User login

Higher rates of PTSD, BPD in transgender vs. cisgender psych patients

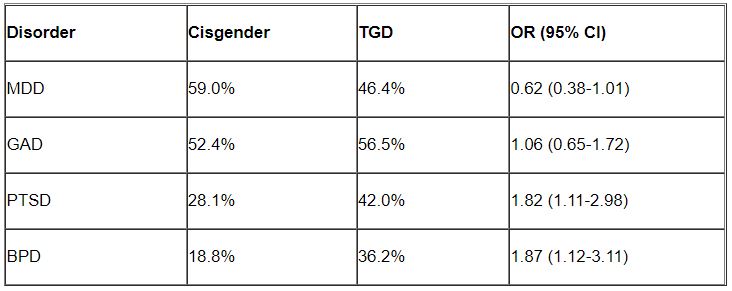

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.

Dr. Zimmerman said that there was an additional motive for conducting the study. “There has been discussion in the field as to whether or not transgender or gender-diverse individuals all have borderline personality disorder, but that hasn’t been our clinical impression.”

Rather, Dr. Zimmerman and colleagues believe TGD people “may have had more difficult childhoods and more difficult adjustments in society because of societal attitudes and have to deal with that stress, whether it be microaggressions or overt bullying and aggression.” The study was designed to investigate this issue.

In addition, studies conducted in primary care programs in individuals seeking gender-affirming surgery have “reported a limited number of psychiatric diagnoses, but we were wondering whether, amongst psychiatric patients specifically, there were differences in diagnostic profiles between transgender and gender-diverse patients and cisgender patients. If so, what might the implications be for providing care for this population?”

TGD not synonymous with borderline

To investigate, the researchers administered semistructured diagnostic interviews for DSM-IV disorders to 2,212 psychiatric patients (66% cisgender women, 30.8% cisgender men, 3.1% TGD; mean [standard deviation] age 36.7 [14.4] years) presenting to the Rhode Island Hospital Department of Psychiatry Partial Hospital Program between April 2014 and January 2021.

Patients also completed a demographic questionnaire including their assigned sex at birth and their current gender identity.

Most patients (44.9%) were single, followed by 23.5% who were married, 14.1% living in a relationship as if married, 12.0% divorced, 3.6% separated, and 1.9% widowed.

Almost three-quarters of participants (73.2%) identified as White, followed by Hispanic (10.7%), Black (6.7%), “other” or a combination of racial/ethnic backgrounds (6.6%), and Asian (2.7%).

There were no differences between cisgender and TGD groups in terms of race or education, but the TGD patients were significantly younger compared with their cisgender counterparts and were significantly more likely to have never been married.

The average number of psychiatric diagnoses in the sample was 3.05 (± 1.73), with TGD patients having a larger number of psychiatric diagnoses than did their cisgender peers (an average of 3.54 ± 1.88 vs. 3.04 ± 1.72, respectively; t = 2.37; P = .02).

Major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) were the most common disorders among both cisgender and TGD patients. However, after controlling for age, the researchers found that TGD patients were significantly more likely than were the cisgender patients to be diagnosed with PTSD and BPD (P < .05 for both).

“Of note, only about one-third of the TGD individuals were diagnosed with BPD, so it is important to realize that transgender or gender-diverse identity is not synonymous with BPD, as some have suggested,” noted Dr. Zimmerman, who is also the director of the outpatient division at the Partial Hospital Program, Rhode Island Hospital.

A representative sample?

Commenting on the study, Jack Drescher, MD, distinguished life fellow of the American Psychiatric Association and clinical professor of psychiatry, Columbia University, New York, called the findings “interesting” but noted that a limitation of the study is that it included “a patient population with likely more severe psychiatric illness, since they were all day hospital patients.”

The question is whether similar findings would be obtained in a less severely ill population, said Dr. Drescher, who is also a senior consulting analyst for sexuality and gender at Columbia University and was not involved with the study. “The patients in the study may not be representative of the general population, either cisgender or transgender.”

Dr. Drescher was “not surprised” by the finding regarding PTSD because the finding “is consistent with our understanding of the kinds of traumas that transgender people go through in day-to-day life.”

He noted that some people misunderstand the diagnostic criterion in BPD of identity confusion and think that because people with gender dysphoria may be confused about their identity, it means that all people who are transgender have borderline personality disorder, “but that’s not true.”

Dr. Zimmerman agreed. “The vast majority of individuals with BPD do not have a transgender or gender-diverse identity, and TGD should not be equated with BPD,” he said.

No source of study funding was disclosed. Dr. Zimmerman and coauthors and Dr. Drescher report no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL PSYCHIATRY

Borderline personality disorder raises relapse risk for MDD patients after ECT

ECT has demonstrated effectiveness for treatment of unipolar and bipolar major depression, but relapses within 6 months are frequent, and potential factors affecting relapse have not been well studied, wrote Matthieu Hein, MD, PhD, of Erasme Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles, and colleagues.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a common comorbidity among individuals with major depressive disorder, and previous research suggests a possible negative effect of BPD on ECT response in MDD patients, they wrote.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the researchers recruited 68 females and 41 males aged 18 years and older with diagnosed MDD who had partial or complete response to ECT after receiving treatment at a single center. Approximately two-thirds of the patients were aged 50 years and older, and 22 met criteria for BPD. The ECT consisted of three sessions per week; the total number of sessions ranged from 6 to 18.

The primary outcome was relapse at 6 months after ECT treatment. Relapse was defined as a score of 16 or higher on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in combination with a mean absolute increase of at least 10 points from the psychiatric interview at the end of the ECT.

Relapse rates at 6 months were 37.6% for the study population overall, but significantly higher for those with BPD, compared with those without BPD (72.7% vs. 28.7%; P < .001).

In a multivariate analysis, adjusting for age, gender, and mood stabilizer use after ECT, relapse was approximately four times more likely among individuals with BPD, compared with those without (hazard ratio, 4.14). No significant association appeared between increased relapse and other comorbid personality disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol or substance use disorders, or hospitalization during the ECT treatment period.

Potential reasons for the increased relapse risk among individuals with MDD and BPD include the younger age of the individuals with BPD, which has been shown to increase MDD relapse risk; the direct negative impact of BPD on mental functioning; and the documented tendency to poor treatment adherence, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“Given these different elements, it seems important to screen more systematically for BPD in major depressed individuals treated with ECT in order to allow the implementation of more effective prevention strategies for relapse within 6 months in this particular subpopulation,” they emphasized.

“The demonstration of this higher risk of relapse within 6 months associated with BPD in major depressed individuals treated with ECT could open new therapeutic perspectives to allow better maintenance of euthymia in this particular subpopulation,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the focus on only BPD, which may not generalize to other personality disorders, the researchers noted.

However, the results support data from previous studies and highlight the need for more systematic BPD screening in MDD patients to prevent relapse after ECT, they said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

ECT has demonstrated effectiveness for treatment of unipolar and bipolar major depression, but relapses within 6 months are frequent, and potential factors affecting relapse have not been well studied, wrote Matthieu Hein, MD, PhD, of Erasme Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles, and colleagues.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a common comorbidity among individuals with major depressive disorder, and previous research suggests a possible negative effect of BPD on ECT response in MDD patients, they wrote.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the researchers recruited 68 females and 41 males aged 18 years and older with diagnosed MDD who had partial or complete response to ECT after receiving treatment at a single center. Approximately two-thirds of the patients were aged 50 years and older, and 22 met criteria for BPD. The ECT consisted of three sessions per week; the total number of sessions ranged from 6 to 18.

The primary outcome was relapse at 6 months after ECT treatment. Relapse was defined as a score of 16 or higher on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in combination with a mean absolute increase of at least 10 points from the psychiatric interview at the end of the ECT.

Relapse rates at 6 months were 37.6% for the study population overall, but significantly higher for those with BPD, compared with those without BPD (72.7% vs. 28.7%; P < .001).

In a multivariate analysis, adjusting for age, gender, and mood stabilizer use after ECT, relapse was approximately four times more likely among individuals with BPD, compared with those without (hazard ratio, 4.14). No significant association appeared between increased relapse and other comorbid personality disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol or substance use disorders, or hospitalization during the ECT treatment period.

Potential reasons for the increased relapse risk among individuals with MDD and BPD include the younger age of the individuals with BPD, which has been shown to increase MDD relapse risk; the direct negative impact of BPD on mental functioning; and the documented tendency to poor treatment adherence, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“Given these different elements, it seems important to screen more systematically for BPD in major depressed individuals treated with ECT in order to allow the implementation of more effective prevention strategies for relapse within 6 months in this particular subpopulation,” they emphasized.

“The demonstration of this higher risk of relapse within 6 months associated with BPD in major depressed individuals treated with ECT could open new therapeutic perspectives to allow better maintenance of euthymia in this particular subpopulation,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the focus on only BPD, which may not generalize to other personality disorders, the researchers noted.

However, the results support data from previous studies and highlight the need for more systematic BPD screening in MDD patients to prevent relapse after ECT, they said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

ECT has demonstrated effectiveness for treatment of unipolar and bipolar major depression, but relapses within 6 months are frequent, and potential factors affecting relapse have not been well studied, wrote Matthieu Hein, MD, PhD, of Erasme Hospital, Université Libre de Bruxelles, and colleagues.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a common comorbidity among individuals with major depressive disorder, and previous research suggests a possible negative effect of BPD on ECT response in MDD patients, they wrote.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the researchers recruited 68 females and 41 males aged 18 years and older with diagnosed MDD who had partial or complete response to ECT after receiving treatment at a single center. Approximately two-thirds of the patients were aged 50 years and older, and 22 met criteria for BPD. The ECT consisted of three sessions per week; the total number of sessions ranged from 6 to 18.

The primary outcome was relapse at 6 months after ECT treatment. Relapse was defined as a score of 16 or higher on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale in combination with a mean absolute increase of at least 10 points from the psychiatric interview at the end of the ECT.

Relapse rates at 6 months were 37.6% for the study population overall, but significantly higher for those with BPD, compared with those without BPD (72.7% vs. 28.7%; P < .001).

In a multivariate analysis, adjusting for age, gender, and mood stabilizer use after ECT, relapse was approximately four times more likely among individuals with BPD, compared with those without (hazard ratio, 4.14). No significant association appeared between increased relapse and other comorbid personality disorders, anxiety disorders, alcohol or substance use disorders, or hospitalization during the ECT treatment period.

Potential reasons for the increased relapse risk among individuals with MDD and BPD include the younger age of the individuals with BPD, which has been shown to increase MDD relapse risk; the direct negative impact of BPD on mental functioning; and the documented tendency to poor treatment adherence, the researchers wrote in their discussion.

“Given these different elements, it seems important to screen more systematically for BPD in major depressed individuals treated with ECT in order to allow the implementation of more effective prevention strategies for relapse within 6 months in this particular subpopulation,” they emphasized.

“The demonstration of this higher risk of relapse within 6 months associated with BPD in major depressed individuals treated with ECT could open new therapeutic perspectives to allow better maintenance of euthymia in this particular subpopulation,” they added.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the retrospective design and the focus on only BPD, which may not generalize to other personality disorders, the researchers noted.

However, the results support data from previous studies and highlight the need for more systematic BPD screening in MDD patients to prevent relapse after ECT, they said.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

From neuroplasticity to psychoplasticity: Psilocybin may reverse personality disorders and political fanaticism

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

One of psychiatry’s long-standing dogmas is that personality disorders are enduring, unchangeable, and not amenable to treatment with potent psychotropics or intensive psychotherapy. I propose that this dogma may soon be shattered.

Several other dogmas in psychiatry have been demolished over the past several decades:

- that “insanity” is completely irreversible and requires lifetime institutionalization. The serendipitous discovery of chlorpromazine1 annihilated this centuries-old dogma

- that chronic, severe, refractory depression (with ongoing suicidal urges) that fails to improve with pharmacotherapy or electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is hopeless and untreatable, until ketamine not only pulverized this dogma, but did it with lightning speed, dazzling us all2

- that dissociative agents such as ketamine are dangerous and condemnable drugs of abuse, until the therapeutic effect of ketamine slayed that dragon3

- that ECT “fries” the brain (as malevolently propagated by antipsychiatry cults), which was completely disproven by neuroimaging studies that show the hippocampus (which shrinks during depression) actually grows by >10% after a few ECT sessions4

- that psychotherapy is not a “real” treatment because talking cannot reverse a psychiatric brain disorder, until studies showed significant neuroplasticity with psychotherapy and decrease in inflammatory biomarkers with cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)5

- that persons with refractory hallucinations and delusions are doomed to a life of disability, until clozapine torpedoed that pessimistic dogma6

- that hallucinogens/psychedelics are dangerous and should be banned, until a jarring paradigm shift occurred with the discovery of psilocybin’s transformative effects, and the remarkable therapeutic effects of its mystical trips.7

Psilocybin’s therapeutic effects

Psilocybin has already proved to have a strong and lasting effect on depression and promises to have therapeutic benefits for patients with substance use disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and anxiety.8 In addition, when the multiple psychological and neurobiological effects of psilocybin (and of other psychedelics) are examined, I see a very promising path to amelioration of severe personality disorders such as psychopathy, antisocial behavior, and narcissism. The mechanism(s) of action of psilocybin on the human brain are drastically different from any man-made psychotropic agent. As a psychiatric neuroscientist, I envision the neurologic impact of psilocybin to be conducive to a complete transformation of a patient’s view of themself, other people, and the meaning of life. It is reminiscent of religious conversion.

The psychological effects of psilocybin in humans have been described as follows:

- emotional breakthrough9

- increased psychological flexibility,10,11 a very cortical effect

- mystical experience,12 which results in sudden and significant changes in behavior and perception and includes the following dimensions: sacredness, noetic quality, deeply felt positive mood, ineffability, paradoxicality, and transcendence of time and space13

- oceanic boundlessness, feeling “one with the universe”14

- universal interconnectedness, insightfulness, blissful state, spiritual experience14

- ego dissolution,15 with loss of one’s personal identity

- increased neuroplasticity16

- changes in cognition and increase in insight.17

The neurobiological effects of psilocybin are mediated by serotonin 5HT2A agonism and include the following18:

- reduction in the activity of the medial prefrontal cortex, which regulates memory, attention, inhibitory control, and habit

- a decrease in the connectivity between the medial prefrontal cortex and the posterior cingulate cortex, which regulates memory and emotions

- reducing the default mode network, which is active during rest, stimulating internal thoughts and reminiscing about previous feelings and events, sometimes including ruminations. Psilocybin reverses those processes to thinking about others, not just the self, and becoming more open-minded about the world and other people. This can be therapeutic for depression, which is often associated with negative ruminations but also with entrenched habits (addictive behaviors), anxiety, PTSD, and obsessive-compulsive disorders

- increased global functional connectivity among various brain networks, leading to stronger functional integration of behavior

- collapse of major cortical oscillatory rhythms such as alpha and others that perpetuate “prior” beliefs

- extensive neuroplasticity and recalibration of thought processes and decomposition of pathological beliefs, referred to as REBUS (relaxed beliefs under psychedelics).

The bottom line is psilocybin and other psychedelics can dramatically alter, reshape, and relax rigid beliefs and personality traits by decreasing “neuroticism” and increasing “extraversion,” insightfulness, openness, and possibly conscientiousness.19 Although no studies of psychedelics in psychopathic, antisocial, or narcissistic personality disorders have been conducted, it is very reasonable to speculate that psilocybin may reverse traits of these disorders such as callousness, lack of empathy, and pathological self-centeredness.

Going further, a preliminary report suggests psilocybin can modify political views by decreasing authoritarianism and increasing libertarianism.20,21 In the current political zeitgeist, could psychedelics such as psilocybin reduce or even eliminate political extremism and visceral hatred on all sides? It would be remarkable research to carry out to heal a politically divided populace.The dogma of untreatable personality disorders or hopelessly entrenched political extremism is on the chopping block, and psychedelics offer hope to splinter those beliefs by concurrently remodeling brain tissue (neuroplasticity) and rectifying the mindset (psychoplasticity).

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

1. Delay J, Deniker P. Neuroleptic effects of chlorpromazine in therapeutics of neuropsychiatry. J Clin Exp Psychopathol. 1955;16(2):104-112.

2. Walsh Z, Mollaahmetoglu OM, Rootman, J, et al. Ketamine for the treatment of mental health and substance use disorders: comprehensive systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;8(1):e19. doi:10.1192/bjo.2021.1061

3. Lener MS, Kadriu B, Zarate CA Jr. Ketamine and beyond: investigations into the potential of glutamatergic agents to treat depression. Drugs. 2017;77(4):381-401.

4. Ayers B, Leaver A, Woods RP, et al. Structural plasticity of the hippocampus and amygdala induced by electroconvulsive therapy in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;79(4):282-292.

5. Cao B, Li R, Ding L, Xu J, et al. Does cognitive behaviour therapy affect peripheral inflammation of depression? A protocol for the systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(12):e048162. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-048162

6. Wagner E, Siafis S, Fernando P, et al. Efficacy and safety of clozapine in psychotic disorders—a systematic quantitative meta-review. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11(1):487.

7. Daws RE, Timmermann C, Giribaldi B, et al. Increased global integration in the brain after psilocybin therapy for depression. Nat Med. 2022;28(4):844-851.

8. Pearson C, Siegel J, Gold JA. Psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for depression: emerging research on a psychedelic compound with a rich history. J Neurol Sci. 2022;434:120096. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2021.120096

9. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, et al. Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the Emotional Breakthrough Inventory. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33(9):1076-1087.

10. Davis AK, Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. J Contextual Behav Sci. 2020;15:39-45.

11. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1-25.

12. Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165-1180.

13. Stace WT. Mysticism and Philosophy. Macmillan Pub Ltd; 1960:37.

14. Barrett FS, Griffiths RR. Classic hallucinogens and mystical experiences: phenomenology and neural correlates. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2018;36:393-430.

15. Nour MM, Evans L, Nutt D, et al. Ego-dissolution and psychedelics: validation of the Ego-Dissolution Inventory (EDI). Front Hum Neurosci. 2016;10:269. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2016.00269

16. Olson DE. The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2020;4(2):563-567.

17. Carhart-Harris RL, Bolstridge M, Day CMJ, et al. Psilocybin with psychological support for treatment-resistant depression: six-month follow-up. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(2):399-408.

18. Carhart-Harris RL. How do psychedelics work? Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2019;32(1):16-21.

19. Erritzoe D, Roseman L, Nour MM, et al. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2018;138(5):368-378.

20. Lyons T, Carhart-Harris RL. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):811-819.

21. Nour MM, Evans L, Carhart-Harris RL. Psychedelics, personality and political perspectives. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2017;49(3):182-191.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale succeeds as transdiagnostic measure

“Current DSM and ICD diagnoses do not depict psychopathology accurately, therefore their validity in research and utility in clinical practice is questioned,” wrote Andreas B. Hofmann, PhD, of the University of Zürich and colleagues.

The BPRS was developed to assess changes in psychopathology across a range of severe psychiatric disorders, but its potential to assess symptoms in nonpsychotic disorders has not been explored, the researchers said.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the investigators analyzed data from 600 adult psychiatric inpatients divided equally into six diagnostic categories: alcohol use disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. The mean age of the patients was 41.5 years and 45.5% were women. The demographic characteristics were similar across most groups, although patients with a personality disorder were significantly more likely than other patients to be younger and female.

Patients were assessed using the BPRS based on their main diagnosis. The mini-ICF-APP, another validated measure for assessing psychiatric disorders, served as a comparator, and both were compared to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI).

Overall, the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP showed moderate correlation and good agreement, the researchers said. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP scales was 0.53 and the concordance correlation coefficient was 0.52. The mean sum scores for the BPRS, the mini-ICF-APP, and the CGI were 45.4 (standard deviation, 14.4), 19.93 (SD, 8.21), and 5.55 (SD, 0.84), respectively, which indicated “markedly ill” to “severely ill” patients, the researchers said.

The researchers were able to detect three clusters of symptoms corresponding to externalizing, internalizing, and thought disturbance domains using the BPRS, and four clusters using the mini-ICF-APP.

The symptoms using BPRS and the functionality domains using the mini-ICF-APP “showed a close interplay,” the researchers noted.

“The symptoms and functional domains we found to be central within the network structure are among the first targets of any psychiatric or psychotherapeutic intervention, namely the building of a common language and understanding as well as the establishment of confidence in relationships and a trustworthy therapeutic alliance,” they wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the collection of data from routine practice rather than clinical trials, the focus on only the main diagnosis without comorbidities, and the inclusion only of patients requiring hospitalization, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and demonstrate the validity of the BPRS as a measurement tool across a range of psychiatric diagnoses, they said.

“Since the BPRS is a widely known and readily available psychometric scale, our results support its use as a transdiagnostic measurement instrument of psychopathology,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Current DSM and ICD diagnoses do not depict psychopathology accurately, therefore their validity in research and utility in clinical practice is questioned,” wrote Andreas B. Hofmann, PhD, of the University of Zürich and colleagues.

The BPRS was developed to assess changes in psychopathology across a range of severe psychiatric disorders, but its potential to assess symptoms in nonpsychotic disorders has not been explored, the researchers said.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the investigators analyzed data from 600 adult psychiatric inpatients divided equally into six diagnostic categories: alcohol use disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. The mean age of the patients was 41.5 years and 45.5% were women. The demographic characteristics were similar across most groups, although patients with a personality disorder were significantly more likely than other patients to be younger and female.

Patients were assessed using the BPRS based on their main diagnosis. The mini-ICF-APP, another validated measure for assessing psychiatric disorders, served as a comparator, and both were compared to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI).

Overall, the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP showed moderate correlation and good agreement, the researchers said. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP scales was 0.53 and the concordance correlation coefficient was 0.52. The mean sum scores for the BPRS, the mini-ICF-APP, and the CGI were 45.4 (standard deviation, 14.4), 19.93 (SD, 8.21), and 5.55 (SD, 0.84), respectively, which indicated “markedly ill” to “severely ill” patients, the researchers said.

The researchers were able to detect three clusters of symptoms corresponding to externalizing, internalizing, and thought disturbance domains using the BPRS, and four clusters using the mini-ICF-APP.

The symptoms using BPRS and the functionality domains using the mini-ICF-APP “showed a close interplay,” the researchers noted.

“The symptoms and functional domains we found to be central within the network structure are among the first targets of any psychiatric or psychotherapeutic intervention, namely the building of a common language and understanding as well as the establishment of confidence in relationships and a trustworthy therapeutic alliance,” they wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the collection of data from routine practice rather than clinical trials, the focus on only the main diagnosis without comorbidities, and the inclusion only of patients requiring hospitalization, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and demonstrate the validity of the BPRS as a measurement tool across a range of psychiatric diagnoses, they said.

“Since the BPRS is a widely known and readily available psychometric scale, our results support its use as a transdiagnostic measurement instrument of psychopathology,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

“Current DSM and ICD diagnoses do not depict psychopathology accurately, therefore their validity in research and utility in clinical practice is questioned,” wrote Andreas B. Hofmann, PhD, of the University of Zürich and colleagues.

The BPRS was developed to assess changes in psychopathology across a range of severe psychiatric disorders, but its potential to assess symptoms in nonpsychotic disorders has not been explored, the researchers said.

In a study published in Psychiatry Research, the investigators analyzed data from 600 adult psychiatric inpatients divided equally into six diagnostic categories: alcohol use disorder, major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, and personality disorders. The mean age of the patients was 41.5 years and 45.5% were women. The demographic characteristics were similar across most groups, although patients with a personality disorder were significantly more likely than other patients to be younger and female.

Patients were assessed using the BPRS based on their main diagnosis. The mini-ICF-APP, another validated measure for assessing psychiatric disorders, served as a comparator, and both were compared to the Clinical Global Impression Scale (CGI).

Overall, the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP showed moderate correlation and good agreement, the researchers said. The Pearson correlation coefficient for the BPRS and mini-ICF-APP scales was 0.53 and the concordance correlation coefficient was 0.52. The mean sum scores for the BPRS, the mini-ICF-APP, and the CGI were 45.4 (standard deviation, 14.4), 19.93 (SD, 8.21), and 5.55 (SD, 0.84), respectively, which indicated “markedly ill” to “severely ill” patients, the researchers said.

The researchers were able to detect three clusters of symptoms corresponding to externalizing, internalizing, and thought disturbance domains using the BPRS, and four clusters using the mini-ICF-APP.

The symptoms using BPRS and the functionality domains using the mini-ICF-APP “showed a close interplay,” the researchers noted.

“The symptoms and functional domains we found to be central within the network structure are among the first targets of any psychiatric or psychotherapeutic intervention, namely the building of a common language and understanding as well as the establishment of confidence in relationships and a trustworthy therapeutic alliance,” they wrote in their discussion.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the collection of data from routine practice rather than clinical trials, the focus on only the main diagnosis without comorbidities, and the inclusion only of patients requiring hospitalization, the researchers noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size, and demonstrate the validity of the BPRS as a measurement tool across a range of psychiatric diagnoses, they said.

“Since the BPRS is a widely known and readily available psychometric scale, our results support its use as a transdiagnostic measurement instrument of psychopathology,” they concluded.

The study received no outside funding. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM PSYCHIATRY RESEARCH

New panic disorder model flags risk for recurrence, persistence

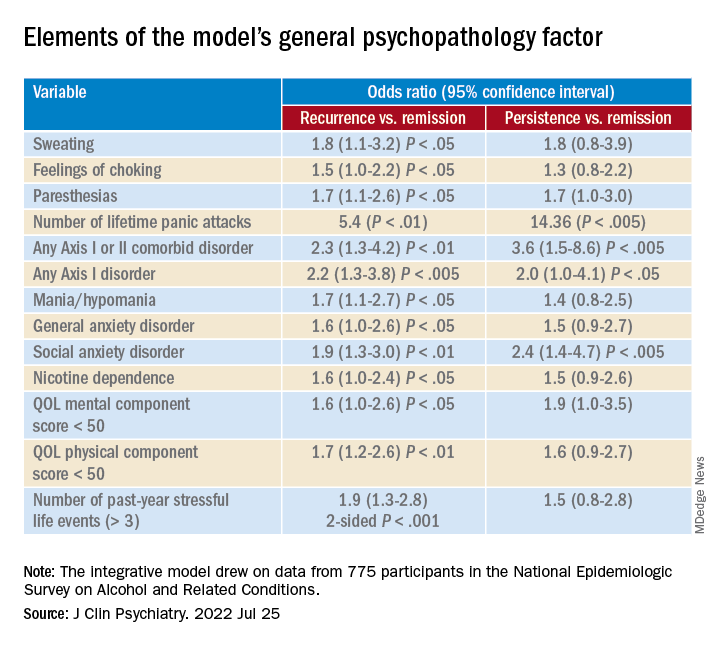

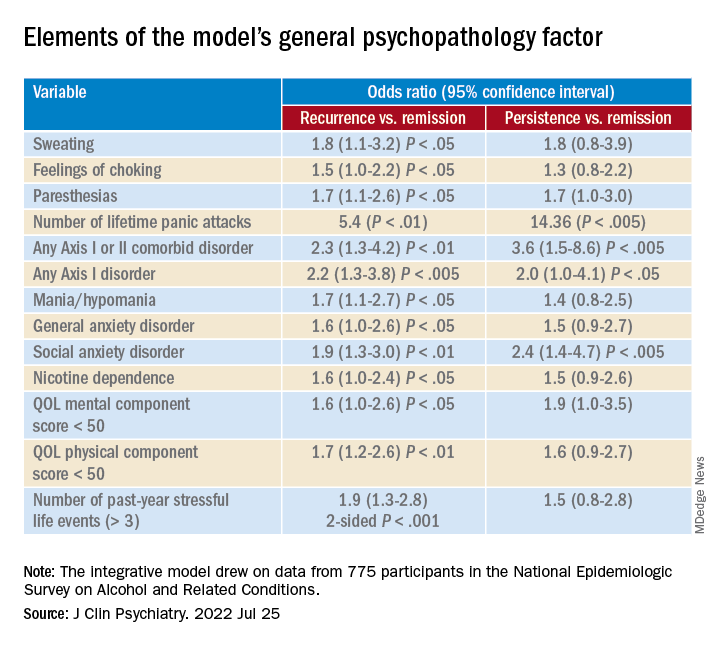

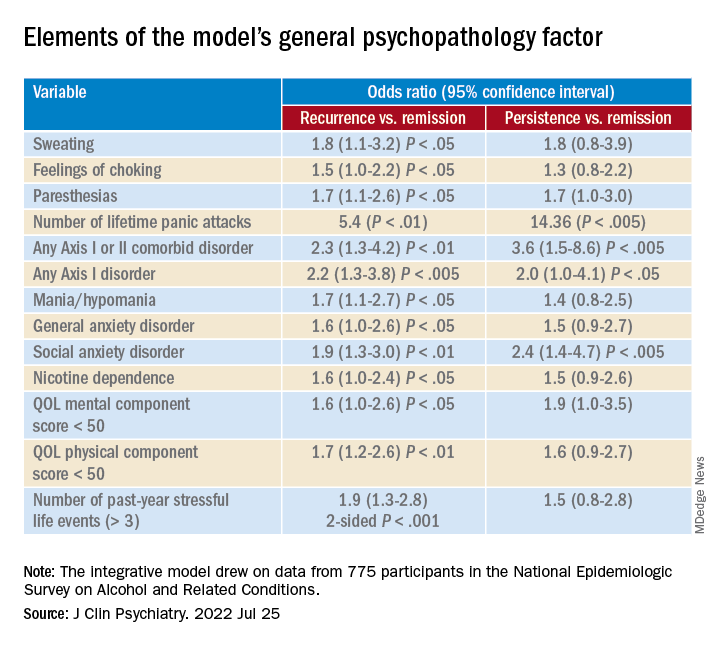

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.

One study limitation cited was that several psychiatric disorders known to be associated with PD recurrence or persistence, such as borderline personality disorder, were not examined. Additionally, the study used a 3-year follow-up period – and the results might have differed for other follow-up time frames, the researchers noted.

Nevertheless, the findings constitute a “comprehensive model” to predict recurrence and persistence of PD, they wrote. Moreover, early treatment-seeking behavior “should be promoted, as it may reduce the risk of recurrence.”

Not much new?

Commenting on the study, Peter Roy-Byrne, MD, professor of psychiatry, University of Washington, Seattle, noted, “there is not much that is new here.”

Dr. Roy-Byrne, who was not involved with the study, said that a “general theme for years has been that more severe illness, whether you measure it by greater number of other Axis I disorders or symptom severity or a general psychopathology factor, usually predicts worse outcome – here codified as persistence and recurrence.”

Greater stress and reluctance to seek treatment may also predict worse outcomes, he noted.

In addition, the study “did not examine another very important factor: the degree of social connection/social support that someone has,” Dr. Roy-Byrne said. However, “perhaps some of this was contained in specific life events.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators based in France and the United States analyzed data for almost 800 patients with DSM-IV–diagnosed PD.

Results showed that having a “general psychopathology factor,” defined as the shared effects of all comorbid conditions, or PD liability, significantly and independently predicted 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD symptoms.

Having a lower physical health-related quality of life (QOL), a greater number of stressful life events, and not seeking treatment at baseline were also significant and independent predictors.

“This integrative model could help clinicians to identify individuals at high risk of recurrence or persistence of panic disorder and provide content for future research,” Valentin Scheer, MD, MPH, a resident in psychiatry at AP-HP, Assistance Publique, Hôpitaux de Paris, and colleagues wrote.

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

Integration needed

PD is a disabling disorder with a “chronic course” – and a recurrence rate ranging from 25% to 50%, the investigators noted.

“Because of the heterogeneous course of PD, there is a need to develop a comprehensive predictive model of recurrence or persistence,” they wrote. This could “help practitioners adapt therapeutic strategies and develop prevention strategies in high-risk individuals.”

Most previous studies that have investigated risk factors for PD recurrence and persistence have relied on clinical samples, often with limited sample sizes.

Moreover, each risk factor, when considered individually, accounts for only a “small proportion” of the variance in risk, the researchers noted. The co-occurrence of these risk factors “suggests the need to combine them into a broad multivariable model.”

However, currently proposed integrative models do not identify independent predictors or mitigate the influence of confounding variables. To fill this gap, the investigators conducted a study using structural equation modeling “to take into account multiple correlations across predictors.”

They drew on data from 775 participants (mean age, 40 years) in the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). For the current analysis, they examined two waves of NESARC (2001-2002 and 2004-2005) to “build a comprehensive model” of the 3-year recurrence or persistence of PD.

The researchers used a “latent variable approach” that simultaneously examined the effect of the following five groups of potential predictors of recurrence or persistence: PD severity, severity of comorbidity, family history of psychiatric disorders, sociodemographic characteristics, and treatment-seeking behavior.

They also distinguished between risk factors responsible for recurrence and those responsible for persistence.

Psychiatric diagnoses were determined on the basis of the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule-IV. Participants also completed Version 2 of the Short Form 12-Item Health Survey, which assesses both mental and physical QOL over the previous 4 weeks.

Early treatment needed

Among participants with a 12-month diagnosis of PD at wave 1, 13% had persistent PD and 27.6% had recurrent PD during the 3-year period. The mean duration of illness was 9.5 years.

A greater number of lifetime panic attacks, the presence of any Axis I or II comorbid disorder, and any Axis I disorder, especially social anxiety disorder, were significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence and for persistence.

Sweating, choking, paresthesias, the comorbid disorders of mania/hypomania and general anxiety disorder, nicotine dependence, lower mental and physical QOL scores, and exposure to a greater number of stressful life events in the previous year were all significantly associated with 3-year risk for recurrence.

Only variables shown with a P value were statistically significant, “with the a priori fixed at .05,” the researchers noted.

A combination of psychopathology factors, such as the shared effect of all comorbid psychiatric conditions, PD liability, lower physical health-related QOL, more life stressors during the past year, and not seeking treatment at baseline “significantly and independently” predicted recurrence or persistence of symptoms between the two waves (all Ps < .05), the investigators reported.