User login

What is your diagnosis? - March 2020

Squamous metaplasia

Weight regain can accompany re-emergence of obesity-related comorbidities and, thus, early intervention is important. Although diet, exercise, and behavior modifications are fundamental, they can have limited efficacy. Thus, endoscopic management is important, with specific evaluation for gastrogastric fistulae, pouch dilation, and GJA dilation, all of which can be successfully intervened upon endoscopically. For GJA dilation in particular, APC has been used with promising results.1

In the normal GI tract, the esophagus is lined with squamous epithelium, and the stomach is lined with columnar epithelium. One of the most well-known and well-documented scenarios in which the typical mucosal lining is replaced by abnormal mucosa is Barrett’s esophagus (BE). BE is defined by the replacement of the normal distal squamous epithelial lining with columnar epithelium with a minimum length of 1 cm (tongues or circumferential) containing specialized intestinal metaplasia on histopathologic examination. It is well-documented that treatment of BE with thermal ablation and acid suppression therapy results in re-epithelialization of the esophagus with neosquamous mucosa.2 In contrast with this, in our patients, after we burned the gastric columnar mucosa with APC to treat their dilated GJA, the gastric pouch mucosa has been replaced with squamous epithelium, which we have termed “reverse BE.” To our knowledge, there are no reports of this condition in the literature, nor do we know the precise cause. There is a series of patients without a history of bariatric surgery who developed squamous metaplasia in the proximal gastric cardia.3 The authors hypothesized that this condition may be due to chronic mucosal injury owing to hiatal hernia, reflux, caustic ingestion, chronic gastritis, or pyloric stenosis. We suggest two potential mechanisms for this condition in our patients: 1) extending the ablation to the Z-line on the medial aspect of the pouch may allow for the distal extension of squamous mucosa during the healing process; and 2) acid suppression therapy with proton pump inhibitors after the procedure, in combination with a postoperative decrease in acid production, allows for a shift in the cell proliferation and differentiation in the pouch. Notably, although there are well-defined guidelines for surveillance of BE, owing to the risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma,2 it is unclear what clinical significance this reverse BE may have in the future. It is important to continue to monitor these patients and clarify the natural history of this finding.

References

1. Brunaldi VO, Jirapinyo P, de Moura DTH et al. Endoscopic treatment of weight regain following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2018;28:266-76.

2. Weusten B, Bisschops R, Coron E et al. Endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy. 2017;49:191-8.

3. Fass R, Sampliner RE. Extension of squamous epithelium into the proximal stomach: a newly recognized mucosal abnormality. Endoscopy. 2000;32:27-32.

Christopher C. Thompson is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Medtronic, a consultant for and has institutional grants from USGI Medical, Olympus, and Apollo Endosurgery.

ginews@gastro.org

Squamous metaplasia

Weight regain can accompany re-emergence of obesity-related comorbidities and, thus, early intervention is important. Although diet, exercise, and behavior modifications are fundamental, they can have limited efficacy. Thus, endoscopic management is important, with specific evaluation for gastrogastric fistulae, pouch dilation, and GJA dilation, all of which can be successfully intervened upon endoscopically. For GJA dilation in particular, APC has been used with promising results.1

In the normal GI tract, the esophagus is lined with squamous epithelium, and the stomach is lined with columnar epithelium. One of the most well-known and well-documented scenarios in which the typical mucosal lining is replaced by abnormal mucosa is Barrett’s esophagus (BE). BE is defined by the replacement of the normal distal squamous epithelial lining with columnar epithelium with a minimum length of 1 cm (tongues or circumferential) containing specialized intestinal metaplasia on histopathologic examination. It is well-documented that treatment of BE with thermal ablation and acid suppression therapy results in re-epithelialization of the esophagus with neosquamous mucosa.2 In contrast with this, in our patients, after we burned the gastric columnar mucosa with APC to treat their dilated GJA, the gastric pouch mucosa has been replaced with squamous epithelium, which we have termed “reverse BE.” To our knowledge, there are no reports of this condition in the literature, nor do we know the precise cause. There is a series of patients without a history of bariatric surgery who developed squamous metaplasia in the proximal gastric cardia.3 The authors hypothesized that this condition may be due to chronic mucosal injury owing to hiatal hernia, reflux, caustic ingestion, chronic gastritis, or pyloric stenosis. We suggest two potential mechanisms for this condition in our patients: 1) extending the ablation to the Z-line on the medial aspect of the pouch may allow for the distal extension of squamous mucosa during the healing process; and 2) acid suppression therapy with proton pump inhibitors after the procedure, in combination with a postoperative decrease in acid production, allows for a shift in the cell proliferation and differentiation in the pouch. Notably, although there are well-defined guidelines for surveillance of BE, owing to the risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma,2 it is unclear what clinical significance this reverse BE may have in the future. It is important to continue to monitor these patients and clarify the natural history of this finding.

References

1. Brunaldi VO, Jirapinyo P, de Moura DTH et al. Endoscopic treatment of weight regain following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2018;28:266-76.

2. Weusten B, Bisschops R, Coron E et al. Endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy. 2017;49:191-8.

3. Fass R, Sampliner RE. Extension of squamous epithelium into the proximal stomach: a newly recognized mucosal abnormality. Endoscopy. 2000;32:27-32.

Christopher C. Thompson is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Medtronic, a consultant for and has institutional grants from USGI Medical, Olympus, and Apollo Endosurgery.

ginews@gastro.org

Squamous metaplasia

Weight regain can accompany re-emergence of obesity-related comorbidities and, thus, early intervention is important. Although diet, exercise, and behavior modifications are fundamental, they can have limited efficacy. Thus, endoscopic management is important, with specific evaluation for gastrogastric fistulae, pouch dilation, and GJA dilation, all of which can be successfully intervened upon endoscopically. For GJA dilation in particular, APC has been used with promising results.1

In the normal GI tract, the esophagus is lined with squamous epithelium, and the stomach is lined with columnar epithelium. One of the most well-known and well-documented scenarios in which the typical mucosal lining is replaced by abnormal mucosa is Barrett’s esophagus (BE). BE is defined by the replacement of the normal distal squamous epithelial lining with columnar epithelium with a minimum length of 1 cm (tongues or circumferential) containing specialized intestinal metaplasia on histopathologic examination. It is well-documented that treatment of BE with thermal ablation and acid suppression therapy results in re-epithelialization of the esophagus with neosquamous mucosa.2 In contrast with this, in our patients, after we burned the gastric columnar mucosa with APC to treat their dilated GJA, the gastric pouch mucosa has been replaced with squamous epithelium, which we have termed “reverse BE.” To our knowledge, there are no reports of this condition in the literature, nor do we know the precise cause. There is a series of patients without a history of bariatric surgery who developed squamous metaplasia in the proximal gastric cardia.3 The authors hypothesized that this condition may be due to chronic mucosal injury owing to hiatal hernia, reflux, caustic ingestion, chronic gastritis, or pyloric stenosis. We suggest two potential mechanisms for this condition in our patients: 1) extending the ablation to the Z-line on the medial aspect of the pouch may allow for the distal extension of squamous mucosa during the healing process; and 2) acid suppression therapy with proton pump inhibitors after the procedure, in combination with a postoperative decrease in acid production, allows for a shift in the cell proliferation and differentiation in the pouch. Notably, although there are well-defined guidelines for surveillance of BE, owing to the risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma,2 it is unclear what clinical significance this reverse BE may have in the future. It is important to continue to monitor these patients and clarify the natural history of this finding.

References

1. Brunaldi VO, Jirapinyo P, de Moura DTH et al. Endoscopic treatment of weight regain following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Surg. 2018;28:266-76.

2. Weusten B, Bisschops R, Coron E et al. Endoscopic management of Barrett’s esophagus: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Position Statement. Endoscopy. 2017;49:191-8.

3. Fass R, Sampliner RE. Extension of squamous epithelium into the proximal stomach: a newly recognized mucosal abnormality. Endoscopy. 2000;32:27-32.

Christopher C. Thompson is a consultant for Boston Scientific and Medtronic, a consultant for and has institutional grants from USGI Medical, Olympus, and Apollo Endosurgery.

ginews@gastro.org

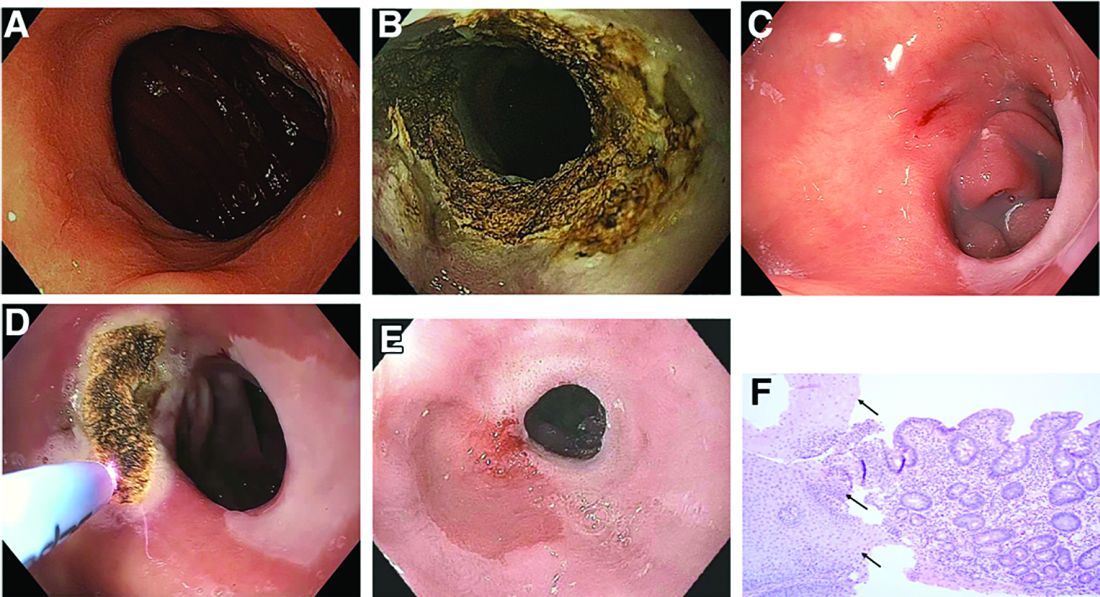

We describe three unique presentations of patients with a prior history of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass who were referred for endoscopic treatment of weight regain. All of the patients had failed prior attempts at lifestyle modifications and pharmacologic weight loss treatment. On physical examination, their body mass indices ranged from 27 to 30 kg/m2, but examination and complete laboratory evaluation, including thyroid-stimulating hormone, were otherwise normal. During the first upper gastrointestinal esophagogastroduodenoscopies, the pouch and the gastrojejunal anastomosis (GJA) were characterized by healthy appearing mucosa. In all three cases, the pouch size measured between 3 and 5 cm and the GJA was dilated, with diameters of more than 20 mm (Figure A). Laser resurfacing of the stoma by argon plasma coagulation (APC) at 0.8 L/min and 70 watts was successfully performed in a 1-cm concentric ring fashion around the gastric side of the GJA (Figure B). Three months after the initial APC, the patients returned for reevaluation. The pouch mucosa again seemed to be normal, but there was persistent, albeit improved, dilation of the GJA. Repeat APC sessions were performed without any adverse events.

On their next follow-up esophagogastroduodenoscopies, all patients were noted to have an abnormal color of approximately 25% of their gastric pouch epithelium, which seemed to be more similar to the esophageal epithelium (Figure C). The GJAs remained dilated, measuring more than 14 mm, and their third APC sessions were performed (Figure D). The patients did well after the procedures, with significant weight loss. A 1-year follow-up endoscopy showed a 10-mm GJA, but the gastric pouch was now approximately 80%-100% covered with this abnormal epithelium (Figure E). A forceps biopsy was performed for histologic evaluation (Figure F).

What is the histopathologic diagnosis of this finding?

Unraveling a patient’s post-op symptoms

The correct answer is B: endoscopic suture removal. As the prevalence of bariatric surgery increases to address the obesity epidemic, endoscopists are increasingly called upon to evaluate postbariatric patients.1 In one case series of patients undergoing EGD for upper GI symptoms post-RYGB, normal postsurgical anatomy was found in 31.6%, anastomotic stricture in 52.6%, marginal ulcer in 15.8%, unraveled suture material causing functional obstruction in 4% and gastro-gastric fistula in 2.6% of cases.2 Another series reported unraveled suture material thought to be contributing to upper GI symptoms in up to 10% of cases.3 Suture material is found by a mean of 34 weeks after RYGB, and presenting symptoms include abdominal pain in 65%, nausea 52%, dysphagia 22%, and melena in 13%. Unraveled suture material may be associated with marginal ulceration, or may cause obstruction as it presents a mechanical obstruction to foodstuff as it passes through the gastrojejunal anastomosis. A series of 29 therapeutic endoscopic suture removal cases reported resolution or improvement of symptoms in 83% of patients and no complications or anastomotic leaks.3

While symptomatic management with antiemetics and analgesics (answer A) is important in managing this patient, it will not lead to definitive management of her underlying condition. The patient may require laparosopic surgical revision (answer C) if her symptoms persist after endoscopic suture removal, but it is premature to recommend this. An upper GI series (answer D) would be helpful in diagnosing a gastro-gastric fistula in this patient population, but the endoscopic evaluation suggests suture material leading to food bolus impaction and gut irritation is the cause of her symptoms. Finally, while the patient’s symptoms of intermittent obstruction raises concerns for gastrojejunal stenosis, the endoscopic exam showed a normal-caliber stoma. Thus, stomal dilation (answer E) is incorrect.

References

1. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans J.A., Muthusamy V.R., et al. The role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;8:1063-72.

2. Lee J.K., Van Dam J., Morton J.M., et al. Endoscopy is accurate, safe, and effective in the assessment and management of complications following gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:575-82.

3. Yu S., Jastrow K., Clapp B., et al. Foreign material erosion after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: findings and treatment. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1216-20.

The correct answer is B: endoscopic suture removal. As the prevalence of bariatric surgery increases to address the obesity epidemic, endoscopists are increasingly called upon to evaluate postbariatric patients.1 In one case series of patients undergoing EGD for upper GI symptoms post-RYGB, normal postsurgical anatomy was found in 31.6%, anastomotic stricture in 52.6%, marginal ulcer in 15.8%, unraveled suture material causing functional obstruction in 4% and gastro-gastric fistula in 2.6% of cases.2 Another series reported unraveled suture material thought to be contributing to upper GI symptoms in up to 10% of cases.3 Suture material is found by a mean of 34 weeks after RYGB, and presenting symptoms include abdominal pain in 65%, nausea 52%, dysphagia 22%, and melena in 13%. Unraveled suture material may be associated with marginal ulceration, or may cause obstruction as it presents a mechanical obstruction to foodstuff as it passes through the gastrojejunal anastomosis. A series of 29 therapeutic endoscopic suture removal cases reported resolution or improvement of symptoms in 83% of patients and no complications or anastomotic leaks.3

While symptomatic management with antiemetics and analgesics (answer A) is important in managing this patient, it will not lead to definitive management of her underlying condition. The patient may require laparosopic surgical revision (answer C) if her symptoms persist after endoscopic suture removal, but it is premature to recommend this. An upper GI series (answer D) would be helpful in diagnosing a gastro-gastric fistula in this patient population, but the endoscopic evaluation suggests suture material leading to food bolus impaction and gut irritation is the cause of her symptoms. Finally, while the patient’s symptoms of intermittent obstruction raises concerns for gastrojejunal stenosis, the endoscopic exam showed a normal-caliber stoma. Thus, stomal dilation (answer E) is incorrect.

References

1. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans J.A., Muthusamy V.R., et al. The role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;8:1063-72.

2. Lee J.K., Van Dam J., Morton J.M., et al. Endoscopy is accurate, safe, and effective in the assessment and management of complications following gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:575-82.

3. Yu S., Jastrow K., Clapp B., et al. Foreign material erosion after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: findings and treatment. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1216-20.

The correct answer is B: endoscopic suture removal. As the prevalence of bariatric surgery increases to address the obesity epidemic, endoscopists are increasingly called upon to evaluate postbariatric patients.1 In one case series of patients undergoing EGD for upper GI symptoms post-RYGB, normal postsurgical anatomy was found in 31.6%, anastomotic stricture in 52.6%, marginal ulcer in 15.8%, unraveled suture material causing functional obstruction in 4% and gastro-gastric fistula in 2.6% of cases.2 Another series reported unraveled suture material thought to be contributing to upper GI symptoms in up to 10% of cases.3 Suture material is found by a mean of 34 weeks after RYGB, and presenting symptoms include abdominal pain in 65%, nausea 52%, dysphagia 22%, and melena in 13%. Unraveled suture material may be associated with marginal ulceration, or may cause obstruction as it presents a mechanical obstruction to foodstuff as it passes through the gastrojejunal anastomosis. A series of 29 therapeutic endoscopic suture removal cases reported resolution or improvement of symptoms in 83% of patients and no complications or anastomotic leaks.3

While symptomatic management with antiemetics and analgesics (answer A) is important in managing this patient, it will not lead to definitive management of her underlying condition. The patient may require laparosopic surgical revision (answer C) if her symptoms persist after endoscopic suture removal, but it is premature to recommend this. An upper GI series (answer D) would be helpful in diagnosing a gastro-gastric fistula in this patient population, but the endoscopic evaluation suggests suture material leading to food bolus impaction and gut irritation is the cause of her symptoms. Finally, while the patient’s symptoms of intermittent obstruction raises concerns for gastrojejunal stenosis, the endoscopic exam showed a normal-caliber stoma. Thus, stomal dilation (answer E) is incorrect.

References

1. ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Evans J.A., Muthusamy V.R., et al. The role of endoscopy in the bariatric surgery patient. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;8:1063-72.

2. Lee J.K., Van Dam J., Morton J.M., et al. Endoscopy is accurate, safe, and effective in the assessment and management of complications following gastric bypass surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:575-82.

3. Yu S., Jastrow K., Clapp B., et al. Foreign material erosion after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: findings and treatment. Surg Endosc. 2007;21:1216-20.

Published previously in Gastroenterology (2016;151:250-1)

A 45-year-old female with history of morbid obesity who had undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) 6 months ago for weight loss presents to the emergency department with acute on chronic abdominal pain. She reports that these upper gastrointestinal symptoms have been occurring with increasing frequency over the past 2 months. Her pain is epigastric, postprandial, and without radiation.

Dr. Storm and Dr. Thompson are in the department of medicine, division of gastroenterology, hepatology and endoscopy, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. Dr. Thompson is a consultant for Olympus, Cook, and Boston Scientific.