User login

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

To the Editor:

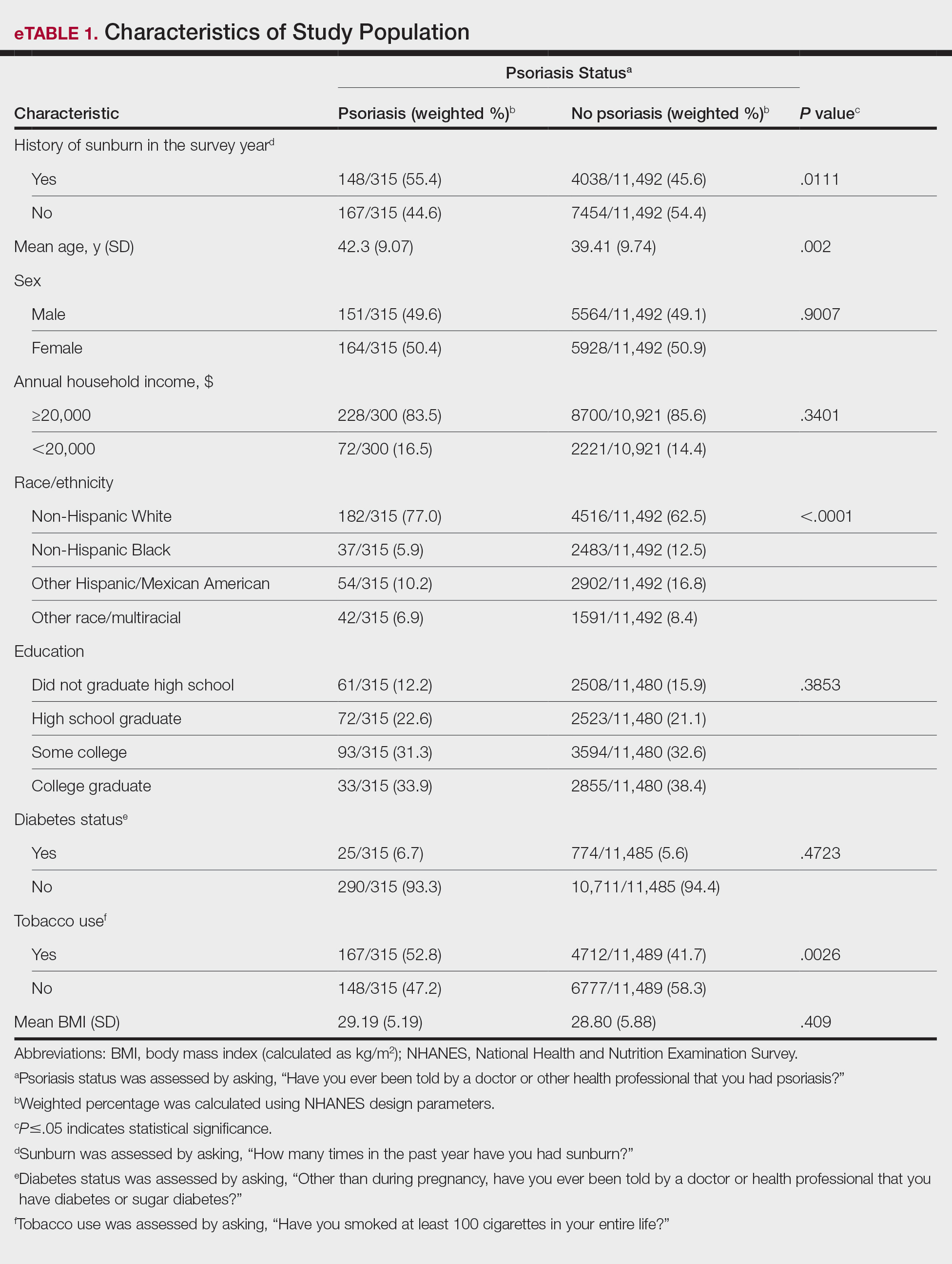

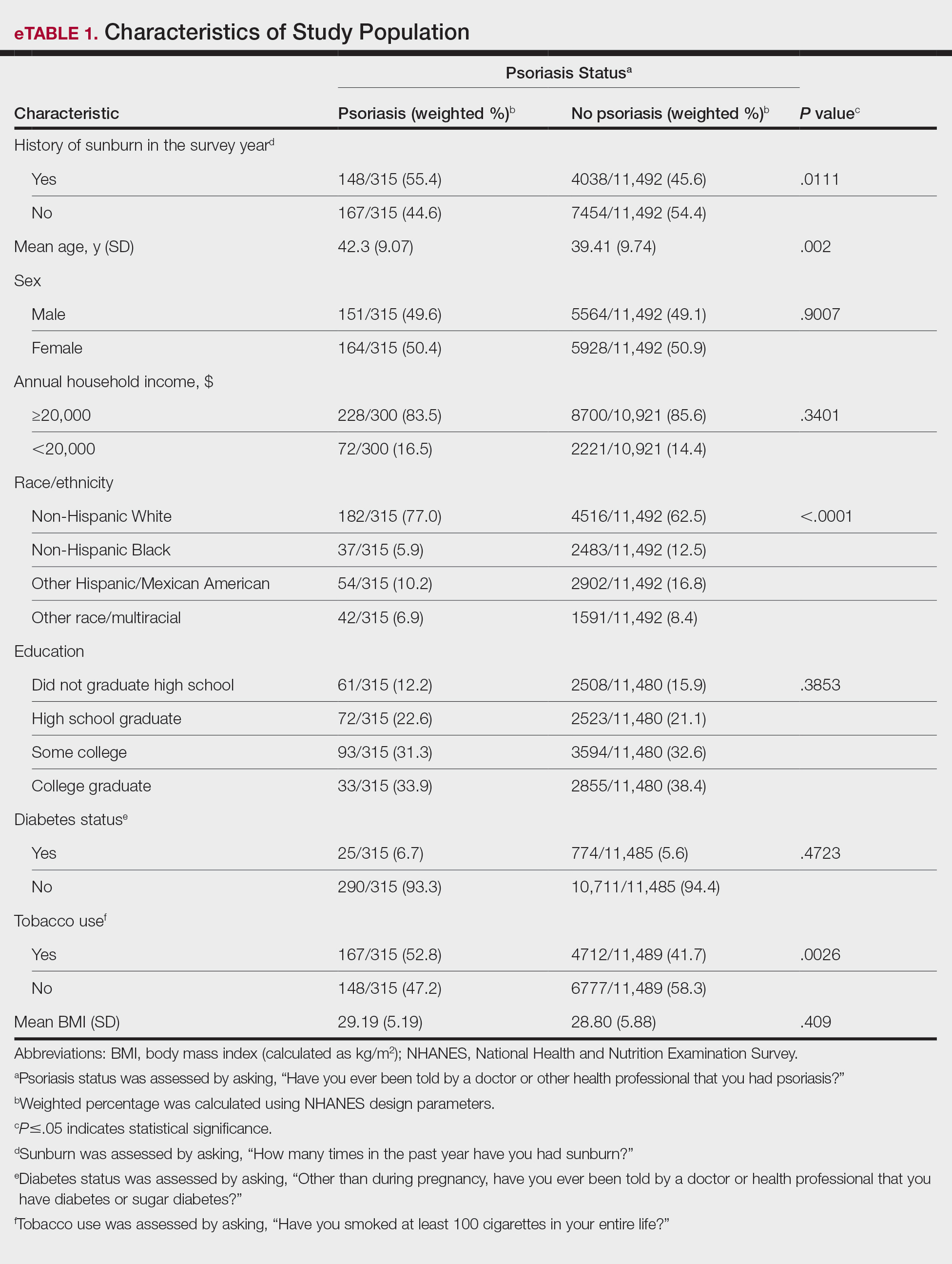

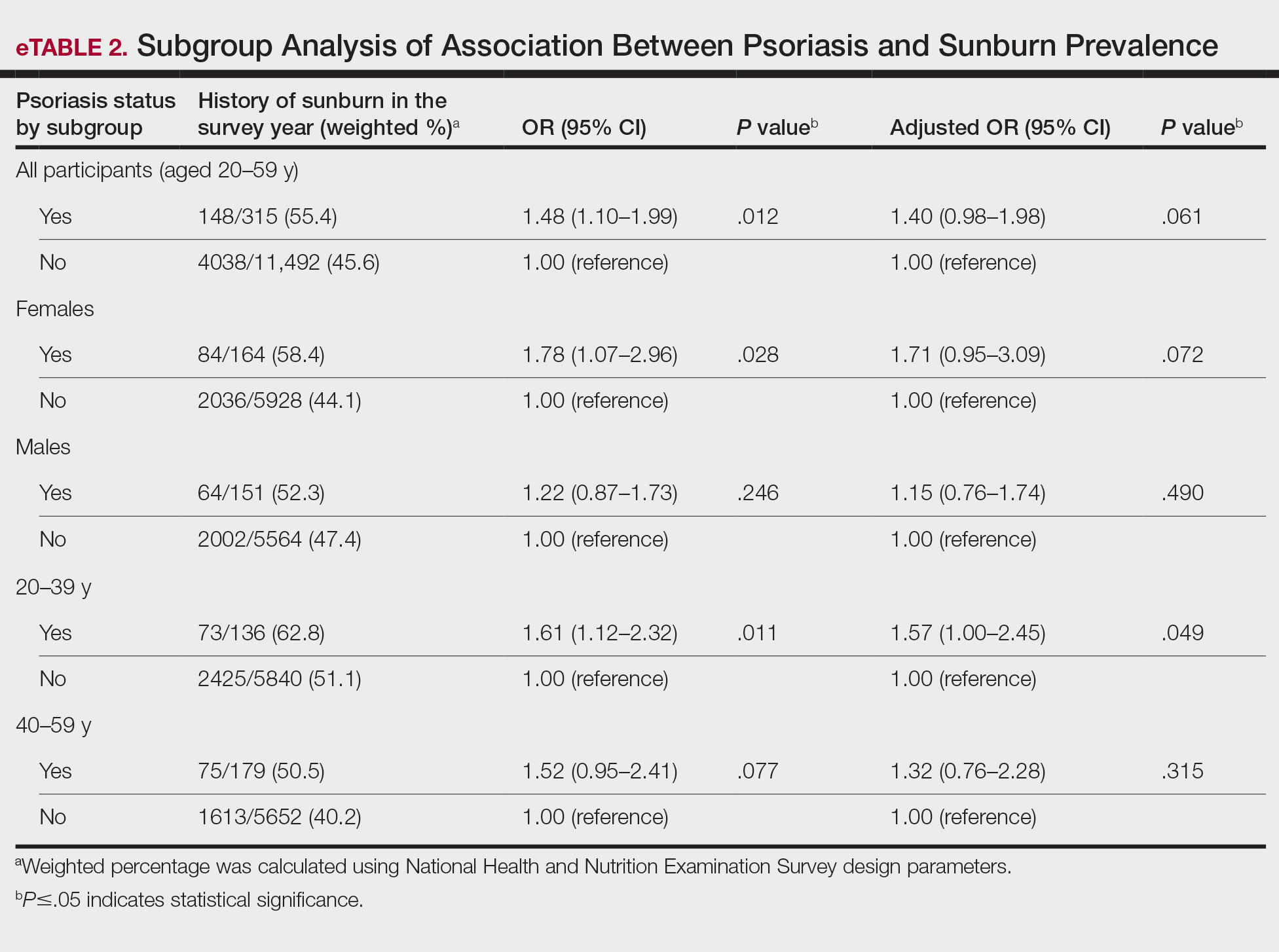

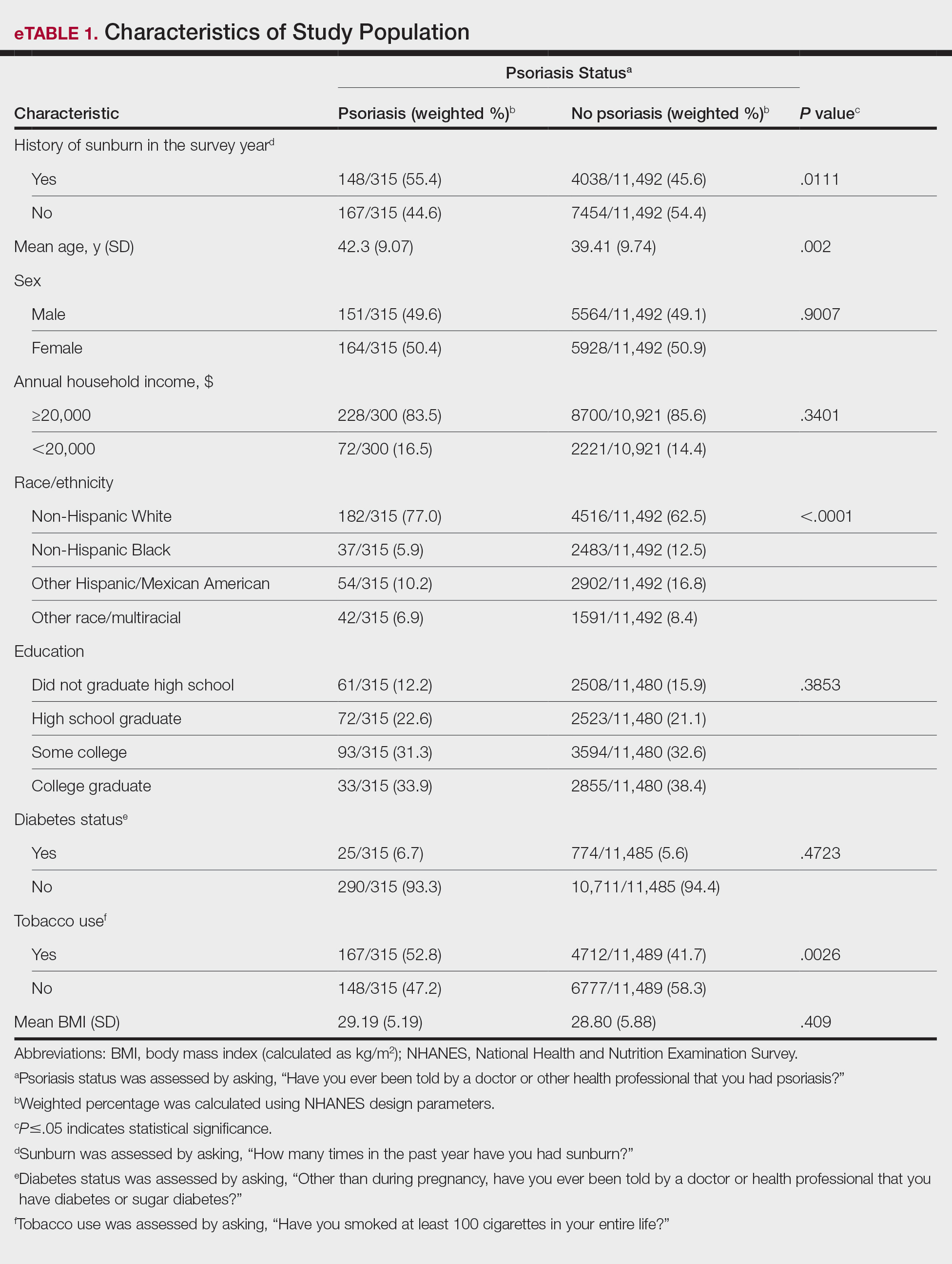

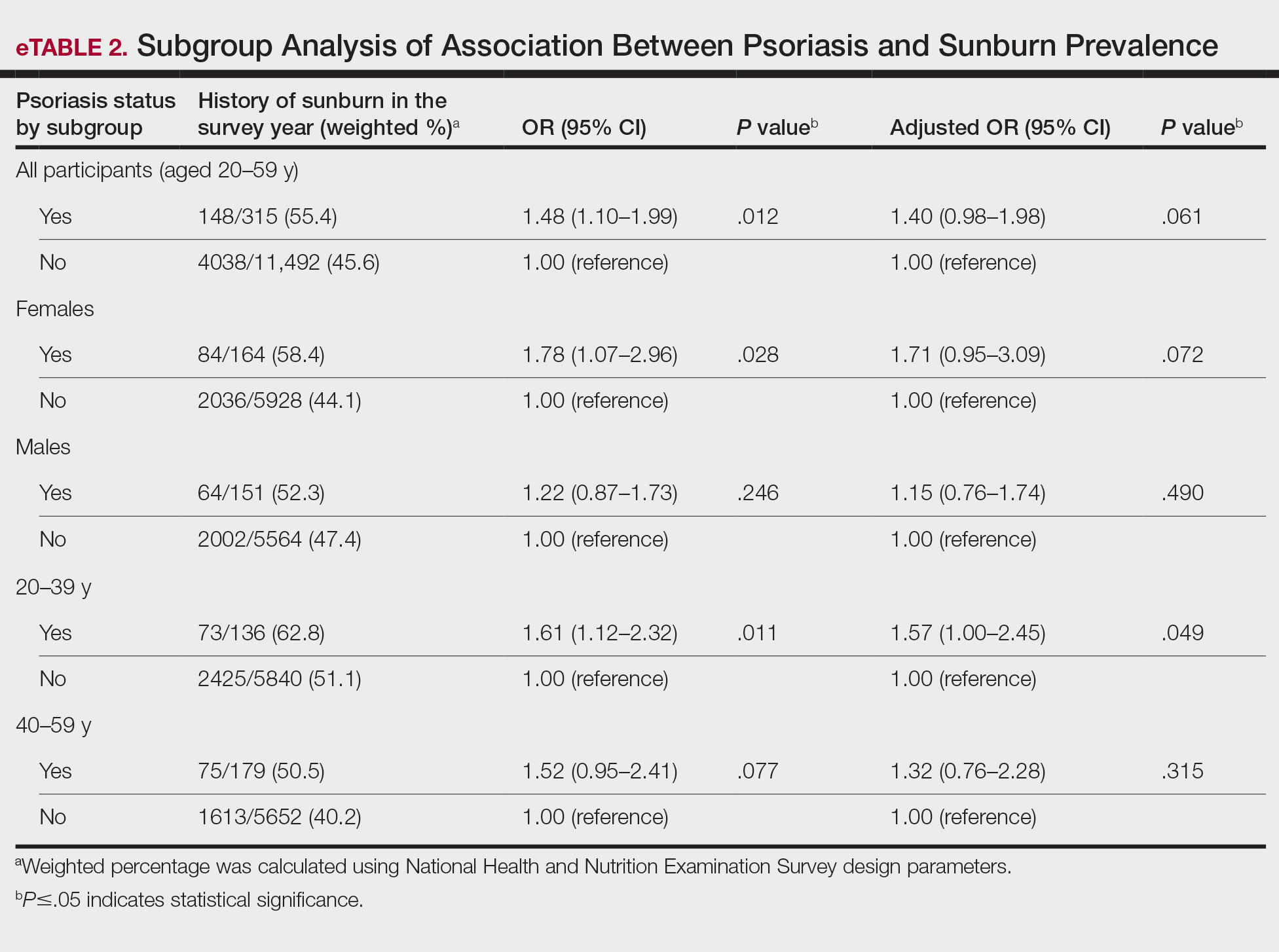

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects individuals in various extracutaneous ways.1 Prior studies have documented a decrease in exercise intensity among patients with psoriasis2; however, few studies have specifically investigated baseline mobility in this population. Baseline mobility denotes an individual’s fundamental ability to walk or move around without assistance of any kind. Impaired mobility—when baseline mobility is compromised—is an aspect of the wider diversity, equity, and inclusion framework that underscores the significance of recognizing challenges and promoting inclusive measures, both at the point of care and in research.3 study sought to analyze the relationship between psoriasis and baseline mobility among US adults (aged 45 to 80 years) utilizing the latest data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database for psoriasis.4 We used three 2-year cycles of NHANES data to create a 2009-2014 dataset.

The overall NHANES response rate among adults aged 45 to 80 years between 2009 and 2014 was 67.9%. Patients were categorized as having impaired mobility if they responded “yes” to the following question: “Because of a health problem, do you have difficulty walking without using any special equipment?” Psoriasis status was assessed by the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18.0 software (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and impaired mobility. Age, income, education, sex, race, tobacco use, diabetes status, body mass index, and arthritis status were controlled for in our models.

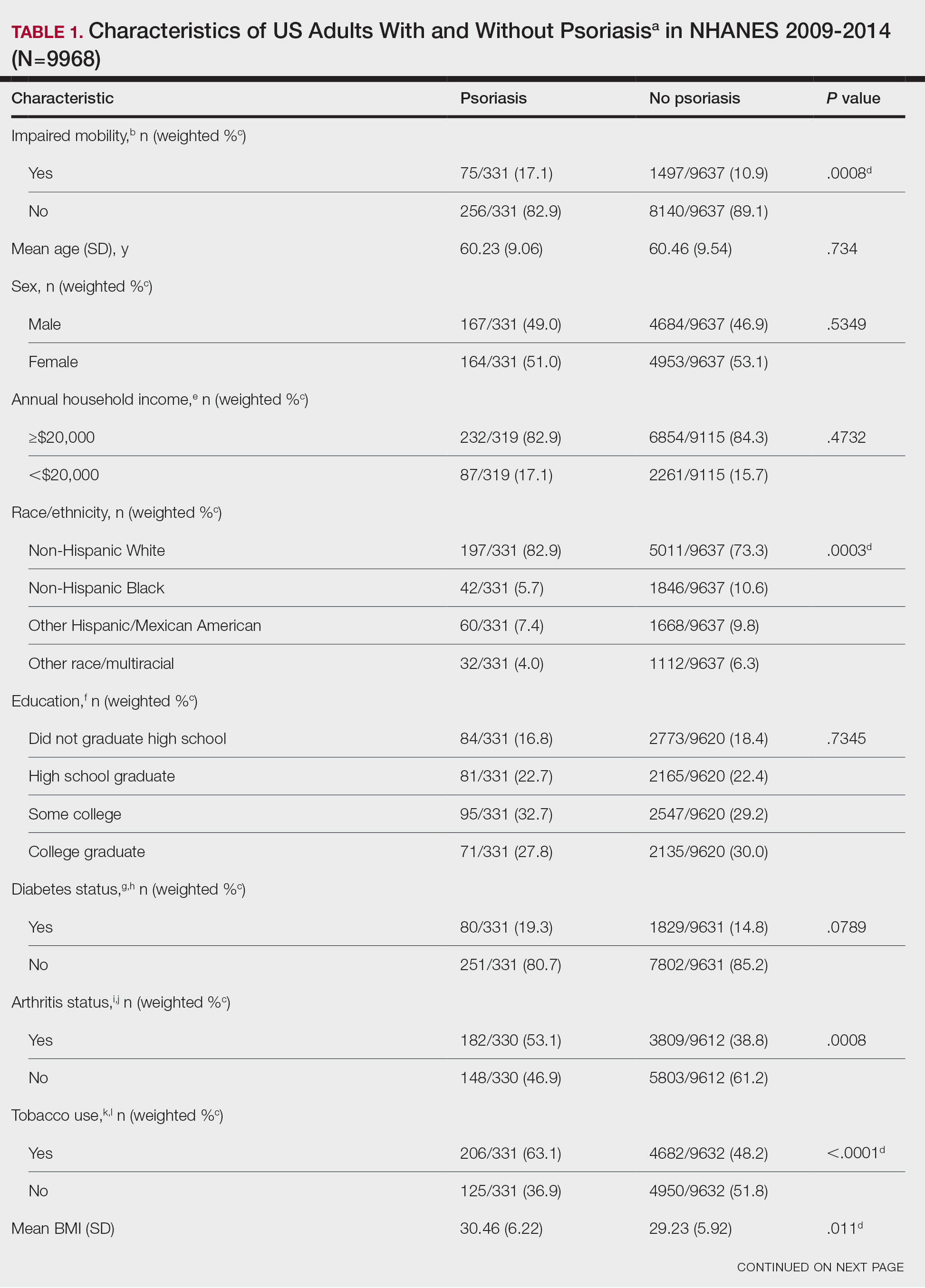

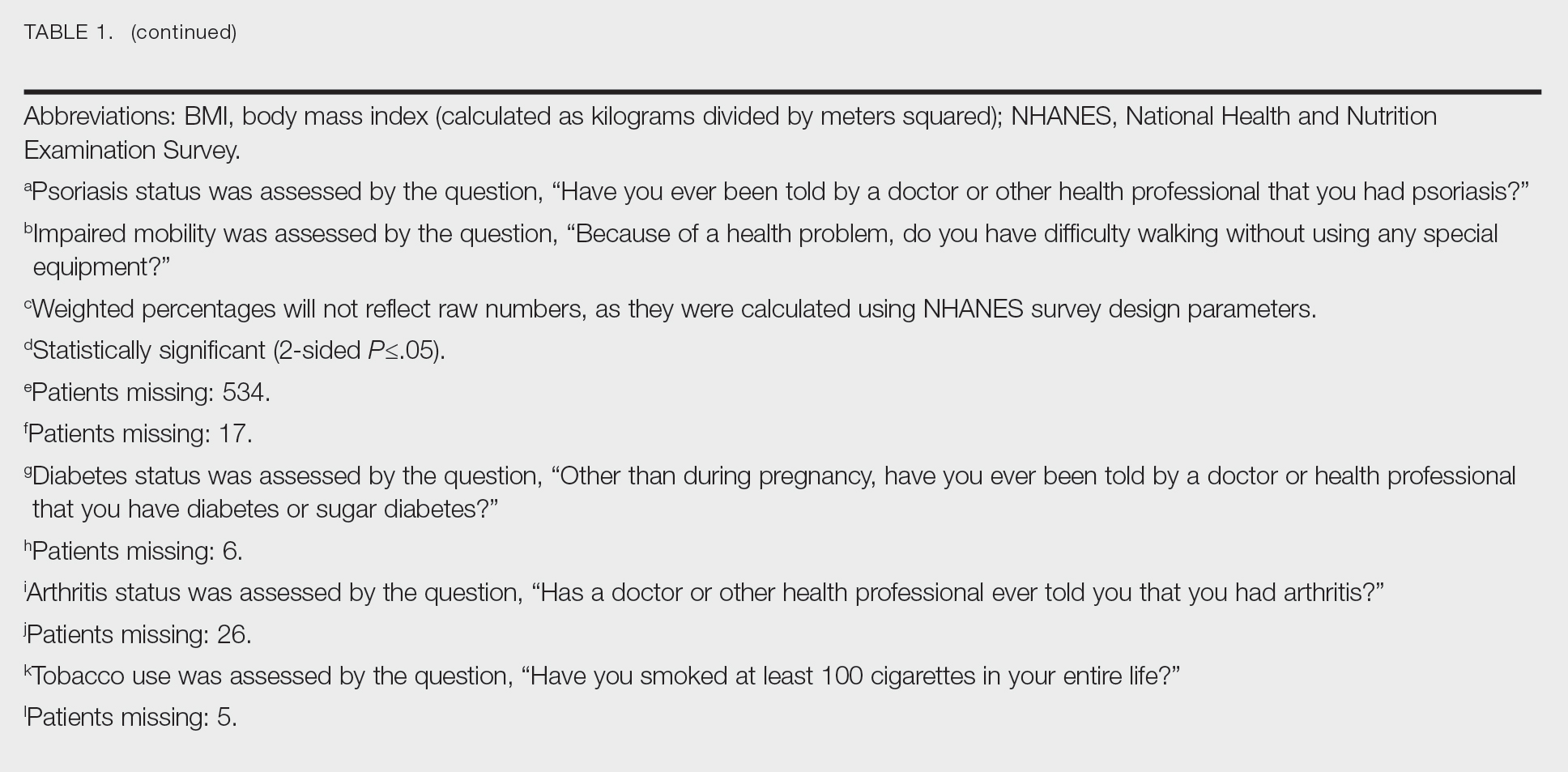

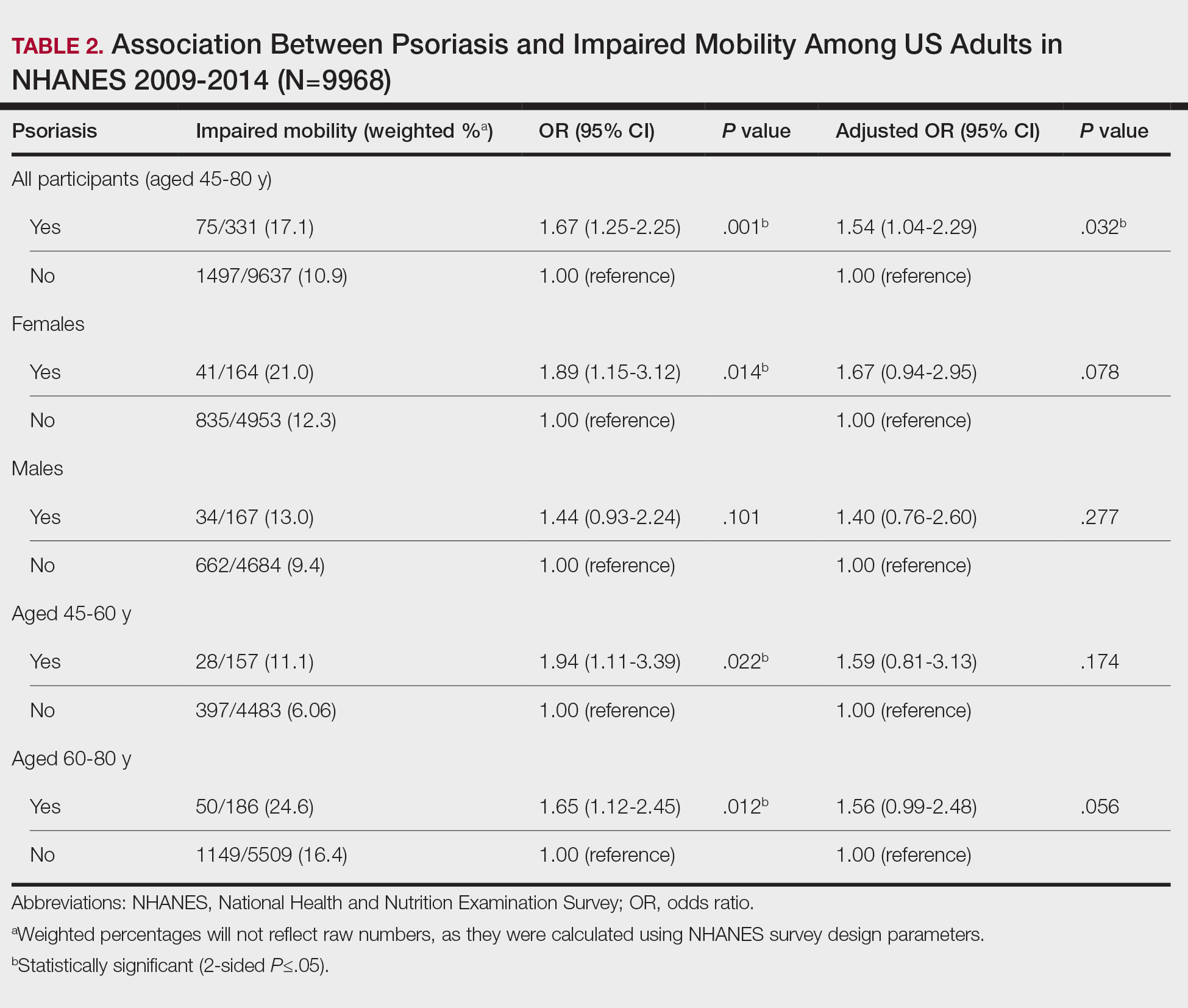

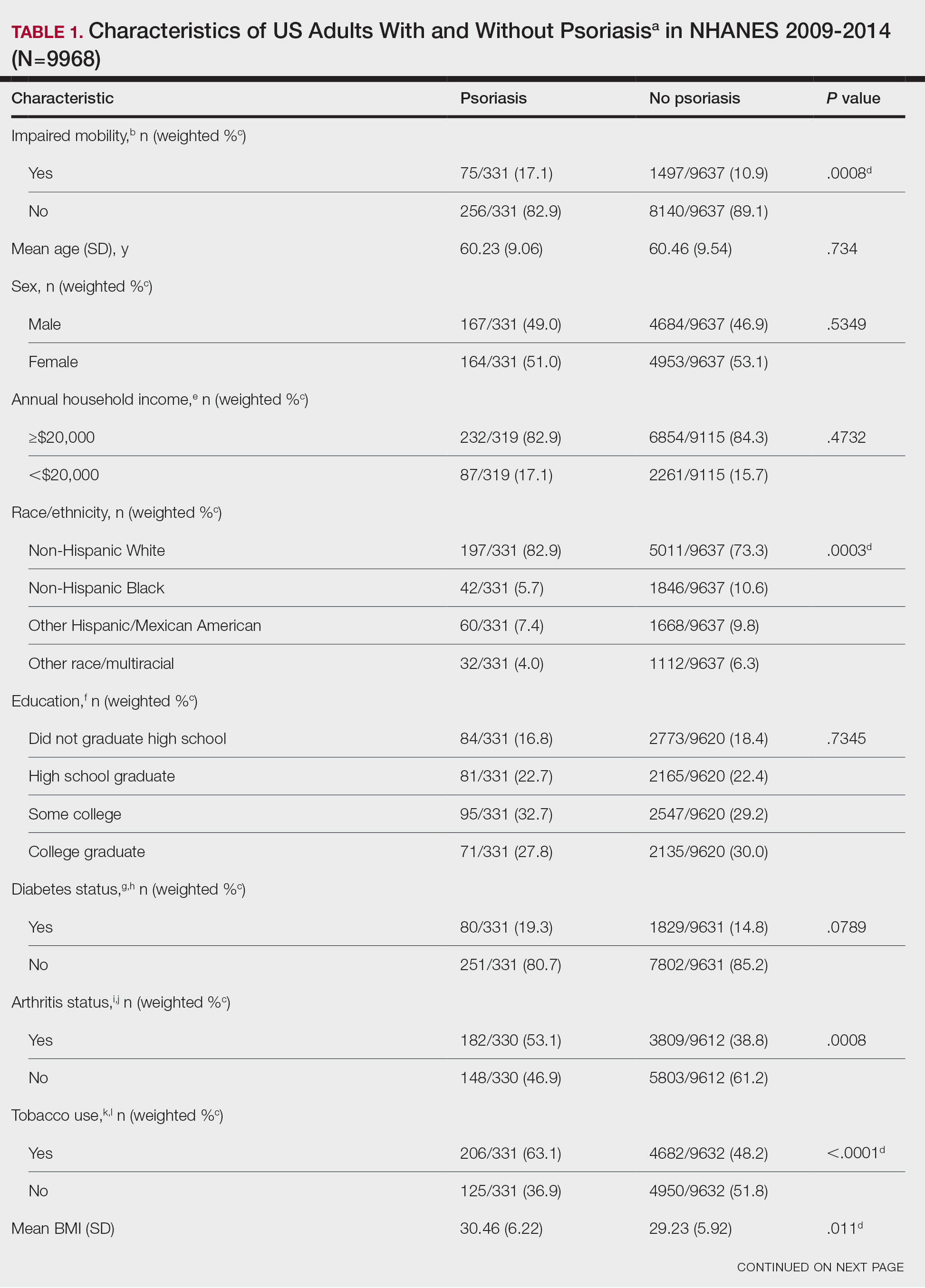

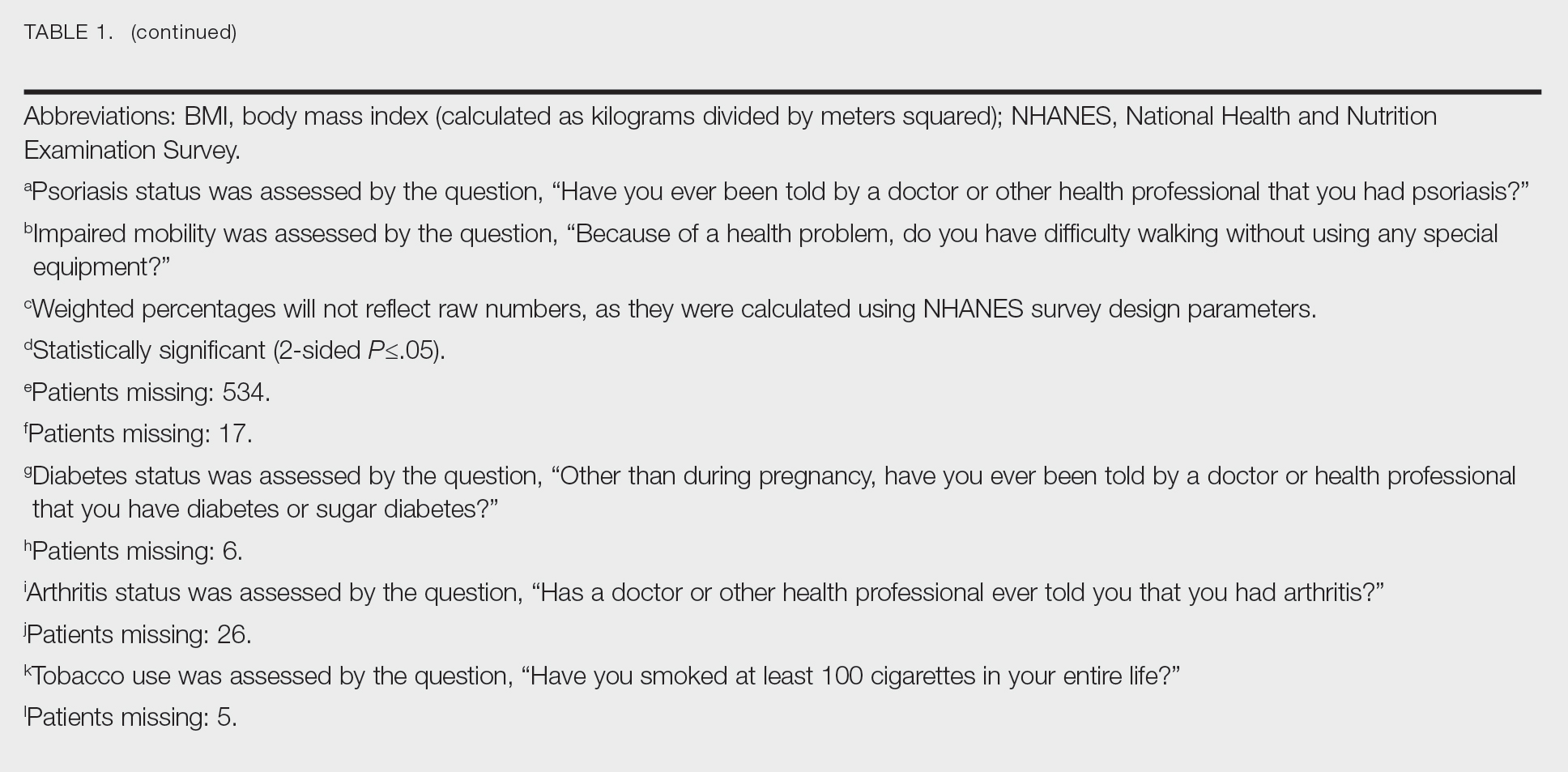

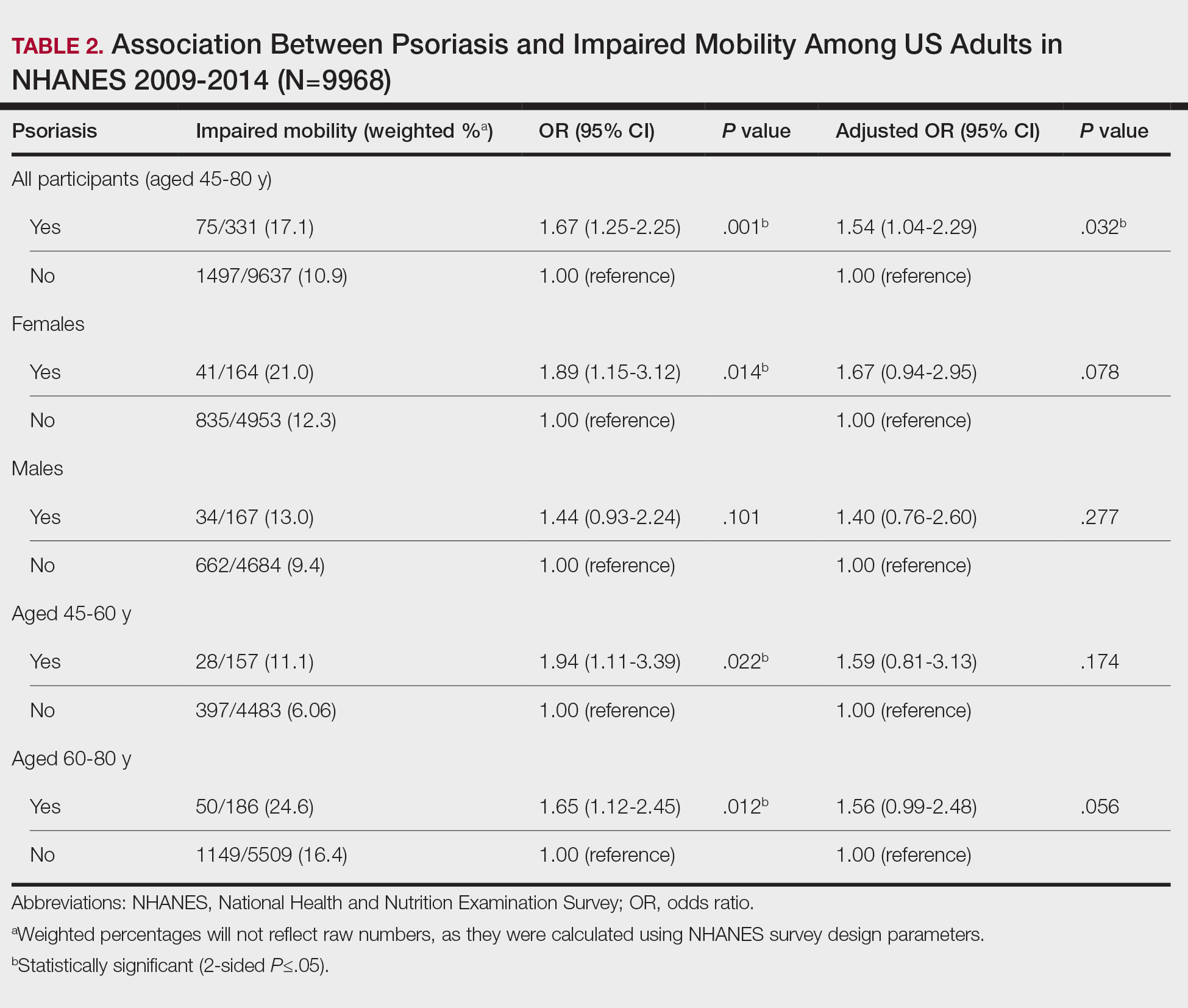

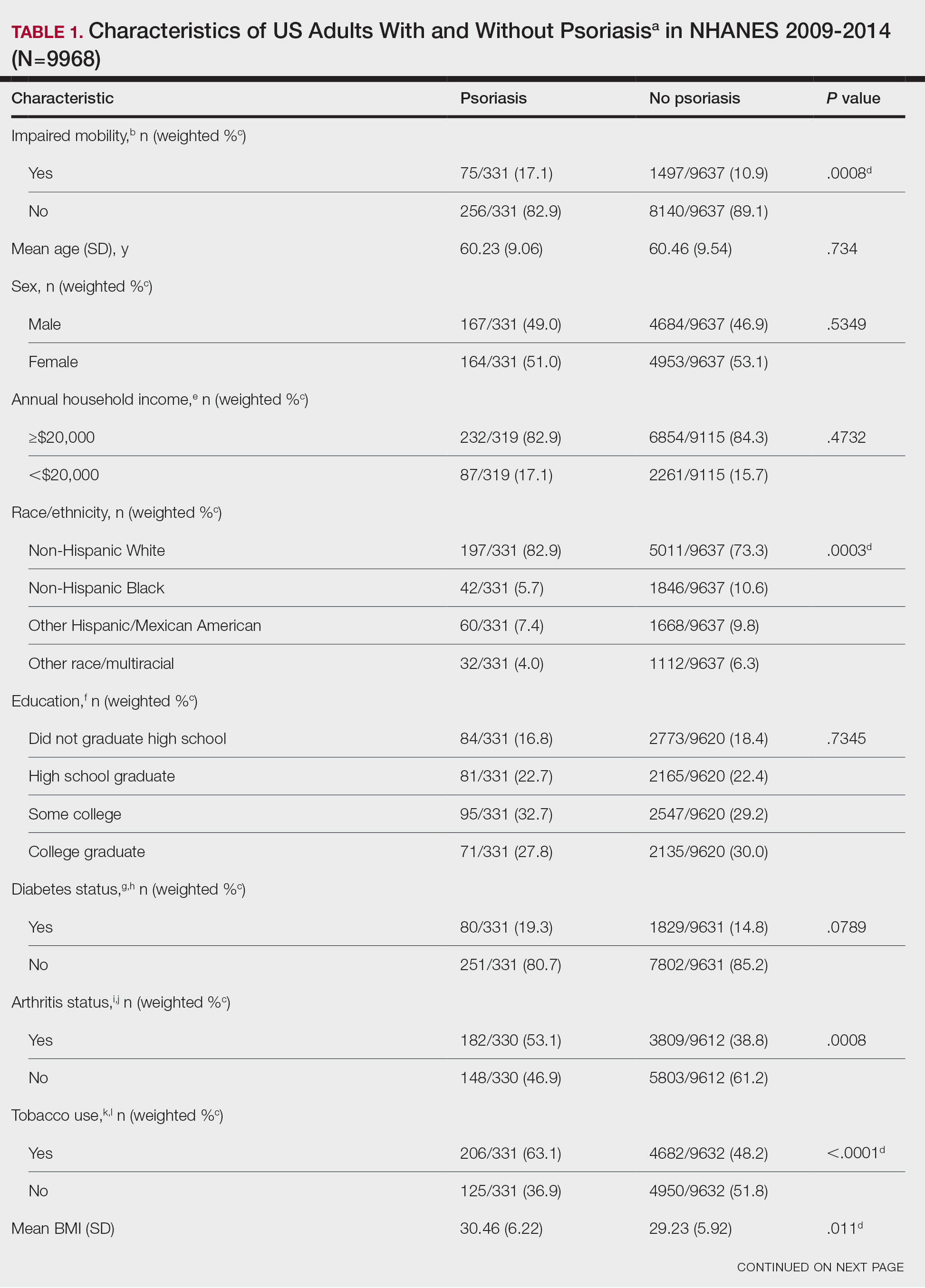

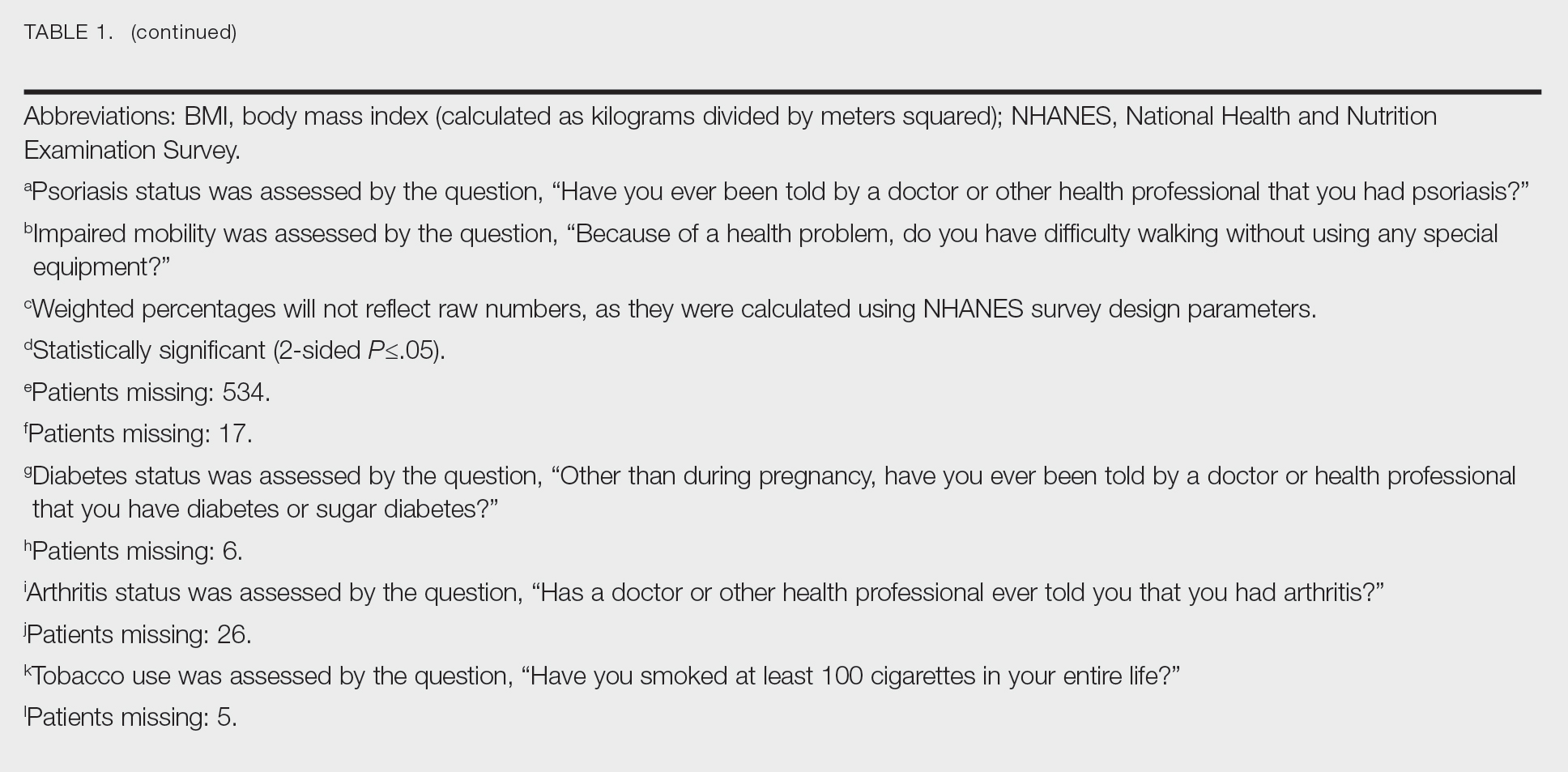

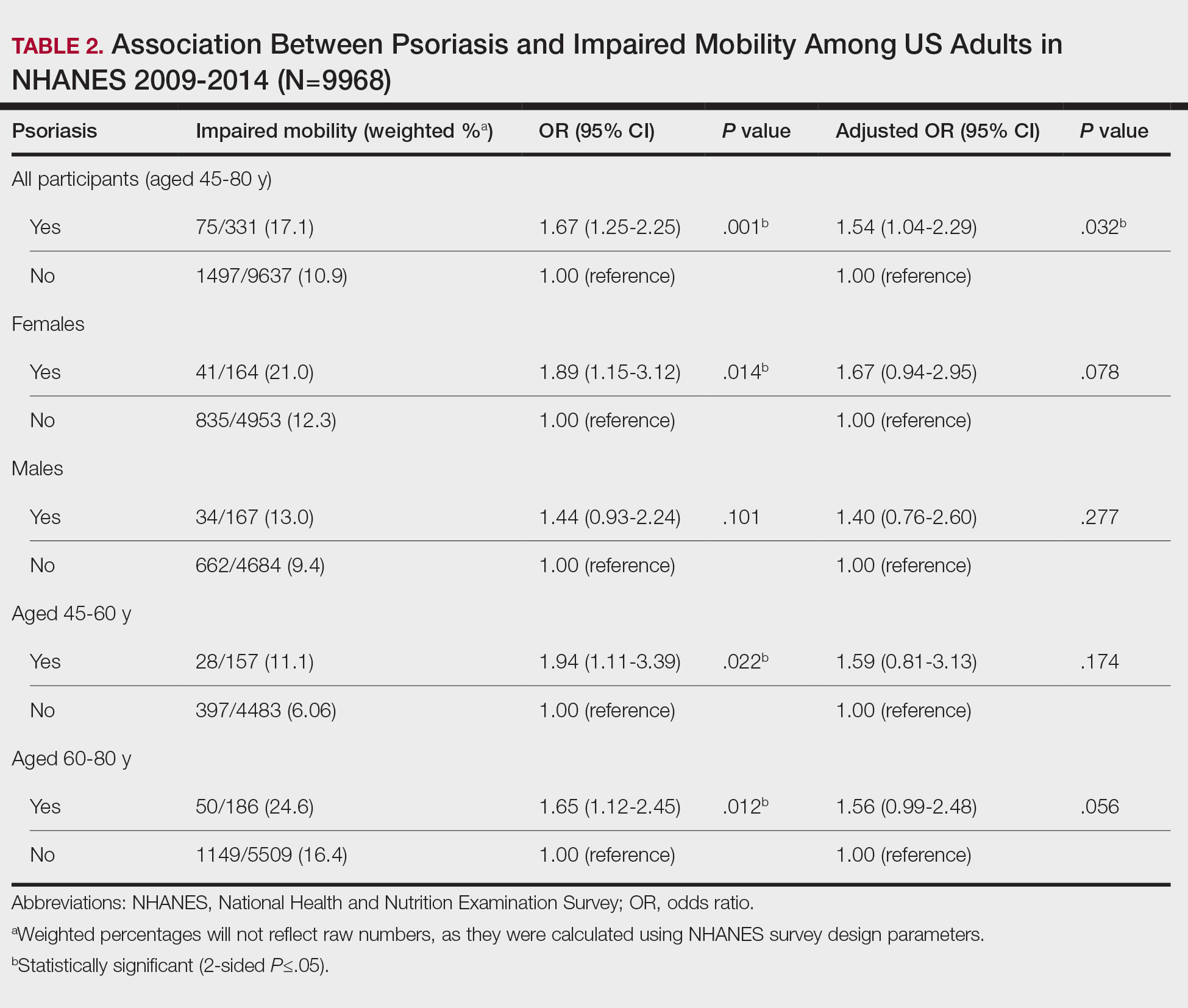

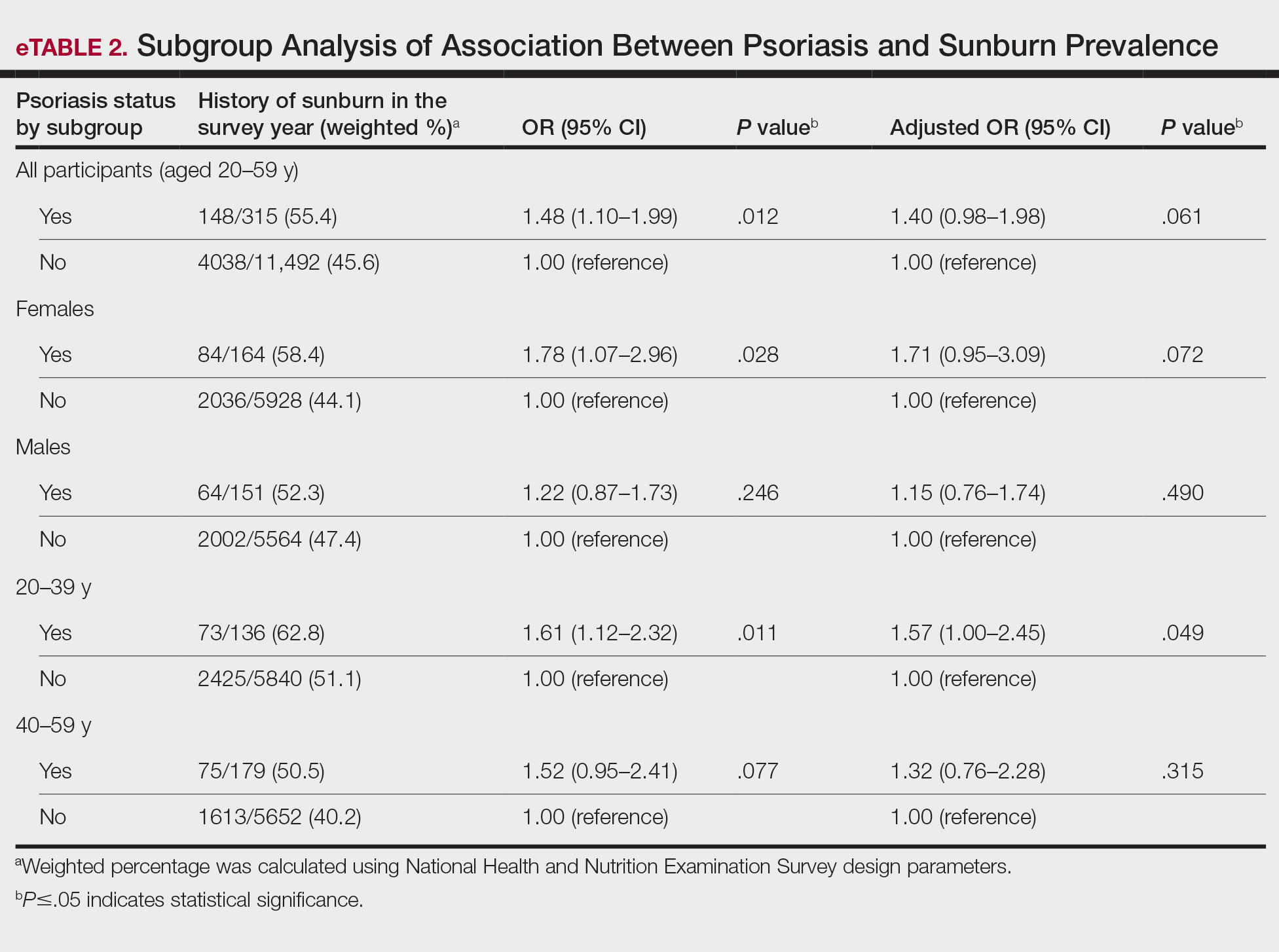

Our analysis initially included 9982 participants; 14 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and impaired mobility and were excluded. The prevalence of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis was 17.1% compared with 10.9% among those without psoriasis (Table 1). There was a significant association between psoriasis and impaired mobility among patients aged 45 to 80 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.54; 95% CI, 1.04- 2.29; P=.032)(Table 2). Analyses of subgroups yielded no statistically significant results.

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mobility between individuals with psoriasis compared with the general population, which remained significant when controlling for arthritis, obesity, and diabetes (P=.032). This may be the result of several influences. First, the location of the psoriasis may impact mobility. Plantar psoriasis—a manifestation on the soles of the feet—can cause discomfort and pain, which can hinder walking and standing.5 Second, a study by Lasselin et al6 found that systemic inflammation contributes to mobility impairment through alterations in gait and posture, which suggests that the inflammatory processes inherent in psoriasis could intrinsically modify walking speed and stride, potentially exacerbating mobility difficulties independent of other comorbid conditions. These findings suggest that psoriasis may disproportionately affect individuals with impaired mobility, independent of comorbid arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

These findings have broad implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion. They should prompt us to consider the practical challenges faced by this patient population and the ways that we can address barriers to care. Offering telehealth appointments, making primary care referrals for impaired mobility workups, and advising patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions are good places to start.

Limitations to our study include the lack of specificity in the survey question, self-reporting bias, and the inability to control for the psoriasis location. Further investigations are warranted in large, representative US adult populations to assess the implications of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

- Zheng Q, Sun XY, Miao X, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of prevalent psoriasis: A MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11394. doi: 10.1097 /MD.0000000000011394

- Mullin AE, Coe IR, Gooden EA, et al. Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility: from organizational responsibility to leadership competency. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021;34311-315. doi: 10.1177/08404704211038232

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Romani M, Biela G, Farr K, et al. Plantar psoriasis: a review of the literature. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2021;38:541-552. doi: 10.1016 /j.cpm.2021.06.009

- Lasselin J, Sundelin T, Wayne PM, et al. Biological motion during inflammation in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;84:147-153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.019

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects individuals in various extracutaneous ways.1 Prior studies have documented a decrease in exercise intensity among patients with psoriasis2; however, few studies have specifically investigated baseline mobility in this population. Baseline mobility denotes an individual’s fundamental ability to walk or move around without assistance of any kind. Impaired mobility—when baseline mobility is compromised—is an aspect of the wider diversity, equity, and inclusion framework that underscores the significance of recognizing challenges and promoting inclusive measures, both at the point of care and in research.3 study sought to analyze the relationship between psoriasis and baseline mobility among US adults (aged 45 to 80 years) utilizing the latest data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database for psoriasis.4 We used three 2-year cycles of NHANES data to create a 2009-2014 dataset.

The overall NHANES response rate among adults aged 45 to 80 years between 2009 and 2014 was 67.9%. Patients were categorized as having impaired mobility if they responded “yes” to the following question: “Because of a health problem, do you have difficulty walking without using any special equipment?” Psoriasis status was assessed by the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18.0 software (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and impaired mobility. Age, income, education, sex, race, tobacco use, diabetes status, body mass index, and arthritis status were controlled for in our models.

Our analysis initially included 9982 participants; 14 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and impaired mobility and were excluded. The prevalence of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis was 17.1% compared with 10.9% among those without psoriasis (Table 1). There was a significant association between psoriasis and impaired mobility among patients aged 45 to 80 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.54; 95% CI, 1.04- 2.29; P=.032)(Table 2). Analyses of subgroups yielded no statistically significant results.

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mobility between individuals with psoriasis compared with the general population, which remained significant when controlling for arthritis, obesity, and diabetes (P=.032). This may be the result of several influences. First, the location of the psoriasis may impact mobility. Plantar psoriasis—a manifestation on the soles of the feet—can cause discomfort and pain, which can hinder walking and standing.5 Second, a study by Lasselin et al6 found that systemic inflammation contributes to mobility impairment through alterations in gait and posture, which suggests that the inflammatory processes inherent in psoriasis could intrinsically modify walking speed and stride, potentially exacerbating mobility difficulties independent of other comorbid conditions. These findings suggest that psoriasis may disproportionately affect individuals with impaired mobility, independent of comorbid arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

These findings have broad implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion. They should prompt us to consider the practical challenges faced by this patient population and the ways that we can address barriers to care. Offering telehealth appointments, making primary care referrals for impaired mobility workups, and advising patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions are good places to start.

Limitations to our study include the lack of specificity in the survey question, self-reporting bias, and the inability to control for the psoriasis location. Further investigations are warranted in large, representative US adult populations to assess the implications of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory condition that affects individuals in various extracutaneous ways.1 Prior studies have documented a decrease in exercise intensity among patients with psoriasis2; however, few studies have specifically investigated baseline mobility in this population. Baseline mobility denotes an individual’s fundamental ability to walk or move around without assistance of any kind. Impaired mobility—when baseline mobility is compromised—is an aspect of the wider diversity, equity, and inclusion framework that underscores the significance of recognizing challenges and promoting inclusive measures, both at the point of care and in research.3 study sought to analyze the relationship between psoriasis and baseline mobility among US adults (aged 45 to 80 years) utilizing the latest data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) database for psoriasis.4 We used three 2-year cycles of NHANES data to create a 2009-2014 dataset.

The overall NHANES response rate among adults aged 45 to 80 years between 2009 and 2014 was 67.9%. Patients were categorized as having impaired mobility if they responded “yes” to the following question: “Because of a health problem, do you have difficulty walking without using any special equipment?” Psoriasis status was assessed by the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had psoriasis?” Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed using Stata/SE 18.0 software (StataCorp LLC) to assess the relationship between psoriasis and impaired mobility. Age, income, education, sex, race, tobacco use, diabetes status, body mass index, and arthritis status were controlled for in our models.

Our analysis initially included 9982 participants; 14 did not respond to questions assessing psoriasis and impaired mobility and were excluded. The prevalence of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis was 17.1% compared with 10.9% among those without psoriasis (Table 1). There was a significant association between psoriasis and impaired mobility among patients aged 45 to 80 years after adjusting for potential confounding variables (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.54; 95% CI, 1.04- 2.29; P=.032)(Table 2). Analyses of subgroups yielded no statistically significant results.

Our study demonstrated a statistically significant difference in mobility between individuals with psoriasis compared with the general population, which remained significant when controlling for arthritis, obesity, and diabetes (P=.032). This may be the result of several influences. First, the location of the psoriasis may impact mobility. Plantar psoriasis—a manifestation on the soles of the feet—can cause discomfort and pain, which can hinder walking and standing.5 Second, a study by Lasselin et al6 found that systemic inflammation contributes to mobility impairment through alterations in gait and posture, which suggests that the inflammatory processes inherent in psoriasis could intrinsically modify walking speed and stride, potentially exacerbating mobility difficulties independent of other comorbid conditions. These findings suggest that psoriasis may disproportionately affect individuals with impaired mobility, independent of comorbid arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

These findings have broad implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion. They should prompt us to consider the practical challenges faced by this patient population and the ways that we can address barriers to care. Offering telehealth appointments, making primary care referrals for impaired mobility workups, and advising patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions are good places to start.

Limitations to our study include the lack of specificity in the survey question, self-reporting bias, and the inability to control for the psoriasis location. Further investigations are warranted in large, representative US adult populations to assess the implications of impaired mobility in patients with psoriasis.

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

- Zheng Q, Sun XY, Miao X, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of prevalent psoriasis: A MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11394. doi: 10.1097 /MD.0000000000011394

- Mullin AE, Coe IR, Gooden EA, et al. Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility: from organizational responsibility to leadership competency. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021;34311-315. doi: 10.1177/08404704211038232

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Romani M, Biela G, Farr K, et al. Plantar psoriasis: a review of the literature. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2021;38:541-552. doi: 10.1016 /j.cpm.2021.06.009

- Lasselin J, Sundelin T, Wayne PM, et al. Biological motion during inflammation in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;84:147-153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.019

- Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR, et al. Joint AAD-NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1073-1113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.11.058

- Zheng Q, Sun XY, Miao X, et al. Association between physical activity and risk of prevalent psoriasis: A MOOSE-compliant meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e11394. doi: 10.1097 /MD.0000000000011394

- Mullin AE, Coe IR, Gooden EA, et al. Inclusion, diversity, equity, and accessibility: from organizational responsibility to leadership competency. Healthc Manage Forum. 2021;34311-315. doi: 10.1177/08404704211038232

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. NHANES questionnaires, datasets, and related documentation. Accessed October 21, 2023. https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/

- Romani M, Biela G, Farr K, et al. Plantar psoriasis: a review of the literature. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2021;38:541-552. doi: 10.1016 /j.cpm.2021.06.009

- Lasselin J, Sundelin T, Wayne PM, et al. Biological motion during inflammation in humans. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;84:147-153. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.019

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

Exploring the Relationship Between Psoriasis and Mobility Among US Adults

PRACTICE POINTS

- Mobility issues are more common in patients who have psoriasis than in those who do not.

- It is important to assess patients with psoriasis for mobility issues regardless of age or comorbid conditions such as arthritis, obesity, and diabetes.

- Dermatologists can help patients with psoriasis and impaired mobility overcome potential barriers to care by incorporating telehealth services into their practices and informing patients of direct-to-home delivery of prescriptions.

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

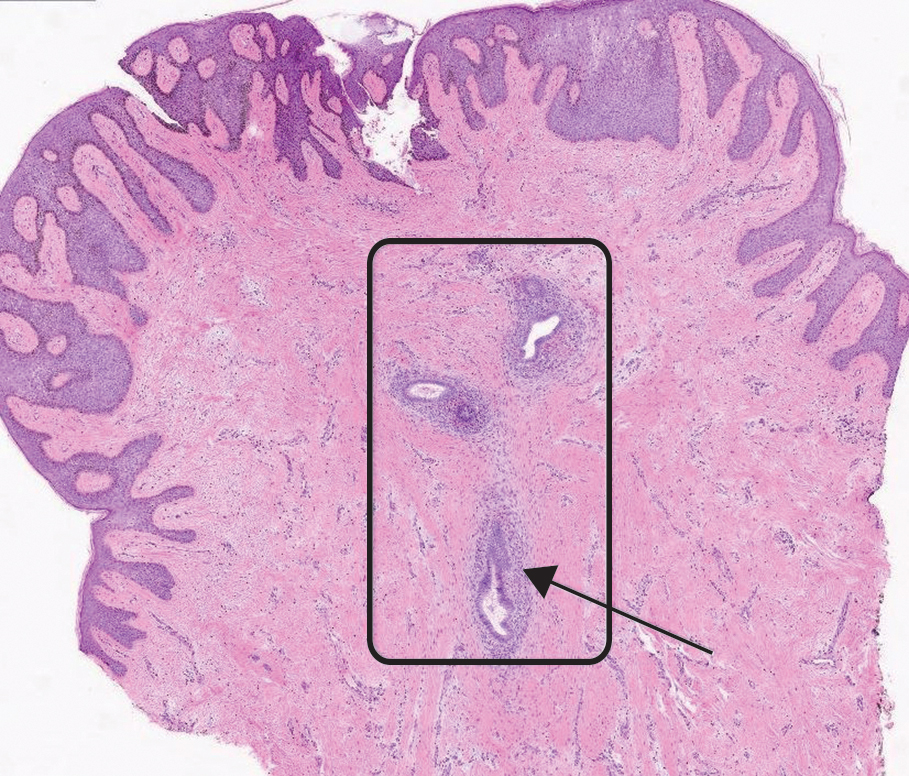

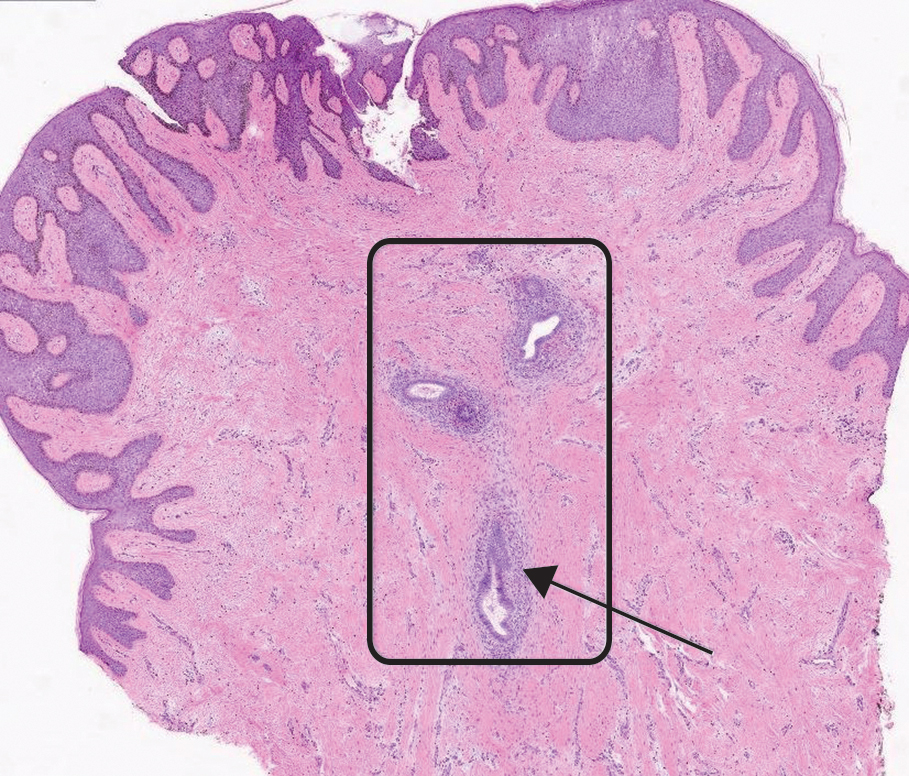

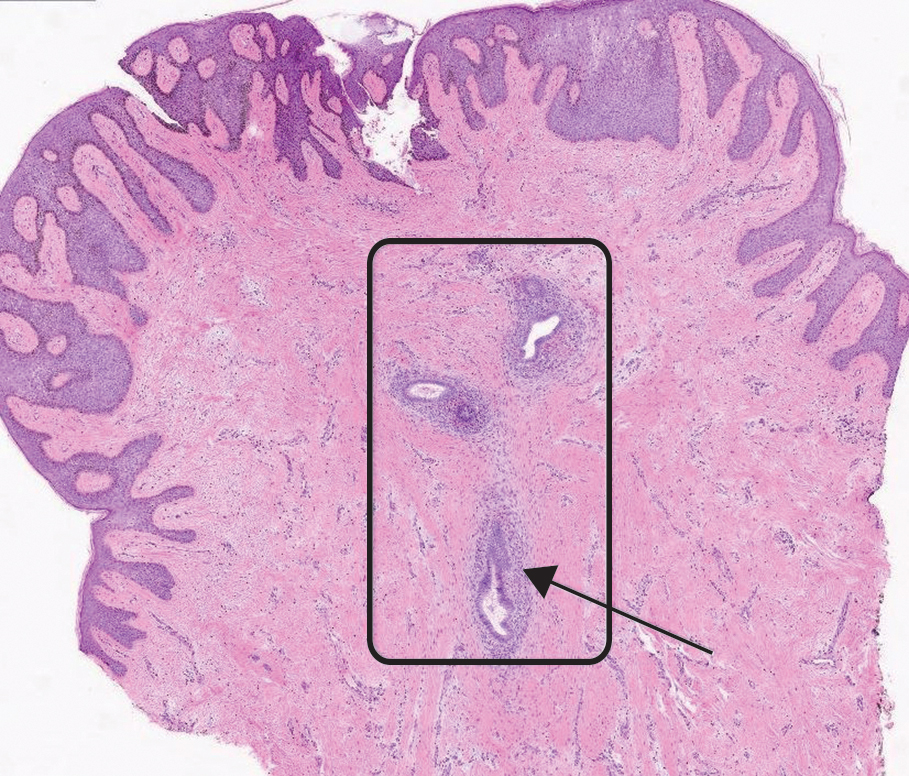

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Cutaneous Endometriosis

On histopathology, a biopsy specimen of an umbilical papule showed a dermal lymphohistiocyticrich infiltrate, hemorrhage, and ectopic endometrial glands consistent with cutaneous endometriosis (CE)(Figure). Cutaneous endometriosis is a rare condition that typically affects females of reproductive potential and is characterized by endometrial glands and stroma within the dermis and hypodermis. Cutaneous endometriosis is classified as primary or secondary. There is no surgical history of the abdomen or pelvis in primary CE. In contrast, a history of abdominopelvic surgery is the defining characteristic of secondary CE, which is more common than primary CE and typically manifests as painful red, brown, or purple papules along preexisting surgical scars of the umbilicus, lower abdomen, or pelvic region.1 Our patient may have developed secondary CE related to the laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed 10 years prior. Surgical excision is considered the definitive treatment for CE, and hormonal therapy with danazol or leuprolide may help ameliorate symptoms.1 Our patient deferred any hormonal or surgical interventions to undergo fertility treatments for pregnancy.

Cyclical bleeding and pain that coincides with menstruation is consistent with CE; however, cyclical symptoms are not always present, which can lead to delayed or incorrect diagnosis. Biopsy and histopathologic analysis are required for definitive diagnosis and are critical for distinguishing CE from other conditions. The differential diagnosis in our patient included pyogenic granuloma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, keloid, and cutaneous metastasis of a primary malignancy. Vascular lesions such as pyogenic granuloma can manifest with bleeding but have a characteristic histopathologic lobular capillary arrangement that was not present in our patient.

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a rare, slow-growing, malignant soft-tissue sarcoma that most commonly manifests on the trunk, arms, and legs.2 It is characterized by a slow-growing, indurated plaque that often is present for years and may suddenly progress into a smooth, red-brown, multinodular mass. Histopathology typically shows spindle cells infiltrating the dermis and subcutaneous tissue in storiform or whorled pattern with variations based on the tumor stage, as well as diffuse CD34 immunoreactivity.2

Keloids are dense, raised, hyperpigmented, fibrous nodules—sometimes with accompanying telangiectasias—that typically grow secondary to trauma and project past the boundaries of the initial trauma site.1 Keloids are more commonly seen in individuals with darker skin types and tend to grow larger in this population. Histopathology reveals thickened hyalinized collagen bundles, which were not seen in our patient.1

Metastatic skin lesions of the umbilicus are rare but can arise from internal malignancies including cancers of the lung, colon, and breast.3 We considered Sister Mary Joseph nodule, which is caused most commonly by metastasis of a primary gastrointestinal cancer and signifies poor prognosis. The histopathology of metastatic lesions would reveal the presence of atypical cells with cancer-specific markers. Histopathology along with the patient’s personal and family history, a comprehensive review of symptoms, and cancer screening may help with reaching the correct diagnosis.

The average duration between abdominopelvic surgery and onset of secondary CE symptoms is 3.7 to 5.3 years.4 Our patient presented 10 years post surgery and after cessation of oral contraception, which may suggest a potential role of hormonal contraception in delayed CE onset. Diagnosis of CE can be challenging due to atypical signs or symptoms, delayed onset, and lack of awareness among health care professionals. Patients with delayed diagnosis may endure multiple procedures, prolonged physical pain, and emotional distress. Furthermore, 30% to 50% of females with endometriosis experience infertility. Delayed diagnosis of CE compounded with associated age-related increase in oocyte atresia could potentially worsen fecundity as patients age.5 It is important to consider CE in the differential diagnosis of females of reproductive age who present with cyclical bleeding and abdominal or umbilical nodules.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

- James WD, Elston D, Treat JR, et al. Andrews Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 13th ed. Elsevier; 2019. Accessed March 19, 2024. https://search.worldcat.org/title/1084979207

- Hao X, Billings SD, Wu F, et al. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: update on the diagnosis and treatment. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1752.

- Komurcugil I, Arslan Z, Bal ZI, et al. Cutaneous metastases different clinical presentations: case series and review of the literature. Dermatol Reports. 2022;15:9553.

- Marras S, Pluchino N, Petignat P, et al. Abdominal wall endometriosis: an 11-year retrospective observational cohort study. Published online September 16, 2019. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol X.

- Missmer SA, Hankinson SE, Spiegelman D, et al. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:784-796.

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

Cyclically Bleeding Umbilical Papules

A 38-year-old nulligravid female with menorrhagia and dysmenorrhea presented with cyclical umbilical bleeding of 1 year’s duration. Shortly before the onset of symptoms, the patient had discontinued oral contraceptive therapy with the intent to become pregnant. She had an uncomplicated laparoscopic cholecystectomy 10 years prior, but her medical history was otherwise unremarkable. At the current presentation, physical examination revealed multilobular brown papules with serosanguineous crusting in the umbilicus.

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects 1% to 3% of the global population.1,2 Due to dysregulation of the immune system, patients with HIV who have concurrent moderate to severe psoriasis present a clinical therapeutic challenge for dermatologists. Recent guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology recommended avoiding certain systemic treatments (eg, methotrexate, cyclosporine) in patients who are HIV positive due to their immunosuppressive effects, as well as cautious use of certain biologics in populations with HIV.3 Traditional therapies for managing psoriasis in patients with HIV have included topical agents, antiretroviral therapy (ART), phototherapy, and acitretin; however, phototherapy can be logistically cumbersome for patients, and in the setting of ART, acitretin has the potential to exacerbate hypertriglyceridemia as well as other undesirable adverse effects.3

Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that has emerged as a promising alternative in patients with HIV who require treatment for psoriasis. It has demonstrated clinical efficacy in psoriasis and has minimal immunosuppressive risk.4 Despite its potential in this population, reports of apremilast used in patients who are HIV positive are rare, and these patients often are excluded from larges studies. In this study, we reviewed the literature to evaluate outcomes and adverse events in patients with HIV who underwent psoriasis treatment with apremilast.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from the inception of the database through January 2023 was conducted using the terms psoriasis, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, therapy, apremilast, and adverse events. The inclusion criteria were articles that reported patients with HIV and psoriasis undergoing treatment with apremilast with subsequent follow-up to delineate potential outcomes and adverse effects. Non–English language articles were excluded.

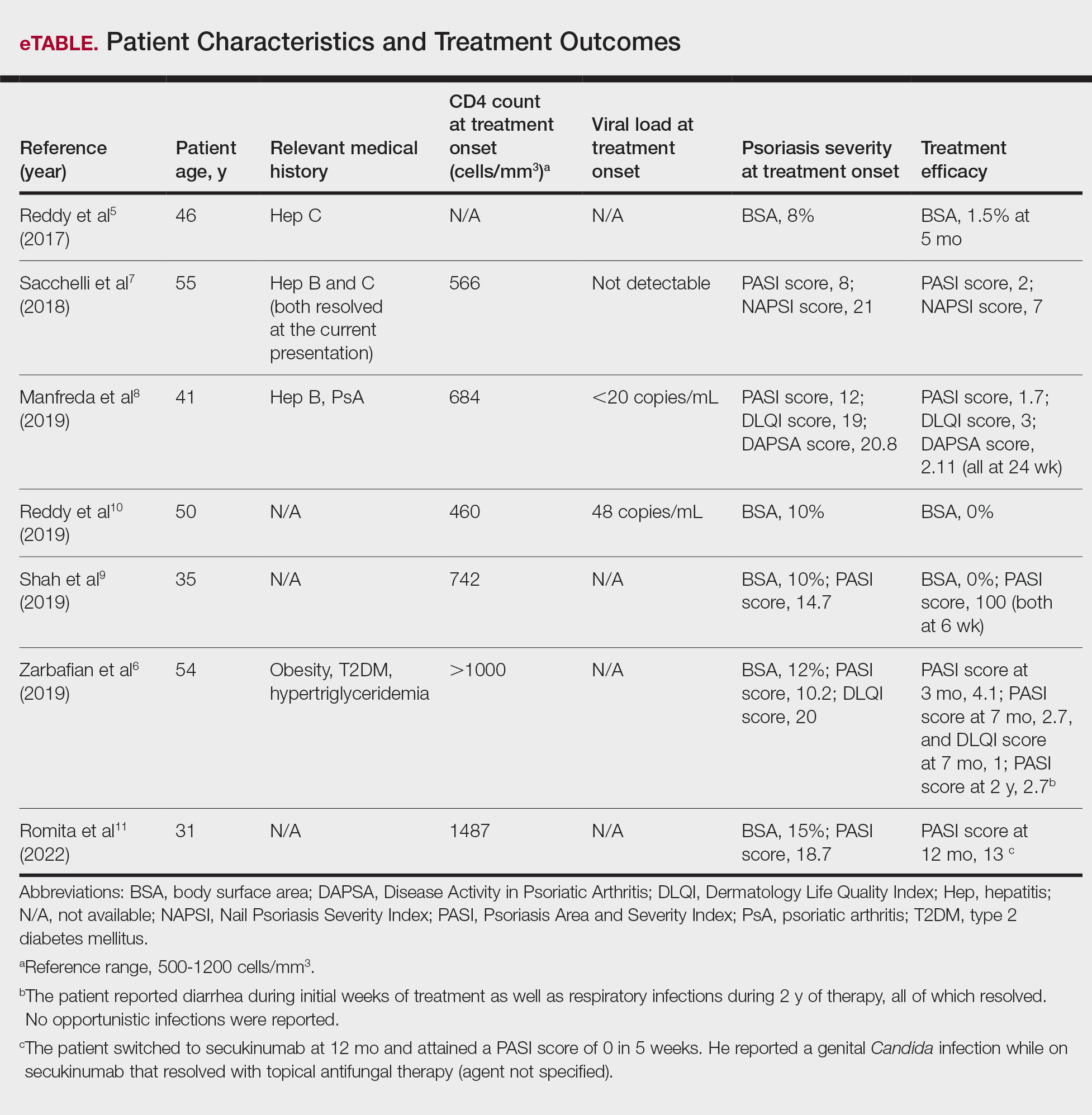

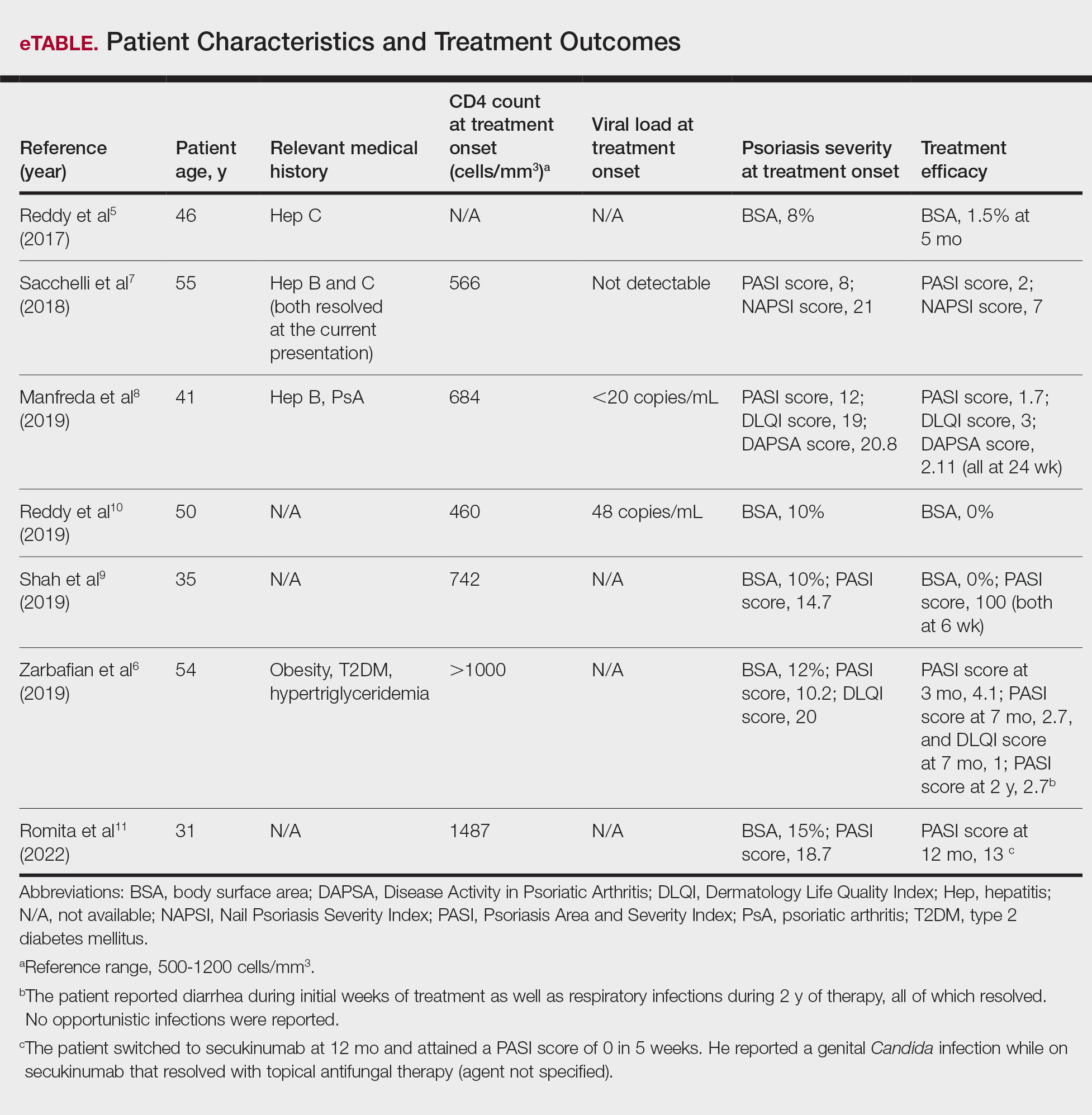

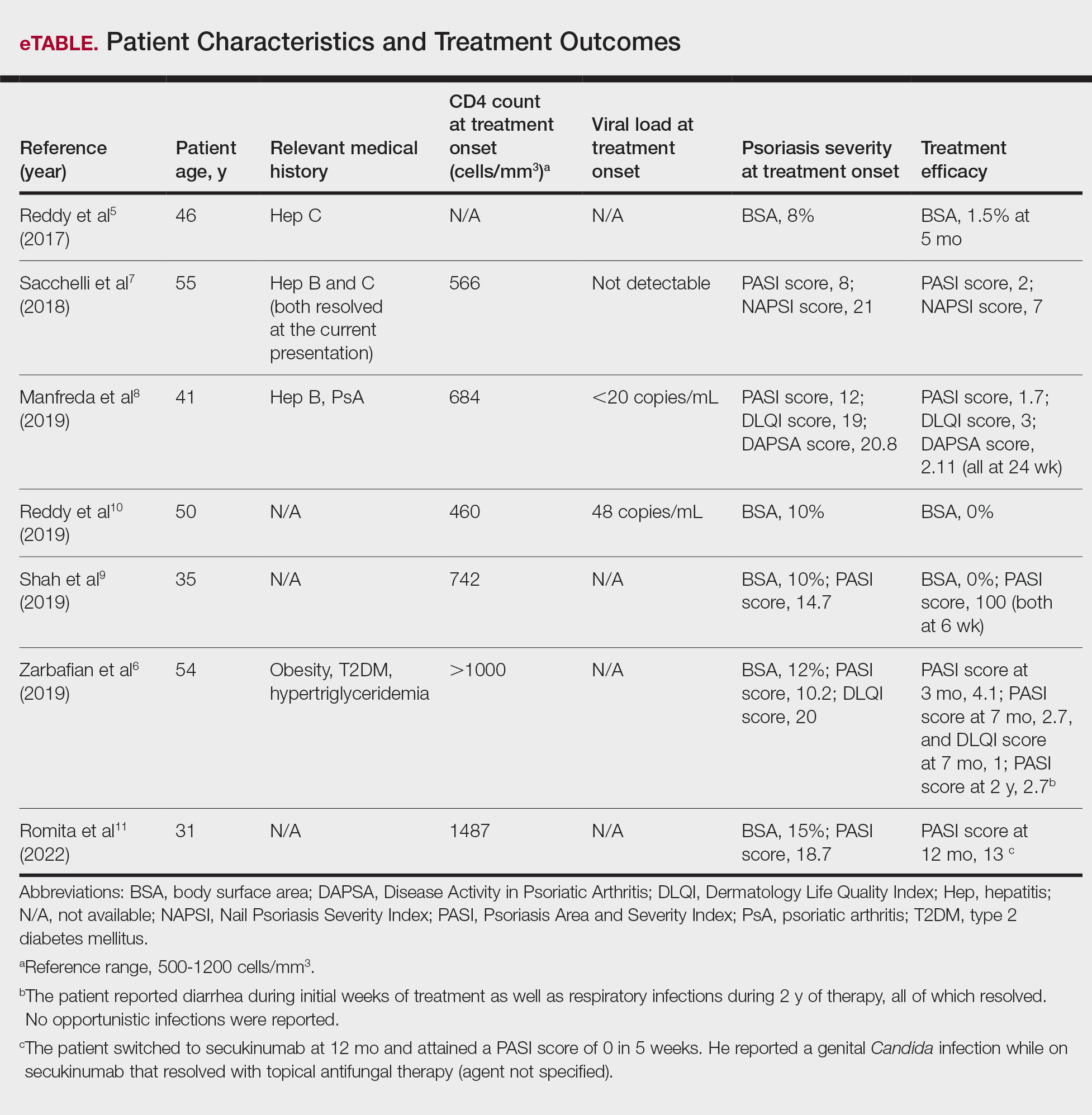

Our search of the literature yielded 7 patients with HIV and psoriasis who were treated with apremilast (eTable).5-11 All of the patients were male and ranged in age from 31 to 55 years, and all had pretreatment CD4 cell counts greater than 450 cells/mm3. All but 1 patient were confirmed to have undergone ART prior to treatment with apremilast, and all were treated using the traditional apremilast titration from 10 mg to 30 mg orally twice daily.

The mean pretreatment Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score in the patients we evaluated was 12.2, with an average reduction in PASI score of 9.3. This equated to achievement of PASI 75 or greater (ie, representing at least a 75% improvement in psoriasis) in 4 (57.1%) patients, with clinical improvement confirmed in all 7 patients (100.0%)(eTable). The average follow-up time was 9.7 months (range, 6 weeks to 24 months). Only 1 (14.3%) patient experienced any adverse effects, which included self-resolving diarrhea and respiratory infections (nonopportunistic) over a follow-up period of 2 years.6 Of note, gastrointestinal upset is common with apremilast and usually improves over time.12

Apremilast represents a safe and effective alternative systemic therapy for patients with HIV and psoriasis.4 As a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, apremilast leads to increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which restores an equilibrium between proinflammatory (eg, tumor necrosis factors, interferons, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23) and anti-inflammatory (eg, IL-10) cytokines.13 Unlike most biologics that target and inhibit a specific proinflammatory cytokine, apremilast’s homeostatic mechanism may explain its minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

In the majority of patients we evaluated, initiation of apremilast led to documented clinical improvement. It is worth noting that some patients presented with a relevant medical history and/or comorbidities such as hepatitis and metabolic conditions (eg, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia). Despite these comorbidities, initiation of apremilast therapy in these patients led to clinical improvement of psoriasis overall. Notable cases from our study included a 41-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis B and psoriatic arthritis who achieved PASI 90 after 24 weeks of apremilast therapy8; a 46-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis C who went from 8% to 1.5% body surface area affected after 5 months of treatment with apremilast5; and a 54-year-old man with concurrent obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertriglyceridemia who went from a PASI score of 10.2 to 4.1 after 3 months of apremilast treatment and maintained a PASI score of 2.7 at 2 years’ follow up (eTable).6

Limitations of this study included the small sample size and homogeneous demographic consisting only of adult males, which restrict the external validity of the findings. Despite limitations, apremilast was utilized effectively for patients with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The observed effectiveness of apremilast in multiple forms of psoriasis provides valuable insights into the drug’s versatility in this patient population.

The use of apremilast for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV represents an important therapeutic development. Its effectiveness in reducing psoriasis symptoms in these immunocompromised patients makes it a viable alternative to traditional systemic therapies that might be contraindicated in this population. While larger studies would be ideal, the exclusion of patients with HIV from clinical trials presents an obstacle and therefore makes case series and reviews helpful for clinicians in bridging the gap with respect to treatment options for these patients. Apremilast may be a safe and effective medication for patients with HIV and psoriasis who require systemic therapy to treat their skin disease.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.056

- Crowley J, Thaci D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for >156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1.

- Reddy SP, Shah VV, Wu JJ. Apremilast for a psoriasis patient with HIV and hepatitis C. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E481-E482. doi:10.1111/jdv.14301

- Zarbafian M, Cote B, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193 doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Sacchelli L, Patrizi A, Ferrara F, et al. Apremilast as therapeutic option in a HIV positive patient with severe psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12719. doi:10.1111/dth.12719

- Manfreda V, Esposito M, Campione E, et al. Apremilast efficacy and safety in a psoriatic arthritis patient affected by HIV and HBV virus infections. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:239-240. doi:10.1080/00325481.2019 .1575613

- Shah BJ, Mistry D, Chaudhary N. Apremilast in people living with HIV with psoriasis vulgaris: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:242- 244. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_633_18

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E6-E7.

- Romita P, Foti C, Calianno G, et al. Successful treatment with secukinumab in an HIV-positive psoriatic patient after failure of apremilast. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15610. doi:10.1111/dth.15610

- Zeb L, Mhaskar R, Lewis S, et al. Real-world drug survival and reasons for treatment discontinuation of biologics and apremilast in patients with psoriasis in an academic center. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14826. doi:10.1111/dth.14826

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects 1% to 3% of the global population.1,2 Due to dysregulation of the immune system, patients with HIV who have concurrent moderate to severe psoriasis present a clinical therapeutic challenge for dermatologists. Recent guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology recommended avoiding certain systemic treatments (eg, methotrexate, cyclosporine) in patients who are HIV positive due to their immunosuppressive effects, as well as cautious use of certain biologics in populations with HIV.3 Traditional therapies for managing psoriasis in patients with HIV have included topical agents, antiretroviral therapy (ART), phototherapy, and acitretin; however, phototherapy can be logistically cumbersome for patients, and in the setting of ART, acitretin has the potential to exacerbate hypertriglyceridemia as well as other undesirable adverse effects.3

Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that has emerged as a promising alternative in patients with HIV who require treatment for psoriasis. It has demonstrated clinical efficacy in psoriasis and has minimal immunosuppressive risk.4 Despite its potential in this population, reports of apremilast used in patients who are HIV positive are rare, and these patients often are excluded from larges studies. In this study, we reviewed the literature to evaluate outcomes and adverse events in patients with HIV who underwent psoriasis treatment with apremilast.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from the inception of the database through January 2023 was conducted using the terms psoriasis, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, therapy, apremilast, and adverse events. The inclusion criteria were articles that reported patients with HIV and psoriasis undergoing treatment with apremilast with subsequent follow-up to delineate potential outcomes and adverse effects. Non–English language articles were excluded.

Our search of the literature yielded 7 patients with HIV and psoriasis who were treated with apremilast (eTable).5-11 All of the patients were male and ranged in age from 31 to 55 years, and all had pretreatment CD4 cell counts greater than 450 cells/mm3. All but 1 patient were confirmed to have undergone ART prior to treatment with apremilast, and all were treated using the traditional apremilast titration from 10 mg to 30 mg orally twice daily.

The mean pretreatment Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score in the patients we evaluated was 12.2, with an average reduction in PASI score of 9.3. This equated to achievement of PASI 75 or greater (ie, representing at least a 75% improvement in psoriasis) in 4 (57.1%) patients, with clinical improvement confirmed in all 7 patients (100.0%)(eTable). The average follow-up time was 9.7 months (range, 6 weeks to 24 months). Only 1 (14.3%) patient experienced any adverse effects, which included self-resolving diarrhea and respiratory infections (nonopportunistic) over a follow-up period of 2 years.6 Of note, gastrointestinal upset is common with apremilast and usually improves over time.12

Apremilast represents a safe and effective alternative systemic therapy for patients with HIV and psoriasis.4 As a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, apremilast leads to increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which restores an equilibrium between proinflammatory (eg, tumor necrosis factors, interferons, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23) and anti-inflammatory (eg, IL-10) cytokines.13 Unlike most biologics that target and inhibit a specific proinflammatory cytokine, apremilast’s homeostatic mechanism may explain its minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

In the majority of patients we evaluated, initiation of apremilast led to documented clinical improvement. It is worth noting that some patients presented with a relevant medical history and/or comorbidities such as hepatitis and metabolic conditions (eg, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia). Despite these comorbidities, initiation of apremilast therapy in these patients led to clinical improvement of psoriasis overall. Notable cases from our study included a 41-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis B and psoriatic arthritis who achieved PASI 90 after 24 weeks of apremilast therapy8; a 46-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis C who went from 8% to 1.5% body surface area affected after 5 months of treatment with apremilast5; and a 54-year-old man with concurrent obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertriglyceridemia who went from a PASI score of 10.2 to 4.1 after 3 months of apremilast treatment and maintained a PASI score of 2.7 at 2 years’ follow up (eTable).6

Limitations of this study included the small sample size and homogeneous demographic consisting only of adult males, which restrict the external validity of the findings. Despite limitations, apremilast was utilized effectively for patients with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The observed effectiveness of apremilast in multiple forms of psoriasis provides valuable insights into the drug’s versatility in this patient population.

The use of apremilast for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV represents an important therapeutic development. Its effectiveness in reducing psoriasis symptoms in these immunocompromised patients makes it a viable alternative to traditional systemic therapies that might be contraindicated in this population. While larger studies would be ideal, the exclusion of patients with HIV from clinical trials presents an obstacle and therefore makes case series and reviews helpful for clinicians in bridging the gap with respect to treatment options for these patients. Apremilast may be a safe and effective medication for patients with HIV and psoriasis who require systemic therapy to treat their skin disease.

To the Editor:

Psoriasis is a chronic systemic inflammatory disease that affects 1% to 3% of the global population.1,2 Due to dysregulation of the immune system, patients with HIV who have concurrent moderate to severe psoriasis present a clinical therapeutic challenge for dermatologists. Recent guidelines from the American Academy of Dermatology recommended avoiding certain systemic treatments (eg, methotrexate, cyclosporine) in patients who are HIV positive due to their immunosuppressive effects, as well as cautious use of certain biologics in populations with HIV.3 Traditional therapies for managing psoriasis in patients with HIV have included topical agents, antiretroviral therapy (ART), phototherapy, and acitretin; however, phototherapy can be logistically cumbersome for patients, and in the setting of ART, acitretin has the potential to exacerbate hypertriglyceridemia as well as other undesirable adverse effects.3

Apremilast is a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor that has emerged as a promising alternative in patients with HIV who require treatment for psoriasis. It has demonstrated clinical efficacy in psoriasis and has minimal immunosuppressive risk.4 Despite its potential in this population, reports of apremilast used in patients who are HIV positive are rare, and these patients often are excluded from larges studies. In this study, we reviewed the literature to evaluate outcomes and adverse events in patients with HIV who underwent psoriasis treatment with apremilast.

A search of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE from the inception of the database through January 2023 was conducted using the terms psoriasis, human immunodeficiency virus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, therapy, apremilast, and adverse events. The inclusion criteria were articles that reported patients with HIV and psoriasis undergoing treatment with apremilast with subsequent follow-up to delineate potential outcomes and adverse effects. Non–English language articles were excluded.

Our search of the literature yielded 7 patients with HIV and psoriasis who were treated with apremilast (eTable).5-11 All of the patients were male and ranged in age from 31 to 55 years, and all had pretreatment CD4 cell counts greater than 450 cells/mm3. All but 1 patient were confirmed to have undergone ART prior to treatment with apremilast, and all were treated using the traditional apremilast titration from 10 mg to 30 mg orally twice daily.

The mean pretreatment Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score in the patients we evaluated was 12.2, with an average reduction in PASI score of 9.3. This equated to achievement of PASI 75 or greater (ie, representing at least a 75% improvement in psoriasis) in 4 (57.1%) patients, with clinical improvement confirmed in all 7 patients (100.0%)(eTable). The average follow-up time was 9.7 months (range, 6 weeks to 24 months). Only 1 (14.3%) patient experienced any adverse effects, which included self-resolving diarrhea and respiratory infections (nonopportunistic) over a follow-up period of 2 years.6 Of note, gastrointestinal upset is common with apremilast and usually improves over time.12

Apremilast represents a safe and effective alternative systemic therapy for patients with HIV and psoriasis.4 As a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, apremilast leads to increased levels of cyclic adenosine monophosphate, which restores an equilibrium between proinflammatory (eg, tumor necrosis factors, interferons, IL-2, IL-6, IL-12, IL-23) and anti-inflammatory (eg, IL-10) cytokines.13 Unlike most biologics that target and inhibit a specific proinflammatory cytokine, apremilast’s homeostatic mechanism may explain its minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

In the majority of patients we evaluated, initiation of apremilast led to documented clinical improvement. It is worth noting that some patients presented with a relevant medical history and/or comorbidities such as hepatitis and metabolic conditions (eg, obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridemia). Despite these comorbidities, initiation of apremilast therapy in these patients led to clinical improvement of psoriasis overall. Notable cases from our study included a 41-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis B and psoriatic arthritis who achieved PASI 90 after 24 weeks of apremilast therapy8; a 46-year-old man with concurrent hepatitis C who went from 8% to 1.5% body surface area affected after 5 months of treatment with apremilast5; and a 54-year-old man with concurrent obesity, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and hypertriglyceridemia who went from a PASI score of 10.2 to 4.1 after 3 months of apremilast treatment and maintained a PASI score of 2.7 at 2 years’ follow up (eTable).6

Limitations of this study included the small sample size and homogeneous demographic consisting only of adult males, which restrict the external validity of the findings. Despite limitations, apremilast was utilized effectively for patients with both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. The observed effectiveness of apremilast in multiple forms of psoriasis provides valuable insights into the drug’s versatility in this patient population.

The use of apremilast for treatment of psoriasis in patients with HIV represents an important therapeutic development. Its effectiveness in reducing psoriasis symptoms in these immunocompromised patients makes it a viable alternative to traditional systemic therapies that might be contraindicated in this population. While larger studies would be ideal, the exclusion of patients with HIV from clinical trials presents an obstacle and therefore makes case series and reviews helpful for clinicians in bridging the gap with respect to treatment options for these patients. Apremilast may be a safe and effective medication for patients with HIV and psoriasis who require systemic therapy to treat their skin disease.

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.056

- Crowley J, Thaci D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for >156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1.

- Reddy SP, Shah VV, Wu JJ. Apremilast for a psoriasis patient with HIV and hepatitis C. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E481-E482. doi:10.1111/jdv.14301

- Zarbafian M, Cote B, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193 doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Sacchelli L, Patrizi A, Ferrara F, et al. Apremilast as therapeutic option in a HIV positive patient with severe psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12719. doi:10.1111/dth.12719

- Manfreda V, Esposito M, Campione E, et al. Apremilast efficacy and safety in a psoriatic arthritis patient affected by HIV and HBV virus infections. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:239-240. doi:10.1080/00325481.2019 .1575613

- Shah BJ, Mistry D, Chaudhary N. Apremilast in people living with HIV with psoriasis vulgaris: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:242- 244. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_633_18

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E6-E7.

- Romita P, Foti C, Calianno G, et al. Successful treatment with secukinumab in an HIV-positive psoriatic patient after failure of apremilast. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15610. doi:10.1111/dth.15610

- Zeb L, Mhaskar R, Lewis S, et al. Real-world drug survival and reasons for treatment discontinuation of biologics and apremilast in patients with psoriasis in an academic center. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14826. doi:10.1111/dth.14826

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001

- Rachakonda TD, Schupp CW, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis prevalence among adults in the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:512-516. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2013.11.013

- Parisi R, Symmons DP, Griffiths CE, et al; Identification and Management of Psoriasis and Associated ComorbidiTy (IMPACT) project team. Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:377-385. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.339

- Kaushik SB, Lebwohl MG. Psoriasis: which therapy for which patient: focus on special populations and chronic infections. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:43-53. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.06.056

- Crowley J, Thaci D, Joly P, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of apremilast in patients with psoriasis: pooled safety analysis for >156 weeks from 2 phase 3, randomized, controlled trials (ESTEEM 1 and 2). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77:310-317.e1.

- Reddy SP, Shah VV, Wu JJ. Apremilast for a psoriasis patient with HIV and hepatitis C. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:E481-E482. doi:10.1111/jdv.14301

- Zarbafian M, Cote B, Richer V. Treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis with apremilast over 2 years in the context of long-term treated HIV infection: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2019;7:2050313X19845193. doi:10.1177/2050313X19845193 doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.01.052

- Sacchelli L, Patrizi A, Ferrara F, et al. Apremilast as therapeutic option in a HIV positive patient with severe psoriasis. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12719. doi:10.1111/dth.12719

- Manfreda V, Esposito M, Campione E, et al. Apremilast efficacy and safety in a psoriatic arthritis patient affected by HIV and HBV virus infections. Postgrad Med. 2019;131:239-240. doi:10.1080/00325481.2019 .1575613

- Shah BJ, Mistry D, Chaudhary N. Apremilast in people living with HIV with psoriasis vulgaris: a case report. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:242- 244. doi:10.4103/ijd.IJD_633_18

- Reddy SP, Lee E, Wu JJ. Apremilast and phototherapy for treatment of psoriasis in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis. 2019;103:E6-E7.

- Romita P, Foti C, Calianno G, et al. Successful treatment with secukinumab in an HIV-positive psoriatic patient after failure of apremilast. Dermatol Ther. 2022;35:E15610. doi:10.1111/dth.15610

- Zeb L, Mhaskar R, Lewis S, et al. Real-world drug survival and reasons for treatment discontinuation of biologics and apremilast in patients with psoriasis in an academic center. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14826. doi:10.1111/dth.14826

- Schafer P. Apremilast mechanism of action and application to psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Biochem Pharmacol. 2012;83:1583-1590. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2012.01.001

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

Apremilast Treatment Outcomes and Adverse Events in Psoriasis Patients With HIV

PRACTICE POINT

- For patients with HIV who require systemic therapy for psoriasis, apremilast may provide an effective and safe therapeutic option, with minimal immunosuppressive adverse effects.

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

Oral Biologics: The New Wave for Treating Psoriasis

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

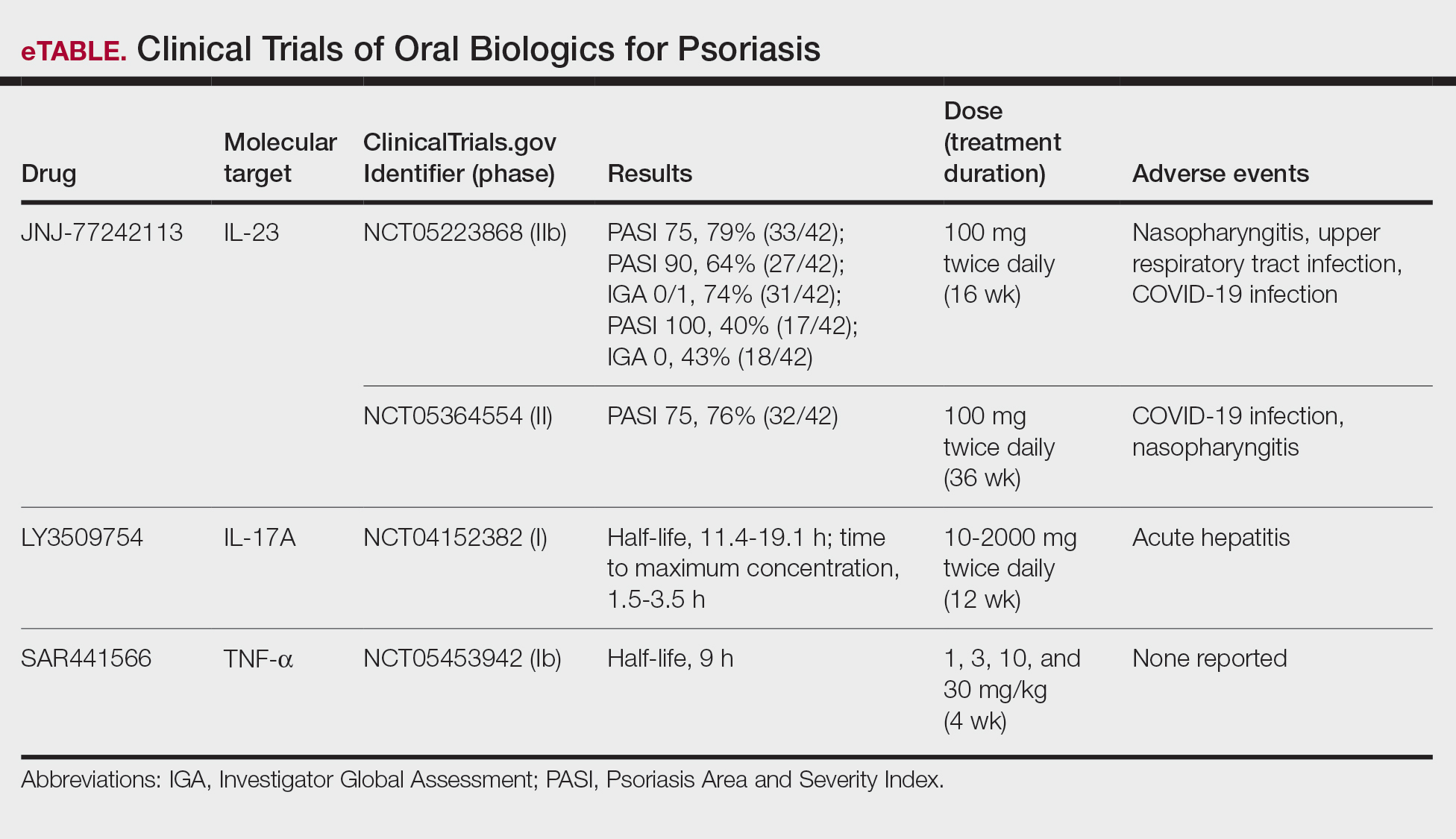

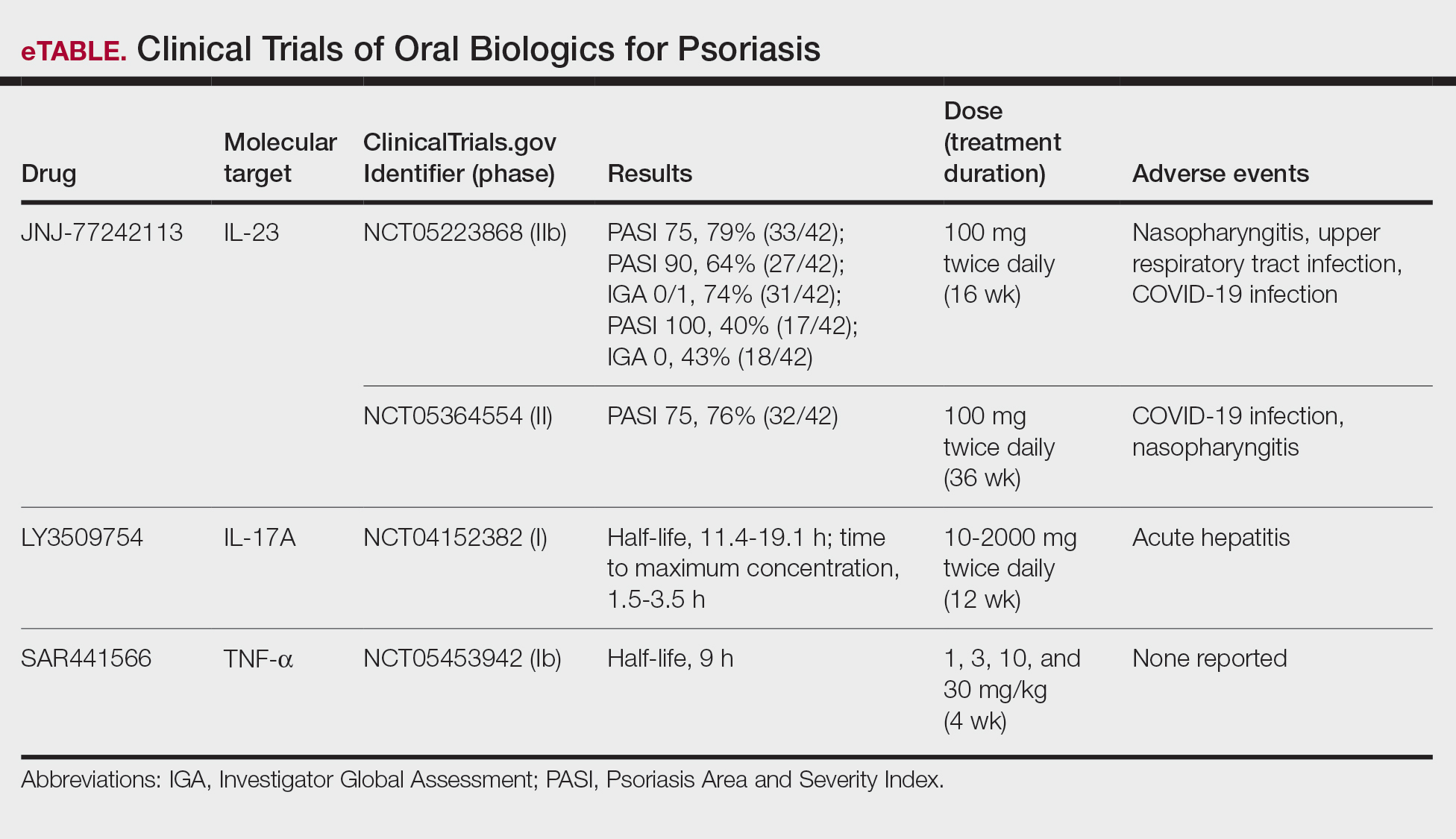

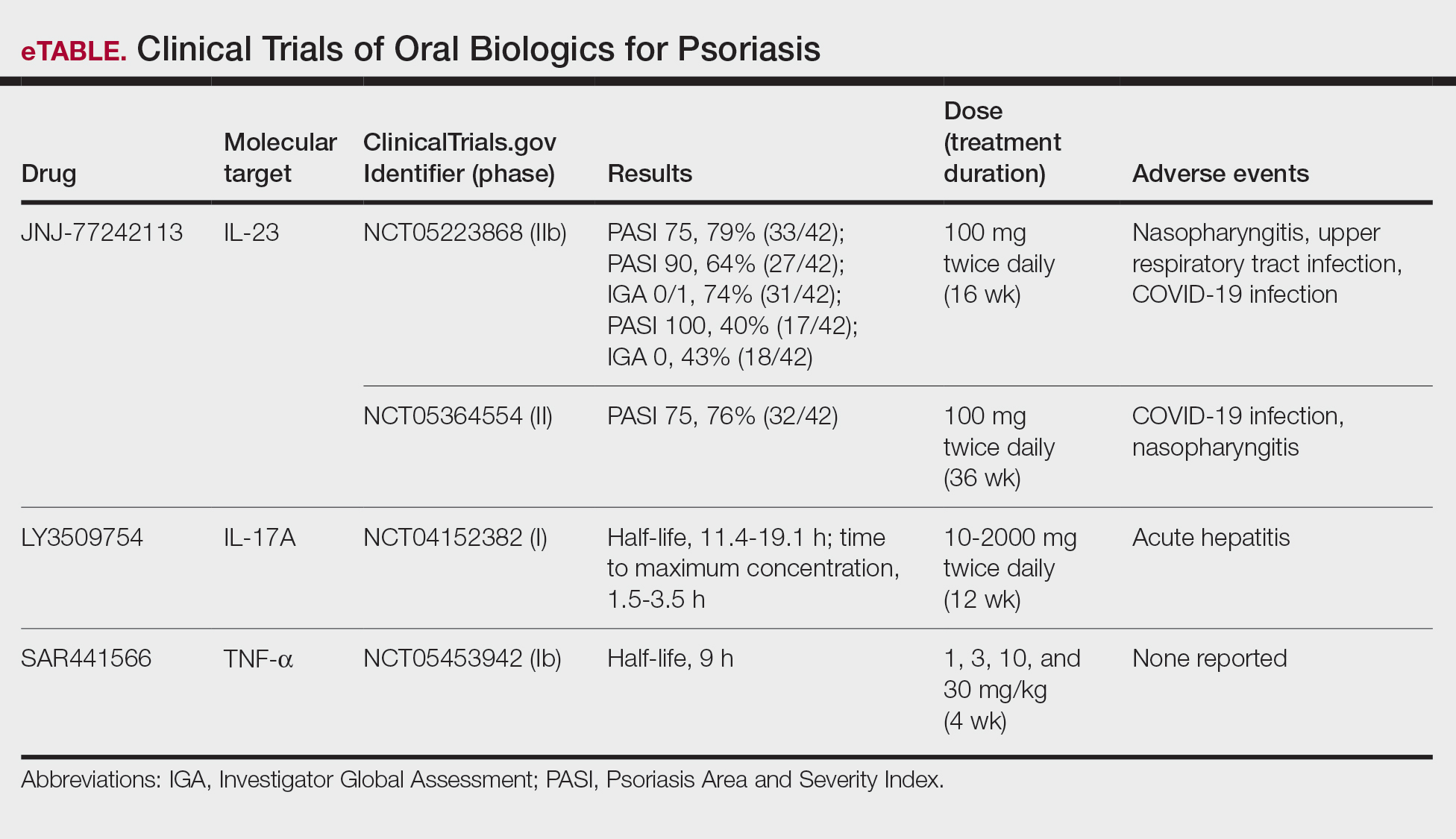

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

Biologic therapies have transformed the treatment of psoriasis. Current biologics approved for psoriasis include monoclonal antibodies targeting various pathways: tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept), the p40 subunit common to IL-12 and IL-23 (ustekinumab), the p19 subunit of IL-23 (guselkumab, tildrakizumab, risankizumab), IL-17A (secukinumab, ixekizumab), IL-17 receptor A (brodalumab), and dual IL-17A/IL-17F inhibition (bimekizumab). Recent research showed that risankizumab achieved the highest Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) 90 scores in short- and long-term treatment periods (4 and 16 weeks, respectively) compared to other biologics, and IL-23 inhibitors demonstrated the lowest short- and long-term adverse event rates and the most favorable long-term risk-benefit profile compared to IL-17, IL-12/23, and TNF-α inhibitors.1

Although these monoclonal antibodies have revolutionized psoriasis treatment, they are large proteins that must be administered subcutaneously or via intravenous injection. Emerging biologics are smaller proteins administered orally via a tablet or pill. In clinical trials, oral biologics have demonstrated efficacy (eTable), suggesting that oral biologics may be the future for psoriasis treatment, as this noninvasive delivery method may help improve patient compliance with treatment.

A major inflammatory pathway in psoriasis, IL-23 has been an effective and safe drug target. The novel oral IL-23 inhibitor, JNJ-2113, was discovered in 2017 and currently is being compared to deucravacitinib in the phase III ICONIC-LEAD trial (ClinicalTrials. gov Identifier NCT06095115) in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.2,3 In the phase IIb FRONTIER 1 trial, treatment with either 3 once-daily (25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg) and 2 twice-daily (25 mg, 100 mg) doses of JNJ-2113 led to significant improvements in PASI 75 response at 16 weeks compared to placebo (P<.001).4 In the phase IIb long-term extension FRONTIER 2 trial, JNJ-2113 maintained high rates of skin clearance through 52 weeks in adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis, with the highest PASI 75 response observed in the 100-mg twice-daily group (32/42 [76.2%]).5 Responses were maintained through week 52 for all JNJ-2113 treatment groups for PASI 90 and PASI 100 endpoints. In addition to ICONIC-LEAD, JNJ-2113 is being evaluated in the phase III multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial ICONIC-TOTAL (NCT06095102) in patients with special area psoriasis and ANTHEM-UC (NCT06049017) in patients with ulcerative colitis to evaluate its efficacy and safety. The most common adverse events associated with JNJ-77242113 were mild to moderate and included COVID-19 infection and nasopharyngitis.6 Higher rates of COVID-19 infection likely were due to immune compromise in the setting of the recent pandemic. Similar percentages of at least 1 adverse event were found in JNJ-77242113 and placebo groups (52%-58.6% and 51%-65.7%, respectively).4,5,7

An orally administered small-molecule inhibitor of IL-17A, LY3509754, may represent a convenient alternative to IL-17A–

The small potent molecule SAR441566 inhibits TNF-α by stabilizing an asymmetrical form of the soluble TNF trimer. As the asymmetrical trimer is the biologically active form of TNF-α, stabilization of the trimer compromises downstream signaling and inhibits the functions of TNF-α in vitro and in vivo. Recently, SAR441566 was found to be safe and well tolerated in healthy participants, showing efficacy in mild to moderate psoriasis in a phase Ib trial.9 A phase II trial of SAR441566 (NCT06073119) is being developed to create a more convenient orally bioavailable treatment option for patients with psoriasis compared to established biologic drugs targeting TNF-α.10

Few trials have focused on investigating the antipsoriatic effects of orally administered small molecules. Some of these small molecules can enter cells and inhibit the activation of T lymphocytes, leukocyte trafficking, leukotriene activity/production and angiogenesis, and promote apoptosis. Oral administration of small molecules is the future of effective and affordable psoriasis treatment, but safety and efficacy must first be assessed in clinical trials. JNJ-77242113 has shown a more promising safety profile, has recently undergone phase III trials, and may represent the newest wave for psoriasis treatment. While LY3509754 had a strong pharmacokinetics profile, it was poorly tolerated, and study participants' laboratory results suggested the drug to be hepatotoxic.8 SAR441566 has been shown to be safe and well tolerated in treating psoriasis, and phase II readouts are expected later in 2025. We can expect a new wave of psoriasis treatments with emerging oral therapies.

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001

- New data shows JNJ-2113, the first and only investigational targeted oral peptide, maintained skin clearance in moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis through one year. Johnson & Johnson website. March 9, 2024. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.jnj.com/media-center/press-releases/new-data-shows-jnj-2113-the-first-and-only-investigational-targeted-oral-peptide-maintained-skin-clearance-in-moderate-to-severe-plaque-psoriasis-through-one-year

- Drakos A, Torres T, Vender R. Emerging oral therapies for the treatment of psoriasis: a review of pipeline agents. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:111. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics16010111

- Bissonnette R. A phase 2, randomized, placebo-controlled, dose -ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate -to-severe plaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 1. Presented at: 25th World Congress of Dermatology; July 3, 2023; Suntec City, Singapore.

- Ferris L. S026. A phase 2b, long-term extension, dose-ranging study of oral JNJ-77242113 for the treatment of moderate-to-severeplaque psoriasis: FRONTIER 2. Presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology; San Diego, California; March 8-12, 2024.

- Inc PT. Protagonist announces two new phase 3 ICONIC studies in psoriasis evaluating JNJ-2113 in head-to-head comparisons with deucravacitinib. ACCESSWIRE website. November 27, 2023. Accessed August 29, 2024. https://www.accesswire.com/810075/protagonist-announces-two-new-phase-3-iconic-studies-in-psoriasis-evaluating-jnj-2113-in-head-to-head-comparisons-with-deucravacitinib

- Bissonnette R, Pinter A, Ferris LK, et al. An oral interleukin-23-receptor antagonist peptide for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:510-521. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2308713

- Datta-Mannan A, Regev A, Coutant DE, et al. Safety, tolerability, and pharmacokinetics of an oral small molecule inhibitor of IL-17A (LY3509754): a phase I randomized placebo-controlled study. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2024;115:1152-1161. doi:10.1002/cpt.3185

- Vugler A, O’Connell J, Nguyen MA, et al. An orally available small molecule that targets soluble TNF to deliver anti-TNF biologic-like efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:1037983. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.1037983

- Sanofi pipeline transformation to accelerate growth driven by record number of potential blockbuster launches, paving the way to industry leadership in immunology. News release. Sanofi; New York: Sanofi; Dec 7, 2023. https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2023/2023-12-07-02-30-00-2792186

- Wride AM, Chen GF, Spaulding SL, et al. Biologics for psoriasis. Dermatol Clin. 2024;42:339-355. doi:10.1016/j.det.2024.02.001