User login

Pembrolizumab showed ‘promising’ antitumor activity in small-cell lung cancer

One patient died of treatment-related mesenteric ischemia, reported Patrick A. Ott, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his associates. Nonetheless, with an objective response rate of 33% and a median duration of response of 19 months, the checkpoint inhibitor “demonstrated a favorable safety profile and promising durable clinical activity,” they concluded.

Study participants received pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg) every 2 weeks for 24 months or until disease progression or intolerable toxicity occurred. After a median follow-up of 9.8 months (range, 0.5-24 months), one patient (4%) had a complete response, and seven (29%) had partial responses. The median onset of response was 2 months, and responses lasted from 3.6 to 20 months, Dr. Ott and his associates reported (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.5069). Two-thirds of patients developed treatment-related adverse events, most often arthralgia, asthenia, rash, diarrhea, and fatigue. Two patients developed grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events, including a 65-year-old man with small cell lung cancer and liver metastasis who developed grade 3 bilirubin elevation, and a 58-year-old woman with a history of sleeve gastrectomy who developed grade 3 asthenia, grade 5 colitis, and intestinal ischemia.

The patient who died had received 10 cycles of pembrolizumab, was hospitalized with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, and was discharged home with a diagnosis of food intolerance, the researchers reported. She received an 11th cycle of pembrolizumab and was readmitted with abdominal pain. A rectal biopsy showed chronic colitis. She received systemic corticosteroids and was discharged, was admitted to a different hospital several weeks later with diffuse abdominal pain and septic shock, and subsequently died. “Mesenteric ischemia resulted in death,” the researchers wrote. “The cause of the colitis and intestinal ischemia was reported as probably related to pembrolizumab.”

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a programmed death receptor–1 blocking antibody approved for treating non–small cell lung cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability–high cancer or mismatch repair deficient solid tumors. Treatment with the checkpoint inhibitor led to grade 5 treatment-related adverse events in other trials. Most recently, in July 2017, the Food and Drug Administration placed clinical holds on phase 1 and phase 3 studies of pembrolizumab for treating multiple myeloma after more patients died in the pembrolizumab arms than did in the comparison arms. Pembrolizumab also recently came up short in a phase 3 trial of patients with head and neck cancer, although it has kept its FDA label for this indication. Multiple trials of pembrolizumab for small cell lung cancer are recruiting or ongoing.

Merck funded the study. Dr. Ott disclosed research funding from Merck and several other pharmaceutical companies, and advisory or consulting relationships with several companies, excluding Merck.

One patient died of treatment-related mesenteric ischemia, reported Patrick A. Ott, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his associates. Nonetheless, with an objective response rate of 33% and a median duration of response of 19 months, the checkpoint inhibitor “demonstrated a favorable safety profile and promising durable clinical activity,” they concluded.

Study participants received pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg) every 2 weeks for 24 months or until disease progression or intolerable toxicity occurred. After a median follow-up of 9.8 months (range, 0.5-24 months), one patient (4%) had a complete response, and seven (29%) had partial responses. The median onset of response was 2 months, and responses lasted from 3.6 to 20 months, Dr. Ott and his associates reported (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.5069). Two-thirds of patients developed treatment-related adverse events, most often arthralgia, asthenia, rash, diarrhea, and fatigue. Two patients developed grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events, including a 65-year-old man with small cell lung cancer and liver metastasis who developed grade 3 bilirubin elevation, and a 58-year-old woman with a history of sleeve gastrectomy who developed grade 3 asthenia, grade 5 colitis, and intestinal ischemia.

The patient who died had received 10 cycles of pembrolizumab, was hospitalized with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, and was discharged home with a diagnosis of food intolerance, the researchers reported. She received an 11th cycle of pembrolizumab and was readmitted with abdominal pain. A rectal biopsy showed chronic colitis. She received systemic corticosteroids and was discharged, was admitted to a different hospital several weeks later with diffuse abdominal pain and septic shock, and subsequently died. “Mesenteric ischemia resulted in death,” the researchers wrote. “The cause of the colitis and intestinal ischemia was reported as probably related to pembrolizumab.”

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a programmed death receptor–1 blocking antibody approved for treating non–small cell lung cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability–high cancer or mismatch repair deficient solid tumors. Treatment with the checkpoint inhibitor led to grade 5 treatment-related adverse events in other trials. Most recently, in July 2017, the Food and Drug Administration placed clinical holds on phase 1 and phase 3 studies of pembrolizumab for treating multiple myeloma after more patients died in the pembrolizumab arms than did in the comparison arms. Pembrolizumab also recently came up short in a phase 3 trial of patients with head and neck cancer, although it has kept its FDA label for this indication. Multiple trials of pembrolizumab for small cell lung cancer are recruiting or ongoing.

Merck funded the study. Dr. Ott disclosed research funding from Merck and several other pharmaceutical companies, and advisory or consulting relationships with several companies, excluding Merck.

One patient died of treatment-related mesenteric ischemia, reported Patrick A. Ott, MD, of Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, and his associates. Nonetheless, with an objective response rate of 33% and a median duration of response of 19 months, the checkpoint inhibitor “demonstrated a favorable safety profile and promising durable clinical activity,” they concluded.

Study participants received pembrolizumab (10 mg/kg) every 2 weeks for 24 months or until disease progression or intolerable toxicity occurred. After a median follow-up of 9.8 months (range, 0.5-24 months), one patient (4%) had a complete response, and seven (29%) had partial responses. The median onset of response was 2 months, and responses lasted from 3.6 to 20 months, Dr. Ott and his associates reported (J Clin Oncol. 2017 Aug 16. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.5069). Two-thirds of patients developed treatment-related adverse events, most often arthralgia, asthenia, rash, diarrhea, and fatigue. Two patients developed grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events, including a 65-year-old man with small cell lung cancer and liver metastasis who developed grade 3 bilirubin elevation, and a 58-year-old woman with a history of sleeve gastrectomy who developed grade 3 asthenia, grade 5 colitis, and intestinal ischemia.

The patient who died had received 10 cycles of pembrolizumab, was hospitalized with abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, and was discharged home with a diagnosis of food intolerance, the researchers reported. She received an 11th cycle of pembrolizumab and was readmitted with abdominal pain. A rectal biopsy showed chronic colitis. She received systemic corticosteroids and was discharged, was admitted to a different hospital several weeks later with diffuse abdominal pain and septic shock, and subsequently died. “Mesenteric ischemia resulted in death,” the researchers wrote. “The cause of the colitis and intestinal ischemia was reported as probably related to pembrolizumab.”

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) is a programmed death receptor–1 blocking antibody approved for treating non–small cell lung cancer, head and neck squamous cell cancer, classical Hodgkin lymphoma, urothelial carcinoma, and microsatellite instability–high cancer or mismatch repair deficient solid tumors. Treatment with the checkpoint inhibitor led to grade 5 treatment-related adverse events in other trials. Most recently, in July 2017, the Food and Drug Administration placed clinical holds on phase 1 and phase 3 studies of pembrolizumab for treating multiple myeloma after more patients died in the pembrolizumab arms than did in the comparison arms. Pembrolizumab also recently came up short in a phase 3 trial of patients with head and neck cancer, although it has kept its FDA label for this indication. Multiple trials of pembrolizumab for small cell lung cancer are recruiting or ongoing.

Merck funded the study. Dr. Ott disclosed research funding from Merck and several other pharmaceutical companies, and advisory or consulting relationships with several companies, excluding Merck.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Key clinical point: Pembrolizumab showed antitumor activity and was usually safe for treating extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

Major finding: The objective response rate was 33%. Two patients developed grade 3 or worse treatment-related adverse events, which included fatal mesenteric ischemia and colitis.

Data source: A phase 1b open-label trial of 24 patients with PD-L1–positive extensive-stage small cell lung cancer.

Disclosures: Merck funded the study. Dr. Ott disclosed research funding from Merck and several other pharmaceutical companies, and advisory or consulting relationships with several companies, excluding Merck.

Intraoperative ketamine makes no dent in postop delirium or pain

Postoperative delirium remains a problem without an effective solution, wrote Michael S. Avidan, MBBCh, FCASA, of Washington University, Saint Louis, and his colleagues (Lancet 2017;390[10091]:267-75).

Recent guidelines published by the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council include ketamine as a recommended component of multimodal pain therapy for several commonly performed surgeries. “Before recommending widespread administration of an intraoperative bolus of subanaesthetic ketamine, demonstrating that ketamine decreases either delirium or pain, or both, without incurring adverse effects in a large, pragmatic trial was warranted,” the researchers said.

In the PODCAST (Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated With Surgical Treatments) trial, the researchers randomized 672 patients over the age of 60 undergoing major open surgery under general anesthesia (such as open cardiac or noncardiac surgery, urological surgery, gynecologic surgery, or intra-abdominal surgery) to 0.5 mg/kg ketamine (227), 1.0 mg/kg ketamine (223), or placebo (222). The ketamine or placebo was given after anesthesia and before surgical incision.

Overall, no difference in the incidence of delirium occurred between patients in the combined ketamine groups (19.5%) and the placebo group (19.8%), and there was no significant difference in delirium across all three treatment groups.

No differences in pain based on visual analog scale scores were observed across the three groups, and overall adverse event rates were similar as well: approximately 40.8% in the 1.0-mg ketamine group, 39.6% in the 0.5-mg ketamine group, and 36.9% in the placebo group.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including a study population potentially too small to show an effect of ketamine on delirium, and a lack of data on other variables that might contribute to delirium and pain, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that “despite present evidence and guidelines, the administration of a subanaesthetic ketamine dose during surgery is not useful for preventing postoperative delirium (primary outcome) or reducing postoperative pain and minimising opioid consumption (related secondary outcomes),” and appears to increase postoperative hallucinations and nightmares to an extent that might be prohibitive, they said.

The National Institutes of Health and Cancer Center Support funded the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Postoperative delirium remains a problem without an effective solution, wrote Michael S. Avidan, MBBCh, FCASA, of Washington University, Saint Louis, and his colleagues (Lancet 2017;390[10091]:267-75).

Recent guidelines published by the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council include ketamine as a recommended component of multimodal pain therapy for several commonly performed surgeries. “Before recommending widespread administration of an intraoperative bolus of subanaesthetic ketamine, demonstrating that ketamine decreases either delirium or pain, or both, without incurring adverse effects in a large, pragmatic trial was warranted,” the researchers said.

In the PODCAST (Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated With Surgical Treatments) trial, the researchers randomized 672 patients over the age of 60 undergoing major open surgery under general anesthesia (such as open cardiac or noncardiac surgery, urological surgery, gynecologic surgery, or intra-abdominal surgery) to 0.5 mg/kg ketamine (227), 1.0 mg/kg ketamine (223), or placebo (222). The ketamine or placebo was given after anesthesia and before surgical incision.

Overall, no difference in the incidence of delirium occurred between patients in the combined ketamine groups (19.5%) and the placebo group (19.8%), and there was no significant difference in delirium across all three treatment groups.

No differences in pain based on visual analog scale scores were observed across the three groups, and overall adverse event rates were similar as well: approximately 40.8% in the 1.0-mg ketamine group, 39.6% in the 0.5-mg ketamine group, and 36.9% in the placebo group.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including a study population potentially too small to show an effect of ketamine on delirium, and a lack of data on other variables that might contribute to delirium and pain, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that “despite present evidence and guidelines, the administration of a subanaesthetic ketamine dose during surgery is not useful for preventing postoperative delirium (primary outcome) or reducing postoperative pain and minimising opioid consumption (related secondary outcomes),” and appears to increase postoperative hallucinations and nightmares to an extent that might be prohibitive, they said.

The National Institutes of Health and Cancer Center Support funded the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Postoperative delirium remains a problem without an effective solution, wrote Michael S. Avidan, MBBCh, FCASA, of Washington University, Saint Louis, and his colleagues (Lancet 2017;390[10091]:267-75).

Recent guidelines published by the American Pain Society, the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Regional Anesthesia, Executive Committee, and Administrative Council include ketamine as a recommended component of multimodal pain therapy for several commonly performed surgeries. “Before recommending widespread administration of an intraoperative bolus of subanaesthetic ketamine, demonstrating that ketamine decreases either delirium or pain, or both, without incurring adverse effects in a large, pragmatic trial was warranted,” the researchers said.

In the PODCAST (Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated With Surgical Treatments) trial, the researchers randomized 672 patients over the age of 60 undergoing major open surgery under general anesthesia (such as open cardiac or noncardiac surgery, urological surgery, gynecologic surgery, or intra-abdominal surgery) to 0.5 mg/kg ketamine (227), 1.0 mg/kg ketamine (223), or placebo (222). The ketamine or placebo was given after anesthesia and before surgical incision.

Overall, no difference in the incidence of delirium occurred between patients in the combined ketamine groups (19.5%) and the placebo group (19.8%), and there was no significant difference in delirium across all three treatment groups.

No differences in pain based on visual analog scale scores were observed across the three groups, and overall adverse event rates were similar as well: approximately 40.8% in the 1.0-mg ketamine group, 39.6% in the 0.5-mg ketamine group, and 36.9% in the placebo group.

The study findings were limited by several factors, including a study population potentially too small to show an effect of ketamine on delirium, and a lack of data on other variables that might contribute to delirium and pain, the researchers noted. However, the results suggest that “despite present evidence and guidelines, the administration of a subanaesthetic ketamine dose during surgery is not useful for preventing postoperative delirium (primary outcome) or reducing postoperative pain and minimising opioid consumption (related secondary outcomes),” and appears to increase postoperative hallucinations and nightmares to an extent that might be prohibitive, they said.

The National Institutes of Health and Cancer Center Support funded the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM THE LANCET

Key clinical point: Ketamine failed to reduce postoperative delirium in older adults.

Major finding: No difference was observed in the incidence of postoperative delirium between patients given ketamine before surgical incision and patients on placebo.

Data source: The Prevention of Delirium and Complications Associated With Surgical Treatments study, a randomized, multicenter trial of 672 adults older than 60 years.

Disclosures: The National Institutes of Health and Cancer Center Support funded the study. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Cancer screening in elderly: When to just say no

ESTES PARK, COLO. – A simple walking speed measurement over a 20-foot distance is an invaluable guide to physiologic age as part of individualized decision making about when to stop cancer screening in elderly patients, according to Jeff Wallace, MD, professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver.

“If you have one measurement to assess ‘am I aging well?’ it’s your gait speed. A lot of us in geriatrics are advocating evaluation of gait speed in all patients as a fifth vital sign. It’s probably more useful than blood pressure in some of the older adults coming into our clinics,” he said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Dr. Wallace also gave a shout-out to the ePrognosis cancer-screening decision tool, available free at www.eprognosis.org, as an aid in shared decision-making conversations regarding when to stop cancer screening. This tool, developed by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, allows physicians to plug key individual patient characteristics into its model, including comorbid conditions, functional status, and body mass index, and then spits out data-driven estimated benefits and harms a patient can expect from advanced-age screening for colon or breast cancer.

Of course, guidelines as to when to stop screening for various cancers are available from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American Cancer Society, and specialty societies. However, it’s important that nongeriatricians understand the serious limitations of those guidelines.

“We’re not guidelines followers in the geriatrics world because the guidelines don’t apply to most of our patients,” he explained. “We hate guidelines in geriatrics because few studies – and no lung cancer or breast cancer trials – enroll patients over age 75 with comorbid conditions. Also, most of these guidelines do not incorporate patient preferences, which probably should be a primary goal. So we’re left extrapolating.“

Regrettably, though, “it turns out most Americans are drinking the Kool-Aid when it comes to patient preferences. It’s amazing how much cancer screening is going on in this country. We’re doing a lot more than we should,” said Dr. Wallace.

All of that is clearly overscreening. Experts unanimously agree that if someone is not going to live for 10 years, that person is not likely to benefit from cancer screening. The one exception is lung cancer screening of high-risk patients, where there are data to show that annual low-dose CT screening is beneficial in those with even a 5-year life expectancy.

As part of the Choosing Wisely program, the American Geriatric Society has advocated that physicians “don’t recommend screening for breast, colorectal, prostate, or lung cancer without considering life expectancy and the risks of testing, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment.”

That’s where gait speed and ePrognosis come in handy in discussions with patients regarding what they can realistically expect from cancer screening at an advanced age.

The importance of gait speed was highlighted in a pooled analysis of nine cohort studies totaling more than 34,000 community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older with 6-21 years of follow-up. Investigators at the University of Pittsburgh identified a strong relationship between gait speed and survival. Every 0.1-m/sec made a significant difference (JAMA. 2011 Jan 5;305[1]:50-8).

A gait speed evaluation is simple: The patient is asked to walk 20 feet at a normal speed, not racing. For men age 75, the Pittsburgh investigators found, gait speed predicted 10-year survival across a range of 19%-87%. The median speed was 0.8 m/sec, or about 1.8 mph, so a middle-of-the-pack walker ought to stop all cancer screening by age 75. A fast-walking older man won’t reach a 10-year remaining life expectancy until he’s in his early to mid-80s; a slow walker reaches that life expectancy as early as his late 60s, depending upon just how slow he walks. A woman at age 80 with an average gait speed has roughly 10 years of remaining life, factoring in plus or minus 5 years from that landmark depending upon whether she is a faster- or slower-than-average walker, Dr. Wallace explained.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force currently recommends colon cancer screening routinely for 50- to 75-year-olds, declaring in accord with other groups that this strategy has a high certainty of substantial net benefit. But the USPSTF also recommends selective screening for those aged 76-85, with a weaker C recommendation (JAMA. 2016 Jun 21;315[23]:2564-75).

What are the practical implications of that recommendation for selective screening after age 75?

Investigators at Harvard Medical School and the University of Oslo recently took a closer look. Their population-based, prospective, observational study included 1,355,692 Medicare beneficiaries aged 70-79 years at average risk for colorectal cancer who had not had a colonoscopy within the previous 5 years.

The investigators demonstrated that the benefit of screening colonoscopy decreased with age. For patients aged 70-74, the 8-year risk of colorectal cancer was 2.19% in those who were screened, compared with 2.62% in those who weren’t, for an absolute 0.43% difference. The number needed to be screened to detect one additional case of colorectal cancer was 283. Among those aged 75-79, the number needed to be screened climbed to 714 (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 3;166[1]18-26).

Moreover, the risk of colonoscopy-related adverse events also climbed with age. These included perforations, falls while racing to the bathroom during the preprocedural bowel prep, and the humiliation of fecal incontinence. The excess 30-day risk for any adverse event in the colonoscopy group was 5.6 events per 1,000 patients aged 70-74 and 10.3 per 1,000 in 75- to 79-year-olds.

In a similar vein, Mara A. Schonberg, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, has shed light on the risks and benefits of biannual mammographic screening for breast cancer in 70- to 79-year-olds, a practice recommended in American Cancer Society guidelines for women who are in overall good health and have at least a 10-year life expectancy.

She estimated that 2 women per 1,000 screened would avoid death due to breast cancer, for a number needed to screen of 500. But roughly 200 of those 1,000 women would experience a false-positive mammogram, and 20-40 of those false-positive imaging studies would result in a breast biopsy. Also, roughly 30% of the screen-detected cancers would not otherwise become apparent in an older woman’s lifetime, yet nearly all of the malignancies would undergo breast cancer therapy (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016 Dec;64[12]:2413-8).

Dr. Schonberg’s research speaks to Dr. Wallace.

“It’s breast cancer therapy: It’s procedures; it’s medicalizing the patient’s whole life and creating a high degree of angst when she’s 75 or 80,” he said.

As to when to ‘just say no’ to cancer screening, Dr. Wallace said his answer is after age 65 for cervical cancer screening in women with at least two normal screens in the past 10 years or a prior total hysterectomy for a benign indication. All of the guidelines agree on that, although the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends in addition that women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 be screened for the next 20 years.

For prostate cancer, Dr. Wallace recommends his colleagues just say no to screening at age 70 and above because harm is more likely than benefit to ensue.

“I don’t know about you, but I have a ton of patients over age 70 asking me for PSAs. That’s one place I won’t do any screening. I tell them I know you’re in great shape for 76 and you think it’s a good idea, but I think it’s bad medicine and I won’t do it. Even the American Urological Association says don’t do it after age 70,” he said.

For prostate cancer screening at age 55-69, however, patient preference rules the day, he added.

He draws the line at any cancer screening in patients aged 90 or over. Mean survival at age 90 is another 4-5 years. Only 11% of 90-year-old women will reach 100.

“Everybody has to die eventually,” he mused.

Dr. Wallace reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – A simple walking speed measurement over a 20-foot distance is an invaluable guide to physiologic age as part of individualized decision making about when to stop cancer screening in elderly patients, according to Jeff Wallace, MD, professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver.

“If you have one measurement to assess ‘am I aging well?’ it’s your gait speed. A lot of us in geriatrics are advocating evaluation of gait speed in all patients as a fifth vital sign. It’s probably more useful than blood pressure in some of the older adults coming into our clinics,” he said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Dr. Wallace also gave a shout-out to the ePrognosis cancer-screening decision tool, available free at www.eprognosis.org, as an aid in shared decision-making conversations regarding when to stop cancer screening. This tool, developed by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, allows physicians to plug key individual patient characteristics into its model, including comorbid conditions, functional status, and body mass index, and then spits out data-driven estimated benefits and harms a patient can expect from advanced-age screening for colon or breast cancer.

Of course, guidelines as to when to stop screening for various cancers are available from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American Cancer Society, and specialty societies. However, it’s important that nongeriatricians understand the serious limitations of those guidelines.

“We’re not guidelines followers in the geriatrics world because the guidelines don’t apply to most of our patients,” he explained. “We hate guidelines in geriatrics because few studies – and no lung cancer or breast cancer trials – enroll patients over age 75 with comorbid conditions. Also, most of these guidelines do not incorporate patient preferences, which probably should be a primary goal. So we’re left extrapolating.“

Regrettably, though, “it turns out most Americans are drinking the Kool-Aid when it comes to patient preferences. It’s amazing how much cancer screening is going on in this country. We’re doing a lot more than we should,” said Dr. Wallace.

All of that is clearly overscreening. Experts unanimously agree that if someone is not going to live for 10 years, that person is not likely to benefit from cancer screening. The one exception is lung cancer screening of high-risk patients, where there are data to show that annual low-dose CT screening is beneficial in those with even a 5-year life expectancy.

As part of the Choosing Wisely program, the American Geriatric Society has advocated that physicians “don’t recommend screening for breast, colorectal, prostate, or lung cancer without considering life expectancy and the risks of testing, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment.”

That’s where gait speed and ePrognosis come in handy in discussions with patients regarding what they can realistically expect from cancer screening at an advanced age.

The importance of gait speed was highlighted in a pooled analysis of nine cohort studies totaling more than 34,000 community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older with 6-21 years of follow-up. Investigators at the University of Pittsburgh identified a strong relationship between gait speed and survival. Every 0.1-m/sec made a significant difference (JAMA. 2011 Jan 5;305[1]:50-8).

A gait speed evaluation is simple: The patient is asked to walk 20 feet at a normal speed, not racing. For men age 75, the Pittsburgh investigators found, gait speed predicted 10-year survival across a range of 19%-87%. The median speed was 0.8 m/sec, or about 1.8 mph, so a middle-of-the-pack walker ought to stop all cancer screening by age 75. A fast-walking older man won’t reach a 10-year remaining life expectancy until he’s in his early to mid-80s; a slow walker reaches that life expectancy as early as his late 60s, depending upon just how slow he walks. A woman at age 80 with an average gait speed has roughly 10 years of remaining life, factoring in plus or minus 5 years from that landmark depending upon whether she is a faster- or slower-than-average walker, Dr. Wallace explained.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force currently recommends colon cancer screening routinely for 50- to 75-year-olds, declaring in accord with other groups that this strategy has a high certainty of substantial net benefit. But the USPSTF also recommends selective screening for those aged 76-85, with a weaker C recommendation (JAMA. 2016 Jun 21;315[23]:2564-75).

What are the practical implications of that recommendation for selective screening after age 75?

Investigators at Harvard Medical School and the University of Oslo recently took a closer look. Their population-based, prospective, observational study included 1,355,692 Medicare beneficiaries aged 70-79 years at average risk for colorectal cancer who had not had a colonoscopy within the previous 5 years.

The investigators demonstrated that the benefit of screening colonoscopy decreased with age. For patients aged 70-74, the 8-year risk of colorectal cancer was 2.19% in those who were screened, compared with 2.62% in those who weren’t, for an absolute 0.43% difference. The number needed to be screened to detect one additional case of colorectal cancer was 283. Among those aged 75-79, the number needed to be screened climbed to 714 (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 3;166[1]18-26).

Moreover, the risk of colonoscopy-related adverse events also climbed with age. These included perforations, falls while racing to the bathroom during the preprocedural bowel prep, and the humiliation of fecal incontinence. The excess 30-day risk for any adverse event in the colonoscopy group was 5.6 events per 1,000 patients aged 70-74 and 10.3 per 1,000 in 75- to 79-year-olds.

In a similar vein, Mara A. Schonberg, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, has shed light on the risks and benefits of biannual mammographic screening for breast cancer in 70- to 79-year-olds, a practice recommended in American Cancer Society guidelines for women who are in overall good health and have at least a 10-year life expectancy.

She estimated that 2 women per 1,000 screened would avoid death due to breast cancer, for a number needed to screen of 500. But roughly 200 of those 1,000 women would experience a false-positive mammogram, and 20-40 of those false-positive imaging studies would result in a breast biopsy. Also, roughly 30% of the screen-detected cancers would not otherwise become apparent in an older woman’s lifetime, yet nearly all of the malignancies would undergo breast cancer therapy (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016 Dec;64[12]:2413-8).

Dr. Schonberg’s research speaks to Dr. Wallace.

“It’s breast cancer therapy: It’s procedures; it’s medicalizing the patient’s whole life and creating a high degree of angst when she’s 75 or 80,” he said.

As to when to ‘just say no’ to cancer screening, Dr. Wallace said his answer is after age 65 for cervical cancer screening in women with at least two normal screens in the past 10 years or a prior total hysterectomy for a benign indication. All of the guidelines agree on that, although the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends in addition that women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 be screened for the next 20 years.

For prostate cancer, Dr. Wallace recommends his colleagues just say no to screening at age 70 and above because harm is more likely than benefit to ensue.

“I don’t know about you, but I have a ton of patients over age 70 asking me for PSAs. That’s one place I won’t do any screening. I tell them I know you’re in great shape for 76 and you think it’s a good idea, but I think it’s bad medicine and I won’t do it. Even the American Urological Association says don’t do it after age 70,” he said.

For prostate cancer screening at age 55-69, however, patient preference rules the day, he added.

He draws the line at any cancer screening in patients aged 90 or over. Mean survival at age 90 is another 4-5 years. Only 11% of 90-year-old women will reach 100.

“Everybody has to die eventually,” he mused.

Dr. Wallace reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

ESTES PARK, COLO. – A simple walking speed measurement over a 20-foot distance is an invaluable guide to physiologic age as part of individualized decision making about when to stop cancer screening in elderly patients, according to Jeff Wallace, MD, professor of geriatric medicine at the University of Colorado at Denver.

“If you have one measurement to assess ‘am I aging well?’ it’s your gait speed. A lot of us in geriatrics are advocating evaluation of gait speed in all patients as a fifth vital sign. It’s probably more useful than blood pressure in some of the older adults coming into our clinics,” he said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

Dr. Wallace also gave a shout-out to the ePrognosis cancer-screening decision tool, available free at www.eprognosis.org, as an aid in shared decision-making conversations regarding when to stop cancer screening. This tool, developed by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, allows physicians to plug key individual patient characteristics into its model, including comorbid conditions, functional status, and body mass index, and then spits out data-driven estimated benefits and harms a patient can expect from advanced-age screening for colon or breast cancer.

Of course, guidelines as to when to stop screening for various cancers are available from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, the American Cancer Society, and specialty societies. However, it’s important that nongeriatricians understand the serious limitations of those guidelines.

“We’re not guidelines followers in the geriatrics world because the guidelines don’t apply to most of our patients,” he explained. “We hate guidelines in geriatrics because few studies – and no lung cancer or breast cancer trials – enroll patients over age 75 with comorbid conditions. Also, most of these guidelines do not incorporate patient preferences, which probably should be a primary goal. So we’re left extrapolating.“

Regrettably, though, “it turns out most Americans are drinking the Kool-Aid when it comes to patient preferences. It’s amazing how much cancer screening is going on in this country. We’re doing a lot more than we should,” said Dr. Wallace.

All of that is clearly overscreening. Experts unanimously agree that if someone is not going to live for 10 years, that person is not likely to benefit from cancer screening. The one exception is lung cancer screening of high-risk patients, where there are data to show that annual low-dose CT screening is beneficial in those with even a 5-year life expectancy.

As part of the Choosing Wisely program, the American Geriatric Society has advocated that physicians “don’t recommend screening for breast, colorectal, prostate, or lung cancer without considering life expectancy and the risks of testing, overdiagnosis, and overtreatment.”

That’s where gait speed and ePrognosis come in handy in discussions with patients regarding what they can realistically expect from cancer screening at an advanced age.

The importance of gait speed was highlighted in a pooled analysis of nine cohort studies totaling more than 34,000 community-dwelling adults aged 65 years and older with 6-21 years of follow-up. Investigators at the University of Pittsburgh identified a strong relationship between gait speed and survival. Every 0.1-m/sec made a significant difference (JAMA. 2011 Jan 5;305[1]:50-8).

A gait speed evaluation is simple: The patient is asked to walk 20 feet at a normal speed, not racing. For men age 75, the Pittsburgh investigators found, gait speed predicted 10-year survival across a range of 19%-87%. The median speed was 0.8 m/sec, or about 1.8 mph, so a middle-of-the-pack walker ought to stop all cancer screening by age 75. A fast-walking older man won’t reach a 10-year remaining life expectancy until he’s in his early to mid-80s; a slow walker reaches that life expectancy as early as his late 60s, depending upon just how slow he walks. A woman at age 80 with an average gait speed has roughly 10 years of remaining life, factoring in plus or minus 5 years from that landmark depending upon whether she is a faster- or slower-than-average walker, Dr. Wallace explained.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force currently recommends colon cancer screening routinely for 50- to 75-year-olds, declaring in accord with other groups that this strategy has a high certainty of substantial net benefit. But the USPSTF also recommends selective screening for those aged 76-85, with a weaker C recommendation (JAMA. 2016 Jun 21;315[23]:2564-75).

What are the practical implications of that recommendation for selective screening after age 75?

Investigators at Harvard Medical School and the University of Oslo recently took a closer look. Their population-based, prospective, observational study included 1,355,692 Medicare beneficiaries aged 70-79 years at average risk for colorectal cancer who had not had a colonoscopy within the previous 5 years.

The investigators demonstrated that the benefit of screening colonoscopy decreased with age. For patients aged 70-74, the 8-year risk of colorectal cancer was 2.19% in those who were screened, compared with 2.62% in those who weren’t, for an absolute 0.43% difference. The number needed to be screened to detect one additional case of colorectal cancer was 283. Among those aged 75-79, the number needed to be screened climbed to 714 (Ann Intern Med. 2017 Jan 3;166[1]18-26).

Moreover, the risk of colonoscopy-related adverse events also climbed with age. These included perforations, falls while racing to the bathroom during the preprocedural bowel prep, and the humiliation of fecal incontinence. The excess 30-day risk for any adverse event in the colonoscopy group was 5.6 events per 1,000 patients aged 70-74 and 10.3 per 1,000 in 75- to 79-year-olds.

In a similar vein, Mara A. Schonberg, MD, of Harvard Medical School, Boston, has shed light on the risks and benefits of biannual mammographic screening for breast cancer in 70- to 79-year-olds, a practice recommended in American Cancer Society guidelines for women who are in overall good health and have at least a 10-year life expectancy.

She estimated that 2 women per 1,000 screened would avoid death due to breast cancer, for a number needed to screen of 500. But roughly 200 of those 1,000 women would experience a false-positive mammogram, and 20-40 of those false-positive imaging studies would result in a breast biopsy. Also, roughly 30% of the screen-detected cancers would not otherwise become apparent in an older woman’s lifetime, yet nearly all of the malignancies would undergo breast cancer therapy (J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016 Dec;64[12]:2413-8).

Dr. Schonberg’s research speaks to Dr. Wallace.

“It’s breast cancer therapy: It’s procedures; it’s medicalizing the patient’s whole life and creating a high degree of angst when she’s 75 or 80,” he said.

As to when to ‘just say no’ to cancer screening, Dr. Wallace said his answer is after age 65 for cervical cancer screening in women with at least two normal screens in the past 10 years or a prior total hysterectomy for a benign indication. All of the guidelines agree on that, although the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends in addition that women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2 be screened for the next 20 years.

For prostate cancer, Dr. Wallace recommends his colleagues just say no to screening at age 70 and above because harm is more likely than benefit to ensue.

“I don’t know about you, but I have a ton of patients over age 70 asking me for PSAs. That’s one place I won’t do any screening. I tell them I know you’re in great shape for 76 and you think it’s a good idea, but I think it’s bad medicine and I won’t do it. Even the American Urological Association says don’t do it after age 70,” he said.

For prostate cancer screening at age 55-69, however, patient preference rules the day, he added.

He draws the line at any cancer screening in patients aged 90 or over. Mean survival at age 90 is another 4-5 years. Only 11% of 90-year-old women will reach 100.

“Everybody has to die eventually,” he mused.

Dr. Wallace reported having no financial conflicts regarding his presentation.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL INTERNAL MEDICINE PROGRAM

Wide variability found in invasive mediastinal staging rates for lung cancer

COLORADO SPRINGS – Significant variability exists between hospitals in Washington state in their rates of invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer, Farhood Farjah, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

“We found evidence of a fivefold variation in hospital-level rates of invasive mediastinal staging not explained by chance or case mix,” according to Dr. Farjah of the University of Washington, Seattle.

“This has led to substantial concerns about quality of thoracic surgical care in the community at large,” he noted.

The Washington study is the first to show hospital-by-hospital variation in rates of invasive mediastinal staging.

Invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer is considered important because imaging is known to have a substantial false-negative rate, and staging results have a profound impact on treatment recommendations, which can range from surgery alone to additional chemoradiation therapy.

Yet the meaning of the hospital-level huge variability in practice observed in the Washington study remains unclear.

“Our understanding of the underutilization of invasive mediastinal staging is further complicated by the fact that patterns of invasive mediastinal staging are highly variable across hospitals staffed by at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice,” Dr. Farjah explained. “This variability could be a marker of poor-quality care. However, because the guidelines are not supported by level 1 evidence, it’s equally plausible that this variability might represent uncertainty or even disagreement with the practice guidelines – and specifically about the appropriate indication for invasive staging.”

He presented a retrospective cohort study of 406 patients whose non–small cell lung cancer was resected during July 2011–December 2013 at one of five Washington hospitals, each with at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice on staff. The four participating community hospitals and one academic medical center were involved in a National Cancer Institute–funded, physician-led quality improvement initiative.

Overall, 66% of the 406 patients underwent any form of invasive mediastinal staging: 85% by mediastinoscopy only; 12% by mediastinoscopy plus endobronchial ultrasound-guided nodal aspiration (EBUS); 3% by EBUS only; and the remaining handful by mediastinoscopy, EBUS, and esophageal ultrasound-guided nodal aspiration. The invasive staging was performed at the time of resection in 64% of cases. A median of three nodal stations were sampled.

After statistical adjustment for random variation and between-hospital differences in clinical stage, rates of invasive staging were all over the map. While an overall mean of 66% of the lung cancer patients underwent invasive mediastinal staging, the rates at the five hospitals were 94%, 84%, 31%, 80%, and 17%.

Dr. Farjah and his coinvestigators are now conducting provider interviews and focus groups in an effort to understand what drove the participating surgeons’ wide variability in performing invasive mediastinal staging.

Discussant Jane Yanagawa, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, commented, “I think this is a really interesting study because, historically, lower rates of mediastinoscopy are assumed to be a reflection of low-quality care – and you suggest that might not be the case, that it might be more complicated than that.”

Dr. Yanagawa sketched one fairly common scenario that might represent a surgeon’s reasonable avoidance of guideline-recommended invasive mediastinal staging: a patient who by all preoperative imaging appears to have stage IA lung cancer and wishes to avoid the morbidity, time, and cost of needle biopsy, instead choosing to go straight to the operating room for a diagnosis by wedge resection, followed by a completion lobectomy based upon the frozen section results. Could such a pathway account for the variability seen in the Washington study?

“I think it could have,” Dr. Farjah replied. “I would say that’s probably one driver of variability.”

As for the generalizability of the findings of a five-hospital study carried out in a single state, Dr. Farjah said he thinks the results are applicable to any academic or community hospital with at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study.

M. Patricia Rivera, MD, FCCP, comments: Staging of lung cancer is essential to select the best treatment strategy for a given patient. However, despite multiple guideline recommendations

M. Patricia Rivera, MD, FCCP, comments: Staging of lung cancer is essential to select the best treatment strategy for a given patient. However, despite multiple guideline recommendations

M. Patricia Rivera, MD, FCCP, comments: Staging of lung cancer is essential to select the best treatment strategy for a given patient. However, despite multiple guideline recommendations

COLORADO SPRINGS – Significant variability exists between hospitals in Washington state in their rates of invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer, Farhood Farjah, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

“We found evidence of a fivefold variation in hospital-level rates of invasive mediastinal staging not explained by chance or case mix,” according to Dr. Farjah of the University of Washington, Seattle.

“This has led to substantial concerns about quality of thoracic surgical care in the community at large,” he noted.

The Washington study is the first to show hospital-by-hospital variation in rates of invasive mediastinal staging.

Invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer is considered important because imaging is known to have a substantial false-negative rate, and staging results have a profound impact on treatment recommendations, which can range from surgery alone to additional chemoradiation therapy.

Yet the meaning of the hospital-level huge variability in practice observed in the Washington study remains unclear.

“Our understanding of the underutilization of invasive mediastinal staging is further complicated by the fact that patterns of invasive mediastinal staging are highly variable across hospitals staffed by at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice,” Dr. Farjah explained. “This variability could be a marker of poor-quality care. However, because the guidelines are not supported by level 1 evidence, it’s equally plausible that this variability might represent uncertainty or even disagreement with the practice guidelines – and specifically about the appropriate indication for invasive staging.”

He presented a retrospective cohort study of 406 patients whose non–small cell lung cancer was resected during July 2011–December 2013 at one of five Washington hospitals, each with at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice on staff. The four participating community hospitals and one academic medical center were involved in a National Cancer Institute–funded, physician-led quality improvement initiative.

Overall, 66% of the 406 patients underwent any form of invasive mediastinal staging: 85% by mediastinoscopy only; 12% by mediastinoscopy plus endobronchial ultrasound-guided nodal aspiration (EBUS); 3% by EBUS only; and the remaining handful by mediastinoscopy, EBUS, and esophageal ultrasound-guided nodal aspiration. The invasive staging was performed at the time of resection in 64% of cases. A median of three nodal stations were sampled.

After statistical adjustment for random variation and between-hospital differences in clinical stage, rates of invasive staging were all over the map. While an overall mean of 66% of the lung cancer patients underwent invasive mediastinal staging, the rates at the five hospitals were 94%, 84%, 31%, 80%, and 17%.

Dr. Farjah and his coinvestigators are now conducting provider interviews and focus groups in an effort to understand what drove the participating surgeons’ wide variability in performing invasive mediastinal staging.

Discussant Jane Yanagawa, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, commented, “I think this is a really interesting study because, historically, lower rates of mediastinoscopy are assumed to be a reflection of low-quality care – and you suggest that might not be the case, that it might be more complicated than that.”

Dr. Yanagawa sketched one fairly common scenario that might represent a surgeon’s reasonable avoidance of guideline-recommended invasive mediastinal staging: a patient who by all preoperative imaging appears to have stage IA lung cancer and wishes to avoid the morbidity, time, and cost of needle biopsy, instead choosing to go straight to the operating room for a diagnosis by wedge resection, followed by a completion lobectomy based upon the frozen section results. Could such a pathway account for the variability seen in the Washington study?

“I think it could have,” Dr. Farjah replied. “I would say that’s probably one driver of variability.”

As for the generalizability of the findings of a five-hospital study carried out in a single state, Dr. Farjah said he thinks the results are applicable to any academic or community hospital with at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study.

COLORADO SPRINGS – Significant variability exists between hospitals in Washington state in their rates of invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer, Farhood Farjah, MD, reported at the annual meeting of the Western Thoracic Surgical Association.

“We found evidence of a fivefold variation in hospital-level rates of invasive mediastinal staging not explained by chance or case mix,” according to Dr. Farjah of the University of Washington, Seattle.

“This has led to substantial concerns about quality of thoracic surgical care in the community at large,” he noted.

The Washington study is the first to show hospital-by-hospital variation in rates of invasive mediastinal staging.

Invasive mediastinal staging for lung cancer is considered important because imaging is known to have a substantial false-negative rate, and staging results have a profound impact on treatment recommendations, which can range from surgery alone to additional chemoradiation therapy.

Yet the meaning of the hospital-level huge variability in practice observed in the Washington study remains unclear.

“Our understanding of the underutilization of invasive mediastinal staging is further complicated by the fact that patterns of invasive mediastinal staging are highly variable across hospitals staffed by at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice,” Dr. Farjah explained. “This variability could be a marker of poor-quality care. However, because the guidelines are not supported by level 1 evidence, it’s equally plausible that this variability might represent uncertainty or even disagreement with the practice guidelines – and specifically about the appropriate indication for invasive staging.”

He presented a retrospective cohort study of 406 patients whose non–small cell lung cancer was resected during July 2011–December 2013 at one of five Washington hospitals, each with at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice on staff. The four participating community hospitals and one academic medical center were involved in a National Cancer Institute–funded, physician-led quality improvement initiative.

Overall, 66% of the 406 patients underwent any form of invasive mediastinal staging: 85% by mediastinoscopy only; 12% by mediastinoscopy plus endobronchial ultrasound-guided nodal aspiration (EBUS); 3% by EBUS only; and the remaining handful by mediastinoscopy, EBUS, and esophageal ultrasound-guided nodal aspiration. The invasive staging was performed at the time of resection in 64% of cases. A median of three nodal stations were sampled.

After statistical adjustment for random variation and between-hospital differences in clinical stage, rates of invasive staging were all over the map. While an overall mean of 66% of the lung cancer patients underwent invasive mediastinal staging, the rates at the five hospitals were 94%, 84%, 31%, 80%, and 17%.

Dr. Farjah and his coinvestigators are now conducting provider interviews and focus groups in an effort to understand what drove the participating surgeons’ wide variability in performing invasive mediastinal staging.

Discussant Jane Yanagawa, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles, commented, “I think this is a really interesting study because, historically, lower rates of mediastinoscopy are assumed to be a reflection of low-quality care – and you suggest that might not be the case, that it might be more complicated than that.”

Dr. Yanagawa sketched one fairly common scenario that might represent a surgeon’s reasonable avoidance of guideline-recommended invasive mediastinal staging: a patient who by all preoperative imaging appears to have stage IA lung cancer and wishes to avoid the morbidity, time, and cost of needle biopsy, instead choosing to go straight to the operating room for a diagnosis by wedge resection, followed by a completion lobectomy based upon the frozen section results. Could such a pathway account for the variability seen in the Washington study?

“I think it could have,” Dr. Farjah replied. “I would say that’s probably one driver of variability.”

As for the generalizability of the findings of a five-hospital study carried out in a single state, Dr. Farjah said he thinks the results are applicable to any academic or community hospital with at least one board-certified thoracic surgeon with a noncardiac practice.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding the study.

AT THE WTSA ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Rates of invasive mediastinal staging after adjustment for clinical stage ranged from a low of 17% at one hospital to as high as 94% at another.

Data source: This retrospective cohort study included 406 patients.

Disclosures: Dr. Farjah reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Short, simple antibiotic courses effective in latent TB

Latent tuberculosis infection can be safely and effectively treated with 3- and 4-month medication regimens, including those using once-weekly dosing, according to results from a new meta-analysis.

The findings, published online July 31 in Annals of Internal Medicine, bolster evidence that shorter antibiotic regimens using rifamycins alone or in combination with other drugs are a viable alternative to the longer courses (Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:248-55).

For their research, Dominik Zenner, MD, an epidemiologist with Public Health England in London, and his colleagues updated a meta-analysis they published in 2014. The team added 8 new randomized studies to the 53 that had been included in the earlier paper (Ann Intern Med. 2014 Sep;161:419-28).

Using pairwise comparisons and a Bayesian network analysis, Dr. Zenner and his colleagues found comparable efficacy among isoniazid regimens of 6 months or more; rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-only regimens, and rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens, compared with placebo (P less than .05 for all).

Importantly, a rifapentine-based regimen in which patients took a weekly dose for 12 weeks was as effective as the others.

“We think that you can get away with shorter regimens,” Dr. Zenner said in an interview. Although 3- to 4-month courses are already recommended in some countries, including the United Kingdom, for most patients with latent TB, “clinicians in some settings have been quite slow to adopt them,” he said.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend multiple treatment strategies for latent TB, depending on patient characteristics. These include 6 or 9 months of isoniazid; 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine; or 4 months of daily rifampin.

In the meta-analysis, rifamycin-only regimens performed as well as did those regimens that also used isoniazid, the study showed, suggesting that, for most patients who can safely be treated with rifamycins, “there is no added gain of using isoniazid,” Dr. Zenner said.

He noted that the longer isoniazid-alone regimens are nonetheless effective and appropriate for some, including people who might have potential drug interactions, such as HIV patients taking antiretroviral medications.

About 2 billion people worldwide are estimated to have latent TB, and most will not go on to develop active TB. However, because latent TB acts as the reservoir for active TB, screening of high-risk groups and close contacts of TB patients and treating latent infections is a public health priority.

But many of these asymptomatic patients will get lost between a positive screen result and successful treatment completion, Dr. Zenner said.

“We have huge drop-offs in the cascade of treatment, and treatment completion is one of the worries,” he said. “Whether it makes a huge difference in compliance to take only 12 doses is not sufficiently studied, but it does make a lot of sense. By reducing the pill burden, as we call it, we think that we will see quite good adherence rates – but that’s a subject of further detailed study.”

The investigators noted as a limitation of their study that hepatotoxicity outcomes were not available for all studies and that some of the included trials had a potential for bias. They did not see statistically significant differences in treatment efficacy between regimens in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, but noted in their analysis that “efficacy may have been weaker in HIV-positive populations.”

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research provided some funding for Dr. Zenner and his colleagues’ study. One coauthor, Helen Stagg, PhD, reported nonfinancial support from Sanofi during the study, and financial support from Otsuka for unrelated work.

Latent tuberculosis infection can be safely and effectively treated with 3- and 4-month medication regimens, including those using once-weekly dosing, according to results from a new meta-analysis.

The findings, published online July 31 in Annals of Internal Medicine, bolster evidence that shorter antibiotic regimens using rifamycins alone or in combination with other drugs are a viable alternative to the longer courses (Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:248-55).

For their research, Dominik Zenner, MD, an epidemiologist with Public Health England in London, and his colleagues updated a meta-analysis they published in 2014. The team added 8 new randomized studies to the 53 that had been included in the earlier paper (Ann Intern Med. 2014 Sep;161:419-28).

Using pairwise comparisons and a Bayesian network analysis, Dr. Zenner and his colleagues found comparable efficacy among isoniazid regimens of 6 months or more; rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-only regimens, and rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens, compared with placebo (P less than .05 for all).

Importantly, a rifapentine-based regimen in which patients took a weekly dose for 12 weeks was as effective as the others.

“We think that you can get away with shorter regimens,” Dr. Zenner said in an interview. Although 3- to 4-month courses are already recommended in some countries, including the United Kingdom, for most patients with latent TB, “clinicians in some settings have been quite slow to adopt them,” he said.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend multiple treatment strategies for latent TB, depending on patient characteristics. These include 6 or 9 months of isoniazid; 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine; or 4 months of daily rifampin.

In the meta-analysis, rifamycin-only regimens performed as well as did those regimens that also used isoniazid, the study showed, suggesting that, for most patients who can safely be treated with rifamycins, “there is no added gain of using isoniazid,” Dr. Zenner said.

He noted that the longer isoniazid-alone regimens are nonetheless effective and appropriate for some, including people who might have potential drug interactions, such as HIV patients taking antiretroviral medications.

About 2 billion people worldwide are estimated to have latent TB, and most will not go on to develop active TB. However, because latent TB acts as the reservoir for active TB, screening of high-risk groups and close contacts of TB patients and treating latent infections is a public health priority.

But many of these asymptomatic patients will get lost between a positive screen result and successful treatment completion, Dr. Zenner said.

“We have huge drop-offs in the cascade of treatment, and treatment completion is one of the worries,” he said. “Whether it makes a huge difference in compliance to take only 12 doses is not sufficiently studied, but it does make a lot of sense. By reducing the pill burden, as we call it, we think that we will see quite good adherence rates – but that’s a subject of further detailed study.”

The investigators noted as a limitation of their study that hepatotoxicity outcomes were not available for all studies and that some of the included trials had a potential for bias. They did not see statistically significant differences in treatment efficacy between regimens in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, but noted in their analysis that “efficacy may have been weaker in HIV-positive populations.”

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research provided some funding for Dr. Zenner and his colleagues’ study. One coauthor, Helen Stagg, PhD, reported nonfinancial support from Sanofi during the study, and financial support from Otsuka for unrelated work.

Latent tuberculosis infection can be safely and effectively treated with 3- and 4-month medication regimens, including those using once-weekly dosing, according to results from a new meta-analysis.

The findings, published online July 31 in Annals of Internal Medicine, bolster evidence that shorter antibiotic regimens using rifamycins alone or in combination with other drugs are a viable alternative to the longer courses (Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:248-55).

For their research, Dominik Zenner, MD, an epidemiologist with Public Health England in London, and his colleagues updated a meta-analysis they published in 2014. The team added 8 new randomized studies to the 53 that had been included in the earlier paper (Ann Intern Med. 2014 Sep;161:419-28).

Using pairwise comparisons and a Bayesian network analysis, Dr. Zenner and his colleagues found comparable efficacy among isoniazid regimens of 6 months or more; rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-only regimens, and rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens, compared with placebo (P less than .05 for all).

Importantly, a rifapentine-based regimen in which patients took a weekly dose for 12 weeks was as effective as the others.

“We think that you can get away with shorter regimens,” Dr. Zenner said in an interview. Although 3- to 4-month courses are already recommended in some countries, including the United Kingdom, for most patients with latent TB, “clinicians in some settings have been quite slow to adopt them,” he said.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently recommend multiple treatment strategies for latent TB, depending on patient characteristics. These include 6 or 9 months of isoniazid; 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine; or 4 months of daily rifampin.

In the meta-analysis, rifamycin-only regimens performed as well as did those regimens that also used isoniazid, the study showed, suggesting that, for most patients who can safely be treated with rifamycins, “there is no added gain of using isoniazid,” Dr. Zenner said.

He noted that the longer isoniazid-alone regimens are nonetheless effective and appropriate for some, including people who might have potential drug interactions, such as HIV patients taking antiretroviral medications.

About 2 billion people worldwide are estimated to have latent TB, and most will not go on to develop active TB. However, because latent TB acts as the reservoir for active TB, screening of high-risk groups and close contacts of TB patients and treating latent infections is a public health priority.

But many of these asymptomatic patients will get lost between a positive screen result and successful treatment completion, Dr. Zenner said.

“We have huge drop-offs in the cascade of treatment, and treatment completion is one of the worries,” he said. “Whether it makes a huge difference in compliance to take only 12 doses is not sufficiently studied, but it does make a lot of sense. By reducing the pill burden, as we call it, we think that we will see quite good adherence rates – but that’s a subject of further detailed study.”

The investigators noted as a limitation of their study that hepatotoxicity outcomes were not available for all studies and that some of the included trials had a potential for bias. They did not see statistically significant differences in treatment efficacy between regimens in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients, but noted in their analysis that “efficacy may have been weaker in HIV-positive populations.”

The U.K. National Institute for Health Research provided some funding for Dr. Zenner and his colleagues’ study. One coauthor, Helen Stagg, PhD, reported nonfinancial support from Sanofi during the study, and financial support from Otsuka for unrelated work.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point: Rifamycin-only treatment of latent TB works as well as combination regimens, and shorter dosing schedules show no loss in efficacy vs. longer ones.

Major finding: Rifamycin-only regimens, rifampicin-isoniazid regimens of 3 or 4 months, rifampicin-pyrazinamide regimens were all effective, compared with placebo and with isoniazid regimens of 6, 12 and 72 months.

Data source: A network meta-analysis of 61 randomized trials, 8 of them published in last 3 years

Disclosures: The National Institute for Health Research (UK) funded some co-authors; one co-author disclosed a financial relationship with a pharmaceutical firm.

VIDEO: Less follow-up proposed for low-risk thyroid cancer

BOSTON – , Bryan R. Haugen, MD, suggested in a keynote lecture during the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

Traditionally, thyroid cancer specialists have monitored these patients for persistent or recurrent disease as often as every 6 or 12 months. “But what we’ve realized with recent assessments of response to treatment is that some patients do well without a recurrence over many years; so, the concept of doing less monitoring and less imaging, especially in patients with an excellent response [to their initial treatment], is being studied,” Dr. Haugen said in a video interview following his talk.

He estimated that perhaps two-thirds or as many as three-quarters of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer fall into the category of having low- or intermediate-risk disease with an excellent or good response to treatment, and hence they are potential candidates for eventually transitioning to less frequent follow-up.

During his talk, Dr. Haugen suggested that after several years with no sign of disease recurrence, lower-risk patients with an excellent treatment response may be able to stop undergoing regular monitoring, and those with a good treatment response may be able to safely have their monitoring intervals extended.

According to the most recent (2015) guidelines for differentiated thyroid cancer management from the American Thyroid Association, lower-risk patients with an excellent treatment response should have their serum thyroglobulin measured every 12-24 months and undergo an ultrasound examination every 3-5 years, while patients with a good response are targeted for serum thyroglobulin measurement annually with an ultrasound every 1-3 years (Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26[1]:1-133). Dr. Haugen chaired the expert panel that wrote these guidelines.

In another provocative suggestion, Dr. Haugen proposed that once well-responsive, lower-risk patients have remained disease free for several years, their less frequent follow-up monitoring could be continued by a primary care physician or another less specialized clinician.

At some time in the future, “a patient’s primary care physician could follow a simple tumor marker, thyroglobulin, maybe once every 5 years,” said Dr. Haugen, professor of medicine and head of the division of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes at the University of Colorado in Aurora. “At the University of Colorado, we use advanced-practice providers to do long-term follow-up” for lower-risk, treatment-responsive patients, he said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BOSTON – , Bryan R. Haugen, MD, suggested in a keynote lecture during the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

Traditionally, thyroid cancer specialists have monitored these patients for persistent or recurrent disease as often as every 6 or 12 months. “But what we’ve realized with recent assessments of response to treatment is that some patients do well without a recurrence over many years; so, the concept of doing less monitoring and less imaging, especially in patients with an excellent response [to their initial treatment], is being studied,” Dr. Haugen said in a video interview following his talk.

He estimated that perhaps two-thirds or as many as three-quarters of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer fall into the category of having low- or intermediate-risk disease with an excellent or good response to treatment, and hence they are potential candidates for eventually transitioning to less frequent follow-up.

During his talk, Dr. Haugen suggested that after several years with no sign of disease recurrence, lower-risk patients with an excellent treatment response may be able to stop undergoing regular monitoring, and those with a good treatment response may be able to safely have their monitoring intervals extended.

According to the most recent (2015) guidelines for differentiated thyroid cancer management from the American Thyroid Association, lower-risk patients with an excellent treatment response should have their serum thyroglobulin measured every 12-24 months and undergo an ultrasound examination every 3-5 years, while patients with a good response are targeted for serum thyroglobulin measurement annually with an ultrasound every 1-3 years (Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26[1]:1-133). Dr. Haugen chaired the expert panel that wrote these guidelines.

In another provocative suggestion, Dr. Haugen proposed that once well-responsive, lower-risk patients have remained disease free for several years, their less frequent follow-up monitoring could be continued by a primary care physician or another less specialized clinician.

At some time in the future, “a patient’s primary care physician could follow a simple tumor marker, thyroglobulin, maybe once every 5 years,” said Dr. Haugen, professor of medicine and head of the division of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes at the University of Colorado in Aurora. “At the University of Colorado, we use advanced-practice providers to do long-term follow-up” for lower-risk, treatment-responsive patients, he said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

BOSTON – , Bryan R. Haugen, MD, suggested in a keynote lecture during the World Congress on Thyroid Cancer.

Traditionally, thyroid cancer specialists have monitored these patients for persistent or recurrent disease as often as every 6 or 12 months. “But what we’ve realized with recent assessments of response to treatment is that some patients do well without a recurrence over many years; so, the concept of doing less monitoring and less imaging, especially in patients with an excellent response [to their initial treatment], is being studied,” Dr. Haugen said in a video interview following his talk.

He estimated that perhaps two-thirds or as many as three-quarters of patients with differentiated thyroid cancer fall into the category of having low- or intermediate-risk disease with an excellent or good response to treatment, and hence they are potential candidates for eventually transitioning to less frequent follow-up.

During his talk, Dr. Haugen suggested that after several years with no sign of disease recurrence, lower-risk patients with an excellent treatment response may be able to stop undergoing regular monitoring, and those with a good treatment response may be able to safely have their monitoring intervals extended.

According to the most recent (2015) guidelines for differentiated thyroid cancer management from the American Thyroid Association, lower-risk patients with an excellent treatment response should have their serum thyroglobulin measured every 12-24 months and undergo an ultrasound examination every 3-5 years, while patients with a good response are targeted for serum thyroglobulin measurement annually with an ultrasound every 1-3 years (Thyroid. 2016 Jan;26[1]:1-133). Dr. Haugen chaired the expert panel that wrote these guidelines.

In another provocative suggestion, Dr. Haugen proposed that once well-responsive, lower-risk patients have remained disease free for several years, their less frequent follow-up monitoring could be continued by a primary care physician or another less specialized clinician.

At some time in the future, “a patient’s primary care physician could follow a simple tumor marker, thyroglobulin, maybe once every 5 years,” said Dr. Haugen, professor of medicine and head of the division of endocrinology, metabolism, and diabetes at the University of Colorado in Aurora. “At the University of Colorado, we use advanced-practice providers to do long-term follow-up” for lower-risk, treatment-responsive patients, he said.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT WCTC 2017

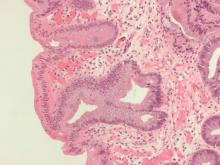

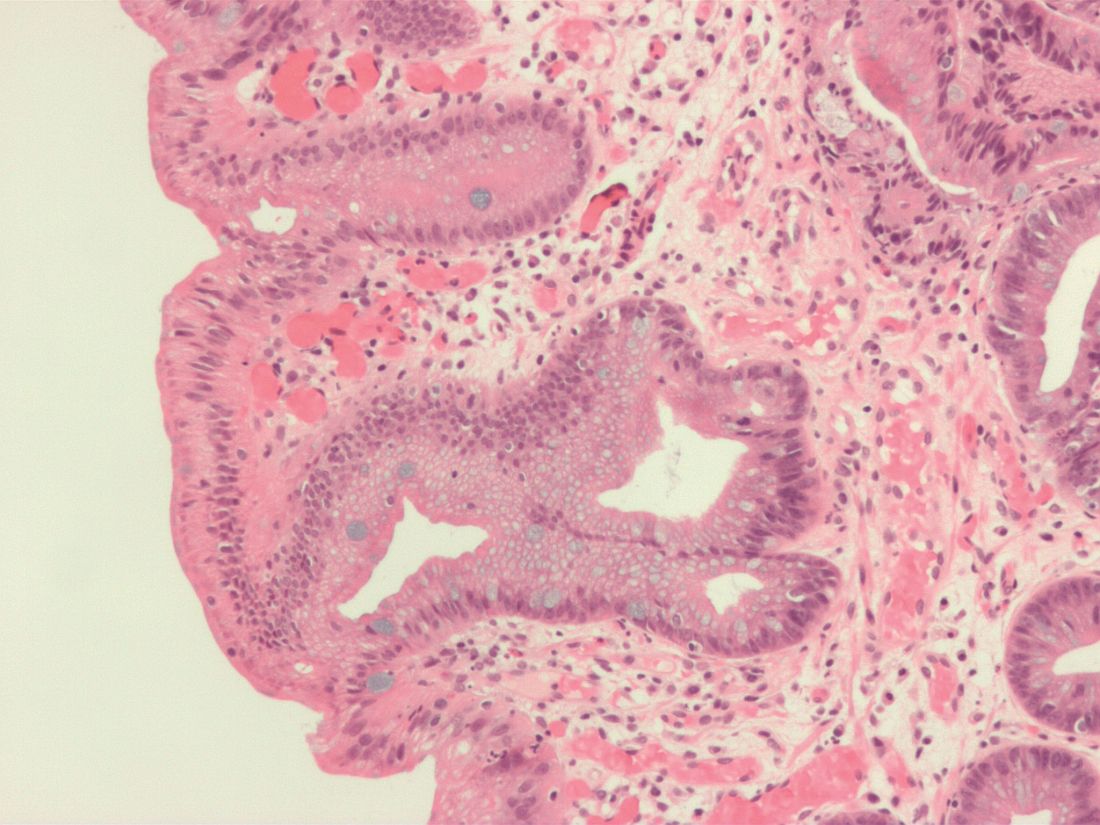

New cryoballoon treatment eradicated esophageal squamous cell neoplasias

For the first time, endoscopists have used focal cryoballoon ablation to eradicate early esophageal squamous cell neoplasias, including high-grade lesions in treatment-experienced patients.