User login

Elephantiasis Nostras Verrucosa Secondary to Scleroderma

To the Editor:

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a skin disorder caused by marked underlying lymphedema that leads to hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and verrucous growths on the epidermis.1 The pathophysiology of ENV relates to noninfectious lymphatic obstruction and lymphatic fibrosis secondary to venous stasis, malignancy, radiation therapy, or trauma.2 We present an unusual case of lymphedema and subsequent ENV limited to the arms and hands in a patient with scleroderma, an autoimmune fibrosing disorder.

A 54-year-old woman with a 5-year history of scleroderma presented to our dermatology clinic for treatment of progressive skin changes including pruritus, tightness, finger ulcerations, and pus exuding from papules on the dorsal arms and hands. She had been experiencing several systemic symptoms including dysphagia and lung involvement, necessitating oxygen therapy and a continuous positive airway pressure device for pulmonary arterial hypertension. A computed tomography scan of the lungs demonstrated an increase in ground-glass infiltrates in the right lower lobe and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. At the time of presentation, she was being treated with bosentan and sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension, in addition to prednisone, venlafaxine, lansoprazole, metoclopramide, levothyroxine, temazepam, aspirin, and oxycodone. In the 2 years prior to presentation, she had been treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide once monthly for 6 months, adalimumab for 1 year, and 1 session of photodynamic therapy to the arms, all without benefit.

Physical examination showed cutaneous signs of scleroderma including marked sclerosis of the skin on the face, hands, V of the neck, proximal arms, and mid and proximal thighs. Excoriated papules with overlying crusting and pustulation were superimposed on the sclerotic skin of the arms (Figure 1).

A superinfection was diagnosed and treated with cephalexin 500 mg 4 times daily for 2 weeks; thereafter, mupirocin cream twice daily was used as needed. She was prescribed fexofenadine 180 mg twice daily and doxepin 20 mg at bedtime for pruritus.

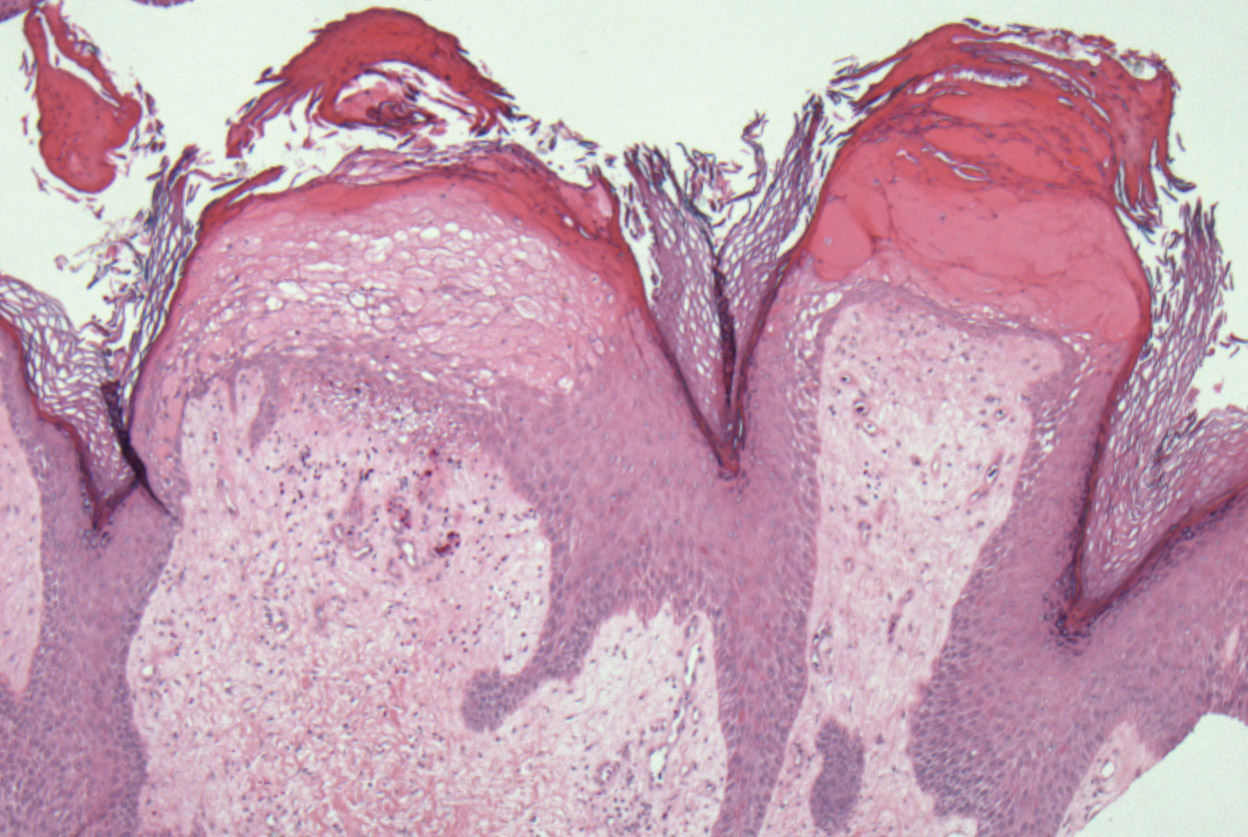

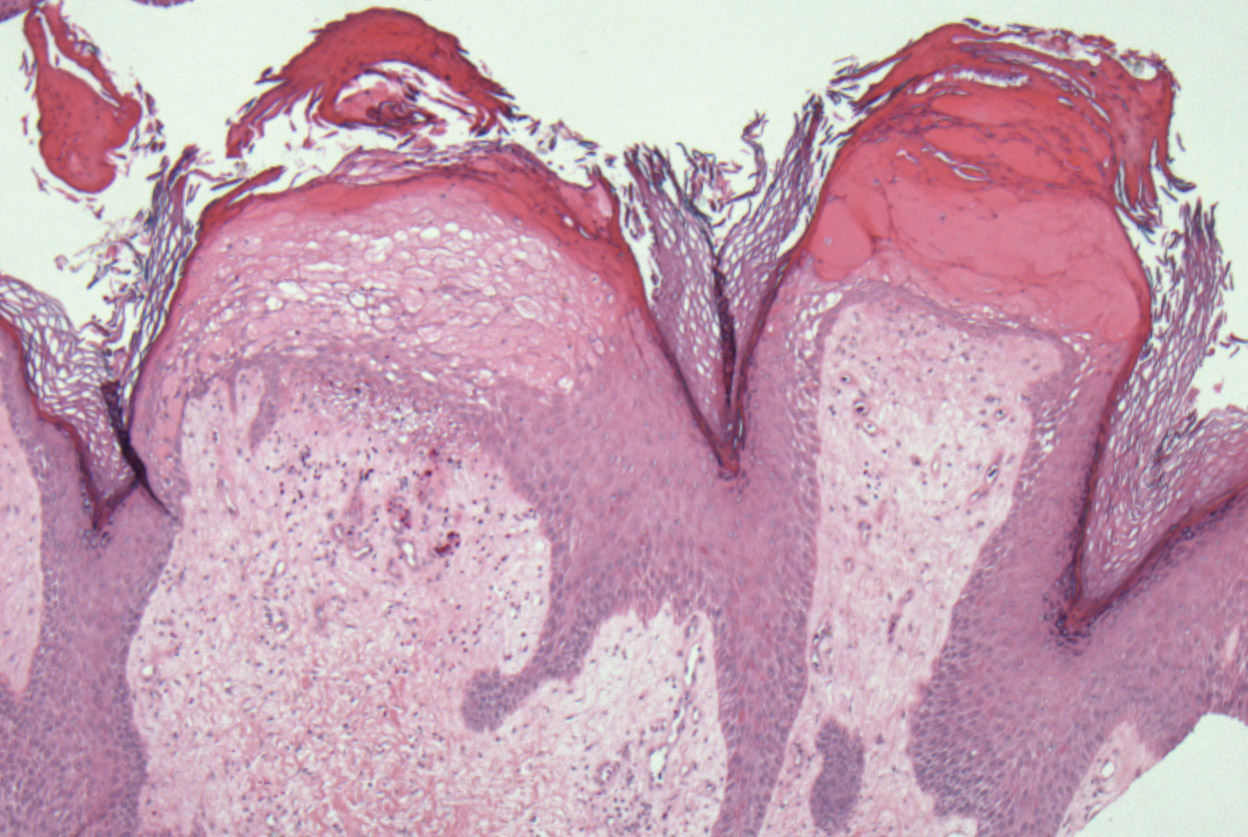

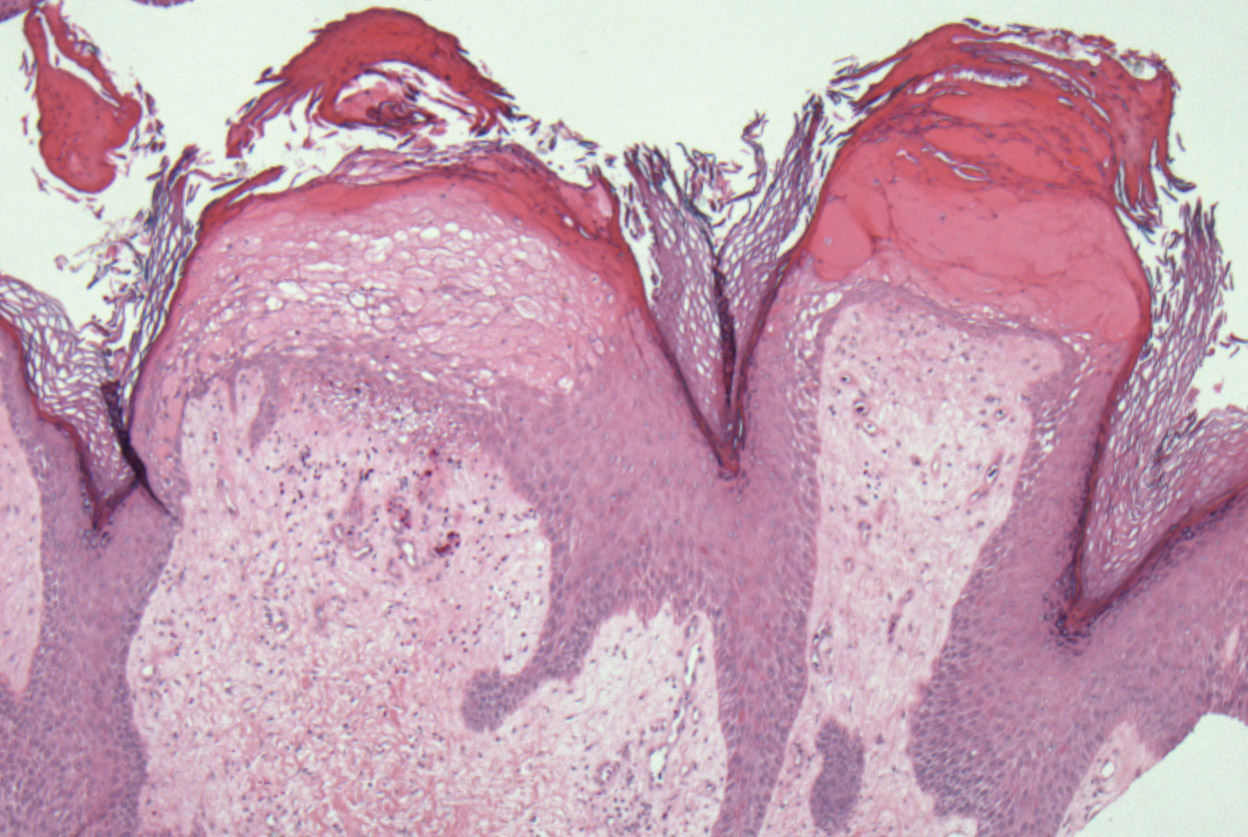

At 3-week follow-up, a trial of narrowband UVB therapy was recommended for control of pruritus. Two weeks later, a modified wet-wrap regimen using clobetasol ointment 0.5% twice daily covered with wet gauze followed by a self-adherent dressing was initiated only on the right arm for comparison purposes. This treatment was not successful. A biopsy taken from the left arm showed lymphedema with perivascular fibroplasia and epidermal hyperplasia consistent with ENV (Figure 2).

Two months after her initial presentation, we instituted treatment with tazarotene gel 0.1% twice daily to the arms as well as a water-based topical emulsion to the finger ulcerations and a healing ointment to the hands. A month later, the patient reported no benefit with tazarotene. She desired more flexibility in her arms and hands; therefore, after a discussion with her rheumatologist, biweekly psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy was initiated. Five months after presentation, methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg once weekly with folic acid 1 mg once daily was added. The PUVA therapy and MTX were stopped 3 months later due to lack of treatment benefit.

The patient was referred to vascular medicine for possible compression therapy. It was determined that her vasculature was intact, but compression therapy was contraindicated due to underlying systemic sclerosis. She was subsequently prescribed mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. The options of serial excisions or laser resurfacing were presented, but she declined.

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is differentiated from elephantiasis tropica, which is caused by a filarial infection of the lymphatic system. The chronic obstructive lymphedema characteristic of ENV can present as a result of various primary or secondary etiologies including trauma, malignancy, venous stasis, inflammation, or infection.3 In systemic sclerosis, extravascular fibrosis theoretically can lead to lymphatic obstruction and subsequent lymphatic stasis. In turn, the pathophysiology of dermal and subcutaneous fibrosis likely reflects autoantibodies (eg, anticardiolipin antibodies) that can damage lymphatic and nonlymphatic vessels.4,5

As the underlying mechanism of ENV, fibrosis of lymphatic vessels in systemic sclerosis is not well documented. Characteristic features of systemic sclerosis include extensive fibrosis, fibroproliferative vasculopathy, and inflammation, which are all possible mechanisms for the internal lymphatic obstruction resulting in the skin changes observed in ENV.6 It seemed unusual that the fibrotic changes of lymphatic vessels in our patient were extensive enough to cause ENV of the upper extremities; lower extremity involvement is the more common presentation because of the greater likelihood of lymphedema manifesting in the legs and feet. Lower extremity ENV has been reported in association with scleroderma.7,8

Regarding therapeutic options, Boyd et al9 reported a good response in a patient with ENV of the abdomen who was treated with topical tazarotene. Additionally, PUVA and MTX have been reported to be beneficial for the progressive skin changes of systemic sclerosis.10 Mycophenolate mofetil has been used in patients who fail MTX therapy because of its antifibrotic properties without the side-effect profiles of other immunosuppressives, such as imatinib.10,11 In our patient, skin lesions persisted following these varied approaches, and compression therapy was not advised due to the underlying sclerosis.

Because options for medical treatment of severe ENV are limited, surgical debridement of the affected limb often remains the only viable option in advanced cases.12 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms elephantiasis (MeSH terms) or elephantiasis (all fields) and scleroderma, systemic (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and systemic (all fields) or systemic scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma, localized (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and localized (all fields) or localized scleroderma (all fields) yielded only 1 other case report of lower extremity ENV in a patient with systemic sclerosis who ultimately required bilateral leg amputation.8 When possible, avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of any underlying infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.3

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

- Schissel DJ, Hivnor C, Elston DM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis. 1998;62:77-80.

- Duckworth A, Husain J, DeHeer P. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa or ‘mossy foot lesions’ in lymphedema praecox. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:66-69.

- Assous N, Allanore Y, Batteaux F, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic sclerosis and association with primitive pulmonary arterial hypertension and endothelial injury. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:199-204.

- Derrett-Smith EC, Dooley A, Gilbane AJ, et al. Endothelial injury in a transforming growth-factor-dependent mouse model of scleroderma induces pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2928-2939.

- Pattanaik M, Brown M, Postlethwaite A. Vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). J Inflamm Res. 2011;4:105-125.

- Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:324-331.

- Chatterjee S, Karai L. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e696-e698.

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:446-448.

- Fett, N. Scleroderma: nomenclature, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Moinzadeh P, Krieg T, Hunzelmann N. Imatinib treatment of generalized localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e102-e104.

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941.

To the Editor:

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a skin disorder caused by marked underlying lymphedema that leads to hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and verrucous growths on the epidermis.1 The pathophysiology of ENV relates to noninfectious lymphatic obstruction and lymphatic fibrosis secondary to venous stasis, malignancy, radiation therapy, or trauma.2 We present an unusual case of lymphedema and subsequent ENV limited to the arms and hands in a patient with scleroderma, an autoimmune fibrosing disorder.

A 54-year-old woman with a 5-year history of scleroderma presented to our dermatology clinic for treatment of progressive skin changes including pruritus, tightness, finger ulcerations, and pus exuding from papules on the dorsal arms and hands. She had been experiencing several systemic symptoms including dysphagia and lung involvement, necessitating oxygen therapy and a continuous positive airway pressure device for pulmonary arterial hypertension. A computed tomography scan of the lungs demonstrated an increase in ground-glass infiltrates in the right lower lobe and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. At the time of presentation, she was being treated with bosentan and sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension, in addition to prednisone, venlafaxine, lansoprazole, metoclopramide, levothyroxine, temazepam, aspirin, and oxycodone. In the 2 years prior to presentation, she had been treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide once monthly for 6 months, adalimumab for 1 year, and 1 session of photodynamic therapy to the arms, all without benefit.

Physical examination showed cutaneous signs of scleroderma including marked sclerosis of the skin on the face, hands, V of the neck, proximal arms, and mid and proximal thighs. Excoriated papules with overlying crusting and pustulation were superimposed on the sclerotic skin of the arms (Figure 1).

A superinfection was diagnosed and treated with cephalexin 500 mg 4 times daily for 2 weeks; thereafter, mupirocin cream twice daily was used as needed. She was prescribed fexofenadine 180 mg twice daily and doxepin 20 mg at bedtime for pruritus.

At 3-week follow-up, a trial of narrowband UVB therapy was recommended for control of pruritus. Two weeks later, a modified wet-wrap regimen using clobetasol ointment 0.5% twice daily covered with wet gauze followed by a self-adherent dressing was initiated only on the right arm for comparison purposes. This treatment was not successful. A biopsy taken from the left arm showed lymphedema with perivascular fibroplasia and epidermal hyperplasia consistent with ENV (Figure 2).

Two months after her initial presentation, we instituted treatment with tazarotene gel 0.1% twice daily to the arms as well as a water-based topical emulsion to the finger ulcerations and a healing ointment to the hands. A month later, the patient reported no benefit with tazarotene. She desired more flexibility in her arms and hands; therefore, after a discussion with her rheumatologist, biweekly psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy was initiated. Five months after presentation, methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg once weekly with folic acid 1 mg once daily was added. The PUVA therapy and MTX were stopped 3 months later due to lack of treatment benefit.

The patient was referred to vascular medicine for possible compression therapy. It was determined that her vasculature was intact, but compression therapy was contraindicated due to underlying systemic sclerosis. She was subsequently prescribed mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. The options of serial excisions or laser resurfacing were presented, but she declined.

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is differentiated from elephantiasis tropica, which is caused by a filarial infection of the lymphatic system. The chronic obstructive lymphedema characteristic of ENV can present as a result of various primary or secondary etiologies including trauma, malignancy, venous stasis, inflammation, or infection.3 In systemic sclerosis, extravascular fibrosis theoretically can lead to lymphatic obstruction and subsequent lymphatic stasis. In turn, the pathophysiology of dermal and subcutaneous fibrosis likely reflects autoantibodies (eg, anticardiolipin antibodies) that can damage lymphatic and nonlymphatic vessels.4,5

As the underlying mechanism of ENV, fibrosis of lymphatic vessels in systemic sclerosis is not well documented. Characteristic features of systemic sclerosis include extensive fibrosis, fibroproliferative vasculopathy, and inflammation, which are all possible mechanisms for the internal lymphatic obstruction resulting in the skin changes observed in ENV.6 It seemed unusual that the fibrotic changes of lymphatic vessels in our patient were extensive enough to cause ENV of the upper extremities; lower extremity involvement is the more common presentation because of the greater likelihood of lymphedema manifesting in the legs and feet. Lower extremity ENV has been reported in association with scleroderma.7,8

Regarding therapeutic options, Boyd et al9 reported a good response in a patient with ENV of the abdomen who was treated with topical tazarotene. Additionally, PUVA and MTX have been reported to be beneficial for the progressive skin changes of systemic sclerosis.10 Mycophenolate mofetil has been used in patients who fail MTX therapy because of its antifibrotic properties without the side-effect profiles of other immunosuppressives, such as imatinib.10,11 In our patient, skin lesions persisted following these varied approaches, and compression therapy was not advised due to the underlying sclerosis.

Because options for medical treatment of severe ENV are limited, surgical debridement of the affected limb often remains the only viable option in advanced cases.12 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms elephantiasis (MeSH terms) or elephantiasis (all fields) and scleroderma, systemic (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and systemic (all fields) or systemic scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma, localized (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and localized (all fields) or localized scleroderma (all fields) yielded only 1 other case report of lower extremity ENV in a patient with systemic sclerosis who ultimately required bilateral leg amputation.8 When possible, avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of any underlying infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.3

To the Editor:

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) is a skin disorder caused by marked underlying lymphedema that leads to hyperkeratosis, papillomatosis, and verrucous growths on the epidermis.1 The pathophysiology of ENV relates to noninfectious lymphatic obstruction and lymphatic fibrosis secondary to venous stasis, malignancy, radiation therapy, or trauma.2 We present an unusual case of lymphedema and subsequent ENV limited to the arms and hands in a patient with scleroderma, an autoimmune fibrosing disorder.

A 54-year-old woman with a 5-year history of scleroderma presented to our dermatology clinic for treatment of progressive skin changes including pruritus, tightness, finger ulcerations, and pus exuding from papules on the dorsal arms and hands. She had been experiencing several systemic symptoms including dysphagia and lung involvement, necessitating oxygen therapy and a continuous positive airway pressure device for pulmonary arterial hypertension. A computed tomography scan of the lungs demonstrated an increase in ground-glass infiltrates in the right lower lobe and an air-fluid level in the esophagus. At the time of presentation, she was being treated with bosentan and sildenafil for pulmonary arterial hypertension, in addition to prednisone, venlafaxine, lansoprazole, metoclopramide, levothyroxine, temazepam, aspirin, and oxycodone. In the 2 years prior to presentation, she had been treated with intravenous cyclophosphamide once monthly for 6 months, adalimumab for 1 year, and 1 session of photodynamic therapy to the arms, all without benefit.

Physical examination showed cutaneous signs of scleroderma including marked sclerosis of the skin on the face, hands, V of the neck, proximal arms, and mid and proximal thighs. Excoriated papules with overlying crusting and pustulation were superimposed on the sclerotic skin of the arms (Figure 1).

A superinfection was diagnosed and treated with cephalexin 500 mg 4 times daily for 2 weeks; thereafter, mupirocin cream twice daily was used as needed. She was prescribed fexofenadine 180 mg twice daily and doxepin 20 mg at bedtime for pruritus.

At 3-week follow-up, a trial of narrowband UVB therapy was recommended for control of pruritus. Two weeks later, a modified wet-wrap regimen using clobetasol ointment 0.5% twice daily covered with wet gauze followed by a self-adherent dressing was initiated only on the right arm for comparison purposes. This treatment was not successful. A biopsy taken from the left arm showed lymphedema with perivascular fibroplasia and epidermal hyperplasia consistent with ENV (Figure 2).

Two months after her initial presentation, we instituted treatment with tazarotene gel 0.1% twice daily to the arms as well as a water-based topical emulsion to the finger ulcerations and a healing ointment to the hands. A month later, the patient reported no benefit with tazarotene. She desired more flexibility in her arms and hands; therefore, after a discussion with her rheumatologist, biweekly psoralen plus UVA (PUVA) therapy was initiated. Five months after presentation, methotrexate (MTX) 15 mg once weekly with folic acid 1 mg once daily was added. The PUVA therapy and MTX were stopped 3 months later due to lack of treatment benefit.

The patient was referred to vascular medicine for possible compression therapy. It was determined that her vasculature was intact, but compression therapy was contraindicated due to underlying systemic sclerosis. She was subsequently prescribed mycophenolate mofetil 1000 mg twice daily by her rheumatologist. The options of serial excisions or laser resurfacing were presented, but she declined.

Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is differentiated from elephantiasis tropica, which is caused by a filarial infection of the lymphatic system. The chronic obstructive lymphedema characteristic of ENV can present as a result of various primary or secondary etiologies including trauma, malignancy, venous stasis, inflammation, or infection.3 In systemic sclerosis, extravascular fibrosis theoretically can lead to lymphatic obstruction and subsequent lymphatic stasis. In turn, the pathophysiology of dermal and subcutaneous fibrosis likely reflects autoantibodies (eg, anticardiolipin antibodies) that can damage lymphatic and nonlymphatic vessels.4,5

As the underlying mechanism of ENV, fibrosis of lymphatic vessels in systemic sclerosis is not well documented. Characteristic features of systemic sclerosis include extensive fibrosis, fibroproliferative vasculopathy, and inflammation, which are all possible mechanisms for the internal lymphatic obstruction resulting in the skin changes observed in ENV.6 It seemed unusual that the fibrotic changes of lymphatic vessels in our patient were extensive enough to cause ENV of the upper extremities; lower extremity involvement is the more common presentation because of the greater likelihood of lymphedema manifesting in the legs and feet. Lower extremity ENV has been reported in association with scleroderma.7,8

Regarding therapeutic options, Boyd et al9 reported a good response in a patient with ENV of the abdomen who was treated with topical tazarotene. Additionally, PUVA and MTX have been reported to be beneficial for the progressive skin changes of systemic sclerosis.10 Mycophenolate mofetil has been used in patients who fail MTX therapy because of its antifibrotic properties without the side-effect profiles of other immunosuppressives, such as imatinib.10,11 In our patient, skin lesions persisted following these varied approaches, and compression therapy was not advised due to the underlying sclerosis.

Because options for medical treatment of severe ENV are limited, surgical debridement of the affected limb often remains the only viable option in advanced cases.12 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms elephantiasis (MeSH terms) or elephantiasis (all fields) and scleroderma, systemic (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and systemic (all fields) or systemic scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma (all fields) or scleroderma, localized (MeSH terms) or scleroderma (all fields) and localized (all fields) or localized scleroderma (all fields) yielded only 1 other case report of lower extremity ENV in a patient with systemic sclerosis who ultimately required bilateral leg amputation.8 When possible, avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of any underlying infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.3

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

- Schissel DJ, Hivnor C, Elston DM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis. 1998;62:77-80.

- Duckworth A, Husain J, DeHeer P. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa or ‘mossy foot lesions’ in lymphedema praecox. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:66-69.

- Assous N, Allanore Y, Batteaux F, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic sclerosis and association with primitive pulmonary arterial hypertension and endothelial injury. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:199-204.

- Derrett-Smith EC, Dooley A, Gilbane AJ, et al. Endothelial injury in a transforming growth-factor-dependent mouse model of scleroderma induces pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2928-2939.

- Pattanaik M, Brown M, Postlethwaite A. Vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). J Inflamm Res. 2011;4:105-125.

- Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:324-331.

- Chatterjee S, Karai L. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e696-e698.

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:446-448.

- Fett, N. Scleroderma: nomenclature, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Moinzadeh P, Krieg T, Hunzelmann N. Imatinib treatment of generalized localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e102-e104.

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941.

- Sisto K, Khachemoune A. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa: a review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2008;9:141-146.

- Schissel DJ, Hivnor C, Elston DM. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. Cutis. 1998;62:77-80.

- Duckworth A, Husain J, DeHeer P. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa or ‘mossy foot lesions’ in lymphedema praecox. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:66-69.

- Assous N, Allanore Y, Batteaux F, et al. Prevalence of antiphospholipid antibodies in systemic sclerosis and association with primitive pulmonary arterial hypertension and endothelial injury. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:199-204.

- Derrett-Smith EC, Dooley A, Gilbane AJ, et al. Endothelial injury in a transforming growth-factor-dependent mouse model of scleroderma induces pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:2928-2939.

- Pattanaik M, Brown M, Postlethwaite A. Vascular involvement in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). J Inflamm Res. 2011;4:105-125.

- Kerchner K, Fleischer A, Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:324-331.

- Chatterjee S, Karai L. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:e696-e698.

- Boyd J, Sloan S, Meffert J. Elephantiasis nostrum verrucosa of the abdomen: clinical results with tazarotene. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3:446-448.

- Fett, N. Scleroderma: nomenclature, etiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, and treatments: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2013;31:432-437.

- Moinzadeh P, Krieg T, Hunzelmann N. Imatinib treatment of generalized localized scleroderma (morphea). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:e102-e104.

- Iwao F, Sato-Matsumura KC, Sawamura D, et al. Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa successfully treated by surgical debridement. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:939-941.

Practice Points

- Scleroderma rarely may lead to elephantiasis nostras verrucosa (ENV) of the upper extremities.

- Avoiding lymphostasis through compression and control of concomitant skin and soft tissue infections is important in the treatment and prevention of ENV.

Nonhealing Eroded Plaque on an Interdigital Web Space of the Foot

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

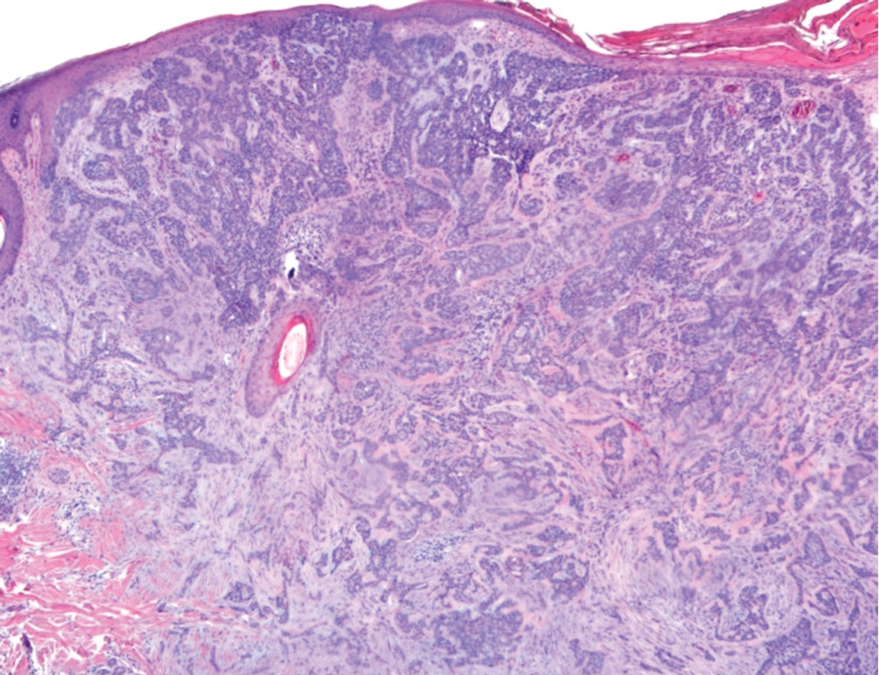

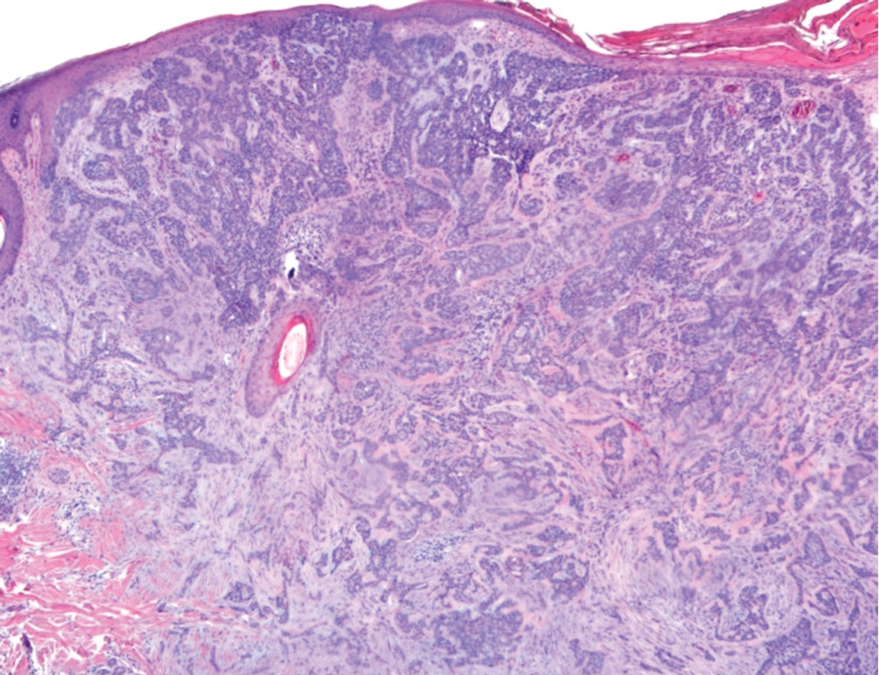

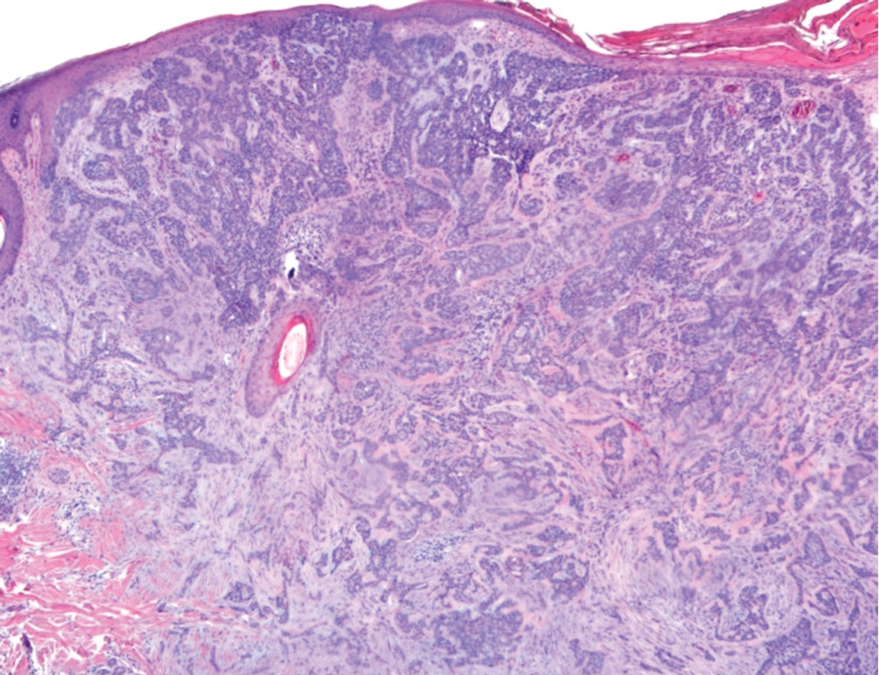

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

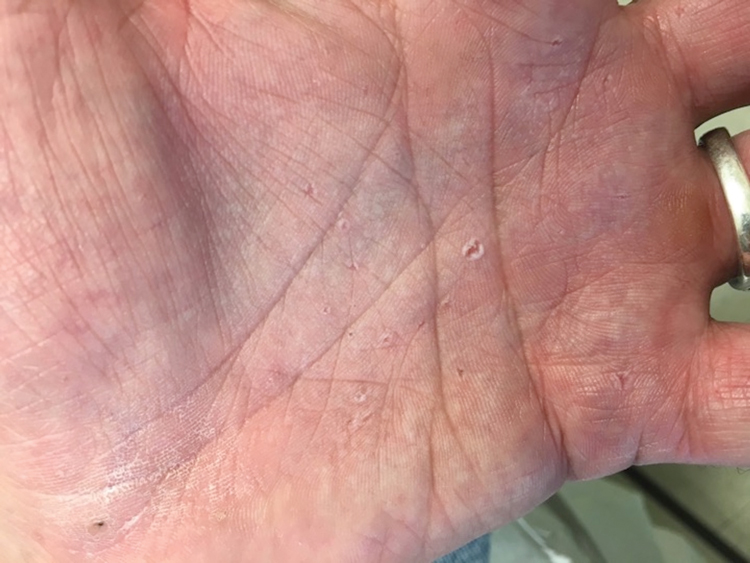

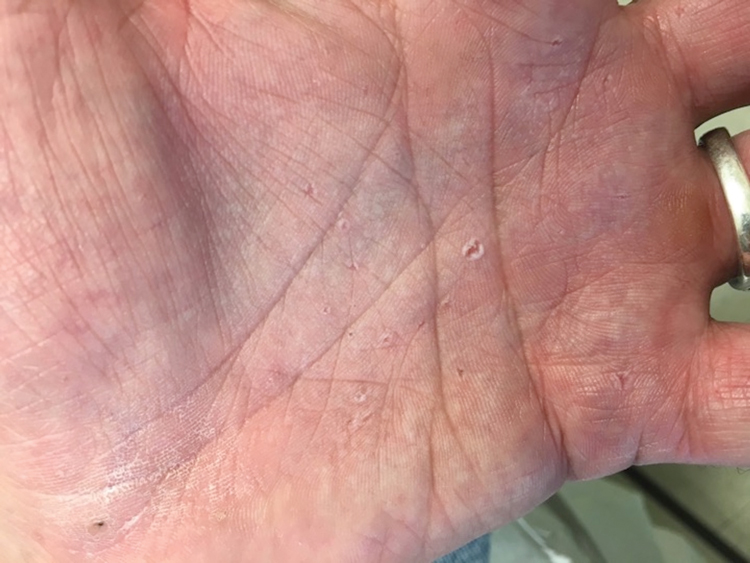

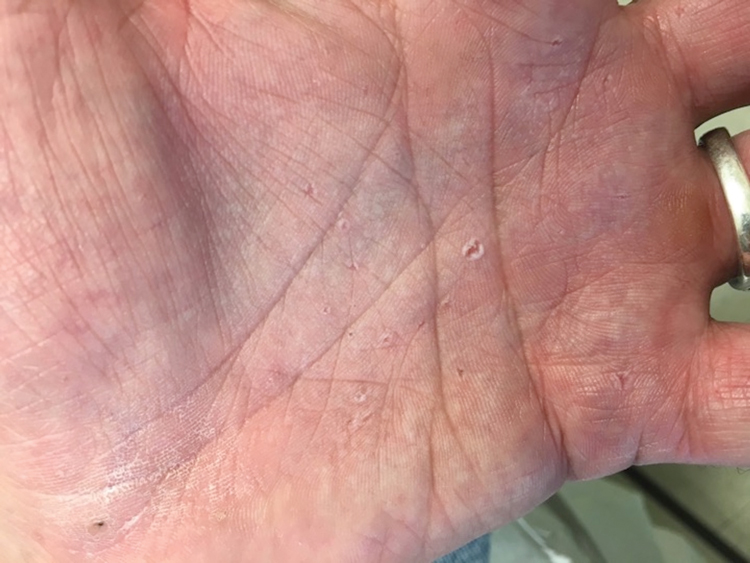

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

The Diagnosis: Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

Given the patient’s history of numerous basal cell carcinomas (BCCs), odontogenic keratocysts, palmar pits, and a nonhealing ulcer, the clinical presentation was highly suggestive of interdigital BCC in the setting of basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS). A shave biopsy was performed revealing islands of basaloid cells with peripheral palisading and a retraction artifact surrounded by fibromyxoid stroma, consistent with nodular and infiltrative BCC (Figure 1).

Basal cell nevus syndrome (also known as Gorlin syndrome) is a rare neurocutaneous syndrome that manifests with multiple BCCs; palmar and plantar pits (Figure 2); central nervous system tumors; and skeletal anomalies including jaw cysts, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and bifid ribs.1 It is an autosomal-dominant condition caused by mutations in the PTCH1 gene, a tumor suppressor gene involved in the Hedgehog signaling pathway.2 Basal cell carcinoma is the most distinctive feature of BCNS, causing notable morbidity. Tumors typically present between puberty and 35 years of age, and patients can have anywhere from a few to thousands of tumors. They rarely become locally aggressive; however, with radiation therapy, proliferation and local invasion may occur within a few years. Therefore, radiotherapy should be avoided in these patients.1

Although the most common sites for BCCs in BCNS are the head, neck, and back, there is a higher rate of occurrence on sun-protected areas in BCNS compared to the general population.3 Our patient presented with interdigital BCC of the foot, which is an extremely rare occurrence. PubMed and Ovid searches using the terms basal cell carcinoma, BCC, foot, interdigital, and nonmelanoma skin cancer revealed only 3 cases of interdigital BCC of the foot. One case was associated with prior surgical trauma, the second presented as a junctional nevus, and the third did not appear to have any associated inciting factors.4-6 Dermatologists need to have a low threshold for biopsy for any unusual nonhealing lesions, especially in the setting of BCNS. Basal cell carcinomas in BCNS cannot be histologically differentiated from sporadic BCCs, and management largely depends on the size, location, recurrence, and number of lesions. Treatment methods range from topical agents to Mohs micrographic surgery.1

Nonhealing lesions of the foot may give an initial clinical impression of infection overlying peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus with the possibility of associated osteomyelitis. Our patient had no clinical history to suggest peripheral vascular disease or diabetes mellitus, and he had palpable dorsalis pedis pulses as well as a normal neurologic examination. Clinicians also may consider fungal infection in the differential diagnosis. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica is a superficial yeast infection described as a well-defined, red, shiny plaque found in chronically wet areas, usually affecting the third or fourth interdigital spaces of the fingers.7 However, the lack of improvement with antibiotics and antifungals argued against bacterial or fungal infection in our patient. Although BCC also is a common feature of Bazex Dupré-Christol syndrome, it also is characterized by follicular atrophoderma, milia, hypohidrosis, and hypotrichosis,8 which were not evident in our patient. Pseudomonas hot foot syndrome is characterized by painful, plantar, erythematous nodules after exposure to ontaminated water that typically is self-limited but does respond to antibiotics for Pseudomonas.9

Our patient underwent Mohs micrographic surgery with a complex repair utilizing a full-thickness skin graft. There were no signs of recurrence at 3-month follow-up, and he was counseled on the importance of sun-protective behaviors along with regular dermatologic follow-up.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

1. Gorlin RJ. Nevoid basal cell (Gorlin) syndrome. Genet Med. 2004; 6:530-539.

2. Bale A. The nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome: genetics and mechanism of carcinogenesis. Cancer Invest. 1997;15:180-186.

3. Goldstein AM, Bale SJ, Peck GL, et al. Sun exposure and basal cell carcinomas in nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:34-41.

4. Silvers SH. Interdigital pedal basal cell carcinoma. Cutis. 1983;31:199-200.

5. Weitzner S. Basal cell carcinoma of toeweb presenting as a junctional nevus. Southwest Med. 1968;49:175.

6. Niwa A, Pimentel E. Basal cell carcinoma in unusual locations. An Bras Dermatol. 2006;81:281-284.

7. Mitchell JH. Erosio interdigitalis blastomycetica. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1922;6:675-679.

8. Kidd A, Carson L, Gregory DW, et al. A Scottish family with Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome: follicular atrophoderma, congenital hypotrichosis, and basal cell carcinoma. J Med Genet. 1996;33:493-497.

9. Yu Y, Cheng AS, Wang L, et al. Hot tub folliculitis or hot hand-foot syndrome caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:596-600.

A 53-year-old man with a history of numerous basal cell carcinomas and odontogenic keratocysts presented with a nonhealing erosion between the left second and third toes of several months’ duration. He was treated empirically with multiple courses of topical and systemic antibiotics as well as antifungals with minimal improvement. Physical examination revealed a 1.2×0.6-cm eroded plaque with rolled borders on the left second toe web; bilateral palmar pits; diffuse actinic damage; and several well-healed surgical scars on the head, neck, and back. Neurologic examination was normal, and dorsalis pedis pulses were equal and palpable bilaterally.