User login

Immediate skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section improves outcomes for parent, newborn

Birth parents are typically separated from their newborns following a cesarean section. However, a recent study published in the journal Nursing Open suggests immediate skin-to-skin contact may accelerate uterine contractions, reduce maternal blood loss, reduce newborn crying, improve patient satisfaction and comfort, and increase the rate of breastfeeding.

“[O]ur study contributes to scientific knowledge with key information to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality rates in mothers who have undergone scheduled cesarean sections,” José Miguel Pérez-Jiménez, MD, of the faculty of nursing, physiotherapy, and podiatry at Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, University of Sevilla, Spain, and colleagues wrote in their study. It promotes greater stability in the mothers by reducing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, making it better to not separate mother and child in the first hours after this surgery, he said.

Dr. Pérez-Jiménez and colleagues evaluated 83 women who underwent a scheduled cesarean section in an unblinded, randomized controlled trial. The women were randomized to receive skin-to-skin contact in the operating room that continued in the postpartum unit, or the normal protocol after cesarean section that consisted of having the mother transferred to the postanesthesia recovery room while the newborn was sent to a maternity room with a parent or companion. Researchers assessed variables such as plasma hemoglobin, uterine contractions, breastfeeding, and postoperative pain, as well as subjective measures such as maternal satisfaction, comfort, previous cesarean section experience, and newborn crying.

Women who received usual care following cesarean section were more likely to have uterine contractions at the umbilical level compared with the skin-to-skin contact group (70% vs. 3%; P ≤ .0001), while the skin-to-skin group was more likely to have uterine contractions at the infraumbilical level (92.5% vs. 22.5%; P ≤ .0001). There was a statistically significant decrease in predischarge hemoglobin in the control group compared with the skin-to-skin group (10.522 vs. 11.075 g/dL; P ≤ .017); the level of hemoglobin reduction favored the skin-to-skin group (1.01 vs. 2.265 g/dL; P ≤ .0001). Women in the skin-to-skin group were more likely to report mild pain on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) after being transferred to the recovery room (1.48 vs. 6.23 points; P ≤ .0001) and being transferred to a maternity room or room in the postpartum unit (0.60 vs. 5.23 points; P ≤ .0001). Breastfeeding at birth was significantly higher among patients with immediate skin-to-skin contact compared with the control group (92.5% vs. 32.5%; P ≤ .0001), and continued at 1 month after birth (92.5% vs. 12.5%; P ≤ .0001). Newborns of mothers in the skin-to-skin group were significantly less likely to cry compared with newborns in the control group (90% vs. 55%; P ≤ .001).

When asked to rate their satisfaction on a 10-point Likert scale, women in the skin-to-skin contact group rated their experience significantly higher than did the control group (9.98 vs. 6.5; P ≤ .0001), and all women who had previously had a cesarean section in the skin-to-skin group (30%) rated their experience at 10 points compared with their previous cesarean section without skin-to-skin contact.

Implementing skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section

Betsy M. Collins, MD, MPH, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that while some of the findings were largely unsurprising and “confirmed a lot of the things that we already know about skin-to-skin [contact],” one major finding was the “stark difference” in the percentage of new birth parents who started breastfeeding after skin-to-skin contact and were still breastfeeding at 1 month postpartum compared with birth parents in the control group. She was not involved with the study and noted that the results complement recommendations from the World Health Organization on starting breastfeeding within the first hour after birth and continuing breastfeeding through the first 6 months of life.

“That was likely one of the greatest take-home points from the study ... that early skin-to-skin really promoted initiation of breastfeeding,” Dr. Collins said.

Two reasons why skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section isn’t regularly provided is that it can be difficult for personnel and safety reasons to have an extra nurse to continue monitoring the health of the newborn in the operating room, and there is a lack of culture supporting of skin-to-skin contact in the OR, Dr. Collins explained.

“Just like anything else, if it’s built into your standard operating procedure, then you have everything set up in place to do that initial assessment of the infant and then get the baby skin-to-skin as quickly as possible,” she said. If it’s your standard operating procedure to not provide skin-to-skin contact, she said, then there is a little bit more inertia to overcome to start providing it as a standard procedure.

At her center, Dr. Collins said skin-to-skin contact is initiated as soon as possible after birth, even in the operating room. The steps to implementing that policy involved getting the anesthesiology department on board with supporting the policy in the OR and training the circulating nursing staff to ensure a that nurse is available to monitor the newborn.

“I think the most important thing to know is that it’s absolutely doable and that you just have to have a champion just like any other quality initiative,” she said. One of the best ways to do that is to have the patients themselves request it, she noted, compared with its being requested by a physician or nurse.

“I think some patients are disappointed when they have to undergo cesarean delivery or feel like they’re missing out if they can’t have a vaginal delivery,” Dr. Collins said. Immediate skin-to-skin contact is “very good for not only physiology, as we read about in this paper – all the things they said about the benefits of skin-to-skin [contact] are true – but it’s really good for mental health. That bonding begins right away.”

As a birth parent, being separated from your newborn for several hours after a cesarean section, on the other hand, can be “pretty devastating,” Dr. Collins said.

“I think this is something that, once it becomes a standard of care, it will be expected that most hospitals should be doing this,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Collins report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Birth parents are typically separated from their newborns following a cesarean section. However, a recent study published in the journal Nursing Open suggests immediate skin-to-skin contact may accelerate uterine contractions, reduce maternal blood loss, reduce newborn crying, improve patient satisfaction and comfort, and increase the rate of breastfeeding.

“[O]ur study contributes to scientific knowledge with key information to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality rates in mothers who have undergone scheduled cesarean sections,” José Miguel Pérez-Jiménez, MD, of the faculty of nursing, physiotherapy, and podiatry at Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, University of Sevilla, Spain, and colleagues wrote in their study. It promotes greater stability in the mothers by reducing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, making it better to not separate mother and child in the first hours after this surgery, he said.

Dr. Pérez-Jiménez and colleagues evaluated 83 women who underwent a scheduled cesarean section in an unblinded, randomized controlled trial. The women were randomized to receive skin-to-skin contact in the operating room that continued in the postpartum unit, or the normal protocol after cesarean section that consisted of having the mother transferred to the postanesthesia recovery room while the newborn was sent to a maternity room with a parent or companion. Researchers assessed variables such as plasma hemoglobin, uterine contractions, breastfeeding, and postoperative pain, as well as subjective measures such as maternal satisfaction, comfort, previous cesarean section experience, and newborn crying.

Women who received usual care following cesarean section were more likely to have uterine contractions at the umbilical level compared with the skin-to-skin contact group (70% vs. 3%; P ≤ .0001), while the skin-to-skin group was more likely to have uterine contractions at the infraumbilical level (92.5% vs. 22.5%; P ≤ .0001). There was a statistically significant decrease in predischarge hemoglobin in the control group compared with the skin-to-skin group (10.522 vs. 11.075 g/dL; P ≤ .017); the level of hemoglobin reduction favored the skin-to-skin group (1.01 vs. 2.265 g/dL; P ≤ .0001). Women in the skin-to-skin group were more likely to report mild pain on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) after being transferred to the recovery room (1.48 vs. 6.23 points; P ≤ .0001) and being transferred to a maternity room or room in the postpartum unit (0.60 vs. 5.23 points; P ≤ .0001). Breastfeeding at birth was significantly higher among patients with immediate skin-to-skin contact compared with the control group (92.5% vs. 32.5%; P ≤ .0001), and continued at 1 month after birth (92.5% vs. 12.5%; P ≤ .0001). Newborns of mothers in the skin-to-skin group were significantly less likely to cry compared with newborns in the control group (90% vs. 55%; P ≤ .001).

When asked to rate their satisfaction on a 10-point Likert scale, women in the skin-to-skin contact group rated their experience significantly higher than did the control group (9.98 vs. 6.5; P ≤ .0001), and all women who had previously had a cesarean section in the skin-to-skin group (30%) rated their experience at 10 points compared with their previous cesarean section without skin-to-skin contact.

Implementing skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section

Betsy M. Collins, MD, MPH, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that while some of the findings were largely unsurprising and “confirmed a lot of the things that we already know about skin-to-skin [contact],” one major finding was the “stark difference” in the percentage of new birth parents who started breastfeeding after skin-to-skin contact and were still breastfeeding at 1 month postpartum compared with birth parents in the control group. She was not involved with the study and noted that the results complement recommendations from the World Health Organization on starting breastfeeding within the first hour after birth and continuing breastfeeding through the first 6 months of life.

“That was likely one of the greatest take-home points from the study ... that early skin-to-skin really promoted initiation of breastfeeding,” Dr. Collins said.

Two reasons why skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section isn’t regularly provided is that it can be difficult for personnel and safety reasons to have an extra nurse to continue monitoring the health of the newborn in the operating room, and there is a lack of culture supporting of skin-to-skin contact in the OR, Dr. Collins explained.

“Just like anything else, if it’s built into your standard operating procedure, then you have everything set up in place to do that initial assessment of the infant and then get the baby skin-to-skin as quickly as possible,” she said. If it’s your standard operating procedure to not provide skin-to-skin contact, she said, then there is a little bit more inertia to overcome to start providing it as a standard procedure.

At her center, Dr. Collins said skin-to-skin contact is initiated as soon as possible after birth, even in the operating room. The steps to implementing that policy involved getting the anesthesiology department on board with supporting the policy in the OR and training the circulating nursing staff to ensure a that nurse is available to monitor the newborn.

“I think the most important thing to know is that it’s absolutely doable and that you just have to have a champion just like any other quality initiative,” she said. One of the best ways to do that is to have the patients themselves request it, she noted, compared with its being requested by a physician or nurse.

“I think some patients are disappointed when they have to undergo cesarean delivery or feel like they’re missing out if they can’t have a vaginal delivery,” Dr. Collins said. Immediate skin-to-skin contact is “very good for not only physiology, as we read about in this paper – all the things they said about the benefits of skin-to-skin [contact] are true – but it’s really good for mental health. That bonding begins right away.”

As a birth parent, being separated from your newborn for several hours after a cesarean section, on the other hand, can be “pretty devastating,” Dr. Collins said.

“I think this is something that, once it becomes a standard of care, it will be expected that most hospitals should be doing this,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Collins report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Birth parents are typically separated from their newborns following a cesarean section. However, a recent study published in the journal Nursing Open suggests immediate skin-to-skin contact may accelerate uterine contractions, reduce maternal blood loss, reduce newborn crying, improve patient satisfaction and comfort, and increase the rate of breastfeeding.

“[O]ur study contributes to scientific knowledge with key information to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality rates in mothers who have undergone scheduled cesarean sections,” José Miguel Pérez-Jiménez, MD, of the faculty of nursing, physiotherapy, and podiatry at Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena, University of Sevilla, Spain, and colleagues wrote in their study. It promotes greater stability in the mothers by reducing the risk of postpartum hemorrhage, making it better to not separate mother and child in the first hours after this surgery, he said.

Dr. Pérez-Jiménez and colleagues evaluated 83 women who underwent a scheduled cesarean section in an unblinded, randomized controlled trial. The women were randomized to receive skin-to-skin contact in the operating room that continued in the postpartum unit, or the normal protocol after cesarean section that consisted of having the mother transferred to the postanesthesia recovery room while the newborn was sent to a maternity room with a parent or companion. Researchers assessed variables such as plasma hemoglobin, uterine contractions, breastfeeding, and postoperative pain, as well as subjective measures such as maternal satisfaction, comfort, previous cesarean section experience, and newborn crying.

Women who received usual care following cesarean section were more likely to have uterine contractions at the umbilical level compared with the skin-to-skin contact group (70% vs. 3%; P ≤ .0001), while the skin-to-skin group was more likely to have uterine contractions at the infraumbilical level (92.5% vs. 22.5%; P ≤ .0001). There was a statistically significant decrease in predischarge hemoglobin in the control group compared with the skin-to-skin group (10.522 vs. 11.075 g/dL; P ≤ .017); the level of hemoglobin reduction favored the skin-to-skin group (1.01 vs. 2.265 g/dL; P ≤ .0001). Women in the skin-to-skin group were more likely to report mild pain on a 10-point visual analog scale (VAS) after being transferred to the recovery room (1.48 vs. 6.23 points; P ≤ .0001) and being transferred to a maternity room or room in the postpartum unit (0.60 vs. 5.23 points; P ≤ .0001). Breastfeeding at birth was significantly higher among patients with immediate skin-to-skin contact compared with the control group (92.5% vs. 32.5%; P ≤ .0001), and continued at 1 month after birth (92.5% vs. 12.5%; P ≤ .0001). Newborns of mothers in the skin-to-skin group were significantly less likely to cry compared with newborns in the control group (90% vs. 55%; P ≤ .001).

When asked to rate their satisfaction on a 10-point Likert scale, women in the skin-to-skin contact group rated their experience significantly higher than did the control group (9.98 vs. 6.5; P ≤ .0001), and all women who had previously had a cesarean section in the skin-to-skin group (30%) rated their experience at 10 points compared with their previous cesarean section without skin-to-skin contact.

Implementing skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section

Betsy M. Collins, MD, MPH, assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview that while some of the findings were largely unsurprising and “confirmed a lot of the things that we already know about skin-to-skin [contact],” one major finding was the “stark difference” in the percentage of new birth parents who started breastfeeding after skin-to-skin contact and were still breastfeeding at 1 month postpartum compared with birth parents in the control group. She was not involved with the study and noted that the results complement recommendations from the World Health Organization on starting breastfeeding within the first hour after birth and continuing breastfeeding through the first 6 months of life.

“That was likely one of the greatest take-home points from the study ... that early skin-to-skin really promoted initiation of breastfeeding,” Dr. Collins said.

Two reasons why skin-to-skin contact after cesarean section isn’t regularly provided is that it can be difficult for personnel and safety reasons to have an extra nurse to continue monitoring the health of the newborn in the operating room, and there is a lack of culture supporting of skin-to-skin contact in the OR, Dr. Collins explained.

“Just like anything else, if it’s built into your standard operating procedure, then you have everything set up in place to do that initial assessment of the infant and then get the baby skin-to-skin as quickly as possible,” she said. If it’s your standard operating procedure to not provide skin-to-skin contact, she said, then there is a little bit more inertia to overcome to start providing it as a standard procedure.

At her center, Dr. Collins said skin-to-skin contact is initiated as soon as possible after birth, even in the operating room. The steps to implementing that policy involved getting the anesthesiology department on board with supporting the policy in the OR and training the circulating nursing staff to ensure a that nurse is available to monitor the newborn.

“I think the most important thing to know is that it’s absolutely doable and that you just have to have a champion just like any other quality initiative,” she said. One of the best ways to do that is to have the patients themselves request it, she noted, compared with its being requested by a physician or nurse.

“I think some patients are disappointed when they have to undergo cesarean delivery or feel like they’re missing out if they can’t have a vaginal delivery,” Dr. Collins said. Immediate skin-to-skin contact is “very good for not only physiology, as we read about in this paper – all the things they said about the benefits of skin-to-skin [contact] are true – but it’s really good for mental health. That bonding begins right away.”

As a birth parent, being separated from your newborn for several hours after a cesarean section, on the other hand, can be “pretty devastating,” Dr. Collins said.

“I think this is something that, once it becomes a standard of care, it will be expected that most hospitals should be doing this,” she said.

The authors and Dr. Collins report no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM NURSING OPEN

Docs used permanent, not temporary stitches; lawsuits result

The first in what have come to be known as the “wrong stitches” cases has been settled, a story in The Ledger reports.

The former plaintiff in the now-settled suit is Carrie Monk, a Lakeland, Fla., resident who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center several years ago. (The medical center is managed by Lakeland Regional Health Systems.) D As a result, over the next 19 months, she experienced abdominal pain and constant bleeding, which in turn affected her personal life as well as her work as a nurse in the intensive care unit. She underwent follow-up surgery to have the permanent sutures removed, but two could not be identified and excised.

In July 2020, Ms. Monk filed a medical malpractice claim against Lakeland Regional Health, its medical center, and the ob-gyns who had performed her surgery. She was among the first of the women who had received the permanent sutures to do so.

On February 28, 2021, The Ledger ran a story on Ms. Monk’s suit. Less than 2 weeks later, Lakeland Regional Health sent letters to patients who had undergone “wrong stitch” surgeries, cautioning of possible postsurgical complications. The company reportedly kept secret how many letters it had sent out.

Since then, at least nine similar suits have been filed against Lakeland Regional Health, bringing the total number of such suits to 12. Four of these suits have been settled, including Ms. Monk’s. Of the remaining eight cases, several are in various pretrial stages.

Under the terms of her settlement, neither Ms. Monk nor her attorney may disclose what financial compensation or other awards she’s received. The attorney, however, referred to the settlement as “amicable.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first in what have come to be known as the “wrong stitches” cases has been settled, a story in The Ledger reports.

The former plaintiff in the now-settled suit is Carrie Monk, a Lakeland, Fla., resident who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center several years ago. (The medical center is managed by Lakeland Regional Health Systems.) D As a result, over the next 19 months, she experienced abdominal pain and constant bleeding, which in turn affected her personal life as well as her work as a nurse in the intensive care unit. She underwent follow-up surgery to have the permanent sutures removed, but two could not be identified and excised.

In July 2020, Ms. Monk filed a medical malpractice claim against Lakeland Regional Health, its medical center, and the ob-gyns who had performed her surgery. She was among the first of the women who had received the permanent sutures to do so.

On February 28, 2021, The Ledger ran a story on Ms. Monk’s suit. Less than 2 weeks later, Lakeland Regional Health sent letters to patients who had undergone “wrong stitch” surgeries, cautioning of possible postsurgical complications. The company reportedly kept secret how many letters it had sent out.

Since then, at least nine similar suits have been filed against Lakeland Regional Health, bringing the total number of such suits to 12. Four of these suits have been settled, including Ms. Monk’s. Of the remaining eight cases, several are in various pretrial stages.

Under the terms of her settlement, neither Ms. Monk nor her attorney may disclose what financial compensation or other awards she’s received. The attorney, however, referred to the settlement as “amicable.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The first in what have come to be known as the “wrong stitches” cases has been settled, a story in The Ledger reports.

The former plaintiff in the now-settled suit is Carrie Monk, a Lakeland, Fla., resident who underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy at Lakeland Regional Health Medical Center several years ago. (The medical center is managed by Lakeland Regional Health Systems.) D As a result, over the next 19 months, she experienced abdominal pain and constant bleeding, which in turn affected her personal life as well as her work as a nurse in the intensive care unit. She underwent follow-up surgery to have the permanent sutures removed, but two could not be identified and excised.

In July 2020, Ms. Monk filed a medical malpractice claim against Lakeland Regional Health, its medical center, and the ob-gyns who had performed her surgery. She was among the first of the women who had received the permanent sutures to do so.

On February 28, 2021, The Ledger ran a story on Ms. Monk’s suit. Less than 2 weeks later, Lakeland Regional Health sent letters to patients who had undergone “wrong stitch” surgeries, cautioning of possible postsurgical complications. The company reportedly kept secret how many letters it had sent out.

Since then, at least nine similar suits have been filed against Lakeland Regional Health, bringing the total number of such suits to 12. Four of these suits have been settled, including Ms. Monk’s. Of the remaining eight cases, several are in various pretrial stages.

Under the terms of her settlement, neither Ms. Monk nor her attorney may disclose what financial compensation or other awards she’s received. The attorney, however, referred to the settlement as “amicable.”

The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chest reconstruction surgeries up nearly fourfold among adolescents

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The number of chest reconstruction surgeries performed for adolescents rose nearly fourfold between 2016 and 2019, researchers report in a study published in JAMA Pediatrics.

“To our knowledge, this study is the largest investigation to date of gender-affirming chest reconstruction in a pediatric population. The results demonstrate substantial increases in gender-affirming chest reconstruction for adolescents,” the authors report.

The researchers, from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, Tenn., used the Nationwide Ambulatory Surgery Sample to identify youth with gender dysphoria who underwent top surgery to remove, or, in rare cases, to add breasts.

The authors identified 829 chest surgeries. They adjusted the number to a weighted figure of 1,130 patients who underwent chest reconstruction during the study period. Of those, 98.6% underwent masculinizing surgery to remove breasts, and 1.4% underwent feminizing surgery. Roughly 100 individuals received gender-affirming chest surgeries in 2016. In 2019, the number had risen to 489 – a 389% increase, the authors reported.

Approximately 44% of the patients in the study were aged 17 years at the time of surgery, while 5.5% were younger than 14.

Around 78% of the individuals who underwent chest surgeries in 2019 were White, 2.7% were Black, 12.2% were Hispanic, and 2.5% were Asian or Pacific Islander. Half of the patients who underwent surgery had a household income of $82,000 or more, according to the researchers.

“Most transgender adolescents had either public or private health insurance coverage for these procedures, contrasting with the predominance of self-payers reported in earlier studies on transgender adults,” write the researchers, citing a 2018 study of trends in transgender surgery.

Masculinizing chest reconstruction, such as mastectomy, and feminizing chest reconstruction, such as augmentation mammaplasty, can be performed as outpatient procedures or as ambulatory surgeries, according to another study .

The study was supported by a grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences Clinical and Translational Science Awards Program. One author has reported receiving grant funding from Merck.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

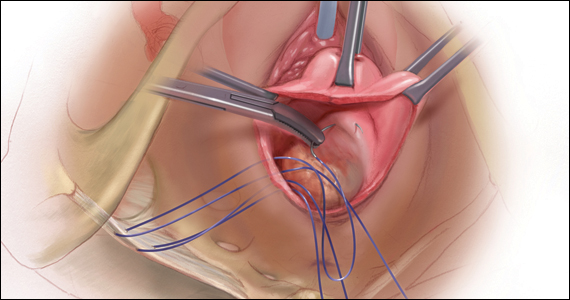

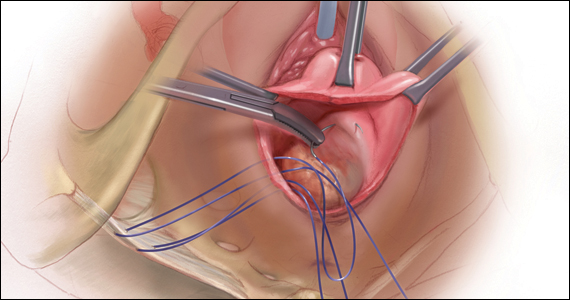

Options and outcomes for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

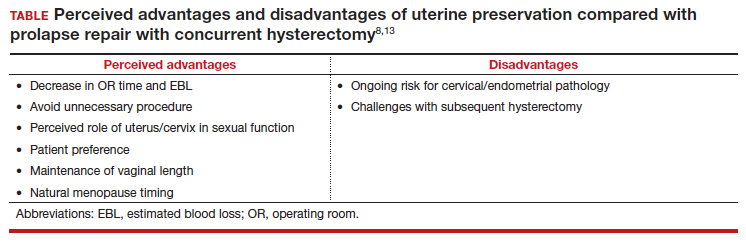

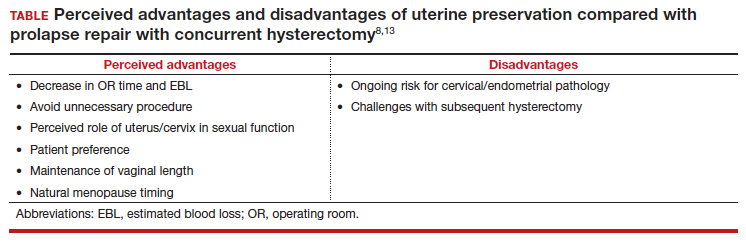

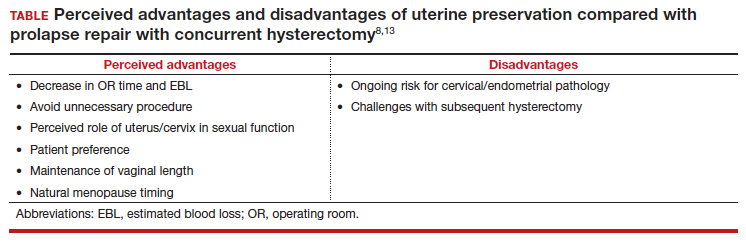

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

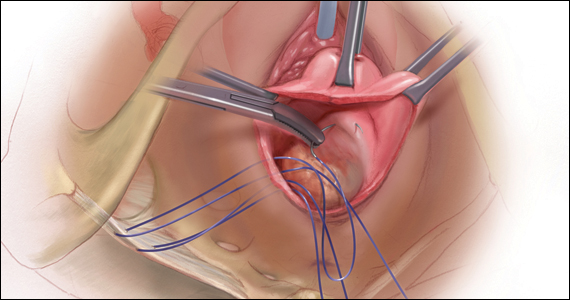

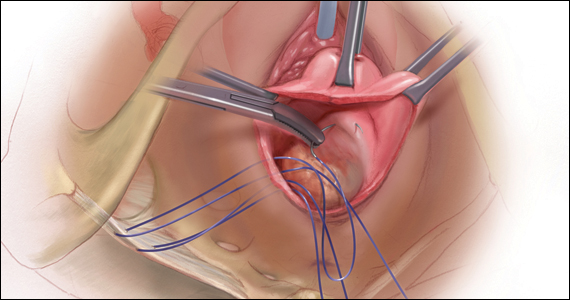

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

- DeLancey JO. Anatomic aspects of vaginal eversion after hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(6 pt 1):1717-1724; discussion 1724-1728. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(92)91562-o.

- Madsen AM, Raker C, Sung VW. Trends in hysteropexy and apical support for uterovaginal prolapse in the United States from 2002 to 2012. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017;23:365-371. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000426.

- Korbly NB, Kassis NC, Good MM, et al. Patient preferences for uterine preservation and hysterectomy in women with pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;209:470.e16. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2013.08.003.

- Frick AC, Barber MD, Paraiso MF, et al. Attitudes toward hysterectomy in women undergoing evaluation for uterovaginal prolapse. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2013;19:103-109. doi:10.1097/SPV.0b013e31827d8667.

- Farquhar CM, Sadler L, Harvey SA, et al. The association of hysterectomy and menopause: a prospective cohort study. BJOG. 2005;112:956-962. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00696.x

- Gutman R, Maher C. Uterine-preserving POP surgery. Int Urogynecol J. 2013;24:1803-1813. doi:10.1007/s00192-0132171-2.

- Frick AC, Walters MD, Larkin KS, et al. Risk of unanticipated abnormal gynecologic pathology at the time of hysterectomy for uterovaginal prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:507. e1-4. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.077.

- Meriwether KV, Balk EM, Antosh DD, et al. Uterine-preserving surgeries for the repair of pelvic organ prolapse: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:505-522. doi:10.1007/s00192-01903876-2.

- Meriwether KV, Antosh DD, Olivera CK, et al. Uterine preservation vs hysterectomy in pelvic organ prolapse surgery: a systematic review with meta-analysis and clinical practice guidelines. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:129-146. e2. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2018.01.018.

- Lin TY, Su TH, Wang YL, et al. Risk factors for failure of transvaginal sacrospinous uterine suspension in the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse. J Formos Med Assoc. 2005;104:249-253.

- Hyakutake MT, Cundiff GW, Geoffrion R. Cervical elongation following sacrospinous hysteropexy: a case series. Int Urogynecol J. 2014;25:851-854. doi:10.1007/s00192-013-2258-9.

- Thys SD, Coolen AL, Martens IR, et al. A comparison of long-term outcome between Manchester Fothergill and vaginal hysterectomy as treatment for uterine descent. Int Urogynecol J. 2011;22:1171-1178. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1422-3.

- Ridgeway BM, Meriwether KV. Uterine preservation in pelvic organ prolapse surgery. In: Walters & Karram Urogynecology and Reconstructive Pelvic Surgery. 5th ed. Elsevier, Inc; 2022:358-373.

- FitzGerald MP, Richter HE, Siddique S, et al; for the Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Colpocleisis: a review. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:261-271. doi:10.1007/s00192005-1339-9.

- Winkelman WD, Haviland MJ, Elkadry EA. Long-term pelvic f loor symptoms, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret following colpocleisis. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2020;26:558562. doi:10.1097/SPV.000000000000602.

- Lu M, Zeng W, Ju R, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes, recurrence, satisfaction, and regret after total colpocleisis with concomitant vaginal hysterectomy: a retrospective single-center study. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2021;27(4):e510-e515. doi:10.1097/SPV.0000000000000900.

- Wang X, Chen Y, Hua K. Pelvic symptoms, body image, and regret after LeFort colpocleisis: a long-term follow-up. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2017;24:415-419. doi:10.1016/j. jmig.2016.12.015.

- Schulten SFM, Detollenaere RJ, Stekelenburg J, et al. Sacrospinous hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension in women with uterine prolapse stage 2 or higher: observational followup of a multicentre randomised trial. BMJ. 2019;366:I5149. doi:10.1136/bmj.l5149.

- Schulten SF, Detollenaere RJ, IntHout J, et al. Risk factors for pelvic organ prolapse recurrence after sacrospinous hysteropexy or vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2022;227:252.e1252.e9. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2022.04.017.

- Hemming C, Constable L, Goulao B, et al. Surgical interventions for uterine prolapse and for vault prolapse: the two VUE RCTs. Health Technol Assess. 2020;24:1-220. doi:10.3310/hta24130.

- Romanzi LJ, Tyagi R. Hysteropexy compared to hysterectomy for uterine prolapse surgery: does durability differ? Int Urogynecol J. 2012;23:625-631. doi:10.1007/s00192-011-1635-5.

- Rosen DM, Shukla A, Cario GM, et al. Is hysterectomy necessary for laparoscopic pelvic floor repair? A prospective study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:729-734. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2008.08.010.

- Bedford ND, Seman EI, O’Shea RT, et al. Effect of uterine preservation on outcome of laparoscopic uterosacral suspension. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2013;20(2):172-177. doi:10.1016/j.jmig.2012.10.014.

- Diwan A, Rardin CR, Strohsnitter WC, et al. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament uterine suspension compared with vaginal hysterectomy with vaginal vault suspension for uterovaginal prolapse. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17:79-83. doi:10.1007/s00192-005-1346-x.

- de Boer TA, Milani AL, Kluivers KB, et al. The effectiveness of surgical correction of uterine prolapse: cervical amputation with uterosacral ligament plication (modified Manchester) versus vaginal hysterectomy with high uterosacral ligament plication. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2009;20:13131319. doi:10.1007/s00192-009-0945-3.

- Thomas AG, Brodman ML, Dottino PR, et al. Manchester procedure vs. vaginal hysterectomy for uterine prolapse. A comparison. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:299-304.

- Husby KR, Larsen MD, Lose G, et al. Surgical treatment of primary uterine prolapse: a comparison of vaginal native tissue surgical techniques. Int Urogynecol J. 2019;30:18871893. doi:10.1007/s00192-019-03950-9.

- Husby KR, Tolstrup CK, Lose G, et al. Manchester-Fothergill procedure versus vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension: an activity-based costing analysis. Int Urogynecol J. 2018;29:1161-1171. doi:10.1007/s00192-0183575-9.

- Nager CW, Visco AG, Richter HE, et al; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Effect of sacrospinous hysteropexy with graft vs vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension on treatment failure in women with uterovaginal prolapse: 5-year results of a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;225:153.e1-153.e31. doi:10.1016/j. ajog.2021.03.012.

- Rahmanou P, Price N, Jackson SR. Laparoscopic hysteropexy versus vaginal hysterectomy for the treatment of uterovaginal prolapse: a prospective randomized pilot study. Int Urogynecol J. 2015;26:1687-1694. doi:10.1007/s00192-0152761-2.

- Roovers JP, van der Vaart CH, van der Bom JG, et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing abdominal and vaginal prolapse surgery: effects on urogenital function. BJOG. 2004;111:50-56. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00001.x.

- Roovers JP, van der Bom JG, van der Vaart CH, et al. A randomized comparison of post-operative pain, quality of life, and physical performance during the first 6 weeks after abdominal or vaginal surgical correction of descensus uteri. Neurourol Urodyn. 2005;24:334-340. doi:10.1002/nau.20104.

- Schulten SFM, Enklaar RA, Kluivers KB, et al. Evaluation of two vaginal, uterus sparing operations for pelvic organ prolapse: modified Manchester operation (MM) and sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSH), a study protocol for a multicentre randomized non-inferiority trial (the SAM study). BMC Womens Health. 20192;19:49. doi:10.1186/ s12905-019-0749-7.

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.

Currently, work is underway to validate and test the effectiveness of a questionnaire to evaluate the uterus’s importance to the patient seeking prolapse surgery in order to optimize counseling. The VUE trial, which randomizes women to vaginal hysterectomy with suspension versus various prolapse surgeries with uterine preservation, is continuing its 6-year follow-up.20 In the Netherlands, an ongoing randomized, controlled trial (the SAM trial) is comparing the Manchester procedure with sacrospinous hysteropexy and will follow patients up to 24 months.33 Fortunately, both of these trials are rigorously assessing both objective and patient-centered outcomes.

CASE Counseling helps the patient weigh surgical options

After thorough review of her surgical options, the patient elects for a uterine-preserving prolapse repair. She would like to have the most minimally invasive procedure and does not want any permanent mesh used. You suggest, and she agrees to, a sacrospinous ligament hysteropexy, as it is the current technique with the most robust data. ●

CASE Patient desires prolapse repair

A 65-year-old postmenopausal patient (G3P3) presents to your office with symptoms of a vaginal bulge for more than 1 year. She has no urinary incontinence symptoms and no bowel dysfunction symptoms. On examination, you diagnose stage 2 uterovaginal prolapse with both anterior and apical defects. The patient declines expectant and pessary management and desires surgery, but she states that she feels her uterus “is important for me to keep, as my babies grew in there and it is part of me.” She denies any family or personal history of breast, endometrial, or ovarian cancer and has no history of abnormal cervical cancer screening or postmenopausal bleeding. What are the options for this patient?

Who is the appropriate hysteropexy patient, and how do we counsel her?

Uterine prolapse is the third leading cause of benign hysterectomy, with approximately 70,000 procedures performed each year in the United States. It has long been acknowledged that the uterus is a passive bystander to the prolapse process,1 but modern practice often involves a hysterectomy as part of addressing apical prolapse. However, more and more uterine-preserving surgeries are being performed, with one study showing an increase from 1.8% to 5% from 2002 and 2012.2

When presented with the option to keep or remove their uterus during the time of prolapse surgery, 36% of patients indicated that they would prefer to keep their uterus with similar outcomes while 21% would still prefer uterine preservation even if outcomes were inferior compared with hysterectomy.3 Another study showed that 60% of patients would decline concurrent hysterectomy if there were equal surgical outcomes,4 and popular platforms, such as Health magazine (www.health.com) and AARP magazine (www.aarp.org), have listed benign hysterectomy as a “top surgery to avoid.”

Patients desire uterine preservation for many reasons, including concerns about sexual function and pleasure, the uterus being important to their sense of identity or womanhood, and concerns around menopausal symptoms. Early patient counseling and discussion of surgical goals can help clinicians fully understand a patient’s thoughts toward uterine preservation. Women who identified their uterus as important to their sense of self had a 28.2-times chance of preferring uterine preservation.3 Frequently, concerns about menopausal symptoms are more directly related to hormones and ovary removal, not uterus removal, but clinicians should be careful to also counsel patients on the increased risk of menopause in the 5 years after hysterectomy, even with ovarian preservation.5

There are some patients for whom experts do not recommend uterine preservation.6 Patients with an increased risk of cervical or endometrial pathology should be counseled on the benefits of hysterectomy. Additionally, patients who have abnormal uterine bleeding from benign pathology should consider hysterectomy to treat these issues and avoid future workups (TABLE). For postmenopausal patients with recent postmenopausal bleeding, we encourage hysterectomy. A study of patients undergoing hysterectomy at the time of prolapse repair found a rate of 13% unanticipated endometrial pathology with postmenopausal bleeding and negative preoperative workup.7

At this time, a majority of clinicians consider the desire for future fertility to be a relative contraindication to surgical prolapse repair and advise conservative management with pessary until childbearing is complete. This is reasonable, given the paucity of safety data in subsequent pregnancies as well as the lack of prolapse outcomes after those pregnancies.8,9 Lastly, cervical elongation is considered a relative contraindication, as it represents a risk for surgical failure.10,11 This may be counteracted with trachelectomy at the time of hysteropexy or surgeries such as the Manchester repair, which involve a trachelectomy routinely,12 but currently there is no strong evidence for this as routine practice.

Continue to: Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes...

Uterine preservation surgical techniques and outcomes

Le Fort colpocleisis

First described in 1840 by Neugebauer of Poland and later by Le Fort in Paris in 1877, the Le Fort colpocleisis repair technique remains the most reliable prolapse surgery to date.14 The uterus is left in place while the vagina is narrowed and shortened. It typically also is performed with a levator plication to reduce the genital hiatus.

This procedure is quick and effective, with a 90% to 95% success rate. If necessary, it can be performed under local or regional anesthesia, making it a good option for medically frail patients. It is not an option for everyone, however, as penetrative intercourse is no longer an option after surgery. Studies suggest an approximately 13% dissatisfaction rate after the procedure, with most of that coming from postoperative urinary symptoms, such as urgency or stress incontinence,15 and some studies show a dissatisfaction rate as low as 0% in a well-counseled patient population.16,17

Vaginal native tissue hysteropexy

Many patients who elect for uterine preservation at the time of prolapse surgery are “minimalists,” meaning that a vaginal native tissue procedure appeals to them due to the lack of abdominal incisions, decreased operating room time, and lack of permanent graft materials.

Of all the hysteropexy procedures, sacrospinous hysteropexy (SSHP) has the most robust data available. The approach to SSHP can be tailored to the patient’s anatomy and it is performed in a manner similar to posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation. The traditional posterior approach can be used with predominantly posterior prolapse, while an apical approach through a semilunar paracervical incision can be used for predominantly apical prolapse. Expert surgeons agree that one key to success is anchoring the suspension sutures through the cervical stroma, not just the vaginal epithelium.

Researchers in the Netherlands published the 5-year outcomes of a randomized trial that compared SSHP with vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.18 Their data showed no difference between groups in composite failure, reoperation rates, quality of life measures, and postoperative sexual function. Adverse events were very similar to those reported for posthysterectomy sacrospinous ligament fixation, including 15% transient buttock pain. Of note, the same authors explored risk factors for recurrence after SSHP and found that higher body mass index, smoking, and a large point Ba measurement were risk factors for prolapse recurrence.19

A randomized, controlled trial in the United Kingdom (the VUE trial) compared vaginal hysterectomy with apical suspension to uterine preservation with a variety of apical suspension techniques, mostly SSHP, and demonstrated no significant differences in outcomes.20 Overall, SSHP is an excellent option for many patients interested in uterine preservation.

Uterosacral ligament hysteropexy (USHP), when performed vaginally, is very similar to uterosacral ligament suspension at the time of vaginal hysterectomy, with entry into the peritoneal cavity through a posterior colpotomy. The uterosacral ligaments are grasped and delayed absorbable suture placed through the ligaments and anchored into the posterior cervical stroma. Given the maintenance of the normal axis of the vagina, USHP is a good technique for patients with isolated apical defects. Unfortunately, the least amount of quality data is available for USHP at this time. Currently, evidence suggests that complications are rare and that the procedure may offer acceptable anatomic and symptomatic outcomes.21 Some surgeons approach the uterosacral suspension laparoscopically, which also has mixed results in the literature, with failure rates between 8% and 27% and few robust studies.22–24

The Manchester-Fothergill operation, currently not common in the United States but popular in Europe, primarily is considered a treatment for cervical elongation when the uterosacral ligaments are intact. In this procedure, trachelectomy is performed and the uterosacral ligaments are plicated to the uterine body. Sturmdorf sutures are frequently placed to close off the endometrial canal, which can lead to hematometra and other complications of cervical stenosis. Previous unmatched studies have shown similar outcomes with the Manchester procedure compared with vaginal hysterectomy.25,26

The largest study currently available is a registry study from Denmark, with matched cohort populations, that compared the Manchester procedure, SSHP, and total vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.27 This study indicated less morbidity related to the Manchester procedure, decreased anterior recurrence compared with SSHP, and a 7% reoperation rate.27 The same authors also established better cost-effectiveness with the Manchester procedure as opposed to vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.28

Continue to: Vaginal mesh hysteropexy...

Vaginal mesh hysteropexy

Hysteropexy using vaginal mesh is limited in the United States given the removal of vaginal mesh kits from the market by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019. However, a Pelvic Floor Disorders Network randomized trial compared vaginal mesh hysteropexy using the Uphold LITE transvaginal mesh support system (Boston Scientific) and vaginal hysterectomy with uterosacral ligament suspension.29 At 5 years, mesh hysteropexy had fewer failures than hysterectomy (37% vs 54%) and there was no difference in retreatment (9% vs 13%). The authors noted an 8% mesh exposure rate in the mesh hysteropexy group but 12% granulation tissue and 21% suture exposure rate in the hysterectomy group.29

While vaginal mesh hysteropexy was effective in the treatment of apical prolapse, the elevated mesh exposure rate and postoperative complications ultimately led to its removal from the market.

Sacrohysteropexy

Lastly, prolapse surgery with uterine preservation may be accomplished abdominally, most commonly laparoscopically with or without robotic assistance.

Sacrohysteropexy (SHP) involves the attachment of permanent synthetic mesh posteriorly to the posterior vagina and cervix with or without the additional placement of mesh to the anterior vagina and cervix. When the anterior mesh is placed, the arms are typically routed through the broad ligament bilaterally and joined with the posterior mesh for attachment to the anterior longitudinal ligament, overlying the sacrum.

Proponents of this technique endorse the use of mesh to augment already failing native tissues and propose similarities to the durability of sacrocolpopexy. While no randomized controlled trials have compared hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy or supracervical hysterectomy with sacrocolpopexy to sacrohysteropexy, a meta-analysis suggests that sacrohysteropexy may have a decreased risk of mesh exposure but a higher reoperation rate with lower anatomic success.9 Randomized trials that compared abdominal sacrohysteropexy with vaginal hysterectomy and suspension indicate that apical support may be improved with sacrohysteropexy,30 but reoperations, postoperative pain and disability, and urinary dysfunction was higher with SHP.31,32

What further research is needed?

With the increasing patient and clinician interest in uterine preservation, more research is needed to improve patient counseling and surgical planning. Much of the current research compares hysteropexy outcomes with those of traditional prolapse repairs with hysterectomy, with only a few randomized trials. We are lacking robust, prospective comparison studies between hysteropexy methods, especially vaginal native tissue techniques, long-term follow-up on the prevalence of uterine or cervical pathology after hysteropexy, and pregnancy or postpartum outcomes following uterine preservation surgery.