User login

Onstep hernia repair decreased postop pain during sexual activity

The Onstep technique for inguinal hernia repair is associated with a lower incidence of postoperative pain during sexual activity than the Lichtenstein surgical technique, according to a paper published online in Surgery.

This study was a part of the Onli trial, the objective of which was to evaluate chronic pain and sexual dysfunction after inguinal hernia repair involving mesh fixation with sutures (Lichtenstein), compared with no mesh fixation (Onstep). The investigators reported the findings of a large study: 20.8% of inguinal repair patients experienced pain during sexual activity 1.4-1.7 years after their operation (Pain. 2006;122:258-63).

“The Onstep technique could be considered when surgeons and patients are discussing the optimal technique for repair of an inguinal hernia,” wrote Kristoffer Andresen, MD, of the University of Copenhagen, and his coauthors. “If the patient has pain during sexual activity as part of the complaint from the hernia, the Onstep technique seems to have a greater chance of removing this pain and alleviating the complaints.”

Among the 17 patients in the Onstep group who experienced postoperative pain during sexual activity, 8 had experienced preoperative pain during sexual activity and 7 had not. In the Lichtenstein group, 14 of the 30 patients who experienced postoperative pain had experienced preoperative pain, 14 had not. The remaining patients in both groups reported not having sexual activity before surgery or declined to answer.

The Lichtenstein technique was associated with new pain in 14 of the 70 patients (20%) while 7 of the 74 patients (9%) in the Onstep group reported new pain after surgery.

“For patients who experienced pain during sexual activity preoperatively, the Onstep technique removed the pain during sexual activity in the majority of patients while still resulting in few new cases,” the authors wrote.

Among the Lichtenstein group, 20 patients experienced pain from the surgical scar, compared with 7 patients in the Onstep group.

When asked about the degree of impairment of sexual function because of the postoperative pain, four patients in the Lichtenstein group said they had moderate to severe impairment, but none in the Onstep group reported that level of impairment.

Commenting on the possible mechanisms that might result in pain during sexual activity after hernia repair, the authors noted that mesh has been found to shrink from a mass around the vas deferens after a Lichtenstein repair. Previous studies have also found sutures around the iliohypogastric and the ilioinguinal nerves, which could also result in some pain.

“Because the mesh in the Onstep technique is not fixed with sutures, the risk of capturing nerves during the fixation of mesh is nonexistent,” they wrote. “There could, however, still be a risk of scar tissue and mesh shrinkage.”

PolySoft mesh (Bard Davol) was used for the Lichtenstein group and SoftMesh (Bard Davol) was used for the Onstep group.

In the 6 months’ follow-up period, two patients in the Lichtenstein group and one patient in the Onstep group experienced a recurrence of their hernia.

Three authors reported personal fees and travel grants from private industry – including Bard Medical – outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

The Onstep technique for inguinal hernia repair is associated with a lower incidence of postoperative pain during sexual activity than the Lichtenstein surgical technique, according to a paper published online in Surgery.

This study was a part of the Onli trial, the objective of which was to evaluate chronic pain and sexual dysfunction after inguinal hernia repair involving mesh fixation with sutures (Lichtenstein), compared with no mesh fixation (Onstep). The investigators reported the findings of a large study: 20.8% of inguinal repair patients experienced pain during sexual activity 1.4-1.7 years after their operation (Pain. 2006;122:258-63).

“The Onstep technique could be considered when surgeons and patients are discussing the optimal technique for repair of an inguinal hernia,” wrote Kristoffer Andresen, MD, of the University of Copenhagen, and his coauthors. “If the patient has pain during sexual activity as part of the complaint from the hernia, the Onstep technique seems to have a greater chance of removing this pain and alleviating the complaints.”

Among the 17 patients in the Onstep group who experienced postoperative pain during sexual activity, 8 had experienced preoperative pain during sexual activity and 7 had not. In the Lichtenstein group, 14 of the 30 patients who experienced postoperative pain had experienced preoperative pain, 14 had not. The remaining patients in both groups reported not having sexual activity before surgery or declined to answer.

The Lichtenstein technique was associated with new pain in 14 of the 70 patients (20%) while 7 of the 74 patients (9%) in the Onstep group reported new pain after surgery.

“For patients who experienced pain during sexual activity preoperatively, the Onstep technique removed the pain during sexual activity in the majority of patients while still resulting in few new cases,” the authors wrote.

Among the Lichtenstein group, 20 patients experienced pain from the surgical scar, compared with 7 patients in the Onstep group.

When asked about the degree of impairment of sexual function because of the postoperative pain, four patients in the Lichtenstein group said they had moderate to severe impairment, but none in the Onstep group reported that level of impairment.

Commenting on the possible mechanisms that might result in pain during sexual activity after hernia repair, the authors noted that mesh has been found to shrink from a mass around the vas deferens after a Lichtenstein repair. Previous studies have also found sutures around the iliohypogastric and the ilioinguinal nerves, which could also result in some pain.

“Because the mesh in the Onstep technique is not fixed with sutures, the risk of capturing nerves during the fixation of mesh is nonexistent,” they wrote. “There could, however, still be a risk of scar tissue and mesh shrinkage.”

PolySoft mesh (Bard Davol) was used for the Lichtenstein group and SoftMesh (Bard Davol) was used for the Onstep group.

In the 6 months’ follow-up period, two patients in the Lichtenstein group and one patient in the Onstep group experienced a recurrence of their hernia.

Three authors reported personal fees and travel grants from private industry – including Bard Medical – outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

The Onstep technique for inguinal hernia repair is associated with a lower incidence of postoperative pain during sexual activity than the Lichtenstein surgical technique, according to a paper published online in Surgery.

This study was a part of the Onli trial, the objective of which was to evaluate chronic pain and sexual dysfunction after inguinal hernia repair involving mesh fixation with sutures (Lichtenstein), compared with no mesh fixation (Onstep). The investigators reported the findings of a large study: 20.8% of inguinal repair patients experienced pain during sexual activity 1.4-1.7 years after their operation (Pain. 2006;122:258-63).

“The Onstep technique could be considered when surgeons and patients are discussing the optimal technique for repair of an inguinal hernia,” wrote Kristoffer Andresen, MD, of the University of Copenhagen, and his coauthors. “If the patient has pain during sexual activity as part of the complaint from the hernia, the Onstep technique seems to have a greater chance of removing this pain and alleviating the complaints.”

Among the 17 patients in the Onstep group who experienced postoperative pain during sexual activity, 8 had experienced preoperative pain during sexual activity and 7 had not. In the Lichtenstein group, 14 of the 30 patients who experienced postoperative pain had experienced preoperative pain, 14 had not. The remaining patients in both groups reported not having sexual activity before surgery or declined to answer.

The Lichtenstein technique was associated with new pain in 14 of the 70 patients (20%) while 7 of the 74 patients (9%) in the Onstep group reported new pain after surgery.

“For patients who experienced pain during sexual activity preoperatively, the Onstep technique removed the pain during sexual activity in the majority of patients while still resulting in few new cases,” the authors wrote.

Among the Lichtenstein group, 20 patients experienced pain from the surgical scar, compared with 7 patients in the Onstep group.

When asked about the degree of impairment of sexual function because of the postoperative pain, four patients in the Lichtenstein group said they had moderate to severe impairment, but none in the Onstep group reported that level of impairment.

Commenting on the possible mechanisms that might result in pain during sexual activity after hernia repair, the authors noted that mesh has been found to shrink from a mass around the vas deferens after a Lichtenstein repair. Previous studies have also found sutures around the iliohypogastric and the ilioinguinal nerves, which could also result in some pain.

“Because the mesh in the Onstep technique is not fixed with sutures, the risk of capturing nerves during the fixation of mesh is nonexistent,” they wrote. “There could, however, still be a risk of scar tissue and mesh shrinkage.”

PolySoft mesh (Bard Davol) was used for the Lichtenstein group and SoftMesh (Bard Davol) was used for the Onstep group.

In the 6 months’ follow-up period, two patients in the Lichtenstein group and one patient in the Onstep group experienced a recurrence of their hernia.

Three authors reported personal fees and travel grants from private industry – including Bard Medical – outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM SURGERY

Key clinical point: The Onstep technique for inguinal hernia repair is associated with a lower incidence of pain during sexual activity than the Lichtenstein technique.

Major finding: The Lichtenstein technique was associated with new pain in 14 of the 70 patients (20%) while 7 of the 74 patients (9%) in the Onstep group reported new pain after surgery.

Data source: A randomized trial in 259 patients undergoing inguinal hernia repair.

Disclosures: Three authors reported personal fees and travel grants from private industry – including Bard Medical – outside the submitted work. No other conflicts of interest were declared.

Reinforcing mesh at ostomy site prevents parastomal hernia

For patients undergoing elective permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia, according to a report published in the April issue of Annals of Surgery.

The incidence of parastomal hernia is expected to rise because of the increasing number of cancer patients surviving with a colostomy, and the rising number of obese patients who have increased tension on the abdominal wall because of their elevated intra-abdominal pressure and larger abdominal radius. Researchers in the Netherlands performed a prospective randomized study, the PREVENT trial, to assess whether augmenting the abdominal wall at the ostomy site, using a lightweight mesh, would be safe, feasible, and effective at preventing parastomal hernia. They reported their findings after 1 year of follow-up; the study will continue until longer-term results are available at 5 years.

In the intervention group, a retromuscular space was created to accommodate the mesh by dissecting the muscle from the posterior fascia or peritoneum to the lateral border via a median laparotomy. An incision was made in the center of the mesh to allow passage of the colon, and the mesh was placed on the posterior rectus sheath and anchored laterally with two absorbable sutures. “On the medial side, the mesh was incorporated in the running suture closing the fascia, thus preventing contact between the mesh and the viscera,” the investigators said (Ann Surg. 2017;265:663-9).

The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group, a significant difference. There were no mesh-related complications such as infection, strictures, or adhesions. “The majority of the parastomal hernias that required surgical repair were in the control group, which supports the concept that if a hernia develops in a patient with mesh, it is smaller and less likely to cause complaints,” Dr. Brandsma and his associates said.

Significantly fewer patients in the mesh group (9%) than in the control group (21%) reported stoma-related complaints such as pain, leakage, and skin problems. Scores on measures of quality of life and pain severity were no different between the two study groups.

“Prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall with a retromuscular polypropylene mesh at the ostomy site is a safe and feasible procedure with no adverse events. It significantly reduces the incidence of parastomal hernia,” the investigators concluded.

This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients undergoing elective permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia, according to a report published in the April issue of Annals of Surgery.

The incidence of parastomal hernia is expected to rise because of the increasing number of cancer patients surviving with a colostomy, and the rising number of obese patients who have increased tension on the abdominal wall because of their elevated intra-abdominal pressure and larger abdominal radius. Researchers in the Netherlands performed a prospective randomized study, the PREVENT trial, to assess whether augmenting the abdominal wall at the ostomy site, using a lightweight mesh, would be safe, feasible, and effective at preventing parastomal hernia. They reported their findings after 1 year of follow-up; the study will continue until longer-term results are available at 5 years.

In the intervention group, a retromuscular space was created to accommodate the mesh by dissecting the muscle from the posterior fascia or peritoneum to the lateral border via a median laparotomy. An incision was made in the center of the mesh to allow passage of the colon, and the mesh was placed on the posterior rectus sheath and anchored laterally with two absorbable sutures. “On the medial side, the mesh was incorporated in the running suture closing the fascia, thus preventing contact between the mesh and the viscera,” the investigators said (Ann Surg. 2017;265:663-9).

The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group, a significant difference. There were no mesh-related complications such as infection, strictures, or adhesions. “The majority of the parastomal hernias that required surgical repair were in the control group, which supports the concept that if a hernia develops in a patient with mesh, it is smaller and less likely to cause complaints,” Dr. Brandsma and his associates said.

Significantly fewer patients in the mesh group (9%) than in the control group (21%) reported stoma-related complaints such as pain, leakage, and skin problems. Scores on measures of quality of life and pain severity were no different between the two study groups.

“Prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall with a retromuscular polypropylene mesh at the ostomy site is a safe and feasible procedure with no adverse events. It significantly reduces the incidence of parastomal hernia,” the investigators concluded.

This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

For patients undergoing elective permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia, according to a report published in the April issue of Annals of Surgery.

The incidence of parastomal hernia is expected to rise because of the increasing number of cancer patients surviving with a colostomy, and the rising number of obese patients who have increased tension on the abdominal wall because of their elevated intra-abdominal pressure and larger abdominal radius. Researchers in the Netherlands performed a prospective randomized study, the PREVENT trial, to assess whether augmenting the abdominal wall at the ostomy site, using a lightweight mesh, would be safe, feasible, and effective at preventing parastomal hernia. They reported their findings after 1 year of follow-up; the study will continue until longer-term results are available at 5 years.

In the intervention group, a retromuscular space was created to accommodate the mesh by dissecting the muscle from the posterior fascia or peritoneum to the lateral border via a median laparotomy. An incision was made in the center of the mesh to allow passage of the colon, and the mesh was placed on the posterior rectus sheath and anchored laterally with two absorbable sutures. “On the medial side, the mesh was incorporated in the running suture closing the fascia, thus preventing contact between the mesh and the viscera,” the investigators said (Ann Surg. 2017;265:663-9).

The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group, a significant difference. There were no mesh-related complications such as infection, strictures, or adhesions. “The majority of the parastomal hernias that required surgical repair were in the control group, which supports the concept that if a hernia develops in a patient with mesh, it is smaller and less likely to cause complaints,” Dr. Brandsma and his associates said.

Significantly fewer patients in the mesh group (9%) than in the control group (21%) reported stoma-related complaints such as pain, leakage, and skin problems. Scores on measures of quality of life and pain severity were no different between the two study groups.

“Prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall with a retromuscular polypropylene mesh at the ostomy site is a safe and feasible procedure with no adverse events. It significantly reduces the incidence of parastomal hernia,” the investigators concluded.

This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE ANNALS OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: For patients undergoing permanent colostomy, prophylactic augmentation of the abdominal wall using mesh at the ostomy site prevents the development of parastomal hernia.

Major finding: The primary end point – the incidence of parastomal hernia at 1 year – occurred in 3 patients (4.5%) in the intervention group and 16 (24.2%) in the control group.

Data source: A prospective, multicenter, randomized cohort study comparing prophylactic mesh against standard care in 133 adults undergoing elective end-colostomy during a 3-year period.

Disclosures: This study was supported by Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital’s surgery research fund, the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development, and Covidien/Medtronic. Dr. Brandsma and his associates reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

Follow-up data support using mesh for umbilical hernia repair

Patients with umbilical hernias and multiple comorbidities should be considered for mesh repair to reduce the risk of recurrence, say the authors of a study of the factors associated with umbilical hernia recurrence after repair.

The retrospective cohort study, published in JAMA Surgery, examined recurrence and mortality outcomes in 332 military veteran patients who underwent primary umbilical hernia repair between 1998 and 2008 and followed until June 2014.

The overall recurrence rate was 6% and a mean recurrence time after index repair of 3.1 years. The recurrence rate was significantly higher among patients who underwent primary suture repair, compared with those who underwent mesh repair (9.8% vs. 2.4%, P = .04). Mesh repair decreased the risk of recurrence more than threefold, compared with primary suture repair (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.95).

Patients with ascites had a significantly greater risk of recurrence, compared with those without ascites (20% vs. 5.1%, P = .02), as did those with liver disease (35% vs. 13.8%, P = .02), and diabetes (55% vs. 32.7%).

“This information suggests that umbilical hernias should be repaired using mesh, especially if a patient has multiple comorbidities that are significantly associated with recurrence, such as obesity, diabetes, liver disease, and ascites,” wrote Divya A. Shankar, a medical student at Boston University School of Medicine, and her coauthors (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5052).

Among these patients, only 1 died within 30 days, but the study captured mortality in this group over 6-16 years after their hernia surgery. Mortality rate in the group was 27% through the follow-up period. However, older individuals, smokers, patients with liver disease and ascites, and those who had to undergo emergency or semi-urgent repair or who required intraoperative bowel resection had significantly increased long-term mortality rates.

“Although there is a trend toward higher mortality rates in patients who underwent emergency repair, it is difficult to interpret whether the deaths were related to the emergency or to underlying medical conditions given that the etiology of the majority of these deaths is unknown,” the authors wrote.

Among the deaths, 43 (48%) were from unknown causes, 18 (20%) were cancer related, 12 (13%) were related to renal disease, and 3 (3.3%) were related to sepsis.

Researchers found that patients with a history of hernias were significantly less likely to have an umbilical hernia recurrence, although a greater percentage of these patients – 61% – received mesh in contrast to the 44% of patients without a history of hernia.

Defect size did not appear to affect the rate of recurrence but the authors noted that defect size was only recorded in about half of the patients in the study.

“Because there was no significant difference between these groups, we are unable to conclude whether the size of defects should play a role in a surgeon’s decision to use mesh,” they wrote.

Sixty-one patients (18%) had at least one complication within 30 days of the repair, with the most common being seroma (9.6%), surgical site infection (6.9%) and hematoma (2.4%). Two patients experienced a mesh infection and three experienced ascites leaks. The rate of complications was slightly, but not significantly, higher in the patients who received mesh repair, compared with the primary suture repair.

“A surprise finding was that patient who underwent emergent or semi-emergent repair had a 2.2 times increased odds of death. Twenty deaths occurred more than 30 days after emergent or semi-urgent repair and 12 (60%) were secondary to unknown causes and 5 (25%) were secondary to liver disease,” the investigators noted.

“Interestingly, 193 (58%) patients who underwent umbilical hernia repair had other hernias that were either repaired before the index repair or developed postoperatively. Therefore, we propose that umbilical hernias may be a type of ‘field defect’ and we support the idea of that abnormal collegan metabolism could play a role in hernia development. ...We speculate that surgeons might be more inclined to use mesh in a patients with a history of other hernias.”

Despite the potential for complications, “elective hernia repair with mesh should be considered in patients with multiple comorbidities given that the use of mesh offers protection from recurrence without major morbidity.”

The study was supported by the VA Healthcare System. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Patients with umbilical hernias and multiple comorbidities should be considered for mesh repair to reduce the risk of recurrence, say the authors of a study of the factors associated with umbilical hernia recurrence after repair.

The retrospective cohort study, published in JAMA Surgery, examined recurrence and mortality outcomes in 332 military veteran patients who underwent primary umbilical hernia repair between 1998 and 2008 and followed until June 2014.

The overall recurrence rate was 6% and a mean recurrence time after index repair of 3.1 years. The recurrence rate was significantly higher among patients who underwent primary suture repair, compared with those who underwent mesh repair (9.8% vs. 2.4%, P = .04). Mesh repair decreased the risk of recurrence more than threefold, compared with primary suture repair (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.95).

Patients with ascites had a significantly greater risk of recurrence, compared with those without ascites (20% vs. 5.1%, P = .02), as did those with liver disease (35% vs. 13.8%, P = .02), and diabetes (55% vs. 32.7%).

“This information suggests that umbilical hernias should be repaired using mesh, especially if a patient has multiple comorbidities that are significantly associated with recurrence, such as obesity, diabetes, liver disease, and ascites,” wrote Divya A. Shankar, a medical student at Boston University School of Medicine, and her coauthors (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5052).

Among these patients, only 1 died within 30 days, but the study captured mortality in this group over 6-16 years after their hernia surgery. Mortality rate in the group was 27% through the follow-up period. However, older individuals, smokers, patients with liver disease and ascites, and those who had to undergo emergency or semi-urgent repair or who required intraoperative bowel resection had significantly increased long-term mortality rates.

“Although there is a trend toward higher mortality rates in patients who underwent emergency repair, it is difficult to interpret whether the deaths were related to the emergency or to underlying medical conditions given that the etiology of the majority of these deaths is unknown,” the authors wrote.

Among the deaths, 43 (48%) were from unknown causes, 18 (20%) were cancer related, 12 (13%) were related to renal disease, and 3 (3.3%) were related to sepsis.

Researchers found that patients with a history of hernias were significantly less likely to have an umbilical hernia recurrence, although a greater percentage of these patients – 61% – received mesh in contrast to the 44% of patients without a history of hernia.

Defect size did not appear to affect the rate of recurrence but the authors noted that defect size was only recorded in about half of the patients in the study.

“Because there was no significant difference between these groups, we are unable to conclude whether the size of defects should play a role in a surgeon’s decision to use mesh,” they wrote.

Sixty-one patients (18%) had at least one complication within 30 days of the repair, with the most common being seroma (9.6%), surgical site infection (6.9%) and hematoma (2.4%). Two patients experienced a mesh infection and three experienced ascites leaks. The rate of complications was slightly, but not significantly, higher in the patients who received mesh repair, compared with the primary suture repair.

“A surprise finding was that patient who underwent emergent or semi-emergent repair had a 2.2 times increased odds of death. Twenty deaths occurred more than 30 days after emergent or semi-urgent repair and 12 (60%) were secondary to unknown causes and 5 (25%) were secondary to liver disease,” the investigators noted.

“Interestingly, 193 (58%) patients who underwent umbilical hernia repair had other hernias that were either repaired before the index repair or developed postoperatively. Therefore, we propose that umbilical hernias may be a type of ‘field defect’ and we support the idea of that abnormal collegan metabolism could play a role in hernia development. ...We speculate that surgeons might be more inclined to use mesh in a patients with a history of other hernias.”

Despite the potential for complications, “elective hernia repair with mesh should be considered in patients with multiple comorbidities given that the use of mesh offers protection from recurrence without major morbidity.”

The study was supported by the VA Healthcare System. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Patients with umbilical hernias and multiple comorbidities should be considered for mesh repair to reduce the risk of recurrence, say the authors of a study of the factors associated with umbilical hernia recurrence after repair.

The retrospective cohort study, published in JAMA Surgery, examined recurrence and mortality outcomes in 332 military veteran patients who underwent primary umbilical hernia repair between 1998 and 2008 and followed until June 2014.

The overall recurrence rate was 6% and a mean recurrence time after index repair of 3.1 years. The recurrence rate was significantly higher among patients who underwent primary suture repair, compared with those who underwent mesh repair (9.8% vs. 2.4%, P = .04). Mesh repair decreased the risk of recurrence more than threefold, compared with primary suture repair (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval, 0.08-0.95).

Patients with ascites had a significantly greater risk of recurrence, compared with those without ascites (20% vs. 5.1%, P = .02), as did those with liver disease (35% vs. 13.8%, P = .02), and diabetes (55% vs. 32.7%).

“This information suggests that umbilical hernias should be repaired using mesh, especially if a patient has multiple comorbidities that are significantly associated with recurrence, such as obesity, diabetes, liver disease, and ascites,” wrote Divya A. Shankar, a medical student at Boston University School of Medicine, and her coauthors (JAMA Surg. 2017 Jan 25. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5052).

Among these patients, only 1 died within 30 days, but the study captured mortality in this group over 6-16 years after their hernia surgery. Mortality rate in the group was 27% through the follow-up period. However, older individuals, smokers, patients with liver disease and ascites, and those who had to undergo emergency or semi-urgent repair or who required intraoperative bowel resection had significantly increased long-term mortality rates.

“Although there is a trend toward higher mortality rates in patients who underwent emergency repair, it is difficult to interpret whether the deaths were related to the emergency or to underlying medical conditions given that the etiology of the majority of these deaths is unknown,” the authors wrote.

Among the deaths, 43 (48%) were from unknown causes, 18 (20%) were cancer related, 12 (13%) were related to renal disease, and 3 (3.3%) were related to sepsis.

Researchers found that patients with a history of hernias were significantly less likely to have an umbilical hernia recurrence, although a greater percentage of these patients – 61% – received mesh in contrast to the 44% of patients without a history of hernia.

Defect size did not appear to affect the rate of recurrence but the authors noted that defect size was only recorded in about half of the patients in the study.

“Because there was no significant difference between these groups, we are unable to conclude whether the size of defects should play a role in a surgeon’s decision to use mesh,” they wrote.

Sixty-one patients (18%) had at least one complication within 30 days of the repair, with the most common being seroma (9.6%), surgical site infection (6.9%) and hematoma (2.4%). Two patients experienced a mesh infection and three experienced ascites leaks. The rate of complications was slightly, but not significantly, higher in the patients who received mesh repair, compared with the primary suture repair.

“A surprise finding was that patient who underwent emergent or semi-emergent repair had a 2.2 times increased odds of death. Twenty deaths occurred more than 30 days after emergent or semi-urgent repair and 12 (60%) were secondary to unknown causes and 5 (25%) were secondary to liver disease,” the investigators noted.

“Interestingly, 193 (58%) patients who underwent umbilical hernia repair had other hernias that were either repaired before the index repair or developed postoperatively. Therefore, we propose that umbilical hernias may be a type of ‘field defect’ and we support the idea of that abnormal collegan metabolism could play a role in hernia development. ...We speculate that surgeons might be more inclined to use mesh in a patients with a history of other hernias.”

Despite the potential for complications, “elective hernia repair with mesh should be considered in patients with multiple comorbidities given that the use of mesh offers protection from recurrence without major morbidity.”

The study was supported by the VA Healthcare System. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JAMA SURGERY

Onlay mesh with adhesive just as safe as sublay route

While using sublay mesh continues to be standard practice when performing ventral hernia repair (VHR), a recent study shows that using onlay mesh placement with adhesive can be just as safe, at least in the short term.

“While the use of mesh during VHR is well accepted, the ideal location of mesh placement remains heavily debated,” wrote the study’s authors, adding that the “paucity of high-level data has led the choice of mesh location to reside primarily on the preference of the surgeon rather than grounded in clinical outcomes.”

The investigators identified patients in the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative national registry who were undergoing open, elective VHR and had clean wounds and a wound class I designation based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines at any point between January 2013 and January 2016. A total of 1,854 individuals were ultimately selected for inclusion in the study and were divided into two groups: one that received traditional VHR with sublay mesh and one that received onlay mesh with adhesive.

All subjects’ data were analyzed within 30 days for any adverse events related to the wounds from the surgery. These events were surgical site infections, surgical site occurrences – which could include an infection and any skin or soft tissue ischemia, necrosis, or other events – and surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention, which were defined as any occurrences that required “opening of the wound, wound debridement, suture excision, percutaneous drainage, or partial or complete mesh removal.”

The sublay cohort numbered 1,761 (95.0%), compared with 93 (5.0%) who received the onlay technique. There was no significant difference found in the rate of 30-day adverse incidents between the two cohorts. For surgical site infections, the sublay cohort rate was 2.9%, while the onlay cohort had a 5.5% rate (P = .30). Surgical site occurrences happened in 15.2% of sublay patients versus 7.7% of those in the other group (P = .08), while surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention were 8.2% in sublay patients but 5.5% in onlay patients (P = .42).

While both approaches fared similarly in terms of comorbidities and average Ventral Hernia Working Group grade, the investigators recommend that “the Chevrel onlay technique be used in nonobese patients without significant comorbidities, with moderate hernia defects, and whose abdominal wall vasculatures are without risk of compromise.” The data were generalizable because of the number of surgeons performing VHR and because the data sample allowed the investigators to control for the hernia width, defect size, and patient comorbidities this case, leading to this conclusion.

“Additional studies are needed to determine the long-term benefits of both approaches with respect to mesh infection rates and hernia recurrence rates, as well as the ideal mesh location for ventral hernia repairs in higher-risk patients,” the authors concluded.

No funding source was disclosed for this study. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

While using sublay mesh continues to be standard practice when performing ventral hernia repair (VHR), a recent study shows that using onlay mesh placement with adhesive can be just as safe, at least in the short term.

“While the use of mesh during VHR is well accepted, the ideal location of mesh placement remains heavily debated,” wrote the study’s authors, adding that the “paucity of high-level data has led the choice of mesh location to reside primarily on the preference of the surgeon rather than grounded in clinical outcomes.”

The investigators identified patients in the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative national registry who were undergoing open, elective VHR and had clean wounds and a wound class I designation based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines at any point between January 2013 and January 2016. A total of 1,854 individuals were ultimately selected for inclusion in the study and were divided into two groups: one that received traditional VHR with sublay mesh and one that received onlay mesh with adhesive.

All subjects’ data were analyzed within 30 days for any adverse events related to the wounds from the surgery. These events were surgical site infections, surgical site occurrences – which could include an infection and any skin or soft tissue ischemia, necrosis, or other events – and surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention, which were defined as any occurrences that required “opening of the wound, wound debridement, suture excision, percutaneous drainage, or partial or complete mesh removal.”

The sublay cohort numbered 1,761 (95.0%), compared with 93 (5.0%) who received the onlay technique. There was no significant difference found in the rate of 30-day adverse incidents between the two cohorts. For surgical site infections, the sublay cohort rate was 2.9%, while the onlay cohort had a 5.5% rate (P = .30). Surgical site occurrences happened in 15.2% of sublay patients versus 7.7% of those in the other group (P = .08), while surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention were 8.2% in sublay patients but 5.5% in onlay patients (P = .42).

While both approaches fared similarly in terms of comorbidities and average Ventral Hernia Working Group grade, the investigators recommend that “the Chevrel onlay technique be used in nonobese patients without significant comorbidities, with moderate hernia defects, and whose abdominal wall vasculatures are without risk of compromise.” The data were generalizable because of the number of surgeons performing VHR and because the data sample allowed the investigators to control for the hernia width, defect size, and patient comorbidities this case, leading to this conclusion.

“Additional studies are needed to determine the long-term benefits of both approaches with respect to mesh infection rates and hernia recurrence rates, as well as the ideal mesh location for ventral hernia repairs in higher-risk patients,” the authors concluded.

No funding source was disclosed for this study. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

While using sublay mesh continues to be standard practice when performing ventral hernia repair (VHR), a recent study shows that using onlay mesh placement with adhesive can be just as safe, at least in the short term.

“While the use of mesh during VHR is well accepted, the ideal location of mesh placement remains heavily debated,” wrote the study’s authors, adding that the “paucity of high-level data has led the choice of mesh location to reside primarily on the preference of the surgeon rather than grounded in clinical outcomes.”

The investigators identified patients in the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative national registry who were undergoing open, elective VHR and had clean wounds and a wound class I designation based on Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines at any point between January 2013 and January 2016. A total of 1,854 individuals were ultimately selected for inclusion in the study and were divided into two groups: one that received traditional VHR with sublay mesh and one that received onlay mesh with adhesive.

All subjects’ data were analyzed within 30 days for any adverse events related to the wounds from the surgery. These events were surgical site infections, surgical site occurrences – which could include an infection and any skin or soft tissue ischemia, necrosis, or other events – and surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention, which were defined as any occurrences that required “opening of the wound, wound debridement, suture excision, percutaneous drainage, or partial or complete mesh removal.”

The sublay cohort numbered 1,761 (95.0%), compared with 93 (5.0%) who received the onlay technique. There was no significant difference found in the rate of 30-day adverse incidents between the two cohorts. For surgical site infections, the sublay cohort rate was 2.9%, while the onlay cohort had a 5.5% rate (P = .30). Surgical site occurrences happened in 15.2% of sublay patients versus 7.7% of those in the other group (P = .08), while surgical site occurrences that required procedural intervention were 8.2% in sublay patients but 5.5% in onlay patients (P = .42).

While both approaches fared similarly in terms of comorbidities and average Ventral Hernia Working Group grade, the investigators recommend that “the Chevrel onlay technique be used in nonobese patients without significant comorbidities, with moderate hernia defects, and whose abdominal wall vasculatures are without risk of compromise.” The data were generalizable because of the number of surgeons performing VHR and because the data sample allowed the investigators to control for the hernia width, defect size, and patient comorbidities this case, leading to this conclusion.

“Additional studies are needed to determine the long-term benefits of both approaches with respect to mesh infection rates and hernia recurrence rates, as well as the ideal mesh location for ventral hernia repairs in higher-risk patients,” the authors concluded.

No funding source was disclosed for this study. The investigators reported no relevant financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: No significant differences were found between onlay and sublay mesh VHR patients in terms of surgical site infection (P = .30), surgical site occurrences (P = .08), and surgical site occurrences that required intervention (P = .42).

Data source: Retrospective cohort study of 1,854 VHR patients between January 2013 and January 2016.

Disclosures: No funding source disclosed. Authors reported no relevant financial disclosures.

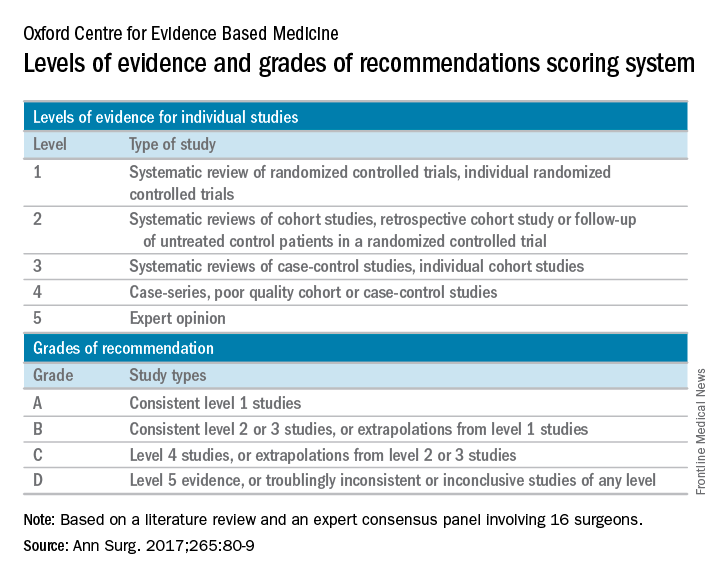

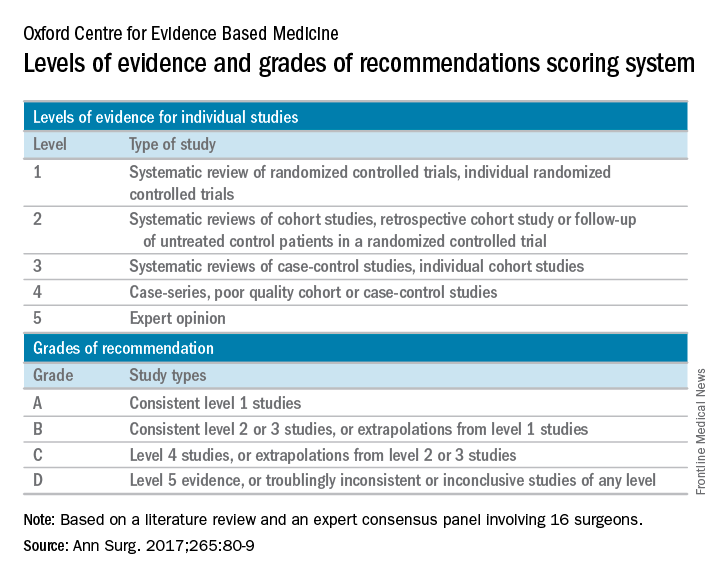

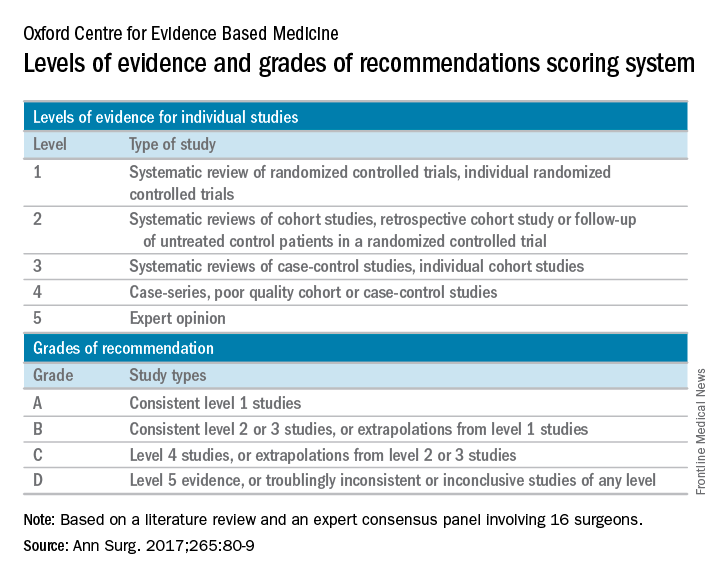

Expert panel reaches consensus on hernia management recommendations

Those are key conclusions from a consensus statement based on a systematic review of existing evidence in the medical literature about ventral hernia management that were published in the January 2017 issue of the Annals of Surgery.

“Despite ventral hernias (VH) being one of the most common pathologies seen by clinicians, significant variability in management exists,” wrote the researchers, led by Mike K. Liang, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “Surveys of clinicians and review of nationwide databases of patients undergoing elective ventral hernia repair (VHR) demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in patient selection and clinical practice.”

The panelists agreed that complications with VHR increase in obese patients (grade A evidence), current smokers (grade A), and in patients with glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 6.5% or greater (grade B). They did not recommend elective VHR in patients with a body mass index of 50 kg/m2 or greater (grade C), in current smokers (grade A), or patients with an HbA1c of 8.0% or greater (grade B). They also agreed that patients with a BMI of 30-50 kg/m2 or an HbA1c level of 6.5%-8.0% require individualized interventions to reduce surgical risk (grade C, grade B, respectively). The panelists considered nonoperative management to have a low risk of short-term morbidity (grade C) and they recommended mesh reinforcement for repair of hernias 2 cm or greater in size (grade A).

The panelists failed to reach agreement on several areas where high-quality data were limited, including mesh type. “Categories include ultra-light weight, light-weight, mid-weight, heavy-weight, and super-heavy weight, though precise definitions for each category are variable,” authors of the consensus statement wrote. “Randomized controlled trials are needed to compare synthetic, biological, and bioabsorbable meshes in all VH types and clinical settings.”

The authors of the consensus statement also called for further high-quality studies to better assess the management of VH in complex patients, which they defined as those presenting acutely, patients with cirrhosis, patients with inflammatory bowel disease, and patients who are pregnant.

The authors acknowledged certain limitations of the statement, including the fact that not all VH experts were included on the consensus panel. “However, the panel consisted of a large group of national experts with a primary practice focus of VHR,” they wrote. “The panelists have diverse views and unique areas of knowledge in the realm of hernia repair. The differing backgrounds among panelists was intended to make the guidelines that were developed more generalizable, as there is a wide variety of experience and skill level in the surgical community. In addition, there are no objective criteria to define an ‘expert’ in VH management.”

This work was supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

dbrunk@frontlinemedcom.com

Those are key conclusions from a consensus statement based on a systematic review of existing evidence in the medical literature about ventral hernia management that were published in the January 2017 issue of the Annals of Surgery.

“Despite ventral hernias (VH) being one of the most common pathologies seen by clinicians, significant variability in management exists,” wrote the researchers, led by Mike K. Liang, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “Surveys of clinicians and review of nationwide databases of patients undergoing elective ventral hernia repair (VHR) demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in patient selection and clinical practice.”

The panelists agreed that complications with VHR increase in obese patients (grade A evidence), current smokers (grade A), and in patients with glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 6.5% or greater (grade B). They did not recommend elective VHR in patients with a body mass index of 50 kg/m2 or greater (grade C), in current smokers (grade A), or patients with an HbA1c of 8.0% or greater (grade B). They also agreed that patients with a BMI of 30-50 kg/m2 or an HbA1c level of 6.5%-8.0% require individualized interventions to reduce surgical risk (grade C, grade B, respectively). The panelists considered nonoperative management to have a low risk of short-term morbidity (grade C) and they recommended mesh reinforcement for repair of hernias 2 cm or greater in size (grade A).

The panelists failed to reach agreement on several areas where high-quality data were limited, including mesh type. “Categories include ultra-light weight, light-weight, mid-weight, heavy-weight, and super-heavy weight, though precise definitions for each category are variable,” authors of the consensus statement wrote. “Randomized controlled trials are needed to compare synthetic, biological, and bioabsorbable meshes in all VH types and clinical settings.”

The authors of the consensus statement also called for further high-quality studies to better assess the management of VH in complex patients, which they defined as those presenting acutely, patients with cirrhosis, patients with inflammatory bowel disease, and patients who are pregnant.

The authors acknowledged certain limitations of the statement, including the fact that not all VH experts were included on the consensus panel. “However, the panel consisted of a large group of national experts with a primary practice focus of VHR,” they wrote. “The panelists have diverse views and unique areas of knowledge in the realm of hernia repair. The differing backgrounds among panelists was intended to make the guidelines that were developed more generalizable, as there is a wide variety of experience and skill level in the surgical community. In addition, there are no objective criteria to define an ‘expert’ in VH management.”

This work was supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

dbrunk@frontlinemedcom.com

Those are key conclusions from a consensus statement based on a systematic review of existing evidence in the medical literature about ventral hernia management that were published in the January 2017 issue of the Annals of Surgery.

“Despite ventral hernias (VH) being one of the most common pathologies seen by clinicians, significant variability in management exists,” wrote the researchers, led by Mike K. Liang, MD, of the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. “Surveys of clinicians and review of nationwide databases of patients undergoing elective ventral hernia repair (VHR) demonstrate substantial heterogeneity in patient selection and clinical practice.”

The panelists agreed that complications with VHR increase in obese patients (grade A evidence), current smokers (grade A), and in patients with glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 6.5% or greater (grade B). They did not recommend elective VHR in patients with a body mass index of 50 kg/m2 or greater (grade C), in current smokers (grade A), or patients with an HbA1c of 8.0% or greater (grade B). They also agreed that patients with a BMI of 30-50 kg/m2 or an HbA1c level of 6.5%-8.0% require individualized interventions to reduce surgical risk (grade C, grade B, respectively). The panelists considered nonoperative management to have a low risk of short-term morbidity (grade C) and they recommended mesh reinforcement for repair of hernias 2 cm or greater in size (grade A).

The panelists failed to reach agreement on several areas where high-quality data were limited, including mesh type. “Categories include ultra-light weight, light-weight, mid-weight, heavy-weight, and super-heavy weight, though precise definitions for each category are variable,” authors of the consensus statement wrote. “Randomized controlled trials are needed to compare synthetic, biological, and bioabsorbable meshes in all VH types and clinical settings.”

The authors of the consensus statement also called for further high-quality studies to better assess the management of VH in complex patients, which they defined as those presenting acutely, patients with cirrhosis, patients with inflammatory bowel disease, and patients who are pregnant.

The authors acknowledged certain limitations of the statement, including the fact that not all VH experts were included on the consensus panel. “However, the panel consisted of a large group of national experts with a primary practice focus of VHR,” they wrote. “The panelists have diverse views and unique areas of knowledge in the realm of hernia repair. The differing backgrounds among panelists was intended to make the guidelines that were developed more generalizable, as there is a wide variety of experience and skill level in the surgical community. In addition, there are no objective criteria to define an ‘expert’ in VH management.”

This work was supported by the Center for Clinical and Translational Sciences. The authors reported having no financial disclosures.

dbrunk@frontlinemedcom.com

FROM ANNALS OF SURGERY

Longer follow-up needed to track mesh explantation trends

Explantation of mesh used in ventral hernia repair occurs in approximately 1 of every 1,000 surgeries, but it’s a “hidden” morbidity because it almost always happens well after the 30- to 90-day window in which postoperative complications are typically reported in most registries and surveillance systems, according to a report in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Mesh explantation usually occurs 1-3 years after implantation and triples the operative costs of the original ventral hernia repair. The rate of 1 per 1,000 surgeries and the massive increase in cost are comparable with those of occult injury of the common bile duct during cholecystectomy that later requires biliary reconstruction. But mesh explantation doesn’t generate the “profound attention” accorded to bile duct injury, perhaps because it develops much later in the postoperative course.

“It is surprising that mesh complications have not yet prompted similar concern,” said Kristy Kummerow Broman, MD, of the department of surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and her associates.

Until now, the frequency and cost of mesh explantation after ventral hernia repair in the general population have not been known. To make a reasonable estimate, the investigators constructed a cohort of 619,751 patients using information from inpatient and surgery databases for New York, California, and Florida between 2005 and 2011. Most of these were open procedures (91%), while 9% were laparoscopic.

During a mean follow-up of 3 years, 438 patients (0.7 per 1,000) underwent mesh explantation. This is a clinically significant incidence, and is likely an underestimate because ICD-9 and CPT coding for mesh removal is highly variable, Dr. Broman and her associates said.

This rate, for just three states during 3 years of follow-up, is nearly twice as high as the rate of mesh-related complications voluntarily reported to the FDA in post-marketing surveillance for the entire country during a 7-year period, they noted (J Am Coll Surg. 2017 Jan;224:35-42).

“It is paramount” that surgeons, manufacturers, and regulatory groups advocate mandatory reporting and “extend the surveillance for at least 1-3 years after implantation of a mesh device,” Dr. Broman and her associates said.

In this study, the median time to explantation was approximately 1 year (range, 2 days to 6 years), and 80% of explantations occurred within 2 years.

The median cumulative operative cost – excluding physician fees, nonsurgical medical costs, and the costs of patient disability and lost productivity – were $21,889 for patients requiring mesh explantation, compared with only $6,579 for those who did not. This finding highlights “the profound long-term implications of implantable devices in abdominal wall reconstruction,” they noted.

To put their findings in context, the investigators reviewed the literature regarding major bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. One large study on cases from 2001 to 2011 found that the rate of biliary reconstruction was comparable with that of explantation, at 0.8 to 1.1 per 1,000. Similarly, reoperation for bile duct injury approximately tripled the operative costs ($9,061 for patients who required biliary reconstruction vs $2,689 for those who didn’t). However, the $21,000 for mesh reoperation far exceeds the $9,000 for biliary reoperation.

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, and the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative. Dr. Broman reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Intuitive Surgical Solutions, Bard Davol, Ariste Medical, and Pfizer.

Explantation of mesh used in ventral hernia repair occurs in approximately 1 of every 1,000 surgeries, but it’s a “hidden” morbidity because it almost always happens well after the 30- to 90-day window in which postoperative complications are typically reported in most registries and surveillance systems, according to a report in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Mesh explantation usually occurs 1-3 years after implantation and triples the operative costs of the original ventral hernia repair. The rate of 1 per 1,000 surgeries and the massive increase in cost are comparable with those of occult injury of the common bile duct during cholecystectomy that later requires biliary reconstruction. But mesh explantation doesn’t generate the “profound attention” accorded to bile duct injury, perhaps because it develops much later in the postoperative course.

“It is surprising that mesh complications have not yet prompted similar concern,” said Kristy Kummerow Broman, MD, of the department of surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and her associates.

Until now, the frequency and cost of mesh explantation after ventral hernia repair in the general population have not been known. To make a reasonable estimate, the investigators constructed a cohort of 619,751 patients using information from inpatient and surgery databases for New York, California, and Florida between 2005 and 2011. Most of these were open procedures (91%), while 9% were laparoscopic.

During a mean follow-up of 3 years, 438 patients (0.7 per 1,000) underwent mesh explantation. This is a clinically significant incidence, and is likely an underestimate because ICD-9 and CPT coding for mesh removal is highly variable, Dr. Broman and her associates said.

This rate, for just three states during 3 years of follow-up, is nearly twice as high as the rate of mesh-related complications voluntarily reported to the FDA in post-marketing surveillance for the entire country during a 7-year period, they noted (J Am Coll Surg. 2017 Jan;224:35-42).

“It is paramount” that surgeons, manufacturers, and regulatory groups advocate mandatory reporting and “extend the surveillance for at least 1-3 years after implantation of a mesh device,” Dr. Broman and her associates said.

In this study, the median time to explantation was approximately 1 year (range, 2 days to 6 years), and 80% of explantations occurred within 2 years.

The median cumulative operative cost – excluding physician fees, nonsurgical medical costs, and the costs of patient disability and lost productivity – were $21,889 for patients requiring mesh explantation, compared with only $6,579 for those who did not. This finding highlights “the profound long-term implications of implantable devices in abdominal wall reconstruction,” they noted.

To put their findings in context, the investigators reviewed the literature regarding major bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. One large study on cases from 2001 to 2011 found that the rate of biliary reconstruction was comparable with that of explantation, at 0.8 to 1.1 per 1,000. Similarly, reoperation for bile duct injury approximately tripled the operative costs ($9,061 for patients who required biliary reconstruction vs $2,689 for those who didn’t). However, the $21,000 for mesh reoperation far exceeds the $9,000 for biliary reoperation.

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, and the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative. Dr. Broman reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Intuitive Surgical Solutions, Bard Davol, Ariste Medical, and Pfizer.

Explantation of mesh used in ventral hernia repair occurs in approximately 1 of every 1,000 surgeries, but it’s a “hidden” morbidity because it almost always happens well after the 30- to 90-day window in which postoperative complications are typically reported in most registries and surveillance systems, according to a report in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Mesh explantation usually occurs 1-3 years after implantation and triples the operative costs of the original ventral hernia repair. The rate of 1 per 1,000 surgeries and the massive increase in cost are comparable with those of occult injury of the common bile duct during cholecystectomy that later requires biliary reconstruction. But mesh explantation doesn’t generate the “profound attention” accorded to bile duct injury, perhaps because it develops much later in the postoperative course.

“It is surprising that mesh complications have not yet prompted similar concern,” said Kristy Kummerow Broman, MD, of the department of surgery, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, Tenn., and her associates.

Until now, the frequency and cost of mesh explantation after ventral hernia repair in the general population have not been known. To make a reasonable estimate, the investigators constructed a cohort of 619,751 patients using information from inpatient and surgery databases for New York, California, and Florida between 2005 and 2011. Most of these were open procedures (91%), while 9% were laparoscopic.

During a mean follow-up of 3 years, 438 patients (0.7 per 1,000) underwent mesh explantation. This is a clinically significant incidence, and is likely an underestimate because ICD-9 and CPT coding for mesh removal is highly variable, Dr. Broman and her associates said.

This rate, for just three states during 3 years of follow-up, is nearly twice as high as the rate of mesh-related complications voluntarily reported to the FDA in post-marketing surveillance for the entire country during a 7-year period, they noted (J Am Coll Surg. 2017 Jan;224:35-42).

“It is paramount” that surgeons, manufacturers, and regulatory groups advocate mandatory reporting and “extend the surveillance for at least 1-3 years after implantation of a mesh device,” Dr. Broman and her associates said.

In this study, the median time to explantation was approximately 1 year (range, 2 days to 6 years), and 80% of explantations occurred within 2 years.

The median cumulative operative cost – excluding physician fees, nonsurgical medical costs, and the costs of patient disability and lost productivity – were $21,889 for patients requiring mesh explantation, compared with only $6,579 for those who did not. This finding highlights “the profound long-term implications of implantable devices in abdominal wall reconstruction,” they noted.

To put their findings in context, the investigators reviewed the literature regarding major bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. One large study on cases from 2001 to 2011 found that the rate of biliary reconstruction was comparable with that of explantation, at 0.8 to 1.1 per 1,000. Similarly, reoperation for bile duct injury approximately tripled the operative costs ($9,061 for patients who required biliary reconstruction vs $2,689 for those who didn’t). However, the $21,000 for mesh reoperation far exceeds the $9,000 for biliary reoperation.

This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, and the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative. Dr. Broman reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Intuitive Surgical Solutions, Bard Davol, Ariste Medical, and Pfizer.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OF SURGEONS

Key clinical point: Explantation of mesh used in ventral hernia repair occurs in approximately 1 of every 1,000 surgeries, but it’s a “hidden” morbidity because it almost always happens well after the 30- to 90-day window in which postoperative complications are typically reported in most registries and surveillance systems.

Major finding: The 1/1,000 rate of mesh explantation, for three states during 3 years of follow-up, is nearly twice as high as the rate voluntarily reported to the Food and Drug Administration in post-marketing surveillance for the entire country during a 7-year period.

Data source: A longitudinal cohort study involving 619,751 adults undergoing ventral hernia repair in New York, California, and Florida who were followed for up to 6 years for mesh explantation.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, and the Americas Hernia Society Quality Collaborative. Dr. Broman reported having no relevant financial disclosures; her associates reported ties to Intuitive Surgical Solutions, Bard Davol, Ariste Medical, and Pfizer.

Lightweight mesh linked to longer LOS, worse QOL

Compared with midweight mesh, lightweight mesh was associated with more surgical site infection and longer hospital stay following open ventral hernia repair, according to a report published in the American Journal of Surgery.

In addition, lightweight mesh was associated with greater pain, more limitation of movement, and poorer quality of life for up to 2 years after the procedure, compared with midweight mesh.

Approximately 250,000 open ventral hernia repairs are performed in the Unites States each year, and mesh is used in 85% or more. Since heavyweight mesh was found to reduce abdominal wall mobility, which led to chronic discomfort in about 20% of cases, manufacturers turned to mesh that was more flexible, had reduced mass to decrease foreign-body reactions, but was strong enough to withstand the physiological stress that the abdominal wall is subjected to, the investigators noted.

They compared outcomes after hernia repairs using lightweight and midweight mesh by analyzing information in the International Hernia Mesh Registry database, which covers more than 30 medical centers in 10 countries. For this study, the researchers focused on 549 patients for whom surgeons had selected lightweight (34.2%) or midweight (47.7%) mesh. (The remaining 18.1% of cases used heavyweight mesh.)

Across the study groups, patients were similar for gender distribution; body mass index; race; and the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and immunosuppression – factors that can heavily influence wound repair.

In an initial analysis of the data, midweight mesh was associated with significantly fewer superficial surgical site infections (1.2%) than lightweight mesh (4.8%), as well as a significantly shorter length of stay (3.6 days vs 5.3 days). However, rates of postoperative abdominal wall complications, abscesses, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, hematoma formation, seroma formation, ileus, deep vein thrombosis, and unplanned returns to the operating room were similar.

At 6-month follow-up, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly greater mesh sensation, abdominal discomfort, and movement limitation, as well as significantly worse overall quality of life (QOL), than midweight mesh. At 12 months, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly greater pain and limitation of movement and significantly worse QOL. At 24 months, lightweight mesh continued to be associated with movement limitation, but scores on other measures were similar to those with midweight mesh.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for many potentially confounding variables, including smoking status, separation of the components of the mesh, the number of sutures anchoring the mesh, and the mesh location within the abdomen, midweight mesh was not associated with worse QOL scores at any time point. In contrast, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly worse QOL scores at 6 months, with an odds ratio of 2.64, and with significantly more pain at 12 months, with an OR of 2.58, Dr. Groene and his associates said (Am J Surg. 2016 Dec;212[6]:1054-62).

The investigators also noted that among their own hernia repair patients, lightweight mesh tends to fracture more easily than midweight mesh. Recent studies also have reported that over time, lightweight mesh is more likely to fail due to fracturing than midweight mesh, they added.

This study had no relevant financial relationships or sources of support. Dr. Groene and his associates reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Compared with midweight mesh, lightweight mesh was associated with more surgical site infection and longer hospital stay following open ventral hernia repair, according to a report published in the American Journal of Surgery.

In addition, lightweight mesh was associated with greater pain, more limitation of movement, and poorer quality of life for up to 2 years after the procedure, compared with midweight mesh.

Approximately 250,000 open ventral hernia repairs are performed in the Unites States each year, and mesh is used in 85% or more. Since heavyweight mesh was found to reduce abdominal wall mobility, which led to chronic discomfort in about 20% of cases, manufacturers turned to mesh that was more flexible, had reduced mass to decrease foreign-body reactions, but was strong enough to withstand the physiological stress that the abdominal wall is subjected to, the investigators noted.

They compared outcomes after hernia repairs using lightweight and midweight mesh by analyzing information in the International Hernia Mesh Registry database, which covers more than 30 medical centers in 10 countries. For this study, the researchers focused on 549 patients for whom surgeons had selected lightweight (34.2%) or midweight (47.7%) mesh. (The remaining 18.1% of cases used heavyweight mesh.)

Across the study groups, patients were similar for gender distribution; body mass index; race; and the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and immunosuppression – factors that can heavily influence wound repair.

In an initial analysis of the data, midweight mesh was associated with significantly fewer superficial surgical site infections (1.2%) than lightweight mesh (4.8%), as well as a significantly shorter length of stay (3.6 days vs 5.3 days). However, rates of postoperative abdominal wall complications, abscesses, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, hematoma formation, seroma formation, ileus, deep vein thrombosis, and unplanned returns to the operating room were similar.

At 6-month follow-up, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly greater mesh sensation, abdominal discomfort, and movement limitation, as well as significantly worse overall quality of life (QOL), than midweight mesh. At 12 months, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly greater pain and limitation of movement and significantly worse QOL. At 24 months, lightweight mesh continued to be associated with movement limitation, but scores on other measures were similar to those with midweight mesh.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for many potentially confounding variables, including smoking status, separation of the components of the mesh, the number of sutures anchoring the mesh, and the mesh location within the abdomen, midweight mesh was not associated with worse QOL scores at any time point. In contrast, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly worse QOL scores at 6 months, with an odds ratio of 2.64, and with significantly more pain at 12 months, with an OR of 2.58, Dr. Groene and his associates said (Am J Surg. 2016 Dec;212[6]:1054-62).

The investigators also noted that among their own hernia repair patients, lightweight mesh tends to fracture more easily than midweight mesh. Recent studies also have reported that over time, lightweight mesh is more likely to fail due to fracturing than midweight mesh, they added.

This study had no relevant financial relationships or sources of support. Dr. Groene and his associates reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Compared with midweight mesh, lightweight mesh was associated with more surgical site infection and longer hospital stay following open ventral hernia repair, according to a report published in the American Journal of Surgery.

In addition, lightweight mesh was associated with greater pain, more limitation of movement, and poorer quality of life for up to 2 years after the procedure, compared with midweight mesh.

Approximately 250,000 open ventral hernia repairs are performed in the Unites States each year, and mesh is used in 85% or more. Since heavyweight mesh was found to reduce abdominal wall mobility, which led to chronic discomfort in about 20% of cases, manufacturers turned to mesh that was more flexible, had reduced mass to decrease foreign-body reactions, but was strong enough to withstand the physiological stress that the abdominal wall is subjected to, the investigators noted.

They compared outcomes after hernia repairs using lightweight and midweight mesh by analyzing information in the International Hernia Mesh Registry database, which covers more than 30 medical centers in 10 countries. For this study, the researchers focused on 549 patients for whom surgeons had selected lightweight (34.2%) or midweight (47.7%) mesh. (The remaining 18.1% of cases used heavyweight mesh.)

Across the study groups, patients were similar for gender distribution; body mass index; race; and the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and immunosuppression – factors that can heavily influence wound repair.

In an initial analysis of the data, midweight mesh was associated with significantly fewer superficial surgical site infections (1.2%) than lightweight mesh (4.8%), as well as a significantly shorter length of stay (3.6 days vs 5.3 days). However, rates of postoperative abdominal wall complications, abscesses, urinary tract infection, pneumonia, hematoma formation, seroma formation, ileus, deep vein thrombosis, and unplanned returns to the operating room were similar.

At 6-month follow-up, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly greater mesh sensation, abdominal discomfort, and movement limitation, as well as significantly worse overall quality of life (QOL), than midweight mesh. At 12 months, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly greater pain and limitation of movement and significantly worse QOL. At 24 months, lightweight mesh continued to be associated with movement limitation, but scores on other measures were similar to those with midweight mesh.

In a multivariate analysis that controlled for many potentially confounding variables, including smoking status, separation of the components of the mesh, the number of sutures anchoring the mesh, and the mesh location within the abdomen, midweight mesh was not associated with worse QOL scores at any time point. In contrast, lightweight mesh was associated with significantly worse QOL scores at 6 months, with an odds ratio of 2.64, and with significantly more pain at 12 months, with an OR of 2.58, Dr. Groene and his associates said (Am J Surg. 2016 Dec;212[6]:1054-62).

The investigators also noted that among their own hernia repair patients, lightweight mesh tends to fracture more easily than midweight mesh. Recent studies also have reported that over time, lightweight mesh is more likely to fail due to fracturing than midweight mesh, they added.

This study had no relevant financial relationships or sources of support. Dr. Groene and his associates reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

FROM THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF SURGERY

Key clinical point: Compared with midweight mesh, lightweight mesh was associated with more surgical site infections and longer hospital stay in the short term and greater pain, more limitation of movement, and poorer quality of life for up to 2 years after open ventral hernia repair.

Major finding: In the short term, midweight mesh was associated with significantly fewer superficial surgical site infections (1.2%) than lightweight mesh (4.8%), as well as a significantly shorter length of stay (3.6 days vs 5.3 days).

Data source: An analysis of information in an international prospective registry of hernia mesh surgeries, which involved 549 adults.

Disclosures: This study had no relevant financial relationships or sources of support. Dr. Groene and his associates reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Mesh fixation method had no impact on chronic postop pain in TAPP

WASHINGTON – Mesh fixation technique is not a factor in persistent pain after transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) groin hernia surgery, a study showed.

“Persistent pain is a well-known phenomenon after groin hernia surgery,” said Jakob Burcharth, MD, of University Hospital of Sjaelland Koge (Denmark). “The way that we fixate the mesh in laparoscopic surgery has been hypothesized to have an [impact] on the risk of persistent pain.”

In a study presented by Dr. Burcharth and his associates at the American College of Surgeons Clinical Congress, a total of 1,421 patients were examined. Each patient completed a validated pain questionnaire through the Danish Hernia Database from 2009 to 2012. The patients were divided into two groups: Group 1 had spray fibrin sealant (34%) for mesh fixation, and group 2 had tacks (66%). The results showed no difference between the groups in terms of pain in getting up from a chair, sitting or standing for more than 30 minutes, walking stairs, driving a car, or exercising, or in the need for postoperative analgesics or postoperative sick leave (all P greater than .20).

Dr. Burcharth concluded that a high number of patients reported persistent pain regardless of mesh fixation technique, which emphasizes the need for preoperative information.

Dr. Burcharth reported having no relevant financial disclosures.

WASHINGTON – Mesh fixation technique is not a factor in persistent pain after transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) groin hernia surgery, a study showed.