User login

Poll finds overwhelming support for Medicare coverage of end-of-life talks

The public overwhelmingly supports Medicare’s plan to pay for end-of-life discussions between doctors and patients, despite GOP objections that such chats would lead to rationed care for the elderly and ill, a poll released Sept. 30 finds.

About 8 of every 10 people surveyed by the Kaiser Family Foundation – in a nationally representative sample of 1,202 adults – supported coverage by the government or insurers for planning discussions about the type of care patients preferred in the waning days or weeks of their lives. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.) These discussions can include whether people would want to be kept alive by artificial means even if they had no chance of regaining consciousness or autonomy and whether they would want their organs to be donated. These preferences can be incorporated into advance directives, or living wills, which are used if someone can no longer communicate.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services earlier this year proposed paying doctors to have these talks with patients. A final decision is due out soon. The idea had been included in early drafts of the 2010 federal health care law, but former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin and other opponents of the law labeled the counseling sessions and other provisions “death panels” motivated by desires to save money, and the provision was deleted from the bill.

The notion of helping patients prepare for death has support among many doctors, who sometimes see terminal patients suffer from futile efforts to keep them alive. Last year, the Institute of Medicine issued a report that encouraged end-of-life discussions beginning as early as age 16.

The Kaiser poll found that these talks remain infrequent. Overall, only 17% of those surveyed said they had had such discussions with their doctors or other health care professionals, even though 89% believe doctors should engage in such counseling. A third of respondents said they had talked to doctors about another family member’s wishes for how they would want to be cared for at the end of life.

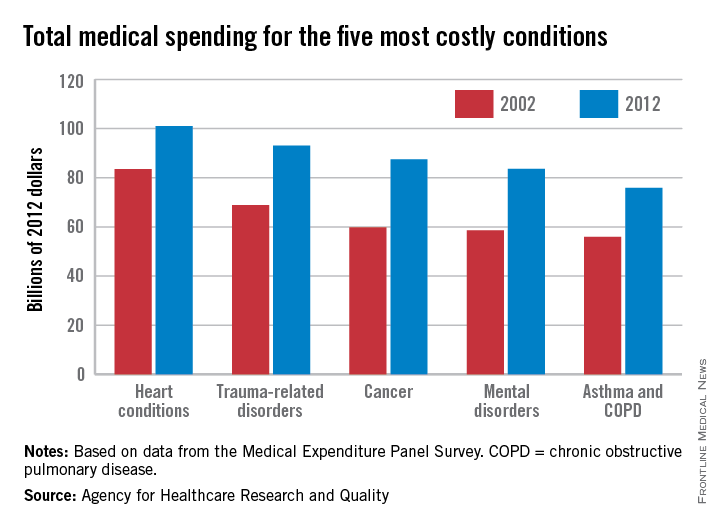

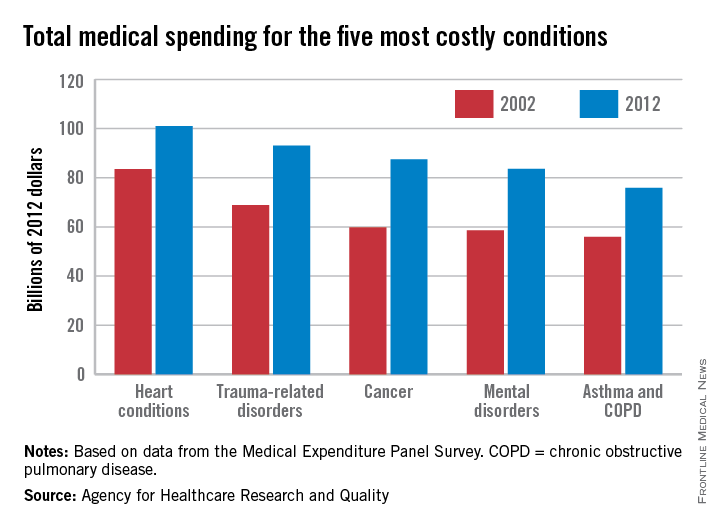

While none of these proposals calls for the cost of care to weigh on these discussions, the final years of life are indeed expensive for America’s health care system. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care has calculated that a third of Medicare spending goes to the care of people with chronic illnesses in their last 2 years of life. That is likely to increase as the population of those older than 65 increases. An analysis by the Kaiser foundation found that Medicare spending per person more than doubled from age 70 to 96, where it peaked at $16,145 per beneficiary in 2011.

The Kaiser poll found less public support for a cost-containment provision that did make it into the health law. The “Cadillac tax” begins in 2018 and will impose a tax on expensive insurance that employers provide to their workers. Sixty percent oppose the plan, which economists have long favored as a way to discourage lavish coverage and make people aware that extensive use of Medicare services is linked to premiums.

The poll also found that 57% of people favor repealing the medical device tax, another piece of the health law that Republicans in Congress are trying to repeal. The tax applies to artificial hips, pacemakers and other devices that doctors implant.

The poll was conducted from Sept. 17 through Sept. 23. The margin of error was +/– 3 percentage points.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

The public overwhelmingly supports Medicare’s plan to pay for end-of-life discussions between doctors and patients, despite GOP objections that such chats would lead to rationed care for the elderly and ill, a poll released Sept. 30 finds.

About 8 of every 10 people surveyed by the Kaiser Family Foundation – in a nationally representative sample of 1,202 adults – supported coverage by the government or insurers for planning discussions about the type of care patients preferred in the waning days or weeks of their lives. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.) These discussions can include whether people would want to be kept alive by artificial means even if they had no chance of regaining consciousness or autonomy and whether they would want their organs to be donated. These preferences can be incorporated into advance directives, or living wills, which are used if someone can no longer communicate.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services earlier this year proposed paying doctors to have these talks with patients. A final decision is due out soon. The idea had been included in early drafts of the 2010 federal health care law, but former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin and other opponents of the law labeled the counseling sessions and other provisions “death panels” motivated by desires to save money, and the provision was deleted from the bill.

The notion of helping patients prepare for death has support among many doctors, who sometimes see terminal patients suffer from futile efforts to keep them alive. Last year, the Institute of Medicine issued a report that encouraged end-of-life discussions beginning as early as age 16.

The Kaiser poll found that these talks remain infrequent. Overall, only 17% of those surveyed said they had had such discussions with their doctors or other health care professionals, even though 89% believe doctors should engage in such counseling. A third of respondents said they had talked to doctors about another family member’s wishes for how they would want to be cared for at the end of life.

While none of these proposals calls for the cost of care to weigh on these discussions, the final years of life are indeed expensive for America’s health care system. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care has calculated that a third of Medicare spending goes to the care of people with chronic illnesses in their last 2 years of life. That is likely to increase as the population of those older than 65 increases. An analysis by the Kaiser foundation found that Medicare spending per person more than doubled from age 70 to 96, where it peaked at $16,145 per beneficiary in 2011.

The Kaiser poll found less public support for a cost-containment provision that did make it into the health law. The “Cadillac tax” begins in 2018 and will impose a tax on expensive insurance that employers provide to their workers. Sixty percent oppose the plan, which economists have long favored as a way to discourage lavish coverage and make people aware that extensive use of Medicare services is linked to premiums.

The poll also found that 57% of people favor repealing the medical device tax, another piece of the health law that Republicans in Congress are trying to repeal. The tax applies to artificial hips, pacemakers and other devices that doctors implant.

The poll was conducted from Sept. 17 through Sept. 23. The margin of error was +/– 3 percentage points.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

The public overwhelmingly supports Medicare’s plan to pay for end-of-life discussions between doctors and patients, despite GOP objections that such chats would lead to rationed care for the elderly and ill, a poll released Sept. 30 finds.

About 8 of every 10 people surveyed by the Kaiser Family Foundation – in a nationally representative sample of 1,202 adults – supported coverage by the government or insurers for planning discussions about the type of care patients preferred in the waning days or weeks of their lives. (KHN is an editorially independent program of the foundation.) These discussions can include whether people would want to be kept alive by artificial means even if they had no chance of regaining consciousness or autonomy and whether they would want their organs to be donated. These preferences can be incorporated into advance directives, or living wills, which are used if someone can no longer communicate.

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services earlier this year proposed paying doctors to have these talks with patients. A final decision is due out soon. The idea had been included in early drafts of the 2010 federal health care law, but former Alaska Gov. Sarah Palin and other opponents of the law labeled the counseling sessions and other provisions “death panels” motivated by desires to save money, and the provision was deleted from the bill.

The notion of helping patients prepare for death has support among many doctors, who sometimes see terminal patients suffer from futile efforts to keep them alive. Last year, the Institute of Medicine issued a report that encouraged end-of-life discussions beginning as early as age 16.

The Kaiser poll found that these talks remain infrequent. Overall, only 17% of those surveyed said they had had such discussions with their doctors or other health care professionals, even though 89% believe doctors should engage in such counseling. A third of respondents said they had talked to doctors about another family member’s wishes for how they would want to be cared for at the end of life.

While none of these proposals calls for the cost of care to weigh on these discussions, the final years of life are indeed expensive for America’s health care system. The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care has calculated that a third of Medicare spending goes to the care of people with chronic illnesses in their last 2 years of life. That is likely to increase as the population of those older than 65 increases. An analysis by the Kaiser foundation found that Medicare spending per person more than doubled from age 70 to 96, where it peaked at $16,145 per beneficiary in 2011.

The Kaiser poll found less public support for a cost-containment provision that did make it into the health law. The “Cadillac tax” begins in 2018 and will impose a tax on expensive insurance that employers provide to their workers. Sixty percent oppose the plan, which economists have long favored as a way to discourage lavish coverage and make people aware that extensive use of Medicare services is linked to premiums.

The poll also found that 57% of people favor repealing the medical device tax, another piece of the health law that Republicans in Congress are trying to repeal. The tax applies to artificial hips, pacemakers and other devices that doctors implant.

The poll was conducted from Sept. 17 through Sept. 23. The margin of error was +/– 3 percentage points.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service that is part of the nonpartisan Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

Physicians face telemedicine payment challenges

Emergency department personnel at a remote hospital called Dr. James P. Marcin regarding a baby who was just admitted with an upper respiratory infection. Because the patient had cyanotic congenital heart disease, the team was concerned she was too medically complex for their facility, and they were preparing to helicopter her to the pediatric intensive care unit at the University of California, Davis, Children’s Hospital in Sacramento.

But when Dr. Marcin examined the baby via a two-way video, he remembered the child from a previous visit. Although her oxygen levels were low, Dr. Marcin knew they were normal for her condition. Dr. Marcin spoke with the patient’s parents and after learning more about the patient’s symptoms, he was confident the child could remain at the small hospital. She was treated for the upper respiratory infection and later sent home where she improved, said Dr. Marcin, who leads the Pediatric Telemedicine Program at UC Davis.

Despite the positive outcome, Dr. Marcin’s claim was denied by the insurance company, he said.

“Had I not used telemedicine, that child would have been put in a helicopter, flown to our ICU, [and likely incurred] some $20,000 bill,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “I saved the insurance company $20,000, and then they ended up denying my 2 hours of critical care time. It’s discouraging.”

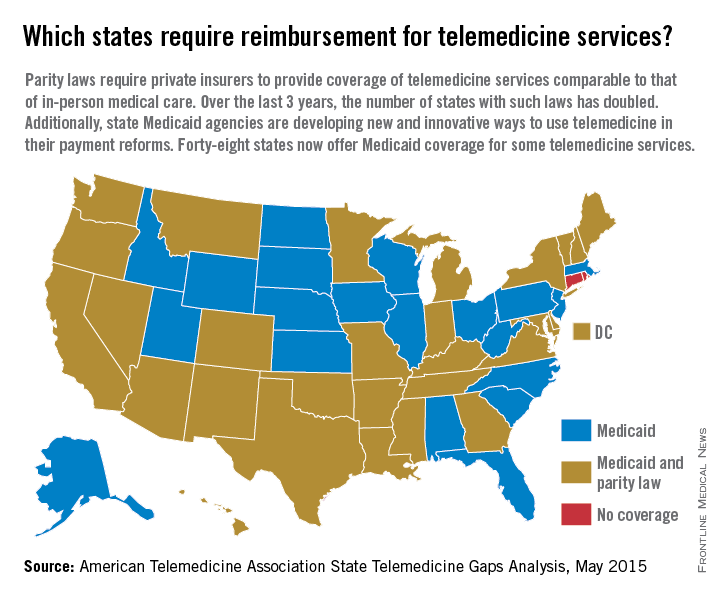

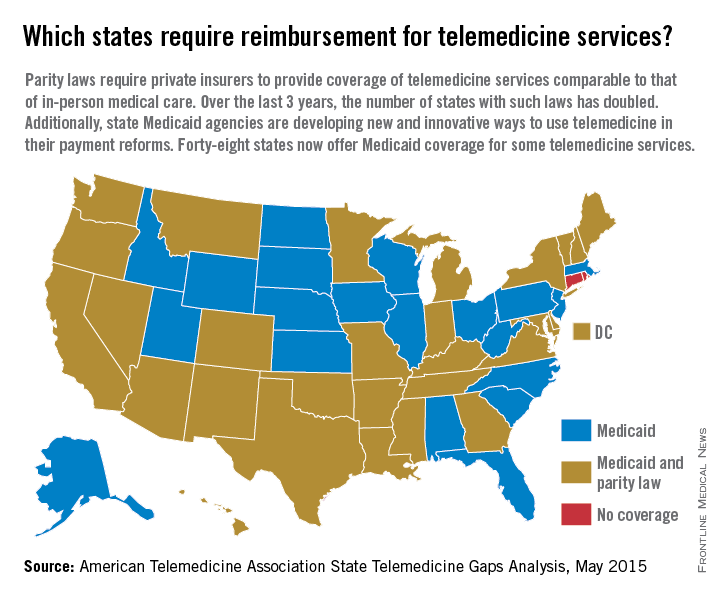

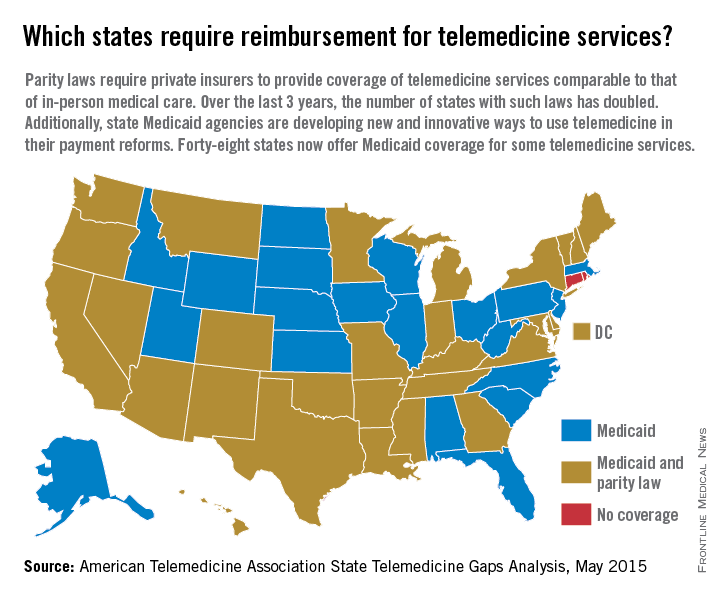

Reimbursement struggles are playing out in medical practices and hospitals across the country. While insurance coverage for telemedicine is growing, experts say payment remains one of the most pressing challenges. So far, 29 states and the District of Columbia have laws that require full parity of coverage and reimbursement for telemedicine services comparable to that of in-person services, according to the American Telemedicine Association (ATA). Medicaid programs in almost all (48) states require some form of compensation for telemedicine, according to a 2015 ATA report.

Payment parity for telemedicine has doubled in the last 2 years, noted Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, ATA president.

“We are seeing, on the side of the private insurance world, really exciting acceptance of telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said in an interview. There has been “really great movement forward.”

Enforcement of those parity laws can be spotty, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney.

“It’s a mixed bag,” Mr. Quashie said in an interview. “In some states, enforcement is lax so you still have a lot of providers submitting claims that are not being paid or not being paid timely.”

State support equals payment success

In rural Wrightsville, Ga., Dr. Jean R. Sumner regularly gets paid to provide telemedicine. Georgia enacted its parity law in 2006 and has greatly embraced telemedicine capabilities, particularly for its rural populations, said Dr. Sumner, associate dean for rural health at Mercer University in Macon. Part of the success is because of the Georgia Partnership for TeleHealth, a statewide network that focuses on increasing access to care through telemedicine. Its hallmark is the state’s open access network, a web of access points based on existing telemedicine programs that enables secure health information exchange. The goal of the program is for all rural Georgians to access specialty care within 30 miles of their homes.

The state’s strong support of telemedicine contributes to payers taking the modality seriously and doctors getting paid for telemedicine care, Dr. Sumner said in an interview.

“Most insurers pay as long as the visit is equal or superior to an exam done in person,” she said. “It has to be quality care.”

Dr. Sumner also can bill a site fee when telemedicine technology is used at her practice, she said. If a patient visits her practice for a psychiatric consultation while Dr. Sumner is busy, for example, a nurse can connect the patient to a psychiatrist through the office’s telemedicine unit. The site fee is minimal, but it helps cover costs, she said.

In states that do not have parity laws, some larger health plans, such as Anthem and UnitedHealthcare, have proactively covered telemedicine services, said Dr. Peter Antall, president and medical director of American Well’s Online Care Group, a national telehealth service. Smaller health plans on the other hand, are sometimes willing to negotiate with providers and consider adding telemedicine services to a fee schedule, Dr. Antall said in an interview.

“I think we’re moving into a phase where reimbursement is normal or expected in telehealth,” he said. “We’re not quite there yet because there are so many health plans and, within the health plans, there are so many different products and subgroups. It’s still a process that needs to evolve.”

Government payers lag behind

Medicaid policies also vary from state by state. Some state programs cover telemedicine services similar to that of in-person treatment. Others limit coverage by technology or geographic area.

Medicare, by far, ranks the worst in paying physicians for telemedicine, experts said. Of $597 billion in total Medicare payments in 2014, 0.0023% was spent on telemedicine, according to data provided to the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law.

“Unless you’re a patient that presents in a rural community, the Medicare telehealth benefit is not available,” said Mr. Quashie, who is part of the CTeL’s legal resource team. “Medicare is almost a no-go under fee-for-service for telehealth.”

CMS reimburses physicians for telemedicine only when the originating site is in a Health Professional Shortage Area or within a county outside a Metropolitan Statistical Area. The originating site must be a medical facility and not the patient’s home. CMS covers care only on an approved list of medical services.

In its 2016 proposed fee schedule, CMS recommended adding two new codes to its accepted telemedicine services, including codes for prolonged service inpatient care and end-stage renal disease–related services. However, the agency denied a handful of other services requested by the ATA and again, refused to end its patient site limitations.

“We are very concerned about Medicare’s decisions in terms of its ability and willingness to reimburse” telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said. “Physicians who are trying to care for our nation’s seniors – so many of whom are presenting real challenges in manging their care in an optimal way – those physicians and patients deserve the opportunity to use [telehealth] tools, and physicians deserve to be reimbursed for the appropriate use of those tools.”

Federal legislation to expand Medicare coverage for telehealth has previously failed. Most recently, Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) proposed H.R. 2948, the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act of 2015, a bill that would broaden Medicare telemedicine coverage to urban areas and cover more services. The bill has been referred to the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health.

Coverage of telemedicine by all payers is especially necessary as the health care system shifts to a more value-based care structure, Dr. Marcin said. Telemedicine presents great opportunities for preventing illnesses, keeping patients out of the hospital, and lowering health costs, he said. However, financial incentives to utilize telemedicine in these ways is lacking.

“Even though these technologies have been proven to reduce overall health care costs, they result in lower payments to doctors and hospitals,” Dr. Marcin said. “There’s a malalignment with payments to both hospitals and doctors and what should be the goals of health care, which is to keep patients healthy.”

Coming Tuesday, Oct. 6: Can telemedicine expose you to legal risk?

On Twitter @legal_med

Emergency department personnel at a remote hospital called Dr. James P. Marcin regarding a baby who was just admitted with an upper respiratory infection. Because the patient had cyanotic congenital heart disease, the team was concerned she was too medically complex for their facility, and they were preparing to helicopter her to the pediatric intensive care unit at the University of California, Davis, Children’s Hospital in Sacramento.

But when Dr. Marcin examined the baby via a two-way video, he remembered the child from a previous visit. Although her oxygen levels were low, Dr. Marcin knew they were normal for her condition. Dr. Marcin spoke with the patient’s parents and after learning more about the patient’s symptoms, he was confident the child could remain at the small hospital. She was treated for the upper respiratory infection and later sent home where she improved, said Dr. Marcin, who leads the Pediatric Telemedicine Program at UC Davis.

Despite the positive outcome, Dr. Marcin’s claim was denied by the insurance company, he said.

“Had I not used telemedicine, that child would have been put in a helicopter, flown to our ICU, [and likely incurred] some $20,000 bill,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “I saved the insurance company $20,000, and then they ended up denying my 2 hours of critical care time. It’s discouraging.”

Reimbursement struggles are playing out in medical practices and hospitals across the country. While insurance coverage for telemedicine is growing, experts say payment remains one of the most pressing challenges. So far, 29 states and the District of Columbia have laws that require full parity of coverage and reimbursement for telemedicine services comparable to that of in-person services, according to the American Telemedicine Association (ATA). Medicaid programs in almost all (48) states require some form of compensation for telemedicine, according to a 2015 ATA report.

Payment parity for telemedicine has doubled in the last 2 years, noted Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, ATA president.

“We are seeing, on the side of the private insurance world, really exciting acceptance of telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said in an interview. There has been “really great movement forward.”

Enforcement of those parity laws can be spotty, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney.

“It’s a mixed bag,” Mr. Quashie said in an interview. “In some states, enforcement is lax so you still have a lot of providers submitting claims that are not being paid or not being paid timely.”

State support equals payment success

In rural Wrightsville, Ga., Dr. Jean R. Sumner regularly gets paid to provide telemedicine. Georgia enacted its parity law in 2006 and has greatly embraced telemedicine capabilities, particularly for its rural populations, said Dr. Sumner, associate dean for rural health at Mercer University in Macon. Part of the success is because of the Georgia Partnership for TeleHealth, a statewide network that focuses on increasing access to care through telemedicine. Its hallmark is the state’s open access network, a web of access points based on existing telemedicine programs that enables secure health information exchange. The goal of the program is for all rural Georgians to access specialty care within 30 miles of their homes.

The state’s strong support of telemedicine contributes to payers taking the modality seriously and doctors getting paid for telemedicine care, Dr. Sumner said in an interview.

“Most insurers pay as long as the visit is equal or superior to an exam done in person,” she said. “It has to be quality care.”

Dr. Sumner also can bill a site fee when telemedicine technology is used at her practice, she said. If a patient visits her practice for a psychiatric consultation while Dr. Sumner is busy, for example, a nurse can connect the patient to a psychiatrist through the office’s telemedicine unit. The site fee is minimal, but it helps cover costs, she said.

In states that do not have parity laws, some larger health plans, such as Anthem and UnitedHealthcare, have proactively covered telemedicine services, said Dr. Peter Antall, president and medical director of American Well’s Online Care Group, a national telehealth service. Smaller health plans on the other hand, are sometimes willing to negotiate with providers and consider adding telemedicine services to a fee schedule, Dr. Antall said in an interview.

“I think we’re moving into a phase where reimbursement is normal or expected in telehealth,” he said. “We’re not quite there yet because there are so many health plans and, within the health plans, there are so many different products and subgroups. It’s still a process that needs to evolve.”

Government payers lag behind

Medicaid policies also vary from state by state. Some state programs cover telemedicine services similar to that of in-person treatment. Others limit coverage by technology or geographic area.

Medicare, by far, ranks the worst in paying physicians for telemedicine, experts said. Of $597 billion in total Medicare payments in 2014, 0.0023% was spent on telemedicine, according to data provided to the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law.

“Unless you’re a patient that presents in a rural community, the Medicare telehealth benefit is not available,” said Mr. Quashie, who is part of the CTeL’s legal resource team. “Medicare is almost a no-go under fee-for-service for telehealth.”

CMS reimburses physicians for telemedicine only when the originating site is in a Health Professional Shortage Area or within a county outside a Metropolitan Statistical Area. The originating site must be a medical facility and not the patient’s home. CMS covers care only on an approved list of medical services.

In its 2016 proposed fee schedule, CMS recommended adding two new codes to its accepted telemedicine services, including codes for prolonged service inpatient care and end-stage renal disease–related services. However, the agency denied a handful of other services requested by the ATA and again, refused to end its patient site limitations.

“We are very concerned about Medicare’s decisions in terms of its ability and willingness to reimburse” telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said. “Physicians who are trying to care for our nation’s seniors – so many of whom are presenting real challenges in manging their care in an optimal way – those physicians and patients deserve the opportunity to use [telehealth] tools, and physicians deserve to be reimbursed for the appropriate use of those tools.”

Federal legislation to expand Medicare coverage for telehealth has previously failed. Most recently, Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) proposed H.R. 2948, the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act of 2015, a bill that would broaden Medicare telemedicine coverage to urban areas and cover more services. The bill has been referred to the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health.

Coverage of telemedicine by all payers is especially necessary as the health care system shifts to a more value-based care structure, Dr. Marcin said. Telemedicine presents great opportunities for preventing illnesses, keeping patients out of the hospital, and lowering health costs, he said. However, financial incentives to utilize telemedicine in these ways is lacking.

“Even though these technologies have been proven to reduce overall health care costs, they result in lower payments to doctors and hospitals,” Dr. Marcin said. “There’s a malalignment with payments to both hospitals and doctors and what should be the goals of health care, which is to keep patients healthy.”

Coming Tuesday, Oct. 6: Can telemedicine expose you to legal risk?

On Twitter @legal_med

Emergency department personnel at a remote hospital called Dr. James P. Marcin regarding a baby who was just admitted with an upper respiratory infection. Because the patient had cyanotic congenital heart disease, the team was concerned she was too medically complex for their facility, and they were preparing to helicopter her to the pediatric intensive care unit at the University of California, Davis, Children’s Hospital in Sacramento.

But when Dr. Marcin examined the baby via a two-way video, he remembered the child from a previous visit. Although her oxygen levels were low, Dr. Marcin knew they were normal for her condition. Dr. Marcin spoke with the patient’s parents and after learning more about the patient’s symptoms, he was confident the child could remain at the small hospital. She was treated for the upper respiratory infection and later sent home where she improved, said Dr. Marcin, who leads the Pediatric Telemedicine Program at UC Davis.

Despite the positive outcome, Dr. Marcin’s claim was denied by the insurance company, he said.

“Had I not used telemedicine, that child would have been put in a helicopter, flown to our ICU, [and likely incurred] some $20,000 bill,” Dr. Marcin said in an interview. “I saved the insurance company $20,000, and then they ended up denying my 2 hours of critical care time. It’s discouraging.”

Reimbursement struggles are playing out in medical practices and hospitals across the country. While insurance coverage for telemedicine is growing, experts say payment remains one of the most pressing challenges. So far, 29 states and the District of Columbia have laws that require full parity of coverage and reimbursement for telemedicine services comparable to that of in-person services, according to the American Telemedicine Association (ATA). Medicaid programs in almost all (48) states require some form of compensation for telemedicine, according to a 2015 ATA report.

Payment parity for telemedicine has doubled in the last 2 years, noted Dr. Reed V. Tuckson, ATA president.

“We are seeing, on the side of the private insurance world, really exciting acceptance of telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said in an interview. There has been “really great movement forward.”

Enforcement of those parity laws can be spotty, said René Y. Quashie, a Washington health law attorney.

“It’s a mixed bag,” Mr. Quashie said in an interview. “In some states, enforcement is lax so you still have a lot of providers submitting claims that are not being paid or not being paid timely.”

State support equals payment success

In rural Wrightsville, Ga., Dr. Jean R. Sumner regularly gets paid to provide telemedicine. Georgia enacted its parity law in 2006 and has greatly embraced telemedicine capabilities, particularly for its rural populations, said Dr. Sumner, associate dean for rural health at Mercer University in Macon. Part of the success is because of the Georgia Partnership for TeleHealth, a statewide network that focuses on increasing access to care through telemedicine. Its hallmark is the state’s open access network, a web of access points based on existing telemedicine programs that enables secure health information exchange. The goal of the program is for all rural Georgians to access specialty care within 30 miles of their homes.

The state’s strong support of telemedicine contributes to payers taking the modality seriously and doctors getting paid for telemedicine care, Dr. Sumner said in an interview.

“Most insurers pay as long as the visit is equal or superior to an exam done in person,” she said. “It has to be quality care.”

Dr. Sumner also can bill a site fee when telemedicine technology is used at her practice, she said. If a patient visits her practice for a psychiatric consultation while Dr. Sumner is busy, for example, a nurse can connect the patient to a psychiatrist through the office’s telemedicine unit. The site fee is minimal, but it helps cover costs, she said.

In states that do not have parity laws, some larger health plans, such as Anthem and UnitedHealthcare, have proactively covered telemedicine services, said Dr. Peter Antall, president and medical director of American Well’s Online Care Group, a national telehealth service. Smaller health plans on the other hand, are sometimes willing to negotiate with providers and consider adding telemedicine services to a fee schedule, Dr. Antall said in an interview.

“I think we’re moving into a phase where reimbursement is normal or expected in telehealth,” he said. “We’re not quite there yet because there are so many health plans and, within the health plans, there are so many different products and subgroups. It’s still a process that needs to evolve.”

Government payers lag behind

Medicaid policies also vary from state by state. Some state programs cover telemedicine services similar to that of in-person treatment. Others limit coverage by technology or geographic area.

Medicare, by far, ranks the worst in paying physicians for telemedicine, experts said. Of $597 billion in total Medicare payments in 2014, 0.0023% was spent on telemedicine, according to data provided to the Robert J. Waters Center for Telehealth & e-Health Law.

“Unless you’re a patient that presents in a rural community, the Medicare telehealth benefit is not available,” said Mr. Quashie, who is part of the CTeL’s legal resource team. “Medicare is almost a no-go under fee-for-service for telehealth.”

CMS reimburses physicians for telemedicine only when the originating site is in a Health Professional Shortage Area or within a county outside a Metropolitan Statistical Area. The originating site must be a medical facility and not the patient’s home. CMS covers care only on an approved list of medical services.

In its 2016 proposed fee schedule, CMS recommended adding two new codes to its accepted telemedicine services, including codes for prolonged service inpatient care and end-stage renal disease–related services. However, the agency denied a handful of other services requested by the ATA and again, refused to end its patient site limitations.

“We are very concerned about Medicare’s decisions in terms of its ability and willingness to reimburse” telehealth services,” Dr. Tuckson said. “Physicians who are trying to care for our nation’s seniors – so many of whom are presenting real challenges in manging their care in an optimal way – those physicians and patients deserve the opportunity to use [telehealth] tools, and physicians deserve to be reimbursed for the appropriate use of those tools.”

Federal legislation to expand Medicare coverage for telehealth has previously failed. Most recently, Rep. Mike Thompson (D-Calif.) proposed H.R. 2948, the Medicare Telehealth Parity Act of 2015, a bill that would broaden Medicare telemedicine coverage to urban areas and cover more services. The bill has been referred to the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Health.

Coverage of telemedicine by all payers is especially necessary as the health care system shifts to a more value-based care structure, Dr. Marcin said. Telemedicine presents great opportunities for preventing illnesses, keeping patients out of the hospital, and lowering health costs, he said. However, financial incentives to utilize telemedicine in these ways is lacking.

“Even though these technologies have been proven to reduce overall health care costs, they result in lower payments to doctors and hospitals,” Dr. Marcin said. “There’s a malalignment with payments to both hospitals and doctors and what should be the goals of health care, which is to keep patients healthy.”

Coming Tuesday, Oct. 6: Can telemedicine expose you to legal risk?

On Twitter @legal_med

ICD-10: Feds tout resources available for Oct. 1 switch

Officials from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought to assure physicians that the agency is on track for a smooth transition to ICD-10 on Oct. 1.

“We have proven that our claims processing center will be able to accept claims without any problems, and [the claims] will be paid,” Dr. William Rogers, ICD-10 ombudsman at CMS, said in a press conference Sept. 24.

Dr. Patrick H. Conway, CMS principal deputy administrator, added that real-time monitoring of the switch will take place so that the agency can “investigate and address issues as they come in through the ICD-10 coordination center.”

Dr. Rogers and Dr. Conway outlined a number of resources available to assist with the transition:

• General information is available is available at the Road to ICD-10 and www.cms.gov/ICD10.

• Should a problem or concern arise, turn first to your billing vendor or clearinghouse.

• Next, reach out to your Medicare administrative contractor (MAC).

• Questions and concerns can be emailed to the ICD-10 Coordination Center at icd10@cms.hhs.gov.

• If there are still issues, email the ICD-10 ombudsman’s office at icd10_ombudsbman@cms.hhs.gov.Both Dr. Rogers and Dr. Conway downplayed concerns about whether stalled congressional budget negotiations, potentially leading to a government shutdown, would have any impact on the ICD-10 transition. They emphasized that patients will receive the same services on Oct. 1, when ICD-10 officially kicks off, as they did the day before.

Data on claims processing under ICD-10 will be available after one full billing cycle is complete, which should be about 30 days, Dr. Conway said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Officials from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought to assure physicians that the agency is on track for a smooth transition to ICD-10 on Oct. 1.

“We have proven that our claims processing center will be able to accept claims without any problems, and [the claims] will be paid,” Dr. William Rogers, ICD-10 ombudsman at CMS, said in a press conference Sept. 24.

Dr. Patrick H. Conway, CMS principal deputy administrator, added that real-time monitoring of the switch will take place so that the agency can “investigate and address issues as they come in through the ICD-10 coordination center.”

Dr. Rogers and Dr. Conway outlined a number of resources available to assist with the transition:

• General information is available is available at the Road to ICD-10 and www.cms.gov/ICD10.

• Should a problem or concern arise, turn first to your billing vendor or clearinghouse.

• Next, reach out to your Medicare administrative contractor (MAC).

• Questions and concerns can be emailed to the ICD-10 Coordination Center at icd10@cms.hhs.gov.

• If there are still issues, email the ICD-10 ombudsman’s office at icd10_ombudsbman@cms.hhs.gov.Both Dr. Rogers and Dr. Conway downplayed concerns about whether stalled congressional budget negotiations, potentially leading to a government shutdown, would have any impact on the ICD-10 transition. They emphasized that patients will receive the same services on Oct. 1, when ICD-10 officially kicks off, as they did the day before.

Data on claims processing under ICD-10 will be available after one full billing cycle is complete, which should be about 30 days, Dr. Conway said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

Officials from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services sought to assure physicians that the agency is on track for a smooth transition to ICD-10 on Oct. 1.

“We have proven that our claims processing center will be able to accept claims without any problems, and [the claims] will be paid,” Dr. William Rogers, ICD-10 ombudsman at CMS, said in a press conference Sept. 24.

Dr. Patrick H. Conway, CMS principal deputy administrator, added that real-time monitoring of the switch will take place so that the agency can “investigate and address issues as they come in through the ICD-10 coordination center.”

Dr. Rogers and Dr. Conway outlined a number of resources available to assist with the transition:

• General information is available is available at the Road to ICD-10 and www.cms.gov/ICD10.

• Should a problem or concern arise, turn first to your billing vendor or clearinghouse.

• Next, reach out to your Medicare administrative contractor (MAC).

• Questions and concerns can be emailed to the ICD-10 Coordination Center at icd10@cms.hhs.gov.

• If there are still issues, email the ICD-10 ombudsman’s office at icd10_ombudsbman@cms.hhs.gov.Both Dr. Rogers and Dr. Conway downplayed concerns about whether stalled congressional budget negotiations, potentially leading to a government shutdown, would have any impact on the ICD-10 transition. They emphasized that patients will receive the same services on Oct. 1, when ICD-10 officially kicks off, as they did the day before.

Data on claims processing under ICD-10 will be available after one full billing cycle is complete, which should be about 30 days, Dr. Conway said.

On Twitter @whitneymcknight

More expanded drug indications approved on less rigorous evidence

Hundreds of new – but noninnovative – drugs have been approved in the United States in the last 20 years using expedited review programs designed especially to push forward first-in-class agents for unmet medical needs.

An extensive review of publicly available Food and Drug Administration records also concluded that few of these drugs rely on the more rigorous clinical trials intended to screen out ineffectively or potentially harmful drugs – potentially increasing the availability of poorly investigated agents that may or may not provide much clinical benefit*.

“These data have important implications for patient care,” Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim and his colleagues wrote (BMJ 2015;351:h4679 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4679).

“Special regulatory designations allow drugs to be approved at earlier stages based on less rigorous clinical testing; for example, one review showed drugs with orphan designations or granted accelerated approval are also more likely than drugs without these designations to be tested in single-arm studies without placebo or active comparators,” said Dr. Kesselheim of Harvard University and his coinvestigators. “While many physicians and patients trust that FDA-approved products are effective and safe for use, products approved on the basis of more limited data are at greater risk for later changes to their effectiveness or safety profiles.”

A twin study, published in the same issue, found that a lesser class of evidence often supports the approval of supplemental indications. Of 295 supplemental indications approved since 2005, only about one-third were based on trials with active comparators. The rest used nonclinical endpoints like historical controls and biomarkers or imaging data.

Most striking of all, most of the supplemental indications were aimed at pediatric patients, and many extrapolated adult evidence to these young patients, said the authors.

“Although we do not conclude that any of these approvals were mistaken, pediatric patients have unique physiologies and pharmacokinetic characteristics that may require more rigorous trials to confirm both the efficacy and the safety of drugs previously approved only for use in adults.”

Study 1: Expedited review

The authors used the Drugs@FDA database, FDA annual reports, and the Federal Register to identify 774 new agents representing first-in-class agents. Overall, this accounted for a significant increase of 2.6% per year in the number of expedited review and approval programs for each new agent (rate ratio, 1.06) and a 2.4% increase per year in the proportion of agents involved in at least one of these programs. Many approvals were associated with more than one program, and this proportion increased over the study period, from a low of 0.54 in 1987 to a high of 1.72 in 2014.

“Driving this trend was an increase in the proportion of approved, non–first-in-class drugs,” associated with at least one [expedited] program,” the authors noted.

Additionally, not all of the drugs could reasonably be considered as treatments for an urgent, unmet medical need. “For example, bimatoprost (Latisse: Allergan, Dublin) was granted priority review when it was first approved in 2008 for hypotrichosis of the eyelids, a clearly less serious condition.”

While the “breakthrough therapy” pathway was intended for only a handful of drug approvals each year, the FDA received nearly 250 applications in the first 2 years; 68 of these were granted, despite the agency’s prediction than only 2-4 such applications would be approved.

Four of these were for chronic lymphocytic anemia alone – a number the authors suggested might be excessive. “It is doubtful that a single disease condition can be the subject of four true ‘breakthroughs’ in such a short time frame.”

The situation is likely to accelerate, they noted. The 21st Century Cures Act, passed in July by the U.S. House of Representatives, instructs the FDA to develop a new pathway for repurposing approved drugs on the basis of early stage investigators and “high-risk, high-reward research. ... The FDA would also be permitted to approve such indications on the basis of only summaries of data in such circumstances, rather than being required to review the data in detail.”

New antibiotics and antifungals would have particularly lenient evidence requirements, according to the investigators.

However, expedited review is a double-edged sword, the paper noted. An FDA review found that most cancer drugs are later found to be safe and effective in postapproval studies, although such studies are often delayed or – in some cases – never conducted.

The FDA should be granted more authority to punish manufacturers who lag behind these requirements, including having the ability to impose fines and even suspend approval until additional studies are complete, the investigators said.

Study 2: Approval evidence for supplemental indications

The second study concluded that the FDA increasingly approves supplemental indications with less than level I evidence (randomized, controlled trials with placebo or active comparator (BMJ. 2015;351:h4679. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4679).

Of an examined 295 such approvals since 2005, the largest portion was for oncology (27%). Other indications were infectious disease (15%); cardiovascular disease and prevention (12%); psychiatry (12%); musculoskeletal and rheumatology (10%); neurology (8%); gastroenterology (6%); and other (1%). Orphan drug status accounted for 20% of the approvals.

Only 30% of modified indications were supported by efficacy trials with active comparators. Level I evidence supported half of modified use approvals and 11% of approvals expanding the patient population. Almost all of the expansion approvals were into pediatric populations, and the vast majority (94%) of evidence for those was extrapolated from adult clinical trials.

Uncontrolled trials supported 34% of expanded population approvals, and nine (14%) of these supplemental approvals had no trials with clinical endpoints.

Findings were similar with other approval pathways. Among new indications, 32% had clinical endpoints, as did 30% of modified indications. Only 22% of expanded population indications rested on clinical endpoint data.

“Clinical outcomes were most often used in trials supporting supplemental indication approvals of neurologic (48%) and infectious disease drugs (45%); by contrast, 70% of oncology supplemental indications were supported exclusively by trials using surrogate outcomes.”

Uncontrolled trials supported one-third of expanded population supplements; 14% of these had no clinical trial evidence. Similarly, one-third of orphan drug indications were supported by uncontrolled or historical cohort studies. Significantly fewer orphan than nonorphan approvals were supported by clinical trials (18% vs. 35%).

Again, the situation is likely to accelerate. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act provides up to 6 months of additional market exclusivity for a new approval, “which can be extremely lucrative for the sponsor,” the authors noted. The 21st Century Cures Act will also play into the situation, they said.

“The high degree of heterogeneity of supporting evidence for supplemental indications, in the setting of legislation promoting drug approvals based on decreasing evidentiary standards, underscores the need for a robust system of postapproval drug monitoring for efficacy and safety, timely confirmatory studies, and reexamination of existing legislative incentives to promote the optimal delivery of evidence-based medicine.”

Both studies were supported in part by the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program in bioethics and the Harvard program in therapeutic science. Dr. Kesselheim and his coinvestigators had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

*Correction, 9/24/2015: An earlier version of this article misstated the review's findings.

The FDA provides too many expanded drug indications with too little supporting research.

Independent examinations of the agency’s records, including the two studies by Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim and colleagues, are finding that up to 90% of these approvals provide few or no advantages for patients. The FDA’s flexible criteria and low threshold for approval do not reward more research for breakthroughs but instead reward more research for minor variations that can clear this low threshold.

Patients and doctors have clamored for expedited approval pathways that allow clinical access to new drugs sooner – a process that also generates revenue for drug companies to fund more breakthrough research. But faster approval means taking less time to prove these drugs safe and effective for their new indications. And in an age when prescription drugs are the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and the third-leading cause in Europe, according to some reports, this doesn’t seem to be a wise move.

Expedited trials – and approvals based on nonclinical data – are incapable of providing patients or doctors with valid information on what new clinical benefits a drug provides.

Patients and doctors must trust the FDA to live up to its claims of providing drugs that work not only for their approved indications, but help more than they harm. But its expedited approval processes only require, in most cases, that the drugs provide “nonzero” levels of effectiveness.

The United States and other countries need an alternative paradigm – one in which research focuses on better medicines for patients rather than for profits, where clinical trials with low risk of bias look for real benefits and faithfully report harms.

Dr. Donald W. Light, an osteopathic physician at Rowan University, Cherry Hill, N.J., and Dr. Joel Lexchin of the School of Health Policy and Management at York University in Toronto made these comments in an accompanying editorial (BMJ 2015;351:h4897). They had no disclosures.

The FDA provides too many expanded drug indications with too little supporting research.

Independent examinations of the agency’s records, including the two studies by Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim and colleagues, are finding that up to 90% of these approvals provide few or no advantages for patients. The FDA’s flexible criteria and low threshold for approval do not reward more research for breakthroughs but instead reward more research for minor variations that can clear this low threshold.

Patients and doctors have clamored for expedited approval pathways that allow clinical access to new drugs sooner – a process that also generates revenue for drug companies to fund more breakthrough research. But faster approval means taking less time to prove these drugs safe and effective for their new indications. And in an age when prescription drugs are the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and the third-leading cause in Europe, according to some reports, this doesn’t seem to be a wise move.

Expedited trials – and approvals based on nonclinical data – are incapable of providing patients or doctors with valid information on what new clinical benefits a drug provides.

Patients and doctors must trust the FDA to live up to its claims of providing drugs that work not only for their approved indications, but help more than they harm. But its expedited approval processes only require, in most cases, that the drugs provide “nonzero” levels of effectiveness.

The United States and other countries need an alternative paradigm – one in which research focuses on better medicines for patients rather than for profits, where clinical trials with low risk of bias look for real benefits and faithfully report harms.

Dr. Donald W. Light, an osteopathic physician at Rowan University, Cherry Hill, N.J., and Dr. Joel Lexchin of the School of Health Policy and Management at York University in Toronto made these comments in an accompanying editorial (BMJ 2015;351:h4897). They had no disclosures.

The FDA provides too many expanded drug indications with too little supporting research.

Independent examinations of the agency’s records, including the two studies by Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim and colleagues, are finding that up to 90% of these approvals provide few or no advantages for patients. The FDA’s flexible criteria and low threshold for approval do not reward more research for breakthroughs but instead reward more research for minor variations that can clear this low threshold.

Patients and doctors have clamored for expedited approval pathways that allow clinical access to new drugs sooner – a process that also generates revenue for drug companies to fund more breakthrough research. But faster approval means taking less time to prove these drugs safe and effective for their new indications. And in an age when prescription drugs are the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States and the third-leading cause in Europe, according to some reports, this doesn’t seem to be a wise move.

Expedited trials – and approvals based on nonclinical data – are incapable of providing patients or doctors with valid information on what new clinical benefits a drug provides.

Patients and doctors must trust the FDA to live up to its claims of providing drugs that work not only for their approved indications, but help more than they harm. But its expedited approval processes only require, in most cases, that the drugs provide “nonzero” levels of effectiveness.

The United States and other countries need an alternative paradigm – one in which research focuses on better medicines for patients rather than for profits, where clinical trials with low risk of bias look for real benefits and faithfully report harms.

Dr. Donald W. Light, an osteopathic physician at Rowan University, Cherry Hill, N.J., and Dr. Joel Lexchin of the School of Health Policy and Management at York University in Toronto made these comments in an accompanying editorial (BMJ 2015;351:h4897). They had no disclosures.

Hundreds of new – but noninnovative – drugs have been approved in the United States in the last 20 years using expedited review programs designed especially to push forward first-in-class agents for unmet medical needs.

An extensive review of publicly available Food and Drug Administration records also concluded that few of these drugs rely on the more rigorous clinical trials intended to screen out ineffectively or potentially harmful drugs – potentially increasing the availability of poorly investigated agents that may or may not provide much clinical benefit*.

“These data have important implications for patient care,” Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim and his colleagues wrote (BMJ 2015;351:h4679 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4679).

“Special regulatory designations allow drugs to be approved at earlier stages based on less rigorous clinical testing; for example, one review showed drugs with orphan designations or granted accelerated approval are also more likely than drugs without these designations to be tested in single-arm studies without placebo or active comparators,” said Dr. Kesselheim of Harvard University and his coinvestigators. “While many physicians and patients trust that FDA-approved products are effective and safe for use, products approved on the basis of more limited data are at greater risk for later changes to their effectiveness or safety profiles.”

A twin study, published in the same issue, found that a lesser class of evidence often supports the approval of supplemental indications. Of 295 supplemental indications approved since 2005, only about one-third were based on trials with active comparators. The rest used nonclinical endpoints like historical controls and biomarkers or imaging data.

Most striking of all, most of the supplemental indications were aimed at pediatric patients, and many extrapolated adult evidence to these young patients, said the authors.

“Although we do not conclude that any of these approvals were mistaken, pediatric patients have unique physiologies and pharmacokinetic characteristics that may require more rigorous trials to confirm both the efficacy and the safety of drugs previously approved only for use in adults.”

Study 1: Expedited review

The authors used the Drugs@FDA database, FDA annual reports, and the Federal Register to identify 774 new agents representing first-in-class agents. Overall, this accounted for a significant increase of 2.6% per year in the number of expedited review and approval programs for each new agent (rate ratio, 1.06) and a 2.4% increase per year in the proportion of agents involved in at least one of these programs. Many approvals were associated with more than one program, and this proportion increased over the study period, from a low of 0.54 in 1987 to a high of 1.72 in 2014.

“Driving this trend was an increase in the proportion of approved, non–first-in-class drugs,” associated with at least one [expedited] program,” the authors noted.

Additionally, not all of the drugs could reasonably be considered as treatments for an urgent, unmet medical need. “For example, bimatoprost (Latisse: Allergan, Dublin) was granted priority review when it was first approved in 2008 for hypotrichosis of the eyelids, a clearly less serious condition.”

While the “breakthrough therapy” pathway was intended for only a handful of drug approvals each year, the FDA received nearly 250 applications in the first 2 years; 68 of these were granted, despite the agency’s prediction than only 2-4 such applications would be approved.

Four of these were for chronic lymphocytic anemia alone – a number the authors suggested might be excessive. “It is doubtful that a single disease condition can be the subject of four true ‘breakthroughs’ in such a short time frame.”

The situation is likely to accelerate, they noted. The 21st Century Cures Act, passed in July by the U.S. House of Representatives, instructs the FDA to develop a new pathway for repurposing approved drugs on the basis of early stage investigators and “high-risk, high-reward research. ... The FDA would also be permitted to approve such indications on the basis of only summaries of data in such circumstances, rather than being required to review the data in detail.”

New antibiotics and antifungals would have particularly lenient evidence requirements, according to the investigators.

However, expedited review is a double-edged sword, the paper noted. An FDA review found that most cancer drugs are later found to be safe and effective in postapproval studies, although such studies are often delayed or – in some cases – never conducted.

The FDA should be granted more authority to punish manufacturers who lag behind these requirements, including having the ability to impose fines and even suspend approval until additional studies are complete, the investigators said.

Study 2: Approval evidence for supplemental indications

The second study concluded that the FDA increasingly approves supplemental indications with less than level I evidence (randomized, controlled trials with placebo or active comparator (BMJ. 2015;351:h4679. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4679).

Of an examined 295 such approvals since 2005, the largest portion was for oncology (27%). Other indications were infectious disease (15%); cardiovascular disease and prevention (12%); psychiatry (12%); musculoskeletal and rheumatology (10%); neurology (8%); gastroenterology (6%); and other (1%). Orphan drug status accounted for 20% of the approvals.

Only 30% of modified indications were supported by efficacy trials with active comparators. Level I evidence supported half of modified use approvals and 11% of approvals expanding the patient population. Almost all of the expansion approvals were into pediatric populations, and the vast majority (94%) of evidence for those was extrapolated from adult clinical trials.

Uncontrolled trials supported 34% of expanded population approvals, and nine (14%) of these supplemental approvals had no trials with clinical endpoints.

Findings were similar with other approval pathways. Among new indications, 32% had clinical endpoints, as did 30% of modified indications. Only 22% of expanded population indications rested on clinical endpoint data.

“Clinical outcomes were most often used in trials supporting supplemental indication approvals of neurologic (48%) and infectious disease drugs (45%); by contrast, 70% of oncology supplemental indications were supported exclusively by trials using surrogate outcomes.”

Uncontrolled trials supported one-third of expanded population supplements; 14% of these had no clinical trial evidence. Similarly, one-third of orphan drug indications were supported by uncontrolled or historical cohort studies. Significantly fewer orphan than nonorphan approvals were supported by clinical trials (18% vs. 35%).

Again, the situation is likely to accelerate. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act provides up to 6 months of additional market exclusivity for a new approval, “which can be extremely lucrative for the sponsor,” the authors noted. The 21st Century Cures Act will also play into the situation, they said.

“The high degree of heterogeneity of supporting evidence for supplemental indications, in the setting of legislation promoting drug approvals based on decreasing evidentiary standards, underscores the need for a robust system of postapproval drug monitoring for efficacy and safety, timely confirmatory studies, and reexamination of existing legislative incentives to promote the optimal delivery of evidence-based medicine.”

Both studies were supported in part by the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program in bioethics and the Harvard program in therapeutic science. Dr. Kesselheim and his coinvestigators had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

*Correction, 9/24/2015: An earlier version of this article misstated the review's findings.

Hundreds of new – but noninnovative – drugs have been approved in the United States in the last 20 years using expedited review programs designed especially to push forward first-in-class agents for unmet medical needs.

An extensive review of publicly available Food and Drug Administration records also concluded that few of these drugs rely on the more rigorous clinical trials intended to screen out ineffectively or potentially harmful drugs – potentially increasing the availability of poorly investigated agents that may or may not provide much clinical benefit*.

“These data have important implications for patient care,” Dr. Aaron S. Kesselheim and his colleagues wrote (BMJ 2015;351:h4679 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4679).

“Special regulatory designations allow drugs to be approved at earlier stages based on less rigorous clinical testing; for example, one review showed drugs with orphan designations or granted accelerated approval are also more likely than drugs without these designations to be tested in single-arm studies without placebo or active comparators,” said Dr. Kesselheim of Harvard University and his coinvestigators. “While many physicians and patients trust that FDA-approved products are effective and safe for use, products approved on the basis of more limited data are at greater risk for later changes to their effectiveness or safety profiles.”

A twin study, published in the same issue, found that a lesser class of evidence often supports the approval of supplemental indications. Of 295 supplemental indications approved since 2005, only about one-third were based on trials with active comparators. The rest used nonclinical endpoints like historical controls and biomarkers or imaging data.

Most striking of all, most of the supplemental indications were aimed at pediatric patients, and many extrapolated adult evidence to these young patients, said the authors.

“Although we do not conclude that any of these approvals were mistaken, pediatric patients have unique physiologies and pharmacokinetic characteristics that may require more rigorous trials to confirm both the efficacy and the safety of drugs previously approved only for use in adults.”

Study 1: Expedited review

The authors used the Drugs@FDA database, FDA annual reports, and the Federal Register to identify 774 new agents representing first-in-class agents. Overall, this accounted for a significant increase of 2.6% per year in the number of expedited review and approval programs for each new agent (rate ratio, 1.06) and a 2.4% increase per year in the proportion of agents involved in at least one of these programs. Many approvals were associated with more than one program, and this proportion increased over the study period, from a low of 0.54 in 1987 to a high of 1.72 in 2014.

“Driving this trend was an increase in the proportion of approved, non–first-in-class drugs,” associated with at least one [expedited] program,” the authors noted.

Additionally, not all of the drugs could reasonably be considered as treatments for an urgent, unmet medical need. “For example, bimatoprost (Latisse: Allergan, Dublin) was granted priority review when it was first approved in 2008 for hypotrichosis of the eyelids, a clearly less serious condition.”

While the “breakthrough therapy” pathway was intended for only a handful of drug approvals each year, the FDA received nearly 250 applications in the first 2 years; 68 of these were granted, despite the agency’s prediction than only 2-4 such applications would be approved.

Four of these were for chronic lymphocytic anemia alone – a number the authors suggested might be excessive. “It is doubtful that a single disease condition can be the subject of four true ‘breakthroughs’ in such a short time frame.”

The situation is likely to accelerate, they noted. The 21st Century Cures Act, passed in July by the U.S. House of Representatives, instructs the FDA to develop a new pathway for repurposing approved drugs on the basis of early stage investigators and “high-risk, high-reward research. ... The FDA would also be permitted to approve such indications on the basis of only summaries of data in such circumstances, rather than being required to review the data in detail.”

New antibiotics and antifungals would have particularly lenient evidence requirements, according to the investigators.

However, expedited review is a double-edged sword, the paper noted. An FDA review found that most cancer drugs are later found to be safe and effective in postapproval studies, although such studies are often delayed or – in some cases – never conducted.

The FDA should be granted more authority to punish manufacturers who lag behind these requirements, including having the ability to impose fines and even suspend approval until additional studies are complete, the investigators said.

Study 2: Approval evidence for supplemental indications

The second study concluded that the FDA increasingly approves supplemental indications with less than level I evidence (randomized, controlled trials with placebo or active comparator (BMJ. 2015;351:h4679. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h4679).

Of an examined 295 such approvals since 2005, the largest portion was for oncology (27%). Other indications were infectious disease (15%); cardiovascular disease and prevention (12%); psychiatry (12%); musculoskeletal and rheumatology (10%); neurology (8%); gastroenterology (6%); and other (1%). Orphan drug status accounted for 20% of the approvals.

Only 30% of modified indications were supported by efficacy trials with active comparators. Level I evidence supported half of modified use approvals and 11% of approvals expanding the patient population. Almost all of the expansion approvals were into pediatric populations, and the vast majority (94%) of evidence for those was extrapolated from adult clinical trials.

Uncontrolled trials supported 34% of expanded population approvals, and nine (14%) of these supplemental approvals had no trials with clinical endpoints.

Findings were similar with other approval pathways. Among new indications, 32% had clinical endpoints, as did 30% of modified indications. Only 22% of expanded population indications rested on clinical endpoint data.

“Clinical outcomes were most often used in trials supporting supplemental indication approvals of neurologic (48%) and infectious disease drugs (45%); by contrast, 70% of oncology supplemental indications were supported exclusively by trials using surrogate outcomes.”

Uncontrolled trials supported one-third of expanded population supplements; 14% of these had no clinical trial evidence. Similarly, one-third of orphan drug indications were supported by uncontrolled or historical cohort studies. Significantly fewer orphan than nonorphan approvals were supported by clinical trials (18% vs. 35%).

Again, the situation is likely to accelerate. The Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act provides up to 6 months of additional market exclusivity for a new approval, “which can be extremely lucrative for the sponsor,” the authors noted. The 21st Century Cures Act will also play into the situation, they said.

“The high degree of heterogeneity of supporting evidence for supplemental indications, in the setting of legislation promoting drug approvals based on decreasing evidentiary standards, underscores the need for a robust system of postapproval drug monitoring for efficacy and safety, timely confirmatory studies, and reexamination of existing legislative incentives to promote the optimal delivery of evidence-based medicine.”

Both studies were supported in part by the Greenwall Faculty Scholars Program in bioethics and the Harvard program in therapeutic science. Dr. Kesselheim and his coinvestigators had no financial disclosures.

On Twitter @alz_gal

*Correction, 9/24/2015: An earlier version of this article misstated the review's findings.

FROM BMJ

IOM report: Teamwork key to reducing medical diagnostic errors

WASHINGTON – Almost every American will experience a medical diagnostic error, but the problem has taken a back seat to other patient safety concerns, an influential panel said in a report out Sept. 22 calling for widespread changes.

Diagnostic errors – defined as inaccurate or delayed diagnoses – account for an estimated 10% of patient deaths, hundreds of thousands of adverse events in hospitals each year, and are a leading cause of paid medical malpractice claims, a blue ribbon panel of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) said in its report.

Such errors can occur with very rare conditions, such as the Liberian man with undetected Ebola who was sent home from a Dallas hospital last September; or more common problems, such as acid reflux being mistaken for a heart attack or a pathology report showing cancer that is never communicated to a patient.

Still, reducing the number won’t be easy, in part because there is no standard, required way to track such errors. Reversing current trends, the report concludes, will require better medical teamwork, training, and computer systems.

“Some people go to their graves with a diagnostic error that is never detected,” said Robert A. Berenson, a research fellow at the Urban Institute in Washington and one of the committee members who wrote the report. “It’s much more difficult to measure than a medication error.”

The report, called “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care,” is the latest in a series launched 15 years ago with “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” which fueled the patient-safety movement with its estimate that as many as 98,000 patients die each year because of medical errors. The IOM is part of the private, nonprofit National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

Tuesday’s report has a role for just about everyone in the health system, from computer programmers to clinicians to patients. It recommends better teamwork among health care providers, patients, and families. Citing the dearth of data about diagnostic errors, the report calls for voluntary efforts to report such problems. Dedicated funding is needed for research, the report says, and hospitals and doctors need to develop better ways to identify, reduce, and learn from “near misses.”

Ironically, the report notes that computerized health records, which can help track and coordinate care, can also become a barrier to efficient and correct diagnoses.

The systems, it says, often aren’t compatible from one physician’s office to another or among hospitals, “auto-fill” functions sometimes result in the wrong information being entered, and the sheer volume of inputs and alerts can overwhelm medical staff.

It cites a study of emergency department staff that found clinicians spent more time inputting information into computers than taking care of patients. Another study found that while electronic health record systems provide alerts in response to abnormal diagnostic test results, 70% of medical staff surveyed said they receive more alerts than they can manage.

Making the systems more efficient and allowing patients more timely access to their own medical records to check for and correct errors “could be a game changer,” said Berenson.

Indeed, patients “are going to be critical to the solution,” said Dr. Michael Cohen, another report author and a professor of pathology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “There’s a real opportunity for patients to advocate for themselves and at the same time to challenge the health care providers about the diagnosis being made.”

Helen Haskell, who formed Mothers Against Medical Error after her 15-year-old son died as the result of a medical error, said she was pleased the report focused on better teamwork and communication. She also said patients need better access to their records – particularly hospital records – and said consumers should always ask questions.

“What else can it be? Does this diagnosis match all my symptoms?,” are two of the best questions to ask, said Haskell. “If there is any question, people should get a second opinion.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service that is part of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

WASHINGTON – Almost every American will experience a medical diagnostic error, but the problem has taken a back seat to other patient safety concerns, an influential panel said in a report out Sept. 22 calling for widespread changes.

Diagnostic errors – defined as inaccurate or delayed diagnoses – account for an estimated 10% of patient deaths, hundreds of thousands of adverse events in hospitals each year, and are a leading cause of paid medical malpractice claims, a blue ribbon panel of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) said in its report.

Such errors can occur with very rare conditions, such as the Liberian man with undetected Ebola who was sent home from a Dallas hospital last September; or more common problems, such as acid reflux being mistaken for a heart attack or a pathology report showing cancer that is never communicated to a patient.

Still, reducing the number won’t be easy, in part because there is no standard, required way to track such errors. Reversing current trends, the report concludes, will require better medical teamwork, training, and computer systems.

“Some people go to their graves with a diagnostic error that is never detected,” said Robert A. Berenson, a research fellow at the Urban Institute in Washington and one of the committee members who wrote the report. “It’s much more difficult to measure than a medication error.”

The report, called “Improving Diagnosis in Health Care,” is the latest in a series launched 15 years ago with “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,” which fueled the patient-safety movement with its estimate that as many as 98,000 patients die each year because of medical errors. The IOM is part of the private, nonprofit National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

Tuesday’s report has a role for just about everyone in the health system, from computer programmers to clinicians to patients. It recommends better teamwork among health care providers, patients, and families. Citing the dearth of data about diagnostic errors, the report calls for voluntary efforts to report such problems. Dedicated funding is needed for research, the report says, and hospitals and doctors need to develop better ways to identify, reduce, and learn from “near misses.”

Ironically, the report notes that computerized health records, which can help track and coordinate care, can also become a barrier to efficient and correct diagnoses.

The systems, it says, often aren’t compatible from one physician’s office to another or among hospitals, “auto-fill” functions sometimes result in the wrong information being entered, and the sheer volume of inputs and alerts can overwhelm medical staff.

It cites a study of emergency department staff that found clinicians spent more time inputting information into computers than taking care of patients. Another study found that while electronic health record systems provide alerts in response to abnormal diagnostic test results, 70% of medical staff surveyed said they receive more alerts than they can manage.

Making the systems more efficient and allowing patients more timely access to their own medical records to check for and correct errors “could be a game changer,” said Berenson.

Indeed, patients “are going to be critical to the solution,” said Dr. Michael Cohen, another report author and a professor of pathology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. “There’s a real opportunity for patients to advocate for themselves and at the same time to challenge the health care providers about the diagnosis being made.”

Helen Haskell, who formed Mothers Against Medical Error after her 15-year-old son died as the result of a medical error, said she was pleased the report focused on better teamwork and communication. She also said patients need better access to their records – particularly hospital records – and said consumers should always ask questions.

“What else can it be? Does this diagnosis match all my symptoms?,” are two of the best questions to ask, said Haskell. “If there is any question, people should get a second opinion.”

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit national health policy news service that is part of the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation.

WASHINGTON – Almost every American will experience a medical diagnostic error, but the problem has taken a back seat to other patient safety concerns, an influential panel said in a report out Sept. 22 calling for widespread changes.

Diagnostic errors – defined as inaccurate or delayed diagnoses – account for an estimated 10% of patient deaths, hundreds of thousands of adverse events in hospitals each year, and are a leading cause of paid medical malpractice claims, a blue ribbon panel of the Institute of Medicine (IOM) said in its report.

Such errors can occur with very rare conditions, such as the Liberian man with undetected Ebola who was sent home from a Dallas hospital last September; or more common problems, such as acid reflux being mistaken for a heart attack or a pathology report showing cancer that is never communicated to a patient.

Still, reducing the number won’t be easy, in part because there is no standard, required way to track such errors. Reversing current trends, the report concludes, will require better medical teamwork, training, and computer systems.