User login

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

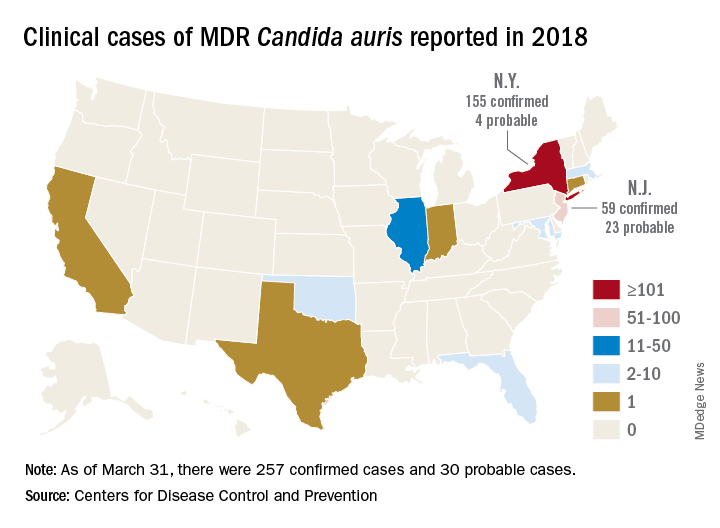

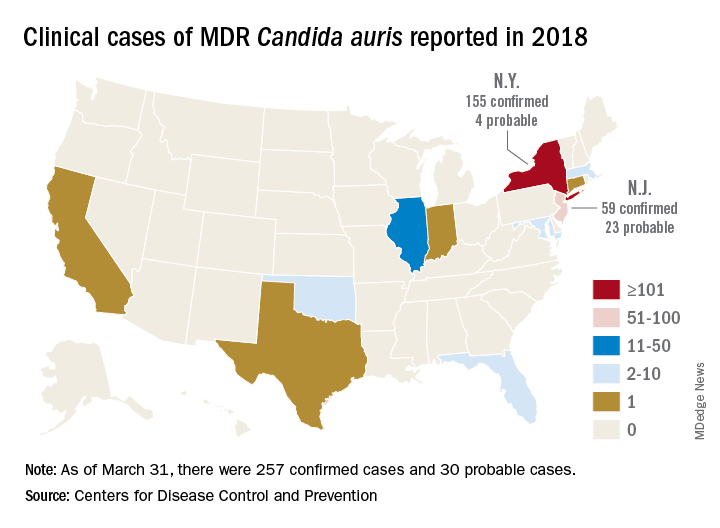

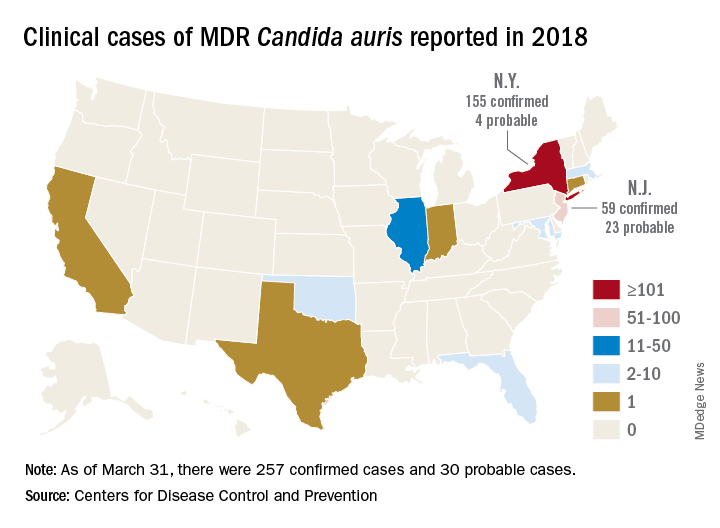

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.

Despite all of these efforts at eradication, infections continued to rise. By November, there were 24 newly colonized patients and nine new candidemia episodes in SICU and regular ICU patients. In December, a new infection control bundle began: A surveillance nurse in the C. auris SICU ward was in charge of compliance; any patient with any yeast growth in culture was isolated, and staff used 2% alcohol chlorhexidine wipes before and after IV catheter handling. Staff also washed down all surfaces three times daily with a disinfectant.

Patients could leave isolation after three consecutive C. auris–negative cultures. After discharge, an ultraviolet light decontamination procedure disinfected each patient room.

The pathogen was almost unbelievably resilient, Dr. Pemán noted in the Mycoses article. “In some cases, C. auris was recovered from walls after cleaning with cationic surface–active products ... it was not known until very recently that these products, as well as quaternary ammonium disinfectants, cannot effectively remove C. auris from surfaces.”

As a result of the previous measures, the outbreak slowed down during December 2016, with two new candidemia cases, but by February, the outbreak resumed with 50 new cases and 18 candidemias detected. Cases continued to emerge throughout 2017.

By September 2017, 250 patients had been colonized; 116 of these were included in the Mycoses report. There were 30 episodes of candidemia (26%); of these, 17 died by 30 days (41.4%). Spondylodiscitis and endocarditis each developed in two patients and one developed ventriculitis.

A separate poster by Dr. Pemán and his colleagues gave more details:

• A 52-year-old woman with C. auris–induced endocarditis died after 4 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN and flucytosine. She had undergone a prosthetic heart valve placement for Ebstein’s anomaly.

• A 71-year-old man with hydrocephalus developed a C. auris–induced infection of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt; he also had undergone cardiovascular surgery and had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. He died despite shunt removal and 8 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 71-year-old man who underwent cardiovascular surgery and received a prosthetic heart valve developed endocarditis. He is alive and at last report, on week 26 of AMB+ECN, flucytosine, and isavuconazole.

• A 68-year-old man who underwent abdominal surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 24 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 48-year old female multiple trauma patient developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 48 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN.

A multivariate analysis determined that antibacterial treatment increased the risk of candidemia by almost 30 times (odds ratio, 29.59). The next highest risk was neutropenia (OR, 20.7) and then simply being a hospital and SICU patient. Dr. Pemán’s poster said, “In the 16 months before the index case, La Fe recorded 89 candidemias, none caused by C. auris. In the 16 months afterward, there were 154 candidemias, largely C. auris. Before April 2016, C. parapsilosis accounted for the largest portion of candidemias (46%) followed by C. albicans. After the index case, C. auris accounted for 42%, followed by C. parapsilosis (21%) and C. albicans (18%).”

Because of its fluconazole resistance, patients with C. auris received a combined antifungal treatment of liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg per day for 5 days, and a standard dose of echinocandin for 3 weeks. Many C. auris strains are echinocandin resistant, Dr. Pemán noted. This particular strain was clonal, different from any other previously reported, he said.

“Our results confirm those previously reported by other authors, that C. auris is grouped in different independent clusters according to its geographical origin. Although all Spanish isolates were genotypically distinct from Indian, Omani, U.K., and Venezuelan isolates, there seems to be some connection with South African isolates.”

Hospital Le Fe continues to struggle with C. auris. As of March, 335 patients have tested positive for the pathogen, and 80 have developed candidemias.

“We feel we may be approaching the end of this episode, but it’s really not possible to be sure,” he said.

Dr. Pemán had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: ECCMID 2018 Peman et al. S0067.

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.

Despite all of these efforts at eradication, infections continued to rise. By November, there were 24 newly colonized patients and nine new candidemia episodes in SICU and regular ICU patients. In December, a new infection control bundle began: A surveillance nurse in the C. auris SICU ward was in charge of compliance; any patient with any yeast growth in culture was isolated, and staff used 2% alcohol chlorhexidine wipes before and after IV catheter handling. Staff also washed down all surfaces three times daily with a disinfectant.

Patients could leave isolation after three consecutive C. auris–negative cultures. After discharge, an ultraviolet light decontamination procedure disinfected each patient room.

The pathogen was almost unbelievably resilient, Dr. Pemán noted in the Mycoses article. “In some cases, C. auris was recovered from walls after cleaning with cationic surface–active products ... it was not known until very recently that these products, as well as quaternary ammonium disinfectants, cannot effectively remove C. auris from surfaces.”

As a result of the previous measures, the outbreak slowed down during December 2016, with two new candidemia cases, but by February, the outbreak resumed with 50 new cases and 18 candidemias detected. Cases continued to emerge throughout 2017.

By September 2017, 250 patients had been colonized; 116 of these were included in the Mycoses report. There were 30 episodes of candidemia (26%); of these, 17 died by 30 days (41.4%). Spondylodiscitis and endocarditis each developed in two patients and one developed ventriculitis.

A separate poster by Dr. Pemán and his colleagues gave more details:

• A 52-year-old woman with C. auris–induced endocarditis died after 4 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN and flucytosine. She had undergone a prosthetic heart valve placement for Ebstein’s anomaly.

• A 71-year-old man with hydrocephalus developed a C. auris–induced infection of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt; he also had undergone cardiovascular surgery and had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. He died despite shunt removal and 8 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 71-year-old man who underwent cardiovascular surgery and received a prosthetic heart valve developed endocarditis. He is alive and at last report, on week 26 of AMB+ECN, flucytosine, and isavuconazole.

• A 68-year-old man who underwent abdominal surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 24 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 48-year old female multiple trauma patient developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 48 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN.

A multivariate analysis determined that antibacterial treatment increased the risk of candidemia by almost 30 times (odds ratio, 29.59). The next highest risk was neutropenia (OR, 20.7) and then simply being a hospital and SICU patient. Dr. Pemán’s poster said, “In the 16 months before the index case, La Fe recorded 89 candidemias, none caused by C. auris. In the 16 months afterward, there were 154 candidemias, largely C. auris. Before April 2016, C. parapsilosis accounted for the largest portion of candidemias (46%) followed by C. albicans. After the index case, C. auris accounted for 42%, followed by C. parapsilosis (21%) and C. albicans (18%).”

Because of its fluconazole resistance, patients with C. auris received a combined antifungal treatment of liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg per day for 5 days, and a standard dose of echinocandin for 3 weeks. Many C. auris strains are echinocandin resistant, Dr. Pemán noted. This particular strain was clonal, different from any other previously reported, he said.

“Our results confirm those previously reported by other authors, that C. auris is grouped in different independent clusters according to its geographical origin. Although all Spanish isolates were genotypically distinct from Indian, Omani, U.K., and Venezuelan isolates, there seems to be some connection with South African isolates.”

Hospital Le Fe continues to struggle with C. auris. As of March, 335 patients have tested positive for the pathogen, and 80 have developed candidemias.

“We feel we may be approaching the end of this episode, but it’s really not possible to be sure,” he said.

Dr. Pemán had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: ECCMID 2018 Peman et al. S0067.

MADRID – The anticipated global emergence of multidrug resistant Candida auris is now an established fact, but a case study presented at the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases annual congress demonstrates just how devastating an outbreak can be to a medical facility and its surgical ICU patients.

The dangerous invasive infection is spreading through Asia, Europe, and the Americas, causing potentially fatal candidemias and proving devilishly difficult to eradicate in health care facilities once it becomes established.

Several multidrug resistant (MDR) C. auris outbreaks were reported at the ECCMID meeting. Most troubling: a continuing outbreak in a hospital in Valencia, Spain, in which 17 patients have died – a 41% fatality rate among those who developed a fulminant C. auris candidemia, Javier Pemán, MD, said at the meeting. The strain appeared to be a clonal population not previously identified in published reports.

“C. auris is hard to remove from the hospital environment,” once it becomes established, said Dr. Pemán of La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital, Valencia. “When an outbreak lasts for months, as ours has, it is difficult, but necessary, to maintain control measures, identify it early in the lab, and isolate and treat patients early with combination therapy.”

He and his team have relied primarily on a combination of amphotericin B and echinocandin (AMB+ECN), although, he added, the optimal dosing and treatment time aren’t known, and many C. auris isolates are echinocandin resistant.

MDR C. auris first appearedin Tokyo in 2009. It then spread to South Korea around 2011, and then appeared across Asia and Western Europe. Its first appearance in Spain was the 2016 Le Fe outbreak.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, single cases have appeared in Austria, Belgium, Malaysia, Norway, and the United Arab Emirates. Canada, Colombia, France, Germany, India, Israel, Japan, Kenya, Kuwait, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, South Korea, South Africa, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela have experienced multiple outbreaks.

The CDC has recorded 257 confirmed and 30 probable cases of MDR C. auris in the United States as of March 31, 2018. Most of these occurred in New York City and New Jersey; a number of patients had recent stays in hospitals in India, Pakistan, South Africa, the UAE, and Venezuela.

Jacques Meis, MD, of the department of medical microbiology and infectious diseases at Canisius Wilhelmina Hospital, Nijmegen, the Netherlands, set the stage for an extended discussion of C. auris at the meeting.

“This is a multidrug resistant yeast that has emerged in the last decade. Some rare isolates are resistant to all three major antifungal classes. Unlike other Candida species, it seems to persist for prolonged periods in health care environments and to colonize patients’ skin. It behaves rather like resistant bacteria.”

Once established in a health care setting – often an intensive care ward – C. auris poses major infection controls challenges and can be very hard to identify and eradicate, said Dr. Meis.

The identification problem is well known. The 2016 CDC alert noted that “commercially available biochemical-based tests, including API strips and VITEK-2, used in many U.S. laboratories to identify fungi, cannot differentiate C. auris from related species. Because of these challenges, clinical laboratories have misidentified the organism as C. haemulonii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae.”

“It’s often misidentified as other Candida species or as Saccharomyces when we investigate with biochemical methods. C. auris is best identified using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF),” said Dr. Meis.

Among the presentations at ECCMID were a report of a U.K. outbreak that affected 70 patients in a neuroscience ICU. It was traced to axillary skin-surface temperature probes, and eradicated only after those probes were removed. More than 90% of the isolates were resistant to fluconazole, voriconazole, and posaconazole; 18% were amphotericin resistant.

A poster described the microbiological characteristics of 50 C. auris isolates taken from 11 hospitals in Korea.

Dr. Pemán described the outbreak in Valencia, which began in April 2016; the report was simultaneously published in the online journal Mycoses (2018 Apr 14. doi: 10.1111/myc.12781).

The index case was a 66-year-old man with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent a liver resection at Hospital Le Fe in April 2016. During his stay in the surgical ICU (SICU), he developed a fungal infection from an unknown, highly fluconazole-resistant yeast. The pathogen was twice misidentified, first as C. haemulonii and then as S. cerevisiae.

Three weeks later, the patient in the adjacent bed developed a similar infection. Sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer confirmed both as a Candida isolate – an organism previously unknown in Spain.

The SICU setup was apparently very conducive to the C. auris life cycle, Dr. Pemán said. It’s a relatively open ward divided into three rooms with 12 beds in each. There are no isolation beds, and dozens of workers have access to the ward every day, including clinical and cleaning staff.

After identifying the second isolate, Dr. Pemán said, infection control staff went into action. They instituted contact precautions in the SICU, and took regular cultures from newly admitted patients and cultures of every SICU patient every 7 days.

“We also started an intense search for more cases throughout the hospital and in 101 SICU workers. Of 305 samples from hands and ears, we found nothing.” They reviewed all the prior fluconazole-resistant Candida isolates; C. auris was not present in the hospital before the index case.

Three weeks after case 2, six new SICU patients tested positive for C. auris (two blood cultures, one vascular line, one respiratory specimen, two rectal swabs, and one urinary tract sample).

“We reinforced contact precautions in colonized and infected patients and started a twice-daily environmental cleaning practice with quaternary ammonium around them,” said Dr. Pemán. They instituted a proactive hospital-wide hand hygiene campaign and spread the word about the outbreak.

By July, there were 11 new colonized patients, 3 of whom developed candidemia. These patients were grouped in the same SICU ward and underwent daily skin treatments with 4% aqueous chlorhexidine wipes.

The environmental inspection found C. auris on beds, tables, walls, and the floor all around infected patients. The pathogen also was living on IV pumps, computer keyboards, and bedside tables. Blood pressure cuffs were a favorite haunt: 19 of 36 samples in the adjacent ICU were positive. These data were separately reported at ECCMID.

Despite all of these efforts at eradication, infections continued to rise. By November, there were 24 newly colonized patients and nine new candidemia episodes in SICU and regular ICU patients. In December, a new infection control bundle began: A surveillance nurse in the C. auris SICU ward was in charge of compliance; any patient with any yeast growth in culture was isolated, and staff used 2% alcohol chlorhexidine wipes before and after IV catheter handling. Staff also washed down all surfaces three times daily with a disinfectant.

Patients could leave isolation after three consecutive C. auris–negative cultures. After discharge, an ultraviolet light decontamination procedure disinfected each patient room.

The pathogen was almost unbelievably resilient, Dr. Pemán noted in the Mycoses article. “In some cases, C. auris was recovered from walls after cleaning with cationic surface–active products ... it was not known until very recently that these products, as well as quaternary ammonium disinfectants, cannot effectively remove C. auris from surfaces.”

As a result of the previous measures, the outbreak slowed down during December 2016, with two new candidemia cases, but by February, the outbreak resumed with 50 new cases and 18 candidemias detected. Cases continued to emerge throughout 2017.

By September 2017, 250 patients had been colonized; 116 of these were included in the Mycoses report. There were 30 episodes of candidemia (26%); of these, 17 died by 30 days (41.4%). Spondylodiscitis and endocarditis each developed in two patients and one developed ventriculitis.

A separate poster by Dr. Pemán and his colleagues gave more details:

• A 52-year-old woman with C. auris–induced endocarditis died after 4 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN and flucytosine. She had undergone a prosthetic heart valve placement for Ebstein’s anomaly.

• A 71-year-old man with hydrocephalus developed a C. auris–induced infection of his ventriculoperitoneal shunt; he also had undergone cardiovascular surgery and had an ischemic cardiomyopathy. He died despite shunt removal and 8 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 71-year-old man who underwent cardiovascular surgery and received a prosthetic heart valve developed endocarditis. He is alive and at last report, on week 26 of AMB+ECN, flucytosine, and isavuconazole.

• A 68-year-old man who underwent abdominal surgery for hepatocellular carcinoma developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 24 weeks of AMB+ECN.

• A 48-year old female multiple trauma patient developed spondylodiscitis and is alive after 48 weeks of treatment with AMB+ECN.

A multivariate analysis determined that antibacterial treatment increased the risk of candidemia by almost 30 times (odds ratio, 29.59). The next highest risk was neutropenia (OR, 20.7) and then simply being a hospital and SICU patient. Dr. Pemán’s poster said, “In the 16 months before the index case, La Fe recorded 89 candidemias, none caused by C. auris. In the 16 months afterward, there were 154 candidemias, largely C. auris. Before April 2016, C. parapsilosis accounted for the largest portion of candidemias (46%) followed by C. albicans. After the index case, C. auris accounted for 42%, followed by C. parapsilosis (21%) and C. albicans (18%).”

Because of its fluconazole resistance, patients with C. auris received a combined antifungal treatment of liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg per day for 5 days, and a standard dose of echinocandin for 3 weeks. Many C. auris strains are echinocandin resistant, Dr. Pemán noted. This particular strain was clonal, different from any other previously reported, he said.

“Our results confirm those previously reported by other authors, that C. auris is grouped in different independent clusters according to its geographical origin. Although all Spanish isolates were genotypically distinct from Indian, Omani, U.K., and Venezuelan isolates, there seems to be some connection with South African isolates.”

Hospital Le Fe continues to struggle with C. auris. As of March, 335 patients have tested positive for the pathogen, and 80 have developed candidemias.

“We feel we may be approaching the end of this episode, but it’s really not possible to be sure,” he said.

Dr. Pemán had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: ECCMID 2018 Peman et al. S0067.

REPORTING FROM ECCMID 2018