User login

Researchers examine learning curve for gender-affirming vaginoplasty

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

FROM SGS 2020

Identifying ovarian malignancy is not so easy

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

How to evaluate a suspicious ovarian mass

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Patients may prefer retrograde-fill voiding trials after pelvic floor surgery

Voiding trials after female pelvic floor surgery may detect similar rates of voiding dysfunction regardless of whether voiding occurs spontaneously or after the bladder is retrograde-filled with saline, according to a randomized study.

Nevertheless, patients may prefer the more common retrograde-fill approach.

In the study of 109 patients, those who underwent retrograde fill reported significantly greater satisfaction with their method of voiding evaluation, compared with patients whose voiding trials occurred spontaneously. The increased satisfaction could relate to the fact that retrograde-fill trials take less time, study investigator Patrick Popiel, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., suggested at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. The exact reasons are unclear, however.

Voiding trials help identify patients who cannot sufficiently empty their bladder after surgery. Prior research has indicated that the incidence of voiding dysfunction after pelvic floor surgery is about 25%-35%. “Patients with voiding dysfunction are generally managed with an indwelling Foley catheter or clean intermittent self-catheterization,” Dr. Popiel said. “Catheterization increases the risk of urinary tract infection, increases anxiety, and decreases patient satisfaction. A large proportion of patients who are discharged home with a Foley catheter state that the catheter was the worst aspect of their experience.”

Dr. Popiel and colleagues conducted a randomized, prospective study to examine the rate of failed voiding trials that necessitate discharge home with an indwelling Foley catheter using spontaneous and retrograde-fill approaches. The study included women who required a voiding trial after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence. Patients who required prolonged catheterization after surgery, such as those with a urinary tract infection, bowel injury, or large amount of blood loss, were excluded.

Researchers analyzed data from 55 patients who were randomly assigned to the retrograde-fill group and 54 patients who were randomly assigned to the spontaneous trial group.

In the spontaneous group, patients were required to void at least 150 mL at one time within 6 hours of catheter removal to successfully complete the voiding trial.

In the retrograde-fill group, the bladder was filled in the postanesthesia care unit with 300 mL of saline or until the maximum volume tolerated by the patient (not exceeding 300 mL ) was reached. Patients in this group had to void at least 150 mL or 50% of the instilled volume at one time within 60 minutes of catheter removal to pass the trial.

The researchers documented postvoid residual (PVR) but did not use this measure to determine voiding function.

The baseline demographics of the two groups were similar, although prior hysterectomy was more common in the retrograde-fill group than in the spontaneous group (32.7% vs. 14.8%). The average age was 58.5 years in the retrograde-fill group and 61 years in the spontaneous group.

“There was no significant difference in our primary outcome,” Dr. Popiel said. “There was a 12.7% rate of failed voiding trial in the retrograde group versus 7.7% in the spontaneous group.”

No patients had urinary retention after initially passing their voiding trial. Force of stream did not differ between groups, and about 15% in each group had a postoperative urinary tract infection.

The study demonstrates that voiding assessment based on a spontaneous minimum void of 150 mL is safe and has similar pass rates, compared with the more commonly performed retrograde void trial, Dr. Popiel said. “If the voided amount is at least 150 mL, PVR is not critical to obtain. The study adds to the body of literature that supports less stringent criteria for evaluating voiding function and can limit postoperative urinary recatheterization.”

The investigators allowed patients with PVRs as high as 575 mL to return home without an alternative way to empty the bladder, C. Sage Claydon, MD, a urogynecologist who was not involved in the study, noted during a discussion after the presentation. In all, 6 patients who met the passing criteria for the spontaneous voiding trial had a PVR greater than 200 mL, with volumes ranging from 205-575 mL.

The patients received standardized counseling about postoperative voiding problems, said Dr. Popiel. “This is similar to the work done by Ingber et al. from 2011, where patients who reached a certain force of stream, greater than 5 out of 10, were discharged home regardless of PVR.”

Dr. Popiel had no relevant disclosures. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to BlossomMed, Renovia, and ArmadaHealth.

SOURCE: Popiel P et al. SGS 2020, Abstract 14.

Voiding trials after female pelvic floor surgery may detect similar rates of voiding dysfunction regardless of whether voiding occurs spontaneously or after the bladder is retrograde-filled with saline, according to a randomized study.

Nevertheless, patients may prefer the more common retrograde-fill approach.

In the study of 109 patients, those who underwent retrograde fill reported significantly greater satisfaction with their method of voiding evaluation, compared with patients whose voiding trials occurred spontaneously. The increased satisfaction could relate to the fact that retrograde-fill trials take less time, study investigator Patrick Popiel, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., suggested at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. The exact reasons are unclear, however.

Voiding trials help identify patients who cannot sufficiently empty their bladder after surgery. Prior research has indicated that the incidence of voiding dysfunction after pelvic floor surgery is about 25%-35%. “Patients with voiding dysfunction are generally managed with an indwelling Foley catheter or clean intermittent self-catheterization,” Dr. Popiel said. “Catheterization increases the risk of urinary tract infection, increases anxiety, and decreases patient satisfaction. A large proportion of patients who are discharged home with a Foley catheter state that the catheter was the worst aspect of their experience.”

Dr. Popiel and colleagues conducted a randomized, prospective study to examine the rate of failed voiding trials that necessitate discharge home with an indwelling Foley catheter using spontaneous and retrograde-fill approaches. The study included women who required a voiding trial after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence. Patients who required prolonged catheterization after surgery, such as those with a urinary tract infection, bowel injury, or large amount of blood loss, were excluded.

Researchers analyzed data from 55 patients who were randomly assigned to the retrograde-fill group and 54 patients who were randomly assigned to the spontaneous trial group.

In the spontaneous group, patients were required to void at least 150 mL at one time within 6 hours of catheter removal to successfully complete the voiding trial.

In the retrograde-fill group, the bladder was filled in the postanesthesia care unit with 300 mL of saline or until the maximum volume tolerated by the patient (not exceeding 300 mL ) was reached. Patients in this group had to void at least 150 mL or 50% of the instilled volume at one time within 60 minutes of catheter removal to pass the trial.

The researchers documented postvoid residual (PVR) but did not use this measure to determine voiding function.

The baseline demographics of the two groups were similar, although prior hysterectomy was more common in the retrograde-fill group than in the spontaneous group (32.7% vs. 14.8%). The average age was 58.5 years in the retrograde-fill group and 61 years in the spontaneous group.

“There was no significant difference in our primary outcome,” Dr. Popiel said. “There was a 12.7% rate of failed voiding trial in the retrograde group versus 7.7% in the spontaneous group.”

No patients had urinary retention after initially passing their voiding trial. Force of stream did not differ between groups, and about 15% in each group had a postoperative urinary tract infection.

The study demonstrates that voiding assessment based on a spontaneous minimum void of 150 mL is safe and has similar pass rates, compared with the more commonly performed retrograde void trial, Dr. Popiel said. “If the voided amount is at least 150 mL, PVR is not critical to obtain. The study adds to the body of literature that supports less stringent criteria for evaluating voiding function and can limit postoperative urinary recatheterization.”

The investigators allowed patients with PVRs as high as 575 mL to return home without an alternative way to empty the bladder, C. Sage Claydon, MD, a urogynecologist who was not involved in the study, noted during a discussion after the presentation. In all, 6 patients who met the passing criteria for the spontaneous voiding trial had a PVR greater than 200 mL, with volumes ranging from 205-575 mL.

The patients received standardized counseling about postoperative voiding problems, said Dr. Popiel. “This is similar to the work done by Ingber et al. from 2011, where patients who reached a certain force of stream, greater than 5 out of 10, were discharged home regardless of PVR.”

Dr. Popiel had no relevant disclosures. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to BlossomMed, Renovia, and ArmadaHealth.

SOURCE: Popiel P et al. SGS 2020, Abstract 14.

Voiding trials after female pelvic floor surgery may detect similar rates of voiding dysfunction regardless of whether voiding occurs spontaneously or after the bladder is retrograde-filled with saline, according to a randomized study.

Nevertheless, patients may prefer the more common retrograde-fill approach.

In the study of 109 patients, those who underwent retrograde fill reported significantly greater satisfaction with their method of voiding evaluation, compared with patients whose voiding trials occurred spontaneously. The increased satisfaction could relate to the fact that retrograde-fill trials take less time, study investigator Patrick Popiel, MD, of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., suggested at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. The exact reasons are unclear, however.

Voiding trials help identify patients who cannot sufficiently empty their bladder after surgery. Prior research has indicated that the incidence of voiding dysfunction after pelvic floor surgery is about 25%-35%. “Patients with voiding dysfunction are generally managed with an indwelling Foley catheter or clean intermittent self-catheterization,” Dr. Popiel said. “Catheterization increases the risk of urinary tract infection, increases anxiety, and decreases patient satisfaction. A large proportion of patients who are discharged home with a Foley catheter state that the catheter was the worst aspect of their experience.”

Dr. Popiel and colleagues conducted a randomized, prospective study to examine the rate of failed voiding trials that necessitate discharge home with an indwelling Foley catheter using spontaneous and retrograde-fill approaches. The study included women who required a voiding trial after surgery for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence. Patients who required prolonged catheterization after surgery, such as those with a urinary tract infection, bowel injury, or large amount of blood loss, were excluded.

Researchers analyzed data from 55 patients who were randomly assigned to the retrograde-fill group and 54 patients who were randomly assigned to the spontaneous trial group.

In the spontaneous group, patients were required to void at least 150 mL at one time within 6 hours of catheter removal to successfully complete the voiding trial.

In the retrograde-fill group, the bladder was filled in the postanesthesia care unit with 300 mL of saline or until the maximum volume tolerated by the patient (not exceeding 300 mL ) was reached. Patients in this group had to void at least 150 mL or 50% of the instilled volume at one time within 60 minutes of catheter removal to pass the trial.

The researchers documented postvoid residual (PVR) but did not use this measure to determine voiding function.

The baseline demographics of the two groups were similar, although prior hysterectomy was more common in the retrograde-fill group than in the spontaneous group (32.7% vs. 14.8%). The average age was 58.5 years in the retrograde-fill group and 61 years in the spontaneous group.

“There was no significant difference in our primary outcome,” Dr. Popiel said. “There was a 12.7% rate of failed voiding trial in the retrograde group versus 7.7% in the spontaneous group.”

No patients had urinary retention after initially passing their voiding trial. Force of stream did not differ between groups, and about 15% in each group had a postoperative urinary tract infection.

The study demonstrates that voiding assessment based on a spontaneous minimum void of 150 mL is safe and has similar pass rates, compared with the more commonly performed retrograde void trial, Dr. Popiel said. “If the voided amount is at least 150 mL, PVR is not critical to obtain. The study adds to the body of literature that supports less stringent criteria for evaluating voiding function and can limit postoperative urinary recatheterization.”

The investigators allowed patients with PVRs as high as 575 mL to return home without an alternative way to empty the bladder, C. Sage Claydon, MD, a urogynecologist who was not involved in the study, noted during a discussion after the presentation. In all, 6 patients who met the passing criteria for the spontaneous voiding trial had a PVR greater than 200 mL, with volumes ranging from 205-575 mL.

The patients received standardized counseling about postoperative voiding problems, said Dr. Popiel. “This is similar to the work done by Ingber et al. from 2011, where patients who reached a certain force of stream, greater than 5 out of 10, were discharged home regardless of PVR.”

Dr. Popiel had no relevant disclosures. Two coinvestigators disclosed ties to BlossomMed, Renovia, and ArmadaHealth.

SOURCE: Popiel P et al. SGS 2020, Abstract 14.

FROM SGS 2020

Molecular developments in treatment of UPSC

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is an infrequent but deadly form of endometrial cancer comprising 10% of cases but contributing 40% of deaths from the disease. Recurrence rates are high for this disease. Five-year survival is 55% for all patients and only 70% for stage I disease.1 Patterns of recurrence tend to be distant (extrapelvic and extraabdominal) as frequently as they are localized to the pelvis, and metastases and recurrences are unrelated to the extent of uterine disease (such as myometrial invasion). It is for these reasons that the recommended course of adjuvant therapy for this disease is systemic therapy (typically six doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy) with consideration for radiation to the vagina or pelvis to consolidate pelvic and vaginal control.2 This differs from early-stage high/intermediate–risk endometrioid adenocarcinomas, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has not been found to be helpful.

Because of the lower incidence of UPSC, it frequently has been studied alongside endometrioid cell types in clinical trials which explore novel adjuvant therapies. However, UPSC is biologically distinct from endometrioid endometrial cancers, which likely results in inferior clinical responses to conventional interventions. Fortunately we are beginning to better understand UPSC at a molecular level, and advancements are being made in the targeted therapies for these patients that are unique, compared with those applied to other cancer subtypes.

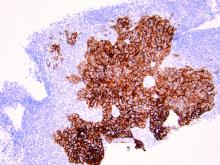

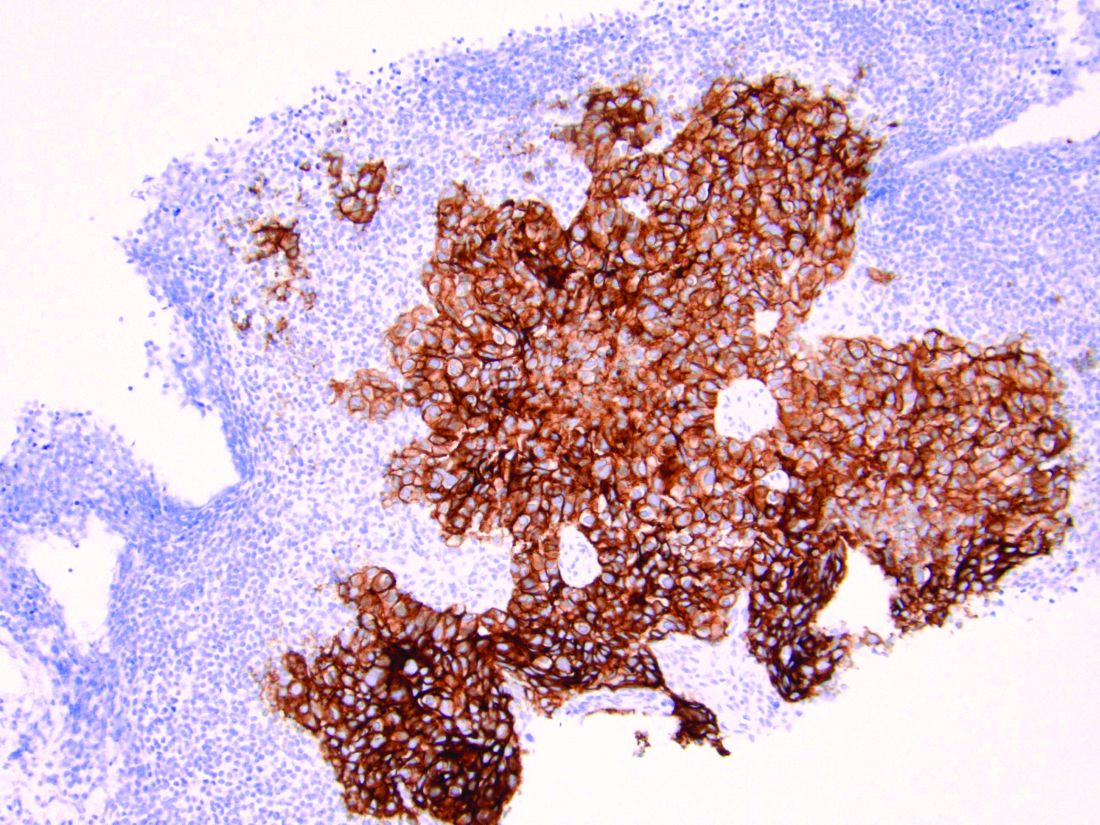

As discussed above, UPSC is a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer. Histologically it is characterized by a precursor lesion of endometrial glandular dysplasia progressing to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIC). Histologically it presents with a highly atypical slit-like glandular configuration, which appears similar to serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and ovary. Molecularly these tumors commonly manifest mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which are both genes associated with oncogenic potential.1 While most UPSC tumors have loss of expression in hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone, 25%-30% of cases overexpress the tyrosine kinase receptor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).3-5 This has proven to provide an exciting target for therapeutic interventions.

A target for therapeutic intervention

HER2 is a transmembrane receptor which, when activated, signals complex downstream pathways responsible for cellular proliferation, dedifferentiation, and metastasis. In a recent multi-institutional analysis of early-stage UPSC, HER2 overexpression was identified among 25% of cases.4 Approximately 30% of cases of advanced disease manifest overexpression of this biomarker.5 HER2 overexpression (HER2-positive status) is significantly associated with higher rates of recurrence and mortality, even among patients treated with conventional therapies.3 Thus HER2-positive status is obviously an indicator of particularly aggressive disease.

Fortunately this particular biomarker is one for which we have established and developing therapeutics. The humanized monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, has been highly effective in improving survival for HER2-positive breast cancer.6 More recently, it was studied in a phase 2 trial with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent HER2-positive UPSC.5 This trial showed that the addition of this targeted therapy to conventional chemotherapy improved recurrence-free survival from 8 months to 12 months, and improved overall survival from 24.4 months to 29.6 months.5

One discovery leads to another treatment

This discovery led to the approval of trastuzumab to be used in addition to chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent disease.2 The most significant effects appear to be among those who have not received prior therapies, with a doubling of progression-free survival among these patients, and a more modest response among patients treated for recurrent, mostly pretreated disease.