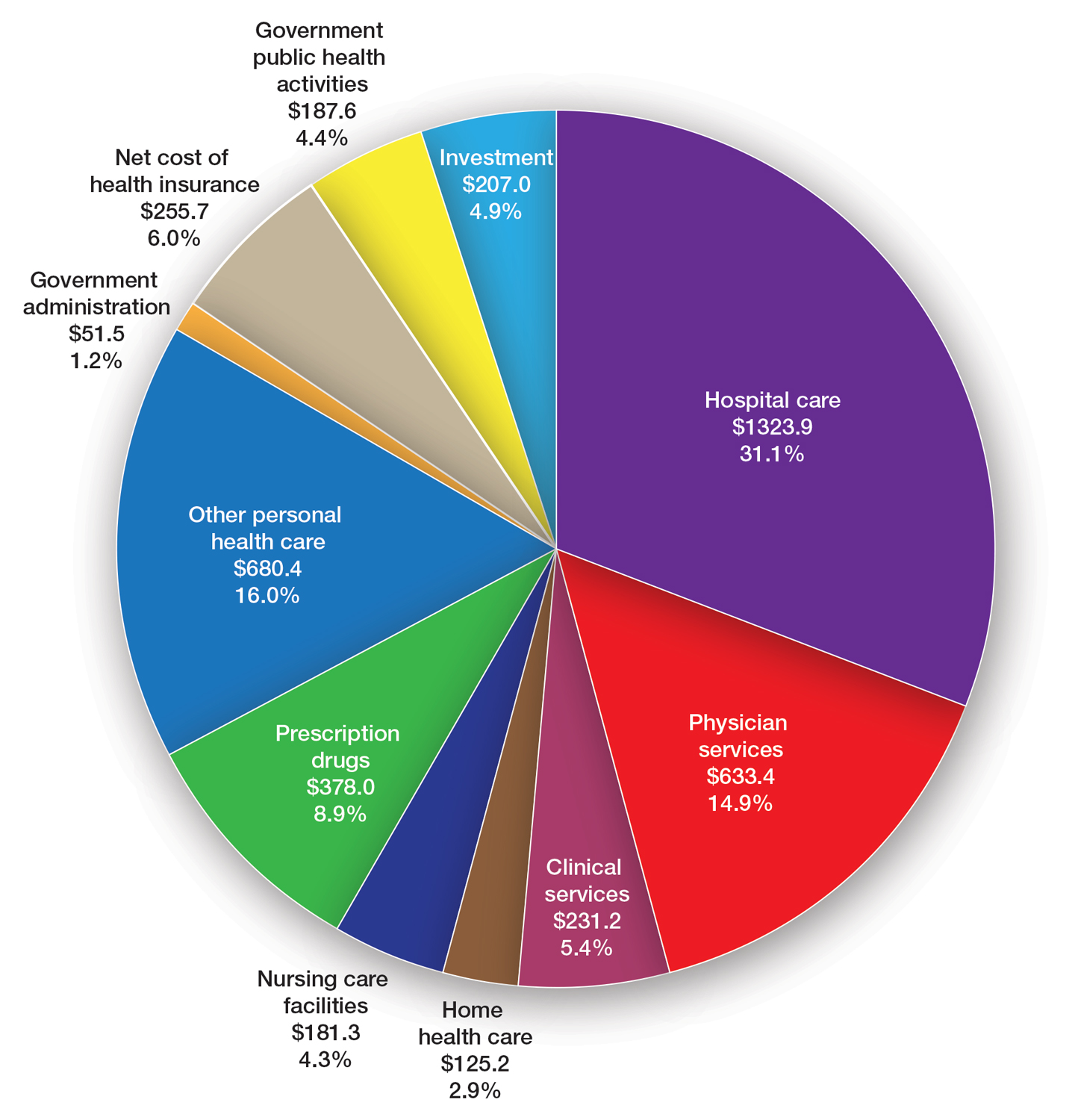

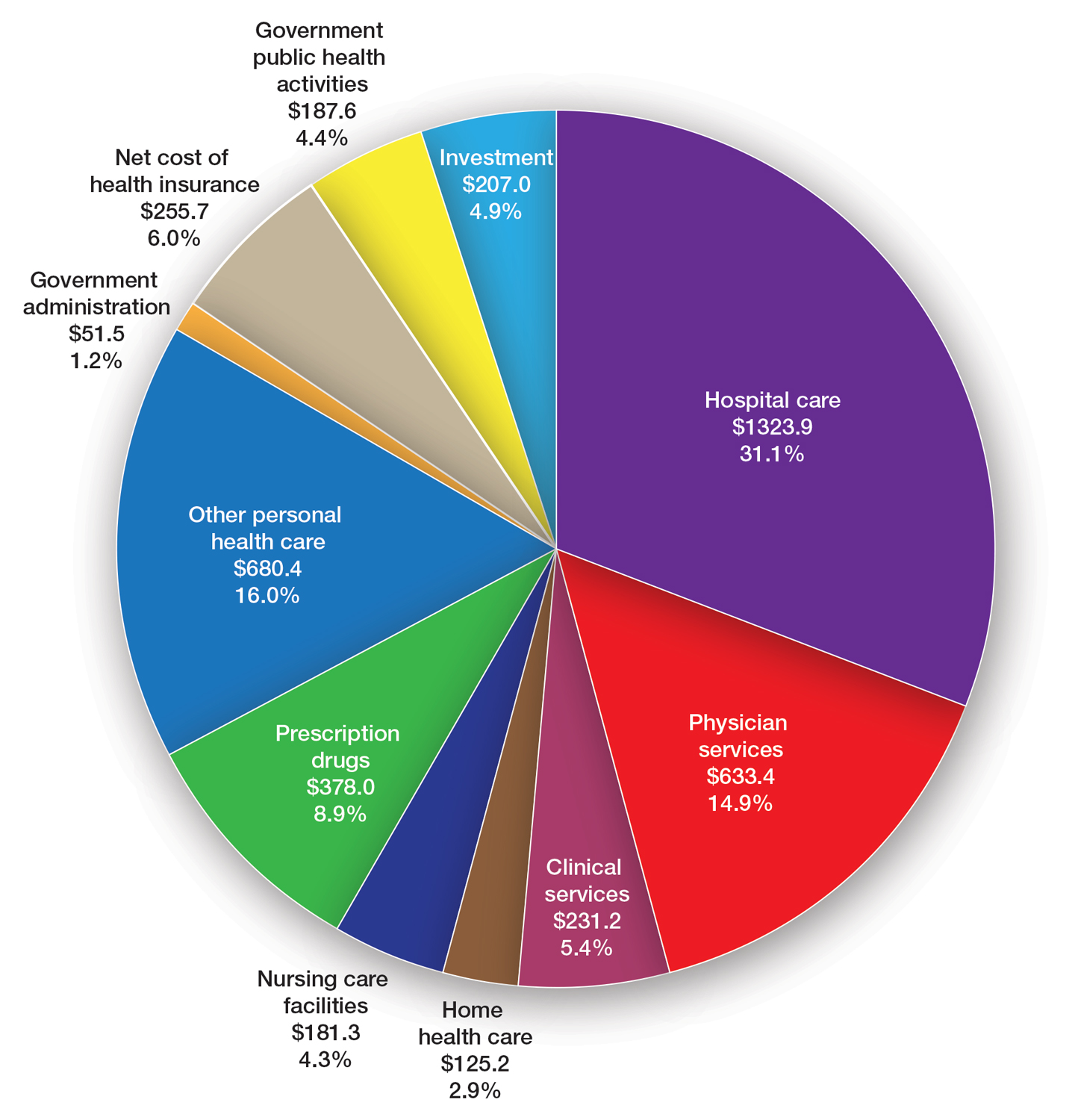

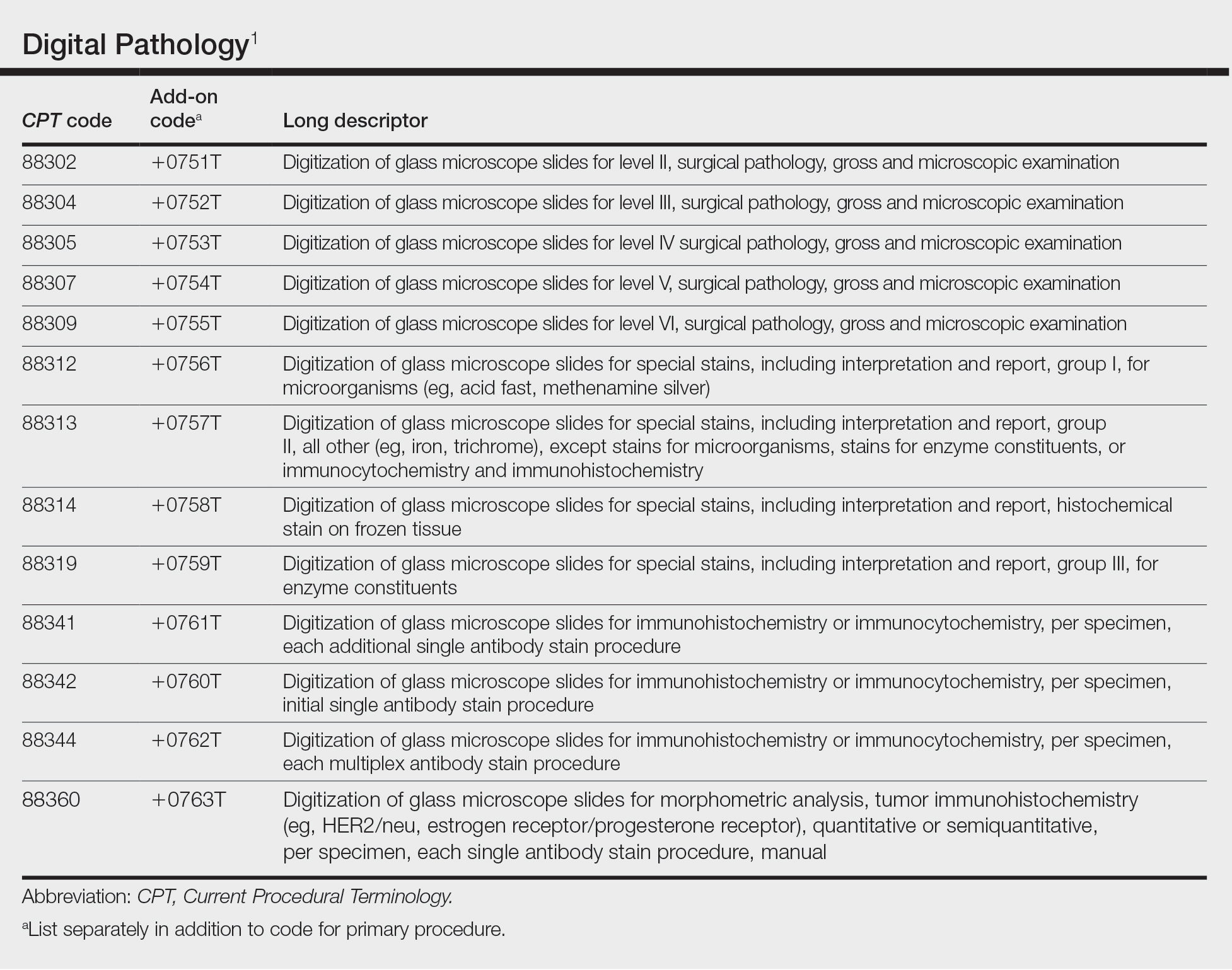

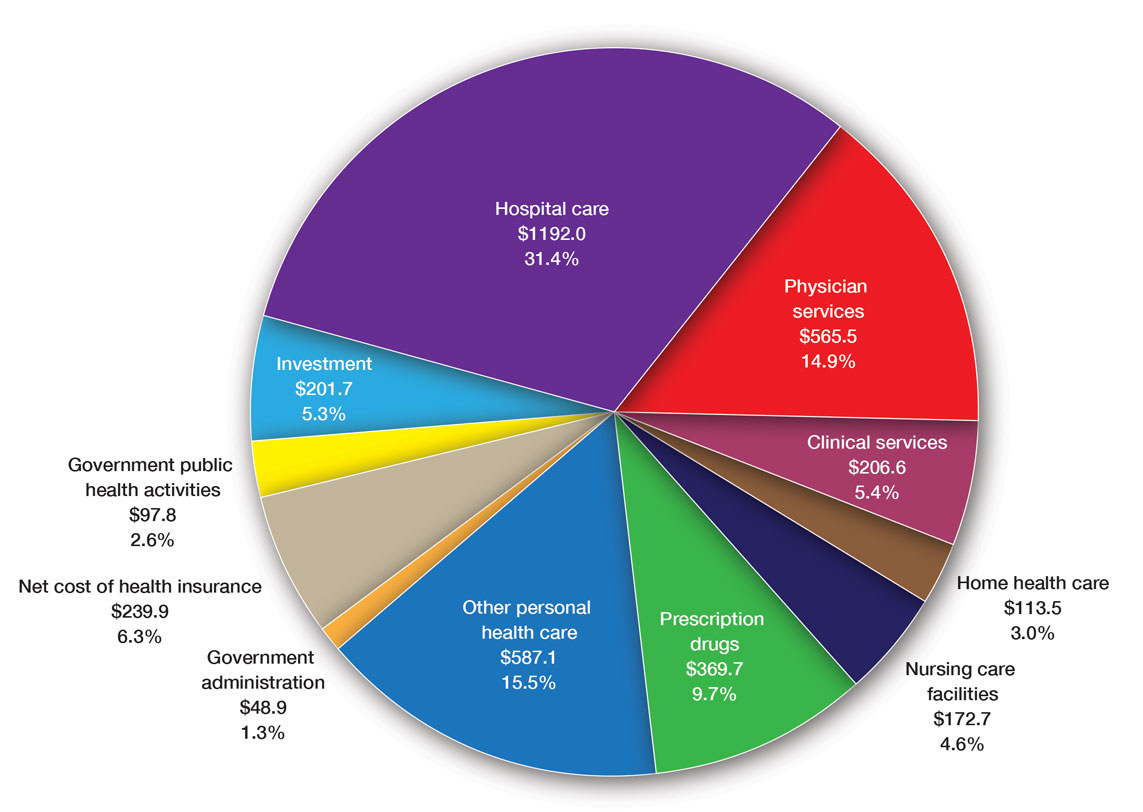

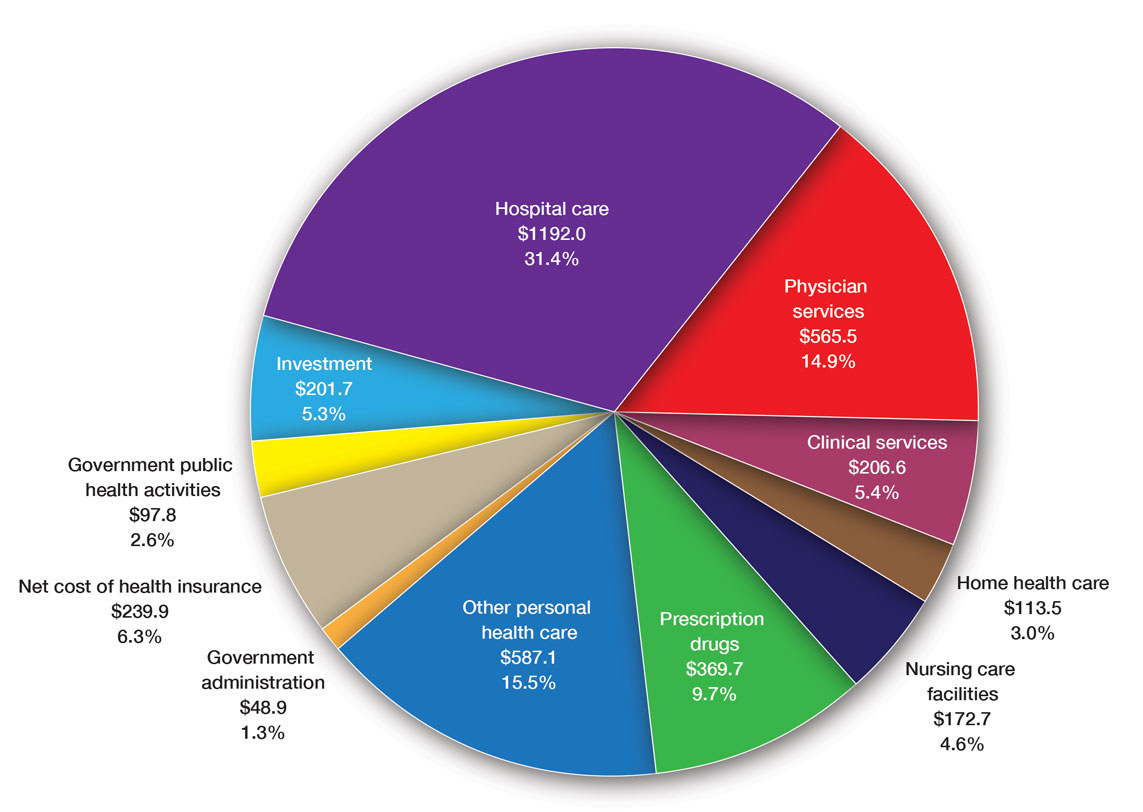

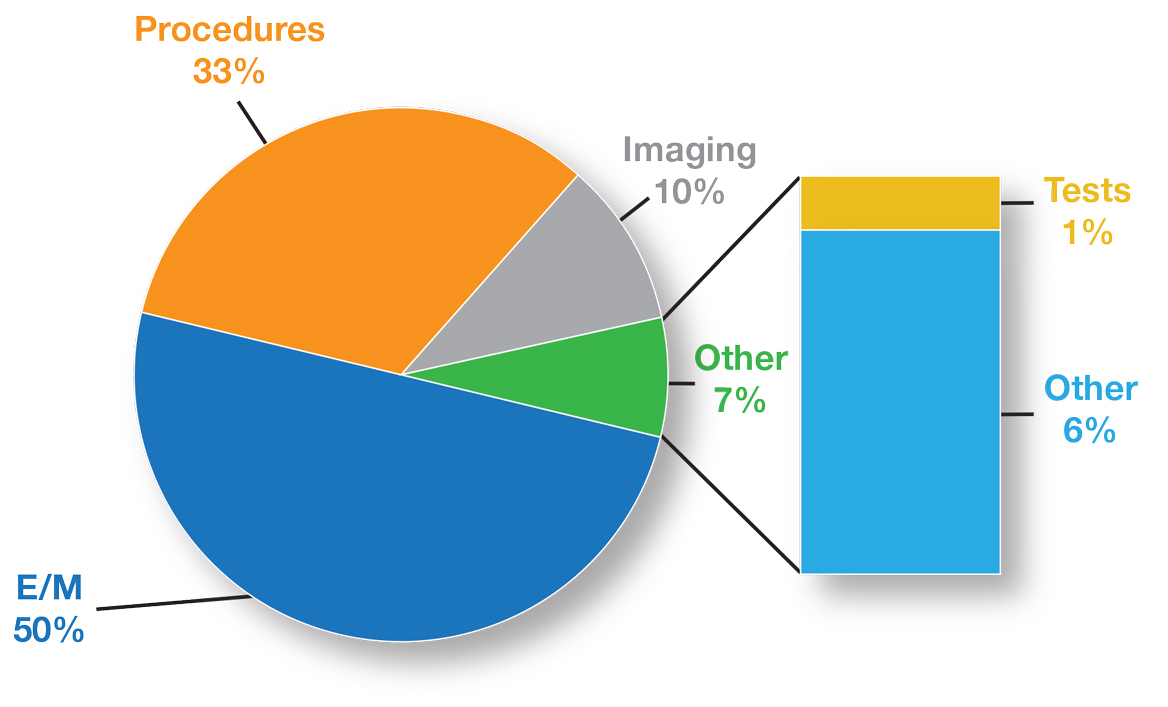

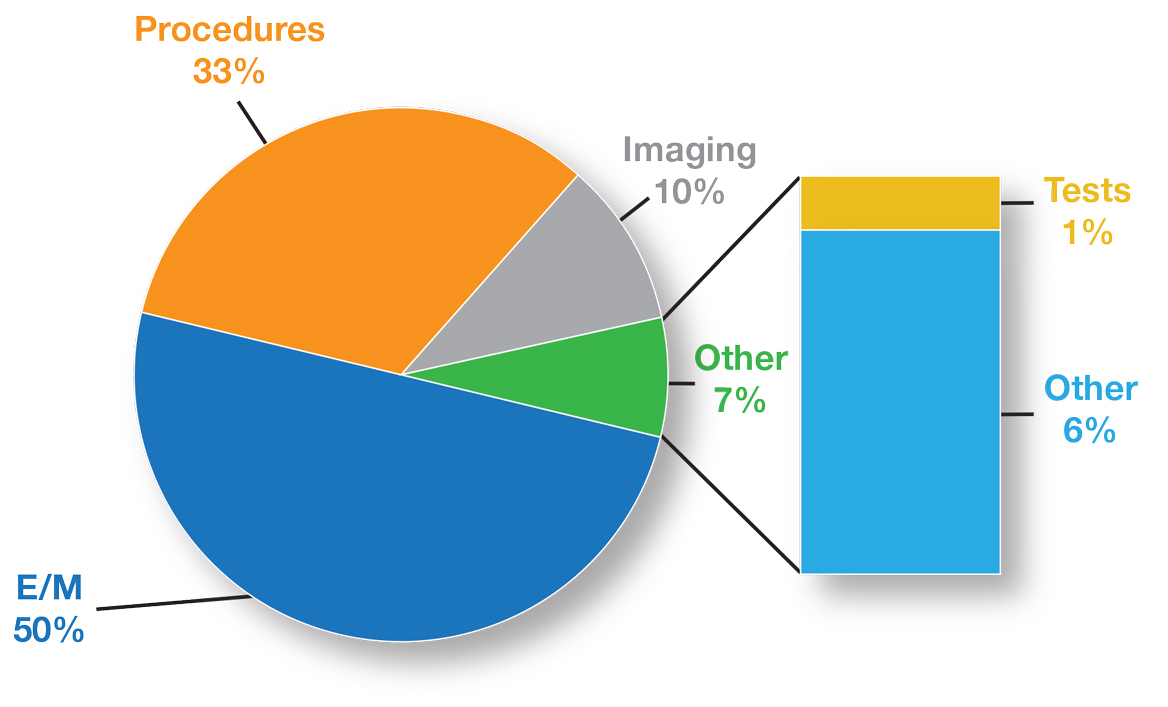

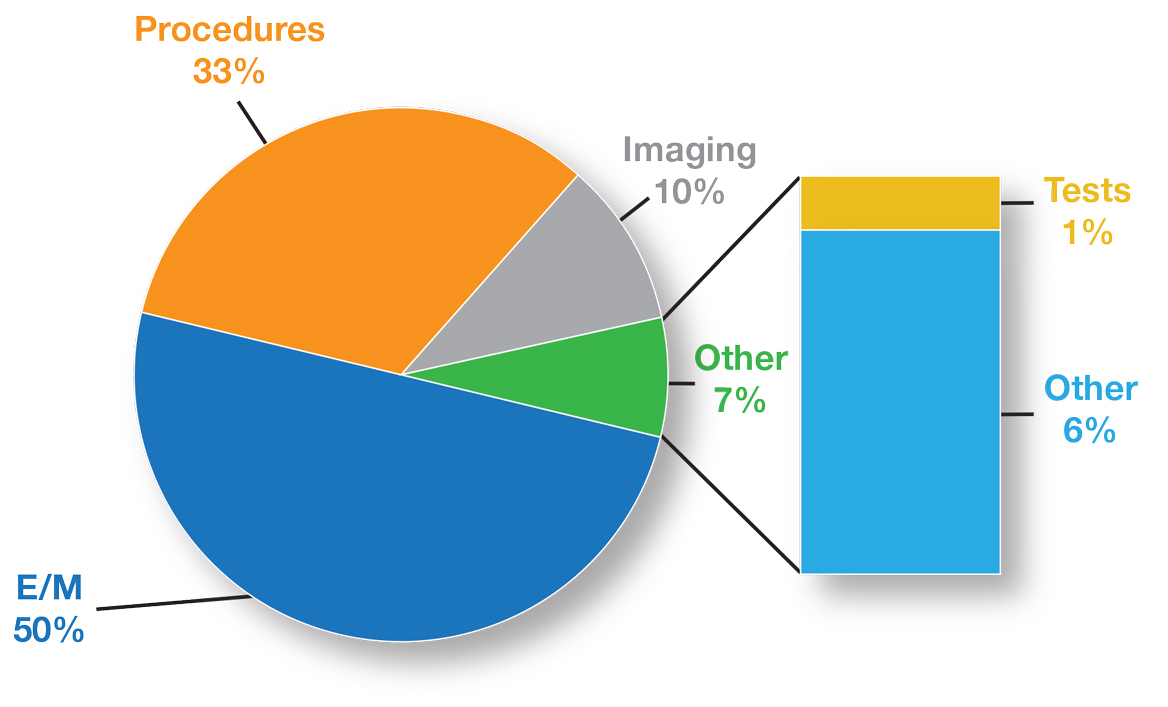

Health care costs continue to increase in 2025 while physician reimbursement continues to decrease. Of the $4.5 trillion spent on health care in 2022, only 20% was spent on physician and clinical services.1 Since 2001, practice expense has risen 47%, while the Consumer Price Index has risen 73%; adjusted for inflation, physician reimbursement has declined 30% since 2001.2

The formula for Medicare payments for physician services, calculated by multiplying the conversion factor (CF) by the relative value unit (RVU), was developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 1992. The combination of the physician’s work, the practice’s expense, and the cost of professional liability insurance make up RVUs, which are aligned by geographic index adjustments.3 The 2024 CF was $32.75, compared to $32.00 in 1992. The proposed 2025 CF is $32.35, which is a 10% decrease since 2019 and a 2.8% decrease relative to the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). The 2.8% cut is due to expiration of the 2.93% temporary payment increase for services provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2024 and the supplemental relief provided from March 9, 2024, to December 31, 2024.4 If the CF had increased with inflation, it would have been $71.15 in 2024.4

Declining reimbursement rates for physician services undermine the ability of physician practices to keep their doors open in the face of increased operating costs. Faced with the widening gap between what Medicare pays for physician services and the cost of delivering value-based, quality care, physicians are urging Congress to pass a reform package to permanently strengthen Medicare.

Herein, an overview of key coding updates and changes, telehealth flexibilities, and a new dermatologyfocused Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways is provided.

Update on the Medicare Economic Index Postponement

Developed in 1975, the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) is a measure of practice cost inflation. It is a yearly calculation that estimates the annual changes in physicians’ operating costs to determine appropriate Medicare physician payment updates.5 The MEI is composed of physician practice costs (eg, staff salaries, office space, malpractice insurance) and physician compensation (direct earnings by the physician). Both are used to calculate adjustments to Medicare physician payments to account for inflationary increases in health care costs. The MEI for 2025 is projected to increase by 3.5%, while physician payment continues to dwindle.5 This disparity between rising costs and declining physician payments will impact patient access to medical care. Physicians may choose to stop accepting Medicare and other health insurance, face the possibility of closing or selling their practices, or even decide to leave the profession.

The CMS has continued to delay implementation of the 2017 MEI cost weights (which currently are based on 2006 data5) for RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2025 pending completion of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Practice Information Survey.6 The AMA contracted with an independent research company to conduct the survey, which will be used to update the MEI. Survey data will be shared with the CMS in early 2025.6

Future of Telehealth is Uncertain

On January 1, 2025, many telehealth flexibilities were set to expire; however, Congress passed an extension of the current telehealth policy flexibilities that have been in place since the COVID-19 pandemic through March 31, 2025.7 The CMS recognizes concerns about maintaining access to Medicare telehealth services once the statutory flexibilities expire; however, it maintains that it has limited statutory authority to extend these Medicare telehealth flexibilities.8 There will be originating site requirements and geographic location restrictions. Clinicians working in a federally qualified health center or a rural health clinic would not be affected.8

The CMS rejected adoption of 16 of 17 new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (98000–98016) for telemedicine evaluation and management (E/M) services, rendering them nonreimbursable.8 Physicians should continue to use the standard E/M codes 99202 through 99215 for telehealth visits. The CMS only approved code 99016, which will replace Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2012, for brief virtual check-in encounters. The CMS specified that CPT codes 99441 through 99443, which describe telephone E/M services, have been removed and are no longer valid for billing. Asynchronous communication (eg, store-and-forward technology via an electronic health record portal) will continue to be reported using the online digital E/M service codes 99421, 99422, and 99423.8

Practitioners can use their enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from home.8 Teaching physicians will continue to be allowed to have a virtual presence for purposes of billing for services involving residents in all teaching settings, but only when the service is furnished remotely (ie, the patient, resident, and teaching physician all are in separate locations). The use of real-time audio and video technology for direct supervision has been extended through December 31, 2025, allowing practitioners to be immediately available virtually. The CMS also plans to permanently allow virtual supervision for lower-risk services that typically do not require the billing practitioner’s physical presence or extensive direction (eg, diagnostic tests, behavioral health, dermatology, therapy).8

It is essential to verify the reimbursement policies and billing guidelines of individual payers, as some may adopt policies that differ from the AMA and CMS guidelines.

When to Use Modifiers -59 and -76

Modifiers -59 and -76 are used when billing for multiple procedures on the same day and can be confused. These modifiers help clarify situations in which procedures might appear redundant or improperly coded, reducing the risk for claim denials and ensuring compliance with coding guidelines. Use modifier -59 when a procedure or service is distinct or separate from other services performed on the same day (eg, cryosurgery of 4 actinic keratoses and a tangential biopsy of a nevus). Use modifier -76 when a physician performs the exact same procedure multiple times on the same patient on the same day (eg, removing 2 nevi on the face with the same excision code or performing multiple biopsies on different areas on the skin).9

What Are the Medical Team Conference CPT Codes?

Dermatologists frequently manage complex medical and surgical cases and actively participate in tumor boards and multidisciplinary teams conferences. It is essential to be familiar with the relevant CPT codes that can be used in these scenarios: CPT code 99366 can be used when the medical team conference occurs face-to-face with the patient present, and CPT code 99367 can be used for a medical team conference with an interdisciplinary group of health care professionals from different specialties, each of whom provides direct care to the patient.10 For CPT code 99367, the patient and/or family are not present during the meeting, which lasts a minimum of 30 minutes or more and requires participation by a physician. Current Procedural Terminology code 99368 can be used for participation in the medical team conference by a nonphysician qualified health care professional. The reporting participants need to document their participation in the medical team conference as well as their contributed information that explains the case and subsequent treatment recommendations.10

No more than 1 individual from the same specialty may report CPT codes 99366 through 99368 at the same encounter.10 Codes 99366 through 99368 should not be reported when participation in the medical team conference is part of a facility or contractually provided by the facility such as group therapy.10 The medical team conference starts at the beginning of the review of an individual patient and ends at the conclusion of the review for coding purposes. Time related to record-keeping or report generation does not need to be reported. The reporting participant needs to be present for the entire conference. The time reported is not limited to the time that the participant is communicating with other team members or the patient and/or their family/ caregiver(s). Time reported for medical team conferences may not be used in the determination for other services, such as care plan oversight (99374-99380), prolonged services (99358, 99359), psychotherapy, or any E/M service. When the patient is present for any part of the duration of the team conference, nonphysician qualified health care professionals (eg, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, dietitians) report the medical team conference face-to-face with code 99366.10

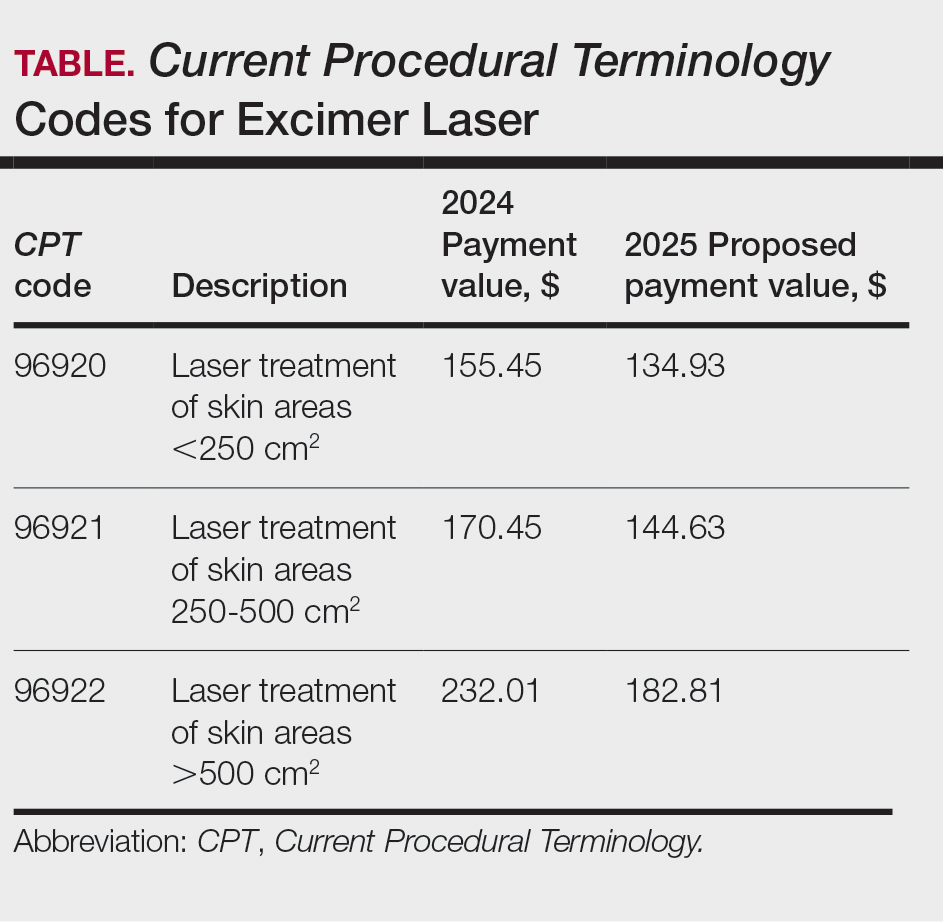

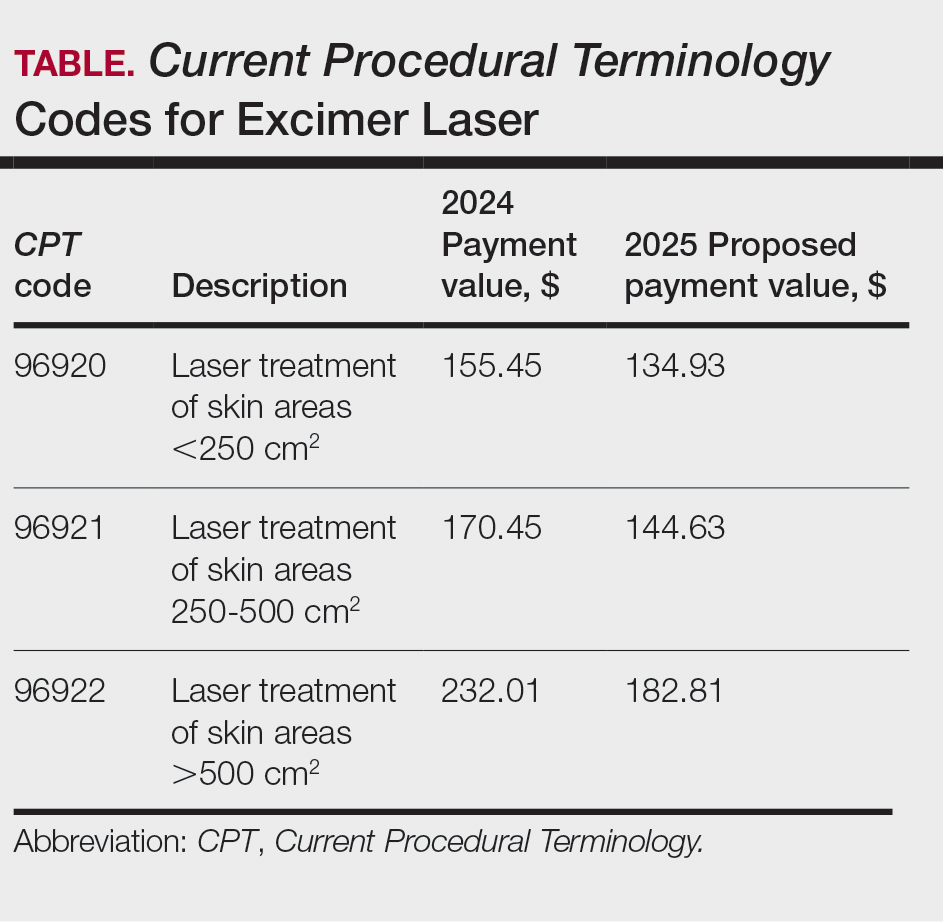

Update on Excimer Laser CPT Codes

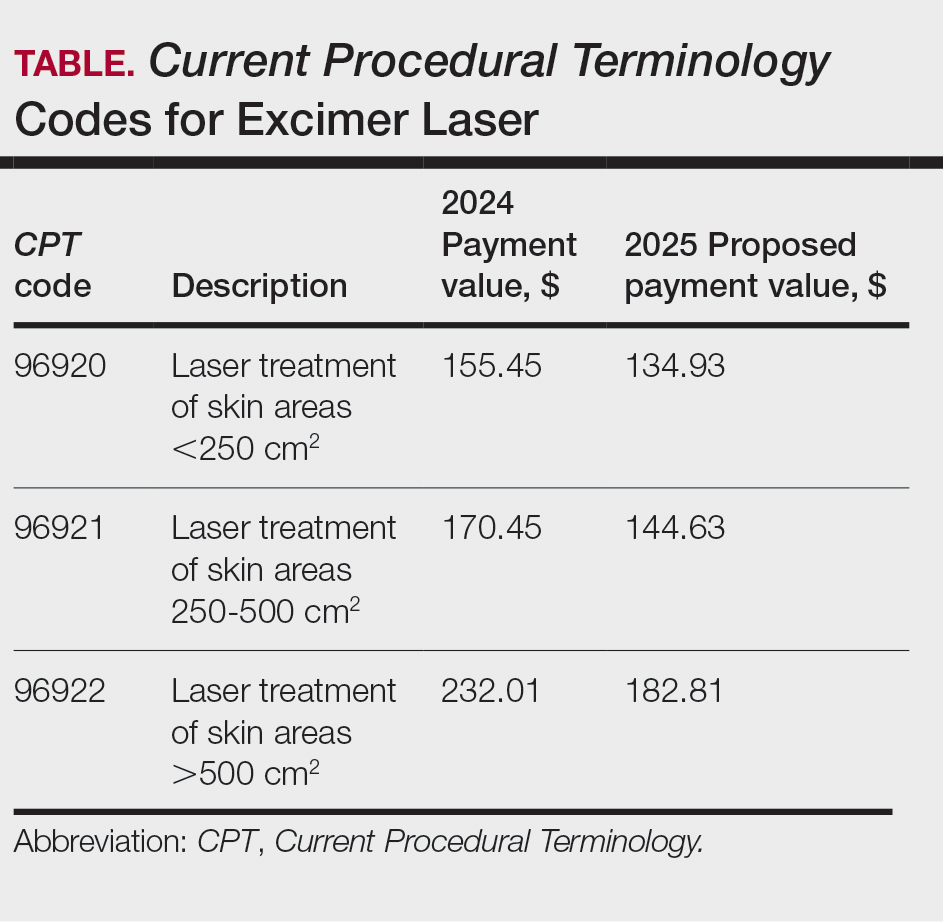

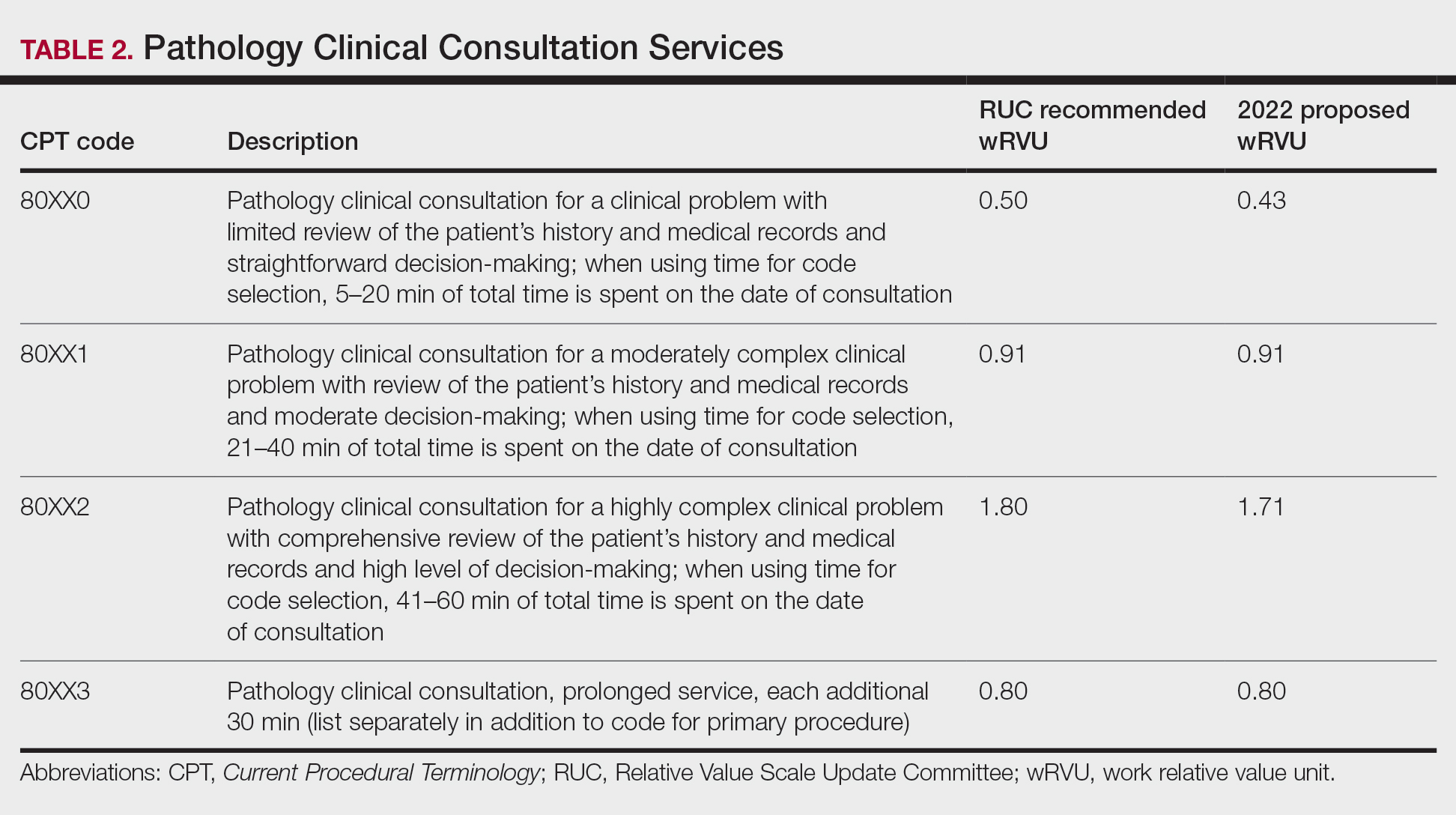

The CMS rejected values recommended for CPT codes (96920-96922) by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, proposing lower work RVUs of 0.83, 0.90, and 1.15, respectively (Table).2,11 The CPT panel did not recognize the strength of the literature supporting the expanded use of the codes for conditions other than psoriasis. Report the use of excimer laser for treatment of vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata using CPT code 96999 (unlisted special dermatological service or procedure).11

Update on the New G2211 Code

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2211 is an add-on complexity code that can be reported with all outpatient E/M visits to better account for additional resources associated with primary care or similarly ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single serious condition or complex condition.12 It can be billed if the physician is serving as the continuing focal point for all the patient's health care service needs, acting as the central point of contact for the patient’s ongoing medical care, and managing all aspects of their health needs over time. It is not restricted based on specialty, but it is determined based on the nature of the physician-patient relationship.12

Code G2211 should not be used for the following scenarios: (1) care provided by a clinician with a discrete, routine, or time-limited relationship with the patient, such as a routine skin examination or an acute allergic contact dermatitis; (2) conditions in which comorbidities are not present or addressed; (3) when the billing clinician has not assumed responsibility for ongoing medical care with consistency and continuity over time; and (4) visits billed with modifier -25.12 In the 2025 MPFS, the CMS is proposing to allow payment of G2211 when the code is reported by the same practitioner on the same day as an annual wellness visit, vaccine administration, or any Medicare Part B preventive service furnished in the office or outpatient setting (ie, creating a limited exception to the prohibition of using this code with modifier -25).2

Documentation in the medical record must support reporting code G2211 and indicate a medically reasonable and necessary reason for the additional RVUs (0.33 and additional payment of $16.05).12

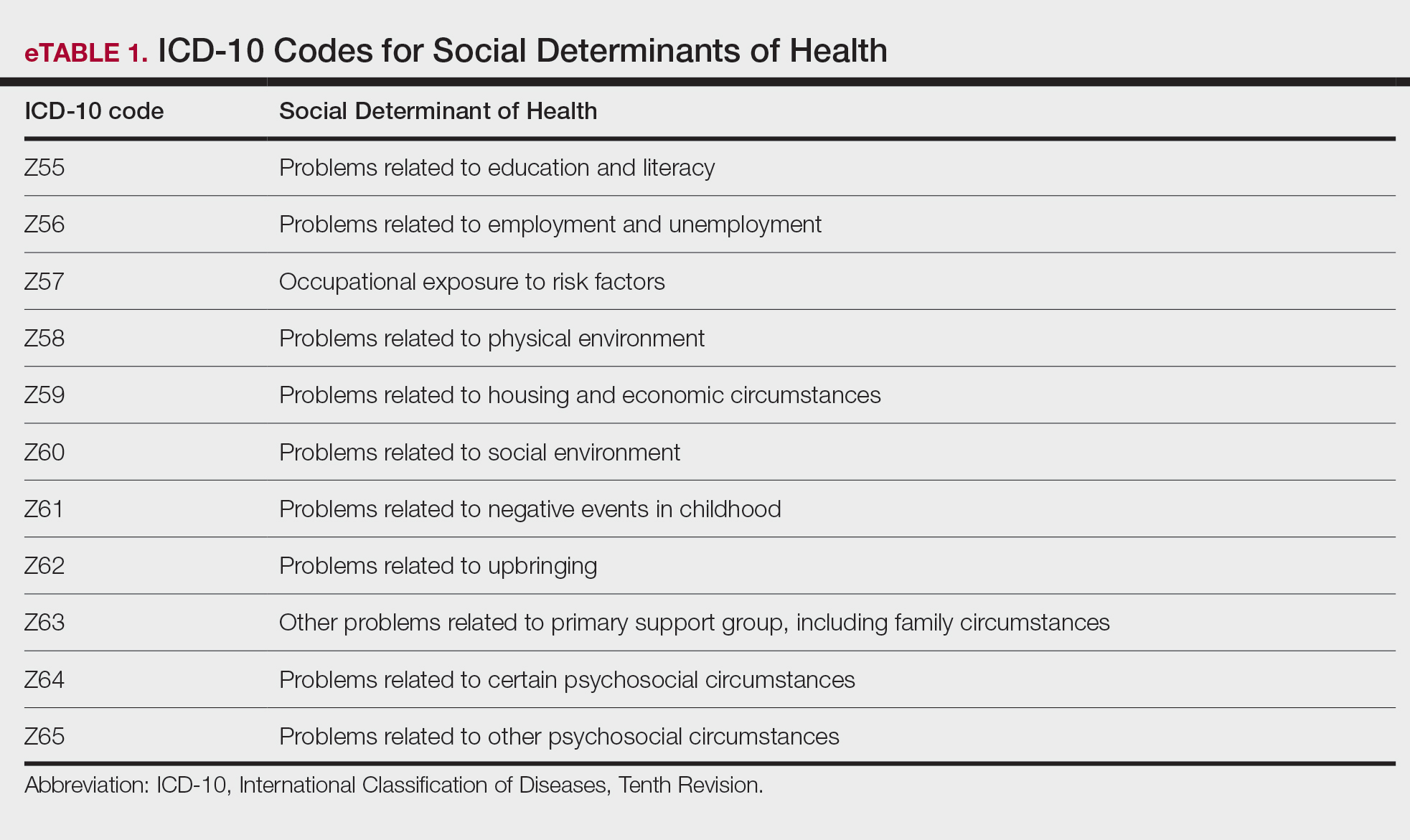

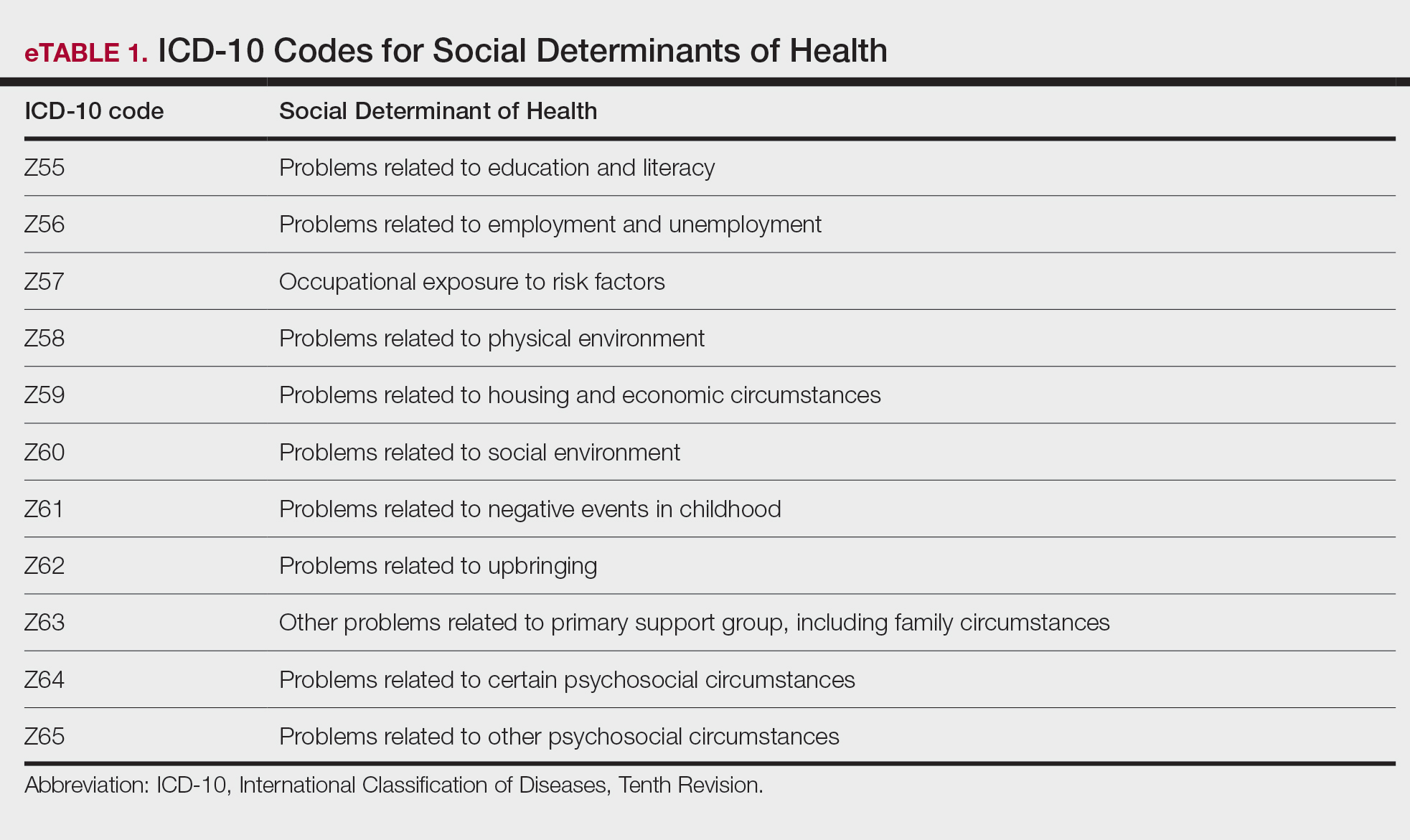

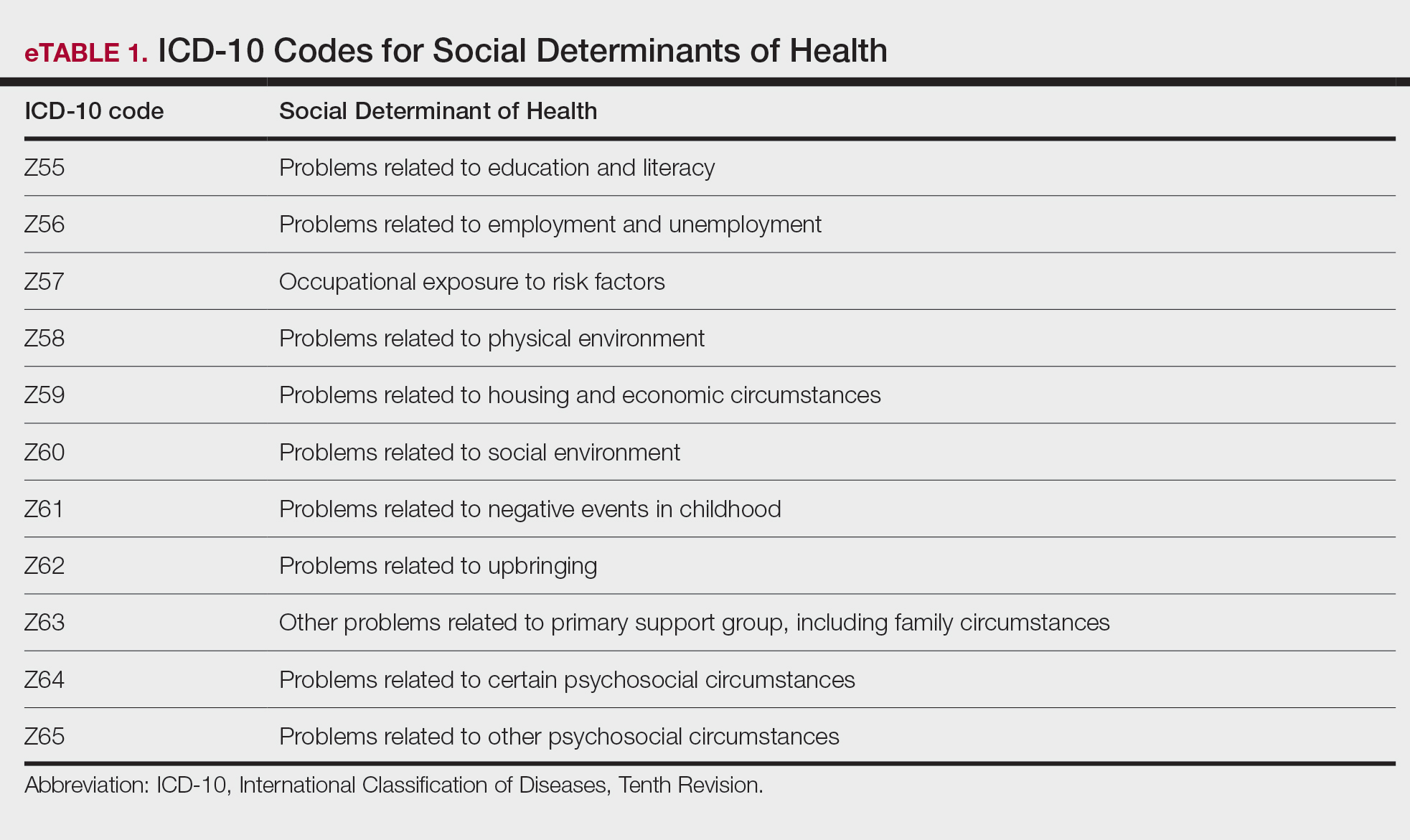

Underutilization of Z Codes for Social Determinants of Health

Barriers to documentation of social determinants of health (SDOH)–related International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Z codes (Z55-Z66)(eTable 1), include lack of clarity on who can document patients’ social needs, lack of systems and processes for documenting and coding SDOH, unfamiliarity with these Z codes, and a low prioritization of collecting these data.13 Documentation of a SDOH-related Z code relevant to a patient encounter is considered moderate risk and can have a major impact on a patient’s overall health, unmet social needs, and outcomes.13 If the other 2 medical decision-making elements (ie, number and complexity of problems addressed along with amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed) for the E/M visit also are moderate, then the encounter can be coded as level 4.13

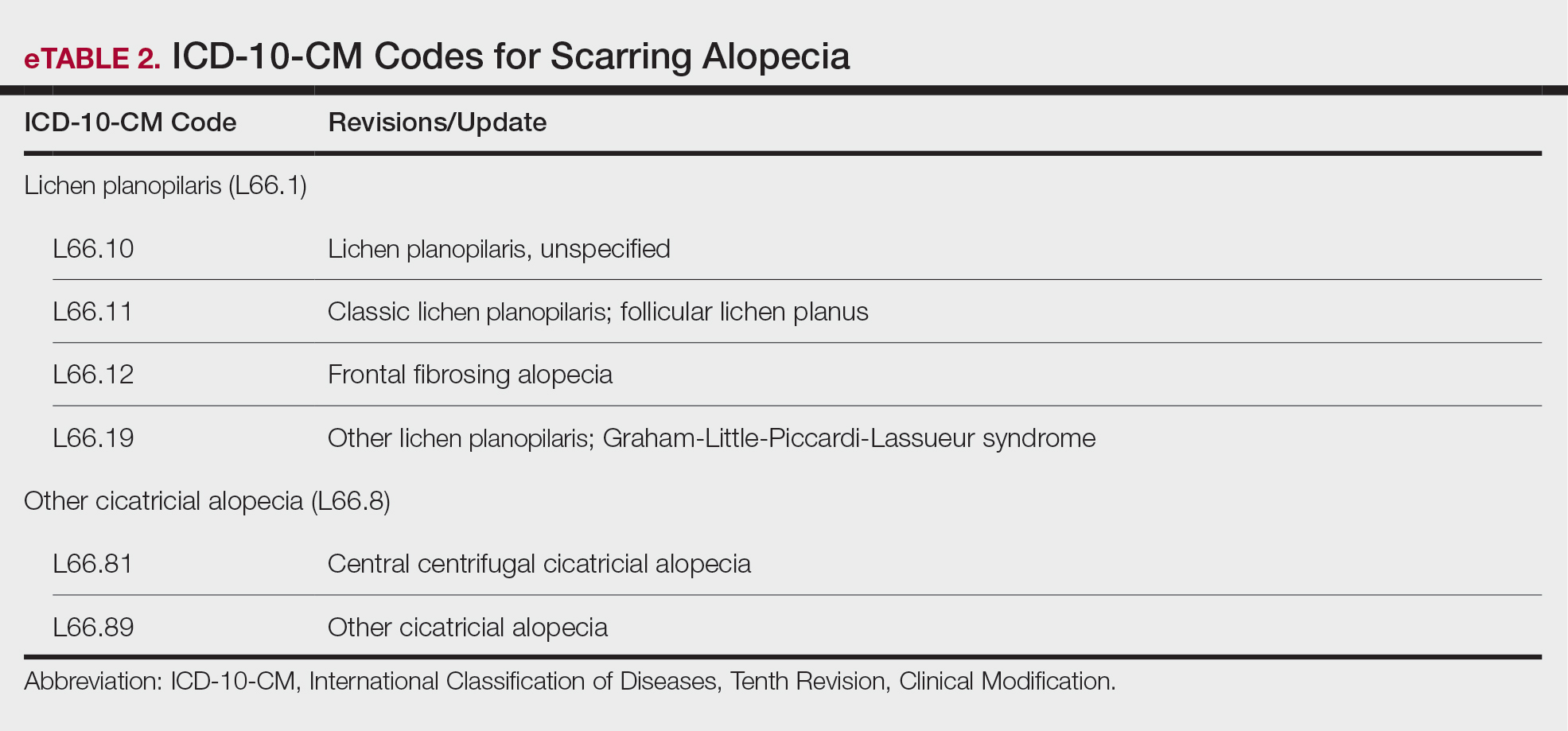

New Codes for Alopecia and Acne Surgery

New International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes for alopecia have been developed through collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation (eTable 2). Cutaneous extraction—previously coded as acne surgery (CPT code 10040)—will now be listed in the 2026 CPT coding manual as “extraction” (eg, marsupialization, opening of multiple milia, acne comedones, cysts, pustules).14

Quality Payment Program Update

The MIPS performance threshold will remain at 75 for the 2025 performance period, impacting the 2027 payment year.15 The MIPS Value Pathways will be available but optional in 2025, and the CMS plans to fully replace MIPS by 2029. The goal for the MVPs is to reduce the administrative burden of MIPS for physicians and their staff while simplifying reporting; however, there are several concerns. The MIPS Value Pathways build on the MIPS’s flawed processes; compare the cost for one condition to the quality of another; continue to be burdensome to physicians; have not demonstrated improved patient care; are a broad, one-size-fits-all model that could lead to inequity based on practice mix; and are not clinically relevant to physicians and patients.15

Beginning in 2025, dermatologists also will have access to a new high-priority quality measure—Melanoma: Tracking and Evaluation of Recurrence—and the Melanoma: Continuity of Care–Recall System measure (MIPS measure 137) will be removed starting in 2025.15

What Can Dermatologists Do?

With the fifth consecutive year of payment cuts, the cumulative reduction to physician payments has reached an untenable level, and physicians cannot continue to absorb the reductions, which impact access and ability to provide patient care. Members of the American Academy of Dermatology Association must urge members of Congress to stop the cuts and find a permanent solution to fix Medicare physician payment by asking their representatives to cosponsor the following bills in the US House of Representatives and Senate16:

- HR 10073—The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024 would stop the 2.8% cut to the 2025 MPFS and provide a positive inflationary adjustment for physician practices equal to 50% of the 2025 MEI, which comes down to an increase of approximately 1.8%.17

- HR 2424—The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act would provide an annual inflation update equal to the MEI for Medicare physician payments.18

- HR 6371—The Provider Reimbursement Stability Act would revise budget neutrality policies that contribute to eroding Medicare physician reimbursement.19

- S 4935—The Physician Fee Stabilization Act would increase the budget neutrality trigger from $20 million to $53 million.20

Advocacy is critically important: be engaged and get involved in grassroots efforts to protect access to health care, as these cuts do nothing to curb health care costs.

Final Thoughts

Congress has failed to address declining Medicare reimbursement rates, allowing cuts that jeopardize patient access to care as physicians close or sell their practices. It is important for dermatologists to attend the American Medical Association’s National Advocacy Conference in February 2025, which will feature an event on fixing Medicare. Dermatologists also can join prominent House members in urging Congress to reverse Medicare cuts and reform the physician payment system as well as write to their representatives and share how these cuts impact their practices and patients.

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Office of the Actuary. National Health Statistics Group. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/files/document/nations-health-dollar-where-it-came-where-it-went.pdf

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule. July 10, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-proposed-rule

- RVS Update Committee (RUC). RBRVS overview. American Medical Association. Updated November 8, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/about/rvs-update-committee-ruc/rbrvs-overview

- American Medical Association. History of Medicare conversion charts. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/system/files/cf-history.pdf

- American Medical Association. Medicare basics series: the Medicare Economic Index. June 3, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/medicare-basics-series-medicare-economic-index

- O’Reilly KB. Physician answers on this survey will shape future Medicare pay. American Medical Association. November 3, 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/medicare-medicaid/physician-answers-survey-will-shape-future-medicare-pay

- Solis E. Stopgap spending bill extends telehealth flexibility, Medicare payment relief still awaits. American Academy of Family Physicians. December 3, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/fpm/blogs/gettingpaid/entry/2024-shutdown-averted.html

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Calendar year (CY) 2025 Medicare physician fee schedule final rule. November 1, 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/calendar-year-cy-2025-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-final-rulen

- Novitas Solutions. Other CPT modifiers. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.novitas-solutions.com/webcenter/portal/MedicareJH/pagebyid?contentId=00144515

- Medical team conference, without direct (face-to-face) contact with patient and/or family CPT® code range 99367-99368. Codify by AAPC. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aapc.com/codes/cpt-codes-range/99367-99368/

- McNichols FCM. Cracking the code. DermWorld. November 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://digitaleditions.walsworth.com/publication/?i=806167&article_id=4666988

- McNichols FCM. Coding Consult. Derm World. Published April 2024. https://www.aad.org/dw/monthly/2024/may/dcc-hcpcs-add-on-code-g2211

- Venkatesh KP, Jothishankar B, Nambudiri VE. Incorporating social determinants of health into medical decision-making -implications for dermatology. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159:367-368.

- McNichols FCM. Coding consult. DermWorld. October 2024. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://digitaleditions.walsworth.com/publication/?i=832260&article_id=4863646

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Quality Payment Program. Dermatologic care MVP candidate. December 1, 2023. Updated December 15, 2023. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://qpp.cms.gov/resources/document/78e999ba-3690-4e02-9b35-6cc7c98d840b

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. AADA advocacy action center. Accessed January 10, 2025. https://www.aad.org/member/advocacy/take-action

- Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024, HR 10073, 118th Congress (NC 2024).

- Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act, HR 2424, 118th Congress (CA 2023).

- Provider Reimbursement Stability Act, HR 6371, 118th Congress (NC 2023).

- Physician Fee Stabilization Act. S 4935. 2023-2024 Session (AR 2024).

Health care costs continue to increase in 2025 while physician reimbursement continues to decrease. Of the $4.5 trillion spent on health care in 2022, only 20% was spent on physician and clinical services.1 Since 2001, practice expense has risen 47%, while the Consumer Price Index has risen 73%; adjusted for inflation, physician reimbursement has declined 30% since 2001.2

The formula for Medicare payments for physician services, calculated by multiplying the conversion factor (CF) by the relative value unit (RVU), was developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 1992. The combination of the physician’s work, the practice’s expense, and the cost of professional liability insurance make up RVUs, which are aligned by geographic index adjustments.3 The 2024 CF was $32.75, compared to $32.00 in 1992. The proposed 2025 CF is $32.35, which is a 10% decrease since 2019 and a 2.8% decrease relative to the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). The 2.8% cut is due to expiration of the 2.93% temporary payment increase for services provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2024 and the supplemental relief provided from March 9, 2024, to December 31, 2024.4 If the CF had increased with inflation, it would have been $71.15 in 2024.4

Declining reimbursement rates for physician services undermine the ability of physician practices to keep their doors open in the face of increased operating costs. Faced with the widening gap between what Medicare pays for physician services and the cost of delivering value-based, quality care, physicians are urging Congress to pass a reform package to permanently strengthen Medicare.

Herein, an overview of key coding updates and changes, telehealth flexibilities, and a new dermatologyfocused Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways is provided.

Update on the Medicare Economic Index Postponement

Developed in 1975, the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) is a measure of practice cost inflation. It is a yearly calculation that estimates the annual changes in physicians’ operating costs to determine appropriate Medicare physician payment updates.5 The MEI is composed of physician practice costs (eg, staff salaries, office space, malpractice insurance) and physician compensation (direct earnings by the physician). Both are used to calculate adjustments to Medicare physician payments to account for inflationary increases in health care costs. The MEI for 2025 is projected to increase by 3.5%, while physician payment continues to dwindle.5 This disparity between rising costs and declining physician payments will impact patient access to medical care. Physicians may choose to stop accepting Medicare and other health insurance, face the possibility of closing or selling their practices, or even decide to leave the profession.

The CMS has continued to delay implementation of the 2017 MEI cost weights (which currently are based on 2006 data5) for RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2025 pending completion of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Practice Information Survey.6 The AMA contracted with an independent research company to conduct the survey, which will be used to update the MEI. Survey data will be shared with the CMS in early 2025.6

Future of Telehealth is Uncertain

On January 1, 2025, many telehealth flexibilities were set to expire; however, Congress passed an extension of the current telehealth policy flexibilities that have been in place since the COVID-19 pandemic through March 31, 2025.7 The CMS recognizes concerns about maintaining access to Medicare telehealth services once the statutory flexibilities expire; however, it maintains that it has limited statutory authority to extend these Medicare telehealth flexibilities.8 There will be originating site requirements and geographic location restrictions. Clinicians working in a federally qualified health center or a rural health clinic would not be affected.8

The CMS rejected adoption of 16 of 17 new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (98000–98016) for telemedicine evaluation and management (E/M) services, rendering them nonreimbursable.8 Physicians should continue to use the standard E/M codes 99202 through 99215 for telehealth visits. The CMS only approved code 99016, which will replace Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2012, for brief virtual check-in encounters. The CMS specified that CPT codes 99441 through 99443, which describe telephone E/M services, have been removed and are no longer valid for billing. Asynchronous communication (eg, store-and-forward technology via an electronic health record portal) will continue to be reported using the online digital E/M service codes 99421, 99422, and 99423.8

Practitioners can use their enrolled practice location instead of their home address when providing telehealth services from home.8 Teaching physicians will continue to be allowed to have a virtual presence for purposes of billing for services involving residents in all teaching settings, but only when the service is furnished remotely (ie, the patient, resident, and teaching physician all are in separate locations). The use of real-time audio and video technology for direct supervision has been extended through December 31, 2025, allowing practitioners to be immediately available virtually. The CMS also plans to permanently allow virtual supervision for lower-risk services that typically do not require the billing practitioner’s physical presence or extensive direction (eg, diagnostic tests, behavioral health, dermatology, therapy).8

It is essential to verify the reimbursement policies and billing guidelines of individual payers, as some may adopt policies that differ from the AMA and CMS guidelines.

When to Use Modifiers -59 and -76

Modifiers -59 and -76 are used when billing for multiple procedures on the same day and can be confused. These modifiers help clarify situations in which procedures might appear redundant or improperly coded, reducing the risk for claim denials and ensuring compliance with coding guidelines. Use modifier -59 when a procedure or service is distinct or separate from other services performed on the same day (eg, cryosurgery of 4 actinic keratoses and a tangential biopsy of a nevus). Use modifier -76 when a physician performs the exact same procedure multiple times on the same patient on the same day (eg, removing 2 nevi on the face with the same excision code or performing multiple biopsies on different areas on the skin).9

What Are the Medical Team Conference CPT Codes?

Dermatologists frequently manage complex medical and surgical cases and actively participate in tumor boards and multidisciplinary teams conferences. It is essential to be familiar with the relevant CPT codes that can be used in these scenarios: CPT code 99366 can be used when the medical team conference occurs face-to-face with the patient present, and CPT code 99367 can be used for a medical team conference with an interdisciplinary group of health care professionals from different specialties, each of whom provides direct care to the patient.10 For CPT code 99367, the patient and/or family are not present during the meeting, which lasts a minimum of 30 minutes or more and requires participation by a physician. Current Procedural Terminology code 99368 can be used for participation in the medical team conference by a nonphysician qualified health care professional. The reporting participants need to document their participation in the medical team conference as well as their contributed information that explains the case and subsequent treatment recommendations.10

No more than 1 individual from the same specialty may report CPT codes 99366 through 99368 at the same encounter.10 Codes 99366 through 99368 should not be reported when participation in the medical team conference is part of a facility or contractually provided by the facility such as group therapy.10 The medical team conference starts at the beginning of the review of an individual patient and ends at the conclusion of the review for coding purposes. Time related to record-keeping or report generation does not need to be reported. The reporting participant needs to be present for the entire conference. The time reported is not limited to the time that the participant is communicating with other team members or the patient and/or their family/ caregiver(s). Time reported for medical team conferences may not be used in the determination for other services, such as care plan oversight (99374-99380), prolonged services (99358, 99359), psychotherapy, or any E/M service. When the patient is present for any part of the duration of the team conference, nonphysician qualified health care professionals (eg, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, occupational therapists, social workers, dietitians) report the medical team conference face-to-face with code 99366.10

Update on Excimer Laser CPT Codes

The CMS rejected values recommended for CPT codes (96920-96922) by the Relative Value Scale Update Committee, proposing lower work RVUs of 0.83, 0.90, and 1.15, respectively (Table).2,11 The CPT panel did not recognize the strength of the literature supporting the expanded use of the codes for conditions other than psoriasis. Report the use of excimer laser for treatment of vitiligo, atopic dermatitis, and alopecia areata using CPT code 96999 (unlisted special dermatological service or procedure).11

Update on the New G2211 Code

Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2211 is an add-on complexity code that can be reported with all outpatient E/M visits to better account for additional resources associated with primary care or similarly ongoing medical care related to a patient’s single serious condition or complex condition.12 It can be billed if the physician is serving as the continuing focal point for all the patient's health care service needs, acting as the central point of contact for the patient’s ongoing medical care, and managing all aspects of their health needs over time. It is not restricted based on specialty, but it is determined based on the nature of the physician-patient relationship.12

Code G2211 should not be used for the following scenarios: (1) care provided by a clinician with a discrete, routine, or time-limited relationship with the patient, such as a routine skin examination or an acute allergic contact dermatitis; (2) conditions in which comorbidities are not present or addressed; (3) when the billing clinician has not assumed responsibility for ongoing medical care with consistency and continuity over time; and (4) visits billed with modifier -25.12 In the 2025 MPFS, the CMS is proposing to allow payment of G2211 when the code is reported by the same practitioner on the same day as an annual wellness visit, vaccine administration, or any Medicare Part B preventive service furnished in the office or outpatient setting (ie, creating a limited exception to the prohibition of using this code with modifier -25).2

Documentation in the medical record must support reporting code G2211 and indicate a medically reasonable and necessary reason for the additional RVUs (0.33 and additional payment of $16.05).12

Underutilization of Z Codes for Social Determinants of Health

Barriers to documentation of social determinants of health (SDOH)–related International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Z codes (Z55-Z66)(eTable 1), include lack of clarity on who can document patients’ social needs, lack of systems and processes for documenting and coding SDOH, unfamiliarity with these Z codes, and a low prioritization of collecting these data.13 Documentation of a SDOH-related Z code relevant to a patient encounter is considered moderate risk and can have a major impact on a patient’s overall health, unmet social needs, and outcomes.13 If the other 2 medical decision-making elements (ie, number and complexity of problems addressed along with amount and/or complexity of data to be reviewed and analyzed) for the E/M visit also are moderate, then the encounter can be coded as level 4.13

New Codes for Alopecia and Acne Surgery

New International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification, codes for alopecia have been developed through collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Scarring Alopecia Foundation (eTable 2). Cutaneous extraction—previously coded as acne surgery (CPT code 10040)—will now be listed in the 2026 CPT coding manual as “extraction” (eg, marsupialization, opening of multiple milia, acne comedones, cysts, pustules).14

Quality Payment Program Update

The MIPS performance threshold will remain at 75 for the 2025 performance period, impacting the 2027 payment year.15 The MIPS Value Pathways will be available but optional in 2025, and the CMS plans to fully replace MIPS by 2029. The goal for the MVPs is to reduce the administrative burden of MIPS for physicians and their staff while simplifying reporting; however, there are several concerns. The MIPS Value Pathways build on the MIPS’s flawed processes; compare the cost for one condition to the quality of another; continue to be burdensome to physicians; have not demonstrated improved patient care; are a broad, one-size-fits-all model that could lead to inequity based on practice mix; and are not clinically relevant to physicians and patients.15

Beginning in 2025, dermatologists also will have access to a new high-priority quality measure—Melanoma: Tracking and Evaluation of Recurrence—and the Melanoma: Continuity of Care–Recall System measure (MIPS measure 137) will be removed starting in 2025.15

What Can Dermatologists Do?

With the fifth consecutive year of payment cuts, the cumulative reduction to physician payments has reached an untenable level, and physicians cannot continue to absorb the reductions, which impact access and ability to provide patient care. Members of the American Academy of Dermatology Association must urge members of Congress to stop the cuts and find a permanent solution to fix Medicare physician payment by asking their representatives to cosponsor the following bills in the US House of Representatives and Senate16:

- HR 10073—The Medicare Patient Access and Practice Stabilization Act of 2024 would stop the 2.8% cut to the 2025 MPFS and provide a positive inflationary adjustment for physician practices equal to 50% of the 2025 MEI, which comes down to an increase of approximately 1.8%.17

- HR 2424—The Strengthening Medicare for Patients and Providers Act would provide an annual inflation update equal to the MEI for Medicare physician payments.18

- HR 6371—The Provider Reimbursement Stability Act would revise budget neutrality policies that contribute to eroding Medicare physician reimbursement.19

- S 4935—The Physician Fee Stabilization Act would increase the budget neutrality trigger from $20 million to $53 million.20

Advocacy is critically important: be engaged and get involved in grassroots efforts to protect access to health care, as these cuts do nothing to curb health care costs.

Final Thoughts

Congress has failed to address declining Medicare reimbursement rates, allowing cuts that jeopardize patient access to care as physicians close or sell their practices. It is important for dermatologists to attend the American Medical Association’s National Advocacy Conference in February 2025, which will feature an event on fixing Medicare. Dermatologists also can join prominent House members in urging Congress to reverse Medicare cuts and reform the physician payment system as well as write to their representatives and share how these cuts impact their practices and patients.

Health care costs continue to increase in 2025 while physician reimbursement continues to decrease. Of the $4.5 trillion spent on health care in 2022, only 20% was spent on physician and clinical services.1 Since 2001, practice expense has risen 47%, while the Consumer Price Index has risen 73%; adjusted for inflation, physician reimbursement has declined 30% since 2001.2

The formula for Medicare payments for physician services, calculated by multiplying the conversion factor (CF) by the relative value unit (RVU), was developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) in 1992. The combination of the physician’s work, the practice’s expense, and the cost of professional liability insurance make up RVUs, which are aligned by geographic index adjustments.3 The 2024 CF was $32.75, compared to $32.00 in 1992. The proposed 2025 CF is $32.35, which is a 10% decrease since 2019 and a 2.8% decrease relative to the 2024 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (MPFS). The 2.8% cut is due to expiration of the 2.93% temporary payment increase for services provided by the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2024 and the supplemental relief provided from March 9, 2024, to December 31, 2024.4 If the CF had increased with inflation, it would have been $71.15 in 2024.4

Declining reimbursement rates for physician services undermine the ability of physician practices to keep their doors open in the face of increased operating costs. Faced with the widening gap between what Medicare pays for physician services and the cost of delivering value-based, quality care, physicians are urging Congress to pass a reform package to permanently strengthen Medicare.

Herein, an overview of key coding updates and changes, telehealth flexibilities, and a new dermatologyfocused Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) Value Pathways is provided.

Update on the Medicare Economic Index Postponement

Developed in 1975, the Medicare Economic Index (MEI) is a measure of practice cost inflation. It is a yearly calculation that estimates the annual changes in physicians’ operating costs to determine appropriate Medicare physician payment updates.5 The MEI is composed of physician practice costs (eg, staff salaries, office space, malpractice insurance) and physician compensation (direct earnings by the physician). Both are used to calculate adjustments to Medicare physician payments to account for inflationary increases in health care costs. The MEI for 2025 is projected to increase by 3.5%, while physician payment continues to dwindle.5 This disparity between rising costs and declining physician payments will impact patient access to medical care. Physicians may choose to stop accepting Medicare and other health insurance, face the possibility of closing or selling their practices, or even decide to leave the profession.

The CMS has continued to delay implementation of the 2017 MEI cost weights (which currently are based on 2006 data5) for RVUs in the MPFS rate setting for 2025 pending completion of the American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Practice Information Survey.6 The AMA contracted with an independent research company to conduct the survey, which will be used to update the MEI. Survey data will be shared with the CMS in early 2025.6

Future of Telehealth is Uncertain

On January 1, 2025, many telehealth flexibilities were set to expire; however, Congress passed an extension of the current telehealth policy flexibilities that have been in place since the COVID-19 pandemic through March 31, 2025.7 The CMS recognizes concerns about maintaining access to Medicare telehealth services once the statutory flexibilities expire; however, it maintains that it has limited statutory authority to extend these Medicare telehealth flexibilities.8 There will be originating site requirements and geographic location restrictions. Clinicians working in a federally qualified health center or a rural health clinic would not be affected.8

The CMS rejected adoption of 16 of 17 new Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes (98000–98016) for telemedicine evaluation and management (E/M) services, rendering them nonreimbursable.8 Physicians should continue to use the standard E/M codes 99202 through 99215 for telehealth visits. The CMS only approved code 99016, which will replace Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System code G2012, for brief virtual check-in encounters. The CMS specified that CPT codes 99441 through 99443, which describe telephone E/M services, have been removed and are no longer valid for billing. Asynchronous communication (eg, store-and-forward technology via an electronic health record portal) will continue to be reported using the online digital E/M service codes 99421, 99422, and 99423.8