User login

Intravascular Involvement of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer after basal cell carcinoma.1 With an estimated 700,000 cases reported annually in the United States, the incidence of cSCC continues to increase.2 Most patients with cSCC have an excellent prognosis after surgical clearance, with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) being the most successful treatment, followed by excision and electrodesiccation and curettage. A subset of patients with cSCC carry an increased risk of local recurrence, lymph node metastasis, and disease-specific death. A meta-analysis of 36 studies found that statistically significant risk factors for recurrence of cSCC included thickness greater than 2 mm (risk ratio [RR], 9.64; 95% CI, 1.30-1.52), invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat (RR, 7.61; 95% CI, 4.17-13.88), perineural invasion (RR, 4.30; 95% CI, 2.80-6.60), diameter greater than 20 mm (RR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.91-5.45), location on temple (RR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.12-9.15), and poor differentiation (RR, 2.66; 95% CI, 1.72-4.14).3 Additional risk factors for cSCC metastasis included location on the temple, ear, or lip, as well as a history of immunosuppression. Factors for disease-specific death were diameter greater than 20 mm, poor differentiation, location on the ear or lip, invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion.3 Perineural and/or lymphovascular invasion is considered high risk, but despite being linked to negative outcomes, there are no treatment guidelines based on lymphovascular (intravascular) invasion.4 We present a case of intravascular involvement found during MMS and treated with adjuvant radiotherapy after surgery. We share this case with the goal of discussing management in such cases and highlighting the need for improved definitive guidelines for high-risk cSCCs.

Case Report

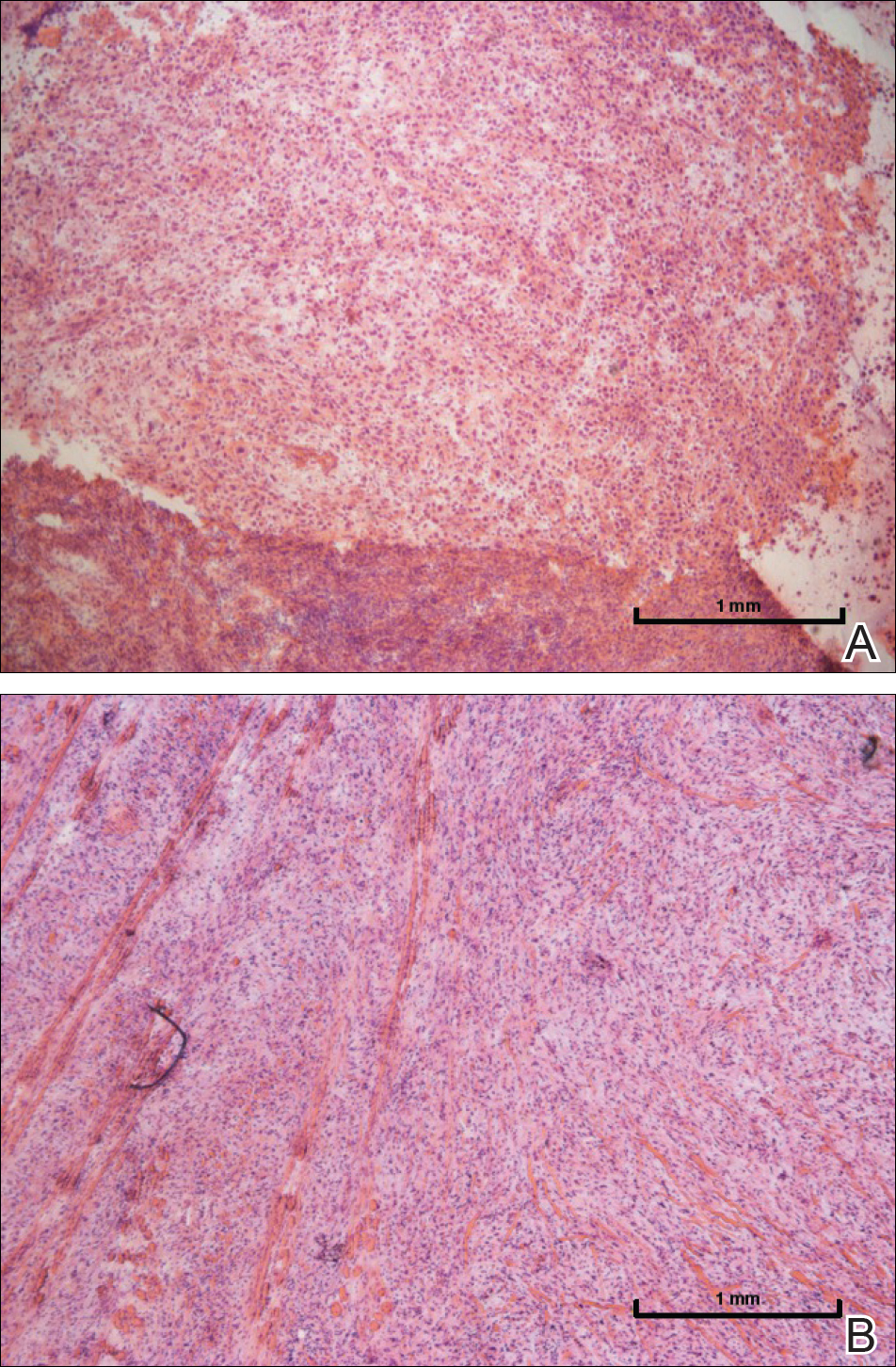

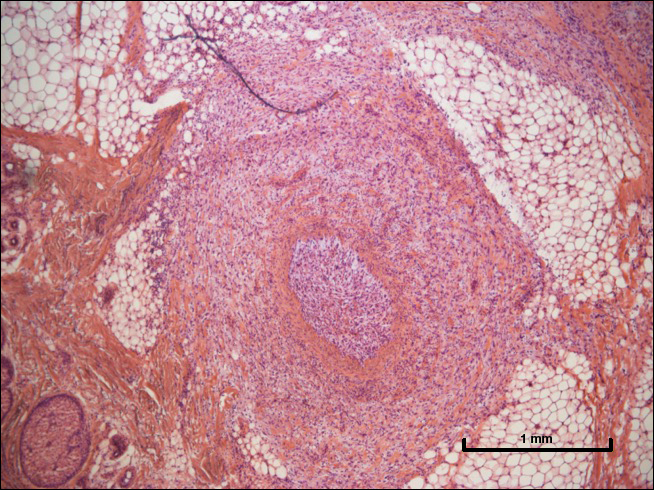

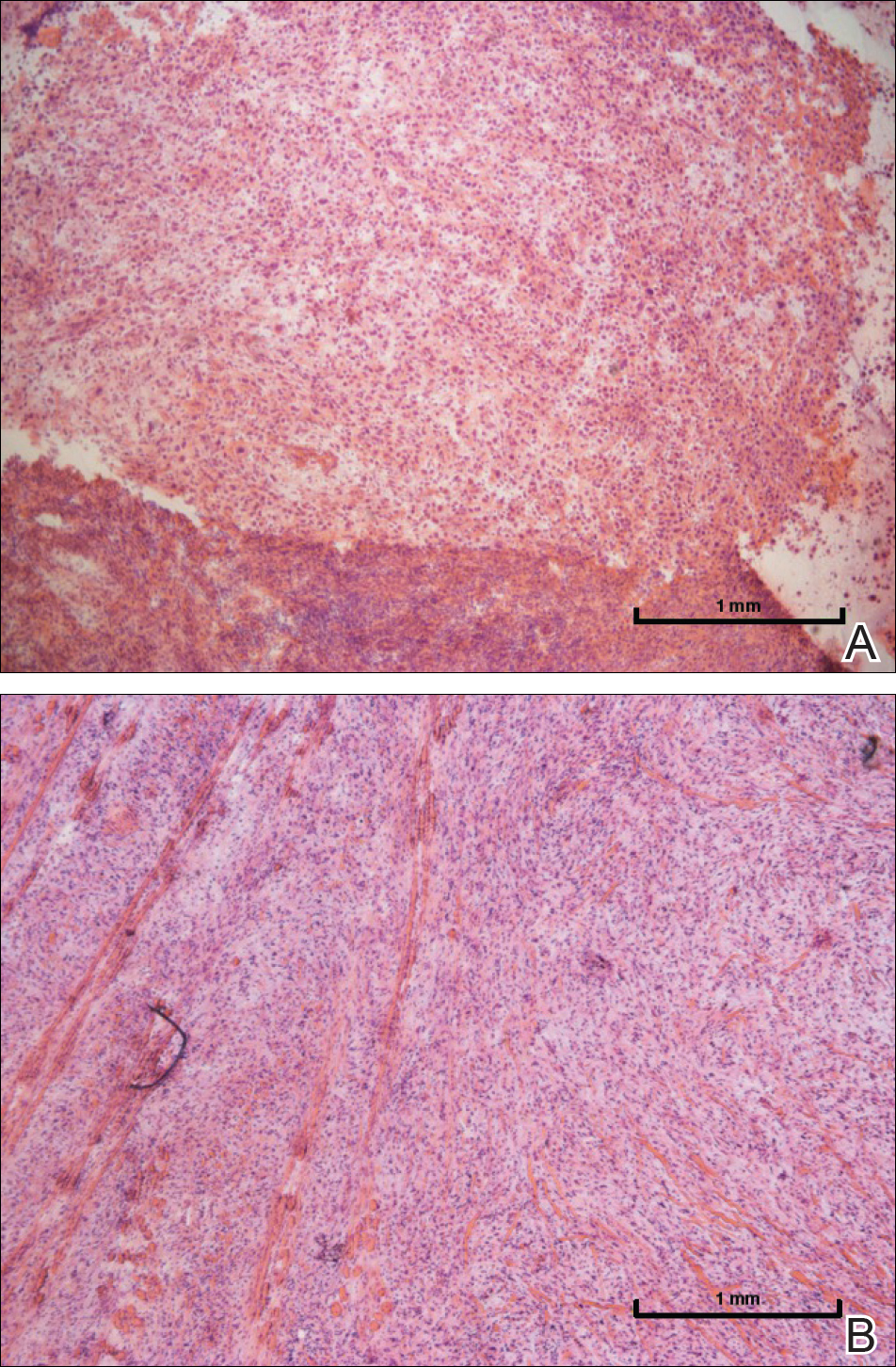

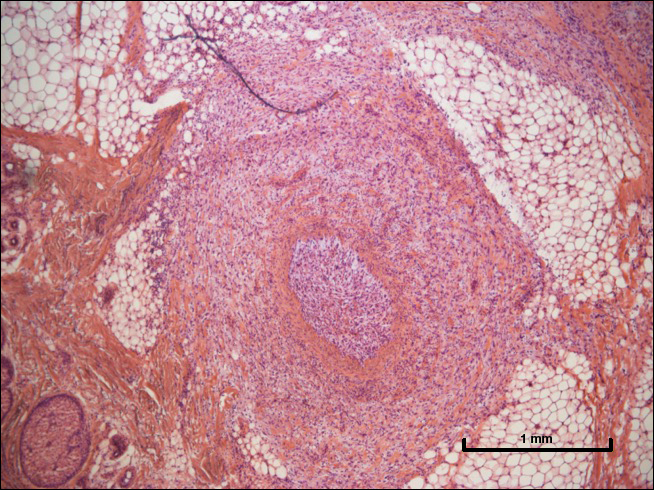

A 72-year-old man presented with a rapidly growing lesion on the left side of the forehead of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was remarkable for B-cell lymphoma, which was currently in remission following chemotherapy 10 years prior. The lesion started as a small, red, dry patch that the patient initially thought was eczema. The site progressively enlarged to a red tumor measuring 2.4×2.0 cm (Figure 1), and the patient presented to the dermatology department for further evaluation. There was no clinical evidence of lymphadenopathy. A skin biopsy confirmed a moderately differentiated cSCC with a positive deep margin (Figure 2). Due to the tumor’s location, histology, size, and poorly defined borders, the patient was referred for treatment with MMS. The lesion was removed in a total of 2 stages and 4 sections. In addition to a proliferation of spindled tumor cells seen during surgery, which was consistent with cSCC, an intravascular component was noted despite clear margins after the surgery (Figure 3). The aggressive histology of intravascular involvement was subsequently confirmed by the academic dermatopathologist at our institution. With the evidence of an intravascular component of this patient’s cSCC, there was concern about further metastatic disease. After discussing the more aggressive histology type and size of the cSCC with the patient, he underwent subsequent computed tomography of the head, neck, and chest. Fortunately, this imaging did not show evidence of metastatic disease; thus, final staging of the cSCC was cT2N0M0. After interdisciplinary discussion and consultation with radiation oncology, the site of the cSCC was treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. The patient received a total of 6600 cGy delivered in 33 fractions of 200 cGy, each using an en face technique and 6 eV over a total treatment course of 48 days.

One year after undergoing MMS and adjuvant radiotherapy, the patient remains free of cSCC recurrence or metastases and still undergoes regular interdisciplinary monitoring. Without clear guidelines on the treatment of patients with intravascular involvement of cSCC, we relied on prior experience with similar cases.

Comment

This case highlights the challenge in managing patients with high-risk cSCC, as the current guidelines provided by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) vary on the inclusion of intravascular involvement of cSCC as high risk and treatment is at the discretion of the provider in such circumstances.5-7 Both the AJCC and the NCCN have defined high-risk factors and staging for cSCC. The AJCC 8th edition (AJCC-8) revised guidelines include several high-risk factors of cSCC, including tumor diameter of 4 cm or larger leading to upstaging of a tumor from T2 to T3, invasion into or beyond the level of the subcutaneous tissue, depth of invasion greater than 6 mm, and large-caliber perineural invasion, and removed poorly differentiated histology from the AJCC-8 guidelines compared to the AJCC-7 guidelines. According to the AJCC-8 guidelines, location on the ear or lip, desmoplastic or spindle cell features, lymphovascular invasion, and immunosuppression do not affect tumor staging. The AJCC’s criteria for its TNM staging system strictly focus on features of the primary tumor and do not include clinical risk factors such as recurrence or immunosuppression. In contrast, the NCCN does include lymphovascular invasion as a high-risk factor of cSCC.

Intravascular invasion plays a considerable role in patient survival in certain cancers (eg, breast, gastric, prostate). In cutaneous malignancies, such as melanoma and SCC, metastasis more commonly occurs via lymphatic spread. When present, vascular invasion typically coexists with lymphatic involvement. The presence of microscopic lymphovascular invasion in cSCCs has not been definitively proven to increase the risk of metastases.8 However, multivariate analysis has shown that lymphovascular invasion independently predicts nodal metastasis and disease-specific death.9 As such, there are no guidelines on sentinel lymph node biopsy or adjuvant therapy in the setting of lymphovascular involvement of cSCCs. A survey-based study of 117 Mohs surgeons found a lack of consistency in their approaches to evaluation and management of high-risk SCCs. Most respondents noted perineural invasion and in-transit metastasis as the main findings that would lead to radiologic nodal staging, sentinel lymph node biopsy, or adjuvant radiotherapy, but they highlighted the lack of evidence-based treatment guidelines.4 High-risk cSCC can be treated via MMS or conventional surgery with safe excision margins. Adjuvant radiotherapy can reduce tumor recurrence and improve survival and therefore should be considered in cases of advanced or high-risk cSCCs, such as in our case.

The lack of consensus over the definition of high-risk cSCCs, a lack of high-quality therapeutic studies, and the absence of a prognostic model that integrates multiple risk factors all have made the prediction of outcomes and the formation of definitive management of cSCCs challenging. Multidisciplinary teams and vigilant monitoring are crucial in the successful management of high-risk cSCC, but further studies and reports are needed to develop definitive treatment algorithms.

- Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:957-966.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma recurrence, metastasis, and disease-specific death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:419-428.

- Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Hess SD, Katz KA, et al. Uncertainty in the perioperative management of high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma among Mohs surgeons. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1225-1231.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Amin MD, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Squamous Cell Skin Cancer (Version 2.2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/squamous.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2018.

- Lonie S, Niumsawatt V, Castley A. A prognostic dilemma of basal cell carcinoma with intravascular invasion. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e1046.

- Carter JB, Johnson MM, Chua TL, et al. Outcomes of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: an 11-year cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:35-41.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer after basal cell carcinoma.1 With an estimated 700,000 cases reported annually in the United States, the incidence of cSCC continues to increase.2 Most patients with cSCC have an excellent prognosis after surgical clearance, with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) being the most successful treatment, followed by excision and electrodesiccation and curettage. A subset of patients with cSCC carry an increased risk of local recurrence, lymph node metastasis, and disease-specific death. A meta-analysis of 36 studies found that statistically significant risk factors for recurrence of cSCC included thickness greater than 2 mm (risk ratio [RR], 9.64; 95% CI, 1.30-1.52), invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat (RR, 7.61; 95% CI, 4.17-13.88), perineural invasion (RR, 4.30; 95% CI, 2.80-6.60), diameter greater than 20 mm (RR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.91-5.45), location on temple (RR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.12-9.15), and poor differentiation (RR, 2.66; 95% CI, 1.72-4.14).3 Additional risk factors for cSCC metastasis included location on the temple, ear, or lip, as well as a history of immunosuppression. Factors for disease-specific death were diameter greater than 20 mm, poor differentiation, location on the ear or lip, invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion.3 Perineural and/or lymphovascular invasion is considered high risk, but despite being linked to negative outcomes, there are no treatment guidelines based on lymphovascular (intravascular) invasion.4 We present a case of intravascular involvement found during MMS and treated with adjuvant radiotherapy after surgery. We share this case with the goal of discussing management in such cases and highlighting the need for improved definitive guidelines for high-risk cSCCs.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with a rapidly growing lesion on the left side of the forehead of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was remarkable for B-cell lymphoma, which was currently in remission following chemotherapy 10 years prior. The lesion started as a small, red, dry patch that the patient initially thought was eczema. The site progressively enlarged to a red tumor measuring 2.4×2.0 cm (Figure 1), and the patient presented to the dermatology department for further evaluation. There was no clinical evidence of lymphadenopathy. A skin biopsy confirmed a moderately differentiated cSCC with a positive deep margin (Figure 2). Due to the tumor’s location, histology, size, and poorly defined borders, the patient was referred for treatment with MMS. The lesion was removed in a total of 2 stages and 4 sections. In addition to a proliferation of spindled tumor cells seen during surgery, which was consistent with cSCC, an intravascular component was noted despite clear margins after the surgery (Figure 3). The aggressive histology of intravascular involvement was subsequently confirmed by the academic dermatopathologist at our institution. With the evidence of an intravascular component of this patient’s cSCC, there was concern about further metastatic disease. After discussing the more aggressive histology type and size of the cSCC with the patient, he underwent subsequent computed tomography of the head, neck, and chest. Fortunately, this imaging did not show evidence of metastatic disease; thus, final staging of the cSCC was cT2N0M0. After interdisciplinary discussion and consultation with radiation oncology, the site of the cSCC was treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. The patient received a total of 6600 cGy delivered in 33 fractions of 200 cGy, each using an en face technique and 6 eV over a total treatment course of 48 days.

One year after undergoing MMS and adjuvant radiotherapy, the patient remains free of cSCC recurrence or metastases and still undergoes regular interdisciplinary monitoring. Without clear guidelines on the treatment of patients with intravascular involvement of cSCC, we relied on prior experience with similar cases.

Comment

This case highlights the challenge in managing patients with high-risk cSCC, as the current guidelines provided by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) vary on the inclusion of intravascular involvement of cSCC as high risk and treatment is at the discretion of the provider in such circumstances.5-7 Both the AJCC and the NCCN have defined high-risk factors and staging for cSCC. The AJCC 8th edition (AJCC-8) revised guidelines include several high-risk factors of cSCC, including tumor diameter of 4 cm or larger leading to upstaging of a tumor from T2 to T3, invasion into or beyond the level of the subcutaneous tissue, depth of invasion greater than 6 mm, and large-caliber perineural invasion, and removed poorly differentiated histology from the AJCC-8 guidelines compared to the AJCC-7 guidelines. According to the AJCC-8 guidelines, location on the ear or lip, desmoplastic or spindle cell features, lymphovascular invasion, and immunosuppression do not affect tumor staging. The AJCC’s criteria for its TNM staging system strictly focus on features of the primary tumor and do not include clinical risk factors such as recurrence or immunosuppression. In contrast, the NCCN does include lymphovascular invasion as a high-risk factor of cSCC.

Intravascular invasion plays a considerable role in patient survival in certain cancers (eg, breast, gastric, prostate). In cutaneous malignancies, such as melanoma and SCC, metastasis more commonly occurs via lymphatic spread. When present, vascular invasion typically coexists with lymphatic involvement. The presence of microscopic lymphovascular invasion in cSCCs has not been definitively proven to increase the risk of metastases.8 However, multivariate analysis has shown that lymphovascular invasion independently predicts nodal metastasis and disease-specific death.9 As such, there are no guidelines on sentinel lymph node biopsy or adjuvant therapy in the setting of lymphovascular involvement of cSCCs. A survey-based study of 117 Mohs surgeons found a lack of consistency in their approaches to evaluation and management of high-risk SCCs. Most respondents noted perineural invasion and in-transit metastasis as the main findings that would lead to radiologic nodal staging, sentinel lymph node biopsy, or adjuvant radiotherapy, but they highlighted the lack of evidence-based treatment guidelines.4 High-risk cSCC can be treated via MMS or conventional surgery with safe excision margins. Adjuvant radiotherapy can reduce tumor recurrence and improve survival and therefore should be considered in cases of advanced or high-risk cSCCs, such as in our case.

The lack of consensus over the definition of high-risk cSCCs, a lack of high-quality therapeutic studies, and the absence of a prognostic model that integrates multiple risk factors all have made the prediction of outcomes and the formation of definitive management of cSCCs challenging. Multidisciplinary teams and vigilant monitoring are crucial in the successful management of high-risk cSCC, but further studies and reports are needed to develop definitive treatment algorithms.

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (cSCC) is the second most common form of skin cancer after basal cell carcinoma.1 With an estimated 700,000 cases reported annually in the United States, the incidence of cSCC continues to increase.2 Most patients with cSCC have an excellent prognosis after surgical clearance, with Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) being the most successful treatment, followed by excision and electrodesiccation and curettage. A subset of patients with cSCC carry an increased risk of local recurrence, lymph node metastasis, and disease-specific death. A meta-analysis of 36 studies found that statistically significant risk factors for recurrence of cSCC included thickness greater than 2 mm (risk ratio [RR], 9.64; 95% CI, 1.30-1.52), invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat (RR, 7.61; 95% CI, 4.17-13.88), perineural invasion (RR, 4.30; 95% CI, 2.80-6.60), diameter greater than 20 mm (RR, 3.22; 95% CI, 1.91-5.45), location on temple (RR, 3.20; 95% CI, 1.12-9.15), and poor differentiation (RR, 2.66; 95% CI, 1.72-4.14).3 Additional risk factors for cSCC metastasis included location on the temple, ear, or lip, as well as a history of immunosuppression. Factors for disease-specific death were diameter greater than 20 mm, poor differentiation, location on the ear or lip, invasion beyond the subcutaneous fat, and perineural invasion.3 Perineural and/or lymphovascular invasion is considered high risk, but despite being linked to negative outcomes, there are no treatment guidelines based on lymphovascular (intravascular) invasion.4 We present a case of intravascular involvement found during MMS and treated with adjuvant radiotherapy after surgery. We share this case with the goal of discussing management in such cases and highlighting the need for improved definitive guidelines for high-risk cSCCs.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with a rapidly growing lesion on the left side of the forehead of 1 year’s duration. His medical history was remarkable for B-cell lymphoma, which was currently in remission following chemotherapy 10 years prior. The lesion started as a small, red, dry patch that the patient initially thought was eczema. The site progressively enlarged to a red tumor measuring 2.4×2.0 cm (Figure 1), and the patient presented to the dermatology department for further evaluation. There was no clinical evidence of lymphadenopathy. A skin biopsy confirmed a moderately differentiated cSCC with a positive deep margin (Figure 2). Due to the tumor’s location, histology, size, and poorly defined borders, the patient was referred for treatment with MMS. The lesion was removed in a total of 2 stages and 4 sections. In addition to a proliferation of spindled tumor cells seen during surgery, which was consistent with cSCC, an intravascular component was noted despite clear margins after the surgery (Figure 3). The aggressive histology of intravascular involvement was subsequently confirmed by the academic dermatopathologist at our institution. With the evidence of an intravascular component of this patient’s cSCC, there was concern about further metastatic disease. After discussing the more aggressive histology type and size of the cSCC with the patient, he underwent subsequent computed tomography of the head, neck, and chest. Fortunately, this imaging did not show evidence of metastatic disease; thus, final staging of the cSCC was cT2N0M0. After interdisciplinary discussion and consultation with radiation oncology, the site of the cSCC was treated with adjuvant radiotherapy. The patient received a total of 6600 cGy delivered in 33 fractions of 200 cGy, each using an en face technique and 6 eV over a total treatment course of 48 days.

One year after undergoing MMS and adjuvant radiotherapy, the patient remains free of cSCC recurrence or metastases and still undergoes regular interdisciplinary monitoring. Without clear guidelines on the treatment of patients with intravascular involvement of cSCC, we relied on prior experience with similar cases.

Comment

This case highlights the challenge in managing patients with high-risk cSCC, as the current guidelines provided by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) vary on the inclusion of intravascular involvement of cSCC as high risk and treatment is at the discretion of the provider in such circumstances.5-7 Both the AJCC and the NCCN have defined high-risk factors and staging for cSCC. The AJCC 8th edition (AJCC-8) revised guidelines include several high-risk factors of cSCC, including tumor diameter of 4 cm or larger leading to upstaging of a tumor from T2 to T3, invasion into or beyond the level of the subcutaneous tissue, depth of invasion greater than 6 mm, and large-caliber perineural invasion, and removed poorly differentiated histology from the AJCC-8 guidelines compared to the AJCC-7 guidelines. According to the AJCC-8 guidelines, location on the ear or lip, desmoplastic or spindle cell features, lymphovascular invasion, and immunosuppression do not affect tumor staging. The AJCC’s criteria for its TNM staging system strictly focus on features of the primary tumor and do not include clinical risk factors such as recurrence or immunosuppression. In contrast, the NCCN does include lymphovascular invasion as a high-risk factor of cSCC.

Intravascular invasion plays a considerable role in patient survival in certain cancers (eg, breast, gastric, prostate). In cutaneous malignancies, such as melanoma and SCC, metastasis more commonly occurs via lymphatic spread. When present, vascular invasion typically coexists with lymphatic involvement. The presence of microscopic lymphovascular invasion in cSCCs has not been definitively proven to increase the risk of metastases.8 However, multivariate analysis has shown that lymphovascular invasion independently predicts nodal metastasis and disease-specific death.9 As such, there are no guidelines on sentinel lymph node biopsy or adjuvant therapy in the setting of lymphovascular involvement of cSCCs. A survey-based study of 117 Mohs surgeons found a lack of consistency in their approaches to evaluation and management of high-risk SCCs. Most respondents noted perineural invasion and in-transit metastasis as the main findings that would lead to radiologic nodal staging, sentinel lymph node biopsy, or adjuvant radiotherapy, but they highlighted the lack of evidence-based treatment guidelines.4 High-risk cSCC can be treated via MMS or conventional surgery with safe excision margins. Adjuvant radiotherapy can reduce tumor recurrence and improve survival and therefore should be considered in cases of advanced or high-risk cSCCs, such as in our case.

The lack of consensus over the definition of high-risk cSCCs, a lack of high-quality therapeutic studies, and the absence of a prognostic model that integrates multiple risk factors all have made the prediction of outcomes and the formation of definitive management of cSCCs challenging. Multidisciplinary teams and vigilant monitoring are crucial in the successful management of high-risk cSCC, but further studies and reports are needed to develop definitive treatment algorithms.

- Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:957-966.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma recurrence, metastasis, and disease-specific death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:419-428.

- Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Hess SD, Katz KA, et al. Uncertainty in the perioperative management of high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma among Mohs surgeons. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1225-1231.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Amin MD, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Squamous Cell Skin Cancer (Version 2.2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/squamous.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2018.

- Lonie S, Niumsawatt V, Castley A. A prognostic dilemma of basal cell carcinoma with intravascular invasion. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e1046.

- Carter JB, Johnson MM, Chua TL, et al. Outcomes of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: an 11-year cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:35-41.

- Karia PS, Han J, Schmults CD. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:957-966.

- Rogers HW, Weinstock MA, Harris AR, et al. Incidence estimate of nonmelanoma skin cancer in the United States, 2006. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:283-287.

- Thompson AK, Kelley BF, Prokop LJ, et al. Risk factors for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma recurrence, metastasis, and disease-specific death: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:419-428.

- Jambusaria-Pahlajani A, Hess SD, Katz KA, et al. Uncertainty in the perioperative management of high-risk cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma among Mohs surgeons. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:1225-1231.

- Motaparthi K, Kapil JP, Velazquez EF. Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: review of the eighth edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Guidelines, prognostic factors, and histopathologic variants. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:171-194.

- Amin MD, Edge SB, Greene FL, et al, eds. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 8th ed. New York, NY: Springer; 2017.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Squamous Cell Skin Cancer (Version 2.2018). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/squamous.pdf. Accessed June 27, 2018.

- Lonie S, Niumsawatt V, Castley A. A prognostic dilemma of basal cell carcinoma with intravascular invasion. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:e1046.

- Carter JB, Johnson MM, Chua TL, et al. Outcomes of primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: an 11-year cohort study. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:35-41.

Resident Pearl

- Intravascular (also referred to as lymphovascular when involving vessels and/or lymphatics) invasion of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma can be considered a high-risk factor that may warrant adjuvant therapy.

Cutavirus shows no association with primary cutaneous lymphoma

The parvovirus known as cutavirus appears unlikely to play a pathogenic role in primary cutaneous B- and T-cell lymphoma, based on data from 189 biopsies.

Although researchers have long suspected viruses of a role in primary cutaneous lymphomas, “all of the so-far-suspected viruses including retroviruses, herpesviruses, and polyomaviruses have failed to reveal a consistent association with both cutaneous B-cell lymphoma [CBCL] and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [CTCL],” wrote Alexander Kreuter, MD, of the department of dermatology, venereology, and allergology at Helios St. Elisabeth Hospital Oberhausen, Germany, and his colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology, the researchers analyzed 189 paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens from 130 adults with CBCL or CTCL.

Overall, cutavirus DNA was identified in 6 (3.2%) of the 189 lymphoma biopsies and in 6 (4.6%) of 130 patients. Cutavirus was identified only in male patients with mycosis fungoides, and no cutavirus was identified in patients or biopsies without mycosis fungoides, the researchers noted. Viral DNA loads in the cutavirus-positive biopsies ranged from 1.3 to 85.0 cutavirus DNA copies per beta globin gene copy.

The findings were limited by several factors, such as the lack of biopsy samples for some lymphoma subtypes and the availability of a single specimen from most patients, the researchers noted. However, the analysis of a large number of samples suggested that cutavirus is not associated with the development of most primary cutaneous lymphomas, they said.

The study was funded by the German National Reference Center for Papilloma- and Polyomaviruses. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kreuter A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jun 27. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1628.

The parvovirus known as cutavirus appears unlikely to play a pathogenic role in primary cutaneous B- and T-cell lymphoma, based on data from 189 biopsies.

Although researchers have long suspected viruses of a role in primary cutaneous lymphomas, “all of the so-far-suspected viruses including retroviruses, herpesviruses, and polyomaviruses have failed to reveal a consistent association with both cutaneous B-cell lymphoma [CBCL] and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [CTCL],” wrote Alexander Kreuter, MD, of the department of dermatology, venereology, and allergology at Helios St. Elisabeth Hospital Oberhausen, Germany, and his colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology, the researchers analyzed 189 paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens from 130 adults with CBCL or CTCL.

Overall, cutavirus DNA was identified in 6 (3.2%) of the 189 lymphoma biopsies and in 6 (4.6%) of 130 patients. Cutavirus was identified only in male patients with mycosis fungoides, and no cutavirus was identified in patients or biopsies without mycosis fungoides, the researchers noted. Viral DNA loads in the cutavirus-positive biopsies ranged from 1.3 to 85.0 cutavirus DNA copies per beta globin gene copy.

The findings were limited by several factors, such as the lack of biopsy samples for some lymphoma subtypes and the availability of a single specimen from most patients, the researchers noted. However, the analysis of a large number of samples suggested that cutavirus is not associated with the development of most primary cutaneous lymphomas, they said.

The study was funded by the German National Reference Center for Papilloma- and Polyomaviruses. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kreuter A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jun 27. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1628.

The parvovirus known as cutavirus appears unlikely to play a pathogenic role in primary cutaneous B- and T-cell lymphoma, based on data from 189 biopsies.

Although researchers have long suspected viruses of a role in primary cutaneous lymphomas, “all of the so-far-suspected viruses including retroviruses, herpesviruses, and polyomaviruses have failed to reveal a consistent association with both cutaneous B-cell lymphoma [CBCL] and cutaneous T-cell lymphoma [CTCL],” wrote Alexander Kreuter, MD, of the department of dermatology, venereology, and allergology at Helios St. Elisabeth Hospital Oberhausen, Germany, and his colleagues.

In a research letter published in JAMA Dermatology, the researchers analyzed 189 paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens from 130 adults with CBCL or CTCL.

Overall, cutavirus DNA was identified in 6 (3.2%) of the 189 lymphoma biopsies and in 6 (4.6%) of 130 patients. Cutavirus was identified only in male patients with mycosis fungoides, and no cutavirus was identified in patients or biopsies without mycosis fungoides, the researchers noted. Viral DNA loads in the cutavirus-positive biopsies ranged from 1.3 to 85.0 cutavirus DNA copies per beta globin gene copy.

The findings were limited by several factors, such as the lack of biopsy samples for some lymphoma subtypes and the availability of a single specimen from most patients, the researchers noted. However, the analysis of a large number of samples suggested that cutavirus is not associated with the development of most primary cutaneous lymphomas, they said.

The study was funded by the German National Reference Center for Papilloma- and Polyomaviruses. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Kreuter A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jun 27. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1628.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Cutavirus may not have a primary role in cutaneous lymphomas.

Major finding: Cutavirus was identified in 6 (3.2%) of 189 lymphoma biopsies.

Study details: The data come from 130 patients with cutaneous B-cell lymphoma or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and a total of 189 biopsy specimens.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the German National Reference Center for Papilloma- and Polyomaviruses. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Source: Kreuter A et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Jun 27. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2018.1628.

Extramammary Paget Disease: Making the Correct Diagnosis

Registry data provide evidence that Mohs surgery remains underutilized

CHICAGO – Analysis of U.S. national cancer registry data shows that, contrary to expectation, the , Sean Condon, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Ditto for the use of Mohs in patients with the rare cutaneous malignancies for which published evidence clearly demonstrates Mohs outperforms wide local excision, which is employed seven times more frequently than Mohs in such situations.

“Mohs utilization did not increase after the Affordable Care Act [ACA], despite new health insurance coverage for 20 million previously uninsured adults,” Dr. Condon said. “Surprisingly, after the ACA we actually saw a decrease in Mohs use for melanoma in situ.”

Indeed, his retrospective study of more than 25,000 patients in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registries showed that the proportion of patients with melanoma in situ treated with Mohs declined from 13.9% during 2008-2009 – prior to ACA implementation – to 12.3% in 2011-2013, after the ACA took effect. That’s a statistically significant 13% drop, even though numerous published studies have shown outcomes in melanoma in situ are better with Mohs, said the dermatologist, who conducted the study while completing a Mohs surgery fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic. He is now in private practice in Thousand Oaks, Calif.

His analysis included 19,013 patients treated in 2008-2014 for melanoma in situ and 6,309 others treated for rare cutaneous malignancies deemed appropriate for Mohs according to the criteria formally developed jointly by the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Mohs Surgery, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Oct;67[4]:531-50). These rare malignancies include adnexal carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma, extramammary Paget disease, sebaceous adenocarcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma.

“These rare cutaneous malignancies were historically treated with wide local excision. However, numerous studies have lately shown that lower recurrence rates were found with Mohs compared with wide local excision,” Dr. Condon noted.

Nonetheless, the proportion of the rare cutaneous malignancies treated using Mohs was unaffected by implementation of the ACA. Nor was it influenced one way or the other by publication of the joint Mohs appropriate use criteria in 2012: The Mohs-treated proportion of such cases was 15.25% in 2010-2011 and 14.6% in 2013-2014.

Similarly, even though the appropriate use criteria identified melanoma in situ as Mohs appropriate, the proportion of those malignancies treated via Mohs was the same before and after the 2012 release of the criteria.

“It’s commonly thought that Mohs is overused. However, our study and our data clearly identify that Mohs is being underutilized for melanoma in situ and for rare cutaneous malignancies. This represents a knowledge gap for other specialties regarding best-practice therapy,” Dr. Condon said.

He and his coinvestigators searched for socioeconomic predictors of Mohs utilization by matching the nationally representative SEER data with U.S. census data. They examined the impact of three metrics: insurance status, income, and poverty. They found that low-income patients and those in the highest quartile of poverty were significantly less likely to have Mohs surgery for their melanoma in situ and rare cutaneous malignancies throughout the study years. Lack of health insurance had no impact on Mohs utilization for melanoma in situ but was independently associated with decreased likelihood of Mohs for the rare cutaneous malignancies. White patients were 2-fold to 2.4-fold more likely to have Mohs surgery for their rare cutaneous malignancies than were black patients.

“One can conclude that Mohs micrographic surgery may be skewed toward more affluent patients, and lower socioeconomic status areas have less Mohs access. So our data from this study support a role for targeted education and improved patient access to Mohs,” Dr. Condon said.

He noted that because the SEER registries don’t track squamous or basal cell carcinomas, it’s unknown whether Mohs is also underutilized for the higher-risk forms of these most common of all skin cancers.

Dr. Condon reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – Analysis of U.S. national cancer registry data shows that, contrary to expectation, the , Sean Condon, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Ditto for the use of Mohs in patients with the rare cutaneous malignancies for which published evidence clearly demonstrates Mohs outperforms wide local excision, which is employed seven times more frequently than Mohs in such situations.

“Mohs utilization did not increase after the Affordable Care Act [ACA], despite new health insurance coverage for 20 million previously uninsured adults,” Dr. Condon said. “Surprisingly, after the ACA we actually saw a decrease in Mohs use for melanoma in situ.”

Indeed, his retrospective study of more than 25,000 patients in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registries showed that the proportion of patients with melanoma in situ treated with Mohs declined from 13.9% during 2008-2009 – prior to ACA implementation – to 12.3% in 2011-2013, after the ACA took effect. That’s a statistically significant 13% drop, even though numerous published studies have shown outcomes in melanoma in situ are better with Mohs, said the dermatologist, who conducted the study while completing a Mohs surgery fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic. He is now in private practice in Thousand Oaks, Calif.

His analysis included 19,013 patients treated in 2008-2014 for melanoma in situ and 6,309 others treated for rare cutaneous malignancies deemed appropriate for Mohs according to the criteria formally developed jointly by the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Mohs Surgery, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Oct;67[4]:531-50). These rare malignancies include adnexal carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma, extramammary Paget disease, sebaceous adenocarcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma.

“These rare cutaneous malignancies were historically treated with wide local excision. However, numerous studies have lately shown that lower recurrence rates were found with Mohs compared with wide local excision,” Dr. Condon noted.

Nonetheless, the proportion of the rare cutaneous malignancies treated using Mohs was unaffected by implementation of the ACA. Nor was it influenced one way or the other by publication of the joint Mohs appropriate use criteria in 2012: The Mohs-treated proportion of such cases was 15.25% in 2010-2011 and 14.6% in 2013-2014.

Similarly, even though the appropriate use criteria identified melanoma in situ as Mohs appropriate, the proportion of those malignancies treated via Mohs was the same before and after the 2012 release of the criteria.

“It’s commonly thought that Mohs is overused. However, our study and our data clearly identify that Mohs is being underutilized for melanoma in situ and for rare cutaneous malignancies. This represents a knowledge gap for other specialties regarding best-practice therapy,” Dr. Condon said.

He and his coinvestigators searched for socioeconomic predictors of Mohs utilization by matching the nationally representative SEER data with U.S. census data. They examined the impact of three metrics: insurance status, income, and poverty. They found that low-income patients and those in the highest quartile of poverty were significantly less likely to have Mohs surgery for their melanoma in situ and rare cutaneous malignancies throughout the study years. Lack of health insurance had no impact on Mohs utilization for melanoma in situ but was independently associated with decreased likelihood of Mohs for the rare cutaneous malignancies. White patients were 2-fold to 2.4-fold more likely to have Mohs surgery for their rare cutaneous malignancies than were black patients.

“One can conclude that Mohs micrographic surgery may be skewed toward more affluent patients, and lower socioeconomic status areas have less Mohs access. So our data from this study support a role for targeted education and improved patient access to Mohs,” Dr. Condon said.

He noted that because the SEER registries don’t track squamous or basal cell carcinomas, it’s unknown whether Mohs is also underutilized for the higher-risk forms of these most common of all skin cancers.

Dr. Condon reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

CHICAGO – Analysis of U.S. national cancer registry data shows that, contrary to expectation, the , Sean Condon, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

Ditto for the use of Mohs in patients with the rare cutaneous malignancies for which published evidence clearly demonstrates Mohs outperforms wide local excision, which is employed seven times more frequently than Mohs in such situations.

“Mohs utilization did not increase after the Affordable Care Act [ACA], despite new health insurance coverage for 20 million previously uninsured adults,” Dr. Condon said. “Surprisingly, after the ACA we actually saw a decrease in Mohs use for melanoma in situ.”

Indeed, his retrospective study of more than 25,000 patients in the National Cancer Institute’s SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results) registries showed that the proportion of patients with melanoma in situ treated with Mohs declined from 13.9% during 2008-2009 – prior to ACA implementation – to 12.3% in 2011-2013, after the ACA took effect. That’s a statistically significant 13% drop, even though numerous published studies have shown outcomes in melanoma in situ are better with Mohs, said the dermatologist, who conducted the study while completing a Mohs surgery fellowship at the Cleveland Clinic. He is now in private practice in Thousand Oaks, Calif.

His analysis included 19,013 patients treated in 2008-2014 for melanoma in situ and 6,309 others treated for rare cutaneous malignancies deemed appropriate for Mohs according to the criteria formally developed jointly by the American Academy of Dermatology, the American College of Mohs Surgery, the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery Association, and the American Society for Mohs Surgery (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Oct;67[4]:531-50). These rare malignancies include adnexal carcinoma, Merkel cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma, extramammary Paget disease, sebaceous adenocarcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma.

“These rare cutaneous malignancies were historically treated with wide local excision. However, numerous studies have lately shown that lower recurrence rates were found with Mohs compared with wide local excision,” Dr. Condon noted.

Nonetheless, the proportion of the rare cutaneous malignancies treated using Mohs was unaffected by implementation of the ACA. Nor was it influenced one way or the other by publication of the joint Mohs appropriate use criteria in 2012: The Mohs-treated proportion of such cases was 15.25% in 2010-2011 and 14.6% in 2013-2014.

Similarly, even though the appropriate use criteria identified melanoma in situ as Mohs appropriate, the proportion of those malignancies treated via Mohs was the same before and after the 2012 release of the criteria.

“It’s commonly thought that Mohs is overused. However, our study and our data clearly identify that Mohs is being underutilized for melanoma in situ and for rare cutaneous malignancies. This represents a knowledge gap for other specialties regarding best-practice therapy,” Dr. Condon said.

He and his coinvestigators searched for socioeconomic predictors of Mohs utilization by matching the nationally representative SEER data with U.S. census data. They examined the impact of three metrics: insurance status, income, and poverty. They found that low-income patients and those in the highest quartile of poverty were significantly less likely to have Mohs surgery for their melanoma in situ and rare cutaneous malignancies throughout the study years. Lack of health insurance had no impact on Mohs utilization for melanoma in situ but was independently associated with decreased likelihood of Mohs for the rare cutaneous malignancies. White patients were 2-fold to 2.4-fold more likely to have Mohs surgery for their rare cutaneous malignancies than were black patients.

“One can conclude that Mohs micrographic surgery may be skewed toward more affluent patients, and lower socioeconomic status areas have less Mohs access. So our data from this study support a role for targeted education and improved patient access to Mohs,” Dr. Condon said.

He noted that because the SEER registries don’t track squamous or basal cell carcinomas, it’s unknown whether Mohs is also underutilized for the higher-risk forms of these most common of all skin cancers.

Dr. Condon reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

REPORTING FROM THE ACMS 50TH ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Mohs micrographic surgery remains seriously underutilized for the skin cancers for which it is most advantageous.

Major finding: The use of Mohs micrographic surgery to treat melanoma in situ declined significantly after passage of the Affordable Care Act.

Study details: This was a retrospective study of national SEER data on more than 25,000 patients treated for melanoma in situ or rare cutaneous malignancies during 2008-2014.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding his study, conducted free of commercial support.

Study pinpoints skin cancer risk factors after hematopoietic cell transplant

CHICAGO – The 10-year incidence rates for both squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising after hematopoietic cell transplantation are impressively high at 17%-plus for each, but the malignancies occur on two very different timelines, according to Jeffrey F. Scott, MD, a fellow in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Most of the squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in a large multicenter retrospective study developed within the first 5 years following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), while the majority of the basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) occurred after that point, Dr. Scott reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

He presented the results of the study, which included 876 HCT recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years. The study objective was to pin down the risk factors for skin cancer after HCT, especially the patient-specific ones. This has become a pressing issue because the use of HCT is steadily growing, and the 5-year survival rate now exceeds 50%.

The transplant-specific risk factors have previously been fairly well described by others. They include the donor source, type of disease, the conditioning regimen, whether whole body irradiation was used, immunosuppression, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and others.

The patient-centric risk factors, in contrast, have not been well characterized. And it’s critical to thoroughly understand these risk factors in order to develop targeted prevention and surveillance strategies, Dr. Scott said.

“There remains a significant knowledge gap within our field. I would venture that the majority of this audience has treated a patient with skin cancer who has had a transplant,” he said. “Yet when a patient asks us, ‘Doc, what is my risk for skin cancer after my HCT?’ we’re really unable to give them an accurate and complete assessment of that risk. That’s because we’re missing the second major category of risk factors: the patient-specific risk factors.”

The reason for that, he added, is that the major population-based studies and national HCT registries are run by hematologists and oncologists, and they haven’t adequately captured the patient-specific skin cancer risk factors. But these are variables very familiar to dermatologists. They include skin phenotype, history of UV radiation exposure, and history of pre-HCT skin cancer.

Dr. Scott said the multicenter study he presented has two major advantages over prior studies: its large size and thorough followup. Nearly all 876 patients were followed by both an oncologist and a dermatologist at the same institution.

During followup, the HCT recipients collectively developed 63 SCCs, 55 BCCs, and 16 malignant melanomas. The 5- and 10-year incidence rates for SCC were 10.6% and 17.2%. For BCC, the 5- and 10-year rates were 5.7% and 17.6%. All 16 cases of melanoma occurred within 5 years after HCT.

In multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses, photodamage documented on examination was independently associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk of post-HCT SCC and a 3.5-fold increased risk of BCC.

A pre-transplant history of BCC was associated with a 3.9-fold increased likelihood of developing a BCC afterwards. Similarly, a pre-HCT history of SCC conferred a 4.2-fold increased risk of post-transplant SCC and was also independently associated with a 6.6-fold increased risk of developing melanoma post-HCT.

Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were respectively associated with 9.3- and 7.2-fold increased risks of post-HCT nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with skin types III-VI.

Acute GVHD wasn’t associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer after HCT. However, in an observation that hasn’t previously been reported by others, chronic GVHD with skin involvement was associated with a 2.7-fold increased likelihood of SCC post-HCT, Dr. Scott noted.

What’s next for Dr. Scott and his coinvestigators? “Our ultimate goal with this project is to develop an interactive risk assessment tool like the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool that can be online and used by patients and providers to estimate their individualized risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma after HCT,” he said.

Dr. Scott reported having no financial conflicts related to the study.

CHICAGO – The 10-year incidence rates for both squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising after hematopoietic cell transplantation are impressively high at 17%-plus for each, but the malignancies occur on two very different timelines, according to Jeffrey F. Scott, MD, a fellow in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Most of the squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in a large multicenter retrospective study developed within the first 5 years following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), while the majority of the basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) occurred after that point, Dr. Scott reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

He presented the results of the study, which included 876 HCT recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years. The study objective was to pin down the risk factors for skin cancer after HCT, especially the patient-specific ones. This has become a pressing issue because the use of HCT is steadily growing, and the 5-year survival rate now exceeds 50%.

The transplant-specific risk factors have previously been fairly well described by others. They include the donor source, type of disease, the conditioning regimen, whether whole body irradiation was used, immunosuppression, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and others.

The patient-centric risk factors, in contrast, have not been well characterized. And it’s critical to thoroughly understand these risk factors in order to develop targeted prevention and surveillance strategies, Dr. Scott said.

“There remains a significant knowledge gap within our field. I would venture that the majority of this audience has treated a patient with skin cancer who has had a transplant,” he said. “Yet when a patient asks us, ‘Doc, what is my risk for skin cancer after my HCT?’ we’re really unable to give them an accurate and complete assessment of that risk. That’s because we’re missing the second major category of risk factors: the patient-specific risk factors.”

The reason for that, he added, is that the major population-based studies and national HCT registries are run by hematologists and oncologists, and they haven’t adequately captured the patient-specific skin cancer risk factors. But these are variables very familiar to dermatologists. They include skin phenotype, history of UV radiation exposure, and history of pre-HCT skin cancer.

Dr. Scott said the multicenter study he presented has two major advantages over prior studies: its large size and thorough followup. Nearly all 876 patients were followed by both an oncologist and a dermatologist at the same institution.

During followup, the HCT recipients collectively developed 63 SCCs, 55 BCCs, and 16 malignant melanomas. The 5- and 10-year incidence rates for SCC were 10.6% and 17.2%. For BCC, the 5- and 10-year rates were 5.7% and 17.6%. All 16 cases of melanoma occurred within 5 years after HCT.

In multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses, photodamage documented on examination was independently associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk of post-HCT SCC and a 3.5-fold increased risk of BCC.

A pre-transplant history of BCC was associated with a 3.9-fold increased likelihood of developing a BCC afterwards. Similarly, a pre-HCT history of SCC conferred a 4.2-fold increased risk of post-transplant SCC and was also independently associated with a 6.6-fold increased risk of developing melanoma post-HCT.

Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were respectively associated with 9.3- and 7.2-fold increased risks of post-HCT nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with skin types III-VI.

Acute GVHD wasn’t associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer after HCT. However, in an observation that hasn’t previously been reported by others, chronic GVHD with skin involvement was associated with a 2.7-fold increased likelihood of SCC post-HCT, Dr. Scott noted.

What’s next for Dr. Scott and his coinvestigators? “Our ultimate goal with this project is to develop an interactive risk assessment tool like the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool that can be online and used by patients and providers to estimate their individualized risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma after HCT,” he said.

Dr. Scott reported having no financial conflicts related to the study.

CHICAGO – The 10-year incidence rates for both squamous cell carcinoma and basal cell carcinoma arising after hematopoietic cell transplantation are impressively high at 17%-plus for each, but the malignancies occur on two very different timelines, according to Jeffrey F. Scott, MD, a fellow in micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland.

Most of the squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) in a large multicenter retrospective study developed within the first 5 years following hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), while the majority of the basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) occurred after that point, Dr. Scott reported at the annual meeting of the American College of Mohs Surgery.

He presented the results of the study, which included 876 HCT recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years. The study objective was to pin down the risk factors for skin cancer after HCT, especially the patient-specific ones. This has become a pressing issue because the use of HCT is steadily growing, and the 5-year survival rate now exceeds 50%.

The transplant-specific risk factors have previously been fairly well described by others. They include the donor source, type of disease, the conditioning regimen, whether whole body irradiation was used, immunosuppression, graft versus host disease (GVHD), and others.

The patient-centric risk factors, in contrast, have not been well characterized. And it’s critical to thoroughly understand these risk factors in order to develop targeted prevention and surveillance strategies, Dr. Scott said.

“There remains a significant knowledge gap within our field. I would venture that the majority of this audience has treated a patient with skin cancer who has had a transplant,” he said. “Yet when a patient asks us, ‘Doc, what is my risk for skin cancer after my HCT?’ we’re really unable to give them an accurate and complete assessment of that risk. That’s because we’re missing the second major category of risk factors: the patient-specific risk factors.”

The reason for that, he added, is that the major population-based studies and national HCT registries are run by hematologists and oncologists, and they haven’t adequately captured the patient-specific skin cancer risk factors. But these are variables very familiar to dermatologists. They include skin phenotype, history of UV radiation exposure, and history of pre-HCT skin cancer.

Dr. Scott said the multicenter study he presented has two major advantages over prior studies: its large size and thorough followup. Nearly all 876 patients were followed by both an oncologist and a dermatologist at the same institution.

During followup, the HCT recipients collectively developed 63 SCCs, 55 BCCs, and 16 malignant melanomas. The 5- and 10-year incidence rates for SCC were 10.6% and 17.2%. For BCC, the 5- and 10-year rates were 5.7% and 17.6%. All 16 cases of melanoma occurred within 5 years after HCT.

In multivariate Cox proportional hazard analyses, photodamage documented on examination was independently associated with a 3.2-fold increased risk of post-HCT SCC and a 3.5-fold increased risk of BCC.

A pre-transplant history of BCC was associated with a 3.9-fold increased likelihood of developing a BCC afterwards. Similarly, a pre-HCT history of SCC conferred a 4.2-fold increased risk of post-transplant SCC and was also independently associated with a 6.6-fold increased risk of developing melanoma post-HCT.

Fitzpatrick skin types I and II were respectively associated with 9.3- and 7.2-fold increased risks of post-HCT nonmelanoma skin cancer, compared with skin types III-VI.

Acute GVHD wasn’t associated with an increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer after HCT. However, in an observation that hasn’t previously been reported by others, chronic GVHD with skin involvement was associated with a 2.7-fold increased likelihood of SCC post-HCT, Dr. Scott noted.

What’s next for Dr. Scott and his coinvestigators? “Our ultimate goal with this project is to develop an interactive risk assessment tool like the National Cancer Institute’s Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool that can be online and used by patients and providers to estimate their individualized risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma after HCT,” he said.

Dr. Scott reported having no financial conflicts related to the study.

REPORTING FROM THE ACMS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Photodamage documented on examination more than triples the risk of developing nonmelanoma skin cancer after hematopoietic cell transplantation.

Study details: A multicenter retrospective study of 876 hematopoietic cell recipients followed for a mean of 6.1 years.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts related to the study, which was conducted without commercial support.

New Guidelines for Nonmelanoma Skin Cancer: What You Need to Know

Nevus count tied to BCC risk

ORLANDO – The more , according to a review of over 200,000 subjects in decades-long health professional cohorts.

It’s well known that nevi increase the risk of melanoma, and the study confirmed that fact. The basal cell carcinoma finding, however, is novel. “The relationship between nevi and non-melanoma skin cancer has not [previously] been clearly demonstrated in large population cohorts,” said lead investigator Erin X. Wei, MD, a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Nevus count serves as a convenient maker to identify patients at risk for both melanoma and basal cell carcinoma. Providers should be aware of these increased risks in patients with any nevi on the extremity, particularly 15 or more,” she said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

There was no association, meanwhile, between nevus counts and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

The team reviewed 176,317 women in the Nurses’ Health Study 1 and 2, as well as 32,383 men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Subjects were enrolled in the 1980s and followed through 2012. They reported nevus counts on their arms or legs at baseline, and filled out questionnaires on a regular basis that, among many other things, asked about new skin cancer diagnoses.

Overall, there were 30,457 incident basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), 1,704 incident melanomas, and 2,296 incident SCCs. Melanomas and SCCs – as well as a portion of BCCs – were confirmed by histology.

The team correlated the skin cancer incidence with how many moles subjects reported at baseline: zero, 1-5, 6-14, or 15 or more.

“Surprisingly, having any nevi on an extremity was associated with a significant increase in the risk of basal cell carcinoma,” in a dose-dependent manner, with 15 or more conferring a 40% increased risk of BCC, compared to subjects with no extremity nevi, Dr. Wei said (P less than .0001).

Even one mole also increased the risk of melanoma; having six or more nearly tripled it, again in a dose-dependent fashion (P less than .0001). Extremity nevi increased the risk of melanoma across all anatomic sites, including head, neck, and trunk.

The findings were statistically significant, and adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, sun exposure, sunburn history, and other confounders.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant disclosures.

aotto@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Wei EX et al. 2018 International Investigative Dermatology meeting abstract 233

ORLANDO – The more , according to a review of over 200,000 subjects in decades-long health professional cohorts.

It’s well known that nevi increase the risk of melanoma, and the study confirmed that fact. The basal cell carcinoma finding, however, is novel. “The relationship between nevi and non-melanoma skin cancer has not [previously] been clearly demonstrated in large population cohorts,” said lead investigator Erin X. Wei, MD, a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Nevus count serves as a convenient maker to identify patients at risk for both melanoma and basal cell carcinoma. Providers should be aware of these increased risks in patients with any nevi on the extremity, particularly 15 or more,” she said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

There was no association, meanwhile, between nevus counts and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

The team reviewed 176,317 women in the Nurses’ Health Study 1 and 2, as well as 32,383 men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Subjects were enrolled in the 1980s and followed through 2012. They reported nevus counts on their arms or legs at baseline, and filled out questionnaires on a regular basis that, among many other things, asked about new skin cancer diagnoses.

Overall, there were 30,457 incident basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), 1,704 incident melanomas, and 2,296 incident SCCs. Melanomas and SCCs – as well as a portion of BCCs – were confirmed by histology.

The team correlated the skin cancer incidence with how many moles subjects reported at baseline: zero, 1-5, 6-14, or 15 or more.

“Surprisingly, having any nevi on an extremity was associated with a significant increase in the risk of basal cell carcinoma,” in a dose-dependent manner, with 15 or more conferring a 40% increased risk of BCC, compared to subjects with no extremity nevi, Dr. Wei said (P less than .0001).

Even one mole also increased the risk of melanoma; having six or more nearly tripled it, again in a dose-dependent fashion (P less than .0001). Extremity nevi increased the risk of melanoma across all anatomic sites, including head, neck, and trunk.

The findings were statistically significant, and adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, sun exposure, sunburn history, and other confounders.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant disclosures.

aotto@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Wei EX et al. 2018 International Investigative Dermatology meeting abstract 233

ORLANDO – The more , according to a review of over 200,000 subjects in decades-long health professional cohorts.

It’s well known that nevi increase the risk of melanoma, and the study confirmed that fact. The basal cell carcinoma finding, however, is novel. “The relationship between nevi and non-melanoma skin cancer has not [previously] been clearly demonstrated in large population cohorts,” said lead investigator Erin X. Wei, MD, a dermatologist at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Nevus count serves as a convenient maker to identify patients at risk for both melanoma and basal cell carcinoma. Providers should be aware of these increased risks in patients with any nevi on the extremity, particularly 15 or more,” she said at the International Investigative Dermatology meeting.

There was no association, meanwhile, between nevus counts and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).

The team reviewed 176,317 women in the Nurses’ Health Study 1 and 2, as well as 32,383 men in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Subjects were enrolled in the 1980s and followed through 2012. They reported nevus counts on their arms or legs at baseline, and filled out questionnaires on a regular basis that, among many other things, asked about new skin cancer diagnoses.

Overall, there were 30,457 incident basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), 1,704 incident melanomas, and 2,296 incident SCCs. Melanomas and SCCs – as well as a portion of BCCs – were confirmed by histology.

The team correlated the skin cancer incidence with how many moles subjects reported at baseline: zero, 1-5, 6-14, or 15 or more.

“Surprisingly, having any nevi on an extremity was associated with a significant increase in the risk of basal cell carcinoma,” in a dose-dependent manner, with 15 or more conferring a 40% increased risk of BCC, compared to subjects with no extremity nevi, Dr. Wei said (P less than .0001).

Even one mole also increased the risk of melanoma; having six or more nearly tripled it, again in a dose-dependent fashion (P less than .0001). Extremity nevi increased the risk of melanoma across all anatomic sites, including head, neck, and trunk.

The findings were statistically significant, and adjusted for age, body mass index, smoking, sun exposure, sunburn history, and other confounders.

There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant disclosures.

aotto@frontlinemedcom.com

SOURCE: Wei EX et al. 2018 International Investigative Dermatology meeting abstract 233

REPORTING FROM IID 2018

Key clinical point: The more nevi a person has, the greater the risk of basal cell carcinoma.

Major finding: Having 15 or more moles on the arms and legs increased the risk 40% (P less than .0001).

Study details: Review of over 200,000 subjects in decades-long health professional cohorts

Disclosures: There was no industry funding for the work, and the investigators had no relevant disclosures.

Source: Wei EX et al. 2018 International Investigative Dermatology meeting abstract 233

Unusual Presentation of Ectopic Extramammary Paget Disease

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a malignant epithelial tumor that most commonly affects the anogenital region and less frequently arises in the axillae. Most cases occur in locations where apocrine glands predominate.1 Few cases of EMPD arising in nonapocrine-bearing regions, or ectopic EMPD, have been reported.2 We describe a case of primary ectopic EMPD with an infiltrative growth pattern arising on the back of a 67-year-old Thai man.

Case Report

A 67-year-old Thai man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent rash on the right lower back of approximately 30 years’ duration. He reported that the eruption had started out as a small coin-shaped area but had slowly increased in size. Over the last 2 years, the area had grown more rapidly and became pruritic. His medical history was remarkable for hypertension treated with losartan, but he was otherwise healthy. He had no history of cancer or gastrointestinal tract or genitourinary symptoms, and he had no recent fever, weight loss, or night sweats.

On physical examination a well-demarcated, asymmetric, erythematous to brown plaque was noted on the right lower back. The plaque was surfaced by scale and contained a central hyperkeratotic papule (Figure 1). The skin examination was otherwise unremarkable. The patient had no lymphadenopathy.

Two punch biopsies were performed. On low power, acanthosis and hyperkeratosis of the epidermis were noted. The epidermis contained a proliferation of large (tumor) cells with pleomorphic nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and abundant pale to clear cytoplasm. The cells were present singularly as well as in clusters and were most prominent along the basal layer but many were also seen extending to more superficial levels of the epidermis (Figure 2A). In one biopsy, the tumor cells were found in the dermis with an infiltrative growth pattern (Figure 2B). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) studies for cytokeratin 7 (Figure 3A and 3B) and carcinoembryonic antigen (Figure 3C) labeled the tumor cells. An IHC study for gross cystic disease fluid protein 15 labeled some of the tumor cells. Immunohistochemistry studies for S-100, human melanoma black 45 (HMB-45), p16, and renal cell carcinoma did not label the tumor cells. An IHC study for MIB-1 labeled many of the tumor cells, indicating a notably increased mitotic index. The patient was diagnosed with ectopic EMPD. He underwent an endoscopy, colonoscopy, and cystoscopy, all of which were normal.

Comment

Extramammary Paget disease is a malignant tumor typically found in apocrine-rich areas of the skin, particularly the anogenital skin. It is categorized as primary or secondary EMPD. Primary EMPD arises as an intraepithelial adenocarcinoma, with the Toker cell as the cell of origin.3 Secondary EMPD represents a cutaneous extension of an underlying malignancy (eg, colorectal, urothelial, prostatic, gynecologic).4

Ectopic EMPD arises in nonapocrine-bearing areas, specifically the nongerminative milk line. A review of the literature using Google Scholar and the search term ectopic extramammary Paget disease showed that there have been at least 30 cases of ectopic EMPD reported. Older men are more commonly affected, with a mean age at diagnosis of approximately 68 years. Although the tumor is most commonly seen on the trunk, cases on the head, arms, and legs have been reported.5

This tumor is most frequently seen in Asian individuals, as in our patient, with a ratio of approximately 3:1.5 Interestingly, triple or quadruple EMPD was reported in 68 Japanese patients but rarely has been reported outside of Japan.6 It is thought that some germinative apocrine-differentiating cells might preferentially exist on the trunk of Asians, leading to an increased incidence of EMPD in this population5; however, the exact reason for this racial preference is not completely understood, and more studies are needed to investigate this association.

Diagnosis of ectopic EMPD is made histologically. Tumor cells have abundant pale cytoplasm and large pleomorphic nuclei with prominent nucleoli. The cells are arranged in small groups or singly within the basal regions of the epidermis. In longstanding lesions, the entire thickness of the epidermis may be involved. Uncommonly, the tumor cells may invade the dermis, such as in our patient. On immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells stain positive for carcinoembryonic antigen, epithelial membrane antigen, and low-molecular-weight cytokeratins (eg, cytokeratin 7). Many of the tumor cells also express gross cystic disease fluid protein 15, which helps exclude cutaneous invasion of secondary EMPD.7-9 Cases of primary cutaneous apocrine carcinoma can have similar histologic and immunohistochemical findings to invasive EMPD, which further supports the possible apocrine derivation of Paget disease. In our patient, we considered the diagnosis of primary cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma with epidermotropism; however, we favored the diagnosis of ectopic EMPD with dermal invasion given the extensive epidermal-only involvement seen in one of the biopsies, which would be unusual for primary cutaneous apocrine adenocarcinoma.

Our patient had no identified underlying malignancy upon further workup; however, many cases of EMPD have been associated with an underlying malignancy.9-15 Several authors have reported a range of underlying malignancies associated with EMPD, with the incidence ranging from 11% to 45%.9-15 The location of the underlying internal malignancy appears to be closely related to the location of the EMPD.11 It is recommended that a thorough workup for internal malignancies be performed, including a full skin examination, lymph node examination, colonoscopy, cystoscopy, and gynecologic/prostate examination, among others.

No known differences in the prognosis or associated underlying malignancies between ectopic and ordinary EMPD have been reported; however, it has been noted that EMPD with invasion into the dermis does correlate with a more aggressive course and worse prognosis.8 Treatment includes surgical removal by Mohs micrographic surgery or wide local excision. Long-term follow-up is required since recurrences can be frequent.11-15

- Mazoujian G, Pinkus GS, Haagensen DE Jr. Extramammary Paget’s disease—evidence for an apocrine origin: an immunoperoxidase study of gross cystic disease fluid protein-15, carcinoembryonic antigen, and keratin proteins. Am J Surg Pathol. 1984;8:43-50.

- Saida T, Iwata M. “Ectopic” extramammary Paget’s disease affecting the lower anterior aspect of the chest. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17(5, pt 2):910-913.

- Willman JH, Golitz LE, Fitzpatrick JE. Vulvar clear cells of Toker: precursors of extramammary Paget’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:185-188.

- Lloyd J, Flanagan AM. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease.J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:742-749.

- Sawada Y, Bito T, Kabashima R, et al. Ectopic extramammary Paget’s disease: case report and literature review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2010;90:502-505.

- Abe S, Kabashima K, Nishio D, et al. Quadruple extramammary Paget’s disease. Acta Derm Venereol. 2007;87:80-81.

- Kanitakis J. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:581-590.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Vulvar Paget’s disease: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 19 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1178-1187.

- Goldblum JR, Hart WR. Perianal Paget’s disease: a histologic and immunohistochemical study of 11 cases with and without associated rectal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:170-179.

- Shepherd V, Davidson EJ, Davies‐Humphreys J. Extramammary Paget’s disease. BJOG. 2005;112:273-279.

- Chanda JJ. Extramammary Paget’s disease: prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:1009-1014.

- Besa P, Rich TA, Delclos L, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the perineal skin: role of radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;24:73-78.

- Fanning J, Lambert HC, Hale TM, et al. Paget’s disease of the vulva: prevalence of associated vulvar adenocarcinoma, invasive Paget’s disease, and recurrence after surgical excision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:24-27.

- Parker LP, Parker JR, Bodurka-Bevers D, et al. Paget’s disease of the vulva: pathology, pattern of involvement, and prognosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;77:183-189.

- Marchesa P, Fazio VW, Oliart S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with perianal Paget’s disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:475-480.

Extramammary Paget disease (EMPD) is a malignant epithelial tumor that most commonly affects the anogenital region and less frequently arises in the axillae. Most cases occur in locations where apocrine glands predominate.1 Few cases of EMPD arising in nonapocrine-bearing regions, or ectopic EMPD, have been reported.2 We describe a case of primary ectopic EMPD with an infiltrative growth pattern arising on the back of a 67-year-old Thai man.

Case Report

A 67-year-old Thai man presented to the dermatology clinic for evaluation of a persistent rash on the right lower back of approximately 30 years’ duration. He reported that the eruption had started out as a small coin-shaped area but had slowly increased in size. Over the last 2 years, the area had grown more rapidly and became pruritic. His medical history was remarkable for hypertension treated with losartan, but he was otherwise healthy. He had no history of cancer or gastrointestinal tract or genitourinary symptoms, and he had no recent fever, weight loss, or night sweats.

On physical examination a well-demarcated, asymmetric, erythematous to brown plaque was noted on the right lower back. The plaque was surfaced by scale and contained a central hyperkeratotic papule (Figure 1). The skin examination was otherwise unremarkable. The patient had no lymphadenopathy.