User login

Scientists use mRNA technology for universal flu vaccine

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Two years ago, when the first COVID-19 vaccines were administered, marked a game-changing moment in the fight against the pandemic. But it also was a significant moment for messenger RNA (mRNA) technology, which up until then had shown promise but had never quite broken through.

It’s the latest advance in a new age of vaccinology, where vaccines are easier and faster to produce, as well as more flexible and customizable.

“It’s all about covering the different flavors of flu in a way the current vaccines cannot do,” says Ofer Levy, MD, PhD, director of the Precision Vaccines Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is not involved with the UPenn research. “The mRNA platform is attractive here given its scalability and modularity, where you can mix and match different mRNAs.”

A recent paper, published in Science, reports successful animal tests of the experimental vaccine, which, like the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna COVID vaccines, relies on mRNA. But the idea is not to replace the annual flu shot. It’s to develop a primer that could be administered in childhood, readying the body’s B cells and T cells to react quickly if faced with a flu virus.

It’s all part of a National Institutes of Health–funded effort to develop a universal flu vaccine, with hopes of heading off future flu pandemics. Annual shots protect against flu subtypes known to spread in humans. But many subtypes circulate in animals, like birds and pigs, and occasionally jump to humans, causing pandemics.

“The current vaccines provide very little protection against these other subtypes,” says lead study author Scott Hensley, PhD, a professor of microbiology at UPenn. “We set out to make a vaccine that would provide some level of immunity against essentially every influenza subtype we know about.”

That’s 20 subtypes altogether. The unique properties of mRNA vaccines make immune responses against all those antigens possible, Dr. Hensley says.

Old-school vaccines introduce a weakened or dead bacteria or virus into the body, but mRNA vaccines use mRNA encoded with a protein from the virus. That’s the “spike” protein for COVID, and for the experimental vaccine, it’s hemagglutinin, the major protein found on the surface of all flu viruses.

Mice and ferrets that had never been exposed to the flu were given the vaccine and produced high levels of antibodies against all 20 flu subtypes. Vaccinated mice exposed to the exact strains in the vaccine stayed pretty healthy, while those exposed to strains not found in the vaccine got sick but recovered quickly and survived. Unvaccinated mice exposed to the flu strain died.

The vaccine seems to be able to “induce broad immunity against all the different influenza subtypes,” Dr. Hensley says, preventing severe illness if not infection overall.

Still, whether it could truly stave off a pandemic that hasn’t happened yet is hard to say, Dr. Levy cautions.

“We are going to need to better learn the molecular rules by which these vaccines protect,” he says.

But the UPenn team is forging ahead, with plans to test their vaccine in human adults in 2023 to determine safety, dosing, and antibody response.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM SCIENCE

Flu hospitalizations drop amid signs of an early peak

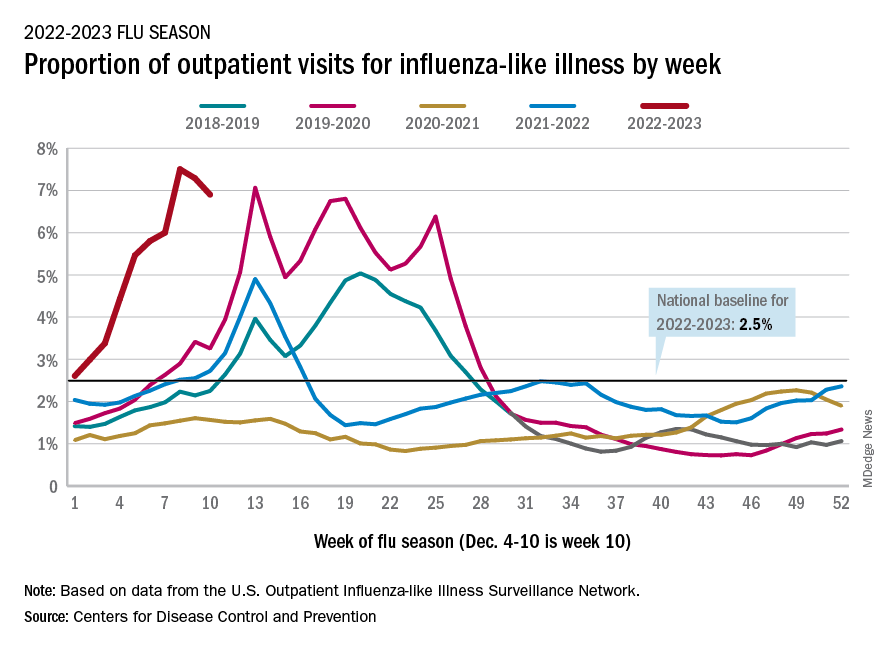

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

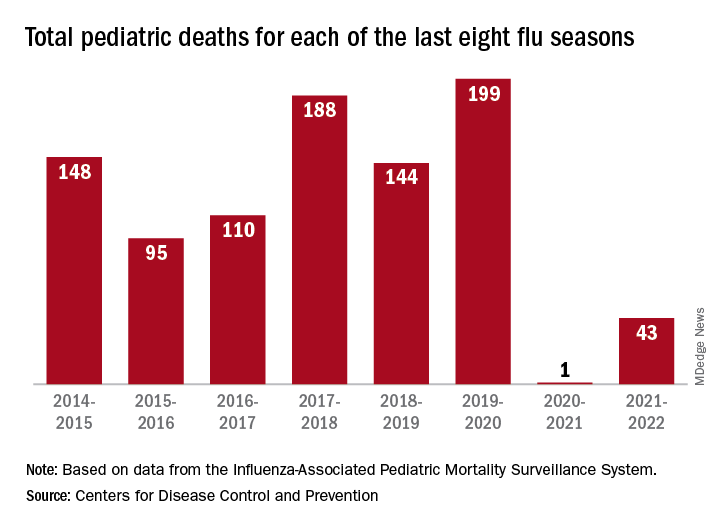

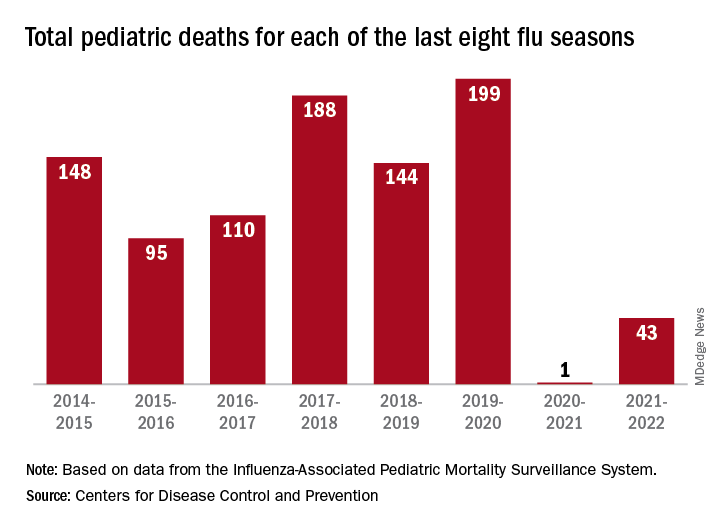

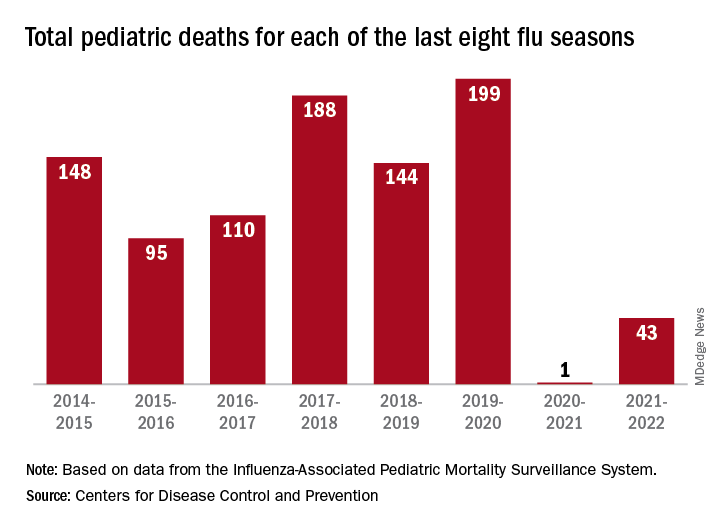

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

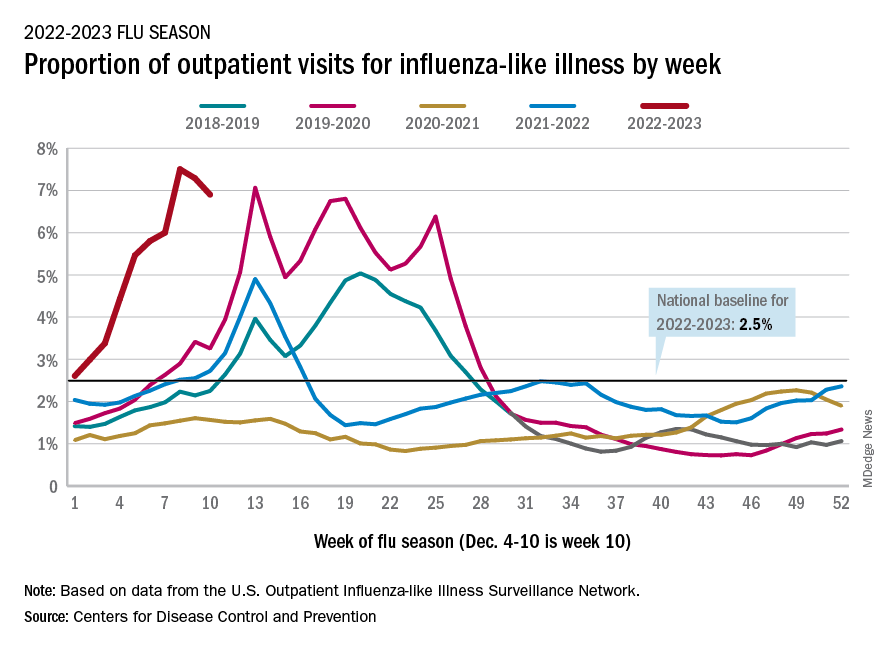

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

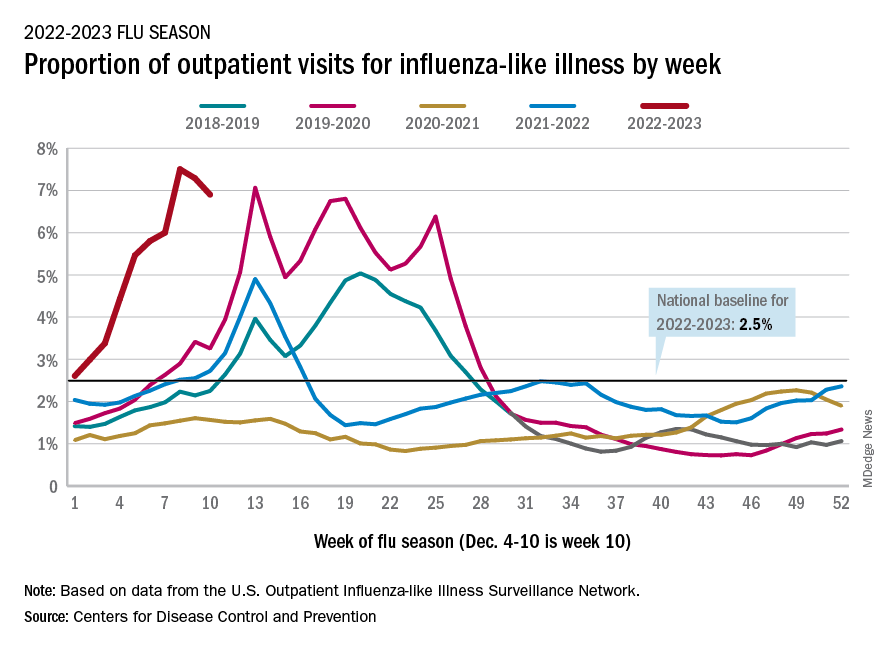

It’s beginning to look less like an epidemic as seasonal flu activity “appears to be declining in some areas,” according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declines in a few states and territories were enough to lower national activity, as measured by outpatient visits for influenza-like illness, for the second consecutive week. This reduced the weekly number of hospital admissions for the first time in the 2022-2023 season, according to the CDC influenza division’s weekly FluView report.

Flu-related hospital admissions slipped to about 23,500 during the week of Dec. 4-10, after topping 26,000 the week before, based on data reported by 5,000 hospitals from all states and territories.

which was still higher than any other December rate from all previous seasons going back to 2009-10, CDC data shows.

Visits for flu-like illness represented 6.9% of all outpatient visits reported to the CDC during the week of Dec. 4-10. The rate reached 7.5% during the last full week of November before dropping to 7.3%, the CDC said.

There were 28 states or territories with “very high” activity for the latest reporting week, compared with 32 the previous week. Eight states – Colorado, Idaho, Kentucky, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Washington – and New York City were at the very highest level on the CDC’s 1-13 scale of activity, compared with 14 areas the week before, the agency reported.

So far for the 2022-2023 season, the CDC estimated there have been at least 15 million cases of the flu, 150,000 hospitalizations, and 9,300 deaths. Among those deaths have been 30 reported in children, compared with 44 for the entire 2021-22 season and just 1 for 2020-21.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Hospital financial decisions play a role in the critical shortage of pediatric beds for RSV patients

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation in the fall of 2022 is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs – especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus – medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, MS, MBA, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100% full – and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Scott Krugman, MD, MS, vice chair of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va.; and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed – and still vulnerable – to viruses other than COVID for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Daniel Rauch, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health care providers – including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants – to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Dr. Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Megan Ranney, MD, MPH, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, R.I., including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Dr. Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Dr. Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Dr. Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Alex Kon, MD, a pediatric critical care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Mont., said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Wash., or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent 7 anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Dr. Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Krugman doubts the health care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Dr. Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation in the fall of 2022 is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs – especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus – medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, MS, MBA, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100% full – and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Scott Krugman, MD, MS, vice chair of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va.; and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed – and still vulnerable – to viruses other than COVID for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Daniel Rauch, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health care providers – including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants – to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Dr. Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Megan Ranney, MD, MPH, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, R.I., including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Dr. Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Dr. Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Dr. Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Alex Kon, MD, a pediatric critical care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Mont., said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Wash., or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent 7 anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Dr. Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Krugman doubts the health care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Dr. Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

The dire shortage of pediatric hospital beds plaguing the nation in the fall of 2022 is a byproduct of financial decisions made by hospitals over the past decade, as they shuttered children’s wards, which often operate in the red, and expanded the number of beds available for more profitable endeavors like joint replacements and cancer care.

To cope with the flood of young patients sickened by a sweeping convergence of nasty bugs – especially respiratory syncytial virus, influenza, and coronavirus – medical centers nationwide have deployed triage tents, delayed elective surgeries, and transferred critically ill children out of state.

A major factor in the bed shortage is a years-long trend among hospitals of eliminating pediatric units, which tend to be less profitable than adult units, said Mark Wietecha, MS, MBA, CEO of the Children’s Hospital Association. Hospitals optimize revenue by striving to keep their beds 100% full – and filled with patients whose conditions command generous insurance reimbursements.

“It really has to do with dollars,” said Scott Krugman, MD, MS, vice chair of pediatrics at the Herman and Walter Samuelson Children’s Hospital at Sinai in Baltimore. “Hospitals rely on high-volume, high-reimbursement procedures from good payers to make money. There’s no incentive for hospitals to provide money-losing services.”

The number of pediatric inpatient units in hospitals fell 19% from 2008 to 2018, according to a study published in 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. Just this year, hospitals have closed pediatric units in Boston and Springfield, Mass.; Richmond, Va.; and Tulsa, Okla.

The current surge in dangerous respiratory illnesses among children is yet another example of how COVID-19 has upended the health care system. The lockdowns and isolation that marked the first years of the pandemic left kids largely unexposed – and still vulnerable – to viruses other than COVID for two winters, and doctors are now essentially treating multiple years’ worth of respiratory ailments.

The pandemic also accelerated changes in the health care industry that have left many communities with fewer hospital beds available for children who are acutely ill, along with fewer doctors and nurses to care for them.

When intensive care units were flooded with older COVID patients in 2020, some hospitals began using children’s beds to treat adults. Many of those pediatric beds haven’t been restored, said Daniel Rauch, MD, chair of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ committee on hospital care.

In addition, the relentless pace of the pandemic has spurred more than 230,000 health care providers – including doctors, nurses, and physician assistants – to quit. Before the pandemic, about 10% of nurses left their jobs every year; the rate has risen to about 20%, Dr. Wietecha said. He estimates that pediatric hospitals are unable to maintain as many as 10% of their beds because of staffing shortages.

“There is just not enough space for all the kids who need beds,” said Megan Ranney, MD, MPH, who works in several emergency departments in Providence, R.I., including Hasbro Children’s Hospital. The number of children seeking emergency care in recent weeks was 25% higher than the hospital’s previous record.

“We have doctors who are cleaning beds so we can get children into them faster,” said Dr. Ranney, a deputy dean at Brown University’s School of Public Health.

There’s not great money in treating kids. About 40% of U.S. children are covered by Medicaid, a joint federal-state program for low-income patients and people with disabilities. Base Medicaid rates are typically more than 20% below those paid by Medicare, the government insurance program for older adults, and are even lower when compared with private insurance. While specialty care for a range of common adult procedures, from knee and hip replacements to heart surgeries and cancer treatments, generates major profits for medical centers, hospitals complain they typically lose money on inpatient pediatric care.

When Tufts Children’s Hospital closed 41 pediatric beds this summer, hospital officials assured residents that young patients could receive care at nearby Boston Children’s Hospital. Now, Boston Children’s is delaying some elective surgeries to make room for kids who are acutely ill.

Dr. Rauch noted that children’s hospitals, which specialize in treating rare and serious conditions such as pediatric cancer, cystic fibrosis, and heart defects, simply aren’t designed to handle this season’s crush of kids acutely ill with respiratory bugs.

Even before the autumn’s viral trifecta, pediatric units were straining to absorb rising numbers of young people in acute mental distress. Stories abound of children in mental crises being marooned for weeks in emergency departments while awaiting transfer to a pediatric psychiatric unit. On a good day, Dr. Ranney said, 20% of pediatric emergency room beds at Hasbro Children’s Hospital are occupied by children experiencing mental health issues.

In hopes of adding pediatric capacity, the American Academy of Pediatrics joined the Children’s Hospital Association last month in calling on the White House to declare a national emergency due to child respiratory infections and provide additional resources to help cover the costs of care. The Biden administration has said that the flexibility hospital systems and providers have been given during the pandemic to sidestep certain staffing requirements also applies to RSV and flu.

Doernbecher Children’s Hospital at Oregon Health & Science University has shifted to “crisis standards of care,” enabling intensive care nurses to treat more patients than they’re usually assigned. Hospitals in Atlanta, Pittsburgh, and Aurora, Colorado, meanwhile, have resorted to treating young patients in overflow tents in parking lots.

Alex Kon, MD, a pediatric critical care physician at Community Medical Center in Missoula, Mont., said providers there have made plans to care for older kids in the adult intensive care unit, and to divert ambulances to other facilities when necessary. With only three pediatric ICUs in the state, that means young patients may be flown as far as Seattle or Spokane, Wash., or Idaho.

Hollis Lillard took her 1-year-old son, Calder, to an Army hospital in Northern Virginia last month after he experienced several days of fever, coughing, and labored breathing. They spent 7 anguished hours in the emergency room before the hospital found an open bed and transferred them by ambulance to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Maryland.

With proper therapy and instructions for home care, Calder’s virus was readily treatable: He recovered after he was given oxygen and treated with steroids, which fight inflammation, and albuterol, which counteracts bronchospasms. He was discharged the next day.

Although hospitalizations for RSV are falling, rates remain well above the norm for this time of year. And hospitals may not get much relief.

People can be infected with RSV more than once a year, and Dr. Krugman worries about a resurgence in the months to come. Because of the coronavirus, which competes with other viruses, “the usual seasonal pattern of viruses has gone out the window,” he said.

Like RSV, influenza arrived early this season. Both viruses usually peak around January. Three strains of flu are circulating and have caused an estimated 8.7 million illnesses, 78,000 hospitalizations, and 4,500 deaths, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Krugman doubts the health care industry will learn any quick lessons from the current crisis. “Unless there is a radical change in how we pay for pediatric hospital care,” Dr. Krugman said, “the bed shortage is only going to get worse.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

RSV surge stuns parents and strains providers, but doctors offer help

RSV cases peaked in mid-November, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, with RSV-associated hospitalizations in the United States among patients 0-4 years having maxed out five times higher than they were at the same time in 2021. These surges strained providers and left parents scrambling for care. Fortunately, pediatric hospitalizations appear to be subsiding.

In interviews, the parents of the child who had a severe case of RSV reflected on their son’s bout with the illness, and doctors described challenges to dealing with the surge in RSV cases this season. The physicians also offered advice on how recognize and respond to future cases of the virus.

Sebastian Witt’s story

“I didn’t even know what RSV was,” said Malte Witt, whose son, Sebastian, 2, was recently hospitalized for RSV in Denver.

Mr. Witt and his wife, Emily Witt, both 32, thought they were dealing with a typical cold until Sebastian’s condition dramatically deteriorated about 36 hours after symptom onset.

“He basically just slumped over and collapsed, coughing uncontrollably,” Mr. Witt said in an interview. “He couldn’t catch his breath.”

The Witts rushed Sebastian to the ED at Children’s Hospital Colorado, expecting to see a doctor immediately. Instead, they spent the night in an overcrowded waiting room alongside many other families in the same situation.

“There was no room for anyone to sit anywhere,” Mr. Witt said. “There were people sitting on the floor. I counted maybe six children hooked up to oxygen when we walked in.”

After waiting approximately 45 minutes, a nurse checked Sebastian’s oxygen saturation. The readings were 79%-83%. This range is significantly below thresholds for supplemental oxygen described by most pediatric guidelines, which range from 90 to 94%.

The nurse connected Sebastian to bottled oxygen in the waiting room, and a recheck 4 hours later showed that his oxygen saturation had improved.

But the improvement didn’t last.

“At roughly hour 10 in the waiting room – it was 4 in the morning – you could tell that Seb was exhausted, really not acting like himself,” Mr. Witt said. “We thought maybe it’s just late at night, he hasn’t really slept. But then Emily noticed that his oxygen tank had run out.”

Mr. Witt told a nurse, and after another check revealed low oxygen saturation, Sebastian was finally admitted.

Early RSV surge strains pediatric providers

With RSV-associated hospitalizations peaking at 48 per 100,000 children, Colorado has been among the states hardest hit by the virus. New Mexico – where hospitalizations peaked at 56.4 per 100,000 children – comes in second. Even in states like California, where hospitalization rates have been almost 10-fold lower than New Mexico, pediatric providers have been stretched to their limits.

“Many hospitals are really being overwhelmed with admissions for RSV, both routine RSV – relatively mild hospitalizations with bronchiolitis – as well as kids in the ICU with more severe cases,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, said in an interview.

Dr. Blumberg believes the severity of the 2022-2023 RSV season is likely COVID related.

“All community-associated respiratory viral infections are out of whack because of the pandemic, and all the masking and social distancing that was occurring,” he said.

This may also explain why older kids are coming down with more severe cases of RSV.

“Some children are getting RSV for the first time as older children,” Dr. Blumberg said, noting that, historically, most children were infected in the first 2 years of life. “There are reports of children 3 or 4 years of age being admitted with their first episode of RSV because of the [COVID] pandemic.”

This year’s RSV season is also notable for arriving early, potentially catching the community off guard, according to Jennifer D. Kusma, MD, a primary care pediatrician at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

“People who should have been protected often weren’t protected yet,” Dr. Kusma said in an interview.

Treatments new, old, and unproven

On Nov. 17, in the midst of the RSV surge, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued updated guidance for palivizumab, an RSV-targeting monoclonal antibody labeled for children at risk of severe RSV, including those with pre-existing lung or heart conditions, and infants with a history of premature birth (less than or equal to 35 weeks’ gestational age).

“If RSV disease activity persists at high levels in a given region through the fall and winter, the AAP supports providing more than five consecutive doses of palivizumab to eligible children,” the update stated.

Insurance companies appear to be responding in kind, covering additional doses for children in need.

“[Payers] have agreed that, if [palivizumab] needs to be given for an additional month or 2 or 3, then they’re making a commitment that they’ll reimburse hospitals for providing that,” Dr. Blumberg said.

For ineligible patients, such as Sebastian, who was born prematurely at 36 weeks – 1 week shy of the label requirement – treatment relies upon supportive care with oxygen and IV fluids.

At home, parents are left with simpler options.

Dr. Blumberg and Dr. Kusma recommended keeping children hydrated, maintaining humidified air, and using saline nose drops with bulb suction to clear mucus.

In the Witts’ experience, that last step may be easier said than done.

“Every time a nurse would walk into the room, Sebastian would yell: ‘Go away, doctor! I don’t want snot sucker!’” Mr. Witt said.

“If you over snot-suck, that’s really uncomfortable for the kid, and really hard for you,” Ms. Witt said. “And it doesn’t make much of a difference. It’s just very hard to find a middle ground, where you’re helping and keeping them comfortable.”

Some parents are turning to novel strategies, such as nebulized hypertonic saline, currently marketed on Amazon for children with RSV.

Although the AAP offers a weak recommendation for nebulized hypertonic saline in children hospitalized more than 72 hours, they advise against it in the emergency setting, citing inconsistent findings in clinical trials.

To any parents tempted by thousands of positive Amazon reviews, Dr. Blumberg said, “I wouldn’t waste my money on that.”

Dr. Kusma agreed.

“[Nebulized hypertonic saline] can be irritating,” she said. “It’s saltwater, essentially. If a parent is in the position where they’re worried about their child’s breathing to the point that they think they need to use it, I would err on the side of calling your pediatrician and being seen.”

Going in, coming home

Dr. Kusma said parents should seek medical attention if a child is breathing faster and working harder to get air. Increased work of breathing is characterized by pulling of the skin at the notch where the throat meets the chest bone (tracheal tugging), and flattening of the belly that makes the ribcage more prominent.

Mr. Witt saw these signs in Sebastian. He knew they were significant, because a friend who is a nurse had previously shown him some examples of children who exhibited these symptoms online.

“That’s how I knew that things were actually really dangerous,” Mr. Witt said. “Had she not shown me those videos a month and a half before this happened, I don’t know that we would have hit the alarm bell as quickly as we did.”

After spending their second night and the following day in a cramped preoperative room converted to manage overflow from the emergency department, Sebastian’s condition improved, and he was discharged. The Witts are relieved to be home, but frustrations from their ordeal remain, especially considering the estimated $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs they expect to pay.

“How is this our health care system?” Ms. Witt asked. “This is unbelievable.”

An optimistic outlook

RSV seasons typically demonstrate a clear peak, followed by a decline through the rest of the season, suggesting better times lie ahead; however, this season has been anything but typical.

“I’m hopeful that it will just go away and stay away,” Dr. Kusma said, citing this trend. “But I can’t know for sure.”

To anxious parents, Dr. Blumberg offered an optimistic view of RSV seasons to come.

“There’s hope,” he said. “There are vaccines that are being developed that are very close to FDA approval. So, it’s possible that this time next year, we might have widespread RSV vaccination available for children so that we don’t have to go through this nightmare again.”

Dr. Blumberg and Dr. Kusma disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

RSV cases peaked in mid-November, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, with RSV-associated hospitalizations in the United States among patients 0-4 years having maxed out five times higher than they were at the same time in 2021. These surges strained providers and left parents scrambling for care. Fortunately, pediatric hospitalizations appear to be subsiding.

In interviews, the parents of the child who had a severe case of RSV reflected on their son’s bout with the illness, and doctors described challenges to dealing with the surge in RSV cases this season. The physicians also offered advice on how recognize and respond to future cases of the virus.

Sebastian Witt’s story

“I didn’t even know what RSV was,” said Malte Witt, whose son, Sebastian, 2, was recently hospitalized for RSV in Denver.

Mr. Witt and his wife, Emily Witt, both 32, thought they were dealing with a typical cold until Sebastian’s condition dramatically deteriorated about 36 hours after symptom onset.

“He basically just slumped over and collapsed, coughing uncontrollably,” Mr. Witt said in an interview. “He couldn’t catch his breath.”

The Witts rushed Sebastian to the ED at Children’s Hospital Colorado, expecting to see a doctor immediately. Instead, they spent the night in an overcrowded waiting room alongside many other families in the same situation.

“There was no room for anyone to sit anywhere,” Mr. Witt said. “There were people sitting on the floor. I counted maybe six children hooked up to oxygen when we walked in.”

After waiting approximately 45 minutes, a nurse checked Sebastian’s oxygen saturation. The readings were 79%-83%. This range is significantly below thresholds for supplemental oxygen described by most pediatric guidelines, which range from 90 to 94%.

The nurse connected Sebastian to bottled oxygen in the waiting room, and a recheck 4 hours later showed that his oxygen saturation had improved.

But the improvement didn’t last.

“At roughly hour 10 in the waiting room – it was 4 in the morning – you could tell that Seb was exhausted, really not acting like himself,” Mr. Witt said. “We thought maybe it’s just late at night, he hasn’t really slept. But then Emily noticed that his oxygen tank had run out.”

Mr. Witt told a nurse, and after another check revealed low oxygen saturation, Sebastian was finally admitted.

Early RSV surge strains pediatric providers

With RSV-associated hospitalizations peaking at 48 per 100,000 children, Colorado has been among the states hardest hit by the virus. New Mexico – where hospitalizations peaked at 56.4 per 100,000 children – comes in second. Even in states like California, where hospitalization rates have been almost 10-fold lower than New Mexico, pediatric providers have been stretched to their limits.

“Many hospitals are really being overwhelmed with admissions for RSV, both routine RSV – relatively mild hospitalizations with bronchiolitis – as well as kids in the ICU with more severe cases,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, said in an interview.

Dr. Blumberg believes the severity of the 2022-2023 RSV season is likely COVID related.

“All community-associated respiratory viral infections are out of whack because of the pandemic, and all the masking and social distancing that was occurring,” he said.

This may also explain why older kids are coming down with more severe cases of RSV.

“Some children are getting RSV for the first time as older children,” Dr. Blumberg said, noting that, historically, most children were infected in the first 2 years of life. “There are reports of children 3 or 4 years of age being admitted with their first episode of RSV because of the [COVID] pandemic.”

This year’s RSV season is also notable for arriving early, potentially catching the community off guard, according to Jennifer D. Kusma, MD, a primary care pediatrician at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

“People who should have been protected often weren’t protected yet,” Dr. Kusma said in an interview.

Treatments new, old, and unproven

On Nov. 17, in the midst of the RSV surge, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued updated guidance for palivizumab, an RSV-targeting monoclonal antibody labeled for children at risk of severe RSV, including those with pre-existing lung or heart conditions, and infants with a history of premature birth (less than or equal to 35 weeks’ gestational age).

“If RSV disease activity persists at high levels in a given region through the fall and winter, the AAP supports providing more than five consecutive doses of palivizumab to eligible children,” the update stated.

Insurance companies appear to be responding in kind, covering additional doses for children in need.

“[Payers] have agreed that, if [palivizumab] needs to be given for an additional month or 2 or 3, then they’re making a commitment that they’ll reimburse hospitals for providing that,” Dr. Blumberg said.

For ineligible patients, such as Sebastian, who was born prematurely at 36 weeks – 1 week shy of the label requirement – treatment relies upon supportive care with oxygen and IV fluids.

At home, parents are left with simpler options.

Dr. Blumberg and Dr. Kusma recommended keeping children hydrated, maintaining humidified air, and using saline nose drops with bulb suction to clear mucus.

In the Witts’ experience, that last step may be easier said than done.

“Every time a nurse would walk into the room, Sebastian would yell: ‘Go away, doctor! I don’t want snot sucker!’” Mr. Witt said.

“If you over snot-suck, that’s really uncomfortable for the kid, and really hard for you,” Ms. Witt said. “And it doesn’t make much of a difference. It’s just very hard to find a middle ground, where you’re helping and keeping them comfortable.”

Some parents are turning to novel strategies, such as nebulized hypertonic saline, currently marketed on Amazon for children with RSV.

Although the AAP offers a weak recommendation for nebulized hypertonic saline in children hospitalized more than 72 hours, they advise against it in the emergency setting, citing inconsistent findings in clinical trials.

To any parents tempted by thousands of positive Amazon reviews, Dr. Blumberg said, “I wouldn’t waste my money on that.”

Dr. Kusma agreed.

“[Nebulized hypertonic saline] can be irritating,” she said. “It’s saltwater, essentially. If a parent is in the position where they’re worried about their child’s breathing to the point that they think they need to use it, I would err on the side of calling your pediatrician and being seen.”

Going in, coming home

Dr. Kusma said parents should seek medical attention if a child is breathing faster and working harder to get air. Increased work of breathing is characterized by pulling of the skin at the notch where the throat meets the chest bone (tracheal tugging), and flattening of the belly that makes the ribcage more prominent.

Mr. Witt saw these signs in Sebastian. He knew they were significant, because a friend who is a nurse had previously shown him some examples of children who exhibited these symptoms online.

“That’s how I knew that things were actually really dangerous,” Mr. Witt said. “Had she not shown me those videos a month and a half before this happened, I don’t know that we would have hit the alarm bell as quickly as we did.”

After spending their second night and the following day in a cramped preoperative room converted to manage overflow from the emergency department, Sebastian’s condition improved, and he was discharged. The Witts are relieved to be home, but frustrations from their ordeal remain, especially considering the estimated $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs they expect to pay.

“How is this our health care system?” Ms. Witt asked. “This is unbelievable.”

An optimistic outlook

RSV seasons typically demonstrate a clear peak, followed by a decline through the rest of the season, suggesting better times lie ahead; however, this season has been anything but typical.

“I’m hopeful that it will just go away and stay away,” Dr. Kusma said, citing this trend. “But I can’t know for sure.”

To anxious parents, Dr. Blumberg offered an optimistic view of RSV seasons to come.

“There’s hope,” he said. “There are vaccines that are being developed that are very close to FDA approval. So, it’s possible that this time next year, we might have widespread RSV vaccination available for children so that we don’t have to go through this nightmare again.”

Dr. Blumberg and Dr. Kusma disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

RSV cases peaked in mid-November, according to the latest Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, with RSV-associated hospitalizations in the United States among patients 0-4 years having maxed out five times higher than they were at the same time in 2021. These surges strained providers and left parents scrambling for care. Fortunately, pediatric hospitalizations appear to be subsiding.

In interviews, the parents of the child who had a severe case of RSV reflected on their son’s bout with the illness, and doctors described challenges to dealing with the surge in RSV cases this season. The physicians also offered advice on how recognize and respond to future cases of the virus.

Sebastian Witt’s story

“I didn’t even know what RSV was,” said Malte Witt, whose son, Sebastian, 2, was recently hospitalized for RSV in Denver.

Mr. Witt and his wife, Emily Witt, both 32, thought they were dealing with a typical cold until Sebastian’s condition dramatically deteriorated about 36 hours after symptom onset.

“He basically just slumped over and collapsed, coughing uncontrollably,” Mr. Witt said in an interview. “He couldn’t catch his breath.”

The Witts rushed Sebastian to the ED at Children’s Hospital Colorado, expecting to see a doctor immediately. Instead, they spent the night in an overcrowded waiting room alongside many other families in the same situation.

“There was no room for anyone to sit anywhere,” Mr. Witt said. “There were people sitting on the floor. I counted maybe six children hooked up to oxygen when we walked in.”

After waiting approximately 45 minutes, a nurse checked Sebastian’s oxygen saturation. The readings were 79%-83%. This range is significantly below thresholds for supplemental oxygen described by most pediatric guidelines, which range from 90 to 94%.

The nurse connected Sebastian to bottled oxygen in the waiting room, and a recheck 4 hours later showed that his oxygen saturation had improved.

But the improvement didn’t last.

“At roughly hour 10 in the waiting room – it was 4 in the morning – you could tell that Seb was exhausted, really not acting like himself,” Mr. Witt said. “We thought maybe it’s just late at night, he hasn’t really slept. But then Emily noticed that his oxygen tank had run out.”

Mr. Witt told a nurse, and after another check revealed low oxygen saturation, Sebastian was finally admitted.

Early RSV surge strains pediatric providers

With RSV-associated hospitalizations peaking at 48 per 100,000 children, Colorado has been among the states hardest hit by the virus. New Mexico – where hospitalizations peaked at 56.4 per 100,000 children – comes in second. Even in states like California, where hospitalization rates have been almost 10-fold lower than New Mexico, pediatric providers have been stretched to their limits.

“Many hospitals are really being overwhelmed with admissions for RSV, both routine RSV – relatively mild hospitalizations with bronchiolitis – as well as kids in the ICU with more severe cases,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, said in an interview.

Dr. Blumberg believes the severity of the 2022-2023 RSV season is likely COVID related.

“All community-associated respiratory viral infections are out of whack because of the pandemic, and all the masking and social distancing that was occurring,” he said.

This may also explain why older kids are coming down with more severe cases of RSV.

“Some children are getting RSV for the first time as older children,” Dr. Blumberg said, noting that, historically, most children were infected in the first 2 years of life. “There are reports of children 3 or 4 years of age being admitted with their first episode of RSV because of the [COVID] pandemic.”

This year’s RSV season is also notable for arriving early, potentially catching the community off guard, according to Jennifer D. Kusma, MD, a primary care pediatrician at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago.

“People who should have been protected often weren’t protected yet,” Dr. Kusma said in an interview.

Treatments new, old, and unproven

On Nov. 17, in the midst of the RSV surge, the American Academy of Pediatrics issued updated guidance for palivizumab, an RSV-targeting monoclonal antibody labeled for children at risk of severe RSV, including those with pre-existing lung or heart conditions, and infants with a history of premature birth (less than or equal to 35 weeks’ gestational age).

“If RSV disease activity persists at high levels in a given region through the fall and winter, the AAP supports providing more than five consecutive doses of palivizumab to eligible children,” the update stated.

Insurance companies appear to be responding in kind, covering additional doses for children in need.

“[Payers] have agreed that, if [palivizumab] needs to be given for an additional month or 2 or 3, then they’re making a commitment that they’ll reimburse hospitals for providing that,” Dr. Blumberg said.

For ineligible patients, such as Sebastian, who was born prematurely at 36 weeks – 1 week shy of the label requirement – treatment relies upon supportive care with oxygen and IV fluids.

At home, parents are left with simpler options.

Dr. Blumberg and Dr. Kusma recommended keeping children hydrated, maintaining humidified air, and using saline nose drops with bulb suction to clear mucus.

In the Witts’ experience, that last step may be easier said than done.

“Every time a nurse would walk into the room, Sebastian would yell: ‘Go away, doctor! I don’t want snot sucker!’” Mr. Witt said.

“If you over snot-suck, that’s really uncomfortable for the kid, and really hard for you,” Ms. Witt said. “And it doesn’t make much of a difference. It’s just very hard to find a middle ground, where you’re helping and keeping them comfortable.”

Some parents are turning to novel strategies, such as nebulized hypertonic saline, currently marketed on Amazon for children with RSV.

Although the AAP offers a weak recommendation for nebulized hypertonic saline in children hospitalized more than 72 hours, they advise against it in the emergency setting, citing inconsistent findings in clinical trials.

To any parents tempted by thousands of positive Amazon reviews, Dr. Blumberg said, “I wouldn’t waste my money on that.”

Dr. Kusma agreed.

“[Nebulized hypertonic saline] can be irritating,” she said. “It’s saltwater, essentially. If a parent is in the position where they’re worried about their child’s breathing to the point that they think they need to use it, I would err on the side of calling your pediatrician and being seen.”

Going in, coming home

Dr. Kusma said parents should seek medical attention if a child is breathing faster and working harder to get air. Increased work of breathing is characterized by pulling of the skin at the notch where the throat meets the chest bone (tracheal tugging), and flattening of the belly that makes the ribcage more prominent.

Mr. Witt saw these signs in Sebastian. He knew they were significant, because a friend who is a nurse had previously shown him some examples of children who exhibited these symptoms online.

“That’s how I knew that things were actually really dangerous,” Mr. Witt said. “Had she not shown me those videos a month and a half before this happened, I don’t know that we would have hit the alarm bell as quickly as we did.”

After spending their second night and the following day in a cramped preoperative room converted to manage overflow from the emergency department, Sebastian’s condition improved, and he was discharged. The Witts are relieved to be home, but frustrations from their ordeal remain, especially considering the estimated $5,000 in out-of-pocket costs they expect to pay.

“How is this our health care system?” Ms. Witt asked. “This is unbelievable.”

An optimistic outlook

RSV seasons typically demonstrate a clear peak, followed by a decline through the rest of the season, suggesting better times lie ahead; however, this season has been anything but typical.

“I’m hopeful that it will just go away and stay away,” Dr. Kusma said, citing this trend. “But I can’t know for sure.”

To anxious parents, Dr. Blumberg offered an optimistic view of RSV seasons to come.

“There’s hope,” he said. “There are vaccines that are being developed that are very close to FDA approval. So, it’s possible that this time next year, we might have widespread RSV vaccination available for children so that we don’t have to go through this nightmare again.”

Dr. Blumberg and Dr. Kusma disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Experts explain the ‘perfect storm’ of rampant RSV and flu

Headlines over the past few weeks are ringing the alarm about earlier and more serious influenza (flu) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) outbreaks compared with previous years. Add COVID-19 to the mix and you have a dangerous mash of viruses that have many experts calling for caution and searching for explanations.

RSV and the flu “are certainly getting more attention, and they’re getting more attention for two reasons,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“The first is that they’re both extraordinarily early. The second is that they’re both out there spreading very, very rapidly,” he told this news organization.

RSV usually follows a seasonal pattern with cases peaking in January and February. Both viruses tend to hit different regions of the country at different times, and that’s not the case in 2022.

“This is particularly striking for RSV, which usually doesn’t affect the entire country simultaneously,” Dr. Schaffner said.

“Yes, RSV is causing many more hospitalizations and earlier than any previously recorded season in the U.S.,” according to figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on RSV hospitalizations, said Kevin Messacar, MD, PhD, associate professor at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

Although there could be some increase in diagnoses because of increased awareness, the jump in RSV and flu cases “is a real phenomenon for multiple reasons,” said Peter Chin-Hong, MD, professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco.

With fewer COVID-related restrictions, people are moving around more. Also, during fall and winter, people tend to gather indoors. Colder temperatures and lower humidity contribute as well, Dr. Chin-Hong said, because “the droplets are just simply lighter.

“I think those are all factors,” he told this news organization.

Paul Auwaerter, MD, agreed that there are likely multiple causes for the unusual timing and severity of RSV and flu this year.

“Change in behaviors is a leading cause,” said the clinical director for the division of infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. More people returning to the workplace and children going to school without masks are examples, he added.

Less exposure to these three viruses also means there was less immune boosting among existing populations, he said. This can lead to “larger susceptible populations, especially infants and younger children, due to the relative absence of circulating virus in past years.”

A leading theory

Are we paying a price now for people following the edicts from officials to mask up, stand apart, and take other personal and public health precautions during the COVID-19 pandemic?

It’s possible, but that may not be the whole story.

“When it comes to RSV, I think that theory of isolation, social distancing, mask wearing, and not attending schools is a very valid one,” Dr. Schaffner said. “That’s everybody’s favorite [reason].”

He said he is confident that the jump in RSV cases is being driven by previous COVID public health protections. However, he’s “a little more cautious about influenza, in part because influenza is so variable.

“Like people in influenza say, if you’ve seen one influenza season, you’ve seen one influenza season,” Dr. Schaffner said.

“There’s a lot of debate,” he added. “Nobody can say definitively whether the immune deficit or debt is a consequence of not being stimulated and restimulated by the influenza virus over the past two seasons.”

‘A perfect storm’

“Now you kind of have the perfect storm,” Dr. Chin-Hong said. “It’s not a good situation for COVID with the variants that are emerging. For influenza, not having seen a lot of influenza the last 2 years, we’re probably more susceptible to getting infected.”

RSV cases rose during summer 2021, but now the weather is colder, and people are interacting more closely. “And it’s very, very transmissible,” he said.

Dr. Chin-Hong also predicted that “even though we don’t have a lot of COVID now, COVID will probably pick up.”

The rise in RSV was unexpected by some experts. “This early influenza is also a bit of a surprise and may be influenced by the fact that lots of us are going back and seeing each other again close-to-close, face-to-face in many enclosed environments,” Dr. Schaffner said.

He estimated the 2022-2023 flu season started 4-6 weeks early “and it’s taken off like a rocket. It started in the Southeast, quickly went to the Southwest and up the East Coast. Now it’s moving dramatically through the Midwest and will continue. It’s quite sure to hit the West Coast if it isn’t there already.”

A phenomenon by any other name

Some are calling the situation an “immunity debt,” while others dub it an “immunity pause” or an “immunity deficit.” Many physicians and immunologists have taken to social media to push back on the term “immunity debt,” saying it’s a mischaracterization that is being used to vilify COVID precautions, such as masking, social distancing, and other protective measures taken during the pandemic.

“I prefer the term ‘immunity gap’ ... which is more established in the epidemiology literature, especially given the politicization of the term ‘immunity debt’ by folks recently,” Dr. Messacar said.

“To me, the immunity gap is a scientific observation, not a political argument,” he added.

In a July 2022 publication in The Lancet, Dr. Messacar and his colleagues stated that “decreased exposure to endemic viruses created an immunity gap – a group of susceptible individuals who avoided infection and therefore lack pathogen-specific immunity to protect against future infection. Decreases in childhood vaccinations with pandemic disruptions to health care delivery contribute to this immunity gap for vaccine-preventable diseases, such as influenza,measles, and polio.”

The researchers noted that because of isolation during the pandemic, older children and newborns are being exposed to RSV for the first time. Returning to birthday parties, playing with friends, and going to school without masks means “children are being exposed to RSV, and that’s likely the reason that RSV is moving early and very, very substantially through this now expanded pool of susceptible children,” Dr. Schaffner said.

How likely are coinfections?

With peaks in RSV, flu, and COVID-19 cases each predicted in the coming months, how likely is it that someone could get sick with more than one infection at the same time?

Early in the pandemic, coinfection with COVID and the flu was reported in people at some centers on the West Coast, Dr. Auwaerter said. Now, however, “the unpredictable nature of the Omicron subvariants and the potential for further change, along with the never-before-seen significant lessening of influenza over 2 years, leave little for predictability.

“I do think it is less likely, given the extent of immunity now to SARS-CoV-2 in the population,” Dr. Auwaerter said.

“I most worry about viral coinfections ... in people with suppressed immune systems if we have high community rates of the SARS-CoV-2 and influenza circulating this fall and winter,” he added.

Studies during the pandemic suggest that coinfection with the SARS-CoV-2 virus and another respiratory virus were either rare or nonexistent.

Dr. Schaffner said these findings align with his experience at Vanderbilt University, which is part of a CDC-sponsored network that tracks laboratory-confirmed RSV, flu, and COVID cases among people in the hospital. “Coinfections are, at least to date, very unusual.”

There needs to be an asterisk next to that, Dr. Schaffner added. “Looking back over the last 2 years, we’ve had very little influenza, and we’ve had curtailed RSV seasons. So there hasn’t been a whole lot of opportunity for dual infections to occur.

“So this year may be more revelatory as we go forward,” he said.

Future concerns

The future is uncertain, Dr. Messacar and colleagues wrote in The Lancet: “Crucially, the patterns of these returning viral outbreaks have been heterogeneous across locations, populations, and pathogens, making predictions and preparations challenging.”

Dr. Chin-Hong used a horse race analogy to illustrate the situation now and going forward. RSV is the front-running horse, and influenza is running behind but trying to catch up. “And then COVID is the dark horse. It’s trailing the race right now – but all these variants are giving the horse extra supplements.

“And the COVID horse is probably going to be very competitive with the front-runner,” he said.

“We’re just at the beginning of the race right now,” Dr. Chin-Hong said, “so that’s why we’re worried that these three [viruses] will be even more pronounced come later in the year.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Headlines over the past few weeks are ringing the alarm about earlier and more serious influenza (flu) and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) outbreaks compared with previous years. Add COVID-19 to the mix and you have a dangerous mash of viruses that have many experts calling for caution and searching for explanations.

RSV and the flu “are certainly getting more attention, and they’re getting more attention for two reasons,” said William Schaffner, MD, professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn.

“The first is that they’re both extraordinarily early. The second is that they’re both out there spreading very, very rapidly,” he told this news organization.

RSV usually follows a seasonal pattern with cases peaking in January and February. Both viruses tend to hit different regions of the country at different times, and that’s not the case in 2022.

“This is particularly striking for RSV, which usually doesn’t affect the entire country simultaneously,” Dr. Schaffner said.

“Yes, RSV is causing many more hospitalizations and earlier than any previously recorded season in the U.S.,” according to figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on RSV hospitalizations, said Kevin Messacar, MD, PhD, associate professor at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora, and a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital Colorado in Aurora.

Although there could be some increase in diagnoses because of increased awareness, the jump in RSV and flu cases “is a real phenomenon for multiple reasons,” said Peter Chin-Hong, MD, professor in the division of infectious diseases at the University of California, San Francisco.

With fewer COVID-related restrictions, people are moving around more. Also, during fall and winter, people tend to gather indoors. Colder temperatures and lower humidity contribute as well, Dr. Chin-Hong said, because “the droplets are just simply lighter.

“I think those are all factors,” he told this news organization.

Paul Auwaerter, MD, agreed that there are likely multiple causes for the unusual timing and severity of RSV and flu this year.

“Change in behaviors is a leading cause,” said the clinical director for the division of infectious diseases at the Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore. More people returning to the workplace and children going to school without masks are examples, he added.

Less exposure to these three viruses also means there was less immune boosting among existing populations, he said. This can lead to “larger susceptible populations, especially infants and younger children, due to the relative absence of circulating virus in past years.”

A leading theory

Are we paying a price now for people following the edicts from officials to mask up, stand apart, and take other personal and public health precautions during the COVID-19 pandemic?

It’s possible, but that may not be the whole story.

“When it comes to RSV, I think that theory of isolation, social distancing, mask wearing, and not attending schools is a very valid one,” Dr. Schaffner said. “That’s everybody’s favorite [reason].”

He said he is confident that the jump in RSV cases is being driven by previous COVID public health protections. However, he’s “a little more cautious about influenza, in part because influenza is so variable.

“Like people in influenza say, if you’ve seen one influenza season, you’ve seen one influenza season,” Dr. Schaffner said.