User login

‘Screen-time transferential interference’ in encounters with patients

I cannot recall the last time that I had a good look at the cashier who was scanning my grocery purchases. I could not tell you what color eyes he (or she?) had or how he styled his hair. This isn’t for lack of an effort to recall, or a manifestation of poor memory or absentmindedness. Rather, I think that the situation reflects a larger cultural shift that has gained momentum since the beginning of the new century: that is, the effect of a preponderance of so-called screen time in our lives.

In that mundane scene in the grocery store, screen time encompasses the impersonal and mechanical act of swiping my debit card, entering my PIN, and impatiently waiting for the receipt to print. All the while, I stand awkwardly, eyes downcast and fixed on the display of the card reader, ignoring the human being directly across from me.

Obsession with screens

Our engagement with screen time has grown to pandemic proportions, and television is no longer the main culprit. According to a Nielsen global consumer report,1 in 2010 in the United States, people spent an average of 5 hours a day in front of the “boob tube.” Even if we take that statistic with a grain of salt, it still represents only the most visible tip of the media iceberg. Smartphones, laptop and desktop monitors, portable gaming consoles, electronic tablets, PIN pad displays, video billboards, and any number of other LED and LCD screen surfaces have infiltrated the landscape.

Whereas most recent epidemiologic studies have addressed the deleterious effects of so-called sit time (sedentary activities with or without a screen) on physical health, I would like to address the deleterious effect of screen time on mental health and relational connectedness and the relevance of that screen time to psychiatric practice.

The ‘techno-bubble of private space’

Almond,2 in a humorous social commentary, “Connection Error,” conducted an impromptu experiment in which he attempted to connect spontaneously with strangers, especially those who had a smartphone, in Boston. His narrative navigates the gamut of human interaction, from tedious and boorish to comedic and absurd, noting that, conspicuously, “smartphone users have created a techno-bubble of private space” in which they are physically present but emotionally unavailable.

A chance encounter with a young professional led Almond to this conclusion:

It’s precisely the intrusive alienation of the “techno-bubble” that blunders into the modern patient-physician interaction in my clinical psychiatric practice in a busy outpatient clinic at a university medical center. Specifically, the ever-glowing, ever-distracting computer monitor sitting between me and my patient, with its promise of digital information at my fingertips, serves more to distance me from my patient than to connect us in a meaningful, human way. Just as I can’t recall the countenance of the grocery-store cashier, I miss the delicate, information-laden, minute-to-minute social interaction with the patient because it competes with the electronic intruder.

What’s at risk when a computer screen is in the room?

Transference in the psychotherapeutic encounter is an established tenet of psychoanalytic theory. In “Basic theory of psychoanalysis,”3 Waelder defines transference as “not simply the attribution to new objects of characteristics of old ones but the attempt to re-establish and relive, with whatever object will permit it, an infantile situation much longed for because it was once either greatly enjoyed or greatly missed.” This definition applies to the positive pole of transferential phenomena—and it is this position that is desired in a successful patient−physician encounter.

A patient’s warm and genial regard toward a provider secures trust, cooperation, and faith in the healing process. Establishment of positive transference toward the physician is essential to enhance the clinical encounter, regardless of what early object (caring mother, omnipotent father) is being projected onto the physician.

Attunement. Research into infant observation has revealed the critical role of caretaker responsiveness in the development of early infantile emotional regulation. Tronick et al4 demonstrated the importance of interactional reciprocity in the mother−child dyad.

In a series of experiments using the so-called still-face paradigm, Tronick et al4 saw that infants quickly fall into a state of despair and related negative affects when the mother assumes an unresponsive and detached still face. These episodes intentionally produce infant-mother emotional misattunement, which, although instantly damaging, can be successfully repaired through re-attunement by the mother. It is the primary caretaker’s ability to reconnect and repair that is paramount to the infant’s healthy psychological development.

This sentiment is echoed in Winnicott’s concept of the “good-enough” mother (or parent), formulated years earlier, in which failures in infant−caretaker attunement are inevitable and to be expected—as long as repair outcompetes deficiency.5

Divided attention: Patient or screen? Or both?

What we can understand by applying the ideas of transference and optimal attunement to the clinical encounter is how important uninterrupted face-to-face time with the patient is. Indeed, nonverbal communication from the patient, expressed though body language and facial articulation, is particularly salient to the practice of psychiatry. Information technology— especially the electronic health record—now encroaches on the time-honored central dyad of the patient-physician interaction by introducing a third entity into the traditional encounter.

Clinical misattunement, as understood through the still-face paradigm, increases in proportion to a provider’s need to divide his (her) attention between the patient and the computer screen. And, as the degree of misattunement increases, positive transference is more difficult to establish and maintain. The quality of the clinical encounter then deteriorates, undermining the care of the patient and reducing physician satisfaction.

Acknowledgment

Philip LeFevre, MD, Department of Neurology & Psychiatry, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri, provided inspiration and encouragement in the development of the manuscript.

Disclosure

Dr. Afanasevich reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. The Nielsen Company. How people watch: a global Nielsen consumer report. http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/ corporate/mx/reports/2011/Lo-que-la-gente-ve.pdf. Published August 2010. Accessed March 17, 2015.

2. Almond S. Connection error. Spirit Magazine. April 2014:76-86.

3. Waelder R. Basic theory of psychoanalysis. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1960.

4. Tronick E, Als H, Adamson L, et al. The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face interaction. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1978;17(1):1-13.

5. Winnicott DW. The child, the family, and the outside world. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books; 1964.

I cannot recall the last time that I had a good look at the cashier who was scanning my grocery purchases. I could not tell you what color eyes he (or she?) had or how he styled his hair. This isn’t for lack of an effort to recall, or a manifestation of poor memory or absentmindedness. Rather, I think that the situation reflects a larger cultural shift that has gained momentum since the beginning of the new century: that is, the effect of a preponderance of so-called screen time in our lives.

In that mundane scene in the grocery store, screen time encompasses the impersonal and mechanical act of swiping my debit card, entering my PIN, and impatiently waiting for the receipt to print. All the while, I stand awkwardly, eyes downcast and fixed on the display of the card reader, ignoring the human being directly across from me.

Obsession with screens

Our engagement with screen time has grown to pandemic proportions, and television is no longer the main culprit. According to a Nielsen global consumer report,1 in 2010 in the United States, people spent an average of 5 hours a day in front of the “boob tube.” Even if we take that statistic with a grain of salt, it still represents only the most visible tip of the media iceberg. Smartphones, laptop and desktop monitors, portable gaming consoles, electronic tablets, PIN pad displays, video billboards, and any number of other LED and LCD screen surfaces have infiltrated the landscape.

Whereas most recent epidemiologic studies have addressed the deleterious effects of so-called sit time (sedentary activities with or without a screen) on physical health, I would like to address the deleterious effect of screen time on mental health and relational connectedness and the relevance of that screen time to psychiatric practice.

The ‘techno-bubble of private space’

Almond,2 in a humorous social commentary, “Connection Error,” conducted an impromptu experiment in which he attempted to connect spontaneously with strangers, especially those who had a smartphone, in Boston. His narrative navigates the gamut of human interaction, from tedious and boorish to comedic and absurd, noting that, conspicuously, “smartphone users have created a techno-bubble of private space” in which they are physically present but emotionally unavailable.

A chance encounter with a young professional led Almond to this conclusion:

It’s precisely the intrusive alienation of the “techno-bubble” that blunders into the modern patient-physician interaction in my clinical psychiatric practice in a busy outpatient clinic at a university medical center. Specifically, the ever-glowing, ever-distracting computer monitor sitting between me and my patient, with its promise of digital information at my fingertips, serves more to distance me from my patient than to connect us in a meaningful, human way. Just as I can’t recall the countenance of the grocery-store cashier, I miss the delicate, information-laden, minute-to-minute social interaction with the patient because it competes with the electronic intruder.

What’s at risk when a computer screen is in the room?

Transference in the psychotherapeutic encounter is an established tenet of psychoanalytic theory. In “Basic theory of psychoanalysis,”3 Waelder defines transference as “not simply the attribution to new objects of characteristics of old ones but the attempt to re-establish and relive, with whatever object will permit it, an infantile situation much longed for because it was once either greatly enjoyed or greatly missed.” This definition applies to the positive pole of transferential phenomena—and it is this position that is desired in a successful patient−physician encounter.

A patient’s warm and genial regard toward a provider secures trust, cooperation, and faith in the healing process. Establishment of positive transference toward the physician is essential to enhance the clinical encounter, regardless of what early object (caring mother, omnipotent father) is being projected onto the physician.

Attunement. Research into infant observation has revealed the critical role of caretaker responsiveness in the development of early infantile emotional regulation. Tronick et al4 demonstrated the importance of interactional reciprocity in the mother−child dyad.

In a series of experiments using the so-called still-face paradigm, Tronick et al4 saw that infants quickly fall into a state of despair and related negative affects when the mother assumes an unresponsive and detached still face. These episodes intentionally produce infant-mother emotional misattunement, which, although instantly damaging, can be successfully repaired through re-attunement by the mother. It is the primary caretaker’s ability to reconnect and repair that is paramount to the infant’s healthy psychological development.

This sentiment is echoed in Winnicott’s concept of the “good-enough” mother (or parent), formulated years earlier, in which failures in infant−caretaker attunement are inevitable and to be expected—as long as repair outcompetes deficiency.5

Divided attention: Patient or screen? Or both?

What we can understand by applying the ideas of transference and optimal attunement to the clinical encounter is how important uninterrupted face-to-face time with the patient is. Indeed, nonverbal communication from the patient, expressed though body language and facial articulation, is particularly salient to the practice of psychiatry. Information technology— especially the electronic health record—now encroaches on the time-honored central dyad of the patient-physician interaction by introducing a third entity into the traditional encounter.

Clinical misattunement, as understood through the still-face paradigm, increases in proportion to a provider’s need to divide his (her) attention between the patient and the computer screen. And, as the degree of misattunement increases, positive transference is more difficult to establish and maintain. The quality of the clinical encounter then deteriorates, undermining the care of the patient and reducing physician satisfaction.

Acknowledgment

Philip LeFevre, MD, Department of Neurology & Psychiatry, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri, provided inspiration and encouragement in the development of the manuscript.

Disclosure

Dr. Afanasevich reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

I cannot recall the last time that I had a good look at the cashier who was scanning my grocery purchases. I could not tell you what color eyes he (or she?) had or how he styled his hair. This isn’t for lack of an effort to recall, or a manifestation of poor memory or absentmindedness. Rather, I think that the situation reflects a larger cultural shift that has gained momentum since the beginning of the new century: that is, the effect of a preponderance of so-called screen time in our lives.

In that mundane scene in the grocery store, screen time encompasses the impersonal and mechanical act of swiping my debit card, entering my PIN, and impatiently waiting for the receipt to print. All the while, I stand awkwardly, eyes downcast and fixed on the display of the card reader, ignoring the human being directly across from me.

Obsession with screens

Our engagement with screen time has grown to pandemic proportions, and television is no longer the main culprit. According to a Nielsen global consumer report,1 in 2010 in the United States, people spent an average of 5 hours a day in front of the “boob tube.” Even if we take that statistic with a grain of salt, it still represents only the most visible tip of the media iceberg. Smartphones, laptop and desktop monitors, portable gaming consoles, electronic tablets, PIN pad displays, video billboards, and any number of other LED and LCD screen surfaces have infiltrated the landscape.

Whereas most recent epidemiologic studies have addressed the deleterious effects of so-called sit time (sedentary activities with or without a screen) on physical health, I would like to address the deleterious effect of screen time on mental health and relational connectedness and the relevance of that screen time to psychiatric practice.

The ‘techno-bubble of private space’

Almond,2 in a humorous social commentary, “Connection Error,” conducted an impromptu experiment in which he attempted to connect spontaneously with strangers, especially those who had a smartphone, in Boston. His narrative navigates the gamut of human interaction, from tedious and boorish to comedic and absurd, noting that, conspicuously, “smartphone users have created a techno-bubble of private space” in which they are physically present but emotionally unavailable.

A chance encounter with a young professional led Almond to this conclusion:

It’s precisely the intrusive alienation of the “techno-bubble” that blunders into the modern patient-physician interaction in my clinical psychiatric practice in a busy outpatient clinic at a university medical center. Specifically, the ever-glowing, ever-distracting computer monitor sitting between me and my patient, with its promise of digital information at my fingertips, serves more to distance me from my patient than to connect us in a meaningful, human way. Just as I can’t recall the countenance of the grocery-store cashier, I miss the delicate, information-laden, minute-to-minute social interaction with the patient because it competes with the electronic intruder.

What’s at risk when a computer screen is in the room?

Transference in the psychotherapeutic encounter is an established tenet of psychoanalytic theory. In “Basic theory of psychoanalysis,”3 Waelder defines transference as “not simply the attribution to new objects of characteristics of old ones but the attempt to re-establish and relive, with whatever object will permit it, an infantile situation much longed for because it was once either greatly enjoyed or greatly missed.” This definition applies to the positive pole of transferential phenomena—and it is this position that is desired in a successful patient−physician encounter.

A patient’s warm and genial regard toward a provider secures trust, cooperation, and faith in the healing process. Establishment of positive transference toward the physician is essential to enhance the clinical encounter, regardless of what early object (caring mother, omnipotent father) is being projected onto the physician.

Attunement. Research into infant observation has revealed the critical role of caretaker responsiveness in the development of early infantile emotional regulation. Tronick et al4 demonstrated the importance of interactional reciprocity in the mother−child dyad.

In a series of experiments using the so-called still-face paradigm, Tronick et al4 saw that infants quickly fall into a state of despair and related negative affects when the mother assumes an unresponsive and detached still face. These episodes intentionally produce infant-mother emotional misattunement, which, although instantly damaging, can be successfully repaired through re-attunement by the mother. It is the primary caretaker’s ability to reconnect and repair that is paramount to the infant’s healthy psychological development.

This sentiment is echoed in Winnicott’s concept of the “good-enough” mother (or parent), formulated years earlier, in which failures in infant−caretaker attunement are inevitable and to be expected—as long as repair outcompetes deficiency.5

Divided attention: Patient or screen? Or both?

What we can understand by applying the ideas of transference and optimal attunement to the clinical encounter is how important uninterrupted face-to-face time with the patient is. Indeed, nonverbal communication from the patient, expressed though body language and facial articulation, is particularly salient to the practice of psychiatry. Information technology— especially the electronic health record—now encroaches on the time-honored central dyad of the patient-physician interaction by introducing a third entity into the traditional encounter.

Clinical misattunement, as understood through the still-face paradigm, increases in proportion to a provider’s need to divide his (her) attention between the patient and the computer screen. And, as the degree of misattunement increases, positive transference is more difficult to establish and maintain. The quality of the clinical encounter then deteriorates, undermining the care of the patient and reducing physician satisfaction.

Acknowledgment

Philip LeFevre, MD, Department of Neurology & Psychiatry, Saint Louis University, St. Louis, Missouri, provided inspiration and encouragement in the development of the manuscript.

Disclosure

Dr. Afanasevich reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. The Nielsen Company. How people watch: a global Nielsen consumer report. http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/ corporate/mx/reports/2011/Lo-que-la-gente-ve.pdf. Published August 2010. Accessed March 17, 2015.

2. Almond S. Connection error. Spirit Magazine. April 2014:76-86.

3. Waelder R. Basic theory of psychoanalysis. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1960.

4. Tronick E, Als H, Adamson L, et al. The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face interaction. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1978;17(1):1-13.

5. Winnicott DW. The child, the family, and the outside world. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books; 1964.

1. The Nielsen Company. How people watch: a global Nielsen consumer report. http://www.nielsen.com/content/dam/ corporate/mx/reports/2011/Lo-que-la-gente-ve.pdf. Published August 2010. Accessed March 17, 2015.

2. Almond S. Connection error. Spirit Magazine. April 2014:76-86.

3. Waelder R. Basic theory of psychoanalysis. New York, NY: International Universities Press; 1960.

4. Tronick E, Als H, Adamson L, et al. The infant’s response to entrapment between contradictory messages in face-to-face interaction. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1978;17(1):1-13.

5. Winnicott DW. The child, the family, and the outside world. London, United Kingdom: Penguin Books; 1964.

Trading in work-life balance for a well-balanced life

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.

Dr. Schmidt, a second-year psychiatry resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is interested in psychodynamic therapy and in pursuing a fellowship in addictions. After obtaining a bachelor of arts at the University of California, Berkeley, she earned a master of arts degree in philosophy and humanities at the University of Chicago. She attended medical school at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria.

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.

Dr. Schmidt, a second-year psychiatry resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is interested in psychodynamic therapy and in pursuing a fellowship in addictions. After obtaining a bachelor of arts at the University of California, Berkeley, she earned a master of arts degree in philosophy and humanities at the University of Chicago. She attended medical school at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria.

My residency supervisor candidly asked me today – Isn’t stressing out about writing an article on work-life balance kind of missing the point? Well, yeah, that’s why she’s my supervisor. This brings me to one of the lesser advertised tips to avoiding burnout, which is: Get yourself a great mensch. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. The plan was to have 10 perfectly delineated rules, because if it worked for Letterman and Moses, it should work for residency. More to come on that.

Another part of the plan was to have this article finished by last weekend, but long call was Saturday. This was followed by long call recovery consisting of sleeping in so late my dad texted and left a voicemail asking, what happened? I haven’t heard from you all weekend. Then there was the obligatory run on the treadmill so the gooey cinnamon rolls the nurses baked and generously invited me to on Thursday would not stick around long enough for my husband to wonder if this was the beginning of me letting myself go. Isn’t that a lovely phrase?

Monday was Monday. How does anyone get anything done on Mondays? I had a new team, two new patients to learn and discharge. Plus, it was the first day that cracked 50 degrees in 5 months. I had to meet up with a friend, grab some coffee, and gossip walk around the lake. This was before we found out another friend was being slammed with consults in the emergency room. So there I was right back at the hospital Monday night with a cream cheese cherry pastry to cheer up my compatriot in the struggle.

This brings me to Tuesday. I had planned to be at the editing stage of this article on Tuesday. But didactics ran long due to everyone being so engaged in our formulations lecture, I didn’t have a shot at looking at this thing until lunchtime. Lunchtime came, and as I opened Microsoft Word among my dollar turkey sandwich and mini Purell bottles stationed around me like glorious little sergeants, I heard the gingerly utterings of a medical student: Um, if you have a moment, could you tell me the difference between the side-effect profile of first-generation and second-generation antipsychotics?

An hour later, I was informed that an admit was on the way and was traveling from out of state, set to arrive a half-hour before shift’s end. Did I mention he arrived with two family members in tow who wanted to talk about how things went wrong starting 20 years ago? Then there was the patient to see who I knew would pout if I didn’t spend at least a half-hour checking in. You know, the one the nurses always try to save me from even though I secretly never wanted to be saved.

I finally drove home 2 hours later than anticipated with a smile on my face. I should repeat that, WITH A SMILE ON MY FACE. I felt good because I’d done good. After all, there’s even a little sunlight left. When I walk in the front door, I kiss my husband and then immediately delve into a new story from the day. We laugh. We warm up leftovers, sit on the couch with our bare feet on the table, and catch an hour of American Idol (talent never gets old). Then it’s time to meet this maker.

The strange thing is, the person who began this column with all of her well-intentioned plans feels very different from the person who has made it to the deadline. There is a whole life lived in between. All of the readings I had done, notations I had made, seem kind of beside the point. I could pepper you with statistics and evidence-based outcomes warning of divorce, substance abuse, physician suicide, patient errors, and the like, which are all very real outcomes of poorly balanced lives. But I think we know all of that. It’s the in between space, the living part where so many of us lose our way. So instead of referenced journals, I offer you my journey. Because I can truly say that for the last 3 months of the most difficult year of residency, I have been happy. May this piece be also with you.

Dr. Schmidt, a second-year psychiatry resident at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., is interested in psychodynamic therapy and in pursuing a fellowship in addictions. After obtaining a bachelor of arts at the University of California, Berkeley, she earned a master of arts degree in philosophy and humanities at the University of Chicago. She attended medical school at the University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria.

The patient refuses to cooperate. What can you do? What should you do?

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Should the use of ‘endorse’ be endorsed in writing in psychiatry?

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

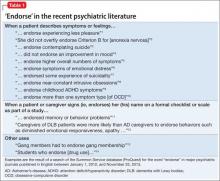

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The word “endorse” often appears in the medical literature and is heard in oral presentations; psychiatrists use the term to mean that a person is reporting psychiatric symptoms or problems. However, such usage may be a stylistic catachresis—one that has the potential for misinterpretation or misunderstanding.

Finding ‘endorse’ in the psychiatric literature

We conducted a literature search to identify instances of “endorse” in scholarly articles published in psychiatric journals between January 1, 2012, and November 25, 2013. Table 11-14 shows examples of typical uses of “endorse” in recent publications.

Even when “endorse” is used as a synonym for “report” or “describe,” use of the word in that context can seem out of place. We could not find any rationale in the medical literature for using “endorse” as a synonym for “report” or “describe.”

The definition of “endorse” in Merriam-Webster15 and Oxford Dictionaries16 includes:

• inscribing or signing a legal document, check, or bill

• approving or recommending an idea, product, or candidate.

We believe that using “endorse” in a psychiatric context could create confusion among medical trainees and professionals who are familiar with the correct meanings of the word.

Survey: Some residents use ‘endorse’ in oral presentations

We asked residents in the Department of Psychiatry at Drexel University College of Medicine to respond to a questionnaire regarding their understanding of the use of “endorse.” Their responses are summarized in Table 2.

What is wrong with using ‘endorse’? Except when “endorse” describes a patient formally affixing her (his) signature to a document for the purpose of (1) certification or (2) giving or showing one’s support for a cause, we think that use of the word in psychiatry is not in keeping with its formal, accepted definition. Furthermore, residents’ responses to our survey suggest that there is the danger of causing confusion in using the word“endorse” when “report” or “describe” is meant.

For example, if a patient “endorses” antisocial behavior, is she stating that she feels justified in exhibiting such behavior? Do students who “endorse” drug use approve of drug use? Another example: Youth who “endorse” gang membership have merely confirmed that they belonged to a gang at some time.

The intended meaning of “endorse” in these examples is probably closer to “admit” or “acknowledge.” The patient replies “yes” when the physician asks if she uses drugs or has had behavior problems; she is not necessarily recommending or approving these behaviors.

Usage is shifting. In the past, “complain” was common medical parlance for a patient’s report of symptoms or other health-related problems. In fact, medical, surgical, and psychiatric evaluations still begin with a “chief complaint” section. It’s possible that, because “complaint” might suggest that the patient is whining, the word fell out of favor in the medical lexicon and was replaced in the scholarly literature by the construction “the patient reports….”

Avoid jargon. Employ accurate terminology

We propose that “endorse,” like “complain,” is a cant of psychiatrists. We recommend that, when describing a patient’s statement or report of symptoms or experiences, practitioners should avoid “endorse” and write or say “report,” “express,” “exhibit,” or similar words. Using accurate terminology and avoiding imprecise or misleading jargon is not only linguistically appropriate but also can help avoid misunderstanding and improve patient care.

Acknowledgment

Diana Winters, Academic Publishing Services, Drexel University College of Medicine, provided editorial assistance in preparing the manuscript of this article and offered comment on the use of medical jargon.

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

1. Strauss GP, Gold JM. A new perspective on anhedonia in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(4):364-373.

2. Thomas JJ, Weigel TJ, Lawton RK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of body image disturbance in a congenitally blind patient with anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(1):16-20.

3. Purcell B, Heisel MJ, Speice J, et al. Family connectedness moderates the association between living alone and suicide ideation in a clinical sample of adults 50 years and older. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(8):717-723.

4. Dakin EK, Areán P. Patient perspectives on the benefits of psychotherapy for late-life depression. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(2):155-163.

5. Mezuk B, Lohman M, Dumenci, L, et al. Are depression and frailty overlapping syndromes in mid- and late-life? A latent variable analysis. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):560-569.

6. Boindala NS, Tucker P, Trautman RP. “Culture and psychiatry”: a course for second-year psychiatry residents. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(1):46-50.

7. Henry A, Kisicki MD, Varley C. Efficacy and safety of antidepressant drug treatment in children and adolescents. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(12):1186-1193.

8. Rodriguez CI, Kegeles LS, Levinson A, et al. A randomized controlled crossover trial of ketamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder (abstract W7). Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;38:S317.

9. Whelan R, Garavan H. Fractionating the impulsivity construct in adolescence. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(1):250-251.

10. Rück C, Larsson KJ, Mataix-Cols D. Predictors of medium and long-term outcome following capsulotomy for obsessive-compulsive disorder: one site may not fit all. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):406-414.

11. Mausbach BT, Chattillion EA, Roepke SK, et al. A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(1):5-13.

12. Peavy GM, Salmon DP, Edland SD, et al. Neuropsychiatric features of frontal lobe dysfunction in autopsy-confirmed patients with lewy bodies and “pure” Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2013;21(6):509-519.

13. Coid JW, Ullrich S, Keers R, et al. Gang membership, violence, and psychiatric morbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):985-993.

14. Choi D, Tolova V, Socha E, et al. Substance use and attitudes on professional conduct among medical students: a single-institution study. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(3):191-195.

15. Endorse. Merriam-Webster. http://www.merriam-webster. com/dictionary/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

16. Endorse. Oxford Dictionaries. http://www.oxforddictionaries. com/definition/english/endorse. Accessed January 14, 2014.

Discharging your patient: A complex process

Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

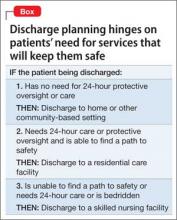

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility

Keep financing in mind

The patient’s ability to pay, as well as having access to insurance or a financial assistance program, is a major contributing factor in discharge planning. All financial options need to be considered by the physicians leading the discharge planning team.

Neither Medicaid nor Medicare benefits are available to pay rent; these insurance programs pay for medical services only. Medicaid does provide some money for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings (such assistance is arranged through, and provided by, home health care agencies) and to Medicaid-eligible residents of an assisted living facility.

Medicaid covers 100% of a nursing home stay for an eligible resident. Medicare might cover the cost of skilled-nursing facility care if the placement falls under the criterion of an “episode of care.”

It is worth mentioning that some Veterans’ Administration money might be available to a veteran or his (her) surviving spouse for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings or if he (she) is institutionalized. Other local programs might provide eligible recipients with long-term care services; discharge social workers, as members of the multidisciplinary team, usually are resourceful at identifying such programs.

All in all, a complex project