User login

Dr. Douglas Paauw gives updates on antihypertensives, statins, SGLT2 inhibitors

PHILADELPHIA – in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Paauw, professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, began by discussing some of the issues that occurred with antihypertensive drugs in the past year. These included the link between hydrochlorothiazide use and the increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers, the recalls of many drug lots of angiotensin II receptor blockers, and a study that found an increased risk of lung cancer in people who were taking ACE inhibitors.

He then described the findings of studies that examined the links between statins and muscle pain and other new research on these drugs.

He also warned physicians to be particularity cautious about prescribing sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors to certain kinds of patients.

Dr. Paauw concluded by explaining why clarithromycin is his most hated drug.

Dr. Paauw is also the Rathmann Family Foundation Endowed Chair for Patient-Centered Clinical Education and the medicine clerkship director at the University of Washington.

klennon@mdedge.com

PHILADELPHIA – in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Paauw, professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, began by discussing some of the issues that occurred with antihypertensive drugs in the past year. These included the link between hydrochlorothiazide use and the increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers, the recalls of many drug lots of angiotensin II receptor blockers, and a study that found an increased risk of lung cancer in people who were taking ACE inhibitors.

He then described the findings of studies that examined the links between statins and muscle pain and other new research on these drugs.

He also warned physicians to be particularity cautious about prescribing sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors to certain kinds of patients.

Dr. Paauw concluded by explaining why clarithromycin is his most hated drug.

Dr. Paauw is also the Rathmann Family Foundation Endowed Chair for Patient-Centered Clinical Education and the medicine clerkship director at the University of Washington.

klennon@mdedge.com

PHILADELPHIA – in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

Dr. Paauw, professor of medicine at the University of Washington, Seattle, began by discussing some of the issues that occurred with antihypertensive drugs in the past year. These included the link between hydrochlorothiazide use and the increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancers, the recalls of many drug lots of angiotensin II receptor blockers, and a study that found an increased risk of lung cancer in people who were taking ACE inhibitors.

He then described the findings of studies that examined the links between statins and muscle pain and other new research on these drugs.

He also warned physicians to be particularity cautious about prescribing sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors to certain kinds of patients.

Dr. Paauw concluded by explaining why clarithromycin is his most hated drug.

Dr. Paauw is also the Rathmann Family Foundation Endowed Chair for Patient-Centered Clinical Education and the medicine clerkship director at the University of Washington.

klennon@mdedge.com

REPORTING FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2019

The Evolution of the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

Originating in 1968, the dermatologic surgery fellowship is as young as many dermatologists in practice today. Not surprisingly, the blossoming fellowship has undergone its fair share of both growth and growing pains over the last 5 decades.

A Brief History

The first dermatologic surgery fellowship was born in 1968 when Dr. Perry Robins established a program at the New York University Medical Center for training in chemosurgery.1 The fellowship quickly underwent notable change with the rising popularity of the fresh tissue technique, which was first performed by Dr. Fred Mohs in 1953 and made popular following publication of a series of landmark articles on the technique by Drs. Sam Stegman and Theodore Tromovitch in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The fellowship correspondingly saw a rise in fresh tissue technique training, accompanied by a decline in chemosurgery training. In 1974, Dr. Daniel Jones coined the term micrographic surgery to describe the favored technique, and at the 1985 annual meeting of the American College of Chemosurgery, the name of the technique was changed to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

By 1995, the fellowship was officially named Procedural Dermatology, and programs were exclusively accredited by the American College of Mohs Surgery (ACMS). A 1-year Procedural Dermatology fellowship gained accreditation by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) in 2003.2 Beginning in July 2013, all fellowship programs in the United States fell under the governance of the ACGME; however, the ACMS has remained the sponsor of the matching process.3 In 2014, the ACGME changed the name of the fellowship to Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology (MSDO).2 Fellowship training today is centered on the core elements of cutaneous oncologic surgery, cutaneous reconstructive surgery, and dermatologic oncology; however, the scope of training in technologies and techniques offered has continued to broaden.4 Many programs now offer additional training in cosmetic and other procedural dermatology. To date, there are 76 accredited MSDO fellowship training programs in the United States and more than 1500 fellowship-trained micrographic surgeons.2,4

Trends in Program and Match Statistics

As the role of dermatologic surgery within the field of dermatology continues to expand, the MSDO fellowship has become increasingly popular over the last decade. From 2005 to 2018, applicants participating in the fellowship match increased by 34%.3 Despite the fellowship’s growing popularity, programs participating in the match have remained largely stable from 2005 to 2018, with 50 positions offered in 2005 and 58 in 2018. The match rate has correspondingly decreased from 66.2% in 2005 to 61.1% in 2018.3

Changes in the Match Process

The fellowship match is processed by the SF Match and sponsored by the ACMS. Over the last decade, programs have increasingly opted for exemptions from participation in the SF Match. In 2005, there were 8 match exemptions. In 2018, there were 20.4 Despite the increasing popularity of match exemptions, in October 2018 the ACMS Board of Directors approved a new policy that eliminated match exemptions, with the exception of applicants on active military duty and international (non-Canadian) applicants. All other applicants applying for a fellowship position for the 2020-2021 academic year must participate in the match.4 This new policy attempts to ensure a fair match process, especially for applicants who have trained at a program without an affiliated MSDO fellowship.

The Road to Board Certification

Further growth during the fellowship’s mid-adult years centered on the long-contested debate on subspecialty board certification. In 2009, an American Society for Dermatologic Surgery membership survey demonstrated an overwhelming majority in opposition. In 2014, the debate resurfaced. At the 2016 American Society for Dermatologic Surgery annual meeting, former American Academy of Dermatology presidents Brett Coldiron, MD, and Darrell S. Rigel, MD, MS, conveyed opposing positions, after which an audience survey demonstrated a 69% opposition rate. Proponents continued to argue that board certification would decrease divisiveness in the specialty, create a better brand, help to obtain a Medicare specialty designation that could help prevent exclusion of Mohs surgeons from insurance networks, give allopathic dermatologists the same opportunity for certification as osteopathic counterparts, and demonstrate competence to the public. Those in opposition argued that the term dermatologic oncology erroneously suggests general dermatologists are not experts in the treatment of skin cancers, practices may be restricted by carriers misusing the new credential, and subspecialty certification would actually create division among practicing dermatologists.5

Following years of debate, the American Board of Dermatology’s proposal to offer subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery was submitted to the American Board of Medical Specialties and approved on October 26, 2018. The name of the new subspecialty (Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery) is different than that of the fellowship (Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology), a decision reached in response to diplomats indicating discomfort with the term oncology potentially misleading the public that general dermatologists do not treat skin cancer. Per the American Board of Dermatology official website, the first certification examination likely will take place in about 2 years. A maintenance of certification examination for the subspecialty will be required every 10 years.6

Final Thoughts

During its short history, the MSDO fellowship has undergone a notable evolution in recognition, popularity among residents, match process, and board certification, which attests to its adaptability over time and growing prominence.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Robins P, Ebede TL, Hale EK. The evolution of Mohs micrographic surgery. Skin Cancer Foundation website. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/mohs-surgery/evolution-of-mohs. Updated July 13, 2016. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Micrographic surgery and dermatologic oncology. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-surgery-and-dermatologic-oncology.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology Fellowship. San Francisco Match website. https://sfmatch.org/SpecialtyInsideAll.aspx?id=10&typ=1&name=Micrographic%20Surgery%20and%20Dermatologic%20Oncology. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ACMS fellowship training. American College of Mohs Surgery website. https://www.mohscollege.org/fellowship-training. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- Should the ABD offer a Mohs surgery sub-certification? Dermatology World. April 26, 2017. https://www.aad.org/dw/dw-weekly/should-the-abd-offer-a-mohs-surgery-sub-certification. Accessed April 9, 2019.

- ABD Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery (MDS) subspecialty certification. American Board of Dermatology website. https://www.abderm.org/residents-and-fellows/fellowship-training/micrographic-dermatologic-surgery-mds-questions-and-answers-1.aspx. Accessed April 9, 2019.

Resident Pearl

- Residents should be aware of recent changes to the Micrographic Surgery and Dermatologic Oncology fellowship: the elimination of fellowship match exemptions for most applicants for the upcoming 2019-2020 academic year, the American Board of Medical Specialties approval of subspecialty certification in Micrographic Dermatologic Surgery, and the likelihood of the first subspecialty certification examination in the next 2 years.

Cutaneous Metastasis of Endometrial Carcinoma: An Unusual and Dramatic Presentation

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

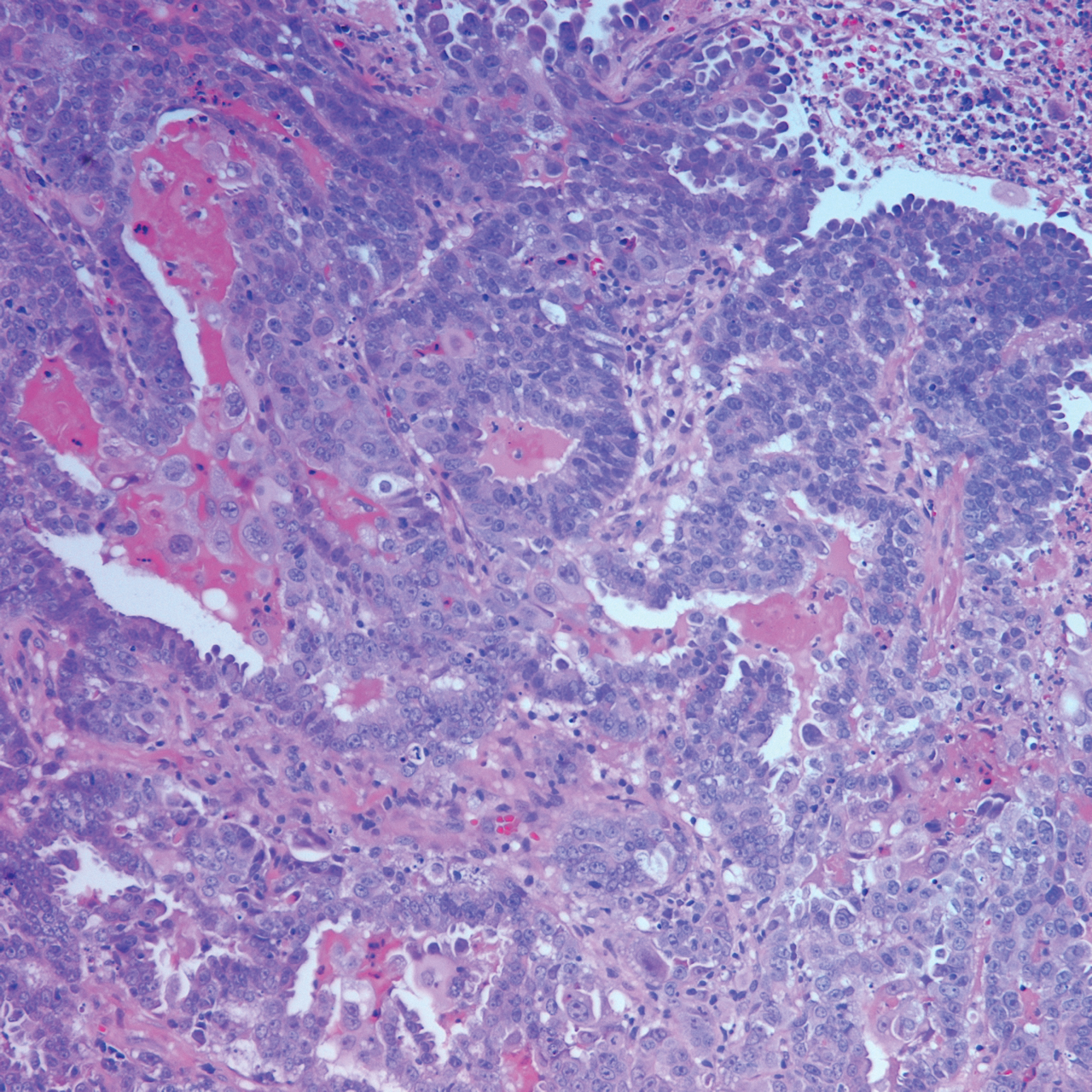

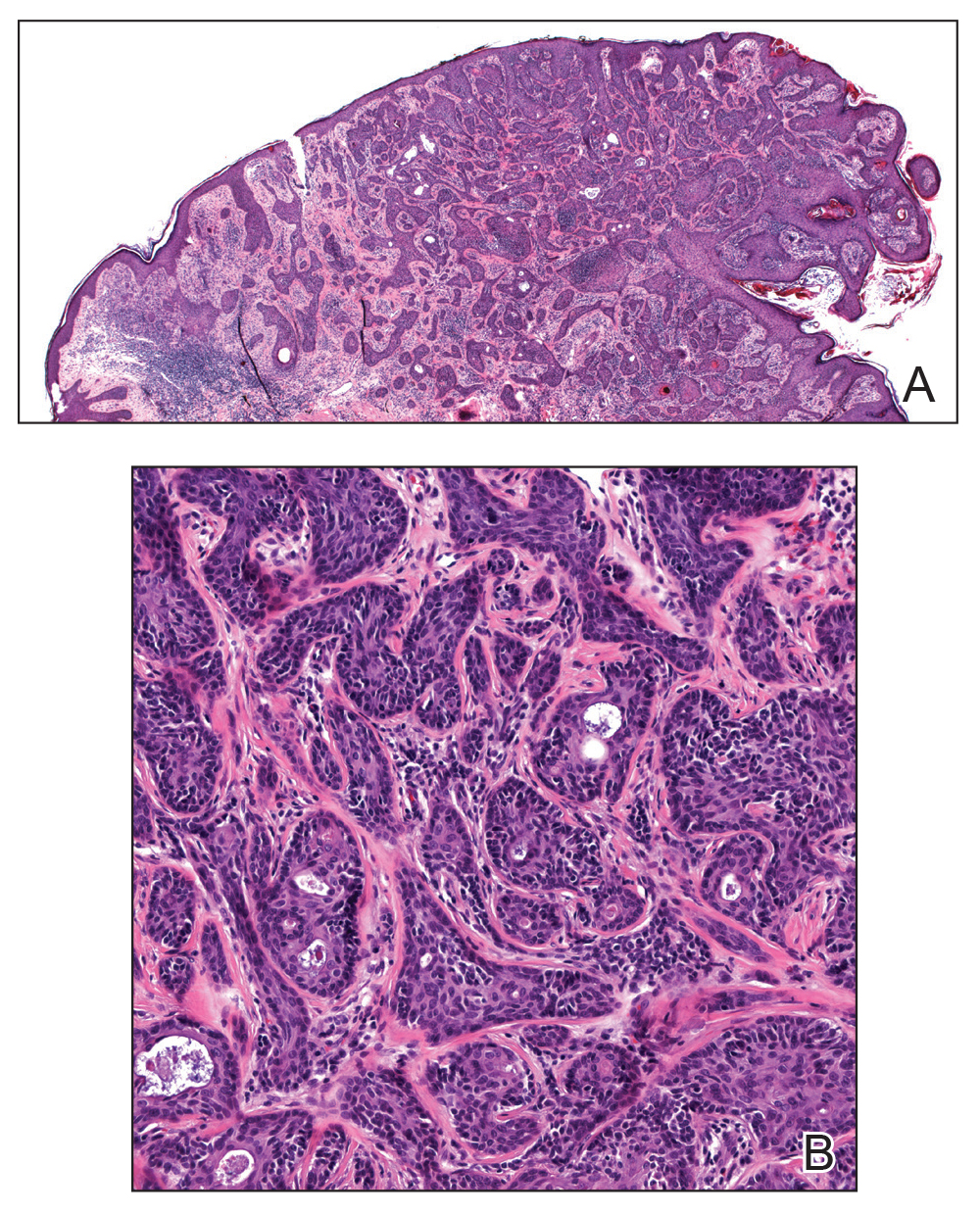

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastases of endometrial carcinoma are extremely rare and typically present in areas of direct local spread.

- As with other cutaneous metastases, lesions often are nonspecific, making history and histopathology essential for diagnosis.

Leukemia Cutis–Associated Leonine Facies and Eyebrow Loss

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis in IBD patients a consideration

WASHINGTON – (IBD), Sophia Delano, MD, said during a session on the cutaneous effects of IBD at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

This is a paradoxical reaction, which can happen “weeks to years after starting a TNF blocker,” with about 70% of cases occurring during the first year of therapy, said Dr. Delano, an attending physician in the dermatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Those receiving infliximab are more likely to develop TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis, compared with those on adalimumab or etanercept. TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis may not track with gastrointestinal activity, and some patients whose gastrointestinal disease is responding to treatment can begin to develop psoriasis, she noted.

The clinical presentation of TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis can also vary. In one study of 216 cases, 26.9% of patients had a mixed morphology, with the most common presentations including plaque psoriasis (44.8%) and palmoplantar pustular psoriasis (36.3%). Other presentations were psoriasiform dermatitis (19.9%), scalp involvement with alopecia (7.5%), and generalized pustular psoriasis (10.9%). Locations affected were the soles of the feet (45.8%), extremities (45.4%), palms (44.9%), scalp (36.1%), and trunk (32.4%), Dr. Delano said.

TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis is likely a class effect, she said, noting that, in the same review, symptoms resolved in 47.7% of patients who discontinued TNF inhibitors, in 36.7% of patients who switched to another TNF inhibitor, and in 32.9% of patients who continued their original therapy (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76[2]:334-41). In the study, Crohn’s disease and RA were the most common diseases, in 40.7% and 37.0% of the patients, respectively.

There have been case reports of TNF antagonist–induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS), which is more common in patients with RA and ulcerative colitis. TAILS occurs more often in women than in men; can present similarly to systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and chronic cutaneous lupus; and resolves by stopping TNF inhibitor treatment, Dr. Delano said.

Skin cancer risk, infections, and injection site reactions

Both adult and pediatric patients treated with TNF inhibitors for IBD may be at increased risk for lymphoma, visceral tumors, melanoma, and nonmelanoma skin cancers. Dr. Delano referred to a study published in 2014, which identified 972 reports of melanoma in the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database associated with TNF inhibitor use; of these, 69 cases involved patients using more than one TNF inhibitor. Infliximab, golimumab, etanercept, and adalimumab were associated with a safety signal for melanoma, but not certolizumab (Br J Dermatol. 2014 May;170[5]:1170-2).

Dr. Delano observed that thiopurines such as azathioprine are also associated with an increased cancer risk, as noted in one retrospective study that found that the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer was 2.1 times higher in a mostly white male cohort with ulcerative colitis during treatment with thiopurines, compared with patients not treated with thiopurines (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109[11]:1781-93). A greater duration of treatment (more than 6 months) and higher doses were associated with higher risks.

Adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab can also cause injection site reactions, typically within 1- 2 days of injection, said Dr. Delano. In these cases, symptoms of erythema, warmth, burning, or pruritus are worse at the beginning of treatment and can be relieved by rotating the injection site as well as providing cool compresses, topical steroids, antihistamines, and supportive care.

“If you have a patient with a worsening reaction, consider it may represent the type 1 IgE-related hypersensitivity requiring desensitization to continue that systemic,” she noted.

Cutaneous bacterial, fungal, and viral infections such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca vulgaris, herpes simplex, and varicella zoster can occur as a result of TNF inhibition as well, and can be difficult to clear because of immunosuppression, she added.

Dr. Delano reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – (IBD), Sophia Delano, MD, said during a session on the cutaneous effects of IBD at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

This is a paradoxical reaction, which can happen “weeks to years after starting a TNF blocker,” with about 70% of cases occurring during the first year of therapy, said Dr. Delano, an attending physician in the dermatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Those receiving infliximab are more likely to develop TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis, compared with those on adalimumab or etanercept. TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis may not track with gastrointestinal activity, and some patients whose gastrointestinal disease is responding to treatment can begin to develop psoriasis, she noted.

The clinical presentation of TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis can also vary. In one study of 216 cases, 26.9% of patients had a mixed morphology, with the most common presentations including plaque psoriasis (44.8%) and palmoplantar pustular psoriasis (36.3%). Other presentations were psoriasiform dermatitis (19.9%), scalp involvement with alopecia (7.5%), and generalized pustular psoriasis (10.9%). Locations affected were the soles of the feet (45.8%), extremities (45.4%), palms (44.9%), scalp (36.1%), and trunk (32.4%), Dr. Delano said.

TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis is likely a class effect, she said, noting that, in the same review, symptoms resolved in 47.7% of patients who discontinued TNF inhibitors, in 36.7% of patients who switched to another TNF inhibitor, and in 32.9% of patients who continued their original therapy (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76[2]:334-41). In the study, Crohn’s disease and RA were the most common diseases, in 40.7% and 37.0% of the patients, respectively.

There have been case reports of TNF antagonist–induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS), which is more common in patients with RA and ulcerative colitis. TAILS occurs more often in women than in men; can present similarly to systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and chronic cutaneous lupus; and resolves by stopping TNF inhibitor treatment, Dr. Delano said.

Skin cancer risk, infections, and injection site reactions

Both adult and pediatric patients treated with TNF inhibitors for IBD may be at increased risk for lymphoma, visceral tumors, melanoma, and nonmelanoma skin cancers. Dr. Delano referred to a study published in 2014, which identified 972 reports of melanoma in the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database associated with TNF inhibitor use; of these, 69 cases involved patients using more than one TNF inhibitor. Infliximab, golimumab, etanercept, and adalimumab were associated with a safety signal for melanoma, but not certolizumab (Br J Dermatol. 2014 May;170[5]:1170-2).

Dr. Delano observed that thiopurines such as azathioprine are also associated with an increased cancer risk, as noted in one retrospective study that found that the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer was 2.1 times higher in a mostly white male cohort with ulcerative colitis during treatment with thiopurines, compared with patients not treated with thiopurines (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109[11]:1781-93). A greater duration of treatment (more than 6 months) and higher doses were associated with higher risks.

Adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab can also cause injection site reactions, typically within 1- 2 days of injection, said Dr. Delano. In these cases, symptoms of erythema, warmth, burning, or pruritus are worse at the beginning of treatment and can be relieved by rotating the injection site as well as providing cool compresses, topical steroids, antihistamines, and supportive care.

“If you have a patient with a worsening reaction, consider it may represent the type 1 IgE-related hypersensitivity requiring desensitization to continue that systemic,” she noted.

Cutaneous bacterial, fungal, and viral infections such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca vulgaris, herpes simplex, and varicella zoster can occur as a result of TNF inhibition as well, and can be difficult to clear because of immunosuppression, she added.

Dr. Delano reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

WASHINGTON – (IBD), Sophia Delano, MD, said during a session on the cutaneous effects of IBD at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

This is a paradoxical reaction, which can happen “weeks to years after starting a TNF blocker,” with about 70% of cases occurring during the first year of therapy, said Dr. Delano, an attending physician in the dermatology program at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Those receiving infliximab are more likely to develop TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis, compared with those on adalimumab or etanercept. TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis may not track with gastrointestinal activity, and some patients whose gastrointestinal disease is responding to treatment can begin to develop psoriasis, she noted.

The clinical presentation of TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis can also vary. In one study of 216 cases, 26.9% of patients had a mixed morphology, with the most common presentations including plaque psoriasis (44.8%) and palmoplantar pustular psoriasis (36.3%). Other presentations were psoriasiform dermatitis (19.9%), scalp involvement with alopecia (7.5%), and generalized pustular psoriasis (10.9%). Locations affected were the soles of the feet (45.8%), extremities (45.4%), palms (44.9%), scalp (36.1%), and trunk (32.4%), Dr. Delano said.

TNF inhibitor–induced psoriasis is likely a class effect, she said, noting that, in the same review, symptoms resolved in 47.7% of patients who discontinued TNF inhibitors, in 36.7% of patients who switched to another TNF inhibitor, and in 32.9% of patients who continued their original therapy (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb;76[2]:334-41). In the study, Crohn’s disease and RA were the most common diseases, in 40.7% and 37.0% of the patients, respectively.

There have been case reports of TNF antagonist–induced lupus-like syndrome (TAILS), which is more common in patients with RA and ulcerative colitis. TAILS occurs more often in women than in men; can present similarly to systemic lupus erythematosus, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus, and chronic cutaneous lupus; and resolves by stopping TNF inhibitor treatment, Dr. Delano said.

Skin cancer risk, infections, and injection site reactions

Both adult and pediatric patients treated with TNF inhibitors for IBD may be at increased risk for lymphoma, visceral tumors, melanoma, and nonmelanoma skin cancers. Dr. Delano referred to a study published in 2014, which identified 972 reports of melanoma in the Food and Drug Administration’s Adverse Event Reporting System database associated with TNF inhibitor use; of these, 69 cases involved patients using more than one TNF inhibitor. Infliximab, golimumab, etanercept, and adalimumab were associated with a safety signal for melanoma, but not certolizumab (Br J Dermatol. 2014 May;170[5]:1170-2).

Dr. Delano observed that thiopurines such as azathioprine are also associated with an increased cancer risk, as noted in one retrospective study that found that the risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer was 2.1 times higher in a mostly white male cohort with ulcerative colitis during treatment with thiopurines, compared with patients not treated with thiopurines (Am J Gastroenterol. 2014 Nov;109[11]:1781-93). A greater duration of treatment (more than 6 months) and higher doses were associated with higher risks.

Adalimumab, golimumab, and certolizumab can also cause injection site reactions, typically within 1- 2 days of injection, said Dr. Delano. In these cases, symptoms of erythema, warmth, burning, or pruritus are worse at the beginning of treatment and can be relieved by rotating the injection site as well as providing cool compresses, topical steroids, antihistamines, and supportive care.

“If you have a patient with a worsening reaction, consider it may represent the type 1 IgE-related hypersensitivity requiring desensitization to continue that systemic,” she noted.

Cutaneous bacterial, fungal, and viral infections such as molluscum contagiosum, verruca vulgaris, herpes simplex, and varicella zoster can occur as a result of TNF inhibition as well, and can be difficult to clear because of immunosuppression, she added.

Dr. Delano reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM AAD 2019

Pruritic Nodules on the Breast

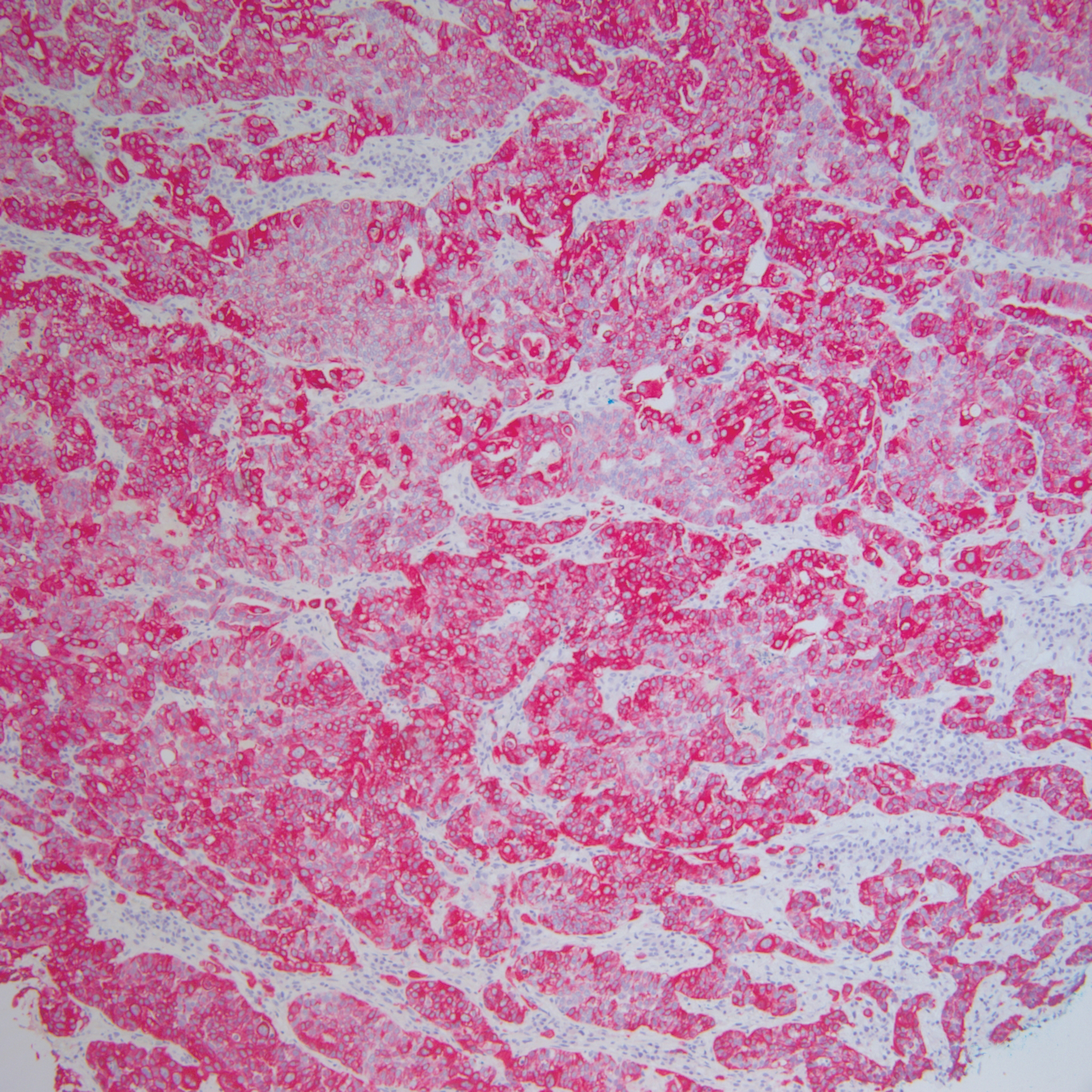

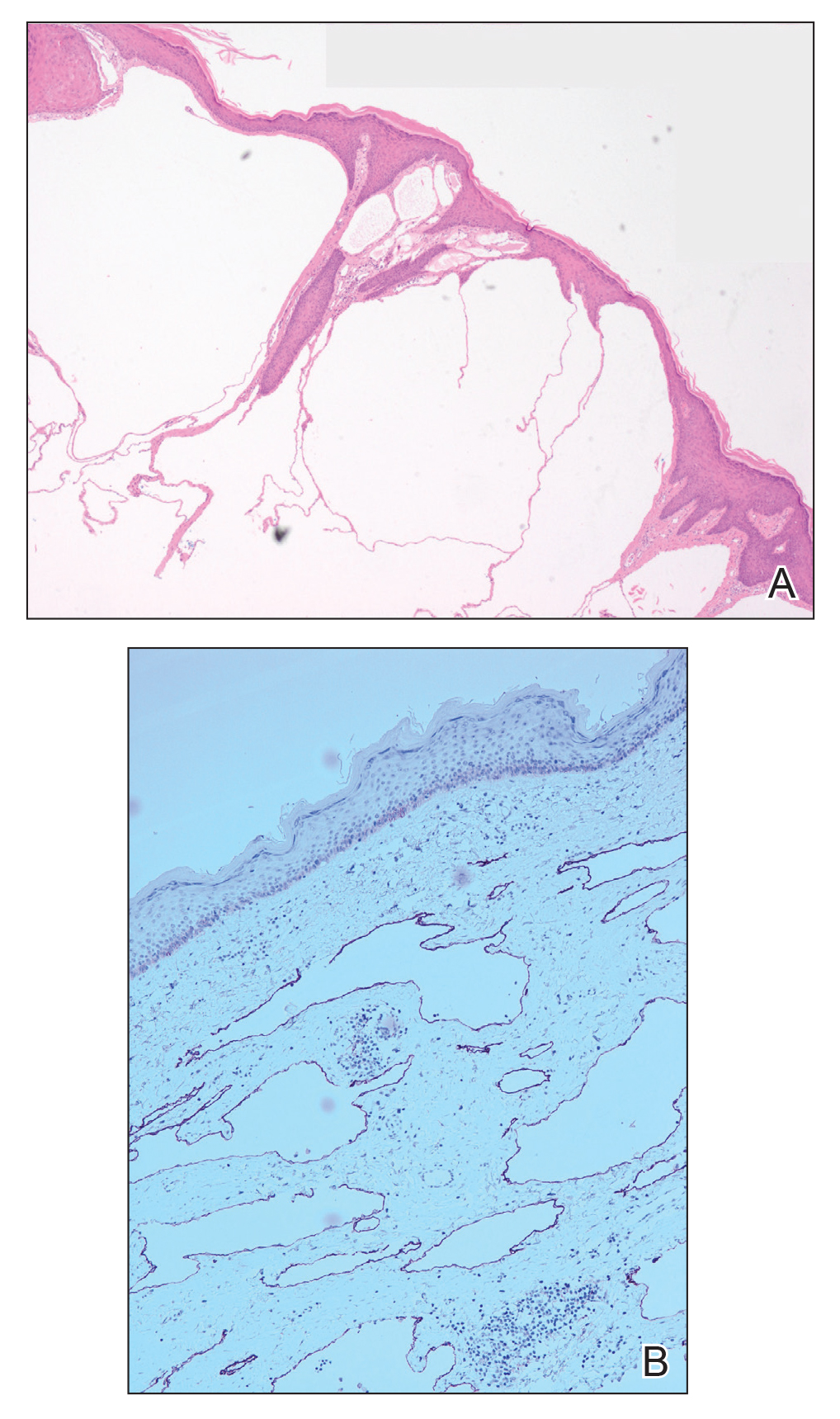

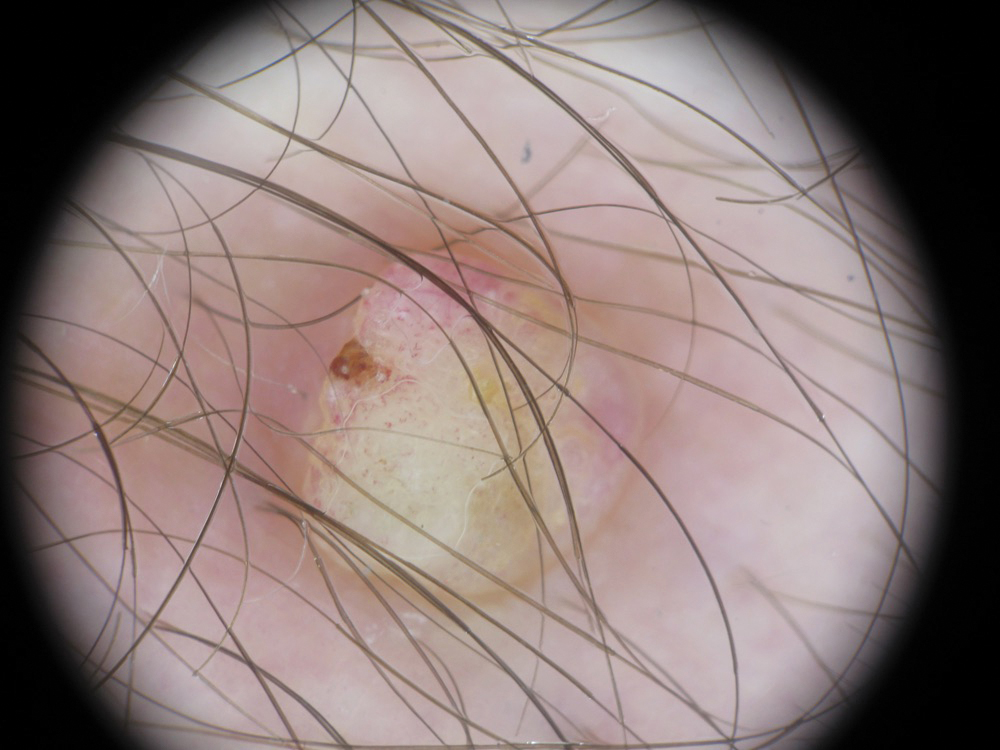

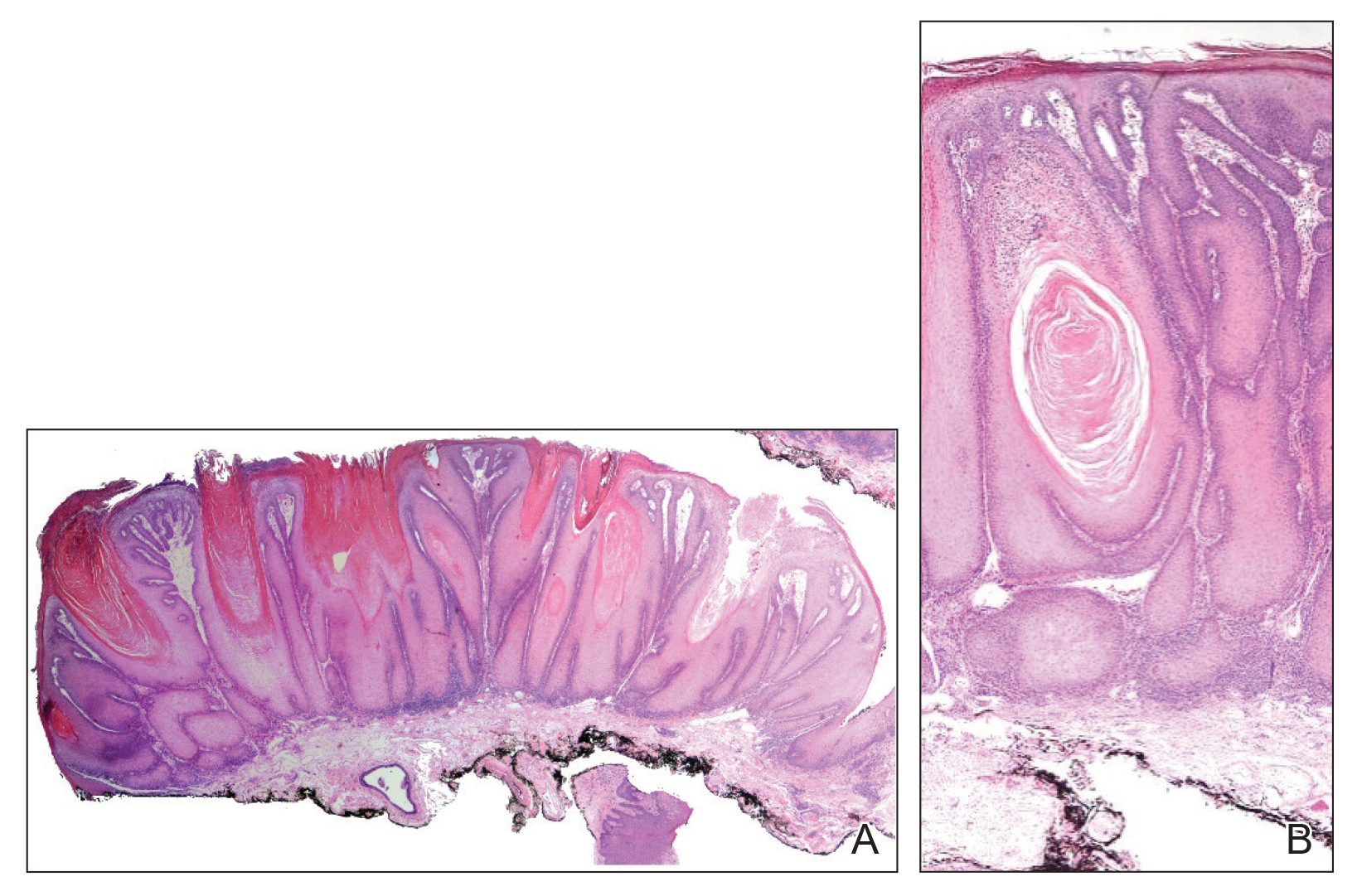

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9

Small, asymptomatic, acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations can be followed clinically without treatment, but these lesions do not commonly regress spontaneously. Even when asymptomatic, many clinicians will opt for treatment to prevent secondary complications such as infections, drainage, and pain. Moreover, these lesions can have notable psychosocial impacts on patients due to poor cosmetic appearance. Unfortunately, there is no gold standard of treatment, and recurrence is common, even after treatment. Historically, surgical excision was the treatment of choice, but this option carries a high risk for scarring, invasiveness, and recurrence. Recurrence rates of up to 23.1% have been reported with decreased effectiveness of resection, particularly in areas of deeper involvement.10 For these deeper lesions, CO2 laser therapy is a promising evolving therapy. It can penetrate up to the mid dermis and seems to destroy the lymphatic channels between deep and surface lymphatics, preventing the cutaneous manifestations of the disease. It has the added benefit of minimal invasiveness and fewer side effects than complete excision, with most studies reporting hyperpigmentation and scarring as the most common side effects.11 Additional emerging therapies including sclerotherapy and isotretinoin have shown benefits in case studies. Sclerotherapy causes local tissue destruction and thrombosis leading to destruction of vessel lumens and fibrosis that halts disease progression and clears existing lesions.12 Oral therapy with isotretinoin appears to work by inhibiting certain cytokines and acting as an antiangiogenic factor.13 Given the rarity of microcystic lymphatic malformations, further research must be done to determine definitive treatment.

Acquired microcystic lymphatic malformation is an important sequela of radiation therapy and surgical excision of malignancy. Despite its striking clinical appearance, it is sometimes difficult to diagnose given its rarity. It is important that clinicians are able to recognize it clinically and understand common treatment options to prevent both the mental stigma and complications, including secondary infections, drainage, and pain.

- Whimster IW. The pathology of lymphangioma circumscriptum. Br J Dermatol. 1976;94:473.

- Vlastos AT, Malpica A, Follen M. Lymphangioma circumscriptum of the vulva: a review of the literature. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:946-954.

- Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Burchette JL, et al. Acquired vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: a comparison of 12 cases with Crohn’s associated lesions or radiation therapy induced tumors. J Cutan Pathol. 2010;37:958-965.

- Kaya TI, Kokturk A, Polat A, et al. A case of cutaneous lymphangiectasis secondary to breast cancer treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:760-761.

- Ambrojo P, Cogolluda EF, Aguilar A, et al. Cutaneous lymphangiectases after therapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:57-59.

- Tasdelen I, Gokgoz S, Paksoy E, et al. Acquired lymphangiectasis after breast conservation treatment for breast cancer: report of a case. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:9.

- Lucas DR. Angiosarcoma, radiation-associated angiosarcoma, and atypical vascular lesion. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1804-1809.

- Brenn T, Fletcher CD. Radiation-associated cutaneous atypical vascular lesions and angiosarcoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 42 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:983-996.

- Gengler C, Coindre JM, Leroux A. Vascular proliferations of the skin after radiation therapy for breast cancer: clinicopathologic analysis of a series in favor of a benign process: a study from the French Sarcoma Group. Cancer. 2007;109:1584-1598.

- Ghaemmaghami F, Karimi Zarchi M, Mousavi A. Major labiaectomy as surgical management of vulvar lymphangioma circumscriptum: three cases and a review of the literature. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2008;278:57-60.

- Savas J. Carbon dioxide laser for the treatment of microcystic lymphatic malformations (lymphangioma circumscriptum): a systematic review. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1147-1157.

- Al Ghamdi KM, Mubki TF. Treatment of lymphangioma circumscriptum with sclerotherapy: an ignored effective remedy. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2011;10:156-158.

- Ayhan E. Lymphangioma circumscriptum: good clinical response to isotretinoin therapy. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:E208-E209.

Microcystic lymphatic malformations, also known as lymphangioma circumscriptum, are rare hamartomatous lesions comprised of dilated lymphatic channels that can be both congenital and acquired.1 They often present as translucent or hemorrhagic vesicles of varying sizes that may contain lymphatic fluid and often can cluster together and appear verrucous (Figure 1). The differential diagnosis for microcystic lymphatic malformations commonly includes molluscum contagiosum, squamous cell carcinoma, verruca vulgaris, or condylomas, as well as atypical vascular lesions. They most often are found in children as congenital lesions but also may be acquired. Most acquired cases are due to chronic inflammatory and scarring processes that damage lymphatic structures, including surgery, radiation, infections, and even Crohn disease.2,3 Because the differential diagnosis is so broad and the disease can clinically mimic other common disease processes, biopsies often are performed to determine the diagnosis. On biopsy, pathologic examination revealed well-circumscribed nodular lesions with large lymphatic channels often in a background of connective tissue stroma. Increased eosinophilic material, including mast cells, also was seen (Figure 2A). On immunohistochemistry, staining showed D2-40 positivity (Figure 2B).

Damage to lymphatics from radiation and postsurgical excision of tumors are well-described causes of microcystic lymphatic malformations, as in our patient, with most instances in the literature occurring secondary to treatment of breast or cervical cancer.4-6 In these acquired cases, the pathogenesis is thought to be due to destruction and fibrosis at the layer of the reticular dermis, which causes lymphatic obstruction and subsequent dilation of superficial lymphatic channels.6

Microcystic lymphatic malformations can be difficult to distinguish from atypical vascular lesions, another common postradiation lesion. Both are benign well-circumscribed lesions that histologically do not extend into surrounding subcutaneous tissues and do not have multilayering of cells, mitosis, or hemorrhage.7 Although lymphatic lesions tend to form vesicles, atypical vascular lesions arising after radiation treatment present as erythematous or flesh-colored patches or papules. They also tend to be fairly superficial and often only involve the superficial to mid dermis. On histology they show thin-walled channels without erythrocytes that are lined by typical endothelial cells.7 Despite these differences, both clinically and histopathologically these lesions can appear similar to acquired microcystic lymphatic malformations. It is important to differentiate between these two entities, as atypical vascular lesions have a slightly higher rate of transformation into malignant tumors such as angiosarcomas.

Although angiosarcomas clinically may present as erythematous patches, plaques, or nodules similar to benign postradiation lesions, they tend to be more edematous than their benign counterparts.7,8 Two other clinical factors that can help determine if a postradiation lesion is benign or malignant are the size and time of onset of the lesion. Angiosarcomas tend to be much larger than benign postradiation lesions (median size, 7.5 cm) and tend to be more multifocal in nature.8,9 They also tend to arise on average 5 to 7 years after the initial radiation treatment, while benign lesions arise sooner.9