User login

A new form of photodynamic therapy remains controversial

A new approach to photodynamic therapy (PDT) – where patients expose their skin to daylight after application of a photosensitizing agent – is gaining traction in Europe, and dermatologists in the United States could soon see more patients inquiring about daylight PDT.

While proponents of daylight PDT point to less pain and greater convenience for patients who have when acne or precancerous actinic keratosis (AK) lesions or are trying to improve the appearance of their skin, not everyone is convinced this approach is safe.

The European experience

Italy is among the European countries where daylight PDT has been evaluated in quality studies. In one Italian study, a split-face study of 35 patients with multiple grade 1 AKs of the face and scalp, no statistically significant difference in the complete response rate of grade 1 AKs at 3 months emerged between the side of the face treated with daylight PDT (87%) and the side treated with conventional PDT (91%). Most of the patients preferred the treatment with daylight PDT, reported the investigators, from the University of L’Aquila (Italy) and the University of Milan (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Oct;29[10]:1926-32).

Another advantage of daylight PDT is the ability to treat a larger surface area, he said, pointing out that it is possible to treat half of the face (200 cm2) in only one session. “The drawback is the cost, but, if you compare this with Picato [ingenol mebutate] and Aldara [imiquimod], you must calculate that they are approved for 25 cm2. Therefore, if you need to treat 200 cm2, you need eight packages,” added Dr. Calzavara-Pinton, who is also the president of the Italian Society of Dermatology.

“Daylight PDT with methyl aminolevulinate ... has proven to be efficacious in the treatment of mild to moderate actinic keratoses on the face and scalp,” agreed Rolf-Markus Szeimies, MD, PhD, head of the department of dermatology and allergology at Klinikum Vest, Recklinghausen, Germany.

He cited two randomized, controlled, split-face studies conducted in Australia and Europe, the COMET-1 and COMET-2 trials in patients with mild to moderate AKs of the face and scalp, which found that cure rates with daylight PDT “were not statistically inferior to conventional PDT with red light.” The biggest advantages “are the single-treatment setting, the possibility to treat large areas in one step, the excellent cosmesis, and the almost total lack of pain during the procedure,” he said in an interview.

While it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States, daylight PDT is a registered treatment modality in Europe, Australia, and South America, said Dr. Szeimies, who presented an update on daylight PDT during a session on PDT at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology in Orlando.

U.S. dermatologists urge caution

The potential benefits of daylight PDT for patients mentioned in the published studies are less pain and fewer office visits, “so it’s more convenient,” said Dr. Spencer, a dermatologist and dermatologic surgeon in private practice in St. Petersburg, Fla. “I don’t think those benefits are strong [enough] to outweigh the potential risks.”

He added that most of the studies are from Norway and other Northern European countries where residents generally are exposed to less intense sun, so the generalizability of the findings could be an issue.

Nevertheless, Dr. Spencer predicted there will be more attention to daylight PDT in the United States soon. “This has certainly caught on in Europe. This is out there, and you’re definitely going to hear more about this.”

Some wavelengths of ultraviolet light are harmful to the skin, “and we don’t want to increase the sensitivity. If anything, you want to protect against it,” she noted. In her practice, when she treats patients with conventional PDT, using ALA (with the Levulan Kerastick) most often combined with blue light therapy, she said she cautions patients to avoid exposure to light for up to 24 hour post procedure.

“If you’re going to photosensitize someone, you need to control the amount of energy they are exposed to until that photosensitizer is deactivated, and sunlight is too broad and, in my view, causes more potential harm than good,” Dr. Day commented.

When administered in a controlled fashion, conventional PDT can improve patient outcomes and appearance, she said. “We use it for acne [and] for precancerous actinic keratoses, and, depending on what we do it with – different chromophores or different color light – you can have benefits for photorejuvenation as well.”

Patient adherence to instructions is paramount

“The idea of taking this and applying it to a much broader population, because acne is so common, is interesting but a little bit scary in the sense that it’s such a poorly controlled experiment,” said Samantha B. Conrad, MD, a dermatologist at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “Every day, the sun is different, people’s habits are different, and, if people have irritated skin, they’re going to take up a lot more of the ALA. If people have thicker, more oily skin, they may not take as much up. It also depends on the climate – it would be different in Chicago than it would be in LA.”

“I always have patients stay indoors with the blinds closed for 24 hours after [therapy]. I try to schedule the treatments in the wintertime here in New York when the daytime is shorter,” Dr. Day said. “We do the treatment in the afternoon, they leave when it’s dark or almost dark, and then they stay indoors the next day.”

Exposure to sunlight after ALA is applied to the skin “will just increase the specific D-dimers and specific [matrix metalloproteinases] uptake that breaks down collagen, accelerates the aging of the skin, and increases your risk of skin cancer,” she pointed out.

“We’ve all had patients who received their Levulan but then didn’t follow instructions and, the day after, got significant burns from something that would not normally precipitate a severe sunburn,” Dr. Conrad added.

She cited a study recently published from South Korea in which 46 patients with facial acne applied a much lower concentration of ALA, a new variant of 5-aminolevulinate ester (1.5% 3-butenyl ALA-bu gel), compared with the 20% concentration in the Levulan Kerastick available in the United States. (J Dermatol. 2016 May;43[5]:515-21). “With this very low concentration, it’s something of a different ball game,” she said.

“Patients applied that gel every other day and then just basically went about their business, getting daily, normal amounts of sun,” she said. After 12 weeks, the researchers reported a 58% reduction in inflammatory acne lesions and a 34% decrease in noninflammatory acne lesions among those who applied the ALA-bu gel to acne lesions every other day and used daylight as the only light source. “There was very little pain involved, and it was relatively easy to do,” Dr. Conrad said.

“You know people are always looking for the next big thing for acne. The idea is interesting but very rough.”

Dr. Spencer, Dr. Day, and Dr. Conrad had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Calzavara-Pinton is a consultant for Leo Pharma, Galderma, Almirall, and Meda AB. Dr. Szeimies is an adviser for Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma, and Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, France and is a member of the speakers bureau for Almirall, Desitin, Galderma, Janssen, Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, France.

A new approach to photodynamic therapy (PDT) – where patients expose their skin to daylight after application of a photosensitizing agent – is gaining traction in Europe, and dermatologists in the United States could soon see more patients inquiring about daylight PDT.

While proponents of daylight PDT point to less pain and greater convenience for patients who have when acne or precancerous actinic keratosis (AK) lesions or are trying to improve the appearance of their skin, not everyone is convinced this approach is safe.

The European experience

Italy is among the European countries where daylight PDT has been evaluated in quality studies. In one Italian study, a split-face study of 35 patients with multiple grade 1 AKs of the face and scalp, no statistically significant difference in the complete response rate of grade 1 AKs at 3 months emerged between the side of the face treated with daylight PDT (87%) and the side treated with conventional PDT (91%). Most of the patients preferred the treatment with daylight PDT, reported the investigators, from the University of L’Aquila (Italy) and the University of Milan (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Oct;29[10]:1926-32).

Another advantage of daylight PDT is the ability to treat a larger surface area, he said, pointing out that it is possible to treat half of the face (200 cm2) in only one session. “The drawback is the cost, but, if you compare this with Picato [ingenol mebutate] and Aldara [imiquimod], you must calculate that they are approved for 25 cm2. Therefore, if you need to treat 200 cm2, you need eight packages,” added Dr. Calzavara-Pinton, who is also the president of the Italian Society of Dermatology.

“Daylight PDT with methyl aminolevulinate ... has proven to be efficacious in the treatment of mild to moderate actinic keratoses on the face and scalp,” agreed Rolf-Markus Szeimies, MD, PhD, head of the department of dermatology and allergology at Klinikum Vest, Recklinghausen, Germany.

He cited two randomized, controlled, split-face studies conducted in Australia and Europe, the COMET-1 and COMET-2 trials in patients with mild to moderate AKs of the face and scalp, which found that cure rates with daylight PDT “were not statistically inferior to conventional PDT with red light.” The biggest advantages “are the single-treatment setting, the possibility to treat large areas in one step, the excellent cosmesis, and the almost total lack of pain during the procedure,” he said in an interview.

While it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States, daylight PDT is a registered treatment modality in Europe, Australia, and South America, said Dr. Szeimies, who presented an update on daylight PDT during a session on PDT at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology in Orlando.

U.S. dermatologists urge caution

The potential benefits of daylight PDT for patients mentioned in the published studies are less pain and fewer office visits, “so it’s more convenient,” said Dr. Spencer, a dermatologist and dermatologic surgeon in private practice in St. Petersburg, Fla. “I don’t think those benefits are strong [enough] to outweigh the potential risks.”

He added that most of the studies are from Norway and other Northern European countries where residents generally are exposed to less intense sun, so the generalizability of the findings could be an issue.

Nevertheless, Dr. Spencer predicted there will be more attention to daylight PDT in the United States soon. “This has certainly caught on in Europe. This is out there, and you’re definitely going to hear more about this.”

Some wavelengths of ultraviolet light are harmful to the skin, “and we don’t want to increase the sensitivity. If anything, you want to protect against it,” she noted. In her practice, when she treats patients with conventional PDT, using ALA (with the Levulan Kerastick) most often combined with blue light therapy, she said she cautions patients to avoid exposure to light for up to 24 hour post procedure.

“If you’re going to photosensitize someone, you need to control the amount of energy they are exposed to until that photosensitizer is deactivated, and sunlight is too broad and, in my view, causes more potential harm than good,” Dr. Day commented.

When administered in a controlled fashion, conventional PDT can improve patient outcomes and appearance, she said. “We use it for acne [and] for precancerous actinic keratoses, and, depending on what we do it with – different chromophores or different color light – you can have benefits for photorejuvenation as well.”

Patient adherence to instructions is paramount

“The idea of taking this and applying it to a much broader population, because acne is so common, is interesting but a little bit scary in the sense that it’s such a poorly controlled experiment,” said Samantha B. Conrad, MD, a dermatologist at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “Every day, the sun is different, people’s habits are different, and, if people have irritated skin, they’re going to take up a lot more of the ALA. If people have thicker, more oily skin, they may not take as much up. It also depends on the climate – it would be different in Chicago than it would be in LA.”

“I always have patients stay indoors with the blinds closed for 24 hours after [therapy]. I try to schedule the treatments in the wintertime here in New York when the daytime is shorter,” Dr. Day said. “We do the treatment in the afternoon, they leave when it’s dark or almost dark, and then they stay indoors the next day.”

Exposure to sunlight after ALA is applied to the skin “will just increase the specific D-dimers and specific [matrix metalloproteinases] uptake that breaks down collagen, accelerates the aging of the skin, and increases your risk of skin cancer,” she pointed out.

“We’ve all had patients who received their Levulan but then didn’t follow instructions and, the day after, got significant burns from something that would not normally precipitate a severe sunburn,” Dr. Conrad added.

She cited a study recently published from South Korea in which 46 patients with facial acne applied a much lower concentration of ALA, a new variant of 5-aminolevulinate ester (1.5% 3-butenyl ALA-bu gel), compared with the 20% concentration in the Levulan Kerastick available in the United States. (J Dermatol. 2016 May;43[5]:515-21). “With this very low concentration, it’s something of a different ball game,” she said.

“Patients applied that gel every other day and then just basically went about their business, getting daily, normal amounts of sun,” she said. After 12 weeks, the researchers reported a 58% reduction in inflammatory acne lesions and a 34% decrease in noninflammatory acne lesions among those who applied the ALA-bu gel to acne lesions every other day and used daylight as the only light source. “There was very little pain involved, and it was relatively easy to do,” Dr. Conrad said.

“You know people are always looking for the next big thing for acne. The idea is interesting but very rough.”

Dr. Spencer, Dr. Day, and Dr. Conrad had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Calzavara-Pinton is a consultant for Leo Pharma, Galderma, Almirall, and Meda AB. Dr. Szeimies is an adviser for Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma, and Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, France and is a member of the speakers bureau for Almirall, Desitin, Galderma, Janssen, Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, France.

A new approach to photodynamic therapy (PDT) – where patients expose their skin to daylight after application of a photosensitizing agent – is gaining traction in Europe, and dermatologists in the United States could soon see more patients inquiring about daylight PDT.

While proponents of daylight PDT point to less pain and greater convenience for patients who have when acne or precancerous actinic keratosis (AK) lesions or are trying to improve the appearance of their skin, not everyone is convinced this approach is safe.

The European experience

Italy is among the European countries where daylight PDT has been evaluated in quality studies. In one Italian study, a split-face study of 35 patients with multiple grade 1 AKs of the face and scalp, no statistically significant difference in the complete response rate of grade 1 AKs at 3 months emerged between the side of the face treated with daylight PDT (87%) and the side treated with conventional PDT (91%). Most of the patients preferred the treatment with daylight PDT, reported the investigators, from the University of L’Aquila (Italy) and the University of Milan (J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015 Oct;29[10]:1926-32).

Another advantage of daylight PDT is the ability to treat a larger surface area, he said, pointing out that it is possible to treat half of the face (200 cm2) in only one session. “The drawback is the cost, but, if you compare this with Picato [ingenol mebutate] and Aldara [imiquimod], you must calculate that they are approved for 25 cm2. Therefore, if you need to treat 200 cm2, you need eight packages,” added Dr. Calzavara-Pinton, who is also the president of the Italian Society of Dermatology.

“Daylight PDT with methyl aminolevulinate ... has proven to be efficacious in the treatment of mild to moderate actinic keratoses on the face and scalp,” agreed Rolf-Markus Szeimies, MD, PhD, head of the department of dermatology and allergology at Klinikum Vest, Recklinghausen, Germany.

He cited two randomized, controlled, split-face studies conducted in Australia and Europe, the COMET-1 and COMET-2 trials in patients with mild to moderate AKs of the face and scalp, which found that cure rates with daylight PDT “were not statistically inferior to conventional PDT with red light.” The biggest advantages “are the single-treatment setting, the possibility to treat large areas in one step, the excellent cosmesis, and the almost total lack of pain during the procedure,” he said in an interview.

While it is not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in the United States, daylight PDT is a registered treatment modality in Europe, Australia, and South America, said Dr. Szeimies, who presented an update on daylight PDT during a session on PDT at the 2017 annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology in Orlando.

U.S. dermatologists urge caution

The potential benefits of daylight PDT for patients mentioned in the published studies are less pain and fewer office visits, “so it’s more convenient,” said Dr. Spencer, a dermatologist and dermatologic surgeon in private practice in St. Petersburg, Fla. “I don’t think those benefits are strong [enough] to outweigh the potential risks.”

He added that most of the studies are from Norway and other Northern European countries where residents generally are exposed to less intense sun, so the generalizability of the findings could be an issue.

Nevertheless, Dr. Spencer predicted there will be more attention to daylight PDT in the United States soon. “This has certainly caught on in Europe. This is out there, and you’re definitely going to hear more about this.”

Some wavelengths of ultraviolet light are harmful to the skin, “and we don’t want to increase the sensitivity. If anything, you want to protect against it,” she noted. In her practice, when she treats patients with conventional PDT, using ALA (with the Levulan Kerastick) most often combined with blue light therapy, she said she cautions patients to avoid exposure to light for up to 24 hour post procedure.

“If you’re going to photosensitize someone, you need to control the amount of energy they are exposed to until that photosensitizer is deactivated, and sunlight is too broad and, in my view, causes more potential harm than good,” Dr. Day commented.

When administered in a controlled fashion, conventional PDT can improve patient outcomes and appearance, she said. “We use it for acne [and] for precancerous actinic keratoses, and, depending on what we do it with – different chromophores or different color light – you can have benefits for photorejuvenation as well.”

Patient adherence to instructions is paramount

“The idea of taking this and applying it to a much broader population, because acne is so common, is interesting but a little bit scary in the sense that it’s such a poorly controlled experiment,” said Samantha B. Conrad, MD, a dermatologist at Northwestern Medicine in Chicago. “Every day, the sun is different, people’s habits are different, and, if people have irritated skin, they’re going to take up a lot more of the ALA. If people have thicker, more oily skin, they may not take as much up. It also depends on the climate – it would be different in Chicago than it would be in LA.”

“I always have patients stay indoors with the blinds closed for 24 hours after [therapy]. I try to schedule the treatments in the wintertime here in New York when the daytime is shorter,” Dr. Day said. “We do the treatment in the afternoon, they leave when it’s dark or almost dark, and then they stay indoors the next day.”

Exposure to sunlight after ALA is applied to the skin “will just increase the specific D-dimers and specific [matrix metalloproteinases] uptake that breaks down collagen, accelerates the aging of the skin, and increases your risk of skin cancer,” she pointed out.

“We’ve all had patients who received their Levulan but then didn’t follow instructions and, the day after, got significant burns from something that would not normally precipitate a severe sunburn,” Dr. Conrad added.

She cited a study recently published from South Korea in which 46 patients with facial acne applied a much lower concentration of ALA, a new variant of 5-aminolevulinate ester (1.5% 3-butenyl ALA-bu gel), compared with the 20% concentration in the Levulan Kerastick available in the United States. (J Dermatol. 2016 May;43[5]:515-21). “With this very low concentration, it’s something of a different ball game,” she said.

“Patients applied that gel every other day and then just basically went about their business, getting daily, normal amounts of sun,” she said. After 12 weeks, the researchers reported a 58% reduction in inflammatory acne lesions and a 34% decrease in noninflammatory acne lesions among those who applied the ALA-bu gel to acne lesions every other day and used daylight as the only light source. “There was very little pain involved, and it was relatively easy to do,” Dr. Conrad said.

“You know people are always looking for the next big thing for acne. The idea is interesting but very rough.”

Dr. Spencer, Dr. Day, and Dr. Conrad had no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Calzavara-Pinton is a consultant for Leo Pharma, Galderma, Almirall, and Meda AB. Dr. Szeimies is an adviser for Almirall, Biofrontera, Galderma, and Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, France and is a member of the speakers bureau for Almirall, Desitin, Galderma, Janssen, Pierre Fabre Dermo Cosmetique, France.

Case series shows benefit of nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma for actinic keratoses

Nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma (NTAP) may serve as an effective, well-tolerated treatment for actinic keratoses, according to findings of a small study published in the February issue of Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

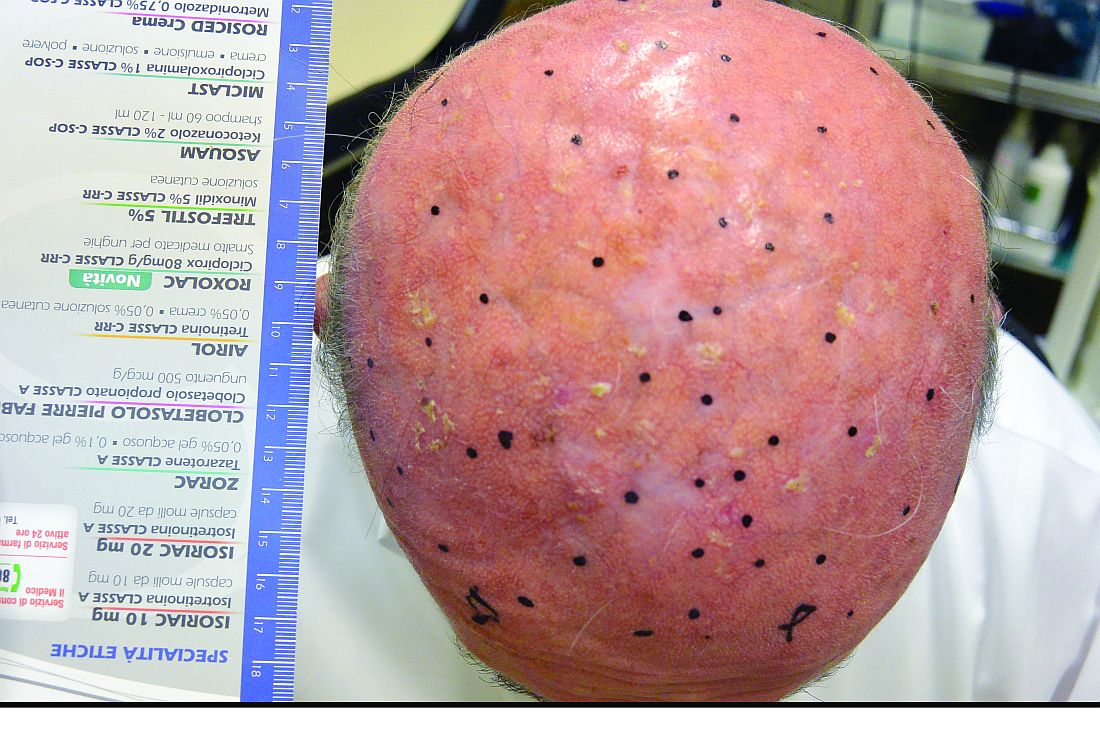

Dr. Peter C. Friedman and his associates at the Skin Center Dermatology Group, New York, wrote that prior studies suggest that NTAP – applied with a hand-held electrode – could selectively induce apoptosis in cancer cells in vitro, and may also up-regulate local and tumor-specific systemic immune response.

In this study, five patients with 5 biopsy-proven and 12 clinically diagnosed actinic keratoses (AKs) were treated with a single dose of NTAP on the target lesion. The procedure involved nanosecond pulses that were applied to the treatment area for 1-2 minutes, an approach designed to provide sufficient dose while avoiding tissue damage (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.004).

At the 1-month follow-up – in which photographs were used to compare before and after treatment – 9 of the 17 AK lesions showed full clinical resolution, with no visible or palpable lesions and only minimal site erythema. Three lesions showed significant improvement, with at least a 50% improvement, and five lesions should minor or no improvement.

Dr. Friedman and his associates noted that current treatment options for AKs all have significant downsides including side effects such as pain and inflammation, and frequent recurrences. There were no adverse effects, such as pain, inflammation, or site reaction, reported during treatment with NTAP or 1 month after treatment.

“Given its very impressive tolerability, NTAP may be an excellent alternative for our current treatment options for AKs, especially if its efficacy and treatment procedure time can be improved and if further, long-term studies demonstrate lasting effects,” the authors wrote. “Further studies are needed to optimize treatment parameters, provide histologic confirmation of treatment effect, and evaluate the long-term benefits of this modality.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma (NTAP) may serve as an effective, well-tolerated treatment for actinic keratoses, according to findings of a small study published in the February issue of Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Peter C. Friedman and his associates at the Skin Center Dermatology Group, New York, wrote that prior studies suggest that NTAP – applied with a hand-held electrode – could selectively induce apoptosis in cancer cells in vitro, and may also up-regulate local and tumor-specific systemic immune response.

In this study, five patients with 5 biopsy-proven and 12 clinically diagnosed actinic keratoses (AKs) were treated with a single dose of NTAP on the target lesion. The procedure involved nanosecond pulses that were applied to the treatment area for 1-2 minutes, an approach designed to provide sufficient dose while avoiding tissue damage (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.004).

At the 1-month follow-up – in which photographs were used to compare before and after treatment – 9 of the 17 AK lesions showed full clinical resolution, with no visible or palpable lesions and only minimal site erythema. Three lesions showed significant improvement, with at least a 50% improvement, and five lesions should minor or no improvement.

Dr. Friedman and his associates noted that current treatment options for AKs all have significant downsides including side effects such as pain and inflammation, and frequent recurrences. There were no adverse effects, such as pain, inflammation, or site reaction, reported during treatment with NTAP or 1 month after treatment.

“Given its very impressive tolerability, NTAP may be an excellent alternative for our current treatment options for AKs, especially if its efficacy and treatment procedure time can be improved and if further, long-term studies demonstrate lasting effects,” the authors wrote. “Further studies are needed to optimize treatment parameters, provide histologic confirmation of treatment effect, and evaluate the long-term benefits of this modality.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

Nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma (NTAP) may serve as an effective, well-tolerated treatment for actinic keratoses, according to findings of a small study published in the February issue of Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Peter C. Friedman and his associates at the Skin Center Dermatology Group, New York, wrote that prior studies suggest that NTAP – applied with a hand-held electrode – could selectively induce apoptosis in cancer cells in vitro, and may also up-regulate local and tumor-specific systemic immune response.

In this study, five patients with 5 biopsy-proven and 12 clinically diagnosed actinic keratoses (AKs) were treated with a single dose of NTAP on the target lesion. The procedure involved nanosecond pulses that were applied to the treatment area for 1-2 minutes, an approach designed to provide sufficient dose while avoiding tissue damage (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017 Feb. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.09.004).

At the 1-month follow-up – in which photographs were used to compare before and after treatment – 9 of the 17 AK lesions showed full clinical resolution, with no visible or palpable lesions and only minimal site erythema. Three lesions showed significant improvement, with at least a 50% improvement, and five lesions should minor or no improvement.

Dr. Friedman and his associates noted that current treatment options for AKs all have significant downsides including side effects such as pain and inflammation, and frequent recurrences. There were no adverse effects, such as pain, inflammation, or site reaction, reported during treatment with NTAP or 1 month after treatment.

“Given its very impressive tolerability, NTAP may be an excellent alternative for our current treatment options for AKs, especially if its efficacy and treatment procedure time can be improved and if further, long-term studies demonstrate lasting effects,” the authors wrote. “Further studies are needed to optimize treatment parameters, provide histologic confirmation of treatment effect, and evaluate the long-term benefits of this modality.”

No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF DERMATOLOGY

Key clinical point: Nonthermal atmospheric pressure plasma may be an effective, well-tolerated treatment for actinic keratoses.

Major finding: One month after a single treatment with NTAP, 9 of 17 AK lesions showed full clinical resolution and 3 lesions showed significant improvement.

Data source: Case series in five patients with actinic keratoses.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

But you told me...

“The other doctor I went to told me that the spot he biopsied on my nose was a skin cancer,” Larry said. “But he told me just to keep an eye on it.”

I always try not to roll my eyes when a patient quotes another doctor, especially if the quote doesn’t make much sense. In the first place, it’s bad form to act like you’re smarter than somebody else. In the second place, you probably aren’t.

In the third place, what the patient says the doctor said may not be what the doctor actually said. I have many chances to learn this firsthand, such as when patients quote me incorrectly to myself.

No, I didn’t.

I point out to students that, to patients, calling a mole benign is always provisional. They’re happy that it’s benign today. Tomorrow, who knows?

That’s why when I reassure people about moles I’m not worried about, I say, “It’s benign... and it will always be benign.” When they look startled – as they often do – I elaborate: “Because if I thought it could turn into skin cancer, I would have to remove it right now.” Then they nod, somewhat tentatively. What I just said clearly made sense, only it contradicts what they always assumed was true, which is that you should always keep an eye on things.

Since I thought Steve’s mole was benign, I did not tell him that we need to keep an eye on it, any more than Larry’s previous doctor had told him just to keep an eye on a biopsy-proved skin cancer. Steve just thought that’s what I must have said, because that’s what makes sense to him.

Then there was Amanda, who had stopped her acne gel weeks before. “It was making me worse,” she explained, “and you told me to stop the medicine if anything happened.”

Nope, not even close.

What I did say – what I always say – was this: “These are the reactions you might experience. If you think you’re getting them or any others, call me right away, so I can consider changing to something different.” I never tell patients to just stop treatment and not tell anyone. Who would?

The opposite happens too. Just as some people stop medication without telling their doctors, others find it just as hard to stop treatment even when they’re instructed to.

“When your seborrhea quiets down,” I say, “you can stop the cream. Resume it when you need to, but stop again as soon as you clear up.”

Easy for me to say. But in walks Phillip. He’s been using applying desonide daily for 6 years. “You said I should keep using it,” he explains.

No, I didn’t. “What I was trying to say,” I politely explain, “is that when your skin feels fine, it’s OK to stop. They you can use it again when the rash comes back. Keeping up applying the cream doesn’t stop the rash from coming back if it’s going to.”

Philip nods. I think he understands. But I thought so last time too, didn’t I?

I should also give a shout-out to the patients who say, “I’ve been using the clotrimazole-betamethasone cream you prescribed...”

No, I did not prescribe clotrimazole-betamethasone! I would lose my membership in the dermatologists’ union.

Researchers who study cross-cultural practice look into issues of miscommunication between providers and consumers who come from distant cultures, where basic notions get in the way of each party’s understanding the other. No one seems that interested in studying all the miscommunication that goes on between educated native-English speakers, in medical offices no less than in the halls of the legislature.

I got hold of Larry’s biopsy report, by the way. It was read out as “actinic keratosis,” which is why Larry’s former doctor had told him that they would just watch it.

I called Larry. “It was not an actual cancer,” I told him. “Just precancerous. Come back in 6 months. We’ll keep an eye on it.”

That was clear. I think.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient” is now available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

“The other doctor I went to told me that the spot he biopsied on my nose was a skin cancer,” Larry said. “But he told me just to keep an eye on it.”

I always try not to roll my eyes when a patient quotes another doctor, especially if the quote doesn’t make much sense. In the first place, it’s bad form to act like you’re smarter than somebody else. In the second place, you probably aren’t.

In the third place, what the patient says the doctor said may not be what the doctor actually said. I have many chances to learn this firsthand, such as when patients quote me incorrectly to myself.

No, I didn’t.

I point out to students that, to patients, calling a mole benign is always provisional. They’re happy that it’s benign today. Tomorrow, who knows?

That’s why when I reassure people about moles I’m not worried about, I say, “It’s benign... and it will always be benign.” When they look startled – as they often do – I elaborate: “Because if I thought it could turn into skin cancer, I would have to remove it right now.” Then they nod, somewhat tentatively. What I just said clearly made sense, only it contradicts what they always assumed was true, which is that you should always keep an eye on things.

Since I thought Steve’s mole was benign, I did not tell him that we need to keep an eye on it, any more than Larry’s previous doctor had told him just to keep an eye on a biopsy-proved skin cancer. Steve just thought that’s what I must have said, because that’s what makes sense to him.

Then there was Amanda, who had stopped her acne gel weeks before. “It was making me worse,” she explained, “and you told me to stop the medicine if anything happened.”

Nope, not even close.

What I did say – what I always say – was this: “These are the reactions you might experience. If you think you’re getting them or any others, call me right away, so I can consider changing to something different.” I never tell patients to just stop treatment and not tell anyone. Who would?

The opposite happens too. Just as some people stop medication without telling their doctors, others find it just as hard to stop treatment even when they’re instructed to.

“When your seborrhea quiets down,” I say, “you can stop the cream. Resume it when you need to, but stop again as soon as you clear up.”

Easy for me to say. But in walks Phillip. He’s been using applying desonide daily for 6 years. “You said I should keep using it,” he explains.

No, I didn’t. “What I was trying to say,” I politely explain, “is that when your skin feels fine, it’s OK to stop. They you can use it again when the rash comes back. Keeping up applying the cream doesn’t stop the rash from coming back if it’s going to.”

Philip nods. I think he understands. But I thought so last time too, didn’t I?

I should also give a shout-out to the patients who say, “I’ve been using the clotrimazole-betamethasone cream you prescribed...”

No, I did not prescribe clotrimazole-betamethasone! I would lose my membership in the dermatologists’ union.

Researchers who study cross-cultural practice look into issues of miscommunication between providers and consumers who come from distant cultures, where basic notions get in the way of each party’s understanding the other. No one seems that interested in studying all the miscommunication that goes on between educated native-English speakers, in medical offices no less than in the halls of the legislature.

I got hold of Larry’s biopsy report, by the way. It was read out as “actinic keratosis,” which is why Larry’s former doctor had told him that they would just watch it.

I called Larry. “It was not an actual cancer,” I told him. “Just precancerous. Come back in 6 months. We’ll keep an eye on it.”

That was clear. I think.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient” is now available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

“The other doctor I went to told me that the spot he biopsied on my nose was a skin cancer,” Larry said. “But he told me just to keep an eye on it.”

I always try not to roll my eyes when a patient quotes another doctor, especially if the quote doesn’t make much sense. In the first place, it’s bad form to act like you’re smarter than somebody else. In the second place, you probably aren’t.

In the third place, what the patient says the doctor said may not be what the doctor actually said. I have many chances to learn this firsthand, such as when patients quote me incorrectly to myself.

No, I didn’t.

I point out to students that, to patients, calling a mole benign is always provisional. They’re happy that it’s benign today. Tomorrow, who knows?

That’s why when I reassure people about moles I’m not worried about, I say, “It’s benign... and it will always be benign.” When they look startled – as they often do – I elaborate: “Because if I thought it could turn into skin cancer, I would have to remove it right now.” Then they nod, somewhat tentatively. What I just said clearly made sense, only it contradicts what they always assumed was true, which is that you should always keep an eye on things.

Since I thought Steve’s mole was benign, I did not tell him that we need to keep an eye on it, any more than Larry’s previous doctor had told him just to keep an eye on a biopsy-proved skin cancer. Steve just thought that’s what I must have said, because that’s what makes sense to him.

Then there was Amanda, who had stopped her acne gel weeks before. “It was making me worse,” she explained, “and you told me to stop the medicine if anything happened.”

Nope, not even close.

What I did say – what I always say – was this: “These are the reactions you might experience. If you think you’re getting them or any others, call me right away, so I can consider changing to something different.” I never tell patients to just stop treatment and not tell anyone. Who would?

The opposite happens too. Just as some people stop medication without telling their doctors, others find it just as hard to stop treatment even when they’re instructed to.

“When your seborrhea quiets down,” I say, “you can stop the cream. Resume it when you need to, but stop again as soon as you clear up.”

Easy for me to say. But in walks Phillip. He’s been using applying desonide daily for 6 years. “You said I should keep using it,” he explains.

No, I didn’t. “What I was trying to say,” I politely explain, “is that when your skin feels fine, it’s OK to stop. They you can use it again when the rash comes back. Keeping up applying the cream doesn’t stop the rash from coming back if it’s going to.”

Philip nods. I think he understands. But I thought so last time too, didn’t I?

I should also give a shout-out to the patients who say, “I’ve been using the clotrimazole-betamethasone cream you prescribed...”

No, I did not prescribe clotrimazole-betamethasone! I would lose my membership in the dermatologists’ union.

Researchers who study cross-cultural practice look into issues of miscommunication between providers and consumers who come from distant cultures, where basic notions get in the way of each party’s understanding the other. No one seems that interested in studying all the miscommunication that goes on between educated native-English speakers, in medical offices no less than in the halls of the legislature.

I got hold of Larry’s biopsy report, by the way. It was read out as “actinic keratosis,” which is why Larry’s former doctor had told him that they would just watch it.

I called Larry. “It was not an actual cancer,” I told him. “Just precancerous. Come back in 6 months. We’ll keep an eye on it.”

That was clear. I think.

Dr. Rockoff practices dermatology in Brookline, Mass., and is a longtime contributor to Dermatology News. He serves on the clinical faculty at Tufts University, Boston, and has taught senior medical students and other trainees for 30 years. His new book “Act Like a Doctor, Think Like a Patient” is now available at amazon.com and barnesandnoble.com. This is his second book. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Addition of calcipotriene to 5-FU increases efficacy, tolerability as AK treatment

A combined formulation of calcipotriol and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) outperformed 5-FU alone in reducing the number of actinic keratoses (AKs), with a shorter treatment course and less inflammation than typically seen with 5-FU alone, researchers reported in a study published online in November.

5-FU is effective, but it produces crusting and significant irritation, and is temporarily disfiguring, creating discomfort and inconvenience that often leads to poor patient compliance with treatment.

After demonstrating that the combined treatment reduces AKs in mice, they conducted the study of 131 patients with AKs, randomized to treatment with a cream containing 5% 5-FU and 0.005% calcipotriol, or Vaseline plus 5% 5-FU alone. Participants applied the treatments twice per day for 4 days.

Eight weeks after treatment, the combination group had a mean 87.8% reduction in the number of AKs on the face, compared with 26.3% of the 5-FU controls. The treatment group also had better responses on the scalp (a mean 76.4% reduction in AKs versus 5.7%), right upper extremity (68.8% versus 9.6%), and left upper extremity (79% versus 16.3%). All differences were statistically significant (P less than .0001 for all comparisons).

“The greater efficacy of calcipotriol plus 5-FU versus Vaseline plus 5-FU treatment in eliminating actinic keratoses remained highly significant after controlling for the baseline actinic keratosis count, age, and sex of the participants,” they wrote (J Clin Invest. 2016 Nov 21. pii: 89820. doi: 10.1172/JCI89820).

Significantly more of those in the combination group has skin redness during treatment, and 39% experienced a burning sensation on treated skin, compared with 13% of the 5-FU treated group. The rate of scaling and itching of treated skin during treatment was similar, and no patients had crusting or wounding of the treated skin.

“It was incredibly well tolerated. There wasn’t as much discomfort or crusting to where people had to stop. And patients who had used 5-FU in the past preferred this shorter treatment course as well as the type and amount of inflammation they had,” compared with their previous experience, Lynn Cornelius, MD, professor and chief of dermatology, Washington University, Saint Louis, said in an interview. “And it was more efficacious,” added Dr. Cornelius, who was one of the study authors.

The trial was investigator initiated. Two authors received grants from the American Skin Association, the Dermatology Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the American Philosophical Society, the La Roche-Posay Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health; three investigators were supported by an NIH grant. Dr. Cornelius reported having no financial disclosures.

A combined formulation of calcipotriol and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) outperformed 5-FU alone in reducing the number of actinic keratoses (AKs), with a shorter treatment course and less inflammation than typically seen with 5-FU alone, researchers reported in a study published online in November.

5-FU is effective, but it produces crusting and significant irritation, and is temporarily disfiguring, creating discomfort and inconvenience that often leads to poor patient compliance with treatment.

After demonstrating that the combined treatment reduces AKs in mice, they conducted the study of 131 patients with AKs, randomized to treatment with a cream containing 5% 5-FU and 0.005% calcipotriol, or Vaseline plus 5% 5-FU alone. Participants applied the treatments twice per day for 4 days.

Eight weeks after treatment, the combination group had a mean 87.8% reduction in the number of AKs on the face, compared with 26.3% of the 5-FU controls. The treatment group also had better responses on the scalp (a mean 76.4% reduction in AKs versus 5.7%), right upper extremity (68.8% versus 9.6%), and left upper extremity (79% versus 16.3%). All differences were statistically significant (P less than .0001 for all comparisons).

“The greater efficacy of calcipotriol plus 5-FU versus Vaseline plus 5-FU treatment in eliminating actinic keratoses remained highly significant after controlling for the baseline actinic keratosis count, age, and sex of the participants,” they wrote (J Clin Invest. 2016 Nov 21. pii: 89820. doi: 10.1172/JCI89820).

Significantly more of those in the combination group has skin redness during treatment, and 39% experienced a burning sensation on treated skin, compared with 13% of the 5-FU treated group. The rate of scaling and itching of treated skin during treatment was similar, and no patients had crusting or wounding of the treated skin.

“It was incredibly well tolerated. There wasn’t as much discomfort or crusting to where people had to stop. And patients who had used 5-FU in the past preferred this shorter treatment course as well as the type and amount of inflammation they had,” compared with their previous experience, Lynn Cornelius, MD, professor and chief of dermatology, Washington University, Saint Louis, said in an interview. “And it was more efficacious,” added Dr. Cornelius, who was one of the study authors.

The trial was investigator initiated. Two authors received grants from the American Skin Association, the Dermatology Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the American Philosophical Society, the La Roche-Posay Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health; three investigators were supported by an NIH grant. Dr. Cornelius reported having no financial disclosures.

A combined formulation of calcipotriol and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) outperformed 5-FU alone in reducing the number of actinic keratoses (AKs), with a shorter treatment course and less inflammation than typically seen with 5-FU alone, researchers reported in a study published online in November.

5-FU is effective, but it produces crusting and significant irritation, and is temporarily disfiguring, creating discomfort and inconvenience that often leads to poor patient compliance with treatment.

After demonstrating that the combined treatment reduces AKs in mice, they conducted the study of 131 patients with AKs, randomized to treatment with a cream containing 5% 5-FU and 0.005% calcipotriol, or Vaseline plus 5% 5-FU alone. Participants applied the treatments twice per day for 4 days.

Eight weeks after treatment, the combination group had a mean 87.8% reduction in the number of AKs on the face, compared with 26.3% of the 5-FU controls. The treatment group also had better responses on the scalp (a mean 76.4% reduction in AKs versus 5.7%), right upper extremity (68.8% versus 9.6%), and left upper extremity (79% versus 16.3%). All differences were statistically significant (P less than .0001 for all comparisons).

“The greater efficacy of calcipotriol plus 5-FU versus Vaseline plus 5-FU treatment in eliminating actinic keratoses remained highly significant after controlling for the baseline actinic keratosis count, age, and sex of the participants,” they wrote (J Clin Invest. 2016 Nov 21. pii: 89820. doi: 10.1172/JCI89820).

Significantly more of those in the combination group has skin redness during treatment, and 39% experienced a burning sensation on treated skin, compared with 13% of the 5-FU treated group. The rate of scaling and itching of treated skin during treatment was similar, and no patients had crusting or wounding of the treated skin.

“It was incredibly well tolerated. There wasn’t as much discomfort or crusting to where people had to stop. And patients who had used 5-FU in the past preferred this shorter treatment course as well as the type and amount of inflammation they had,” compared with their previous experience, Lynn Cornelius, MD, professor and chief of dermatology, Washington University, Saint Louis, said in an interview. “And it was more efficacious,” added Dr. Cornelius, who was one of the study authors.

The trial was investigator initiated. Two authors received grants from the American Skin Association, the Dermatology Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the American Philosophical Society, the La Roche-Posay Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health; three investigators were supported by an NIH grant. Dr. Cornelius reported having no financial disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL INVESTIGATION

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The combination cream reduced the number of AKs on the face by 87.8%, compared with 5-FU alone.

Data source: A randomized, placebo controlled trial of 131 subjects with AKs.

Disclosures: The trial was investigator initiated. Two authors received grants from the American Skin Association, the Dermatology Foundation, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, the American Philosophical Society, the La Roche-Posay Research Foundation, and the National Institutes of Health; three investigators were supported by an NIH grant. Dr. Cornelius reported having no financial disclosures.

Dermoscopy Update and Noninvasive Imaging Devices for Skin Cancer: Report From the Mount Sinai Winter Symposium

At the 19th Annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium, Dr. Orit Markowitz provided an update on dermoscopy as a first-line noninvasive imaging modality for skin cancer screening and diagnosis along with reflectance confocal microscopy and dynamic optical coherence tomography. She explained how noninvasive imaging offers a more complete picture of lesions along with what is seen clinically and on pathology and discussed how it can help catch aggressive melanomas and other skin cancers at earlier stages. For these reasons, she emphasized that increased use of dermoscopy can be used to justify the need for regular skin cancer screenings. Finally, she discussed how noninvasive imaging can be used to guide dermatologists in performing optimal biposies of suspicious lesions.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

At the 19th Annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium, Dr. Orit Markowitz provided an update on dermoscopy as a first-line noninvasive imaging modality for skin cancer screening and diagnosis along with reflectance confocal microscopy and dynamic optical coherence tomography. She explained how noninvasive imaging offers a more complete picture of lesions along with what is seen clinically and on pathology and discussed how it can help catch aggressive melanomas and other skin cancers at earlier stages. For these reasons, she emphasized that increased use of dermoscopy can be used to justify the need for regular skin cancer screenings. Finally, she discussed how noninvasive imaging can be used to guide dermatologists in performing optimal biposies of suspicious lesions.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

At the 19th Annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium, Dr. Orit Markowitz provided an update on dermoscopy as a first-line noninvasive imaging modality for skin cancer screening and diagnosis along with reflectance confocal microscopy and dynamic optical coherence tomography. She explained how noninvasive imaging offers a more complete picture of lesions along with what is seen clinically and on pathology and discussed how it can help catch aggressive melanomas and other skin cancers at earlier stages. For these reasons, she emphasized that increased use of dermoscopy can be used to justify the need for regular skin cancer screenings. Finally, she discussed how noninvasive imaging can be used to guide dermatologists in performing optimal biposies of suspicious lesions.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dermoscopy Pearls: Report From the Mount Sinai Winter Symposium

At the 19th Annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium, Dr. Orit Markowitz addressed some common questions physicians have about dermoscopy, including what kind of dermatoscope to buy, how to incorporate dermoscopy into a dermatology practice, and how to efficiently perform skin examinations using a dermatoscope. She also emphasized the importance of attending courses and workshops to learn how to utilize dermoscopy and other noninvasive imaging devices effectively.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

At the 19th Annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium, Dr. Orit Markowitz addressed some common questions physicians have about dermoscopy, including what kind of dermatoscope to buy, how to incorporate dermoscopy into a dermatology practice, and how to efficiently perform skin examinations using a dermatoscope. She also emphasized the importance of attending courses and workshops to learn how to utilize dermoscopy and other noninvasive imaging devices effectively.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

At the 19th Annual Mount Sinai Winter Symposium, Dr. Orit Markowitz addressed some common questions physicians have about dermoscopy, including what kind of dermatoscope to buy, how to incorporate dermoscopy into a dermatology practice, and how to efficiently perform skin examinations using a dermatoscope. She also emphasized the importance of attending courses and workshops to learn how to utilize dermoscopy and other noninvasive imaging devices effectively.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Timed Sequential Therapy for Actinic Keratosis: Report From the Mount Sinai Winter Symposium

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Tinea Capitis Caused by Trichophyton rubrum Mimicking Favus

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

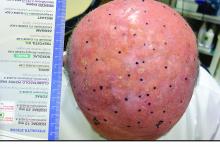

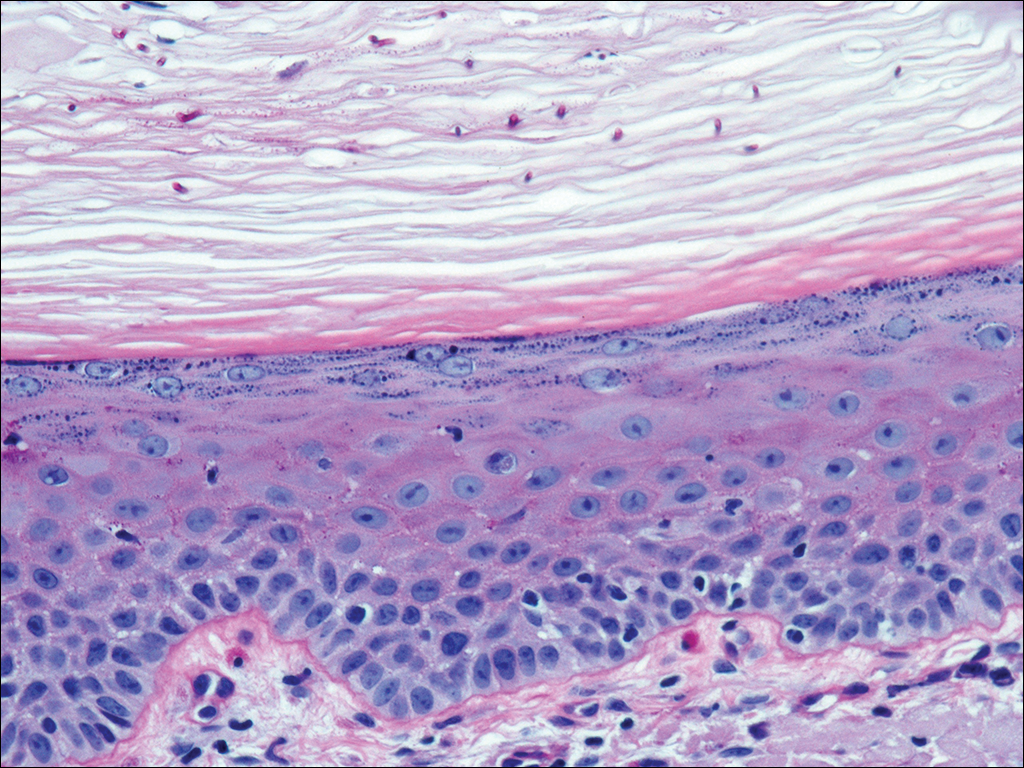

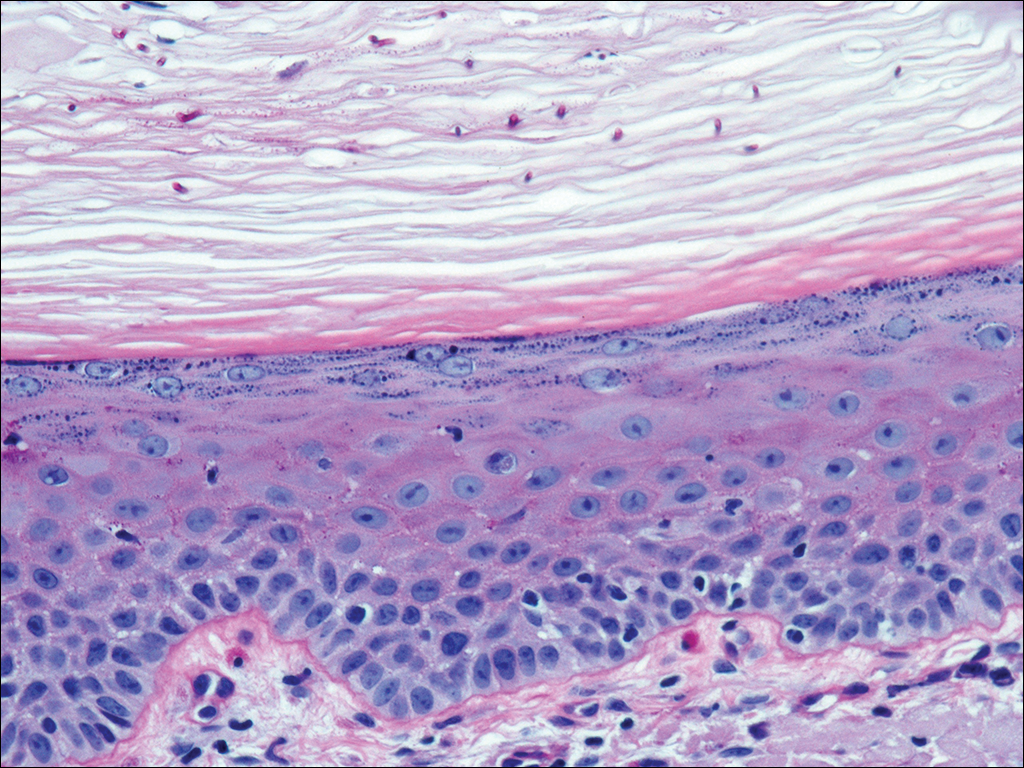

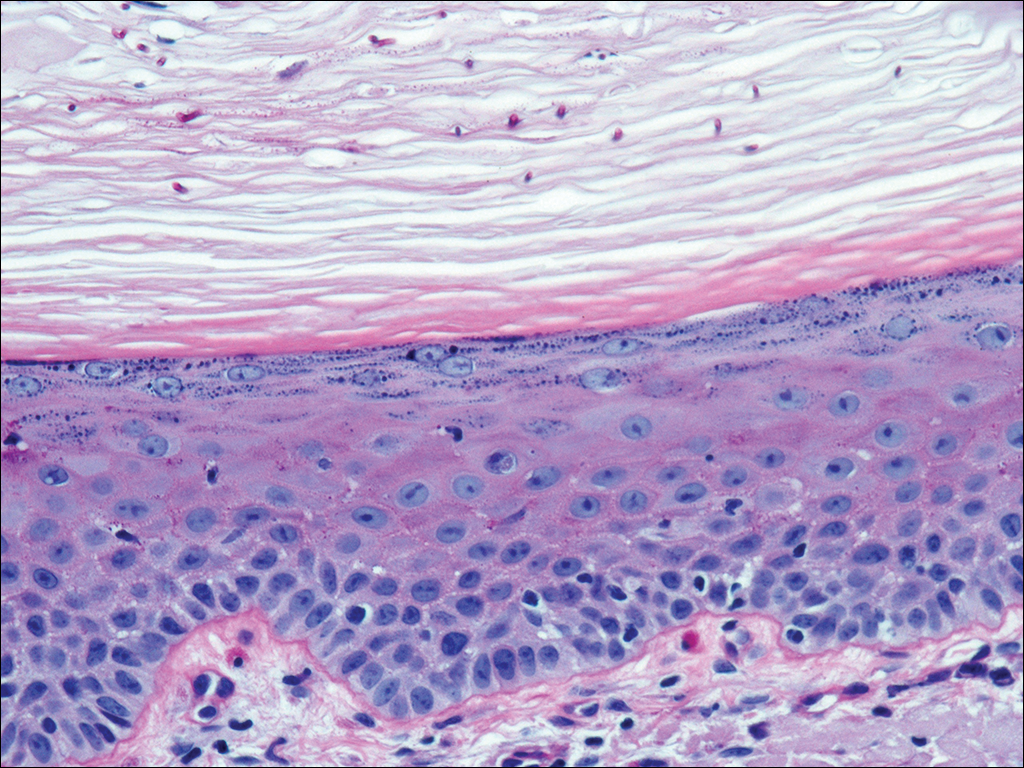

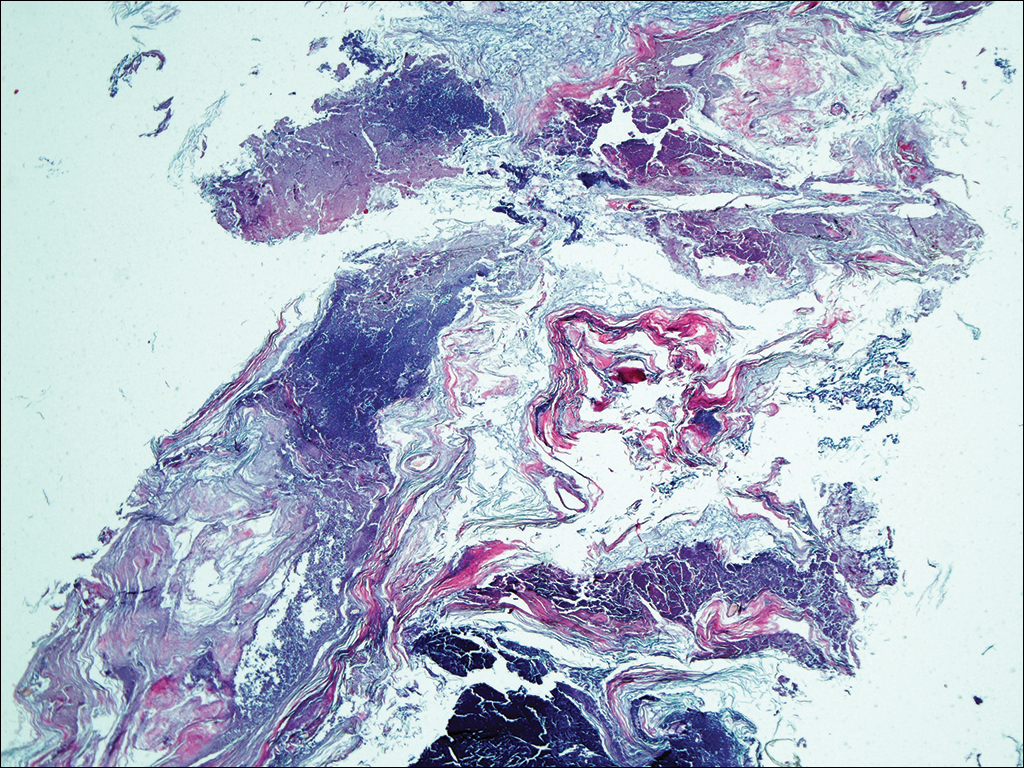

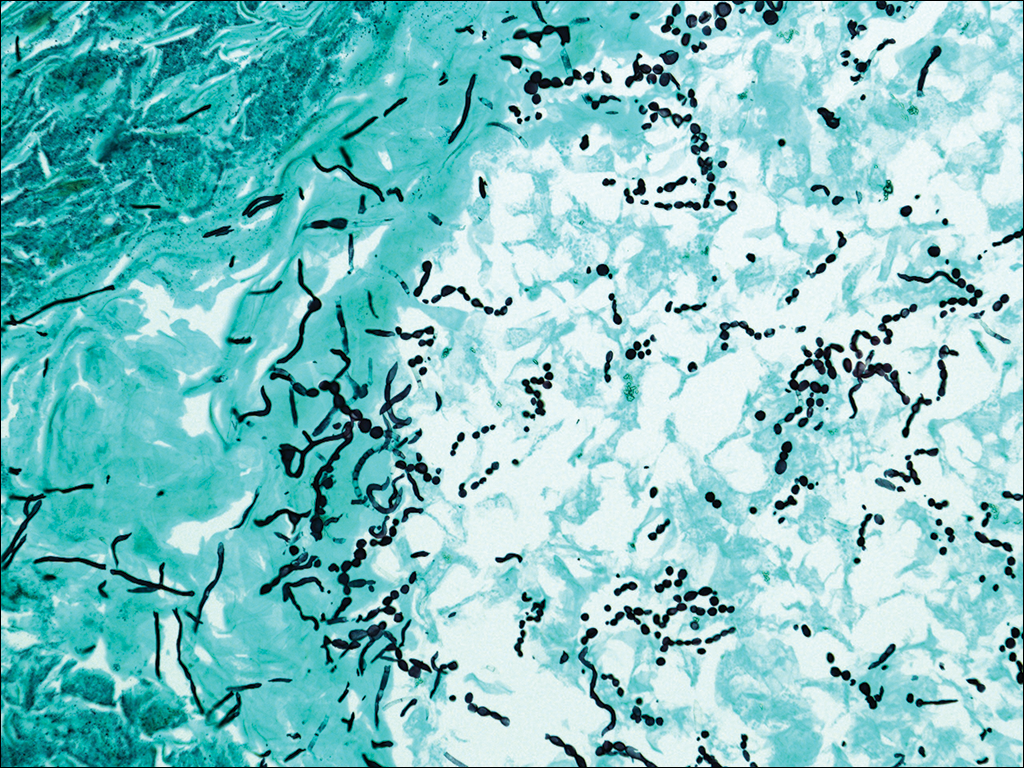

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

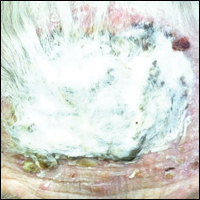

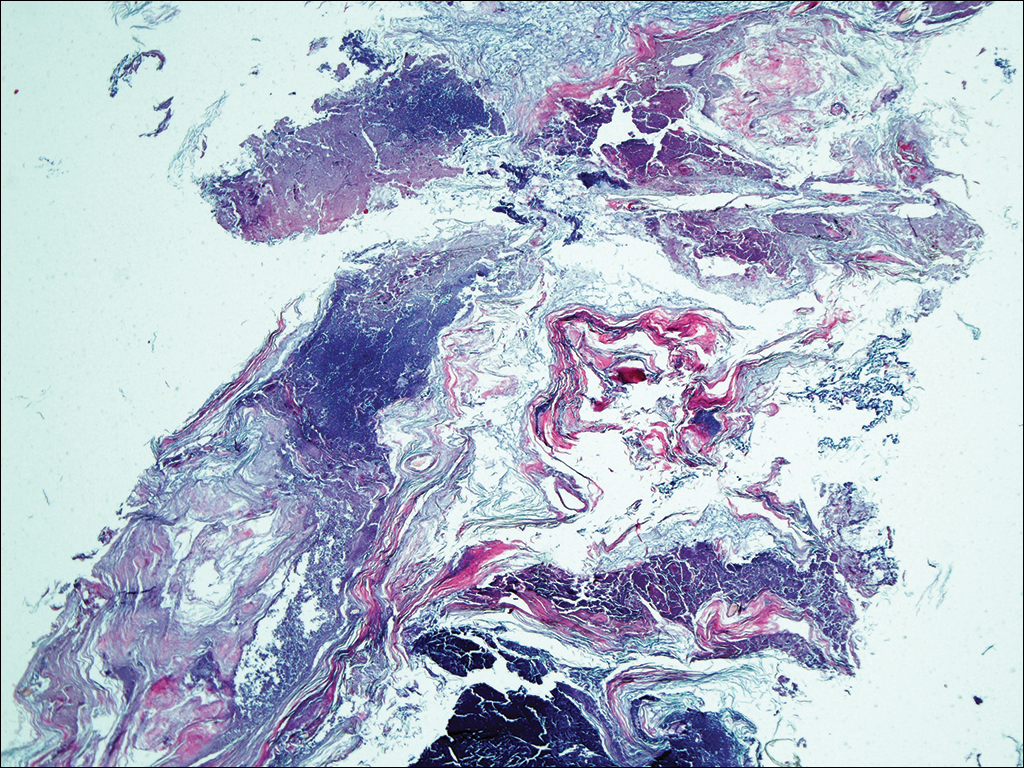

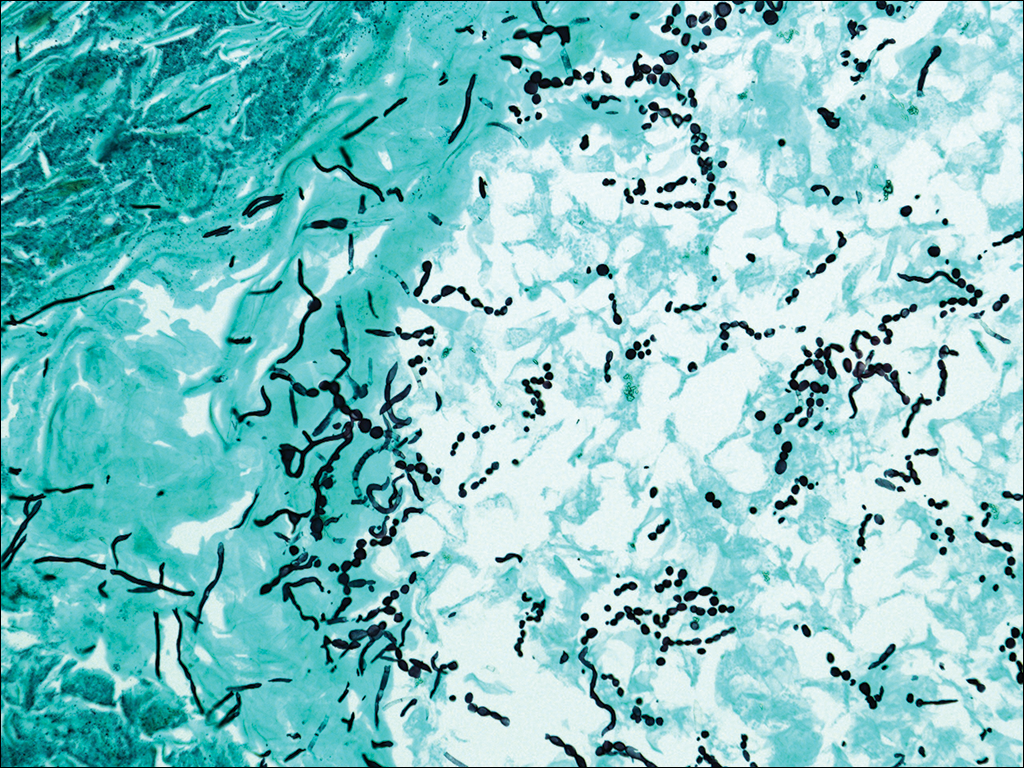

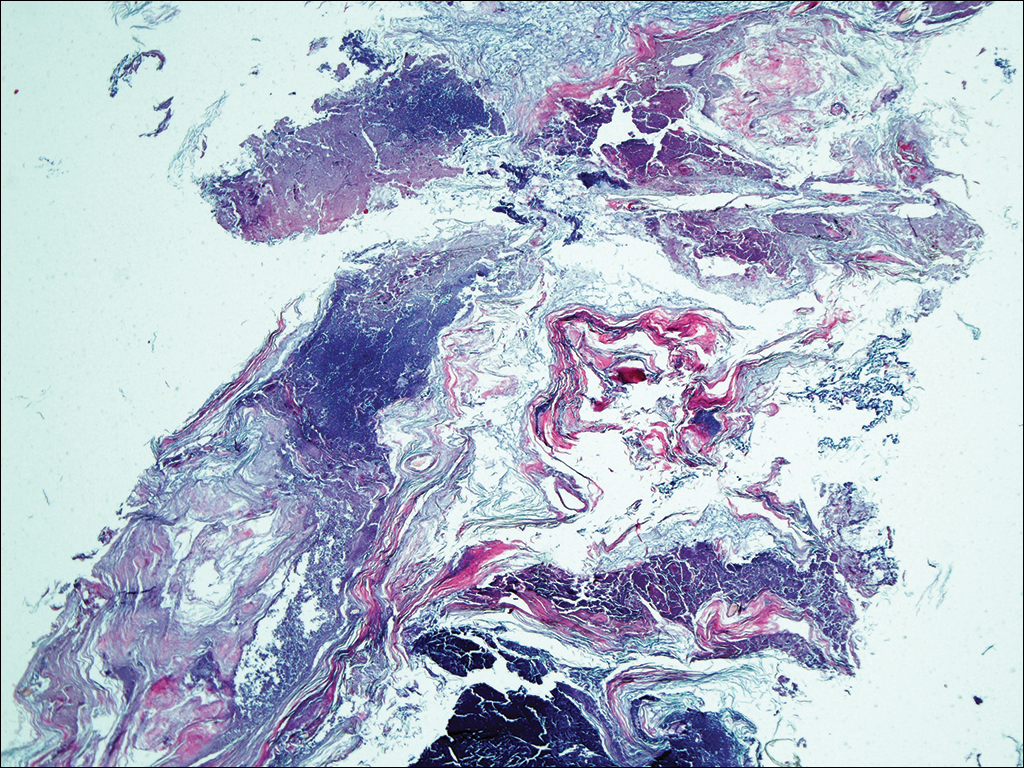

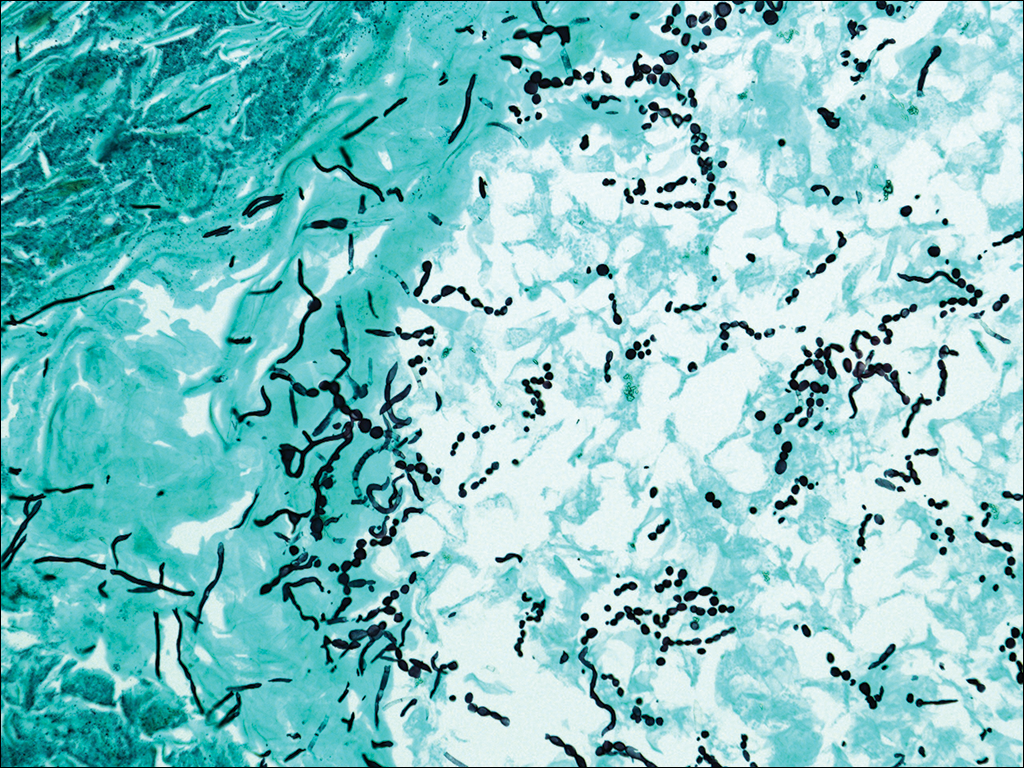

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.

Favus usually is acquired in childhood or adolescence and often persists into adulthood.3 It is transmitted directly by hairs, infected keratinocytes, and fomites. Child-to-child transmission is much less common than other forms of TC.4 The responsible organism is almost always Trichophyton schoenleinii, with rare cases of Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var quinckeanum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum having been reported.2,5,6 This anthropophilic dermatophyte infects only humans, is capable of surviving in the same dwelling space for generations, and is believed to require prolonged exposure for transmission. Trichophyton schoenleinii was the predominant infectious cause of TC in eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but its incidence has dramatically declined in the last 50 years.7 A survey conducted in 1997 and published in 2001 of TC that was culture-positive for T schoenleinii in 19 European countries found only 3 cases among 3671 isolates (0.08%).8 Between 1980 and 2005, no cases were reported in the British Isles.9 Currently, favus generally is found in impoverished geographic regions with poor hygiene, malnutrition, and limited access to health care; however, endemic foci in Kentucky, Quebec, and Montreal have been reported in North America.10 Although favus rarely resolves spontaneously, T schoenleinii was eradicated in most of the world with the introduction of griseofulvin in 1958.7 Terbinafine and itraconazole are currently the drugs of choice for therapy.10

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection in children, with 1 in 20 US children displaying evidence of overt infection.11 Infection in adults is rare and most affected patients typically display serious illnesses with concomitant immune compromise.12 Only 3% to 5% of cases arise in patients older than 20 years.13 Adult hair appears to be relatively resistant to dermatophyte infection, probably from the fungistatic properties of long-chain fatty acids found in sebum.13 Tinea capitis in adults usually occurs in postmenopausal women, presumably from involution of sebaceous glands associated with declining estrogen levels. Patients typically exhibit erythematous scaly patches with central clearing, alopecia, varying degrees of inflammation, and few pustules, though exudative and heavily inflammatory lesions also have been described.14

In the current case, TC was not raised in the differential diagnosis. Regardless, given that scaly red patches and papules of the scalp may represent a dermatophyte infection in this patient population, clinicians are encouraged to consider this possibility. Transmission is by direct human-to-human contact and contact with objects containing fomites including brushes, combs, bedding, clothing, toys, furniture, and telephones.15 It is frequently spread among family members and classmates.16

Prior to World War II, most cases of TC in the United States were due to M canis, with Microsporum audouinii becoming more prevalent until the 1960s and 1970s when Trichophyton tonsurans began surging in incidence.12,17 Currently, the latter organism is responsible for more than 95% of TC cases in the United States.18Microsporum canis is the main causative species in Europe but varies widely by country. In the Middle East and Africa, T violaceum is responsible for many infections.

Trichophyton rubrum–associated TC appears to be a rare occurrence. A global study in 1995 noted that less than 1% of TC cases were due to T rubrum infection, most having been described in emerging nations.12 A meta-analysis of 9 studies from developed countries found only 9 of 10,145 cases of TC with a culture positive for T rubrum.14 In adults, infected patients typically exhibit either evidence of a concomitant fungal infection of the skin and/or nails or health conditions with impaired immunity, whereas in children, interfamilial spread appears more common.11

- Sabouraud R. Les favus atypiques, clinique. Paris. 1909;4:296-299.

- Olkit M. Favus of the scalp: an overview and update. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:143-154.

- Elewski BE. Tinea capitis: a current perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:1-20.

- Aly R, Hay RJ, del Palacio A, et al. Epidemiology of tinea capitis. Med Mycol. 2000;38(suppl 1):183-188.

- Joly J, Delage G, Auger P, et al. Favus: twenty indigenous cases in the province of Quebec. Arch Dermatol. 1978;114:1647-1648.

- Garcia-Sanchez MS, Pereira M, Pereira MM, et al. Favus due to Trichophyton mentagrophytes var. quinckeanum. Dermatology. 1997;194:177-179.

- Seebacher C, Bouchara JP, Mignon B. Updates on the epidemiology of dermatophyte infections. Mycopathologia. 2008;166:335-352.

- Hay RJ, Robles W, Midgley MK, et al. Tinea capitis in Europe: new perspective on an old problem. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:229-233.

- Borman AM, Campbell CK, Fraser M, et al. Analysis of the dermatophyte species isolated in the British Isles between 1980 and 2005 and review of worldwide dermatophyte trends over the last three decades. Med Mycol. 2007;45:131-141.

- Rippon JW. Dermatophytosis and dermatomycosis. In: Rippon JW. Medical Mycology: The Pathogenic Fungi and the Pathogenic Actinomycetes. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1988:197-199.

- Abdel-Rahman SM, Penny J, Alander SW. Trichophyton rubrum tinea capitis in a young child. Ped Dermatol. 2004;21:63-65.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Brocker EB. Frequency of Trichophyton rubrum in tinea capitis. Mycoses. 1995;38:1-7.

- Ziemer A, Kohl K, Schroder G. Trichophyton rubrum induced inflammatory tinea capitis in a 63-year-old man. Mycoses. 2005;48:76-79.

- Anstey A, Lucke TW, Philpot C. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:113-115.

- Schwinn A, Ebert J, Muller I, et al. Trichophyton rubrum as the causative agent of tinea capitis in three children. Mycoses. 1995;38:9-11.

- Chang SE, Kang SK, Choi JH, et al. Tinea capitis due to Trichophyton rubrum in a neonate. Ped Dermatol. 2002;19:356-358.

- Stiller MJ, Rosenthal SA, Weinstein AS. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a 67-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:257-258.

- Foster KW, Ghannoum MA, Elewski BE. Epidemiologic surveillance of cutaneous fungal infection in the United States from 1999 to 2002. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:748-752.

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.

Favus usually is acquired in childhood or adolescence and often persists into adulthood.3 It is transmitted directly by hairs, infected keratinocytes, and fomites. Child-to-child transmission is much less common than other forms of TC.4 The responsible organism is almost always Trichophyton schoenleinii, with rare cases of Trichophyton violaceum, Trichophyton verrucosum, Trichophyton mentagrophytes var quinckeanum, Microsporum canis, and Microsporum gypseum having been reported.2,5,6 This anthropophilic dermatophyte infects only humans, is capable of surviving in the same dwelling space for generations, and is believed to require prolonged exposure for transmission. Trichophyton schoenleinii was the predominant infectious cause of TC in eastern Europe in the 19th and early 20th centuries, but its incidence has dramatically declined in the last 50 years.7 A survey conducted in 1997 and published in 2001 of TC that was culture-positive for T schoenleinii in 19 European countries found only 3 cases among 3671 isolates (0.08%).8 Between 1980 and 2005, no cases were reported in the British Isles.9 Currently, favus generally is found in impoverished geographic regions with poor hygiene, malnutrition, and limited access to health care; however, endemic foci in Kentucky, Quebec, and Montreal have been reported in North America.10 Although favus rarely resolves spontaneously, T schoenleinii was eradicated in most of the world with the introduction of griseofulvin in 1958.7 Terbinafine and itraconazole are currently the drugs of choice for therapy.10

Tinea capitis is the most common fungal infection in children, with 1 in 20 US children displaying evidence of overt infection.11 Infection in adults is rare and most affected patients typically display serious illnesses with concomitant immune compromise.12 Only 3% to 5% of cases arise in patients older than 20 years.13 Adult hair appears to be relatively resistant to dermatophyte infection, probably from the fungistatic properties of long-chain fatty acids found in sebum.13 Tinea capitis in adults usually occurs in postmenopausal women, presumably from involution of sebaceous glands associated with declining estrogen levels. Patients typically exhibit erythematous scaly patches with central clearing, alopecia, varying degrees of inflammation, and few pustules, though exudative and heavily inflammatory lesions also have been described.14

In the current case, TC was not raised in the differential diagnosis. Regardless, given that scaly red patches and papules of the scalp may represent a dermatophyte infection in this patient population, clinicians are encouraged to consider this possibility. Transmission is by direct human-to-human contact and contact with objects containing fomites including brushes, combs, bedding, clothing, toys, furniture, and telephones.15 It is frequently spread among family members and classmates.16

Prior to World War II, most cases of TC in the United States were due to M canis, with Microsporum audouinii becoming more prevalent until the 1960s and 1970s when Trichophyton tonsurans began surging in incidence.12,17 Currently, the latter organism is responsible for more than 95% of TC cases in the United States.18Microsporum canis is the main causative species in Europe but varies widely by country. In the Middle East and Africa, T violaceum is responsible for many infections.

Trichophyton rubrum–associated TC appears to be a rare occurrence. A global study in 1995 noted that less than 1% of TC cases were due to T rubrum infection, most having been described in emerging nations.12 A meta-analysis of 9 studies from developed countries found only 9 of 10,145 cases of TC with a culture positive for T rubrum.14 In adults, infected patients typically exhibit either evidence of a concomitant fungal infection of the skin and/or nails or health conditions with impaired immunity, whereas in children, interfamilial spread appears more common.11

In 1909, Sabouraud1 published a report delineating the clinical subsets of a chronic fungal infection of the scalp known as favus. The rarest subset was termed favus papyroide and consisted of a thin, dry, gray, parchmentlike crust up to 5 cm in diameter. Hair shafts were described as piercing the crust, with the underlying skin exhibiting erythema, moisture, and erosions. Children were reported to be affected more often than adults.1 Subsequent descriptions of patients with similar presentations have not appeared in the medical literature. In this case, an elderly woman with tinea capitis (TC) due to Trichophyton rubrum exhibited features of favus papyroide.

Case Report

An 87-year-old woman with a long history of actinic keratoses and nonmelanoma skin cancers presented to our dermatology clinic with numerous growths on the head, neck, and arms. The patient resided in a nursing home and had a history of hypertension, osteoarthritis, and mild to moderate dementia. Physical examination revealed a frail elderly woman in a wheelchair. Numerous actinic keratoses were noted on the arms and face. Examination of the scalp revealed a large, white-gray, palm-sized plaque on the crown (Figure 1) with 2 yellow, quarter-sized, hyperkeratotic nodules on the left temple and left parietal scalp. The differential diagnosis for the nodules on the temple and scalp included squamous cell carcinoma and hyperkeratotic actinic keratosis, and both lesions were biopsied. Histologically, they demonstrated pronounced hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis with numerous infiltrating neutrophils. The stratum malpighii exhibited focal atypia consistent with an actinic keratosis with areas of spongiosis and pustular folliculitis but no evidence of an invasive cutaneous malignancy. Periodic acid–Schiff stains were performed on both specimens and revealed numerous fungal hyphae within the stratum corneum (Figure 2) as well as evidence of a fungal folliculitis.

At a follow-up visit 2 weeks later, a portion of the hyperkeratotic material on the crown of the scalp was lifted free from the skin surface, removed with scissors, and submitted for histologic analysis and culture. The underlying skin exhibited substantial erythema and diffuse alopecia. The specimen consisted entirely of masses of hyperkeratotic and parakeratotic stratum corneum with numerous infiltrating neutrophils, cellular debris, and focal secondary bacterial colonization (Figure 3). Fungal hyphae and spores were readily demonstrated on Gomori methenamine-silver stain (Figure 4). A fungal culture from this material failed to demonstrate growth at 28 days. The organism was molecularly identified as T rubrum using the Sanger sequencing assay. The patient was treated with fluconazole 150 mg once daily for 3 weeks with eventual resolution of the plaque. The patient died approximately 3 months later (unrelated to her scalp infection).

Comment

Favus, or tinea favosa, is a chronic inflammatory dermatophyte infection of the scalp, less commonly involving the skin and nails.2 The classic lesion is termed a scutulum or godet consisting of concave, cup-shaped, yellow crusts typically pierced by a single hair shaft.1 With an increase in size, the scutula may become confluent. Alopecia commonly results and infected patients may exude a “cheesy” or “mousy” odor from the lesions.3 Sabouraud1 delineated 3 clinical presentations of favus: (1) favus pityroide, the most common type consisting of a seborrheic dermatitis–like picture and scutula; (2) favus impetigoide, exhibiting honey-colored crusts reminiscent of impetigo but without appreciable scutula; and (3) favus papyroide, the rarest variant, demonstrating a dry, gray, parchmentlike crust pierced by hair shafts overlying an eroded erythematous scalp.