User login

USPSTF Recommends Exercise To Prevent Falls in Older Adults

Exercise interventions are recommended to help prevent falls and fall-related morbidity in community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older who are at increased risk of falls, according to a new recommendation statement from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (JAMA. 2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.8481).

Falls remain the leading cause of injury-related morbidity and mortality among older adults in the United States, with approximately 27% of community-dwelling individuals aged 65 years and older reporting at least one fall in the past year, wrote lead author Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues.

The task force concluded with moderate certainty that exercise interventions yielded a moderate benefit in fall reduction among older adults at risk (grade B recommendation).

The decision to offer multifactorial fall prevention interventions to older adults at risk for falls should be individualized based on assessment of potential risks and benefits of these interventions, including circumstances of prior falls, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and the patient’s values and preferences (grade C recommendation), the authors wrote.

The exercise intervention could include individual or group activity, although most of the studies in the systematic review involved group exercise, the authors noted.

The recommendation was based on data from a systematic evidence review published in JAMA (2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.4166). The task force reviewed data from 83 randomized trials published between January 1, 2016, and May 8, 2023, deemed fair to good quality that examined six types of fall prevention interventions in a total of 48,839 individuals. Of these, 28 studies involved multifactorial interventions and 27 involved exercise interventions.

Overall, multifactorial interventions and exercise interventions were associated with a significant reduction in falls (incidence rate ratio 0.84 and 0.85, respectively).

Exercise interventions were significantly associated with reduced individual risk of one or more falls and injurious falls, but not with reduced individual risk of injurious falls. However, multifactorial interventions were not significantly associated with reductions in risk of one or more falls, injurious falls, fall-related fractures, individual risk of injurious falls, or individual risk of fall-related fractures.

Although teasing out the specific exercise components that are most effective for fall prevention is challenging, the most commonly studied components associated with reduced risk of falls included gait training, balance training, and functional training, followed by strength and resistance training, the task force noted.

Duration of exercise interventions in the reviewed studies ranged from 2 to 30 months and the most common frequency of sessions was 2 to 3 per week.

Based on these findings, the task force found that exercise had the most consistent benefits for reduced risk across several fall-related outcomes. Although individuals in the studies of multifactorial interventions were at increased risk for falls, the multistep process of interventions to address an individual’s multiple risk factors limited their effectiveness, in part because of logistical challenges and inconsistent adherence, the authors wrote.

The results of the review were limited by several factors, including the focus on studies with a primary or secondary aim of fall prevention, the fact that the recommendation does not apply to many subgroups of older adults, and the lack of data on health outcomes unrelated to falls that were associated with the interventions, the authors noted.

The new recommendation is consistent with and replaces the 2018 USPSTF recommendation on interventions for fall prevention in community-dwelling older adults, but without the recommendation against vitamin D supplementation as a fall prevention intervention. The new recommendation does not address vitamin D use; evidence will be examined in a separate recommendation, the task force wrote.

How to Get Older Adults Moving

“The biggest obstacle to exercise is patient inertia and choice to engage in other sedentary activities,” David B. Reuben, MD, and David A. Ganz, MD, both of the University of California, Los Angeles, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.9063).

“Given the demonstrated benefits of exercise for cardiovascular disease, cognitive function, and favorable associations with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality, specific fall prevention exercise recommendations need to be considered in the context of universal exercise recommendations, including aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise,” the authors wrote. However, maintaining regular exercise is a challenge for many older adults, and more research is needed on factors that drive exercise initiation and adherence in this population, they said.

Multifactorial fall assessments in particular take time, and more fall prevention programs are needed that include multifactorial assessments and interventions, the editorialists said. “Even if primary care clinicians faithfully implement the USPSTF recommendations, a significant reduction in falls and their resulting injuries is still far off,” in part, because of the need for more programs and policies, and the need to improve access to exercise programs and provide insurance coverage for them, they noted.

“Above all, older persons need to be active participants in exercise and reduction of risk factors for falls,” the editorialists concluded.

The research for the recommendation was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Ganz disclosed serving as an author of the 2022 World Guidelines for Falls Prevention and Management for Older Adults.

Exercise interventions are recommended to help prevent falls and fall-related morbidity in community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older who are at increased risk of falls, according to a new recommendation statement from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (JAMA. 2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.8481).

Falls remain the leading cause of injury-related morbidity and mortality among older adults in the United States, with approximately 27% of community-dwelling individuals aged 65 years and older reporting at least one fall in the past year, wrote lead author Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues.

The task force concluded with moderate certainty that exercise interventions yielded a moderate benefit in fall reduction among older adults at risk (grade B recommendation).

The decision to offer multifactorial fall prevention interventions to older adults at risk for falls should be individualized based on assessment of potential risks and benefits of these interventions, including circumstances of prior falls, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and the patient’s values and preferences (grade C recommendation), the authors wrote.

The exercise intervention could include individual or group activity, although most of the studies in the systematic review involved group exercise, the authors noted.

The recommendation was based on data from a systematic evidence review published in JAMA (2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.4166). The task force reviewed data from 83 randomized trials published between January 1, 2016, and May 8, 2023, deemed fair to good quality that examined six types of fall prevention interventions in a total of 48,839 individuals. Of these, 28 studies involved multifactorial interventions and 27 involved exercise interventions.

Overall, multifactorial interventions and exercise interventions were associated with a significant reduction in falls (incidence rate ratio 0.84 and 0.85, respectively).

Exercise interventions were significantly associated with reduced individual risk of one or more falls and injurious falls, but not with reduced individual risk of injurious falls. However, multifactorial interventions were not significantly associated with reductions in risk of one or more falls, injurious falls, fall-related fractures, individual risk of injurious falls, or individual risk of fall-related fractures.

Although teasing out the specific exercise components that are most effective for fall prevention is challenging, the most commonly studied components associated with reduced risk of falls included gait training, balance training, and functional training, followed by strength and resistance training, the task force noted.

Duration of exercise interventions in the reviewed studies ranged from 2 to 30 months and the most common frequency of sessions was 2 to 3 per week.

Based on these findings, the task force found that exercise had the most consistent benefits for reduced risk across several fall-related outcomes. Although individuals in the studies of multifactorial interventions were at increased risk for falls, the multistep process of interventions to address an individual’s multiple risk factors limited their effectiveness, in part because of logistical challenges and inconsistent adherence, the authors wrote.

The results of the review were limited by several factors, including the focus on studies with a primary or secondary aim of fall prevention, the fact that the recommendation does not apply to many subgroups of older adults, and the lack of data on health outcomes unrelated to falls that were associated with the interventions, the authors noted.

The new recommendation is consistent with and replaces the 2018 USPSTF recommendation on interventions for fall prevention in community-dwelling older adults, but without the recommendation against vitamin D supplementation as a fall prevention intervention. The new recommendation does not address vitamin D use; evidence will be examined in a separate recommendation, the task force wrote.

How to Get Older Adults Moving

“The biggest obstacle to exercise is patient inertia and choice to engage in other sedentary activities,” David B. Reuben, MD, and David A. Ganz, MD, both of the University of California, Los Angeles, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.9063).

“Given the demonstrated benefits of exercise for cardiovascular disease, cognitive function, and favorable associations with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality, specific fall prevention exercise recommendations need to be considered in the context of universal exercise recommendations, including aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise,” the authors wrote. However, maintaining regular exercise is a challenge for many older adults, and more research is needed on factors that drive exercise initiation and adherence in this population, they said.

Multifactorial fall assessments in particular take time, and more fall prevention programs are needed that include multifactorial assessments and interventions, the editorialists said. “Even if primary care clinicians faithfully implement the USPSTF recommendations, a significant reduction in falls and their resulting injuries is still far off,” in part, because of the need for more programs and policies, and the need to improve access to exercise programs and provide insurance coverage for them, they noted.

“Above all, older persons need to be active participants in exercise and reduction of risk factors for falls,” the editorialists concluded.

The research for the recommendation was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Ganz disclosed serving as an author of the 2022 World Guidelines for Falls Prevention and Management for Older Adults.

Exercise interventions are recommended to help prevent falls and fall-related morbidity in community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older who are at increased risk of falls, according to a new recommendation statement from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) (JAMA. 2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.8481).

Falls remain the leading cause of injury-related morbidity and mortality among older adults in the United States, with approximately 27% of community-dwelling individuals aged 65 years and older reporting at least one fall in the past year, wrote lead author Wanda K. Nicholson, MD, of George Washington University, Washington, and colleagues.

The task force concluded with moderate certainty that exercise interventions yielded a moderate benefit in fall reduction among older adults at risk (grade B recommendation).

The decision to offer multifactorial fall prevention interventions to older adults at risk for falls should be individualized based on assessment of potential risks and benefits of these interventions, including circumstances of prior falls, presence of comorbid medical conditions, and the patient’s values and preferences (grade C recommendation), the authors wrote.

The exercise intervention could include individual or group activity, although most of the studies in the systematic review involved group exercise, the authors noted.

The recommendation was based on data from a systematic evidence review published in JAMA (2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.4166). The task force reviewed data from 83 randomized trials published between January 1, 2016, and May 8, 2023, deemed fair to good quality that examined six types of fall prevention interventions in a total of 48,839 individuals. Of these, 28 studies involved multifactorial interventions and 27 involved exercise interventions.

Overall, multifactorial interventions and exercise interventions were associated with a significant reduction in falls (incidence rate ratio 0.84 and 0.85, respectively).

Exercise interventions were significantly associated with reduced individual risk of one or more falls and injurious falls, but not with reduced individual risk of injurious falls. However, multifactorial interventions were not significantly associated with reductions in risk of one or more falls, injurious falls, fall-related fractures, individual risk of injurious falls, or individual risk of fall-related fractures.

Although teasing out the specific exercise components that are most effective for fall prevention is challenging, the most commonly studied components associated with reduced risk of falls included gait training, balance training, and functional training, followed by strength and resistance training, the task force noted.

Duration of exercise interventions in the reviewed studies ranged from 2 to 30 months and the most common frequency of sessions was 2 to 3 per week.

Based on these findings, the task force found that exercise had the most consistent benefits for reduced risk across several fall-related outcomes. Although individuals in the studies of multifactorial interventions were at increased risk for falls, the multistep process of interventions to address an individual’s multiple risk factors limited their effectiveness, in part because of logistical challenges and inconsistent adherence, the authors wrote.

The results of the review were limited by several factors, including the focus on studies with a primary or secondary aim of fall prevention, the fact that the recommendation does not apply to many subgroups of older adults, and the lack of data on health outcomes unrelated to falls that were associated with the interventions, the authors noted.

The new recommendation is consistent with and replaces the 2018 USPSTF recommendation on interventions for fall prevention in community-dwelling older adults, but without the recommendation against vitamin D supplementation as a fall prevention intervention. The new recommendation does not address vitamin D use; evidence will be examined in a separate recommendation, the task force wrote.

How to Get Older Adults Moving

“The biggest obstacle to exercise is patient inertia and choice to engage in other sedentary activities,” David B. Reuben, MD, and David A. Ganz, MD, both of the University of California, Los Angeles, wrote in an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2024 Jun 4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2024.9063).

“Given the demonstrated benefits of exercise for cardiovascular disease, cognitive function, and favorable associations with all-cause, cardiovascular, and cancer mortality, specific fall prevention exercise recommendations need to be considered in the context of universal exercise recommendations, including aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise,” the authors wrote. However, maintaining regular exercise is a challenge for many older adults, and more research is needed on factors that drive exercise initiation and adherence in this population, they said.

Multifactorial fall assessments in particular take time, and more fall prevention programs are needed that include multifactorial assessments and interventions, the editorialists said. “Even if primary care clinicians faithfully implement the USPSTF recommendations, a significant reduction in falls and their resulting injuries is still far off,” in part, because of the need for more programs and policies, and the need to improve access to exercise programs and provide insurance coverage for them, they noted.

“Above all, older persons need to be active participants in exercise and reduction of risk factors for falls,” the editorialists concluded.

The research for the recommendation was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The authors had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Ganz disclosed serving as an author of the 2022 World Guidelines for Falls Prevention and Management for Older Adults.

FROM JAMA

Are Secondary Osteoporosis Causes Under-Investigated?

NEW ORLEANS — Postmenopausal women with osteoporosis may not be receiving all the recommended tests to rule out secondary causes of bone loss prior to treatment initiation, new research found.

In a single-center chart review of 150 postmenopausal women who had been diagnosed and treated for osteoporosis, most had received a complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, thyroid screening, and vitamin D testing. However, one in four had not been tested for a parathyroid hormone (PTH) level, and in nearly two thirds, a 24-hour urine calcium collection had not been ordered.

Overall, less than a third had received the complete workup for secondary osteoporosis causes as recommended by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the Endocrine Society.

“An appropriate evaluation for secondary causes of osteoporosis is essential because it impacts different treatment options and modalities. We discovered low rates of complete testing for secondary causes of osteoporosis in our patient population prior to treatment initiation,” said Kajol Manglani, MD, an internal medicine resident at Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC, and colleagues, in a poster at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) annual meeting held on May 9-12, 2024.

First author Sheetal Bulchandani, MD, said in an interview, “It depends a lot on clinical judgment, but there are certain things that everybody with osteoporosis should be evaluated for. We looked for the things that all the guidelines recommend.”

Studies have suggested that up to 30% of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis have secondary causes, noted Dr. Bulchandani, who conducted the study as a postdoctoral fellow with colleagues at Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital and is now in private endocrine practice in Petersburg, Virginia.

“It’s important not to assume that every woman who walks in with osteoporosis has postmenopausal osteoporosis. I think it would be appropriate to at least discuss with the patients what would warrant certain kinds of clinical workup. … If you don’t figure out if there is an underlying cause, you may end up using an unnecessary medication,” Dr. Bulchandani said.

Are You Missing Something Treatable?

For example, she said, if the patient has underlying hyperparathyroidism and is treated with osteoporosis medications, “you might not see the desired or expected outcome in their bone density.”

Asked to comment, Rachel Pessah-Pollack, MD, clinical associate professor at the Holman Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at New York University School of Medicine, New York City, told this news organization, “Certainly, if you have patients who have osteoporosis, it’s important to take a good history and consider secondary causes of bone loss because you may find a treatable etiology that actually can improve their bone density without even starting on a medication.”

Dr. Pessah-Pollack, who was an author of the 2020 AACE/American College of Endocrinology 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoporosis, said a 24-hour urine calcium collection, not a spot calcium check, is “super important because you’re looking to see if there’s any evidence of hypercalciuria or malabsorption that may be associated with higher rates of bone loss. … These may be a little more cumbersome and harder to get patients to do and more logistics to arrange. But clearly, if you pick up hypercalciuria, that is a potentially treatable etiology and can improve bone density as well.”

Another example, Dr. Pessah-Pollack said, is “if they have a low serum calcium level and high PTH, that would be a real reason to look for celiac disease. By not getting that PTH level, you may be missing that potential diagnosis. There is a wide range of additional causes of osteoporosis ranging from common conditions such as hyperthyroidism to rare conditions such as Cushing disease.”

Differences in Ordering Found Across Specialties

The 150 postmenopausal women were all receiving treatment with either alendronate, denosumab, or zoledronic acid. Their average age was 64.7 years, and 63% were seeing an endocrinologist.

Complete workups as per AACE and Endocrine Society guidelines had been performed in just 28% of those who saw an endocrinologist and 12.5% of patients seen by a rheumatologist, in contrast to 84% of those who saw the head of the hospital’s fracture prevention program.

Overall, across all specialties, just 28.67% had the complete recommended workup for secondary osteoporosis causes.

The most missed test was a 24-hour urine calcium collection, ordered for just 38% of the patients, while PTH was ordered for 73% and phosphorus for 80%. The rest were more commonly ordered: Thyroid-stimulating hormone level for 92.7%, complete blood cell count for 91.3%, basic metabolic panel for 100%, and vitamin D level for 96%.

The high rate of vitamin D testing is noteworthy, Dr. Pessah-Pollack said. “The fact that 96% of women are having vitamin D levels checked as part of an osteoporosis evaluation means that everybody’s aware about vitamin D deficiency, and people want to know what their vitamin D levels are. … That’s good because we want to identify vitamin D deficiency in our osteoporosis patients.”

But the low rate of complete secondary screening even by endocrinologists is concerning. “I look at this study as an opportunity for education that we can reinforce the importance of a secondary evaluation for our osteoporosis patients and really tailor which additional tests should be ordered for the individual patient,” Dr. Pessah-Pollack said.

In the poster, Dr. Bulchandani and colleagues wrote, “Further intervention will be aimed to ensure physicians undertake adequate evaluation before considering further treatment directions.” Possibilities that have been discussed include electronic health record alerts and educational materials for primary care providers, she told this news organization.

Dr. Manglani and Dr. Bulchandani had no disclosures. Dr. Pessah-Pollack is an advisor for Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS — Postmenopausal women with osteoporosis may not be receiving all the recommended tests to rule out secondary causes of bone loss prior to treatment initiation, new research found.

In a single-center chart review of 150 postmenopausal women who had been diagnosed and treated for osteoporosis, most had received a complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, thyroid screening, and vitamin D testing. However, one in four had not been tested for a parathyroid hormone (PTH) level, and in nearly two thirds, a 24-hour urine calcium collection had not been ordered.

Overall, less than a third had received the complete workup for secondary osteoporosis causes as recommended by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the Endocrine Society.

“An appropriate evaluation for secondary causes of osteoporosis is essential because it impacts different treatment options and modalities. We discovered low rates of complete testing for secondary causes of osteoporosis in our patient population prior to treatment initiation,” said Kajol Manglani, MD, an internal medicine resident at Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC, and colleagues, in a poster at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) annual meeting held on May 9-12, 2024.

First author Sheetal Bulchandani, MD, said in an interview, “It depends a lot on clinical judgment, but there are certain things that everybody with osteoporosis should be evaluated for. We looked for the things that all the guidelines recommend.”

Studies have suggested that up to 30% of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis have secondary causes, noted Dr. Bulchandani, who conducted the study as a postdoctoral fellow with colleagues at Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital and is now in private endocrine practice in Petersburg, Virginia.

“It’s important not to assume that every woman who walks in with osteoporosis has postmenopausal osteoporosis. I think it would be appropriate to at least discuss with the patients what would warrant certain kinds of clinical workup. … If you don’t figure out if there is an underlying cause, you may end up using an unnecessary medication,” Dr. Bulchandani said.

Are You Missing Something Treatable?

For example, she said, if the patient has underlying hyperparathyroidism and is treated with osteoporosis medications, “you might not see the desired or expected outcome in their bone density.”

Asked to comment, Rachel Pessah-Pollack, MD, clinical associate professor at the Holman Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at New York University School of Medicine, New York City, told this news organization, “Certainly, if you have patients who have osteoporosis, it’s important to take a good history and consider secondary causes of bone loss because you may find a treatable etiology that actually can improve their bone density without even starting on a medication.”

Dr. Pessah-Pollack, who was an author of the 2020 AACE/American College of Endocrinology 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoporosis, said a 24-hour urine calcium collection, not a spot calcium check, is “super important because you’re looking to see if there’s any evidence of hypercalciuria or malabsorption that may be associated with higher rates of bone loss. … These may be a little more cumbersome and harder to get patients to do and more logistics to arrange. But clearly, if you pick up hypercalciuria, that is a potentially treatable etiology and can improve bone density as well.”

Another example, Dr. Pessah-Pollack said, is “if they have a low serum calcium level and high PTH, that would be a real reason to look for celiac disease. By not getting that PTH level, you may be missing that potential diagnosis. There is a wide range of additional causes of osteoporosis ranging from common conditions such as hyperthyroidism to rare conditions such as Cushing disease.”

Differences in Ordering Found Across Specialties

The 150 postmenopausal women were all receiving treatment with either alendronate, denosumab, or zoledronic acid. Their average age was 64.7 years, and 63% were seeing an endocrinologist.

Complete workups as per AACE and Endocrine Society guidelines had been performed in just 28% of those who saw an endocrinologist and 12.5% of patients seen by a rheumatologist, in contrast to 84% of those who saw the head of the hospital’s fracture prevention program.

Overall, across all specialties, just 28.67% had the complete recommended workup for secondary osteoporosis causes.

The most missed test was a 24-hour urine calcium collection, ordered for just 38% of the patients, while PTH was ordered for 73% and phosphorus for 80%. The rest were more commonly ordered: Thyroid-stimulating hormone level for 92.7%, complete blood cell count for 91.3%, basic metabolic panel for 100%, and vitamin D level for 96%.

The high rate of vitamin D testing is noteworthy, Dr. Pessah-Pollack said. “The fact that 96% of women are having vitamin D levels checked as part of an osteoporosis evaluation means that everybody’s aware about vitamin D deficiency, and people want to know what their vitamin D levels are. … That’s good because we want to identify vitamin D deficiency in our osteoporosis patients.”

But the low rate of complete secondary screening even by endocrinologists is concerning. “I look at this study as an opportunity for education that we can reinforce the importance of a secondary evaluation for our osteoporosis patients and really tailor which additional tests should be ordered for the individual patient,” Dr. Pessah-Pollack said.

In the poster, Dr. Bulchandani and colleagues wrote, “Further intervention will be aimed to ensure physicians undertake adequate evaluation before considering further treatment directions.” Possibilities that have been discussed include electronic health record alerts and educational materials for primary care providers, she told this news organization.

Dr. Manglani and Dr. Bulchandani had no disclosures. Dr. Pessah-Pollack is an advisor for Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

NEW ORLEANS — Postmenopausal women with osteoporosis may not be receiving all the recommended tests to rule out secondary causes of bone loss prior to treatment initiation, new research found.

In a single-center chart review of 150 postmenopausal women who had been diagnosed and treated for osteoporosis, most had received a complete blood cell count, basic metabolic panel, thyroid screening, and vitamin D testing. However, one in four had not been tested for a parathyroid hormone (PTH) level, and in nearly two thirds, a 24-hour urine calcium collection had not been ordered.

Overall, less than a third had received the complete workup for secondary osteoporosis causes as recommended by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) and the Endocrine Society.

“An appropriate evaluation for secondary causes of osteoporosis is essential because it impacts different treatment options and modalities. We discovered low rates of complete testing for secondary causes of osteoporosis in our patient population prior to treatment initiation,” said Kajol Manglani, MD, an internal medicine resident at Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital Center, Washington, DC, and colleagues, in a poster at the American Association of Clinical Endocrinology (AACE) annual meeting held on May 9-12, 2024.

First author Sheetal Bulchandani, MD, said in an interview, “It depends a lot on clinical judgment, but there are certain things that everybody with osteoporosis should be evaluated for. We looked for the things that all the guidelines recommend.”

Studies have suggested that up to 30% of postmenopausal women with osteoporosis have secondary causes, noted Dr. Bulchandani, who conducted the study as a postdoctoral fellow with colleagues at Georgetown University/MedStar Washington Hospital and is now in private endocrine practice in Petersburg, Virginia.

“It’s important not to assume that every woman who walks in with osteoporosis has postmenopausal osteoporosis. I think it would be appropriate to at least discuss with the patients what would warrant certain kinds of clinical workup. … If you don’t figure out if there is an underlying cause, you may end up using an unnecessary medication,” Dr. Bulchandani said.

Are You Missing Something Treatable?

For example, she said, if the patient has underlying hyperparathyroidism and is treated with osteoporosis medications, “you might not see the desired or expected outcome in their bone density.”

Asked to comment, Rachel Pessah-Pollack, MD, clinical associate professor at the Holman Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at New York University School of Medicine, New York City, told this news organization, “Certainly, if you have patients who have osteoporosis, it’s important to take a good history and consider secondary causes of bone loss because you may find a treatable etiology that actually can improve their bone density without even starting on a medication.”

Dr. Pessah-Pollack, who was an author of the 2020 AACE/American College of Endocrinology 2020 Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Osteoporosis, said a 24-hour urine calcium collection, not a spot calcium check, is “super important because you’re looking to see if there’s any evidence of hypercalciuria or malabsorption that may be associated with higher rates of bone loss. … These may be a little more cumbersome and harder to get patients to do and more logistics to arrange. But clearly, if you pick up hypercalciuria, that is a potentially treatable etiology and can improve bone density as well.”

Another example, Dr. Pessah-Pollack said, is “if they have a low serum calcium level and high PTH, that would be a real reason to look for celiac disease. By not getting that PTH level, you may be missing that potential diagnosis. There is a wide range of additional causes of osteoporosis ranging from common conditions such as hyperthyroidism to rare conditions such as Cushing disease.”

Differences in Ordering Found Across Specialties

The 150 postmenopausal women were all receiving treatment with either alendronate, denosumab, or zoledronic acid. Their average age was 64.7 years, and 63% were seeing an endocrinologist.

Complete workups as per AACE and Endocrine Society guidelines had been performed in just 28% of those who saw an endocrinologist and 12.5% of patients seen by a rheumatologist, in contrast to 84% of those who saw the head of the hospital’s fracture prevention program.

Overall, across all specialties, just 28.67% had the complete recommended workup for secondary osteoporosis causes.

The most missed test was a 24-hour urine calcium collection, ordered for just 38% of the patients, while PTH was ordered for 73% and phosphorus for 80%. The rest were more commonly ordered: Thyroid-stimulating hormone level for 92.7%, complete blood cell count for 91.3%, basic metabolic panel for 100%, and vitamin D level for 96%.

The high rate of vitamin D testing is noteworthy, Dr. Pessah-Pollack said. “The fact that 96% of women are having vitamin D levels checked as part of an osteoporosis evaluation means that everybody’s aware about vitamin D deficiency, and people want to know what their vitamin D levels are. … That’s good because we want to identify vitamin D deficiency in our osteoporosis patients.”

But the low rate of complete secondary screening even by endocrinologists is concerning. “I look at this study as an opportunity for education that we can reinforce the importance of a secondary evaluation for our osteoporosis patients and really tailor which additional tests should be ordered for the individual patient,” Dr. Pessah-Pollack said.

In the poster, Dr. Bulchandani and colleagues wrote, “Further intervention will be aimed to ensure physicians undertake adequate evaluation before considering further treatment directions.” Possibilities that have been discussed include electronic health record alerts and educational materials for primary care providers, she told this news organization.

Dr. Manglani and Dr. Bulchandani had no disclosures. Dr. Pessah-Pollack is an advisor for Boehringer Ingelheim and Eli Lilly.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Anti-Osteoporosis Drugs Found Just as Effective in Seniors

TOPLINE:

Anti-osteoporosis medications reduce fracture risk similarly, regardless of whether patients are younger or older than 70 years.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators conducted the study as part of a to assess bone mineral density as a surrogate marker for fracture risk.

- Analyses used individual patient data from 23 randomized placebo-controlled trials of anti-osteoporosis medications (11 of bisphosphonates, four of selective estrogen receptor modulators, three of anabolic medications, two of hormone replacement therapy, and one each of odanacatib, denosumab, and romosozumab).

- Overall, 43% of the included 123,164 patients were aged 70 years or older.

- The main outcomes were fractures and bone mineral density.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a similar benefit regardless of age when it came to the reduction in risks for hip fracture (odds ratio, 0.65 vs 0.72; P for interaction = .50) and any fracture (odds ratio, 0.72 vs 0.70; P for interaction = .20).

- Findings were comparable in analyses restricted to bisphosphonate trials, except that the reduction in hip fracture risk was greater among the younger group (hazard ratio, 0.44 vs 0.79; P for interaction = .02).

- The benefit of anti-osteoporosis medication in increasing hip and spine bone mineral density at 24 months was significantly greater among the older patients.

IN PRACTICE:

Taken together, the study results “strongly support treatment in those over age 70,” the authors wrote. “These are important findings with potential impact in patient treatment since it goes against a common misconception that medications are less effective in older people,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Marian Schini, MD, PhD, FHEA, University of Sheffield, England, and was published online in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included a preponderance of female patients (99%), possible residual confounding, a lack of analysis of adverse effects, and potentially different findings using alternate age cutoffs.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the American Society for Bone Mineral Research. Some authors disclosed affiliations with companies that manufacture anti-osteoporosis drugs.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Anti-osteoporosis medications reduce fracture risk similarly, regardless of whether patients are younger or older than 70 years.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators conducted the study as part of a to assess bone mineral density as a surrogate marker for fracture risk.

- Analyses used individual patient data from 23 randomized placebo-controlled trials of anti-osteoporosis medications (11 of bisphosphonates, four of selective estrogen receptor modulators, three of anabolic medications, two of hormone replacement therapy, and one each of odanacatib, denosumab, and romosozumab).

- Overall, 43% of the included 123,164 patients were aged 70 years or older.

- The main outcomes were fractures and bone mineral density.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a similar benefit regardless of age when it came to the reduction in risks for hip fracture (odds ratio, 0.65 vs 0.72; P for interaction = .50) and any fracture (odds ratio, 0.72 vs 0.70; P for interaction = .20).

- Findings were comparable in analyses restricted to bisphosphonate trials, except that the reduction in hip fracture risk was greater among the younger group (hazard ratio, 0.44 vs 0.79; P for interaction = .02).

- The benefit of anti-osteoporosis medication in increasing hip and spine bone mineral density at 24 months was significantly greater among the older patients.

IN PRACTICE:

Taken together, the study results “strongly support treatment in those over age 70,” the authors wrote. “These are important findings with potential impact in patient treatment since it goes against a common misconception that medications are less effective in older people,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Marian Schini, MD, PhD, FHEA, University of Sheffield, England, and was published online in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included a preponderance of female patients (99%), possible residual confounding, a lack of analysis of adverse effects, and potentially different findings using alternate age cutoffs.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the American Society for Bone Mineral Research. Some authors disclosed affiliations with companies that manufacture anti-osteoporosis drugs.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

Anti-osteoporosis medications reduce fracture risk similarly, regardless of whether patients are younger or older than 70 years.

METHODOLOGY:

- Investigators conducted the study as part of a to assess bone mineral density as a surrogate marker for fracture risk.

- Analyses used individual patient data from 23 randomized placebo-controlled trials of anti-osteoporosis medications (11 of bisphosphonates, four of selective estrogen receptor modulators, three of anabolic medications, two of hormone replacement therapy, and one each of odanacatib, denosumab, and romosozumab).

- Overall, 43% of the included 123,164 patients were aged 70 years or older.

- The main outcomes were fractures and bone mineral density.

TAKEAWAY:

- There was a similar benefit regardless of age when it came to the reduction in risks for hip fracture (odds ratio, 0.65 vs 0.72; P for interaction = .50) and any fracture (odds ratio, 0.72 vs 0.70; P for interaction = .20).

- Findings were comparable in analyses restricted to bisphosphonate trials, except that the reduction in hip fracture risk was greater among the younger group (hazard ratio, 0.44 vs 0.79; P for interaction = .02).

- The benefit of anti-osteoporosis medication in increasing hip and spine bone mineral density at 24 months was significantly greater among the older patients.

IN PRACTICE:

Taken together, the study results “strongly support treatment in those over age 70,” the authors wrote. “These are important findings with potential impact in patient treatment since it goes against a common misconception that medications are less effective in older people,” they added.

SOURCE:

The study was led by Marian Schini, MD, PhD, FHEA, University of Sheffield, England, and was published online in the Journal of Bone and Mineral Research.

LIMITATIONS:

Limitations included a preponderance of female patients (99%), possible residual confounding, a lack of analysis of adverse effects, and potentially different findings using alternate age cutoffs.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was funded by the American Society for Bone Mineral Research. Some authors disclosed affiliations with companies that manufacture anti-osteoporosis drugs.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Is It Possible to Reverse Osteoporosis?

Fractures, particularly hip and spine fractures, are a major cause of mortality and morbidity among older individuals. The term “osteoporosis” indicates increased porosity of bones resulting in low bone density; increased bone fragility; and an increased risk for fracture, often with minimal trauma.

During the adolescent years, bone accrues at a rapid rate, and optimal bone accrual during this time is essential to attain optimal peak bone mass, typically achieved in the third decade of life. Bone mass then stays stable until the 40s-50s, after which it starts to decline. One’s peak bone mass sets the stage for both immediate and future bone health. Individuals with lower peak bone mass tend to have less optimal bone health throughout their lives, and this becomes particularly problematic in older men and in the postmenopausal years for women.

One’s genes have a major impact on bone density and are currently not modifiable.

Modifiable factors include mechanical loading of bones through exercise activity, maintaining a normal body weight, and ensuring adequate intake of micronutrients (including calcium and vitamin D) and macronutrients. Medications such as glucocorticoids that have deleterious effects on bones should be limited as far as possible. Endocrine, gastrointestinal, renal, and rheumatologic conditions and others, such as cancer, which are known to be associated with reduced bone density and increased fracture risk, should be managed appropriately.

A deficiency of the gonadal hormones (estrogen and testosterone) and high blood concentrations of cortisol are particularly deleterious to bone. Hormone replacement therapy in those with gonadal hormone deficiency and strategies to reduce cortisol levels in those with hypercortisolemia are essential to prevent osteoporosis and also improve bone density over time. The same applies to management of conditions such as anorexia nervosa, relative energy deficiency in sports, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, chronic kidney disease, and chronic arthritis.

Once osteoporosis has developed, depending on the cause, these strategies may not be sufficient to completely reverse the condition, and pharmacologic therapy may be necessary to improve bone density and reduce fracture risk. This is particularly an issue with postmenopausal women and older men. In these individuals, medications that increase bone formation or reduce bone loss may be necessary.

Medications that reduce bone loss include bisphosphonates and denosumab; these are also called “antiresorptive medications” because they reduce bone resorption by cells called osteoclasts. Bisphosphonates include alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, pamidronate, and zoledronic acid, and these medications have direct effects on osteoclasts, reducing their activity. Some bisphosphonates, such as alendronate and risedronate, are taken orally (daily, weekly, or monthly, depending on the medication and its strength), whereas others, such as pamidronate and zoledronic acid, are administered intravenously: every 3-4 months for pamidronate and every 6-12 months for zoledronic acid. Ibandronate is available both orally and intravenously.

Denosumab is a medication that inhibits the action of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa ligand 1 (RANKL), which otherwise increases osteoclast activity. It is administered as a subcutaneous injection every 6 months to treat osteoporosis. One concern with denosumab is a rapid increase in bone loss after its discontinuation.

Medications that increase bone formation are called bone anabolics and include teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab. Teriparatide is a synthetic form of parathyroid hormone (recombinant PTH1-34) administered daily for up to 2 years. Abaloparatide is a synthetic analog of parathyroid hormone–related peptide (PTHrP), which is also administered daily as a subcutaneous injection. Romosozumab inhibits sclerostin (a substance that otherwise reduces bone formation and increases bone resorption) and is administered as a subcutaneous injection once a month. Effects of these medications tend to be lost after they are discontinued.

In 2019, the Endocrine Society published guidelines for managing postmenopausal osteoporosis. The guidelines recommend lifestyle modifications, including attention to diet, calcium and vitamin D supplements, and weight-bearing exercise for all postmenopausal women. They also recommend assessing fracture risk using country-specific existing models.

Guidelines vary depending on whether fracture risk is low, moderate, or high. Patients at low risk are followed and reassessed every 2-4 years for fracture risk. Those at moderate risk may be followed similarly or prescribed bisphosphonates. Those at high risk are prescribed an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate or denosumab, or a bone anabolic, such as teriparatide or abaloparatide (for up to 2 years) or romosozumab (for a year), with calcium and vitamin D and are reassessed at defined intervals for fracture risk; subsequent management then depends on the assessed fracture risk.

People who are on a bone anabolic should typically follow this with an antiresorptive medication to maintain the gains achieved with the former after that medication is discontinued. Patients who discontinue denosumab should be switched to bisphosphonates to prevent the increase in bone loss that typically occurs.

In postmenopausal women who are intolerant to or inappropriate for use of these medications, guidelines vary depending on age (younger or older than 60 years) and presence or absence of vasomotor symptoms (such as hot flashes). Options could include the use of calcium and vitamin D supplements; hormone replacement therapy with estrogen with or without a progestin; or selective estrogen receptor modulators (such as raloxifene or bazedoxifene), tibolone, or calcitonin.

It’s important to recognize that all pharmacologic therapy carries the risk for adverse events, and it’s essential to take the necessary steps to prevent, monitor for, and manage any adverse effects that may develop.

Managing osteoporosis in older men could include the use of bone anabolics and/or antiresorptives. In younger individuals, use of pharmacologic therapy is less common but sometimes necessary, particularly when bone density is very low and associated with a problematic fracture history — for example, in those with genetic conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta. Furthermore, the occurrence of vertebral compression fractures often requires bisphosphonate treatment regardless of bone density, particularly in patients on chronic glucocorticoid therapy.

Preventing osteoporosis is best managed by paying attention to lifestyle; optimizing nutrition and calcium and vitamin D intake; and managing conditions and limiting the use of medications that reduce bone density.

However, in certain patients, these measures are not enough, and pharmacologic therapy with bone anabolics or antiresorptives may be necessary to improve bone density and reduce fracture risk.

Dr. Misra, of the University of Virginia and UVA Health Children’s Hospital, Charlottesville, disclosed ties with AbbVie, Sanofi, and Ipsen.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Fractures, particularly hip and spine fractures, are a major cause of mortality and morbidity among older individuals. The term “osteoporosis” indicates increased porosity of bones resulting in low bone density; increased bone fragility; and an increased risk for fracture, often with minimal trauma.

During the adolescent years, bone accrues at a rapid rate, and optimal bone accrual during this time is essential to attain optimal peak bone mass, typically achieved in the third decade of life. Bone mass then stays stable until the 40s-50s, after which it starts to decline. One’s peak bone mass sets the stage for both immediate and future bone health. Individuals with lower peak bone mass tend to have less optimal bone health throughout their lives, and this becomes particularly problematic in older men and in the postmenopausal years for women.

One’s genes have a major impact on bone density and are currently not modifiable.

Modifiable factors include mechanical loading of bones through exercise activity, maintaining a normal body weight, and ensuring adequate intake of micronutrients (including calcium and vitamin D) and macronutrients. Medications such as glucocorticoids that have deleterious effects on bones should be limited as far as possible. Endocrine, gastrointestinal, renal, and rheumatologic conditions and others, such as cancer, which are known to be associated with reduced bone density and increased fracture risk, should be managed appropriately.

A deficiency of the gonadal hormones (estrogen and testosterone) and high blood concentrations of cortisol are particularly deleterious to bone. Hormone replacement therapy in those with gonadal hormone deficiency and strategies to reduce cortisol levels in those with hypercortisolemia are essential to prevent osteoporosis and also improve bone density over time. The same applies to management of conditions such as anorexia nervosa, relative energy deficiency in sports, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, chronic kidney disease, and chronic arthritis.

Once osteoporosis has developed, depending on the cause, these strategies may not be sufficient to completely reverse the condition, and pharmacologic therapy may be necessary to improve bone density and reduce fracture risk. This is particularly an issue with postmenopausal women and older men. In these individuals, medications that increase bone formation or reduce bone loss may be necessary.

Medications that reduce bone loss include bisphosphonates and denosumab; these are also called “antiresorptive medications” because they reduce bone resorption by cells called osteoclasts. Bisphosphonates include alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, pamidronate, and zoledronic acid, and these medications have direct effects on osteoclasts, reducing their activity. Some bisphosphonates, such as alendronate and risedronate, are taken orally (daily, weekly, or monthly, depending on the medication and its strength), whereas others, such as pamidronate and zoledronic acid, are administered intravenously: every 3-4 months for pamidronate and every 6-12 months for zoledronic acid. Ibandronate is available both orally and intravenously.

Denosumab is a medication that inhibits the action of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa ligand 1 (RANKL), which otherwise increases osteoclast activity. It is administered as a subcutaneous injection every 6 months to treat osteoporosis. One concern with denosumab is a rapid increase in bone loss after its discontinuation.

Medications that increase bone formation are called bone anabolics and include teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab. Teriparatide is a synthetic form of parathyroid hormone (recombinant PTH1-34) administered daily for up to 2 years. Abaloparatide is a synthetic analog of parathyroid hormone–related peptide (PTHrP), which is also administered daily as a subcutaneous injection. Romosozumab inhibits sclerostin (a substance that otherwise reduces bone formation and increases bone resorption) and is administered as a subcutaneous injection once a month. Effects of these medications tend to be lost after they are discontinued.

In 2019, the Endocrine Society published guidelines for managing postmenopausal osteoporosis. The guidelines recommend lifestyle modifications, including attention to diet, calcium and vitamin D supplements, and weight-bearing exercise for all postmenopausal women. They also recommend assessing fracture risk using country-specific existing models.

Guidelines vary depending on whether fracture risk is low, moderate, or high. Patients at low risk are followed and reassessed every 2-4 years for fracture risk. Those at moderate risk may be followed similarly or prescribed bisphosphonates. Those at high risk are prescribed an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate or denosumab, or a bone anabolic, such as teriparatide or abaloparatide (for up to 2 years) or romosozumab (for a year), with calcium and vitamin D and are reassessed at defined intervals for fracture risk; subsequent management then depends on the assessed fracture risk.

People who are on a bone anabolic should typically follow this with an antiresorptive medication to maintain the gains achieved with the former after that medication is discontinued. Patients who discontinue denosumab should be switched to bisphosphonates to prevent the increase in bone loss that typically occurs.

In postmenopausal women who are intolerant to or inappropriate for use of these medications, guidelines vary depending on age (younger or older than 60 years) and presence or absence of vasomotor symptoms (such as hot flashes). Options could include the use of calcium and vitamin D supplements; hormone replacement therapy with estrogen with or without a progestin; or selective estrogen receptor modulators (such as raloxifene or bazedoxifene), tibolone, or calcitonin.

It’s important to recognize that all pharmacologic therapy carries the risk for adverse events, and it’s essential to take the necessary steps to prevent, monitor for, and manage any adverse effects that may develop.

Managing osteoporosis in older men could include the use of bone anabolics and/or antiresorptives. In younger individuals, use of pharmacologic therapy is less common but sometimes necessary, particularly when bone density is very low and associated with a problematic fracture history — for example, in those with genetic conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta. Furthermore, the occurrence of vertebral compression fractures often requires bisphosphonate treatment regardless of bone density, particularly in patients on chronic glucocorticoid therapy.

Preventing osteoporosis is best managed by paying attention to lifestyle; optimizing nutrition and calcium and vitamin D intake; and managing conditions and limiting the use of medications that reduce bone density.

However, in certain patients, these measures are not enough, and pharmacologic therapy with bone anabolics or antiresorptives may be necessary to improve bone density and reduce fracture risk.

Dr. Misra, of the University of Virginia and UVA Health Children’s Hospital, Charlottesville, disclosed ties with AbbVie, Sanofi, and Ipsen.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Fractures, particularly hip and spine fractures, are a major cause of mortality and morbidity among older individuals. The term “osteoporosis” indicates increased porosity of bones resulting in low bone density; increased bone fragility; and an increased risk for fracture, often with minimal trauma.

During the adolescent years, bone accrues at a rapid rate, and optimal bone accrual during this time is essential to attain optimal peak bone mass, typically achieved in the third decade of life. Bone mass then stays stable until the 40s-50s, after which it starts to decline. One’s peak bone mass sets the stage for both immediate and future bone health. Individuals with lower peak bone mass tend to have less optimal bone health throughout their lives, and this becomes particularly problematic in older men and in the postmenopausal years for women.

One’s genes have a major impact on bone density and are currently not modifiable.

Modifiable factors include mechanical loading of bones through exercise activity, maintaining a normal body weight, and ensuring adequate intake of micronutrients (including calcium and vitamin D) and macronutrients. Medications such as glucocorticoids that have deleterious effects on bones should be limited as far as possible. Endocrine, gastrointestinal, renal, and rheumatologic conditions and others, such as cancer, which are known to be associated with reduced bone density and increased fracture risk, should be managed appropriately.

A deficiency of the gonadal hormones (estrogen and testosterone) and high blood concentrations of cortisol are particularly deleterious to bone. Hormone replacement therapy in those with gonadal hormone deficiency and strategies to reduce cortisol levels in those with hypercortisolemia are essential to prevent osteoporosis and also improve bone density over time. The same applies to management of conditions such as anorexia nervosa, relative energy deficiency in sports, inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, cystic fibrosis, chronic kidney disease, and chronic arthritis.

Once osteoporosis has developed, depending on the cause, these strategies may not be sufficient to completely reverse the condition, and pharmacologic therapy may be necessary to improve bone density and reduce fracture risk. This is particularly an issue with postmenopausal women and older men. In these individuals, medications that increase bone formation or reduce bone loss may be necessary.

Medications that reduce bone loss include bisphosphonates and denosumab; these are also called “antiresorptive medications” because they reduce bone resorption by cells called osteoclasts. Bisphosphonates include alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, pamidronate, and zoledronic acid, and these medications have direct effects on osteoclasts, reducing their activity. Some bisphosphonates, such as alendronate and risedronate, are taken orally (daily, weekly, or monthly, depending on the medication and its strength), whereas others, such as pamidronate and zoledronic acid, are administered intravenously: every 3-4 months for pamidronate and every 6-12 months for zoledronic acid. Ibandronate is available both orally and intravenously.

Denosumab is a medication that inhibits the action of receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappa ligand 1 (RANKL), which otherwise increases osteoclast activity. It is administered as a subcutaneous injection every 6 months to treat osteoporosis. One concern with denosumab is a rapid increase in bone loss after its discontinuation.

Medications that increase bone formation are called bone anabolics and include teriparatide, abaloparatide, and romosozumab. Teriparatide is a synthetic form of parathyroid hormone (recombinant PTH1-34) administered daily for up to 2 years. Abaloparatide is a synthetic analog of parathyroid hormone–related peptide (PTHrP), which is also administered daily as a subcutaneous injection. Romosozumab inhibits sclerostin (a substance that otherwise reduces bone formation and increases bone resorption) and is administered as a subcutaneous injection once a month. Effects of these medications tend to be lost after they are discontinued.

In 2019, the Endocrine Society published guidelines for managing postmenopausal osteoporosis. The guidelines recommend lifestyle modifications, including attention to diet, calcium and vitamin D supplements, and weight-bearing exercise for all postmenopausal women. They also recommend assessing fracture risk using country-specific existing models.

Guidelines vary depending on whether fracture risk is low, moderate, or high. Patients at low risk are followed and reassessed every 2-4 years for fracture risk. Those at moderate risk may be followed similarly or prescribed bisphosphonates. Those at high risk are prescribed an antiresorptive, such as a bisphosphonate or denosumab, or a bone anabolic, such as teriparatide or abaloparatide (for up to 2 years) or romosozumab (for a year), with calcium and vitamin D and are reassessed at defined intervals for fracture risk; subsequent management then depends on the assessed fracture risk.

People who are on a bone anabolic should typically follow this with an antiresorptive medication to maintain the gains achieved with the former after that medication is discontinued. Patients who discontinue denosumab should be switched to bisphosphonates to prevent the increase in bone loss that typically occurs.

In postmenopausal women who are intolerant to or inappropriate for use of these medications, guidelines vary depending on age (younger or older than 60 years) and presence or absence of vasomotor symptoms (such as hot flashes). Options could include the use of calcium and vitamin D supplements; hormone replacement therapy with estrogen with or without a progestin; or selective estrogen receptor modulators (such as raloxifene or bazedoxifene), tibolone, or calcitonin.

It’s important to recognize that all pharmacologic therapy carries the risk for adverse events, and it’s essential to take the necessary steps to prevent, monitor for, and manage any adverse effects that may develop.

Managing osteoporosis in older men could include the use of bone anabolics and/or antiresorptives. In younger individuals, use of pharmacologic therapy is less common but sometimes necessary, particularly when bone density is very low and associated with a problematic fracture history — for example, in those with genetic conditions such as osteogenesis imperfecta. Furthermore, the occurrence of vertebral compression fractures often requires bisphosphonate treatment regardless of bone density, particularly in patients on chronic glucocorticoid therapy.

Preventing osteoporosis is best managed by paying attention to lifestyle; optimizing nutrition and calcium and vitamin D intake; and managing conditions and limiting the use of medications that reduce bone density.

However, in certain patients, these measures are not enough, and pharmacologic therapy with bone anabolics or antiresorptives may be necessary to improve bone density and reduce fracture risk.

Dr. Misra, of the University of Virginia and UVA Health Children’s Hospital, Charlottesville, disclosed ties with AbbVie, Sanofi, and Ipsen.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Vitamin D Supplements May Be a Double-Edged Sword

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

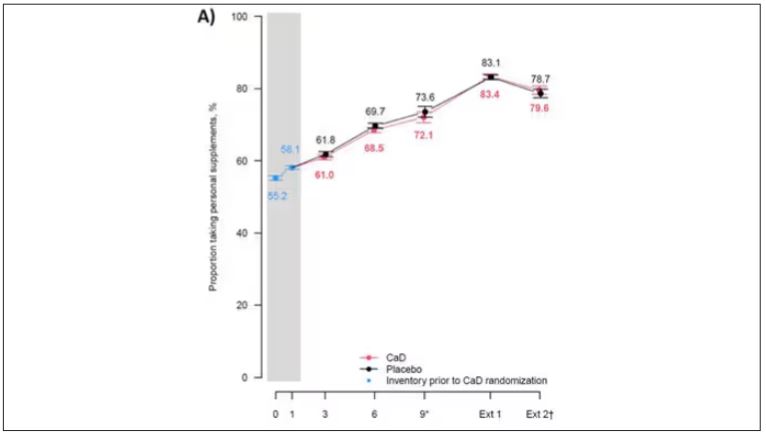

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.

The randomized trial itself only lasted 7 years. What we are seeing in this analysis of 36,282 women is outcomes that happened at any time from randomization to the end of 2023 — around 20 years after the randomization to supplementation stopped. But, the researchers would argue, that’s probably okay. Cancer and heart disease take time to develop; we see lung cancer long after people stop smoking. So a history of consistent vitamin D supplementation may indeed be protective — or harmful.

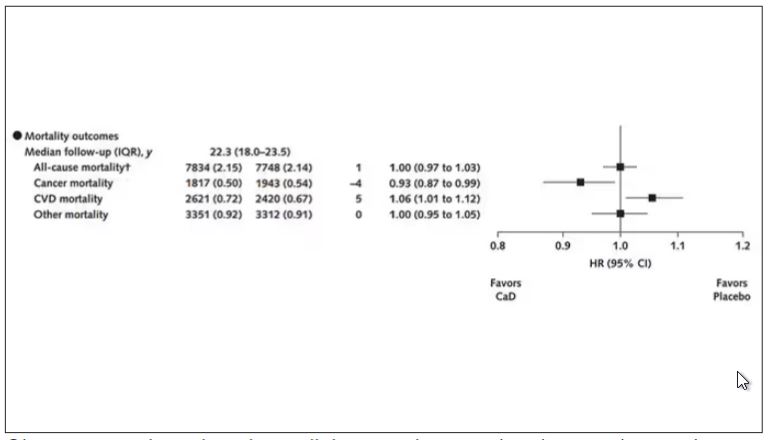

Here are the top-line results. Those randomized to vitamin D and calcium supplementation had a 7% reduction in the rate of death from cancer, driven primarily by a reduction in colorectal cancer. This was statistically significant. Also statistically significant? Those randomized to supplementation had a 6% increase in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease. Put those findings together and what do you get? Stone-cold nothing, in terms of overall mortality.

Okay, you say, but what about all that supplementation that was happening outside of the context of the trial, biasing our results toward the null?

The researchers finally clue us in.

First of all, I’ll tell you that, yes, people who were supplementing outside of the trial had higher baseline vitamin D levels — a median of 54.5 nmol/L vs 32.8 nmol/L. This may be because they were supplementing with vitamin D, but it could also be because people who take supplements tend to do other healthy things — another correlation to add to the great cathedral.

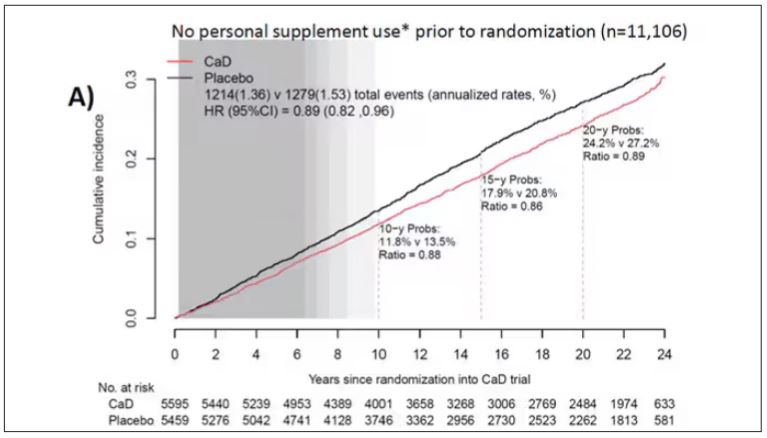

To get a better view of the real effects of randomization, the authors restricted the analysis to just those who did not use outside supplements. If vitamin D supplements help, then these are the people they should help. This group had about a 11% reduction in the incidence of cancer — statistically significant — and a 7% reduction in cancer mortality that did not meet the bar for statistical significance.

There was no increase in cardiovascular disease among this group. But this small effect on cancer was nowhere near enough to significantly reduce the rate of all-cause mortality.

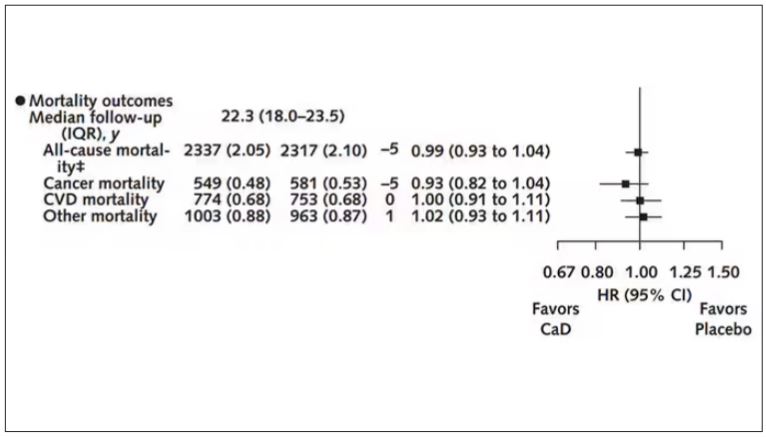

Among those using supplements, vitamin D supplementation didn’t really move the needle on any outcome.

I know what you’re thinking: How many of these women were vitamin D deficient when we got started? These results may simply be telling us that people who have normal vitamin D levels are fine to go without supplementation.

Nearly three fourths of women who were not taking supplements entered the trial with vitamin D levels below the 50 nmol/L cutoff that the authors suggest would qualify for deficiency. Around half of those who used supplements were deficient. And yet, frustratingly, I could not find data on the effect of randomization to supplementation stratified by baseline vitamin D level. I even reached out to Dr Thomson to ask about this. She replied, “We did not stratify on baseline values because the numbers are too small statistically to test this.” Sorry.

In the meantime, I can tell you that for your “average woman,” vitamin D supplementation likely has no effect on mortality. It might modestly reduce the risk for certain cancers while increasing the risk for heart disease (probably through coronary calcification). So, there might be some room for personalization here. Perhaps women with a strong family history of cancer or other risk factors would do better with supplements, and those with a high risk for heart disease would do worse. Seems like a strategy that could be tested in a clinical trial. But maybe we could ask the participants to give up their extracurricular supplement use before they enter the trial. F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

Imagine, if you will, the great Cathedral of Our Lady of Correlation. You walk through the majestic oak doors depicting the link between ice cream sales and shark attacks, past the rose window depicting the cardiovascular benefits of red wine, and down the aisles frescoed in dramatic images showing how Facebook usage is associated with less life satisfaction. And then you reach the altar, the holy of holies where, emblazoned in shimmering pyrite, you see the patron saint of this church: vitamin D.

Yes, if you’ve watched this space, then you know that I have little truck with the wildly popular supplement. In all of clinical research, I believe that there is no molecule with stronger data for correlation and weaker data for causation.

Low serum vitamin D levels have been linked to higher risks for heart disease, cancer, falls, COVID, dementia, C diff, and others. And yet, when we do randomized trials of vitamin D supplementation — the thing that can prove that the low level was causally linked to the outcome of interest — we get negative results.

Trials aren’t perfect, of course, and we’ll talk in a moment about a big one that had some issues. But we are at a point where we need to either be vitamin D apologists, saying, “Forget what those lying RCTs tell you and buy this supplement” — an $800 million-a-year industry, by the way — or conclude that vitamin D levels are a convenient marker of various lifestyle factors that are associated with better outcomes: markers of exercise, getting outside, eating a varied diet.

Or perhaps vitamin D supplements have real effects. It’s just that the beneficial effects are matched by the harmful ones. Stay tuned.

The Women’s Health Initiative remains among the largest randomized trials of vitamin D and calcium supplementation ever conducted — and a major contributor to the negative outcomes of vitamin D trials.

But if you dig into the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this trial, you’ll find that individuals were allowed to continue taking vitamins and supplements while they were in the trial, regardless of their randomization status. In fact, the majority took supplements at baseline, and more took supplements over time.

That means, of course, that people in the placebo group, who were getting sugar pills instead of vitamin D and calcium, may have been taking vitamin D and calcium on the side. That would certainly bias the results of the trial toward the null, which is what the primary analyses showed. To wit, the original analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative trial showed no effect of randomization to vitamin D supplementation on improving cancer or cardiovascular outcomes.

But the Women’s Health Initiative trial started 30 years ago. Today, with the benefit of decades of follow-up, we can re-investigate — and perhaps re-litigate — those findings, courtesy of this study, “Long-Term Effect of Randomization to Calcium and Vitamin D Supplementation on Health in Older Women” appearing in Annals of Internal Medicine.

Dr Cynthia Thomson, of the Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health at the University of Arizona, and colleagues led this updated analysis focused on two findings that had been hinted at, but not statistically confirmed, in other vitamin D studies: a potential for the supplement to reduce the risk for cancer, and a potential for it to increase the risk for heart disease.

The randomized trial itself only lasted 7 years. What we are seeing in this analysis of 36,282 women is outcomes that happened at any time from randomization to the end of 2023 — around 20 years after the randomization to supplementation stopped. But, the researchers would argue, that’s probably okay. Cancer and heart disease take time to develop; we see lung cancer long after people stop smoking. So a history of consistent vitamin D supplementation may indeed be protective — or harmful.

Here are the top-line results. Those randomized to vitamin D and calcium supplementation had a 7% reduction in the rate of death from cancer, driven primarily by a reduction in colorectal cancer. This was statistically significant. Also statistically significant? Those randomized to supplementation had a 6% increase in the rate of death from cardiovascular disease. Put those findings together and what do you get? Stone-cold nothing, in terms of overall mortality.

Okay, you say, but what about all that supplementation that was happening outside of the context of the trial, biasing our results toward the null?

The researchers finally clue us in.

First of all, I’ll tell you that, yes, people who were supplementing outside of the trial had higher baseline vitamin D levels — a median of 54.5 nmol/L vs 32.8 nmol/L. This may be because they were supplementing with vitamin D, but it could also be because people who take supplements tend to do other healthy things — another correlation to add to the great cathedral.