User login

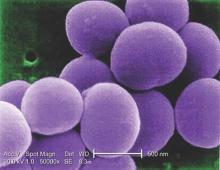

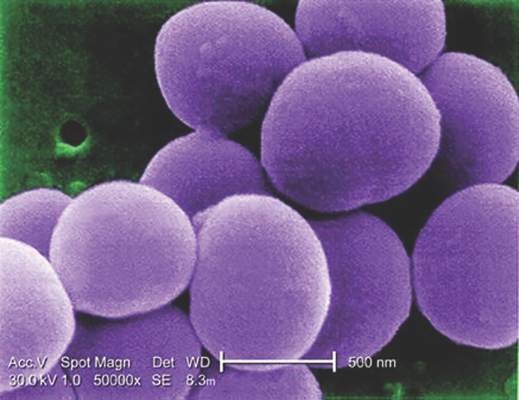

Glucocorticoids increase risk of S. aureus bacteremia

Use of systemic glucocorticoids significantly increased risk for community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB) in a dose-dependent fashion, based on data from a large Danish registry.

On average, current users of systemic glucocorticoids had an adjusted 2.5-fold increased risk of CA-SAB, compared with nonusers. The risk was most pronounced in long-term users of glucocorticoids, including patients with connective tissue disease and patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Among new users of glucocorticoids, the risk of CA-SAB was highest for patients with cancer, in the retrospective, case-control study published by Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Dr. Jesper Smit of Aalborg (Denmark) University and his colleagues, looked at all 2,638 patients admitted with first-time CA-SAB and 26,379 matched population controls in Northern Denmark medical databases between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2011.

New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Risk of CA-SAB rose in a dose-dependent fashion as 90-day cumulative doses increased. For subjects taking a cumulative dose of 150 mg or less, the adjusted OR for CA-SAB was 1.3. At a cumulative dose of 500-1000 mg, OR rose to 2.4. At a cumulative dose greater than 1000 mg, OR was 6.2.

Risk did not differ based on individuals’ sex, age group, or the severity of any comorbidity.

“This is the first study to specifically investigate whether the use of glucocorticoids is associated with increased risk of CA-SAB,” the authors concluded, adding that “these results extend the current knowledge of risk factors for CA-SAB and may serve as a reminder for clinicians to carefully weigh the elevated risk against the potential beneficial effect of glucocorticoid therapy, particularly in patients with concomitant CA-SAB risk factors.”

This study was supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Use of systemic glucocorticoids significantly increased risk for community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB) in a dose-dependent fashion, based on data from a large Danish registry.

On average, current users of systemic glucocorticoids had an adjusted 2.5-fold increased risk of CA-SAB, compared with nonusers. The risk was most pronounced in long-term users of glucocorticoids, including patients with connective tissue disease and patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Among new users of glucocorticoids, the risk of CA-SAB was highest for patients with cancer, in the retrospective, case-control study published by Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Dr. Jesper Smit of Aalborg (Denmark) University and his colleagues, looked at all 2,638 patients admitted with first-time CA-SAB and 26,379 matched population controls in Northern Denmark medical databases between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2011.

New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Risk of CA-SAB rose in a dose-dependent fashion as 90-day cumulative doses increased. For subjects taking a cumulative dose of 150 mg or less, the adjusted OR for CA-SAB was 1.3. At a cumulative dose of 500-1000 mg, OR rose to 2.4. At a cumulative dose greater than 1000 mg, OR was 6.2.

Risk did not differ based on individuals’ sex, age group, or the severity of any comorbidity.

“This is the first study to specifically investigate whether the use of glucocorticoids is associated with increased risk of CA-SAB,” the authors concluded, adding that “these results extend the current knowledge of risk factors for CA-SAB and may serve as a reminder for clinicians to carefully weigh the elevated risk against the potential beneficial effect of glucocorticoid therapy, particularly in patients with concomitant CA-SAB risk factors.”

This study was supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

Use of systemic glucocorticoids significantly increased risk for community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB) in a dose-dependent fashion, based on data from a large Danish registry.

On average, current users of systemic glucocorticoids had an adjusted 2.5-fold increased risk of CA-SAB, compared with nonusers. The risk was most pronounced in long-term users of glucocorticoids, including patients with connective tissue disease and patients with chronic pulmonary disease. Among new users of glucocorticoids, the risk of CA-SAB was highest for patients with cancer, in the retrospective, case-control study published by Mayo Clinic Proceedings.

Dr. Jesper Smit of Aalborg (Denmark) University and his colleagues, looked at all 2,638 patients admitted with first-time CA-SAB and 26,379 matched population controls in Northern Denmark medical databases between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2011.

New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Risk of CA-SAB rose in a dose-dependent fashion as 90-day cumulative doses increased. For subjects taking a cumulative dose of 150 mg or less, the adjusted OR for CA-SAB was 1.3. At a cumulative dose of 500-1000 mg, OR rose to 2.4. At a cumulative dose greater than 1000 mg, OR was 6.2.

Risk did not differ based on individuals’ sex, age group, or the severity of any comorbidity.

“This is the first study to specifically investigate whether the use of glucocorticoids is associated with increased risk of CA-SAB,” the authors concluded, adding that “these results extend the current knowledge of risk factors for CA-SAB and may serve as a reminder for clinicians to carefully weigh the elevated risk against the potential beneficial effect of glucocorticoid therapy, particularly in patients with concomitant CA-SAB risk factors.”

This study was supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

FROM MAYO CLINIC PROCEEDINGS

Key clinical point: Taking glucocorticoids can significantly increase the risk of contracting community-acquired Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia (CA-SAB).

Major finding: New glucocorticoid users had an odds ratio for CA-SAB of 2.7, slightly higher than the OR of 2.3 for long-term users. Former glucocorticoid users had a considerably lower OR for CA-SAB of 1.3.

Data source: Retrospective, case-control study of all adults with first-time CA-SAB in Northern Denmark medical registries between 2000 and 2011.

Disclosures: Study supported by grants from Heinrich Kopp, Hertha Christensen, and North Denmark Health Sciences Research foundation. The authors did not report any relevant financial disclosures.

VIDEO: EULAR guidance on DMARD use in RA made ‘more concise’

LONDON – The European League Against Rheumatism guidelines on the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis have been updated in line with current evidence and made more concise.

Dr. Josef S. Smolen of the department of rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna who presented the 2016 guidelines at the European Congress of Rheumatology, noted that they now consist of 12 rather than the 14 recommendations that were included in the 2013 update (Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492-509) and the 15 recommendations that were in the original 2010 version.

These 12 recommendations cover treatment targets and general approaches in the management of rheumatoid arthritis that incorporate disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and the use of glucocorticoids, and present treatment options as a hierarchy to help guide clinicians through appropriate procedures when initial and subsequent treatment fails. All DMARDs are considered in the recommendations, from the long-standing conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs, such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide, and the newer biologic DMARDs, such as the anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–targeting drugs, to the newer biosimilar DMARDs, and targeted synthetic (ts)DMARDS, such as the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors tofacitinib and baricitinib.

The recommendations have been developed in accordance with EULAR’s standard operating procedure for the development of guidelines, Dr. Smolen observed, and involved three systematic literature reviews and expert opinion garnered from a task force of 50 experts and patients.

“This was the largest task force I have ever convened,” Dr. Smolen said, noting that rheumatologists from outside Europe had been invited to contribute their expertise and knowledge for the first time. Altogether 42 rheumatologists, three clinical fellows, two health professionals, and three patients were involved in revising the recommendations.

There are now four rather than three overarching principles, two of which are shared with early inflammatory arthritis recommendations that were also presented at the congress. The first two principles state that shared decision making is key to optimizing care and that rheumatologists should be the primary specialists looking after patients. The third principle recognizes the high burden that RA can have not only on an individual level but also on health care systems and society in general, which rheumatologists should be aware of. The fourth and final principle states that treatment decisions should be based on patients’ disease activity but that other factors, such as patients’ age, risk for progression, coexisting disease, and likely tolerance of treatment should also be kept in mind.

In an interview, Dr. Smolen highlighted that the EULAR recommendations cover three main phases of DMARD treatment: First is the DMARD-naive group of patients, who may be at an early or late stage of their disease. Second is the group in whom initial treatment has failed, and third is the group for whom subsequent treatment has not worked.

“In all these phases, we have some changes,” Dr. Smolen said. As an example, he noted that in the DMARD-naive setting, the use of csDMARDs has always been recommended but that the prior advice to consider combination csDMARD treatment has been edited out.

“We now say methotrexate should be part of the first treatment strategy, and the treatment strategy encompasses the use of additional, at least conventional synthetic, DMARDs.” Glucocorticoids are also more strongly recommended as part of the initial treatment strategy in combination with methotrexate, he said, although there is the proviso to use these for as short a time as possible.

In situations where patients do not respond to methotrexate plus glucocorticoids or they cannot tolerate methotrexate, then the recommendations advise stratifying patients into two groups. Those with poor prognostic factors might be switched to a biologic therapy, such as an anti-TNF agent or a tsDMARD. In regard to the latter, there is now more evidence behind the use of JAK inhibitors, notably tofacitinib, Dr. Smolen observed. Biologic DMARDs should be combined with csDMARDs, but if the latter is not tolerated then there is the option to use an IL-6 pathway inhibitor.

“There is now compelling evidence that all biologic DMARDs, including tocilizumab, convey better clinical, functional, and structural outcomes in combination with conventional synthetic DMARDs, especially methotrexate,” Dr. Smolen observed during his presentation of the recommendations. This may not be the case for the JAK inhibitors based on the current evidence.

When asked how the EULAR recommendations match up to those issued earlier this year by the American College of Rheumatology (Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1-25), Dr. Smolen observed that the two had become “much closer.” There remain differences in recommendations on glucocorticoid use, which are “somewhat clearer” in the European than in the American guidelines, and EULAR proposes combining biologic DMARDs with csDMARDs rather than using them as monotherapy. The EULAR recommendations also do not distinguish patients by disease duration but by treatment phase, and use prognostic factors for stratification.

The recommendations are currently in draft format and once finalized they will be published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and also made freely available via the EULAR website, joining the organization’s many other recommendations for the management of rheumatic diseases. Dr. Smolen noted that these are intended as a template to provide national societies, health systems, and regulatory bodies a guide to the best evidence-based use of DMARDS in RA throughout Europe.

Dr. Smolen has received grant support and/or honoraria for consultations and/or for presentations from: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Astro-Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, ILTOO Pharma, Janssen, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis-Sandoz, Pfizer, Roche-Chugai, Samsung, and UCB.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LONDON – The European League Against Rheumatism guidelines on the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis have been updated in line with current evidence and made more concise.

Dr. Josef S. Smolen of the department of rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna who presented the 2016 guidelines at the European Congress of Rheumatology, noted that they now consist of 12 rather than the 14 recommendations that were included in the 2013 update (Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492-509) and the 15 recommendations that were in the original 2010 version.

These 12 recommendations cover treatment targets and general approaches in the management of rheumatoid arthritis that incorporate disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and the use of glucocorticoids, and present treatment options as a hierarchy to help guide clinicians through appropriate procedures when initial and subsequent treatment fails. All DMARDs are considered in the recommendations, from the long-standing conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs, such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide, and the newer biologic DMARDs, such as the anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–targeting drugs, to the newer biosimilar DMARDs, and targeted synthetic (ts)DMARDS, such as the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors tofacitinib and baricitinib.

The recommendations have been developed in accordance with EULAR’s standard operating procedure for the development of guidelines, Dr. Smolen observed, and involved three systematic literature reviews and expert opinion garnered from a task force of 50 experts and patients.

“This was the largest task force I have ever convened,” Dr. Smolen said, noting that rheumatologists from outside Europe had been invited to contribute their expertise and knowledge for the first time. Altogether 42 rheumatologists, three clinical fellows, two health professionals, and three patients were involved in revising the recommendations.

There are now four rather than three overarching principles, two of which are shared with early inflammatory arthritis recommendations that were also presented at the congress. The first two principles state that shared decision making is key to optimizing care and that rheumatologists should be the primary specialists looking after patients. The third principle recognizes the high burden that RA can have not only on an individual level but also on health care systems and society in general, which rheumatologists should be aware of. The fourth and final principle states that treatment decisions should be based on patients’ disease activity but that other factors, such as patients’ age, risk for progression, coexisting disease, and likely tolerance of treatment should also be kept in mind.

In an interview, Dr. Smolen highlighted that the EULAR recommendations cover three main phases of DMARD treatment: First is the DMARD-naive group of patients, who may be at an early or late stage of their disease. Second is the group in whom initial treatment has failed, and third is the group for whom subsequent treatment has not worked.

“In all these phases, we have some changes,” Dr. Smolen said. As an example, he noted that in the DMARD-naive setting, the use of csDMARDs has always been recommended but that the prior advice to consider combination csDMARD treatment has been edited out.

“We now say methotrexate should be part of the first treatment strategy, and the treatment strategy encompasses the use of additional, at least conventional synthetic, DMARDs.” Glucocorticoids are also more strongly recommended as part of the initial treatment strategy in combination with methotrexate, he said, although there is the proviso to use these for as short a time as possible.

In situations where patients do not respond to methotrexate plus glucocorticoids or they cannot tolerate methotrexate, then the recommendations advise stratifying patients into two groups. Those with poor prognostic factors might be switched to a biologic therapy, such as an anti-TNF agent or a tsDMARD. In regard to the latter, there is now more evidence behind the use of JAK inhibitors, notably tofacitinib, Dr. Smolen observed. Biologic DMARDs should be combined with csDMARDs, but if the latter is not tolerated then there is the option to use an IL-6 pathway inhibitor.

“There is now compelling evidence that all biologic DMARDs, including tocilizumab, convey better clinical, functional, and structural outcomes in combination with conventional synthetic DMARDs, especially methotrexate,” Dr. Smolen observed during his presentation of the recommendations. This may not be the case for the JAK inhibitors based on the current evidence.

When asked how the EULAR recommendations match up to those issued earlier this year by the American College of Rheumatology (Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1-25), Dr. Smolen observed that the two had become “much closer.” There remain differences in recommendations on glucocorticoid use, which are “somewhat clearer” in the European than in the American guidelines, and EULAR proposes combining biologic DMARDs with csDMARDs rather than using them as monotherapy. The EULAR recommendations also do not distinguish patients by disease duration but by treatment phase, and use prognostic factors for stratification.

The recommendations are currently in draft format and once finalized they will be published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and also made freely available via the EULAR website, joining the organization’s many other recommendations for the management of rheumatic diseases. Dr. Smolen noted that these are intended as a template to provide national societies, health systems, and regulatory bodies a guide to the best evidence-based use of DMARDS in RA throughout Europe.

Dr. Smolen has received grant support and/or honoraria for consultations and/or for presentations from: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Astro-Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, ILTOO Pharma, Janssen, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis-Sandoz, Pfizer, Roche-Chugai, Samsung, and UCB.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LONDON – The European League Against Rheumatism guidelines on the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis have been updated in line with current evidence and made more concise.

Dr. Josef S. Smolen of the department of rheumatology at the Medical University of Vienna who presented the 2016 guidelines at the European Congress of Rheumatology, noted that they now consist of 12 rather than the 14 recommendations that were included in the 2013 update (Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:492-509) and the 15 recommendations that were in the original 2010 version.

These 12 recommendations cover treatment targets and general approaches in the management of rheumatoid arthritis that incorporate disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) and the use of glucocorticoids, and present treatment options as a hierarchy to help guide clinicians through appropriate procedures when initial and subsequent treatment fails. All DMARDs are considered in the recommendations, from the long-standing conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs, such as methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and leflunomide, and the newer biologic DMARDs, such as the anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–targeting drugs, to the newer biosimilar DMARDs, and targeted synthetic (ts)DMARDS, such as the Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors tofacitinib and baricitinib.

The recommendations have been developed in accordance with EULAR’s standard operating procedure for the development of guidelines, Dr. Smolen observed, and involved three systematic literature reviews and expert opinion garnered from a task force of 50 experts and patients.

“This was the largest task force I have ever convened,” Dr. Smolen said, noting that rheumatologists from outside Europe had been invited to contribute their expertise and knowledge for the first time. Altogether 42 rheumatologists, three clinical fellows, two health professionals, and three patients were involved in revising the recommendations.

There are now four rather than three overarching principles, two of which are shared with early inflammatory arthritis recommendations that were also presented at the congress. The first two principles state that shared decision making is key to optimizing care and that rheumatologists should be the primary specialists looking after patients. The third principle recognizes the high burden that RA can have not only on an individual level but also on health care systems and society in general, which rheumatologists should be aware of. The fourth and final principle states that treatment decisions should be based on patients’ disease activity but that other factors, such as patients’ age, risk for progression, coexisting disease, and likely tolerance of treatment should also be kept in mind.

In an interview, Dr. Smolen highlighted that the EULAR recommendations cover three main phases of DMARD treatment: First is the DMARD-naive group of patients, who may be at an early or late stage of their disease. Second is the group in whom initial treatment has failed, and third is the group for whom subsequent treatment has not worked.

“In all these phases, we have some changes,” Dr. Smolen said. As an example, he noted that in the DMARD-naive setting, the use of csDMARDs has always been recommended but that the prior advice to consider combination csDMARD treatment has been edited out.

“We now say methotrexate should be part of the first treatment strategy, and the treatment strategy encompasses the use of additional, at least conventional synthetic, DMARDs.” Glucocorticoids are also more strongly recommended as part of the initial treatment strategy in combination with methotrexate, he said, although there is the proviso to use these for as short a time as possible.

In situations where patients do not respond to methotrexate plus glucocorticoids or they cannot tolerate methotrexate, then the recommendations advise stratifying patients into two groups. Those with poor prognostic factors might be switched to a biologic therapy, such as an anti-TNF agent or a tsDMARD. In regard to the latter, there is now more evidence behind the use of JAK inhibitors, notably tofacitinib, Dr. Smolen observed. Biologic DMARDs should be combined with csDMARDs, but if the latter is not tolerated then there is the option to use an IL-6 pathway inhibitor.

“There is now compelling evidence that all biologic DMARDs, including tocilizumab, convey better clinical, functional, and structural outcomes in combination with conventional synthetic DMARDs, especially methotrexate,” Dr. Smolen observed during his presentation of the recommendations. This may not be the case for the JAK inhibitors based on the current evidence.

When asked how the EULAR recommendations match up to those issued earlier this year by the American College of Rheumatology (Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68:1-25), Dr. Smolen observed that the two had become “much closer.” There remain differences in recommendations on glucocorticoid use, which are “somewhat clearer” in the European than in the American guidelines, and EULAR proposes combining biologic DMARDs with csDMARDs rather than using them as monotherapy. The EULAR recommendations also do not distinguish patients by disease duration but by treatment phase, and use prognostic factors for stratification.

The recommendations are currently in draft format and once finalized they will be published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and also made freely available via the EULAR website, joining the organization’s many other recommendations for the management of rheumatic diseases. Dr. Smolen noted that these are intended as a template to provide national societies, health systems, and regulatory bodies a guide to the best evidence-based use of DMARDS in RA throughout Europe.

Dr. Smolen has received grant support and/or honoraria for consultations and/or for presentations from: AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Astro-Pharma, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, ILTOO Pharma, Janssen, Merck Serono, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis-Sandoz, Pfizer, Roche-Chugai, Samsung, and UCB.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE EULAR 2016 CONGRESS

Simplify cardiac risk assessment for rheumatologic conditions

LONDON – Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment for patients with rheumatic diseases can be simple and integrated into general practice or rheumatology clinics, experts said during an Outcomes Science Session at the European Congress of Rheumatology

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a 50% higher risk of heart disease than do their counterparts without the disease, but “just having RA on its own isn’t sufficient to render that individual at high risk,” Dr. Naveed Sattar, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow’s Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences in Scotland, said in an interview.

It’s simple enough to use traditional CVD risk factors in an RA population by including a patient’s age, gender, smoking status, and family history of heart disease, in addition to measuring blood pressure and blood lipid levels. Most risk scores will compile those features into a 10-year risk of a fatal CVD event. To account for the contribution of RA, Dr. Sattar said, simply multiply that score by 1.5.

While “there’s a fixation in some parts of Europe for [measuring] fasting lipids,” it is not necessary, Dr. Sattar said. The two lipid parameters that go in risk scores tend to be cholesterol and HDL cholesterol, he said, which change only minimally in fasting versus nonfasting states.

“The evidence overwhelmingly shows that nonfasting lipids, which can be done easily on the same sample as other clinic tests, are just as predictive of CVD risk as fasting lipids,” he said. “That really matters because many of our patients with RA or other conditions come to the hospital when they’re not fasting, and we shouldn’t be sending them away to come back fasting to do risk scores for CVD. That just doesn’t make sense.”

Updated guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and guidelines soon to be released from the European League Against Rheumatism suggest that risk scores can be calculated every 5 years for most patients, a change from previous recommendations to calculate risk annually. Risk scoring is not perfect, however, and there is some debate about whether additional blood tests or ultrasound scanning of the carotid artery could augment the ability to predict heart disease risk. “We’re not quite there yet,” Dr. Sattar said. “I think we should do the simple things first and do them well.”

CV risk raised in all inflammatory arthritic diseases

During the same session, Dr. Paola de Pablo of the University of Birmingham, England, focused on how immune-mediated diseases predispose to premature, accelerated atherosclerosis and subsequent increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Cardiovascular risk is not only elevated in those with RA, she observed, but also in those with systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, vasculitides, and inflammatory myopathies. The risk varies but as a rule is more than 50% higher than the rate seen in the general population.

The underlying mechanisms are not clear, but chronic inflammation is closely linked with atherosclerosis, which in turn ups the risk for myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident.

Despite treatment, the risk often remains, Dr. de Pablo said. She highlighted how treatment with methotrexate and anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha drugs in RA had been associated with a reduction in the risk for heart attack of 20% and 40%, respectively (Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;74:480–89) so targeting inflammation with these drugs may have positive effects, at least in RA.

Managing traditional cardiovascular risk factors remains important, Dr. de Pablo said. That was a sentiment echoed by Dr. Sattar and by rheumatologist Dr. Michael Nurmohamed of the VU Medical Center in Amsterdam. This includes controlling blood pressure with antihypertensive medications and blood lipids with statins, and advocating smoking cessation and perhaps other appropriate lifestyle changes such as increasing physical exercise and controlling weight.

Dr. Nurmohamed, who was involved in the 2015 update of the EULAR recommendations on cardiovascular risk management, noted that traditional risk factor management in patients with arthritis in current clinical practice is often poor and that strategies to address this were urgently needed.

Although treating to-target and preventing disease flares in the rheumatic diseases is important, it lowers but does not normalize cardiovascular risk. “This appears to be irrespective of the drug used,” Dr. Nurmohamed said. Rheumatologists need to be careful when tapering medication, particularly the biologics, as these are perhaps helping to temper cardiovascular inflammation, which could worsen when doses are reduced. “Antirheumatic treatment only is not good enough to decrease or normalize the cardiovascular risk of our patients”, he emphasized.

Norwegian project shows how to integrate CVD assessment into routine practice

In a separate presentation, Dr. Eirik Ikdahl, a PhD student at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo, discussed how some rheumatology clinics in Norway are successfully incorporating CVD risk screening.

Through the Norwegian Collaboration on Atherosclerotic disease in patients with Rheumatic joint diseases (NOCAR), which started in April 2014, annual cardiovascular disease risk evaluations of patients with inflammatory joint diseases are being implemented into the practices of 11 rheumatology outpatient clinics. While waiting for clinic appointments, patients are given electronic devices through which they can report CVD risk factors via an electronic patient journal program called GoTreatIt Rheuma. From there, the clinic can order nonfasting lipid measurements and nurses can record patients’ blood pressure.

Then, using the ESC Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) algorithm, the program automatically calculates a patient’s 10-year risk of a fatal CVD event. If the SCORE estimate is 5% or greater, the rheumatologist forwards a note to the patient’s primary care physician or cardiologist saying there is an indication for initiation of CVD-preventive measures such as medication or lifestyle changes. Rheumatologists and rheumatology nurses also deliver brief advice regarding smoking cessation and healthy diet.

“The main aim of the project is to raise awareness of the cardiovascular burden that these patients experience, and to ensure that patients with inflammatory joint diseases receive guideline-recommended cardiovascular preventive treatment,” Dr. Ikdahl said.

Of 6,150 patients defined as eligible for the NOCAR project in three of the centers, 41% (n = 2,519) received a CVD risk assessment during the first year and a half of the program, officers found in a recent review. Of those, 1,569 had RA, 418 had ankylosing spondylitis, 350 had psoriatic arthritis, and 122 had other spondyloarthritides.

Through the program, “a large number of high-risk patients have received screening that they would not otherwise have been offered,” Dr. Ikdahl said.

The major obstacles to successful implementation were time scarcity, defining a date for annual CVD risk assessment among patients who visit the clinics multiple times per year, and making sure lipids were measured before seeing the rheumatologist, he said. “We acknowledge there is room for improvement. It is challenging to implement new work tasks in an already busy rheumatology outpatient clinic, and since the project does not offer financial incentives to the participating centers, we rely on a collective effort and voluntary work based on resources already available.”

Remember CVD, but don’t forget other comorbidities

Other research presented by Dr. Laure Gossec, professor of rheumatology at Pitie-Salpétriere Hospital and Pierre & Marie Curie University in Paris highlighted the importance of identifying all comorbidities and their risk factors in patients with rheumatic diseases, and not just cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Gossec presented the results of an initiative aiming to make the collection and management of comorbidities easier in routine rheumatologic practice. The aim was to develop a simple, more pragmatic form that could be used to help rheumatologists manage selected comorbidities, and know when to refer for other specialist assessment. The focus was on ischemic cardiovascular disease, malignancies, infections such as chronic bronchitis, gastrointestinal disease such as diverticulitis, osteoporosis, and depression.

A committee of 18 experts, both physicians and nurses, was convened to examine the results of a systematic literature review of recommendations on comorbidity management and come up with concise recommendations for rheumatologists. Each of their recommendations covered whether or not the comorbidity was present (yes/no/don’t know) and if screening had been undertaken, such as measurement of blood lipids, and when this had occurred if known. There was then guidance on how to interpret these findings, calculate risk, and what to do if findings were abnormal.

The project is ongoing, and so far the expert panel has developed a pragmatic document with forms to help collect, report, and manage each specific comorbidity and its known risk factors. But it is still perhaps too long to be feasibly used in everyday practice, Dr. Gossec conceded. So the aim is to create a short, 2-page form that could summarize the recommendations briefly, and also develop a questionnaire for the patient to fill out and understand how to self-manage some comorbidities.

“We feel that this is a way to disseminate and adapt to the national context for France the EULAR comorbidities initiative,” Dr. Gossec said. “It also defines exactly what rheumatologists should be doing and when they should refer, hopefully to the benefit of our patients.”

Dr. Sattar has participated in advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lily and UCB. He has also consulted for Merck and is a member of Roche’s speakers’ bureau. Dr. de Paolo and Dr. Nurmohamed reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Ikdahl has received speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer. Dr. Gossec and coauthors have received honoraria from Abbvie France.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LONDON – Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment for patients with rheumatic diseases can be simple and integrated into general practice or rheumatology clinics, experts said during an Outcomes Science Session at the European Congress of Rheumatology

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a 50% higher risk of heart disease than do their counterparts without the disease, but “just having RA on its own isn’t sufficient to render that individual at high risk,” Dr. Naveed Sattar, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow’s Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences in Scotland, said in an interview.

It’s simple enough to use traditional CVD risk factors in an RA population by including a patient’s age, gender, smoking status, and family history of heart disease, in addition to measuring blood pressure and blood lipid levels. Most risk scores will compile those features into a 10-year risk of a fatal CVD event. To account for the contribution of RA, Dr. Sattar said, simply multiply that score by 1.5.

While “there’s a fixation in some parts of Europe for [measuring] fasting lipids,” it is not necessary, Dr. Sattar said. The two lipid parameters that go in risk scores tend to be cholesterol and HDL cholesterol, he said, which change only minimally in fasting versus nonfasting states.

“The evidence overwhelmingly shows that nonfasting lipids, which can be done easily on the same sample as other clinic tests, are just as predictive of CVD risk as fasting lipids,” he said. “That really matters because many of our patients with RA or other conditions come to the hospital when they’re not fasting, and we shouldn’t be sending them away to come back fasting to do risk scores for CVD. That just doesn’t make sense.”

Updated guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and guidelines soon to be released from the European League Against Rheumatism suggest that risk scores can be calculated every 5 years for most patients, a change from previous recommendations to calculate risk annually. Risk scoring is not perfect, however, and there is some debate about whether additional blood tests or ultrasound scanning of the carotid artery could augment the ability to predict heart disease risk. “We’re not quite there yet,” Dr. Sattar said. “I think we should do the simple things first and do them well.”

CV risk raised in all inflammatory arthritic diseases

During the same session, Dr. Paola de Pablo of the University of Birmingham, England, focused on how immune-mediated diseases predispose to premature, accelerated atherosclerosis and subsequent increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Cardiovascular risk is not only elevated in those with RA, she observed, but also in those with systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, vasculitides, and inflammatory myopathies. The risk varies but as a rule is more than 50% higher than the rate seen in the general population.

The underlying mechanisms are not clear, but chronic inflammation is closely linked with atherosclerosis, which in turn ups the risk for myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident.

Despite treatment, the risk often remains, Dr. de Pablo said. She highlighted how treatment with methotrexate and anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha drugs in RA had been associated with a reduction in the risk for heart attack of 20% and 40%, respectively (Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;74:480–89) so targeting inflammation with these drugs may have positive effects, at least in RA.

Managing traditional cardiovascular risk factors remains important, Dr. de Pablo said. That was a sentiment echoed by Dr. Sattar and by rheumatologist Dr. Michael Nurmohamed of the VU Medical Center in Amsterdam. This includes controlling blood pressure with antihypertensive medications and blood lipids with statins, and advocating smoking cessation and perhaps other appropriate lifestyle changes such as increasing physical exercise and controlling weight.

Dr. Nurmohamed, who was involved in the 2015 update of the EULAR recommendations on cardiovascular risk management, noted that traditional risk factor management in patients with arthritis in current clinical practice is often poor and that strategies to address this were urgently needed.

Although treating to-target and preventing disease flares in the rheumatic diseases is important, it lowers but does not normalize cardiovascular risk. “This appears to be irrespective of the drug used,” Dr. Nurmohamed said. Rheumatologists need to be careful when tapering medication, particularly the biologics, as these are perhaps helping to temper cardiovascular inflammation, which could worsen when doses are reduced. “Antirheumatic treatment only is not good enough to decrease or normalize the cardiovascular risk of our patients”, he emphasized.

Norwegian project shows how to integrate CVD assessment into routine practice

In a separate presentation, Dr. Eirik Ikdahl, a PhD student at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo, discussed how some rheumatology clinics in Norway are successfully incorporating CVD risk screening.

Through the Norwegian Collaboration on Atherosclerotic disease in patients with Rheumatic joint diseases (NOCAR), which started in April 2014, annual cardiovascular disease risk evaluations of patients with inflammatory joint diseases are being implemented into the practices of 11 rheumatology outpatient clinics. While waiting for clinic appointments, patients are given electronic devices through which they can report CVD risk factors via an electronic patient journal program called GoTreatIt Rheuma. From there, the clinic can order nonfasting lipid measurements and nurses can record patients’ blood pressure.

Then, using the ESC Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) algorithm, the program automatically calculates a patient’s 10-year risk of a fatal CVD event. If the SCORE estimate is 5% or greater, the rheumatologist forwards a note to the patient’s primary care physician or cardiologist saying there is an indication for initiation of CVD-preventive measures such as medication or lifestyle changes. Rheumatologists and rheumatology nurses also deliver brief advice regarding smoking cessation and healthy diet.

“The main aim of the project is to raise awareness of the cardiovascular burden that these patients experience, and to ensure that patients with inflammatory joint diseases receive guideline-recommended cardiovascular preventive treatment,” Dr. Ikdahl said.

Of 6,150 patients defined as eligible for the NOCAR project in three of the centers, 41% (n = 2,519) received a CVD risk assessment during the first year and a half of the program, officers found in a recent review. Of those, 1,569 had RA, 418 had ankylosing spondylitis, 350 had psoriatic arthritis, and 122 had other spondyloarthritides.

Through the program, “a large number of high-risk patients have received screening that they would not otherwise have been offered,” Dr. Ikdahl said.

The major obstacles to successful implementation were time scarcity, defining a date for annual CVD risk assessment among patients who visit the clinics multiple times per year, and making sure lipids were measured before seeing the rheumatologist, he said. “We acknowledge there is room for improvement. It is challenging to implement new work tasks in an already busy rheumatology outpatient clinic, and since the project does not offer financial incentives to the participating centers, we rely on a collective effort and voluntary work based on resources already available.”

Remember CVD, but don’t forget other comorbidities

Other research presented by Dr. Laure Gossec, professor of rheumatology at Pitie-Salpétriere Hospital and Pierre & Marie Curie University in Paris highlighted the importance of identifying all comorbidities and their risk factors in patients with rheumatic diseases, and not just cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Gossec presented the results of an initiative aiming to make the collection and management of comorbidities easier in routine rheumatologic practice. The aim was to develop a simple, more pragmatic form that could be used to help rheumatologists manage selected comorbidities, and know when to refer for other specialist assessment. The focus was on ischemic cardiovascular disease, malignancies, infections such as chronic bronchitis, gastrointestinal disease such as diverticulitis, osteoporosis, and depression.

A committee of 18 experts, both physicians and nurses, was convened to examine the results of a systematic literature review of recommendations on comorbidity management and come up with concise recommendations for rheumatologists. Each of their recommendations covered whether or not the comorbidity was present (yes/no/don’t know) and if screening had been undertaken, such as measurement of blood lipids, and when this had occurred if known. There was then guidance on how to interpret these findings, calculate risk, and what to do if findings were abnormal.

The project is ongoing, and so far the expert panel has developed a pragmatic document with forms to help collect, report, and manage each specific comorbidity and its known risk factors. But it is still perhaps too long to be feasibly used in everyday practice, Dr. Gossec conceded. So the aim is to create a short, 2-page form that could summarize the recommendations briefly, and also develop a questionnaire for the patient to fill out and understand how to self-manage some comorbidities.

“We feel that this is a way to disseminate and adapt to the national context for France the EULAR comorbidities initiative,” Dr. Gossec said. “It also defines exactly what rheumatologists should be doing and when they should refer, hopefully to the benefit of our patients.”

Dr. Sattar has participated in advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lily and UCB. He has also consulted for Merck and is a member of Roche’s speakers’ bureau. Dr. de Paolo and Dr. Nurmohamed reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Ikdahl has received speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer. Dr. Gossec and coauthors have received honoraria from Abbvie France.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

LONDON – Cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk assessment for patients with rheumatic diseases can be simple and integrated into general practice or rheumatology clinics, experts said during an Outcomes Science Session at the European Congress of Rheumatology

Patients with rheumatoid arthritis have a 50% higher risk of heart disease than do their counterparts without the disease, but “just having RA on its own isn’t sufficient to render that individual at high risk,” Dr. Naveed Sattar, professor of metabolic medicine at the University of Glasgow’s Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences in Scotland, said in an interview.

It’s simple enough to use traditional CVD risk factors in an RA population by including a patient’s age, gender, smoking status, and family history of heart disease, in addition to measuring blood pressure and blood lipid levels. Most risk scores will compile those features into a 10-year risk of a fatal CVD event. To account for the contribution of RA, Dr. Sattar said, simply multiply that score by 1.5.

While “there’s a fixation in some parts of Europe for [measuring] fasting lipids,” it is not necessary, Dr. Sattar said. The two lipid parameters that go in risk scores tend to be cholesterol and HDL cholesterol, he said, which change only minimally in fasting versus nonfasting states.

“The evidence overwhelmingly shows that nonfasting lipids, which can be done easily on the same sample as other clinic tests, are just as predictive of CVD risk as fasting lipids,” he said. “That really matters because many of our patients with RA or other conditions come to the hospital when they’re not fasting, and we shouldn’t be sending them away to come back fasting to do risk scores for CVD. That just doesn’t make sense.”

Updated guidelines from the European Society of Cardiology and guidelines soon to be released from the European League Against Rheumatism suggest that risk scores can be calculated every 5 years for most patients, a change from previous recommendations to calculate risk annually. Risk scoring is not perfect, however, and there is some debate about whether additional blood tests or ultrasound scanning of the carotid artery could augment the ability to predict heart disease risk. “We’re not quite there yet,” Dr. Sattar said. “I think we should do the simple things first and do them well.”

CV risk raised in all inflammatory arthritic diseases

During the same session, Dr. Paola de Pablo of the University of Birmingham, England, focused on how immune-mediated diseases predispose to premature, accelerated atherosclerosis and subsequent increased cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Cardiovascular risk is not only elevated in those with RA, she observed, but also in those with systemic lupus erythematosus, ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, vasculitides, and inflammatory myopathies. The risk varies but as a rule is more than 50% higher than the rate seen in the general population.

The underlying mechanisms are not clear, but chronic inflammation is closely linked with atherosclerosis, which in turn ups the risk for myocardial infarction and cerebrovascular accident.

Despite treatment, the risk often remains, Dr. de Pablo said. She highlighted how treatment with methotrexate and anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF)–alpha drugs in RA had been associated with a reduction in the risk for heart attack of 20% and 40%, respectively (Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;74:480–89) so targeting inflammation with these drugs may have positive effects, at least in RA.

Managing traditional cardiovascular risk factors remains important, Dr. de Pablo said. That was a sentiment echoed by Dr. Sattar and by rheumatologist Dr. Michael Nurmohamed of the VU Medical Center in Amsterdam. This includes controlling blood pressure with antihypertensive medications and blood lipids with statins, and advocating smoking cessation and perhaps other appropriate lifestyle changes such as increasing physical exercise and controlling weight.

Dr. Nurmohamed, who was involved in the 2015 update of the EULAR recommendations on cardiovascular risk management, noted that traditional risk factor management in patients with arthritis in current clinical practice is often poor and that strategies to address this were urgently needed.

Although treating to-target and preventing disease flares in the rheumatic diseases is important, it lowers but does not normalize cardiovascular risk. “This appears to be irrespective of the drug used,” Dr. Nurmohamed said. Rheumatologists need to be careful when tapering medication, particularly the biologics, as these are perhaps helping to temper cardiovascular inflammation, which could worsen when doses are reduced. “Antirheumatic treatment only is not good enough to decrease or normalize the cardiovascular risk of our patients”, he emphasized.

Norwegian project shows how to integrate CVD assessment into routine practice

In a separate presentation, Dr. Eirik Ikdahl, a PhD student at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo, discussed how some rheumatology clinics in Norway are successfully incorporating CVD risk screening.

Through the Norwegian Collaboration on Atherosclerotic disease in patients with Rheumatic joint diseases (NOCAR), which started in April 2014, annual cardiovascular disease risk evaluations of patients with inflammatory joint diseases are being implemented into the practices of 11 rheumatology outpatient clinics. While waiting for clinic appointments, patients are given electronic devices through which they can report CVD risk factors via an electronic patient journal program called GoTreatIt Rheuma. From there, the clinic can order nonfasting lipid measurements and nurses can record patients’ blood pressure.

Then, using the ESC Systematic Coronary Risk Evaluation (SCORE) algorithm, the program automatically calculates a patient’s 10-year risk of a fatal CVD event. If the SCORE estimate is 5% or greater, the rheumatologist forwards a note to the patient’s primary care physician or cardiologist saying there is an indication for initiation of CVD-preventive measures such as medication or lifestyle changes. Rheumatologists and rheumatology nurses also deliver brief advice regarding smoking cessation and healthy diet.

“The main aim of the project is to raise awareness of the cardiovascular burden that these patients experience, and to ensure that patients with inflammatory joint diseases receive guideline-recommended cardiovascular preventive treatment,” Dr. Ikdahl said.

Of 6,150 patients defined as eligible for the NOCAR project in three of the centers, 41% (n = 2,519) received a CVD risk assessment during the first year and a half of the program, officers found in a recent review. Of those, 1,569 had RA, 418 had ankylosing spondylitis, 350 had psoriatic arthritis, and 122 had other spondyloarthritides.

Through the program, “a large number of high-risk patients have received screening that they would not otherwise have been offered,” Dr. Ikdahl said.

The major obstacles to successful implementation were time scarcity, defining a date for annual CVD risk assessment among patients who visit the clinics multiple times per year, and making sure lipids were measured before seeing the rheumatologist, he said. “We acknowledge there is room for improvement. It is challenging to implement new work tasks in an already busy rheumatology outpatient clinic, and since the project does not offer financial incentives to the participating centers, we rely on a collective effort and voluntary work based on resources already available.”

Remember CVD, but don’t forget other comorbidities

Other research presented by Dr. Laure Gossec, professor of rheumatology at Pitie-Salpétriere Hospital and Pierre & Marie Curie University in Paris highlighted the importance of identifying all comorbidities and their risk factors in patients with rheumatic diseases, and not just cardiovascular disease.

Dr. Gossec presented the results of an initiative aiming to make the collection and management of comorbidities easier in routine rheumatologic practice. The aim was to develop a simple, more pragmatic form that could be used to help rheumatologists manage selected comorbidities, and know when to refer for other specialist assessment. The focus was on ischemic cardiovascular disease, malignancies, infections such as chronic bronchitis, gastrointestinal disease such as diverticulitis, osteoporosis, and depression.

A committee of 18 experts, both physicians and nurses, was convened to examine the results of a systematic literature review of recommendations on comorbidity management and come up with concise recommendations for rheumatologists. Each of their recommendations covered whether or not the comorbidity was present (yes/no/don’t know) and if screening had been undertaken, such as measurement of blood lipids, and when this had occurred if known. There was then guidance on how to interpret these findings, calculate risk, and what to do if findings were abnormal.

The project is ongoing, and so far the expert panel has developed a pragmatic document with forms to help collect, report, and manage each specific comorbidity and its known risk factors. But it is still perhaps too long to be feasibly used in everyday practice, Dr. Gossec conceded. So the aim is to create a short, 2-page form that could summarize the recommendations briefly, and also develop a questionnaire for the patient to fill out and understand how to self-manage some comorbidities.

“We feel that this is a way to disseminate and adapt to the national context for France the EULAR comorbidities initiative,” Dr. Gossec said. “It also defines exactly what rheumatologists should be doing and when they should refer, hopefully to the benefit of our patients.”

Dr. Sattar has participated in advisory boards for Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lily and UCB. He has also consulted for Merck and is a member of Roche’s speakers’ bureau. Dr. de Paolo and Dr. Nurmohamed reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Ikdahl has received speaker’s honoraria from Pfizer. Dr. Gossec and coauthors have received honoraria from Abbvie France.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

AT THE EULAR 2016 CONGRESS

TNF blocker safety may differ in RA and psoriasis patients

Rheumatoid arthritis patients on anti–tumor necrosis factor medications had approximately twice the rate of serious adverse events as did psoriasis patients on the same medications, based on data from a pair of prospective studies of about 4,000 adults.

The findings were published online in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“Current trends are to extrapolate the abundant literature existing on the safety of TNF antagonists in RA to define safety management for psoriasis,” wrote Dr. Ignacio García-Doval of the Fundación Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología, Madrid, and colleagues. However, data on the similarity of risk associated with anti-TNF medications in RA and psoriasis are limited, the investigators said (BJD. 2016. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14776).

The researchers compared data from two similarly designed, overlapping prospective safety registry studies of anti-TNF medications in RA patients (the BIOBADASER study) and psoriasis patients (the BIOBADADERM study).

In the cohort of 3,171 RA patients, the researchers identified 1,248 serious or fatal adverse events during 16,230 person-years of follow-up; in the cohort of 946 psoriasis patients, they identified 124 serious or fatal adverse events during 2,760 person-years of follow-up. The resulting incidence rate ratio of psoriasis to RA was 0.6. The increased risk of serious adverse events for RA patients compared with psoriasis patients remained after the investigators controlled for confounding factors including age, sex, treatments, and comorbid conditions including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and methotrexate therapy, for a hazard ratio of 0.54.

Moreover, the types of serious adverse events were different between the RA and psoriasis groups. Among those with RA, the rates of serious infections, cardiac disorders, respiratory disorders, and infusion reactions were significantly greater among those with RA, while psoriatic patients “had more skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders and hepatobiliary disorders,” the researchers noted.

By contrast, “rates of nonserious adverse events cannot be compared between the two cohorts,” because of differences in definitions, they pointed out. These differences resulted in a nonserious adverse event rate that was more than twice as high in the psoriasis group as in the RA group (582.2 events per 1,000 patient-years vs. 242.8 events per 1,000 patient-years).

Based on the findings, “published safety results of TNF-antagonists in RA cannot be fully extrapolated to psoriasis, as patients with RA have a higher risk and a different pattern of serious adverse events,” they concluded.

The BIOBADADERM project is promoted by the Fundación Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología, which is supported by the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and by multiple pharmaceutical companies. BIOBADASER received funding from Fundacion Española de Reumatología and the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Lead author Dr. Garcia-Doval disclosed travel grants for congresses from Merck/Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Janssen; the remaining two authors disclosed being a speaker and/or a consultant for several companies, including AbbVie.

Rheumatoid arthritis patients on anti–tumor necrosis factor medications had approximately twice the rate of serious adverse events as did psoriasis patients on the same medications, based on data from a pair of prospective studies of about 4,000 adults.

The findings were published online in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“Current trends are to extrapolate the abundant literature existing on the safety of TNF antagonists in RA to define safety management for psoriasis,” wrote Dr. Ignacio García-Doval of the Fundación Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología, Madrid, and colleagues. However, data on the similarity of risk associated with anti-TNF medications in RA and psoriasis are limited, the investigators said (BJD. 2016. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14776).

The researchers compared data from two similarly designed, overlapping prospective safety registry studies of anti-TNF medications in RA patients (the BIOBADASER study) and psoriasis patients (the BIOBADADERM study).

In the cohort of 3,171 RA patients, the researchers identified 1,248 serious or fatal adverse events during 16,230 person-years of follow-up; in the cohort of 946 psoriasis patients, they identified 124 serious or fatal adverse events during 2,760 person-years of follow-up. The resulting incidence rate ratio of psoriasis to RA was 0.6. The increased risk of serious adverse events for RA patients compared with psoriasis patients remained after the investigators controlled for confounding factors including age, sex, treatments, and comorbid conditions including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and methotrexate therapy, for a hazard ratio of 0.54.

Moreover, the types of serious adverse events were different between the RA and psoriasis groups. Among those with RA, the rates of serious infections, cardiac disorders, respiratory disorders, and infusion reactions were significantly greater among those with RA, while psoriatic patients “had more skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders and hepatobiliary disorders,” the researchers noted.

By contrast, “rates of nonserious adverse events cannot be compared between the two cohorts,” because of differences in definitions, they pointed out. These differences resulted in a nonserious adverse event rate that was more than twice as high in the psoriasis group as in the RA group (582.2 events per 1,000 patient-years vs. 242.8 events per 1,000 patient-years).

Based on the findings, “published safety results of TNF-antagonists in RA cannot be fully extrapolated to psoriasis, as patients with RA have a higher risk and a different pattern of serious adverse events,” they concluded.

The BIOBADADERM project is promoted by the Fundación Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología, which is supported by the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and by multiple pharmaceutical companies. BIOBADASER received funding from Fundacion Española de Reumatología and the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Lead author Dr. Garcia-Doval disclosed travel grants for congresses from Merck/Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Janssen; the remaining two authors disclosed being a speaker and/or a consultant for several companies, including AbbVie.

Rheumatoid arthritis patients on anti–tumor necrosis factor medications had approximately twice the rate of serious adverse events as did psoriasis patients on the same medications, based on data from a pair of prospective studies of about 4,000 adults.

The findings were published online in the British Journal of Dermatology.

“Current trends are to extrapolate the abundant literature existing on the safety of TNF antagonists in RA to define safety management for psoriasis,” wrote Dr. Ignacio García-Doval of the Fundación Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología, Madrid, and colleagues. However, data on the similarity of risk associated with anti-TNF medications in RA and psoriasis are limited, the investigators said (BJD. 2016. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14776).

The researchers compared data from two similarly designed, overlapping prospective safety registry studies of anti-TNF medications in RA patients (the BIOBADASER study) and psoriasis patients (the BIOBADADERM study).

In the cohort of 3,171 RA patients, the researchers identified 1,248 serious or fatal adverse events during 16,230 person-years of follow-up; in the cohort of 946 psoriasis patients, they identified 124 serious or fatal adverse events during 2,760 person-years of follow-up. The resulting incidence rate ratio of psoriasis to RA was 0.6. The increased risk of serious adverse events for RA patients compared with psoriasis patients remained after the investigators controlled for confounding factors including age, sex, treatments, and comorbid conditions including hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and methotrexate therapy, for a hazard ratio of 0.54.

Moreover, the types of serious adverse events were different between the RA and psoriasis groups. Among those with RA, the rates of serious infections, cardiac disorders, respiratory disorders, and infusion reactions were significantly greater among those with RA, while psoriatic patients “had more skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders and hepatobiliary disorders,” the researchers noted.

By contrast, “rates of nonserious adverse events cannot be compared between the two cohorts,” because of differences in definitions, they pointed out. These differences resulted in a nonserious adverse event rate that was more than twice as high in the psoriasis group as in the RA group (582.2 events per 1,000 patient-years vs. 242.8 events per 1,000 patient-years).

Based on the findings, “published safety results of TNF-antagonists in RA cannot be fully extrapolated to psoriasis, as patients with RA have a higher risk and a different pattern of serious adverse events,” they concluded.

The BIOBADADERM project is promoted by the Fundación Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología, which is supported by the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and by multiple pharmaceutical companies. BIOBADASER received funding from Fundacion Española de Reumatología and the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Lead author Dr. Garcia-Doval disclosed travel grants for congresses from Merck/Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Janssen; the remaining two authors disclosed being a speaker and/or a consultant for several companies, including AbbVie.

FROM THE BRITISH JOURNAL OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: TNF-antagonists provoke different adverse events in patients with RA than in those with psoriasis, and safety data should be extrapolated with caution.

Major finding: The risk of serious adverse events associated with anti-TNF therapy was approximately twice as high in RA patients as in psoriasis patients (hazard ratio, 0.54).

Data source: A pair of prospective studies including 4,117 adults with RA or psoriasis who received anti-TNF agents.

Disclosures: The BIOBADADERM project is promoted by the Fundación Academia Española de Dermatología y Venereología, which is supported by the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and by multiple pharmaceutical companies. BIOBADASER received funding from Fundacion Española de Reumatología and the Spanish Medicines and Health Products Agency and grants from numerous pharmaceutical companies. Lead author Dr. Garcia-Doval disclosed travel grants for congresses from Merck/Schering-Plough Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, and Janssen; the remaining two authors disclosed being a speaker and/or a consultant for several companies, including AbbVie.

Early identification, treatment still key to early arthritis guidelines

LONDON, ENGLAND – Prompt referral to a rheumatologist and early initiation of treatment remain 2 of the 12 key recommendations in the updated European League Against Rheumatism guidelines for early arthritis.

There are now three specific recommendations dealing with referral and diagnosis; four that cover initial drug treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and glucocorticoids; two that cover management strategy and monitoring; and three that cover nonpharmacologic interventions, prevention, and patient information and education.

While many of the recommendations have not radically changed, there have been revisions to the wording. In line with other EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatic disease, the updated early arthritis guidelines also now contain three overarching principles. The first states that the management of early arthritis should aim to achieve the best possible care and emphasizes the need for shared decision making between rheumatologist and patient. The second states that a rheumatologist should be the main specialist looking after a patient with early arthritis, and the third states that a definitive diagnosis should be made only after a careful medical history and clinical examination have been undertaken.

“[The EULAR] recommendations deal especially with early-stage inflammatory arthritis,” said Dr. Bernard Combe of Hôpital Lapeyronie in Montpellier, France, who was the convener of the task force behind the updated guidelines. As such, they are universal for all rheumatologic arthritis conditions when diagnosed early, before they differentiate into more specifics, he said in an interview. That includes progression from early inflammatory arthritis to rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis.

Dr. Combe, who is also professor of rheumatology at Montpellier University and head of the bone and joint diseases department at Montpellier University Hospital, presented the updated EULAR guidance at the European Congress of Rheumatology. He noted that the guidelines were first written almost 10 years ago (Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jan;66(1):34-45) and so were in need of an update. A task force of 20 rheumatologists, two patients, and one health care professional representing 12 European countries were involved in the update that adhered to EULAR standard operating procedure of developing guidelines.

Although EULAR had published guidance on the management of arthritis in the intervening years, he said, this had focused more on management, and the aim of the early arthritis guidelines was to cover the “entire spectrum of the management of early inflammatory arthritis.”

The updated recommendations start and end with patient-centered statements, he observed. The first notes that patients with any joint swelling associated with pain or stiffness should be referred to and seen by a rheumatologist within 6 weeks of the onset of symptoms. The final recommendation deals with patient information and education about the disease, and programs aiming to help patients cope with pain, disability, and ensure their continued ability to work and participate in their usual social activities.

The concept of early identification and treatment is not new, Dr. Combe observed, but there is so much more evidence in support of initiating DMARD therapy within the first 3 months of referral, even if patients do not fulfill classification criteria for a specific inflammatory rheumatic disease.

In terms of diagnosis, the recommendations now hinge on performing a thorough clinical examination and using ultrasonography to confirm the presence of arthritis if needed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is no longer recommended in this initial diagnostic work up. This is due to the cost and often lack of widespread access in all European countries, Dr. Combe said. MRI might be considered later, however, if a diagnosis cannot be reached. Assessment of the number of swollen joints, acute phase reactants, and antibody tests (rheumatoid factor and anti-citrullinated protein antibody) also might be of use at this point.

Among the various DMARDs, methotrexate is recommended as the “anchor drug”; it should be used as part of the first treatment strategy in patients who are at risk of persistent disease, unless it contraindicated. The goal of treatment with DMARDs is to achieve clinical remission. Regular monitoring of disease activity, side effects, and comorbidities should be performed alongside their use. Regular monitoring of all pharmacologic therapy should include assessment of tender and swollen joint counts, global health assessments by the patient and the physician, and acute phase reactants.

As for NSAIDs, they are recommended for symptomatic relief, but “at the minimum effective dose for the shortest time possible.” The risks for gastrointestinal, renal, and cardiovascular complications should be carefully weighed against the likely benefits. Glucocorticoids also are recommended for reducing pain and swelling, and structural progression, but again these need to be used at the lowest possible dose and for no more than 6 months to avoid potential long-term side effects.

A recommendation on nonpharmacologic interventions also is included, which states that physical exercise and occupational therapy should be considered as adjunctive therapy.

In addition, the task force came up with a list of 10 research questions that need to be answered, which included items on risk prediction, optimal treatment combinations, and dosing regimens.

As with other EULAR guidelines, a flow chart is included that summarizes the recommendations to help guide physicians on when and how to treat, when to adapt dosing or change medication, and other treatments and approaches to consider.

There is a new recommendation on prevention highlighting the importance of smoking cessation, dental care, weight control, vaccination, and managing comorbidities.

Once the guidelines have been finalized, they will be published in the EULAR journal, Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, later in the year.

Dr. Combe has received research grants and honoraria from Pfizer, Roche-Chugai, and UCB, and honoraria from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Eli Lilly, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, and Novartis.

LONDON, ENGLAND – Prompt referral to a rheumatologist and early initiation of treatment remain 2 of the 12 key recommendations in the updated European League Against Rheumatism guidelines for early arthritis.

There are now three specific recommendations dealing with referral and diagnosis; four that cover initial drug treatment with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and glucocorticoids; two that cover management strategy and monitoring; and three that cover nonpharmacologic interventions, prevention, and patient information and education.

While many of the recommendations have not radically changed, there have been revisions to the wording. In line with other EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatic disease, the updated early arthritis guidelines also now contain three overarching principles. The first states that the management of early arthritis should aim to achieve the best possible care and emphasizes the need for shared decision making between rheumatologist and patient. The second states that a rheumatologist should be the main specialist looking after a patient with early arthritis, and the third states that a definitive diagnosis should be made only after a careful medical history and clinical examination have been undertaken.

“[The EULAR] recommendations deal especially with early-stage inflammatory arthritis,” said Dr. Bernard Combe of Hôpital Lapeyronie in Montpellier, France, who was the convener of the task force behind the updated guidelines. As such, they are universal for all rheumatologic arthritis conditions when diagnosed early, before they differentiate into more specifics, he said in an interview. That includes progression from early inflammatory arthritis to rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, and spondyloarthritis.

Dr. Combe, who is also professor of rheumatology at Montpellier University and head of the bone and joint diseases department at Montpellier University Hospital, presented the updated EULAR guidance at the European Congress of Rheumatology. He noted that the guidelines were first written almost 10 years ago (Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Jan;66(1):34-45) and so were in need of an update. A task force of 20 rheumatologists, two patients, and one health care professional representing 12 European countries were involved in the update that adhered to EULAR standard operating procedure of developing guidelines.

Although EULAR had published guidance on the management of arthritis in the intervening years, he said, this had focused more on management, and the aim of the early arthritis guidelines was to cover the “entire spectrum of the management of early inflammatory arthritis.”

The updated recommendations start and end with patient-centered statements, he observed. The first notes that patients with any joint swelling associated with pain or stiffness should be referred to and seen by a rheumatologist within 6 weeks of the onset of symptoms. The final recommendation deals with patient information and education about the disease, and programs aiming to help patients cope with pain, disability, and ensure their continued ability to work and participate in their usual social activities.

The concept of early identification and treatment is not new, Dr. Combe observed, but there is so much more evidence in support of initiating DMARD therapy within the first 3 months of referral, even if patients do not fulfill classification criteria for a specific inflammatory rheumatic disease.