User login

Macules and abdominal pain

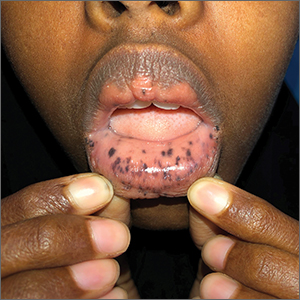

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

This patient was given a diagnosis of Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS) based on the characteristic pigmented mucocutaneous macules and numerous polyps in her stomach and small bowel. PJS is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by mucocutaneous pigmentation, polyposis of the GI tract, and increased cancer risk. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 100,000.1 Genetic testing for the STK11 gene mutation, which is found in 70% of familial cases and 30% to 67% of sporadic cases, is not required for diagnosis.1

The bluish brown to black spots of PJS often are apparent at birth or in early infancy. They are most common on the lips, buccal mucosa, perioral region, palms, and soles.

The polyps may cause bleeding, anemia, and abdominal pain due to intussusception, obstruction, or infarction.2 Polyps usually are benign, but patients are at increased risk of GI and non-GI malignancies such as breast, pancreas, lung, and reproductive tract cancers.1

PJS can be differentiated from other causes of hyperpigmentation by clinical presentation and/or genetic testing. The diagnosis of PJS is made using the following criteria: (1) two or more histologically confirmed PJS polyps, (2) any number of PJS polyps and a family history of PJS, (3) characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation and a family history of PJS, or (4) any number of PJS polyps and characteristic mucocutaneous pigmentation.2

It’s recommended that polyps be removed when technically feasible.3 Pigmented macules do not require treatment. Macules on the lips may disappear with time, while those on the buccal mucosa persist. The lip lesions can be lightened with chemical peels or laser.

This patient underwent laparotomy, which revealed a grossly dilated and gangrenous small bowel segment. Intussusception was not present and was thought to have spontaneously reduced. Resection and anastomosis of the affected small bowel was performed. The patient’s postoperative course was uneventful, and her diarrhea and abdominal pain resolved. A colonoscopy was normal, and the health care team explained that she would require follow-up and surveillance of her condition due to the high risk of future cancers.

This case was adapted from: Warsame MO, McMichael JR. Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea. J Fam Pract. 2020;69:365,366,368.

Photos courtesy of Mohamed Omar Warsame, MBBS, and Josette R. McMichael, MD

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

1. Kopacova M, Tacheci I, Rejchrt S, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: diagnostic and therapeutic approach. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:5397-5408.

2. Beggs AD, Latchford AR, Vasen HF, et al. Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: a systematic review and recommendations for management. Gut. 2010;59:975-986.

3. van Lier MG, Mathus-Vliegen EM, Wagner A, et al. High cumulative risk of intussusception in patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome: time to update surveillance guidelines? Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:940-945.

Teen with hyperpigmented skin lesions

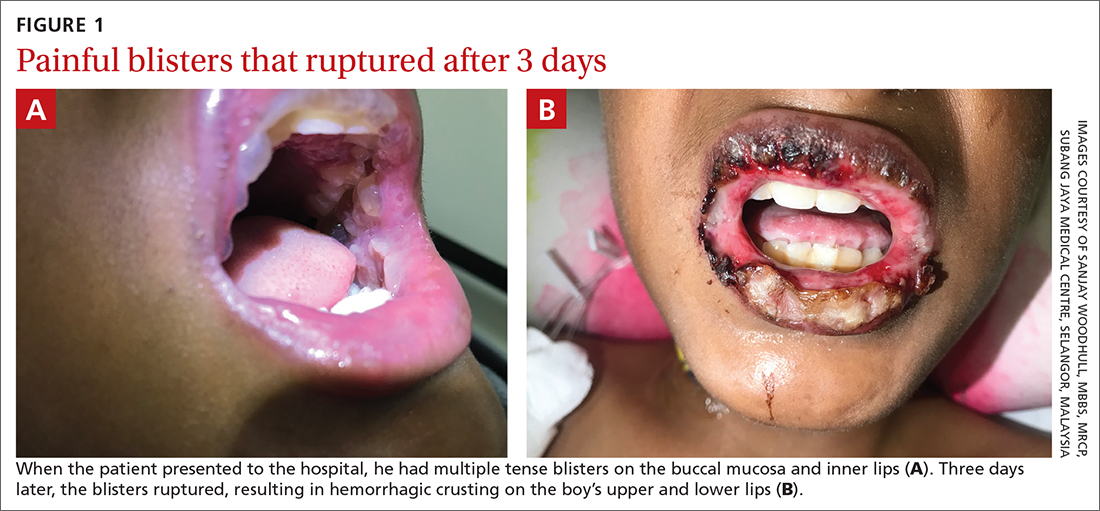

These hyperpigmented lesions with fine scale on the outer edges are characteristic of pityriasis versicolor, also known as tinea versicolor. These macules (or patches) are commonly found on the trunk, proximal extremities, or neck. The lesions can be hypopigmented (pityriasis versicolor alba), hyperpigmented (pityriasis versicolor nigra), or erythematous (pityriasis versicolor rubra).1 It is common to see hyperpigmentation in people with darker skin tones, as was the case with this patient. Pityriasis versicolor is often asymptomatic, but patients may describe mild to moderate pruritis.

Pityriasis versicolor is a common fungal infection of the superficial layers of the dermis caused by Malassezia furfur.2 Impaired immunity and excessive sweating are risk factors for pityriasis versicolor; other risk factors include having a family member with tinea versicolor and living in a hot, humid region.1 Adolescents and young adults are most often affected.1

An evoked scale sign is a helpful tool to confirm the diagnosis clinically.3 Scale will appear when you stretch the affected skin with your thumb and index finger (or you scrape the area with a scalpel blade).3 If there is doubt about the diagnosis, use a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation; a positive test will reveal the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern.1

Selenium sulfide 2.5%, zinc pyrithione 1%, and ketoconazole 2% shampoo are effective topical treatments. The shampoo is applied full strength to the affected skin daily for 5 to 10 minutes before it’s washed off. This can be done for 1 to 4 weeks, with longer treatment courses resulting in higher cure rates. Systemic therapy is reserved for patients with widespread infection or those who do not respond to topical treatment.4 It’s important to advise patients that the restoration of normal skin pigmentation can takes months.

This patient was treated with ketoconazole 2% shampoo for 3 weeks. A complete return of skin color was achieved 6 months after completion of therapy.

Image courtesy of Judy Jasser, MD. Text courtesy of Judy Jasser, MD, Department of Pediatrics, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Crespo-Erchiga, V, Florencio, VD. Malassezia yeasts and pityriasis versicolor. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:139-147. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000216624.21069.61

2. Gupta, AK, Bluhm R, Summerbell R. Pityriasis versicolor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:19-33. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00378.x

3. Han, A, Calcara DA, Stoecker WV, et al. Evoked scale sign of tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1078. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.203

4. Renati S, Cukras A, Bigby M. Pityriasis versicolor. BMJ. 2015;350:h1394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1394

These hyperpigmented lesions with fine scale on the outer edges are characteristic of pityriasis versicolor, also known as tinea versicolor. These macules (or patches) are commonly found on the trunk, proximal extremities, or neck. The lesions can be hypopigmented (pityriasis versicolor alba), hyperpigmented (pityriasis versicolor nigra), or erythematous (pityriasis versicolor rubra).1 It is common to see hyperpigmentation in people with darker skin tones, as was the case with this patient. Pityriasis versicolor is often asymptomatic, but patients may describe mild to moderate pruritis.

Pityriasis versicolor is a common fungal infection of the superficial layers of the dermis caused by Malassezia furfur.2 Impaired immunity and excessive sweating are risk factors for pityriasis versicolor; other risk factors include having a family member with tinea versicolor and living in a hot, humid region.1 Adolescents and young adults are most often affected.1

An evoked scale sign is a helpful tool to confirm the diagnosis clinically.3 Scale will appear when you stretch the affected skin with your thumb and index finger (or you scrape the area with a scalpel blade).3 If there is doubt about the diagnosis, use a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation; a positive test will reveal the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern.1

Selenium sulfide 2.5%, zinc pyrithione 1%, and ketoconazole 2% shampoo are effective topical treatments. The shampoo is applied full strength to the affected skin daily for 5 to 10 minutes before it’s washed off. This can be done for 1 to 4 weeks, with longer treatment courses resulting in higher cure rates. Systemic therapy is reserved for patients with widespread infection or those who do not respond to topical treatment.4 It’s important to advise patients that the restoration of normal skin pigmentation can takes months.

This patient was treated with ketoconazole 2% shampoo for 3 weeks. A complete return of skin color was achieved 6 months after completion of therapy.

Image courtesy of Judy Jasser, MD. Text courtesy of Judy Jasser, MD, Department of Pediatrics, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

These hyperpigmented lesions with fine scale on the outer edges are characteristic of pityriasis versicolor, also known as tinea versicolor. These macules (or patches) are commonly found on the trunk, proximal extremities, or neck. The lesions can be hypopigmented (pityriasis versicolor alba), hyperpigmented (pityriasis versicolor nigra), or erythematous (pityriasis versicolor rubra).1 It is common to see hyperpigmentation in people with darker skin tones, as was the case with this patient. Pityriasis versicolor is often asymptomatic, but patients may describe mild to moderate pruritis.

Pityriasis versicolor is a common fungal infection of the superficial layers of the dermis caused by Malassezia furfur.2 Impaired immunity and excessive sweating are risk factors for pityriasis versicolor; other risk factors include having a family member with tinea versicolor and living in a hot, humid region.1 Adolescents and young adults are most often affected.1

An evoked scale sign is a helpful tool to confirm the diagnosis clinically.3 Scale will appear when you stretch the affected skin with your thumb and index finger (or you scrape the area with a scalpel blade).3 If there is doubt about the diagnosis, use a potassium hydroxide (KOH) preparation; a positive test will reveal the classic “spaghetti and meatballs” pattern.1

Selenium sulfide 2.5%, zinc pyrithione 1%, and ketoconazole 2% shampoo are effective topical treatments. The shampoo is applied full strength to the affected skin daily for 5 to 10 minutes before it’s washed off. This can be done for 1 to 4 weeks, with longer treatment courses resulting in higher cure rates. Systemic therapy is reserved for patients with widespread infection or those who do not respond to topical treatment.4 It’s important to advise patients that the restoration of normal skin pigmentation can takes months.

This patient was treated with ketoconazole 2% shampoo for 3 weeks. A complete return of skin color was achieved 6 months after completion of therapy.

Image courtesy of Judy Jasser, MD. Text courtesy of Judy Jasser, MD, Department of Pediatrics, and Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Crespo-Erchiga, V, Florencio, VD. Malassezia yeasts and pityriasis versicolor. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:139-147. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000216624.21069.61

2. Gupta, AK, Bluhm R, Summerbell R. Pityriasis versicolor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:19-33. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00378.x

3. Han, A, Calcara DA, Stoecker WV, et al. Evoked scale sign of tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1078. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.203

4. Renati S, Cukras A, Bigby M. Pityriasis versicolor. BMJ. 2015;350:h1394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1394

1. Crespo-Erchiga, V, Florencio, VD. Malassezia yeasts and pityriasis versicolor. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2006;19:139-147. doi: 10.1097/01.qco.0000216624.21069.61

2. Gupta, AK, Bluhm R, Summerbell R. Pityriasis versicolor. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:19-33. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00378.x

3. Han, A, Calcara DA, Stoecker WV, et al. Evoked scale sign of tinea versicolor. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1078. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.203

4. Renati S, Cukras A, Bigby M. Pityriasis versicolor. BMJ. 2015;350:h1394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1394

A worsening abdominal rash

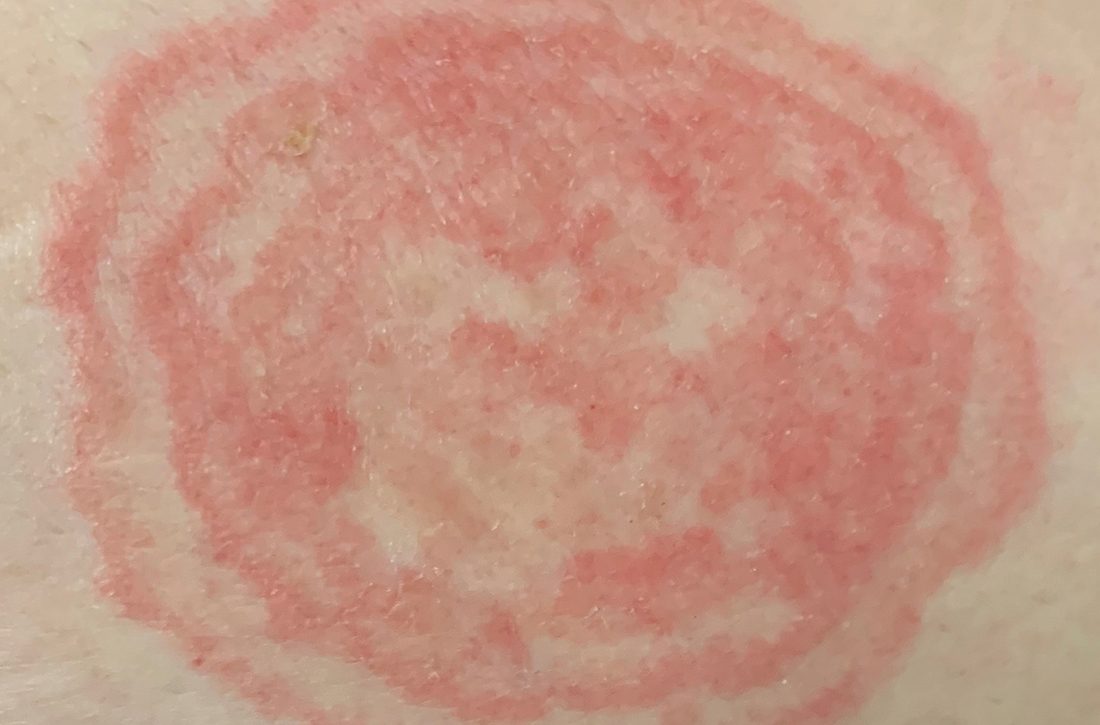

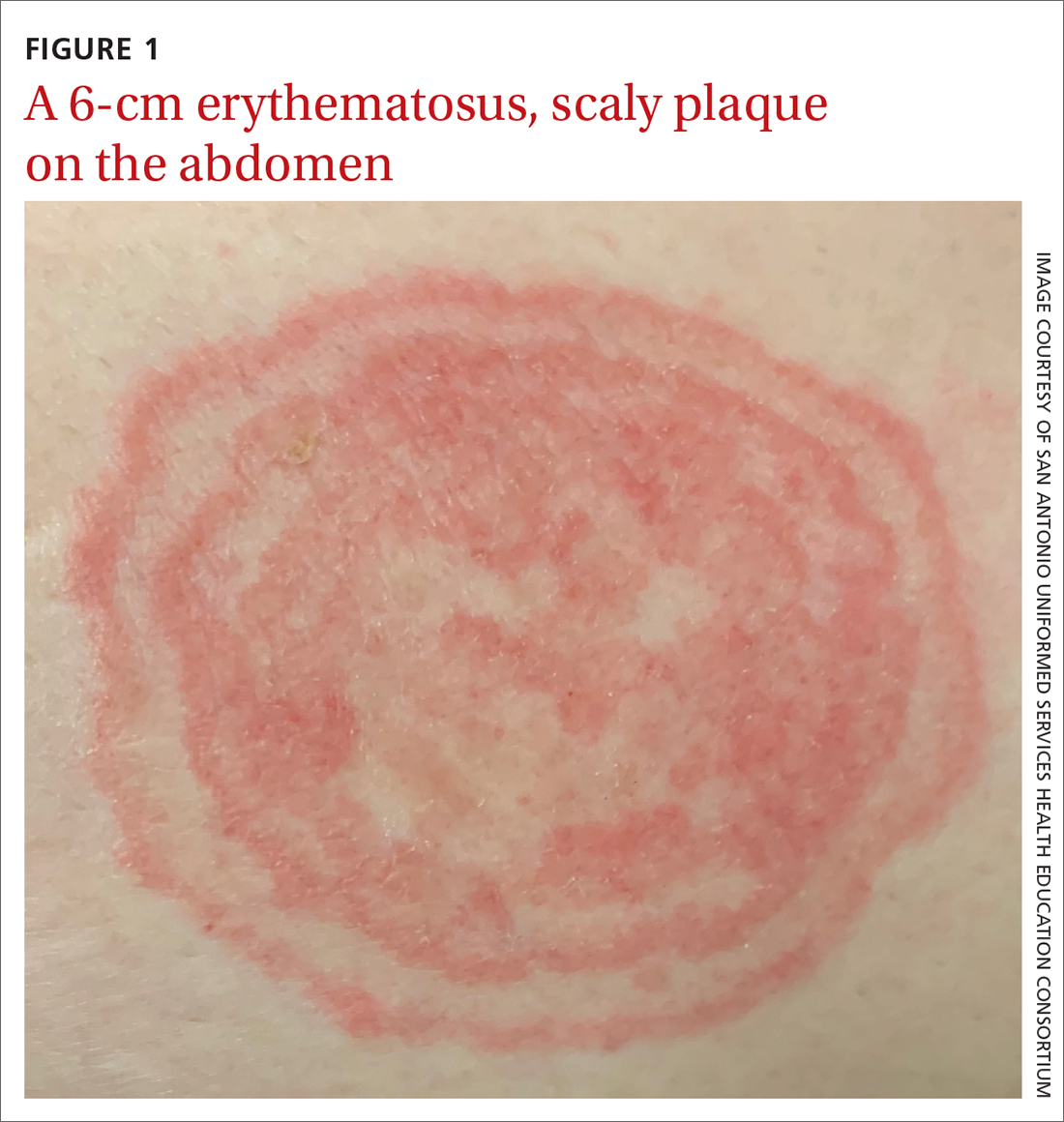

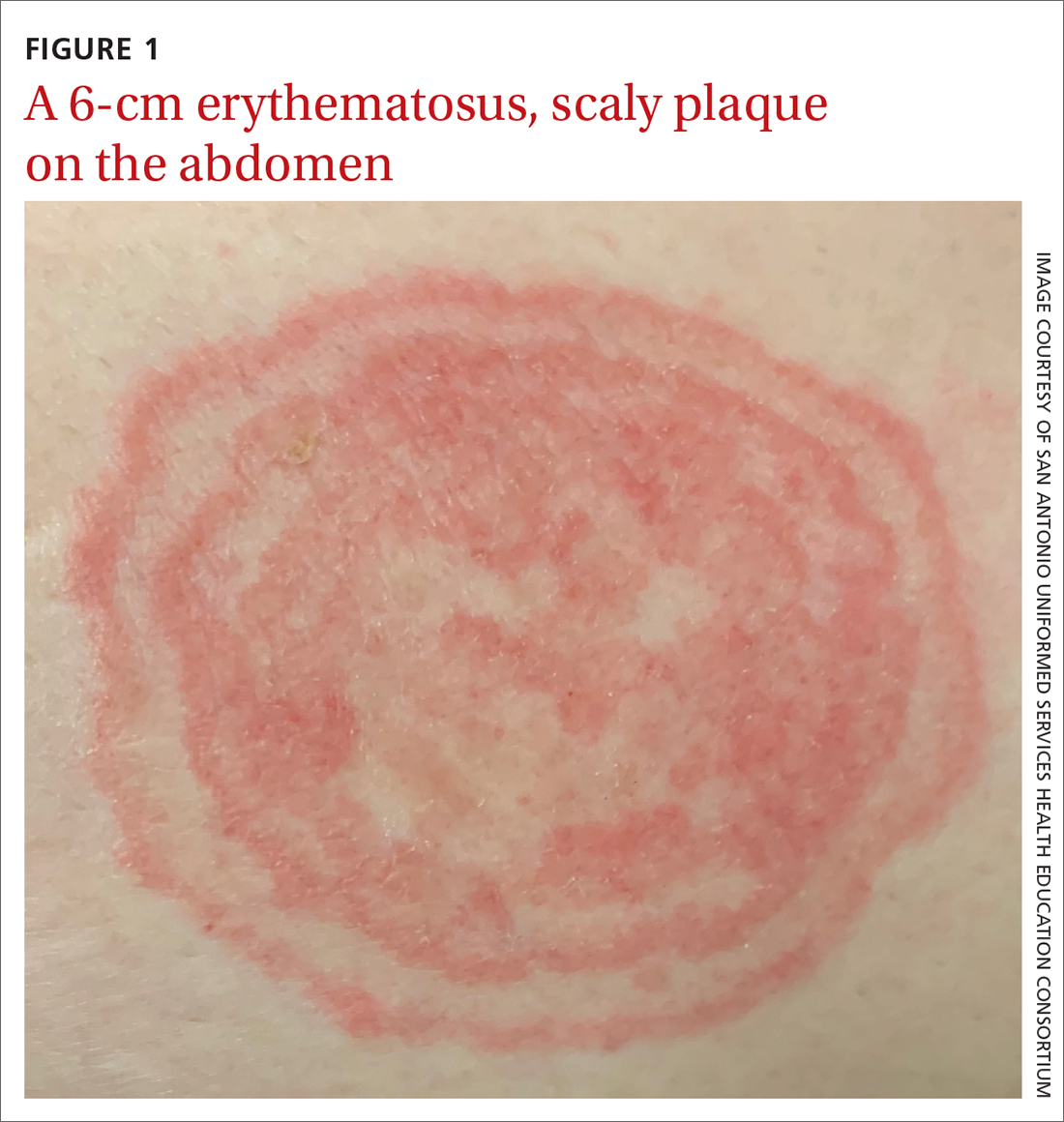

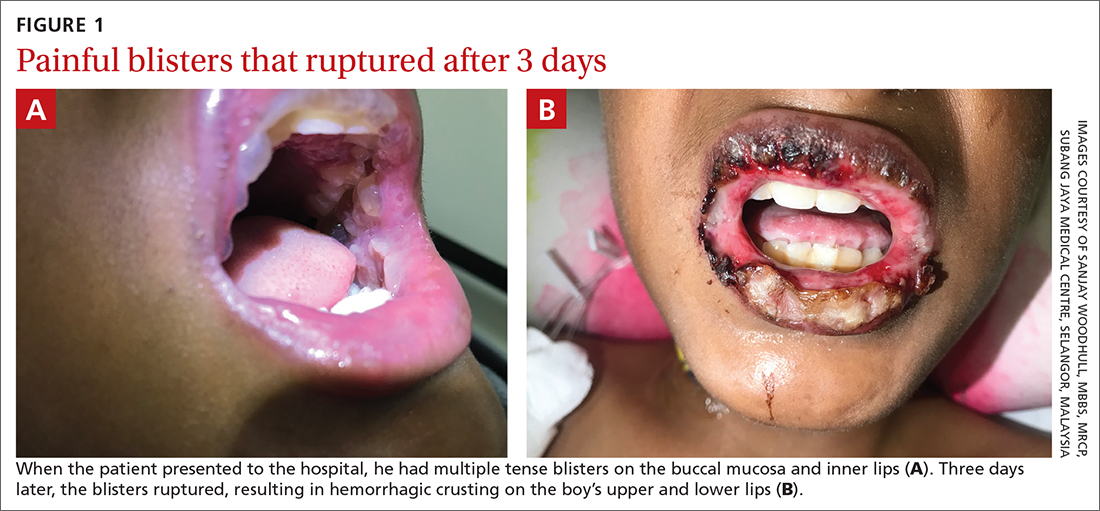

A 48-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented to Dermatology for evaluation of a 6-cm abdominal lesion that had been present for 5 weeks (FIGURE 1). The lesion was originally about the size of a quarter, but it started to enlarge after treatment of an asthma exacerbation with a 4-day course of prednisone. It continued to grow after another physician, likely presuming the lesion was a corticosteroid-responsive dermatosis (eg, nummular eczema, granuloma annulare, or erythema annulare centrifugum), prescribed a 2-week trial of clobetasol ointment. Physical examination revealed a mildly pruritic, 6-cm erythematous plaque with scaly, annular, concentric rings on the left lower abdomen. The patient had no travel history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea incognito

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea incognito, a form of tinea corporis that is exacerbated by the inappropriate use of corticosteroids in the management of a cutaneous fungal infection.1 Furthermore, this patient’s case was consistent with tinea pseudoimbricata, a variant of tinea incognito. Tinea pseudoimbricata is characterized by striking concentric scaly rings that mimic tinea imbricata, a fungal infection caused by the dermatophyte Trichophyton concentricum, which is commonly found in tropical areas.2

A common infection is alteredby steroid use

Tinea corporis has a relatively high prevalence. Approximately 10% to 20% of the world population is affected by fungal skin infections.3

T rubrum is the most common cause of tinea corporis. Other causes include T tonsurans, T interdigitale, T violaceum, Microsporum canis, M gypseum, and M audouinii.

Tinea corporis can be acquired through direct contact with an infected person, animal, or fomite. It may also be acquired through autoinoculation from another area of the body containing a dermatophyte fungal infection. Tinea corporis lesions are usually pruritic, erythematous, annular plaques with overlying scale and central clearing.

How steroid use can change the picture. Treatment with corticosteroids is ineffective for fungal skin infections and causes immunosuppression, allowing the fungus to thrive. This patient had been treated with a topical steroid (clobetasol) for the abdominal lesion caused by tinea corporis, as well as an oral steroid (prednisone) for an asthma exacerbation. These steroid treatments caused the abdominal lesion to morph from the typical appearance of tinea corporis—classically an annular erythematous plaque with overlying scale and central clearing—to an erythematous plaque with striking concentric scaly rings.

Continue to: Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

The differential diagnosis for an annular skin lesion includes not only tinea corporis, but also superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, pityriasis rosea, granuloma annulare, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and nummular eczema.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, like tinea corporis, has scale. But the location of the scale sets the 2 apart. Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum lesions have a central trailing scale, whereas tinea corporis lesions have a peripheral leading scale.4

Pityriasis rosea forms multiple lesions in a “Christmas tree” pattern on the trunk, sometimes beginning with a single herald patch. Our patient’s single lesion with concentric scaly rings was inconsistent with the distribution and quality of the lesions in pityriasis rosea.4

Granuloma annulare lesions are smooth, nonscaly plaques that are most often seen on the dorsal hands and feet. The scaly manifestation of our patient’s lesion was not consistent with this diagnosis.4

SCLE lesions are typically photodistributed on sun-exposed skin (eg, the neck, upper trunk, or arms), whereas our patient’s lesion involved a sun-protected site.4

Continue to: Nummular eczema

Nummular eczema can be differentiated from tinea corporis by potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination. Nummular eczema is characterized by a negative KOH exam and response to topical corticosteroids.4

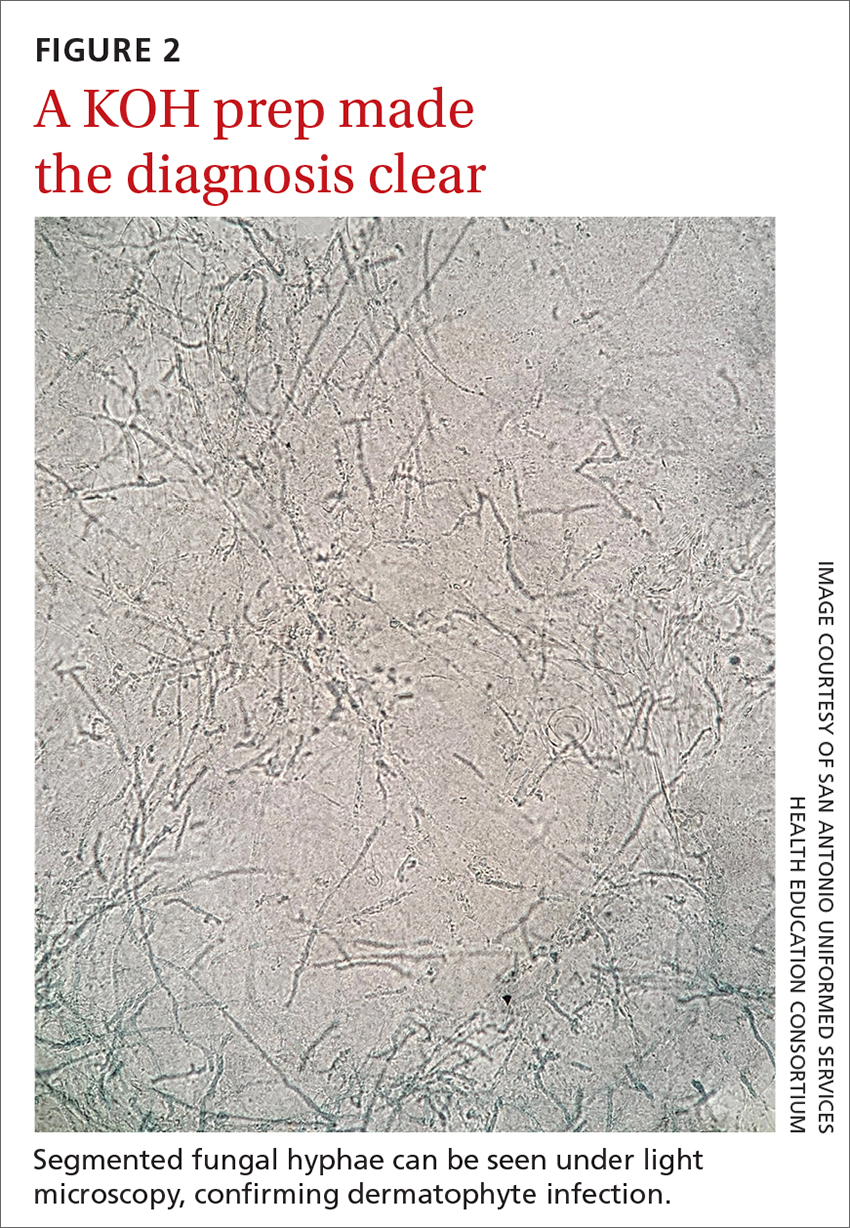

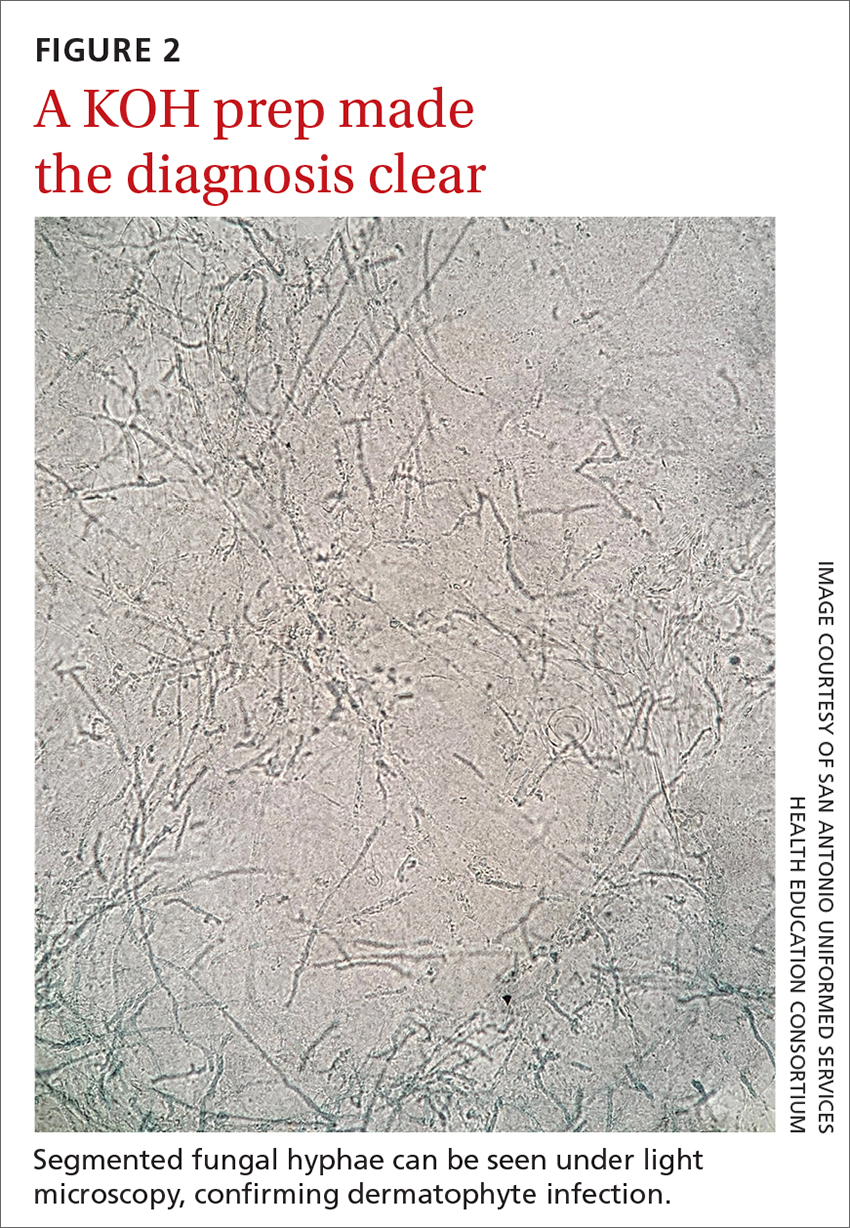

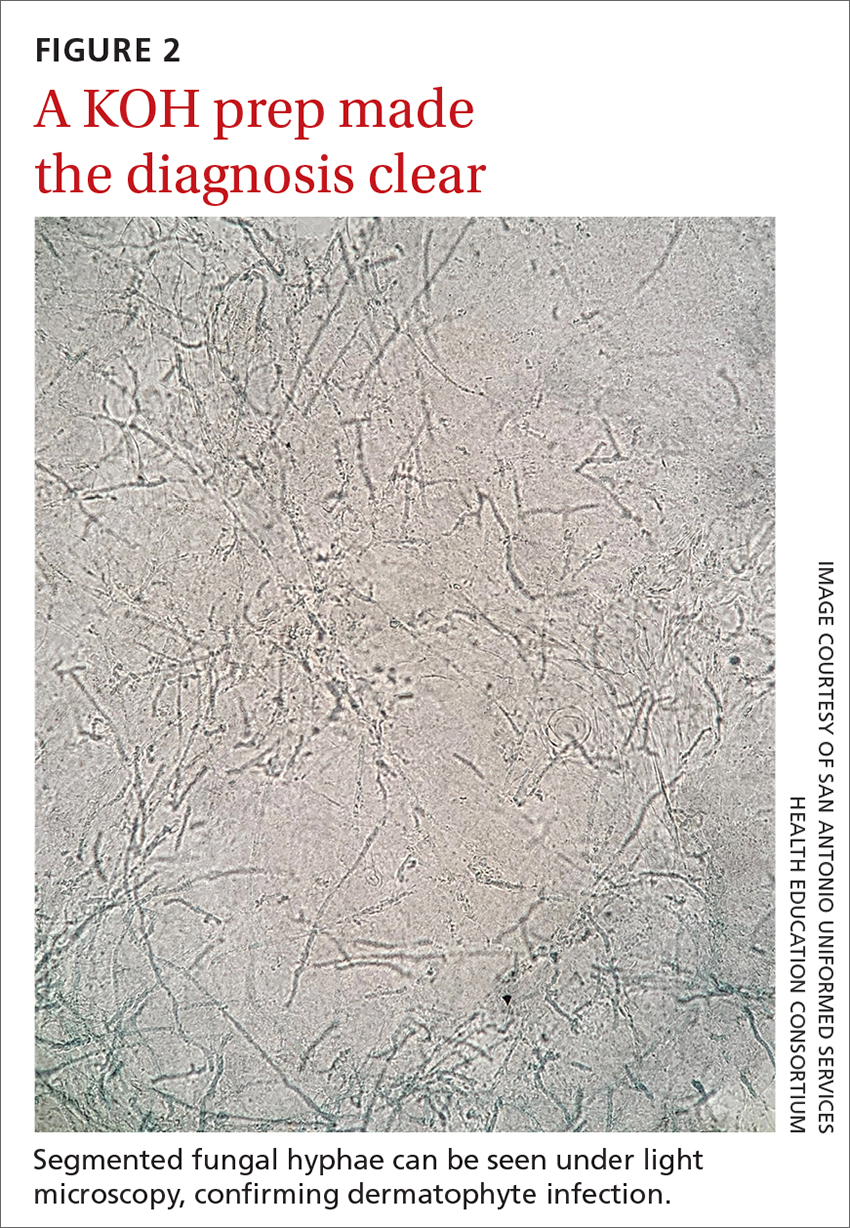

Performing a KOH examination, using the skin scrapings from the active border of a plaque, is useful on any lesion with potential fungal etiology. If the cause is indeed a dermatophyte infection, segmented fungal hyphae will be seen under light microscopy (FIGURE 2).1 If a KOH examination is not feasible, a skin scraping can be performed with a surgical scalpel blade and collected in a sterile urine cup for stain and culture at a qualified laboratory.

Topical and oral antifungal medications combat dermatophyte fungi

Treatments for cutaneous infections caused by dermatophyte fungi, such as tinea corporis, include topical and oral antifungals. The choice of agent depends on the extent of the disease.

Limited, localized disease can be treated topically with allylamines (terbinafine, naftifine) or imidazoles (clotrimazole). Other topical agents, such as butenafine, ciclopirox, and tolnaftate, also may be used.

Extensive disease, or tinea infection of vellus hairs, may require treatment with oral antifungal medications, such as the azoles (itraconazole, fluconazole), allylamines (terbinafine), or griseofulvin. Systemic therapy with oral antifungals has been associated with liver damage; therefore, oral therapy should not be used in patients with liver disease and liver enzymes should be monitored when appropriate.5 Nystatin is not effective in treating dermatophyte fungal infections.1

One complication of the inappropriate use of steroids on a dermatophyte infection is an increased risk of the fungus extending from the superficial skin into the hair follicles in the dermis, resulting in a condition known as Majocchi granuloma. Follicular infection is more severe and requires oral antifungal medication, such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, or griseofulvin.1

Our patient was treated with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks, due to the possibility of follicular infection. After the completion of 4 weeks of therapy, the patient’s cutaneous symptoms had resolved.

1. Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated November 8, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections

2. Lederman E, Craft N, Burgin S. Tinea imbricata in adult. VisualDx. Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52399

3. El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD009992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009992.pub2

4. Unwala R. Approach to the patient with annular skin lesions. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated September 7, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-annular-skin-lesions

5. Wong V, High W, Burgin S. Tinea corporis in adult. VisualDx. Updated March 24, 2019. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52396#Therapy

A 48-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented to Dermatology for evaluation of a 6-cm abdominal lesion that had been present for 5 weeks (FIGURE 1). The lesion was originally about the size of a quarter, but it started to enlarge after treatment of an asthma exacerbation with a 4-day course of prednisone. It continued to grow after another physician, likely presuming the lesion was a corticosteroid-responsive dermatosis (eg, nummular eczema, granuloma annulare, or erythema annulare centrifugum), prescribed a 2-week trial of clobetasol ointment. Physical examination revealed a mildly pruritic, 6-cm erythematous plaque with scaly, annular, concentric rings on the left lower abdomen. The patient had no travel history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea incognito

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea incognito, a form of tinea corporis that is exacerbated by the inappropriate use of corticosteroids in the management of a cutaneous fungal infection.1 Furthermore, this patient’s case was consistent with tinea pseudoimbricata, a variant of tinea incognito. Tinea pseudoimbricata is characterized by striking concentric scaly rings that mimic tinea imbricata, a fungal infection caused by the dermatophyte Trichophyton concentricum, which is commonly found in tropical areas.2

A common infection is alteredby steroid use

Tinea corporis has a relatively high prevalence. Approximately 10% to 20% of the world population is affected by fungal skin infections.3

T rubrum is the most common cause of tinea corporis. Other causes include T tonsurans, T interdigitale, T violaceum, Microsporum canis, M gypseum, and M audouinii.

Tinea corporis can be acquired through direct contact with an infected person, animal, or fomite. It may also be acquired through autoinoculation from another area of the body containing a dermatophyte fungal infection. Tinea corporis lesions are usually pruritic, erythematous, annular plaques with overlying scale and central clearing.

How steroid use can change the picture. Treatment with corticosteroids is ineffective for fungal skin infections and causes immunosuppression, allowing the fungus to thrive. This patient had been treated with a topical steroid (clobetasol) for the abdominal lesion caused by tinea corporis, as well as an oral steroid (prednisone) for an asthma exacerbation. These steroid treatments caused the abdominal lesion to morph from the typical appearance of tinea corporis—classically an annular erythematous plaque with overlying scale and central clearing—to an erythematous plaque with striking concentric scaly rings.

Continue to: Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

The differential diagnosis for an annular skin lesion includes not only tinea corporis, but also superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, pityriasis rosea, granuloma annulare, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and nummular eczema.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, like tinea corporis, has scale. But the location of the scale sets the 2 apart. Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum lesions have a central trailing scale, whereas tinea corporis lesions have a peripheral leading scale.4

Pityriasis rosea forms multiple lesions in a “Christmas tree” pattern on the trunk, sometimes beginning with a single herald patch. Our patient’s single lesion with concentric scaly rings was inconsistent with the distribution and quality of the lesions in pityriasis rosea.4

Granuloma annulare lesions are smooth, nonscaly plaques that are most often seen on the dorsal hands and feet. The scaly manifestation of our patient’s lesion was not consistent with this diagnosis.4

SCLE lesions are typically photodistributed on sun-exposed skin (eg, the neck, upper trunk, or arms), whereas our patient’s lesion involved a sun-protected site.4

Continue to: Nummular eczema

Nummular eczema can be differentiated from tinea corporis by potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination. Nummular eczema is characterized by a negative KOH exam and response to topical corticosteroids.4

Performing a KOH examination, using the skin scrapings from the active border of a plaque, is useful on any lesion with potential fungal etiology. If the cause is indeed a dermatophyte infection, segmented fungal hyphae will be seen under light microscopy (FIGURE 2).1 If a KOH examination is not feasible, a skin scraping can be performed with a surgical scalpel blade and collected in a sterile urine cup for stain and culture at a qualified laboratory.

Topical and oral antifungal medications combat dermatophyte fungi

Treatments for cutaneous infections caused by dermatophyte fungi, such as tinea corporis, include topical and oral antifungals. The choice of agent depends on the extent of the disease.

Limited, localized disease can be treated topically with allylamines (terbinafine, naftifine) or imidazoles (clotrimazole). Other topical agents, such as butenafine, ciclopirox, and tolnaftate, also may be used.

Extensive disease, or tinea infection of vellus hairs, may require treatment with oral antifungal medications, such as the azoles (itraconazole, fluconazole), allylamines (terbinafine), or griseofulvin. Systemic therapy with oral antifungals has been associated with liver damage; therefore, oral therapy should not be used in patients with liver disease and liver enzymes should be monitored when appropriate.5 Nystatin is not effective in treating dermatophyte fungal infections.1

One complication of the inappropriate use of steroids on a dermatophyte infection is an increased risk of the fungus extending from the superficial skin into the hair follicles in the dermis, resulting in a condition known as Majocchi granuloma. Follicular infection is more severe and requires oral antifungal medication, such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, or griseofulvin.1

Our patient was treated with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks, due to the possibility of follicular infection. After the completion of 4 weeks of therapy, the patient’s cutaneous symptoms had resolved.

A 48-YEAR-OLD WOMAN presented to Dermatology for evaluation of a 6-cm abdominal lesion that had been present for 5 weeks (FIGURE 1). The lesion was originally about the size of a quarter, but it started to enlarge after treatment of an asthma exacerbation with a 4-day course of prednisone. It continued to grow after another physician, likely presuming the lesion was a corticosteroid-responsive dermatosis (eg, nummular eczema, granuloma annulare, or erythema annulare centrifugum), prescribed a 2-week trial of clobetasol ointment. Physical examination revealed a mildly pruritic, 6-cm erythematous plaque with scaly, annular, concentric rings on the left lower abdomen. The patient had no travel history.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Tinea incognito

The patient was given a diagnosis of tinea incognito, a form of tinea corporis that is exacerbated by the inappropriate use of corticosteroids in the management of a cutaneous fungal infection.1 Furthermore, this patient’s case was consistent with tinea pseudoimbricata, a variant of tinea incognito. Tinea pseudoimbricata is characterized by striking concentric scaly rings that mimic tinea imbricata, a fungal infection caused by the dermatophyte Trichophyton concentricum, which is commonly found in tropical areas.2

A common infection is alteredby steroid use

Tinea corporis has a relatively high prevalence. Approximately 10% to 20% of the world population is affected by fungal skin infections.3

T rubrum is the most common cause of tinea corporis. Other causes include T tonsurans, T interdigitale, T violaceum, Microsporum canis, M gypseum, and M audouinii.

Tinea corporis can be acquired through direct contact with an infected person, animal, or fomite. It may also be acquired through autoinoculation from another area of the body containing a dermatophyte fungal infection. Tinea corporis lesions are usually pruritic, erythematous, annular plaques with overlying scale and central clearing.

How steroid use can change the picture. Treatment with corticosteroids is ineffective for fungal skin infections and causes immunosuppression, allowing the fungus to thrive. This patient had been treated with a topical steroid (clobetasol) for the abdominal lesion caused by tinea corporis, as well as an oral steroid (prednisone) for an asthma exacerbation. These steroid treatments caused the abdominal lesion to morph from the typical appearance of tinea corporis—classically an annular erythematous plaque with overlying scale and central clearing—to an erythematous plaque with striking concentric scaly rings.

Continue to: Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

Clinical exam can provide clues; KOH examination can reveal the Dx

The differential diagnosis for an annular skin lesion includes not only tinea corporis, but also superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, pityriasis rosea, granuloma annulare, subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE), and nummular eczema.

Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum, like tinea corporis, has scale. But the location of the scale sets the 2 apart. Superficial erythema annulare centrifugum lesions have a central trailing scale, whereas tinea corporis lesions have a peripheral leading scale.4

Pityriasis rosea forms multiple lesions in a “Christmas tree” pattern on the trunk, sometimes beginning with a single herald patch. Our patient’s single lesion with concentric scaly rings was inconsistent with the distribution and quality of the lesions in pityriasis rosea.4

Granuloma annulare lesions are smooth, nonscaly plaques that are most often seen on the dorsal hands and feet. The scaly manifestation of our patient’s lesion was not consistent with this diagnosis.4

SCLE lesions are typically photodistributed on sun-exposed skin (eg, the neck, upper trunk, or arms), whereas our patient’s lesion involved a sun-protected site.4

Continue to: Nummular eczema

Nummular eczema can be differentiated from tinea corporis by potassium hydroxide (KOH) examination. Nummular eczema is characterized by a negative KOH exam and response to topical corticosteroids.4

Performing a KOH examination, using the skin scrapings from the active border of a plaque, is useful on any lesion with potential fungal etiology. If the cause is indeed a dermatophyte infection, segmented fungal hyphae will be seen under light microscopy (FIGURE 2).1 If a KOH examination is not feasible, a skin scraping can be performed with a surgical scalpel blade and collected in a sterile urine cup for stain and culture at a qualified laboratory.

Topical and oral antifungal medications combat dermatophyte fungi

Treatments for cutaneous infections caused by dermatophyte fungi, such as tinea corporis, include topical and oral antifungals. The choice of agent depends on the extent of the disease.

Limited, localized disease can be treated topically with allylamines (terbinafine, naftifine) or imidazoles (clotrimazole). Other topical agents, such as butenafine, ciclopirox, and tolnaftate, also may be used.

Extensive disease, or tinea infection of vellus hairs, may require treatment with oral antifungal medications, such as the azoles (itraconazole, fluconazole), allylamines (terbinafine), or griseofulvin. Systemic therapy with oral antifungals has been associated with liver damage; therefore, oral therapy should not be used in patients with liver disease and liver enzymes should be monitored when appropriate.5 Nystatin is not effective in treating dermatophyte fungal infections.1

One complication of the inappropriate use of steroids on a dermatophyte infection is an increased risk of the fungus extending from the superficial skin into the hair follicles in the dermis, resulting in a condition known as Majocchi granuloma. Follicular infection is more severe and requires oral antifungal medication, such as terbinafine, itraconazole, fluconazole, or griseofulvin.1

Our patient was treated with terbinafine 250 mg/d for 4 weeks, due to the possibility of follicular infection. After the completion of 4 weeks of therapy, the patient’s cutaneous symptoms had resolved.

1. Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated November 8, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections

2. Lederman E, Craft N, Burgin S. Tinea imbricata in adult. VisualDx. Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52399

3. El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD009992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009992.pub2

4. Unwala R. Approach to the patient with annular skin lesions. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated September 7, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-annular-skin-lesions

5. Wong V, High W, Burgin S. Tinea corporis in adult. VisualDx. Updated March 24, 2019. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52396#Therapy

1. Goldstein AO, Goldstein BG. Dermatophyte (tinea) infections. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated November 8, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/dermatophyte-tinea-infections

2. Lederman E, Craft N, Burgin S. Tinea imbricata in adult. VisualDx. Updated September 24, 2018. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52399

3. El-Gohary M, van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, et al. Topical antifungal treatments for tinea cruris and tinea corporis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014:CD009992. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009992.pub2

4. Unwala R. Approach to the patient with annular skin lesions. In: Ofori AO, ed. UpToDate. 2022. Updated September 7, 2022. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.uptodate.com/contents/approach-to-the-patient-with-annular-skin-lesions

5. Wong V, High W, Burgin S. Tinea corporis in adult. VisualDx. Updated March 24, 2019. Accessed November 23, 2022. www.visualdx.com/visualdx/diagnosis/?moduleId=101&diagnosisId=52396#Therapy

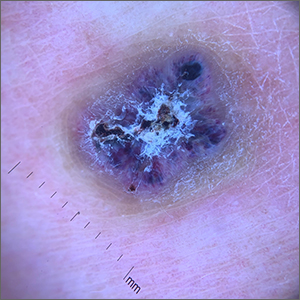

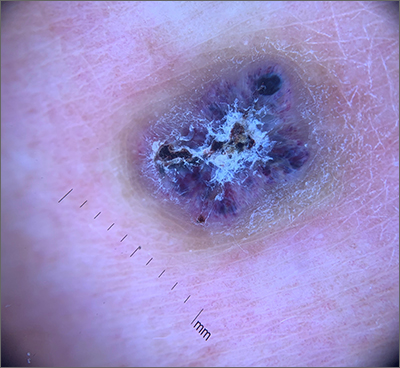

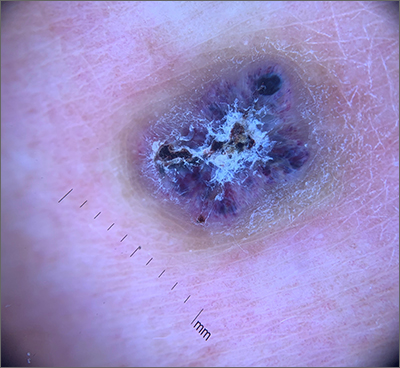

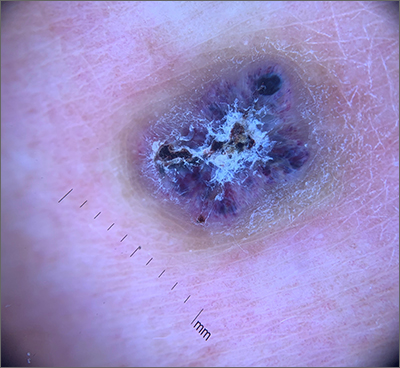

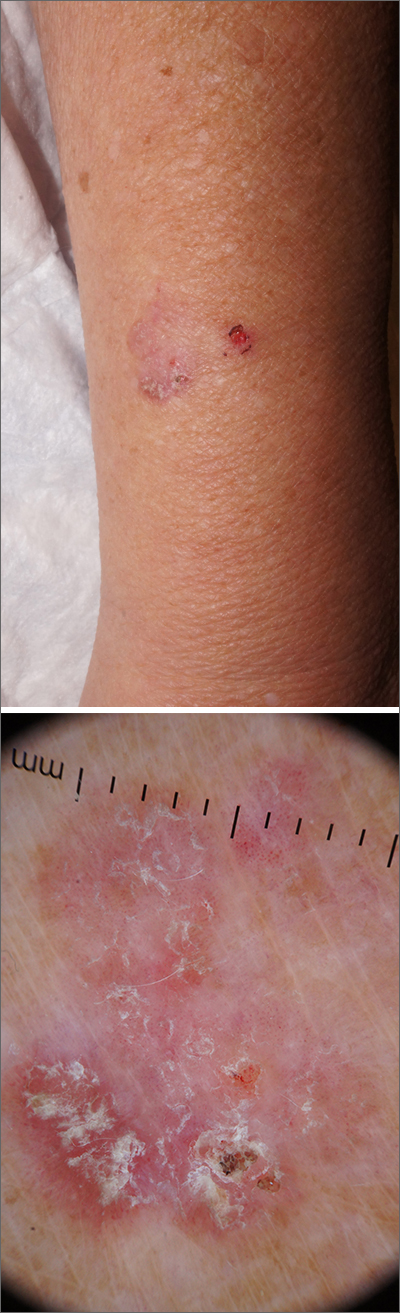

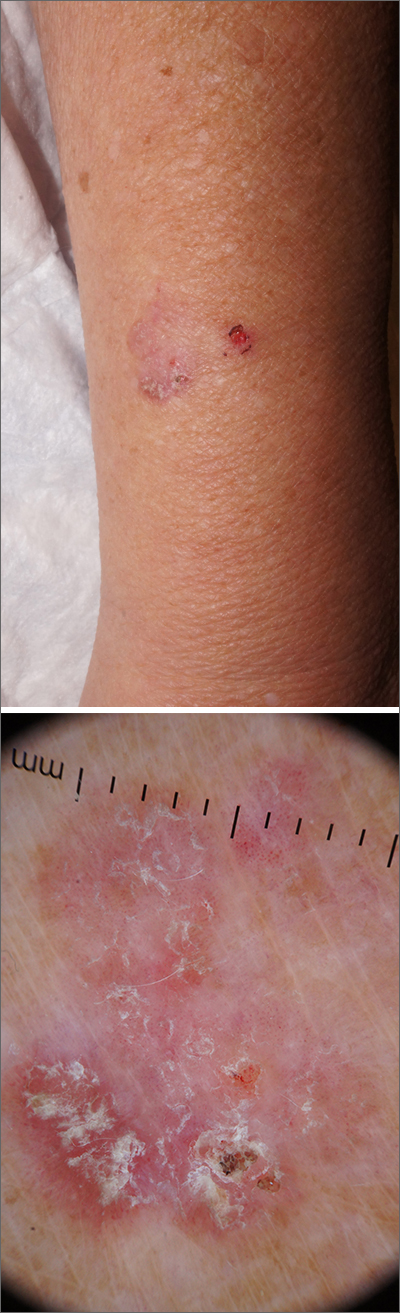

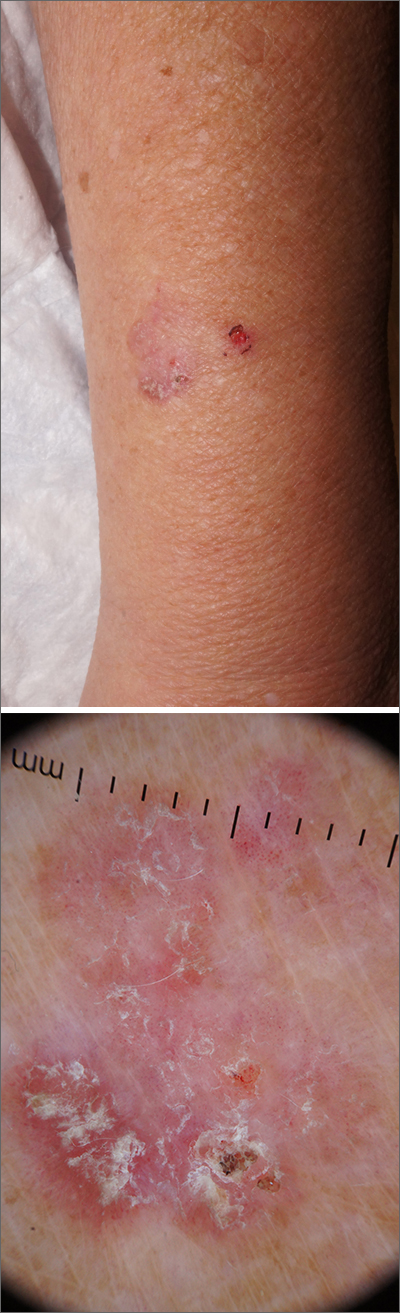

Knee lesion that bleeds

This combination of vascular features with excess keratin fit perfectly with the name of the diagnosis: angiokeratoma. The dark color of the lesion on magnification, or in this case with dermoscopy, showed the lacunar pattern of dilated vessels. The overlying keratin was likely accentuated because it was on an extensor surface; the rim of hyperpigmentation is common for these lesions.

Angiokeratomas result from dilation of the blood vessels underneath the epidermis. There are different inciting events that lead to the 5 different types of angiokeratomas. The overlying epidermal changes are secondary to the underlying process of capillary ectasia.1 This lesion was not part of a cluster, so it was characterized as a solitary angiokeratoma. Smaller lesions are usually less keratinized and are commonly seen on the scrotum and vulva, where there are usually multiple lesions (referred to as angiokeratoma of Fordyce).

Zaballos2 studied the dermoscopic characteristics of 32 solitary angiokeratomas and reported 6 findings in at least half of the solitary lesions. The most common features were dark lacunae in 94% of the lesions, white veil in 91%, and erythema in 69%. Peripheral erythema, red lacunae, and hemorrhagic crusts were all seen at a rate of 53%. The most common location was the lower extremities.

This patient’s previous pathology report from a shave biopsy was found, confirming that the original diagnosis was angiokeratoma. Since the patient’s lesion had not resolved and was symptomatic from minor trauma, he was scheduled to come back in for an elliptical excision to remove the lesion.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282. doi: 10.1159/000246270

2. Zaballos P, Daufí C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318–325. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.3.318

This combination of vascular features with excess keratin fit perfectly with the name of the diagnosis: angiokeratoma. The dark color of the lesion on magnification, or in this case with dermoscopy, showed the lacunar pattern of dilated vessels. The overlying keratin was likely accentuated because it was on an extensor surface; the rim of hyperpigmentation is common for these lesions.

Angiokeratomas result from dilation of the blood vessels underneath the epidermis. There are different inciting events that lead to the 5 different types of angiokeratomas. The overlying epidermal changes are secondary to the underlying process of capillary ectasia.1 This lesion was not part of a cluster, so it was characterized as a solitary angiokeratoma. Smaller lesions are usually less keratinized and are commonly seen on the scrotum and vulva, where there are usually multiple lesions (referred to as angiokeratoma of Fordyce).

Zaballos2 studied the dermoscopic characteristics of 32 solitary angiokeratomas and reported 6 findings in at least half of the solitary lesions. The most common features were dark lacunae in 94% of the lesions, white veil in 91%, and erythema in 69%. Peripheral erythema, red lacunae, and hemorrhagic crusts were all seen at a rate of 53%. The most common location was the lower extremities.

This patient’s previous pathology report from a shave biopsy was found, confirming that the original diagnosis was angiokeratoma. Since the patient’s lesion had not resolved and was symptomatic from minor trauma, he was scheduled to come back in for an elliptical excision to remove the lesion.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

This combination of vascular features with excess keratin fit perfectly with the name of the diagnosis: angiokeratoma. The dark color of the lesion on magnification, or in this case with dermoscopy, showed the lacunar pattern of dilated vessels. The overlying keratin was likely accentuated because it was on an extensor surface; the rim of hyperpigmentation is common for these lesions.

Angiokeratomas result from dilation of the blood vessels underneath the epidermis. There are different inciting events that lead to the 5 different types of angiokeratomas. The overlying epidermal changes are secondary to the underlying process of capillary ectasia.1 This lesion was not part of a cluster, so it was characterized as a solitary angiokeratoma. Smaller lesions are usually less keratinized and are commonly seen on the scrotum and vulva, where there are usually multiple lesions (referred to as angiokeratoma of Fordyce).

Zaballos2 studied the dermoscopic characteristics of 32 solitary angiokeratomas and reported 6 findings in at least half of the solitary lesions. The most common features were dark lacunae in 94% of the lesions, white veil in 91%, and erythema in 69%. Peripheral erythema, red lacunae, and hemorrhagic crusts were all seen at a rate of 53%. The most common location was the lower extremities.

This patient’s previous pathology report from a shave biopsy was found, confirming that the original diagnosis was angiokeratoma. Since the patient’s lesion had not resolved and was symptomatic from minor trauma, he was scheduled to come back in for an elliptical excision to remove the lesion.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282. doi: 10.1159/000246270

2. Zaballos P, Daufí C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318–325. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.3.318

1. Schiller PI, Itin PH. Angiokeratomas: an update. Dermatology. 1996;193:275-282. doi: 10.1159/000246270

2. Zaballos P, Daufí C, Puig S, et al. Dermoscopy of solitary angiokeratomas: a morphological study. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:318–325. doi:10.1001/archderm.143.3.318

Dark spot near ear

Stable slate gray to blue lesions that are asymptomatic raise the possibility of a blue nevus, also known as dermal dendritic melanocytic proliferations. In this case, dermoscopy confirmed a uniform dark color with no signs suggestive of melanoma or pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

Blue nevi are the result of a benign localized proliferation of dermal dendritic melanocytes. The blue color is due to the increased pigment deep in the dermis that reflects the blue shorter wavelength light while absorbing longer wavelengths.1 In this author’s experience, these “blue” lesions usually appear to be more gray (as was the case with this individual). Dermoscopy shows a steel blue homogenous pigmentation.2

It is helpful to use dermoscopy to screen for an atypical pigment network, regression of pigmentation, or abnormal pigmentation; these are signs of atypical nevi and melanoma. It is also important to look for arborizing blood vessels and leaf-like structures that can be seen in pigmented BCCs. Both melanoma and pigmented BCCs can appear as circumscribed dark lesions.

Reassuring factors for blue nevi are lesions that are stable in size and color over time, asymptomatic, and have not bled nor shown signs of erosion. If the diagnosis is in doubt, excise the lesion in its entirety for definitive pathology. Since the melanocytes are typically deeper in blue nevi than in most other nevi, a deep shave technique may not remove the lesion in its entirety. A deeper than usual shave (or, if feasible, a full-thickness excision) may return better results with quicker healing.

This patient was advised of the benign nature of a blue nevus. He was counseled to watch for any changes in the lesion and to return for reevaluation if symptoms or changes occurred.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365-382. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

2. Longo C, Scope A, Lallas A, et al. Blue lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:637-647, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.07.001

Stable slate gray to blue lesions that are asymptomatic raise the possibility of a blue nevus, also known as dermal dendritic melanocytic proliferations. In this case, dermoscopy confirmed a uniform dark color with no signs suggestive of melanoma or pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

Blue nevi are the result of a benign localized proliferation of dermal dendritic melanocytes. The blue color is due to the increased pigment deep in the dermis that reflects the blue shorter wavelength light while absorbing longer wavelengths.1 In this author’s experience, these “blue” lesions usually appear to be more gray (as was the case with this individual). Dermoscopy shows a steel blue homogenous pigmentation.2

It is helpful to use dermoscopy to screen for an atypical pigment network, regression of pigmentation, or abnormal pigmentation; these are signs of atypical nevi and melanoma. It is also important to look for arborizing blood vessels and leaf-like structures that can be seen in pigmented BCCs. Both melanoma and pigmented BCCs can appear as circumscribed dark lesions.

Reassuring factors for blue nevi are lesions that are stable in size and color over time, asymptomatic, and have not bled nor shown signs of erosion. If the diagnosis is in doubt, excise the lesion in its entirety for definitive pathology. Since the melanocytes are typically deeper in blue nevi than in most other nevi, a deep shave technique may not remove the lesion in its entirety. A deeper than usual shave (or, if feasible, a full-thickness excision) may return better results with quicker healing.

This patient was advised of the benign nature of a blue nevus. He was counseled to watch for any changes in the lesion and to return for reevaluation if symptoms or changes occurred.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

Stable slate gray to blue lesions that are asymptomatic raise the possibility of a blue nevus, also known as dermal dendritic melanocytic proliferations. In this case, dermoscopy confirmed a uniform dark color with no signs suggestive of melanoma or pigmented basal cell carcinoma (BCC).

Blue nevi are the result of a benign localized proliferation of dermal dendritic melanocytes. The blue color is due to the increased pigment deep in the dermis that reflects the blue shorter wavelength light while absorbing longer wavelengths.1 In this author’s experience, these “blue” lesions usually appear to be more gray (as was the case with this individual). Dermoscopy shows a steel blue homogenous pigmentation.2

It is helpful to use dermoscopy to screen for an atypical pigment network, regression of pigmentation, or abnormal pigmentation; these are signs of atypical nevi and melanoma. It is also important to look for arborizing blood vessels and leaf-like structures that can be seen in pigmented BCCs. Both melanoma and pigmented BCCs can appear as circumscribed dark lesions.

Reassuring factors for blue nevi are lesions that are stable in size and color over time, asymptomatic, and have not bled nor shown signs of erosion. If the diagnosis is in doubt, excise the lesion in its entirety for definitive pathology. Since the melanocytes are typically deeper in blue nevi than in most other nevi, a deep shave technique may not remove the lesion in its entirety. A deeper than usual shave (or, if feasible, a full-thickness excision) may return better results with quicker healing.

This patient was advised of the benign nature of a blue nevus. He was counseled to watch for any changes in the lesion and to return for reevaluation if symptoms or changes occurred.

Image and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Professor and Chair, Department of Family and Community Medicine, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker, MD School of Medicine, Kalamazoo.

1. Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365-382. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

2. Longo C, Scope A, Lallas A, et al. Blue lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:637-647, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.07.001

1. Murali R, McCarthy SW, Scolyer RA. Blue nevi and related lesions: a review highlighting atypical and newly described variants, distinguishing features and diagnostic pitfalls. Adv Anat Pathol. 2009;16:365-382. doi: 10.1097/PAP.0b013e3181bb6b53

2. Longo C, Scope A, Lallas A, et al. Blue lesions. Dermatol Clin. 2013;31:637-647, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2013.07.001

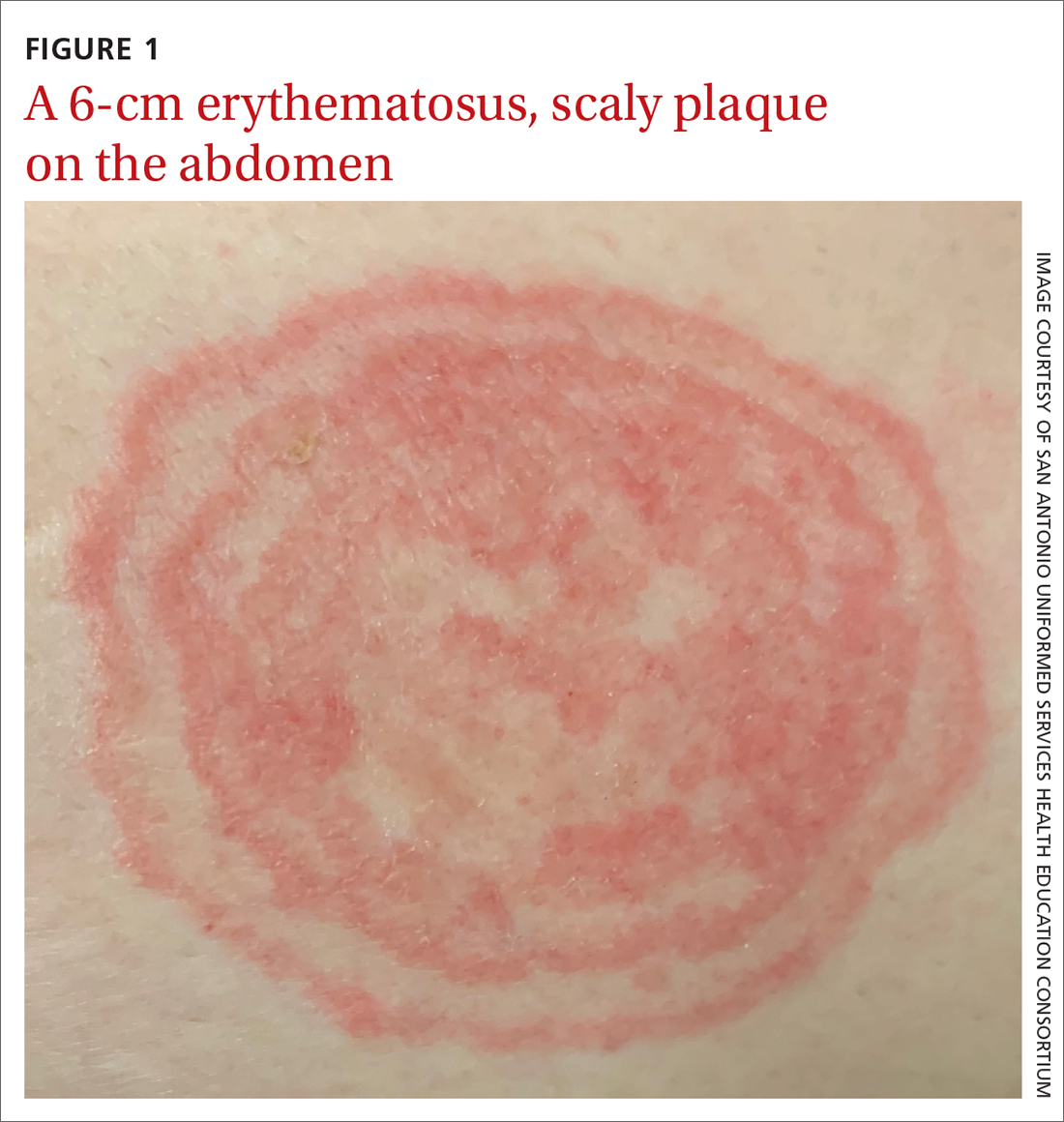

Severe pediatric oral mucositis

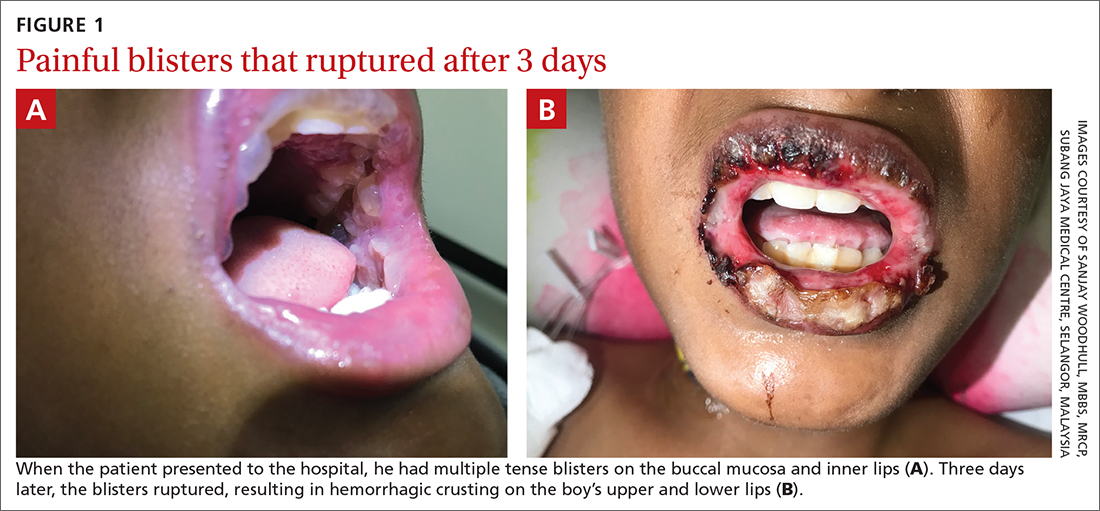

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

A 12-YEAR-OLD BOY presented to the hospital with a 2-day history of fever, cough, and painful blisters on swollen lips. On examination, he had multiple tense blisters with clear fluid on the buccal mucosa and inner lips (FIGURE 1A), as well as multiple discrete ulcers on his posterior pharynx. The patient had no other skin, eye, or urogenital involvement, but he was dehydrated. Respiratory examination was unremarkable. A complete blood count and metabolic panel were normal, as was a C-reactive protein (CRP) test (0.8 mg/L).

The preliminary diagnosis was primary herpetic gingivostomatitis, and treatment was initiated with intravenous (IV) acyclovir (10 mg/kg every 8 hours), IV fluids, and topical lidocaine gel and topical steroids for analgesia. However, the patient’s fever persisted over the next 4 days, with his temperature fluctuating between 101.3 °F and 104 °F, and he had a worsening productive cough. The blisters ruptured on Day 6 of illness, leaving hemorrhagic crusting on his lips (FIGURE 1B). Herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing were negative.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Dx: Mycoplasma pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis

Further follow-up on Day 6 of illness revealed bibasilar crepitations along with an elevated CRP level of 40.5 mg/L and a positive mycoplasma antibody serology (titer > 1:1280; normal, < 1:80). The patient was given a diagnosis of pneumonia (due to infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae) and M pneumoniae–induced rash and mucositis (MIRM).

MIRM was first proposed as a distinct clinical entity in 2015 to distinguish it from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme.1 MIRM is seen more commonly in children and young adults, with a male preponderance.1

A small longitudinal study found that approximately 22.7% of children who have M pneumoniae infections present with mucocutaneous lesions, and of those cases, 6.8% are MIRM.2Chlamydia pneumoniae is another potential causal organism of mucositis resembling MIRM.3

Pathogenesis. The commonly accepted mechanism of MIRM is an immune response triggered by a distant infection. This leads to tissue damage via polyclonal B cell proliferation and subsequent immune complex deposition, complement activation, and cytokine overproduction. Molecular mimicry between M pneumoniae P1-adhesion molecules and keratinocyte antigens may also contribute to this pathway.

3 criteria to make the diagnosis

Canavan et al1 have proposed the following criteria for the diagnosis of MIRM:

- Clinical symptoms, such as fever and cough, and laboratory findings of M pneumoniae infection (elevated M pneumoniae immunoglobulin M antibodies, positive cultures or PCR for M pneumoniae from oropharyngeal samples or bullae, and/or serial cold agglutinins) AND

- a rash to the mucosa that usually affects ≥ 2 sites (although rare cases may have fewer than 2 mucosal sites involved) AND

- skin detachment of less than 10% of the body surface area.

Continue to: The 3 variants of MIRM include...

The 3 variants of MIRM include:

- Classic MIRM has evidence of all 3 diagnostic criteria plus a nonmucosal rash, such as vesiculobullous lesions (77%), scattered target lesions (48%), papules (14%), macules (12%), and morbilliform eruptions (9%).4

- MIRM sine rash includes all 3 criteria but there is no significant cutaneous, nonmucosal rash. There may be “few fleeting morbilliform lesions or a few vesicles.”4

- Severe MIRM includes the first 2 criteria listed, but the cutaneous rash is extensive, with widespread nonmucosal blisters or flat atypical target lesions.4

Our patient had definitive clinical symptoms, laboratory evidence, and severe oral mucositis without significant cutaneous rash, thereby fulfilling the criteria for a diagnosis of MIRM sine rash variant.

These skin conditions were considered in the differential

The differential diagnosis for sudden onset of severe oral mucosal blisters in children includes herpes gingivostomatitis; hand, foot, and mouth disease

Herpes gingivostomatitis would involve numerous ulcerations of the oral mucosa and tongue, as well as gum hypertrophy.

Hand, foot, and mouth disease is characterized by

Continue to: Erythema multiforme

Erythema multiforme appears as cutaneous target lesions on the limbs that spread in a centripetal manner following herpes simplex virus infection.

SJS/TEN manifests with severe mucositis and is commonly triggered by medications (eg, sulphonamides, beta-lactams, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and antiepileptics).

With antibiotics, the prognosis is good

There are no established guidelines for the treatment of MIRM. Antibiotics and supportive care are universally accepted. Immunosuppressive therapy (eg, systemic steroids) is frequently used in patients with MIRM who have extensive mucosal involvement, in an attempt to decrease inflammation and pain; however, evidence for such an approach is lacking. The hyperimmune reactions of the host to M pneumoniae infection include cytokine overproduction and T-cell activation, which promote both pulmonary and extrapulmonary manifestations. This forms the basis of immunosuppressive therapy, such as systemic corticosteroids, IV immunoglobulin, and cyclosporin A, particularly when MIRM is associated with pneumonia caused by infection with M pneumoniae.1,5,6

The overall prognosis of MIRM is good. Recurrence has been reported in up to 8% of cases, the treatment of which remains the same. Mucocutaneous and ocular sequelae (oral or genital synechiae, corneal ulcerations, dry eyes, loss of eye lashes) have been reported in less than 9% of patients.1 Other rare reported complications following the occurrence of MIRM include persistent cutaneous lesions, B cell lymphopenia, and restrictive lung disease or chronic obliterative bronchitis.

Our patient was started on IV ceftriaxone (50 mg/kg/d), azithromycin (10 mg/kg/d on the first day, then 5 mg/kg/d on the subsequent 5 days), and methylprednisolone (3 mg/kg/d) on Day 6 of illness. Within 3 days, there was marked improvement of mucositis and respiratory symptoms with resolution of fever. He was discharged on Day 10. At his outpatient follow-up 2 weeks later, the patient had made a complete recovery.

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

1. Canavan TN, Mathes EF, Frieden I, et al. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015;72:239-245. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.06.026

2. Sauteur PMM, Theiler M, Buettcher M, et al. Frequency and clinical presentation of mucocutaneous disease due to mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in children with community-acquired pneumonia. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156:144-150. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3602

3. Mayor-Ibarguren A, Feito-Rodriguez M, González-Ramos J, et al. Mucositis secondary to chlamydia pneumoniae infection: expanding the mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis concept. Pediatr Dermatol 2017;34:465-472. doi: 10.1111/pde.13140

4. Frantz GF, McAninch SA. Mycoplasma mucositis. StatPearls [Internet]. Updated August 8, 2022. Accessed November 1, 2022. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525960/

5. Yang EA, Kang HM, Rhim JW, et al. Early corticosteroid therapy for Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia irrespective of used antibiotics in children. J Clin Med. 2019;8:726. doi: 10.3390/jcm8050726

6. Li HOY, Colantonio S, Ramien ML. Treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis with cyclosporine. J Cutan Med Surg. 2019;23:608-612. doi: 10.1177/1203475419874444

Clear toe lesion

This is a digital mucous cyst, also known as a myxoid cyst. The clear to translucent appearance over a finger or toe joint is usually diagnosed clinically. If uncertain, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Digital mucous cysts are a type of ganglion cyst that is associated with trauma or arthritis in the toe joint. A microscopic opening in the joint capsule results in a fluid filled cyst in the surrounding tissue. If the cyst is ruptured, thick, gelatinous (sometimes blood-tinged) hyaluronic acid–rich fluid may escape. Sometimes, the cyst applies pressure to the nail matrix, causing a scooped out longitudinal nail deformity.

Digital mucous cysts more commonly affect the fingers than the toes. Although benign, patients may be bothered by the appearance of these cysts and their effect on nails. Observation is a reasonable approach. Rarely, digital mucous cysts resolve spontaneously.

Treatment options include cryotherapy, needle draining and scarification, and surgical excision with flap repair. Surgical excision may be performed quickly in the office and offers the highest cure rate of 95% in 1 study on fingers.1 Cryotherapy is successful in 70% of cases and needle drainage is successful in 39% of cases, but these modalities are quick and require minimal downtime.1

In this case, the patient was not significantly bothered by the lesion and was happy to forego treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.

1. Jabbour S, Kechichian E, Haber R, et al. Management of digital mucous cysts: a systematic review and treatment algorithm. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:701-708. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13583

This is a digital mucous cyst, also known as a myxoid cyst. The clear to translucent appearance over a finger or toe joint is usually diagnosed clinically. If uncertain, a biopsy can confirm the diagnosis.

Digital mucous cysts are a type of ganglion cyst that is associated with trauma or arthritis in the toe joint. A microscopic opening in the joint capsule results in a fluid filled cyst in the surrounding tissue. If the cyst is ruptured, thick, gelatinous (sometimes blood-tinged) hyaluronic acid–rich fluid may escape. Sometimes, the cyst applies pressure to the nail matrix, causing a scooped out longitudinal nail deformity.

Digital mucous cysts more commonly affect the fingers than the toes. Although benign, patients may be bothered by the appearance of these cysts and their effect on nails. Observation is a reasonable approach. Rarely, digital mucous cysts resolve spontaneously.

Treatment options include cryotherapy, needle draining and scarification, and surgical excision with flap repair. Surgical excision may be performed quickly in the office and offers the highest cure rate of 95% in 1 study on fingers.1 Cryotherapy is successful in 70% of cases and needle drainage is successful in 39% of cases, but these modalities are quick and require minimal downtime.1

In this case, the patient was not significantly bothered by the lesion and was happy to forego treatment.

Photos and text for Photo Rounds Friday courtesy of Jonathan Karnes, MD (copyright retained). Dr. Karnes is the medical director of MDFMR Dermatology Services, Augusta, ME.