User login

Short-course calcipotriol plus 5-FU for AKs: potential major public health impact

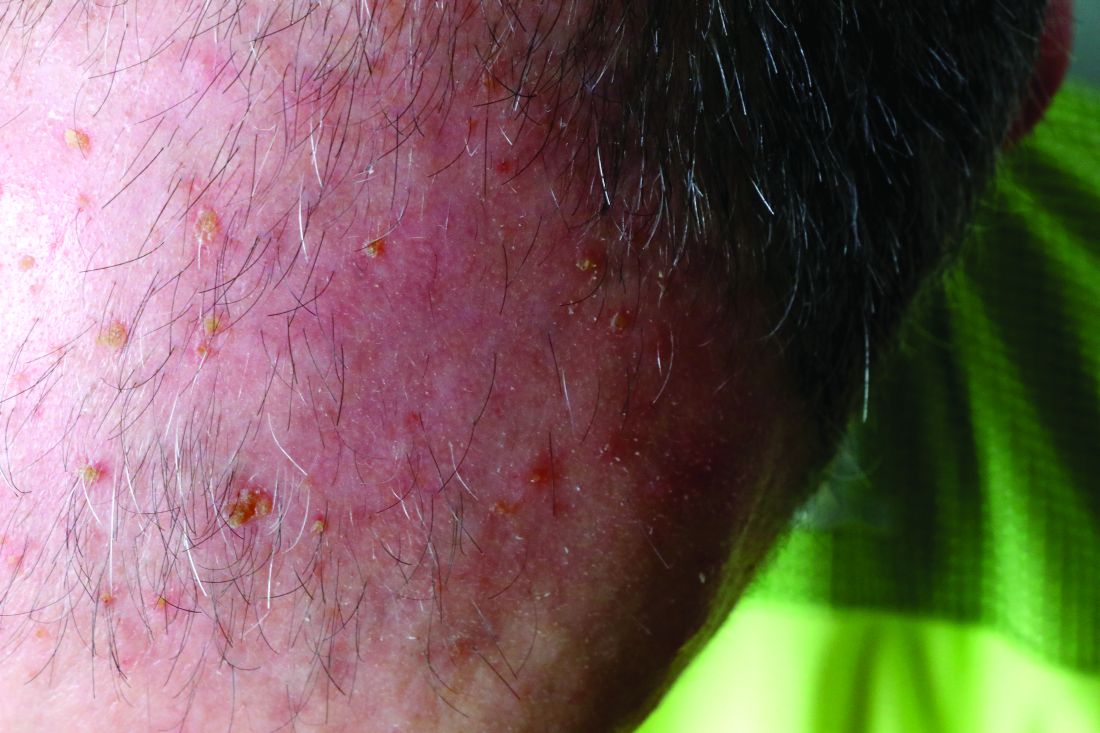

LAHAINA, HAWAII – The most intriguing recent development in the treatment of actinic keratosis is a study in which a short-course of topical field therapy with , with a resultant markedly reduced risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma within the next 3 years, Kishwer S. Nehal, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The annual cost of treating actinic keratoses (AKs) exceeds $1 billion in the United States, so the billion-dollar question in dermatology is, does AK reduction lead to long-term protection against cancer? And this 3-year study by investigators at Washington University in St. Louis and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston suggests the answer may be yes – when topical immunotherapy is utilized to induce robust T cell immunity, said Dr. Nehal, director of Mohs micrographic and dermatologic surgery, and codirector of the multidisciplinary skin cancer management program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The investigators previously conducted a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in which 130 participants with a substantial AK burden received a 4-day course of 0.005% calcipotriol ointment plus 5% 5-FU cream or Vaseline plus 5-FU. The combination therapy proved more effective than the comparator in eliminating AKs at 8 weeks of follow-up. Moreover, tissue analysis pointed to the mechanism of benefit: The combination treatment induced keratinocyte expression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) cytokine, which led to a powerful CD4+ T cell response against AKs.

The researchers’ follow-up study addressed two key questions: Whether this epidermal T cell immunity persists long term, and if it actually achieves a reduced risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) over time. The answers were yes and yes.

Seventy of the original 130 patients were prospectively followed for 3 years. Only 2 of 30 (7%) in the short-course combination therapy group developed SCC in treated areas of the face and scalp, compared with 11 of 40 controls (28%), a statistically significant difference, which constitutes a 79% relative risk reduction. This chemopreventive effect was long lasting at the cellular level, as the combination therapy group still retained measurable T cell immunity in the skin at the 3-year mark. As expected, the topical therapy had no impact on the development of basal cell carcinoma. The question now becomes how long the chemopreventive effect extends beyond 3 years.

“These remarkable findings substantiate the use of immunotherapeutic agents with minimal side effects and high efficacy against precancerous lesions in order to reduce the risk of cancer development and recurrence, which may be broadly applicable to skin and internal malignancies,” the investigators wrote in the study (JCI Insight. 2019 Mar 21;4(6). pii: 125476. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125476). Dr. Nehal said that this study requires confirmation in light of its post hoc design and the relatively small numbers of patients and SCCs. But the potential public health implications are profound, since roughly 40 million Americans have AKs, subclinical AKs are 10 times more common than visible ones, AKs are known precursors for SCC, and high-risk SCC is the cause of roughly 10,000 deaths per year, an underappreciated mortality burden that’s actually comparable to that of melanoma.

While awaiting further studies, this short-course combination therapy also offers the ready appeal of a field therapy without much downtime due to treatment-induced inflammation. In the study, 4 days of combo therapy resulted in moderate inflammation which quickly resolved.

“Does treatment duration and severity affect patient compliance? I would argue that in 2020 it does. People have very active, busy lives and they don’t want a lot of downtime. I can tell you that in Manhattan they want no downtime,” said Dr. Nehal, professor of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Even though a traditional 4-week, twice-daily course of 5% 5-FU cream has been convincingly shown in a recent large randomized Dutch trial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 7;380[10]:935-46) to be the most effective field therapy for eradicating AKs – outperforming in descending order of efficacy at 12 months of follow-up imiquimod (Zyclara), photodynamic therapy, and ingenol mebutate (Picato) – Dr. Nehal finds few takers for 5-FU. People balk at the downtime. Her female patients with a significant AK burden typically opt for photodynamic therapy because of the aesthetic side benefit and shorter downtime, while the men – even those who’ve already had a large SCC – are more likely to prefer a watch-and-wait approach, dealing with an SCC if and when it arises.

“I love the science behind using calcipotriol with 5-FU, but I wish it was more friendly to dermatologists,” said fellow panelist Paul Nghiem, MD, PhD. “Of all the things we should have a combination product for, the pharmaceutical industry should really prepare a [calcipotriol/5-FU] cream and market it with the improved efficacy data.”

He added that he has no use for the conventional 2- to 4-week, twice-daily 5-FU regimens employed by many dermatologists.

“I don’t understand this need to feel like you’ve got to treat patients until they look like they’ve fallen off a motorcycle at 50 mph. I just can’t see that,” said Dr. Nghiem, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Instead, he routinely utilizes the nearly 3-decade-old Pearlman technique of weekly pulsed dosing of topical 5-FU (J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Oct;25[4]:665-7).

“I almost never even ask my patients, ‘Are you OK with having a bunch of downtime?’ I just say, ‘Treat with the 5-FU until you get some erythema, until you’re bothered by it, and then stop for a while,’ ” he explained. “I’ve treated many patients with that technique over the years. It might not be quite as effective, but I hardly have to do any treatment with liquid nitrogen.”

Session chair Ashfaq A. Marghoob, MD, is of a similar mind.

“I also don’t go to the point that you’re fire engine red. Once the irritation sets in, we stop,” said Dr. Marghoob, director of clinical dermatology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Skin Cancer Center Hauppauge (New York).

Neither Dr. Nehal nor Dr. Nghiem has used short-course calcipotriol plus 5-FU therapy. When they polled the large audience as to who has, only a few hands went up.

“I feel like residents who are keeping up with the literature are using it,” Dr. Nehal observed. “My fellows say, ‘Yup, that’s what we’re doing,’ but I’m not using it.”

“I use it,” volunteered fellow panelist Trilokraj Tejasvi, MBBS. “I was educated by one of my residents, and now I use it all the time, especially in my VA population. I’ve been using it for a year. Things get red, but it clears fast,” said Dr. Tejasvi, director of the cutaneous lymphoma program and director of teledermatology services at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and chief of the dermatology service at Ann Arbor Veteran Affairs Hospital.

Dr. Nehal reported having no conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – The most intriguing recent development in the treatment of actinic keratosis is a study in which a short-course of topical field therapy with , with a resultant markedly reduced risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma within the next 3 years, Kishwer S. Nehal, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The annual cost of treating actinic keratoses (AKs) exceeds $1 billion in the United States, so the billion-dollar question in dermatology is, does AK reduction lead to long-term protection against cancer? And this 3-year study by investigators at Washington University in St. Louis and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston suggests the answer may be yes – when topical immunotherapy is utilized to induce robust T cell immunity, said Dr. Nehal, director of Mohs micrographic and dermatologic surgery, and codirector of the multidisciplinary skin cancer management program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The investigators previously conducted a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in which 130 participants with a substantial AK burden received a 4-day course of 0.005% calcipotriol ointment plus 5% 5-FU cream or Vaseline plus 5-FU. The combination therapy proved more effective than the comparator in eliminating AKs at 8 weeks of follow-up. Moreover, tissue analysis pointed to the mechanism of benefit: The combination treatment induced keratinocyte expression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) cytokine, which led to a powerful CD4+ T cell response against AKs.

The researchers’ follow-up study addressed two key questions: Whether this epidermal T cell immunity persists long term, and if it actually achieves a reduced risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) over time. The answers were yes and yes.

Seventy of the original 130 patients were prospectively followed for 3 years. Only 2 of 30 (7%) in the short-course combination therapy group developed SCC in treated areas of the face and scalp, compared with 11 of 40 controls (28%), a statistically significant difference, which constitutes a 79% relative risk reduction. This chemopreventive effect was long lasting at the cellular level, as the combination therapy group still retained measurable T cell immunity in the skin at the 3-year mark. As expected, the topical therapy had no impact on the development of basal cell carcinoma. The question now becomes how long the chemopreventive effect extends beyond 3 years.

“These remarkable findings substantiate the use of immunotherapeutic agents with minimal side effects and high efficacy against precancerous lesions in order to reduce the risk of cancer development and recurrence, which may be broadly applicable to skin and internal malignancies,” the investigators wrote in the study (JCI Insight. 2019 Mar 21;4(6). pii: 125476. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125476). Dr. Nehal said that this study requires confirmation in light of its post hoc design and the relatively small numbers of patients and SCCs. But the potential public health implications are profound, since roughly 40 million Americans have AKs, subclinical AKs are 10 times more common than visible ones, AKs are known precursors for SCC, and high-risk SCC is the cause of roughly 10,000 deaths per year, an underappreciated mortality burden that’s actually comparable to that of melanoma.

While awaiting further studies, this short-course combination therapy also offers the ready appeal of a field therapy without much downtime due to treatment-induced inflammation. In the study, 4 days of combo therapy resulted in moderate inflammation which quickly resolved.

“Does treatment duration and severity affect patient compliance? I would argue that in 2020 it does. People have very active, busy lives and they don’t want a lot of downtime. I can tell you that in Manhattan they want no downtime,” said Dr. Nehal, professor of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Even though a traditional 4-week, twice-daily course of 5% 5-FU cream has been convincingly shown in a recent large randomized Dutch trial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 7;380[10]:935-46) to be the most effective field therapy for eradicating AKs – outperforming in descending order of efficacy at 12 months of follow-up imiquimod (Zyclara), photodynamic therapy, and ingenol mebutate (Picato) – Dr. Nehal finds few takers for 5-FU. People balk at the downtime. Her female patients with a significant AK burden typically opt for photodynamic therapy because of the aesthetic side benefit and shorter downtime, while the men – even those who’ve already had a large SCC – are more likely to prefer a watch-and-wait approach, dealing with an SCC if and when it arises.

“I love the science behind using calcipotriol with 5-FU, but I wish it was more friendly to dermatologists,” said fellow panelist Paul Nghiem, MD, PhD. “Of all the things we should have a combination product for, the pharmaceutical industry should really prepare a [calcipotriol/5-FU] cream and market it with the improved efficacy data.”

He added that he has no use for the conventional 2- to 4-week, twice-daily 5-FU regimens employed by many dermatologists.

“I don’t understand this need to feel like you’ve got to treat patients until they look like they’ve fallen off a motorcycle at 50 mph. I just can’t see that,” said Dr. Nghiem, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Instead, he routinely utilizes the nearly 3-decade-old Pearlman technique of weekly pulsed dosing of topical 5-FU (J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Oct;25[4]:665-7).

“I almost never even ask my patients, ‘Are you OK with having a bunch of downtime?’ I just say, ‘Treat with the 5-FU until you get some erythema, until you’re bothered by it, and then stop for a while,’ ” he explained. “I’ve treated many patients with that technique over the years. It might not be quite as effective, but I hardly have to do any treatment with liquid nitrogen.”

Session chair Ashfaq A. Marghoob, MD, is of a similar mind.

“I also don’t go to the point that you’re fire engine red. Once the irritation sets in, we stop,” said Dr. Marghoob, director of clinical dermatology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Skin Cancer Center Hauppauge (New York).

Neither Dr. Nehal nor Dr. Nghiem has used short-course calcipotriol plus 5-FU therapy. When they polled the large audience as to who has, only a few hands went up.

“I feel like residents who are keeping up with the literature are using it,” Dr. Nehal observed. “My fellows say, ‘Yup, that’s what we’re doing,’ but I’m not using it.”

“I use it,” volunteered fellow panelist Trilokraj Tejasvi, MBBS. “I was educated by one of my residents, and now I use it all the time, especially in my VA population. I’ve been using it for a year. Things get red, but it clears fast,” said Dr. Tejasvi, director of the cutaneous lymphoma program and director of teledermatology services at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and chief of the dermatology service at Ann Arbor Veteran Affairs Hospital.

Dr. Nehal reported having no conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – The most intriguing recent development in the treatment of actinic keratosis is a study in which a short-course of topical field therapy with , with a resultant markedly reduced risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma within the next 3 years, Kishwer S. Nehal, MD, said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

The annual cost of treating actinic keratoses (AKs) exceeds $1 billion in the United States, so the billion-dollar question in dermatology is, does AK reduction lead to long-term protection against cancer? And this 3-year study by investigators at Washington University in St. Louis and Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston suggests the answer may be yes – when topical immunotherapy is utilized to induce robust T cell immunity, said Dr. Nehal, director of Mohs micrographic and dermatologic surgery, and codirector of the multidisciplinary skin cancer management program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center in New York.

The investigators previously conducted a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in which 130 participants with a substantial AK burden received a 4-day course of 0.005% calcipotriol ointment plus 5% 5-FU cream or Vaseline plus 5-FU. The combination therapy proved more effective than the comparator in eliminating AKs at 8 weeks of follow-up. Moreover, tissue analysis pointed to the mechanism of benefit: The combination treatment induced keratinocyte expression of thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) cytokine, which led to a powerful CD4+ T cell response against AKs.

The researchers’ follow-up study addressed two key questions: Whether this epidermal T cell immunity persists long term, and if it actually achieves a reduced risk of squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) over time. The answers were yes and yes.

Seventy of the original 130 patients were prospectively followed for 3 years. Only 2 of 30 (7%) in the short-course combination therapy group developed SCC in treated areas of the face and scalp, compared with 11 of 40 controls (28%), a statistically significant difference, which constitutes a 79% relative risk reduction. This chemopreventive effect was long lasting at the cellular level, as the combination therapy group still retained measurable T cell immunity in the skin at the 3-year mark. As expected, the topical therapy had no impact on the development of basal cell carcinoma. The question now becomes how long the chemopreventive effect extends beyond 3 years.

“These remarkable findings substantiate the use of immunotherapeutic agents with minimal side effects and high efficacy against precancerous lesions in order to reduce the risk of cancer development and recurrence, which may be broadly applicable to skin and internal malignancies,” the investigators wrote in the study (JCI Insight. 2019 Mar 21;4(6). pii: 125476. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.125476). Dr. Nehal said that this study requires confirmation in light of its post hoc design and the relatively small numbers of patients and SCCs. But the potential public health implications are profound, since roughly 40 million Americans have AKs, subclinical AKs are 10 times more common than visible ones, AKs are known precursors for SCC, and high-risk SCC is the cause of roughly 10,000 deaths per year, an underappreciated mortality burden that’s actually comparable to that of melanoma.

While awaiting further studies, this short-course combination therapy also offers the ready appeal of a field therapy without much downtime due to treatment-induced inflammation. In the study, 4 days of combo therapy resulted in moderate inflammation which quickly resolved.

“Does treatment duration and severity affect patient compliance? I would argue that in 2020 it does. People have very active, busy lives and they don’t want a lot of downtime. I can tell you that in Manhattan they want no downtime,” said Dr. Nehal, professor of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medicine, New York.

Even though a traditional 4-week, twice-daily course of 5% 5-FU cream has been convincingly shown in a recent large randomized Dutch trial (N Engl J Med. 2019 Mar 7;380[10]:935-46) to be the most effective field therapy for eradicating AKs – outperforming in descending order of efficacy at 12 months of follow-up imiquimod (Zyclara), photodynamic therapy, and ingenol mebutate (Picato) – Dr. Nehal finds few takers for 5-FU. People balk at the downtime. Her female patients with a significant AK burden typically opt for photodynamic therapy because of the aesthetic side benefit and shorter downtime, while the men – even those who’ve already had a large SCC – are more likely to prefer a watch-and-wait approach, dealing with an SCC if and when it arises.

“I love the science behind using calcipotriol with 5-FU, but I wish it was more friendly to dermatologists,” said fellow panelist Paul Nghiem, MD, PhD. “Of all the things we should have a combination product for, the pharmaceutical industry should really prepare a [calcipotriol/5-FU] cream and market it with the improved efficacy data.”

He added that he has no use for the conventional 2- to 4-week, twice-daily 5-FU regimens employed by many dermatologists.

“I don’t understand this need to feel like you’ve got to treat patients until they look like they’ve fallen off a motorcycle at 50 mph. I just can’t see that,” said Dr. Nghiem, professor and chair of dermatology at the University of Washington, Seattle.

Instead, he routinely utilizes the nearly 3-decade-old Pearlman technique of weekly pulsed dosing of topical 5-FU (J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991 Oct;25[4]:665-7).

“I almost never even ask my patients, ‘Are you OK with having a bunch of downtime?’ I just say, ‘Treat with the 5-FU until you get some erythema, until you’re bothered by it, and then stop for a while,’ ” he explained. “I’ve treated many patients with that technique over the years. It might not be quite as effective, but I hardly have to do any treatment with liquid nitrogen.”

Session chair Ashfaq A. Marghoob, MD, is of a similar mind.

“I also don’t go to the point that you’re fire engine red. Once the irritation sets in, we stop,” said Dr. Marghoob, director of clinical dermatology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Skin Cancer Center Hauppauge (New York).

Neither Dr. Nehal nor Dr. Nghiem has used short-course calcipotriol plus 5-FU therapy. When they polled the large audience as to who has, only a few hands went up.

“I feel like residents who are keeping up with the literature are using it,” Dr. Nehal observed. “My fellows say, ‘Yup, that’s what we’re doing,’ but I’m not using it.”

“I use it,” volunteered fellow panelist Trilokraj Tejasvi, MBBS. “I was educated by one of my residents, and now I use it all the time, especially in my VA population. I’ve been using it for a year. Things get red, but it clears fast,” said Dr. Tejasvi, director of the cutaneous lymphoma program and director of teledermatology services at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and chief of the dermatology service at Ann Arbor Veteran Affairs Hospital.

Dr. Nehal reported having no conflicts of interest regarding her presentation.

SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

REPORTING FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

European marketing of Picato suspended while skin cancer risk reviewed

As a precaution, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that patients stop using ingenol mebutate (Picato) while the agency continues to review the safety of the topical treatment, which is indicated for the treatment of actinic keratosis in Europe and the United States.

No such action has been taken in the United States.

The EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) is reviewing data on skin cancer in patients treated with ingenol mebutate. In a trial comparing Picato and imiquimod, skin cancer was more common in the areas treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod, the statement said.

“While uncertainties remain, the EMA said in a Jan. 17 news release. “The PRAC has therefore recommended suspending the medicine’s marketing authorization as a precaution and noted that alternative treatments are available.”

FDA is looking at the situation

LEO Pharma, the company that markets Picato, announced on Jan. 9 that it was initiating voluntary withdrawal of marketing authorization and possible voluntary withdrawal of Picato in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). The statement says, however, that “LEO Pharma has carefully reviewed the information received from PRAC, and the company disagrees with the ongoing assessment of PRAC.” There are “no additional safety data and it is LEO Pharma’s position that there is no evidence of a causal relationship or plausible mechanism hypothesis between the use of Picato and the development of skin malignancies.” An update added to the press release on Jan. 17 restates that the company disagrees with the assessment of PRAC.

“This matter does not affect Picato in the U.S., and there are no new developments in the [United States]. Picato continues to be available to patients in the U.S. We remain in dialogue with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about Picato in the EU/EEA,” Rhonda Sciarra, associate director of global external communications for LEO Pharma, said in an email. “We remain committed to ensuring patient safety, rigorous pharmacovigilance monitoring, and transparency,” she added.

The FDA “is gathering data and information to investigate the safety concern related to Picato,” a spokesperson for the FDA told Dermatology News. “We are committed to sharing relevant findings when we have sufficient understanding of the situation and of what actions should be taken,” he added.

Examining the data

The EMA announcement described data about the risk of skin cancer in studies of Picato. A 3-year study in 484 patients found a higher incidence of skin malignancy with ingenol mebutate than with the comparator, imiquimod. In all, 3.3% of patients developed cancer in the ingenol mebutate group, compared with 0.4% in the comparator group.

In an 8-week vehicle-controlled trial in 1,262 patients, there were more skin tumors in patients who received ingenol mebutate than in those in the vehicle arm (1.0% vs. 0.1%).

In addition, according to the EMA statement, in four trials of a related ester that included 1,234 patients, a higher incidence of skin tumors occurred with the related drug, ingenol disoxate, than with a vehicle control (7.7% vs. 2.9%). PRAC considered these data because ingenol disoxate and ingenol mebutate are closely related, the EMA said.

“Health care professionals should stop prescribing Picato and consider different treatment options while authorities review the data,” according to the European agency. “Health care professionals should advise patients to be vigilant for any skin lesions developing and to seek medical advice promptly should any occur,” the statement adds.

Picato has been authorized in the EU since 2012, and the FDA approved Picato the same year. Patients have received about 2.8 million treatment courses in that time, according to the LEO Pharma press release.

As a precaution, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that patients stop using ingenol mebutate (Picato) while the agency continues to review the safety of the topical treatment, which is indicated for the treatment of actinic keratosis in Europe and the United States.

No such action has been taken in the United States.

The EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) is reviewing data on skin cancer in patients treated with ingenol mebutate. In a trial comparing Picato and imiquimod, skin cancer was more common in the areas treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod, the statement said.

“While uncertainties remain, the EMA said in a Jan. 17 news release. “The PRAC has therefore recommended suspending the medicine’s marketing authorization as a precaution and noted that alternative treatments are available.”

FDA is looking at the situation

LEO Pharma, the company that markets Picato, announced on Jan. 9 that it was initiating voluntary withdrawal of marketing authorization and possible voluntary withdrawal of Picato in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). The statement says, however, that “LEO Pharma has carefully reviewed the information received from PRAC, and the company disagrees with the ongoing assessment of PRAC.” There are “no additional safety data and it is LEO Pharma’s position that there is no evidence of a causal relationship or plausible mechanism hypothesis between the use of Picato and the development of skin malignancies.” An update added to the press release on Jan. 17 restates that the company disagrees with the assessment of PRAC.

“This matter does not affect Picato in the U.S., and there are no new developments in the [United States]. Picato continues to be available to patients in the U.S. We remain in dialogue with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about Picato in the EU/EEA,” Rhonda Sciarra, associate director of global external communications for LEO Pharma, said in an email. “We remain committed to ensuring patient safety, rigorous pharmacovigilance monitoring, and transparency,” she added.

The FDA “is gathering data and information to investigate the safety concern related to Picato,” a spokesperson for the FDA told Dermatology News. “We are committed to sharing relevant findings when we have sufficient understanding of the situation and of what actions should be taken,” he added.

Examining the data

The EMA announcement described data about the risk of skin cancer in studies of Picato. A 3-year study in 484 patients found a higher incidence of skin malignancy with ingenol mebutate than with the comparator, imiquimod. In all, 3.3% of patients developed cancer in the ingenol mebutate group, compared with 0.4% in the comparator group.

In an 8-week vehicle-controlled trial in 1,262 patients, there were more skin tumors in patients who received ingenol mebutate than in those in the vehicle arm (1.0% vs. 0.1%).

In addition, according to the EMA statement, in four trials of a related ester that included 1,234 patients, a higher incidence of skin tumors occurred with the related drug, ingenol disoxate, than with a vehicle control (7.7% vs. 2.9%). PRAC considered these data because ingenol disoxate and ingenol mebutate are closely related, the EMA said.

“Health care professionals should stop prescribing Picato and consider different treatment options while authorities review the data,” according to the European agency. “Health care professionals should advise patients to be vigilant for any skin lesions developing and to seek medical advice promptly should any occur,” the statement adds.

Picato has been authorized in the EU since 2012, and the FDA approved Picato the same year. Patients have received about 2.8 million treatment courses in that time, according to the LEO Pharma press release.

As a precaution, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended that patients stop using ingenol mebutate (Picato) while the agency continues to review the safety of the topical treatment, which is indicated for the treatment of actinic keratosis in Europe and the United States.

No such action has been taken in the United States.

The EMA’s Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) is reviewing data on skin cancer in patients treated with ingenol mebutate. In a trial comparing Picato and imiquimod, skin cancer was more common in the areas treated with Picato than in areas treated with imiquimod, the statement said.

“While uncertainties remain, the EMA said in a Jan. 17 news release. “The PRAC has therefore recommended suspending the medicine’s marketing authorization as a precaution and noted that alternative treatments are available.”

FDA is looking at the situation

LEO Pharma, the company that markets Picato, announced on Jan. 9 that it was initiating voluntary withdrawal of marketing authorization and possible voluntary withdrawal of Picato in the European Union (EU) and European Economic Area (EEA). The statement says, however, that “LEO Pharma has carefully reviewed the information received from PRAC, and the company disagrees with the ongoing assessment of PRAC.” There are “no additional safety data and it is LEO Pharma’s position that there is no evidence of a causal relationship or plausible mechanism hypothesis between the use of Picato and the development of skin malignancies.” An update added to the press release on Jan. 17 restates that the company disagrees with the assessment of PRAC.

“This matter does not affect Picato in the U.S., and there are no new developments in the [United States]. Picato continues to be available to patients in the U.S. We remain in dialogue with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about Picato in the EU/EEA,” Rhonda Sciarra, associate director of global external communications for LEO Pharma, said in an email. “We remain committed to ensuring patient safety, rigorous pharmacovigilance monitoring, and transparency,” she added.

The FDA “is gathering data and information to investigate the safety concern related to Picato,” a spokesperson for the FDA told Dermatology News. “We are committed to sharing relevant findings when we have sufficient understanding of the situation and of what actions should be taken,” he added.

Examining the data

The EMA announcement described data about the risk of skin cancer in studies of Picato. A 3-year study in 484 patients found a higher incidence of skin malignancy with ingenol mebutate than with the comparator, imiquimod. In all, 3.3% of patients developed cancer in the ingenol mebutate group, compared with 0.4% in the comparator group.

In an 8-week vehicle-controlled trial in 1,262 patients, there were more skin tumors in patients who received ingenol mebutate than in those in the vehicle arm (1.0% vs. 0.1%).

In addition, according to the EMA statement, in four trials of a related ester that included 1,234 patients, a higher incidence of skin tumors occurred with the related drug, ingenol disoxate, than with a vehicle control (7.7% vs. 2.9%). PRAC considered these data because ingenol disoxate and ingenol mebutate are closely related, the EMA said.

“Health care professionals should stop prescribing Picato and consider different treatment options while authorities review the data,” according to the European agency. “Health care professionals should advise patients to be vigilant for any skin lesions developing and to seek medical advice promptly should any occur,” the statement adds.

Picato has been authorized in the EU since 2012, and the FDA approved Picato the same year. Patients have received about 2.8 million treatment courses in that time, according to the LEO Pharma press release.

Treating AKs with PDT, other options

SEATTLE – While David Pariser, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

“My personal view is that, no matter how good other treatments are eventually going to be, we’re never going to give that up,” Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said at the meeting, jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

During the presentation, he emphasized that it isn’t always clear which actinic keratosis (AK) should be treated and which can be left alone, since most AKs don’t progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “We know that most squamous cell carcinomas arise near AKs, and many of them have histologic evidence” of AK/SCC continuum at the periphery, he said. Sun protection reduces the incidence of AKs and the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer, “so it’s a logical conclusion that treating AKs reduces the development of SCCs, but there are no data to show that.”

Generally, treatment decisions are made based on the presence of symptoms, location, or appearance; if the area is irritated; or there is a progressive or unusual appearance, especially if hyperkeratotic. Physician or patient concerns about cancer can prompt treatment, as should a history of multiple skin cancers or the presence of immunosuppression, he said.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, surgery, topical agents, and photodynamic therapy (PDT); Dr. Pariser focused on the latter because it is a special interest of his.

Field cancerization is based on the idea that a broad area of cells may be at risk for developing into SCC, rather than just individual AKs. Treatment with methyl 5-aminolevulinate (MAL) can reveal the extent of a problem. In some patients, “you can see a lot of fluorescence in areas that look reasonably clinically normal. So this is a piece of evidence of this field cancerization, that maybe we shouldn’t be treating individual AKs, but larger areas,” Dr. Pariser said.

With PDT, there has been some debate about how long to leave the photosensitizer on the skin before applying the light. The longer it remains, the more it spreads to nerves, which can lead to pain during the procedure. A clinical trial comparing 1-, 2-, and 3-hour wait times showed no difference in efficacy. “So 1 hour is what I do for AKs, that’s it,” Dr. Pariser said.

There are two Food and Drug Administration–approved PDT systems, a blue-light system combined with aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and a newer red-light system combined with a nanoemulsion of ALA 7.8% and a proprietary 635-nm red LED light. The nanoemulsion has the theoretical advantage in that it can penetrate more deeply into the epidermis, though this isn’t really an issue when treating AKs, according to Dr. Pariser.

A study comparing nanoemulsion of ALA, compared with a MAL cream, found the nanoemulsion to be superior in achieving complete clearance of all lesions at 12 weeks (78.2% vs. 64.2%; P less than .05). Both treatments achieved best efficacy with LED lamps, and the proprietary red light may reduce pain by allowing use of lower light intensity (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan; 166[1]:137-46).

Another study, Dr. Pariser said, looked at whether occlusion during drug incubation improves outcomes of blue light ALA-PDT (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11[12]:1483-9). Patients underwent split occlusion on the upper extremities before undergoing blue-light treatment. The median clearance rate of AKs at 8 weeks was higher with occlusion, compared with the nonoccluded areas (75% vs. 47%; P = .006), and at 12 weeks, after a second treatment (89% vs. 70%; P = .00029). There was a higher efficacy with a 3-hour incubation period, compared with studies using a 2-hour incubation period.

Application of heat can also boost success rates by increasing the synthesis of the photoactive agent, Dr. Pariser said. One study found that a simple heating pad applied to the area treated with ALA-PDT and blue light led to an 88% reduction in lesions at 8 and 24 weeks, compared with a reduction of 71% at 8 weeks and 68% at 24 weeks without heat (P less than .0001). “So if you want to give PDT a little extra oomph, add occlusion and heat,” he commented.

He also pointed out the availability of a new 4% 5-fluorouracil cream that contains peanut oil, which has similar efficacy to 5% 5-fluorouracil cream but has been associated with less pruritus, stinging/burning, edema, crusting, scaling/dryness, erosion, and erythema (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Oct 1;15[10]: 1218-24).

Dr. Pariser is an investigator and consultant for DUSA/Sun Pharma, Photocure, LEO Pharma, and Biofrontera. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – While David Pariser, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

“My personal view is that, no matter how good other treatments are eventually going to be, we’re never going to give that up,” Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said at the meeting, jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

During the presentation, he emphasized that it isn’t always clear which actinic keratosis (AK) should be treated and which can be left alone, since most AKs don’t progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “We know that most squamous cell carcinomas arise near AKs, and many of them have histologic evidence” of AK/SCC continuum at the periphery, he said. Sun protection reduces the incidence of AKs and the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer, “so it’s a logical conclusion that treating AKs reduces the development of SCCs, but there are no data to show that.”

Generally, treatment decisions are made based on the presence of symptoms, location, or appearance; if the area is irritated; or there is a progressive or unusual appearance, especially if hyperkeratotic. Physician or patient concerns about cancer can prompt treatment, as should a history of multiple skin cancers or the presence of immunosuppression, he said.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, surgery, topical agents, and photodynamic therapy (PDT); Dr. Pariser focused on the latter because it is a special interest of his.

Field cancerization is based on the idea that a broad area of cells may be at risk for developing into SCC, rather than just individual AKs. Treatment with methyl 5-aminolevulinate (MAL) can reveal the extent of a problem. In some patients, “you can see a lot of fluorescence in areas that look reasonably clinically normal. So this is a piece of evidence of this field cancerization, that maybe we shouldn’t be treating individual AKs, but larger areas,” Dr. Pariser said.

With PDT, there has been some debate about how long to leave the photosensitizer on the skin before applying the light. The longer it remains, the more it spreads to nerves, which can lead to pain during the procedure. A clinical trial comparing 1-, 2-, and 3-hour wait times showed no difference in efficacy. “So 1 hour is what I do for AKs, that’s it,” Dr. Pariser said.

There are two Food and Drug Administration–approved PDT systems, a blue-light system combined with aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and a newer red-light system combined with a nanoemulsion of ALA 7.8% and a proprietary 635-nm red LED light. The nanoemulsion has the theoretical advantage in that it can penetrate more deeply into the epidermis, though this isn’t really an issue when treating AKs, according to Dr. Pariser.

A study comparing nanoemulsion of ALA, compared with a MAL cream, found the nanoemulsion to be superior in achieving complete clearance of all lesions at 12 weeks (78.2% vs. 64.2%; P less than .05). Both treatments achieved best efficacy with LED lamps, and the proprietary red light may reduce pain by allowing use of lower light intensity (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan; 166[1]:137-46).

Another study, Dr. Pariser said, looked at whether occlusion during drug incubation improves outcomes of blue light ALA-PDT (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11[12]:1483-9). Patients underwent split occlusion on the upper extremities before undergoing blue-light treatment. The median clearance rate of AKs at 8 weeks was higher with occlusion, compared with the nonoccluded areas (75% vs. 47%; P = .006), and at 12 weeks, after a second treatment (89% vs. 70%; P = .00029). There was a higher efficacy with a 3-hour incubation period, compared with studies using a 2-hour incubation period.

Application of heat can also boost success rates by increasing the synthesis of the photoactive agent, Dr. Pariser said. One study found that a simple heating pad applied to the area treated with ALA-PDT and blue light led to an 88% reduction in lesions at 8 and 24 weeks, compared with a reduction of 71% at 8 weeks and 68% at 24 weeks without heat (P less than .0001). “So if you want to give PDT a little extra oomph, add occlusion and heat,” he commented.

He also pointed out the availability of a new 4% 5-fluorouracil cream that contains peanut oil, which has similar efficacy to 5% 5-fluorouracil cream but has been associated with less pruritus, stinging/burning, edema, crusting, scaling/dryness, erosion, and erythema (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Oct 1;15[10]: 1218-24).

Dr. Pariser is an investigator and consultant for DUSA/Sun Pharma, Photocure, LEO Pharma, and Biofrontera. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

SEATTLE – While David Pariser, MD, said during a presentation at the annual Coastal Dermatology Symposium.

“My personal view is that, no matter how good other treatments are eventually going to be, we’re never going to give that up,” Dr. Pariser, professor of dermatology at Eastern Virginia Medical School, Norfolk, said at the meeting, jointly presented by the University of Louisville and Global Academy for Medical Education.

During the presentation, he emphasized that it isn’t always clear which actinic keratosis (AK) should be treated and which can be left alone, since most AKs don’t progress to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). “We know that most squamous cell carcinomas arise near AKs, and many of them have histologic evidence” of AK/SCC continuum at the periphery, he said. Sun protection reduces the incidence of AKs and the incidence of nonmelanoma skin cancer, “so it’s a logical conclusion that treating AKs reduces the development of SCCs, but there are no data to show that.”

Generally, treatment decisions are made based on the presence of symptoms, location, or appearance; if the area is irritated; or there is a progressive or unusual appearance, especially if hyperkeratotic. Physician or patient concerns about cancer can prompt treatment, as should a history of multiple skin cancers or the presence of immunosuppression, he said.

Treatment options include cryosurgery, surgery, topical agents, and photodynamic therapy (PDT); Dr. Pariser focused on the latter because it is a special interest of his.

Field cancerization is based on the idea that a broad area of cells may be at risk for developing into SCC, rather than just individual AKs. Treatment with methyl 5-aminolevulinate (MAL) can reveal the extent of a problem. In some patients, “you can see a lot of fluorescence in areas that look reasonably clinically normal. So this is a piece of evidence of this field cancerization, that maybe we shouldn’t be treating individual AKs, but larger areas,” Dr. Pariser said.

With PDT, there has been some debate about how long to leave the photosensitizer on the skin before applying the light. The longer it remains, the more it spreads to nerves, which can lead to pain during the procedure. A clinical trial comparing 1-, 2-, and 3-hour wait times showed no difference in efficacy. “So 1 hour is what I do for AKs, that’s it,” Dr. Pariser said.

There are two Food and Drug Administration–approved PDT systems, a blue-light system combined with aminolevulinic acid (ALA) and a newer red-light system combined with a nanoemulsion of ALA 7.8% and a proprietary 635-nm red LED light. The nanoemulsion has the theoretical advantage in that it can penetrate more deeply into the epidermis, though this isn’t really an issue when treating AKs, according to Dr. Pariser.

A study comparing nanoemulsion of ALA, compared with a MAL cream, found the nanoemulsion to be superior in achieving complete clearance of all lesions at 12 weeks (78.2% vs. 64.2%; P less than .05). Both treatments achieved best efficacy with LED lamps, and the proprietary red light may reduce pain by allowing use of lower light intensity (Br J Dermatol. 2012 Jan; 166[1]:137-46).

Another study, Dr. Pariser said, looked at whether occlusion during drug incubation improves outcomes of blue light ALA-PDT (J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11[12]:1483-9). Patients underwent split occlusion on the upper extremities before undergoing blue-light treatment. The median clearance rate of AKs at 8 weeks was higher with occlusion, compared with the nonoccluded areas (75% vs. 47%; P = .006), and at 12 weeks, after a second treatment (89% vs. 70%; P = .00029). There was a higher efficacy with a 3-hour incubation period, compared with studies using a 2-hour incubation period.

Application of heat can also boost success rates by increasing the synthesis of the photoactive agent, Dr. Pariser said. One study found that a simple heating pad applied to the area treated with ALA-PDT and blue light led to an 88% reduction in lesions at 8 and 24 weeks, compared with a reduction of 71% at 8 weeks and 68% at 24 weeks without heat (P less than .0001). “So if you want to give PDT a little extra oomph, add occlusion and heat,” he commented.

He also pointed out the availability of a new 4% 5-fluorouracil cream that contains peanut oil, which has similar efficacy to 5% 5-fluorouracil cream but has been associated with less pruritus, stinging/burning, edema, crusting, scaling/dryness, erosion, and erythema (J Drugs Dermatol. 2016 Oct 1;15[10]: 1218-24).

Dr. Pariser is an investigator and consultant for DUSA/Sun Pharma, Photocure, LEO Pharma, and Biofrontera. This publication and Global Academy for Medical Education are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM COASTAL DERM

Twitter Chat: Skin Cancer

Join us on Tuesday, October 8, 2019, at 8:00 pm EST on Twitter at #MDedgeChats as we discuss skin cancer, and what’s new in sunscreen, skin of color, and melanoma.

Special guests include physicians with expertise in dermatology and skin cancer, Anthony Rossi, MD (@DrAnthonyRossi), Julie Amthor Croley, MD, 15k followers on IG (@Drskinandsmiles), and Candrice Heath, MD (@DrCandriceHeath). Background information about the chat can be found below.

What will the conversation cover?

Q1: What are the most common types of skin cancer?

Q2: What recent research findings can better inform patients about skin cancer risks?

Q3: What’s the difference between melanoma in fair skin vs. darker skin?

Q4: How does the risk of skin cancer differ in people with darker skin?

Q5: Why should sunscreen be used even in the fall and winter?

Follow us here: @MDedgeDerm | @MDedgeTweets | #MDedgeChats

About Dr. Rossi:

Dr. Anthony Rossi (@DrAnthonyRossi) is a board-certified dermatologist with fellowship training in Mohs micrographic surgery, cosmetic and laser surgery, and advanced cutaneous oncology at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell Medical College program, both in New York. He specializes in skin cancer surgery, cosmetic dermatologic surgery, and laser surgery.

His research includes quality of life in cancer survivors, the use of noninvasive imaging of the skin, and nonsurgical treatments of skin cancer. Additionally, Dr. Rossi is active in dermatologic organizations and advocacy for medicine.

Research and Publications by Dr. Rossi

About Dr. Heath:

Dr. Candrice Heath (@DrCandriceHeath) is Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with fellowship training in pediatric dermatology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Dr. Heath is triple board certified in pediatrics, dermatology, and pediatric dermatology. She specializes in adult and pediatric dermatology, skin of color, acne, and eczema. Dr. Heath also enjoys educating primary care physicians on the front lines of health care and delivering easy to understand information to consumers.

Research and publications by Dr. Heath

Guest host of MDedge podcast: A sunscreen update with Dr. Vincent DeLeo.

About Dr. Croley:

Dr. Julie Amthor Croley (@Drskinandsmiles) also known as “Dr. Skin and Smiles” has 15,000 followers on Instagram, and is a Chief Dermatology Resident at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. She has a special interest in skin cancer and dermatological surgery and hopes to complete a fellowship in Mohs micrographic surgery after residency. In her free time, Dr. Croley enjoys spending time with her husband (an orthopedic surgeon), running and competing in marathons, and spending time on the beach.

Cutaneous melanoma is the most fatal form of skin cancer and is a considerable public health concern in the United States. Early detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from skin cancer. As a result, the American Academy of Dermatology Association supports safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions.

Sunscreen use is an essential component of sun protection. New regulations from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have left consumers concerned about the safety of sunscreens. According to a recent Cutis editorial from Vincent A. DeLeo, MD, “There is no question that, as physicians, we want to ‘first, do no harm,’ so we should all be interested in assuring our patients that our sunscreen recommendations are safe and we support the FDA proposal for additional data.”

Patients with skin of color experience disproportionately higher morbidity and mortality when diagnosed with melanoma. “Poor prognosis in patients with skin of color is multifactorial and may be due to poor use of sun protection, misconceptions about melanoma risk, atypical clinical presentation, impaired access to care, and delay in diagnosis,” according to a recent Cutis article.

Population-based skin cancer screening performed exclusively by dermatologists is not practical. Primary care physicians and other experts in melanoma and public health need to be involved in reducing melanoma mortality.

In this chat, we will provide expert recommendations on the diagnosis of skin cancer, preventive measures, and the latest research discussed among physicians.

- “Doctor, Do I Need a Skin Check?”

- Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in skin of color populations.

- Melanoma in US Hispanics

- Podcast: Sunscreen update from Dr. Vincent DeLeo

- Windshield and UV exposure

- Racial, ethnic minorities often don’t practice sun-protective behaviors.

- Sunscreen regulations and advice for your patients.

Join us on Tuesday, October 8, 2019, at 8:00 pm EST on Twitter at #MDedgeChats as we discuss skin cancer, and what’s new in sunscreen, skin of color, and melanoma.

Special guests include physicians with expertise in dermatology and skin cancer, Anthony Rossi, MD (@DrAnthonyRossi), Julie Amthor Croley, MD, 15k followers on IG (@Drskinandsmiles), and Candrice Heath, MD (@DrCandriceHeath). Background information about the chat can be found below.

What will the conversation cover?

Q1: What are the most common types of skin cancer?

Q2: What recent research findings can better inform patients about skin cancer risks?

Q3: What’s the difference between melanoma in fair skin vs. darker skin?

Q4: How does the risk of skin cancer differ in people with darker skin?

Q5: Why should sunscreen be used even in the fall and winter?

Follow us here: @MDedgeDerm | @MDedgeTweets | #MDedgeChats

About Dr. Rossi:

Dr. Anthony Rossi (@DrAnthonyRossi) is a board-certified dermatologist with fellowship training in Mohs micrographic surgery, cosmetic and laser surgery, and advanced cutaneous oncology at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell Medical College program, both in New York. He specializes in skin cancer surgery, cosmetic dermatologic surgery, and laser surgery.

His research includes quality of life in cancer survivors, the use of noninvasive imaging of the skin, and nonsurgical treatments of skin cancer. Additionally, Dr. Rossi is active in dermatologic organizations and advocacy for medicine.

Research and Publications by Dr. Rossi

About Dr. Heath:

Dr. Candrice Heath (@DrCandriceHeath) is Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with fellowship training in pediatric dermatology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Dr. Heath is triple board certified in pediatrics, dermatology, and pediatric dermatology. She specializes in adult and pediatric dermatology, skin of color, acne, and eczema. Dr. Heath also enjoys educating primary care physicians on the front lines of health care and delivering easy to understand information to consumers.

Research and publications by Dr. Heath

Guest host of MDedge podcast: A sunscreen update with Dr. Vincent DeLeo.

About Dr. Croley:

Dr. Julie Amthor Croley (@Drskinandsmiles) also known as “Dr. Skin and Smiles” has 15,000 followers on Instagram, and is a Chief Dermatology Resident at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. She has a special interest in skin cancer and dermatological surgery and hopes to complete a fellowship in Mohs micrographic surgery after residency. In her free time, Dr. Croley enjoys spending time with her husband (an orthopedic surgeon), running and competing in marathons, and spending time on the beach.

Cutaneous melanoma is the most fatal form of skin cancer and is a considerable public health concern in the United States. Early detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from skin cancer. As a result, the American Academy of Dermatology Association supports safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions.

Sunscreen use is an essential component of sun protection. New regulations from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have left consumers concerned about the safety of sunscreens. According to a recent Cutis editorial from Vincent A. DeLeo, MD, “There is no question that, as physicians, we want to ‘first, do no harm,’ so we should all be interested in assuring our patients that our sunscreen recommendations are safe and we support the FDA proposal for additional data.”

Patients with skin of color experience disproportionately higher morbidity and mortality when diagnosed with melanoma. “Poor prognosis in patients with skin of color is multifactorial and may be due to poor use of sun protection, misconceptions about melanoma risk, atypical clinical presentation, impaired access to care, and delay in diagnosis,” according to a recent Cutis article.

Population-based skin cancer screening performed exclusively by dermatologists is not practical. Primary care physicians and other experts in melanoma and public health need to be involved in reducing melanoma mortality.

In this chat, we will provide expert recommendations on the diagnosis of skin cancer, preventive measures, and the latest research discussed among physicians.

- “Doctor, Do I Need a Skin Check?”

- Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in skin of color populations.

- Melanoma in US Hispanics

- Podcast: Sunscreen update from Dr. Vincent DeLeo

- Windshield and UV exposure

- Racial, ethnic minorities often don’t practice sun-protective behaviors.

- Sunscreen regulations and advice for your patients.

Join us on Tuesday, October 8, 2019, at 8:00 pm EST on Twitter at #MDedgeChats as we discuss skin cancer, and what’s new in sunscreen, skin of color, and melanoma.

Special guests include physicians with expertise in dermatology and skin cancer, Anthony Rossi, MD (@DrAnthonyRossi), Julie Amthor Croley, MD, 15k followers on IG (@Drskinandsmiles), and Candrice Heath, MD (@DrCandriceHeath). Background information about the chat can be found below.

What will the conversation cover?

Q1: What are the most common types of skin cancer?

Q2: What recent research findings can better inform patients about skin cancer risks?

Q3: What’s the difference between melanoma in fair skin vs. darker skin?

Q4: How does the risk of skin cancer differ in people with darker skin?

Q5: Why should sunscreen be used even in the fall and winter?

Follow us here: @MDedgeDerm | @MDedgeTweets | #MDedgeChats

About Dr. Rossi:

Dr. Anthony Rossi (@DrAnthonyRossi) is a board-certified dermatologist with fellowship training in Mohs micrographic surgery, cosmetic and laser surgery, and advanced cutaneous oncology at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and Weill Cornell Medical College program, both in New York. He specializes in skin cancer surgery, cosmetic dermatologic surgery, and laser surgery.

His research includes quality of life in cancer survivors, the use of noninvasive imaging of the skin, and nonsurgical treatments of skin cancer. Additionally, Dr. Rossi is active in dermatologic organizations and advocacy for medicine.

Research and Publications by Dr. Rossi

About Dr. Heath:

Dr. Candrice Heath (@DrCandriceHeath) is Assistant Professor of Dermatology at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania with fellowship training in pediatric dermatology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. Dr. Heath is triple board certified in pediatrics, dermatology, and pediatric dermatology. She specializes in adult and pediatric dermatology, skin of color, acne, and eczema. Dr. Heath also enjoys educating primary care physicians on the front lines of health care and delivering easy to understand information to consumers.

Research and publications by Dr. Heath

Guest host of MDedge podcast: A sunscreen update with Dr. Vincent DeLeo.

About Dr. Croley:

Dr. Julie Amthor Croley (@Drskinandsmiles) also known as “Dr. Skin and Smiles” has 15,000 followers on Instagram, and is a Chief Dermatology Resident at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas. She has a special interest in skin cancer and dermatological surgery and hopes to complete a fellowship in Mohs micrographic surgery after residency. In her free time, Dr. Croley enjoys spending time with her husband (an orthopedic surgeon), running and competing in marathons, and spending time on the beach.

Cutaneous melanoma is the most fatal form of skin cancer and is a considerable public health concern in the United States. Early detection and management of skin cancer can lead to decreased morbidity and mortality from skin cancer. As a result, the American Academy of Dermatology Association supports safe sun-protective practices and diligent self-screening for changing lesions.

Sunscreen use is an essential component of sun protection. New regulations from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have left consumers concerned about the safety of sunscreens. According to a recent Cutis editorial from Vincent A. DeLeo, MD, “There is no question that, as physicians, we want to ‘first, do no harm,’ so we should all be interested in assuring our patients that our sunscreen recommendations are safe and we support the FDA proposal for additional data.”

Patients with skin of color experience disproportionately higher morbidity and mortality when diagnosed with melanoma. “Poor prognosis in patients with skin of color is multifactorial and may be due to poor use of sun protection, misconceptions about melanoma risk, atypical clinical presentation, impaired access to care, and delay in diagnosis,” according to a recent Cutis article.

Population-based skin cancer screening performed exclusively by dermatologists is not practical. Primary care physicians and other experts in melanoma and public health need to be involved in reducing melanoma mortality.

In this chat, we will provide expert recommendations on the diagnosis of skin cancer, preventive measures, and the latest research discussed among physicians.

- “Doctor, Do I Need a Skin Check?”

- Assessing the effectiveness of knowledge-based interventions in skin of color populations.

- Melanoma in US Hispanics

- Podcast: Sunscreen update from Dr. Vincent DeLeo

- Windshield and UV exposure

- Racial, ethnic minorities often don’t practice sun-protective behaviors.

- Sunscreen regulations and advice for your patients.

Fluorouracil beats other actinic keratosis treatments in head-to-head trial

A head-to-head comparison of four commonly used field-directed treatments for actinic keratosis (AK) found that 5% fluorouracil cream was the most effective at reducing the size of lesions.

In a study published in the March 7 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, single-blind trial in 602 patients with five or more AK lesions in one continuous area on the head measuring 25-100 cm2. Patients were randomized to treatment with either 5% fluorouracil cream, 5% imiquimod cream, methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy (MAL-PDT), or 0.015% ingenol mebutate gel.

Overall, 74.7% of patients who received fluorouracil cream achieved treatment success – defined as at least a 75% reduction in lesion size at 12 months after the end of treatment – compared with 53.9% of patients treated with imiquimod, 37.7% of those treated with MAL-PDT, and 28.9% of those treated with ingenol mebutate. The differences between fluorouracil and the other treatments was significant.

Maud H.E. Jansen, MD, and Janneke P.H.M. Kessels, MD, of the department of dermatology at Maastricht (the Netherlands) University Medical Center and their coauthors pointed out that, while there was plenty of literature about different AK treatments, there were few head-to-head comparisons and many studies were underpowered or had different outcome measures.

Even when the analysis was restricted to patients with grade I or II lesions, fluorouracil remained the most effective treatment, with 75.3% of patients achieving treatment success, compared with 52.6% with imiquimod, 38.7% with MAL-PDT, and 30.2% with ingenol mebutate.

There were not enough patients with more severe grade III lesions to enable a separate analysis of their outcomes; 49 (7.9%) of patients in the study had at least one grade III lesion.

The authors noted that many previous studies had excluded patients with grade III lesions. “Exclusion of patients with grade III lesions was associated with slightly higher rates of success in the fluorouracil, MAL-PDT, and ingenol mebutate groups than the rates in the unrestricted analysis,” they wrote. The inclusion of patients with grade III AK lesions in this trial made it “more representative of patients seen in daily practice,” they added.

Treatment failure – less than 75% clearance of actinic keratosis at 3 months after the final treatment – was seen after one treatment cycle in 14.8% of patients treated with fluorouracil, 37.2% of patients on imiquimod, 34.6% of patients given photodynamic therapy, and 47.8% of patients on ingenol mebutate therapy.

All these patients were offered a second treatment cycle, but those treated with imiquimod, PDT, and ingenol mebutate were less likely to undergo a second treatment.

The authors suggested that the higher proportion of patients in the fluorouracil group who were willing to undergo a second round of therapy suggests they may have experienced less discomfort and inconvenience with the therapy to begin with, compared with those treated with the other regimens.

Full adherence to treatment was more common in the ingenol mebutate (98.7% of patients) and MAL-PDT (96.8%) groups, compared with the fluorouracil (88.7%) and imiquimod (88.2%) groups. However, patients in the fluorouracil group reported greater levels of patient satisfaction and improvements in health-related quality of life than did patients in the other treatment arms of the study.

No serious adverse events were reported with any of the treatments, and no patients stopped treatment because of adverse events. However, reports of moderate or severe crusts were highest among patients treated with imiquimod, and moderate to severe vesicles or bullae were highest among those treated with ingenol mebutate. Severe pain and severe burning sensation were significantly more common among those treated with MAL-PDT.

While the study had some limitations, the results “could affect treatment choices in both dermatology and primary care,” the authors wrote, pointing out how common AKs are in practice, accounting for 5 million dermatology visits in the United States every year. When considering treatment costs, “fluorouracil is also the most attractive option,” they added. “It is expected that a substantial cost reduction could be achieved with more uniformity in care and the choice for effective therapy.”

The study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Five of the 11 authors declared conference costs, advisory board fees, or trial supplies from private industry, including from manufacturers of some of the products in the study. The remaining authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Jansen M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-46.

A head-to-head comparison of four commonly used field-directed treatments for actinic keratosis (AK) found that 5% fluorouracil cream was the most effective at reducing the size of lesions.

In a study published in the March 7 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, single-blind trial in 602 patients with five or more AK lesions in one continuous area on the head measuring 25-100 cm2. Patients were randomized to treatment with either 5% fluorouracil cream, 5% imiquimod cream, methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy (MAL-PDT), or 0.015% ingenol mebutate gel.

Overall, 74.7% of patients who received fluorouracil cream achieved treatment success – defined as at least a 75% reduction in lesion size at 12 months after the end of treatment – compared with 53.9% of patients treated with imiquimod, 37.7% of those treated with MAL-PDT, and 28.9% of those treated with ingenol mebutate. The differences between fluorouracil and the other treatments was significant.

Maud H.E. Jansen, MD, and Janneke P.H.M. Kessels, MD, of the department of dermatology at Maastricht (the Netherlands) University Medical Center and their coauthors pointed out that, while there was plenty of literature about different AK treatments, there were few head-to-head comparisons and many studies were underpowered or had different outcome measures.

Even when the analysis was restricted to patients with grade I or II lesions, fluorouracil remained the most effective treatment, with 75.3% of patients achieving treatment success, compared with 52.6% with imiquimod, 38.7% with MAL-PDT, and 30.2% with ingenol mebutate.

There were not enough patients with more severe grade III lesions to enable a separate analysis of their outcomes; 49 (7.9%) of patients in the study had at least one grade III lesion.

The authors noted that many previous studies had excluded patients with grade III lesions. “Exclusion of patients with grade III lesions was associated with slightly higher rates of success in the fluorouracil, MAL-PDT, and ingenol mebutate groups than the rates in the unrestricted analysis,” they wrote. The inclusion of patients with grade III AK lesions in this trial made it “more representative of patients seen in daily practice,” they added.

Treatment failure – less than 75% clearance of actinic keratosis at 3 months after the final treatment – was seen after one treatment cycle in 14.8% of patients treated with fluorouracil, 37.2% of patients on imiquimod, 34.6% of patients given photodynamic therapy, and 47.8% of patients on ingenol mebutate therapy.

All these patients were offered a second treatment cycle, but those treated with imiquimod, PDT, and ingenol mebutate were less likely to undergo a second treatment.

The authors suggested that the higher proportion of patients in the fluorouracil group who were willing to undergo a second round of therapy suggests they may have experienced less discomfort and inconvenience with the therapy to begin with, compared with those treated with the other regimens.

Full adherence to treatment was more common in the ingenol mebutate (98.7% of patients) and MAL-PDT (96.8%) groups, compared with the fluorouracil (88.7%) and imiquimod (88.2%) groups. However, patients in the fluorouracil group reported greater levels of patient satisfaction and improvements in health-related quality of life than did patients in the other treatment arms of the study.

No serious adverse events were reported with any of the treatments, and no patients stopped treatment because of adverse events. However, reports of moderate or severe crusts were highest among patients treated with imiquimod, and moderate to severe vesicles or bullae were highest among those treated with ingenol mebutate. Severe pain and severe burning sensation were significantly more common among those treated with MAL-PDT.

While the study had some limitations, the results “could affect treatment choices in both dermatology and primary care,” the authors wrote, pointing out how common AKs are in practice, accounting for 5 million dermatology visits in the United States every year. When considering treatment costs, “fluorouracil is also the most attractive option,” they added. “It is expected that a substantial cost reduction could be achieved with more uniformity in care and the choice for effective therapy.”

The study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Five of the 11 authors declared conference costs, advisory board fees, or trial supplies from private industry, including from manufacturers of some of the products in the study. The remaining authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Jansen M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-46.

A head-to-head comparison of four commonly used field-directed treatments for actinic keratosis (AK) found that 5% fluorouracil cream was the most effective at reducing the size of lesions.

In a study published in the March 7 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers reported the outcomes of a multicenter, single-blind trial in 602 patients with five or more AK lesions in one continuous area on the head measuring 25-100 cm2. Patients were randomized to treatment with either 5% fluorouracil cream, 5% imiquimod cream, methyl aminolevulinate photodynamic therapy (MAL-PDT), or 0.015% ingenol mebutate gel.

Overall, 74.7% of patients who received fluorouracil cream achieved treatment success – defined as at least a 75% reduction in lesion size at 12 months after the end of treatment – compared with 53.9% of patients treated with imiquimod, 37.7% of those treated with MAL-PDT, and 28.9% of those treated with ingenol mebutate. The differences between fluorouracil and the other treatments was significant.

Maud H.E. Jansen, MD, and Janneke P.H.M. Kessels, MD, of the department of dermatology at Maastricht (the Netherlands) University Medical Center and their coauthors pointed out that, while there was plenty of literature about different AK treatments, there were few head-to-head comparisons and many studies were underpowered or had different outcome measures.

Even when the analysis was restricted to patients with grade I or II lesions, fluorouracil remained the most effective treatment, with 75.3% of patients achieving treatment success, compared with 52.6% with imiquimod, 38.7% with MAL-PDT, and 30.2% with ingenol mebutate.

There were not enough patients with more severe grade III lesions to enable a separate analysis of their outcomes; 49 (7.9%) of patients in the study had at least one grade III lesion.

The authors noted that many previous studies had excluded patients with grade III lesions. “Exclusion of patients with grade III lesions was associated with slightly higher rates of success in the fluorouracil, MAL-PDT, and ingenol mebutate groups than the rates in the unrestricted analysis,” they wrote. The inclusion of patients with grade III AK lesions in this trial made it “more representative of patients seen in daily practice,” they added.

Treatment failure – less than 75% clearance of actinic keratosis at 3 months after the final treatment – was seen after one treatment cycle in 14.8% of patients treated with fluorouracil, 37.2% of patients on imiquimod, 34.6% of patients given photodynamic therapy, and 47.8% of patients on ingenol mebutate therapy.

All these patients were offered a second treatment cycle, but those treated with imiquimod, PDT, and ingenol mebutate were less likely to undergo a second treatment.

The authors suggested that the higher proportion of patients in the fluorouracil group who were willing to undergo a second round of therapy suggests they may have experienced less discomfort and inconvenience with the therapy to begin with, compared with those treated with the other regimens.

Full adherence to treatment was more common in the ingenol mebutate (98.7% of patients) and MAL-PDT (96.8%) groups, compared with the fluorouracil (88.7%) and imiquimod (88.2%) groups. However, patients in the fluorouracil group reported greater levels of patient satisfaction and improvements in health-related quality of life than did patients in the other treatment arms of the study.

No serious adverse events were reported with any of the treatments, and no patients stopped treatment because of adverse events. However, reports of moderate or severe crusts were highest among patients treated with imiquimod, and moderate to severe vesicles or bullae were highest among those treated with ingenol mebutate. Severe pain and severe burning sensation were significantly more common among those treated with MAL-PDT.

While the study had some limitations, the results “could affect treatment choices in both dermatology and primary care,” the authors wrote, pointing out how common AKs are in practice, accounting for 5 million dermatology visits in the United States every year. When considering treatment costs, “fluorouracil is also the most attractive option,” they added. “It is expected that a substantial cost reduction could be achieved with more uniformity in care and the choice for effective therapy.”

The study was supported by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development. Five of the 11 authors declared conference costs, advisory board fees, or trial supplies from private industry, including from manufacturers of some of the products in the study. The remaining authors had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Jansen M et al. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:935-46.

FROM THE NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL OF MEDICINE

Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa Secondary to Scleroderma

To the Editor:

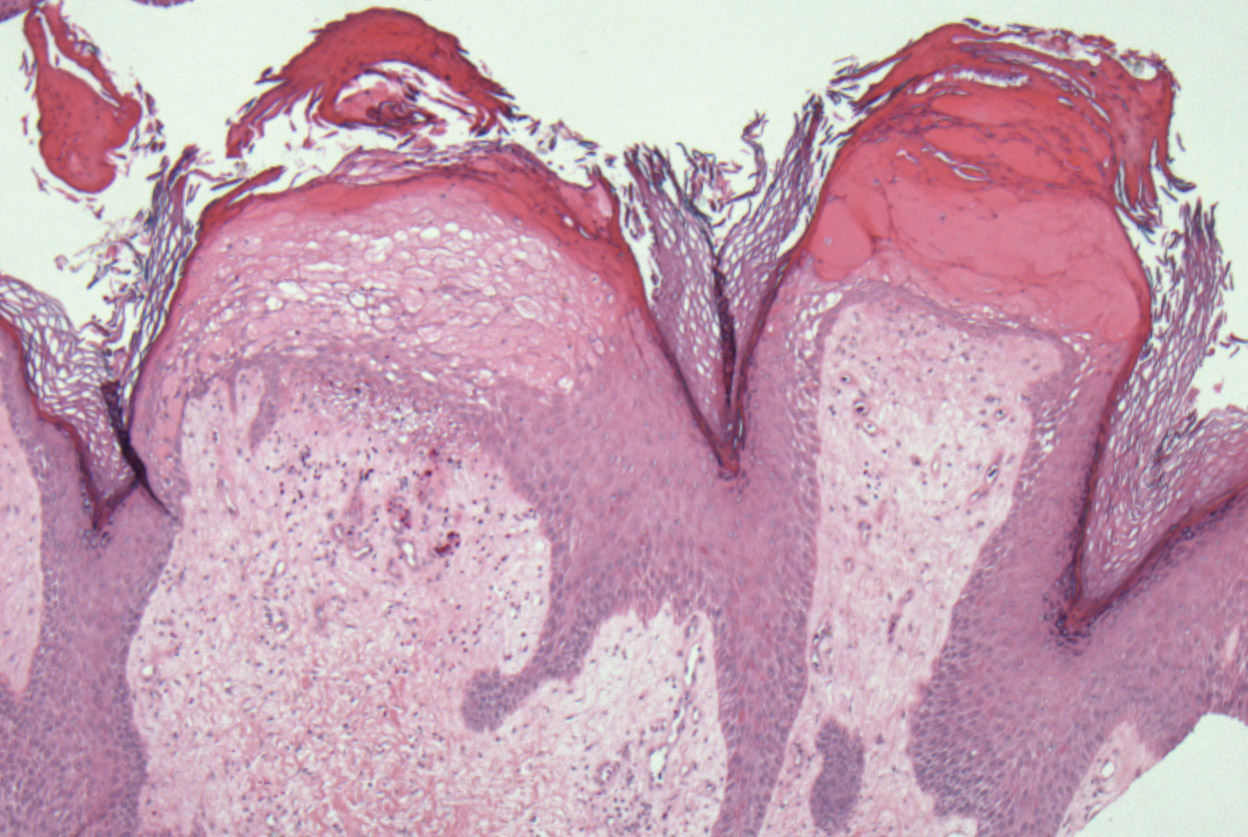

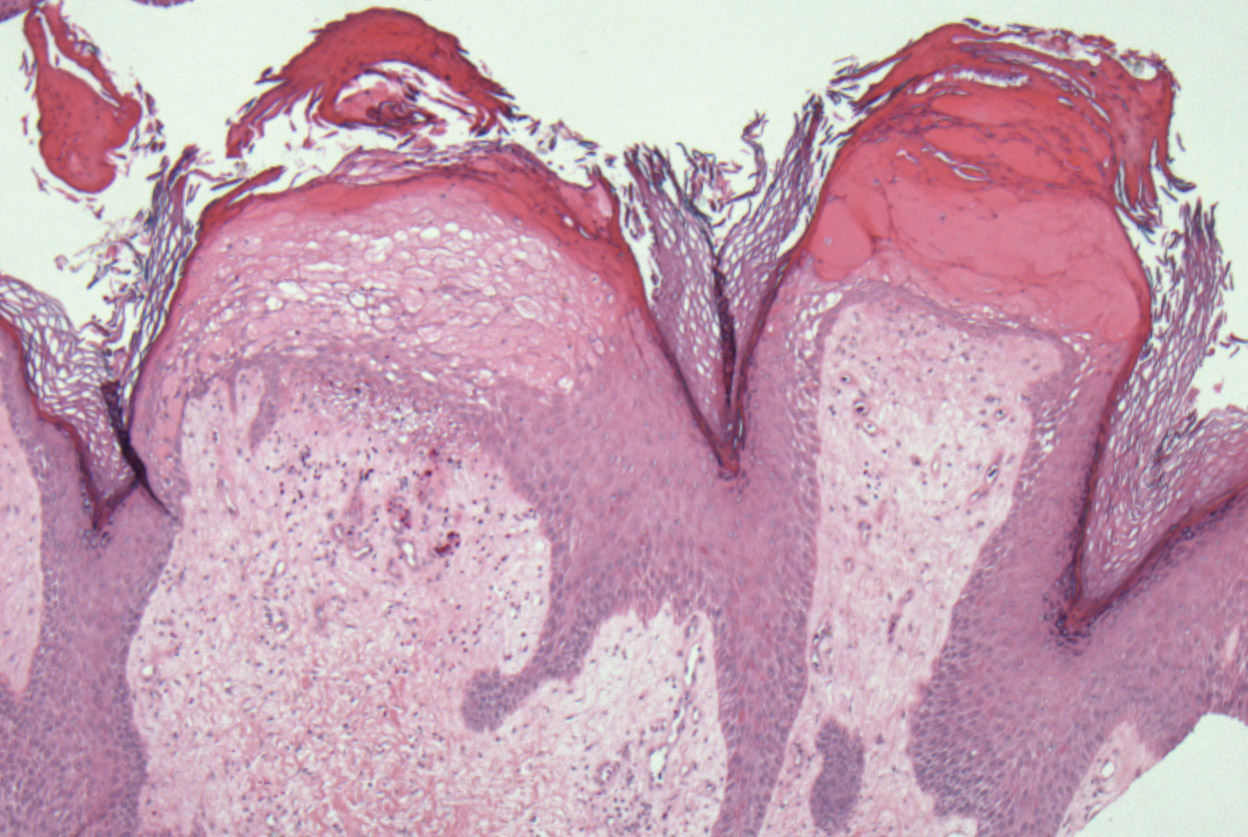

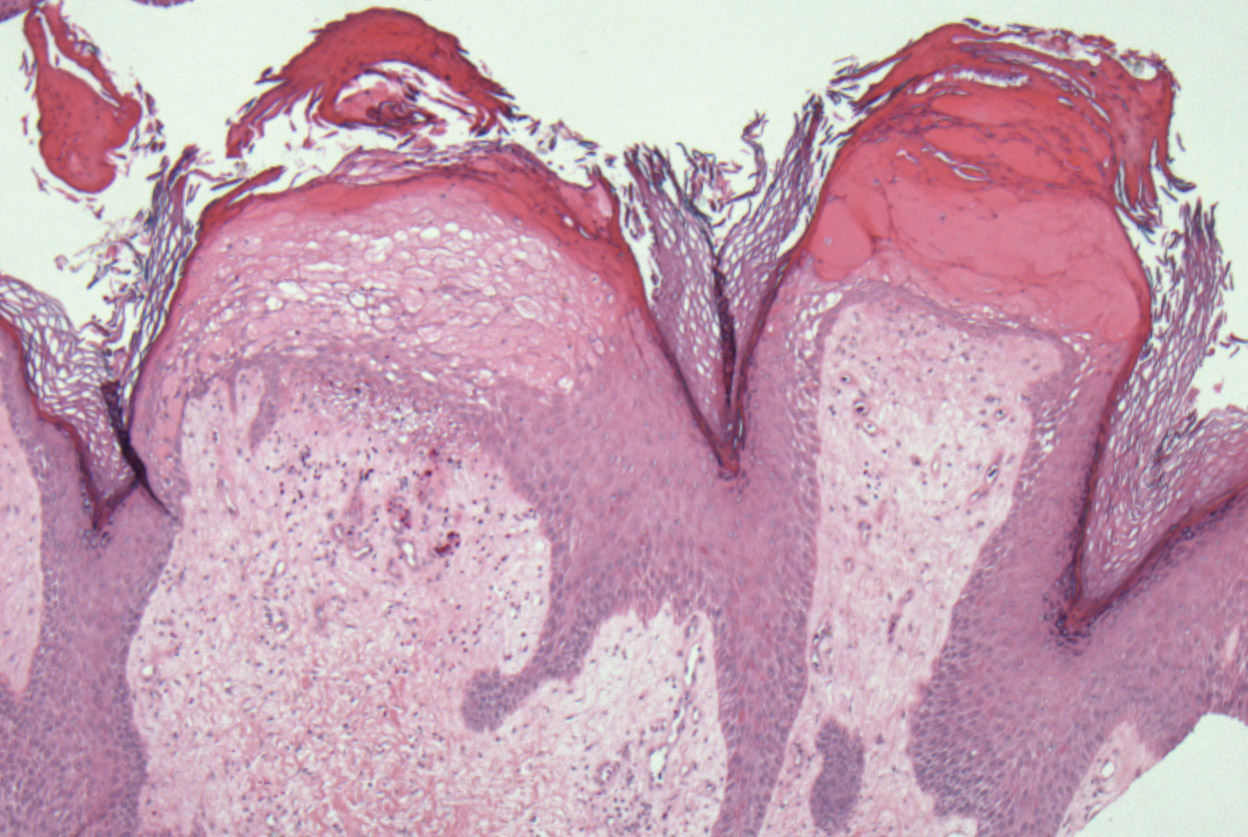

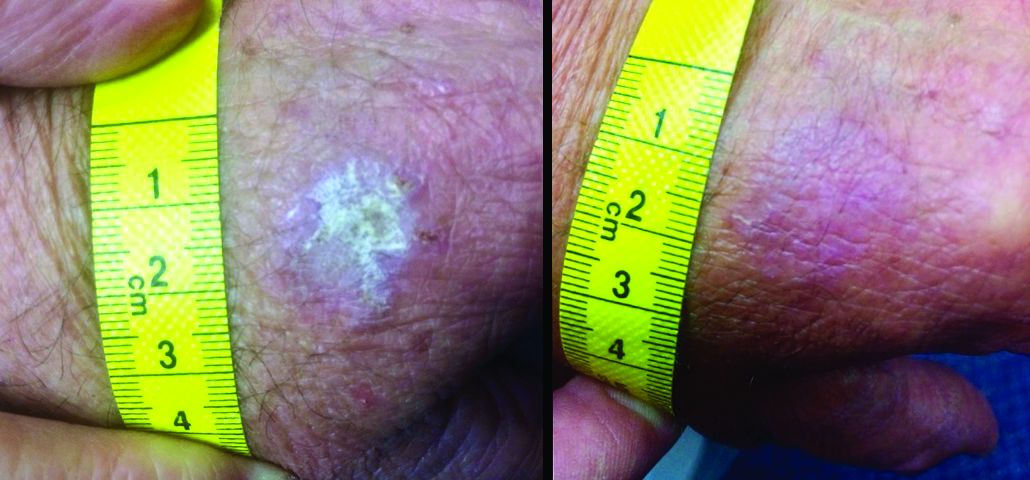

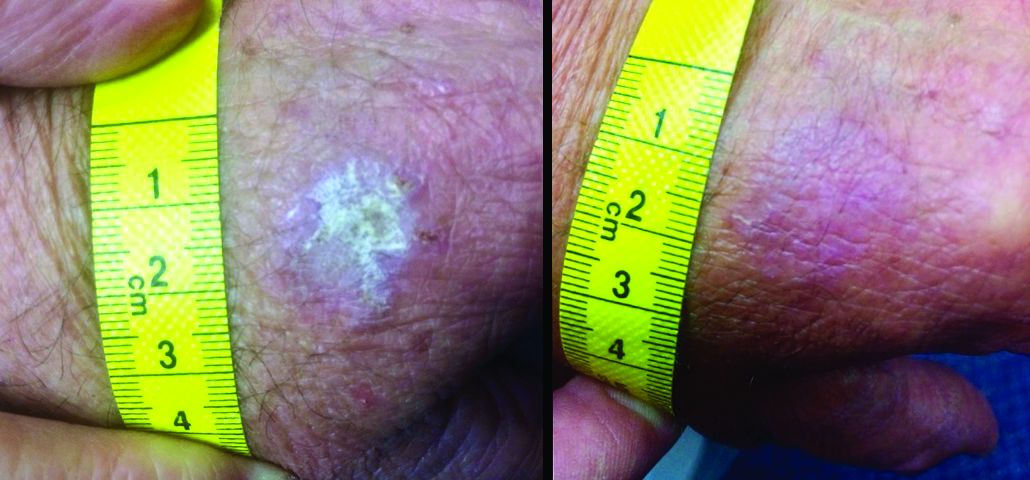

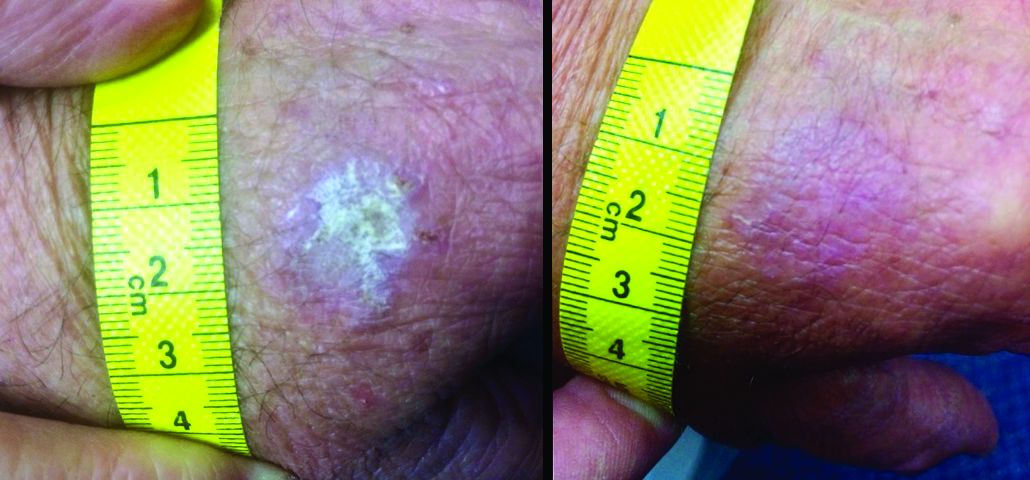

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a skin disorder caused by marked underlying lymphedema that leads to hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and verrucous growths on the epidermis.1 The pathophysiology of ENV relates to noninfectious lymphatic obstruction and lymphatic fibrosis secondary to venous stasis, malignancy, radiation therapy, or trauma.2 We present an unusual case of lymphedema and subsequent ENV limited to the arms and hands in a patient with scleroderma, an autoimmune fibrosing disorder.

A 54-year-old woman with a 5-year history of scleroderma presented to our dermatology clinic for treatment of progressive skin changes including pruritus, tightness, finger ulcerations, and pus exuding from papules on the dorsal arms and hands. She had been experiencing several systemic symptoms including dysphagia and lung involvement, necessitating oxygen therapy and a continuous positive airway pressure device for pulmonary arterial hypertension. A computed tomography scan of the lungs demonstrated an increase in ground-glass infiltrates in the right lower lobe and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. At the time of presentation, she was being treated with bosentan and sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension, in addition to prednisone, venlafaxine, lansoprazole, metoclopramide, levothyroxine, temazepam, aspirin, and oxycodone. In the 2 years prior to presentation, she had been treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide once monthly for 6 months, adalimumab for 1 year, and 1 session of photodynamic therapy to the arms, all without benefit.