User login

CDC reports Salmonella outbreak

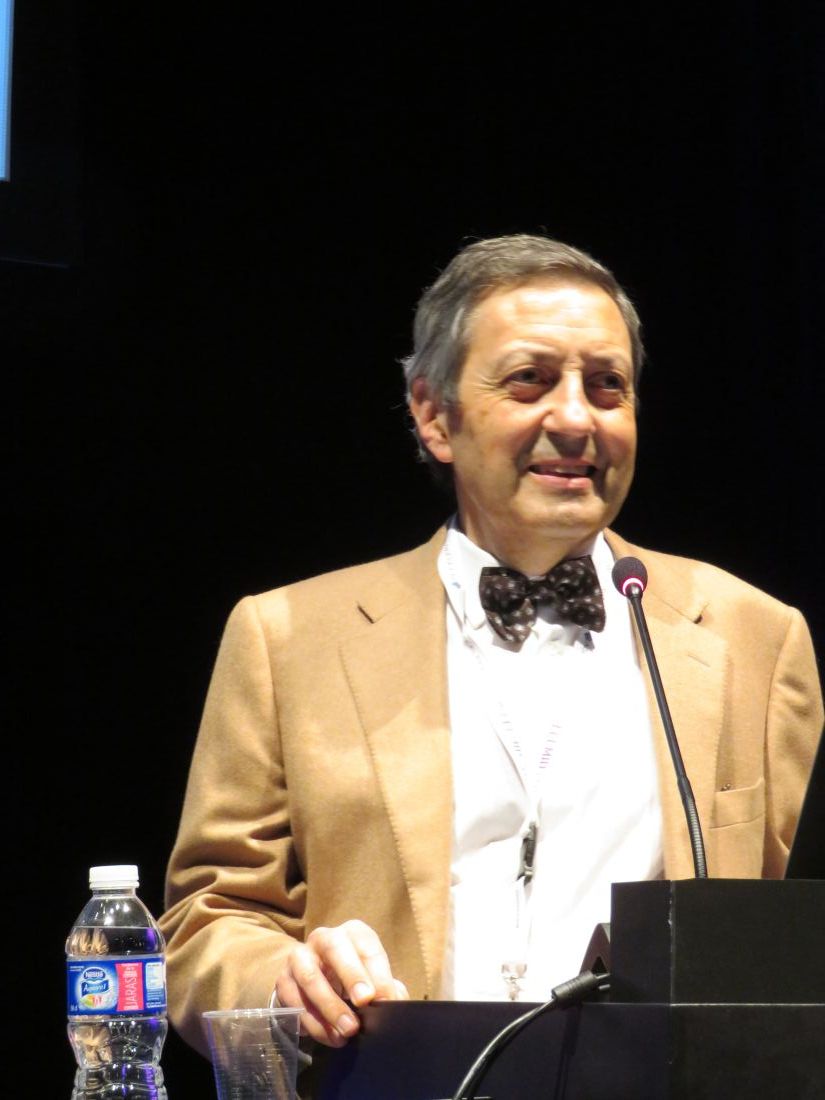

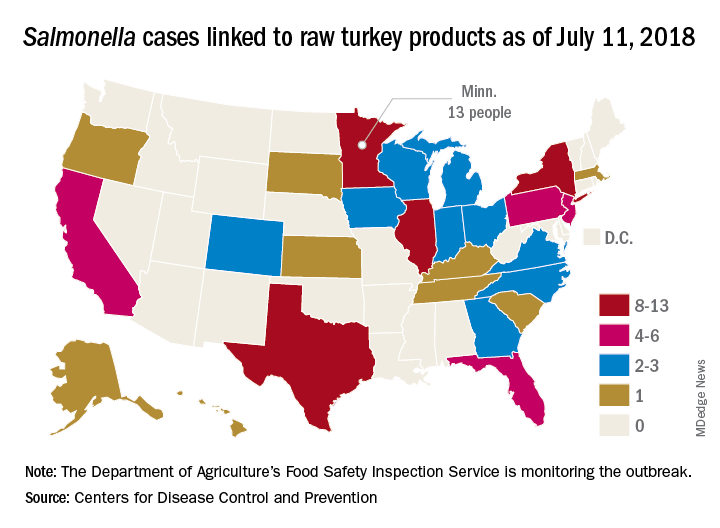

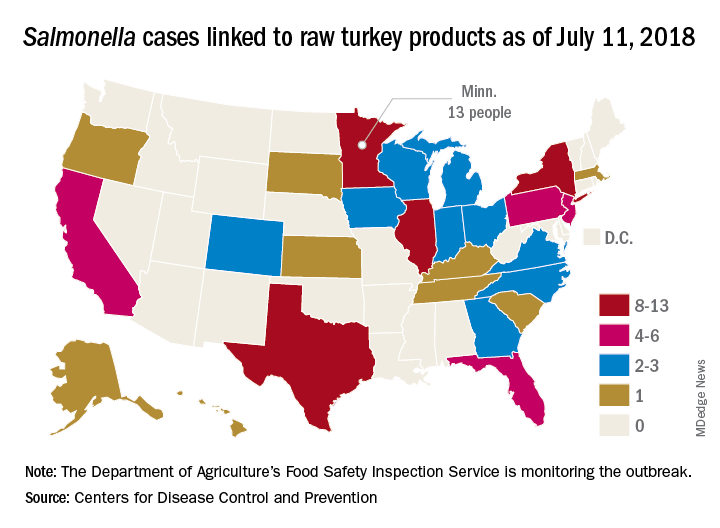

A total of 90 people in 26 states have been infected with multidrug-resistant Salmonella in an outbreak linked to raw turkey products, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of July 11, 2018, 40 of the 78 people with available information who were infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella Reading have been hospitalized, but no deaths have been reported. Of the 61 ill people who have been interviewed, most have reported preparing or eating turkey products from a number of sources, although two lived in households where raw turkey was given to pets: No common supplier has been identified, the CDC reported in an investigation notice posted July 19.

The first illness in this outbreak started on Nov. 20, 2017, and the most recent one started on June 29, 2018. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service is monitoring the outbreak, and public health and regulatory agency efforts are being coordinated by the CDC through its PulseNet national subtyping network. DNA fingerprinting “performed on Salmonella from ill people in this outbreak showed that they are closely related genetically. This means that the ill people are more likely to share a common source of infection,” the CDC said.

Consumers should handle raw turkey carefully and cook it thoroughly to prevent Salmonella, the CDC advised. Raw food of any type should not be given to pets. At this time, the CDC said that it is “not advising that consumers avoid eating properly cooked turkey products, or that retailers stop selling raw turkey products.”

A total of 90 people in 26 states have been infected with multidrug-resistant Salmonella in an outbreak linked to raw turkey products, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of July 11, 2018, 40 of the 78 people with available information who were infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella Reading have been hospitalized, but no deaths have been reported. Of the 61 ill people who have been interviewed, most have reported preparing or eating turkey products from a number of sources, although two lived in households where raw turkey was given to pets: No common supplier has been identified, the CDC reported in an investigation notice posted July 19.

The first illness in this outbreak started on Nov. 20, 2017, and the most recent one started on June 29, 2018. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service is monitoring the outbreak, and public health and regulatory agency efforts are being coordinated by the CDC through its PulseNet national subtyping network. DNA fingerprinting “performed on Salmonella from ill people in this outbreak showed that they are closely related genetically. This means that the ill people are more likely to share a common source of infection,” the CDC said.

Consumers should handle raw turkey carefully and cook it thoroughly to prevent Salmonella, the CDC advised. Raw food of any type should not be given to pets. At this time, the CDC said that it is “not advising that consumers avoid eating properly cooked turkey products, or that retailers stop selling raw turkey products.”

A total of 90 people in 26 states have been infected with multidrug-resistant Salmonella in an outbreak linked to raw turkey products, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

As of July 11, 2018, 40 of the 78 people with available information who were infected with the outbreak strain of Salmonella Reading have been hospitalized, but no deaths have been reported. Of the 61 ill people who have been interviewed, most have reported preparing or eating turkey products from a number of sources, although two lived in households where raw turkey was given to pets: No common supplier has been identified, the CDC reported in an investigation notice posted July 19.

The first illness in this outbreak started on Nov. 20, 2017, and the most recent one started on June 29, 2018. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Safety Inspection Service is monitoring the outbreak, and public health and regulatory agency efforts are being coordinated by the CDC through its PulseNet national subtyping network. DNA fingerprinting “performed on Salmonella from ill people in this outbreak showed that they are closely related genetically. This means that the ill people are more likely to share a common source of infection,” the CDC said.

Consumers should handle raw turkey carefully and cook it thoroughly to prevent Salmonella, the CDC advised. Raw food of any type should not be given to pets. At this time, the CDC said that it is “not advising that consumers avoid eating properly cooked turkey products, or that retailers stop selling raw turkey products.”

Urgent care and retail clinics fuel inappropriate antibiotic prescribing

When it comes to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, urgent care centers and retail clinics may have an outsized impact, a review of commercial insurance claims suggests.

Antibiotic prescription rates were at least twice as high in those settings, compared with emergency departments and medical office visits, according to the retrospective analysis.

The issue may be particularly pronounced in urgent care centers, based on this study, in which nearly half of visits for antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses resulted in antibiotic prescribing.

Those findings suggest a need for “antibiotic stewardship interventions” to reduce unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics in ambulatory care settings, authors of the analysis reported in a research letter to JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Efforts targeting urgent care centers are urgently needed,” wrote Danielle L. Palms, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her coauthors.

The retrospective study by Ms. Palms and her colleagues included claims from 2014 in a database of individuals 65 years of age or younger with employer-sponsored insurance.

The researchers included encounters in which medical and prescription coverage data were captured, including approximately 2.7 million urgent care center visits, 58,000 retail clinic visits, 4.8 million emergency department visits, and 148.5 million medical office visits.[[{"fid":"194045","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"filtered_html","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"Sheep purple/flickr/CC BY 2.0 /en.wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"filtered_html","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"Sheep purple/flickr/CC BY 2.0 /en.wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0"}}}]]

They found antibiotic prescriptions linked to 39.0% of urgent care and 36.4% of retail clinic visits, compared with 13.8% of emergency department visits and 7.1% of medical office visits.

For respiratory diagnoses where antibiotics would be inappropriate, such as viral upper respiratory infections, antibiotics were nevertheless prescribed in 45.7% of urgent care visits, compared with 24.6% of emergency department, 17.0% of medical office visits, and 14.4% of retail clinic visits.

Those data show “substantial variability” that suggests case mix differences and evidence of antibiotic overuse, particularly in the urgent care setting, the researchers said in their letter.

In another recent study, looking at the 2010-2011 period, at least 30% of antibiotic prescriptions written in U.S. physician offices and emergency departments were unnecessary.

“The finding of the present study that antibiotic prescribing for antibiotic inappropriate respiratory diagnoses was highest in urgent care centers suggests that unnecessary antibiotic prescribing nationally in all outpatient settings may be higher than the estimated 30%,” wrote Ms. Palms and her coinvestigators.

The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ms. Palms and her coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Palms DL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jul 16.

This study suggests urgent care and retail clinics are “underrecognized” contributors to the ongoing problem of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, according to authors of an invited commentary.

The urgent care sector, a $15 billion business representing more than 10,000 U.S. high-volume clinics, is growing very rapidly due to convenient locations, same-day access to care, and lower out-of-pocket expenditures versus emergency departments, the authors said.

“Lowering barriers for an office visit to such a degree may prompt frequent visits for mild self-resolving illnesses that would be better treated with rest and symptom management at home,” they wrote.

Innovations such as telephone triage lines could help reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, but might “conflict with the business model” of urgent care and retail clinics, they added.

“Unfortunately, we all pay – in increased insurance premiums and increased antibiotic resistance – from the overprescribing of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections,” they wrote.

Michael A. Incze, MD, MSEd, and Rita F. Redberg, MD, MSc, are with the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco. Mitchell H. Katz, MD, is with New York City Health and Hospitals. These comments are based on their invited commentary appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine . All three authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

This study suggests urgent care and retail clinics are “underrecognized” contributors to the ongoing problem of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, according to authors of an invited commentary.

The urgent care sector, a $15 billion business representing more than 10,000 U.S. high-volume clinics, is growing very rapidly due to convenient locations, same-day access to care, and lower out-of-pocket expenditures versus emergency departments, the authors said.

“Lowering barriers for an office visit to such a degree may prompt frequent visits for mild self-resolving illnesses that would be better treated with rest and symptom management at home,” they wrote.

Innovations such as telephone triage lines could help reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, but might “conflict with the business model” of urgent care and retail clinics, they added.

“Unfortunately, we all pay – in increased insurance premiums and increased antibiotic resistance – from the overprescribing of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections,” they wrote.

Michael A. Incze, MD, MSEd, and Rita F. Redberg, MD, MSc, are with the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco. Mitchell H. Katz, MD, is with New York City Health and Hospitals. These comments are based on their invited commentary appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine . All three authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

This study suggests urgent care and retail clinics are “underrecognized” contributors to the ongoing problem of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, according to authors of an invited commentary.

The urgent care sector, a $15 billion business representing more than 10,000 U.S. high-volume clinics, is growing very rapidly due to convenient locations, same-day access to care, and lower out-of-pocket expenditures versus emergency departments, the authors said.

“Lowering barriers for an office visit to such a degree may prompt frequent visits for mild self-resolving illnesses that would be better treated with rest and symptom management at home,” they wrote.

Innovations such as telephone triage lines could help reduce inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, but might “conflict with the business model” of urgent care and retail clinics, they added.

“Unfortunately, we all pay – in increased insurance premiums and increased antibiotic resistance – from the overprescribing of antibiotics for upper respiratory tract infections,” they wrote.

Michael A. Incze, MD, MSEd, and Rita F. Redberg, MD, MSc, are with the department of medicine, University of California, San Francisco. Mitchell H. Katz, MD, is with New York City Health and Hospitals. These comments are based on their invited commentary appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine . All three authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

When it comes to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, urgent care centers and retail clinics may have an outsized impact, a review of commercial insurance claims suggests.

Antibiotic prescription rates were at least twice as high in those settings, compared with emergency departments and medical office visits, according to the retrospective analysis.

The issue may be particularly pronounced in urgent care centers, based on this study, in which nearly half of visits for antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses resulted in antibiotic prescribing.

Those findings suggest a need for “antibiotic stewardship interventions” to reduce unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics in ambulatory care settings, authors of the analysis reported in a research letter to JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Efforts targeting urgent care centers are urgently needed,” wrote Danielle L. Palms, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her coauthors.

The retrospective study by Ms. Palms and her colleagues included claims from 2014 in a database of individuals 65 years of age or younger with employer-sponsored insurance.

The researchers included encounters in which medical and prescription coverage data were captured, including approximately 2.7 million urgent care center visits, 58,000 retail clinic visits, 4.8 million emergency department visits, and 148.5 million medical office visits.[[{"fid":"194045","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"filtered_html","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"Sheep purple/flickr/CC BY 2.0 /en.wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"filtered_html","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"Sheep purple/flickr/CC BY 2.0 /en.wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0"}}}]]

They found antibiotic prescriptions linked to 39.0% of urgent care and 36.4% of retail clinic visits, compared with 13.8% of emergency department visits and 7.1% of medical office visits.

For respiratory diagnoses where antibiotics would be inappropriate, such as viral upper respiratory infections, antibiotics were nevertheless prescribed in 45.7% of urgent care visits, compared with 24.6% of emergency department, 17.0% of medical office visits, and 14.4% of retail clinic visits.

Those data show “substantial variability” that suggests case mix differences and evidence of antibiotic overuse, particularly in the urgent care setting, the researchers said in their letter.

In another recent study, looking at the 2010-2011 period, at least 30% of antibiotic prescriptions written in U.S. physician offices and emergency departments were unnecessary.

“The finding of the present study that antibiotic prescribing for antibiotic inappropriate respiratory diagnoses was highest in urgent care centers suggests that unnecessary antibiotic prescribing nationally in all outpatient settings may be higher than the estimated 30%,” wrote Ms. Palms and her coinvestigators.

The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ms. Palms and her coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Palms DL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jul 16.

When it comes to inappropriate antibiotic prescribing, urgent care centers and retail clinics may have an outsized impact, a review of commercial insurance claims suggests.

Antibiotic prescription rates were at least twice as high in those settings, compared with emergency departments and medical office visits, according to the retrospective analysis.

The issue may be particularly pronounced in urgent care centers, based on this study, in which nearly half of visits for antibiotic-inappropriate respiratory diagnoses resulted in antibiotic prescribing.

Those findings suggest a need for “antibiotic stewardship interventions” to reduce unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics in ambulatory care settings, authors of the analysis reported in a research letter to JAMA Internal Medicine.

“Efforts targeting urgent care centers are urgently needed,” wrote Danielle L. Palms, MPH, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her coauthors.

The retrospective study by Ms. Palms and her colleagues included claims from 2014 in a database of individuals 65 years of age or younger with employer-sponsored insurance.

The researchers included encounters in which medical and prescription coverage data were captured, including approximately 2.7 million urgent care center visits, 58,000 retail clinic visits, 4.8 million emergency department visits, and 148.5 million medical office visits.[[{"fid":"194045","view_mode":"medstat_image_flush_right","attributes":{"class":"media-element file-medstat-image-flush-right","data-delta":"1"},"fields":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"filtered_html","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"Sheep purple/flickr/CC BY 2.0 /en.wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"medstat_image_flush_right","field_file_image_caption[und][0][value]":"","field_file_image_caption[und][0][format]":"filtered_html","field_file_image_credit[und][0][value]":"Sheep purple/flickr/CC BY 2.0 /en.wikipedia/CC BY-SA 4.0"}}}]]

They found antibiotic prescriptions linked to 39.0% of urgent care and 36.4% of retail clinic visits, compared with 13.8% of emergency department visits and 7.1% of medical office visits.

For respiratory diagnoses where antibiotics would be inappropriate, such as viral upper respiratory infections, antibiotics were nevertheless prescribed in 45.7% of urgent care visits, compared with 24.6% of emergency department, 17.0% of medical office visits, and 14.4% of retail clinic visits.

Those data show “substantial variability” that suggests case mix differences and evidence of antibiotic overuse, particularly in the urgent care setting, the researchers said in their letter.

In another recent study, looking at the 2010-2011 period, at least 30% of antibiotic prescriptions written in U.S. physician offices and emergency departments were unnecessary.

“The finding of the present study that antibiotic prescribing for antibiotic inappropriate respiratory diagnoses was highest in urgent care centers suggests that unnecessary antibiotic prescribing nationally in all outpatient settings may be higher than the estimated 30%,” wrote Ms. Palms and her coinvestigators.

The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ms. Palms and her coauthors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Palms DL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jul 16.

FROM JAMA INTERNAL MEDICINE

Key clinical point:

Major finding: For respiratory diagnoses where antibiotics would be inappropriate, such as viral upper respiratory infections, antibiotics were nevertheless prescribed in 45.7% of urgent care visits.

Study details: A retrospective cohort study including claims from 2014 in a database for individuals 65 years of age or younger with employer-sponsored insurance.

Disclosures: The research was funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

Source: Palms DL et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2018 Jul 16.

Primary cirrhotic prophylaxis of bacterial peritonitis falls short

WASHINGTON –

The mortality rate during follow-up of cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on primary prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was 19%, compared with a 9% death rate among cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on secondary prophylaxis, Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Although the findings raised questions about the value of primary prophylaxis with an antibiotic in cirrhotic patients for preventing a first episode of SBP, secondary prophylaxis remains an important precaution.

“There is clear benefit from secondary prophylaxis; please use it. The data supporting it are robust,” said Dr. Bajaj, a hepatologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. In contrast, the evidence supporting benefits from primary prophylaxis is weaker, he said. The findings were also counterintuitive, because patients who experience repeat episodes of SBP might be expected to fare worse than those hit by SBP just once.

Dr. Bajaj also acknowledged the substantial confounding that distinguishes patients with cirrhosis receiving primary or secondary prophylaxis, and the difficulty of fully adjusting for all this confounding by statistical analyses. “There is selective bias for secondary prevention, and there is no way to correct for this,” he explained. Patients who need secondary prophylaxis have “weathered the storm” of a first episode of SBP, which might have exerted selection pressure, and might have triggered important immunologic changes, Dr. Bajaj suggested.

The findings also raised concerns about the appropriateness of existing antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP. The patients included in the study all received similar regimens regardless of whether they were on primary or secondary prophylaxis. Three-quarters of primary prophylaxis patients received a fluoroquinolone, as did 81% on secondary prophylaxis. All other patients received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. These regimens are aimed at preventing gram-negative infections; however, an increasing number of SBP episodes are caused by either gram-positive pathogens or strains of gram-negative bacteria or fungi resistant to standard antibiotics.

Clinicians “absolutely” need to rethink their approach to both primary and secondary prophylaxis, Dr. Bajaj said. “As fast as treatment evolves, bacteria evolve 20 times faster. We need to find ways to prevent infections without antibiotic prophylaxis, whatever that might be.”

The study used data collected prospectively from patients with cirrhosis at any of 12 U.S. and 2 Canadian centers that belonged to the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease. Among 2,731 cirrhotic patients admitted nonelectively, 492 (18%) were on antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of their admission, 305 for primary prophylaxis and 187 for secondary prophylaxis. Dr. Bajaj and his associates used both the baseline model for end-stage liver disease score and serum albumin level of each patient to focus on a group of 154 primary prophylaxis and 154 secondary prophylaxis patients who were similar by these two criteria. Despite this matching, the two subgroups showed statistically significant differences at the time of their index hospitalization for several important clinical measures.

The secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized within the previous 6 months, significantly more likely to be on treatment for hepatic encephalopathy at the time of their index admission, and significantly less likely to have systemic inflammatory response syndrome on admission.

Also, at the time of admission, secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have an infection of any type at a rate of 40%, compared with 24% among those on primary prophylaxis, as well as a significantly higher rate of SBP at 16%, compared with a 9% rate among the primary prophylaxis patients. During hospitalization, nosocomial SBP occurred significantly more often among the secondary prophylaxis patients at a rate of 6%, compared with a 0.5% rate among those on primary prophylaxis.

Despite these between-group differences, the average duration of hospitalization, and the average incidence of acute-on-chronic liver failure during follow-up out to 30 days post discharge was similar in the two subgroups. And the patients on secondary prophylaxis showed better outcomes by two important parameters: mortality during hospitalization and 30 days post discharge; and the incidence of ICU admission during hospitalization, which was significantly greater for primary prophylaxis patients at 31%, compared with 21% among the secondary prophylaxis patients, Dr. Bajaj reported.

Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

WASHINGTON –

The mortality rate during follow-up of cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on primary prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was 19%, compared with a 9% death rate among cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on secondary prophylaxis, Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Although the findings raised questions about the value of primary prophylaxis with an antibiotic in cirrhotic patients for preventing a first episode of SBP, secondary prophylaxis remains an important precaution.

“There is clear benefit from secondary prophylaxis; please use it. The data supporting it are robust,” said Dr. Bajaj, a hepatologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. In contrast, the evidence supporting benefits from primary prophylaxis is weaker, he said. The findings were also counterintuitive, because patients who experience repeat episodes of SBP might be expected to fare worse than those hit by SBP just once.

Dr. Bajaj also acknowledged the substantial confounding that distinguishes patients with cirrhosis receiving primary or secondary prophylaxis, and the difficulty of fully adjusting for all this confounding by statistical analyses. “There is selective bias for secondary prevention, and there is no way to correct for this,” he explained. Patients who need secondary prophylaxis have “weathered the storm” of a first episode of SBP, which might have exerted selection pressure, and might have triggered important immunologic changes, Dr. Bajaj suggested.

The findings also raised concerns about the appropriateness of existing antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP. The patients included in the study all received similar regimens regardless of whether they were on primary or secondary prophylaxis. Three-quarters of primary prophylaxis patients received a fluoroquinolone, as did 81% on secondary prophylaxis. All other patients received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. These regimens are aimed at preventing gram-negative infections; however, an increasing number of SBP episodes are caused by either gram-positive pathogens or strains of gram-negative bacteria or fungi resistant to standard antibiotics.

Clinicians “absolutely” need to rethink their approach to both primary and secondary prophylaxis, Dr. Bajaj said. “As fast as treatment evolves, bacteria evolve 20 times faster. We need to find ways to prevent infections without antibiotic prophylaxis, whatever that might be.”

The study used data collected prospectively from patients with cirrhosis at any of 12 U.S. and 2 Canadian centers that belonged to the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease. Among 2,731 cirrhotic patients admitted nonelectively, 492 (18%) were on antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of their admission, 305 for primary prophylaxis and 187 for secondary prophylaxis. Dr. Bajaj and his associates used both the baseline model for end-stage liver disease score and serum albumin level of each patient to focus on a group of 154 primary prophylaxis and 154 secondary prophylaxis patients who were similar by these two criteria. Despite this matching, the two subgroups showed statistically significant differences at the time of their index hospitalization for several important clinical measures.

The secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized within the previous 6 months, significantly more likely to be on treatment for hepatic encephalopathy at the time of their index admission, and significantly less likely to have systemic inflammatory response syndrome on admission.

Also, at the time of admission, secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have an infection of any type at a rate of 40%, compared with 24% among those on primary prophylaxis, as well as a significantly higher rate of SBP at 16%, compared with a 9% rate among the primary prophylaxis patients. During hospitalization, nosocomial SBP occurred significantly more often among the secondary prophylaxis patients at a rate of 6%, compared with a 0.5% rate among those on primary prophylaxis.

Despite these between-group differences, the average duration of hospitalization, and the average incidence of acute-on-chronic liver failure during follow-up out to 30 days post discharge was similar in the two subgroups. And the patients on secondary prophylaxis showed better outcomes by two important parameters: mortality during hospitalization and 30 days post discharge; and the incidence of ICU admission during hospitalization, which was significantly greater for primary prophylaxis patients at 31%, compared with 21% among the secondary prophylaxis patients, Dr. Bajaj reported.

Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

WASHINGTON –

The mortality rate during follow-up of cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on primary prophylaxis against spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) was 19%, compared with a 9% death rate among cirrhotic patients hospitalized while on secondary prophylaxis, Jasmohan S. Bajaj, MD, said at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Although the findings raised questions about the value of primary prophylaxis with an antibiotic in cirrhotic patients for preventing a first episode of SBP, secondary prophylaxis remains an important precaution.

“There is clear benefit from secondary prophylaxis; please use it. The data supporting it are robust,” said Dr. Bajaj, a hepatologist at Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond. In contrast, the evidence supporting benefits from primary prophylaxis is weaker, he said. The findings were also counterintuitive, because patients who experience repeat episodes of SBP might be expected to fare worse than those hit by SBP just once.

Dr. Bajaj also acknowledged the substantial confounding that distinguishes patients with cirrhosis receiving primary or secondary prophylaxis, and the difficulty of fully adjusting for all this confounding by statistical analyses. “There is selective bias for secondary prevention, and there is no way to correct for this,” he explained. Patients who need secondary prophylaxis have “weathered the storm” of a first episode of SBP, which might have exerted selection pressure, and might have triggered important immunologic changes, Dr. Bajaj suggested.

The findings also raised concerns about the appropriateness of existing antibiotic prophylaxis for SBP. The patients included in the study all received similar regimens regardless of whether they were on primary or secondary prophylaxis. Three-quarters of primary prophylaxis patients received a fluoroquinolone, as did 81% on secondary prophylaxis. All other patients received trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. These regimens are aimed at preventing gram-negative infections; however, an increasing number of SBP episodes are caused by either gram-positive pathogens or strains of gram-negative bacteria or fungi resistant to standard antibiotics.

Clinicians “absolutely” need to rethink their approach to both primary and secondary prophylaxis, Dr. Bajaj said. “As fast as treatment evolves, bacteria evolve 20 times faster. We need to find ways to prevent infections without antibiotic prophylaxis, whatever that might be.”

The study used data collected prospectively from patients with cirrhosis at any of 12 U.S. and 2 Canadian centers that belonged to the North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease. Among 2,731 cirrhotic patients admitted nonelectively, 492 (18%) were on antibiotic prophylaxis at the time of their admission, 305 for primary prophylaxis and 187 for secondary prophylaxis. Dr. Bajaj and his associates used both the baseline model for end-stage liver disease score and serum albumin level of each patient to focus on a group of 154 primary prophylaxis and 154 secondary prophylaxis patients who were similar by these two criteria. Despite this matching, the two subgroups showed statistically significant differences at the time of their index hospitalization for several important clinical measures.

The secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have been hospitalized within the previous 6 months, significantly more likely to be on treatment for hepatic encephalopathy at the time of their index admission, and significantly less likely to have systemic inflammatory response syndrome on admission.

Also, at the time of admission, secondary prophylaxis patients were significantly more likely to have an infection of any type at a rate of 40%, compared with 24% among those on primary prophylaxis, as well as a significantly higher rate of SBP at 16%, compared with a 9% rate among the primary prophylaxis patients. During hospitalization, nosocomial SBP occurred significantly more often among the secondary prophylaxis patients at a rate of 6%, compared with a 0.5% rate among those on primary prophylaxis.

Despite these between-group differences, the average duration of hospitalization, and the average incidence of acute-on-chronic liver failure during follow-up out to 30 days post discharge was similar in the two subgroups. And the patients on secondary prophylaxis showed better outcomes by two important parameters: mortality during hospitalization and 30 days post discharge; and the incidence of ICU admission during hospitalization, which was significantly greater for primary prophylaxis patients at 31%, compared with 21% among the secondary prophylaxis patients, Dr. Bajaj reported.

Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

REPORTING FROM DDW 2018

Key clinical point: Antibiotic prophylaxis for bacterial peritonitis showed limitations, especially for primary prophylaxis.

Major finding: Mortality was 19% among primary prophylaxis patients and 9% among secondary prophylaxis patients during hospitalization and 30 days following.

Study details: An analysis of data from 308 cirrhotic patients on antibiotic prophylaxis at 14 North American centers.

Disclosures: Dr. Bajaj has been a consultant for Norgine and Salix Pharmaceuticals and has received research support from Grifols and Salix Pharmaceuticals.

CDC concerned about multidrug-resistant Shigella

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention have issued follow-up recommendations for managing and reporting Shigella infections because of concerns about increasing antibiotic resistance and the possibility of treatment failures.

Isolates with no resistance to quinolone antibiotics have ciprofloxacin minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of less than 0.015 mcg/mL. However, the CDC has continued to identify isolates of Shigella that, while still within the susceptible range for the fluoroquinolone antibiotic ciprofloxacin (that is, having MIC values less than 1 mcg/mL), have MIC values for ciprofloxacin of 0.12-1.0 mcg/mL, thus appearing to harbor one or more resistance mechanisms. Furthermore, the CDC has identified an increasing number of isolates that have MIC values for azithromycin exceeding the epidemiologic cutoff value, which suggests some form of acquired resistance.

“CDC is particularly concerned about people who are at high risk for multidrug-resistant Shigella infections and are more likely to require antibiotic treatment, such as men who have sex with men, patients who are homeless, and immunocompromised patients. These patients often have more severe disease, prolonged shedding, and recurrent infections,” the recommendations stated.

More information can be found in the CDC’s Health Alert Network release.

Antibiotic stewardship in sepsis

ORLANDO – When is it rational to consider de-escalating, or even stopping, antibiotics for septic patients, and how will patients’ future health be affected by antibiotic use during critical illnesses?

According to Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, locating the tipping point between optimal care for the individual patient in sepsis, and the importance of antibiotic stewardship is a balancing act. It’s a process guided by laboratory findings, by knowledge of local pathogens and patterns of antimicrobial resistance, and also by clinical judgment, she said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

By all means, begin antibiotics for patients with sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan, also medical director of infection prevention at MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, told attendees at a pre-course at HM18. “Prompt initiation of antibiotics for sepsis is critical, and appropriate use of antibiotics decreases mortality.” However, she noted, de-escalation of antibiotics also decreases mortality.

“What is antibiotic stewardship? Most of us think of this as the microbial stewardship police calling to ask you, ‘Why are you using this antibiotic?’’ she said. “It’s really the right antibiotic, for the right diagnosis, for the appropriate duration.”

Of course, Dr. Hanrahan said, any medication is associated with potential adverse events, and antibiotics are no different. “Almost one-third of antibiotics given are either unnecessary or inappropriate,” she said.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very serious public health threat, Dr. Hanrahan affirmed. “Antibiotic use is the most important modifiable factor related to development of antibiotic resistance. With regard to multidrug resistant [MDR] gram negatives, we are running out of antibiotics” to treat these organisms, she said, noting that “Many antibiotics to treat MDRs are “astronomically expensive – and that’s a really big problem.”

It’s important to remember that, when antibiotics are prescribed, “You’re affecting the microbiome not just of that patient, but of those around them,” as resistance factors are potentially spread from one individual’s microbiome to their friends, family, and other contacts, Dr. Hanrahan said.

The later risk of sepsis has also shown to be elevated for individuals who have received high-risk antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, beta-lactamase inhibitor formulations, vancomycin, and carbapenems – many of which are also used to treat sepsis. All of these antibiotics kill anaerobic bacteria, Dr. Hanrahan said, and “when you kill anaerobes you do a lot of bad things to people.”

Identifying the pathogens

There are already many frightening players in the antibiotic-resistant landscape. Among them are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, increasingly common in health care settings. Unfortunately, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), “we’ve lost the battle,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Acinetobacter is another increasing threat, she said, as is Candida auris, which has caused large outbreaks in Europe. Because it’s resistant to azole antifungals, once C. auris comes to U.S. hospitals, “You’re going to have a really big problem,” she said. Finally, multidrug resistant and extremely drug resistant Pseudomonas species are being encountered with increasing frequency.

And, of course, Clostridium difficile infections continue to ravage older populations. “One in 11 people aged 65 or older will die from C. diff infections,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

For all of these bacteria, she said, “I can’t tell you what antibiotics to use because you have to know what the organisms are in your hospital.” A good resource for tracking local resistance patterns is the information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including interactive maps showing health care–associated infections, as well as HealthMap ResistanceOpen, which maps antibiotic resistance alerts across the United States. The CDC also offers training on antibiotic stewardship; Dr. Hanrahan said the several hours she spent completing the training were well spent.

After a broad-spectrum antibiotic is initiated for sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan said that the next infectious disease–related steps should focus on identifying pathogens so antimicrobial therapy can be tailored or scaled back appropriately. In many cases, this will mean obtaining blood cultures – ideally, two sets from two separate sites. It’s no longer thought necessary to separate the blood draws by 20 minutes, or to try to time the draw during a febrile episode, she said.

What is important is to make sure that you’re not treating contamination or colonization – “Treat only clinically significant infections,” Dr. Hanrahan said. A common red herring, especially among elderly individuals coming from assisted living or in patients with indwelling urinary catheters, is a positive urine culture in the absence of signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection. Think twice about whether this truly represents a source of infection, she said. “Don’t treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.”

In order to avoid “chasing contamination,” do not obtain the blood culture samples from a venipuncture site. “Contamination is twice as likely when drawing from a venipuncture site,” Dr. Hanrahan noted. “When possible you should avoid this.”

It’s also important to remember that 10% of fever in hospitalized individuals is from a noninfectious source. “Take a careful history, and do a physical exam to help distinguish infections from other causes of fever,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

Additional investigations to consider in highly immunocompromised patients might include both mycobacterial and fungal cultures, although these studies are otherwise generally low yield. And, she said, “Don’t send catheter-tip cultures – it’s pointless, and it really doesn’t add much information.”

Good clinical judgment still goes a long way toward guiding therapy. “If a patient is stable and it’s not clear whether an antibiotic is needed, consider waiting and re-evaluating later,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Generally, duration of treatment should also be clinically based. “Stop antibiotics as soon as possible, and remove catheters as soon as possible,” Dr. Hanrahan said, adding that few infections really warrant treatment for a fixed amount of time. These include meningitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and many cases of osteomyelitis.

Similarly, when a patient who had been ill now looks well, feels well, and is stable or improving, there’s usually no need for repeat blood cultures, Dr. Hanrahan said. Still, a cautious balance is where most clinicians will wind up.

“I learned a long time ago that I have to do the things that let me go home and sleep at night,” she concluded.

Dr. Hanrahan reported having been a consultant for Gilead, Astellas, and Cempra.

ORLANDO – When is it rational to consider de-escalating, or even stopping, antibiotics for septic patients, and how will patients’ future health be affected by antibiotic use during critical illnesses?

According to Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, locating the tipping point between optimal care for the individual patient in sepsis, and the importance of antibiotic stewardship is a balancing act. It’s a process guided by laboratory findings, by knowledge of local pathogens and patterns of antimicrobial resistance, and also by clinical judgment, she said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

By all means, begin antibiotics for patients with sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan, also medical director of infection prevention at MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, told attendees at a pre-course at HM18. “Prompt initiation of antibiotics for sepsis is critical, and appropriate use of antibiotics decreases mortality.” However, she noted, de-escalation of antibiotics also decreases mortality.

“What is antibiotic stewardship? Most of us think of this as the microbial stewardship police calling to ask you, ‘Why are you using this antibiotic?’’ she said. “It’s really the right antibiotic, for the right diagnosis, for the appropriate duration.”

Of course, Dr. Hanrahan said, any medication is associated with potential adverse events, and antibiotics are no different. “Almost one-third of antibiotics given are either unnecessary or inappropriate,” she said.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very serious public health threat, Dr. Hanrahan affirmed. “Antibiotic use is the most important modifiable factor related to development of antibiotic resistance. With regard to multidrug resistant [MDR] gram negatives, we are running out of antibiotics” to treat these organisms, she said, noting that “Many antibiotics to treat MDRs are “astronomically expensive – and that’s a really big problem.”

It’s important to remember that, when antibiotics are prescribed, “You’re affecting the microbiome not just of that patient, but of those around them,” as resistance factors are potentially spread from one individual’s microbiome to their friends, family, and other contacts, Dr. Hanrahan said.

The later risk of sepsis has also shown to be elevated for individuals who have received high-risk antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, beta-lactamase inhibitor formulations, vancomycin, and carbapenems – many of which are also used to treat sepsis. All of these antibiotics kill anaerobic bacteria, Dr. Hanrahan said, and “when you kill anaerobes you do a lot of bad things to people.”

Identifying the pathogens

There are already many frightening players in the antibiotic-resistant landscape. Among them are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, increasingly common in health care settings. Unfortunately, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), “we’ve lost the battle,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Acinetobacter is another increasing threat, she said, as is Candida auris, which has caused large outbreaks in Europe. Because it’s resistant to azole antifungals, once C. auris comes to U.S. hospitals, “You’re going to have a really big problem,” she said. Finally, multidrug resistant and extremely drug resistant Pseudomonas species are being encountered with increasing frequency.

And, of course, Clostridium difficile infections continue to ravage older populations. “One in 11 people aged 65 or older will die from C. diff infections,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

For all of these bacteria, she said, “I can’t tell you what antibiotics to use because you have to know what the organisms are in your hospital.” A good resource for tracking local resistance patterns is the information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including interactive maps showing health care–associated infections, as well as HealthMap ResistanceOpen, which maps antibiotic resistance alerts across the United States. The CDC also offers training on antibiotic stewardship; Dr. Hanrahan said the several hours she spent completing the training were well spent.

After a broad-spectrum antibiotic is initiated for sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan said that the next infectious disease–related steps should focus on identifying pathogens so antimicrobial therapy can be tailored or scaled back appropriately. In many cases, this will mean obtaining blood cultures – ideally, two sets from two separate sites. It’s no longer thought necessary to separate the blood draws by 20 minutes, or to try to time the draw during a febrile episode, she said.

What is important is to make sure that you’re not treating contamination or colonization – “Treat only clinically significant infections,” Dr. Hanrahan said. A common red herring, especially among elderly individuals coming from assisted living or in patients with indwelling urinary catheters, is a positive urine culture in the absence of signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection. Think twice about whether this truly represents a source of infection, she said. “Don’t treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.”

In order to avoid “chasing contamination,” do not obtain the blood culture samples from a venipuncture site. “Contamination is twice as likely when drawing from a venipuncture site,” Dr. Hanrahan noted. “When possible you should avoid this.”

It’s also important to remember that 10% of fever in hospitalized individuals is from a noninfectious source. “Take a careful history, and do a physical exam to help distinguish infections from other causes of fever,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

Additional investigations to consider in highly immunocompromised patients might include both mycobacterial and fungal cultures, although these studies are otherwise generally low yield. And, she said, “Don’t send catheter-tip cultures – it’s pointless, and it really doesn’t add much information.”

Good clinical judgment still goes a long way toward guiding therapy. “If a patient is stable and it’s not clear whether an antibiotic is needed, consider waiting and re-evaluating later,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Generally, duration of treatment should also be clinically based. “Stop antibiotics as soon as possible, and remove catheters as soon as possible,” Dr. Hanrahan said, adding that few infections really warrant treatment for a fixed amount of time. These include meningitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and many cases of osteomyelitis.

Similarly, when a patient who had been ill now looks well, feels well, and is stable or improving, there’s usually no need for repeat blood cultures, Dr. Hanrahan said. Still, a cautious balance is where most clinicians will wind up.

“I learned a long time ago that I have to do the things that let me go home and sleep at night,” she concluded.

Dr. Hanrahan reported having been a consultant for Gilead, Astellas, and Cempra.

ORLANDO – When is it rational to consider de-escalating, or even stopping, antibiotics for septic patients, and how will patients’ future health be affected by antibiotic use during critical illnesses?

According to Jennifer Hanrahan, DO, of Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, locating the tipping point between optimal care for the individual patient in sepsis, and the importance of antibiotic stewardship is a balancing act. It’s a process guided by laboratory findings, by knowledge of local pathogens and patterns of antimicrobial resistance, and also by clinical judgment, she said at the annual meeting of the Society of Hospital Medicine.

By all means, begin antibiotics for patients with sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan, also medical director of infection prevention at MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, told attendees at a pre-course at HM18. “Prompt initiation of antibiotics for sepsis is critical, and appropriate use of antibiotics decreases mortality.” However, she noted, de-escalation of antibiotics also decreases mortality.

“What is antibiotic stewardship? Most of us think of this as the microbial stewardship police calling to ask you, ‘Why are you using this antibiotic?’’ she said. “It’s really the right antibiotic, for the right diagnosis, for the appropriate duration.”

Of course, Dr. Hanrahan said, any medication is associated with potential adverse events, and antibiotics are no different. “Almost one-third of antibiotics given are either unnecessary or inappropriate,” she said.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very serious public health threat, Dr. Hanrahan affirmed. “Antibiotic use is the most important modifiable factor related to development of antibiotic resistance. With regard to multidrug resistant [MDR] gram negatives, we are running out of antibiotics” to treat these organisms, she said, noting that “Many antibiotics to treat MDRs are “astronomically expensive – and that’s a really big problem.”

It’s important to remember that, when antibiotics are prescribed, “You’re affecting the microbiome not just of that patient, but of those around them,” as resistance factors are potentially spread from one individual’s microbiome to their friends, family, and other contacts, Dr. Hanrahan said.

The later risk of sepsis has also shown to be elevated for individuals who have received high-risk antibiotics such as fluoroquinolones, third- and fourth-generation cephalosporins, beta-lactamase inhibitor formulations, vancomycin, and carbapenems – many of which are also used to treat sepsis. All of these antibiotics kill anaerobic bacteria, Dr. Hanrahan said, and “when you kill anaerobes you do a lot of bad things to people.”

Identifying the pathogens

There are already many frightening players in the antibiotic-resistant landscape. Among them are carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, increasingly common in health care settings. Unfortunately, with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), “we’ve lost the battle,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Acinetobacter is another increasing threat, she said, as is Candida auris, which has caused large outbreaks in Europe. Because it’s resistant to azole antifungals, once C. auris comes to U.S. hospitals, “You’re going to have a really big problem,” she said. Finally, multidrug resistant and extremely drug resistant Pseudomonas species are being encountered with increasing frequency.

And, of course, Clostridium difficile infections continue to ravage older populations. “One in 11 people aged 65 or older will die from C. diff infections,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

For all of these bacteria, she said, “I can’t tell you what antibiotics to use because you have to know what the organisms are in your hospital.” A good resource for tracking local resistance patterns is the information provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, including interactive maps showing health care–associated infections, as well as HealthMap ResistanceOpen, which maps antibiotic resistance alerts across the United States. The CDC also offers training on antibiotic stewardship; Dr. Hanrahan said the several hours she spent completing the training were well spent.

After a broad-spectrum antibiotic is initiated for sepsis, Dr. Hanrahan said that the next infectious disease–related steps should focus on identifying pathogens so antimicrobial therapy can be tailored or scaled back appropriately. In many cases, this will mean obtaining blood cultures – ideally, two sets from two separate sites. It’s no longer thought necessary to separate the blood draws by 20 minutes, or to try to time the draw during a febrile episode, she said.

What is important is to make sure that you’re not treating contamination or colonization – “Treat only clinically significant infections,” Dr. Hanrahan said. A common red herring, especially among elderly individuals coming from assisted living or in patients with indwelling urinary catheters, is a positive urine culture in the absence of signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection. Think twice about whether this truly represents a source of infection, she said. “Don’t treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.”

In order to avoid “chasing contamination,” do not obtain the blood culture samples from a venipuncture site. “Contamination is twice as likely when drawing from a venipuncture site,” Dr. Hanrahan noted. “When possible you should avoid this.”

It’s also important to remember that 10% of fever in hospitalized individuals is from a noninfectious source. “Take a careful history, and do a physical exam to help distinguish infections from other causes of fever,” said Dr. Hanrahan.

Additional investigations to consider in highly immunocompromised patients might include both mycobacterial and fungal cultures, although these studies are otherwise generally low yield. And, she said, “Don’t send catheter-tip cultures – it’s pointless, and it really doesn’t add much information.”

Good clinical judgment still goes a long way toward guiding therapy. “If a patient is stable and it’s not clear whether an antibiotic is needed, consider waiting and re-evaluating later,” Dr. Hanrahan said.

Generally, duration of treatment should also be clinically based. “Stop antibiotics as soon as possible, and remove catheters as soon as possible,” Dr. Hanrahan said, adding that few infections really warrant treatment for a fixed amount of time. These include meningitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and many cases of osteomyelitis.

Similarly, when a patient who had been ill now looks well, feels well, and is stable or improving, there’s usually no need for repeat blood cultures, Dr. Hanrahan said. Still, a cautious balance is where most clinicians will wind up.

“I learned a long time ago that I have to do the things that let me go home and sleep at night,” she concluded.

Dr. Hanrahan reported having been a consultant for Gilead, Astellas, and Cempra.

REPORTING FROM HM18

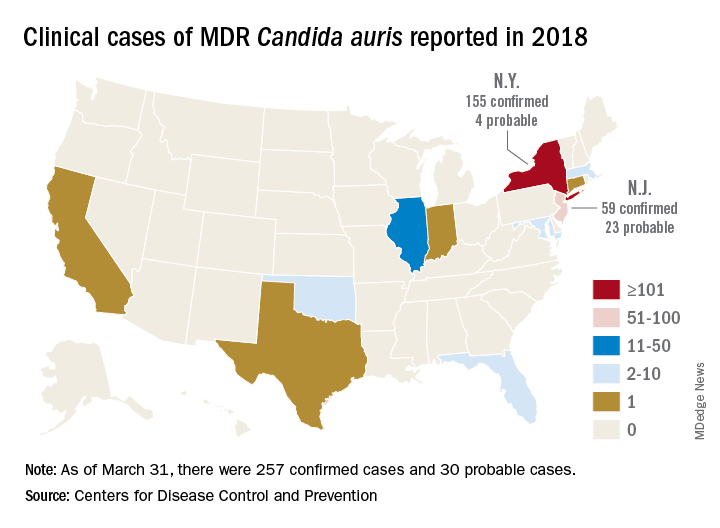

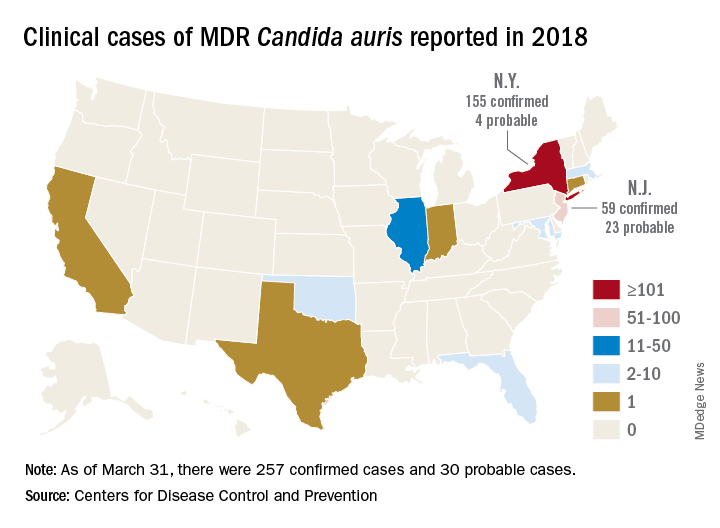

MDR Candida auris is on the move

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

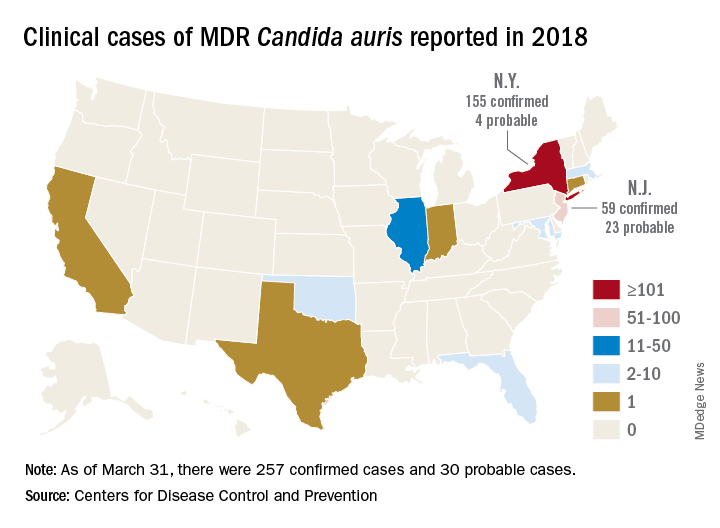

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.

Despite all of these efforts at eradication, infections continued to rise. By November, there were 24 newly colonized patients and nine new candidemia episodes in SICU and regular ICU patients. In December, a new infection control bundle began: A surveillance nurse in the C. auris SICU ward was in charge of compliance; any patient with any yeast growth in culture was isolated, and staff used 2% alcohol chlorhexidine wipes before and after IV catheter handling. Staff also washed down all surfaces three times daily with a disinfectant.

Patients could leave isolation after three consecutive C. auris–negative cultures. After discharge, an ultraviolet light decontamination procedure disinfected each patient room.

The pathogen was almost unbelievably resilient, Dr. Pemán noted in the Mycoses article. “In some cases, C. auris was recovered from walls after cleaning with cationic surface–active products ... it was not known until very recently that these products, as well as quaternary ammonium disinfectants, cannot effectively remove C. auris from surfaces.”

As a result of the previous measures, the outbreak slowed down during December 2016, with two new candidemia cases, but by February, the outbreak resumed with 50 new cases and 18 candidemias detected. Cases continued to emerge throughout 2017.

By September 2017, 250 patients had been colonized; 116 of these were included in the Mycoses report. There were 30 episodes of candidemia (26%); of these, 17 died by 30 days (41.4%). Spondylodiscitis and endocarditis each developed in two patients and one developed ventriculitis.

A separate poster by Dr. Pemán and his colleagues gave more details:

• A 52-year-old woman with C. auris–induced endocarditis died after 4 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN and flucytosine. She had undergone a prosthetic heart valve placement for Ebstein’s anomaly.

• A 71-year-old man with hydrocephalus developed a C. auris–induced infection of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt; he also had undergone cardiovascular surgery and had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. He died despite shunt removal and 8 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 71-year-old man who underwent cardiovascular surgery and received a prosthetic heart valve developed endocarditis. He is alive and at last report, on week 26 of AMB+ECN, flucytosine, and isavuconazole.

• A 68-year-old man who underwent abdominal surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 24 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 48-year old female multiple trauma patient developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 48 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN.

A multivariate analysis determined that antibacterial treatment increased the risk of candidemia by almost 30 times (odds ratio, 29.59). The next highest risk was neutropenia (OR, 20.7) and then simply being a hospital and SICU patient. Dr. Pemán’s poster said, “In the 16 months before the index case, La Fe recorded 89 candidemias, none caused by C. auris. In the 16 months afterward, there were 154 candidemias, largely C. auris. Before April 2016, C. parapsilosis accounted for the largest portion of candidemias (46%) followed by C. albicans. After the index case, C. auris accounted for 42%, followed by C. parapsilosis (21%) and C. albicans (18%).”

Because of its fluconazole resistance, patients with C. auris received a combined antifungal treatment of liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg per day for 5 days, and a standard dose of echinocandin for 3 weeks. Many C. auris strains are echinocandin resistant, Dr. Pemán noted. This particular strain was clonal, different from any other previously reported, he said.

“Our results confirm those previously reported by other authors, that C. auris is grouped in different independent clusters according to its geographical origin. Although all Spanish isolates were genotypically distinct from Indian, Omani, U.K., and Venezuelan isolates, there seems to be some connection with South African isolates.”

Hospital Le Fe continues to struggle with C. auris. As of March, 335 patients have tested positive for the pathogen, and 80 have developed candidemias.

“We feel we may be approaching the end of this episode, but it’s really not possible to be sure,” he said.

Dr. Pemán had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: ECCMID 2018 Peman et al. S0067.

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.