User login

Rosacea: Target treatment to pathogenic pathway

LAHAINA, HAWAII – The pathophysiology of rosacea is complicated, which is why “we try to target our treatments to various areas in this pathogenic pathway” to achieve optimal results, according to Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of dermatology research at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

For example, in a patient with papules and pustules, a topical or oral anti-inflammatory agent is needed “to calm that down.” If background erythema is present, separate from papules and pustules, use a topical alpha-adrenergic agonist, she advised. For telangiectasias, consider a device-based treatment, and for a phyma, a surgical approach, she recommended at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

For the background erythema of rosacea, which she described as “that pink face that’s always there,” the two alpha-adrenergic receptor agonists available, brimonidine gel 0.33%, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2013, and oxymetazoline cream 1%, approved in 2017, both work on the neurovascular junction, but on different receptors.

Brimonidine “kicks in very, very rapidly,” with a significant decrease in background erythema evident within 30 minutes and improvements that last over a 12-hour day, she said. It is effective over a year, but in longterm and postmarketing studies, about 20% of patients experienced exacerbation of erythema, with two peaks of redness. “One occurs at 3-6 hours,” and the other peak occurs when the drug is wearing off later in the day, Dr. Stein Gold said.

A study that sought to identify factors that might make patients more prone to this adverse effect found that “less is better” regarding brimonidine application, with an optimal application of one to three pea-sized dollops on the face, not five as instructed in the package insert. In addition, patients with more than five flushing episodes a week, particularly women, “tend to have more labile disease and [are] more likely to get that rebound erythema,” the study found.

Oxymetazoline 1% in a cream formulation has a “slightly more gentle onset of action and a more gentle offset of action,” without exacerbation of erythema and has been shown to have sustained efficacy over 52 weeks. In a yearlong safety study, there were “no new red flags and we weren’t seeing that redness at hours 3 to 6, or even when you take the patient off the drug,” she noted.

Dr. Stein Gold reported that she has served as a consultant, investigator, or speaker for Galderma, Dermira, Foamix Pharmaceuticals, Valeant, Allergan, Actavis, and Roche.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – The pathophysiology of rosacea is complicated, which is why “we try to target our treatments to various areas in this pathogenic pathway” to achieve optimal results, according to Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of dermatology research at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

For example, in a patient with papules and pustules, a topical or oral anti-inflammatory agent is needed “to calm that down.” If background erythema is present, separate from papules and pustules, use a topical alpha-adrenergic agonist, she advised. For telangiectasias, consider a device-based treatment, and for a phyma, a surgical approach, she recommended at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

For the background erythema of rosacea, which she described as “that pink face that’s always there,” the two alpha-adrenergic receptor agonists available, brimonidine gel 0.33%, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2013, and oxymetazoline cream 1%, approved in 2017, both work on the neurovascular junction, but on different receptors.

Brimonidine “kicks in very, very rapidly,” with a significant decrease in background erythema evident within 30 minutes and improvements that last over a 12-hour day, she said. It is effective over a year, but in longterm and postmarketing studies, about 20% of patients experienced exacerbation of erythema, with two peaks of redness. “One occurs at 3-6 hours,” and the other peak occurs when the drug is wearing off later in the day, Dr. Stein Gold said.

A study that sought to identify factors that might make patients more prone to this adverse effect found that “less is better” regarding brimonidine application, with an optimal application of one to three pea-sized dollops on the face, not five as instructed in the package insert. In addition, patients with more than five flushing episodes a week, particularly women, “tend to have more labile disease and [are] more likely to get that rebound erythema,” the study found.

Oxymetazoline 1% in a cream formulation has a “slightly more gentle onset of action and a more gentle offset of action,” without exacerbation of erythema and has been shown to have sustained efficacy over 52 weeks. In a yearlong safety study, there were “no new red flags and we weren’t seeing that redness at hours 3 to 6, or even when you take the patient off the drug,” she noted.

Dr. Stein Gold reported that she has served as a consultant, investigator, or speaker for Galderma, Dermira, Foamix Pharmaceuticals, Valeant, Allergan, Actavis, and Roche.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – The pathophysiology of rosacea is complicated, which is why “we try to target our treatments to various areas in this pathogenic pathway” to achieve optimal results, according to Linda Stein Gold, MD, director of dermatology research at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit.

For example, in a patient with papules and pustules, a topical or oral anti-inflammatory agent is needed “to calm that down.” If background erythema is present, separate from papules and pustules, use a topical alpha-adrenergic agonist, she advised. For telangiectasias, consider a device-based treatment, and for a phyma, a surgical approach, she recommended at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

For the background erythema of rosacea, which she described as “that pink face that’s always there,” the two alpha-adrenergic receptor agonists available, brimonidine gel 0.33%, approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2013, and oxymetazoline cream 1%, approved in 2017, both work on the neurovascular junction, but on different receptors.

Brimonidine “kicks in very, very rapidly,” with a significant decrease in background erythema evident within 30 minutes and improvements that last over a 12-hour day, she said. It is effective over a year, but in longterm and postmarketing studies, about 20% of patients experienced exacerbation of erythema, with two peaks of redness. “One occurs at 3-6 hours,” and the other peak occurs when the drug is wearing off later in the day, Dr. Stein Gold said.

A study that sought to identify factors that might make patients more prone to this adverse effect found that “less is better” regarding brimonidine application, with an optimal application of one to three pea-sized dollops on the face, not five as instructed in the package insert. In addition, patients with more than five flushing episodes a week, particularly women, “tend to have more labile disease and [are] more likely to get that rebound erythema,” the study found.

Oxymetazoline 1% in a cream formulation has a “slightly more gentle onset of action and a more gentle offset of action,” without exacerbation of erythema and has been shown to have sustained efficacy over 52 weeks. In a yearlong safety study, there were “no new red flags and we weren’t seeing that redness at hours 3 to 6, or even when you take the patient off the drug,” she noted.

Dr. Stein Gold reported that she has served as a consultant, investigator, or speaker for Galderma, Dermira, Foamix Pharmaceuticals, Valeant, Allergan, Actavis, and Roche.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

Effect of In-Office Samples on Dermatologists’ Prescribing Habits: A Retrospective Review

Over the years, there has been growing concern about the relationship between physicians and pharmaceutical companies. Many studies have demonstrated that pharmaceutical interactions and incentives can influence physicians’ prescribing habits.1-3 As a result, many academic centers have adopted policies that attempt to limit the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on faculty and in-training physicians. Although these policies can vary greatly, they generally limit access of pharmaceutical representatives to providers and restrict pharmaceutical samples.4,5 This policy shift has even been reported in private practice.6

At the heart of the matter is the question: What really influences physicians to write a prescription for a particular medication? Is it cost, efficacy, or representatives pushing a product? Prior studies illustrate that generic medications are equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. In fact, current regulations require no more than 5% to 7% difference in bioequivalence.7-9 Although most generic medications are bioequivalent, it may not be universal.10

Garrison and Levin11 distributed a survey to US-based prescribers in family practice, psychiatry, and internal medicine and found that prescribers deemed patient response and success as the highest priority when determining which drugs to prescribe. In contrast, drug representatives and free samples only slightly contributed.11 Considering the minimum duration for efficacy of a medication such as an antidepressant vs a topical steroid, this pattern may differ with samples in dermatologic settings. Interestingly, another survey concluded that samples were associated with “sticky” prescribing habits, noting that physicians would prescribe a brand-name medication after using a sample, despite increased cost to the patient.12 Further, it has been suggested that recipients of free samples may experience increased costs in the long run, which contrasts a stated goal of affordability to patients.12,13

Physician interaction with pharmaceutical companies begins as early as medical school,14 with physicians reporting interactions as often as 4 times each month.14-18 Interactions can include meetings with pharmaceutical representatives, sponsored meals, gifts, continuing medical education sponsorship, funding for travel, pharmaceutical representative speakers, research funding, and drug samples.3

A 2014 study reported that prescribing habits are influenced by the free drug samples provided by nongeneric pharmaceutical companies.19 Nationally, the number of brand-name and branded generic medications constitute 79% of prescriptions, yet together they only comprise 17% of medications prescribed at an academic medical clinic that does not provide samples. The number of medications with samples being prescribed by dermatologists increased by 15% over 9 years, which may correlate with the wider availability of medication samples, more specifically an increase in branded generic samples.19 This potential interaction is the reason why institutions question the current influence of pharmaceutical companies. Samples may appear convenient, allowing a patient to test the medication prior to committing; however, with brand-name samples being provided to the physician, he/she may become more inclined to prescribe the branded medication.12,15,19-22 Because brand-name medications are more expensive than generic medications, this practice can increase the cost of health care.13 One study found that over 1 year, the overuse of nongeneric medications led to a loss of potential savings throughout 49 states, equating to $229 million just through Medicaid; interestingly, it was noted that in some states, a maximum reimbursement is set by Medicaid, regardless of whether the generic or branded medication is dispensed. The authors also noted variability in the potential savings by state, which may be a function of the state-by-state maximum reimbursements for certain medications.23 Another study on oral combination medications estimated Medicare spending on branded drugs relative to the cost if generic combinations had been purchased instead. This study examined branded medications for which the active components were available as over-the-counter (OTC), generic, or same-class generic, and the authors estimated that $925 million could have been saved in 2016 by purchasing a generic substitute.24 The overuse of nongeneric medications when generic alternatives are available becomes an issue that not only financially impacts patients but all taxpayers. However, this pattern may differ if limited only to dermatologic medications, which was not the focus of the prior studies.

To limit conflicts of interest in interactions with the pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology industries, the University of South Florida (USF) Morsani College of Medicine (COM)(Tampa, Florida) implemented its own set of regulations that eliminated in-office pharmaceutical samples, in addition to other restrictions. This study aimed to investigate if there was a change in the prescribing habits of academic dermatologists after their medical school implemented these new policies.

We hypothesized that the number of brand-name drugs prescribed by physicians in the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery would change following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes. We sought to determine how physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery changed following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes.

Methods

Data Collection

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted to investigate the effect of the USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes on physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery. Medical records of patients seen for common dermatology diagnoses before (January 1, 2010, to May 30, 2010) and after (August 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011) the pharmaceutical policy changes were reviewed, and all medications prescribed were recorded. Data were collected from medical records within the USF Health electronic medical record system and included visits with each of the department’s 3 attending dermatologists. The diagnoses included in the study—acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, and rosacea—were chosen because in-office samples were available. Prescribing data from the first 100 consecutive medical records were collected from each time period, and a medical record was included only if it contained at least 1 of the following diagnoses: acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, or rosacea. The assessment and plan of each progress note were reviewed, and the exact medication name and associated diagnosis were recorded for each prescription. Subsequently, each medication was reviewed and placed in 1 of 3 categories: brand name, generic, and OTC. The total number of prescriptions for each diagnosis (per visit/note); the specific number of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note); and the percentage of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note and per diagnosis in total) were calculated. To ensure only intended medications were included, each medication recorded in the medical record note was cross-referenced with the prescribed medication in the electronic medical record. The primary objective of this study was to capture the prescribing physician’s intent as proxied by the pattern of prescription. Thus, changes made in prescriptions after the initial plan—whether insurance related or otherwise—were not relevant to this investigation.

The data were collected to compare the percentage of brand vs generic or OTC prescriptions per diagnosis to see if there was a difference in the prescribing habits before and after the pharmaceutical policy changes. Of note, several other pieces of data were collected from each medical record, including age, race, class of insurance (ie, Medicare, Medicaid, private health maintenance organization, private preferred provider organization), subtype diagnoses, and whether the prescription was new or a refill. The information gathered from the written record on the assessment and plan was verified using prescriptions ordered in the Allscripts electronic record, and any difference was noted. No identifying information that could be used to easily identify study participants was recorded.

Differences in prescribing habits across diagnoses before and after the policy changes were ascertained using a Fisher exact test and were further assessed using a mixed effects ordinal logistic regression model that accounted for within-provider clustering and baseline patient characteristics. An ordinal model was chosen to recognize differences in average cost among brand-name, generic, and OTC medications.

Results

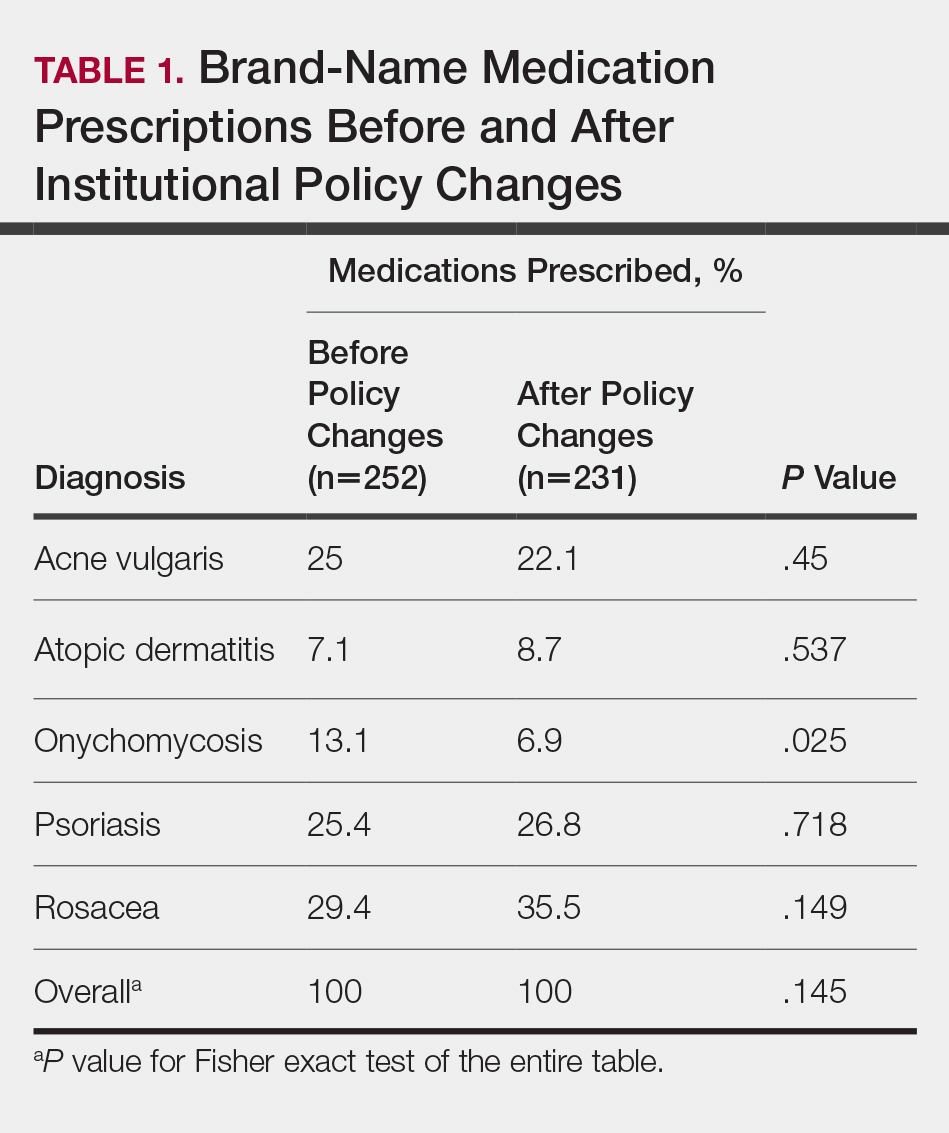

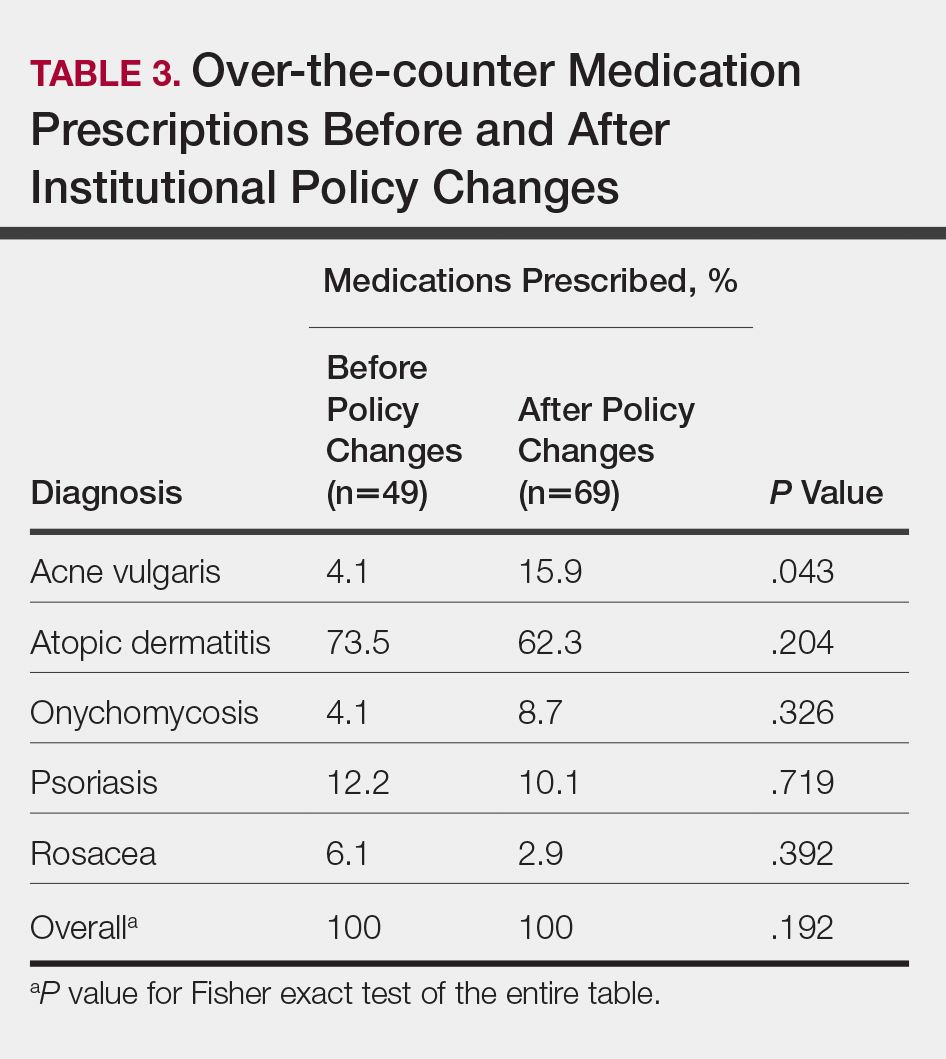

In total, 200 medical records were collected. For the period analyzed before the policy change, 252 brand-name medications were prescribed compared to 231 prescribed for the period analyzed after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in brand-name medications prescribed before and after the policy changes (P=.145; Fisher exact test)(Table 1). There also was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in generic prescriptions, which totaled 153 before and 134 after the policy changes (P=.872; Fisher exact test)(Table 2). Over-the-counter prescriptions totaled 49 before and 69 after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference before and after the policy changes for OTC medications (P=.192; Fisher exact test)(Table 3).

Comment

Although some medical institutions are diligently working to limit the potential influence pharmaceutical companies have on physician prescribing habits,4,5,25 the effect on physician prescribing habits is only now being established.15 Prior studies12,19,21 have found evidence that medication samples may lead to overuse of brand-name medications, but these findings do not hold true for the USF dermatologists included in this study, perhaps due to the difference in pharmaceutical company interactions or physicians maintaining prior prescription habits that were unrelated to the policy. Although this study focused on policy changes for in-office samples, prior studies either included other forms of interaction21 or did not include samples.22

Pharmaceutical samples allow patients to try a medication before committing to a long-term course of treatment with a particular medication, which has utility for physicians and patients. Although brand-name prescriptions may cost more, a trial period may assist the patient in deciding whether the medication is worth purchasing. Furthermore, physicians may feel more comfortable prescribing a medication once the individual patient has demonstrated a benefit from the sample, which may be particularly true in a specialty such as dermatology in which many branded topical medications contain a different vehicle than generic formulations, resulting in notable variations in active medication delivery and efficacy. Given the higher cost of branded topical medications, proving efficacy in patients through samples can provide a useful tool to the physician to determine the need for a branded formulation.

The benefits described are subjective but should not be disregarded. Although Hurley et al19 found that the number of brand-name medications prescribed increases as more samples are given out, our study demonstrated that after eliminating medication samples, there was no significant difference in the percentage of brand-name medications prescribed compared to generic and OTC medications.

Physician education concerning the price of each brand-name medication prescribed in office may be one method of reducing the amount of such prescriptions. Physicians generally are uninformed of the cost of the medications being prescribed26 and may not recognize the financial burden one medication may have compared to its alternative. However, educating physicians will empower them to make the conscious decision to prefer or not prefer a brand-name medication. With some generic medications shown to have a difference in bioequivalence compared to their brand-name counterparts, a physician may find more success prescribing the brand-name medications, regardless of pharmaceutical company influence, which is an alternative solution to policy changes that eliminate samples entirely. Although this study found insufficient evidence that removing samples decreases brand-name medication prescriptions, it is imperative that solutions are established to reduce the country’s increasing burden of medical costs.

Possible shortfalls of this study include the short period of time between which prepolicy data and postpolicy data were collected. It is possible that providers did not have enough time to adjust their prescribing habits or that providers would not have changed a prescribing pattern or preference simply because of a policy change. Future studies could allow a time period greater than 2 years to compare prepolicy and postpolicy prescribing habits, or a future study might make comparisons of prescriber patterns at different institutions that have different policies. Another possible shortfall is that providers and patients were limited to those at the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery at the USF Morsani COM. Although this study has found insufficient evidence of a difference in prescribing habits, it may be beneficial to conduct a larger study that encompasses multiple academic institutions with similar policy changes. Most importantly, this study only investigated the influence of in-office pharmaceutical samples on prescribing patterns. This study did not look at the many other ways in which providers may be influenced by pharmaceutical companies, which likely is a significant confounding variable in this study. Continued additional studies that specifically examine other methods through which providers may be influenced would be helpful in further examining the many ways in which physician prescription habits are influenced.

Conclusion

Changes in pharmaceutical policy in 2011 at USF Morsani COM specifically banned in-office samples. The totality of evidence in this study shows modest observational evidence of a change in the postpolicy odds relative to prepolicy odds, but the data also are compatible with no change between prescribing habits before and after the policy changes. Further study is needed to fully understand this relationship.

- Sondergaard J, Vach K, Kragstrup J, et al. Impact of pharmaceutical representative visits on GPs’ drug preferences. Fam Pract. 2009;26:204-209.

- Jelinek GA, Neate SL. The influence of the pharmaceutical industry in medicine. J Law Med. 2009;17:216-223.

- Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373-380.

- Coleman DL. Establishing policies for the relationship between industry and clinicians: lessons learned from two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2008;83:882-887.

- Coleman DL, Kazdin AE, Miller LA, et al. Guidelines for interactions between clinical faculty and the pharmaceutical industry: one medical school’s approach. Acad Med. 2006;81:154-160.

- Evans D, Hartung DM, Beasley D, et al. Breaking up is hard to do: lessons learned from a pharma-free practice transformation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:332-338.

- Davit BM, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, et al. Comparing generic and innovator drugs: a review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States Food and Drug Administration. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1583-1597.

- Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2514-2526.

- McCormack J, Chmelicek JT. Generic versus brand name: the other drug war. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:911.

- Borgheini G. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1578-1592.

- Garrison GD, Levin GM. Factors affecting prescribing of the newer antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:10-14.

- Rafique S, Sarwar W, Rashid A, et al. Influence of free drug samples on prescribing by physicians: a cross sectional survey. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:465-467.

- Alexander GC, Zhang J, Basu A. Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46:394-402.

- Hodges B. Interactions with the pharmaceutical industry: experiences and attitudes of psychiatry residents, interns and clerks. CMAJ. 1995;153:553-559.

- Brotzman GL, Mark DH. The effect on resident attitudes of regulatory policies regarding pharmaceutical representative activities. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:130-134.

- Keim SM, Sanders AB, Witzke DB, et al. Beliefs and practices of emergency medicine faculty and residents regarding professional interactions with the biomedical industry. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1576-1581.

- Thomson AN, Craig BJ, Barham PM. Attitudes of general practitioners in New Zealand to pharmaceutical representatives. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:220-223.

- Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA. 1995;273:1296-1298.

- Hurley MP, Stafford RS, Lane AT. Characterizing the relationship between free drug samples and prescription patterns for acne vulgaris and rosacea. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:487-493.

- Lexchin J. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: what does the literature say? CMAJ. 1993;149:1401-1407.

- Lieb K, Scheurich A. Contact between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry, their perceptions, and the effects on prescribing habits. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110130.

- Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, et al. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians’ prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000352.

- Fischer MA, Avorn J. Economic consequences of underuse of generic drugs: evidence from Medicaid and implications for prescription drug benefit plans. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1051-1064.

- Sacks CA, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS, et al. Medicare spending on brand-name combination medications vs their generic constituents. JAMA. 2018;320:650-656.

- Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA. 2006;295:429-433.

- Allan GM, Lexchin J, Wiebe N. Physician awareness of drug cost: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e283.

Over the years, there has been growing concern about the relationship between physicians and pharmaceutical companies. Many studies have demonstrated that pharmaceutical interactions and incentives can influence physicians’ prescribing habits.1-3 As a result, many academic centers have adopted policies that attempt to limit the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on faculty and in-training physicians. Although these policies can vary greatly, they generally limit access of pharmaceutical representatives to providers and restrict pharmaceutical samples.4,5 This policy shift has even been reported in private practice.6

At the heart of the matter is the question: What really influences physicians to write a prescription for a particular medication? Is it cost, efficacy, or representatives pushing a product? Prior studies illustrate that generic medications are equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. In fact, current regulations require no more than 5% to 7% difference in bioequivalence.7-9 Although most generic medications are bioequivalent, it may not be universal.10

Garrison and Levin11 distributed a survey to US-based prescribers in family practice, psychiatry, and internal medicine and found that prescribers deemed patient response and success as the highest priority when determining which drugs to prescribe. In contrast, drug representatives and free samples only slightly contributed.11 Considering the minimum duration for efficacy of a medication such as an antidepressant vs a topical steroid, this pattern may differ with samples in dermatologic settings. Interestingly, another survey concluded that samples were associated with “sticky” prescribing habits, noting that physicians would prescribe a brand-name medication after using a sample, despite increased cost to the patient.12 Further, it has been suggested that recipients of free samples may experience increased costs in the long run, which contrasts a stated goal of affordability to patients.12,13

Physician interaction with pharmaceutical companies begins as early as medical school,14 with physicians reporting interactions as often as 4 times each month.14-18 Interactions can include meetings with pharmaceutical representatives, sponsored meals, gifts, continuing medical education sponsorship, funding for travel, pharmaceutical representative speakers, research funding, and drug samples.3

A 2014 study reported that prescribing habits are influenced by the free drug samples provided by nongeneric pharmaceutical companies.19 Nationally, the number of brand-name and branded generic medications constitute 79% of prescriptions, yet together they only comprise 17% of medications prescribed at an academic medical clinic that does not provide samples. The number of medications with samples being prescribed by dermatologists increased by 15% over 9 years, which may correlate with the wider availability of medication samples, more specifically an increase in branded generic samples.19 This potential interaction is the reason why institutions question the current influence of pharmaceutical companies. Samples may appear convenient, allowing a patient to test the medication prior to committing; however, with brand-name samples being provided to the physician, he/she may become more inclined to prescribe the branded medication.12,15,19-22 Because brand-name medications are more expensive than generic medications, this practice can increase the cost of health care.13 One study found that over 1 year, the overuse of nongeneric medications led to a loss of potential savings throughout 49 states, equating to $229 million just through Medicaid; interestingly, it was noted that in some states, a maximum reimbursement is set by Medicaid, regardless of whether the generic or branded medication is dispensed. The authors also noted variability in the potential savings by state, which may be a function of the state-by-state maximum reimbursements for certain medications.23 Another study on oral combination medications estimated Medicare spending on branded drugs relative to the cost if generic combinations had been purchased instead. This study examined branded medications for which the active components were available as over-the-counter (OTC), generic, or same-class generic, and the authors estimated that $925 million could have been saved in 2016 by purchasing a generic substitute.24 The overuse of nongeneric medications when generic alternatives are available becomes an issue that not only financially impacts patients but all taxpayers. However, this pattern may differ if limited only to dermatologic medications, which was not the focus of the prior studies.

To limit conflicts of interest in interactions with the pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology industries, the University of South Florida (USF) Morsani College of Medicine (COM)(Tampa, Florida) implemented its own set of regulations that eliminated in-office pharmaceutical samples, in addition to other restrictions. This study aimed to investigate if there was a change in the prescribing habits of academic dermatologists after their medical school implemented these new policies.

We hypothesized that the number of brand-name drugs prescribed by physicians in the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery would change following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes. We sought to determine how physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery changed following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes.

Methods

Data Collection

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted to investigate the effect of the USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes on physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery. Medical records of patients seen for common dermatology diagnoses before (January 1, 2010, to May 30, 2010) and after (August 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011) the pharmaceutical policy changes were reviewed, and all medications prescribed were recorded. Data were collected from medical records within the USF Health electronic medical record system and included visits with each of the department’s 3 attending dermatologists. The diagnoses included in the study—acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, and rosacea—were chosen because in-office samples were available. Prescribing data from the first 100 consecutive medical records were collected from each time period, and a medical record was included only if it contained at least 1 of the following diagnoses: acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, or rosacea. The assessment and plan of each progress note were reviewed, and the exact medication name and associated diagnosis were recorded for each prescription. Subsequently, each medication was reviewed and placed in 1 of 3 categories: brand name, generic, and OTC. The total number of prescriptions for each diagnosis (per visit/note); the specific number of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note); and the percentage of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note and per diagnosis in total) were calculated. To ensure only intended medications were included, each medication recorded in the medical record note was cross-referenced with the prescribed medication in the electronic medical record. The primary objective of this study was to capture the prescribing physician’s intent as proxied by the pattern of prescription. Thus, changes made in prescriptions after the initial plan—whether insurance related or otherwise—were not relevant to this investigation.

The data were collected to compare the percentage of brand vs generic or OTC prescriptions per diagnosis to see if there was a difference in the prescribing habits before and after the pharmaceutical policy changes. Of note, several other pieces of data were collected from each medical record, including age, race, class of insurance (ie, Medicare, Medicaid, private health maintenance organization, private preferred provider organization), subtype diagnoses, and whether the prescription was new or a refill. The information gathered from the written record on the assessment and plan was verified using prescriptions ordered in the Allscripts electronic record, and any difference was noted. No identifying information that could be used to easily identify study participants was recorded.

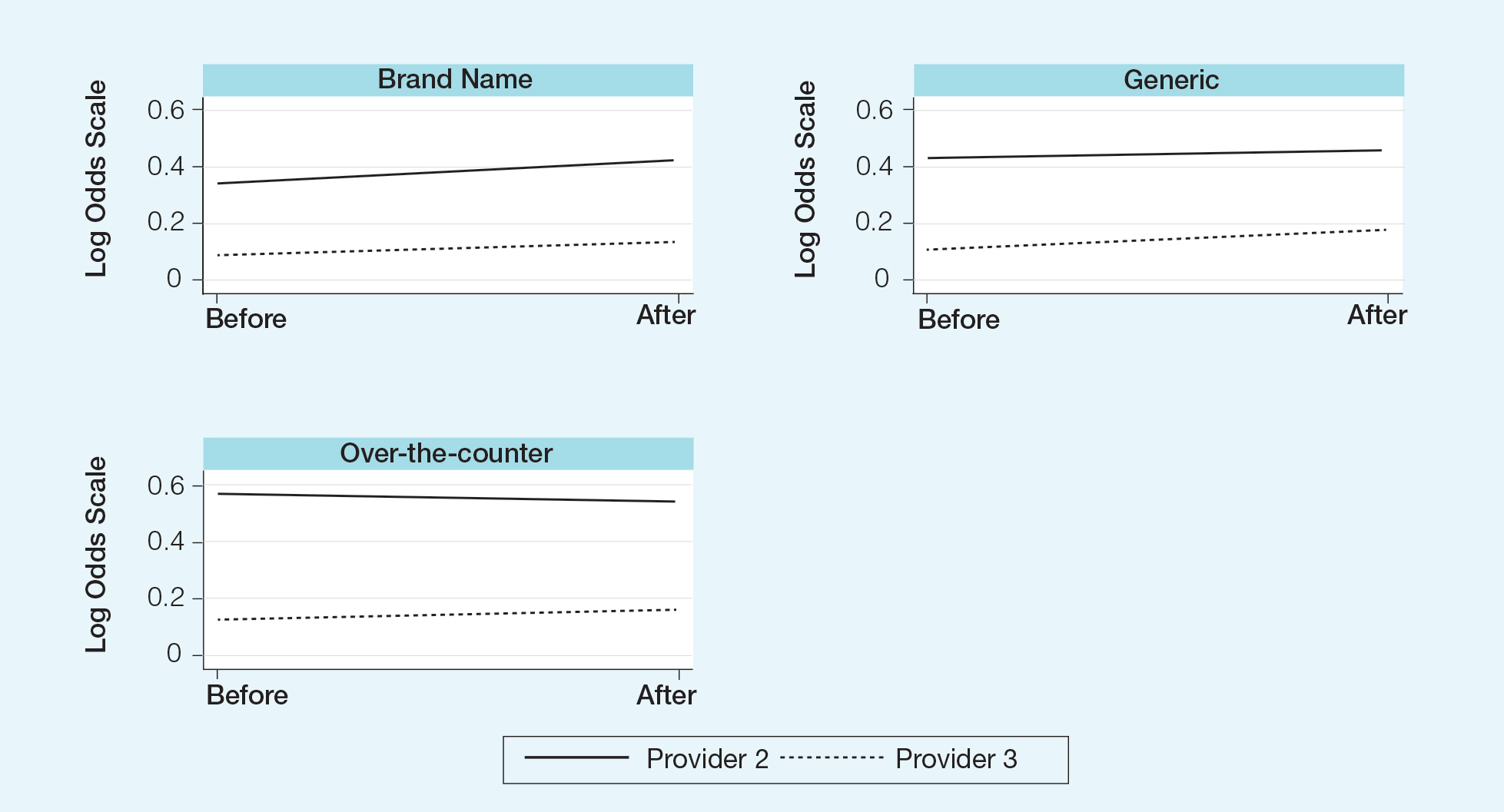

Differences in prescribing habits across diagnoses before and after the policy changes were ascertained using a Fisher exact test and were further assessed using a mixed effects ordinal logistic regression model that accounted for within-provider clustering and baseline patient characteristics. An ordinal model was chosen to recognize differences in average cost among brand-name, generic, and OTC medications.

Results

In total, 200 medical records were collected. For the period analyzed before the policy change, 252 brand-name medications were prescribed compared to 231 prescribed for the period analyzed after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in brand-name medications prescribed before and after the policy changes (P=.145; Fisher exact test)(Table 1). There also was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in generic prescriptions, which totaled 153 before and 134 after the policy changes (P=.872; Fisher exact test)(Table 2). Over-the-counter prescriptions totaled 49 before and 69 after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference before and after the policy changes for OTC medications (P=.192; Fisher exact test)(Table 3).

Comment

Although some medical institutions are diligently working to limit the potential influence pharmaceutical companies have on physician prescribing habits,4,5,25 the effect on physician prescribing habits is only now being established.15 Prior studies12,19,21 have found evidence that medication samples may lead to overuse of brand-name medications, but these findings do not hold true for the USF dermatologists included in this study, perhaps due to the difference in pharmaceutical company interactions or physicians maintaining prior prescription habits that were unrelated to the policy. Although this study focused on policy changes for in-office samples, prior studies either included other forms of interaction21 or did not include samples.22

Pharmaceutical samples allow patients to try a medication before committing to a long-term course of treatment with a particular medication, which has utility for physicians and patients. Although brand-name prescriptions may cost more, a trial period may assist the patient in deciding whether the medication is worth purchasing. Furthermore, physicians may feel more comfortable prescribing a medication once the individual patient has demonstrated a benefit from the sample, which may be particularly true in a specialty such as dermatology in which many branded topical medications contain a different vehicle than generic formulations, resulting in notable variations in active medication delivery and efficacy. Given the higher cost of branded topical medications, proving efficacy in patients through samples can provide a useful tool to the physician to determine the need for a branded formulation.

The benefits described are subjective but should not be disregarded. Although Hurley et al19 found that the number of brand-name medications prescribed increases as more samples are given out, our study demonstrated that after eliminating medication samples, there was no significant difference in the percentage of brand-name medications prescribed compared to generic and OTC medications.

Physician education concerning the price of each brand-name medication prescribed in office may be one method of reducing the amount of such prescriptions. Physicians generally are uninformed of the cost of the medications being prescribed26 and may not recognize the financial burden one medication may have compared to its alternative. However, educating physicians will empower them to make the conscious decision to prefer or not prefer a brand-name medication. With some generic medications shown to have a difference in bioequivalence compared to their brand-name counterparts, a physician may find more success prescribing the brand-name medications, regardless of pharmaceutical company influence, which is an alternative solution to policy changes that eliminate samples entirely. Although this study found insufficient evidence that removing samples decreases brand-name medication prescriptions, it is imperative that solutions are established to reduce the country’s increasing burden of medical costs.

Possible shortfalls of this study include the short period of time between which prepolicy data and postpolicy data were collected. It is possible that providers did not have enough time to adjust their prescribing habits or that providers would not have changed a prescribing pattern or preference simply because of a policy change. Future studies could allow a time period greater than 2 years to compare prepolicy and postpolicy prescribing habits, or a future study might make comparisons of prescriber patterns at different institutions that have different policies. Another possible shortfall is that providers and patients were limited to those at the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery at the USF Morsani COM. Although this study has found insufficient evidence of a difference in prescribing habits, it may be beneficial to conduct a larger study that encompasses multiple academic institutions with similar policy changes. Most importantly, this study only investigated the influence of in-office pharmaceutical samples on prescribing patterns. This study did not look at the many other ways in which providers may be influenced by pharmaceutical companies, which likely is a significant confounding variable in this study. Continued additional studies that specifically examine other methods through which providers may be influenced would be helpful in further examining the many ways in which physician prescription habits are influenced.

Conclusion

Changes in pharmaceutical policy in 2011 at USF Morsani COM specifically banned in-office samples. The totality of evidence in this study shows modest observational evidence of a change in the postpolicy odds relative to prepolicy odds, but the data also are compatible with no change between prescribing habits before and after the policy changes. Further study is needed to fully understand this relationship.

Over the years, there has been growing concern about the relationship between physicians and pharmaceutical companies. Many studies have demonstrated that pharmaceutical interactions and incentives can influence physicians’ prescribing habits.1-3 As a result, many academic centers have adopted policies that attempt to limit the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on faculty and in-training physicians. Although these policies can vary greatly, they generally limit access of pharmaceutical representatives to providers and restrict pharmaceutical samples.4,5 This policy shift has even been reported in private practice.6

At the heart of the matter is the question: What really influences physicians to write a prescription for a particular medication? Is it cost, efficacy, or representatives pushing a product? Prior studies illustrate that generic medications are equivalent to their brand-name counterparts. In fact, current regulations require no more than 5% to 7% difference in bioequivalence.7-9 Although most generic medications are bioequivalent, it may not be universal.10

Garrison and Levin11 distributed a survey to US-based prescribers in family practice, psychiatry, and internal medicine and found that prescribers deemed patient response and success as the highest priority when determining which drugs to prescribe. In contrast, drug representatives and free samples only slightly contributed.11 Considering the minimum duration for efficacy of a medication such as an antidepressant vs a topical steroid, this pattern may differ with samples in dermatologic settings. Interestingly, another survey concluded that samples were associated with “sticky” prescribing habits, noting that physicians would prescribe a brand-name medication after using a sample, despite increased cost to the patient.12 Further, it has been suggested that recipients of free samples may experience increased costs in the long run, which contrasts a stated goal of affordability to patients.12,13

Physician interaction with pharmaceutical companies begins as early as medical school,14 with physicians reporting interactions as often as 4 times each month.14-18 Interactions can include meetings with pharmaceutical representatives, sponsored meals, gifts, continuing medical education sponsorship, funding for travel, pharmaceutical representative speakers, research funding, and drug samples.3

A 2014 study reported that prescribing habits are influenced by the free drug samples provided by nongeneric pharmaceutical companies.19 Nationally, the number of brand-name and branded generic medications constitute 79% of prescriptions, yet together they only comprise 17% of medications prescribed at an academic medical clinic that does not provide samples. The number of medications with samples being prescribed by dermatologists increased by 15% over 9 years, which may correlate with the wider availability of medication samples, more specifically an increase in branded generic samples.19 This potential interaction is the reason why institutions question the current influence of pharmaceutical companies. Samples may appear convenient, allowing a patient to test the medication prior to committing; however, with brand-name samples being provided to the physician, he/she may become more inclined to prescribe the branded medication.12,15,19-22 Because brand-name medications are more expensive than generic medications, this practice can increase the cost of health care.13 One study found that over 1 year, the overuse of nongeneric medications led to a loss of potential savings throughout 49 states, equating to $229 million just through Medicaid; interestingly, it was noted that in some states, a maximum reimbursement is set by Medicaid, regardless of whether the generic or branded medication is dispensed. The authors also noted variability in the potential savings by state, which may be a function of the state-by-state maximum reimbursements for certain medications.23 Another study on oral combination medications estimated Medicare spending on branded drugs relative to the cost if generic combinations had been purchased instead. This study examined branded medications for which the active components were available as over-the-counter (OTC), generic, or same-class generic, and the authors estimated that $925 million could have been saved in 2016 by purchasing a generic substitute.24 The overuse of nongeneric medications when generic alternatives are available becomes an issue that not only financially impacts patients but all taxpayers. However, this pattern may differ if limited only to dermatologic medications, which was not the focus of the prior studies.

To limit conflicts of interest in interactions with the pharmaceutical, medical device, and biotechnology industries, the University of South Florida (USF) Morsani College of Medicine (COM)(Tampa, Florida) implemented its own set of regulations that eliminated in-office pharmaceutical samples, in addition to other restrictions. This study aimed to investigate if there was a change in the prescribing habits of academic dermatologists after their medical school implemented these new policies.

We hypothesized that the number of brand-name drugs prescribed by physicians in the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery would change following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes. We sought to determine how physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery changed following USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes.

Methods

Data Collection

A retrospective review of medical records was conducted to investigate the effect of the USF Morsani COM pharmaceutical policy changes on physician prescribing practices within the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery. Medical records of patients seen for common dermatology diagnoses before (January 1, 2010, to May 30, 2010) and after (August 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011) the pharmaceutical policy changes were reviewed, and all medications prescribed were recorded. Data were collected from medical records within the USF Health electronic medical record system and included visits with each of the department’s 3 attending dermatologists. The diagnoses included in the study—acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, and rosacea—were chosen because in-office samples were available. Prescribing data from the first 100 consecutive medical records were collected from each time period, and a medical record was included only if it contained at least 1 of the following diagnoses: acne vulgaris, atopic dermatitis, onychomycosis, psoriasis, or rosacea. The assessment and plan of each progress note were reviewed, and the exact medication name and associated diagnosis were recorded for each prescription. Subsequently, each medication was reviewed and placed in 1 of 3 categories: brand name, generic, and OTC. The total number of prescriptions for each diagnosis (per visit/note); the specific number of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note); and the percentage of brand, generic, and OTC medications prescribed (per visit/note and per diagnosis in total) were calculated. To ensure only intended medications were included, each medication recorded in the medical record note was cross-referenced with the prescribed medication in the electronic medical record. The primary objective of this study was to capture the prescribing physician’s intent as proxied by the pattern of prescription. Thus, changes made in prescriptions after the initial plan—whether insurance related or otherwise—were not relevant to this investigation.

The data were collected to compare the percentage of brand vs generic or OTC prescriptions per diagnosis to see if there was a difference in the prescribing habits before and after the pharmaceutical policy changes. Of note, several other pieces of data were collected from each medical record, including age, race, class of insurance (ie, Medicare, Medicaid, private health maintenance organization, private preferred provider organization), subtype diagnoses, and whether the prescription was new or a refill. The information gathered from the written record on the assessment and plan was verified using prescriptions ordered in the Allscripts electronic record, and any difference was noted. No identifying information that could be used to easily identify study participants was recorded.

Differences in prescribing habits across diagnoses before and after the policy changes were ascertained using a Fisher exact test and were further assessed using a mixed effects ordinal logistic regression model that accounted for within-provider clustering and baseline patient characteristics. An ordinal model was chosen to recognize differences in average cost among brand-name, generic, and OTC medications.

Results

In total, 200 medical records were collected. For the period analyzed before the policy change, 252 brand-name medications were prescribed compared to 231 prescribed for the period analyzed after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in brand-name medications prescribed before and after the policy changes (P=.145; Fisher exact test)(Table 1). There also was insufficient evidence of an overall difference in generic prescriptions, which totaled 153 before and 134 after the policy changes (P=.872; Fisher exact test)(Table 2). Over-the-counter prescriptions totaled 49 before and 69 after the policy changes. There was insufficient evidence of an overall difference before and after the policy changes for OTC medications (P=.192; Fisher exact test)(Table 3).

Comment

Although some medical institutions are diligently working to limit the potential influence pharmaceutical companies have on physician prescribing habits,4,5,25 the effect on physician prescribing habits is only now being established.15 Prior studies12,19,21 have found evidence that medication samples may lead to overuse of brand-name medications, but these findings do not hold true for the USF dermatologists included in this study, perhaps due to the difference in pharmaceutical company interactions or physicians maintaining prior prescription habits that were unrelated to the policy. Although this study focused on policy changes for in-office samples, prior studies either included other forms of interaction21 or did not include samples.22

Pharmaceutical samples allow patients to try a medication before committing to a long-term course of treatment with a particular medication, which has utility for physicians and patients. Although brand-name prescriptions may cost more, a trial period may assist the patient in deciding whether the medication is worth purchasing. Furthermore, physicians may feel more comfortable prescribing a medication once the individual patient has demonstrated a benefit from the sample, which may be particularly true in a specialty such as dermatology in which many branded topical medications contain a different vehicle than generic formulations, resulting in notable variations in active medication delivery and efficacy. Given the higher cost of branded topical medications, proving efficacy in patients through samples can provide a useful tool to the physician to determine the need for a branded formulation.

The benefits described are subjective but should not be disregarded. Although Hurley et al19 found that the number of brand-name medications prescribed increases as more samples are given out, our study demonstrated that after eliminating medication samples, there was no significant difference in the percentage of brand-name medications prescribed compared to generic and OTC medications.

Physician education concerning the price of each brand-name medication prescribed in office may be one method of reducing the amount of such prescriptions. Physicians generally are uninformed of the cost of the medications being prescribed26 and may not recognize the financial burden one medication may have compared to its alternative. However, educating physicians will empower them to make the conscious decision to prefer or not prefer a brand-name medication. With some generic medications shown to have a difference in bioequivalence compared to their brand-name counterparts, a physician may find more success prescribing the brand-name medications, regardless of pharmaceutical company influence, which is an alternative solution to policy changes that eliminate samples entirely. Although this study found insufficient evidence that removing samples decreases brand-name medication prescriptions, it is imperative that solutions are established to reduce the country’s increasing burden of medical costs.

Possible shortfalls of this study include the short period of time between which prepolicy data and postpolicy data were collected. It is possible that providers did not have enough time to adjust their prescribing habits or that providers would not have changed a prescribing pattern or preference simply because of a policy change. Future studies could allow a time period greater than 2 years to compare prepolicy and postpolicy prescribing habits, or a future study might make comparisons of prescriber patterns at different institutions that have different policies. Another possible shortfall is that providers and patients were limited to those at the Department of Dermatology & Cutaneous Surgery at the USF Morsani COM. Although this study has found insufficient evidence of a difference in prescribing habits, it may be beneficial to conduct a larger study that encompasses multiple academic institutions with similar policy changes. Most importantly, this study only investigated the influence of in-office pharmaceutical samples on prescribing patterns. This study did not look at the many other ways in which providers may be influenced by pharmaceutical companies, which likely is a significant confounding variable in this study. Continued additional studies that specifically examine other methods through which providers may be influenced would be helpful in further examining the many ways in which physician prescription habits are influenced.

Conclusion

Changes in pharmaceutical policy in 2011 at USF Morsani COM specifically banned in-office samples. The totality of evidence in this study shows modest observational evidence of a change in the postpolicy odds relative to prepolicy odds, but the data also are compatible with no change between prescribing habits before and after the policy changes. Further study is needed to fully understand this relationship.

- Sondergaard J, Vach K, Kragstrup J, et al. Impact of pharmaceutical representative visits on GPs’ drug preferences. Fam Pract. 2009;26:204-209.

- Jelinek GA, Neate SL. The influence of the pharmaceutical industry in medicine. J Law Med. 2009;17:216-223.

- Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373-380.

- Coleman DL. Establishing policies for the relationship between industry and clinicians: lessons learned from two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2008;83:882-887.

- Coleman DL, Kazdin AE, Miller LA, et al. Guidelines for interactions between clinical faculty and the pharmaceutical industry: one medical school’s approach. Acad Med. 2006;81:154-160.

- Evans D, Hartung DM, Beasley D, et al. Breaking up is hard to do: lessons learned from a pharma-free practice transformation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:332-338.

- Davit BM, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, et al. Comparing generic and innovator drugs: a review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States Food and Drug Administration. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1583-1597.

- Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2514-2526.

- McCormack J, Chmelicek JT. Generic versus brand name: the other drug war. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:911.

- Borgheini G. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1578-1592.

- Garrison GD, Levin GM. Factors affecting prescribing of the newer antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:10-14.

- Rafique S, Sarwar W, Rashid A, et al. Influence of free drug samples on prescribing by physicians: a cross sectional survey. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:465-467.

- Alexander GC, Zhang J, Basu A. Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46:394-402.

- Hodges B. Interactions with the pharmaceutical industry: experiences and attitudes of psychiatry residents, interns and clerks. CMAJ. 1995;153:553-559.

- Brotzman GL, Mark DH. The effect on resident attitudes of regulatory policies regarding pharmaceutical representative activities. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:130-134.

- Keim SM, Sanders AB, Witzke DB, et al. Beliefs and practices of emergency medicine faculty and residents regarding professional interactions with the biomedical industry. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1576-1581.

- Thomson AN, Craig BJ, Barham PM. Attitudes of general practitioners in New Zealand to pharmaceutical representatives. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:220-223.

- Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA. 1995;273:1296-1298.

- Hurley MP, Stafford RS, Lane AT. Characterizing the relationship between free drug samples and prescription patterns for acne vulgaris and rosacea. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:487-493.

- Lexchin J. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: what does the literature say? CMAJ. 1993;149:1401-1407.

- Lieb K, Scheurich A. Contact between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry, their perceptions, and the effects on prescribing habits. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110130.

- Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, et al. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians’ prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000352.

- Fischer MA, Avorn J. Economic consequences of underuse of generic drugs: evidence from Medicaid and implications for prescription drug benefit plans. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1051-1064.

- Sacks CA, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS, et al. Medicare spending on brand-name combination medications vs their generic constituents. JAMA. 2018;320:650-656.

- Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA. 2006;295:429-433.

- Allan GM, Lexchin J, Wiebe N. Physician awareness of drug cost: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e283.

- Sondergaard J, Vach K, Kragstrup J, et al. Impact of pharmaceutical representative visits on GPs’ drug preferences. Fam Pract. 2009;26:204-209.

- Jelinek GA, Neate SL. The influence of the pharmaceutical industry in medicine. J Law Med. 2009;17:216-223.

- Wazana A. Physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: is a gift ever just a gift? JAMA. 2000;283:373-380.

- Coleman DL. Establishing policies for the relationship between industry and clinicians: lessons learned from two academic health centers. Acad Med. 2008;83:882-887.

- Coleman DL, Kazdin AE, Miller LA, et al. Guidelines for interactions between clinical faculty and the pharmaceutical industry: one medical school’s approach. Acad Med. 2006;81:154-160.

- Evans D, Hartung DM, Beasley D, et al. Breaking up is hard to do: lessons learned from a pharma-free practice transformation. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:332-338.

- Davit BM, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, et al. Comparing generic and innovator drugs: a review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States Food and Drug Administration. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:1583-1597.

- Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, et al. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2008;300:2514-2526.

- McCormack J, Chmelicek JT. Generic versus brand name: the other drug war. Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:911.

- Borgheini G. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25:1578-1592.

- Garrison GD, Levin GM. Factors affecting prescribing of the newer antidepressants. Ann Pharmacother. 2000;34:10-14.

- Rafique S, Sarwar W, Rashid A, et al. Influence of free drug samples on prescribing by physicians: a cross sectional survey. J Pak Med Assoc. 2017;67:465-467.

- Alexander GC, Zhang J, Basu A. Characteristics of patients receiving pharmaceutical samples and association between sample receipt and out-of-pocket prescription costs. Med Care. 2008;46:394-402.

- Hodges B. Interactions with the pharmaceutical industry: experiences and attitudes of psychiatry residents, interns and clerks. CMAJ. 1995;153:553-559.

- Brotzman GL, Mark DH. The effect on resident attitudes of regulatory policies regarding pharmaceutical representative activities. J Gen Intern Med. 1993;8:130-134.

- Keim SM, Sanders AB, Witzke DB, et al. Beliefs and practices of emergency medicine faculty and residents regarding professional interactions with the biomedical industry. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22:1576-1581.

- Thomson AN, Craig BJ, Barham PM. Attitudes of general practitioners in New Zealand to pharmaceutical representatives. Br J Gen Pract. 1994;44:220-223.

- Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA. 1995;273:1296-1298.

- Hurley MP, Stafford RS, Lane AT. Characterizing the relationship between free drug samples and prescription patterns for acne vulgaris and rosacea. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:487-493.

- Lexchin J. Interactions between physicians and the pharmaceutical industry: what does the literature say? CMAJ. 1993;149:1401-1407.

- Lieb K, Scheurich A. Contact between doctors and the pharmaceutical industry, their perceptions, and the effects on prescribing habits. PLoS One. 2014;9:e110130.

- Spurling GK, Mansfield PR, Montgomery BD, et al. Information from pharmaceutical companies and the quality, quantity, and cost of physicians’ prescribing: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7:e1000352.

- Fischer MA, Avorn J. Economic consequences of underuse of generic drugs: evidence from Medicaid and implications for prescription drug benefit plans. Health Serv Res. 2003;38:1051-1064.

- Sacks CA, Lee CC, Kesselheim AS, et al. Medicare spending on brand-name combination medications vs their generic constituents. JAMA. 2018;320:650-656.

- Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA. 2006;295:429-433.

- Allan GM, Lexchin J, Wiebe N. Physician awareness of drug cost: a systematic review. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e283.

Practice Points

- There has been growing concern that pharmaceutical interactions and incentives can influence physicians’ prescribing habits.

- Many academic centers have adopted policies that attempt to limit the pharmaceutical industry’s influence on faculty and in-training physicians.

- This study aimed to investigate if there was a change in the prescribing habits of academic dermatologists after the medical school implemented new policies that banned in-office samples.

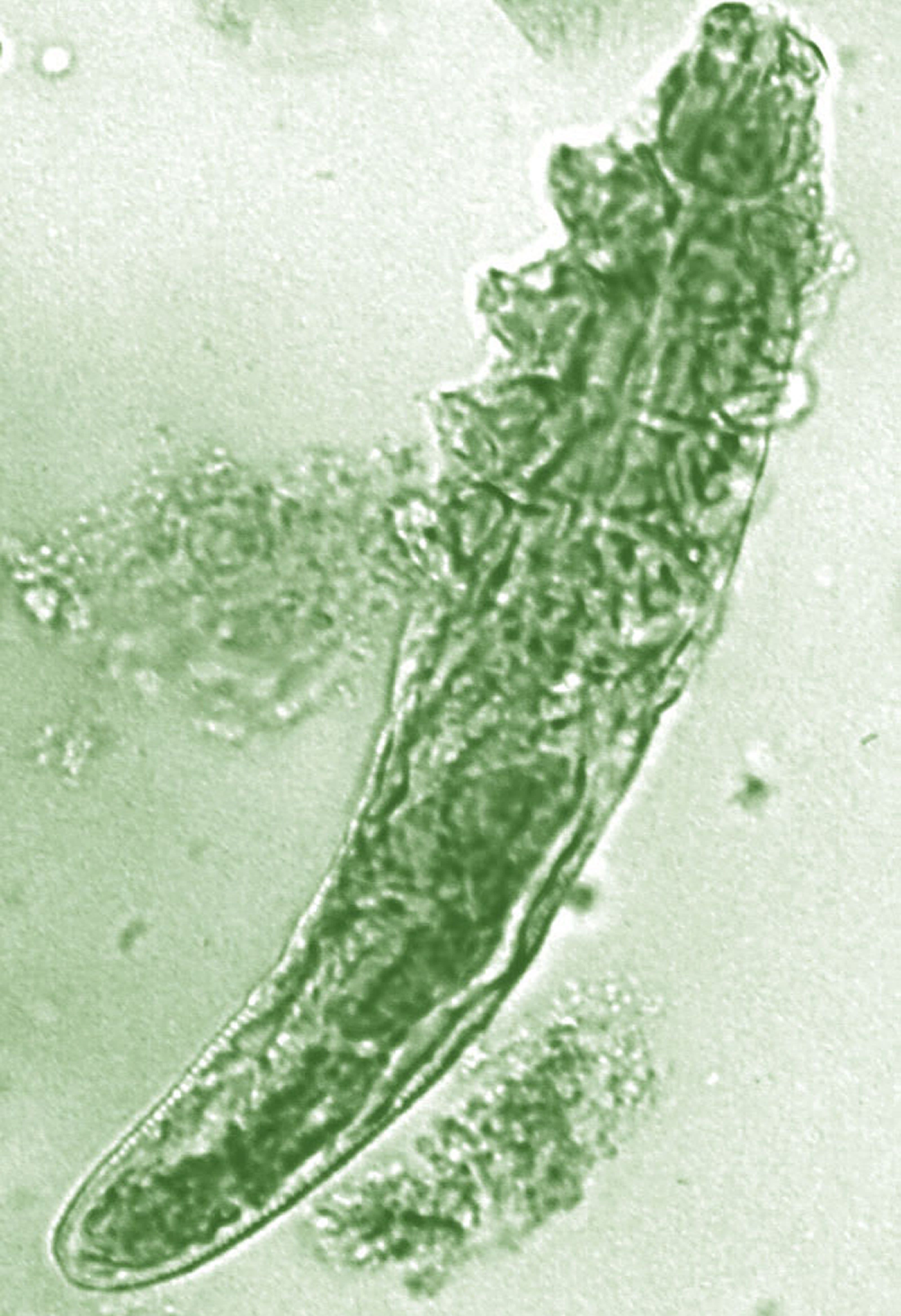

Topical benzyl benzoate–based treatment reduced Demodex in patients with rosacea

Daily treatment with benzyl benzoate (BB) cream reduced Demodex densities in patients with and without rosacea, and was associated with improvement in clinical signs, according to F.M.N. Forton, MD, of the Dermatology Clinic, Brussels, and his coauthor in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The retrospective study comprised 394 patients treated between 2002 and 2010; 117 of them had rosacea with papulopustules and the remainder only demodicosis. Their mean age was 49 years; most (278) were women. They had been treated with one of three doses of BB cream with crotamiton 10% cream: crotamiton applied in the morning, and BB 12% plus crotamiton in the evening; BB 12% plus crotamiton applied twice daily; and BB 20%-24% plus crotamiton applied once in the evening. Demodex densities (Dds) were measured with two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies and deep biopsies at baseline and follow-up. Symptoms were measured with an investigator global assessment (IGA).

The authors said they had previously found that BB had acaricidal effects on Demodex, as did crotamiton “to a lesser extent,” but that the two treatments have not been well studied. They also referred to the increasing evidence that Demodex has a role in papulopustular rosacea, and that ivermectin, which is acaricidal, is recommended for topical treatment of papulopustular rosacea.

In the study, a mean of 2.7 months after starting treatment, mean Dds were significantly lower for the entire cohort, decreasing by 72.4% (plus or minus 2.6%) from baseline. Dds had normalized in 35% of patients, and in 31% of patients, symptoms had cleared.

Treatment was considered effective in 46% of patients and curative in 20%. Men responded slightly better, with clearance in 34% vs. 20% of women. The two regimens using the higher dose of BB were more effective than those using the lower dose and were associated with better compliance. Compliance overall was 77%.

After a mean of nearly 3 months of treatment, “topical application of BB (with crotamiton) was effective at reducing Dds and clearing clinical symptoms, not only in demodicosis but also in rosacea with papulopustules, indirectly supporting a key role of the mite in the pathophysiology of rosacea,” the authors concluded.

Neither of these products are approved in the United States for treating rosacea.

Dr. Forton disclosed that he occasionally works as a consultant for Galderma; the second author had no disclosures. The study had no funding source.

Source: Forton FMN et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Sep 7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15938.

Daily treatment with benzyl benzoate (BB) cream reduced Demodex densities in patients with and without rosacea, and was associated with improvement in clinical signs, according to F.M.N. Forton, MD, of the Dermatology Clinic, Brussels, and his coauthor in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The retrospective study comprised 394 patients treated between 2002 and 2010; 117 of them had rosacea with papulopustules and the remainder only demodicosis. Their mean age was 49 years; most (278) were women. They had been treated with one of three doses of BB cream with crotamiton 10% cream: crotamiton applied in the morning, and BB 12% plus crotamiton in the evening; BB 12% plus crotamiton applied twice daily; and BB 20%-24% plus crotamiton applied once in the evening. Demodex densities (Dds) were measured with two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies and deep biopsies at baseline and follow-up. Symptoms were measured with an investigator global assessment (IGA).

The authors said they had previously found that BB had acaricidal effects on Demodex, as did crotamiton “to a lesser extent,” but that the two treatments have not been well studied. They also referred to the increasing evidence that Demodex has a role in papulopustular rosacea, and that ivermectin, which is acaricidal, is recommended for topical treatment of papulopustular rosacea.

In the study, a mean of 2.7 months after starting treatment, mean Dds were significantly lower for the entire cohort, decreasing by 72.4% (plus or minus 2.6%) from baseline. Dds had normalized in 35% of patients, and in 31% of patients, symptoms had cleared.

Treatment was considered effective in 46% of patients and curative in 20%. Men responded slightly better, with clearance in 34% vs. 20% of women. The two regimens using the higher dose of BB were more effective than those using the lower dose and were associated with better compliance. Compliance overall was 77%.

After a mean of nearly 3 months of treatment, “topical application of BB (with crotamiton) was effective at reducing Dds and clearing clinical symptoms, not only in demodicosis but also in rosacea with papulopustules, indirectly supporting a key role of the mite in the pathophysiology of rosacea,” the authors concluded.

Neither of these products are approved in the United States for treating rosacea.

Dr. Forton disclosed that he occasionally works as a consultant for Galderma; the second author had no disclosures. The study had no funding source.

Source: Forton FMN et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Sep 7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15938.

Daily treatment with benzyl benzoate (BB) cream reduced Demodex densities in patients with and without rosacea, and was associated with improvement in clinical signs, according to F.M.N. Forton, MD, of the Dermatology Clinic, Brussels, and his coauthor in the Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

The retrospective study comprised 394 patients treated between 2002 and 2010; 117 of them had rosacea with papulopustules and the remainder only demodicosis. Their mean age was 49 years; most (278) were women. They had been treated with one of three doses of BB cream with crotamiton 10% cream: crotamiton applied in the morning, and BB 12% plus crotamiton in the evening; BB 12% plus crotamiton applied twice daily; and BB 20%-24% plus crotamiton applied once in the evening. Demodex densities (Dds) were measured with two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies and deep biopsies at baseline and follow-up. Symptoms were measured with an investigator global assessment (IGA).

The authors said they had previously found that BB had acaricidal effects on Demodex, as did crotamiton “to a lesser extent,” but that the two treatments have not been well studied. They also referred to the increasing evidence that Demodex has a role in papulopustular rosacea, and that ivermectin, which is acaricidal, is recommended for topical treatment of papulopustular rosacea.

In the study, a mean of 2.7 months after starting treatment, mean Dds were significantly lower for the entire cohort, decreasing by 72.4% (plus or minus 2.6%) from baseline. Dds had normalized in 35% of patients, and in 31% of patients, symptoms had cleared.

Treatment was considered effective in 46% of patients and curative in 20%. Men responded slightly better, with clearance in 34% vs. 20% of women. The two regimens using the higher dose of BB were more effective than those using the lower dose and were associated with better compliance. Compliance overall was 77%.

After a mean of nearly 3 months of treatment, “topical application of BB (with crotamiton) was effective at reducing Dds and clearing clinical symptoms, not only in demodicosis but also in rosacea with papulopustules, indirectly supporting a key role of the mite in the pathophysiology of rosacea,” the authors concluded.

Neither of these products are approved in the United States for treating rosacea.

Dr. Forton disclosed that he occasionally works as a consultant for Galderma; the second author had no disclosures. The study had no funding source.

Source: Forton FMN et al. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019 Sep 7. doi: 10.1111/jdv.15938.

FROM JEADV

‘Recognizing Redness’

The National Rosacea Society has released a booklet for patients called “Recognizing Redness” to help them assess their complexion before and after a rosacea flare or treatment, as well as better understand their disease, according to a release from the society. The booklet contains a redness register that lets patients compare their skin’s natural redness with that of areas affected by their rosacea; it also contains information about the disease, its diagnosis, and common triggers. The booklet is freely available on the society’s website www.rosacea.org/patients/recognizing-redness-patient-guide-rosacea. It can also be provided in bulk to health care providers and acquired directly by writing the National Rosacea Society, 196 James Street, Barrington, IL 60010, calling the society toll-free at 1-888-NO-BLUSH, or via e-mail at rosaceas@aol.com. The new booklet was made possible by support from Aclaris.

The National Rosacea Society has released a booklet for patients called “Recognizing Redness” to help them assess their complexion before and after a rosacea flare or treatment, as well as better understand their disease, according to a release from the society. The booklet contains a redness register that lets patients compare their skin’s natural redness with that of areas affected by their rosacea; it also contains information about the disease, its diagnosis, and common triggers. The booklet is freely available on the society’s website www.rosacea.org/patients/recognizing-redness-patient-guide-rosacea. It can also be provided in bulk to health care providers and acquired directly by writing the National Rosacea Society, 196 James Street, Barrington, IL 60010, calling the society toll-free at 1-888-NO-BLUSH, or via e-mail at rosaceas@aol.com. The new booklet was made possible by support from Aclaris.

The National Rosacea Society has released a booklet for patients called “Recognizing Redness” to help them assess their complexion before and after a rosacea flare or treatment, as well as better understand their disease, according to a release from the society. The booklet contains a redness register that lets patients compare their skin’s natural redness with that of areas affected by their rosacea; it also contains information about the disease, its diagnosis, and common triggers. The booklet is freely available on the society’s website www.rosacea.org/patients/recognizing-redness-patient-guide-rosacea. It can also be provided in bulk to health care providers and acquired directly by writing the National Rosacea Society, 196 James Street, Barrington, IL 60010, calling the society toll-free at 1-888-NO-BLUSH, or via e-mail at rosaceas@aol.com. The new booklet was made possible by support from Aclaris.

Establishing the Diagnosis of Rosacea in Skin of Color Patients

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory cutaneous disorder that affects the vasculature and pilosebaceous units of the face. Delayed and misdiagnosed rosacea in the SOC population has led to increased morbidity in this patient population. 1-3 It is characterized by facial flushing and warmth, erythema, telangiectasia, papules, and pustules. The 4 major subtypes include erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous, and ocular rosacea. 4 Granulomatous rosacea is considered to be a unique variant of rosacea. Until recently, rosacea was thought to predominately affect lighter-skinned individuals of Celtic and northern European origin. 5,6 A paucity of studies and case reports in the literature have contributed to the commonly held belief that rosacea occurs infrequently in patients with skin of color (SOC). 1 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE revealed 32 results using the terms skin of color and rosacea vs 3786 using the term rosacea alone. It is possible that the nuance involved in appreciating erythema or other clinical manifestations of rosacea in SOC patients has led to underdiagnosis. Alternatively, these patients may be unaware that their symptoms represent a disease process and do not seek treatment. Many patients with darker skin will have endured rosacea for months or even years because the disease has been unrecognized or misdiagnosed. 6-8 Another factor possibly accounting for the perception that rosacea occurs infrequently in patients with SOC is misdiagnosis of rosacea as other diseases that are known to occur more commonly in the SOC population. Dermatologists should be aware that rosacea can affect SOC patients and that there are several rosacea mimickers to be considered and excluded when making the rosacea diagnosis in this patient population. To promote accurate and timely diagnosis of rosacea, we review several possible rosacea mimickers in SOC patients and highlight the distinguishing features.

Epidemiology

In 2018, a meta-analysis of published studies on rosacea estimated the global prevalence in all adults to be 5.46%.9 A multicenter study across 6 cities in Colombia identified 291 outpatients with rosacea; of them, 12.4% had either Fitzpatrick skin types IV or V.10 A study of 2743 Angolan adults with Fitzpatrick skin types V and VI reported that only 0.4% of patients had a diagnosis of rosacea.11 A Saudi study of 50 dark-skinned female patients with rosacea revealed 40% (20/50), 18% (9/50), and 42% (21/50) were Fitzpatrick skin types IV, V, and VI, respectively.12 The prevalence of rosacea in SOC patients in the United States is less defined. Data from the US National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (1993-2010) of 31.5 million rosacea visits showed that 2% of rosacea patients were black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.8