User login

VIDEO: Regionalized STEMI care slashes in-hospital mortality

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – An American Heart Association program aimed at streamlining care of patients with ST-elevation MI resulted in a dramatic near-halving of in-hospital mortality, compared with STEMI patients treated in hospitals not participating in the project, James G. Jollis, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented the results of the STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study, which involved 12 participating metropolitan regions across the United States, 132 percutaneous coronary intervention–capable hospitals, and 946 emergency medical services agencies. The ACCELERATOR 2 program entailed regional implementation of a structured STEMI care plan in which EMS personnel were trained to obtain prehospital ECGs and to activate cardiac catheterization labs prior to hospital arrival, bypassing the emergency department when appropriate.

Key elements of the project, which was part of the AHA’s Mission: Lifeline program, included having participating hospitals measure their performance of key processes and send that information as well as patient outcome data to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s ACTION–Get With The Guidelines registry. The hospitals in turn received quarterly feedback reports containing blinded hospital comparisons.

Dr. Jollis and his coinvestigators worked to obtain buy-in from local stakeholders, organize regional leadership, and help in drafting a central regional STEMI plan featuring prespecified treatment protocols.

The STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study was carried out in 2015-2017, during which 10,730 patients with STEMI were transported directly to participating hospitals with PCI capability.

The primary study outcome was the change from the first to the final quarter of the study in the proportion of EMS-transported patients with a time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab of 90 minutes or less. This improved significantly, from 67% at baseline to 74% in the final quarter. Nine of the 12 participating regions reduced their time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab, and eight reached the national of goal of having 75% of STEMI patients treated within 90 minutes.

The other key time-to-care measures improved, too: At baseline, only 38% of patients had a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of 20 minutes or less; by the final quarter, this figure had climbed to 56%. That’s an important metric, as evidenced by the study finding that in-hospital mortality occurred in 4.5% of patients with a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of more than 20 minutes, compared with 2.2% in those with a time of 20 minutes or less.

Also, the proportion of patients who spent 20 minutes or less in the emergency department improved from 33% to 43%.

In-hospital mortality improved from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter. No similar improvement in in-hospital mortality occurred in a comparison group of 22,651 STEMI patients treated at hospitals not involved in ACCELERATOR 2.

A significant reduction in the rate of in-hospital congestive heart failure occurred in the ACCELERATOR 2 centers, from 7.4% at baseline to 5.0%. In contrast, stroke, cardiogenic shock, and major bleeding rates were unchanged over time.

The ACCELERATOR 2 model of emergency cardiovascular care is designed to be highly generalizable, according to Dr. Jollis.

“This study supports the implementation of regionally coordinated systems across the United States to abort heart attacks, save lives, and enable heart attack victims to return to their families and productive lives,” he said.

The ACCELERATOR 2 operations manual – essentially a blueprint for organizing a regional STEMI system of care – is available gratis.

Dr. Allen, a cardiologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, said the ACCELERATOR 2 model has been successful because it is consistent with a fundamental principle of implementation science as described by Carolyn Clancy, MD, Executive in Charge at the Veterans Health Affairs Administration, who has said it’s a matter of making the right thing to do the easy thing to do.

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, founder of the Get With the Guidelines program, predicted that the success of this program will lead to a ramping up of efforts to regionalize and coordinate STEMI care across the country. “I hope and anticipate that the AHA will take and run with the ACCELERATOR 2 model and adopt this into Mission: Lifeline, hoping to make this the standard approach to further improving care and outcomes in these patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a video interview.

Simultaneous with his presentation at the AHA conference, the results of STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 were published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 14; doi: 0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032446).

The trial was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. Dr. Jollis reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – An American Heart Association program aimed at streamlining care of patients with ST-elevation MI resulted in a dramatic near-halving of in-hospital mortality, compared with STEMI patients treated in hospitals not participating in the project, James G. Jollis, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented the results of the STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study, which involved 12 participating metropolitan regions across the United States, 132 percutaneous coronary intervention–capable hospitals, and 946 emergency medical services agencies. The ACCELERATOR 2 program entailed regional implementation of a structured STEMI care plan in which EMS personnel were trained to obtain prehospital ECGs and to activate cardiac catheterization labs prior to hospital arrival, bypassing the emergency department when appropriate.

Key elements of the project, which was part of the AHA’s Mission: Lifeline program, included having participating hospitals measure their performance of key processes and send that information as well as patient outcome data to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s ACTION–Get With The Guidelines registry. The hospitals in turn received quarterly feedback reports containing blinded hospital comparisons.

Dr. Jollis and his coinvestigators worked to obtain buy-in from local stakeholders, organize regional leadership, and help in drafting a central regional STEMI plan featuring prespecified treatment protocols.

The STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study was carried out in 2015-2017, during which 10,730 patients with STEMI were transported directly to participating hospitals with PCI capability.

The primary study outcome was the change from the first to the final quarter of the study in the proportion of EMS-transported patients with a time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab of 90 minutes or less. This improved significantly, from 67% at baseline to 74% in the final quarter. Nine of the 12 participating regions reduced their time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab, and eight reached the national of goal of having 75% of STEMI patients treated within 90 minutes.

The other key time-to-care measures improved, too: At baseline, only 38% of patients had a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of 20 minutes or less; by the final quarter, this figure had climbed to 56%. That’s an important metric, as evidenced by the study finding that in-hospital mortality occurred in 4.5% of patients with a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of more than 20 minutes, compared with 2.2% in those with a time of 20 minutes or less.

Also, the proportion of patients who spent 20 minutes or less in the emergency department improved from 33% to 43%.

In-hospital mortality improved from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter. No similar improvement in in-hospital mortality occurred in a comparison group of 22,651 STEMI patients treated at hospitals not involved in ACCELERATOR 2.

A significant reduction in the rate of in-hospital congestive heart failure occurred in the ACCELERATOR 2 centers, from 7.4% at baseline to 5.0%. In contrast, stroke, cardiogenic shock, and major bleeding rates were unchanged over time.

The ACCELERATOR 2 model of emergency cardiovascular care is designed to be highly generalizable, according to Dr. Jollis.

“This study supports the implementation of regionally coordinated systems across the United States to abort heart attacks, save lives, and enable heart attack victims to return to their families and productive lives,” he said.

The ACCELERATOR 2 operations manual – essentially a blueprint for organizing a regional STEMI system of care – is available gratis.

Dr. Allen, a cardiologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, said the ACCELERATOR 2 model has been successful because it is consistent with a fundamental principle of implementation science as described by Carolyn Clancy, MD, Executive in Charge at the Veterans Health Affairs Administration, who has said it’s a matter of making the right thing to do the easy thing to do.

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, founder of the Get With the Guidelines program, predicted that the success of this program will lead to a ramping up of efforts to regionalize and coordinate STEMI care across the country. “I hope and anticipate that the AHA will take and run with the ACCELERATOR 2 model and adopt this into Mission: Lifeline, hoping to make this the standard approach to further improving care and outcomes in these patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a video interview.

Simultaneous with his presentation at the AHA conference, the results of STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 were published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 14; doi: 0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032446).

The trial was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. Dr. Jollis reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – An American Heart Association program aimed at streamlining care of patients with ST-elevation MI resulted in a dramatic near-halving of in-hospital mortality, compared with STEMI patients treated in hospitals not participating in the project, James G. Jollis, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

He presented the results of the STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study, which involved 12 participating metropolitan regions across the United States, 132 percutaneous coronary intervention–capable hospitals, and 946 emergency medical services agencies. The ACCELERATOR 2 program entailed regional implementation of a structured STEMI care plan in which EMS personnel were trained to obtain prehospital ECGs and to activate cardiac catheterization labs prior to hospital arrival, bypassing the emergency department when appropriate.

Key elements of the project, which was part of the AHA’s Mission: Lifeline program, included having participating hospitals measure their performance of key processes and send that information as well as patient outcome data to the National Cardiovascular Data Registry’s ACTION–Get With The Guidelines registry. The hospitals in turn received quarterly feedback reports containing blinded hospital comparisons.

Dr. Jollis and his coinvestigators worked to obtain buy-in from local stakeholders, organize regional leadership, and help in drafting a central regional STEMI plan featuring prespecified treatment protocols.

The STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 study was carried out in 2015-2017, during which 10,730 patients with STEMI were transported directly to participating hospitals with PCI capability.

The primary study outcome was the change from the first to the final quarter of the study in the proportion of EMS-transported patients with a time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab of 90 minutes or less. This improved significantly, from 67% at baseline to 74% in the final quarter. Nine of the 12 participating regions reduced their time from first medical contact to treatment in the cath lab, and eight reached the national of goal of having 75% of STEMI patients treated within 90 minutes.

The other key time-to-care measures improved, too: At baseline, only 38% of patients had a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of 20 minutes or less; by the final quarter, this figure had climbed to 56%. That’s an important metric, as evidenced by the study finding that in-hospital mortality occurred in 4.5% of patients with a time from first medical contact to cath lab activation of more than 20 minutes, compared with 2.2% in those with a time of 20 minutes or less.

Also, the proportion of patients who spent 20 minutes or less in the emergency department improved from 33% to 43%.

In-hospital mortality improved from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter. No similar improvement in in-hospital mortality occurred in a comparison group of 22,651 STEMI patients treated at hospitals not involved in ACCELERATOR 2.

A significant reduction in the rate of in-hospital congestive heart failure occurred in the ACCELERATOR 2 centers, from 7.4% at baseline to 5.0%. In contrast, stroke, cardiogenic shock, and major bleeding rates were unchanged over time.

The ACCELERATOR 2 model of emergency cardiovascular care is designed to be highly generalizable, according to Dr. Jollis.

“This study supports the implementation of regionally coordinated systems across the United States to abort heart attacks, save lives, and enable heart attack victims to return to their families and productive lives,” he said.

The ACCELERATOR 2 operations manual – essentially a blueprint for organizing a regional STEMI system of care – is available gratis.

Dr. Allen, a cardiologist at the University of Colorado, Denver, said the ACCELERATOR 2 model has been successful because it is consistent with a fundamental principle of implementation science as described by Carolyn Clancy, MD, Executive in Charge at the Veterans Health Affairs Administration, who has said it’s a matter of making the right thing to do the easy thing to do.

Gregg C. Fonarow, MD, founder of the Get With the Guidelines program, predicted that the success of this program will lead to a ramping up of efforts to regionalize and coordinate STEMI care across the country. “I hope and anticipate that the AHA will take and run with the ACCELERATOR 2 model and adopt this into Mission: Lifeline, hoping to make this the standard approach to further improving care and outcomes in these patients,” said Dr. Fonarow, professor and cochief of cardiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, in a video interview.

Simultaneous with his presentation at the AHA conference, the results of STEMI ACCELERATOR 2 were published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 14; doi: 0.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032446).

The trial was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. Dr. Jollis reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The in-hospital mortality rate of STEMI patients dropped from 4.4% in the baseline quarter to 2.3% in the final quarter of a study that examined the impact of introducing regionalized STEMI care.

Data source: This was a prospective study of an intervention that involved implementation of regionalized STEMI care in a dozen U.S. metropolitan areas.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by research and educational grants from AstraZeneca and The Medicines Company. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest.

Bicarb, acetylcysteine during angiography don’t protect kidneys

Periprocedural administration of intravenous sodium bicarbonate did not improve outcomes compared with standard sodium chloride in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing angiography, according to results of a randomized study of 5,177 patients.

In addition, there was no benefit for oral acetylcysteine administration over placebo for mitigating those same postangiography risks, Steven D. Weisbord, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Anaheim, Calif.

Hypothetically, both sodium bicarbonate and acetylcysteine could help prevent acute kidney injury associated with contrast material used during angiography, said Dr. Weisbord of the University of Pittsburgh.

However, multiple studies of the two agents have yielded “inconsistent results … consequently, equipoise exists regarding these interventions, despite their widespread use in clinical practice,” Dr. Weisbord said.

To provide more definitive evidence, Dr. Weisbord and his colleagues conducted PRESERVE, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comprising 5,177 patients scheduled for angiography who were at high risk of renal complications. Using a 2-by-2 factorial design, patients were randomized to receive intravenous 1.26% sodium bicarbonate or intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride, and to 5 days of oral acetylcysteine or oral placebo.

They found no significant differences between arms in the study’s composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine by 50% or more.

That composite endpoint occurred in 4.4% of patients receiving sodium bicarbonate, and similarly in 4.7% of patients receiving sodium chloride.

Likewise, the endpoint occurred in 4.6% of patients in the acetylcysteine group and 4.5% of the placebo group, Dr. Weisbord reported.

The investigators had planned to enroll 7,680 patients, but the sponsor of the trial stopped the study after enrollment of 5,177 based on the results showing no significant benefit of either treatment, he noted.

There are a few reasons why results of PRESERVE might show a lack of benefit for these agents, in contrast to some previous studies suggesting both the treatments might reduce risk of contrast-associated renal complications in high-risk patients.

Notably, “most of these interventions have been underpowered,” Dr. Weisbord noted.

Also, most previous trials used a primary endpoint of increase in blood creatinine level within days of the angiography. By contrast, the primary endpoint of the current study was a composite of serious adverse events “that are recognized sequelae of acute kidney injury,” he added.

Although subsequent investigations could shed new light on the controversy, the findings of PRESERVE support the “strong likelihood that these interventions are not clinically effective” in preventing acute kidney injury or longer-term adverse outcomes after angiography, he concluded.

The PRESERVE results were published simultaneously with Dr. Weisbord’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710933).

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

Periprocedural administration of intravenous sodium bicarbonate did not improve outcomes compared with standard sodium chloride in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing angiography, according to results of a randomized study of 5,177 patients.

In addition, there was no benefit for oral acetylcysteine administration over placebo for mitigating those same postangiography risks, Steven D. Weisbord, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Anaheim, Calif.

Hypothetically, both sodium bicarbonate and acetylcysteine could help prevent acute kidney injury associated with contrast material used during angiography, said Dr. Weisbord of the University of Pittsburgh.

However, multiple studies of the two agents have yielded “inconsistent results … consequently, equipoise exists regarding these interventions, despite their widespread use in clinical practice,” Dr. Weisbord said.

To provide more definitive evidence, Dr. Weisbord and his colleagues conducted PRESERVE, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comprising 5,177 patients scheduled for angiography who were at high risk of renal complications. Using a 2-by-2 factorial design, patients were randomized to receive intravenous 1.26% sodium bicarbonate or intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride, and to 5 days of oral acetylcysteine or oral placebo.

They found no significant differences between arms in the study’s composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine by 50% or more.

That composite endpoint occurred in 4.4% of patients receiving sodium bicarbonate, and similarly in 4.7% of patients receiving sodium chloride.

Likewise, the endpoint occurred in 4.6% of patients in the acetylcysteine group and 4.5% of the placebo group, Dr. Weisbord reported.

The investigators had planned to enroll 7,680 patients, but the sponsor of the trial stopped the study after enrollment of 5,177 based on the results showing no significant benefit of either treatment, he noted.

There are a few reasons why results of PRESERVE might show a lack of benefit for these agents, in contrast to some previous studies suggesting both the treatments might reduce risk of contrast-associated renal complications in high-risk patients.

Notably, “most of these interventions have been underpowered,” Dr. Weisbord noted.

Also, most previous trials used a primary endpoint of increase in blood creatinine level within days of the angiography. By contrast, the primary endpoint of the current study was a composite of serious adverse events “that are recognized sequelae of acute kidney injury,” he added.

Although subsequent investigations could shed new light on the controversy, the findings of PRESERVE support the “strong likelihood that these interventions are not clinically effective” in preventing acute kidney injury or longer-term adverse outcomes after angiography, he concluded.

The PRESERVE results were published simultaneously with Dr. Weisbord’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710933).

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

Periprocedural administration of intravenous sodium bicarbonate did not improve outcomes compared with standard sodium chloride in patients with impaired kidney function undergoing angiography, according to results of a randomized study of 5,177 patients.

In addition, there was no benefit for oral acetylcysteine administration over placebo for mitigating those same postangiography risks, Steven D. Weisbord, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions in Anaheim, Calif.

Hypothetically, both sodium bicarbonate and acetylcysteine could help prevent acute kidney injury associated with contrast material used during angiography, said Dr. Weisbord of the University of Pittsburgh.

However, multiple studies of the two agents have yielded “inconsistent results … consequently, equipoise exists regarding these interventions, despite their widespread use in clinical practice,” Dr. Weisbord said.

To provide more definitive evidence, Dr. Weisbord and his colleagues conducted PRESERVE, a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial comprising 5,177 patients scheduled for angiography who were at high risk of renal complications. Using a 2-by-2 factorial design, patients were randomized to receive intravenous 1.26% sodium bicarbonate or intravenous 0.9% sodium chloride, and to 5 days of oral acetylcysteine or oral placebo.

They found no significant differences between arms in the study’s composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine by 50% or more.

That composite endpoint occurred in 4.4% of patients receiving sodium bicarbonate, and similarly in 4.7% of patients receiving sodium chloride.

Likewise, the endpoint occurred in 4.6% of patients in the acetylcysteine group and 4.5% of the placebo group, Dr. Weisbord reported.

The investigators had planned to enroll 7,680 patients, but the sponsor of the trial stopped the study after enrollment of 5,177 based on the results showing no significant benefit of either treatment, he noted.

There are a few reasons why results of PRESERVE might show a lack of benefit for these agents, in contrast to some previous studies suggesting both the treatments might reduce risk of contrast-associated renal complications in high-risk patients.

Notably, “most of these interventions have been underpowered,” Dr. Weisbord noted.

Also, most previous trials used a primary endpoint of increase in blood creatinine level within days of the angiography. By contrast, the primary endpoint of the current study was a composite of serious adverse events “that are recognized sequelae of acute kidney injury,” he added.

Although subsequent investigations could shed new light on the controversy, the findings of PRESERVE support the “strong likelihood that these interventions are not clinically effective” in preventing acute kidney injury or longer-term adverse outcomes after angiography, he concluded.

The PRESERVE results were published simultaneously with Dr. Weisbord’s presentation (N Engl J Med. 2017 Nov 12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1710933).

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The composite primary endpoint of death, need for dialysis, or persistent increase in serum creatinine was similar regardless of which treatments the patients received.

Data source: PRESERVE, a randomized study using a 2-by-2 factorial design to evaluate intravenous sodium bicarbonate versus sodium chloride and acetylcysteine versus placebo in 5,177 patients at high risk of renal complications.

Disclosures: PRESERVE was supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. Dr. Weisbord reported receiving personal fees from Durect outside the submitted work.

VIDEO: U.S. hypertension guidelines reset threshold to 130/80 mm Hg

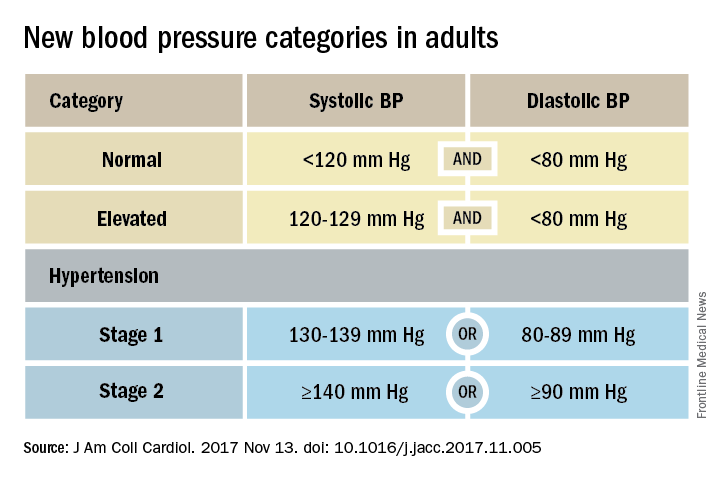

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

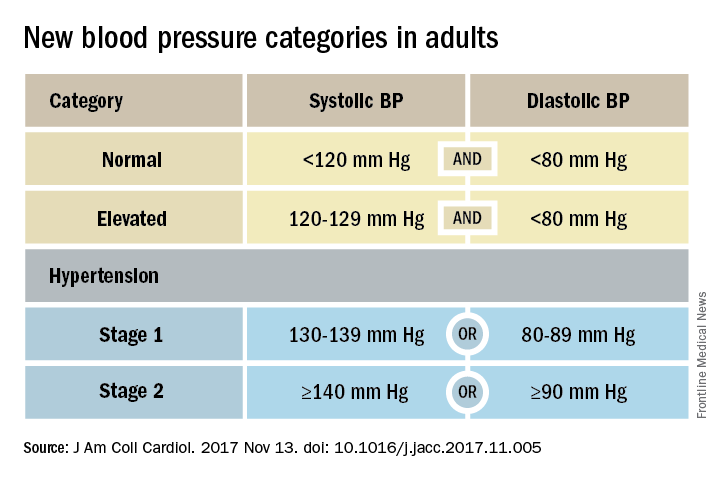

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

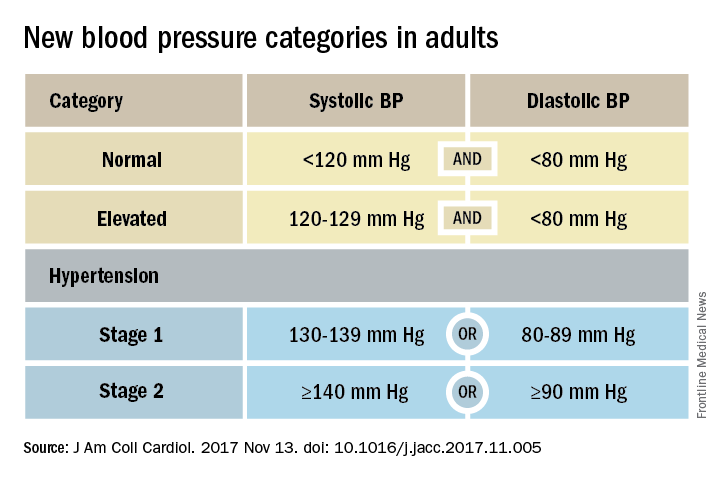

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Thirty million Americans became hypertensive overnight on Nov. 13 with the introduction of new high blood pressure guidelines from the American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association.

That happened by resetting the definition of adult hypertension from the long-standing threshold of 140/90 mm Hg to a blood pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, a change that jumps the U.S. adult prevalence of hypertension from roughly 32% to 46%. Nearly half of all U.S. adults now have hypertension, bringing the total national hypertensive population to a staggering 103 million.

Goal is to transform care

But the new guidelines (J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Nov 13. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.005) for preventing, detecting, evaluating, and managing adult hypertension do lots more than just shake up the epidemiology of high blood pressure. With 106 total recommendations, the guidelines seek to transform every aspect of blood pressure in American medical practice, starting with how it’s measured and stretching to redefine applications of medical systems to try to ensure that every person with a blood pressure that truly falls outside the redefined limits gets a comprehensive package of interventions.

Many of these are “seismic changes,” said Lawrence J. Appel, MD. He particularly cited as seismic the new classification of stage 1 hypertension as a pressure at or above 130/80 mm Hg, the emphasis on using some form of out-of-office blood pressure measurement to confirm a diagnosis, the use of risk assessment when deciding whether to treat certain patients with drugs, and the same blood pressure goal of less than 130/80 mm Hg for all hypertensives, regardless of age, as long as they remain ambulatory and community dwelling.

One goal for all adults

“The systolic blood pressure goal for older people has gone from 140 mm Hg to 150 mm Hg and now to 130 mm Hg in the space of 2-3 years,” commented Dr. Appel, professor of epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore and not involved in the guideline-writing process.

In fact, the guidelines simplified the treatment goal all around, to less than 130/80 mm Hg for patients with diabetes, those with chronic kidney disease, and the elderly; that goal remains the same for all adults.

“It will be clearer and easier now that everyone should be less than 130/80 mm Hg. You won’t need to remember a second target,” said Sandra J. Taler, MD, a nephrologist and professor of medicine at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and a member of the guidelines task force.

“Some people may be upset that we changed the rules on them. They had normal blood pressure yesterday, and today it’s high. But it’s a good awakening, especially for using lifestyle interventions,” Dr. Taler said in an interview.

Preferred intervention: Lifestyle, not drugs

Lifestyle optimization is repeatedly cited as the cornerstone of intervention for everyone, including those with elevated blood pressure with a systolic pressure of 120-129 mm Hg, and as the only endorsed intervention for patients with hypertension of 130-139 mm Hg but below a 10% risk for a cardiovascular disease event during the next 10 years on the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator. The guidelines list six lifestyle goals: weight loss, following a DASH diet, reducing sodium, enhancing potassium, 90-150 min/wk of physical activity, and moderate alcohol intake.

Team-based care essential

The guidelines also put unprecedented emphasis on using a team-based management approach, which means having nurses, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, dietitians, and other clinicians, allowing for more frequent and focused care. Dr. Whelton and others cited in particular the VA Health System and Kaiser-Permanente as operating team-based and system-driven blood pressure management programs that have resulted in control rates for more than 90% of hypertensive patients. The team-based approach is also a key in the Target:BP program that the American Heart Association and American Medical Association founded. Target:BP will be instrumental in promoting implementation of the new guidelines, Dr. Carey said. Another systems recommendation is that every patient with hypertension should have a “clear, detailed, and current evidence-based plan of care.”

“Using nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and pharmacists has been shown to improve blood pressure levels,” and health systems that use this approach have had “great success,” commented Donald M. Lloyd-Jones, MD, professor and chairman of preventive medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago and not part of the guidelines task force. Some systems have used this approach to achieve high levels of blood pressure control. Now that financial penalties and incentives from payers also exist to push for higher levels of blood pressure control, the alignment of financial and health incentives should result in big changes, Dr. Lloyd-Jones predicted in a video interview.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Targeting PCSK9 inhibitors to reap most benefit

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease or a high-risk history of MI got the biggest bang for the buck from aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering with evolocumab in two new prespecified subgroup analyses from the landmark FOURIER trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“At the end of the day, not all of our patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] can have these expensive medications. These subgroup analyses will help clinicians to target use of PCSK9 inhibitors to the patients who will benefit the most,” Lynne T. Braun, PhD, commented in her role as discussant of the two secondary analyses, presented back to back in a late-breaking science session. Dr. Braun is a professor in the department of internal medicine at Rush University, Chicago.

The FOURIER trial included 27,564 high-risk patients with prior MI, stroke, and/or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) who had an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL or more on high- or moderate-intensity statin therapy. They were randomized in double-blind fashion to add-on subcutaneous evolocumab (Repatha) at either 140 mg every 2 weeks or 420 mg/month or to placebo, for a median of 2.5 years of follow-up. The evolocumab group experienced a 59% reduction in LDL cholesterol, compared with the controls on background statin therapy plus placebo, down to a mean LDL cholesterol level of just 30 mg/dL.

As previously reported, the risk of the primary composite endpoint – comprising cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, unstable angina, or coronary revascularization – was reduced by 15% in the evolocumab group at 3 years. The secondary endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke was reduced by 20%, from 9.9% to 7.9% (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-22).

Evolocumab tamed PAD

At the AHA scientific sessions, Marc P. Bonaca, MD, presented a secondary analysis restricted to the 3,642 FOURIER participants with symptomatic PAD. The goal was to answer two unresolved questions: Does LDL cholesterol lowering beyond what’s achievable with a statin further reduce PAD patients’ cardiovascular risk? And does it reduce their risk of major adverse leg events (MALE), defined as a composite of acute limb ischemia, major amputation, and urgent revascularization?

The rate of the composite endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke was 13% over 3 years in PAD patients randomized to placebo, which was 81% greater than the 7.6% rate in placebo-treated participants with a baseline history of stroke or MI but no PAD, in an analysis adjusted for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, kidney function, body mass index, and prior revascularization.

The event rate was even higher in patients with PAD plus a history of MI or stroke, at 14.9%. Evolocumab reduced that risk by 27%, compared with placebo in patients with PAD, for an absolute risk reduction of 3.5% and a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 29 for 2.5 years.

The benefit of evolocumab was even more pronounced in the subgroup of 1,505 patients with baseline PAD but no prior MI or stroke: a 43% relative risk reduction, from 10.3% to 5.5%, for an absolute risk reduction of 4.8% and a NNT of 21.

A linear relationship was seen between the MALE rate during follow-up and LDL cholesterol level after 1 month of therapy, down to an LDL cholesterol level of less than 10 mg/dL. The clinically relevant composite endpoint of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events – a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke) or MALE in patients with baseline PAD but no history of MI or stroke occurred in 12.8% of controls and 6.5% of the evolocumab group. This translated to a 48% relative risk reduction, a 6.3% absolute risk reduction, and a NNT of 16. The event curves in the evolocumab and control arms separated quite early, within the first 90 days of treatment.

The take home message: “LDL reduction to very low levels should be considered in patients with PAD, regardless of their history of MI or stroke, to reduce the risk of MACE [major adverse cardiovascular event] and MALE,” declared Dr. Bonaca of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Spotting the patients with a history of MI who’re at highest risk

Marc S. Sabatine, MD, presented the subanalysis involving the 22,351 FOURIER patients with a prior MI. He and his coinvestigators identified three high-risk features within this group: an MI within the past 2 years, a history of two or more MIs, and residual multivessel CAD. Each of these three features was individually associated with a 34%-90% increased risk of MACE during follow-up. All told, 63% of FOURIER participants with prior MI had one or more of the high-risk features.

The use of evolocumab in patients with at least one of the three high-risk features was associated with a 22% relative risk reduction and an absolute 2.5% risk reduction, compared with placebo. The event curves diverged at about 6 months, and the gap between them steadily widened during follow-up. Extrapolating from this pattern, it’s likely that evolocumab would achieve an absolute 5% risk reduction in MACE, compared with placebo over 5 years, with an NNT of 20, according to Dr. Sabatine, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chairman of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group.

Lingering questions

Dr. Braun was particularly impressed that the absolute risk reduction in MACE was even larger in patients with baseline PAD but no history of stroke or MI than in PAD patients with such a history. She added that, while she recognizes the value of selecting objectively assessable hard clinical MACE as the primary endpoint in FOURIER, her own patients care even more about other outcomes.

“What my patients with PAD care most about is whether profound LDL lowering translates to less claudication, improved quality of life, and greater physical activity tolerance. These were prespecified secondary outcomes in FOURIER, and I look forward to future reports addressing those issues,” she said.

Another unanswered question involves the mechanism by which intensive LDL cholesterol lowering results in fewer MACE and MALE events in high-risk subgroups. The possibilities include the plaque regression that was documented in the GLAGOV trial, an anti-inflammatory plaque-stabilizing effect being exerted through PCSK9 inhibition, or perhaps the PCSK9 inhibitors’ ability to moderately lower lipoprotein(a) cholesterol levels.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bonaca’s presentation at the AHA, the FOURIER PAD analysis was published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 13; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032235).

The FOURIER trial was sponsored by Amgen. Dr. Bonaca and Dr. Sabatine reported receiving research grants from and serving as consultants to Amgen and other companies.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease or a high-risk history of MI got the biggest bang for the buck from aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering with evolocumab in two new prespecified subgroup analyses from the landmark FOURIER trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“At the end of the day, not all of our patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] can have these expensive medications. These subgroup analyses will help clinicians to target use of PCSK9 inhibitors to the patients who will benefit the most,” Lynne T. Braun, PhD, commented in her role as discussant of the two secondary analyses, presented back to back in a late-breaking science session. Dr. Braun is a professor in the department of internal medicine at Rush University, Chicago.

The FOURIER trial included 27,564 high-risk patients with prior MI, stroke, and/or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) who had an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL or more on high- or moderate-intensity statin therapy. They were randomized in double-blind fashion to add-on subcutaneous evolocumab (Repatha) at either 140 mg every 2 weeks or 420 mg/month or to placebo, for a median of 2.5 years of follow-up. The evolocumab group experienced a 59% reduction in LDL cholesterol, compared with the controls on background statin therapy plus placebo, down to a mean LDL cholesterol level of just 30 mg/dL.

As previously reported, the risk of the primary composite endpoint – comprising cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, unstable angina, or coronary revascularization – was reduced by 15% in the evolocumab group at 3 years. The secondary endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke was reduced by 20%, from 9.9% to 7.9% (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-22).

Evolocumab tamed PAD

At the AHA scientific sessions, Marc P. Bonaca, MD, presented a secondary analysis restricted to the 3,642 FOURIER participants with symptomatic PAD. The goal was to answer two unresolved questions: Does LDL cholesterol lowering beyond what’s achievable with a statin further reduce PAD patients’ cardiovascular risk? And does it reduce their risk of major adverse leg events (MALE), defined as a composite of acute limb ischemia, major amputation, and urgent revascularization?

The rate of the composite endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke was 13% over 3 years in PAD patients randomized to placebo, which was 81% greater than the 7.6% rate in placebo-treated participants with a baseline history of stroke or MI but no PAD, in an analysis adjusted for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, kidney function, body mass index, and prior revascularization.

The event rate was even higher in patients with PAD plus a history of MI or stroke, at 14.9%. Evolocumab reduced that risk by 27%, compared with placebo in patients with PAD, for an absolute risk reduction of 3.5% and a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 29 for 2.5 years.

The benefit of evolocumab was even more pronounced in the subgroup of 1,505 patients with baseline PAD but no prior MI or stroke: a 43% relative risk reduction, from 10.3% to 5.5%, for an absolute risk reduction of 4.8% and a NNT of 21.

A linear relationship was seen between the MALE rate during follow-up and LDL cholesterol level after 1 month of therapy, down to an LDL cholesterol level of less than 10 mg/dL. The clinically relevant composite endpoint of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events – a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke) or MALE in patients with baseline PAD but no history of MI or stroke occurred in 12.8% of controls and 6.5% of the evolocumab group. This translated to a 48% relative risk reduction, a 6.3% absolute risk reduction, and a NNT of 16. The event curves in the evolocumab and control arms separated quite early, within the first 90 days of treatment.

The take home message: “LDL reduction to very low levels should be considered in patients with PAD, regardless of their history of MI or stroke, to reduce the risk of MACE [major adverse cardiovascular event] and MALE,” declared Dr. Bonaca of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Spotting the patients with a history of MI who’re at highest risk

Marc S. Sabatine, MD, presented the subanalysis involving the 22,351 FOURIER patients with a prior MI. He and his coinvestigators identified three high-risk features within this group: an MI within the past 2 years, a history of two or more MIs, and residual multivessel CAD. Each of these three features was individually associated with a 34%-90% increased risk of MACE during follow-up. All told, 63% of FOURIER participants with prior MI had one or more of the high-risk features.

The use of evolocumab in patients with at least one of the three high-risk features was associated with a 22% relative risk reduction and an absolute 2.5% risk reduction, compared with placebo. The event curves diverged at about 6 months, and the gap between them steadily widened during follow-up. Extrapolating from this pattern, it’s likely that evolocumab would achieve an absolute 5% risk reduction in MACE, compared with placebo over 5 years, with an NNT of 20, according to Dr. Sabatine, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chairman of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group.

Lingering questions

Dr. Braun was particularly impressed that the absolute risk reduction in MACE was even larger in patients with baseline PAD but no history of stroke or MI than in PAD patients with such a history. She added that, while she recognizes the value of selecting objectively assessable hard clinical MACE as the primary endpoint in FOURIER, her own patients care even more about other outcomes.

“What my patients with PAD care most about is whether profound LDL lowering translates to less claudication, improved quality of life, and greater physical activity tolerance. These were prespecified secondary outcomes in FOURIER, and I look forward to future reports addressing those issues,” she said.

Another unanswered question involves the mechanism by which intensive LDL cholesterol lowering results in fewer MACE and MALE events in high-risk subgroups. The possibilities include the plaque regression that was documented in the GLAGOV trial, an anti-inflammatory plaque-stabilizing effect being exerted through PCSK9 inhibition, or perhaps the PCSK9 inhibitors’ ability to moderately lower lipoprotein(a) cholesterol levels.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bonaca’s presentation at the AHA, the FOURIER PAD analysis was published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 13; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032235).

The FOURIER trial was sponsored by Amgen. Dr. Bonaca and Dr. Sabatine reported receiving research grants from and serving as consultants to Amgen and other companies.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Patients with symptomatic peripheral artery disease or a high-risk history of MI got the biggest bang for the buck from aggressive LDL cholesterol lowering with evolocumab in two new prespecified subgroup analyses from the landmark FOURIER trial presented at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“At the end of the day, not all of our patients with ASCVD [atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease] can have these expensive medications. These subgroup analyses will help clinicians to target use of PCSK9 inhibitors to the patients who will benefit the most,” Lynne T. Braun, PhD, commented in her role as discussant of the two secondary analyses, presented back to back in a late-breaking science session. Dr. Braun is a professor in the department of internal medicine at Rush University, Chicago.

The FOURIER trial included 27,564 high-risk patients with prior MI, stroke, and/or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease (PAD) who had an LDL cholesterol level of 70 mg/dL or more on high- or moderate-intensity statin therapy. They were randomized in double-blind fashion to add-on subcutaneous evolocumab (Repatha) at either 140 mg every 2 weeks or 420 mg/month or to placebo, for a median of 2.5 years of follow-up. The evolocumab group experienced a 59% reduction in LDL cholesterol, compared with the controls on background statin therapy plus placebo, down to a mean LDL cholesterol level of just 30 mg/dL.

As previously reported, the risk of the primary composite endpoint – comprising cardiovascular death, MI, stroke, unstable angina, or coronary revascularization – was reduced by 15% in the evolocumab group at 3 years. The secondary endpoint of cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke was reduced by 20%, from 9.9% to 7.9% (N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-22).

Evolocumab tamed PAD

At the AHA scientific sessions, Marc P. Bonaca, MD, presented a secondary analysis restricted to the 3,642 FOURIER participants with symptomatic PAD. The goal was to answer two unresolved questions: Does LDL cholesterol lowering beyond what’s achievable with a statin further reduce PAD patients’ cardiovascular risk? And does it reduce their risk of major adverse leg events (MALE), defined as a composite of acute limb ischemia, major amputation, and urgent revascularization?

The rate of the composite endpoint comprising cardiovascular death, MI, or stroke was 13% over 3 years in PAD patients randomized to placebo, which was 81% greater than the 7.6% rate in placebo-treated participants with a baseline history of stroke or MI but no PAD, in an analysis adjusted for demographics, cardiovascular risk factors, kidney function, body mass index, and prior revascularization.

The event rate was even higher in patients with PAD plus a history of MI or stroke, at 14.9%. Evolocumab reduced that risk by 27%, compared with placebo in patients with PAD, for an absolute risk reduction of 3.5% and a number-needed-to-treat (NNT) of 29 for 2.5 years.

The benefit of evolocumab was even more pronounced in the subgroup of 1,505 patients with baseline PAD but no prior MI or stroke: a 43% relative risk reduction, from 10.3% to 5.5%, for an absolute risk reduction of 4.8% and a NNT of 21.

A linear relationship was seen between the MALE rate during follow-up and LDL cholesterol level after 1 month of therapy, down to an LDL cholesterol level of less than 10 mg/dL. The clinically relevant composite endpoint of MACE (major adverse cardiovascular events – a composite of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke) or MALE in patients with baseline PAD but no history of MI or stroke occurred in 12.8% of controls and 6.5% of the evolocumab group. This translated to a 48% relative risk reduction, a 6.3% absolute risk reduction, and a NNT of 16. The event curves in the evolocumab and control arms separated quite early, within the first 90 days of treatment.

The take home message: “LDL reduction to very low levels should be considered in patients with PAD, regardless of their history of MI or stroke, to reduce the risk of MACE [major adverse cardiovascular event] and MALE,” declared Dr. Bonaca of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

Spotting the patients with a history of MI who’re at highest risk

Marc S. Sabatine, MD, presented the subanalysis involving the 22,351 FOURIER patients with a prior MI. He and his coinvestigators identified three high-risk features within this group: an MI within the past 2 years, a history of two or more MIs, and residual multivessel CAD. Each of these three features was individually associated with a 34%-90% increased risk of MACE during follow-up. All told, 63% of FOURIER participants with prior MI had one or more of the high-risk features.

The use of evolocumab in patients with at least one of the three high-risk features was associated with a 22% relative risk reduction and an absolute 2.5% risk reduction, compared with placebo. The event curves diverged at about 6 months, and the gap between them steadily widened during follow-up. Extrapolating from this pattern, it’s likely that evolocumab would achieve an absolute 5% risk reduction in MACE, compared with placebo over 5 years, with an NNT of 20, according to Dr. Sabatine, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and chairman of the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) Study Group.

Lingering questions

Dr. Braun was particularly impressed that the absolute risk reduction in MACE was even larger in patients with baseline PAD but no history of stroke or MI than in PAD patients with such a history. She added that, while she recognizes the value of selecting objectively assessable hard clinical MACE as the primary endpoint in FOURIER, her own patients care even more about other outcomes.

“What my patients with PAD care most about is whether profound LDL lowering translates to less claudication, improved quality of life, and greater physical activity tolerance. These were prespecified secondary outcomes in FOURIER, and I look forward to future reports addressing those issues,” she said.

Another unanswered question involves the mechanism by which intensive LDL cholesterol lowering results in fewer MACE and MALE events in high-risk subgroups. The possibilities include the plaque regression that was documented in the GLAGOV trial, an anti-inflammatory plaque-stabilizing effect being exerted through PCSK9 inhibition, or perhaps the PCSK9 inhibitors’ ability to moderately lower lipoprotein(a) cholesterol levels.

Simultaneous with Dr. Bonaca’s presentation at the AHA, the FOURIER PAD analysis was published online in Circulation (2017 Nov 13; doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.032235).

The FOURIER trial was sponsored by Amgen. Dr. Bonaca and Dr. Sabatine reported receiving research grants from and serving as consultants to Amgen and other companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Direct oral anticoagulants okay during AF device placement

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Whether direct oral anticoagulants are continued or interrupted for device placement in atrial fibrillation patients, the risk of device pocket hematoma or stroke is very low, based on results of the BRUISE CONTROL–2 trial in more than 600 subjects.

Either strategy is reasonable depending on the clinical scenario, coprincipal investigator David Birnie, MD, said in presenting the results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

When atrial fibrillation (AF) patients on direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) present for device surgery, there’s concern that keeping them on the drugs will increase the bleeding risk, but that taking them off will increase the stroke risk. “We sought to resolve this dilemma,” said Dr. Birnie, an electrophysiologist and director of the arrhythmia service at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute.

The subjects were on dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban, about a third in each group; 328 were randomized to continue their daily dosing, including on the day of surgery. The other 334 were randomized to interrupted treatment. For rivaroxaban and apixaban, that meant taking their last dose 2 days before surgery. Dabigatran patients discontinued the drug 1-2 days beforehand, depending on glomerular filtration rate. Patients resumed treatment about 24 hours after surgery. CHA2DS2-VASc scores were a mean of 3.9 in both arms, and at least 2 in all participants.

The rate of clinically significant hematoma – the primary outcome in the study, defined as a hematoma requiring prolonged hospitalization, interrupted postoperative anticoagulation, or reoperation to evacuate – was identical in both arms, 2.1% (seven patients each). There were two ischemic strokes, one in each arm. There was one delayed cardiac tamponade in the continuation arm and one pericardial effusion in the interrupted arm. The three deaths in the trial were not related to device placement.

So, what to do depends on the clinical scenario, Dr. Birnie said in an interview. If someone needs urgent placement and there’s no time to wait for DOAC washout, “it’s quite reasonable to go ahead.” Also, “if somebody is at extremely high risk for stroke, then it’s very reasonable to continue the drug.”

On the other hand, “if someone has a much lower stroke risk, then the risk-benefit ratio is probably in the opposite direction, so temporarily discontinuing the drug is the right thing to do,” he said.

Dr. Birnie cautioned that although continued DOAC may reduce the risk of thromboembolism, “this study was not designed with power to answer this.”

“We are already putting these findings into practice” in Ottawa, he said. “Our protocol” – as in many places – “ was always to stop anticoagulation for 2 or 3 days, but now, for very high-risk patients – high-risk AF, unstable temporary pacing, that type of thing – we are very comfortable continuing it,” he said. The study follows up a previous randomized trial by Dr. Birnie and his colleagues that pitted continued warfarin against heparin bridging for AF device placement. There were far fewer device pocket hematomas with uninterrupted warfarin (N Engl J Med. 2013 May 30;368[22]:2084-93).

The team wanted to repeat the study using DOACs, since their use has grown substantially, with the majority of AF patients now on them.

The arms in BRUISE CONTROL–2 (Strategy of Continued Versus Interrupted Novel Oral Anticoagulant at Time of Device Surgery in Patients With Moderate to High Risk of Arterial Thromboembolic Events) were well matched, with a mean age of about 74 years; men made up more than 70% of the subjects in both arms. About 17% of the participants were on chronic aspirin therapy and about 4% were on clopidogrel, in each arm. The uninterrupted DOAC group went about 14 hours between their last preop and first postop DOAC dose. The interrupted group went about 72 hours.

BRUISE CONTROL–2 was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others. Dr. Birnie had no relevant financial disclosures.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Whether direct oral anticoagulants are continued or interrupted for device placement in atrial fibrillation patients, the risk of device pocket hematoma or stroke is very low, based on results of the BRUISE CONTROL–2 trial in more than 600 subjects.

Either strategy is reasonable depending on the clinical scenario, coprincipal investigator David Birnie, MD, said in presenting the results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

When atrial fibrillation (AF) patients on direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) present for device surgery, there’s concern that keeping them on the drugs will increase the bleeding risk, but that taking them off will increase the stroke risk. “We sought to resolve this dilemma,” said Dr. Birnie, an electrophysiologist and director of the arrhythmia service at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute.

The subjects were on dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban, about a third in each group; 328 were randomized to continue their daily dosing, including on the day of surgery. The other 334 were randomized to interrupted treatment. For rivaroxaban and apixaban, that meant taking their last dose 2 days before surgery. Dabigatran patients discontinued the drug 1-2 days beforehand, depending on glomerular filtration rate. Patients resumed treatment about 24 hours after surgery. CHA2DS2-VASc scores were a mean of 3.9 in both arms, and at least 2 in all participants.

The rate of clinically significant hematoma – the primary outcome in the study, defined as a hematoma requiring prolonged hospitalization, interrupted postoperative anticoagulation, or reoperation to evacuate – was identical in both arms, 2.1% (seven patients each). There were two ischemic strokes, one in each arm. There was one delayed cardiac tamponade in the continuation arm and one pericardial effusion in the interrupted arm. The three deaths in the trial were not related to device placement.

So, what to do depends on the clinical scenario, Dr. Birnie said in an interview. If someone needs urgent placement and there’s no time to wait for DOAC washout, “it’s quite reasonable to go ahead.” Also, “if somebody is at extremely high risk for stroke, then it’s very reasonable to continue the drug.”

On the other hand, “if someone has a much lower stroke risk, then the risk-benefit ratio is probably in the opposite direction, so temporarily discontinuing the drug is the right thing to do,” he said.

Dr. Birnie cautioned that although continued DOAC may reduce the risk of thromboembolism, “this study was not designed with power to answer this.”

“We are already putting these findings into practice” in Ottawa, he said. “Our protocol” – as in many places – “ was always to stop anticoagulation for 2 or 3 days, but now, for very high-risk patients – high-risk AF, unstable temporary pacing, that type of thing – we are very comfortable continuing it,” he said. The study follows up a previous randomized trial by Dr. Birnie and his colleagues that pitted continued warfarin against heparin bridging for AF device placement. There were far fewer device pocket hematomas with uninterrupted warfarin (N Engl J Med. 2013 May 30;368[22]:2084-93).

The team wanted to repeat the study using DOACs, since their use has grown substantially, with the majority of AF patients now on them.

The arms in BRUISE CONTROL–2 (Strategy of Continued Versus Interrupted Novel Oral Anticoagulant at Time of Device Surgery in Patients With Moderate to High Risk of Arterial Thromboembolic Events) were well matched, with a mean age of about 74 years; men made up more than 70% of the subjects in both arms. About 17% of the participants were on chronic aspirin therapy and about 4% were on clopidogrel, in each arm. The uninterrupted DOAC group went about 14 hours between their last preop and first postop DOAC dose. The interrupted group went about 72 hours.

BRUISE CONTROL–2 was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others. Dr. Birnie had no relevant financial disclosures.

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Whether direct oral anticoagulants are continued or interrupted for device placement in atrial fibrillation patients, the risk of device pocket hematoma or stroke is very low, based on results of the BRUISE CONTROL–2 trial in more than 600 subjects.

Either strategy is reasonable depending on the clinical scenario, coprincipal investigator David Birnie, MD, said in presenting the results at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

When atrial fibrillation (AF) patients on direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) present for device surgery, there’s concern that keeping them on the drugs will increase the bleeding risk, but that taking them off will increase the stroke risk. “We sought to resolve this dilemma,” said Dr. Birnie, an electrophysiologist and director of the arrhythmia service at the University of Ottawa Heart Institute.

The subjects were on dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or apixaban, about a third in each group; 328 were randomized to continue their daily dosing, including on the day of surgery. The other 334 were randomized to interrupted treatment. For rivaroxaban and apixaban, that meant taking their last dose 2 days before surgery. Dabigatran patients discontinued the drug 1-2 days beforehand, depending on glomerular filtration rate. Patients resumed treatment about 24 hours after surgery. CHA2DS2-VASc scores were a mean of 3.9 in both arms, and at least 2 in all participants.

The rate of clinically significant hematoma – the primary outcome in the study, defined as a hematoma requiring prolonged hospitalization, interrupted postoperative anticoagulation, or reoperation to evacuate – was identical in both arms, 2.1% (seven patients each). There were two ischemic strokes, one in each arm. There was one delayed cardiac tamponade in the continuation arm and one pericardial effusion in the interrupted arm. The three deaths in the trial were not related to device placement.

So, what to do depends on the clinical scenario, Dr. Birnie said in an interview. If someone needs urgent placement and there’s no time to wait for DOAC washout, “it’s quite reasonable to go ahead.” Also, “if somebody is at extremely high risk for stroke, then it’s very reasonable to continue the drug.”

On the other hand, “if someone has a much lower stroke risk, then the risk-benefit ratio is probably in the opposite direction, so temporarily discontinuing the drug is the right thing to do,” he said.

Dr. Birnie cautioned that although continued DOAC may reduce the risk of thromboembolism, “this study was not designed with power to answer this.”

“We are already putting these findings into practice” in Ottawa, he said. “Our protocol” – as in many places – “ was always to stop anticoagulation for 2 or 3 days, but now, for very high-risk patients – high-risk AF, unstable temporary pacing, that type of thing – we are very comfortable continuing it,” he said. The study follows up a previous randomized trial by Dr. Birnie and his colleagues that pitted continued warfarin against heparin bridging for AF device placement. There were far fewer device pocket hematomas with uninterrupted warfarin (N Engl J Med. 2013 May 30;368[22]:2084-93).

The team wanted to repeat the study using DOACs, since their use has grown substantially, with the majority of AF patients now on them.

The arms in BRUISE CONTROL–2 (Strategy of Continued Versus Interrupted Novel Oral Anticoagulant at Time of Device Surgery in Patients With Moderate to High Risk of Arterial Thromboembolic Events) were well matched, with a mean age of about 74 years; men made up more than 70% of the subjects in both arms. About 17% of the participants were on chronic aspirin therapy and about 4% were on clopidogrel, in each arm. The uninterrupted DOAC group went about 14 hours between their last preop and first postop DOAC dose. The interrupted group went about 72 hours.

BRUISE CONTROL–2 was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others. Dr. Birnie had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The rate of clinically significant hematoma was identical in both arms, at 2.1% (seven patients each).

Data source: BRUISE CONTROL-2, a randomized trial with more than 600 subjects.

Disclosures: The work was funded by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bayer, Pfizer, and Bristol-Myers Squibb, among others. The presenter had no relevant financial disclosures.

DAPT produces better CABG outcomes than aspirin alone

ANAHEIM, CALIF. – Treatment with dual-antiplatelet therapy following coronary artery bypass grafting with a saphenous vein maintained vein-graft patency better than aspirin alone in a randomized, multicenter trial with 500 patients.

After 1 year of dual-antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) with ticagrelor (Brilinta) and aspirin, 89% of saphenous-vein grafts remained patent, compared with a 77% patency rate in saphenous-vein grafts in patients treated with aspirin alone, a statistically significant difference for the study’s primary endpoint, Qiang Zhao, MD, said at the American Hart Association scientific sessions. The data, collected at six Chinese centers, also showed a nominal decrease in the combined rate of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke: 2% with DAPT and 5% with aspirin alone. It further showed an increase in major or bypass-related bleeds: 2% with DAPT and none with aspirin alone, reported Dr. Zhao, professor and director of cardiac surgery at Ruijin Hospital in Shanghai, China.

“If this result were repeated in a larger study it would be important,” John H. Alexander, MD, professor of medicine at Duke University in Durham, N.C., commented in a video interview.

The Compare the Efficacy of Different Antiplatelet Therapy Strategy After Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery (DACAB) trial randomized patients who underwent coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). They averaged about 64 years of age, and received an average of nearly four grafts each including an average of nearly three saphenous vein grafts. The study assigned patients to one of three treatment arms starting within 24 hours after surgery: 168 received ticagrelor 90 mg twice daily plus aspirin 100 mg once daily, 166 got ticagrelor alone, and 166 received aspirin alone. Treatment continued for 1 year.

“Some surgeons and physicians currently prescribe DAPT to CABG patients, but there is not much evidence of its benefit. The DACAB trial is useful, but you need to show that it does not just improve patency but that patients also have better outcomes. The excess of major bleeds is a big deal. It gives one pause about adopting DAPT as standard treatment,” Dr. Gardner said.

DACAB received no commercial funding. Dr. Zhao has been a speaker on behalf of and has received research funding from AstraZeneca, the company that markets ticagrelor (Brilinta). He has also been a speaker for Johnson & Johnson and Medtronic and has received research funding from Bayer, Novartis, and Sanofi. Dr. Gardner had no disclosures.

mzoler@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

Results from the DACAB trial showed that using aspirin and ticagrelor improved vein-graft patency, compared with using aspirin alone. It was a compelling result, but for the intermediate, imaging-based outcome of graft patency at 1 year after surgery. This finding is conclusive evidence that dual-antiplatelet therapy has some benefit.