User login

Child of The New Gastroenterologist

An Unusual Cause of Recurrent Severe Abdominal Colic

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

We carefully reviewed the patient’s history and found that he had been using jineijin, a traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) drug, which is made with dried endothelium corneum gigeriae galli (Figure E), at about 500 g/month and squama mantis (a TCM drug, at less than 5 g/month) as dietary supplements for 3 years.

Acknowledgments

We thank Linshen Xie, MD, department of environmental health and occupational diseases, No. 4 West China Teaching Hospital, Sichuan University, for offering some clinical data. We thank the patient for giving permission to share his information.

References

1. National Research Council (US). Safe Drinking Water Committee. Drinking water and health. National Academy Press. Washington, D.C. 1977;1:309.

2. State Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine. Advanced Textbook on Traditional Chinese Medicine and Pharmacology. New World Press, Beijing. 1995. (vol. 2).

3. Hui Hu, Q.J., Kavan, P. A study of heavy metal pollution in China: Current status, pollution-control policies and countermeasures. Sustainability. 2014;6:5820-38.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit, Learning objective: Upon completion of this examination, successful learners will be able to identify the features of lead poisoning.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151:819-21)

Dr. Deng, Dr. Hu, and Dr. Zhang are in the department of gastroenterology, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Sichuan Province, China.

A Rare Endoscopic Clue to a Common Clinical Condition

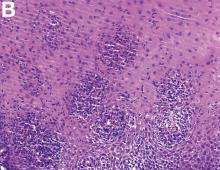

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

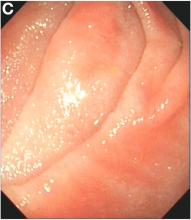

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

The correct answer is C: colonic ischemia.

References

1. Zuckerman G.R., et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2018-22.

2. Tanapanpanit O., Pongpirul K. BMJ Case Rep. 2015 Sept. 17;2015.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see gastrojournal.org for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this activity, successful learners will be able to recognize colon single-stripe sign as an endoscopic feature of colonic ischemia.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2017;152:492-3)

Dr. Anderson and Dr. Sweetser are in the Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn.

An 87-Year-Old Woman With Recurrent Dysphagia

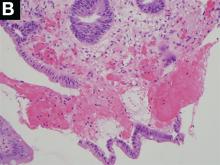

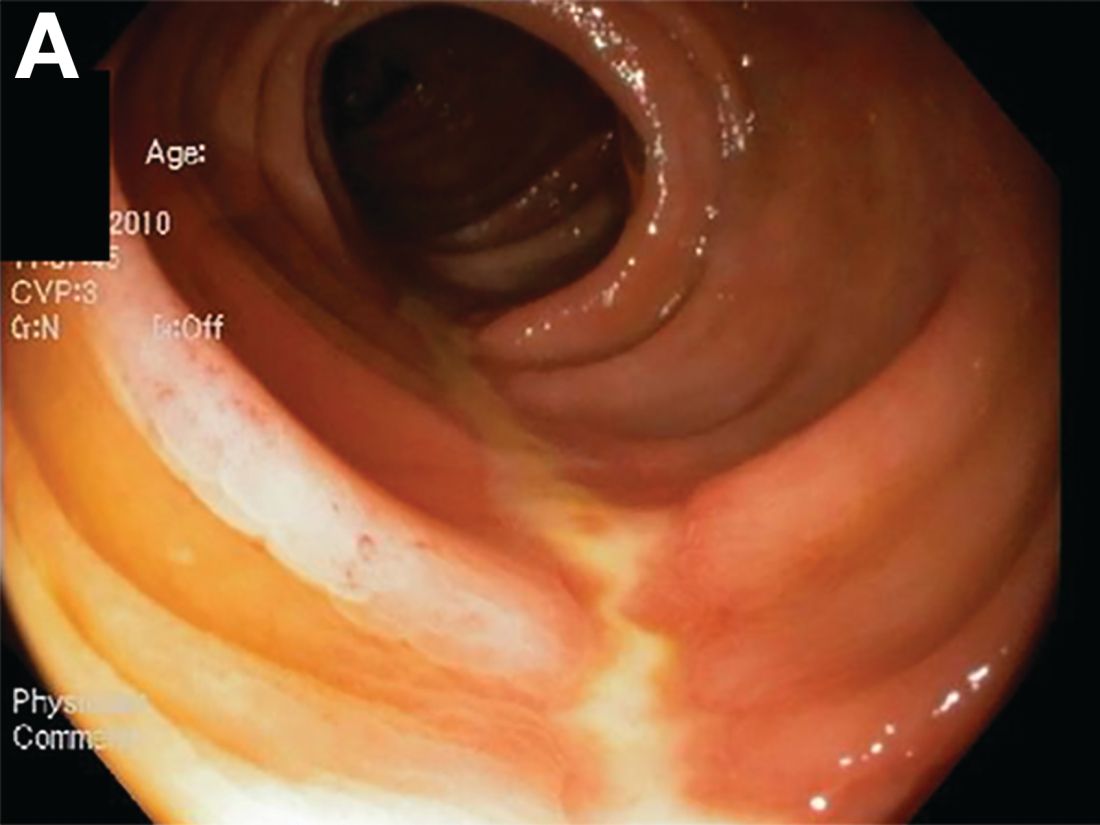

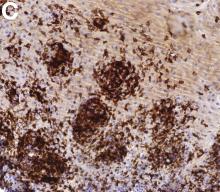

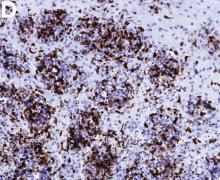

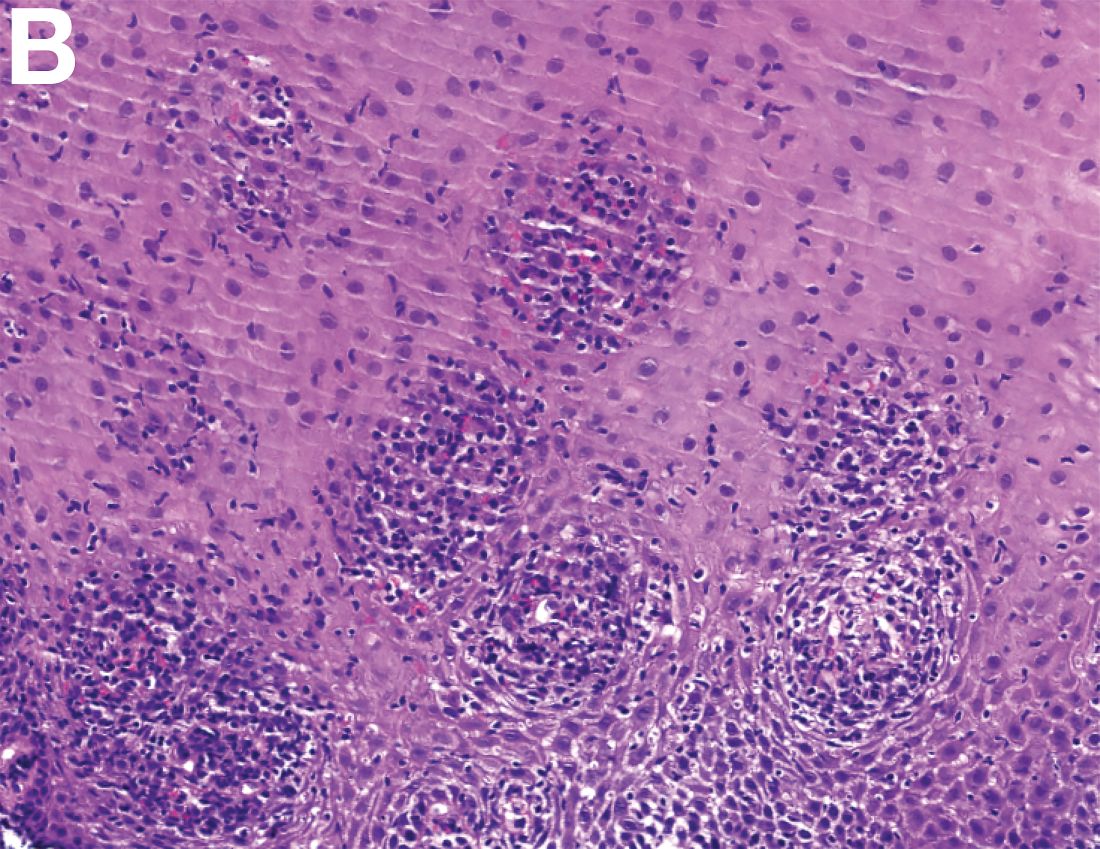

The correct answer is C: lymphocytic esophagitis.

References

1. Rubio, C.A., Sjodahl, K., Lagergren, J. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A histologic subset of chronic esophagitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:432-7.

2. Cohen, S., Saxena, A., Waljee, A.K., et al. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A diagnosis of increasing frequency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:828-32.

3. Haque, S., Genta, R.M. Lymphocytic oesophagitis: Clinicopathological aspects of an emerging condition. Gut. 2012;61:1108-14.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see Gastroenterology website for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this teaching case and questions, the learners will be able to identify one typical clinical and endoscopic presentation of the entity lymphocytic esophagitis, distinguish its histological pattern from other esophageal disorders and recognize a variety of other clinical presentations of this condition.

The correct answer is C: lymphocytic esophagitis.

References

1. Rubio, C.A., Sjodahl, K., Lagergren, J. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A histologic subset of chronic esophagitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:432-7.

2. Cohen, S., Saxena, A., Waljee, A.K., et al. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A diagnosis of increasing frequency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:828-32.

3. Haque, S., Genta, R.M. Lymphocytic oesophagitis: Clinicopathological aspects of an emerging condition. Gut. 2012;61:1108-14.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see Gastroenterology website for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this teaching case and questions, the learners will be able to identify one typical clinical and endoscopic presentation of the entity lymphocytic esophagitis, distinguish its histological pattern from other esophageal disorders and recognize a variety of other clinical presentations of this condition.

The correct answer is C: lymphocytic esophagitis.

References

1. Rubio, C.A., Sjodahl, K., Lagergren, J. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A histologic subset of chronic esophagitis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2006;125:432-7.

2. Cohen, S., Saxena, A., Waljee, A.K., et al. Lymphocytic esophagitis: A diagnosis of increasing frequency. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:828-32.

3. Haque, S., Genta, R.M. Lymphocytic oesophagitis: Clinicopathological aspects of an emerging condition. Gut. 2012;61:1108-14.

This article has an accompanying continuing medical education activity, also eligible for MOC credit (see Gastroenterology website for details). Learning Objective: Upon completion of this teaching case and questions, the learners will be able to identify one typical clinical and endoscopic presentation of the entity lymphocytic esophagitis, distinguish its histological pattern from other esophageal disorders and recognize a variety of other clinical presentations of this condition.

Previously Published in Gastroenterology (2016;151:1085-6)

An 87-year-old woman was referred due to dysphagia that had been present for several years. Three years prior to this presentation she had undergone an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) on the same indication showing a proximal and a distal esophageal benign-appearing stricture but no signs of esophagitis. Both were dilated and biopsied. Histopathology showed infiltration with lymphocytes and neutrophilic granulocytes, and superficially fungal hyphae and spores. No predominance of eosinophilic granulocytes was noted. A proton-pump inhibitor was prescribed and she was scheduled for a control gastroscopy, but was lost to follow-up. She was otherwise healthy without any allergies.

Upon re-presentation, she was under treatment with pantoprazole 40 mg OD. Upon EGD a spiral-shaped proximal esophageal stricture with normal-appearing mucosa only passable with a nasal endoscope was observed. The rest of the esophagus was seen with mucosal concentric rings (Figure A; video). The esophageal mucosa was otherwise endoscopically normal throughout. Biopsies were taken from the distal and proximal esophagus. Balloon dilation of the proximal stricture was performed (CRE, Boston Scientific) to 13.5 mm (video). Subsequently, a standard gastroscope could be passed to the duodenum revealing normal-appearing gastric and duodenal mucosa.

Dr. Havre and Dr. Kalaitzakis are in the Endoscopy Unit of Copenhagen University Hospital/Herlev, University of Copenhagen. Ms. Hallager is in the department of pathology, Copenhagen University Hospital/Herlev. The authors disclose no conflicts.

Unraveling a patient’s post-op symptoms

The correct answer is B: endoscopic suture removal. As the prevalence of bariatric surgery increases to address the obesity epidemic, endoscopists are increasingly called upon to evaluate postbariatric patients.1 In one case series of patients undergoing EGD for upper GI symptoms post-RYGB, normal postsurgical anatomy was found in 31.6%, anastomotic stricture in 52.6%, marginal ulcer in 15.8%, unraveled suture material causing functional obstruction in 4% and gastro-gastric fistula in 2.6% of cases.2 Another series reported unraveled suture material thought to be contributing to upper GI symptoms in up to 10% of cases.3 Suture material is found by a mean of 34 weeks after RYGB, and presenting symptoms include abdominal pain in 65%, nausea 52%, dysphagia 22%, and melena in 13%. Unraveled suture material may be associated with marginal ulceration, or may cause obstruction as it presents a mechanical obstruction to foodstuff as it passes through the gastrojejunal anastomosis. A series of 29 therapeutic endoscopic suture removal cases reported resolution or improvement of symptoms in 83% of patients and no complications or anastomotic leaks.3

While symptomatic management with antiemetics and analgesics (answer A) is important in managing this patient, it will not lead to definitive management of her underlying condition. The patient may require laparosopic surgical revision (answer C) if her symptoms persist after endoscopic suture removal, but it is premature to recommend this. An upper GI series (answer D) would be helpful in diagnosing a gastro-gastric fistula in this patient population, but the endoscopic evaluation suggests suture material leading to food bolus impaction and gut irritation is the cause of her symptoms. Finally, while the patient’s symptoms of intermittent obstruction raises concerns for gastrojejunal stenosis, the endoscopic exam showed a normal-caliber stoma. Thus, stomal dilation (answer E) is incorrect.

References

1. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans J.A., Muthusamy V.R., et al. The role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;8:1063-72.

2. Lee J.K., Van Dam J., Morton J.M., et al. Endoscopy is accurate, safe, and effective in the assessment and management of complications following gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:575-82.

3. Yu S., Jastrow K., Clapp B., et al. Foreign material erosion after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: findings and treatment. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1216-20.

The correct answer is B: endoscopic suture removal. As the prevalence of bariatric surgery increases to address the obesity epidemic, endoscopists are increasingly called upon to evaluate postbariatric patients.1 In one case series of patients undergoing EGD for upper GI symptoms post-RYGB, normal postsurgical anatomy was found in 31.6%, anastomotic stricture in 52.6%, marginal ulcer in 15.8%, unraveled suture material causing functional obstruction in 4% and gastro-gastric fistula in 2.6% of cases.2 Another series reported unraveled suture material thought to be contributing to upper GI symptoms in up to 10% of cases.3 Suture material is found by a mean of 34 weeks after RYGB, and presenting symptoms include abdominal pain in 65%, nausea 52%, dysphagia 22%, and melena in 13%. Unraveled suture material may be associated with marginal ulceration, or may cause obstruction as it presents a mechanical obstruction to foodstuff as it passes through the gastrojejunal anastomosis. A series of 29 therapeutic endoscopic suture removal cases reported resolution or improvement of symptoms in 83% of patients and no complications or anastomotic leaks.3

While symptomatic management with antiemetics and analgesics (answer A) is important in managing this patient, it will not lead to definitive management of her underlying condition. The patient may require laparosopic surgical revision (answer C) if her symptoms persist after endoscopic suture removal, but it is premature to recommend this. An upper GI series (answer D) would be helpful in diagnosing a gastro-gastric fistula in this patient population, but the endoscopic evaluation suggests suture material leading to food bolus impaction and gut irritation is the cause of her symptoms. Finally, while the patient’s symptoms of intermittent obstruction raises concerns for gastrojejunal stenosis, the endoscopic exam showed a normal-caliber stoma. Thus, stomal dilation (answer E) is incorrect.

References

1. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans J.A., Muthusamy V.R., et al. The role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;8:1063-72.

2. Lee J.K., Van Dam J., Morton J.M., et al. Endoscopy is accurate, safe, and effective in the assessment and management of complications following gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:575-82.

3. Yu S., Jastrow K., Clapp B., et al. Foreign material erosion after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: findings and treatment. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1216-20.

The correct answer is B: endoscopic suture removal. As the prevalence of bariatric surgery increases to address the obesity epidemic, endoscopists are increasingly called upon to evaluate postbariatric patients.1 In one case series of patients undergoing EGD for upper GI symptoms post-RYGB, normal postsurgical anatomy was found in 31.6%, anastomotic stricture in 52.6%, marginal ulcer in 15.8%, unraveled suture material causing functional obstruction in 4% and gastro-gastric fistula in 2.6% of cases.2 Another series reported unraveled suture material thought to be contributing to upper GI symptoms in up to 10% of cases.3 Suture material is found by a mean of 34 weeks after RYGB, and presenting symptoms include abdominal pain in 65%, nausea 52%, dysphagia 22%, and melena in 13%. Unraveled suture material may be associated with marginal ulceration, or may cause obstruction as it presents a mechanical obstruction to foodstuff as it passes through the gastrojejunal anastomosis. A series of 29 therapeutic endoscopic suture removal cases reported resolution or improvement of symptoms in 83% of patients and no complications or anastomotic leaks.3

While symptomatic management with antiemetics and analgesics (answer A) is important in managing this patient, it will not lead to definitive management of her underlying condition. The patient may require laparosopic surgical revision (answer C) if her symptoms persist after endoscopic suture removal, but it is premature to recommend this. An upper GI series (answer D) would be helpful in diagnosing a gastro-gastric fistula in this patient population, but the endoscopic evaluation suggests suture material leading to food bolus impaction and gut irritation is the cause of her symptoms. Finally, while the patient’s symptoms of intermittent obstruction raises concerns for gastrojejunal stenosis, the endoscopic exam showed a normal-caliber stoma. Thus, stomal dilation (answer E) is incorrect.

References

1. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans J.A., Muthusamy V.R., et al. The role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;8:1063-72.

2. Lee J.K., Van Dam J., Morton J.M., et al. Endoscopy is accurate, safe, and effective in the assessment and management of complications following gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:575-82.

3. Yu S., Jastrow K., Clapp B., et al. Foreign material erosion after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: findings and treatment. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1216-20.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151:250-1)

A 45-year-old female with history of morbid obesity who had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) 6 months ago for weight loss presents to the emergency department with acute on chronic abdominal pain. She reports that these upper gastrointestinal symptoms have been occurring with increasing frequency over the past 2 months. Her pain is epigastric, postprandial, and without radiation.

Dr. Storm and Dr. Thompson are in the department of medicine, division of gastroenterology, hepatology and endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Thompson is a consultant for Olympus, Cook, and Boston Scientific.