User login

The Numerators: Treating Noncompliant, Medically Complicated Hospital Patients

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

We hospitalists are scientifically minded. We understand basic statistics, including percentages, percentiles, numerators, denominators (see Figure 1, right). In healthcare, we see a lot of patients we call denominators; these denominators are generally the types of patients to whom not much happens. They come in “pre-” and they leave “post-.” They generally pass through our walls, and our lives, according to plan, without leaving an impenetrable memory of who they were or what they experienced.

The numerators, on the other hand, do have something happen to them—something unexpected, untoward, unanticipated, unlikely. Sometimes we describe numerators as “noncompliant” or “medically complicated” or “refractory to treatment.” We often find ways to rationalize and explain how the patient turned from a denominator into a numerator—something they did, or didn’t do, to nudge them above the line. They smoked, they ate too much, they didn’t take their medications “as prescribed.” Often there is a less robust discussion about what we could have done to reduce the nudge: understand their background, their literacy, their finances, their physical/cognitive limitations, their understanding of risks and benefits.

I read a powerful piece about “numerators” written by Kerry O’Connell. In this piece, she describes what it was like to cross over the line into being a numerator after acquiring a hospital-acquired infection:

Five years ago this summer while under deep anesthesia for arm surgery number 3, I drifted above the line and joined the group called Numerators. … Numerators have lost a lot to join this group; many have lost organs, and some have lost all their limbs, all have many kinds of scars from their journey. It was not our choice to leave the world of Denominators … and many will struggle the rest of their lives to understand why...

There are lots of silly rules for not counting some infected souls, as if by not counting us we might not exist. Numerators that are identified are then divided by the Denominators to create a nameless, faceless, mysteriously small number called infection rates. “Rates,” like their cousin “odds,” claim to portray hope while predicting doom for some of us. Denominators are in love with rates, for no matter how many Numerators they have sired, someone else has sired more. Rates soothe the Denominator conscious and allow them to sleep peacefully at night ...

Numerators don’t ask for much from the world. We ask that Denominators look behind the numbers to see the people, to love us, count us, respect our suffering, and help keep us out of bankruptcy, for once we were Denominators just like you. Our greatest dream is that you find the daily strength to truly care. To care enough to follow the checklists, to care enough to wash your hands, to care enough to only use virgin needles, for the saddest day for all Numerators is when another unsuspecting Denominator rises above the line to join our group.1

CB’s Story

Now think of all the numerators you have met. I am going to repeat that phrase. Think of all the numerators you have met. I have met quite a few. Now I am going to tell you about my most memorable numerator.

CB was a 36-year-old white female admitted to the hospital with a recent diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. She had a protracted hospital course on various immunosuppressant drugs, none of which relieved her symptoms. During her hospital stay, her family, including her 2-year-old twins, visited every single day. After several weeks with no improvement, the decision was made to proceed to a colectomy. The surgical procedure itself was uncomplicated, a true denominator.

Then, on post-op Day 5, the day of her anticipated discharge, a pulmonary embolus thrust her into the numerator position. A preventable, eventually fatal numerator—a numerator who “just would not keep her compression devices on” and whom the staff tried to get out of bed, “but she just wouldn’t do it.” A numerator who just so happened to be my sister.

Every year on April 2, when I call my niece and nephew to wish them a happy birthday, I think about numerators. And I think about how incredibly different life would be for those 10-year-old twins, had their mom just stayed a denominator. And every day, when I sit in conference rooms and hear from countless people about how difficult it is to prevent this and reduce that, and how zero is not feasible, I think about numerators. I don’t look at their bar chart, or their run chart, or their red line, or their blue line, or whether their line is within the control limits, or what their P-value is. I think about who represents that black dot, and about how we are going to actually convince ourselves to “First, do no harm.”

When I find myself amongst a crowd quibbling about finances, lunch breaks, workflows, accountability, and about who is going to check the box or fill out the form, I think about the numerators, and how we are truly wasting their time, their livelihood, and their ability to stay below the line.

And someday, when my niece and nephew are old enough to understand, I will try to help them tolerate and accept the fact that “preventable” and “prevented” are not interchangeable. At least not in the medical industry. At least not yet.

In memory of Colleen Conlin Bowen, May 14, 2004

Dr. Scheurer is a hospitalist and chief quality officer at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston. She is physician editor of The Hospitalist. Email her at scheured@musc.edu.

Reference

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing Off-Label Drugs

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Consider Patient Safety, Outcomes Risk before Prescribing “Off-Label”

What is the story with off-label drug use? I have seen some other physicians in my group use dabigatran for VTE prophylaxis, which I know it is not an approved indication. Am I taking on risk by continuing this treatment?

—Fabian Harris, Tuscaloosa, Ala.

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Our friends at the FDA are in the business of approving drugs for use, but they do not regulate medical practice. So the short answer to your question is that off-label drug use is perfectly acceptable. Once a drug has been approved for use, if, in your clinical judgment, there are other indications for which it could be beneficial, then you are well within your rights to prescribe it. The FDA does not dictate how you practice medicine.

However, you will still be held to the community standard when it comes to your medical practice. As an example, gabapentin is used all the time for neuropathic pain syndromes, though technically it is only approved for seizures and post-herpetic neuralgia. Although the FDA won’t restrict your prescribing, it does prohibit pharmaceutical companies from marketing their drugs for anything other than their approved indications. In fact, Pfizer settled a case in 2004 on this very drug due to the promotion of prescribing it for nonapproved indications. I think at this point it’s fairly well accepted that lots of physicians use gabapentin for neuropathic pain, so you would not be too far out on a limb in prescribing it yourself in this manner.

For newer drugs, I might proceed with a little more caution. Anyone out there remember trovofloxacin (Trovan)? It was a new antibiotic approved in the late 1990s, with a coverage spectrum similar to levofloxacin, but with even more weight toward the gram positives. A wonder drug! Oral! As a result, it got prescribed like water, but not for the serious infections it was designed for: It got prescribed “off label” for common URIs and sinusitis. Unfortunately, it also caused a fair amount of liver failure and was summarily pulled from the market.

Does this mean dabigatran is a bad drug? No, but we don’t have much history with it, either. So while it might seem to be an innocuous extension to prescribe it for VTE prevention when it has already been approved for stroke prevention in afib, I think you carry some risk by doing this. In addition, some insurers will not cover a drug being prescribed in this manner, so you might be exposing your patient to added costs as well. Additionally, there’s nothing about off-label prescribing that says you have to tell the patient that’s what you’re doing. However, if you put together the factors of not informing a patient about an off-label use, and a patient having to pay out of pocket for that medicine, with an adverse outcome ... well, let’s just say that might not end too well.

Ultimately, I think you will need to consider the safety profile of the drug, the risk for an adverse outcome, your own risk tolerance, and the current state of medical practice before you consistently agree to use a drug “off label.” Given the slow-moving jungle of FDA approval, I can understand the desire to use a newer drug in an off-label manner, but it’s probably best to stop and think about the alternatives before proceeding. If you’re practicing in a group, then it’s just as important to come to a consensus with your partners about which drugs you will comfortably use off-label and which ones you won’t, especially as newer drugs come into the marketplace.

Win Whitcomb: Hospitalists Must Grin and Bear the Hospital-Acquired Conditions Program

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

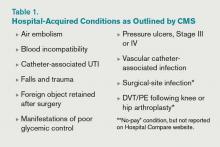

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

The Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule charts a different future: By fiscal-year 2015 (October 2014), it will morph into a set of measures that are vetted by the National Quality Forum. Hopefully, this will be an improvement.

In recent years, hospitalists have been deluged with rules about documentation, being asked to use medical vocabulary in ways that were foreign to many of us during our training years. Much of the focus on documentation has been propelled by hospitals’ quest to optimize (“maximize” is a forbidden term) reimbursement, which is purely a function of what is written by “licensed providers” (doctors, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners) in the medical chart.

But another powerful driver of documentation practices of late is the hospital-acquired conditions (HAC) program developed by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and enacted in 2009.

Origins of the HAC List

CMS disliked the fact that they were paying for conditions acquired in the hospital that were “reasonably preventable” if evidence-based—or at least “best”—practice was applied. After all, who likes to pay for a punctured gas tank when you brought the minivan in for an oil change? CMS worked with stakeholder groups, including SHM, to create a list of conditions known as hospital-acquired conditions (see Table 1, right).

(As an aside, SHM was supportive of CMS. In fact, we provided direct input into the final rule, recognizing some of the drawbacks of the CMS approach but understanding the larger objective of reengineering a flawed incentive system.)

The idea was that if a hospital submitted a bill to CMS that contained one of these conditions, the hospital would not be paid the amount by which that condition increased total reimbursement for that hospitalization. Note that if you’ve been told your hospital isn’t getting paid at all for patients with one of these conditions, that is not quite correct. Instead, your hospital may not get paid the added amount that is derived from having one of the diagnoses on the list submitted in your hospital’s bill to CMS for a given patient. At the end of the day, this might be a few hundred dollars each time one of these is documented—or $0, if your hospital biller can add another diagnosis in its place to capture the higher payment.

How big a hit to a hospital’s bottom line is this? Meddings and colleagues recently reported that a measly 0.003% of all hospitalizations in Michigan in 2009 saw payments lowered as a result of hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI, one of the list’s HACs (Ann Int Med. 2012;157:305-312). When all the HACs are added together, one can extrapolate that they haven’t exactly had a big impact on hospital payments.

If the specter of nonpayment for one of these is not enough of a motivator (and it shouldn’t be, given the paltry financial stakes), the rate of HACs are now reported for all hospitals on the Hospital Compare website (www.hospitalcompare.hhs.gov). If a small poke to the pocketbook doesn’t work, maybe public humiliation will.

The Problem with HACs

Although CMS’ intent in creating the HAC program—to eliminate payment for “reasonably preventable” hospital-acquired conditions, thereby improving patient safety—was good, in practice, the program has turned out to be as much about documentation as it is about providing good care. For example, if I forget to write that a Stage III pressure ulcer was present on admission, it gets coded as hospital-acquired and my hospital gets dinged.

It’s important to note that HACs as quality measures were never endorsed by the National Quality Forum (NQF), and without such an endorsement, a quality measure suffers from Rodney Dangerfield syndrome: It don’t get no respect.

Finally, it is disquieting that Meddings et al showed that hospital-acquired catheter-associated UTI rates derived from chart documentation for HACs were but a small fraction of rates determined from rigorous epidemiologic studies, demonstrating that using claims data for determining rates for that specific HAC is flawed. We can only wonder how divergent reported vs. actual rates for the other HACs are.

The Future of the HAC Program

The Affordable Care Act specifies that the lowest-performing quartile of U.S. hospitals for HAC rates will see a 1% Medicare reimbursement reduction beginning in fiscal-year 2015. That’s right: Hospitals facing possible readmissions penalties and losses under value-based purchasing also will face a HAC penalty.

Thankfully, the recently released Inpatient Prospective Payment System FY2013 Final Rule, CMS’ annual update of how hospitals are paid, specifies that the HAC measures are to be removed from public reporting on the Hospital Compare website effective Oct. 1, 2014. They will be replaced by a new set of measures that will (hopefully) be more methodologically sound, because they will require the scrutiny required for endorsement by the NQF. Exactly how these measures will look is not certain, as the rule-making has not yet occurred.

We do know that the three infection measures—catheter-associated UTI, surgical-site infection, and vascular catheter infection—will be generated from clinical data and, therefore, more methodologically sound under the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network. The derivation of the other measures will have to wait until the rule is written next year.

So, until further notice, pay attention to the queries of your hospital’s documentation experts when they approach you about a potential HAC!

Dr. Whitcomb is medical director of healthcare quality at Baystate Medical Center in Springfield, Mass. He is a co-founder and past president of SHM. Email him at wfwhit@comcast.net.

Guidelines Help Slash CLABSI Rate by 40% in the ICU

The largest effort to date to tackle central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) has reduced infection rates in ICUs nationwide by 40%, according to preliminary findings from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

AHRQ attributes the decrease to a CLABSI safety checklist from the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) that encourages hospital staff to wash their hands prior to inserting central lines, avoid the femoral site, remove lines when they are no longer needed, and use the antimicrobial agent chlorhexidine to clean the patient's insertion site.

The checklist was developed by Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and originally implemented in ICUs statewide in Michigan as the Keystone Project. Since 2009, CUSP has recruited more than 1,000 participating hospitals in 44 states. CUSP collectively reported a decrease to 1.25 from 1.87 CLABSIs per 1,000 central-line days 10-12 months after implementing the program, according to AHRQ [PDF].

The real game-changer for CLABSIs has been the widespread adoption of chlorhexidine as an insertion site disinfectant, says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, director of the Veterans Administration at the University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program in Ann Arbor and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Dr. Saint is on the national leadership team of On the CUSP: Stop CAUTI (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections), an initiative that aims to reduce mean rates of CAUTI infections by 25% in hospitals nationwide.

Although hospitalists don't routinely place central lines, their role in this procedure is growing, both in nonacademic hospitals that lack intensivists and on hospitals' general medicine floors.

"My take-home message for hospitalists: if you are putting in central lines, if you only make one change in practice, is to use chlorhexidine as the site disinfectant," Dr. Saint says.

Visit our website for more information about central-line-associated bloodstream infections.

The largest effort to date to tackle central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) has reduced infection rates in ICUs nationwide by 40%, according to preliminary findings from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

AHRQ attributes the decrease to a CLABSI safety checklist from the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) that encourages hospital staff to wash their hands prior to inserting central lines, avoid the femoral site, remove lines when they are no longer needed, and use the antimicrobial agent chlorhexidine to clean the patient's insertion site.

The checklist was developed by Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and originally implemented in ICUs statewide in Michigan as the Keystone Project. Since 2009, CUSP has recruited more than 1,000 participating hospitals in 44 states. CUSP collectively reported a decrease to 1.25 from 1.87 CLABSIs per 1,000 central-line days 10-12 months after implementing the program, according to AHRQ [PDF].

The real game-changer for CLABSIs has been the widespread adoption of chlorhexidine as an insertion site disinfectant, says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, director of the Veterans Administration at the University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program in Ann Arbor and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Dr. Saint is on the national leadership team of On the CUSP: Stop CAUTI (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections), an initiative that aims to reduce mean rates of CAUTI infections by 25% in hospitals nationwide.

Although hospitalists don't routinely place central lines, their role in this procedure is growing, both in nonacademic hospitals that lack intensivists and on hospitals' general medicine floors.

"My take-home message for hospitalists: if you are putting in central lines, if you only make one change in practice, is to use chlorhexidine as the site disinfectant," Dr. Saint says.

Visit our website for more information about central-line-associated bloodstream infections.

The largest effort to date to tackle central-line-associated bloodstream infections (CLABSIs) has reduced infection rates in ICUs nationwide by 40%, according to preliminary findings from the federal Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

AHRQ attributes the decrease to a CLABSI safety checklist from the Comprehensive Unit-Based Safety Program (CUSP) that encourages hospital staff to wash their hands prior to inserting central lines, avoid the femoral site, remove lines when they are no longer needed, and use the antimicrobial agent chlorhexidine to clean the patient's insertion site.

The checklist was developed by Peter Pronovost, MD, PhD, FCCM, and colleagues at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, and originally implemented in ICUs statewide in Michigan as the Keystone Project. Since 2009, CUSP has recruited more than 1,000 participating hospitals in 44 states. CUSP collectively reported a decrease to 1.25 from 1.87 CLABSIs per 1,000 central-line days 10-12 months after implementing the program, according to AHRQ [PDF].

The real game-changer for CLABSIs has been the widespread adoption of chlorhexidine as an insertion site disinfectant, says Sanjay Saint, MD, MPH, director of the Veterans Administration at the University of Michigan Patient Safety Enhancement Program in Ann Arbor and professor of medicine at the University of Michigan. Dr. Saint is on the national leadership team of On the CUSP: Stop CAUTI (Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections), an initiative that aims to reduce mean rates of CAUTI infections by 25% in hospitals nationwide.

Although hospitalists don't routinely place central lines, their role in this procedure is growing, both in nonacademic hospitals that lack intensivists and on hospitals' general medicine floors.

"My take-home message for hospitalists: if you are putting in central lines, if you only make one change in practice, is to use chlorhexidine as the site disinfectant," Dr. Saint says.

Visit our website for more information about central-line-associated bloodstream infections.

VIDEO: Checklists Improve Outcomes, Require Care-team Buy-in

Hospitalists Can Be Prime Partners in QI, Patient Safety Efforts

NEW YORK—Hospitalists are poised to become key allies with hospital quality and safety officers nationwide, according to veteran hospitalist Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, director of quality and safety education for Penn Medicine in Philadelphia.

Addressing hospitalists at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, Dr. Myers said that while the challenges associated with quality improvement (QI) are many, HM leaders have the in-house relationships and respect to push the issue.

"There's really no other specialty more perfectly poised to lead this work," she told more than 180 symposium attendees Friday.

Dr. Myers, in an address titled "Enhancing Patient Safety," told The Hospitalist that HM leaders pursue three broad goals: to participate in QI programs already in place, to help create or foster a culture focused on addressing mistakes, and to teach those lessons to young physicians.

She urged physicians to actively report on mistakes and near misses, and earnestly address the processes that led to them. If a vehicle to discuss the mistakes doesn't exist at an institution, hospitalists can push to start one, she said. If a hospital doesn't have an electronic incident reporting system, a hospitalist can push to get one. "This is the goal," Dr. Myers added. "People coming to work and feeling they can be safe and report errors in the spirit of improvement."

She noted that many hospitalists already oversee quality and safety programs without any formal training. She recommended some of those physicians consider the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), a three-day academy designed as a faculty development program and sponsored by SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM). The academy is March 7-9, 2013, in Tempe, Ariz.

NEW YORK—Hospitalists are poised to become key allies with hospital quality and safety officers nationwide, according to veteran hospitalist Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, director of quality and safety education for Penn Medicine in Philadelphia.

Addressing hospitalists at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, Dr. Myers said that while the challenges associated with quality improvement (QI) are many, HM leaders have the in-house relationships and respect to push the issue.

"There's really no other specialty more perfectly poised to lead this work," she told more than 180 symposium attendees Friday.

Dr. Myers, in an address titled "Enhancing Patient Safety," told The Hospitalist that HM leaders pursue three broad goals: to participate in QI programs already in place, to help create or foster a culture focused on addressing mistakes, and to teach those lessons to young physicians.

She urged physicians to actively report on mistakes and near misses, and earnestly address the processes that led to them. If a vehicle to discuss the mistakes doesn't exist at an institution, hospitalists can push to start one, she said. If a hospital doesn't have an electronic incident reporting system, a hospitalist can push to get one. "This is the goal," Dr. Myers added. "People coming to work and feeling they can be safe and report errors in the spirit of improvement."

She noted that many hospitalists already oversee quality and safety programs without any formal training. She recommended some of those physicians consider the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), a three-day academy designed as a faculty development program and sponsored by SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM). The academy is March 7-9, 2013, in Tempe, Ariz.

NEW YORK—Hospitalists are poised to become key allies with hospital quality and safety officers nationwide, according to veteran hospitalist Jennifer Myers, MD, FHM, director of quality and safety education for Penn Medicine in Philadelphia.

Addressing hospitalists at the seventh annual Mid-Atlantic Hospital Medicine Symposium at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York, Dr. Myers said that while the challenges associated with quality improvement (QI) are many, HM leaders have the in-house relationships and respect to push the issue.

"There's really no other specialty more perfectly poised to lead this work," she told more than 180 symposium attendees Friday.

Dr. Myers, in an address titled "Enhancing Patient Safety," told The Hospitalist that HM leaders pursue three broad goals: to participate in QI programs already in place, to help create or foster a culture focused on addressing mistakes, and to teach those lessons to young physicians.

She urged physicians to actively report on mistakes and near misses, and earnestly address the processes that led to them. If a vehicle to discuss the mistakes doesn't exist at an institution, hospitalists can push to start one, she said. If a hospital doesn't have an electronic incident reporting system, a hospitalist can push to get one. "This is the goal," Dr. Myers added. "People coming to work and feeling they can be safe and report errors in the spirit of improvement."

She noted that many hospitalists already oversee quality and safety programs without any formal training. She recommended some of those physicians consider the Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA), a three-day academy designed as a faculty development program and sponsored by SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM). The academy is March 7-9, 2013, in Tempe, Ariz.

ONLINE EXCLUSIVE: Daniel Dressler, MD, MSc, SFHM, discusses the differences in opinion over the SHM/SCCM critical care fellowship proposal

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Click here to listen to Dr. Dressler

Study: Neurohospitalists Benefit Academic Medical Centers

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Bringing a neurohospitalist service into an academic medical center can reduce neurological patients' length of stay (LOS) at the facility, according to a study in Neurology.

The retrospective cohort study, "Effect of a Neurohospitalist Service on Outcomes at an Academic Medical Center," found that the mean LOS dropped to 4.6 days while the neurohospitalist service was in place, compared with 6.3 days during the pre-neurohospitalist period. However, adding the service didn't significantly reduce the median cost of care delivery ($6,758 vs. $7,241; P=0.25) or in-hospital mortality rate (1.6% vs. 1.2%; P=0.61), the study noted.

Lead author Vanja Douglas, MD, health sciences assistant clinical professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco (UCSF) School of Medicine, says the study's impact is limited by its single-center universe of data. The study was conducted at a UCSF Medical Center in October 2006, but Dr. Douglas hopes similar studies at other academic or community centers will replicate the findings.

"If the current model people have in place is not necessarily focused on outcomes like LOS and cost, then making a change to a neurohospitalist model is likely to positively affect those outcomes," says Dr. Douglas, editor in chief of The Neurohospitalist.

Investigators tracked administrative data starting 21 months before UCSF added a neurohospitalist service and 27 months after. The service was comprised of one neurohospitalist focused solely on inpatients, which allowed other staff neurologists to focus on consultative cases throughout the hospital. Dr. Douglas says as HM groups look to improve their scope of practice and bottom line, studies such as his can lay the groundwork to make the investment.

"A lot of the groups that contract with hospitals are interested in partnering with subspecialty hospitalists," Dr. Douglas adds. "A neurohospitalist model has the potential to work, and the potential to improve outcomes."

Rules of Engagement Necessary for Comanagement of Orthopedic Patients

One of our providers wants to use adult hospitalists for coverage of inpatient orthopedic surgery patients. Is this acceptable practice? Are there qualifiers?

–Libby Gardner

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Let’s see how far we can tackle this open-ended question. There has been lots of discussion on the topic of comanagement in the past by people eminently more qualified than I am. Still, it never hurts to take a fresh look at things.

For one, on the subject of admissions, I am a firm believer that hospitalists should admit all adult hip fractures. The overwhelming majority of the time, these patients are elderly with comorbid conditions. Sure, they are going to get their hip fixed, because the alternative is usually unacceptable, but some thought needs to go into the process. The orthopedic surgeon sees a hip that needs fixing and not much else. When issues like renal failure, afib, CHF, prior DVT, or dementia are present, hospitalists should take charge of the case. It is the best way to ensure that the patient receives optimal medical care and the documentation that goes along with it. I love our orthopedic surgeons, but I don’t want them primarily admitting, managing, and discharging my elderly patients. Let the surgeon do what they do best, which is operate, and leave the rest to us.

On the subject of orthopedic trauma, I take the exact opposite tack—this is not something for which I or most of my colleagues have expertise. A young, healthy patient with trauma should be admitted by the orthopedic service; that patient population’s complications are much more likely to be directly related to their trauma.

When it comes to elective surgery, when the admitting surgeon (orthopedic or otherwise) wants the help of a hospitalist, then I think it is of paramount importance to have clear “rules of engagement.” I think with good expectations, you can have a fantastic working relationship with your surgeons. Without them, it becomes a nightmare.

Here are my HM group’s rules for elective orthopedic surgery:

- Orthopedics handles all pain medications and VTE prophylaxis, including discharge prescriptions.

- Medicine handles all admit and discharge medication reconciliation (“med rec”).

- There is shared discussion on:

- Need for transfusion; and

- The VTE prophylaxis when a patient already is on chronic anticoagulation.

We do not vary from this protocol. I never adjust a patient’s pain medications. Even the floor nurses know this. Because I’m doing the admit med rec, it also means that the patient doesn’t have their HCTZ continued after 600cc of EBL and spinal anesthesia.

The system works because the rules are clear and the communication is consistent. This does not mean that we cover the orthopedic service at night. They are equally responsible for their patients under the items outlined above. In my view—and this might sound simplistic—the surgeon caused the post-op pain, so they should be responsible for managing it. On VTE prophylaxis, I might take a more nuanced view, but for our surgeons, they own the wound and the post-op follow-up, so they get the choice on what agent to use.

Would I accept an arrangement in which I covered all the orthopedic issues out of regular hours? Nope—not when they have primary responsibility for the case; they should always be directly available to the nurse. I think that anything else would be a system ripe for abuse.

Our exact rules will not work for every situation, but I would strongly encourage the two basic tenets from above: No. 1, the hospitalist should primarily admit and manage elderly hip fractures, and No. 2, clear rules of engagement should be established with your orthopedic or surgery group. It’s a discussion worth having during daylight hours, because trying to figure out the rules at 3 in the morning rarely ends well.

One of our providers wants to use adult hospitalists for coverage of inpatient orthopedic surgery patients. Is this acceptable practice? Are there qualifiers?

–Libby Gardner

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Let’s see how far we can tackle this open-ended question. There has been lots of discussion on the topic of comanagement in the past by people eminently more qualified than I am. Still, it never hurts to take a fresh look at things.

For one, on the subject of admissions, I am a firm believer that hospitalists should admit all adult hip fractures. The overwhelming majority of the time, these patients are elderly with comorbid conditions. Sure, they are going to get their hip fixed, because the alternative is usually unacceptable, but some thought needs to go into the process. The orthopedic surgeon sees a hip that needs fixing and not much else. When issues like renal failure, afib, CHF, prior DVT, or dementia are present, hospitalists should take charge of the case. It is the best way to ensure that the patient receives optimal medical care and the documentation that goes along with it. I love our orthopedic surgeons, but I don’t want them primarily admitting, managing, and discharging my elderly patients. Let the surgeon do what they do best, which is operate, and leave the rest to us.

On the subject of orthopedic trauma, I take the exact opposite tack—this is not something for which I or most of my colleagues have expertise. A young, healthy patient with trauma should be admitted by the orthopedic service; that patient population’s complications are much more likely to be directly related to their trauma.

When it comes to elective surgery, when the admitting surgeon (orthopedic or otherwise) wants the help of a hospitalist, then I think it is of paramount importance to have clear “rules of engagement.” I think with good expectations, you can have a fantastic working relationship with your surgeons. Without them, it becomes a nightmare.

Here are my HM group’s rules for elective orthopedic surgery:

- Orthopedics handles all pain medications and VTE prophylaxis, including discharge prescriptions.

- Medicine handles all admit and discharge medication reconciliation (“med rec”).

- There is shared discussion on:

- Need for transfusion; and

- The VTE prophylaxis when a patient already is on chronic anticoagulation.

We do not vary from this protocol. I never adjust a patient’s pain medications. Even the floor nurses know this. Because I’m doing the admit med rec, it also means that the patient doesn’t have their HCTZ continued after 600cc of EBL and spinal anesthesia.

The system works because the rules are clear and the communication is consistent. This does not mean that we cover the orthopedic service at night. They are equally responsible for their patients under the items outlined above. In my view—and this might sound simplistic—the surgeon caused the post-op pain, so they should be responsible for managing it. On VTE prophylaxis, I might take a more nuanced view, but for our surgeons, they own the wound and the post-op follow-up, so they get the choice on what agent to use.

Would I accept an arrangement in which I covered all the orthopedic issues out of regular hours? Nope—not when they have primary responsibility for the case; they should always be directly available to the nurse. I think that anything else would be a system ripe for abuse.

Our exact rules will not work for every situation, but I would strongly encourage the two basic tenets from above: No. 1, the hospitalist should primarily admit and manage elderly hip fractures, and No. 2, clear rules of engagement should be established with your orthopedic or surgery group. It’s a discussion worth having during daylight hours, because trying to figure out the rules at 3 in the morning rarely ends well.

One of our providers wants to use adult hospitalists for coverage of inpatient orthopedic surgery patients. Is this acceptable practice? Are there qualifiers?

–Libby Gardner

Dr. Hospitalist responds:

Let’s see how far we can tackle this open-ended question. There has been lots of discussion on the topic of comanagement in the past by people eminently more qualified than I am. Still, it never hurts to take a fresh look at things.

For one, on the subject of admissions, I am a firm believer that hospitalists should admit all adult hip fractures. The overwhelming majority of the time, these patients are elderly with comorbid conditions. Sure, they are going to get their hip fixed, because the alternative is usually unacceptable, but some thought needs to go into the process. The orthopedic surgeon sees a hip that needs fixing and not much else. When issues like renal failure, afib, CHF, prior DVT, or dementia are present, hospitalists should take charge of the case. It is the best way to ensure that the patient receives optimal medical care and the documentation that goes along with it. I love our orthopedic surgeons, but I don’t want them primarily admitting, managing, and discharging my elderly patients. Let the surgeon do what they do best, which is operate, and leave the rest to us.

On the subject of orthopedic trauma, I take the exact opposite tack—this is not something for which I or most of my colleagues have expertise. A young, healthy patient with trauma should be admitted by the orthopedic service; that patient population’s complications are much more likely to be directly related to their trauma.

When it comes to elective surgery, when the admitting surgeon (orthopedic or otherwise) wants the help of a hospitalist, then I think it is of paramount importance to have clear “rules of engagement.” I think with good expectations, you can have a fantastic working relationship with your surgeons. Without them, it becomes a nightmare.

Here are my HM group’s rules for elective orthopedic surgery:

- Orthopedics handles all pain medications and VTE prophylaxis, including discharge prescriptions.

- Medicine handles all admit and discharge medication reconciliation (“med rec”).

- There is shared discussion on:

- Need for transfusion; and

- The VTE prophylaxis when a patient already is on chronic anticoagulation.

We do not vary from this protocol. I never adjust a patient’s pain medications. Even the floor nurses know this. Because I’m doing the admit med rec, it also means that the patient doesn’t have their HCTZ continued after 600cc of EBL and spinal anesthesia.

The system works because the rules are clear and the communication is consistent. This does not mean that we cover the orthopedic service at night. They are equally responsible for their patients under the items outlined above. In my view—and this might sound simplistic—the surgeon caused the post-op pain, so they should be responsible for managing it. On VTE prophylaxis, I might take a more nuanced view, but for our surgeons, they own the wound and the post-op follow-up, so they get the choice on what agent to use.

Would I accept an arrangement in which I covered all the orthopedic issues out of regular hours? Nope—not when they have primary responsibility for the case; they should always be directly available to the nurse. I think that anything else would be a system ripe for abuse.

Our exact rules will not work for every situation, but I would strongly encourage the two basic tenets from above: No. 1, the hospitalist should primarily admit and manage elderly hip fractures, and No. 2, clear rules of engagement should be established with your orthopedic or surgery group. It’s a discussion worth having during daylight hours, because trying to figure out the rules at 3 in the morning rarely ends well.

SHM's Quality and Safety Educators Academy: Preparing Successful Residents and Students

Tomorrow’s hospital will be increasingly oriented around quality and safety; today’s students must prepare to thrive in that environment.

That’s the philosophy behind SHM’s Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). Now in its second year, the two-and-a-half-day academy trains hospitalist educators to teach medical students and residents about quality and safety.

QSEA, co-hosted by SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine, is March 7-9 at Tempe Mission Palms in Tempe, Ariz. Registration is now open at www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea.

“In order to be successful, we must teach medical students and residents about these goals so that they incorporate them into their practice from day one,” says Jennifer S. Myers, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine, patient safety officer, and director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

Progress in quality improvement (QI) and patient safety has been slow because many current physicians aren’t familiar with the materials, creating what Dr. Myers refers to as a “faculty development” gap. QSEA is the first and only academy designed to close that gap for hospitalist faculty by giving them specific knowledge, skills, a take-home toolkit, and a brand-new peer network of other quality-minded educators.

A major part of the academy is dedicated to the career trajectory of educators and, in Dr. Myers’ words, “how a hospitalist can be successful in making quality and safety education a career path.”

Despite the serious topics, she also is quick to point out that the academy is anything but dry.

“You have to experience it,” she says. “We have a ton of fun. You will leave with a new family.”

At the end of the inaugural QSEA, the faculty and course directors were so energized by the attendees that they formed a human pyramid. “It was a great moment,” she says.

Dr. Myers says she still enjoys receiving email from QSEA attendees about their new adventures in quality and safety education. “This makes it all worth it and why the QSEA team does this work,” she says.

Tomorrow’s hospital will be increasingly oriented around quality and safety; today’s students must prepare to thrive in that environment.

That’s the philosophy behind SHM’s Quality and Safety Educators Academy (QSEA). Now in its second year, the two-and-a-half-day academy trains hospitalist educators to teach medical students and residents about quality and safety.

QSEA, co-hosted by SHM and the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine, is March 7-9 at Tempe Mission Palms in Tempe, Ariz. Registration is now open at www.hospitalmedicine.org/qsea.

“In order to be successful, we must teach medical students and residents about these goals so that they incorporate them into their practice from day one,” says Jennifer S. Myers, MD, associate professor of clinical medicine, patient safety officer, and director of quality and safety education at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine in Philadelphia.

Progress in quality improvement (QI) and patient safety has been slow because many current physicians aren’t familiar with the materials, creating what Dr. Myers refers to as a “faculty development” gap. QSEA is the first and only academy designed to close that gap for hospitalist faculty by giving them specific knowledge, skills, a take-home toolkit, and a brand-new peer network of other quality-minded educators.

A major part of the academy is dedicated to the career trajectory of educators and, in Dr. Myers’ words, “how a hospitalist can be successful in making quality and safety education a career path.”

Despite the serious topics, she also is quick to point out that the academy is anything but dry.

“You have to experience it,” she says. “We have a ton of fun. You will leave with a new family.”