User login

Coffee, caffeine, and glucose tolerance

Some of us are at least peripherally aware of the proposed link between coffee consumption and the development of diabetes. Fewer of us are aware of the apparent contradiction in this relationship: Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee are associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, but ingestion of caffeine and caffeinated coffee results in worsening of glucose tolerance prior to a glucose load or a meal. Compounds in coffee other than caffeine have beneficial effects on glucose metabolism.

So what are we telling our patients about coffee?

Certainly we should not be recommending coffee to many of our patients who already have issues with insulin sensitivity. Perhaps more data are needed to make us feel comfortable about the impact of acute ingestion of coffee on serum glucose concentrations.

Keizo Ohnaka, Ph.D., and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial in Japan that may put us more at ease on this issue (J. Nutr. Metab. 2012 Nov. 5 [doi:10.1155/2012/207426]). In this study, overweight men with an average fasting glucose of 108 mg/dL were randomized to consumption of five cups of caffeinated or decaffeinated instant coffee per day or no coffee for 16 weeks. The primary outcome measure was the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.

Men in the coffee group were instructed to prepare a cup or glass of coffee using one spoonful of instant coffee without sugar, milk, or any other additives.

The men who drank caffeinated coffee demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in the 2-hour concentrations and area under the curve of glucose. The decaffeinated-coffee and no-coffee groups demonstrated no significant changes.

Interestingly, waist circumference decreased in the caffeinated coffee group, increased in the decaffeinated group, and did not change in the no-coffee group. After adjusting for waist size changes, the authors concluded that both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee appear to be protective against deteriorating glucose tolerance.

The study seems to support the general notion that compounds in coffee are the likely agents exerting positive effects on serum glucose. These compounds are substances with names that are challenging to remember, such as chlorogenic acids and polyphenols.

This study showed clearly that consumption of coffee – both caffeinated and decaffeinated – did not worsen glucose tolerance. The data remain consistent with evidence that caffeine and sugar result in worsening of blood glucose.

So, when counseling our patients about the benefits of coffee, tell them it needs to be "straight up" rather than "fancy" (mocha or latte) to work its magic.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Some of us are at least peripherally aware of the proposed link between coffee consumption and the development of diabetes. Fewer of us are aware of the apparent contradiction in this relationship: Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee are associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, but ingestion of caffeine and caffeinated coffee results in worsening of glucose tolerance prior to a glucose load or a meal. Compounds in coffee other than caffeine have beneficial effects on glucose metabolism.

So what are we telling our patients about coffee?

Certainly we should not be recommending coffee to many of our patients who already have issues with insulin sensitivity. Perhaps more data are needed to make us feel comfortable about the impact of acute ingestion of coffee on serum glucose concentrations.

Keizo Ohnaka, Ph.D., and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial in Japan that may put us more at ease on this issue (J. Nutr. Metab. 2012 Nov. 5 [doi:10.1155/2012/207426]). In this study, overweight men with an average fasting glucose of 108 mg/dL were randomized to consumption of five cups of caffeinated or decaffeinated instant coffee per day or no coffee for 16 weeks. The primary outcome measure was the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.

Men in the coffee group were instructed to prepare a cup or glass of coffee using one spoonful of instant coffee without sugar, milk, or any other additives.

The men who drank caffeinated coffee demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in the 2-hour concentrations and area under the curve of glucose. The decaffeinated-coffee and no-coffee groups demonstrated no significant changes.

Interestingly, waist circumference decreased in the caffeinated coffee group, increased in the decaffeinated group, and did not change in the no-coffee group. After adjusting for waist size changes, the authors concluded that both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee appear to be protective against deteriorating glucose tolerance.

The study seems to support the general notion that compounds in coffee are the likely agents exerting positive effects on serum glucose. These compounds are substances with names that are challenging to remember, such as chlorogenic acids and polyphenols.

This study showed clearly that consumption of coffee – both caffeinated and decaffeinated – did not worsen glucose tolerance. The data remain consistent with evidence that caffeine and sugar result in worsening of blood glucose.

So, when counseling our patients about the benefits of coffee, tell them it needs to be "straight up" rather than "fancy" (mocha or latte) to work its magic.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Some of us are at least peripherally aware of the proposed link between coffee consumption and the development of diabetes. Fewer of us are aware of the apparent contradiction in this relationship: Caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee are associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus, but ingestion of caffeine and caffeinated coffee results in worsening of glucose tolerance prior to a glucose load or a meal. Compounds in coffee other than caffeine have beneficial effects on glucose metabolism.

So what are we telling our patients about coffee?

Certainly we should not be recommending coffee to many of our patients who already have issues with insulin sensitivity. Perhaps more data are needed to make us feel comfortable about the impact of acute ingestion of coffee on serum glucose concentrations.

Keizo Ohnaka, Ph.D., and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial in Japan that may put us more at ease on this issue (J. Nutr. Metab. 2012 Nov. 5 [doi:10.1155/2012/207426]). In this study, overweight men with an average fasting glucose of 108 mg/dL were randomized to consumption of five cups of caffeinated or decaffeinated instant coffee per day or no coffee for 16 weeks. The primary outcome measure was the 75-g oral glucose tolerance test.

Men in the coffee group were instructed to prepare a cup or glass of coffee using one spoonful of instant coffee without sugar, milk, or any other additives.

The men who drank caffeinated coffee demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in the 2-hour concentrations and area under the curve of glucose. The decaffeinated-coffee and no-coffee groups demonstrated no significant changes.

Interestingly, waist circumference decreased in the caffeinated coffee group, increased in the decaffeinated group, and did not change in the no-coffee group. After adjusting for waist size changes, the authors concluded that both caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee appear to be protective against deteriorating glucose tolerance.

The study seems to support the general notion that compounds in coffee are the likely agents exerting positive effects on serum glucose. These compounds are substances with names that are challenging to remember, such as chlorogenic acids and polyphenols.

This study showed clearly that consumption of coffee – both caffeinated and decaffeinated – did not worsen glucose tolerance. The data remain consistent with evidence that caffeine and sugar result in worsening of blood glucose.

So, when counseling our patients about the benefits of coffee, tell them it needs to be "straight up" rather than "fancy" (mocha or latte) to work its magic.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Statin dose rises, adherence falls?

Literally billions of prescriptions for medications are written each year in the United States. Lipid modulators are the most frequently prescribed class of drugs.

Lipid modulators are drugs requiring blood tests to see how they are working. As a result, a considerable amount of clinical time is spent chasing numbers as we treat to target. Dose escalations are a frequent, almost reflexive, response to LDLs that are not at goal. Such decisions are made easier because there is commonly equivalent pricing on different doses (that is, 80 mg of atorvastatin is the same cost as 20 mg of atorvastatin).

Many of these decisions are made sight unseen and relayed through clinical support staff. But maybe those decisions shouldn’t be made quite so fast.

Pittman and colleagues published an analysis of the relationship between statin nonadherence and treatment intensification (Am. J. Cardiol. 2012;110:1459-63). Investigators conducted a retrospective analysis using an integrated pharmacy and medical claims database including more than 126,000 patients. Claims were analyzed to determine medication nonadherence, which was defined as the proportion of statin-covered days totaling less than 80%. Nonadherence was then related to statin dose escalations over a 360-day period of follow-up.

Disturbingly, but perhaps not completely surprisingly, 44% of the 11,361 patients who received an increased dose were nonadherent to the medication. Patients who were nonadherent to statins were 30% more likely to have treatment escalation than nonadherent patients.

Many of us are, in fact, conducting "adherence conversations" with our patients much of the time. But not all of us are having these conversations all of the time. Although a significant barrier may be lack of adequate time, one could argue that the more significant barriers are the lack of clinical tools to assess adherence and not knowing what defines true "nonadherence" for statins. We are perhaps not certain what the least amount of a cholesterol-lowering agent is that somebody needs to take and have it still be effective at reaching an individual’s goal LDL.

In the absence of this knowledge, we could consider implementing an "80% rule" based upon the cutoff selected in this article.

If we or our clinical staff receive a "no" to the question, "Did you use the medication more than 80% of the time?" we could address adherence issues, maintain the current dose, and recheck the LDL in 3 months. At the very least, we could avoid needing to fill out another prescription.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Literally billions of prescriptions for medications are written each year in the United States. Lipid modulators are the most frequently prescribed class of drugs.

Lipid modulators are drugs requiring blood tests to see how they are working. As a result, a considerable amount of clinical time is spent chasing numbers as we treat to target. Dose escalations are a frequent, almost reflexive, response to LDLs that are not at goal. Such decisions are made easier because there is commonly equivalent pricing on different doses (that is, 80 mg of atorvastatin is the same cost as 20 mg of atorvastatin).

Many of these decisions are made sight unseen and relayed through clinical support staff. But maybe those decisions shouldn’t be made quite so fast.

Pittman and colleagues published an analysis of the relationship between statin nonadherence and treatment intensification (Am. J. Cardiol. 2012;110:1459-63). Investigators conducted a retrospective analysis using an integrated pharmacy and medical claims database including more than 126,000 patients. Claims were analyzed to determine medication nonadherence, which was defined as the proportion of statin-covered days totaling less than 80%. Nonadherence was then related to statin dose escalations over a 360-day period of follow-up.

Disturbingly, but perhaps not completely surprisingly, 44% of the 11,361 patients who received an increased dose were nonadherent to the medication. Patients who were nonadherent to statins were 30% more likely to have treatment escalation than nonadherent patients.

Many of us are, in fact, conducting "adherence conversations" with our patients much of the time. But not all of us are having these conversations all of the time. Although a significant barrier may be lack of adequate time, one could argue that the more significant barriers are the lack of clinical tools to assess adherence and not knowing what defines true "nonadherence" for statins. We are perhaps not certain what the least amount of a cholesterol-lowering agent is that somebody needs to take and have it still be effective at reaching an individual’s goal LDL.

In the absence of this knowledge, we could consider implementing an "80% rule" based upon the cutoff selected in this article.

If we or our clinical staff receive a "no" to the question, "Did you use the medication more than 80% of the time?" we could address adherence issues, maintain the current dose, and recheck the LDL in 3 months. At the very least, we could avoid needing to fill out another prescription.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Literally billions of prescriptions for medications are written each year in the United States. Lipid modulators are the most frequently prescribed class of drugs.

Lipid modulators are drugs requiring blood tests to see how they are working. As a result, a considerable amount of clinical time is spent chasing numbers as we treat to target. Dose escalations are a frequent, almost reflexive, response to LDLs that are not at goal. Such decisions are made easier because there is commonly equivalent pricing on different doses (that is, 80 mg of atorvastatin is the same cost as 20 mg of atorvastatin).

Many of these decisions are made sight unseen and relayed through clinical support staff. But maybe those decisions shouldn’t be made quite so fast.

Pittman and colleagues published an analysis of the relationship between statin nonadherence and treatment intensification (Am. J. Cardiol. 2012;110:1459-63). Investigators conducted a retrospective analysis using an integrated pharmacy and medical claims database including more than 126,000 patients. Claims were analyzed to determine medication nonadherence, which was defined as the proportion of statin-covered days totaling less than 80%. Nonadherence was then related to statin dose escalations over a 360-day period of follow-up.

Disturbingly, but perhaps not completely surprisingly, 44% of the 11,361 patients who received an increased dose were nonadherent to the medication. Patients who were nonadherent to statins were 30% more likely to have treatment escalation than nonadherent patients.

Many of us are, in fact, conducting "adherence conversations" with our patients much of the time. But not all of us are having these conversations all of the time. Although a significant barrier may be lack of adequate time, one could argue that the more significant barriers are the lack of clinical tools to assess adherence and not knowing what defines true "nonadherence" for statins. We are perhaps not certain what the least amount of a cholesterol-lowering agent is that somebody needs to take and have it still be effective at reaching an individual’s goal LDL.

In the absence of this knowledge, we could consider implementing an "80% rule" based upon the cutoff selected in this article.

If we or our clinical staff receive a "no" to the question, "Did you use the medication more than 80% of the time?" we could address adherence issues, maintain the current dose, and recheck the LDL in 3 months. At the very least, we could avoid needing to fill out another prescription.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Paying Attention to Adult ADHD

Many of us in clinical practice have been challenged with adults presenting with the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Many of these adults have either diagnosed themselves through their own investigation or describe sometimes foggy histories of being diagnosed with this disorder as children. But somewhere, somehow, their treatment for the condition stopped, and now it has again become manifest.

Growing consensus exists that the central feature of ADHD is disinhibition. Animal models suggest that this condition is associated with an imbalance in the dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems characterized by decreased dopamine activity and increased norepinephrine activity. Clinical manifestations include poor self-regulation, an inability to prevent immediate responding, and difficulty with attention and goal-directed behavior and thought.

Available data suggest that between 30% and 70% of children with ADHD continue to exhibit symptoms into adulthood. Hyperactivity, however, is more difficult to discern in adults. Adults typically present with work-related issues and poor organizational skills.

Psychostimulants are a mainstay of therapy. But we need to remain cautious and circumspect about the patients requesting them to treat the disorder. Moreover, the addictive nature of stimulants, the chronicity of this condition, and the existence of potentially comorbid conditions in adults have led many experts to recommend a trial of a nonstimulant agent first.

Bupropion is an antidepressant that has an effect on both dopamine and norepinephrine, and has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of adults with ADHD. Dr. Narong Maneeton and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of randomized trials evaluating the efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of bupropion in adults with ADHD (Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011;65:611-7). Five published trials with a total of 349 subjects were included.

The overall response rate of the bupropion-treated group was significantly greater than that of placebo-treated (relative risk, 1.67; 95% CI: 1.23-2.26). Two other studies have reported bupropion response rates between 53% and 76%, with doses ranging from 200 mg/day to 450 mg/day. A positive effect on ADHD symptoms can be seen at 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.

Bupropion is a great choice as an initial agent for patients who screen positive for the condition and have a compelling history. For patients who fail this approach, referral for a definitive diagnosis and assistance with dosing and management of psychostimulants is completely justified.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Many of us in clinical practice have been challenged with adults presenting with the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Many of these adults have either diagnosed themselves through their own investigation or describe sometimes foggy histories of being diagnosed with this disorder as children. But somewhere, somehow, their treatment for the condition stopped, and now it has again become manifest.

Growing consensus exists that the central feature of ADHD is disinhibition. Animal models suggest that this condition is associated with an imbalance in the dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems characterized by decreased dopamine activity and increased norepinephrine activity. Clinical manifestations include poor self-regulation, an inability to prevent immediate responding, and difficulty with attention and goal-directed behavior and thought.

Available data suggest that between 30% and 70% of children with ADHD continue to exhibit symptoms into adulthood. Hyperactivity, however, is more difficult to discern in adults. Adults typically present with work-related issues and poor organizational skills.

Psychostimulants are a mainstay of therapy. But we need to remain cautious and circumspect about the patients requesting them to treat the disorder. Moreover, the addictive nature of stimulants, the chronicity of this condition, and the existence of potentially comorbid conditions in adults have led many experts to recommend a trial of a nonstimulant agent first.

Bupropion is an antidepressant that has an effect on both dopamine and norepinephrine, and has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of adults with ADHD. Dr. Narong Maneeton and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of randomized trials evaluating the efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of bupropion in adults with ADHD (Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011;65:611-7). Five published trials with a total of 349 subjects were included.

The overall response rate of the bupropion-treated group was significantly greater than that of placebo-treated (relative risk, 1.67; 95% CI: 1.23-2.26). Two other studies have reported bupropion response rates between 53% and 76%, with doses ranging from 200 mg/day to 450 mg/day. A positive effect on ADHD symptoms can be seen at 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.

Bupropion is a great choice as an initial agent for patients who screen positive for the condition and have a compelling history. For patients who fail this approach, referral for a definitive diagnosis and assistance with dosing and management of psychostimulants is completely justified.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Many of us in clinical practice have been challenged with adults presenting with the diagnosis of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Many of these adults have either diagnosed themselves through their own investigation or describe sometimes foggy histories of being diagnosed with this disorder as children. But somewhere, somehow, their treatment for the condition stopped, and now it has again become manifest.

Growing consensus exists that the central feature of ADHD is disinhibition. Animal models suggest that this condition is associated with an imbalance in the dopaminergic and noradrenergic systems characterized by decreased dopamine activity and increased norepinephrine activity. Clinical manifestations include poor self-regulation, an inability to prevent immediate responding, and difficulty with attention and goal-directed behavior and thought.

Available data suggest that between 30% and 70% of children with ADHD continue to exhibit symptoms into adulthood. Hyperactivity, however, is more difficult to discern in adults. Adults typically present with work-related issues and poor organizational skills.

Psychostimulants are a mainstay of therapy. But we need to remain cautious and circumspect about the patients requesting them to treat the disorder. Moreover, the addictive nature of stimulants, the chronicity of this condition, and the existence of potentially comorbid conditions in adults have led many experts to recommend a trial of a nonstimulant agent first.

Bupropion is an antidepressant that has an effect on both dopamine and norepinephrine, and has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of adults with ADHD. Dr. Narong Maneeton and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis of randomized trials evaluating the efficacy, acceptability and tolerability of bupropion in adults with ADHD (Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2011;65:611-7). Five published trials with a total of 349 subjects were included.

The overall response rate of the bupropion-treated group was significantly greater than that of placebo-treated (relative risk, 1.67; 95% CI: 1.23-2.26). Two other studies have reported bupropion response rates between 53% and 76%, with doses ranging from 200 mg/day to 450 mg/day. A positive effect on ADHD symptoms can be seen at 2 weeks after initiation of therapy.

Bupropion is a great choice as an initial agent for patients who screen positive for the condition and have a compelling history. For patients who fail this approach, referral for a definitive diagnosis and assistance with dosing and management of psychostimulants is completely justified.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Coumadin With an Aspirin Chaser

Estimates suggest that pulmonary embolisms cause 1.3% of deaths. This is probably an underestimation of the true number of patients who experience a PE, but the advent of CT angiography has dramatically increased both our ability to detect PE and the number of our patients receiving anticoagulation.

After a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is established and patients are appropriately treated, we switch to the search for risk factors. Risk factor reversibility and resolution guide the duration of anticoagulation therapy. Most patients with acute PE have an identifiable risk factor at the time of presentation. For those patients who have a first episode of PE with reversed or resolved risk factors – such as immobilization, surgery, and trauma – 3 months of therapy may be warranted.

So, what about those patients who do not have an identified risk factor (that is, "unprovoked") for whom we elect to stop coumadin after 3 months? The risk of recurrence in this group is about 20% within 2 years of discontinuation of vitamin K antagonists (such as coumadin).

Is there anything we can do to reduce this risk for recurrence?

A randomized clinical trial published earlier this year evaluated the efficacy of aspirin 100 mg daily given for 2 years to prevent the recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were at least 18 years of age and were treated for 6-18 months with vitamin K antagonists for a first-ever objectively confirmed unprovoked DVT, PE, or both. Mean patient age was 62 years. Study outcomes were confirmed by a central, independent adjudication committee.

Patients were randomized either to aspirin (205 patients) or placebo (197 patients) (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1959-67).

The rate of VTE recurrence was significantly lower among patients receiving aspirin than among those receiving placebo: 6.6% vs. 11.2% per year, respectively (hazard ratio 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.36-0.93). Subgroup analyses revealed that patients who entered the study because of PE had a significantly lower recurrence rate on aspirin (6.7% per year), compared with placebo (13.5%) (HR 0.38; 95% CI: 0.17-0.88). This was also true of patients who entered the study because of DVT, though the difference wasn’t significant (HR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.65-1.20). No differences were observed in bleeding events between aspirin and placebo.

The aspirin dose used in this study is the dose recommended for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events. These data are extremely compelling and should be incorporated into our practices, if they aren’t already.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Estimates suggest that pulmonary embolisms cause 1.3% of deaths. This is probably an underestimation of the true number of patients who experience a PE, but the advent of CT angiography has dramatically increased both our ability to detect PE and the number of our patients receiving anticoagulation.

After a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is established and patients are appropriately treated, we switch to the search for risk factors. Risk factor reversibility and resolution guide the duration of anticoagulation therapy. Most patients with acute PE have an identifiable risk factor at the time of presentation. For those patients who have a first episode of PE with reversed or resolved risk factors – such as immobilization, surgery, and trauma – 3 months of therapy may be warranted.

So, what about those patients who do not have an identified risk factor (that is, "unprovoked") for whom we elect to stop coumadin after 3 months? The risk of recurrence in this group is about 20% within 2 years of discontinuation of vitamin K antagonists (such as coumadin).

Is there anything we can do to reduce this risk for recurrence?

A randomized clinical trial published earlier this year evaluated the efficacy of aspirin 100 mg daily given for 2 years to prevent the recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were at least 18 years of age and were treated for 6-18 months with vitamin K antagonists for a first-ever objectively confirmed unprovoked DVT, PE, or both. Mean patient age was 62 years. Study outcomes were confirmed by a central, independent adjudication committee.

Patients were randomized either to aspirin (205 patients) or placebo (197 patients) (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1959-67).

The rate of VTE recurrence was significantly lower among patients receiving aspirin than among those receiving placebo: 6.6% vs. 11.2% per year, respectively (hazard ratio 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.36-0.93). Subgroup analyses revealed that patients who entered the study because of PE had a significantly lower recurrence rate on aspirin (6.7% per year), compared with placebo (13.5%) (HR 0.38; 95% CI: 0.17-0.88). This was also true of patients who entered the study because of DVT, though the difference wasn’t significant (HR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.65-1.20). No differences were observed in bleeding events between aspirin and placebo.

The aspirin dose used in this study is the dose recommended for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events. These data are extremely compelling and should be incorporated into our practices, if they aren’t already.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Estimates suggest that pulmonary embolisms cause 1.3% of deaths. This is probably an underestimation of the true number of patients who experience a PE, but the advent of CT angiography has dramatically increased both our ability to detect PE and the number of our patients receiving anticoagulation.

After a diagnosis of pulmonary embolism is established and patients are appropriately treated, we switch to the search for risk factors. Risk factor reversibility and resolution guide the duration of anticoagulation therapy. Most patients with acute PE have an identifiable risk factor at the time of presentation. For those patients who have a first episode of PE with reversed or resolved risk factors – such as immobilization, surgery, and trauma – 3 months of therapy may be warranted.

So, what about those patients who do not have an identified risk factor (that is, "unprovoked") for whom we elect to stop coumadin after 3 months? The risk of recurrence in this group is about 20% within 2 years of discontinuation of vitamin K antagonists (such as coumadin).

Is there anything we can do to reduce this risk for recurrence?

A randomized clinical trial published earlier this year evaluated the efficacy of aspirin 100 mg daily given for 2 years to prevent the recurrence of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Patients were eligible for enrollment if they were at least 18 years of age and were treated for 6-18 months with vitamin K antagonists for a first-ever objectively confirmed unprovoked DVT, PE, or both. Mean patient age was 62 years. Study outcomes were confirmed by a central, independent adjudication committee.

Patients were randomized either to aspirin (205 patients) or placebo (197 patients) (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:1959-67).

The rate of VTE recurrence was significantly lower among patients receiving aspirin than among those receiving placebo: 6.6% vs. 11.2% per year, respectively (hazard ratio 0.58; 95% confidence interval, 0.36-0.93). Subgroup analyses revealed that patients who entered the study because of PE had a significantly lower recurrence rate on aspirin (6.7% per year), compared with placebo (13.5%) (HR 0.38; 95% CI: 0.17-0.88). This was also true of patients who entered the study because of DVT, though the difference wasn’t significant (HR 0.65; 95% CI: 0.65-1.20). No differences were observed in bleeding events between aspirin and placebo.

The aspirin dose used in this study is the dose recommended for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular events. These data are extremely compelling and should be incorporated into our practices, if they aren’t already.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Man's Best Friend

When you feel like you have run out of ideas for motivating patients to engage in regular activity, try this: Ask your patients if they own dogs.

Dog owners tend to engage in more leisure-time activity. People who walk their dogs have a lower prevalence of obesity than owners who do not walk their dogs or non-owners. Clinicians could capitalize on this mutually beneficial relationship and improve patient health.

But can inactive dog owners be motivated to become active?

Ryan E. Rhodes and his colleagues at the University of Victoria (B.C.) evaluated the efficacy of an intervention using messages targeting canine exercise to increase owners’ physical activity. Advertisements were placed for pet owners who did not regularly walk their dogs. Regular dog walking was defined as more than four times per week for a minimum of 30 minutes at a brisk pace, the minimum amount of physical activity recommended for Canadian adults. The intervention group was instructed to read and use materials emphasizing the benefits of exercise for dogs, proper types and amounts of exercise for dogs, tips for regular walking, and motivational quotes from dog owners. The control participants were instructed to continue with their current dog walking pattern. Both groups were asked to wear a pedometer. Outcomes were measured at 6 and 12 weeks.

Both groups increased their physical activity across 12 weeks. Significantly higher step counts were observed in the intervention group as well as higher trajectories in the self-reported activity measures. Further analysis suggested that increases in walking with the dog did not occur at the expense of walking without the dog.

This work leverages the sense of responsibility and obligation that dog owners have to their pets to increase physical activity among the owners. Behavioral change motivated by duty to pets has also been thought to occur with information that secondhand smoke increases the risk for feline malignant lymphoma.

For me, honesty will remain the best policy. This information will be presented best when discussed along with how the benefits of increased physical activity will benefit dogs. In this context, the dog can serve as a "change agent" for long-term beneficial health behavior changes.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

When you feel like you have run out of ideas for motivating patients to engage in regular activity, try this: Ask your patients if they own dogs.

Dog owners tend to engage in more leisure-time activity. People who walk their dogs have a lower prevalence of obesity than owners who do not walk their dogs or non-owners. Clinicians could capitalize on this mutually beneficial relationship and improve patient health.

But can inactive dog owners be motivated to become active?

Ryan E. Rhodes and his colleagues at the University of Victoria (B.C.) evaluated the efficacy of an intervention using messages targeting canine exercise to increase owners’ physical activity. Advertisements were placed for pet owners who did not regularly walk their dogs. Regular dog walking was defined as more than four times per week for a minimum of 30 minutes at a brisk pace, the minimum amount of physical activity recommended for Canadian adults. The intervention group was instructed to read and use materials emphasizing the benefits of exercise for dogs, proper types and amounts of exercise for dogs, tips for regular walking, and motivational quotes from dog owners. The control participants were instructed to continue with their current dog walking pattern. Both groups were asked to wear a pedometer. Outcomes were measured at 6 and 12 weeks.

Both groups increased their physical activity across 12 weeks. Significantly higher step counts were observed in the intervention group as well as higher trajectories in the self-reported activity measures. Further analysis suggested that increases in walking with the dog did not occur at the expense of walking without the dog.

This work leverages the sense of responsibility and obligation that dog owners have to their pets to increase physical activity among the owners. Behavioral change motivated by duty to pets has also been thought to occur with information that secondhand smoke increases the risk for feline malignant lymphoma.

For me, honesty will remain the best policy. This information will be presented best when discussed along with how the benefits of increased physical activity will benefit dogs. In this context, the dog can serve as a "change agent" for long-term beneficial health behavior changes.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

When you feel like you have run out of ideas for motivating patients to engage in regular activity, try this: Ask your patients if they own dogs.

Dog owners tend to engage in more leisure-time activity. People who walk their dogs have a lower prevalence of obesity than owners who do not walk their dogs or non-owners. Clinicians could capitalize on this mutually beneficial relationship and improve patient health.

But can inactive dog owners be motivated to become active?

Ryan E. Rhodes and his colleagues at the University of Victoria (B.C.) evaluated the efficacy of an intervention using messages targeting canine exercise to increase owners’ physical activity. Advertisements were placed for pet owners who did not regularly walk their dogs. Regular dog walking was defined as more than four times per week for a minimum of 30 minutes at a brisk pace, the minimum amount of physical activity recommended for Canadian adults. The intervention group was instructed to read and use materials emphasizing the benefits of exercise for dogs, proper types and amounts of exercise for dogs, tips for regular walking, and motivational quotes from dog owners. The control participants were instructed to continue with their current dog walking pattern. Both groups were asked to wear a pedometer. Outcomes were measured at 6 and 12 weeks.

Both groups increased their physical activity across 12 weeks. Significantly higher step counts were observed in the intervention group as well as higher trajectories in the self-reported activity measures. Further analysis suggested that increases in walking with the dog did not occur at the expense of walking without the dog.

This work leverages the sense of responsibility and obligation that dog owners have to their pets to increase physical activity among the owners. Behavioral change motivated by duty to pets has also been thought to occur with information that secondhand smoke increases the risk for feline malignant lymphoma.

For me, honesty will remain the best policy. This information will be presented best when discussed along with how the benefits of increased physical activity will benefit dogs. In this context, the dog can serve as a "change agent" for long-term beneficial health behavior changes.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

E-Management of Chronic Pain

Chronic pain is reported by 20%-50% of patients seen in primary care and is a condition with which we are all too familiar. Chronic pain patients suffer while consuming tremendous amounts of health care resources. Long-term narcotics, regrettably, became a fact of life for many.

Clinical frustration, fatigue, and burnout with chronic pain management are frequently compounded by a dearth of proven, effective self-management strategies. Self-help may be on the way.

Linda S. Ruehlman and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a self-paced, interactive online chronic pain management program. In this study, 305 participants with chronic pain were randomized to a self-help online program for approximately 6 weeks or a wait-list control condition. Subjects were eligible for enrollment if they were at least 18 years old, had chronic pain for 6 months or longer, and had Internet access. Subjects were recruited online from pain-related websites.

The online program consisted of proven-effective, evidence-based psychosocial interventions for chronic pain. The program focused on cognition, behavior, social, and emotional regulation. Participants developed a customized learning plan, explored content of four modules with didactic and interactive components, practiced offline exercise and relaxation activities, tracked functional progress (pain management, mood, activity level), and engaged in social networking. Subjects in the wait-list control group received full access to the program at the end of the study.

This online pain program was associated with significant decreases in pain severity, pain-related interference and emotional burden, perceived disability, catastrophizing, and pain-induced fear. The program also significantly decreased depression, anxiety, and stress.

We need tools that complement the clinical resources that we expend managing patients with chronic pain. The tool used in this study is currently available online. According to recent statistics, 87% of individuals aged 30-49 years and 74% of those aged 50-64 years in the U.S. use the Internet. The likelihood is high, therefore, that our most our patients with chronic pain will have access to it. Our job is to motivate them to engage.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reported having no conflicts of interest with the online pain program described in this article. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Contact him at ebbert.jon@mayo.edu.

Chronic pain is reported by 20%-50% of patients seen in primary care and is a condition with which we are all too familiar. Chronic pain patients suffer while consuming tremendous amounts of health care resources. Long-term narcotics, regrettably, became a fact of life for many.

Clinical frustration, fatigue, and burnout with chronic pain management are frequently compounded by a dearth of proven, effective self-management strategies. Self-help may be on the way.

Linda S. Ruehlman and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a self-paced, interactive online chronic pain management program. In this study, 305 participants with chronic pain were randomized to a self-help online program for approximately 6 weeks or a wait-list control condition. Subjects were eligible for enrollment if they were at least 18 years old, had chronic pain for 6 months or longer, and had Internet access. Subjects were recruited online from pain-related websites.

The online program consisted of proven-effective, evidence-based psychosocial interventions for chronic pain. The program focused on cognition, behavior, social, and emotional regulation. Participants developed a customized learning plan, explored content of four modules with didactic and interactive components, practiced offline exercise and relaxation activities, tracked functional progress (pain management, mood, activity level), and engaged in social networking. Subjects in the wait-list control group received full access to the program at the end of the study.

This online pain program was associated with significant decreases in pain severity, pain-related interference and emotional burden, perceived disability, catastrophizing, and pain-induced fear. The program also significantly decreased depression, anxiety, and stress.

We need tools that complement the clinical resources that we expend managing patients with chronic pain. The tool used in this study is currently available online. According to recent statistics, 87% of individuals aged 30-49 years and 74% of those aged 50-64 years in the U.S. use the Internet. The likelihood is high, therefore, that our most our patients with chronic pain will have access to it. Our job is to motivate them to engage.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reported having no conflicts of interest with the online pain program described in this article. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Contact him at ebbert.jon@mayo.edu.

Chronic pain is reported by 20%-50% of patients seen in primary care and is a condition with which we are all too familiar. Chronic pain patients suffer while consuming tremendous amounts of health care resources. Long-term narcotics, regrettably, became a fact of life for many.

Clinical frustration, fatigue, and burnout with chronic pain management are frequently compounded by a dearth of proven, effective self-management strategies. Self-help may be on the way.

Linda S. Ruehlman and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of a self-paced, interactive online chronic pain management program. In this study, 305 participants with chronic pain were randomized to a self-help online program for approximately 6 weeks or a wait-list control condition. Subjects were eligible for enrollment if they were at least 18 years old, had chronic pain for 6 months or longer, and had Internet access. Subjects were recruited online from pain-related websites.

The online program consisted of proven-effective, evidence-based psychosocial interventions for chronic pain. The program focused on cognition, behavior, social, and emotional regulation. Participants developed a customized learning plan, explored content of four modules with didactic and interactive components, practiced offline exercise and relaxation activities, tracked functional progress (pain management, mood, activity level), and engaged in social networking. Subjects in the wait-list control group received full access to the program at the end of the study.

This online pain program was associated with significant decreases in pain severity, pain-related interference and emotional burden, perceived disability, catastrophizing, and pain-induced fear. The program also significantly decreased depression, anxiety, and stress.

We need tools that complement the clinical resources that we expend managing patients with chronic pain. The tool used in this study is currently available online. According to recent statistics, 87% of individuals aged 30-49 years and 74% of those aged 50-64 years in the U.S. use the Internet. The likelihood is high, therefore, that our most our patients with chronic pain will have access to it. Our job is to motivate them to engage.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reported having no conflicts of interest with the online pain program described in this article. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Contact him at ebbert.jon@mayo.edu.

Benzos May Cause Dementia

Benzodiazepines consistently make the Top 5 list of most commonly prescribed medications in the United States. Benzodiazepines should generally be used for short-term control of symptoms (for example, anxiolysis) in the majority of cases. Prescribing patterns suggest that people stay on them long term, however. Community-based population studies demonstrate that among 5.5% of men and 9.8% of women 65 years of age and older using benzodiazepines at baseline, 50% of this group were still using them 15 years later.

All of us can easily think of patients in our panels who we have maintained on these medications for various indications. Discontinuing benzodiazepines can be difficult because of symptom rebound (such as worse symptoms) and re-emergence (that is, relapse) and should generally be tapered over several months. But beginning these discussions with patients are difficult for both us and them. But what are the risks on continuation?

Dr. Sophie Billioti de Gage of Université Bordeaux Segalen conducted a population-based study evaluating the association between use of benzodiazepines and incident dementia. In this study, 1,063 men and women with a mean age of 78 years free of dementia at baseline were followed for 15 years. During follow-up, new cases of dementia were diagnosed in 30 (32%) benzodiazepine users and 223 (23.0%) nonusers. New use of benzodiazepines was associated with an increased risk of dementia (multivariable adjusted hazard ratio, 1.60; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.38). Ever use of benzodiazepines was associated with an increased risk for dementia, compared with never use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.55; CI, 1.24-1.95). Estimates remained stable after adjustment for cognitive decline before starting benzodiazepines and clinically significant depression.

We do not know the potential impact of benzodiazepines among younger patients. But the findings from this study should provide us with some additional thought and motivation to address benzodiazepine use among our older patients. Given the commonly expressed dread of developing dementia among my older patients, this will help me at least get the conversation started.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Benzodiazepines consistently make the Top 5 list of most commonly prescribed medications in the United States. Benzodiazepines should generally be used for short-term control of symptoms (for example, anxiolysis) in the majority of cases. Prescribing patterns suggest that people stay on them long term, however. Community-based population studies demonstrate that among 5.5% of men and 9.8% of women 65 years of age and older using benzodiazepines at baseline, 50% of this group were still using them 15 years later.

All of us can easily think of patients in our panels who we have maintained on these medications for various indications. Discontinuing benzodiazepines can be difficult because of symptom rebound (such as worse symptoms) and re-emergence (that is, relapse) and should generally be tapered over several months. But beginning these discussions with patients are difficult for both us and them. But what are the risks on continuation?

Dr. Sophie Billioti de Gage of Université Bordeaux Segalen conducted a population-based study evaluating the association between use of benzodiazepines and incident dementia. In this study, 1,063 men and women with a mean age of 78 years free of dementia at baseline were followed for 15 years. During follow-up, new cases of dementia were diagnosed in 30 (32%) benzodiazepine users and 223 (23.0%) nonusers. New use of benzodiazepines was associated with an increased risk of dementia (multivariable adjusted hazard ratio, 1.60; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.38). Ever use of benzodiazepines was associated with an increased risk for dementia, compared with never use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.55; CI, 1.24-1.95). Estimates remained stable after adjustment for cognitive decline before starting benzodiazepines and clinically significant depression.

We do not know the potential impact of benzodiazepines among younger patients. But the findings from this study should provide us with some additional thought and motivation to address benzodiazepine use among our older patients. Given the commonly expressed dread of developing dementia among my older patients, this will help me at least get the conversation started.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Benzodiazepines consistently make the Top 5 list of most commonly prescribed medications in the United States. Benzodiazepines should generally be used for short-term control of symptoms (for example, anxiolysis) in the majority of cases. Prescribing patterns suggest that people stay on them long term, however. Community-based population studies demonstrate that among 5.5% of men and 9.8% of women 65 years of age and older using benzodiazepines at baseline, 50% of this group were still using them 15 years later.

All of us can easily think of patients in our panels who we have maintained on these medications for various indications. Discontinuing benzodiazepines can be difficult because of symptom rebound (such as worse symptoms) and re-emergence (that is, relapse) and should generally be tapered over several months. But beginning these discussions with patients are difficult for both us and them. But what are the risks on continuation?

Dr. Sophie Billioti de Gage of Université Bordeaux Segalen conducted a population-based study evaluating the association between use of benzodiazepines and incident dementia. In this study, 1,063 men and women with a mean age of 78 years free of dementia at baseline were followed for 15 years. During follow-up, new cases of dementia were diagnosed in 30 (32%) benzodiazepine users and 223 (23.0%) nonusers. New use of benzodiazepines was associated with an increased risk of dementia (multivariable adjusted hazard ratio, 1.60; 95% confidence interval, 1.08-2.38). Ever use of benzodiazepines was associated with an increased risk for dementia, compared with never use (adjusted odds ratio, 1.55; CI, 1.24-1.95). Estimates remained stable after adjustment for cognitive decline before starting benzodiazepines and clinically significant depression.

We do not know the potential impact of benzodiazepines among younger patients. But the findings from this study should provide us with some additional thought and motivation to address benzodiazepine use among our older patients. Given the commonly expressed dread of developing dementia among my older patients, this will help me at least get the conversation started.

Dr. Ebbert is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

The Problem With PPIs

Most of us can recall medical innovations that fundamentally changed the way we practice and prescribe. Important revolutions do not need to be dramatic, such as the discovery and widespread use of low-molecular-weight heparin or the MRI, for us to be forever converted. For me, it was the discovery and widespread use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

In the 1970s, evidence emerged that the proton pump in stomach parietal cells was the last step in acid secretion. At the same time, preanesthetic screenings pointed to the antisecretory effects of a compound called timoprazole. Creative chemistry and side-chain substitutions led to the launch of omeprazole in 1990. The rest, as they say, is history.

PPIs are currently the third most commonly sold drugs in the Unite States, in large part because they transformed the care of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in a remarkable way.

In the early days, clinicians seemed inclined to start patients on the histamine receptor antagonists as first-line therapy, reserving PPIs for more recalcitrant cases. With time, however, clinicians reached for PPIs earlier in the course of therapy to more quickly eradicate symptoms. As the obesity epidemic spread, so too did the epidemic of GERD and PPI use.

What we seem to have lost sight of is that patients are being continued on these medications indefinitely. But at what risk?

Dr. Neena S. Abraham of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston, and her colleagues, recently reviewed the literature on the long-term adverse health consequences of PPI use. She reported that the strongest evidence supports an increased risk for the development of Clostridium difficile infection and bone fracture. The mechanism of bone fracture relates to acid suppression and the "triple effect" of impairing the absorption of vitamin B12, which decreases osteoblastic activity; decreasing calcium absorption; and hypergastrinemia, which increases the release of parathyroid hormone contributing to bone resorption (Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2012 [Epub ahead of print])

Dr. Abraham challenges us to prescribe PPIs only for "robust indications." We need to challenge ourselves to take the time to try tapering or discontinuation trials among patients who have been on them for a prolonged period of time. Informing patients of the long-term risks will arm us for what might be, with many patients, difficult discussions.

Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Most of us can recall medical innovations that fundamentally changed the way we practice and prescribe. Important revolutions do not need to be dramatic, such as the discovery and widespread use of low-molecular-weight heparin or the MRI, for us to be forever converted. For me, it was the discovery and widespread use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

In the 1970s, evidence emerged that the proton pump in stomach parietal cells was the last step in acid secretion. At the same time, preanesthetic screenings pointed to the antisecretory effects of a compound called timoprazole. Creative chemistry and side-chain substitutions led to the launch of omeprazole in 1990. The rest, as they say, is history.

PPIs are currently the third most commonly sold drugs in the Unite States, in large part because they transformed the care of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in a remarkable way.

In the early days, clinicians seemed inclined to start patients on the histamine receptor antagonists as first-line therapy, reserving PPIs for more recalcitrant cases. With time, however, clinicians reached for PPIs earlier in the course of therapy to more quickly eradicate symptoms. As the obesity epidemic spread, so too did the epidemic of GERD and PPI use.

What we seem to have lost sight of is that patients are being continued on these medications indefinitely. But at what risk?

Dr. Neena S. Abraham of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston, and her colleagues, recently reviewed the literature on the long-term adverse health consequences of PPI use. She reported that the strongest evidence supports an increased risk for the development of Clostridium difficile infection and bone fracture. The mechanism of bone fracture relates to acid suppression and the "triple effect" of impairing the absorption of vitamin B12, which decreases osteoblastic activity; decreasing calcium absorption; and hypergastrinemia, which increases the release of parathyroid hormone contributing to bone resorption (Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2012 [Epub ahead of print])

Dr. Abraham challenges us to prescribe PPIs only for "robust indications." We need to challenge ourselves to take the time to try tapering or discontinuation trials among patients who have been on them for a prolonged period of time. Informing patients of the long-term risks will arm us for what might be, with many patients, difficult discussions.

Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

Most of us can recall medical innovations that fundamentally changed the way we practice and prescribe. Important revolutions do not need to be dramatic, such as the discovery and widespread use of low-molecular-weight heparin or the MRI, for us to be forever converted. For me, it was the discovery and widespread use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs).

In the 1970s, evidence emerged that the proton pump in stomach parietal cells was the last step in acid secretion. At the same time, preanesthetic screenings pointed to the antisecretory effects of a compound called timoprazole. Creative chemistry and side-chain substitutions led to the launch of omeprazole in 1990. The rest, as they say, is history.

PPIs are currently the third most commonly sold drugs in the Unite States, in large part because they transformed the care of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in a remarkable way.

In the early days, clinicians seemed inclined to start patients on the histamine receptor antagonists as first-line therapy, reserving PPIs for more recalcitrant cases. With time, however, clinicians reached for PPIs earlier in the course of therapy to more quickly eradicate symptoms. As the obesity epidemic spread, so too did the epidemic of GERD and PPI use.

What we seem to have lost sight of is that patients are being continued on these medications indefinitely. But at what risk?

Dr. Neena S. Abraham of Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Houston, and her colleagues, recently reviewed the literature on the long-term adverse health consequences of PPI use. She reported that the strongest evidence supports an increased risk for the development of Clostridium difficile infection and bone fracture. The mechanism of bone fracture relates to acid suppression and the "triple effect" of impairing the absorption of vitamin B12, which decreases osteoblastic activity; decreasing calcium absorption; and hypergastrinemia, which increases the release of parathyroid hormone contributing to bone resorption (Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 2012 [Epub ahead of print])

Dr. Abraham challenges us to prescribe PPIs only for "robust indications." We need to challenge ourselves to take the time to try tapering or discontinuation trials among patients who have been on them for a prolonged period of time. Informing patients of the long-term risks will arm us for what might be, with many patients, difficult discussions.

Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., is professor of medicine and primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He reports having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author.

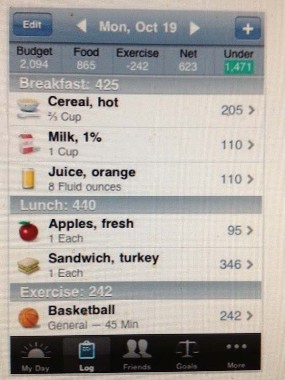

Computers for Weight Loss

Americans spend about $35 billion each year on weight loss products. The industry capitalizes on consumers failing with one weight loss intervention and moving onto the next. Competition abounds for the most outrageous claims since a large portion of this industry is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration.

There is no shortage of technology-based products that tout the ability to help patients lose weight. So when patients ask about these products, what should we say?

Virginia A. Reed, Ph.D., of Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., and her colleagues conducted a meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of computers for weight loss to help us answer this question. Studies were included if they were randomized, controlled clinical trials; the intervention included computer-based education or support aimed at reducing weight or body mass index; the comparison group received a non–computer-based intervention; participants were adults; and the study evaluated changes in weight and/or body mass index. Studies were excluded if they focused on weight maintenance (J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011;27:99-108).

Eleven randomized trials were included in the final analysis. In six studies, the computer-based tool was additional (that is, both groups received an identical intervention, but one group received an additional computer-based intervention), while five studies substituted a computer-based tool for a comparable intervention. Studies evaluated Web-based, computer-based, and handheld devices for self-monitoring of lifestyle and diet interventions. One study evaluated a wearable monitor.

When the computer-based intervention was additional, subjects in the computer-based tool group lost significantly more weight [weight mean difference (WMD) –1.48 kg; 95% confidence interval –2.52, –0.43]. Substituting a computer-based tool for a standard weight-loss intervention was not associated with significantly more weight loss. And interestingly, after removing one study from the analysis, substituting a computer-based tool for a standard weight-loss intervention was associated with significantly less weight loss (WMD 1.47 kg; 95% CI 0.13, 2.81).

The take home from this study is that computer technology is a great addition to weight-loss strategies, but a poor substitution for them. But as is often observed with the many available weight loss interventions, the effects are modest.

In general, factors found to be associated with successful long-term weight loss include long-term behavioral change and self-monitoring of weight. Many available computer programs are "one-dimensional" insofar as they address only weight monitoring or calorie intake but not both. The best advice for our patients may be to use a multimodal approach to weight loss that includes information about lifestyle change (such as, diet and exercise), calorie counting, and body-weight tracking.

Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., is a professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He declares having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Contact him at ebbert.jon@mayo.edu.

Americans spend about $35 billion each year on weight loss products. The industry capitalizes on consumers failing with one weight loss intervention and moving onto the next. Competition abounds for the most outrageous claims since a large portion of this industry is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration.

There is no shortage of technology-based products that tout the ability to help patients lose weight. So when patients ask about these products, what should we say?

Virginia A. Reed, Ph.D., of Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., and her colleagues conducted a meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of computers for weight loss to help us answer this question. Studies were included if they were randomized, controlled clinical trials; the intervention included computer-based education or support aimed at reducing weight or body mass index; the comparison group received a non–computer-based intervention; participants were adults; and the study evaluated changes in weight and/or body mass index. Studies were excluded if they focused on weight maintenance (J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011;27:99-108).

Eleven randomized trials were included in the final analysis. In six studies, the computer-based tool was additional (that is, both groups received an identical intervention, but one group received an additional computer-based intervention), while five studies substituted a computer-based tool for a comparable intervention. Studies evaluated Web-based, computer-based, and handheld devices for self-monitoring of lifestyle and diet interventions. One study evaluated a wearable monitor.

When the computer-based intervention was additional, subjects in the computer-based tool group lost significantly more weight [weight mean difference (WMD) –1.48 kg; 95% confidence interval –2.52, –0.43]. Substituting a computer-based tool for a standard weight-loss intervention was not associated with significantly more weight loss. And interestingly, after removing one study from the analysis, substituting a computer-based tool for a standard weight-loss intervention was associated with significantly less weight loss (WMD 1.47 kg; 95% CI 0.13, 2.81).

The take home from this study is that computer technology is a great addition to weight-loss strategies, but a poor substitution for them. But as is often observed with the many available weight loss interventions, the effects are modest.

In general, factors found to be associated with successful long-term weight loss include long-term behavioral change and self-monitoring of weight. Many available computer programs are "one-dimensional" insofar as they address only weight monitoring or calorie intake but not both. The best advice for our patients may be to use a multimodal approach to weight loss that includes information about lifestyle change (such as, diet and exercise), calorie counting, and body-weight tracking.

Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., is a professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He declares having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Contact him at ebbert.jon@mayo.edu.

Americans spend about $35 billion each year on weight loss products. The industry capitalizes on consumers failing with one weight loss intervention and moving onto the next. Competition abounds for the most outrageous claims since a large portion of this industry is not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration.

There is no shortage of technology-based products that tout the ability to help patients lose weight. So when patients ask about these products, what should we say?

Virginia A. Reed, Ph.D., of Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, N.H., and her colleagues conducted a meta-analysis evaluating the effectiveness of computers for weight loss to help us answer this question. Studies were included if they were randomized, controlled clinical trials; the intervention included computer-based education or support aimed at reducing weight or body mass index; the comparison group received a non–computer-based intervention; participants were adults; and the study evaluated changes in weight and/or body mass index. Studies were excluded if they focused on weight maintenance (J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2011;27:99-108).

Eleven randomized trials were included in the final analysis. In six studies, the computer-based tool was additional (that is, both groups received an identical intervention, but one group received an additional computer-based intervention), while five studies substituted a computer-based tool for a comparable intervention. Studies evaluated Web-based, computer-based, and handheld devices for self-monitoring of lifestyle and diet interventions. One study evaluated a wearable monitor.

When the computer-based intervention was additional, subjects in the computer-based tool group lost significantly more weight [weight mean difference (WMD) –1.48 kg; 95% confidence interval –2.52, –0.43]. Substituting a computer-based tool for a standard weight-loss intervention was not associated with significantly more weight loss. And interestingly, after removing one study from the analysis, substituting a computer-based tool for a standard weight-loss intervention was associated with significantly less weight loss (WMD 1.47 kg; 95% CI 0.13, 2.81).

The take home from this study is that computer technology is a great addition to weight-loss strategies, but a poor substitution for them. But as is often observed with the many available weight loss interventions, the effects are modest.

In general, factors found to be associated with successful long-term weight loss include long-term behavioral change and self-monitoring of weight. Many available computer programs are "one-dimensional" insofar as they address only weight monitoring or calorie intake but not both. The best advice for our patients may be to use a multimodal approach to weight loss that includes information about lifestyle change (such as, diet and exercise), calorie counting, and body-weight tracking.

Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., is a professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He declares having no conflicts of interest. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Contact him at ebbert.jon@mayo.edu.

Cranberry Juice for UTIs Update

Urinary tract infections are associated each year with 7 million U.S. office visits, over 100,000 hospitalizations, $1.6 billion in medical costs, and innumerable telephone calls and faxed prescriptions for patients in absentia.

Seems like every other week a clinical trial or meta-analysis is published on the benefits (or lack thereof) of cranberry juice for the prevention of urinary tract infections (UTIs). Many of us recommend it – or not – based on what we believe to be the true efficacy of this intervention and on how much we want to empower our patients to help us reduce antibiotic prescriptions in a world of increasing bacterial resistance. Data that support our views may be reviewed; those data that do not may be ignored.

Cranberries and cranberry juice have been recommended to patients for years. Originally, it was thought that it acidified the urine, but this theory has been refuted. More recent data suggest that the active ingredient in cranberry is the antiadhesion constituent proanthocyanidins (PACs). PACs appear to be able to wrap around E. coli and prevent adherence.

Dr. Chih-Hung Wang of the National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei and colleagues rose to the challenge and conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials of cranberry-containing products (juice, capsules, or tablets) for the prevention of UTIs. Thirteen trials were identified with 1,616 subjects. Most trials administered cranberry for 6 months. Cranberry users had a pooled lower risk for UTIs (odds ratio, 0.62; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.80). Cranberry products appeared to be more efficacious in women, women with recurrent UTIs, children, and cranberry juice users as opposed to users of cranberry tablets or capsules and when cranberry juice was consumed more than twice a day (Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:988-96).

What is the right dose? First, a couple of facts: approximately 1,500 g of fresh fruit produces 1 L of juice, and cranberry juice cocktail is roughly 26%-33% pure cranberry juice sweetened with fructose or artificial sweetener. Information on MedlinePlus suggests that cranberry juice doses of 1-10 ounces per day should be used for UTI prevention. Consuming 1 L/day may increase the risk for oxalate kidney stones. At 3-4 L/day, it may cause gastrointestinal distress. At reasonable doses, however, cranberry juice and tablets are very well tolerated and worth trying for our patients with recurrent UTIs.

Jon O. Ebbert, M.D., is professor of medicine and a primary care clinician at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. He is an investigator on a clinical trial investigating the safety of varenicline. The opinions expressed are solely those of the author. Contact him at ebbert.jon@mayo.edu.

Urinary tract infections are associated each year with 7 million U.S. office visits, over 100,000 hospitalizations, $1.6 billion in medical costs, and innumerable telephone calls and faxed prescriptions for patients in absentia.

Seems like every other week a clinical trial or meta-analysis is published on the benefits (or lack thereof) of cranberry juice for the prevention of urinary tract infections (UTIs). Many of us recommend it – or not – based on what we believe to be the true efficacy of this intervention and on how much we want to empower our patients to help us reduce antibiotic prescriptions in a world of increasing bacterial resistance. Data that support our views may be reviewed; those data that do not may be ignored.

Cranberries and cranberry juice have been recommended to patients for years. Originally, it was thought that it acidified the urine, but this theory has been refuted. More recent data suggest that the active ingredient in cranberry is the antiadhesion constituent proanthocyanidins (PACs). PACs appear to be able to wrap around E. coli and prevent adherence.

Dr. Chih-Hung Wang of the National Taiwan University Hospital in Taipei and colleagues rose to the challenge and conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials of cranberry-containing products (juice, capsules, or tablets) for the prevention of UTIs. Thirteen trials were identified with 1,616 subjects. Most trials administered cranberry for 6 months. Cranberry users had a pooled lower risk for UTIs (odds ratio, 0.62; 95% confidence interval, 0.49-0.80). Cranberry products appeared to be more efficacious in women, women with recurrent UTIs, children, and cranberry juice users as opposed to users of cranberry tablets or capsules and when cranberry juice was consumed more than twice a day (Arch. Intern. Med. 2012;172:988-96).

What is the right dose? First, a couple of facts: approximately 1,500 g of fresh fruit produces 1 L of juice, and cranberry juice cocktail is roughly 26%-33% pure cranberry juice sweetened with fructose or artificial sweetener. Information on MedlinePlus suggests that cranberry juice doses of 1-10 ounces per day should be used for UTI prevention. Consuming 1 L/day may increase the risk for oxalate kidney stones. At 3-4 L/day, it may cause gastrointestinal distress. At reasonable doses, however, cranberry juice and tablets are very well tolerated and worth trying for our patients with recurrent UTIs.