User login

MINIDEP: A simple, self-administered depression screening tool

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Depression is a debilitating illness, and many cases go unrecognized and untreated. There are several depression inventories and questionnaires available for practitioners’ use, but many are long or require a specially trained rater or administrator.1-10

One well-known depression screening questionnaire is the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). This instrument is a combination of a 2-item questionnaire and, if the 2-item questionnaire is positive, a 7-item questionnaire.2,3 Even if the PHQ-9 is used, it requires a trained healthcare professional to administer it, limiting its use.

On the other hand, the MINIDEP depression screening tool that I developed can be self-administered by the patient either online or while he (she) is in the waiting room. It can be used by any health care specialist (psychiatrist, psychologist, family practitioner, etc.) as part of the patient’s evaluation.

Unlike most conventional screening questionnaires, MINIDEP has only 7 questions but covers most of the DSM-5 criteria for major depressive disorder. It also includes a question on unexplained pains or aches, which often is the only symptom that patients report, but is absent in the PHQ-9 and in other screening questionnaires.

Having a simple, easy-to-remember mnemonic means that this questionnaire can be used by medical students, residents, allied health and mental health professionals, and primary care physicians to screen for depression in the community.11

MINIDEP Categories/areas of concern addressed

Mood (lowered) and emotional lability.

Interest and desires (anhedonia).

Nutrition, poor appetite, and weight loss or gain.

Insomnia or hypersomnia.

Death or dying (thinking of), feeling worthless or guilty, or making suicidal plans.

Energy (decreased), impaired daily activities, and worsened cognitive ability.

Pains and aches (in absence of unexplained medical illnesses).

I propose rating scores for this questionnaire (Figure) as follows:

0 to 3 Points: Patient is not clinically depressed. Evaluation by a mental health professional might be unnecessary.

4 to 9 Pointsa: Depression is suspected. Further evaluation by a mental health professional (not necessarily a psychiatrist) is warranted.

aThorough psychiatric evaluation also is warranted if the patient has scored 4 to 9 points, with at least 1 point from Question 5.

≥10 points: Depression is confirmed. The patient should be evaluated by a psychiatrist for suicidal thoughts.

Note that this proposed rating scale is based on my experience, although I believe it could be useful. To increase this screening tool’s sensitivity, in my experience, evaluation by a mental health professional might be necessary when a patient scores only 3 points on MINIDEP. The optimal number of points for triggering a clinical decision and this questionnaire’s sensitivity and specificity, however, need to be studied.

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

1. Depression in adults: screening. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Topic/recommendation-summary/depressionin-adults-screening. Updated July 2015. Accessed October 2, 2015.

2. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. http://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/PHQ%20-%20Questions.pdf. Published October 4, 2005. Accessed September 30, 2015.

3. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 & PHQ-2). American Psychological Association. http://www.apa.org/pi/about/publications/caregivers/practice-settings/assessment/tools/patient-health.aspx. Accessed October 2, 2015.

4. Online assessment measures. American Psychiatric Association. http://www.psychiatry.org/practice/dsm/dsm5/online-assessment-measures#Disorder. Accessed October 2, 2015.

5. Depression screening. Mental Health America. http://www.mentalhealthamerica.net/mental-health-screen/patient-health. Accessed October 2, 2015.

6. Major Depressive Disorder Diagnostic Criteria—SIGE CAPS. Family Medicine Reference. http://www.fammedref.org/mnemonic/major-depressive-disorder-

diagnostic-criteria-sigme-caps. Accessed October2, 2015.

7. Welcome to the Wakefield Self-Report Questionnaire, a screening test for depression. Counselling Resource. http://counsellingresource.com/lib/quizzes/depression-testing/wakefield. Accessed October 2, 2015.

8. Goldberg’s Depression and Mania Self-Rating Scales. Psy-World. http://www.psy-world.com/goldberg.htm. Published 1993. Accessed October 2, 2015.

9. Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385-401.

10. Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63-70.

11. Graypel EA. MINIDEP. http://www.minidep.com. Accessed October 2, 2015.

The patient refuses to cooperate. What can you do? What should you do?

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

The real estate business embraces the concept of ownership using the term “bundle of rights.” Real estate agents view full, unaffected ownership of a real property as complete (ie, undivided) and, when ownership is shared, talk about percentages of that bundle.

The same principle can be applied to guardianship. Because we are our own guardians, we own a full, undivided bundle of rights, including all our constitutional rights and the right to make decisions— even bad ones. Of course, an undivided bundle also means that we are fully responsible for the decisions we make.

When a patient requires representation

There may be a situation when we would give someone else the authority to represent us for a specific reason. In this case we would authorize this person to act on our behalf as we would do ourselves—yet we still retain 100% ownership of the “bundle,” and therefore can revoke this authorization at any time. The person we hire (appoint) to represent us will become our power of attorney (POA), and because we appoint this person for a specific situation (handle certain medical affairs, manage some financial affairs, sign real estate documents, etc.), this kind or POA is called “specific” or “special.” When we give someone the right to represent us in any or all of our affairs, this POA is called “general” or “durable.”

It is important to mention that as long as we continue to have psychological capacity and are willing to continue to be our own guardians (own 100% of the bundle of rights), we can terminate any POA we have appointed previously or designate another person to represent us as a “special” or “general” POA. Because of this, if an older patient—who is legally competent but physically unable to live on his (her) own— refuses to enter a long-term care facility, he (she) cannot be sent there against his will, even if the POA insists on it. Because of this, if the patient’s primary team strongly disagrees with this patient’s decision, his (her) “decision-making capacity” should be assessed and, if necessary, a competency hearing will need to be conducted. The court will then decide if this person is able (or unable) to handle his own affairs, and if the court decides that the person cannot be responsible to provide himself with food, health care, housing, and other necessities, the guardian (relative, friend, public administrator, etc.) will be appointed to do so.

Evaluating decision-making capacity

Determining “decision-making capacity” should not be confused with the legal concept of “competence.” We, physicians, often are called to evaluate a patient and give our opinion of the current level of this patient’s functioning (including his [her] decision-making capacity), and we—ourselves and a requesting team—need to be clear that it is merely our opinion and should be used as such. We need to remember that even if a patient is judged to be legally incompetent to handle financial affairs, he (she) might retain sufficient ability to make decisions about treatments.

We also need to remember that decision-making capacity can change, depending on medical conditions (severe anxiety, delirium), successful treatments, substance intoxication, etc. Because of this, we need to communicate to the requesting team that “decision-making ability” is situation-specific and time-specific, and that failure to make a decision on one issue should not be generalized to other aspects of the patient’s life.

Any physician can evaluate patient’s decision-making ability, but traditionally the psychiatry team is called to do so. It usually happens because the primary medical team needs us to provide “a third-party validation,” or because of the common misperception that only the psychiatric team can initiate a civil involuntary detention when necessary.

In any case, regardless of who evaluates the patient, specific points need to be addressed and the following questions need to be answered:

• Does the patient understand the nature of his (her) condition?

• Does the patient understand what treatment we are proposing or what he should do?

• Does the patient understand the consequences (good or bad) if he rejects our proposed action or treatment?

When information (discharge plan, treatment plan, etc.) is presented to patients, we should ask them to repeat it in their own words. We should not expect them to understand all of the technical aspects. We should consider patients’ intelligence level and their ability to communicate; if they can clearly verbalize their understanding of information and be consistent in their wish to continue with their decision, we have to declare that they have decision-making capability and able to proceed with their chosen treatment.

More matters that need to be mentioned

Restrictions on the patient. We need to remember that, even if a patient is thought to be able to make his own decisions, there may be some situations when he can be held in the hospital against his will. These usually are the cases when the patient is psychiatrically or medically unstable (unable to care of himself), but also if the patient is at risk of harming himself or others, subject of elder abuse, or suspected of being an abuser.

Restrictions on the practitioner. Even if the patient is determined to be lacking decision-making capacity, we, physicians, cannot perform tests, procedures, or do the placements without the patient’s agreement.

Informed consent doctrine is applicable in this case, and if performing a test or procedure is necessary (except life- or limb-saving emergencies, when doctrine of physician prerogative applies), or if there a disagreement in post-discharge placement, the emergency guardianship may need to be pursued.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discharging your patient: A complex process

Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

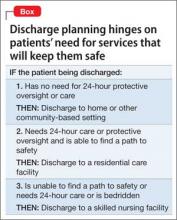

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility

Keep financing in mind

The patient’s ability to pay, as well as having access to insurance or a financial assistance program, is a major contributing factor in discharge planning. All financial options need to be considered by the physicians leading the discharge planning team.

Neither Medicaid nor Medicare benefits are available to pay rent; these insurance programs pay for medical services only. Medicaid does provide some money for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings (such assistance is arranged through, and provided by, home health care agencies) and to Medicaid-eligible residents of an assisted living facility.

Medicaid covers 100% of a nursing home stay for an eligible resident. Medicare might cover the cost of skilled-nursing facility care if the placement falls under the criterion of an “episode of care.”

It is worth mentioning that some Veterans’ Administration money might be available to a veteran or his (her) surviving spouse for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings or if he (she) is institutionalized. Other local programs might provide eligible recipients with long-term care services; discharge social workers, as members of the multidisciplinary team, usually are resourceful at identifying such programs.

All in all, a complex project

Discharge planning is almost as important as the treatment given to the patient. It can be difficult to put all the pieces of the discharge plan together; sometimes, unclear disposition is the only reason a patient is kept in the hospital after being stabilized.

Above all, our ability to work with the multidisciplinary team and our knowledge of these simple steps will help us navigate our patients’ care plan successfully.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility

Keep financing in mind

The patient’s ability to pay, as well as having access to insurance or a financial assistance program, is a major contributing factor in discharge planning. All financial options need to be considered by the physicians leading the discharge planning team.

Neither Medicaid nor Medicare benefits are available to pay rent; these insurance programs pay for medical services only. Medicaid does provide some money for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings (such assistance is arranged through, and provided by, home health care agencies) and to Medicaid-eligible residents of an assisted living facility.

Medicaid covers 100% of a nursing home stay for an eligible resident. Medicare might cover the cost of skilled-nursing facility care if the placement falls under the criterion of an “episode of care.”

It is worth mentioning that some Veterans’ Administration money might be available to a veteran or his (her) surviving spouse for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings or if he (she) is institutionalized. Other local programs might provide eligible recipients with long-term care services; discharge social workers, as members of the multidisciplinary team, usually are resourceful at identifying such programs.

All in all, a complex project

Discharge planning is almost as important as the treatment given to the patient. It can be difficult to put all the pieces of the discharge plan together; sometimes, unclear disposition is the only reason a patient is kept in the hospital after being stabilized.

Above all, our ability to work with the multidisciplinary team and our knowledge of these simple steps will help us navigate our patients’ care plan successfully.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Let me begin with a story.

A few years ago, when I was hoping to get into a psychiatry residency program, I did a month-long rotation in the intensive care unit (ICU) of a local hospital. One of our patients was a long-term resident of a nearby assisted living facility, who was treated for exacerbation of a chronic medical illness. Eventually this patient was stabilized to the point at which he could be discharged.

When the ICU physician decided to discharge this patient, he told the team that the man would need to be “sent back to a nursing home.” The social worker, assuming that the physician wanted to place the patient in a skilled nursing facility, spent several hours trying to place the man in one of the local facilities. When the patient’s daughter arrived to visit her father and began asking questions about why he was being placed in a nursing home, staff immediately realized that the physician had simply meant for him to go back “home”—that is, to the facility from which he had come and where he had been living for several years.

Being the only person in the ICU who was a licensed nursing home administrator, with more than 10 years experience in a long-term care, I should have pointed out this miscommunication or, at least, should have raised the question to clarify the physician’s intent. At the time, however, I wasn’t comfortable expressing my concern because I was “just an FMG observer” trying to stay on the attending’s good side.

I made a commitment to myself, however, to always talk about patients’ long-term care options and discharge planning algorithm with medical students, fellow residents, and other medical professionals I meet in my work. The following is an expression of that commitment.

Why focus on discharge when care is still underway?

Discharge planning usually begins on the first day of hospitalization. Before we are ready to discharge any patient, we, the physicians, usually have had many conversations with members of the multidisciplinary team and, always, with the patient and his (her) guardian(s). Why do we do all of this? The answer is simple: Physicians make the ultimate decision about what kind of environment (clinical, social, etc.) the patient is safe to be discharged to; after that decision is made, everything else is the patient’s choice. Our decision should be based on, first, global assessment of functioning—the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental (non-essential) ADL—and, second, essential input from members of multidisciplinary team.

Here is an example to illustrate this point: If we (the multidisciplinary team) believe that a patient who has lived alone and, up to this point, was able to handle his own affairs, will not be safe if he is discharged to his home (based on observation of his overall daily functioning) but he refuses to be institutionalized, we can evaluate his competency and initiate a motion to obtain a temporary guardianship.

If, on the other hand, we think that a patient needs to be placed in a skilled nursing facility and he, being fully aware of his condition, agrees with the decision of the multidisciplinary team, we cannot place him in a facility of our choosing (if it is against his will). Rather, we must give him options of facilities with similar services that meet his needs and let him or his guardian select the facility in which he’s to be placed.

How do we decide on the best course?

To choose what kind of environment a patient needs to be placed in after discharge, we can apply a simple algorithm (Box):

The patient does not need 24-hour protective oversight or needs some, but not 24-hour, care. Discharge him to a home-and community-based care setting—with arrangements for home health agency services or a home-modification program. The patient would either live independently or in a group home setting, depending on how much assistance he requires.

The patient does need 24-hour protective oversight and more than minimal assistance with ADL but doesn’t need 24-hour care, IV medication, etc.). In this case, the patient can be discharged to an assisted living or residential care facility, assuming that he is able to 1) find a so-called path to safety in an emergency (this why facilities are required to perform 1 fire drill per shift per month) and 2) afford rent, because Medicaid, Medicare, and many private insurance policies do not cover housing expenses (see “Keep financing in mind,” in the next section).

The patient is bed-bound or needs 24-hour treatment (eg, receives IV medication or needs total nursing care) or is not bed-bound but is unable to find a path to safety (eg, a person with dementia). This kind of patient must be placed in a skilled nursing facility

Keep financing in mind

The patient’s ability to pay, as well as having access to insurance or a financial assistance program, is a major contributing factor in discharge planning. All financial options need to be considered by the physicians leading the discharge planning team.

Neither Medicaid nor Medicare benefits are available to pay rent; these insurance programs pay for medical services only. Medicaid does provide some money for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings (such assistance is arranged through, and provided by, home health care agencies) and to Medicaid-eligible residents of an assisted living facility.

Medicaid covers 100% of a nursing home stay for an eligible resident. Medicare might cover the cost of skilled-nursing facility care if the placement falls under the criterion of an “episode of care.”

It is worth mentioning that some Veterans’ Administration money might be available to a veteran or his (her) surviving spouse for assistance with ADL in home- and community-based settings or if he (she) is institutionalized. Other local programs might provide eligible recipients with long-term care services; discharge social workers, as members of the multidisciplinary team, usually are resourceful at identifying such programs.

All in all, a complex project

Discharge planning is almost as important as the treatment given to the patient. It can be difficult to put all the pieces of the discharge plan together; sometimes, unclear disposition is the only reason a patient is kept in the hospital after being stabilized.

Above all, our ability to work with the multidisciplinary team and our knowledge of these simple steps will help us navigate our patients’ care plan successfully.

Disclosure

Dr. Graypel reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.