User login

Payment changes drive hysteroscopy to the office

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice have been compelling for some time. An in-office approach is patient centered, more efficient, and clinically valuable. It also has had the potential to be economically valuable for practices that are able to perform a mix of diagnostic and therapeutic/operative hysteroscopies.

Dramatic shifts within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services fee schedule in 2017 – and commensurate changes in the private insurance market – have now ramped up this value, making it all the more important that physicians consider investing in equipment and adopting an in-office approach.

Central to this increase, in turn, is a significant increase in practice expense reimbursement. CMS has included the costs of equipment, including the costs of the hysteroscopic fluid management system and the hysteroscopic tissue resection system, in recalibrating the practice expense relative value unit. Clearly, physicians are being encouraged to move hysteroscopic procedures into the office.

Weighing an investment

In the Medicare resource-based relative value scale payment system, relative value units (RVUs) are calculated based on three elements: physician work, practice expenses, and malpractice cost. Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

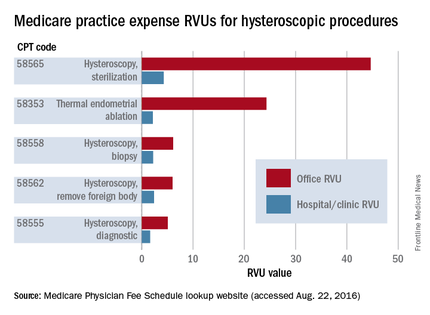

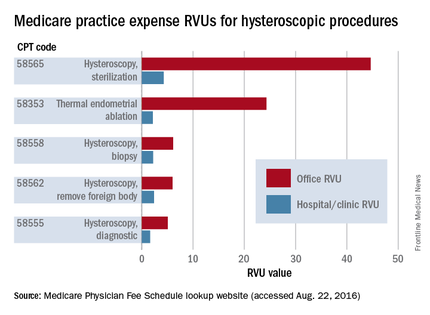

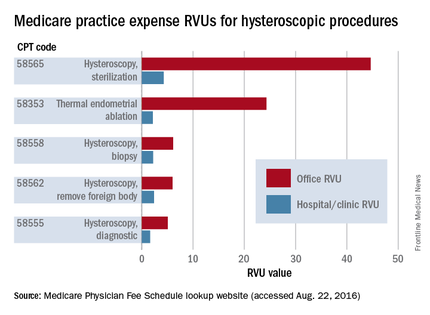

This isn’t the first year that the payment system – a standard for many other payers in determining compensation – allows for higher reimbursement for some hysteroscopic procedures performed in the office. The practice expense relative units have been higher for some time for certain hysteroscopic procedures – such as diagnostic hysteroscopy (code 58555), removal of a foreign body (58562), endometrial ablation (58353), and biopsy/polypectomy (58558) – when these procedures are performed in the office, compared with the hospital or an ambulatory surgical center.

However, the new increase in physician office payment for 58558 changes the equation significantly and ensures a better return on investment. In 2017, CMS offered a 12% increase in the facility fee paid to hospitals and a 2% increase in the facility fee paid to outpatient surgery centers when a hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy is performed in these settings, but the physician reimbursement in these cases declined 11%-19%.

On the flip side, an in-office approach to hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy has been rewarded in 2017 through a significantly higher practice expense RVU and a “non-facility” total RVU of 38.51 – a 237% increase over the 2016 practice expense RVU of 11.4. Such dramatic differences between the practice RVUs – and total RVUs – for in-office and out-of-office hysteroscopic procedures will continue for 2018.

Private insurers are following suit, and some are increasing their reimbursement even more. As of June 2017 in metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield has been reimbursing in-office hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy at approximately $2,424.00; prior to June, the allowable charge was $742.81.

Equipment costs for in-office hysteroscopy can range from $15,000 to $35,000, based on whether equipment is new or used, the number of trays, and the style of camera and monitor system. Ancillary equipment/disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-$50 or less for diagnostic and many operative procedures, respectively. The prices for handpiece mechanical resection disposables or tissue removal devices vary based on company and blade type, so these costs will need to be accounted for if such equipment is incorporated. Again, the CMS increase in reimbursement for offices accommodates for the inclusion of these disposables as well as fluid management disposable costs.

If diagnostic hysteroscopy (as a separate procedure) is the procedure that you perform most often, the investment will look less favorable. However, if you anticipate performing hysteroscopic biopsies and/or polypectomies as well, the investment will look significantly more favorable now than it has in past years.

Once you have established your in-office system, even those procedures that are weighted equally for the practice setting (non-facility) and hospital/surgery center setting, such as hysteroscopic lysis of adhesions (58559), can be easily incorporated from a financial point of view.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. The setup is relatively simple and requires a dedicated exam room, not a surgical suite. You can perform one or two annual exams while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Hysteroscopy at the hospital, or even at an ambulatory surgical center, involves time driving, changing, and waiting for anesthesia.

For our patients, most importantly, an in-office approach offers less out-of-pocket expense (deductibles), less time away from family/work, avoidance of general anesthesia/intubation, and greater patient comfort from being within a familiar environment. For diagnostic procedures, the patient can be in and out in less than 30 minutes, and for operative procedures, she can be in and out in 1-2 hours, compared with more than 4 hours at the hospital.

Preparing the office

Physicians in Europe have been performing in-office hysteroscopy for years. But in the United States, it is a newer concept, with most gynecologic surgeons having been taught to perform surgical procedures in the operating room. Undoubtedly, our unfamiliarity with in-office surgery has played a role in the slow uptake of hysteroscopy in our practices.

Open communication about everything the patient will see hear and feel before, during and after the procedure is important. Focusing on these details can improve your patient’s experience and your professional relationship with her.

In an earlier edition of Master Class, I addressed instrumentation and technique, elements of pain control and anesthesia, and the value of a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy. Vaginoscopy avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, and is so tolerable to many patients that I use minimal premedication and only rarely use any local anesthetic and/or sedation, even for biopsies and polypectomies.

Preparing your practice for hysteroscopy is a multifaceted process involving not only the purchase and/or rental of equipment but also compliance with guidelines, regulatory considerations, patient rights, hospital transfer arrangements, and other issues. ACOG’s Report of the Presidential Task Force on Patient Safety in the Office Setting is a valuable resource for getting started. The report discusses anesthesia levels and the benefits and risks of a contract anesthesiologist, for instance, as well as the role of and processes for credentialing, privileging, and accreditation.

Checklists and drills are important for ensuring a safe practice, and the report discusses each of these elements and provides templates and examples. A sample “Office Surgical Safety Checklist” to be used for each procedure, for instance, has sections with preoperative steps (before anesthesia/analgesia, and before incision), intraoperative steps, postoperative steps, and discharge steps. Similar in format to checklists used in the aviation industry, each step has a box to be checked off to verify completion.

Mock drills help ensure that staff are knowledgeable about their roles and coordinated in their response to potential complications, such as vasovagal episodes, respiratory arrest caused by laryngospasm, and local anesthetic toxicity reactions. And, while not the focus of drills, we also must be prepared to manage cervical strictures and stenosis, cervical laceration, uterine perforation, and other complications.

Outpatient surgery guidelines from organizations such as the American College of Surgeons, the Joint Commission, state regulatory agencies, and professional liability insurers, can also be useful resources. With the use of ACOG’s report and other such resources, the set-up and the transition to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting. For most gynecologic surgeons, it will all feel comfortable after only a few procedures.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is with the University of Illinois at Chicago, and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. She is in private practice in Chicago. She is a consultant for Hologic, Bayer HealthCare, Olympus, Caldera Medical, Karl Storz, Medtronic, DYSIS Medical, and Channel Medsystems.

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice have been compelling for some time. An in-office approach is patient centered, more efficient, and clinically valuable. It also has had the potential to be economically valuable for practices that are able to perform a mix of diagnostic and therapeutic/operative hysteroscopies.

Dramatic shifts within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services fee schedule in 2017 – and commensurate changes in the private insurance market – have now ramped up this value, making it all the more important that physicians consider investing in equipment and adopting an in-office approach.

Central to this increase, in turn, is a significant increase in practice expense reimbursement. CMS has included the costs of equipment, including the costs of the hysteroscopic fluid management system and the hysteroscopic tissue resection system, in recalibrating the practice expense relative value unit. Clearly, physicians are being encouraged to move hysteroscopic procedures into the office.

Weighing an investment

In the Medicare resource-based relative value scale payment system, relative value units (RVUs) are calculated based on three elements: physician work, practice expenses, and malpractice cost. Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

This isn’t the first year that the payment system – a standard for many other payers in determining compensation – allows for higher reimbursement for some hysteroscopic procedures performed in the office. The practice expense relative units have been higher for some time for certain hysteroscopic procedures – such as diagnostic hysteroscopy (code 58555), removal of a foreign body (58562), endometrial ablation (58353), and biopsy/polypectomy (58558) – when these procedures are performed in the office, compared with the hospital or an ambulatory surgical center.

However, the new increase in physician office payment for 58558 changes the equation significantly and ensures a better return on investment. In 2017, CMS offered a 12% increase in the facility fee paid to hospitals and a 2% increase in the facility fee paid to outpatient surgery centers when a hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy is performed in these settings, but the physician reimbursement in these cases declined 11%-19%.

On the flip side, an in-office approach to hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy has been rewarded in 2017 through a significantly higher practice expense RVU and a “non-facility” total RVU of 38.51 – a 237% increase over the 2016 practice expense RVU of 11.4. Such dramatic differences between the practice RVUs – and total RVUs – for in-office and out-of-office hysteroscopic procedures will continue for 2018.

Private insurers are following suit, and some are increasing their reimbursement even more. As of June 2017 in metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield has been reimbursing in-office hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy at approximately $2,424.00; prior to June, the allowable charge was $742.81.

Equipment costs for in-office hysteroscopy can range from $15,000 to $35,000, based on whether equipment is new or used, the number of trays, and the style of camera and monitor system. Ancillary equipment/disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-$50 or less for diagnostic and many operative procedures, respectively. The prices for handpiece mechanical resection disposables or tissue removal devices vary based on company and blade type, so these costs will need to be accounted for if such equipment is incorporated. Again, the CMS increase in reimbursement for offices accommodates for the inclusion of these disposables as well as fluid management disposable costs.

If diagnostic hysteroscopy (as a separate procedure) is the procedure that you perform most often, the investment will look less favorable. However, if you anticipate performing hysteroscopic biopsies and/or polypectomies as well, the investment will look significantly more favorable now than it has in past years.

Once you have established your in-office system, even those procedures that are weighted equally for the practice setting (non-facility) and hospital/surgery center setting, such as hysteroscopic lysis of adhesions (58559), can be easily incorporated from a financial point of view.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. The setup is relatively simple and requires a dedicated exam room, not a surgical suite. You can perform one or two annual exams while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Hysteroscopy at the hospital, or even at an ambulatory surgical center, involves time driving, changing, and waiting for anesthesia.

For our patients, most importantly, an in-office approach offers less out-of-pocket expense (deductibles), less time away from family/work, avoidance of general anesthesia/intubation, and greater patient comfort from being within a familiar environment. For diagnostic procedures, the patient can be in and out in less than 30 minutes, and for operative procedures, she can be in and out in 1-2 hours, compared with more than 4 hours at the hospital.

Preparing the office

Physicians in Europe have been performing in-office hysteroscopy for years. But in the United States, it is a newer concept, with most gynecologic surgeons having been taught to perform surgical procedures in the operating room. Undoubtedly, our unfamiliarity with in-office surgery has played a role in the slow uptake of hysteroscopy in our practices.

Open communication about everything the patient will see hear and feel before, during and after the procedure is important. Focusing on these details can improve your patient’s experience and your professional relationship with her.

In an earlier edition of Master Class, I addressed instrumentation and technique, elements of pain control and anesthesia, and the value of a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy. Vaginoscopy avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, and is so tolerable to many patients that I use minimal premedication and only rarely use any local anesthetic and/or sedation, even for biopsies and polypectomies.

Preparing your practice for hysteroscopy is a multifaceted process involving not only the purchase and/or rental of equipment but also compliance with guidelines, regulatory considerations, patient rights, hospital transfer arrangements, and other issues. ACOG’s Report of the Presidential Task Force on Patient Safety in the Office Setting is a valuable resource for getting started. The report discusses anesthesia levels and the benefits and risks of a contract anesthesiologist, for instance, as well as the role of and processes for credentialing, privileging, and accreditation.

Checklists and drills are important for ensuring a safe practice, and the report discusses each of these elements and provides templates and examples. A sample “Office Surgical Safety Checklist” to be used for each procedure, for instance, has sections with preoperative steps (before anesthesia/analgesia, and before incision), intraoperative steps, postoperative steps, and discharge steps. Similar in format to checklists used in the aviation industry, each step has a box to be checked off to verify completion.

Mock drills help ensure that staff are knowledgeable about their roles and coordinated in their response to potential complications, such as vasovagal episodes, respiratory arrest caused by laryngospasm, and local anesthetic toxicity reactions. And, while not the focus of drills, we also must be prepared to manage cervical strictures and stenosis, cervical laceration, uterine perforation, and other complications.

Outpatient surgery guidelines from organizations such as the American College of Surgeons, the Joint Commission, state regulatory agencies, and professional liability insurers, can also be useful resources. With the use of ACOG’s report and other such resources, the set-up and the transition to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting. For most gynecologic surgeons, it will all feel comfortable after only a few procedures.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is with the University of Illinois at Chicago, and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. She is in private practice in Chicago. She is a consultant for Hologic, Bayer HealthCare, Olympus, Caldera Medical, Karl Storz, Medtronic, DYSIS Medical, and Channel Medsystems.

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice have been compelling for some time. An in-office approach is patient centered, more efficient, and clinically valuable. It also has had the potential to be economically valuable for practices that are able to perform a mix of diagnostic and therapeutic/operative hysteroscopies.

Dramatic shifts within the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services fee schedule in 2017 – and commensurate changes in the private insurance market – have now ramped up this value, making it all the more important that physicians consider investing in equipment and adopting an in-office approach.

Central to this increase, in turn, is a significant increase in practice expense reimbursement. CMS has included the costs of equipment, including the costs of the hysteroscopic fluid management system and the hysteroscopic tissue resection system, in recalibrating the practice expense relative value unit. Clearly, physicians are being encouraged to move hysteroscopic procedures into the office.

Weighing an investment

In the Medicare resource-based relative value scale payment system, relative value units (RVUs) are calculated based on three elements: physician work, practice expenses, and malpractice cost. Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

This isn’t the first year that the payment system – a standard for many other payers in determining compensation – allows for higher reimbursement for some hysteroscopic procedures performed in the office. The practice expense relative units have been higher for some time for certain hysteroscopic procedures – such as diagnostic hysteroscopy (code 58555), removal of a foreign body (58562), endometrial ablation (58353), and biopsy/polypectomy (58558) – when these procedures are performed in the office, compared with the hospital or an ambulatory surgical center.

However, the new increase in physician office payment for 58558 changes the equation significantly and ensures a better return on investment. In 2017, CMS offered a 12% increase in the facility fee paid to hospitals and a 2% increase in the facility fee paid to outpatient surgery centers when a hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy is performed in these settings, but the physician reimbursement in these cases declined 11%-19%.

On the flip side, an in-office approach to hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy has been rewarded in 2017 through a significantly higher practice expense RVU and a “non-facility” total RVU of 38.51 – a 237% increase over the 2016 practice expense RVU of 11.4. Such dramatic differences between the practice RVUs – and total RVUs – for in-office and out-of-office hysteroscopic procedures will continue for 2018.

Private insurers are following suit, and some are increasing their reimbursement even more. As of June 2017 in metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield has been reimbursing in-office hysteroscopic biopsy/polypectomy at approximately $2,424.00; prior to June, the allowable charge was $742.81.

Equipment costs for in-office hysteroscopy can range from $15,000 to $35,000, based on whether equipment is new or used, the number of trays, and the style of camera and monitor system. Ancillary equipment/disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-$50 or less for diagnostic and many operative procedures, respectively. The prices for handpiece mechanical resection disposables or tissue removal devices vary based on company and blade type, so these costs will need to be accounted for if such equipment is incorporated. Again, the CMS increase in reimbursement for offices accommodates for the inclusion of these disposables as well as fluid management disposable costs.

If diagnostic hysteroscopy (as a separate procedure) is the procedure that you perform most often, the investment will look less favorable. However, if you anticipate performing hysteroscopic biopsies and/or polypectomies as well, the investment will look significantly more favorable now than it has in past years.

Once you have established your in-office system, even those procedures that are weighted equally for the practice setting (non-facility) and hospital/surgery center setting, such as hysteroscopic lysis of adhesions (58559), can be easily incorporated from a financial point of view.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. The setup is relatively simple and requires a dedicated exam room, not a surgical suite. You can perform one or two annual exams while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Hysteroscopy at the hospital, or even at an ambulatory surgical center, involves time driving, changing, and waiting for anesthesia.

For our patients, most importantly, an in-office approach offers less out-of-pocket expense (deductibles), less time away from family/work, avoidance of general anesthesia/intubation, and greater patient comfort from being within a familiar environment. For diagnostic procedures, the patient can be in and out in less than 30 minutes, and for operative procedures, she can be in and out in 1-2 hours, compared with more than 4 hours at the hospital.

Preparing the office

Physicians in Europe have been performing in-office hysteroscopy for years. But in the United States, it is a newer concept, with most gynecologic surgeons having been taught to perform surgical procedures in the operating room. Undoubtedly, our unfamiliarity with in-office surgery has played a role in the slow uptake of hysteroscopy in our practices.

Open communication about everything the patient will see hear and feel before, during and after the procedure is important. Focusing on these details can improve your patient’s experience and your professional relationship with her.

In an earlier edition of Master Class, I addressed instrumentation and technique, elements of pain control and anesthesia, and the value of a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy. Vaginoscopy avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, and is so tolerable to many patients that I use minimal premedication and only rarely use any local anesthetic and/or sedation, even for biopsies and polypectomies.

Preparing your practice for hysteroscopy is a multifaceted process involving not only the purchase and/or rental of equipment but also compliance with guidelines, regulatory considerations, patient rights, hospital transfer arrangements, and other issues. ACOG’s Report of the Presidential Task Force on Patient Safety in the Office Setting is a valuable resource for getting started. The report discusses anesthesia levels and the benefits and risks of a contract anesthesiologist, for instance, as well as the role of and processes for credentialing, privileging, and accreditation.

Checklists and drills are important for ensuring a safe practice, and the report discusses each of these elements and provides templates and examples. A sample “Office Surgical Safety Checklist” to be used for each procedure, for instance, has sections with preoperative steps (before anesthesia/analgesia, and before incision), intraoperative steps, postoperative steps, and discharge steps. Similar in format to checklists used in the aviation industry, each step has a box to be checked off to verify completion.

Mock drills help ensure that staff are knowledgeable about their roles and coordinated in their response to potential complications, such as vasovagal episodes, respiratory arrest caused by laryngospasm, and local anesthetic toxicity reactions. And, while not the focus of drills, we also must be prepared to manage cervical strictures and stenosis, cervical laceration, uterine perforation, and other complications.

Outpatient surgery guidelines from organizations such as the American College of Surgeons, the Joint Commission, state regulatory agencies, and professional liability insurers, can also be useful resources. With the use of ACOG’s report and other such resources, the set-up and the transition to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting. For most gynecologic surgeons, it will all feel comfortable after only a few procedures.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is with the University of Illinois at Chicago, and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital in Park Ridge, Ill. She is in private practice in Chicago. She is a consultant for Hologic, Bayer HealthCare, Olympus, Caldera Medical, Karl Storz, Medtronic, DYSIS Medical, and Channel Medsystems.

The benefits of integrating in-office hysteroscopy

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice are compelling. Most importantly, patients appreciate the comfort and convenience of having hysteroscopic procedures done in a familiar setting. Patients can generally be in and out of the office in less than 30 minutes for a diagnostic procedure, and in less than 1-2 hours for an operative procedure.

Not only is an in-office approach patient centered and clinically valuable, but it is more efficient and economically favorable for the gynecologic surgeon. Physicians earn higher reimbursement for diagnostic hysteroscopies, as well as many therapeutic and operative hysteroscopies, when these procedures are done in the office rather than when they’re performed in a hospital or an outpatient center.

Transitioning to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting: The setup is relatively simple and does not require an operating suite, just a dedicated exam room. And the need for premedication and local anesthesia can be low, particularly when a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy is employed. For most gynecologic surgeons, the necessary skills and comfort levels fall into place after only a few vaginoscopic procedures.

A vaginoscopic approach avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, significantly decreasing discomfort or pain. Not using these instruments is the only difference between this and traditional hysteroscopy. It is a less invasive approach that is much more tolerable for patients. And for the surgeon, it can be easier and quicker and provides equally good visualization without any impairment in cervical passage.

Described in the literature as far back as the 1950s, vaginoscopy has its roots in the pediatric/adolescent population, where it was used for the removal of foreign bodies and evaluation of the vagina and external cervical os.

More recently, Stefano Bettocchi, MD, and Luigi Selvaggi, MD, in Italy were the first to describe a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy for evaluating the endocervical canal and uterine cavity.

In a series of papers from 1997 to 2004, Dr. Bettocchi and Dr. Selvaggi documented their efforts to improve patient tolerance during diagnostic hysteroscopies. When they used both the speculum and tenaculum in 163 patients, with local anesthesia, 8% reported severe pain, 11% reported moderate pain, and 69% reported mild pain. Only 12% reported no discomfort. With speculum use only, and no anesthesia, in 308 patients, none reported severe pain, 2% reported moderate pain, 32% reported mild pain, and 66% reported no discomfort. When neither instrument was used (again, no anesthesia), patient discomfort was nearly eliminated: In 680 procedures, patients had a 96% no-discomfort rate (J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997 Feb;4[2]:255-8; Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;15[4]:303-8; Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004 Sep;31[3]:641-54, xi).

Since then, research has affirmed the differences in patient tolerance and has shown that there is no significant difference between traditional and vaginoscopic hysteroscopy in the rate of procedure failure (0%-10%).

In my practice, in addition to vaginal or cervical examination and evaluation of the uterine cavity, I utilize a vaginoscopic approach to perform minor therapeutic and operative procedures such as biopsies, polypectomies, tubal occlusion using the Essure system, and removal of lost intrauterine devices. I can assess infertility, trauma, abnormal uterine bleeding, and mesh erosion, and provide pre- and postsurgical evaluations. In all of these cases, I use minimal premedication and only rarely need any local anesthetic and/or sedation.

Instrumentation and technique

There are a variety of hysteroscopes available on the market, from single-channel flexible diagnostic hysteroscopes that are 3 mm to 4 mm in diameter, to “see-and-treat” operative hysteroscopes that are rigid and have various diameters and camera lens angles.

A hysteroscope with a 5.5-mm outer diameter works well for a vaginoscopic approach that avoids cervical dilation. Accessory instrumentation includes semirigid 5 Fr 35-cm–long biopsy forceps, scissors, and alligator forceps.

In timing the procedure, our main goal is a thin uterine lining. This can be achieved by scheduling the procedure during the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle or by using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or a transdermal or transvaginal contraceptive medication.

By far the most important element of pain control and analgesia is the time spent with each patient to thoroughly discuss the experience of hysteroscopy and to set expectations about what she will hear, see, and feel. An unexpected experience can worsen anxiety, which in turn can worsen pain. If everything is as familiar and relaxed as possible, there will be little need for analgesia.

I tell patients in preprocedure counseling that the distention of the uterine walls usually causes some cramping, and that NSAIDs can minimize this cramping. In rare cases, when a patient is very worried about her pain tolerance, I will prescribe diazepam. However, many of my patients opt to do nothing other than take ibuprofen. On a case-by-case basis, you can determine with your patient what type and level of analgesia and preprocedure medication will be best.

Paracervical blocks are an option for some surgical patients, but I advise my patients to move forward without the block and assure them that it can be administered later if needed. Thus far, I’ve never proceeded with a paracervical block. There are other methods and sites for introducing local anesthesia, including intracervical, by injection or topical, or topical intracavitary techniques. Nevertheless, it is unclear from randomized controlled trials whether local anesthesia is effective. Trials of paracervical blocks similarly have had inconsistent outcomes.

I do commonly premedicate patients – mainly nulliparous patients and postmenopausal patients – with misoprostol, which softens the cervix and facilitates an easier entry of the hysteroscope into the cervix.

Published studies on misoprostol administration before hysteroscopy have had mixed results. A Cochrane review from 2015 concluded there is moderate-quality evidence in support of preoperative ripening with the agent, while another meta-analysis also published in 2015 concluded that data are poor and do not support its use. Recently, however, there appear to be more supportive studies demonstrating or suggesting that misoprostol is effective in reducing discomfort.

Patient discomfort is also minimized when there is little manipulation of the hysteroscope. Scopes that are angled (12, 25, or 30 degrees) allow optimal visualization with minimal movement; the scope can be brought to the midline of the uterine cavity and the light cord rotated to the 3:00 and 9:00 o’clock positions to enable visualization of the cornu. A 0-degree scope, on the other hand, must be manipulated quite a bit for the same degree of visualization, potentially increasing patient discomfort.

Prior to hysteroscopy, the cervix and vagina are cleaned with a small-diameter swab dipped in povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate in the case of allergies. One or two 1,000-cc bags of saline inserted into pressure bags are attached to Y-type tubing. (A diagnostic procedure rarely will require two bags.) I spread the labia initially while guiding the scope into the posterior fornix of the vagina. If the leakage of fluid causes inadequate distension of the vaginal walls, I will gently pinch the labia together with gauze.

I then gently pull back the scope and manipulate it posteriorly to visualize the external cervical os anteriorly. The hysteroscope may then be introduced through the cervical os, endocervical canal, and uterine cavity, with care taken so that the instrument does not rub against the cervix or the uterine tissue and cause trauma, pain, and bleeding. The uterus will progressively align with the cervix and vagina, thereby eliminating the need for a tenaculum to straighten the uterine axis.

Fluid monitoring is important, especially during operative hysteroscopy. In my practice, a nurse watches inflow and outflow amounts while I explain what I am doing and visualizing. Some patients like to be able to view the surgery, so I am always ready to tilt the screen accordingly.

The economics

How do you know if office hysteroscopy is right for you? Your own surgical skill and the skills of your staff, who must be trained to handle and sterilize equipment and to consistently assist you, are major factors, as is ensurance of a return on your investment.

One manufacturer contacted for this Master Class lists the price of a complete office tower (light source, camera, and monitor) at approximately $9,700 and the price of a rigid hysteroscope, sheath, and hand instruments at about $6,300. A complete setup for office hysteroscopy, including a standard operative (rigid) hysteroscope, should therefore cost between $15,000 and $17,000. Companies also offer leasing options for about $300-400/month.

Flexible hysteroscopes cost about $6,000 more, which prompts many gynecologic surgeons to focus their investment on a rigid scope that can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-50 or less, for each diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, respectively.

A look at the Medicare Relative Value Units (RVUs) – a key component of the Medicare reimbursement system and a standard for many payers in determining compensation – shows higher reimbursement for quite a few hysteroscopic codes when these procedures are performed in the office.

Total RVUs have three components:

1. Physician work, including time and the technical skill and intensity of effort it takes to perform a service or procedure.

2. Practice expenses, such as rent, equipment and supplies, and nonphysician salaries.

3. Malpractice insurance premiums.

Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

Practice expense (PE) RVUs for services provided in a “facility” (e.g., hospital or outpatient clinic) are often lower than office-based PE RVUs for the same services. Hysteroscopy is no exception. The PE RVU value for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office, for instance, is approximately 5 units, compared with 1.64 units for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in a facility.

Information on hysteroscopic procedures, and their associated RVUs, on geographic practice cost indices and on pricing, can be accessed using Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule lookup tool (www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/overview.aspx).

This tool is useful for calculating returns on investment. According to national payment amounts listed in August, a diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office will earn an average of $315.08 vs. $192.27 for each case performed in the hospital. If you perform 12 such procedures a year, that’s about $3,781 in the office, compared with $2,307 in the hospital.

This difference alone might not be worth an investment of $15,000 or more, but if you anticipate performing additional procedures with higher margins and higher reimbursement, such as 12 thermal endometrial ablations a year in combination with diagnostic hysteroscopy (which, according to the Medicare national fee schedule averages would earn $15,962 in the office vs. $4,971 in the hospital), or 12 Essure tubal occlusions ($22,595 vs. $5,263), the investment will look more favorable.

And if your patients are largely privately insured, your return on investment will occur much more quickly. In metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield is reimbursing in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy at approximately $568, hysteroscopic ablations at $3,844, and Essure tubal occlusions at $3,885.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. You can perform an annual exam while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Our patients, in turn, benefit from increased accessibility, with less time spent away from work or family, as well as more familiarity and comfort and reduced out-of-pocket expenses.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. She is in private practice with Dr. Charles Miller and Dr. Kristen Sasaki at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgical Institute in Chicago. She is a consultant for DySIS Medical, Hologic, and Bayer HealthCare.

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice are compelling. Most importantly, patients appreciate the comfort and convenience of having hysteroscopic procedures done in a familiar setting. Patients can generally be in and out of the office in less than 30 minutes for a diagnostic procedure, and in less than 1-2 hours for an operative procedure.

Not only is an in-office approach patient centered and clinically valuable, but it is more efficient and economically favorable for the gynecologic surgeon. Physicians earn higher reimbursement for diagnostic hysteroscopies, as well as many therapeutic and operative hysteroscopies, when these procedures are done in the office rather than when they’re performed in a hospital or an outpatient center.

Transitioning to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting: The setup is relatively simple and does not require an operating suite, just a dedicated exam room. And the need for premedication and local anesthesia can be low, particularly when a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy is employed. For most gynecologic surgeons, the necessary skills and comfort levels fall into place after only a few vaginoscopic procedures.

A vaginoscopic approach avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, significantly decreasing discomfort or pain. Not using these instruments is the only difference between this and traditional hysteroscopy. It is a less invasive approach that is much more tolerable for patients. And for the surgeon, it can be easier and quicker and provides equally good visualization without any impairment in cervical passage.

Described in the literature as far back as the 1950s, vaginoscopy has its roots in the pediatric/adolescent population, where it was used for the removal of foreign bodies and evaluation of the vagina and external cervical os.

More recently, Stefano Bettocchi, MD, and Luigi Selvaggi, MD, in Italy were the first to describe a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy for evaluating the endocervical canal and uterine cavity.

In a series of papers from 1997 to 2004, Dr. Bettocchi and Dr. Selvaggi documented their efforts to improve patient tolerance during diagnostic hysteroscopies. When they used both the speculum and tenaculum in 163 patients, with local anesthesia, 8% reported severe pain, 11% reported moderate pain, and 69% reported mild pain. Only 12% reported no discomfort. With speculum use only, and no anesthesia, in 308 patients, none reported severe pain, 2% reported moderate pain, 32% reported mild pain, and 66% reported no discomfort. When neither instrument was used (again, no anesthesia), patient discomfort was nearly eliminated: In 680 procedures, patients had a 96% no-discomfort rate (J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997 Feb;4[2]:255-8; Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;15[4]:303-8; Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004 Sep;31[3]:641-54, xi).

Since then, research has affirmed the differences in patient tolerance and has shown that there is no significant difference between traditional and vaginoscopic hysteroscopy in the rate of procedure failure (0%-10%).

In my practice, in addition to vaginal or cervical examination and evaluation of the uterine cavity, I utilize a vaginoscopic approach to perform minor therapeutic and operative procedures such as biopsies, polypectomies, tubal occlusion using the Essure system, and removal of lost intrauterine devices. I can assess infertility, trauma, abnormal uterine bleeding, and mesh erosion, and provide pre- and postsurgical evaluations. In all of these cases, I use minimal premedication and only rarely need any local anesthetic and/or sedation.

Instrumentation and technique

There are a variety of hysteroscopes available on the market, from single-channel flexible diagnostic hysteroscopes that are 3 mm to 4 mm in diameter, to “see-and-treat” operative hysteroscopes that are rigid and have various diameters and camera lens angles.

A hysteroscope with a 5.5-mm outer diameter works well for a vaginoscopic approach that avoids cervical dilation. Accessory instrumentation includes semirigid 5 Fr 35-cm–long biopsy forceps, scissors, and alligator forceps.

In timing the procedure, our main goal is a thin uterine lining. This can be achieved by scheduling the procedure during the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle or by using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or a transdermal or transvaginal contraceptive medication.

By far the most important element of pain control and analgesia is the time spent with each patient to thoroughly discuss the experience of hysteroscopy and to set expectations about what she will hear, see, and feel. An unexpected experience can worsen anxiety, which in turn can worsen pain. If everything is as familiar and relaxed as possible, there will be little need for analgesia.

I tell patients in preprocedure counseling that the distention of the uterine walls usually causes some cramping, and that NSAIDs can minimize this cramping. In rare cases, when a patient is very worried about her pain tolerance, I will prescribe diazepam. However, many of my patients opt to do nothing other than take ibuprofen. On a case-by-case basis, you can determine with your patient what type and level of analgesia and preprocedure medication will be best.

Paracervical blocks are an option for some surgical patients, but I advise my patients to move forward without the block and assure them that it can be administered later if needed. Thus far, I’ve never proceeded with a paracervical block. There are other methods and sites for introducing local anesthesia, including intracervical, by injection or topical, or topical intracavitary techniques. Nevertheless, it is unclear from randomized controlled trials whether local anesthesia is effective. Trials of paracervical blocks similarly have had inconsistent outcomes.

I do commonly premedicate patients – mainly nulliparous patients and postmenopausal patients – with misoprostol, which softens the cervix and facilitates an easier entry of the hysteroscope into the cervix.

Published studies on misoprostol administration before hysteroscopy have had mixed results. A Cochrane review from 2015 concluded there is moderate-quality evidence in support of preoperative ripening with the agent, while another meta-analysis also published in 2015 concluded that data are poor and do not support its use. Recently, however, there appear to be more supportive studies demonstrating or suggesting that misoprostol is effective in reducing discomfort.

Patient discomfort is also minimized when there is little manipulation of the hysteroscope. Scopes that are angled (12, 25, or 30 degrees) allow optimal visualization with minimal movement; the scope can be brought to the midline of the uterine cavity and the light cord rotated to the 3:00 and 9:00 o’clock positions to enable visualization of the cornu. A 0-degree scope, on the other hand, must be manipulated quite a bit for the same degree of visualization, potentially increasing patient discomfort.

Prior to hysteroscopy, the cervix and vagina are cleaned with a small-diameter swab dipped in povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate in the case of allergies. One or two 1,000-cc bags of saline inserted into pressure bags are attached to Y-type tubing. (A diagnostic procedure rarely will require two bags.) I spread the labia initially while guiding the scope into the posterior fornix of the vagina. If the leakage of fluid causes inadequate distension of the vaginal walls, I will gently pinch the labia together with gauze.

I then gently pull back the scope and manipulate it posteriorly to visualize the external cervical os anteriorly. The hysteroscope may then be introduced through the cervical os, endocervical canal, and uterine cavity, with care taken so that the instrument does not rub against the cervix or the uterine tissue and cause trauma, pain, and bleeding. The uterus will progressively align with the cervix and vagina, thereby eliminating the need for a tenaculum to straighten the uterine axis.

Fluid monitoring is important, especially during operative hysteroscopy. In my practice, a nurse watches inflow and outflow amounts while I explain what I am doing and visualizing. Some patients like to be able to view the surgery, so I am always ready to tilt the screen accordingly.

The economics

How do you know if office hysteroscopy is right for you? Your own surgical skill and the skills of your staff, who must be trained to handle and sterilize equipment and to consistently assist you, are major factors, as is ensurance of a return on your investment.

One manufacturer contacted for this Master Class lists the price of a complete office tower (light source, camera, and monitor) at approximately $9,700 and the price of a rigid hysteroscope, sheath, and hand instruments at about $6,300. A complete setup for office hysteroscopy, including a standard operative (rigid) hysteroscope, should therefore cost between $15,000 and $17,000. Companies also offer leasing options for about $300-400/month.

Flexible hysteroscopes cost about $6,000 more, which prompts many gynecologic surgeons to focus their investment on a rigid scope that can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-50 or less, for each diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, respectively.

A look at the Medicare Relative Value Units (RVUs) – a key component of the Medicare reimbursement system and a standard for many payers in determining compensation – shows higher reimbursement for quite a few hysteroscopic codes when these procedures are performed in the office.

Total RVUs have three components:

1. Physician work, including time and the technical skill and intensity of effort it takes to perform a service or procedure.

2. Practice expenses, such as rent, equipment and supplies, and nonphysician salaries.

3. Malpractice insurance premiums.

Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

Practice expense (PE) RVUs for services provided in a “facility” (e.g., hospital or outpatient clinic) are often lower than office-based PE RVUs for the same services. Hysteroscopy is no exception. The PE RVU value for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office, for instance, is approximately 5 units, compared with 1.64 units for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in a facility.

Information on hysteroscopic procedures, and their associated RVUs, on geographic practice cost indices and on pricing, can be accessed using Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule lookup tool (www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/overview.aspx).

This tool is useful for calculating returns on investment. According to national payment amounts listed in August, a diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office will earn an average of $315.08 vs. $192.27 for each case performed in the hospital. If you perform 12 such procedures a year, that’s about $3,781 in the office, compared with $2,307 in the hospital.

This difference alone might not be worth an investment of $15,000 or more, but if you anticipate performing additional procedures with higher margins and higher reimbursement, such as 12 thermal endometrial ablations a year in combination with diagnostic hysteroscopy (which, according to the Medicare national fee schedule averages would earn $15,962 in the office vs. $4,971 in the hospital), or 12 Essure tubal occlusions ($22,595 vs. $5,263), the investment will look more favorable.

And if your patients are largely privately insured, your return on investment will occur much more quickly. In metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield is reimbursing in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy at approximately $568, hysteroscopic ablations at $3,844, and Essure tubal occlusions at $3,885.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. You can perform an annual exam while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Our patients, in turn, benefit from increased accessibility, with less time spent away from work or family, as well as more familiarity and comfort and reduced out-of-pocket expenses.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. She is in private practice with Dr. Charles Miller and Dr. Kristen Sasaki at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgical Institute in Chicago. She is a consultant for DySIS Medical, Hologic, and Bayer HealthCare.

The benefits of integrating hysteroscopy into office practice are compelling. Most importantly, patients appreciate the comfort and convenience of having hysteroscopic procedures done in a familiar setting. Patients can generally be in and out of the office in less than 30 minutes for a diagnostic procedure, and in less than 1-2 hours for an operative procedure.

Not only is an in-office approach patient centered and clinically valuable, but it is more efficient and economically favorable for the gynecologic surgeon. Physicians earn higher reimbursement for diagnostic hysteroscopies, as well as many therapeutic and operative hysteroscopies, when these procedures are done in the office rather than when they’re performed in a hospital or an outpatient center.

Transitioning to in-office hysteroscopy need not be daunting: The setup is relatively simple and does not require an operating suite, just a dedicated exam room. And the need for premedication and local anesthesia can be low, particularly when a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy is employed. For most gynecologic surgeons, the necessary skills and comfort levels fall into place after only a few vaginoscopic procedures.

A vaginoscopic approach avoids the use of a vaginal speculum or cervical tenaculum, significantly decreasing discomfort or pain. Not using these instruments is the only difference between this and traditional hysteroscopy. It is a less invasive approach that is much more tolerable for patients. And for the surgeon, it can be easier and quicker and provides equally good visualization without any impairment in cervical passage.

Described in the literature as far back as the 1950s, vaginoscopy has its roots in the pediatric/adolescent population, where it was used for the removal of foreign bodies and evaluation of the vagina and external cervical os.

More recently, Stefano Bettocchi, MD, and Luigi Selvaggi, MD, in Italy were the first to describe a vaginoscopic approach to hysteroscopy for evaluating the endocervical canal and uterine cavity.

In a series of papers from 1997 to 2004, Dr. Bettocchi and Dr. Selvaggi documented their efforts to improve patient tolerance during diagnostic hysteroscopies. When they used both the speculum and tenaculum in 163 patients, with local anesthesia, 8% reported severe pain, 11% reported moderate pain, and 69% reported mild pain. Only 12% reported no discomfort. With speculum use only, and no anesthesia, in 308 patients, none reported severe pain, 2% reported moderate pain, 32% reported mild pain, and 66% reported no discomfort. When neither instrument was used (again, no anesthesia), patient discomfort was nearly eliminated: In 680 procedures, patients had a 96% no-discomfort rate (J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1997 Feb;4[2]:255-8; Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2003 Aug;15[4]:303-8; Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2004 Sep;31[3]:641-54, xi).

Since then, research has affirmed the differences in patient tolerance and has shown that there is no significant difference between traditional and vaginoscopic hysteroscopy in the rate of procedure failure (0%-10%).

In my practice, in addition to vaginal or cervical examination and evaluation of the uterine cavity, I utilize a vaginoscopic approach to perform minor therapeutic and operative procedures such as biopsies, polypectomies, tubal occlusion using the Essure system, and removal of lost intrauterine devices. I can assess infertility, trauma, abnormal uterine bleeding, and mesh erosion, and provide pre- and postsurgical evaluations. In all of these cases, I use minimal premedication and only rarely need any local anesthetic and/or sedation.

Instrumentation and technique

There are a variety of hysteroscopes available on the market, from single-channel flexible diagnostic hysteroscopes that are 3 mm to 4 mm in diameter, to “see-and-treat” operative hysteroscopes that are rigid and have various diameters and camera lens angles.

A hysteroscope with a 5.5-mm outer diameter works well for a vaginoscopic approach that avoids cervical dilation. Accessory instrumentation includes semirigid 5 Fr 35-cm–long biopsy forceps, scissors, and alligator forceps.

In timing the procedure, our main goal is a thin uterine lining. This can be achieved by scheduling the procedure during the early proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle or by using a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist or a transdermal or transvaginal contraceptive medication.

By far the most important element of pain control and analgesia is the time spent with each patient to thoroughly discuss the experience of hysteroscopy and to set expectations about what she will hear, see, and feel. An unexpected experience can worsen anxiety, which in turn can worsen pain. If everything is as familiar and relaxed as possible, there will be little need for analgesia.

I tell patients in preprocedure counseling that the distention of the uterine walls usually causes some cramping, and that NSAIDs can minimize this cramping. In rare cases, when a patient is very worried about her pain tolerance, I will prescribe diazepam. However, many of my patients opt to do nothing other than take ibuprofen. On a case-by-case basis, you can determine with your patient what type and level of analgesia and preprocedure medication will be best.

Paracervical blocks are an option for some surgical patients, but I advise my patients to move forward without the block and assure them that it can be administered later if needed. Thus far, I’ve never proceeded with a paracervical block. There are other methods and sites for introducing local anesthesia, including intracervical, by injection or topical, or topical intracavitary techniques. Nevertheless, it is unclear from randomized controlled trials whether local anesthesia is effective. Trials of paracervical blocks similarly have had inconsistent outcomes.

I do commonly premedicate patients – mainly nulliparous patients and postmenopausal patients – with misoprostol, which softens the cervix and facilitates an easier entry of the hysteroscope into the cervix.

Published studies on misoprostol administration before hysteroscopy have had mixed results. A Cochrane review from 2015 concluded there is moderate-quality evidence in support of preoperative ripening with the agent, while another meta-analysis also published in 2015 concluded that data are poor and do not support its use. Recently, however, there appear to be more supportive studies demonstrating or suggesting that misoprostol is effective in reducing discomfort.

Patient discomfort is also minimized when there is little manipulation of the hysteroscope. Scopes that are angled (12, 25, or 30 degrees) allow optimal visualization with minimal movement; the scope can be brought to the midline of the uterine cavity and the light cord rotated to the 3:00 and 9:00 o’clock positions to enable visualization of the cornu. A 0-degree scope, on the other hand, must be manipulated quite a bit for the same degree of visualization, potentially increasing patient discomfort.

Prior to hysteroscopy, the cervix and vagina are cleaned with a small-diameter swab dipped in povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate in the case of allergies. One or two 1,000-cc bags of saline inserted into pressure bags are attached to Y-type tubing. (A diagnostic procedure rarely will require two bags.) I spread the labia initially while guiding the scope into the posterior fornix of the vagina. If the leakage of fluid causes inadequate distension of the vaginal walls, I will gently pinch the labia together with gauze.

I then gently pull back the scope and manipulate it posteriorly to visualize the external cervical os anteriorly. The hysteroscope may then be introduced through the cervical os, endocervical canal, and uterine cavity, with care taken so that the instrument does not rub against the cervix or the uterine tissue and cause trauma, pain, and bleeding. The uterus will progressively align with the cervix and vagina, thereby eliminating the need for a tenaculum to straighten the uterine axis.

Fluid monitoring is important, especially during operative hysteroscopy. In my practice, a nurse watches inflow and outflow amounts while I explain what I am doing and visualizing. Some patients like to be able to view the surgery, so I am always ready to tilt the screen accordingly.

The economics

How do you know if office hysteroscopy is right for you? Your own surgical skill and the skills of your staff, who must be trained to handle and sterilize equipment and to consistently assist you, are major factors, as is ensurance of a return on your investment.

One manufacturer contacted for this Master Class lists the price of a complete office tower (light source, camera, and monitor) at approximately $9,700 and the price of a rigid hysteroscope, sheath, and hand instruments at about $6,300. A complete setup for office hysteroscopy, including a standard operative (rigid) hysteroscope, should therefore cost between $15,000 and $17,000. Companies also offer leasing options for about $300-400/month.

Flexible hysteroscopes cost about $6,000 more, which prompts many gynecologic surgeons to focus their investment on a rigid scope that can be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. Disposables cost $10 or less, and $40-50 or less, for each diagnostic and operative hysteroscopy, respectively.

A look at the Medicare Relative Value Units (RVUs) – a key component of the Medicare reimbursement system and a standard for many payers in determining compensation – shows higher reimbursement for quite a few hysteroscopic codes when these procedures are performed in the office.

Total RVUs have three components:

1. Physician work, including time and the technical skill and intensity of effort it takes to perform a service or procedure.

2. Practice expenses, such as rent, equipment and supplies, and nonphysician salaries.

3. Malpractice insurance premiums.

Each component is multiplied by a factor that accounts for geographic cost variations, and each total RVU is multiplied by a dollar amount known as the conversion factor.

Practice expense (PE) RVUs for services provided in a “facility” (e.g., hospital or outpatient clinic) are often lower than office-based PE RVUs for the same services. Hysteroscopy is no exception. The PE RVU value for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office, for instance, is approximately 5 units, compared with 1.64 units for diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in a facility.

Information on hysteroscopic procedures, and their associated RVUs, on geographic practice cost indices and on pricing, can be accessed using Medicare’s Physician Fee Schedule lookup tool (www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/overview.aspx).

This tool is useful for calculating returns on investment. According to national payment amounts listed in August, a diagnostic hysteroscopy performed in the office will earn an average of $315.08 vs. $192.27 for each case performed in the hospital. If you perform 12 such procedures a year, that’s about $3,781 in the office, compared with $2,307 in the hospital.

This difference alone might not be worth an investment of $15,000 or more, but if you anticipate performing additional procedures with higher margins and higher reimbursement, such as 12 thermal endometrial ablations a year in combination with diagnostic hysteroscopy (which, according to the Medicare national fee schedule averages would earn $15,962 in the office vs. $4,971 in the hospital), or 12 Essure tubal occlusions ($22,595 vs. $5,263), the investment will look more favorable.

And if your patients are largely privately insured, your return on investment will occur much more quickly. In metropolitan Chicago, Blue Cross Blue Shield is reimbursing in-office diagnostic hysteroscopy at approximately $568, hysteroscopic ablations at $3,844, and Essure tubal occlusions at $3,885.

In addition to reimbursement levels, it’s important to consider the efficiencies of in-office hysteroscopy. You can perform an annual exam while the assistant sets up the room and greets each patient, for instance, or see another established patient while the assistant discharges your patient and turns the room over. Our patients, in turn, benefit from increased accessibility, with less time spent away from work or family, as well as more familiarity and comfort and reduced out-of-pocket expenses.

Dr. Cholkeri-Singh is clinical assistant professor at the University of Illinois in Chicago and is director of gynecologic surgical education and associate director of minimally invasive gynecology at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital. She is in private practice with Dr. Charles Miller and Dr. Kristen Sasaki at the Advanced Gynecologic Surgical Institute in Chicago. She is a consultant for DySIS Medical, Hologic, and Bayer HealthCare.

Minilaparoscopy: The Best of Both Worlds

The clinical advantages of laparoscopy over laparotomy have been well established over the last several years. As the acceptance and use of laparoscopic approaches have increased among gynecologic surgeons, attention to cosmesis has also evolved.

Laparoscopy has been appealing for its cosmetic benefits as well as reductions in complications and recovery times. Women not only want to resume their normal activities sooner; they also want to take advantage of the smaller incisions that laparoscopy entails, as these incisions do not alter abdominal wall appearance as significantly as do laparotomy incisions.

Still, depending on an individual’s body mass index and wound healing, scars can be disturbing for patients. Some women who have had more than one laparoscopic surgery requiring different port placements have jokingly spoken about "connecting the dots," but such comments reflect concern about aesthetics and should be taken seriously. Although we have improved surgical outcomes with laparoscopy and reduced the size of the surgical scar, we can still create disfigured abdomens.

Last year, the AAGL Fellowship in Minimally Invasive Gynecologic Surgery at Newton-Wellesley (Mass.) Hospital published an article about a survey of women and their preferred abdominal incision choices, based solely on cosmesis (J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:640-3). The survey participants were shown three photographs of incisions that were commonly performed at their institution and among several Boston-area gynecologic surgeons, and were asked to rank the incisions in order of preference.

The photograph depicting a single incision or single-site laparoscopy showed a vertical 25-mm incision. The robotic laparoscopy photo showed five incisions: umbilical and right midabdomen (paraumbilical) incisions of 12-mm length, and 8-mm incisions in the right lower quadrant, left lower quadrant, and left midabdomen. The incision configuration in the photo of a conventional four-port laparoscopy consisted of a 10-mm incision in the right lower quadrant and 5-mm incisions in the umbilicus, left lower quadrant, and suprapubic area.

The conventional laparoscopy incisions were most preferred by approximately 56% of the 241 women who completed the survey, whereas preference for a single incision was approximately 41% and for robotic surgery was 2.5%.

Granted, there are variable configurations and incision sizes for each of the laparoscopic techniques, and further strides are being made to make the approaches more cosmetically acceptable. Experienced gynecologic surgeons are developing techniques to minimize the number of ports used robotically, for instance, and smaller incision sizes for robotic laparoscopy are anticipated.

In any case, the overarching lesson from this survey is that aesthetics is of value to many women and should be an important consideration for us as treating physicians.

Miniaturization

The use of mini- or microlaparoscopic instrumentation enables us to address aesthetic concerns and take the issue of cosmesis to the next level, as well as to further minimizing trauma. Although conventional laparoscopy involves instruments of 5-mm diameter or larger, the term "minilaparoscopy" usually refers to the use of instruments greater than 2 mm up to less than 5 mm in diameter, and "microlaparoscopy" involves instrumentation of 2 mm or less in diameter.

In gynecology, minilaparoscopy has been utilized diagnostically since the mid-1990s to perform conscious pain mapping with local anesthesia. With a 2.5 mm–diameter scope and 3 mm–diameter trocars, surgeons have used a blunt probe to map trigger sites with the patient’s assistance and response, and to aid in identifying pelvic disease suspected of causing pain (Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2008;100:94-8).

The diagnostic accuracy of the mini- or microlaparoscope has been reported in various scenarios (including cases of endometriosis and adhesive disease) to be comparable to that of the 10-mm scope that is used in conventional laparoscopy.

In one small study, investigators compared the diagnostic accuracy of 2-mm and 10-mm laparoscopes, with two physicians independently reporting findings to a third person (Fertil. Steril. 1997;67:952-4). Although they had a small sample size, the researchers observed no significant differences between the two laparoscopes or the two physicians. (Scores for endometriosis and adnexal adhesions, for instance, did not differ in any significant way.) This suggested that the diagnostic accuracy achieved with the microlaparoscope was comparable to that of the standard 10-mm laparoscope.

Another study in which 87 consecutive women underwent microlaparoscopic evaluation for chronic pelvic pain similarly found that microlaparoscopy provides comparable efficacy for diagnosing endometriosis and evaluating for the presence of occlusive salpingitis isthmica nodosa. Evaluation through a 2-mm port affords "an excellent minimally invasive view of the pelvis," the investigator wrote (JSLS 2005;9:431-3).

Most of the literature for minilaparoscopy, however, has evolved from the nongynecologic specialties, particularly general surgery. It has been well documented that minilaparoscopy is safe for splenic and liver biopsies, as well as helpful in reducing port sizes and hernias when utilized in cholecystectomies and colorectal resections.

Most recently, the authors of a literature review spanning the last 30 years concluded that minilaparoscopy has been shown in almost all urologic indications to be feasible and safe, with better cosmetic results and reduced postoperative pain (Arch. Esp. Urol. 2012;65:366-83).

Collectively, these studies provide us with a solid body of evidence on the safety, feasibility, and benefits of minilaparoscopy. The findings noted in the surgical literature for minilaparoscopy include operative times, morbidity, and hospital lengths of stay that are comparable to those of conventional laparoscopy; improved cosmesis; a decrease in postoperative pain; and reductions in port-site complications such as bleeding, infection, and herniation.

Surpassing SIL

Single-incision laparoscopy (also known as "scarless" surgery, with the umbilicus viewed as a natural scar) was developed to improve cosmesis. An incision approximately 25 mm in size at the umbilicus allows a scope and two or three instruments to pass into the abdominal cavity.

A main challenge – and a limitation for many surgeons – is the lack of triangulation because of the parallel entry. Instruments are crossed, which is counterintuitive to conventional laparoscopic training, and hands and instruments can clash, which limits the use of instrumentation.

An array of curved and EndoWrist instruments (with flexible joints at the tips) was developed to help ease the technical difficulties of single-port surgery. Many advanced endoscopic surgeons have performed simple to complex single-incision procedures with low complication rates and with operative times and rates of blood loss that are comparable with those of conventional laparoscopy. One advantage to single-incision surgery is that the incision size allows the removal of larger tissue that has been resected from the abdomen.

A recent study in the Netherlands suggests that single-incision surgery may not be all that more difficult to learn (Surg. Endosc. 2012;26:1231-7). The simulation study looked at the performance/learning curves of 20 medical interns (none with laparoscopic experience) who were randomly assigned to perform single-incision or conventional laparoscopy. Each participant practiced each task 11 times. There were no significant differences between the two groups in terms of error or time in performing the tasks, and participants improved significantly in both laparoscopy settings.

There are still many concerns, however, that single-incision laparoscopy is indeed more technically challenging, and that a sizable learning curve for the single-incision approach –in addition to the learning curve of conventional laparoscopy – does exist. Without surgical volume and patience, this technique may be a struggle for many to adapt and teach.

Moreover, as shown in the study at Newton-Wellesley Hospital, the scars remain a concern for many women. The umbilicus is the easiest place to try to "hide" an incision and scar when the incision is made at its base, but a 2-1/2 cm incision can be difficult to hide in a shallow umbilicus; for some women, the larger single scar becomes a focal point of their abdomen and, thus, disfiguring.

Our Experience

With minilaparoscopy, we can maintain triangulation and employ the fundamental principles of conventional laparoscopy with greater technical ease. The approach also has the potential to reduce the risk of incision-site hernias and the incidence of wound complications.

The following drawbacks to minilaparoscopy have been cited:

• A smaller view of the operative field.

• Less tensile strength of the instruments.

• Electrosurgery instruments that are limited to small vessels/pathology.

• Difficulty with large-tissue extraction.

There are solutions to each of these challenges, many of which involve hybrid approaches that incorporate single-incision or conventional laparoscopic ports at the umbilicus to facilitate electrosurgery, tissue extraction, and visualization while maintaining cosmesis. The solutions include the following:

• Better optics. Significant strides have been made in the area of optics, and newer minilaparoscopes (Figure 1) have better resolution and optical clarity than does the previous generation of miniature scopes. We have found that we can zoom the image and reduce light to improve visualization and maximize the operative field.

• Improved instrument strength. As with miniaturized laparoscopes, a wide array of durable instrumentation (Figures 2 and 3) is now available. We employ instruments that are 2.3-3.3 mm in diameter and up to 36 cm in length, ports that are 3.5 mm in diameter and 10-15 cm in length, and scopes that are 2.9-3.3 mm in diameter and up to 25 cm in length.

For skin incisions, a 14-gauge needle is used instead of a scalpel to avoid an incision that is too large and would allow easy slippage of the port. On the 2.3-mm disposable instruments, the tip itself is a 13-gauge needle that is utilized to incise the skin and enter the abdominal cavity. (See Figure 4.) Wounds are not sutured closed, but are merely reapproximated with Steri-Strips at the end of the procedure.

• More versatile electrosurgery instruments. We utilize reusable and disposable bipolar coagulating forceps, as well as reusable instruments with monopolar electrosurgical capability, including dissecting and grasping forceps, scissors, hook, and spatula. For example, when we excise endometriosis, we will utilize a sharp grasping instrument to elevate the lesion away from vital structures, as well as monopolar scissors to excise the disease. Needle holders and knot pushers are sturdy for suturing, and a suction tip is also available in miniaturized form.

In procedures in which the vessel-sealing capacity of a 3-mm energy source is not sufficient, a 5-mm port can be placed at the umbilicus so that a standard 5-mm energy source can be utilized to improve or maintain hemostasis.

• Extraction of large tissues. For tissue extraction requiring an incision larger than 5 mm, a 10- to 12-mm trocar can be placed at the umbilicus for the possible use of an endoscopic specimen bag. We dilate the umbilicus with Hegar dilators to a size 16 to ease the extraction of tissue, if necessary, or for the placement of a laparoscopic morcellator.

Recently, however, we have been able to perform minilaparoscopic hysterectomies with the use of three 3-mm ports, a minilaparoscope, and other miniaturized instrumentation. Specifically, we utilize the 3-mm PKS MoLly forceps by Olympus Gyrus (Figure 5) to coagulate and monopolar scissors to transect the pedicles. A colpotomy is completed with the scissors, and the specimen is delivered through the colpotomy incision. The colpotomy incision is reapproximated with 0-PDS suture on CT-1–sized needles. The suture is backloaded through the miniport and is introduced into the abdomen without difficulty. The incision is sutured; the needle is parked in the upper abdominal wall, and is then cut free. The suture is then pulled through the port for extracorporeal knot tying. The needle is retrieved and pulled through the incision with the removal of the port, and is now ready for loading another suture.

A minilaparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy can be performed in a similar fashion. For tissue extraction, we perform transcervical morcellation. We have found that the morcellators with extra-long shafts (such as the Storz 12-mm extra-long Rotocut or Gynecare Morcellex) work best for transcervical morcellation. Once uterine amputation is completed, the cervical stump is dilated with cervical dilators to allow for the morcellator tip to advance through the cervix and into the pelvic cavity transvaginally. Under direct visualization and with the assistance of a laparoscopic grasper, the specimen is morcellated. Similarly, an endoscopic specimen bag can also be placed transcervically to retrieve specimens that are not to undergo morcellation.